Abstract

The issue of urban sustainability is currently exceptionally up to date, and the sustainable development of cities has become an important topic on the political level. Many cities in the world are facing acute challenges concerning growing dangers to the environment and ensuring quality of life for their inhabitants. In connection with cities achieving their individual goals of sustainable development, urban sustainability indicator frameworks (USIFs) are becoming the subjects of attention. Such frameworks enable sustainability to be clearly measured and assessed. In this article, we analysed selected global and European USIFs in terms of their commonalities and differences, sustainability dimensions, thematic categories, and categorised indicators. Based on the analysis of the content of the reviewed frameworks, we compiled a list of generally recognised thematic categories within the four main dimensions of sustainable development, and we identified the key indicators of urban sustainability. Our review showed differences in the existing approaches that substantially contributed to the current inconsistencies in assessing and measuring sustainable development in cities. Our results provide an overview of this issue, e.g., to decision makers, and could concurrently serve as a generally applicable foundation for the creation of new urban sustainability indicator frameworks. We also point out the current trends and challenges in the domain of urban sustainability assessment.

1. Introduction

Cities and their development represent some of the biggest challenges of the 21st century. They have become the decisive motors of economic growth and are the centres of opportunity, prosperity, innovation, and social and cultural interaction [,,,]. Nowadays, 55% of the global population lives in urban areas, while the numbers and percentages of urban inhabitants are constantly growing. It is expected that due to urbanisation and global population growth, the urban share of the population will reach 68% in 2050 []. Cities are facing several socioeconomic and environmental challenges, such as the depletion of natural resources, reduction of biodiversity, climatic changes, air pollution, excessive noise, production and disposal of waste, land use, availability of potable water, and so on. These environmental issues in cities relate to social and economic challenges in ensuring the required quality of life and equal opportunities for all inhabitants. Ensuring quality of life not only includes providing a fundamental material existence, but also a series of other aspects—e.g., several questions such as education, public health, work, democracy, and equal economic and social conditions []. Recently, the world has been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, and the problems associated with it are much more serious in cities. The impact of COVID-19 has been the most devastating in poor and densely populated urban areas []. The issues mentioned above are seen not only within cities, but also beyond their frontiers—the sustainability of urban areas is necessary for the sustainability of regions and states, as well as that of the whole world []. In addition to the connection between cities and the environment, it is also necessary to perceive city development in relation to global issues [,,].

1.1. Sustainable Cities

Linked to the growing danger to the environment from cities and their inhabitants, the topic of urban development has become the subject of both European and global discussions. Sustainable cities and urban sustainability are defined in various manners that are characterised by criteria that concern numerous areas according to cities’ specific conditions and needs [,]. The sustainable development of cities is most often defined as the balance between three fundamental dimensions of sustainability—for example, the international organisation ICLEI (Local Governments for Sustainability) states that “sustainable cities work towards an environmentally, socially, and economically healthy and resilient habitat for existing populations, without compromising the ability of future generations to experience the same” []. However, many issues in cities require responsible institutions to deal with—and, if possible, solve—them. That is why it is necessary to include a fourth dimension—the institutional dimension. Framed in this way, sustainable urban development can be understood as a synergistic relationship among environmental, social, economic, and institutional factors in each respective city [,,]. In addition to these dimensions, we can also encounter a “cultural dimension” of sustainability within the sources in the literature [,,].

The importance of sustainable development on the local level is also shown by the formulation of a separate goal in terms of the Sustainable Development Goals for 2030—specifically, Goal 11: “Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable” []. In 2014, The Urban Thinkers Campus initiative of the World Urban Campaign was launched, bringing together various stakeholders to discuss key issues for future urban development. The main result of the process of several meetings and discussions was the document “The City We Need 2.0” []. The defined and accepted “New urban agenda” [] not only confirmed urbanisation as a key political issue at the highest level, but also pointed out the importance of indicators, frameworks, standards, and similar tools with regard to the execution of urban policy and the management of the procedures in practice. The requirement of the creation of indicators is defined in the 75th paragraph of Agenda 2030 []. Indicators became a basic and powerful tool when assessing the application of the concept of sustainable development [,]. However, it is necessary to point out that the issue of sustainable development indicators dates back to the 1990s—for example, chapter 40 of Agenda 21 [] dealt with the importance of indicators of sustainable development. Currently, the importance of urban monitoring data in supporting informed decision making is emphasised in connection with the COVID-19 pandemic [].

1.2. Urban Sustainability Indicators

In accordance with the described trends, the assessment of sustainability through indicators represents an appropriate and recommended method of managing sustainable urban development [,,]. Indicators provide a simple, measurable tool that helps to create sustainable cities that are not only environmentally friendly, but also support the long-term economic productivity, health, and quality of life of their inhabitants [,]. Indicators of sustainable development are used as a source of information in the creation of strategic documents and development programs; they help to formulate priorities and to monitor the success of the resolution of issues []. Indicators bring information to the public, to scientists, and to the authors of policies [,]. The aim is to also integrate the public into the decision-making process in the form of cooperation on the design, selection, and assessment of the indicators []. The appropriate selection of indicators thus fulfils an educational role and contributes to a better understanding of the entire concept of sustainable development [].

Recently, many studies have been published about the theoretical and methodological aspects of creating indicator frameworks and their use in the assessment of sustainability, e.g., [,,,,,,,,,,] and others. The review of available frameworks for assessing sustainability was the object of articles and studies such as those of [,,,,,,,]. Contributions to the topic of creating indicators for cities have been made by studies and methodological guidelines with practical usages—for example, [,,,,,,,,,] and others.

Indicator sets with methodological guidelines form frameworks that assess sustainability on various spatial levels []. As individual cities significantly differ in the sources and availability of data, population size, historical context of development, and the cities’ functioning, various urban sustainability indicator frameworks (USIFs) were gradually created [,,]. They were created by several international organisations, governmental agencies, non-governmental organisations, local societies, representatives of business communities, and scientists from the academic environment []. The structure of a USIF generally consists of three or four dimensions of sustainability, into which thematic categories (specified by certain goals) and indicators are organised [,,,]. While this structure increases clarity and can ensure a balanced representation of categories and indicators across all selected sustainability dimensions, it does not guarantee their interconnection []. An integrative approach and the maintenance of a balance between dimensions are essential conditions for achieving sustainable development [,,,]. In many cases, this “balance” is ambiguously defined and, therefore, remains only on a theoretical level. At present, the economic and social dimensions prevail at the expense of the environmental dimension. Likewise, the institutional dimension of sustainability lags behind [,,,].

Monitoring of sustainable urban development poses a challenge for policymakers in terms of selecting relevant thematic categories and indicators [,,,,]. The selection of categories and indicators is realised based on meeting certain criteria and requirements [,,,]. The whole process of selecting categories and indicators needs to be transparent, methodologically correct, and clearly justified [,,]. In many cases, it is difficult to eliminate the subjective nature of this process because the choice of categories and indicators is not value-neutral, but reflects the biases, failings, intentions, assumptions, and worldview of the framework’s creators [,,].

When creating a new indicator framework for a certain city, the first phase of this process is selecting relevant existing USIFs based on references and geographical or thematic similarities [,,,]. Subsequently, their content analysis takes place in terms of methodology and basic structure, within which the dimensions of sustainability, thematic categories, and the classification of indicators are examined. Part of the analysis is also the so-called “Collection of categories and indicators” and the compilation of a wider set of thematic categories with relevant indicators. At present, there probably exist hundreds of different USIFs, which also include a high number of thematic categories and indicators. This fact causes a loss in the clarity of the issue and contributes to the complexity of the process of selecting relevant categories and indicators [,,,]. Their frequent occurrence points out the importance of certain categories and indicators within selected USIFs [,]. The list of the most frequently used thematic categories and indicators makes it possible to follow the general trends and challenges in the field of the evaluation of sustainable urban development while helping to partially eliminate the subjective nature of the process of selecting the main thematic categories and key indicators in the development of the USIFs [,,,].

The large number of existing frameworks has created a space for research aiming to analyse the content of selected global and European USIFs concerning commonalities and differences, sustainability dimensions, thematic categories, and categorised indicators. The main goal of our research is to select the most relevant USIFs, analyse their content in terms of basic structure (dimensions, thematic categories, indicators), and point out the current trends and challenges in the domain of urban sustainability assessment. To achieve this goal, we address the following specific questions: (1) Which dimensions of urban sustainability form the basic frameworks of the selected USIFs? (2) Which are the most frequently used thematic categories in the selected USIFs? (3) Which are the most frequently used indicators in the selected USIFs? (4) What factors need to be considered when creating a new USIF and selecting the relevant categories and indicators? (5) How can we further improve the process of creating and using new USIFs?

Our research could help in the assessment of urban sustainability, particularly when identifying appropriate categories and indicators. The list of the most frequently used thematic categories and key indicators allows policymakers to get an up-to-date overview of the issue and serves as a starting point for creating a new indicator framework for an investigated city. We also point out the current trends and challenges in the domain of urban sustainability assessment. Our results highlight differences in the existing approaches, in the representation of the thematic categories, and in the selection of appropriate indicators. Such differences substantially contribute to the current inconsistencies in the assessment of urban sustainability.

2. Materials and Methods

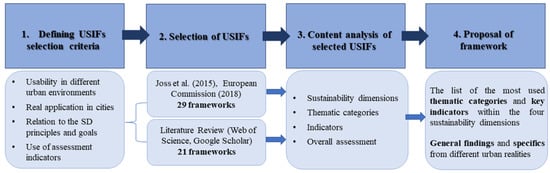

As mentioned above, the main goal of our contribution is to analyse the content of selected global and European USIFs in terms of their commonalities and differences, sustainability dimensions, thematic categories, and categorised indicators. As there probably currently exist hundreds of USIFs on various spatial levels [], it is not possible to process these issues in an exhaustive manner. That is why we formalised the assessment process into several steps, which helped us to reach the research goal (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Scheme of the research methodology.

2.1. Defining the USIFs’ Selection Criteria

Our research is focused on the analysis of the content of existing frameworks (USIFs), which we selected based on criteria that we defined. In the first phase of our research, we defined these criteria in accordance with the Bellagio Sustainability Assessment and Measurement Principles, which represent a set of eight principles for assessing and measuring sustainable development concepts [], as well as on the basis of recommendations of several authors [,,,,,,,]. In total, we defined four main criteria that must be fulfilled by an approach in order to be considered relevant for further analysis:

- Criterion 1: The usability of USIFs in various urban environments highlights that they should be applicable—with minor modifications—in different cities. This means that a framework is not formulated exclusively for the conditions of one specific city.

- Criterion 2: The real application of USIFs in cities means that the individual frameworks are actually used in the cities, i.e., they are not only theoretical concepts without practical use.

- Criterion 3: The relationship of USIFs to the principles and goals of sustainable development means that they represent all of the main aspects of sustainability (the social, economic, environmental, and institutional aspects).

- Criterion 4: The usability of the indicators in USIFs—i.e., the existence of indicators through which sustainability in cities is monitored. Frameworks that do not monitor cities with indicators were considered irrelevant for the purposes of this paper.

2.2. Selection of Relevant USIFs

In the second phase of our research, we selected appropriate USIFs by using two approaches. The main sources for the selection of USIFs were the publications of the European Commission [] and Joss et al. [], who provided a review of the most commonly used USIFs around the world. From these works, we selected a total of 29 frameworks that fulfilled the defined criteria.

The selection process was supplemented by a review of published studies that were registered in the Web of Science and Google Scholar databases. The review was performed for the period 2013–2021 because the publications [,] contained a recent review of frameworks up until 2013. As keywords for the search for the studies, the following words were used: “urban sustainability frameworks” and “sustainable cities indicators”. Because this research topic is very advanced in German-speaking countries, we also used the following German keywords: “Indikatoren der nachhaltigen Stadtentwicklung” and “Nachhaltigkeitsbericht der Stadt”. In total, we identified more than 200 appropriate studies, which included, in particular, articles, frameworks, and guidelines concerning the assessment of urban sustainability. Then, we assessed the individual studies via the criteria specified in point 1—their fulfilment led to the incorporation of the studies into the next phase of our research.

By using this methodology, we identified 50 relevant USIFs in total (Appendix A). This review includes studies and indicator frameworks from around the world that assess urban sustainability on various spatial levels—global, regional (especially Europe), national, or local (individual initiatives of cities). The analysis of diverse contexts around the world provides valuable information that is regionally specific []. For this reason, in the analysis, we will highlight not only the general findings, but also the specifics from different urban realities. For each framework, we identified its name, the organisation founding and supporting it, the geographical localisation of its use, its date of creation or initialisation, and links for further detailed information.

2.3. Content Analysis of the Selected USIFs

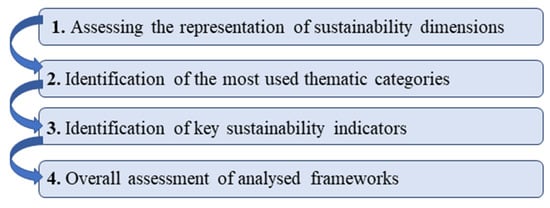

In the 3rd phase of our research, we examined the selected USIFs. Via a content analysis, we entered the acquired data concerning the dimensions, thematic categories, and indicators into tables. During the study, we focused on the assessment of four main areas (Figure 2) that all contributed to our research goal of creating a list of the most commonly used thematic categories and indicators. We also highlight the current trends and challenges in the domain of urban sustainability assessment.

Figure 2.

Content analysis of the 50 selected USIFs.

First, we focused on the assessment of the frameworks in terms of their representation of the dimensions of sustainability. The USIFs were classified based on whether the categories and indicators were explicitly arranged within 4 dimensions (environmental, economic, social, institutional), 3 dimensions (environmental, economic, social), or were not explicitly organised in sustainability dimensions. Then, we assessed the number of incidences of the dimensions that were processed based on their content coverage by appropriate categories and indicators. The coverage of a selected dimension of sustainability was considered fulfilled if it was represented by one category or indicator.

The second analysis was focused on the identification of the thematic categories used within the selected frameworks—they were arranged according to the four dimensions of sustainability. The individual categories were defined according to the representation of the specific indicators due to the differences in terminology and names of categories in the individual works. That is why we interconnected some categories and specified alternative possibilities for their names. We will highlight these differences via examples within the results of this study and in the discussion. Categories that were found in at least two frameworks were specially marked.

The third analysis was focused on the identification of the most frequently and typically used indicators, which represented the most frequent categories of the selected frameworks. We considered categories such as those that were represented in at least one-third of the USIFs (17 and more). For the selected categories, indicators represented in at least five frameworks were selected, and differences concerning the measurement units of the indicators were allowed.

3. Results

3.1. Urban Sustainability Assessment

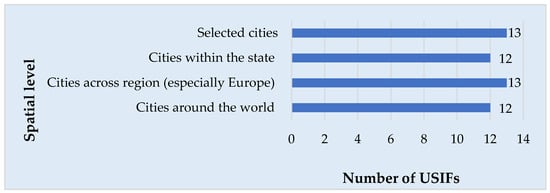

The set of 50 selected USIFs consists of frameworks that are focused on the assessment of the concept of urban sustainability on various spatial levels—global (cities around the world), regional (especially Europe), national, or local (individual initiatives of cities). Their representation in the selected set is almost equivalent (Figure 3). As for the time aspect, most of the selected frameworks were created after the year 2000; just three of them were compiled in the 1990s, while 27 frameworks were developed after 2010. The main initiator of urban sustainability assessment at the international level was the UN (Appendix A). In measuring progress towards sustainable urban development through global indicators, the UN intends to provide a single assessment report for all stakeholders from different countries, except indicators that will not be relevant for various reasons. The global indicators should subsequently form the core of the regional and national monitoring systems of cities, which include other indicators according to the needs and specifications of the cities []. The USIFs on the global level are focused on the assessment of cities with populations of over 100,000. Quantitative and qualitative indicators are used to monitor cities, and they differ slightly due to differences in data availability and unique challenges faced by each region of the world. There is a significant difference in sustainable urban development priorities between developed and developing countries, so the relevance of themes and indicators varies from city to city. International indicator systems offer a basic framework of indicators that are measurable in each city (as much as possible). Their main purpose is to compare (benchmark) cities based on the evaluated indicators.

Figure 3.

Spatial aspect of the selected USIFs.

At the same time, various initiatives have arisen to deal with the creation and assessment of USIFs in the regional and national contexts. From a long-term perspective, urban sustainability is one of the main goals of EU policies; several studies and EU organs deal with its assessment. The European USIFs are similar in nature to the global indicator systems and are mainly used to monitor capitals and major cities in Europe []. The issue of urban sustainability is also one of the main priorities of several states, who have developed their own national USIFs to monitor this goal. Similarly, there are initiatives on the local level (cities) where specific custom indicator frameworks are created. In both cases, specific characteristics of the countries and cities are taken into consideration.

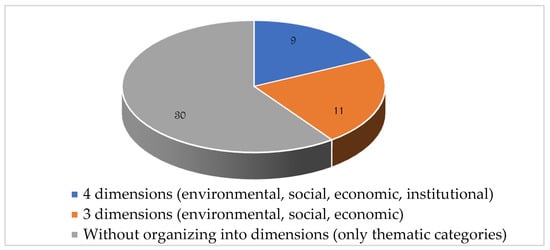

3.2. Dimensions of Urban Sustainability Assessment

The first analysis of the selected frameworks was focused on their assessment according to the representation of the dimensions (or pillars) of sustainability (Figure 4). Most of the frameworks (30) arranged the indicators within specific thematic categories without a direct relationship to the main dimensions of sustainability. Only nine frameworks were organised within all four dimensions, and 11 frameworks were organised within three sustainability dimensions. In addition to these dimensions of sustainability, we also identified the “spatial dimension” and “cultural dimension”, which were part of the Reference Framework for Sustainable Cities (RFSC) and Toolkit for Cities. These were used in the frameworks only once—in most cases, their content was specified through different thematic categories within “traditional” sustainability dimensions (e.g., for the spatial dimension: mobility and transport, land use, housing, green space, and social infrastructure). The cultural dimension was understood mostly as a specific thematic category within the social dimension.

Figure 4.

Organisation of the selected frameworks within the dimensions of sustainability.

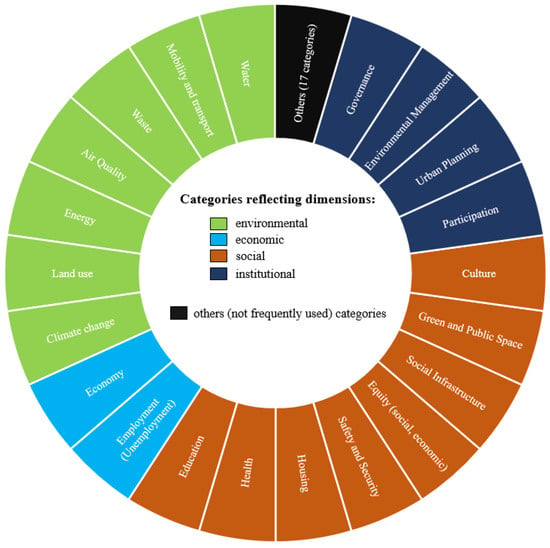

The other frameworks that were not explicitly organised into sustainability dimensions consisted of different thematic categories. However, they also reflected different sustainability dimensions (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

The most frequently used thematic categories of frameworks that did not follow the four sustainability dimensions.

Subsequently, we also assessed the number of incidences of single dimensions based not only on the direct organisation of frameworks according to the dimensions of sustainability, but also on the content focus of relevant categories and indicators (Table 1). The environmental dimension of sustainability was assessed within all of the selected frameworks. The second largest representation was reached by the social dimension (45), followed by the economic dimension (41). The least assessed was the institutional dimension of sustainability (24).

Table 1.

Content coverage of the dimensions of sustainability within the selected frameworks.

3.3. Thematic Categories of Urban Sustainability Assessment

The following analysis was focused on the identification of the most frequently used thematic categories within the selected USIFs (Table 2). Based on the defined criteria, we identified 38 categories. As regards their incorporation into the main dimensions, the highest number of categories was recorded for the environmental (14) and social (13) dimensions. The main problem in identifying individual categories is the inconsistency in the terminology in some categories, which often differ despite evaluating the same territory. Similarities or duplications between such categories can then only be identified based on an analysis of the relevant indicators. As part of our research, we compiled a list of categories with primary and secondary titles, which may contribute to terminological standardisation.

Table 2.

The most frequently used thematic categories within the selected frameworks.

3.4. Indicators of Urban Sustainability Assessment

In another step of the analysis, we identified the most frequently used indicators that represented the main thematic categories of the selected frameworks (Table 3). For almost every selected category, we identified two key indicators (except for the categories of climate change, education, culture, urban planning, and governance (one indicator) and mobility and transport (three indicators)).

Table 3.

The most popular indicators of sustainability within the selected thematic categories.

The environmental dimension of sustainability consists of seven main thematic categories: water, mobility and transport, waste, air quality, energy, land use, and climate change. The most frequent indicators in the “water” category were related to the assessment of the consumption of water, purification quality, and water sanitation. The number of indicators was monitored within the “mobility and transport” category —they were focused especially on monitoring the volume of daily transport, ownership of personal automobiles, modal split, traffic flow, ecological transport, and affordability of public transport. Indicators within the “waste” category were particularly focused on the production, separation, and recycling of waste. The most frequent assessment indicators of the “air quality” category were the annual mean concentration of pollutants (NO2, PM10, and PM2.5) and the number of times that the limit of pollutants (NO2, PM10, and O3) was exceeded. Within the “energy” category, most of the indicators were related to its consumption and the use of renewable resources. In the case of the “land use” category, the representation of the individual categories of using the territory of the city was assessed. Within the “climate change” category, indicators assessing the amounts of CO2 emissions in cities were monitored.

The economic dimension of sustainability consists of two main thematic categories: economy and employment. Within the “economy” category, the economic power of a city was assessed in relation to the size of the city’s product. The “employment” category was dominated by indicators monitoring local employment or unemployment in a city. Its classification was, however, not clear enough because these indicators appeared within both categories of the economic dimension of sustainability.

The social dimension of sustainability consists of eight main thematic categories: education, health, housing, safety and security, equity (social, economic), social infrastructure, green space, and culture. In the “education” category, there are significant differences in the content of the monitoring of the topic in the global and European indicator frameworks. Global frameworks deal especially with indicators that are relevant for cities in developing countries (literacy rate, school enrolment), while indicator frameworks within Europe or in developed countries focus more on the quality of education. The indicators of the “health” category specifically monitor the quality and availability of medical services. In the “housing” category, sufficient space and the economic costs of living are monitored. The “safety and security” category is mostly monitored via indicators that assess the number of the crimes and traffic accidents in the city. The last indicator mentioned is also frequently found in the “mobility and transport” and even “health” categories. Within the “equity (social or economic)” category, the distribution of income and equal opportunities for all groups of inhabitants are monitored. In the “social infrastructure” category, there are several indicators that monitor the saturation of households in terms of basic services and their accessibility. The “green space” category is mostly assessed via indicators that monitor green areas and their accessibility for inhabitants of a city. In the case of the “culture” category, public expenditure on culture is monitored.

The institutional dimension of sustainability consists of four main thematic categories: participation, urban planning, environmental management, and governance. Within the “participation” category, voter turnout and the number of civil associations in the city are the most commonly assessed. The “urban planning” and “environmental management” categories are monitored by similar indicators that most commonly assess the existence of documents for inciting sustainable and strategic urban development and the adoption of an environmental management plan. In the last category, “governance”, the management of public funds is specifically evaluated, most often through the indicator of total debt per capita of a municipality.

4. Discussion

4.1. Urban Sustainability Assessment

Indicator frameworks are useful in the process of planning and managing urban development [,]. The implementation and use of such frameworks can help ensure the reliable measurement of cities’ progress towards long-term sustainable development. In addition, they support informed decision making and contribute to effective communication between decision makers and the public [,,]. Using indicator frameworks for policy planning provides new opportunities for transparency and efficiency, but certainly also generates new risks []. The whole process must be viewed not only from the scientific side, but also in its capacity as a political process []. Indicator frameworks of the type described here can be used in addition to the monitoring of local politics—the participants involved in the municipalities are very aware of this. Hence, there will be a tendency for parties with governmental responsibility to focus on indicators that show a positive outcome, while opposition parties pounce on any negative outcomes. A political debate about the “value” of the different thematic categories and goals represented by the indicators can arise, which is not always to the advantage of the better dissemination of the overall goal of sustainability. This can be remedied by an intensive examination of the different indicator frameworks and their relationships to the overall goal. It is also helpful if the goals and indicators are chosen step by step in a participatory process that only focuses on the usefulness of the indicator framework and not on the empirical results of a specific region [,,].

The interest in the assessment of sustainability on a local level is significant, as confirmed by the increasing growth of the number of USIFs, which has been especially clearly visible over the last decade [,]. On the other hand, the enormous number of approaches contributes to the methodological variability of this issue. Differences may especially be found in the representation of the dimensions of sustainability, as well as the selection of thematic categories and representative indicators. Thus, cities and their policymakers face the challenge of selecting relevant indicator frameworks that best correspond to the needs and goals of their assessments [,]. The selection and the content analysis of indicator frameworks usually form the first phase in assessing the sustainability of cities [,,]. The aim of such an analysis is to gain current knowledge about the methodologies and basic structures of the frameworks (sustainability dimensions, thematic categories, indicators) that policymakers can use as a starting point in compiling indicator frameworks for their cities. In the analysis of frameworks from diverse contexts around the world, it is necessary to consider their diversity and highlight the common characteristics and the specifics in different urban realities [,].

4.2. Representation of the Dimensions of Sustainability

Several authors have pointed out that in the assessment of sustainability, the equal representation of basic dimensions is important [,,,]. Nowadays, there is a model of balance among three or four dimensions of sustainability;, in addition to the environmental, economic, and social dimensions, a fourth dimension has been established: the institutional dimension. However, there are also other opinions regarding the importance of dimensions that depend on individual perspectives and goals. In many cases, the high standards of integrative and holistic approaches to the concept of sustainable development cannot be fulfilled [,]. In the assessment process, no dimension of sustainability should be ignored [,]. However, the keeping of balance and the interconnection between the dimensions are important conditions of reaching sustainable development [,,]. In our analysis, we found that most (30) of the selected USIFs were not explicitly organised as per the dimensions of sustainability (Figure 4), but directly according to individual thematic categories (Figure 5). However, this phenomenon does not necessarily lower the relevance of these frameworks in the context of sustainability; this would only be the case if the individual dimensions were represented by thematic categories and indicators. The content analysis showed that the majority of USIFs covered the three traditional dimensions of sustainability (Table 1), thereby indicating an insufficient representation of the institutional dimension of sustainability and confirming the previous findings of the authors of [,,]. Several challenges and issues (environmental, economic, social) require common procedures and suitable institutional conditions that will then enable the execution of specific solutions [,,]. In our approach, we pointed out the suitability of the balanced representation of the content of categories and indicators within all four dimensions of sustainability, thus creating a complex urban sustainability assessment system.

4.3. Identification of the Main Thematic Categories and Key Indicators

The results of our further analysis identified the most frequently used thematic categories of USIFs (Table 2). They are related to the results of previous research in this domain [,,,,]. Our results indicate the prioritised topics and confirm the importance of monitoring the selected categories in the assessment of urban sustainability. The main issue of identification is the difference between the individual terminologies and the names of some categories, which often differ even though they assess the same domain [,]. It is then possible to identify the relationships or duplicities of such categories based only on the analysis of the individual indicators. For this reason, many authors [,,] suggest standardising the terminology of sustainability assessment, which would help to better clarify this issue. Within our research, we compiled a list of categories with their main and secondary names, which could contribute to a terminological standardisation (Table 2).

In another part of the research, we analysed the most frequent (with a representation of at least 1/3) thematic categories of the selected frameworks from the point of view of the representative indicators. Despite certain differences, it is possible to identify so-called headline or key indicators—they are indicated in almost every framework, or their multiple and frequent presences confirm their importance. This is why, as part of our research, we tried to compile a list of the key indicators (Table 3) that should never be absent from any USIF.

The USIFs also differ in terms of their thematic categories with the arrangement of the indicators; for example, the indicator “share of population connected to a public sewerage system and wastewater treatment system” was included in the “water” category, but also in the “housing” category. The indicator entitled “number of traffic accidents per year per 1000 inhabitants” was included in the “safety and security” category, but also in the “mobility and transport” category. Moreover, in some cases, the indicators were directly assigned to a dimension without being arranged in a thematic category.

Other differences among the indicators’ representation were seen between the frameworks of developing states and to those of states considered to be developed. For this reason, it is important to take the relevance of the geographical space into consideration in the selection. There are significant differences in the priorities of developed and developing countries, and the relevance of categories and indicators in cities differs. In developed countries, environmental categories and indicators are overrepresented, while in developing countries, there are mostly social and economic categories and indicators [,,,]. Based on historically uneven economic development, developing countries prioritise the economic and social dimensions of development (at the expense of environmental quality). In contrast, developed countries focus mainly on the protection and quality of the environment [].

Despite the possible definitions of the most commonly used thematic categories and the key indicators of urban sustainability, the selection of categories and indicators for the framework depends mainly on the assessment of other criteria, such as the relevance of categories and indicators for a city’s goals, the availability of data, etc. It is important to take into consideration the specific needs of cities [,,]. In addition, the issue of subjectivity remains relevant, and this has been considered by several authors [,,,].

4.4. Limitations of the Study

In our research, we analysed 50 global and European USIFs that are available in English and German. These frameworks were selected based on predetermined criteria that allowed the creation of a representative and flexible list for a content analysis. At present, there are probably hundreds of different USIFs that include a high number of slightly different thematic categories and indicators (and are available in different languages) [,]. For this reason, the results of our analysis cannot be considered exhaustive—however, we consider them to be sufficiently representative.

The use of the structure of a USIF with four dimensions of sustainability and the most commonly used thematic categories and key indicators increase the clarity and could ensure a balanced representation of categories and indicators across all selected sustainability dimensions. On the other hand, they do not guarantee a mutual integration of all dimensions, which is essential for achieving sustainable development [,,,].

The list of the most frequently used thematic categories and key indicators allows policymakers to get an up-to-date overview of these issues and could serve as a starting point for the creation of a new indicator framework for a given city. However, not all categories and indicators are relevant for each city; therefore, it is always necessary to take the specific conditions and goals of the city into consideration [,].

Our research is not an example of a USIF assessment in a specific city, but focuses on the analysis of the content of various frameworks. The whole process is rather “idealised” and is based on one dominant criterion—the frequency of use of the dimensions, categories, and indicators within the selected frameworks. We tried to point out the importance of certain categories and indicators within selected USIFs. However, the selection of categories and indicators for a specific framework in a given city also depends on the assessment of other criteria, such as the relevance of categories and indicators for the city’s goals, the availability of data, etc. [,,,]. Therefore, a balanced and comprehensive approach often cannot be or is not used in real cases.

4.5. Insights into Further Research

The monitoring of urban sustainability poses a challenge for policymakers in terms of the selection of relevant thematic categories and indicators. This process will require meeting certain criteria based on both scientific soundness and practical feasibility. Therefore, further research will be needed in order to propose a comprehensive procedure for creating an urban sustainability indicator framework that is transparent, methodologically correct, clearly justified, and generally usable. Such a procedure should be based on the analysis of different frameworks, general guidelines, and recommendations of relevant authors dealing with the issue of urban sustainability assessment.

In particular, the following methodological issues should be resolved: (1) the criteria for the selection of thematic categories and indicators, (2) feasible/optimal numbers of indicators within thematic categories, (3) the participation of stakeholders in the creation of frameworks (selection of thematic categories, goals, and indicators), (4) the structure and content of the indicators’ methodological sheets, and (5) the methodology for the final evaluation and interpretation of the indicators.

5. Conclusions

The assessment of sustainability on the local level via USIFs represents an up-to-date and important process that contributes to the attainment of the defined goals of sustainable development. Based on the assessment of the indicators, we can transfer the discussion from abstract formulations to specific goals that fulfil the suppositions for achieving sustainable development on various levels. As of now, hundreds of USIFs have come into existence, but they often do not have sufficient support for their application in practice. If we want to build sustainable cities, it is important to implement monitoring of the decision-making process so that responsible parties and policy authors can design the required changes.

For our research, we analysed 50 USIFs that we selected based on predetermined criteria. We presented the results as a summary of the status of the issues of urban sustainability assessment. Based on the analysis of the content of the selected frameworks, we compiled a list of generally recognised thematic categories within the four sustainability dimensions and identified key indicators of urban sustainability. The presented framework can be used in the process of evaluating sustainable urban development and especially in identifying the main categories and key indicators. The list of the most commonly used thematic categories and key indicators can allow policymakers to formulate an up-to-date overview of an issue and can serve as a starting point for the creation of indicator frameworks for their cities. This paper provides guidance for policymakers on how to proceed during the initial phase of the urban sustainability assessment process and “not get lost” in the dozens of different USIFs, which provide a high number of thematic categories and indicators. However, we have to point out that even if there is some possibility of a standardisation of procedures for determining the main categories and indicators of sustainability, it is always necessary to take the specific conditions and goals of a city into consideration.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation and methodology: D.M., P.M., H.D. and B.H.; data preparation: D.M. and P.M.; data analysis: D.M. and P.M.; data curation: D.M., P.M., H.D. and B.H.; writing: D.M., P.M., H.D. and B.H.; visualisation: D.M. and P.M.; supervision: D.M. and P.M.; correspondence: P.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Scientific Grant Agency of the Ministry of Education of the Slovak Republic (VEGA Grant No. 1/0706/20 “Sustainable urban development in the 21st century—Assessment of key factors, planning approaches, and environmental relationships”).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data are available in the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. The List of Selected Urban Sustainability Indicator Frameworks

Table A1.

The list of the analysed urban sustainability indicator frameworks.

Table A1.

The list of the analysed urban sustainability indicator frameworks.

| Framework | Organisation | Locations | Year | Read More | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | Global Urban Indicators | UN-Habitat | Cities around the world | 2006 | https://unhabitat.org (accessed on 1 March 2021) |

| 02 | City Prosperity Index | City Prosperity Initiative (UN-Habitat) | Cities around the world | 2012 | https://cpi.unhabitat.org (accessed on 1 March 2021) |

| 03 | Global indicator framework for the SDGs | UNSD (IAEG-SDGs) | Cities around the world | 2017 | https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/indicators (accessed on 1 March 2021) |

| 04 | Urban environmental indicators (Green Growth in Cities) | Green Cities Programme OECD | Cities around the world | 2013 | https://www.oecd.org (accessed on 1 March 2021) |

| 05 | Global City Indicators | Global City Indicators Facility (University of Toronto) | Cities around the world | 2008 | https://www.daniels.utoronto.ca (accessed on 2 March 2021) |

| 06 | Green City Index | Siemens | Cities around the world | 2009 | https://apps.espon.eu (accessed on 2 March 2021) |

| 07 | Toolkit for Cities | Sustainable Cities International | Cities around the world | 2012 | https://www.mayorsinnovation.org (accessed on 2 March 2021) |

| 08 | One Planet Living (One Planet Cities) | Bioregional | Cities around the world | 2017 | https://www.bioregional.com (accessed on 2 March 2021) |

| 09 | International Ecocity Framework and Standards | Ecocity Builders | Cities around the world | 2012 | https://ecocitystandards.org (accessed on 3 March 2021) |

| 10 | Urban Sustainability Framework | Global Platform for Sustainable Cities (World Bank) | Cities around the world | 2016 | https://www.thegpsc.org (accessed on 3 March 2021) |

| 11 | Indicators for City Services and Quality of Life (ISO 37120) | The World Council on City Data | Cities around the world | 2014 | https://www.dataforcities.org (accessed on 3 March 2021) |

| 12 | Sustainable Cities Index | Arcadis | Cities around the world | 2018 | https://www.arcadis.com (accessed on 3 March 2021) |

| 13 | Urban Sustainability Indicators | Eurofound | Cities in Europe | 1998 | https://www.eurofound.europa.eu (accessed on 3 March 2021) |

| 14 | European Common Indicators | European Commission | Cities in Europe | 2002 | http://www.gdrc.org (accessed on 4 March 2021) |

| 15 | List of indicators from the project TISSUE | European Commission | Cities in Europe | 2005 | https://cordis.europa.eu (accessed on 4 March 2021) |

| 16 | List of indicators from the project STATUS | European Commission | Cities in Europe | 2006 | https://www.researchgate.net (accessed on 4 March 2021) |

| 17 | Urban Ecosystem Europe | ICLEI, Ambiente Italia | Cities in Europe | 2007 | http://www.dexia.com (accessed on 4 March 2021) |

| 18 | The European Green Capital Award | European Commission | Cities in Europe | 2010 | https://ec.europa.eu (accessed on 4 March 2021) |

| 19 | European Green Leaf | European Commission | Cities in Europe | 2015 | https://ec.europa.eu (accessed on 4 March 2021) |

| 20 | Urban Metabolism Framework | European Environment Agency | Cities in Europe | 2011 | http://ideas.climatecon.tu-berlin.de (accessed on 8 March 2021) |

| 21 | Urban Audit Cities Statistics | Eurostat | Cities in Europe | 1999 | https://ec.europa.eu (accessed on 8 March 2021) |

| 22 | BRIDGE Decision Support System (DSS) | 14 Organisations from 11 EU countries | Cities in Europe | 2011 | https://www.worldscientific.com (accessed on 8 March 2021) |

| 23 | Indicators to assess cities’ livability | Faculty of Engineering, The University of Porto | Cities in Europe | 2015 | https://www.researchgate.net (accessed on 8 March 2021) |

| 24 | Reference Framework for Sustainable Cities—RFSC | European Commission | Cities in Europe | 2008 | http://rfsc.eu (accessed on 8 March 2021) |

| 25 | Indicators of Emerging and Sustainable Cities Initiative | Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) | Cities in Latin American and Caribbean | 2010 | https://www.iadb.org (accessed on 8 March 2021) |

| 26 | China Urban Sustainability Index | Urban China Initiative | Cities in China | 2010 | http://www.urbanchinainitiative.org (accessed on 8 March 2021) |

| 27 | ACF Sustainable Cities Index | Australian Conservation Foundation (ACF) | Cities in Australia | 2010 | https://www.acf.org.au (accessed on 8 March 2021) |

| 28 | STAR Community Rating System | STAR Communities, U.S. Green Building Council | Cities in the United States of America | 2008 | http://www.starcommunities.org (accessed on 9 March 2021) |

| 29 | Toolkit for Cities | Government of Canada, Sustainable Cities International | Cities in Canada | 2011 | https://www.scribd.com (accessed on 9 March 2021) |

| 30 | Urban Sustainability Indicators | Sustainable Cities Program | Cities in Brazil | 2012 | https://www.cidadessustentaveis.org (accessed on 9 March 2021) |

| 31 | Cercle Indicateurs | Federal Office for Spatial Development (ARE), Federal Statistical Office | Cities in Switzerland | 2003 | https://www.bfs.admin.ch (accessed on 9 March 2021) |

| 32 | The methodology for evaluating sustainable development of small towns | Healthy Cities, Towns, and Regions of the Czech Republic, Charles University | Cities in the Czech Republic | 2017 | https://www.healthycities.cz (accessed on 9 March 2021) |

| 33 | CASBEE for Cities | Japan Sustainable Building Consortium (JSBC) | Cities in Japan | 2011 | http://www.ibec.or.jp (accessed on 9 March 2021) |

| 34 | Monitor Nachhaltige Kommune: Bericht 2016—Teil 1 | Bertelsmann Stiftung, German Institute of Urban Affairs | Cities in Germany | 2016 | https://difu.de (accessed on 9 March 2021) |

| 35 | SDG-Indikatoren für Kommunen | Bertelsmann Stiftung, German Institute of Urban Affairs, BBSR, DLT, DST, DStGB, SKEW | Cities in Germany | 2018 | https://www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de (accessed on 9 March 2021) |

| 36 | Sustainability Evaluation Metric for Policy Recommendations | Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) | Cities in Ireland | 2016 | http://www.epa.ie (accessed on 9 March 2021) |

| 37 | Set of sustainable development indicators for Slovak cities | Regional Environmental Centre Slovakia | Cities in the Slovak Republic | 2005 | https://www.researchgate.net (accessed on 10 March 2021) |

| 38 | Leitfaden N!-Berichte für Kommunen | FEST—Institut für interdisziplinäre Forschung | Cities in Baden-Württemberg (Germany) | 2015 | https://www.fest-heidelberg.de (accessed on 10 March 2021) |

| 39 | LISL—Lokales Indikatorensystem für dauerhafte Lebensqualität | Upper Austria | Cities in Upper Austria | 2004 | https://www.land-oberoesterreich.gv.at (accessed on 10 March 2021) |

| 40 | Sustainability monitoring in the City of Zurich | City of Zurich Urban Development, Department of the Mayor | Zurich | 2004 | https://www.stadt-zuerich.ch (accessed on 10 March 2021) |

| 41 | Nachhaltigkeitsbericht für Ludwigshafen am Rhein | City of Ludwigshafen am Rhein | Ludwigshafen am Rhein | 2017 | https://ludwigshafen.de (accessed on 11 March 2021) |

| 42 | Nachhaltigkeitsbericht der Stadt Mannheim | Mannheim, FEST | Mannheim | 2016 | https://www.mannheim.de(accessed on 11 March 2021) |

| 43 | Hamburger Entwicklungs-INdikatoren Zukunftsfähigkeit | Zukunftsrat Hamburg | Hamburg | 2003 | https://www.zukunftsrat.de (accessed on 11 March 2021) |

| 44 | Indikatoren für eine nachhaltige Stadtentwicklung | Office citizen participation and Local Agenda 21, Gießen | Gießen | 2004 | https://www.giessen.de (accessed on 11 March 2021) |

| 45 | Nachhaltigkeitsindikatoren Linzer Agenda 21 | City of Linz | Linz | 2007 | https://www.linz.at (accessed on 12 March 2021) |

| 46 | Milanówek’s sustainable development indicators | Jagiellonian University, Warsaw University | Milanówek | 2012 | https://papers.ssrn.com (accessed on 12 March 2021) |

| 47 | Indicators for sustainable development of small towns | Vidzeme University of Applied Sciences, Maynooth University | Valmiera | 2013 | https://www.sciencedirect.com (accessed on 12 March 2021) |

| 48 | Indicators of Sustainable Community | Sustainable Seattle | Seattle | 1993 | https://www.sustainableseattle.org (accessed on 12 March 2021) |

| 49 | London’s Quality of Life Indicators | London Sustainable Development Commission | London | 2004 | https://data.london.gov.uk (accessed on 12 March 2021) |

| 50 | Key Performance Indicators for the Sino-Singapore Tianjin Eco-city | Singapore and Chinese Governments | Sino-Singapore Tianjin Eco-city | 2008 | https://www.mnd.gov.sg (accessed on 12 March 2021) |

References

- Newman, P.; Matan, I.; McIntosh, J. Urban Transport and Sustainable Development. In Routledge International Handbook of Sustainable Development; Redclift, M., Springett, D., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 337–350. [Google Scholar]

- Ahvenniemi, H.; Huovila, A.; Pinto-Seppä, I.; Airaksinen, M. What are the differences between sustainable and smart cities? Cities 2017, 60, 234–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, P.; Raghubanshi, A. Urban sustainability indicators: Challenges and opportunities. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 93, 282–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICLEI—Local Governments for Sustainability. ICLEI in the Urban Era—2019 Update; ICLEI: Bonn, Germany, 2019; p. 137. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Urbanization Prospects: The 2018 Revision; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2019; p. 39. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann, F. Nachhaltigkeit wofür? Von Chancen und Herausforderungen für eine nachhaltige Zukunft; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2016; p. 288. [Google Scholar]

- UN-Habitat. UN-Habitat’s COVID-19 Policy and Programme Framework; UN-Habitat: Nairobi, Kenya, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L.; Wu, J.; Yan, L. Defining and measuring urban sustainability: A review of indicators. Landsc. Ecol. 2015, 30, 1175–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mederly, P.; Hudeková, Z. Sustainable Urban Development in the Slovak Republic: Proposal of a Set of Indicators and Their Appliccation in order to Evaluate the Sustainable Development of Cities; Regional Environmental Center: Bratislava, Slovakia, 2006; p. 141. Available online: http://dx.doi.org/10.13140/2.1.4084.6401 (accessed on 19 August 2021).

- Huovila, A.; Bosch, P.; Airaksinen, M. Comparative analysis of standardized indicators for Smart sustainable cities: What indicators and standards to use and when? Cities 2019, 89, 141–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodbridge, M. Measuring, Monitoring and Evaluating the SDGs; ICLEI: Bonn, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Tanguay, G.A.; Rajaonson, J.; Lefebvre, J.-F.; Lanoie, P. Measuring the sustainability of cities: An analysis of the use of local indicators. Ecol. Indic. 2010, 10, 407–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, K.; Christodoulou, A. Review of sustainability indices and indicators: Towards a new City Sustainability Index (CSI). Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2012, 32, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICLEI—Local Governments for Sustainability. ICLEI—Local Governments for Sustainability: ICLEI—Brochure; ICLEI: Bonn, Germany, 2016; p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Novacek, P.; Mederly, P. How to Measure Progress towards Quality and Sustainability of Life? Ekológia (Bratislava) 2015, 34, 7–18. Available online: https://sciendo.com/article/10.1515/eko-2015-0002 (accessed on 19 August 2021).

- Braulio-Gonzalo, M.; Bovea, M.D.; Ruá, M.J. Sustainability on the urban scale: Proposal of a structure of indicators for the Spanish context. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2015, 53, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dahl, A.L. Contributions to the evolving theory and practice of indicators of sustainability. In Routledge Handbook of Sustainability Indicators; Bell, S., Morse, S., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 42–58. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development. In Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly on 25 September 2015; RES/70/1; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- UN-Habitat, Urban Thinkers Campus. The City We Need 2.0; UN-Habitat: Nairobi, Kenya, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. New Urban Agenda; United Nations: Quito, Ecuador, 2016; p. 48. [Google Scholar]

- Joss, S.; Rydin, Y. Prospects for Standardising Sustainable Urban Development. In Routledge Handbook of Sustainability Indicators; Bell, S., Morse, S., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 364–378. [Google Scholar]

- Hák, T.; Janoušková, S.; Moldan, B. Analýza Přístupů Municipalit k Plánování a Hodnocení Udržitelného Rozvoje; Charles University Environment Centre: Prague, Czech Republic, 2016; p. 96. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, M.S.; Fraser, E.D.G.; Dougill, A.J. An adaptive learning process for developing and applying sustainability indicators with local communities. Ecol. Econ. 2006, 59, 406–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. Earth Summit Agenda 21. The United Nations Programme of Action from Rio; United Nations Department of Public Information: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, M. A Systematic Review of Urban Sustainability Assessment Literature. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- European Commission Science for Environment Policy. In-Depth Report 12: Indicators for Sustainable Cities; Science Communication Unit, University of the West of England: Bristol, UK, 2018; p. 24. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Wu, T. Sustainability indicators and indices: An overview. In Handbook of Sustainability Management; Madu, C., Kuei, C., Eds.; Imperial College Press: London, UK, 2012; pp. 65–86. [Google Scholar]

- Hak, T.; Moldan, B.; Dahl, A.L. Sustainability Indicators: A Scientific Assessment; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2007; p. 448. [Google Scholar]

- Pinter, L.; Hardi, P.; Martinuzzi, A.; Hall, J. Bellagio STAMP: Principles for Sustainability Assessment and Measurement. In Routledge Handbook of Sustainability Indicators; Bell, S., Morse, S., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 21–41. [Google Scholar]

- Moldan, B.; Billharz, S. Sustainability Indicators: A Report of the Project on Indicators of Sustainable Development; John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 1997; p. 415. [Google Scholar]

- Meadows, D. Indicators and Information Systems for Sustainable Development—A Report to the Balaton Group; The Sustainability Institute: Hartland, WI, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, S.; Morse, S. Sustainability Indicators: Measuring the Immeasurable? Earthscan: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Waas, T.; Hugé, J.; Block, T.; Wright, T.; Benitez-Capistros, F.; Verbruggen, A. Sustainability Assessment and Indicators: Tools in a Decision-Making Strategy for Sustainable Development. Sustainability 2014, 6, 5512–5534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spangenberg, J.H. Indicators for sustainable development. In Routledge International Handbook of Sustainable Development; Redclift, M., Springett, D., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; pp. 308–322. [Google Scholar]

- Gudmundsson, H.; Hall, R.P.; Marsden, G.; Zietsman, J. Sustainable Transportation: Indicators, Frameworks, and Performance Management; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, S.; Morse, S. Routledge Handbook of Sustainability Indicators; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; p. 568. [Google Scholar]

- Ameen, R.F.M.; Mourshed, M.; Li, H. A critical review of environmental assessment tools for sustainable urban design. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2015, 55, 110–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joss, S.; Cowley, R.; De Jong, M.; Müller, B.; Park, B.-S.; Rees, W.; Roseland, M.; Rydin, Y. Tomorrow’s City Today: Prospects for Standardising Sustainable Urban Development; University of Westminster: London, UK, 2015; p. 52. [Google Scholar]

- Dizdaroglu, D. The Role of Indicator-Based Sustainability Assessment in Policy and the Decision-Making Process: A Review and Outlook. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gutowska, J.; Sleszynski, J.; Grodzinska-Jurczak, M. Selecting sustainability indicators for local community—Case study of Milanówek municipality, Poland. Probl. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 7, 77–86. [Google Scholar]

- Visvaldis, V.; Ainhoa, G.; Ralfs, P. Selecting Indicators for Sustainable Development of Small Towns: The Case of Valmiera Municipality. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2013, 26, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Diefenbacher, H.; Schweizer, R.; Teichert, V.; Oelsner, G. N!-Berichte für Kommunen Leitfaden zur Erstellung von kommunalen Nachhaltigkeitsberichten; Forschungsstätte der Evangelischen Studiengemeinschaft (FEST)—Institut für interdisziplinäre Forschung: Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; p. 57. [Google Scholar]

- Grabow, B.; Riedel, H.; Haubner, O.; Zumbansen, N.; Witte, K.; Honold, J.; Bauer, U.; Wolf, U.; Landua, D.; Gallep, P. Monitor Nachhaltige Kommune Bericht 2016—Teil 1: Ergebnisse der Befragung und der Indikatorenentwicklung; Deutsches Institut für Urbanistik, Bertelsmann Stiftung: Berlin, Gütersloh, Germany, 2016; p. 194. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, A.J.; Mosbah, S.M. Improving local measures of sustainability: A study of built-environment indicators in the United States. Cities 2017, 60, 301–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garau, C.; Pavan, V. Evaluating Urban Quality: Indicators and Assessment Tools for Smart Sustainable Cities. Sustainability 2018, 10, 575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Assmann, D.; Honold, J.; Grabow, B.; Roose, J. SDG-Indikatoren für Kommunen: Indikatoren zur Abbildung der Sustainable Development Goals der Vereinten Nationen in deutschen Kommunen; Bertelsmann Stiftung, Bundesinstitut für Bau-, Stadt- und Raumforschung, Deutscher Landkreistag, Deutscher Städtetag, Deutscher Städte- und Gemeindebund, Deutsches Institut für Urbanistik, Engagement Global: Gütersloh, Germany, 2018; p. 120. [Google Scholar]

- Janoušková, S.; Hák, T.; Švec, P. Metodika Hodnocení Udržitelných Měst: Audit Udržitelného Rozvoje pro Realizátory MA21 v ČR; Healthy Cities of the Czech Republic, Charles University Environment Centre: Prague, Czech Republic, 2017; p. 136. [Google Scholar]

- Spangenberg, J.H. The Institutional Dimension of Sustainable Development. In Sustainability Indicators: A Scientific Assessment; Hák, T., Moldan, B., Dahl, A.L., Eds.; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2007; pp. 107–124. [Google Scholar]

- Hak, T.; Kovanda, J.; Weinzettel, J. A method to assess the relevance of sustainability indicators: Application to the indicator set of the Czech Republic’s Sustainable Development Strategy. Ecol. Indic. 2012, 17, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, T.B. Sustainability Assessment: Exploring the Frontiers and Paradigms of Indicator Approaches. Sustainability 2019, 11, 824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bell, S.; Morse, S. Sustainability Indicators Past and Present: What Next? Sustainability 2018, 10, 1688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pufé, I. Nachhaltigkeit, 3rd ed.; UTB GmbH: Stuttgart, Germany, 2017; p. 322. [Google Scholar]

- Phillis, Y.A.; Kouikoglou, V.S.; Verdugo, C. Urban sustainability assessment and ranking of cities. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2017, 64, 254–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hák, T.; Janoušková, S.; Moldan, B. Udržitelné nebo chytré město? Urban. Územní Rozv. 2018, 20, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Spangenberg, J.H. World views, interests and indicator choices. In Routledge Handbook of Sustainability Indicators; Bell, S., Morse, S., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 143–155. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).