Abstract

For sustainable educational integration, universities are tasked with the aim of educating specialists who are chosen based on particular criteria in order to promote sustainable development. In the domain of social work, it is crucial to take into account young individuals who express a desire to pursue studies in this field and who have prosocial orientations and tendencies. This research was based on the application of a Prosocial Orientation Questionnaire on a group of 238 students (M—2.4 years, 89.5% female) using questions with a purpose, but also a scale for measuring prosocial tendencies (PTM). The findings regarding the prosocial guidelines highlighted the role of the family in the multidimensional development of prosocial behaviour (PSB), but also the involvement in voluntary activities. The results revealed a high association with the six scales of PTM, with higher values being obtained for three dimensions (Compliant, Dire, Emotional) that show a stronger development. Assessing prosocial orientations and tendencies can help select a career and pursue university courses in the social field. The use of these instruments provides evidence of the effectiveness of PTM in assessing prosocial tendencies and supports the idea that PSB is multidimensional. This is demonstrated by the correlations observed in young individuals pursuing a social career.

1. Introduction

The European Union has sustainable development at the forefront of its concerns, which is in line with the Sustainable Development Goals stipulated by the United Nations [1]. In the 17 objectives proposed by the United Nations for the 2030 Agenda, a series of principles for sustainable economic, environmental, and social development are provided, and each state must implement its own universal and sustainable systems at national level, which reflect the parties’ commitment to sustainable development [2]. The significance of social protection systems in alleviating extreme poverty and providing access to social work programmes for marginalised groups, particularly children, young people, and the elderly, is statistically demonstrated in ‘Goal 1—No poverty’ and ‘Goal 2—Zero hunger’. Therefore, it is imperative for each state to establish durable social protection systems in order to guarantee the inclusion of marginalised populations in support programmes. The training of professionals to support the establishment of a social protection system based on expertise and professional knowledge aligns with these sustainable development objectives. Also, in Goal 4—Quality education, for sustainable educational integration, we must consider young individuals interested in studying in the social field. This should be based on their prosocial orientations and adherence to social values, which are fundamental for their future practice in this field [1].

By examining A. Comte’s scientific positivism, we can use knowledge and study to advance from the realm of the physical to the realm of the social. This approach aims to establish the boundaries of what ‘we know’ and ‘we do’ [3]. Educational systems are intricate systems that encompass various levels, players, and institutions, all of which have an impact on sustainability and pose challenges for academics [4]. Choosing an academic field of study can sometimes be difficult if you are not prepared for the profession in which you are going to develop. The occupation of a social worker requires a range of inherent and acquired qualities that enable one to thrive in this field. Educational institutions serve the dual purpose of imparting knowledge and fostering the development of students’ value system [5,6].

In this study, we aim to outline a strategy for selecting social work candidates based on their prosocial orientations and multidimensional prosocial behaviours (PSB). Therefore, universities can implement a sustainable education system, based on appropriate strategies for the selection and professional orientation of candidates as future specialists in social work. The use of established methodologies for vocational counselling and selection, together with a set of prosocial principles, can lead to successful and long-term professional integration.

The objectives of this study were:

- Identifying the prosocial tendencies of young individuals pursuing academic study in the social domain;

- An examination and assessment of multidimensional PSB types, measured by prosocial tendencies, which could serve as a career orientation strategy for sustainable education and sustainable professional integration in the social system.

3. Methodology

The purpose of the research was to highlight that the choice of an academic field of social study is based on the orientations and PSB, formed mainly by the family in the development process and are in correlation with the social values and pro-social tendencies required by a sustainable education and a sustainable professional integration.

3.1. Participants and Procedure

To carry out the research, we called on students from the social field, at the Bachelor’s Social Work Program specialisation (only from the University of Bucharest, Romania), N = 238, most students are between 18–22 years old. Students who willingly participated between January and April 2022 were informed about this research during their classes and received more instructions in the introduction section of the online instrument, which they subsequently completed. The students’ participation in this research was voluntary, and at the applied seminars they were informed about the purpose of the research and the issues related to non-involvement in the research were clarified, if they do not want to participate and complete the research instruments, they will not be affected on academic assessments. The students were guaranteed the confidentiality and anonymity of their information, as well as the use of the research findings for scientific objectives.

By completing and sending over the questionnaire to the researchers, the participants consented to participate in this sociological study; participants did not receive any compensation for completing the research instruments.

3.2. Measures

For this study, we created a questionnaire called the Prosocial Orientation Questionnaire (POQ), which consists of three components. These components can be found in Appendix A. The questionnaire was built on several dimensions (3) to see the sources of prosocial orientation in the formation of PSB and the choice of the field of study in social work. Analysing different ways of measuring PSB [23], it was decided to use a self-assessment tool (self-report) of PSB, being the most suitable for study population, students in the field of social work, who have already chosen a field of study. The development of a questionnaire has low costs of time and money, it is easier to administer, it ensures the anonymity of the respondents, and the analysis of the answers is simpler, compared to other research tools that can be applied [61]. Validation of the wording, content and construction of the instrument was verified in a pilot study on a group of 20 students (within an applied seminar), including the translation from the English language, so as not to lose the original meaning. The tool development encompassed:

- Questions regarding profession: the desire to work in the field of social work the origin of the documentation regarding the selection of the field of study, the completion of voluntary internships prior to selecting the academic field of study, by specifying certain institutions from a list (9), the various motivations that served as the foundation for the volunteer internships (7 beneficial factors). In analogy of Likert scale in the responses, ranging from 1, indicating a minimal degree of correspondence, to 5, indicating a substantial degree of correspondence.

- Questions designed to assess the external factors influencing the development of PSB and the inclination towards studying social work, the frequency of encountering and becoming familiar with PSB, and the role of civil society in promoting community well-being. In analogy of Likert scale in the responses, with options such as: ‘1—active role, 2—reduced role, 3—insignificant role’ or ‘1—frequent, 2—sometimes, 3—very rarely’.

- The third component consisted of a Prosocial Tendencies Measure (PTM), developed by G. Carlo and B. A. Randall (2002) [26], which was translated in Romanian. This measure assessed six distinct categories of PSB, organised into subscales: public (items 1,3,5,13), anonymous (8,11,15,19,22), dire (6,9,14), emotional (2,12,17,21), compliant (7,18) and altruism 4,10,16,20,23) (see Appendix A—Questionnaire, III part). The items were intermingled to enhance the objectivity of the responses. A higher score on a certain form of PSB signifies a stronger inclination towards that specific behaviour. During the analysis of the responses, a Likert scale was employed, consisting of five points ranging from (from 1—I do not find myself at all, to 5—I find myself to a great extent). The translation of the instrument was conducted by English teachers participating in this programme, and subsequently analysed by Social Work Programme instructors holding bachelor’s degrees. The purpose of this process was to ensure that the instrument was appropriately adapted to facilitate accurate comprehension among students who are native Romanian speakers. It was important to maintain the fluidity and original meaning of the instrument as proposed by the authors, which involved translating and back-translating the content. For instance, for Public scale we used expressions adapted to the Romanian language; Item 1: I can help others best when people follow me/they look at me. Item 3: When there are other people around me and watching me act, it’s easier for me to help those in difficulty/in need. (original: When other people are around, it is easier for me to help needy others.)

The questionnaires were sent to the participants via email (N = 238) and all data were collected via Google Docs. The empirical data from the research were processed using The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) Software, version 20, using descriptive statistics. Several statistical analyzes were performed for each part of the applied questionnaire. Next, descriptive statistics and correlation analyzes were performed (M., SD, skewness, kurtosis). We used the Pearson’s r coefficient as a criterion for analysing the linear dependence of two or more variables. We used 238 students from the field of study—social work, to analyse the validity of the scale through the method of confirmatory factor analysis, internal consistency and relationships with other factors. Secondly, to examine if there are associations between the factors that can influence PSB and if there are statistically significant differences, we performed the ANOVA test, where high values of F would represent important arguments in the analysis of the orientation factors and in the prosocial tendencies of the studied population correlations and highlighting scales (Cronbach’s Alpha, Pearson, ANOVA, Friedman’s Test, etc.).

4. Results

The study’s findings align with the intended research objectives and hypotheses. In Table 1, we present the demographic characteristics of the participants (N = 238), with Mage = 21.41 years, and the percentage of the female population (89.5%) reflects the female share of those who choose a career in the social field (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic information of participants.

Table 2 displays the results of the initial section of the questionnaire. The skewness values fall within the range of 2. Similarly, the kurtosis values for all the data except items 4 and 5 are also within the range of 2. (Please refer to Table 2 for further details.)

Table 2.

Items of POQ 1–5 and descriptive characteristics.

Upon completing their university education, students are eager to secure employment, as this grants them access to the social protection system in Romania. Most individuals aspire to work in the specific field they are currently training for. The primary sources of documentation for selecting an academic discipline in social work were friends, followed by material obtained from faculty websites, which furnished them with compelling reasons for choosing the subject. Urban residents undertook volunteer activities to assess their altruistic and prosocial abilities, while also becoming more acquainted with such behaviour in public settings. In Romania, the development of NGOs in the field of social work has mainly been achieved in the urban environment; this is due to access to infrastructure, an aspect that allows the provision of these public, private social work services. Prior to their academic studies, students mostly engaged in voluntary activities by participating in programmes given by certain institutions that provided social services for children, the elderly, and people with disabilities. The primary driving force behind the selection of voluntary internships was the aspiration to assist individuals facing hardship (from n = 131–81.6%).

Table 3 presents the results for the second section of the questionnaire, which focused on external factors influencing the development of PSB. The skewness and kurtosis values obtained were within the range of ± 1 (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Items of POQ 6–8 and descriptive characteristics.

We achieved a satisfactory alignment with the empirical data for all aspects. The family plays a significant role (51.7%) in the development of PSB. The majority of students considered the family to be the most crucial factor in shaping PSB and participation in volunteer activities, as opposed to school (49.6%) and civil society (44.5%), which showed insignificant levels of influence.

In their 2002 study, G. Carlo and B. A. Randall [26] raised concerns about the analysis of PSB at a broad, universal level. They demonstrated that there are distinct categories of PSB that can be impacted by numerous individual characteristics and have diverse situational associations. The reasons are derived from studies conducted on several demographic cohorts, starting with teenagers from older age brackets and adults, and subsequently include adolescents from younger and middle age groups [39].

In their initial work, G. Carlo and B. A. Randall (2002) [26] introduced a tool that encompasses four distinct categories of PSB: altruistic PSB, compliant PSB, emotional PSB, and public PSBs. Based on the research, the authors developed a scale consisting of six categories to measure individual variations in PSB among late teens. We also used this tool in our own study to examine the particular patterns of prosocial tendencies in multidimensional prosocial behaviours in Romania.

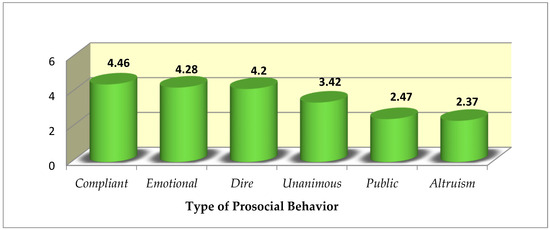

Applying the PTM—23 item scale (G. Carlo and B. A. Randall, 2002 [26]) to the six types of PSB, we obtained high internal consistency and reliability; Cronbach alpha test, mean and SD for each subscale: (1) Public, α = 0.784, M = 2.47, SD = 1.3; (2) Emotional, α = 0.743, M = 4.28, SD = 0.91; (3) Altruism, α = 0.781, M = 2.37, SD = 1.26; (4) Dire, α = 0.697, M = 4.2, SD = 0.91; (5) Compliant, α = 0.767, M = 4.46, SD = 0.79; (6) Unanimous α = 0.840, M = 3.42, SD = 1.28. Using a series of descriptive statistics for the subscales, we obtained skewness values between ±2, except for item 2; for kurtosis of all data were between ±2, except items 2, 7, 18 (see Table 4). The values obtained for both indices (skewness, kurtosis) are acceptable and fall between −2 and +2 and demonstrate univariate normal distribution [62]. Other authors consider normal values for skewness between ±3 and kurtosis is between ±7 and ±10 [63,64].

Table 4.

Descriptive characteristics of PTM’s items.

The highest scores when applying PTM with Mean values above 4, were obtained for three of the six types of PSB and reflect greater tendencies towards them: Compliant (M = 4.46), Emotional (M = 4.28), Dire (M = 4.2), followed by values above the average of 3 for Unanimous (M = 3.42) and values above 2 for the other types: Public (M = 2.47) and Altruism (M = 2.37), where 5 is the maximum value that could have been obtained. The values obtained from representative questions for certain types of PSB are relevant; in each subscale, there are items that have values towards the maximum (see Figure 1; Appendix B). As in other research, emotions are associated with empathic responses, personal tendencies oriented towards others, empathic modes of reasoning [46,51].

Figure 1.

PTM Subscale-Mean values.

Correlation between PTM Subscales

For relevance, we used the Pearson coefficient, which had significant, positive values in the correlation of the dimensions that reflect the innate side, PTM-altruism (5 items) with PTM-saying (3 items), Altruism (5 items), and Anonymity (5 items): values between r = 0.500 and r = 0.709, positive, good correlations: Public and Altruism: r = 0.137 and r = 0.658; Public and Direct, r = 0.268 and r = 0.626. Within the subscales, r had generally positive values, above the mean, r = 0.246 to r = 0.709; PTM-compliant (I7 and I18) = positive correlation with PTM-altruism, r = 0.624 (where p = 0.000 and p < 0.05). The negative correlations had small weights, with values between r = −0.010 and −0.131; examples: PTM-Altruism does not correlate with PTM-Compliance (3 items). PTM-Emotional and Altruism had negative values; they are not supported: I2 (Emotional) with I5 and 13 from S. Public: r = −0.038, p = 0.000; r = −0.089, p = 0.000; I16, I20, I23 (Altruism) with Emotional (I2): r = −0.041, p = 0.000; r = −0.061, p = 0.000; r = −0.120, p = 0.000 (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Relationship between PTM’s subscales.

Several correlations were identified when analysing the orientation gained by specific occurrences in the development of PSB. Q1, when measured using PTM-Public, shows a negative correlation with Pearson coefficient values ranging from r = −0.041 to r = −0.120. The intention to have a job in social work after the completion of studies does not have an influence on the PTM-Public dimension, with a correlation coefficient ranging from r = −0.004 to r = −0.165. Similarly, Q1, when measured using PTM-altruism, also shows negative values with correlation coefficients of r = −0.042 and r = −0.109. This suggests that the intention to work in social work and altruism are not supported. Students are motivated to secure employment upon the completion of their undergraduate degree. By examining the connection between individuals engaged in volunteer activities (55%) and PTM-Public, in relation to their living environment, we discovered strong positive correlations with values of r = 0.318 and r = 0.653. Similarly, when examining the correlation between Q3 and PTM-altruism in relation to the living environment, we found a significant positive correlation with values of r = 0.029 and r = 0.073 (p = 0.01).

The external factors of PSB, including family, school, and civil society, showed a correlation with PTM-altruism, which consists of 5 items: α = 0.677 and ANOVA, with Friedman’s Chi-Square: χ2 = 388.888, p < 0.001. Using PTM-altruism in the correlation with Q8, α = 0.739, in the ANOVA analysis, we obtained χ2 = 258.554, p < 0.001; for the correlation with Q3 with PTM-altruism, α = 0.746, with Friedman’s Chi-Square: χ2 = 299.624, p < 0.001.

Some 49.6% of students regarded the school as actively contributing to the development of PSB, while 41% saw its function as diminished. In contrast, 49.6% believed that civil society played a reduced role in promoting community well-being, while 44.5% saw it as actively involved. Aspects highlighted by the negative correlation with PTM-altruism: values for r = −0.027 and r = −0.046, (p = 0.01). Analysing the percentage of those involved in volunteer activities (Q3–55%) with PTM-altruism, α = 0.711, the correlation is positive, r = 0.005 and r = 0.052 (p = 0.01), according to ANOVA, with Friedman’s Chi-Square: χ2 = 364.256, p < 0.001 (see Appendix C, Table A1 and Table A2(a–d)).

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. Discussion

The selection of university training programmes in the social area is connected to the direction and development of prosocial values and inclinations, which are observed in different PSB. Evaluating one’s prosocial orientations and tendencies can assist in selecting a career in the social sector and determining which university courses to pursue for specialisation.

The family plays a significant role in the development of PSB, as emphasised by many students. It is widely recognised that the family is instrumental in transmitting prosocial values. This finding is further supported by other studies, which have found a clear link between parental practices and various forms of PSB in adolescents. The research findings emphasised the significance of volunteering in the development of PSB, indicating a positive relationship between those engaged in such programmes and their inclination towards prosocial inclinations, as measured by several forms of behaviour, including PTM-altruism and PTM-Public.

The residential setting exhibited a favourable correlation with PTM-altruism, as individuals residing in urban areas had the opportunity to encounter numerous non-governmental organisations, associations, and foundations. This exposure facilitated their engagement in volunteer endeavours, thereby allowing them to assess prosocial values and inclinations, as well as acquaint themselves with the distinctive activities associated with this domain.

School and civil society can contribute to the development and advancement of altruistic principles. However, over 50% of the students polled viewed the functions of these two institutions as reduced and insignificant. This perception is reinforced by a negative link with PTM-altruism, as indicated by five specific items. The motivation for engaging in voluntary activities prior to studying social work was primarily driven by a strong desire to provide aid and support to individuals facing hardships. This value can be linked to Christian principles, specifically personal religious beliefs, where the concept of ‘love thy neighbour’ can serve as an indicator of altruistic behaviour [53]. According to the latest census in Romania, the majority of individuals (72.59%) identified themselves as followers of the Orthodox church. Therefore, it may be inferred that the concept of ‘love thy neighbour’, which involves assisting those facing challenges, is likely instilled within families [54]. Within the family unit, children undergo emotional socialisation, when they engage in interpersonal transactions to express and manage their emotions. During the developmental process, children engage with various environments that contribute to their socialisation, such as school, peer groups, and civil society. However, the most reliable indicators of emotional socialisation can be observed in the reciprocal relationship between parents and children [55].

The connection between happiness and sharing emotions is closely linked to PSB and can serve as a way to enhance children’s emotional and social skills. Girls exhibit a higher propensity than boys to express their emotions to their classmates [56]. These findings can also be attributed to the gender disparity in the field of study of social work at university level, where females are overrepresented. This trend is also evident in the group of respondents, with girls accounting for 89.5%. Available national data [54] indicate a significant predominance of female social workers in Romania. Some 86.5% of individuals employed in this field are women. Examining the gender disparity is a promising field of investigation for future research, while also acting as a limitation in the current study.

The study conducted by Carlo et al. [65] examined the relationship between PSB and factors such as parental inductions, sympathy, and prosocial moral reasoning. The study focused on Mexican-American and European-American adolescents and found no significant differences between the two ethnic groups in terms of the development of prosocial strength. However, it was observed that sympathy had an indirect association with all types of PSB, while prosocial moral reasoning was specifically associated with altruistic, anonymous, and public PSB.

With respect to the PTM subscales, there was consistent evidence of validity and significant correlations with other factors. These findings align with the results obtained by Carlo et al. [24], who also designed the instrument for use with students (M = 19.9 years).

And other studies that had students from Greek universities (N = 484) as their study population highlighted that social sciences students, female, had more positive attitudes towards PSB, compared to the male population. The same instrument PTM scale was applied, which was associated with other factors such as individualism–collectivism (Auckland’s Individualism Collectivism Scale), and the correlation analysis indicated high positive values between 4 types of PSB: altruism, emotional, compliant, and anonymous with the type of behaviour—collectivism [66].

Applying the same scale—PTM scales, on Iranian students (N = 182) with the aim of validating this instrument, in correlation with other factors (empathy, religiosity and social desirability), revealed positive and significant correlations for three subscales (Emotional, Anonymous, Altruism) with Empathy and negative relationships between Public and Empathy. There were no differences between the two genders, but religion was highlighted in the correlation with Compliant and Anonymous [67]. Hardy (2006) [68] similarly emphasized this outcome in his study involving students (N = 91, Mage = 21.89), where PSB showed a positive correlation with both empathy and prosocial identity. Other studies (Hardy and Carlo, 2005) that analysed PSB also on adolescents (N = 142, Mage = 16.8) did not find a positive relationship between religiosity and Public, Dire and Emotional PSB, but Altruistic, Compliant, and Anonymous PSBs were positively associated [69].

5.2. Conclusions

The prosocial orientations identified in young people studying in the social field were directly related to the family, which is responsible for transmitting prosocial values. Involvement in volunteering activities influences the choice of the field of study and a career, aspects highlighted by the values obtained in correlation with items from the PTM scale, such as PTM-altruism and PTM-Public. The environment of residence is directly related to the formation of PSB, as young people from the urban environment were more familiar with the social field, being involved in social campaigns, compared to those from the rural environment. The measurement of prosocial tendencies revealed high values for three of the six types of PSB highlighted in the PTM scale: Compliant, Emotional, and Dire (where M had values above 4.20 to 5, which represented the maximum value). The current study reveals positive correlations among the subscales that support direct PSB: Compliant and Dire; Anonymous and Compliant; Anonymous and Dire; Emotional and Compliant; Emotional and Dire; Public and Dire; and Altruism and Public.

The findings of this study offer evidence of the effectiveness of the PTM in evaluating prosocial tendencies. This supports the idea that PSB is multidimensional, as postulated by Carlo and Randall (2002) [26], and is demonstrated by the correlations observed in young individuals pursuing a social career. Furthermore, other research conducted with the same instrument yielded comparable outcomes, for instance, when examining Iranian University students while considering additional factors such as cultural background [67]. Van Langen et al. have demonstrated that emotions and empathy (cognitive and affective) are directly related to PSB [70].

The cognitive and prosocial development of young individuals begins early on, through several means (such as family, school, friend groups, etc.) and continues throughout their entire lives. The family remains the most important institution in the prosocial orientation of young people, creating a conductive environment for prosocial development, orientation, and career choice, and the choice of university studies is in line with these factors. The use of these tools in assessing prosocial orientations and tendencies will also consider the correlation with other factors: internal factors related to the individual, and external factors related to family, community, and cultural influences.

5.3. Practical Implications

The selection of an academic discipline in the social sciences should align with one’s social ideals and patterns of prosocial conduct that have been developed during childhood through many influences such as family, school, university, peer groups, and job. The orientations and prosocial tendencies of young individuals who have opted to pursue further education and specialise in the social field can be assessed using the employed instruments. The results of the assessment indicate high values on specific scales. We suggest adopting techniques to assess prosocial orientations and tendencies while considering various options for career orientation in school and long-term professional integration.

The development of PSB, based on social values, altruism, and empathy, taking into account national, cultural-specific, and professional contexts, can serve as fundamental indicators for guiding one’s professional orientation towards a social field of study at the university level, as well as for pursuing and remaining in the practice of the profession (in the social domain).

The research results show that the tools can be used in the process of counselling and vocational guidance of future candidates for university studies in the social field (social work), by evaluating prosocial orientations and tendencies. Thus, if professional development and training is based on a series of prosocial values and trends (previously evaluated), the chances of a sustainable professional integration increase, by entering the system of protection and social services of well-trained and motivated professionals. Staying in the profession is a challenge, both for professionals and for social work systems, which for sustainable development must rely on the expertise of professionals (social workers, in our case). For a sustainable educational integration (Goal 4—Quality education), we must have a human resource that is motivated, oriented towards the social field, thus contributing to the development of the social work system (‘Goal 1—No poverty’ and ‘Goal 2—Zero hunger’) [1,2].

5.4. Limitations and Future Lines of Research

The subjects participating in the study were predominantly female. The investigation of this subject matter was undertaken with a focus on gender disparity, so presenting a viable avenue for future scholarly inquiry. Furthermore, we suggest expanding the sample population in future studies to include students from various higher education institutions, such as those in technical and sports fields. This will enable the examination of a broader range of external factors, in addition to internal factors, that contribute to the development of PSB. The use of suitable measuring instruments, specifically the Prosocial and Antisocial Behaviour in Sports Scale (PABSS) in its German version, yielded varying outcomes based on gender and participation in different sports disciplines, including football, rugby/soccer, hockey/football, basketball, and handball [71].

Research results could be attributed to a specific geographic area or the use of these tools. Expanding the geographical areas of study but also the research tools, such as the influence of personality factors [72], could lead to more general results.

We will continue the current research taking into account some additional factors: more diverse samples made up of undergraduate students from high schools with a technical profile, where the male population is in greater proportion (compared to girls) and is oriented towards technical university fields. Another proposal would be to examine other additional factors that can influence PSB, such as contact with social work services, by evaluating the prosocial orientation of young people from vulnerable backgrounds, beneficiaries of social services provided by professionals in the social protection system.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.P. and M.A.; methodology, G.N.; software, M.P., M.A. and G.N.; validation, M.P., M.A. and G.N.; formal analysis, M.P., M.A. and G.N.; investigation, M.P. and M.A.; resources, M.P., M.A. and G.N.; data curation, M.P., M.A. and G.N.; writing—original draft preparation, M.P., M.A. and G.N.; writing—review and editing, M.P., M.A. and G.N.; visualization, M.P. and M.A.; supervision, G.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in the article itself.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix B. Internal Consistency of PTM’s Subscales and M, SD for Each Item

| Factors/Subscale | Mean | Cronbach’s Alpha | Items | Mean | SD |

| 5. Public | 2.478 | 0.784 | 1 | 3.21 | 1.337 |

| 3 | 2.60 | 1.428 | |||

| 5 | 2.24 | 1.317 | |||

| 13 | 1.86 | 1.118 | |||

| 2. Emotional | 4.284 | 0.743 | 2 | 4.68 | 0.656 |

| 12 | 4.42 | 0.867 | |||

| 17 | 3.94 | 1.085 | |||

| 21 | 4.09 | 1.034 | |||

| 6. Altruism | 2.376 | 0.781 | 4 | 3.10 | 1.391 |

| 10 | 2.52 | 1.321 | |||

| 16 | 2.26 | 1.236 | |||

| 20 | 2.03 | 1.211 | |||

| 23 | 1.211 | 1.174 | |||

| 3. Dire | 4.203 | 0.697 | 6 | 4.391 | 0.854 |

| 9 | 4.33 | 0.901 | |||

| 14 | 3.89 | 1.000 | |||

| 1. Compliant | 4.458 | 0.767 | 7 | 4.47 | 0.761 |

| 18 | 4.45 | 0.819 | |||

| 4. Unanimous | 3.422 | 0.840 | 8 | 3.68 | 1.337 |

| 11 | 3.65 | 1.266 | |||

| 15 | 3.50 | 1.252 | |||

| 19 | 3.51 | 1.218 | |||

| 22 | 2.77 | 1.351 |

Appendix C

Table A1.

ANOVA-PTM Scale.

Table A1.

ANOVA-PTM Scale.

| Subscale | ITEMS | Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | F | Sig. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P U B L I C | I1 | Between Groups | 3.085 | 1 | 3.085 | 1.732 | 0.189 |

| Within Groups | 420.411 | 236 | 1.781 | ||||

| Total | 423.496 | 237 | |||||

| I3 | Between Groups | 4.191 | 1 | 4.191 | 2.065 | 0.152 | |

| Within Groups | 478.889 | 236 | 2.029 | ||||

| Total | 483.080 | 237 | |||||

| I5 | Between Groups | 0.032 | 1 | 0.032 | 0.018 | 0.892 | |

| Within Groups | 411.317 | 236 | 1.743 | ||||

| Total | 411.349 | 237 | |||||

| I13 | Between Groups | 0.578 | 1 | 0.578 | 0.461 | 0.498 | |

| Within Groups | 295.846 | 236 | 1.254 | ||||

| Total | 296.424 | 237 | |||||

| E M O T I O N A L | I2 | Between Groups | 0.080 | 1 | 0.080 | 0.185 | 0.667 |

| Within Groups | 101.651 | 236 | 0.431 | ||||

| Total | 101.731 | 237 | |||||

| I12 | Between Groups | 0.330 | 1 | 0.330 | 0.438 | 0.509 | |

| Within Groups | 177.809 | 236 | 0.753 | ||||

| Total | 178.139 | 237 | |||||

| I17 | Between Groups | 4.188 | 1 | 4.188 | 3.595 | 0.059 | |

| Within Groups | 274.988 | 236 | 1.165 | ||||

| Total | 279.176 | 237 | |||||

| I21 | Between Groups | 0.101 | 1 | 0.101 | 0.094 | 0.759 | |

| Within Groups | 253.046 | 236 | 1.072 | ||||

| Total | 253.147 | 237 | |||||

| A L T R U I S M | I4 | Between Groups | 0.996 | 1 | 0.996 | 0.514 | 0.474 |

| Within Groups | 457.781 | 236 | 1.940 | ||||

| Total | 458.777 | 237 | |||||

| I10 | Between Groups | 1.156 | 1 | 1.156 | 0.662 | 0.417 | |

| Within Groups | 412.239 | 236 | 1.747 | ||||

| Total | 413.395 | 237 | |||||

| I16 | Between Groups | 0.008 | 1 | 0.008 | 0.005 | 0.943 | |

| Within Groups | 362.316 | 236 | 1.535 | ||||

| Total | 362.324 | 237 | |||||

| I20 | Between Groups | 0.931 | 1 | 0.931 | 0.633 | 0.427 | |

| Within Groups | 346.800 | 236 | 1.469 | ||||

| Total | 347.731 | 237 | |||||

| I23 | Between Groups | 0.278 | 1 | 0.278 | 0.201 | 0.654 | |

| Within Groups | 326.382 | 236 | 1.383 | ||||

| Total | 326.660 | 237 | |||||

| D I R E | I6 | Between Groups | 5.386 | 1 | 5.386 | 7.599 | 0.006 |

| Within Groups | 167.273 | 236 | 0.709 | ||||

| Total | 172.660 | 237 | |||||

| I9 | Between Groups | 1.721 | 1 | 1.721 | 2.129 | 0.146 | |

| Within Groups | 190.716 | 236 | 0.808 | ||||

| Total | 192.437 | 237 | |||||

| I14 | Between Groups | 3.980 | 1 | 3.980 | 4.029 | 0.046 | |

| Within Groups | 233.179 | 236 | 0.988 | ||||

| Total | 237.160 | 237 | |||||

| C O M P L I A N T | I7 | Between Groups | 0.441 | 1 | 0.441 | 0.761 | 0.384 |

| Within Groups | 136.790 | 236 | 0.580 | ||||

| Total | 137.231 | 237 | |||||

| I18 | Between Groups | 0.000 | 1 | 0.000 | 0.000 | 0.987 | |

| Within Groups | 158.895 | 236 | .673 | ||||

| Total | 158.895 | 237 | |||||

| A N O N Y M O U S | I8 | Between Groups | 0.900 | 1 | 0.900 | 0.503 | 0.479 |

| Within Groups | 422.465 | 236 | 1.790 | ||||

| Total | 423.366 | 237 | |||||

| I11 | Between Groups | 0.008 | 1 | 0.008 | 0.005 | 0.944 | |

| Within Groups | 380.047 | 236 | 1.610 | ||||

| Total | 380.055 | 237 | |||||

| I15 | Between Groups | 8.256 | 1 | 8.256 | 5.364 | 0.021 | |

| Within Groups | 363.240 | 236 | 1.539 | ||||

| Total | 371.496 | 237 | |||||

| I19 | Between Groups | 4.566 | 1 | 4.566 | 3.106 | 0.079 | |

| Within Groups | 346.917 | 236 | 1.470 | ||||

| Total | 351.483 | 237 | |||||

| I22 | Between Groups | 4.496 | 1 | 4.496 | 2.481 | 0.117 | |

| Within Groups | 427.794 | 236 | 1.813 | ||||

| Total | 432.290 | 237 | |||||

Table A2.

(a,b,c,d): Correlations Altruism-PTM with questions regarding prosocial orientation.

Table A2.

(a,b,c,d): Correlations Altruism-PTM with questions regarding prosocial orientation.

| ||||||

| Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | Friedman’s Chi-Square | Sig | ||

| Between People | 676.624 | 237 | 2.855 | |||

| Within People | Between Items | 466.210 a | 7 | 66.601 | 388.888 | 0.000 |

| Residual | 1531.040 | 1659 | 0.923 | |||

| Total | 1997.250 | 1666 | 1.199 | |||

| Total | 2673.874 | 1903 | 1.405 | |||

| Grand Mean = 2.09 | ||||||

| a Kendall’s coefficient of concordance W = 0.174. | ||||||

| ||||||

| Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | Friedman’s Chi-Square | Sig | ||

| Between People | 878.239 | 237 | 3.706 | |||

| Within People | Between Items | 317.978 a | 5 | 63.596 | 258.554 | 0.000 |

| Residual | 1145.522 | 1185 | 0.967 | |||

| Total | 1463.500 | 1190 | 1.230 | |||

| Total | 2341.739 | 1427 | 1.641 | |||

| Grand Mean = 2.25 | ||||||

| a Kendall’s coefficient of concordance W = 0.136. | ||||||

| ||||||

| Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | Friedman’s Chi-Square | Sig | ||

| Between People | 867.406 | 237 | 3.660 | |||

| Within People | Between Items | 370.291 a | 5 | 74.058 | 299.624 | 0.000 |

| Residual | 1100.375 | 1185 | 0.929 | |||

| Total | 1470.667 | 1190 | 1.236 | |||

| Total | 2338.073 | 1427 | 1.638 | |||

| Grand Mean = 2.22 | ||||||

| a Kendall’s coefficient of concordance W = 0.158. | ||||||

| ||||||

| Sum of Squares | df | Mean Square | Friedman’s Chi-Square | Sig | ||

| Between People | 750.739 | 237 | 3.168 | |||

| Within People | Between Items | 445.664 a | 6 | 74.277 | 364.256 | 0.000 |

| Residual | 1301.479 | 1422 | 0.915 | |||

| Total | 1747.143 | 1428 | 1.223 | |||

| Total | 2497.882 | 1665 | 1.500 | |||

| Grand Mean = 2.13 | ||||||

| a Kendall’s coefficient of concordance W = 0.178. | ||||||

References

- United Nations. The Sustainable Development Goals Report, Special Edition. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2023/The-Sustainable-Development-Goals-Report-2023.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2023).

- United Nations. Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015. In Transforming our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 12–21. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/generalassembly/docs/globalcompact/A_RES_70_1_E.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2023).

- Comte, A. The Positive Philosophy of Auguste Comte-The Law of the Three Stages. eNotes Publishing Ed. eNotes Editorial, eNotes.com. 2000. Available online: https://www.enotes.com/topics/positive-philosophy-auguste-comte#in-depth-the-law-of-the-three-stages (accessed on 1 November 2023).

- Fleaca, B.; Fleaca, E.; Maiduc, S. Framing Teaching for Sustainability in the Case of Business Engineering Education: Process-Centric Models and Good Practices. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, E.W.L. Revisiting the Concept of Values Taught in Education through Carroll’s Corporate Social Responsibility. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatpinyakoop, C.; Hallinger, P.; Showanasai, P. Developing Capacities to Lead Change for Sustainability: A Quasi-Experimental Study of Simulation-Based Learning. Sustainability 2022, 14, 10563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, R.; Hart, D. Examining the Pro-Self and Prosocial Components of a Calling Outlook: A Critical Review. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Piers, B. Commitment; Routledge: Oxfordshire, UK, 2010; p. 67. [Google Scholar]

- Elangovan, A.R.; Pinder, C.C.; McLean, M. Callings and organizational behavior. J. Vocat. Behav. 2010, 76, 428–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, P.C.; Guo, Y.; Cai, Q.; Guo, H. Proactive Career Orientation and Subjective Career Success: A Perspective of Career Construction Theory. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savickas, M.L. The Theory and Practice of Career Construction. In Career Development and Counseling: Putting Theory and Research to Work, 2nd ed.; Brown, S.D., Lent, R.W., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 42–70. [Google Scholar]

- Defillippi, R.J.; Arthur, M.B. The Boundaryless Career: A Competency-Based Perspective. J. Organ. Behav. 1994, 15, 307–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charmaz, K. Constructing Grounded Theory; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Akosah-Twumasi, P.; Alele, F.; Emeto, T.I.; Lindsay, D.; Tsey, K.; Malau-Aduli, B.S. ‘Preparing Them for the Road’: African Migrant Parents’ Perceptions of Their Role in Their Children’s Career Decision-Making. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rüschenpöhler, L.; Hönig, M.; Küsel, J.; Markic, S. The Role of Gender and Culture in Vocational Orientation in Science. Educ. Sci. 2020, 10, 240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Encouraging Student Interest in Science and Technology Studies; OECD: Paris, France, 2008; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/education/school/programmeforinternationalstudentassessmentpisa/35995145.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2023).

- Plana-Farran, M.; Blanch, À.; Solé, S. The Role of Mindfulness in Business Administration (B.A.) University Students’ Career Prospects and Concerns about the Future. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weng, Q.D.; McElroy, J. Organizational career growth, affective occupational commitment and turnover intentions. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 256–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rożnowski, B.; Zarzycka, B. Centrality of Religiosity as a Predictor of Work Orientation Styles and Work Engagement: A Moderating Role of Gender. Religions 2020, 11, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asokan, S.; GeethaPriya, P.R.; Natchiyar, N.; Viswanath, S. Piagetian’s principles on moral development and its influence on the oral hygiene practices of Indian children: An embedded mixed-method approach. Int. J. Paediatr. Dent. 2023, 33, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawley, P.H. Prosocial and coercive configurations of resource control in early adolescence: A case for the well-adapted Machiavellian. Merrill-Palmer Q. 2003, 49, 279–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boxer, P.; Tisak, M.S.; Goldstein, S.E. Is it bad to be good? An exploration of aggressive and prosocial behavior subtypes in adolescence. J. Youth Adolesc. 2004, 33, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martí-Vilar, M.; Corell-García, L.; Merino-Soto, C. Systematic review of prosocial behavior measures. Rev. Psicol. 2019, 37, 349–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inderbitzen, H.M.; Foster, S.L. The Teenage Inventory of Social Skills: Development, reliability, and validity. Psychol. Assess. 1992, 4, 451–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprara, G.V.; Pastorelli, C. Early emotional instability, prosocial behavior, and aggression: Some methodological aspects. Eur. J. Personal. 1993, 7, 19–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlo, G.; Randall, B.A. The Development of a Measure of Prosocial Behaviours for Late Adolescents. J. Youth Adolesc. 2002, 31, 31–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caprara, G.V.; Steca, P.; Zelli, A.; Capanna, C. A new scale for measuring adults’ prosocialness. Eur. J. Psychol. Assess. 2005, 21, 77–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra, Á.; Oliva, A.; Sánchez-Queija, I. Development of emotional autonomy from adolescence to young adulthood in Spain. J. Adolesc. 2015, 38, 57–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Rodríguez, M.; Suárez-Pére, C.D. Construcción y validación de una escala para evaluar habilidades prosociales en adolescentes. In Proceedings of the XI Congreso Nacional de Investigación Educativa, del Consejo Mexicano de Investigación Educativa, Coyoacán, Mexico, 7–11 November 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Piliavin, J.A.; Charng, H.-W. Altruism: A review of recent theory and research. Annu. Rev. Sociol. 1990, 16, 27–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazdin, A.E. Encyclopaedia of Psychology; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2000; Volume 6, pp. 130–131. [Google Scholar]

- Hirani, S.; Ojukwu, E.; Bandara, N.A. Understanding the Role of Prosocial Behaviour in Youth Mental Health: Findings from a Scoping Review. Adolescents 2022, 2, 358–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felaco, C.; Zammitti, A.; Marcionetti, J.; Parola, A. Career Choices, Representation of Work and Future Planning: A Qualitative Investigation with Italian University Students. Societies 2023, 13, 225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenberg, N.; Fabes, R.A.; Spinrad, T.L. Prosocial development. In Handbook of Child Psychology: Vol. 3. Social, Emotional, and Personality Development, 6th ed.; Damon, W., Lerner, R.M., Eisenberg, N., Eds.; John Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 646–718. [Google Scholar]

- Pantea, M.-C. Understanding non-participation: Perceived barriers in cross-border volunteering among Romanian youth. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2015, 20, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberts, W.; Strayer, J. Empathy, emotional expressiveness, and prosocial behavior. Child Dev. 1996, 67, 449–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoma, S.J.; Rest, J.R.; Davison, M.L. Describing and Testing a Moderator of the Moral Judgment and Action Relationship. J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 61, 659–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, S.A.; Carlo, G. Identity as a Source of Moral Motivation. Hum. Dev. 2005, 48, 232–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlo, G.; Hausmann, A.; Christiansen, S.; Randall, B.A. Sociocognitive and behavioral correlates of a measure of prosocial tendencies for adolescents. J. Early Adolesc. 2003, 23, 107–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batson, C.D. The Altruism Question: Toward a Social Psychological Answer; Lawrence Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Hardy, J. Speaking clearly: A critical review of the self-talk literature. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2006, 7, 81–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosmides, L.; Tobby, J. Cognitive Adaptations for Social Exchange. In The Adapted Mind: Evolutionary Psychology and the Generation Culture; Barkow, J.H., Cosmides, L., Tooby, J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Goldman, A.I. Empathy, Mind and Morals. In Mental Simulation; Davies, M., Stone, T., Eds.; Blackwell Publishers Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 1995; pp. 98–99. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A. The Theory of Moral Sentiments; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002; pp. 57–59. [Google Scholar]

- Carlo, G.; Eisenberg, N.; Troyer, D.; Switzer, G.; Speer, A.L. The altruistic personality: In what contexts is it apparent? J. Personal. Soc. Psychol. 1991, 61, 450–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlo, G.; Eisenberg, N.; Knight, G.P. An objective measure of adolescents’ prosocial moral reasoning. J. Res. Adolesc. 1992, 2, 331–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barton, C.; Hart, R. The Experience of Self-Transcendence in Social Activists. Behav. Sci. 2023, 13, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voicu, M.; Voicu, B. Volunteering in Romania. In Values Volunteering. Nonprofit and Civil Society Studies; Dekker, P., Halman, L., Eds.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Waal, F. The Age of Empathy Nature’s Lessons for a Kinder Society; Souvenir Press: London, UK, 2009; p. 105. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson, Y. Interpersonal Understanding and Theory of Mind; Abo Akademi University Press: Abo, Finland, 2014; pp. 78–79. [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester, D.; Goldfarb, J.; Cantrell, D. Self-presentation when sharing with friends and nonfriends. J. Early Adolesc. 1992, 12, 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, D.A.; Penner, L.A.; Dovidio, J.F.; Piliavin, J.A. The Psychology of Helping and Altruism: Problems and Puzzles; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1995; pp. 67–70. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, T.K.Y.; Konishi, C.; Zhang, M.Y.Q. Maternal and Paternal Parenting Practices and Prosocial Behaviours in Hong Kong: The Moderating Roles of Adolescents’ Gender and Age. J. Early Adolesc. 2022, 42, 671–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronfenbrenner, U. Making Human Beings Human: Bioecological Perspectives on Human Development; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2004; pp. 153–157. [Google Scholar]

- Syahril, Y.S.; Ilfiandra, A.S. The Effect of Parenting Patterns and Empathy Behaviour on Youth Prosocial. Int. J. Instr. 2020, 13, 223–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Duan, Q.; Long, H. How do parents influence student creativity? Evidence from a large-scale survey in China. Think. Ski. Creat. 2022, 46, 101134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbot, B.; Brianna, H. Chapter 5—Creativity and Identity Formation in Adolescence: A Developmental Perspective. In Explorations in Creativity Research, The Creative Self; Karwowski, M., James, C.K., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; pp. 87–98. ISBN 9780128097908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gajda, A.; Karwowski, M.; Beghetto, R.A. Creativity and academic achievement: A meta-analysis. J. Educ. Psychol. 2017, 109, 269–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Pan, Y.; Luo, X.; Wang, L.; Pang, W. Active Procrastination and Creative Ideation: The Mediating Role of Creative Self-Efficacy. Personal. Individ. Differ. 2017, 119, 227–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamannaeifar, M.R.; Motaghedifard, M. Subjective well-being and its sub-scales among students: The study of role of creativity and self-efficacy. Think. Ski. Creat. 2014, 12, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillham, B. Developing a Questionnaire; A & C Black: London, UK, 2008; pp. 46–51. [Google Scholar]

- George, D.; Mallery, P. SPSS for Windows Step by Step: A Simple Guide and Reference 17.0 Update, 10th ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.A. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 52–54. [Google Scholar]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 34–38. [Google Scholar]

- Carlo, G.; Knight, G.P.; McGinley, M.; Hayes, R. The roles of parental inductions, moral emotions, and moral cognitions in prosocial tendencies among Mexican American and European American early adolescents. J. Early Adolesc. 2011, 31, 757–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lampridis, E.; Papastylianou, D. Prosocial behavioural tendencies and orientation towards individualism–collectivism of Greek young adults. Int. J. Adolesc. Youth 2017, 22, 268–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azimpour, A.; Neasi, A.; Shehni-Yailagh, M.; Arshadi, N. Validation of ‘Prosocial Tendencies Measure’ in Iranian University Students. J. Life Sci. Biomed. 2012, 2, 34–42. Available online: http://jlsb.science-line.com/34 (accessed on 18 December 2023).

- Hardy, S.A. Identity, Reasoning, and Emotion: An Empirical Comparison of Three Sources of Moral Motivation. Motiv. Emot. 2006, 30, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardy, S.A.; Carlo, G. Religiosity and prosocial behaviours in adolescence: The mediating role of prosocial values. J. Moral Educ. 2005, 34, 231–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Langen, M.A.M.; Stams, G.J.J.M.; Van Vugt, E.S.; Wissink, I.B.; Asscher, J.J. Explaining Female Offending and Prosocial Behavior: The Role of Empathy and Cognitive Distortions. Laws 2014, 3, 706–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohnsmeyer, J. Deutsche Adaptation der Prosocial and Antisocial Behaviour in Sport Scale (PABSS). Diagnostica 2018, 64, 180–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, A.A.; Hamsan, H.H.; Ma’rof, A.A. How do Personality Factors Associate with Prosocial Behavior? The Mediating Role of Empathy. Int. J. Acad. Res. Bus. Soc. Sci. 2020, 10, 206–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).