Abstract

This study conducts a chronological analysis of six mixed-use commercial complexes in the Seoul metropolitan area and examines their planning characteristics and patterns of change. The analysis reveals the following changes. The spatial composition of these complexes is shifting away from large anchor type commercial facilities to small local commercial facilities. Their circulations and arrangement are shifting to consideration for non-consumption tendencies, and circular and three-dimensional connections between each space are emphasized. Central spaces are shifting from a large single center to small multi-centers, and the utilization of central spaces for events and performances is increasing. Concepts that stimulate visitors’ interest and non-daily experiences are being expanded, which include the use of new themes, such as natural motifs, and the reproduction of classical streets in the space, corridors, colors, and material planning. Based on their changing patterns, this study predicted such complexes’ direction of change. First, they will expand their role as the center of the local community. Second, they will bolster their linkage with local streets and expand the street-type circulation plan. Third, small multi-center spaces and themed external spaces will increase. Fourth, non-consumption and non-daily planning elements will increase.

1. Introduction

1.1. Purpose of This Study

The attachment of people towards shopping centers is propelled by the changes of lifestyle, pattern of motorized transportation and intensive activities in shopping centers [1]. The management of physical and social facilities in shopping center can influence the enhancement of the functional values and create a sense of place and intense social relationships among visitor [2]. A particularly representative type of architecture that reflects this altered consumer culture of the modern era is commercial complex. As subway access areas around the Seoul metropolitan area are turning into commercial and cultural centers, commercial complexes are providing experiences at various levels, such as leisure-oriented cultural consumption, as well as traditional consumption. Additionally, they contain various facilities such as residences, businesses, cultural venues, and entertainment venues. The commercial complex is, thus, a space that symbolizes modern consumption culture and partly fulfilling social demands [3].

Recent prior research on commercial facilities were mainly based on their changes due to variations in the commercial environment. Examples include designing the skeletal sections of the spaces in shopping centers being made possible through the introduction of the main criteria on the creation of interactions [4], ensuring the integration and sustainability of e-commercial activities in virtual spaces and traditional commercial activities in urban commercial centers [5], identifying public places that influence consumer opinions of shopping malls to create a sense of culture in public space design [6].

However, there have been many previous studies based on commercial facilities, but it was difficult to find a study that reflected the trend of mixed-use commercial complex, which has recently increased in international demand, and a study that analyzed them chronologically.

Based on this background, this study conducts a chronological analysis of mixed-use commercial complexes in the Seoul metropolitan area and examines their planning characteristics and patterns of change (Figure 1). This is done so that this study can be referred to in the future in order to design mixed-use commercial complexes that are differentiated and highly satisfying.

Figure 1.

Research framework for the study.

1.2. Method and Scope of This Study

First, factors that affect the changes in commercial facilities and the major elements of mixed-use commercial complexes and their elements for activation were identified through a literature review. Based on these factors, representative commercial complex facilities were selected chronologically. Relevant literature and visiting surveys accompanied each selected case.

Based on this, the study proposed measures to revitalize mixed-use commercial complexes by elucidating the characteristics of their changes and identifying meaningful facts related to architectural planning.

2. Theoretical Considerations

2.1. Changes in Commercial Space

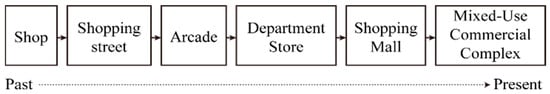

The shift from individual stores to collective commercial streets resulted in the horizontal and linear expansion around the streets. Consequently, the arcade-type conventional market, which made the commercial street semi-indoors, developed from region to region. Later, the department store was built vertically and connected to the commercial spaces using escalators and elevators. With the emergence of mixed-use commercial complexes that connect commercial spaces to various facilities, the concept of a space layout based on the commercial environment of central space, anchors, and sub-anchors, and the circulation and activation measures for the connection and communication of each commercial, cultural, and entertainment facilities emerged as important elements of the mixed-use commercial complex plan (Figure 2). [7].

Figure 2.

Chronological Trend of the Commercial Space.

2.2. Elements for Activating Mixed-Use Commercial Complexes

Studies on mixed-use commercial complexes mainly focus on vitalization measures. Various analyses have presented location, planning, operation, and management as the main elements of activation [8]. However, this study focused specifically on planning. By emphasizing the urban aspect of commercial complexes, the method of deriving planning elements from the five elements of city planning suggested by Kevin Lynch: edge, path, node, landmark, and district is universally applied. In terms of mixed-use commercial complexes, there are certain key components that affect the activation of a complex, such as the node (spatial composition), the path (circulation plan), and the landmarks (central space), which were adopted from the perspective of analysis [9] (Table 1). The first among these are the complex’s recruiting tenants, anchor tenants (Refers to a key store that attracts customers and determines the floating population of the business district. Some examples are: large bookstores, multiplex cinemas, large supermarkets, and clothing brand stores) [10], and its spatial composition. The movement of pedestrians and the selection of circulations serve as another integral factor. Lastly, a public (central) space affects the activation of a complex [11]. These three factors have a direct impact on the revitalization of mixed-use commercial complexes based on complexity and collectivity [9].

Table 1.

Elements for activation.

3. Case Selection and Analysis

3.1. Selection of Cases

Since the opening of COEX (2000)—Korea’s first mixed-use commercial complex––the commercial complex, centered around metropolitan subway access areas, has developed significantly from its initial stage (COEX Mall, I-Park Mall). Due to economic development, the increase in the urban population, and the proliferation of subways, commercial complexes underwent a development stage where commercial, business, and cultural functions were integrated and expanded (Time Square, D-Cube City). They ultimately reached a completion stage where functions such as commerce, residence, culture, and leisure were accommodated (Mecenatpolis, Gwanggyo Alley Way). In this study, representative mixed-use commercial complexes, located in the Seoul metropolitan area, were selected chronologically (2000–2019) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Case Study, (GFA and Floors are calculated only for commercial facilities).

3.2. Elements for Activation of the Selected Cases

In this section, the elements that affect the activation of the selected complexes—their spatial compositions, circulation plans, and central spaces—were investigated. With regard to spatial composition, the study investigated the types and arrangements of anchor tenants that were combined in accordance with the characteristics of the major facilities and the areas they were located in. To ensure perceptibility, directionality, and continuity of the facilities by ameliorating the disconnection between facilities, which is a disadvantage of large commercial complexes, the ways in which they connected their circulation were explored. Additionally, the location, size, and shape of their central spaces were examined in order to assess the status of the central space as a whole within these complexes.

- (1)

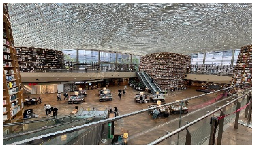

- COEX Mall (Initial stage/2000)

It was the largest underground shopping space in Asia (Table 3). It consists of four basement floors, four above ground floors (convention center, department store, multiplex, aquarium), a trade tower (54 floors above ground), and a hotel, which were built along with the convention center for the third ASEM (Asia-Europe Meeting) Summit in 2000. With the convention center at its center, anchor facilities such as offices (connected to the subway station) and hotels are placed on both its sides and are connected to commercial malls to promote movement across the entire facility through target routes. The routes consist of a main corridor, a commercial mall, and a number of complex labyrinthine rear corridors. However, it lacks perceptibility, directionality, and continuity due to the lack of connectivity between corridors. In 2000, its small central space was planned to be used only as a corridor during the opening. However, in 2015, the central space was renovated into a 2800-square-meter, two-story open library.

Table 3.

Case Study, COEX Mall [14]/Source: Author.

- (2)

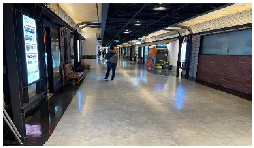

- I-Park Mall (Initial stage/2004)

It is a complex that is connected to an express train station (Table 4). It is composed of department stores, shopping malls, duty-free shops, multiplexes, large supermarkets, large bookstores, and offices. It has three underground floors and 7 floors above ground. Its facilities are arranged around the atrium, which also serves as a waiting room for express trains. The commercial facilities are located on the lower floors, whereas duty-free shops, multiplexes, and offices are on the higher floors. As a result, the target routes bring in traffic from the lower floors to the higher ones. The internal corridor serves as a typical example of the design of early commercial complexes and has a department store-style simple corridor in order to maximize its rental area. Although there is a central space that functions as the station’s waiting room and a public space that enables vertical movement, there is a lack of connection between each corridor. Additionally, a visual and organic linkage is absent, and the activity of the space is insufficient for it to be considered a central public space in the modern sense.

Table 4.

Case Study, I-Park Mall [15]/Source: Author.

- (3)

- Time Square (Development stage/2009)

It is a building with two underground floors and six above ground ones (Table 5). It was built on a site that was formerly a textile factory, and it serves as an urban entertainment cultural space that combines commerce, business, culture, and leisure through facilities such as multiplexes, department stores, large supermarkets, wedding halls, hotels, large bookstores, and offices. One of its anchor facilities—a department store—is located near the entrance to Yeongdeungpo Station. By placing a large supermarket, a multiplex, and a large bookstore on the other side, the two anchors are connected using one main corridor and two or three rear corridors. A hotel and convention center are located at the end of the entire facility and serve as sub-anchors. Its central public space—a large atrium that penetrates the above ground floors—was made its visual center, and the center of the vertical and horizontal circulation, by placing it between the main and sub-anchors. The main corridor was planned as a keyhole section (When planning the main corridor of the shopping mall, the opening becomes bigger in the form of a key hole, increasing perceptibility through visual interpenetration between floors) to promote the commercial environment through visual interpenetration between each floor.

Table 5.

Case Study, Time Square [16]/Source: Author.

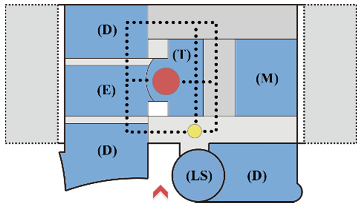

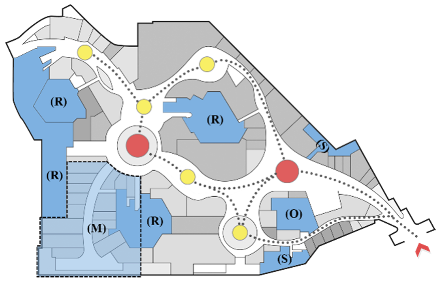

- (4)

- D-Cube City (Development stage/2011)

Built on a site that was formerly a coal briquette factory, it is an urban entertainment cultural complex that consists of commercial, business, and cultural facilities (Table 6), such as high-rise residential buildings, multiplexes, department stores, large supermarkets, musical performance halls, hotels, large bookstores, and offices. A large outdoor performance hall, an office, a hotel, a musical theater, and a multiplex are located at the entrance to the underground station. A large supermarket and a high-rise residential area are built on the other side, which is connected to the former side, in a circular manner, through a main corridor and belly-type outdoor corridor. Commercial facilities are located on the lower floors of the tower building. The musical theater, multiplexes, and offices on the higher floors, as well as the hotel at the top of the building, are located in the center to promote horizontal and vertical environments. However, there is a lack of consideration for vitalization, such as large central spaces and keyhole sections.

Table 6.

Case Study, D-Cube City [17]/Source: Author.

- (5)

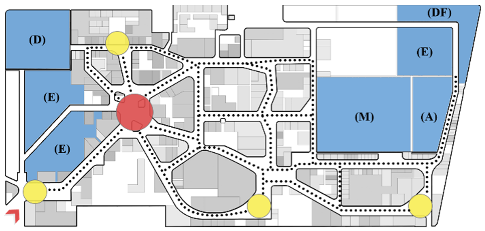

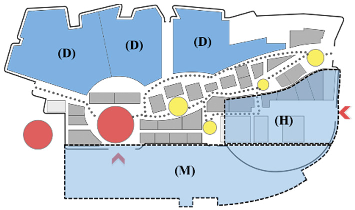

- Mecenatpolis (Completion stage/2013)

It is a residential and commercial complex that has seven underground floors and six above ground floors (Table 7). It was built on a site that was formerly a steel factory in an area that links Seoul’s city center with the outskirts. Its anchor facilities are high-rise residences, multiplexes, large supermarkets, and high-rise offices.

Table 7.

Case Study, Mecenatpolis [18]/Source: Author.

Multiplex and high-rise residential buildings were placed as anchor facilities at the farthest distance from the subway station, allowing a natural flow of traffic into the complex. The large supermarket on the lower floor and the multiplex on the upper floor promote the flow of vertical traffic. It created a natural form of circulation that resembles taking a walk by planning in the form of a street mall that has access to various entrances from outside the site—which included the installation of a pilot 18 m above the main entrance of the site—and compensating for the short distance of the site by creating an organic circulation plan that resembles the natural environment. Two nature-themed public (central) spaces were placed at the site’s central node, which is connected to each entrance. This open public space was designed to serve as a space for street performances and cultural events.

- (6)

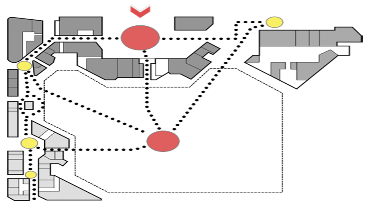

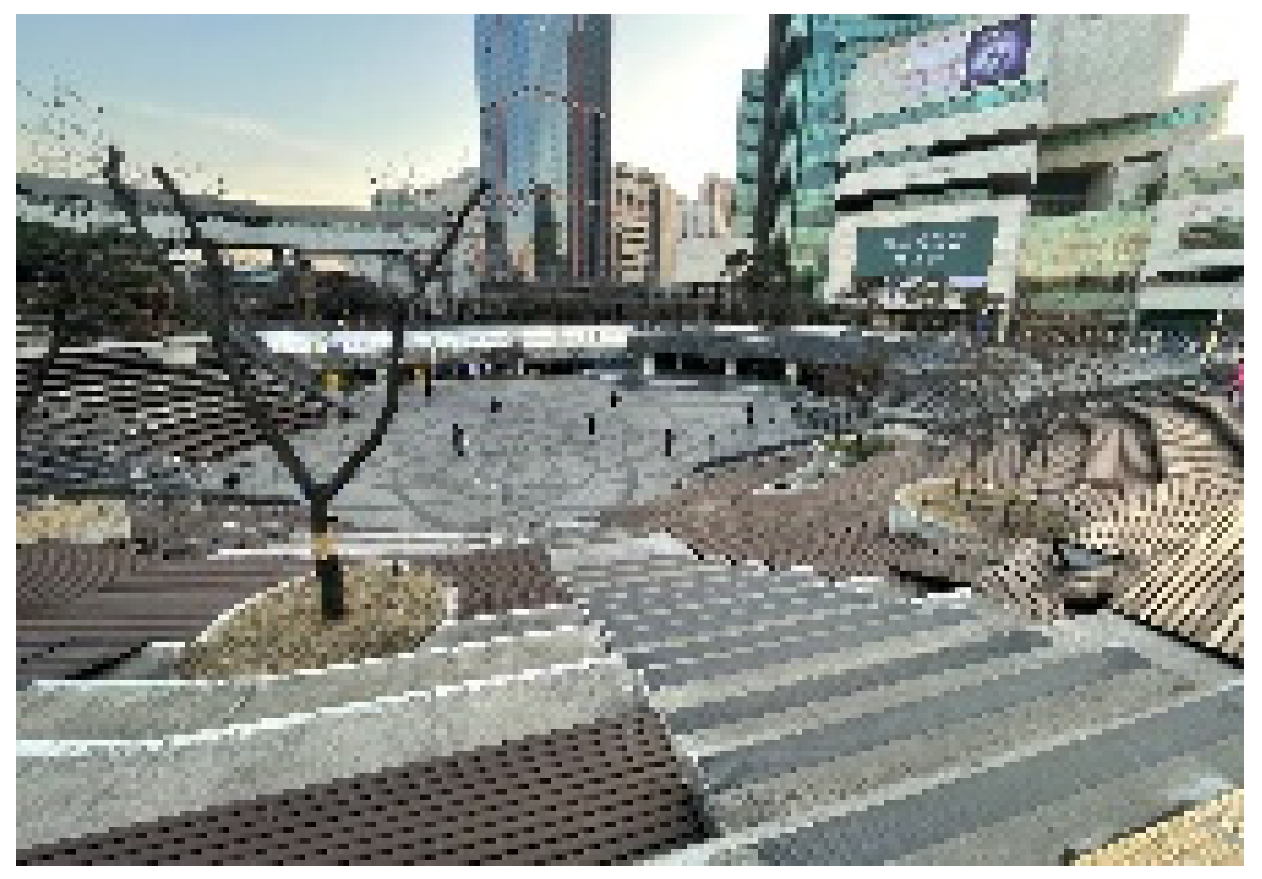

- Gwanggyo Alley Way (Completion stage/2019)

This complex is located in front of Gwanggyo Lake Park, and it is the smallest among the ones investigated—consisting of two underground floors and three above ground floors (Table 8). Apart from high-rise dwellings, there are no large anchor facilities that are common in existing multi-commercial facilities. Small-scale living and culture-related local stores are arranged in the form of an outdoor street mall that overlooks Gwanggyo Lake. The terrace-type street corridor by the lake is used as a shopping, dining-out, and event space. Its three floors are connected by a vertical circulation. A large front square by the lake is the center of the facility, and it is used for leisure activities, flea markets, and events.

Table 8.

Case Study, Gwanggyo Alley Way [19]/Source: Author.

4. Case Study Analysis

To identify the changing patterns, over time, of mixed-use commercial complexes based on the case studies, the changes in the spatial composition (types and arrangement of anchor facilities), the arrangement of circulations (corridors and linkage measures), and the central space (types and forms) of each case were examined (Table 9).

Table 9.

Summary of case analyses/Source: Author.

4.1. Spatial Composition: Types and Placement of Facilities

Early commercial complexes were built alongside national infrastructure, such as the International Convention Center (COEX Mall) and the high-speed railway station (I-Park Mall). Large anchor facilities such as department stores, shopping malls, electronic shopping malls, duty-free shops, multiplexes, and aquariums were spread out in a large underground space horizontally (COEX Mall) or a space that maximized the rental area, such as a department store-style vertically stacked space (I-Park Mall), was present. However, the complexes lacked connection between spaces due to the distance between its anchor facilities.

In the middle stage, the complexes were mainly developed alongside subway stations, as well as diverse living and cultural facilities, such as wedding halls, musical theaters, and cultural centers began to be established as their new anchor facilities alongside traditional anchor facilities such as multiplexes, department stores, large supermarkets, hotels, large bookstores, and offices. The anchor facilities were placed as key facilities on both sides of the complex, and facilities that were highly correlated with each other were placed at the top and bottom of the complex in order to promote movement (vertical and horizontal) across the entire complex through the target routes.

While the proportion of traditional large anchor facilities in later commercial complexes decreased, they were composed of small commercial facilities such as electronics, furniture, and mass merchandise stores that reflect the local commercial districts. In other cases, small-scale living, as well as food and beverage stores, were placed in the form of street malls (Gwanggyo Alley Way) without large anchor facilities—introducing new tenants and space constructions tailored to the needs and trends of local commercial districts.

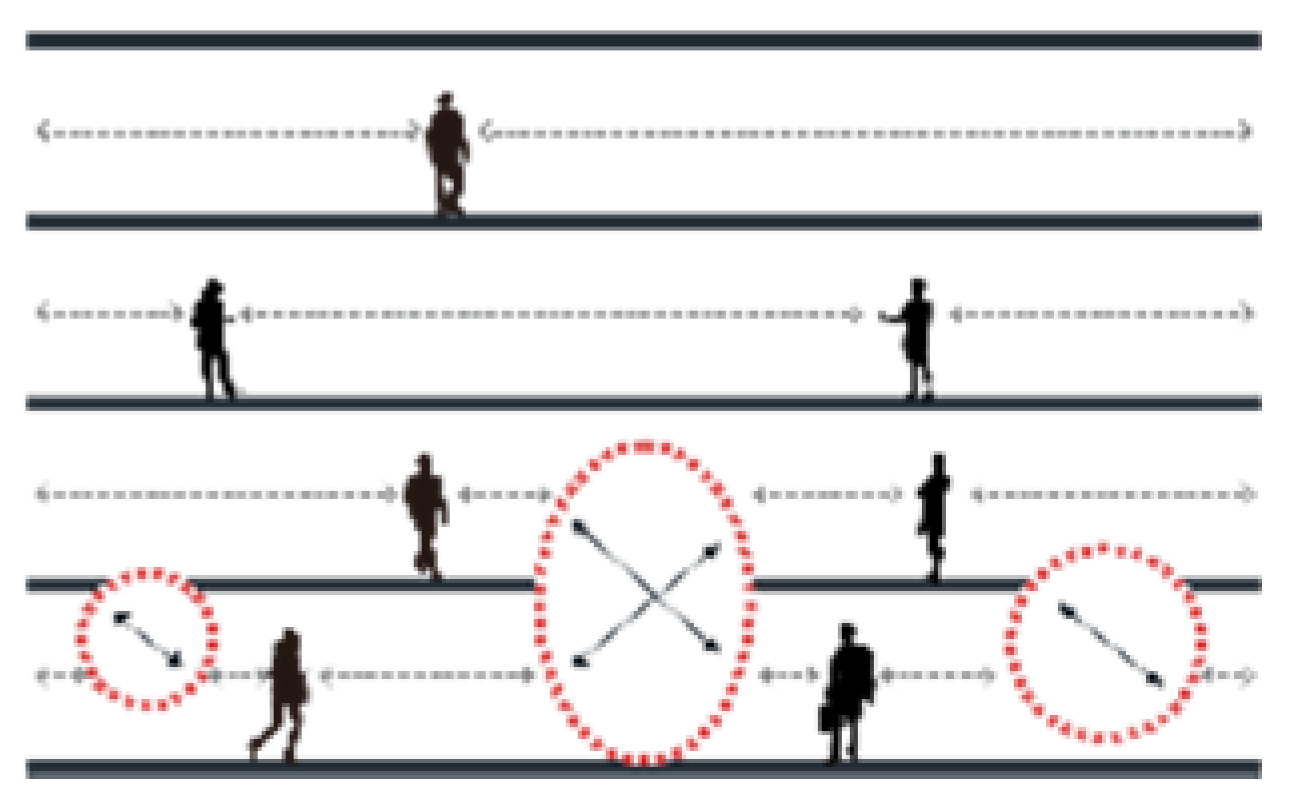

4.2. Circulation Composition: Circulation and Connection Methods

The early commercial complex connected large spaces with a number of complex maze-like corridors (COEX Mall) or had department store-style circulations to maximize the rental area, with the ratio of the exclusive area of the store being overwhelmingly higher than that of the space used as circulations (horizontal, vertical) (I-Park Mall). This caused a partial disconnect between the facilities due to their lack of connectivity, perceptibility, directionality, and continuity.

In the middle stage, the concept of circulations that took into account the revitalization of commercial districts, such as the expansion of the perceptibility, directionality, and continuity of movements, began to be reflected in the plan, such as through simplified circulations (main corridor, sub-corridor), circular corridors (main and rear corridors are circular), and keyhole sections (secures visual interpenetration between floors).

In the case of later commercial complexes, various forms and structures were attempted, including circulation plans that link each floor three-dimensionally and organically, and open street malls, such as terrace-type street malls (Gwanggyo Alley Way) or free belly-type street malls (Mecenatpolis) that resemble a nature trail.

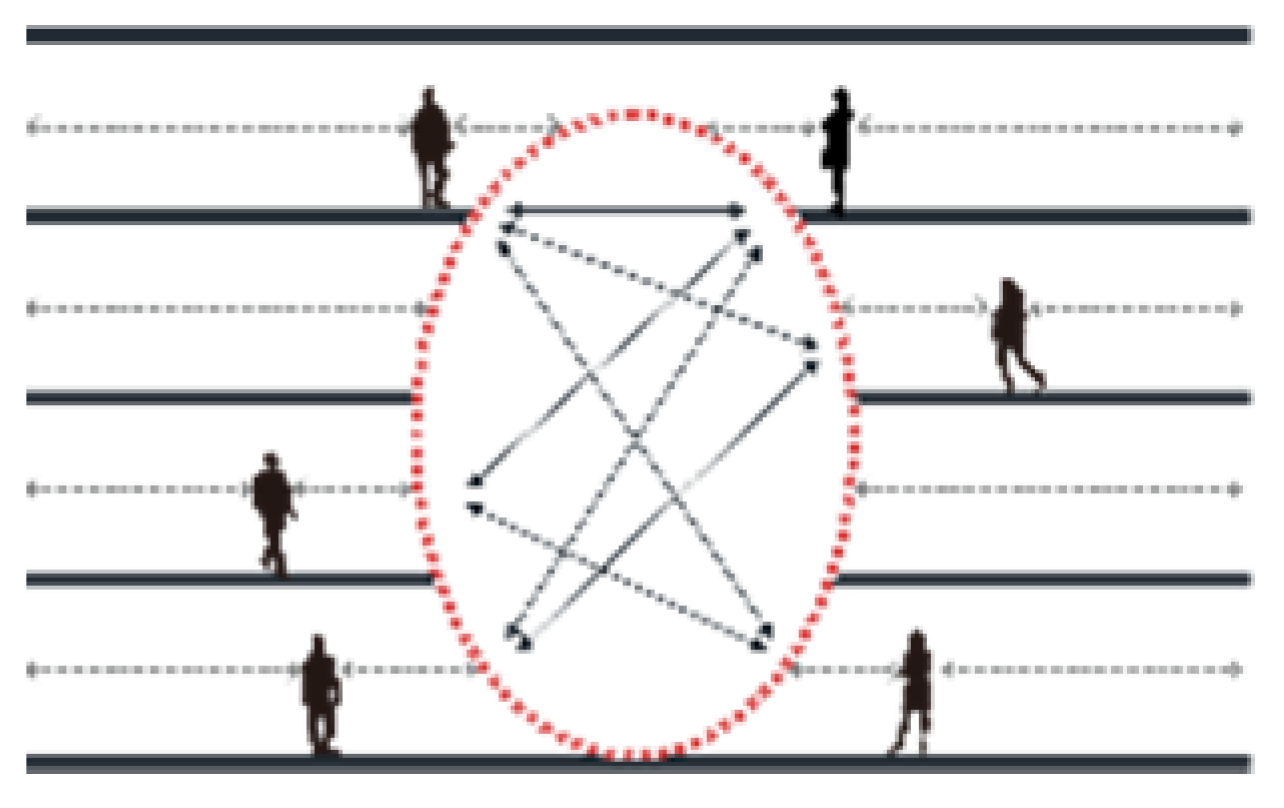

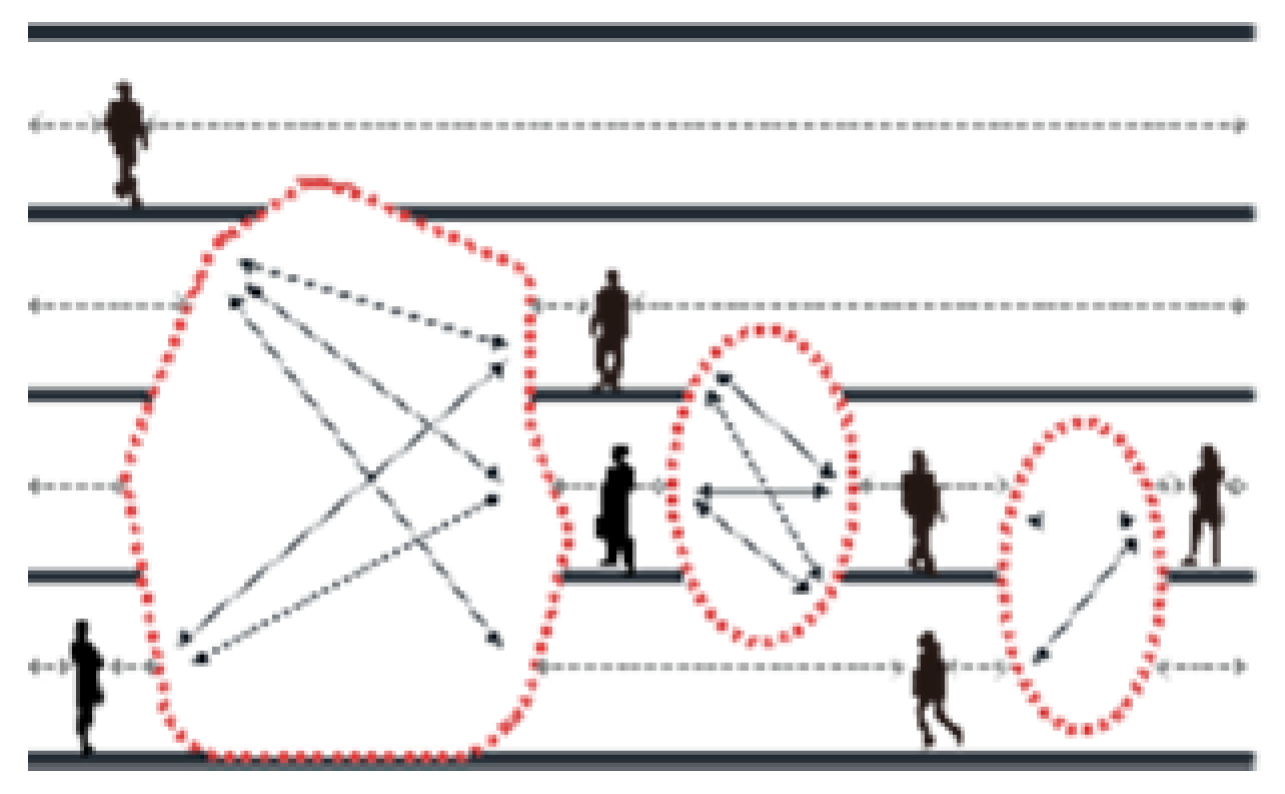

4.3. Central Space: Form and Role

In early complexes, a relatively small area was planned at the node of the circulation and used only as part of the circulation in order to maximize the rental area. However, during the middle stage, the central space was recognized as an important space to increase the customers’ desire to consume by keeping them inside for a longer time. As a result, a large center was created to facilitate circulation and for various events, as demonstrated by the large atrium-shaped central space (Time Square) [20] that penetrates the above ground floors, as well as the large outdoor central space (D-Cube City) at the end of the facility that is the entrance to a subway station. The central area was enlarged to serve as a visual and spatial center at the entrance and the nodes (horizontal, vertical).

Later, complexes broke away from a single large central space and developed a structure that is divided into several small, themed central spaces. These were designed to be a popular place where various spatial and non-daily experiences are possible [21].

4.4. Sub-Conclusion

The analysis of chronological changes in Korean commercial complexes illustrates the following.

First, the spatial composition of complexes is shifting away from commercial facilities such as department stores, rental stores, large supermarkets, and entertainment-oriented large anchor facilities such as multiplexes and aquariums. Instead, local commercial facilities such as family restaurants, specialty stores, and mass merchandisers, and small facilities that are closely related to living, such as libraries and concert halls, have taken precedence.

Second, complexes are shifting from movement circulations and arrangement based on convenience, economy, and efficiency of shopping, to consideration for non-consumption tendencies, such as the extension of visitors’ stay time and meetings, walks, and leisure activities. Circular and three-dimensional connections between each space are emphasized.

Third, as the complexes’ tenants and themes have become diversified, they are adopting small multi-centers instead of a large single center. Additionally, the utilization of central spaces for events and performances is increasing.

Fourth, concepts that stimulate visitors’ interest and non-daily experiences are being expanded, which includes the use of new themes such as natural motifs (valleys, mountains, water, forest) and the reproduction of classical streets in the space, corridors, colors, and material planning [22].

5. Discussion

In this section, I will predict the direction of change of mixed-use commercial complexes based on their patterns of change thus far.

Expanding its role as the center of the local community: the COVID-19 pandemic is contrary to the architecture and urbanism principles [23], and it has caused an increase in virtual interactions and online shopping. As a result, commercial complexes have moved away from commercial facility-oriented activities [24]. Additionally, the expansion of local, small-scale living, culture-related tenants, and programs that integrate offline strengths such as culture, entertainment, and leisure demonstrates that these areas are expected to expand their role as the center of local offline communities [25].

Linkage with local streets and expansion of street-type circulation plan: an increase in the number of living-street circulation plans that reflect the characteristics of the region is expected [26], such as the expansion of organic circulations that can naturally participate in shopping, dining, and events by actively linking with existing streets in a circular and three-dimensional manner [27].

Expansion of small multi-center spaces and theme-type external spaces: the central space will be expanded to include virtual society, links with local streets, and diverse local tenants. Additionally, the transformation into outdoor space-oriented small multi-center spaces will be bolstered, and each small space is expected to host events, exhibitions, rest, and hands-on play areas for children and parents that match the nature of the space [28].

Expanding non-consumption and non-daily planning elements: shopping has become a way of socializing [29]. Due to the increase in visits for non-consumption tendencies (meetings, walks, leisure, etc.) [30] that require various attractions and experiences other than commercial activities, it is expected that the planning of the concept, form, material, and color of these spaces will integrate a greater degree of factors that will stimulate unique experiences [31].

6. Conclusions

Given the expansion of virtual society due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the role and importance of mixed-use commercial complexes that can satisfy both leisure and cultural enjoyment will be further expanded in order for the offline market to survive.

Based on their changing patterns, this study predicted such complexes’ direction of change. First, they will expand their role as the center of the local community. Second, they will bolster their linkage with local streets and expand the street-type circulation plan. Third, small multi-center spaces and themed external spaces will increase. Fourth, non-consumption and non-daily planning elements will increase.

In this respect, many changes of mixed-use commercial complexes reflect the basic concept of pre-modernism accessible human-scale mixed-use streets, i.e., the concept typical for medieval towns and villages, and might be an exciting field for future studies.

I hope that this review of the changes in Korean mixed-use commercial complexes and their planning will be utilized in the future as basic material for projecting the changing consumption culture of the present era and designing commercial complexes that are differentiated and satisfying.

Funding

This research was funded by Wonkwang University Research Fund of 2019.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Giampino, A.; Picone, M.; Schilleci, F. The shopping mall as an emergent public space in Palermo. J. Public Space 2017, 2, 85–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kusumowidagdo, A.; Sachari, A.; Widodo, P. Visitors’ perception towards public space in shopping center in the creation sense of place. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 184, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, X. Chinese shopping center development—Today and tomorrow. IRE|BS 2018, 28, 35. [Google Scholar]

- Rahimi, A.; Khazaei, F. Designing Shopping Centers: The Position of Social Interactions. J. Hist. Cult. Art Res. 2018, 7, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mohamad, A.H.; Hassan, G.F.; Abd Elrahman, A.S. Impacts of e-commerce on planning and designing commercial activities centers: A developed approach. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2022, 13, 101634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.-F.; Shih, S.-G.; Perng, Y.-H. Sustainable Shopping Mall Rehabilitation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S. A Study on the Characteristic Ways of Extension in Commercial Multi-Complexes Based on the Utilization of Common Spaces. Ph.D. Thesis, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea, 2011; pp. 9–22. [Google Scholar]

- Shim, C. Study on Use Characteristics of Urban Entertainment Center as demand for Urban Entertainment Center. Master’s Thesis, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea, 2008; pp. 5–15. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Shim, W. A Study on the Planning Elements for the Revitalization of Mixed-Use Commercial Facilities. J. Korean Archit. Inst. 2011, 27, 29–32. [Google Scholar]

- Jeon, K.; Ahn, J.; Shim, K. The Type and Characteristics of Anchor Tenant at Shopping Center. Urban Des. 2011, 2, 151. [Google Scholar]

- Manfredo, M.; Jenner, R. The virtual public thing: De-re-territorialisations of public space through shopping in Auckland’s urban space. Interstices J. Archit. Relat. Arts 2015, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, C.; Kong, E.; Kim, Y. A Study on the Characteristics of Spatial Factors of the Circulation System at the Mixed-Use Commercial Buildings. J. Korean Archit. Inst. 2013, 29, 84–89. [Google Scholar]

- Moon, S.; Kim, Y.; Choi, Y. A Study on the Changing Architectural Properties of Void Space in Mixed-Use Commercial Complexes. J. Korean Inst. Cult. Archit. 2015, 52, 120–121. [Google Scholar]

- COEX Mall. 2000. Available online: https://www.starfield.co.kr/coexmall/about.do (accessed on 21 July 2021).

- I-Park Mall. 2004. Available online: https://www.hdc-iparkmall.com/main/index.do (accessed on 21 July 2021).

- Time Square. 2009. Available online: http://www.timessquare.co.kr/?controller=wholeConfig&action=wholeConfigList (accessed on 21 July 2021).

- D-Cube City. 2011. Available online: http://www.ehyundai.com/newPortal/DP/DP000000_V.do?branchCd=B00149000 (accessed on 21 July 2021).

- Mecenatpolis. 2013. Available online: http://www.aurum.re.kr/Bits/BuildingDoc.aspx?num=5119&tb=A&page=1#.YA476k9xeM0 (accessed on 21 July 2021).

- Gwanggyo Alley Way. 2019. Available online: https://alleyway.co.kr/store-guidance/zone-guidance (accessed on 21 July 2021).

- An, E. An Analysis of the Space Using Behavior with Space Organization in Urban Entertainment Center. J. Archit. Inst. Korea 2016, 32, 20–21. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S. Visual Interface & Surface Expressions in Commercial Space Design. Korean Inst. Inter. Des. J. 2005, 14, 3–4. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.; Jang, S.; Park, C. A Study on the Spatial Composition and Expressive Characteristics in Mass-Complex Commercial Space by Jerde Partnership’s. Korean Inst. Inter. Des. J. 2010, 19, 189–192. [Google Scholar]

- Fezi, B.A. Health engaged architecture in the context of COVID-19. J. Green Build. 2020, 15, 185–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cernikovaite, M.; Karazijiene, Ž.; Bivainiene, L.; Dambrava, V. Assessing Customer Preferences for Shopping Centers: Effects of Functional and Communication Factors. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crosbie, M.J. How might the COVID-19 change architecture and urban design? Common Edge 2020. Available online: https://pure.strath.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/104740188/How_Might_the_COVID_19_Change_Architecture_and_Urban_Design_Common_Edge.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Lee, I.; Hwang, S.W. Urban Entertainment Center (UEC) as a Redevelopment Strategy for Large-Scale Post-Industrial Sites in Seoul: Between Public Policy and Privatization of Planning. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Generalova, E.M.; Generalov, V.P.; Kuznetsova, A.A.; Bobkova, O.N. Mixed-use development in a high-rise context. E3S Web Conf. EDP Sci. 2018, 33, 01021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- He, D.; Chen, Z.; Ai, S.; Zhou, J.; Lu, L.; Yang, T. The Spatial Distribution and Influencing Factors of Urban Cultural and Entertainment Facilities in Beijing. Sustainability 2021, 13, 12252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bing, L.; Yang, X. The influence of consumer’s “new demand” on commercial building design. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 787, 012178. [Google Scholar]

- Han, H.; Sahito, N.; Nguyen, T.V.T.; Hwang, J.; Asif, M. Exploring the features of sustainable urban form and the factors that provoke shoppers towards shopping malls. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, T. Architectural Form related to Nature. J. Reg. Assoc. Archit. Inst. Korea 2019, 19, 133–134. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).