Abstract

Pig farming plays a crucial socioeconomic role in the European Union, which is one of the largest pork exporters in the world. In Portugal, pig farming plays a key role in regional development and the national economy. To ensure future sustainability and minimize environmental impacts, it is essential to identify the most deleterious pig production activities. This study carried out a life cycle assessment (LCA) of pig production using a conventional system in central Portugal to identify the unitary processes with the greatest environmental impact problems. LCA followed the ISO 14040/14044 standards, covering the entire production cycle, from feed manufacturing to waste management, using 1 kg of live pig weight as the functional unit. The slurry produced is used as fertilizer in agriculture, replacing synthetic chemical fertilizers. Results show that feed production, raising piglets, and fattening pigs are the most impactful phases of the pig production cycle. Fodder production is the stage with the greatest impact, accounting for approximately 60% to 70% of the impact in the categories analyzed in most cases. The environmental categories with the highest impacts were freshwater ecotoxicity, human carcinogenic toxicity, and marine ecotoxicity; the most significant impacts were observed for human health, with an estimated effect of around 0.00045 habitants equivalent (Hab.eq) after normalization. The use of more sustainable ingredients and the optimization of feed efficiency are effective strategies for promoting sustainability in the pig farming sector.

1. Introduction

Life cycle assessment (LCA) is an essential tool to evaluate the environmental impact of a product throughout its useful life, from raw material extraction to disposal and recycling [1]. The process encompasses multiple steps, such as manufacturing, transportation, installation, use, maintenance, and end-of-life disposal, to provide a comprehensive analysis of a product’s sustainability performance. It offers a comprehensive view of the most critical phases in terms of resource consumption and pollutant generation, allowing governments, companies, and even consumers to make informed decisions. By identifying areas for improvement, LCA directly contributes to the creation of more sustainable products, which is crucial in the transition to a low-carbon economy and promotion of more environmentally responsible practices [2]. In addition to the environmental aspects, it is possible to incorporate social and cost indicators for a comprehensive assessment [1].

The application of LCA to pig farming is particularly relevant since this sector plays a crucial role in the global economy and generates significant environmental impacts throughout all production stages. Pig farming has a big socioeconomic relevance in the European Union (EU), which is one of the largest exporters of pork meat in the world. Pork production has gradually increased in the EU in recent years, reaching a maximum of 22 million tonnes in 2022 [3].

LCA has increasingly been applied to evaluate the environmental impacts of pig farming, aiming to identify opportunities for improvement in sustainability. Several recent studies have focused on assessing the different stages of the pig production system, from feed production to waste management [4,5]. The mini-review by Ferreira et al. [6] on the application of LCA in pig farming highlights the advances and methodologies adopted in this field. It emphasizes the importance of identifying which stages of pig production have the most significant environmental impacts, providing valuable insights into areas where improvements can be made for greater sustainability.

Pig farming is considered one of the most important agricultural activities in the world. In 2022, global pork production reached approximately 108.8 million tons, with China, the United States, and the European Union being the largest producers [7,8]. This growth is attributed to factors such as increasing population, increasing incomes, and improving production efficiency.

In Portugal, pig farming is a vital activity due to the wealth and jobs it generates, being an important component of the country’s culture and food tradition. It represents more than 41% of the country’s animal production and more than 50% of all agricultural production [9]. The central region of Portugal is characterized by geographic and climatic diversity that impacts agricultural practices and livestock farming. The Mediterranean climate, characterized by hot and dry summers, can negatively affect livestock production [9], but its mountainous soils and fertile areas help in cereal production and livestock farming, including pig farming [10]. The proximity of rural areas to urban centers facilitates access to markets, but also poses challenges related to waste management and the efficient use of resources [11]. This sector is an important driver of regional development, and plays an important role in the Portuguese trade balance and in the population’s food supply [3].

However, pig production chains face challenges related to sustainable management, animal welfare, and technological advances [12]. The entire livestock production system can generate environmental burdens, such as greenhouse gas emissions and soil and water pollution, asking for more sustainable practices. Environmental impacts are present from feed production to waste disposal, substantially impacting water, air, soil quality, biodiversity, and the global climate [13].

Waste management is the more promising issue in terms of mitigating pig farming environmental impacts. Inadequate waste management can increase nitrate and phosphorus leaching, causing soil and water pollution, whilst increasing the danger of adding heavy metals to the environment [14]. Sustainable livestock waste management strategies can significantly reduce the environmental burden linked to animal rearing, namely global warming, freshwater eutrophication, and terrestrial acidification [15]. The integration of swine production in agroecological systems can promote biodiversity and improve resource efficiency, in addition to optimizing the use of fertilizers and minimizing the flow of nutrients into water bodies [16].

The current literature demonstrates that feed production and waste management are the stages with the most significant environmental impact. The production of feed ingredients, such as corn and soy flour, has substantial impacts on global warming, acidification, and eutrophication, leading to high environmental burdens. In contrast, the sustainable management of pig waste can enhance the overall environmental performance of the production system [17,18,19].

This study applies the LCA methodology to pig production in the central region of Portugal. Factors such as climate, soil conditions, and local agricultural practices play a significant role in the magnitude of environmental impacts and the identification of hotspots. The main objective is to identify and quantify the environmental impacts linked with each stage of a conventional pig production system in this region, highlighting its local particularities and offering insights to improve the sector’s sustainability.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Case Study

This study examines the production model of a single company devoted to rearing pigs for slaughter, in the central region of Portugal. Production is divided into two main phases: (i) Breeding and insemination of sows. At this stage, the sows go from the gestational period until the piglets’ birth. Piglets remain in this unit until they reach approximately 20 kg. (ii) The next process is carried out in another unit, to which the piglets are transferred to complete the fattening stage until they reach around 100 kg, the appropriate weight for slaughter. During this fattening phase, the pigs’ waste falls into a box located beneath the area where they move around. At the end of three months, these boxes are emptied and cleaned, and the slurry is directed to a homogenization tank. With this system, the area occupied by the pigs remains consistently clean and dry. The waste then undergoes a mechanical separation, dividing it into solid and liquid components using a mechanical press. Both separated fractions are then reused in agricultural activities (e.g., as fertilizers), in collaboration with local farmers. This unit is powered by a diesel generator to meet its energy needs, as it is not connected to the electricity grid. Furthermore, the water supply is guaranteed through a local well.

Only data from the second stage were made available by the pig farm owner and used in this study. The management of waste generated by pigs is carried out during this second phase. A characterization of the raw slurry was carried out experimentally, and the data obtained in this analysis are presented in Table 1. The analytical methods used to perform the slurry characterization are described in the Supplementary Materials, along with the standard deviations, which are presented in Table S1.

Table 1.

Characterization of raw slurry from pig farming (mean values).

2.2. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA)

The environmental impact assessment was carried out using the LCA framework in accordance with ISO 14040:2006 [20] and ISO 14044:2006 [21] guidelines.

Life cycle assessment (LCA) entails several critical components that are required for assessing the environmental consequences of a product throughout its entire life cycle. These components comprise selecting a functional unit, defining study objectives, developing an inventory, evaluating environmental impacts, and interpreting results for informed decision-making [22].

2.2.1. Aim and Scope of This Study

The main objective of this LCA was to evaluate the environmental impacts of pig production for slaughter in a pig farm based in central Portugal. Other objectives were to identify the main critical points throughout the life cycle, evaluate the significance of the pig waste management stage in the final result, and propose improvements to reduce the environmental impacts.

The functional unit (FU) was assumed to be 1 kg live weight of a fattened pig for slaughter outside the pig farm gate.

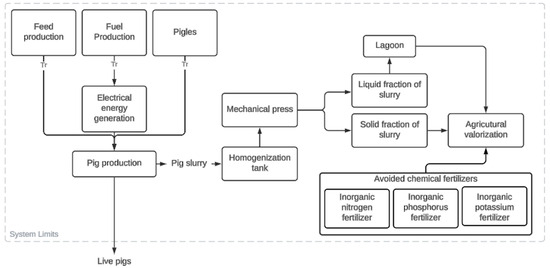

The limits of the study system covered all processes related to pig farming including the use of pig manure (i.e., from cradle-to-gate), as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

System limit for production of pigs for slaughter.

The analyzed scenario begins with the production of fodder and fuel used to generate electrical energy, following the entry of piglets into the breeding system. After the pigs grow and fatten, for about three months, the slurry generated is directed to a homogenization tank and subsequently processed in a mechanical press that separates the solid and liquid fractions. The liquid fraction is stored in a lagoon. Both fractions are reused in agricultural activities, contributing to reducing the use of chemical fertilizers.

System boundaries encompass all stages of the pig production life cycle, including:

- Fodder Production: The compound feed formulation is a generic swine formulation (weighted aggregate of piglet, sow, and fattening pig formulations), based on Kebreab et al. [23], which is representative of Portugal. It starts with the cultivation and processing of ingredients, involving sowing the seeds, applying fertilizers and pesticides, harvesting, transporting, cleaning, drying, grinding, and mixing the ingredients.

- Fuel Production: Including the production of the fuel (diesel) used at the farm to generate electricity. It begins with the extraction of crude oil and its transportation to refineries. In refineries, oil is processed to produce diesel and other derivatives. The refined diesel is subsequently transported to distribution points such as warehouses and gas stations. The final phase involves storing diesel oil in tanks on the pig farm and combusting it in diesel–electric generators sets to produce electricity for essential power run equipment, and illumination.

- Piglets: As the data for this stage were unavailable from the pig farm owner in this study, this dataset represents an adaptation for Portugal of a typical (average) pig breeding production in Spain available in SimaPro 9.6.01 software. Animal farm inputs include fodder, energy, water, straw, and transport of fodder to the farm. Specific manure management systems are considered. Emissions included are CH4 from enteric fermentation and from manure, N2O (direct and indirect), NH3, NOx, PM, and NMVOC emissions from manure.

- Pig production: This includes activities at the farm from the arrival of piglets until the pigs reach their slaughter weight. This includes daily feeding adjusted to promote adequate growth, sanitary management of the animals, and the use of energy and water to maintain farm conditions. The pigs were raised in pens and fed a balanced diet to efficiently reach their ideal commercial weight. Specific manure management systems are considered.

- Waste Management: This includes the management of the waste produced by pigs during breeding. Washing of stalls and other breeding areas was performed using water, which was subsequently directed to the homogenization tank, where the slurry (a mixture of feces, urine, and water) was stirred to ensure a uniform mixture. Subsequently, solid–liquid separation occurs using a mechanical press that consumes energy and separates the slurry into two fractions: solid and liquid. The liquid fraction was then stored in an open tank (lagoon). Both solid and liquid fractions are used in agriculture. The application of these fractions to the soil partially replaces industrial chemical fertilizers (NPK), promoting more sustainable agricultural practices.

2.2.2. Life Cycle Inventory (LCI)

According to ISO 14040:2006 [20], LCI is a stage of LCA that comprises the collection and detailed quantification of all inputs and outputs associated with the production system under investigation. The inputs and outputs of the system under study are presented in Table 2. Primary data on the consumption of fuel, fodder, water, piglet input, and the quantity of pig and manure produced were obtained directly from the administration of the production unit. Data on emissions to the air and water were calculated in accordance with the IPCC [24] and EMEP/EEA [25] protocols. Secondary data for the inputs of fodder, water, diesel, piglets, and transportation, as well as for chemical fertilizers avoided, were obtained from the background processes (Table 2) available in the SimaPro software.

Table 2.

Data table for a functional unit (kg/year live pigs at the exit from the pig farm).

With the aid of the SimaPro 9.6.01 software, the LCI data were calculated, and used as a basis for environmental impact assessments.

Three main types of avoided inorganic fertilizers were considered: nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P2O5), and potassium (K2O), all of which originate from mineral sources and are macronutrients essential for plant development. These fertilizers are synthesized from fossil resources such as natural gas, coal, phosphate rock, and potassium minerals, and are expressed in terms of their equivalent nutrient forms. The production chain for each fertilizer begins with the finished product ready for transport at the manufacturing unit and finishes with the distribution to consumers in Portugal.

Allocation

The allocation of environmental impacts between coproducts is in accordance with the background processes available in the SimaPro software (Table 2). In the process “Piglet, at farm {PT} Economic, U,” the allocation between spent sows and piglets is based on the economic values of the coproducts. The prices considered for spent sow and piglets are 888 euros/ton and 1767 euros/ton, respectively.

2.2.3. Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA)

Life cycle impact assessment (LCIA) is a crucial component of LCA that seeks to comprehend and quantify the significance of potential environmental effects linked to identified inputs and outputs. The LCIA process involves categorizing inventory data into impact groups and quantitatively characterizing them to estimate each category’s potential. This evaluation is the basis for comparing the environmental consequences of assessed processes and products, providing information for more sustainable and well-informed decision-making. The SimaPro software was used to transform inventory data into an environmental profile.

The ReCiPe 2016 method was chosen to evaluate environmental impact, allowing for the generation of environmental indicators at intermediate and ultimate levels. The intermediate level encompassed 18 impact categories: global warming (GW), stratospheric ozone depletion (SOD), ionizing radiation (IR), ozone formation (affecting human health (OF-HH) and terrestrial ecosystems (OF-TE)), fine particulate matter formation (FPMF), terrestrial acidification (TA) and ecotoxicity (Tec), freshwater eutrophication (FE) and ecotoxicity (FEc), marine eutrophication (ME) and ecotoxicity (Mec), human carcinogenic toxicity (HCT) and non-carcinogenic toxicity (HNCT), land use (LU), mineral (MRS) and fossil resource scarcity (FRS), and water consumption (WC). The last level includes 3 damage categories: human health, ecosystems, and resources. ReCiPe’s strength lies in its provision of detailed midpoint indicators and their integration into broader endpoint categories, offering a comprehensive perspective on potential impacts. It is currently the most frequently employed LCIA method in LCA research [29,30].

To determine the relative importance of each product system indicator, a normalized environmental profile was developed. In accordance with ISO 14044:2006 [21] guidelines, normalization involves dividing an indicator’s result by a selected reference value. The ReCiPe method uses aggregate inputs and outputs per world inhabitant for 2010 as reference values, serving as a benchmark. The normalization unit, Hab.eq (habitants equivalent), is used to express impacts in terms of the equivalent contribution of an average inhabitant to a specific environmental issue in a year.

3. Results

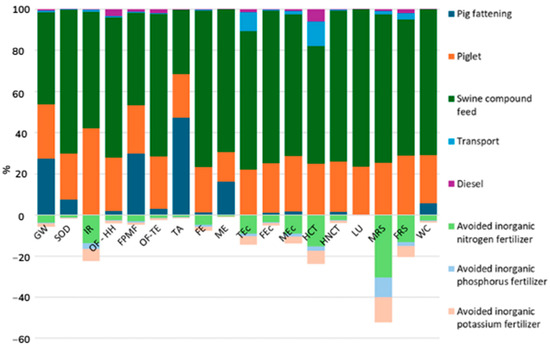

Figure 2 and Table S2 display the environmental profile of the FU, which is 1 kg of live weight of fattened pigs ready for slaughter at the farm gate. The LCA of pig production reveals that the most significant environmental impacts occur during compound pig feed production, piglet rearing, and animal fattening phases.

Figure 2.

Environmental profile of FU using the method ReCiPe 2016 Midpoint (H) V1.09/World (2010) H/A/Characterisation. Acronyms: GW: Global warming; SOD: Stratospheric ozone depletion; IR: Ionizing radiation; OF-HH: Ozone formation, Human health; FPMF: Fine particulate matter formation; OF-TE: Ozone formation, Terrestrial ecosystems; TA: Terrestrial acidification; FE: Freshwater eutrophication; ME: Marine eutrophication; TEc: Terrestrial ecotoxicity; FEc: Freshwater ecotoxicity; MEc: Marine ecotoxicity; HCT: Human carcinogenic toxicity; HNCT: Human non-carcinogenic toxicity; LU: Land use; MRS: Mineral resource scarcity; FRS: Fossil resource scarcity; WC: Water consumption.

The characterization graphs show that fodder production is the main contributor to environmental impacts, accounting for roughly 60% to 70% in most categories analyzed. However, for TA, GW, and FPMF, fodder’s impact is less than 50%. In those categories, pig fattening is more prominent, contributing 47.40%, 27.32%, and 29.84%, respectively.

Piglet rearing also shows substantial impact across all categories, typically representing about 25% of the total impact. Notably, for the IR category, this phase has the highest contribution at 42.03%.

The use of diesel in electric generators and transportation had comparatively minor impacts. Nevertheless, transport is more significant in the HCT and TEc categories, contributing 11.83% and 9.21%, respectively. Diesel use was most impactful in the HCT category, with a 5.99% contribution.

Conversely, measures preventing the use of nitrogen-, phosphorus-, and potassium-based inorganic fertilizers show a positive effect on mitigating environmental impacts. These steps help reduce impacts, particularly in the categories MRS, HCT, IR, and FRS, with reductions of −52.33%, −23.75%, −22.39%, and −20.48%, respectively. The negative values imply that these measures have a beneficial effect in decreasing environmental impacts.

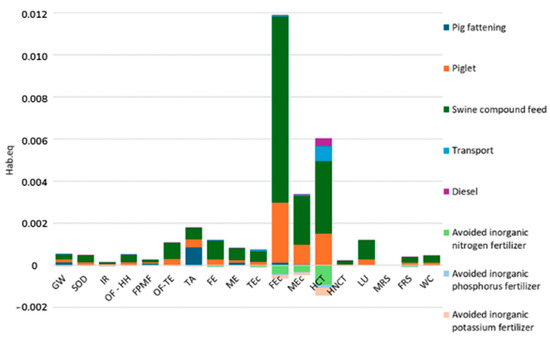

The normalized environmental profile of the FU is illustrated in Figure 3 and Table S3. The most significant environmental impact categories were FEc (0.012 Hab.eq), HCT (0.006 Hab.eq), and MEc (0.0035 Hab.eq). The processes that contribute the most to these effects are the production of compound fodder for pigs and the raising of piglets. The steps to avoid inorganic fertilizers are also relevant in these three categories, exhibiting negative values, which indicates a beneficial contribution to reduce environmental impacts.

Figure 3.

Normalized environmental profile of FU using the method ReCiPe 2016 Midpoint (H) V1.09/World (2010) H/A. Acronyms: GW: Global warming; SOD: Stratospheric ozone depletion; IR: Ionizing radiation; OF-HH: Ozone formation, Human health; FPMF: Fine particulate matter formation; OF-TE: Ozone formation, Terrestrial ecosystems; TA: Terrestrial acidification; FE: Freshwater eutrophication; ME: Marine eutrophication; TEc: Terrestrial ecotoxicity; FEc: Freshwater ecotoxicity; MEc: Marine ecotoxicity; HCT: Human carcinogenic toxicity; HNCT: Human non-carcinogenic toxicity; LU: Land use; MRS: Mineral resource scarcity; FRS: Fossil resource scarcity; WC: Water consumption.

Swine compound fodder consumption is the main contributor to FEc, accounting for 78.4%. Within this, dried barley grain contributes 27.4%, dried wheat grain 17.1%, and soybean meal 12.1%. Piglet production is responsible for 25.4% of FEc, with gestation and weaning housing systems contributing 14% and piglet rearing housing systems 6.6%. Avoiding inorganic nitrogen, potassium, and phosphorus fertilizers reduces FEc by 3.7%, 1.3%, and 0.5%, respectively. Herbicides and insecticides contribute 48.6% and 15.8% to this impact category, primarily through soil emissions of metolachlor (44.7%) and chlorpyrifos (15.5%), and water emissions of copper (13.3%).

While agricultural practices largely influence FEc, HCT shares similar contributing factors but with different health implications. HCT is mainly attributed to swine compound fodder consumption (75.1%), with dried barley grain contributing 27.4%, dried wheat grain 17.1%, and soybean meal 12.1%. Piglet production accounts for 32.4% of HCT, including 14% from gestation and weaning housing systems and 6.6% from piglet rearing housing systems. Avoiding inorganic nitrogen, potassium, and phosphorus fertilizers reduces HCT by 20%, 8.29%, and 2.89%, respectively. Farm tractors, concrete slabs in facility construction, and electricity usage contribute 27.2%, 22.6%, and 18% to this impact category, primarily through chromium emissions to water (90%).

Transitioning from land to water environments, MEc shows both commonalities and distinctions in its primary contributors compared to human carcinogenic toxicity. MEc is largely associated with swine compound feed consumption (80.1%), with dried barley grain contributing 27.6%, dried wheat grain 16.2%, and electricity 8.21%. Piglet production accounts for 31.3% of MEc, including 14.6% from gestation and weaning housing systems and 7% from electricity. Avoiding inorganic nitrogen, potassium, and phosphorus fertilizers reduces HCT by 10.6%, 3.94%, and 1.5%, respectively. Sulfuric acid use, electricity, and insecticides contribute 20.7%, 15.4%, and 14.8% to this impact category, mainly through copper (35.6%) and zinc (19%) emissions into water.

Across all three toxicity categories, swine compound fodder emerges as the primary contributor, emphasizing its significant environmental impact. Piglet production consistently accounts for a substantial portion of each toxicity category, highlighting the importance of sustainable practices in this phase of swine farming. The avoidance of inorganic fertilizers helps reduce all three toxicity categories to various degrees. While soil and water emissions primarily impact freshwater ecotoxicity, water emissions, particularly of heavy metals, have a greater influence on human carcinogenic toxicity and marine ecotoxicity.

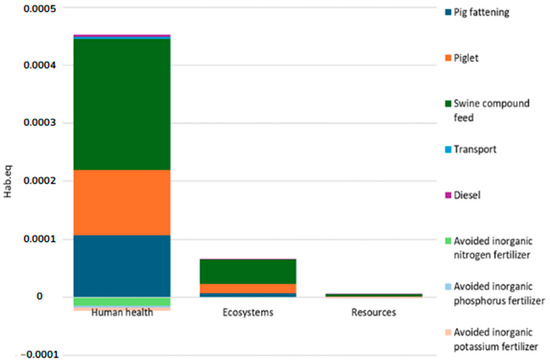

Analysis of endpoint-level normalization (Figure 4 and Table S4) revealed that human health was the most significantly damage category in pig production, with an estimated effect of about 0.00045 Hab.eq. This damage primarily stemmed from the substantial contributions of pig compound fodder production, piglet rearing, and pig fattening stages. Processes linked with mitigating the use of inorganic fertilizers showed considerable positive effects in this damage category. The ecosystem damage followed, with an impact below 0.0001 Hab.eq. The resource damage demonstrated minimal significant influence on the overall results.

Figure 4.

Normalized environmental profile of FU using the method ReCiPe 2016 Endpoint (H) V1.09/World (2010) H/A.

4. Discussion

This study identified the stage of producing compound fodder for pigs as the main critical point in the pig production chain. This step proved to be more significant in terms of its contribution to environmental impacts, in line with findings from previous research. In addition, McAuliffe et al. [31], Dourmad et al. [32], and González-García et al. [33] identified fodder production as the main factor responsible for the environmental impacts in pig production systems. The cultivation of grains used in fodder, such as corn and soy, is a relevant factor contributing to deforestation, resulting in the loss of biodiversity and maintenance of ecosystems. This process also involves intensive water consumption and is responsible for significant greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Gislason et al. [34] and Reckmann et al. [35] demonstrated that environmental impacts attributed to fodder production can range from 31% to 50% of the total impacts of the pig production system. Similarly, a recent LCA study on pork production in Thailand highlighted fodder production, particularly corn cultivation, as a critical factor with the greatest impact across several environmental categories [36].

The most relevant impact categories were FEc, MEc, and HCT. Although these results show areas of environmental concern, it is important to consider that toxicity impacts often present high uncertainty in LCA studies. Therefore, the comparison of toxicity results between different studies must be performed with caution, as the methodologies and characterization factors can vary significantly. However, a relevant factor for these impacts may be the use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides in fodder production, which can contaminate soil and water courses and pose potential risks to the environment [37]. Research by Buch et al. [38] demonstrated that agrochemicals used in agricultural systems can harm beneficial microorganisms in the soil, putting the sustainability of food systems in danger.

Normalized results indicate that human health is the damage category most impacted, followed by ecosystems, in line with the results of Notarnicola et al. [39]. This finding reinforces the hypothesis that the use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides in fodder production contributes significantly to these impacts. This process of contamination and bioaccumulation in the food chain represents a relevant threat to human health and ecosystems, especially in the toxicity and ecotoxicity categories, where the impacts increase.

The piglet production stage also significantly contributes to increase environmental impacts. According to Reckmann and Krieter [40], piglet production has a significant share of the GWP associated with pig production, estimated at 3.22 kg CO2-eq per kg of pork, which is in line with the 4 kg CO2-eq obtained in this study. This impact is due to the fact that piglet production includes the entire maintenance of the production system, from caring for breeding sows to managing animal waste during the piglet rearing period, until they reach the ideal weight to be taken to the rearing fattening phase. The environmental impacts at this stage include intensive consumption of resources, such as water and fodder, and generation of waste, such as leachate, which emits GHGs. Raising breeding sows also requires the maintenance of energy-intensive facilities as well as the need for substantial water and fodder resources. The high resources’ demand can result in negative environmental impacts if sustainable management is absent [41]. Management practices can also contribute to soil tilling and the contamination of water resources due to fertilizers and antibiotics use.

The waste produced at the fattening stage also stands out for its high environmental impacts, largely due to waste management, particularly pig manure. According to Brito et al. [41], pig farming is linked with high levels of methane and nitrous oxide emissions that arise mainly from manure management. In relation to manure management, allocating all pig manure for agricultural valorization through the use of biological fertilizers contributes positively to the mitigation of environmental impacts. The use of this biofertilizer reduces the use of inorganic fertilizers based on nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium. Basset-Mens and Van der Werf [42] state that organic pig production systems have lower eutrophication and acidification potentials than conventional systems, partly due to the reduction in synthetic fertilizers’ use.

Antezana et al. [43] performed a detailed physicochemical analysis of swine manure, revealing that it can be used as a replacement for synthetic fertilizers, as long as it is adequately characterized. This measure is required due to specific variations in its composition, which may require nutrient supplementation or the application of specific treatment techniques, depending on crop requirements. Partial replacement of chemical fertilizers with biofertilizers can significantly reduce pig production’s environmental impacts [44]. Additionally, biofertilizers improve the soil structure and increase microbial activity, facilitating efficient nutrient cycling and improving soil health. This process also contributes to atmospheric nitrogen fixation and reduces the dependence on synthetic fertilizers [45,46].

However, it is important to consider that the results of LCA studies in agriculture can vary significantly, depending on regional characteristics. Factors such as climate, soil conditions, and local agricultural practices influence the observed environmental impacts, and studies in different regions tend to reveal differences in the magnitude of the impacts and critical points.

The study highlights the importance of understanding the environmental impacts and the impact categories most affected in the study region, which, in this case, is the Central Portugal. Eutrophication and acidification are relevant categories, as these conditions directly affect the local environment, with increased pollution of water bodies and deterioration in soil quality. Eutrophication, for example, can be intensified by inadequate waste management in pig farming, while acidification can occur due to emissions of ammonia and nitrogen oxides from animal production [47].

Furthermore, the “water consumption” category is especially significant for Central Portugal, as this region faces a water deficit during the summer due to the scarcity of water resources [48].

Adopting sustainable strategies is crucial to mitigate the environmental impact of pig production. One of the most effective strategies may be to focus on the production of pig fodder, as this stage is responsible for the highest environmental impacts. In this context, the implementation of precision feeding is presented as an advanced nutritional management practice, the objective of which is to provide the exact amount of nutrients required by each animal in a personalized and efficient manner. This technique can reduce the excretion of nitrogen and phosphorus, thereby reducing environmental contamination [49]. Another recommended measure is the replacement of soy-based products with alternative legumes or synthetic amino acids that can mitigate environmental impacts [35].

5. Conclusions

The implementation of LCA on a pig farm in Portugal highlights the main challenges to be overcome by the local industry.

The results show that fodder production, piglet farming, and pig fattening have the greatest environmental impact on pig production. The production of fodder compounds for pigs stood out as the main source of impact in almost all the addressed categories, except for terrestrial acidification, where manure management during the animal fattening phase had greater relevance.

In the normalized environmental profile, human health was the damage category most affected by pig production, and the most significant impact categories were freshwater ecotoxicity, human carcinogenic toxicity, and marine ecotoxicity. These impacts are mainly linked with fodder production and piglet farming, with substantial contributions from agricultural practices such as the use of herbicides and insecticides.

This study guides society, potentially influencing public policies, promoting responsible agricultural practices, and informing consumers and producers about the importance of sustainable methods in reducing emissions and promoting long-term sustainability.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su17020426/s1, File S1: Analytical methods used for slurry characterization [50]; File S2: Tables for Characterization, Normalization (Midpoint and Endpoint) of Environmental Profile.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.F. and L.S.; methodology, J.F. and L.S.; software, M.F.; validation, J.F.; formal analysis, J.F., I.D. and L.S.; investigation, J.F. and L.S.; resources, J.F., A.F., V.O., C.R. and I.D.; data curation, J.F.; writing—original draft preparation, J.F. and L.S.; writing—review and editing, J.F., L.S., M.F., A.F., V.O., C.R. and I.D.; supervision, J.F.; project administration and English revision, A.F.; funding acquisition, J.F., A.F., V.O., C.R. and I.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was conducted in the framework of Project PRR-C05-i03-I-000030-LA3.3 and LA3.4 financed by PRR and financed by national funds through FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, through the CERNAS Research Centre—project UIDB/00681/2020 (I.D.).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the support of the Escola Superior de Gestão e Tecnologia de Viseu, Instituto Politécnico de Viseu and Escola Superior Agrária, Instituto Politécnico de Coimbra, which provided the essential resources for this research. Thanks are also extended to collaborators and colleagues for their valuable insights and contributions, which significantly improved this study. Verónica Oliveira expresses thanks for the national funding by FCT, through the institutional scientific employment program-contract (doi: 10.54499/CEECINST/00077/2021/CP2798/CT0002).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hernandez, P.; Oregi, X.; Longo, S.; Cellura, M. Life-cycle assessment of buildings. In Handbook of Energy Efficiency in Buildings; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 207–261. [Google Scholar]

- Pacana, A.; Siwiec, D. Improving Products Considering Customer Expectations and Life Cycle Assessment (LCA). Syst. Saf. Hum. Tech. Facil. Environ. 2023, 5, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GPP. GPP Políticas e Administração Geral. In Setor Suinícola Nacional—Diagnóstico do Setor e Propostas de Medidas de Promoção da Sustentabilidade da Atividades Suinícola; GPP: Lisbon, Portugal, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Launay, F. 4 Hands-on 2: Environmental evaluation of feeding strategies with agent-based modeling and life cycle assessment: From theory to practice. Sponsored by EAAP. J. Anim. Sci. 2024, 102, 69–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, J.; Liu, H.; Song, X.; Yu, B.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Wu, N. Life Cycle Assessment of Three Manure Treatment Modes in Large-scale Pig Farm. Acad. J. Sci. Technol. 2023, 8, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, J.; Santos, L.; Ferreira, M.; Ferreira, A. and Domingos, I. Environmental Assessment of Pig Manure Treatment Systems through Life Cycle Assessment: A Mini-Review. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Wu, X.; Han, D.; Hou, Y.; Tan, J.; Kim, S.W.; Wang, J. Pork production systems in China: A review of their development, challenges and prospects in green production. Front. Agric. Sci. Eng. 2021, 8, 15–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.W.; Gormley, A.; Jang, K.B.; Duarte, M.E. Current status of global pig production: An overview and research trends. Anim. Biosci. 2023, 37, 719. [Google Scholar]

- Cruz, V.F.; Lucas, E.M.; Baptista, F.J. Characterisation of pig production in Portugal-alternative outdoor housing systems. In Proceedings of the First International Conference, Des Moines, IA, USA, 9–11 October 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz-Rojas, J.; Pinto-Correia, T.; Thorsoe, M.H.; Noe, E. The portuguese montado: A complex system under tension between different land use management paradigms. Silvic.-Manag. Conserv. 2019, 4, 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Monteiro, M.C.H.; Sánchez Durán, S.; Coutinho, J.P.; Gil Perez, B.; Almeida, C.A.M.; Sánchez Sánchez, J.; García-González, M.C. Characterization of the Agricultural and Livestock Holdings in the Spanish Region of Castilla y Léon and in the Portuguese Central Region. 2022. Available online: https://repositorio.ipcb.pt/handle/10400.11/7945 (accessed on 25 September 2024).

- Maselyne, J. Advancement in Livestock Farming through Emerging New Technologies. In Women in Precision Agriculture; Hamrita, T.K., Ed.; Women in Engineering and Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 181–196. ISBN 978-3-030-49243-4. [Google Scholar]

- Leip, A.; Billen, G.; Garnier, J.; Grizzetti, B.; Lassaletta, L.; Reis, S.; Simpson, D.; Sutton, M.A.; De Vries, W.; Weiss, F. Impacts of European livestock production: Nitrogen, sulphur, phosphorus and greenhouse gas emissions, land-use, water eutrophication and biodiversity. Environ. Res. Lett. 2015, 10, 115004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capa-Camacho, X.; Martínez-Pagán, P.; Martínez-Segura, M.; Faz Cano, Á. Environmental Risk Assessment of a Slurry Pond Using 3D Time-Lapse with EarthImager 3D and Voxler Software. In Proceedings of the NSG2023 29th European Meeting of Environmental and Engineering Geophysics, Edinburgh, UK, 3–7 September 2023; European Association of Geoscientists & Engineers: Edinburgh, UK, 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Venslauskas, K.; Navickas, K.; Rubežius, M.; Tilvikienė, V.; Supronienė, S.; Doyeni, M.O.; Barčauskaitė, K.; Bakšinskaitė, A.; Bunevičienė, K. Environmental impact assessment of sustainable pig farm via management of nutrient and co-product flows in the farm. Agronomy 2022, 12, 760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa-Galaviz, E.; Smart, S.M.; Ward, S.E.; Fraser, M.D.; Memmott, J. Fertilization using manure minimizes the trade-offs between biodiversity and forage production in agri-environment scheme grasslands. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0290843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lamnatou, C.; Ezcurra-Ciaurriz, X.; Chemisana, D.; Plà-Aragonés, L.M. Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) of a food-production system in Spain: Iberian ham based on an extensive system. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 808, 151900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alba-Reyes, Y.; Barrera, E.L.; Brito-Ibarra, Y.; Hermida-García, F.O. Life cycle environmental impacts of using food waste liquid fodder as an alternative for pig feeding in a conventional Cuban farm. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 858, 159915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giraldi-Díaz, M.R.; Castillo-González, E.; De Medina-Salas, L.; Velasquez-De la Cruz, R.; Huerta-Silva, H.D. Environmental impacts associated with intensive production in pig farms in Mexico through life cycle assessment. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 14040; Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Principles and Framework. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- ISO 14044; Environmental Management—Life Cycle Assessment—Requirements and Guidelines. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2006.

- Curran, M.; de Souza, D.M.; Antón, A.; Teixeira, R.F.M.; Michelsen, O.; Vidal-Legaz, B.; Sala, S.; Canals, L.M. i How Well Does LCA Model Land Use Impacts on Biodiversity?—A Comparison with Approaches from Ecology and Conservation | Environmental Science & Technology. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2016, 50, 2782–2795. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kebreab, E.; Liedke, A.; Caro, D.; Deimling, S.; Binder, M.; Finkbeiner, M. Environmental impact of using specialty feed ingredients in swine and poultry production: A life cycle assessment. J. Anim. Sci. 2016, 94, 2664–2681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IPCC. 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories; Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (IGES): Hayama, Japan, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- EMEP/EEA. EMEP/EEA Air Pollutant Emission Inventory Guidebook Technical Guidance to Prepare National Emission Inventories; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Smaling, E.M.A. An Agro-Ecological Framework for Integrated Nutrient Management, with Special Reference to Kenya; Wageningen University and Research: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Roy, R.N.; Misra, R.V.; Lesschen, J.P.; Smaling, E.M.A. Assessment of Soil Nutrient Balance: Approaches and Methodologies; Food & Agriculture Org.: Rome, Italy, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Brock, E.H.; Ketterings, Q.M.; Kleinman, P.J. Phosphorus leaching through intact soil cores as influenced by type and duration of manure application. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 2007, 77, 269–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbitsky, O.; Pushkar, S. ECO-INDICATOR 99, ReCiPe and ANOVA FOR EVALUATING BUILDING TECHNOLOGIES UNDER LCA UNCERTAINTIES. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. (EEMJ) 2018, 17, 2549–2559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashedi, A.; Khanam, T. Life cycle assessment of most widely adopted solar photovoltaic energy technologies by mid-point and end-point indicators of ReCiPe method. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 29075–29090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McAuliffe, G.A.; Chapman, D.V.; Sage, C.L. A thematic review of life cycle assessment (LCA) applied to pig production. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2016, 56, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dourmad, J.-Y.; Ryschawy, J.; Trousson, T.; Bonneau, M.; Gonzàlez, J.; Houwers, H.W.J.; Hviid, M.; Zimmer, C.; Nguyen, T.L.T.; Morgensen, L. Evaluating environmental impacts of contrasting pig farming systems with life cycle assessment. Animal 2014, 8, 2027–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-García, S.; Belo, S.; Dias, A.C.; Rodrigues, J.V.; Da Costa, R.R.; Ferreira, A.; De Andrade, L.P.; Arroja, L. Life cycle assessment of pigmeat production: Portuguese case study and proposal of improvement options. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 100, 126–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gislason, S.; Birkved, M.; Maresca, A. A systematic literature review of life cycle assessments on primary pig production: Impacts, comparisons, and mitigation areas. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2023, 42, 44–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reckmann, K.; Blank, R.; Traulsen, I.; Krieter, J. Comparative life cycle assessment (LCA) of pork using different protein sources in pig feed. Arch. Anim. Breed. 2016, 59, 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joyroy, M.; Sriphirom, P.; Buawech, D.; Phrommarat, B. Life Cycle Assessment of Slaughtered Pork Production: A Case Study in Thailand: 10.32526/ennrj/22/20240074. Environ. Nat. Resour. J. 2024, 22, 310–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, M.; Singh, N.K.; Singh, N.K.; Jagwani, T.; Yadav, S. Pesticides and fertilisers contamination of groundwater: Health effects, treatment approaches, and legal aspects. In Contaminants of Emerging Concerns and Reigning Removal Technologies; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022; pp. 349–376. [Google Scholar]

- Buch, K.; Saikanth, D.R.K.; Singh, B.V.; Mallick, B.; Pandey, S.K.; Prabhavathi, N.; Satapathy, S.N. Impact of agrochemicals on beneficial microorganisms and human health. Int. J. Environ. Clim. Chang. 2023, 13, 1135–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notarnicola, B.; Sala, S.; Anton, A.; McLaren, S.J.; Saouter, E.; Sonesson, U. The role of life cycle assessment in supporting sustainable agri-food systems: A review of the challenges. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 140, 399–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reckmann, K.; Krieter, J. Environmental impacts of the pork supply chain with regard to farm performance. J. Agric. Sci. 2015, 153, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, S.A.P.D.; Duarte, G.D.; Sobral, F.E.d.S.; Christoffersen, M.L. Environmental Impacts of Swine Farming. Environ. Smoke 2022, 5, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basset-Mens, C.; Van der Werf, H.M. Scenario-based environmental assessment of farming systems: The case of pig production in France. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2005, 105, 127–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antezana, W.; De Blas, C.; García-Rebollar, P.; Rodríguez, C.; Beccaccia, A.; Ferrer, P.; Cerisuelo, A.; Moset, V.; Estellés, F.; Cambra-López, M.; et al. Composition, potential emissions and agricultural value of pig slurry from Spanish commercial farms. Nutr. Cycl. Agroecosyst. 2016, 104, 159–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahandage, P.D.; Rupasinghe, C.P.; Ariyawansha, K.T.; Piyathissa, S.D.S. Assessing environmental impacts of chemical fertilizers and organic fertilizers in Sri Lankan paddy fields through life cycle analysis. J. Dry Zone Agric. 2023, 9, 45–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jana, B.; Chattopadhyay, R.; Das, R.; Kanthal, S. Bio-fertilizer: An alternative to chemical fertilizer in agriculture. Int. J. Res. Agron. 2024, 7, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varma, N.; Wadatkar, H.; Salve, R.; Kumar, T.V. Advancing Sustainable Agriculture: A Comprehensive Review of Organic Farming Practices and Environmental Impact. J. Exp. Agric. Int. 2024, 46, 695–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamiazzo, J. Evaluation of Phytodepuration Intensified Systems for the Treatment of Agricultural and Livestock Wastewaters. 2015. Available online: https://www.research.unipd.it/handle/11577/3424624 (accessed on 30 October 2024).

- Soares, P.M.; Lima, D.C. Water scarcity down to earth surface in a Mediterranean climate: The extreme future of soil moisture in Portugal. J. Hydrol. 2022, 615, 128731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llorens, B.; Pomar, C.; Goyette, B.; Rajagopal, R.; Andretta, I.; Latorre, M.A.; Remus, A. Precision feeding as a tool to reduce the environmental footprint of pig production systems: A life-cycle assessment. J. Anim. Sci. 2024, 102, skae225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bremmer, J.M. Total nitrogen. In Methods of Soils Analyses; Black, C.A., Evans, D.D., White, J.L., Ensminger, L.E., Clarck, F.E., Eds.; Amercian Society of Agronomy: Madison, WI, USA, 1979; pp. 1149–1178. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).