How Is Climate Change Impacting the Educational Choices and Career Plans of Undergraduates?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

3. Results

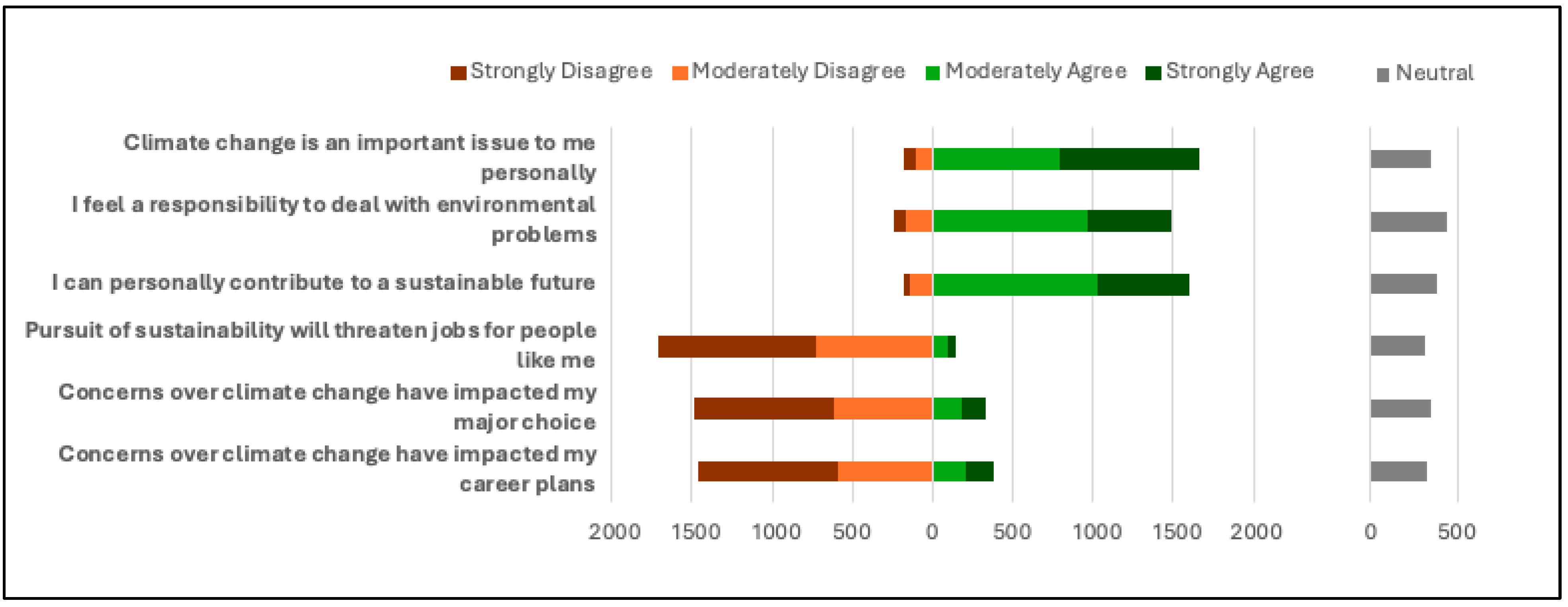

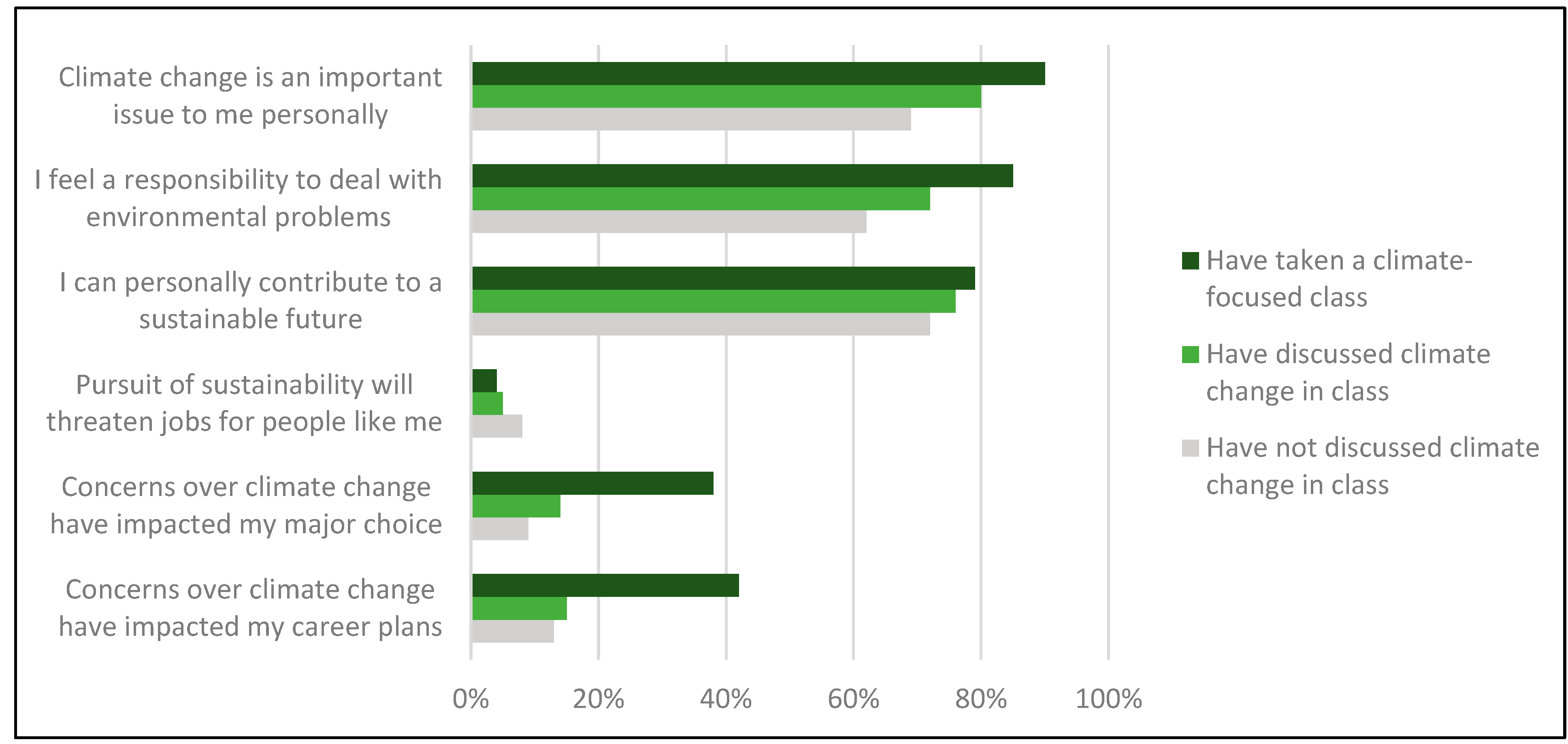

3.1. Respondents’ Beliefs About Climate Change

3.2. Impact of Climate Change on Major Choice

“I believe that chemistry can help solve many problems whether it be pollution, energy production, or cleaning up the environment”.

“I realized that a career and a major in German would not have the impact on the world that I wanted it to have”.

“I chose the policy track because I figured there was no sense in pursuing STEM if I couldn’t communicate my science to people in a meaningful way”.

“I was highly interested in biology, but found passion in the intersection of science and policy and applying science to real issues!”

“I originally considered working towards a career in dentistry, but after taking some introductory biology courses I realized that I was much more passionate about environmental issues rather than the hard science. I also did not want to work in a lab for my career and enjoy office culture, which is why I also decided to major in economics to give myself more career options which would hopefully intersect in the environmental sphere”.

“My interest in high school focused on computer science, but the industry is very profit-focused in general. Data centers and technology contributes to climate change and environmental issues. Majoring in Biology opens up the possibility of research beyond college and a more sustainable tech focus career wise”.

“Better job security and income”.

“I wanted to double major to expand employment opportunities”.

3.3. Impact of Climate Change on Career Plans

“Climate change has encouraged me to pursue being a teacher because I feel like education is important to helping us combat climate change and schools are a good place to implement sustainable practices”.

“Climate change has influenced my career plans in medicine by highlighting the urgent need for healthcare professionals who can address the health impacts of a changing environment”.

“After originally wanting to study fashion business management, I quickly pivoted to the opposite side. I‘m hoping to fight the environmental degradation the fashion industry causes”.

“As a geology major, I don’t want to work for oil/petroleum companies because of climate change, along with the bloody history of oil”.

“I actively am choosing to not apply for jobs at companies that are sustainably irresponsible or use greenwashing”.

“Climate change has really just impacted where I may want to work or live, because if those places become uninhabitable, they are no longer options and the people who are currently there will be forced to adapt or leave”.

“I do not want to live in states where mitigating climate change is not a priority for the governing body”.

“Climate change has made me want to go to graduate school to pursue a PhD in materials science in order to better develop renewable energy technologies”.

“Environmental concerns over cities and transportation have led me to pursue a career in urban and environmental planning, which I am going to graduate school for next year”.

“I no longer want to ‘waste time’ in graduate school. I want to make a difference as soon as possible with my skills. I also want to work in conservation now to help the planet”.

“I now want a job that provides higher pay so I have a monetary buffer in case anything goes horribly wrong”.

“I want to enjoy the earth as it is while I still can and capture it for posterity”.

“Current climate catastrophes have caused me to question the certainty about the previously solid life plan for my future”.

“Climate change has impacted everyone’s career plans, whether they realize it or not”.

4. Discussion

Limitations of This Study

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- United Nations Global Issues. Climate Change. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/global-issues/climate-change (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Atwood, M. Oryx and Crake: A Novel; Nan A. Talese: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Emmerich, R. The Day After Tomorrow [Film]; Twentieth Century Fox: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Business Week. Global Warming. Business Week, 18 December 2006.

- Gore, A. An Inconvenient Truth: The Planetary Emergency of Global Warming and What We Can Do About It; Rodale Pres: New York, NY, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Guggenheim, D. An Inconvenient Truth [Film]; Lawrence Bender Productions: Beverly Hills, CA, USA; Participant Productions: Beverly Hills, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- McKie, R. This is the Moment When the World Seems to Get the Message at Last. Observer Magazine, 24 December 2006. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2006/dec/24/globalwarming.climatechange#:~:text=issued%20with%20challenge-,This%20article%20is%20more%20than%2018%20years%20old (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Saldanha, C. Ice Age: The Meltdown [Film]; Twentieth Century Fox Home Entertainment LLC: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, J. The Magic School Bus and the Climate Challenge; Scholastic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hickman, C.; Marks, E.; Pihkala, P.; Clayton, S.; Lewandowski, R.E.; Mayall, E.E.; Wray, B.; Mellor, C.; van Susteren, L. Climate Anxiety in Children and Young People and Their Beliefs About Government Responses to Climate Change: A Global Survey. Lancet Planet. Health 2021, 5, e863–e873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowski, R.E.; Clayton, S.D.; Olbrich, L.; Sakshaug, J.W.; Wray, B.; Schwartz, S.E.; Augustinavicius, J.; Howe, P.D.; Parnes, M.; Wright, S.; et al. Climate Emotions, Thoughts, and Plans among US Adolescents and Young Adults: A Cross-sectional Descriptive Survey and Analysis by Political Party Identification and Self-reported Exposure to Severe Weather Events. Lancet Planet. Health 2024, 8, e879–e893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teo, S.M.; Gao, C.X.; Brennan, N.; Fava, N.; Simmons, M.B.; Baker, D.; Zbukvic, I.; Rickwood, D.J.; Brown, E.; Smith, C.L.; et al. Climate Change Concerns Impact on Young Australians’ Psychological Distress and Outlook for the Future. J. Environ. Psychol. 2024, 93, 102209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cort, T.; Gilbert, K.; DeCew, S.; Goldberg, M.; Wilkinson, E.; Fitzgerald, H. Rising Leaders on Social and Environmental Sustainability; Yale Program on Climate Change Communication: New Haven, CT, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher, E.A.; Billings, S.B.; Ricketts, L.R. Human Capital Investment after the Storm. Rev. Financ. Stud. 2023, 36, 2651–2684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cornaggia, J.; Cornaggia, K.; Xia, H. Natural Disasters, Financial Shocks, and Human Capital. Manag. Sci. 2025, accepted. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezarik, M. Actions and Hopes of the Sustainability-Focused Student. Inside Higher Ed, 2 January 2023. Available online: https://www.insidehighered.com/news/students/academics/2023/01/02/sustainability-actions-students-take-and-want-their-colleges (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Anderson, D.M.; Broton, K.M.; Monaghan, D.B. Seeking STEM: The Causal Impact of Need-Based Grant Aid on Undergraduates’ Field of Study. J. High. Educ. 2023, 94, 921–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denning, J.T.; Turley, P. Was that SMART? Institutional Financial Incentives and Field of Study. J. Hum. Resour. 2017, 52, 152–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stange, K. Differential Pricing in Undergraduate Education: Effects on Degree Production by Field. J. Policy Anal. Manag. 2015, 34, 107–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcidiacono, P.; Hotz, V.J.; Maurel, A.; Romano, T. Ex Ante Returns and Occupational Choice. J. Political Econ. 2020, 128, 4475–4522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiswall, M.; Zafar, B. Determinants of College Major Choice: Identification using an Information Experiment. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2015, 82, 791–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcidiacono, P.; Hotz, V.J.; Kang, S. Modeling college major choices using elicited measures of expectations and counterfactuals. J. Econom. 2012, 166, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xia, X. Grades as Signals of Comparative Advantage: How Letter Grades Affect Major Choices. J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2024, 227, 106717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaganovich, M.; Taylor, M.; Xiao, R. Gender Differences in Persistence in a Field of Study: This Isn’t All about Grades. J. Hum. Cap. 2023, 17, 503–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemici, A.; Wiswall, M. Evolution Of Gender Differences In Post-Secondary Human Capital Investments: College Majors. Int. Econ. Rev. 2014, 55, 23–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Winters, J.V. Industry Fluctuations and College Major Choices: Evidence from an Energy Boom and Bust. Econ. Educ. Rev. 2020, 77, 101996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Sun, W.; Winters, J. Up In Stem, Down In Business: Changing College Major Decisions With The Great Recession. Contemp. Econ. Policy 2019, 37, 476–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodkinson, P.; Sparkes, A.C. Careership: A Sociological Theory of Career Decision Making. Br. J. Sociol. Educ. 1997, 18, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Law, B. Career-learning Space: New-dots Thinking for Careers Education. Br. J. Guid. Couns. 1999, 27, 35–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lent, R.W. A Social Cognitive View of Career Development and Counseling in Career Development and Counseling: Putting Theory and Research to Work; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pryor, R.; Bright, J. The Chaos Theory of Careers. J. Employ. Couns. 2011, 48, 163–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kniveton, B.H. The Influences and Motivations on Which Students Base their Choice of Career. Res. Educ. 2004, 72, 7–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auyeung, P.; Sands, J. Factors Influencing Accounting Students’ Career Choice: A Cross-Cultural Validation Study. Account. Educ. Int. J. 1997, 6, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, S. Choosing Money Over Meaningful Work: Examining Relative Job Preferences for High Compensation Versus Meaningful Work. Personal. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2024, 50, 1128–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, I. Influences on Career Choice: Considerations for the Environmental Profession. Environ. Pract. 2017, 19, 115–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shealy, T.; Katz, A.; Godwin, A. Predicting Engineering Students’ Desire to Address Climate Change in their Careers: An Exploratory Study Using Responses from a US National Survey. Environ. Educ. Res. 2021, 27, 1054–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kistner, M.; Jiménez, J. Concerned but Confused: University Students’ Knowledge and Perceptions of Climate Change, and How They Plan to Address it in their Future Personal and Professional Lives. SUNY J. Scholarsh. Engagem. 2023, 3, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Cordero, E.C.; Centeno, D.; Todd, A.M. The Role of Climate Change Education on Individual Lifetime Carbon Emissions. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0206266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, R.C.; Sorensen, A.E.; Gray, S.A. What Undergraduate Students Know and What They Want to Learn About in Climate Change Education. PLoS Sustain. Transform. 2023, 2, e0000055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malgwi, C.A.; Howe, M.A.; Burnaby, P.A. Influences on Students’ Choice of College Major. J. Educ. Bus. 2005, 80, 275–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Climate Opinion Maps. Yale Program on Climate Change Communication. 2024. Available online: https://climatecommunication.yale.edu/visualizations-data/ycom-us-2024/ (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Howe, P.D.; Mildenberger, M.; Marlon, J.R.; Leiserowitz, A. Geographic Variation in Opinions on Climate Change at State and Local Scales in the USA. Nat. Clim. Change 2015, 5, 596–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CBS News Poll Finds Big Majority of Americans Support US Taking Steps to Reduce Climate Change. Available online: https://www.cbsnews.com/news/poll-reduce-climate-change-extreme-weather-04-21-2024/ (accessed on 26 June 2025).

- Griesinger, T.; Reid, K.; Knight, D.; Katz, A.; Somers, J. Inspiring Sustainability in Undergraduate Engineering Programs. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayton, S.; Parnes, M.F. Anxiety and Activism in Response to Climate Change. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2025, 62, 101996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwartz, S.E.; Benoit, L.; Clayton, S.; Parnes, M.F.; Swenson, L.; Lowe, S.R. Climate Change Anxiety and Mental Health: Environmental Activism as Buffer. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 42, 16708–16721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Respondents | W&M Undergraduate Students a | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Female | 70% b | 59% |

| Male | 30% b | 41% |

| Race | ||

| White | 58% | 62% |

| Black | 3% | 5% |

| Hispanic | 7% | 9% |

| Asian | 12% | 12% |

| Multiracial | 8% | 7% |

| Other | <1% | 4% |

| Not Answered/Unknown | 11% | 1% |

| Year in School | ||

| 4th Year | 24% c | 26% |

| 3rd Year | 25% c | 25% |

| 2nd Year | 25% c | 25% |

| 1st Year | 25% c | 25% |

| Financial Aid Status d | 52% | 65% e |

| Virginia Residents | 61% f | 63% |

| 4th-Year Respondents a | Degrees Conferred 2021–2024 b | |

|---|---|---|

| Government | 6% | 8% |

| Psychology | 10% | 8% |

| Biology | 7% | 8% |

| Kinesiology & Health Sciences | 5% | 6% |

| Economics | 7% | 6% |

| History | 6% | 6% |

| Computer Science | 5% | 5% |

| Finance | 3% | 5% |

| International Relations | 6% | 4% |

| Neuroscience | 4% | 4% |

| English | 4% | 3% |

| Mathematics | 1% | 3% |

| Public Policy | 3% | 3% |

| Chemistry | 5% | 2% |

| Business Analytics | 3% | 2% |

| Have Taken Climate-Focused Class | Have Discussed Climate Change in Class * | Have Not Discussed Climate Change in Class | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4th Year | 113 | 236 | 112 |

| 3rd Year | 104 | 226 | 124 |

| 2nd Year | 78 | 205 | 142 |

| 1st Year | 47 | 171 | 171 |

| Total | 342 | 838 | 549 |

| Climate Change Has Impacted Major Choice | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agree | Neutral | Disagree | ||

| Climate Change Has Impacted Career Plans | Agree | 12% | 3% | 2% |

| Neutral | 2% | 11% | 2% | |

| Disagree | 1% | 3% | 64% | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stafford, S.L. How Is Climate Change Impacting the Educational Choices and Career Plans of Undergraduates? Sustainability 2025, 17, 6324. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146324

Stafford SL. How Is Climate Change Impacting the Educational Choices and Career Plans of Undergraduates? Sustainability. 2025; 17(14):6324. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146324

Chicago/Turabian StyleStafford, Sarah Lynne. 2025. "How Is Climate Change Impacting the Educational Choices and Career Plans of Undergraduates?" Sustainability 17, no. 14: 6324. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146324

APA StyleStafford, S. L. (2025). How Is Climate Change Impacting the Educational Choices and Career Plans of Undergraduates? Sustainability, 17(14), 6324. https://doi.org/10.3390/su17146324