Abstract

Climate change and its consequences have called for actions to mitigate it, triggering society to act and speak out about sustainability policies. Movements like Fridays for Future (FFF) spread beyond the young people pressed for action to combat climate change. The present study aimed to (1) assess the environmental attitudes (EA) and knowledge (EK) of Brazilian and German students and (2) verify whether the frequency of participation in climate strikes changes according to these EA and EK. A total of 658 students participated in our study, 327 from Germany and 331 from Brazil (mean age 25.21 ± 7.91). We applied the Two Major Environmental Values (2-MEV) model and three-dimensional questionnaires to measure EA and EK, respectively. We applied a multivariate general linear model to assess the influence of the variables simultaneously. FFF participation is affected by EA, with strikers showing higher Preservation (PRE) and lower Utilization (UTL) scores; furthermore, our findings suggest that EK affects FFF participation, specifically system-related knowledge. The study adds to the increasing number of validations of the 2-MEV model in different languages and cultures and discusses the differences of EA and EK in student strikers and non-strikers between both countries.

1. Introduction

The debate about climate change and its consequences has called for actions to mitigate it year after year, triggering society to act and speak out about the environmental impact of humans on the planet. We are witnessing different environmental hazards, such as major floods, uncontrollable wildfires, deforestation of rainforests, and melting glaciers, that impact biodiversity and human life [1,2]. The environmental crisis has gained prominence beyond climate scientists and environmental education classes because it affects regions distributed around the six continents—although with considerable impacts on developing countries [3].

In 2018, a young Swedish high school student named Greta Thunberg used her civil rights to skip school on Fridays and stand in front of Sweden’s parliament to pressure political actors to take action for climate change mitigation [4]. Initially solitary, this protest infected thousands of young people around the world, creating a movement that spread beyond the young people who began to protest to press for action to combat climate change [5]. With this diversification of actors, organizations, and forms of protest, these demonstrations have now reached a total of 18,919 protests in more than 150 different countries around the globe [5,6].

As diverse as it is comprehensive in its participants and demands, these climate protest actions have gained momentum, placing young environmental activists as protagonists in movements that have emerged since 2018, such as Extinction Rebellion or Polluters Out, for example. Furthermore, they gained media and political attention, since Greta Thunberg became part of global leaders’ agendas, such as Angela Merkel and Justin Trudeau, and also spoke at the UN Climate Change Conference (COP24) and at the World Economic Forum [7,8,9,10,11,12].

There are differences between Western Europe and Latin America regarding the support for public policies for climate action, where the former show greater support than the latter [13]. Concerning climate action, 73% of the German population and 69% of the Brazilian population answered that “we should do everything necessary, urgently” in response to the climate emergency. Besides this support, other aspects like a country’s CO2 emission level could influence participation in protests: on one hand, it was positively associated with protest participation and involvement in an environmental group [14]; on the other hand, Sandvik (2008) [15] argues that the lower the CO2 emission level, the lower the environmental concern.

The next sections will focus on evidence from the literature review on environmental attitudes and knowledge, discussing the interplay between these two aspects of environmental behavior. Additional, they explain the theories about the collective action factors and their highlights for the field of environmental behavior and education. In this context, they seek to trace the paths to clarify the question and the design of the research conducted, the detailing of its methodological route, the description of the results, its discussion, and implications for future research.

1.1. Environmental Education—Knowledge and Attitudes

In the current context characterized by the evident environmental crisis, environmental education (EE) stands out as an educational process that goes from the scientific, political, and economic fields to the media and common sense, constituting an important mechanism for the resignification of the relationship between society and nature. Hategan [16] suggests that EE also has a multidisciplinary character, interplaying with concepts from other areas such as ecology, philosophy, and ethics, in an attempt to create a practice based on eco-philosophy.

A critical orientation of EE requires greater participation of science education (SE) to enhance with knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors the processes of teaching and learning, but also unveiling and relating the scientific, economic, political, and cultural aspects of environmental issues [17]. Environmental knowledge (EK) consists of three dimensions: system-related knowledge, action-related knowledge, and effectiveness knowledge [18]. The first comprises the concern with the natural processes of ecosystems and their effects on the man–nature relationship. The second is the available behavioral possibilities that are appropriate to address particular environmental problems. The third relates to the specific and effective impact of a particular action or an alternative compared to another [18,19].

We take for granted that individuals must be aware of the environmental reasons, ways, and consequences of their actions for environmental behavior to be cognitively substantial and empirically feasible [18,20]. The system-related knowledge dimension can be understood as simply EK, in its more conceptual and content dimension, and will not lead alone to attitude change [18]. Therefore, action-related knowledge and effectiveness knowledge also influence attitudes and behavior, which have their bases in system-related knowledge [20,21]. Thus, EE must act on these three dimensions, adopting different teaching strategies that address conceptual, procedural, and attitudinal learning [22].

To such a degree, one should consider that the different forms of knowledge, in isolation, have not produced the desired effect, i.e., appropriate environmental or ecological behavior [18]. Kaiser and Fuhrer [23] argue that the three dimensions of EK shall act together in a convergent cognitive movement. This knowledge convergence could lead to ecological behaviors, according to a common ecological goal—e.g., correct waste separation, reduced energy consumption, and change of eating habits, among others [18].

Supported by previous studies, Randler et al. [24] investigated German and Slovenian students and demonstrated the relationship between high levels of knowledge and preservationist attitudes. They also indicate a connection with an interest in learning in the context of attitudes towards wolves [24]. Liefländer and Bogner [25] argue that students with little effectiveness knowledge in a pre-test show an improvement on system-related and effectiveness knowledge after participation in an EE program. Their study indicates that only action-related knowledge is harder to improve. Hence, to increase effectiveness knowledge, students need to understand how to behave through different actions, which outlines the importance and complexity of the action-related knowledge dimension [26]. Increasing the amount of EK is still an important aspect, because financial penalties display a role more significant to environmental behavior and EA, e.g., segregating municipal waste [27].

Environmental attitudes (EA) are characterized as favorable or unfavorable feelings towards nature or some problem that comes from it, and are officially defined as “perceptions or convictions regarding the physical environment, including factors that affect its quality” [28]. Therefore, they are attitudes constructed or inculcated from the interaction with the context in which one lives in its totality, as well as belonging to and interplaying with other internal and external factors [29]. In addition to the level of awareness that is often related to the appreciation of nature, EA also relate to natural or anthropic processes in which the environment is the attitudinal object [30]. However, it is important to take into account that attitudes are still fundamental to alternatives and policies that aim at social change [31].

In the context of the educational process, children’s attitudes and knowledge are enhanced through contact with animals, for example, showing that direct experiences with nature cause a more lasting and consistent development, consolidating over time [32]. It is noteworthy that education about and for the environment is important in the socio-environmental crisis, and is parallel to some SE curriculum documents that argue about inquiry teaching for knowledge, values, attitudes, and ethics [17]. However, we must consider that a change in attitude and gain in knowledge will not lead directly to a change in behavior unless we consider the social contexts in which the knowledge and attitudes are investigated [31].

1.2. Two Major Environmental Values

To measure environmental attitudes and values, supported by a solid theoretical framework, the Two Major Environmental Values (2-MEV) model questionnaire was created [33], which comprises twenty questions based on first-order factors (attitudes) that can predict higher-order factors (values). These higher-order factors were categorized into Preservation (PRE) and Utilization (UTL); the first describes values related to “a bio-centric dimension that reflects conservation and protection of the environment”, and the latter indicates an “anthropocentric dimension that reflects the utilization of natural resources’’ [34] (pp. 787). For example, first-order factors such as concern with natural resources and appreciation of nature combine with the higher-order factor of PRE, while alteration of nature and the dominion of man corresponds to that of UTL [33]. It should be considered that a change in attitude and gain of knowledge will not lead directly to a change in behavior, unless one considers the social contexts in which knowledge and attitudes are investigated, although these attitudes remain important for policies that seek social change [26,29,35].

With robust theoretical grounding, the 2-MEV scale has been tested and applied over the past decades in different countries, e.g., in Germany, the Ivory Coast, the United States, Greece, Ireland, and Mexico, among others [21,36,37,38,39,40]. The scale’s application demonstrated high reliability and correlation among its components in different cultures, revealing environmental attitudes and values of students from different educational levels [36,37,38,39,40]. More recently, Bogner [37] suggests that measuring Appreciation of Nature, in addition to the UTL and PRE values, may enhance its ability as a tool for evaluating EE programs and promoting less exploitative preferences of nature. Thus, it assists investigations into how direct and indirect experiences in nature can influence an individual’s environmental behavior [29,41]. Additionally, the scale has been used in conjunction with measurements of self-reported behavior and EK levels in studies evaluating EE programs, suggesting its suitability and weak to moderate correlation with these other cognitive elements of environmental behavior [42].

1.3. Collective Action and Fridays for Future

Fridays for Future (FFF) protests have become the subject of research by various researchers, but mainly in Europe [43]. From the perspective of research on protest participation, psychologists investigated the profile, motivations, and beliefs of protesters in several European cities in 2019 [43]. Concerning collective action, researchers from different fields suggest several socio-psychological factors that influence an individual to participate in a demonstration, such as social identification, perception of injustice, and certain affective and cognitive aspects [44].

Brügger et al. [45] suggest that FFF participants had two psychological processes which relate to the greater participation of this group of young people: social identity, with a greater degree of influence to the identification to that group of other young persons also protesting for climate protection; and risk perception, with the perception and assessment of climate change risks being affective and cognitive factors, respectively. However, the authors investigated German-speaking young people who live in a region of Switzerland and suggest that future research should further investigate the relationship between collective identity and risk perception. The authors suggest the latter can lead to collective action without necessarily involving the former.

It is essential to understand the importance of participation in groups or in rallies for environmental protection due to members’ individual and social motivations and the practical consequences of these collective actions [44]. The approach of social identity theory to explain collective action argues that its participants may be motivated by identification with the group itself; at the same time, these could be precursors of social and political change [46]. In another study, Fielding et al. [47] demonstrate that the intention to become an environmental activist can be predicted because they participate in groups for environmental protection. Therefore, young environmental activists and their influence can go beyond sympathizers, friends, or family members, since they can influence the political sphere, elites, and other members of societies who do not know these groups or the causes they are defending [46].

To our knowledge, no study has aimed to measure with the 2-MEV scale the environmental attitudes of participants in FFF or any related movements. Thus, we aim to investigate the environmental attitudes and values of participants and non-participants in protests for environmental protection.

1.4. The Present Study

As shown above, the 2-MEV scale was applied in studies about EA in different countries, yet we still do not know its applicability and results of using this instrument in the Brazilian context. This scale has a fixed dimensional structure, the possibility of application in comparative studies, and suitability in the psychology of sustainable development [26]. Consequently, there is a contribution to the understanding of the EA and values of Brazilian students.

Considering the participation in FFF protests, the study on the established theories on participants and non-participants of climate strikes can help to understand the motivations of these young people, albeit studies on these objectives are still scarce [35]. We know that the discourse that has incited young people around the world to leave classrooms and take to the streets to protest against politicians is composed of concerns about their future and scientific information from research conducted by climate scientists [48]. In this context, the strength and potential of socio-psychological determinants of a cognitive nature are capable of providing some understanding about whether EA, values, and EK may be predictors of whether or not they participate in FFF protests.

The present study applied a survey through a questionnaire with multiple choice and agreement level questions related to EA, values, and EK (details are in the next section). Furthermore, we sought to identify participants as to the frequency of their environmental activism, such as in the FFF movement. The participants from our survey were invited from an active search on social media for the FFF movement in Brazil and Germany, as well as an email released to undergraduate and graduate students at two universities, one in the city of Porto Alegre (Brazil) and the other in the city of Tübingen (Germany).

The present study aimed to (1) assess the EA and EK of Brazilian and German students and (2) verify whether the frequency of participation in climate strikes changes according to these EA and EK. The independent variables included were country, age, gender, educational level, and urbanization degree of the place of residence.

Hypothesis 1.

Exploitative attitudes about nature are higher in older students (1a), while more preservationist attitudes are more prominent in younger students, although a greater effect is expected according to educational level (1b).

Hypothesis 2.

The attitudes of students living in rural regions are more positive compared to students living in urban areas (2a), although the largest expected effect is according to gender (2b) and students’ country (2c).

Hypothesis 3.

German students have higher environmental knowledge scores than Brazilian students (3a). We predict that this effect is larger for all three dimensions of environmental knowledge (3b).

Hypothesis 4.

Higher environmental preservation value and higher scores on environmental knowledge are seen in students who participated in protests with environmental causes, such as Fridays for Future.

2. Materials and Methods

The present article is derived from exploratory research, the type of which was a survey. We used the online tool SoSciSurvey to collect the data on Brazilian and German students, both participants and non-participants in protests with an environmental topic, especially Fridays for Future (FFF) strikes.

2.1. Sample

The participants of our survey were invited from an active search on social media for the FFF movement in Brazil and Germany, as well as an email released to undergraduate and graduate students at a university in Porto Alegre (Brazil) and Tübingen (Germany). A total of 658 students participated in our study, 327 from Germany (204 female, 110 male, 3 diverse and 4 preferred not to answer) and 331 from Brazil (207 female, 121 male, and 3 diverse).

The mean age of all participants was 25.21 ± 7.91 (range was 16–65 years). In Germany, the mean age was 23.02 ± 5.14 (range was 16–61 years) and in Brazil, the mean age was 27.38 ± 9. 43 (range was 16–65 years). Regarding the age range of all participants who reported their age, 46.6% belonged to the 16–22 age group; 35.4% to 23–29; 9.9% to 30–36; 3.8% to 37–43; and 4.3% to 44–65. In Germany, the age groups were distributed in the following way: 56.6% in 23–29; 36% in 23–29; 5.5% in 30–36; 0.9% in 37–43; and 0.9% in 44–65. In Brazil, the age groups were distributed in slightly different ways: 36.7% in the 16–22 range; 34.8% in the 23–29 range; 14.2% in the 30–36 range; 6.8% in the 37–43 range; and 7.6% in the 44–65 range.

All participants in our study were students at some level of education. In total, 34 participants were from high school and/or technical education (20 from Germany and 14 from Brazil), 333 were undergraduate students (145 from Germany and 188 from Brazil), and 291 were Specialization/Master/Doctorate students (162 from Germany and 129 from Brazil). The participants had to read the invitation with the survey goals, risks, and benefits before answering the questionnaire. Additionally, participants could withdraw from completing the questionnaire at any time. In the general linear models, only participants with data for the given variables were retained. There were 402 women and 223 men, 314 German participants and 311 Brazilian participants. 165 were classified as rural and 460 as city-dwellers (urban). 475 never participated in FFF, but 150 did at least once or several times. Education levels were as follows: 1 = 31, 2 = 315, and 3 = 279.

2.2. Measurements

A battery of questionnaires was used. We collected sociodemographic data, namely: age, gender, country, characteristic of the place of residence (urban/rural), level of education, name of the course they are attending (if undergraduate or graduate), and parents’ education levels. Country was coded into Brazil/Germany. Urbanization was assessed with a slider bar from rural (0) to urban (100), and later dichotomized in values above and below a 50% threshold. We did not assess the hometown size because this greatly differs between Brazil and Germany, but rather used a subjective assessment of urbanization, because, e.g., a city with 70,000 inhabitants may be rather urban in Germany but not in Brazil. Participation in FFF actions was asked for in a categorical variable (never (1), one time (2), two–four times (3) or five or more times (4)), but later grouped into never/one time and two or/and more times because of the sample sizes.

To measure environmental attitudes, we used the Two Major Environmental Values (2-MEV) scale with 20 questions (ten about Utilization (UTL) and ten about Preservation (PRE)), derived from Bogner [49]. The environmental knowledge questions were extracted from Roczen et al. [19] and Geiger et al. [50]: five on system-related knowledge; four on action-related knowledge; and five on effectiveness knowledge. For the purpose of measuring the average number of questions answered correctly in the three dimensions, the correct alternative was re-encoded to the value 1, and the incorrect alternatives were re-encoded to the value 0.

The questions on environmental activism were extracted and adapted from Wahlström [43] and Heißel [51]. For an equal evaluation of the samples from both countries, the same questionnaires were translated into German and back-translated into English (or vice versa, depending on the language of the original instrument) before the two versions were compared. An official representative for German to Portuguese translations did the first translation; this version was reviewed by two Brazilian Science teachers and researchers in Science Education to put it in a more contextualized way. After this process, we obtained the Portuguese version of the questionnaires (Please see the questionnaires at the Supplementary Materials Tables S1–S3).

2.3. Statistical Methods

We applied a confirmatory factor analysis on the factor structure of the 2-MEV scale with AMOS 27.

We calculated the Cronbach’s α coefficient to analyze the reliability and the internal consistency of the 2-MEV. Although there is no minimum threshold for a reliability coefficient to be considered adequate, the coefficient of Cronbach’s α above 0.700 is weighed as acceptable and satisfactory [52]. For the UTL domain in German and Portuguese languages, we obtained a Cronbach’s α of 0.752 and 0.810, respectively; for the PRE domain in German and Portuguese languages, we obtained a Cronbach’s α of 0.814 and 0.850, respectively. Hence, all scales demonstrated adequate levels of reliability and internal consistency. To confirm that environmental values (UTL and PRE) and environmental knowledge (system-related knowledge (SYS), action-related knowledge (ACT) and effectiveness (EFF)) were measured and fit in two distinct models, we also performed Pearson’s correlation test.

To assess the influence of the variables simultaneously, we applied a multivariate general linear model with the UTL and PRE values as dependent variables in the first model, and SYS, ACT, and EFF knowledge as dependent variables in the second model. For both models, country, gender, age, urbanization, level of education, and participation in FFF protests were independent variables. Partial eta-square was used as a measure of effect size. The multivariate models were followed by subsequent univariate models to estimate the influence of the independent variables in UTL and PRE separately, as well as in SYS, ACT, and EFF separately. All analyses were performed in IBM SPSS 25.

3. Results

First, we present the results of the correlation between the questionnaires used to measure environmental attitudes and environmental knowledge. For this purpose, we performed Pearson’s correlation test (Table 1 below). Spearman’s correlation showed that there is no relationship between the two dimensions of the Two Major Environmental Values (2-MEV) scale and the questionnaire of the three dimensions of environmental knowledge [21,25].

Table 1.

Pearson‘s correlations between 2-MEV scale and Environmental Knowledge questionnaire.

3.1. 2-MEV Scale and Students Environmental Attitudes

The Brazilian sample showed a good fit of the measurement model with CMIN/df = 3.597, CFI = 0.797, and RMSEA = 0.089 (95% CI: 0.081, 0.096). In the German sample, CMIN/df was 3.614, CFI = 0.748, and RMSEA = 0.090 (95% CI: 0.082, 0.097). When allowing error covariances between e16 and e17 (from PRE), CFI improved to 0.791 and RMSEA to 0.082. Thus, there is configural invariance across the countries. In the multigroup confirmatory factor analysis, the unconstrained model showed a better RMSEA with 0.064 (95% CI: 0.060, 0.068); CFI was 0.767, allowing error covariances e16 and e17 decreased the RMSEA to 0.059, and CFI was 0.805.

The multivariate general linear model revealed a significant influence of gender, country and Fridays for Future (FFF) participation. Urbanization, age, and educational level were not significant (Table 2 below).

Table 2.

Results of the multivariate linear model with PRE and UTL as dependent variables, and gender, country, urbanization, educational level, and FFF participation as independent factors. Age was used as a covariate to account for different ages of the students.

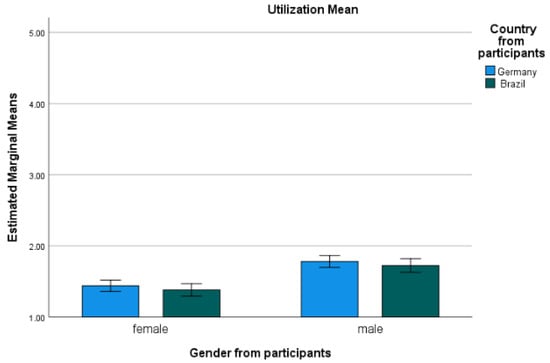

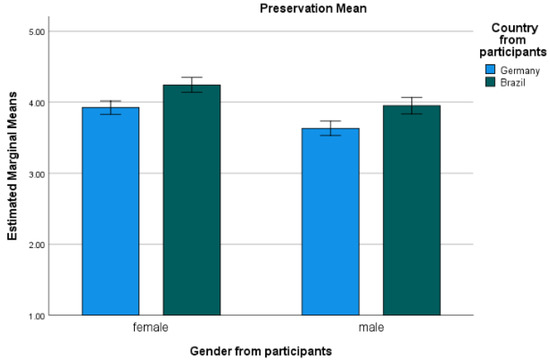

Subsequent univariate models were carried out for Utilization (UTL) and Preservation (PRE) separately (Table 3 below). Gender had a significant effect on both. Women were more PRE and less UTL oriented than men (Figure 1 and Figure 2. Women scored on average 4.08 ± 0.044 and men 3.79 ± 0.049 in PRE, and 1.41 ± 0.036 and 1.75 ± 0.040 in UTL, respectively. This supports our hypothesis 2b.

Table 3.

Univariate models on Utilization (UTL) and Preservation (PRE).

Figure 1.

Utilization mean scores in gender and country. Covariates appearing in the model are evaluated at the following values: mean age of participants = 25.288. Error bars: 95% CI.

Figure 2.

Preservation mean scores in gender and country. Covariates appearing in the model are evaluated at the following values: mean age of participants = 25.288. Error bars: 95% CI.

The FFF participants from both countries showed lower scores on UTL and higher scores on PRE. Regarding UTL, the FFF non-participants scored 1.675 (S.E. = 0.044) and FFF participants scored 1.487 (S.E. = 0.035); regarding PRE, the FFF non-participants scored 3.718 (S.E. = 0.043) and FFF participants scored 4.158 (S.E. = 0.054). This supports our hypothesis 4.

Concerning countries, Brazilian participants differed in PRE but not in UTL (Table linear models above). However, concerning PRE, Brazilians scored 4.098 (S.E. = 0.051) and Germans scored 3.778 (S.E. = 0.044). This supports our hypothesis 2c. In our model, age, level of education, and characteristics of the city (rural or urban) did not influence the UTL and PRE scores of the survey participants. This does not support our hypotheses 1a, 1b and 2a.

3.2. 2-MEV Scale and Students Environmental Attitudes

The multivariate general linear model revealed a significant influence of gender and country. Age, FFF participation, educational level, and urbanization were not significant (Table 4 below).

Table 4.

Results of the multivariate linear model with system-related knowledge (SYS), action-related knowledge (ACT), and effectiveness knowledge (EFF) as dependent variables, and gender, country, urbanization, educational level, and Fridays for Future (FFF) participation as independent factors. Age was used as a covariate to account for different ages of the students.

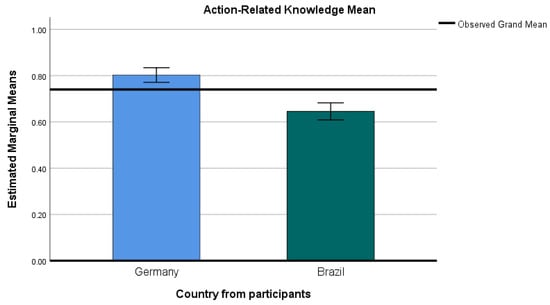

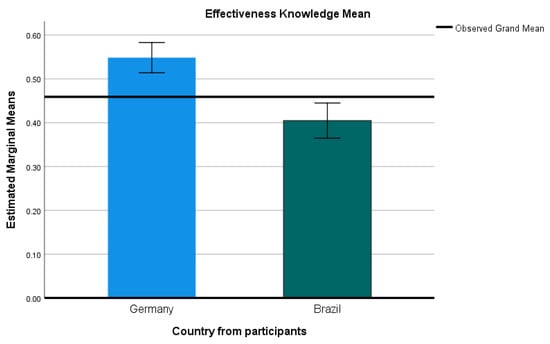

Subsequent univariate models were carried out for SYS, ACT, and EFF separately (Table 5 below). Country had a significant effect on two environmental knowledge dimensions. German students had higher scores on ACT and EFF than Brazilian ones. German students scored on average 0.803 ± 0.016 and Brazilian students 0.645 ± 0.19 in action-related knowledge, and 0.548 ± 0.018 ± 0.405 in effectiveness knowledge, respectively (Figure 3 and Figure 4). This partially supports our hypothesis 3a. However, there was no significant effect on system-related knowledge, in which German students scored on average 0.926 ± 0.009 and Brazilian students 0.931 ± 0.011. This does not support our hypothesis 3b.

Table 5.

Univariate models for system-related knowledge (SYS), action-related knowledge (ACT), and effectiveness knowledge (EFF).

Figure 3.

Action-related knowledge mean scores in Germany and Brazil. Covariates appearing in the model are evaluated at the following values: mean age of participants = 25.288. Error bars: 95% CI.

Figure 4.

Effectiveness mean scores in Germany and Brazil. Covariates appearing in the model are evaluated at the following values: mean age of participants = 25.288. Error bars: 95% CI.

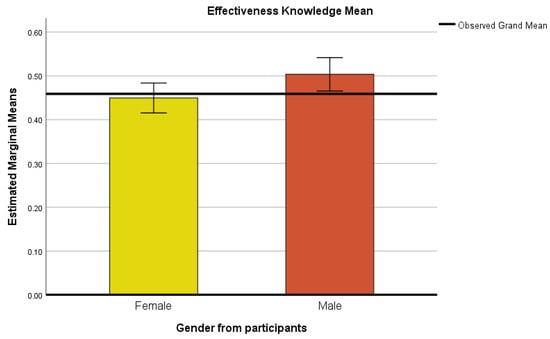

Gender had a significant effect on at least one dimension of environmental knowledge. Male students had higher scores on EFF than female students (Figure 5). Male students scored on average 0.504 ± 0019 and females 0.449 ± 0.017 in effectiveness knowledge, respectively. There was no significant effect on system-related knowledge, in which male students scored on average 0.931 ± 0.010 and female students 0.927 ± 0.009; furthermore, we did not find a significant effect on action-related knowledge, in which male students scored on average 0.712 ± 0.018 and female students 0.737 ± 0.016.

Figure 5.

Effectiveness mean scores of women and men. Covariates appearing in the model are evaluated at the following values: mean age of participants = 25.288. Error bars: 95% CI.

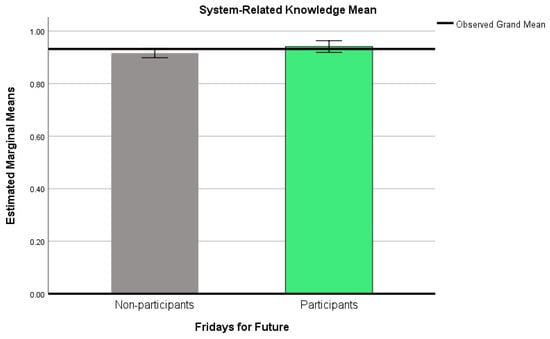

Concerning FFF participation, it had a significant effect on at least one dimension of environmental knowledge. FFF participants had more system-related knowledge than those who did not participate in climate strikes (Figure 6). FFF participants scored on average 0.941 ± 0.011 and FFF non-participants 0.916 ± 0.009 in SYS, respectively. But we did not find a significant effect on other environmental knowledge dimensions. In ACT, the FFF participants scored on average 0.740 ± 0.020 and FFF non-participants 0.708 ± 0.016; in EFF, the FFF participants scored on average 0.486 ± 0.021 and FFF non-participants 0.467 ± 0.017.

Figure 6.

System-related knowledge mean scores of FFF participants and non-participants. Covariates appearing in the model are evaluated at the following values: mean age of participants = 25.288. Error bars: 95% CI.

4. Discussion

The study adds to the increasing number of validations of the Two Major Environmental Values (2-MEV) model in different languages and cultures. Here, the Brazilian version was found to be applicable in Brazil, showing a stable two-factor solution. This adds to previous studies supporting this model [21,36,37,38,39,40,42]. In our study, the scale showed no statistical need for modification of the primary factors. But the 2-MEV scale was modified in a previous study in the Latin American context, where two primary factors of Preservation (PRE) (Intention to Support and Concern for Resources) were merged [53]. The authors found that Mexican students hold low Utilization (UTL) scores and high PRE scores, corroborating our findings in the Brazilian context.

Participation in Fridays for Future (FFF) protests was shown to significantly affect environmental attitudes (EA) and values according to mean PRE and UTL scores. Additionally, our findings suggest that it can significantly affect environmental knowledge (EK), specifically system-related knowledge (SYS). Students who engaged in protests in defense of the environment demonstrated lower UTL scores and higher PRE scores compared to students who did not actively participate. This indicates that participants in these strikes, such as the FFF, are more concerned about preserving the environment and have a less exploitative view of nature’s resources. Previous studies have shown that participation in FFF protests was motivated by group identification and perceived risk of the environmental consequences of climate change [45]. Recently, Camona-Moya et al. [54] demonstrated that environmental identity and positive emotions towards environmental deterioration are correlated with environmental collective action, shedding light on individual aspects of such action.

We suggest that the EA and EK scales be applied with FFF participants during on-site protests, following appropriate data collection methodology during street demonstrations. Although still incipient, research with strike participants such as those in FFF should be considered with other findings in the literature on EA and EK, highlighting the importance of SYS for the other dimensions of EK, and this cognitive factor for attitudes, values, and reported behavior [21,25].

This difference between strikers and non-strikers also remained when analyzing the two countries, i.e., pro-environmental attitudes are a significant factor in the willingness to protest in defense of climate protection in Germany and Brazil. This is important because the current challenge is the participation of different civil society actors and the politics focused on climate change mitigation [55]. Thus, the street demonstrations prove to play an important role in climate politics ins Germany [56], pointing to attitudes that should be promoted and analyzed in different instances, for example, in environmental education (EE) [45].

When we analyzed only the difference between countries, we also discovered significant differences in the PRE and UTL mean scores between Brazilian and German students. We found that Brazilians are more concerned about the environment and less favorable to the exploitation of nature when compared to German students. Hence, our model suggests that the level of development of a country or its wealth does not necessarily indicate more pro-environmental attitudes when compared to a developing country. This is paralleled to a study about animal welfare attitudes, showing highest scores in a less developed country and lowest scores in Germany [57]. Although post-materialistic values may express higher environmental concern [58]—which is formed, among other things, by EA —one must consider situational constricts, local environmental effects, or other individual factors [29,59,60].

The difference between the countries found in our study can be discussed with the findings of the survey conducted on the general population by the United Nations Development Programme (UNPD) and Oxford University [2]. This report showed that in Germany, 83% of young people believe in the climate emergency, while 69% of young Brazilians answered the same. Regarding climate action, 73% of the German population and 69% of the Brazilian population answered that “we should do everything necessary, urgently” in response to the climate emergency. Nevertheless, this reinforces the importance of EE programs for sustainable development in both countries. High PRE scores indicate motivation, better learning performance, and also correlates with high levels of knowledge on biodiversity and species conservation [24,42].

In the model on EK, our results showed differences between the average scores, in which German students have higher average scores in at least two dimensions: action-related knowledge (ACT) and effectiveness knowledge (EFF). On the one hand, these students showed more concrete awareness about the environmental costs of recycling certain types of materials or about the consequences of pollution or knew the definition of the Paris Agreement better. Furthermore, they also showed more knowledge about daily attitudes that are more efficient in conserving energy, water, and generally reducing the environmental costs of their daily lives. On the other hand, the mean scores of Brazilian students indicate the potential for an increase in this cognitive factor, which should be handled through different didactic strategies in environmental education programs [14]. Thus, the increase in these knowledge dimensions could lead to investigations about their impacts on environmental attitudes and behavior [26].

The importance of EK‘s role in environmental behavior is a recurring topic in the literature, but in general, it is highlighted as a weak or moderate predictor [50]. These authors argued recently that EK‘s subdomains may not be appropriate for environmental education [50]. However, it is more a methodological question that needs attention when taking into consideration that these subdomains’ convergence is of importance to environmental behavior [23]. It was demonstrated that the two mentioned subdomains are relevant for individual actions indicative of environmental concern, which relate to EA [59]. Nevertheless, the importance of both general knowledge and EK and their ability to be enhanced by environmental education programs remains, as well as the relationship of the different subdomains to short- and medium-term behavior change [25,26,50]. The importance of these three dimensions of environmental knowledge is also evident due to the need for a relationship between the EE program contents and how to specifically behave in a pro-environmental way [61], establishing this connection between behavior and SYS and ACT or EFF knowledge.

We also found significant gender differences in mean scores on PRE and UTL. In our model, female students showed higher mean PRE scores and lower mean UTL scores than males. This difference occurred in both Germany and Brazil. This gender difference is much debated and studied in the literature on environmental attitudes. Zelezny et al. [62] describe in their literature review that women held stronger pro-environmental attitudes than men, discussing the role of socialization for more social responsibility. Furthermore, Blake [58] pointed out the same gender effect on environmental concern. Recently, other studies suggest the same findings as our model on the effect of gender on environmental values, and also its relationship to authoritarianism [40,63,64]. Thus, other authors have also identified that gender may not be a significant factor in EA among students [21,55]. We acknowledge that there may not be differences in PRE scores between women and men; on the other hand, male students have higher UTL scores in different measurement methods [65]. In any case, we argue that the gender effect may play a role because of socialization [62].

Regarding EK, we found significant differences in only one dimension. Male respondents had higher mean scores on knowledge about effectiveness than female respondents, in contrast to other studies [21]. The authors also show that the major difference between higher and lower achievers is in the EFF subdomain. Nonetheless, gender was not relevant to the general EK mean scores, revealing little difference between men and women.

Finally, our models of EA and EK did not demonstrate statistical significance for age, educational level, and urbanization factors. We can hypothesize that these sociodemographic variables were not relevant in our sample due to the difference in the number of undergraduate and postgraduate students, and the low participation of high school students. Additionally, we did not find urbanization differences, as participants’ EA and EK mean scores did not differ between rural and urban residents, whereas this concept is distinct between Germany and Brazil due to geographical and cultural attributes. Age also did not prove relevant; however, we point out that the sample range was high in both countries, and age is correlated with other sociodemographic variables, such as educational level [2,14].

4.1. Limitations

There are some limitations to our study. First, contact with the FFF, Polluters Out, and Extinction Rebellion movements was more difficult in Brazil, in contrast to the high social media activity of these movements in Germany. Therefore, the number of participants of these movements may be larger when interviewed during street demonstrations. Second, we accessed only students from one university in each country. Finally, the data collection was performed with an online questionnaire, and we acknowledge that not every person has access to the internet. Therefore, our sample could not reach students from both countries who do not frequently access their email or social media. Given these difficulties related to the data collection technique, some variables were difficult to control for in the sample analyzed. Movements like the FFF are part of a new research topic, and collective action was mostly online in the year 2020. We encourage that future studies should improve on introducing newer aspects, but nevertheless, applying the Two Major Environmental Values model is a great way towards constructing a standardized method of measurement. A more representative sample, as well as including further countries to assess the relationship between developmental status and FFF action would help to shed more light onto this aspect.

4.2. Implications

This study shows that scientists need to be able to respond to new movements in society and to use already existing, highly validated measurement instruments, such as the 2-MEV model for newly emerging topics. It also shows that environmental concern and action (as in the FFF movement) are related, and it presents some kind of criterial validity for the 2-MEV model, because FFF participants showed higher scores.

5. Conclusions

Our study aimed to assess the environmental attitudes and knowledge of Brazilian and German students, who had or had not participated in protests with environmental causes, such as Fridays for Future (FFF). The study adds to the increasing number of validations of the Two Major Environmental Values (2-MEV) model in different languages and cultures. Here, the Brazilian version was found to be applicable in Brazil, showing a stable two-factor solution.

We saw that participation in FFF was a determining factor in explaining high preservationist and low utilitarian scores on environmental attitudes. This is of high importance considering the intensity and relevance of these protests since their beginning in 2018 [55]. It was expected that students or non-students participating in these protests showed more biocentric or altruistic environmental attitudes [58], but this study sought to add the other side: what impact changing attitudes and behavior might have on participation in protests. Climate change is an issue of our time, and it is important to elucidate how these protests impact environmental policies around the world. Thus, we can better understand how civil society takes part in exercising its rights and claims or proposes political agendas, and assess these collective action achievements in mitigating climate change. It is worth noting that the last year was marked by FFF online protests due to the COVID-19 crisis, raising questions about whether participation has increased and how effective it was.

This comparative study between Brazil and Germany provided, among other factors, the differences in attitudes and knowledge levels between students in these countries. Environmental behavior is relevant and extensively studied in the past decades, and this cross-cultural perspective shows that Brazilians could benefit from learning more about sustainability topics. Finally, we can suggest Brazil’s potential to implement policies and subsidies to increase environmental protection, as is most evident in Germany, and by doing it increase its impact on the Brazilian population.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su13148010/s1, Table S1: original German version and the Portuguese version translated of the Two Major Environmental Values scale applied in the study, extracted and adapted from Bogner (2007); Table S2: sociodemographic and Fridays for Future participation questions in German and Portuguese; Table S3: Questions of Environmental Knowledge in German and Portuguese, extracted and adapted from Geiger, Geiger and Wilhelm (2019) and Roczen et al. (2014).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.d.A.B., C.R. and J.V.L.R.; methodology, R.B., C.R. and J.V.L.R.; formal analysis, R.B and C.R.; investigation, R.d.A.B.; data curation, R.d.A.B.; writing—original draft preparation, R.d.A.B.; writing—review and editing, C.R. and J.V.L.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by DEUTSCHER AKADEMISCHER AUSTAUSCHDIENST (DAAD), grant number 57507870, and by Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—Brasil (CAPES)—FINANCE CODE 001.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of Office no. 2/2021, regarding research in virtual environments, attached to Resolution no. 510/2016 of the National Health Council of Brazil, and approved by the Research Committee of the Institute of Basic Sciences and Health of the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul (no. 37973, 11 September 2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available from the first author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

This study had the support of Naomi Staller in configuring the questionnaire on the platform used, and Nadine Kalb in the conceptualization and translation review of environmental knowledge questions. We appreciate the suggestions of the reviewers and the academic editor that resulted in improving this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Handmer, J.; Honda, Y.; Kundzewicz, Z.W.; Arnell, N.; Benito, G.; Hatfield, J.; Mohamed, I.F.; Peduzzi, P.; Wu, S.; Sherstyukov, B.; et al. Changes in impacts of climate extremes: Human systems and ecosystems. In Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation; Field, C.B., Barros, V., Stocker, T.F., Dahe, Q., Eds.; A Special Report of Working Groups I and II of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC); Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 231–290. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction. Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction; United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR): Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Coulibaly, T.; Islam, M.; Managi, S. The Impacts of Climate Change and Natural Disasters on Agriculture in African Countries. Econ. Disasters Clim. Chang. 2020, 4, 347–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gessen, M. The Fifteen-Year-Old Climate Activist Who Is Demanding a New Kind of Politics. New Yorker. Available online: https://www.newyorker.com/news/our-columnists/the-fifteen-year-old-climate-activist-who-is-demanding-a-new-kind-of-politics (accessed on 2 October 2018).

- Fridays for Future. Map of Actions. Available online: https://fridaysforfuture.org/action-map/map/ (accessed on 19 February 2021).

- Feeley, C. Greta Thunberg: A Year to Change the World’ Underway from the BBC & PBS. Hollywood Insider. Available online: https://www.hollywoodinsider.com/greta-thunberg-a-year-to-change-the-world/ (accessed on 18 February 2021).

- Carrington, D. Our Leader Are Like Children, School Strike Founder Tells Climate Summit. The Guardian. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2018/dec/04/leaders-like-children-school-strike-founder-greta-thunberg-tells-un-climate-summit (accessed on 4 December 2018).

- The Guardian. Greta Thunberg Meets Justin Trudeau Amid Climate Strikes: ‘He Is Not Doing Enough’. Guardian Staff and Agencies in Montreal. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/sep/27/greta-thunberg-justin-trudeau-meeting-climate-strikes (accessed on 27 September 2019).

- NPR. Transcript: Greta Thunberg’s Speech at the U.N. Climate Action Summit. National Group Radio Staff. Available online: https://www.npr.org/2019/09/23/763452863/transcript-greta-thunbergs-speech-at-the-u-n-climate-action-summit?t=1613999375712&t=1616181885328 (accessed on 23 September 2019).

- Rankin, J. Forget Brexit and Focus on Climate Change, Greta Thunberg Tells EU. The Guardian. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/apr/16/greta-thunberg-urges-eu-leaders-wake-up-climate-change-school-strike-movement (accessed on 16 April 2019).

- World Economic Forum. Greta Thunberg: Our House Is Still on Fire and You’re Fueling the Flames. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/01/greta-speech-our-house-is-still-on-fire-davos-2020/ (accessed on 21 January 2020).

- ZDF. Klimaschutzgespräch: Thunberg Trifft Merkel im Kanzleramt. Zweites Deutsches Fernsehen. Available online: https://www.zdf.de/nachrichten/politik/treffen-merkel-thunberg-100.html (accessed on 10 January 2019).

- United Nations Development Programme and University of Oxford. Peoples’ Climate Vote. Results. Available online: https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/librarypage/climate-and-disaster-resilience-/The-Peoples-Climate-Vote-Results.html (accessed on 19 April 2021).

- Post, D.; Meng, Y. Does schooling foster environmental values and action? A cross-national study of priorities and behaviors. Int. J. Educ. Dev. 2018, 60, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandvik, H. Public concern over global warming correlates negatively with national wealth. Clim. Chang. 2008, 90, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hategan, V.-P. Promoting the Eco-Dialogue through Eco-Philosophy for Community. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedretti, E. Environmental Education and Science Education: Ideology, Hegemony, Traditional Knowledge, and Alignment. RBPEC 2014, 14, 305–314. Available online: https://periodicos.ufmg.br/index.php/rbpec/article/view/4370 (accessed on 1 June 2021). [CrossRef]

- Frick, J.; Kaiser, F.G.; Wilson, M. Environmental knowledge and conservation behavior: Exploring prevalence and structure in a representative sample. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2004, 37, 1597–1613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roczen, N.; Kaiser, F.G.; Bogner, F.X.; Wilson, M. A Competence Model for Environmental Education. Environ. Behav. 2014, 46, 972–992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, F.G.; Roczen, N.; Bogner, F.X. Competence formation in environmental education: Advancing ecology-specific rather than general abilities. Umweltpsychologie 2008, 12, 56–70. [Google Scholar]

- Maurer, M.; Bogner, F.X. Modelling environmental literacy with environmental knowledge, valuesand (reported) behaviour. Stud. Educ. Eval. 2020, 65, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liefländer, A.K.; Bogner, F.X. The Effects of Children’s Age and Sex on Acquiring Pro-Environmental Attitudes Through Environmental Education. J. Environ. Educ. 2014, 45, 105–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, F.G.; Fuhrer, U. Ecological Behavior’s Dependency on Different Forms of Knowledge. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 52, 598–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randler, C.; Wagner, A.; Rögele, A.; Hummel, E.; & Tomažič, I. Attitudes toward and Knowledge about Wolves in SW German Secondary School Pupils from within and outside an Area Occupied by Wolves (Canis lupus). Animals 2020, 10, 607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liefländer, A.K.; Bogner, F.X. Educational impact on the relationship of environmental knowledge and attitudes. Environ. Educ. Res. 2016, 4, 611–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, T.; Dierkes, P. Evaluating Three Dimensions of Environmental Knowledge and Their Impact on Behaviour. Res. Sci. Educ. 2019, 49, 1347–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osuch, E.; Osuch, A.; Rybacki, P.; Przybylak, A.; Buchwald, T. Analysis of the factors influencing the decision about segregation by people not segregating the municipal waste with using the AHP method. J. Ecol. Eng. 2016, 17, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- American Psychological Association. Thesaurus of Psychological Index Terms, 9th ed.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kollmuss, A.; Agyeman, J. Mind the Gap: Why do people act environmentally and what are the barriers to pro-environmental behavior? Environ. Educ. Res. 2002, 8, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coelho, J.A.P.d.M.; Gouveia, V.V.; Milfont, T.L. Valores humanos como explicadores de atitudes ambientais e intenção de comportamento pró-ambiental. Psicol. Estud. 2006, 11, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heberlein, T.A. Navigating Environmental Attitudes. Conserv. Biol. 2012, 26, 583–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomažič, I. The influence of direct experience on students’ attitudes to, and knowledge about amphibians. Act. Biol. Slovenica 2008, 51, 39–49. [Google Scholar]

- Bogner, F.X.; Wiseman, M. Towards Measuring Adolescent Environmental Perception. Eur. Psychol. 1999, 4, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiseman, M.; Bogner, F.X. A higher-order model of ecological values and its relationship to personality. Pers. Individ. Differ. 2003, 34, 783–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Moura Carvalho, I.C. As transformações na esfera pública e a ação ecológica: Educação e política em tempos de educação e política em tempos de crise da modernidade. Rev. Bras. Educ. 2006, 11, 308–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bogner, F.X.; Wiseman, M. Adolescents’ attitudes towards nature and environment: Quantifying the 2-MEV model. Environmentalist 2006, 26, 247–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogner, F.X. Environmental Values (2-MEV) and Appreciation of Nature. Sustainability 2018, 10, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borchers, C.; Boesch, C.; Riedel, J.; Guilahoux, H.; Ouatarra, D.; Randler, C. Environmental Education in Côte d’Ivoire/West Africa: Extra-Curricular Primary School Teaching Shows Positive Impact on Environmental Knowledge and Attitudes. Int. J. Sci. Educ. Part B 2014, 4, 240–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B.; Manoli, C.C. The 2-MEV Scale in the United States: A Measure of Children’s Environmental Attitudes Based on the Theory of Ecological Attitude. J. Environ. Educ. 2011, 42, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binngießer, J.; Randler, C. Association of the Environmental Attitudes “Preservation” and “Utilization” with Pro-Animal Attitudes. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Educ. 2015, 10, 477–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingues, R.B.; Gonçalves, G. Assessing environmental attitudes in Portugal using a new short version of the Environmental Attitudes Inventory. Curr. Psychol. 2020, 39, 629–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneiderhan-Opel, J.; Bogner, F.X. Between Environmental Utilization and Protection: Adolescent Conceptions of Biodiversity. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahlström, M.; de Moor, J.; Uba, K.; Wennerhag, M.; De Vydt, M.; Almeida, P.; Baukloh, A.; Bertuzzi, N.; Chironi, D.; Churchill, B. Surveys of Participants in Fridays for Future Climate Protests on 20–28 September, 2019, in 19 Cities around the World; OSF: Charlottesville, VA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zomeren, M.; Postmes, T.; Spears, R. Toward an integrative social identity model of collective action: A quantitative research synthesis of three socio-psychological perspectives. Psychol. Bull. 2008, 134, 504–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brügger, A.; Gubler, M.; Steentjes, K.; Capstick, S.B. Social Identity and Risk Perception Explain Participation in the Swiss Youth Climate Strikes. Sustainability 2020, 12, 10605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielding, K.S.; Hornsey, M. A Social Identity Analysis of Climate Change and Environmental Attitudes and Behaviors: Insights and Opportunities. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielding, K.S.; Mcdonald, R.; Louis, W.R. Theory of planned behaviour, identity and intentions to engage in environmental activism. J. Environ. Psychol. 2008, 28, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thunberg, G. No One Is Too Small to Make a Difference, 1st ed.; Penguin Books: London, UK, 2019; pp. 1–106. [Google Scholar]

- Bogner, F.X. Einstellungen und Werte im empirischen Konstrukt des jugendlichen Natur- und Umweltschutzbewusstseins: Ein Handbuch für Lehramtsstudenten und Doktoranden. In Theorien in der Biologiedidaktischen Forschung, 1st ed.; Kruger, D., Vogt, H., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2007; Volume 1, pp. 221–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geiger, S.M.; Geiger, M.; Wilhelm, O. Environment-Specific vs. General Knowledge and Their Role in Pro-environmental Behavior. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heißel, A. Abschlussbericht zur Empirischen Erhebung der Einstellungen von Teilnehmenden Studierenden Einer Fridays-for-Future-Demonstration; Fachdidaktik II—Aktuelle Themen aus der Fachdidaktischen Forschung; Eberhard Karls Universität Tübingen: Tübingen, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Landis, J.; Koch, G. The Measurement of Observer Agreement for Categorical Data. Biometrics 1977, 33, 159–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schneller, A.J.; Johnson, B.; Bogner, F.X. Measuring children’s environmental attitudes and values in northwest Mexico: Validating a modified version of measures to test the Model of Ecological Values (2-MEV). Environ. Educ. Res. 2015, 21, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmona-Moya, B.; Calvo-Salguero, A.; Aguilar-Luzón, M.-d.-C. EIMECA: A Proposal for a Model of Environmental Collective Action. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddens, A. The Politics of Climate Change, 2nd ed.; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011; pp. 1–272. [Google Scholar]

- Marquardt, J. Fridays for Future‘s Disruptive Potential: An Inconvenient Youth Between Moderate and Radical Ideas. Front. Commun. 2020, 5, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randler, C.; Ballouard, J.M.; Bonnet, X.; Chandrakar, P.; Pati, A.K.; Medina-Jerez, W.; Pande, B.; Sahu, S. Attitudes Toward Animal Welfare Among Adolescents from Colombia, France, Germany, and India. Anthrophozoos 2021, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inglehart, R.; Welzel, C. Modernization, Cultural Change, and Democracy: The Human Development Sequence, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005; pp. 1–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, D.E. Contextual Effects on Environmental Attitudes and Behavior. Environ. Behav. 2001, 33, 708–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- List, M.K.; Schmidt, F.T.C.; Mundt, D.; Föste-Eggers, D. Still Green at Fifteen? Investigating Environmental Awareness of the PISA 2015 Population: Cross-National Differences and Correlates. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collado, S.; Rosa, C.D.; Corraliza, J.A. The Effect of a Nature-Based Environmental Education Program on Children’s Environmental Attitudes and Behaviors: A Randomized Experiment with Primary Schools. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelezny, L.C.; Chua, P.-P.; Aldrich, C. Elaborating on gender differences in environmentalism. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 443–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Román, C.; Lima, M.L.; Seoane, G.; Alzate, M.; Dono, M.; Sabucedo, J.-M. Testing Common Knowledge: Are Northern Europeans and Millennials More Concerned about the Environment? Sustainability 2021, 13, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiseman, M.; Wilson, G.; Bogner, F.X. Environmental Values and Authoritarianism. Psychol. Res. 2012, 2, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boeve-de Pauw, J.; Jacobs, K.; Van Petegem, P. Gender Differences in Environmental Values: An Issue of Measurement? Environ. Behav. 2014, 46, 373–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).