Abstract

A low-carbon policy attracts the interests of businesses, consumers, and policy makers. The purpose of this paper is to investigate how a carbon labelling scheme could be integrated into operational decision-making for manufacturers and retailers. Three game theoretic models of a supply chain with one manufacturer and one retailer are built to investigate a manufacturer and retailer’s pricing and investment decision for products with different initial carbon footprints considering consumer environmental awareness. Through a systematic comparison and numerical analysis, the results show that a carbon labelling scheme can significantly reduce the overall carbon emission supply chain and have an initially negative impact on the manufacturer and retailer’s profits. However, in the medium–long run, manufacturers and retailers could yet achieve profitability through continuously investing in low-carbon technology.

1. Introduction

With growing concerns over greenhouse gases (GHGs) and environmental pollution in recent years, many countries have enacted diverse legislations such as carbon taxes, carbon cap and trade programmes, environmental labelling, or eco-labelling schemes to help quell carbon dioxide (CO2) and other GHG emissions. In addition, with increasing consumers’ environmental awareness, many companies have started to develop and market products with climate-change credentials to achieve a competitive and commercial advantage. With those climate-change credentials on the products, consumers will be able to judge the impact on the environment of what they buy [1]. Firms whose products possess a credence attribute with a positive environmental benefit may have an incentive to disclose credence product attributes to achieve product differentiation and potentially increase sales [2]. As one type of eco-label, carbon labels on a product indicate the quantity of greenhouse gas emissions produced during the full life cycle of that product. These labels have been suggested as an effective means to not only encourage manufacturers to reduce CO2 emissions during the manufacturing process but also to lead the public towards low-carbon consumption to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and mitigate climate change. Therefore, carbon labelling schemes are garnering considerable focus.

Many internationally recognized carbon labelling schemes, most notably the CO2 Measured Label and the Reducing CO2 Label (UK), the Carbon Counted (Canada), the Carbon Free (US), and the Hong Kong Carbon Labelling Scheme (CLS), have been established in recent years [3], and these programmes are expanding globally [4]. First developed by British Carbon Trust in 2007, a carbon labelling scheme attempts to communicate relevant carbon footprint information not only to those sourcing organizations but also to consumers that will eventually contribute to the decision-making process inherent in product selection and purchasing [5]. The scheme also requires manufacturers to achieve low-carbon production in the next two years to further reduce the carbon footprint of the products [6].

The objective of carbon labels is to increase the transparency of the product carbon footprint and facilitate green consumption for consumers and sustainable production for manufacturers. Moreover, we also know that a carbon labelling scheme may help to reduce the carbon content during the manufacturing or logistic process before reaching the stores, encourage retailers and manufacturers to produce or sell fewer carbon-intensive products, and motivate customers to buy products with less embodied carbon [1]. In other words, this scheme is also an opportunity for organizations to publicly commit to reducing carbon in their products.

Growing consumer interest in “green products” has led many companies to manufacture and sell products with environmental attributes. Large retailers have begun to require their suppliers to clearly label the carbon footprint on their products [7,8]. For example, Walmart has requested its 100,000 suppliers to complete the carbon footprint verification for their products. Products without carbon labels will not be allowed to enter its procurement systems. Moreover, Walmart applied different colours of carbon labels on products to clearly grade their carbon footprints [9,10]. To be qualified for large retailers’ sourcing criteria and to achieve better carbon scores, many suppliers must consider investing in low-carbon production to reduce the product’s carbon footprint [11]. However, manufacturers may encounter higher operation costs due to the additional low-carbon investment. Certain manufacturers continue to use the scores as an important market opportunity and may pass the low-carbon investment costs on to consumers through retailers. Furthermore, the increasing price on the low-carbon products may reduce consumers’ purchasing intention [12,13,14].

In this paper, we develop models to support decision making concerning low-carbon production with consumers’ environmental awareness and a carbon labelling scheme. This paper provides a more thorough understanding of the impact of consumers’ environmental awareness on optimal pricing and profitability between manufacturer and retailer. In particular, we provide insights on the following research questions:

- (1)

- What is the impact of a carbon labelling scheme on the key decisions of supply chain players?

- (2)

- Considering consumers’ environmental awareness, is it profitable for a manufacturer to invest in low-carbon production?

- (3)

- If yes, how do the manufacturer and the retailer make decisions (the price and the product carbon footprint) for the carbon-labelled products?

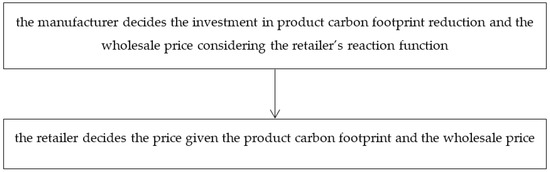

To answer the above questions, we consider a leader-follower Stackelberg game between one manufacturer and a retailer. Both sell a single product and attempt to achieve profit maximization in the market, where consumers are heterogeneous in their attitude towards low-carbon products. In this set up, the manufacturer and the retailer will both be affected by the carbon labelling scheme, and the manufacturer must decide if it will invest in low-carbon production to reduce the product carbon footprint. During this process, low-carbon investment costs will occur. To illustrate, Walmart as the retailer and Toshiba as the manufacturer are used as examples, where Walmart benefits from increasing the demand of environmentally sensitive consumers; however, Toshiba bears the greening cost [15]. Although this setup is considered for simplicity, the assumption enables one to understand the role of a carbon labelling scheme in the action of combating global climate change. To answer the research questions, we develop a manufacturer–retailer decision-making model where the manufacturer plays the role of Stackelberg leader, and the retailer is a follower in the supply chain. Both are independent decision makers and make their own decisions targeted at maximizing their individual profit. The sequence of decision making for the supply chain structure, illustrated in Figure 1, is as follows. Next, we will develop and analyse three different game models in three subsections, respectively.

Figure 1.

The sequence of decision making for the supply chain.

- (1)

- The decision-making model without considering a carbon labelling scheme (denoted Model NL);

- (2)

- The manufacturer is subject to a carbon labelling scheme (denoted Model LNR);

- (3)

- The manufacturer invests in carbon footprint reduction to mitigate the impact of a carbon labelling scheme (denoted Model LR).

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. A survey of related literature is presented in Section 2. Section 3 provides notations and assumption. The model development and analysis for the three game models are provided in Section 4. In Section 5, we compare the equilibrium results of the three models. To demonstrate the feasibility of the mathematical models, a numerical example is analysed in Section 6. We conclude our key findings in Section 7 and highlight possible future work.

2. Literature Review

Most scholars have studied carbon labelling from two perspectives: the impact of a carbon label scheme on consumer behaviour and the manufacturing decision under an environmental policy. The traditional economic models follow the utility maximization rule, in which rational consumers will make purchasing decisions considering constraints such as their personal financial situation if price and quality are consistent with the products’ utility function. An important assumption is that customers have full access to complete information about the products’ price and quality [16]. Consumers may be able to determine product quality attributes such as size and materials through observation. Products’ credence attributes are difficult to determine. The environmental quality attributes of a product are typically in the credence category. For example, consumers may not distinguish between production processes that have different environmental impacts when the final product is the same [17]. Thus, the role of a carbon label is to turn a credence attribute into a visible attribute so that consumers can easily compare and make more informed utility-maximizing product choice decisions [18]. In other words, the carbon labels will provide information to enable consumers to recognize the carbon emissions created during the production process and will thereby increase the environmental quality of the labelled goods [17]. In addition, recent research in behavioural economics shows that actors may care about behavioural utility in addition to economic benefits [19]. Hence, carbon labelling schemes may lead to social preference by customers and can be used to differentiate the low-carbon intensity products from normal ones. In sum, labelling may affect the implicit weights that consumers assign to the different product attributes and, in turn, affect consumer buying behaviour.

From a consumer’s perspective, various researchers examined consumers’ attitudes towards green or carbon-labelled products and a carbon labelling scheme [20,21,22]. It is claimed that the higher the consumers’ environmental preference, the more willing they are to pay higher prices for a low-carbon product [23]. Zhao and Zhong [24] examined consumers’ responses to carbon-labelled products adopting a system dynamics approach and found that public awareness, education level, critical premium, and perceived consumer effectiveness are the key factors that affect customer purchasing behaviour. Furthermore, Baddeley et al. [25] revealed that the acceptance of carbon labels depends mainly on the degree of consumer awareness and the credibility of the carbon labelling scheme. This revelation is echoed by Upham et al. [26] who conducted an experimental study and revealed that British consumers have a low willingness to use carbon labels as a reference when making a purchase. The main reason is that people found it difficult to understand labelled GHG emissions without additional information. Later, Schaefer and Blanke [27] proposed that an acceptable label must fulfil six requirements: completeness, transparency, reliability, clarity, availability/accessibility, and producer incentive. Tan et al. [7] also used a life cycle approach to explore the prospects of the carbon labelling of raw food products in Singapore and suggested that carbon footprint calculations must be standardized to avoid providing misleading information to policy makers, retailers, and consumers.

As consumers are the ultimate users of carbon-labelled products, their understanding of carbon labels and their willingness to pay for low-carbon products are key factors supporting a carbon labelling scheme. However, with mounting pressures from stakeholders and under more stringent regulations/legislations, emissions abatement has become an indispensable piece of manufacturers’ production operations which involve production planning and investment in pollution abatement equipment/systems [28]. The trade-off between environmental practices and profitability has been emphasized by many authors [29,30,31], who argue that environmentally friendly behaviour is not always compatible with the profit-seeking behaviour of the firm, such that the firm must balance the costs and benefits of environmental investments [32].

In recent years, an increasing number of scholars have investigated optimal production and pricing decisions under different emissions regulations, mainly focusing on carbon emission taxes and cap and trade, and found empirical evidence to support the claim that it is necessary for firms to consider carbon emissions in the design stage of manufacturing to reduce the impact of environmental policy towards their supply chain [33,34,35]. Benjaafar et al. [36] reviewed the papers published by INFORMS and found that operation research of the supply chain considering the emission factors remains in the early stage; there is a lack of systematic analysis in support of effective production decisions.

The idea of carbon labels would enable consumers to identify products with the smallest carbon footprints. Producers would then compete to reduce the carbon footprints of their products to benefit from environmentally sensitive consumer demand. However, improving low-carbon production often involves more elaborate manufacturing processes that increase the product’s manufacturing costs. To lower carbon footprints, firms may need to change their production location or invest in low-carbon manufacturing operations, which may lead to a change in their cost structure. Therefore, a systematic formulation for analysing cost effectiveness is needed. However, to the best of our knowledge, there is a lack of research to illustrate how manufacturers and retailers may be affected by carbon labelling schemes and how the price and profit structure may change if manufacturers make a low-carbon investment.

It can be observed that previous studies on carbon labelling mainly focused on either consumer attitudes towards carbon labels or the impacts of carbon labelling schemes on consumers’ purchasing behaviour using the methods of empirical studies, experimental studies, and surveys. Although a few studies [37,38,39,40] considered that the retailer price has an influence on consumers’ buying behaviour of carbon-labelled products, the manufacturer’s and retailer’s pricing strategies and the low-carbon investment decision have not been fully investigated yet.

Our research may be the first model-based paper that considers the impact of a carbon labelling scheme on the production and pricing decision. We conducted a quantitative economic analysis to examine the impact of a carbon labelling scheme on the manufacturer’s and retailer’s pricing strategies, the product carbon footprint decision, the consumer demand for the carbon-labelled products, the total carbon emissions, and their profits. We use a Stackelberg game [41,42,43] because it helps us to know the analytical expression of the manufacturing firm’s and the retailer’s optimal decisions, and the Stackelberg game has been widely used to study the decision-making behaviours in the supply chain [44,45,46]. As noted by Benjaafar et al. [36], the models-based research could be beneficial to understanding how accounting for carbon emissions may affect operational decisions across the supply chain. Our work’s objective is to contribute to the burgeoning literature on green supply chain decisions considering consumer environmental awareness.

3. Problem Notations and Assumption

In this paper, we focus on a two-echelon supply chain consisting of one manufacturer, denoted by M (referred to as “he”), and one retailer, denoted by R (referred to as “she”). The manufacturer produces only one product, and the retailer sells only the product produced by the manufacturer. Under a carbon labelling scheme, both the manufacturer and the retailer decide the optimal price and quantity to maximize the product’s expected profit, and the manufacturer must further decide if it will invest in green production to reduce the product’s carbon footprint. The assumptions in modelling are as follows:

Assumption 1.

For simplicity but without loss of information, we assume that the manufacturer plays the role of Stackelberg leader and the retailer is a follower in the supply chain. Both are independent decision makers and make their own decisions targeting the maximizing of their individual profit.

Assumption 2.

Under the carbon labelling scheme, the manufacturer attempts to reduce the initial product carbon footprint “” to a level “” () by adopting the cleaner technologies. The extra cost will incur, where “” represents an investment parameter that determines the magnitude of the cost involved in making an investment, which is similar to the study of Yalabik and Fairchild [32]. From the quadratic form, we note that the smaller the product carbon footprint (PCF) “” displayed on the product label, the more the manufacturer needs to invest in carbon reduction, which leads to extra production costs.

Assumption 3.

After a government has implemented carbon labelling scheme, the market demand for the carbon-labelled product with/without investment in carbon footprint reduction can be expressed byandrespectively, where “” represents the sensitivity of consumers to the product carbon footprint. Here, we can interpret “” as the consumer environmental-awareness level. We capture the impact of consumer environmental awareness and product carbon footprint on consumer demand in a tractable deterministic linear form. This form reflects that market demand will decrease as the product carbon footprint increases.

To develop the proposed models, we summarize the model parameters and decision variables in Table 1. The superscript * is used to indicate optimality whenever necessary. Additional notations will be provided when needed.

Table 1.

Symbols and notation.

4. Analytical Models

4.1. Manufacturer and Retailer Pricing Decisions without a Carbon Labelling Scheme (Model NL)

For the case without a carbon labelling scheme, the manufacturer determines the wholesale price “” and the retailer decides the retail price “” of the product. Hence, the profit functions of the manufacturer and retailer are:

The expressions are solved to derive the equilibrium values of decision variables.

Theorem 1.

In Model NL, the equilibrium wholesale price, the retail price, the market demand, the total carbon emissions, and the manufacturer’s and retailer’s profits are, respectively, given by:

, , , , , .

Proof.

See Appendix A. □

4.2. Manufacturer and Retailer’s Pricing Decisions with Carbon Labelling Scheme (Model LNR)

In this section, we consider the scenario where a government introduced a carbon labelling scheme, while the manufacturer does not make an investment in product carbon-footprint reduction and only displays the initial product carbon footprint “” on the product label. The manufacturer determines the wholesale price “”; the retailer decides the retail price “” of the product. The decision sequence is the same as that considered in Section 4.1 except that the initial product carbon footprint “” will affect the market demand. Therefore, to maximize the profits, the manufacturer’s and retailer’s decision problems can be formulated as follows:

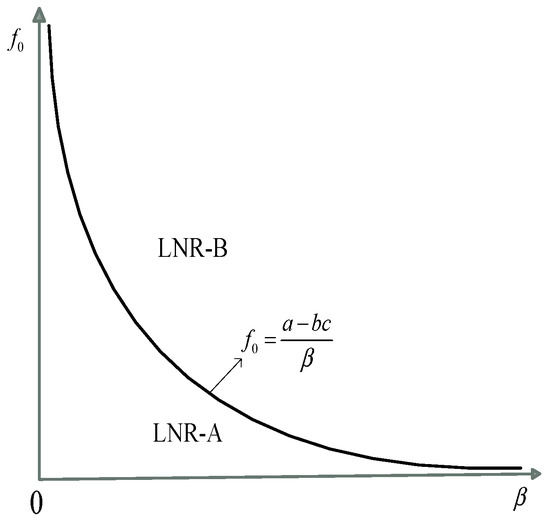

To obtain the manufacturer’s and retailer’s equilibrium decisions, we use backward induction and obtain Theorem 2, as follows. For simplicity, we divide the decision regions into two areas:

- (1)

- LNR-A (i.e., ),

- (2)

- LNR-B (i.e., ), which can be viewed as a function of “” and “” and is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. The decision regions for the chain members in the LNR model.

Figure 2. The decision regions for the chain members in the LNR model.

Theorem 2.

In Model LNR, the equilibrium wholesale price, the retail price, the market demand, the total carbon emissions, and the manufacturer’s and retailer’s profits are, respectively, given by:

- (1)

- In region LNR-A,,,,,,;

- (2)

- To ensure positive market demand, the initial product carbon footprint must satisfy. Therefore, in region LNR-B where, the market demand is zero, which means the supply chain members exit the market. This occurs because consumer environmental awareness is very high and the product with high initial carbon footprint will be rejected from the market.

Proof.

See Appendix A. □

From Theorem 2, with an increasing environmental consciousness, when the initial carbon footprint of the product is greater than a threshold value (), the market demand for these products declines quickly, even coming close to zero; then, the supply chain members exit the market in region LNR-B. Therefore, we only discuss the effects of consumers’ environmental awareness on the equilibrium wholesale price, the retail price, the market demand, the total carbon emissions, and the manufacturer’s and retailer’s profits in region LNR-A, and we obtain the following Corollary 1.

Corollary 1.

In region LNR-A,,,,,,.

Proof.

See Appendix A. □

Corollary 1 shows that, if the manufacturer does not make an investment in the product carbon-footprint reduction, with an increased consumer environmental awareness, both the manufacturer and the retailer should lower the wholesale price and retail price. The market demand, the total carbon emissions, the manufacturer’s and retailer’s profits will decrease in region LNR-A where the initial carbon footprint of the product is lower than a threshold value ().

4.3. Manufacturer and Retailer Pricing and PCF-Reduction Investment Decisions with a Carbon Labelling Scheme (Model LR)

Under this scenario, the manufacturer determines the product carbon footprint “” and wholesale price “,” and the retailer decides the retail price “” of the product. Hence, the manufacturer’s and the retailer’s decisions can be formulated as follows:

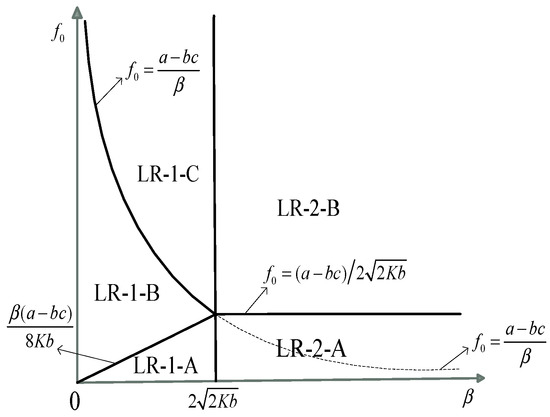

To obtain the manufacturer’s and retailer’s equilibrium decisions, we also use backward induction and obtain Proposition 3, as follows. For simplicity, we divide the decision regions into five parts:

- (1)

- LR-1-A (i.e., , ),

- (2)

- LR-1-B (i.e., , ),

- (3)

- LR-1-C (i.e., , ),

- (4)

- LR-2-A (i.e., , ), and

- (5)

- LR-2-B (i.e., , ), which can be viewed as a function of “” and “” and shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. The decision regions for the chain members in the LR model.

Figure 3. The decision regions for the chain members in the LR model.

Theorem 3.

In Model LR, the equilibrium wholesale price, the product carbon footprint, the retail price, the market demand, the total carbon emissions, and the manufacturer’s and retailer’s profits are, respectively, given by:

- (1)

- In region LR-1-A and region LR-2-A,,,,,,,;

- (2)

- In region LR-1-B,,,,,,,;

- (3)

- In region LR-1-C and region LR-2-B, the supply chain members exit the market.

Proof.

See Appendix A. □

According to Theorem 3, we note that the supply chain members’ equilibrium decisions in regions LR-1-A and LR-2-A are not influenced by consumer environmental awareness. The supply chain members exit the market because the market demand is negative in regions LR-1-C and LR-2-B. Therefore, we only discuss the impacts of consumer environmental awareness on the supply chain members’ equilibrium decisions in region LR-1-B and obtain the following Corollary 2.

Corollary 2.

In region LR-1-B,

- (1)

- Only when,,,,. Otherwise,,,,;

- (2)

- Only when,. Otherwise,;

- (3)

- Only when,. Otherwise,.

Proof.

See Appendix A. □

Corollary 2 shows that, if the manufacturer makes a PCF-reduction investment in region LR-1-B, both the manufacturer and the retailer should raise their prices with increased consumer environmental awareness when the initial product carbon footprint is relatively small (i.e., ); the market demand and retailer’s profits will consequently increase. However, when the initial product carbon footprint is relatively large (i.e., ), the manufacturer and retailer should lower their prices with an increased consumer environmental awareness; market demand and the retailer’s profits will consequently decrease. In addition, when the initial product carbon footprint is relatively small (i.e., ), the product carbon footprint will be reduced after the manufacturer makes a PCF-reduction investment. However, when the initial product carbon footprint is relatively large (i.e., ), the product carbon footprint will be increased after the manufacturer makes a PCF-reduction investment. When the initial product carbon footprint is relatively small (i.e., ), the manufacturer’s profits will increase. However, when the initial product carbon footprint is relatively large (i.e., ), the manufacturer’s profits will decrease with an increased consumer environmental awareness.

5. Comparisons of the Equilibrium Outcomes among the Three Models

In the previous section, we derived the equilibrium decisions for the supply chain members within the three game models considered in this paper. In this section, we will compare the equilibrium outcomes, the wholesale price, the retail price, the market demand, the total carbon emissions, and the manufacturer’s and retailer’s profits, and investigate what occurs after the government has implemented a carbon labelling scheme. Additionally, what changes occur if the manufacturer makes an investment in PCF-reduction under a carbon labelling scheme? New and interesting findings will be presented.

5.1. Model LNR vs. Model NL

First, we compare the equilibrium decisions between Model LNR and Model NL to identify what occurs after the government has implemented a carbon labelling scheme; however, the manufacturer does not make an investment in PCF-reduction.

Proposition 1.

Compared to Model NL, Model LNR yields

- (1)

- When,,,,,and;

- (2)

- When, the chain members exit the market.

Proof.

See Appendix A. □

Proposition 1 shows that, if the manufacturer does not make an investment in PCF-reduction under the carbon labelling scheme:

- (1)

- When the initial product carbon footprint is smaller than the threshold value (), the optimal wholesale price, the retail price, the market demand, the total carbon emissions, and the manufacturer’s and retailer’s profits are lower than those without a carbon labelling scheme.

- (2)

- When the initial product carbon footprint is larger than the threshold value (), the chain members exit the market.

5.2. Model LR vs. Model LNR

By comparing the equilibrium decisions between Model LR and Model LNR, we can identify what changes occur after the manufacturer makes an investment in PCF-reduction under a carbon labelling scheme.

Proposition 2.

Compared to Model LNR, Model LR yields

- (1)

- Whenand, orand,,,,,,;

- (2)

- Whenand,,,,①,,;Note ①: When,, otherwise.

- (3)

- Whenand, the chain members will not exit the market.

Proof.

See Appendix A. □

Proposition 2 shows that, under a carbon labelling scheme, if the manufacturer makes an investment in PCF-reduction:

- (1)

- When the initial product carbon footprint and the level of consumer environmental awareness are relatively small ( and ) or the initial product carbon footprint is relatively small () and the level of consumer environmental awareness is relatively high (), both the manufacturer and the retailer can raise their prices. The market demands and the manufacturer’s and retailer’s profits will be increased relative to the scenario without investment in PCF-reduction, and total carbon emissions will be reduced because of the manufacturer’s investment in PCF-reduction.

- (2)

- When the initial product carbon footprint is intermediate () and the level of consumer environmental awareness is relatively small (), both the manufacturer and the retailer can raise their prices. The market demand and the manufacturer’s and retailer’s profits will be increased relative to the situation without investment in PCF-reduction. When the initial product carbon footprint is relatively small, total carbon emissions will be reduced; otherwise, total carbon emissions will be increased.

- (3)

- When the level of consumers’ environmental awareness is relatively high () and the initial product carbon footprint is intermediate (), the chain members will not exit the market.

6. Numerical Examples

In this section, we present numerical examples to illustrate the theoretical results regarding the impacts of a carbon labelling scheme on the manufacturer’s and retailer’s equilibrium outcomes and investigate how consumers’ environmental awareness influences their optimal decisions, which is shown in Table 2. To confirm the feasibility of the proposed problem solution, we chose the parameter values based on the previous assumptions and constraints. Here, let , , , , and . Based on these parameters, the equilibrium wholesale price, the retail price, the market demand, the total carbon emissions, and the manufacturer’s and retailer’s profits in Model NL are obtained, i.e., , , , , and . All those values can be viewed as a benchmark to compare with the equilibrium outcomes in Model LNR and Model LR.

Table 2.

The equilibrium outcomes in Model LNR and Model LR.

From Table 2, we can obtain the following observations and insights:

- (1)

- In Model LNR (the manufacturer does not make an investment in PCF-reduction under a carbon labelling scheme), when the initial product carbon footprint or the level of consumer environmental awareness is relatively small (lower), the equilibrium wholesale price, the retail price, the market demand, the total carbon emissions, and the manufacturer’s and retailer’s profits will decrease with increasing consumer environmental awareness; otherwise, the chain members will exit the market.

- (2)

- In Model LR (the manufacturer makes an investment in PCF-reduction under a carbon labelling scheme), when the initial product carbon footprint is very small, the equilibrium wholesale price, the retail price, the market demand, and the retailer’s profits are the same as the equilibrium outcomes in Model NL (no carbon labelling). In addition, the product carbon footprint and the total carbon emissions are reduced to zero, and the manufacturer’s profit is reduced slightly owing to the investment in PCF-reduction; however, it is higher than that of Model NL. Interestingly, when the initial product carbon footprint is at the intermediate level and the level of consumer environmental awareness is very high, the equilibrium outcomes are the same as when the initial product carbon footprint is very small. More importantly, the chain members do not exit the market, in contrast to Model LNR. However, when the initial product carbon footprint and the level of consumer environmental awareness is very large (high), the chain members also exit the market.

- (3)

- Total carbon emissions in Model LNR and Model LNR are lower than that in Model NL, which means that total carbon emissions will decrease after the government implements the carbon labelling scheme, regardless of whether the manufacturer makes an investment in PCF-reduction.

- (4)

- Compared to Model NL, the manufacturer’s profit will surely decrease and the retailer’s profit may or may not decrease after the government implements the carbon labelling scheme.

7. Conclusions and Suggestions for Further Research

A carbon labelling scheme is often supported by businesses and/or government, and it attempts to guide consumers to purchase and use those products that have smaller carbon footprints. To explore the impacts of a carbon labelling scheme on the manufacturer’s and retailer’s optimal decision-making and its contribution towards carbon emissions reduction, this paper develops three decision models by applying game theory. This paper also derives certain equilibrium decisions for the supply chain under different levels of consumer environmental awareness. By analysing the influence of a carbon labelling scheme on the manufacturer’s and retailer’s optimal decisions, total carbon emissions and profits, and comparing these with the situation in which the manufacturer makes a PCF-reduction investment, we identify three main findings:

- (1)

- Regardless of whether or not the manufacturer makes an investment in PCF-reduction under the carbon labelling scheme, the total carbon emissions are lower than without the carbon labelling scheme. The conclusion may illustrate the role of a carbon labelling scheme in combating global climate change. Furthermore, the total carbon emissions are highly related to consumer environmental awareness.

- (2)

- Under a carbon labelling scheme, the manufacturer’s and retailer’s optimal decisions depend on two critical values (the initial product carbon footprint and the level of consumer environmental awareness). Given that the manufacturer makes an investment in PCF-reduction, when the initial product carbon footprint is very small, the product carbon footprint can be reduced to near zero, and the optimal pricing strategies can remain the same as the benchmark without a carbon labelling scheme. When the initial product carbon footprint is intermediate and the consumer environmental-awareness level is relatively low, both should also lower their prices. In addition, there is a threshold. When the initial product carbon footprint is smaller than the threshold, the product carbon footprint will decrease with increasing consumer environmental awareness, However, when the initial product carbon footprint is larger than the threshold (), the product carbon footprint will be increased with increasing consumer environmental awareness.

- (3)

- Under a carbon labelling scheme, the manufacturer’s profit is lower than without the carbon labelling scheme. In addition, the retailer’s profit under the carbon labelling scheme may remain unchanged or be lower than without the carbon labelling scheme; this will depend on whether the manufacturer makes an investment in PCF-reduction. This conclusion may explain why the voices of the retailers participating in carbon labelling schemes have been louder than those of the manufacturers in the years since carbon labelling schemes have been implemented.

We have made several contributions to the literature. First, our most significant contribution to the literature is that we have developed specific analytic expressions for two key decision variables under the carbon labelling scheme—pricing and the product carbon footprint—while considering the role of consumer environmental awareness. Second, this paper extends the PCF-reduction investment decision results of Yenipazarli [28] to a supply chain level where consumers’ environmental awareness is considered. Third, this paper enriches the experimental studies of Baddeley et al. [25] and Hartikainen et al. [39] regarding consumer purchase behaviour towards carbon labels. Specifically, in our paper, we have discussed the manufacturer’s and retailer’s pricing strategies for carbon-labelled products using the theoretical models and have provided a better interpretation of the important role of consumer environmental awareness in spurring the manufacturers to reduce carbon footprints under a carbon labelling scheme.

The paper also has practical implications. First, it is important to educate the public to increase environmental awareness and encourage them to purchase more low-carbon products to curb carbon emissions. In turn, the paper will also stimulate manufacturers to make investments in PCF-reduction and engage in more low-carbon production. Second, retailers should sell products with lower carbon footprints and strategically adjust the retail price of carbon-labelled products, such that they can make more profit by increasing consumer environmental awareness. In addition, the retailers should attempt to encourage the manufacturers to implement PCF-reduction strategies to achieve additional profits for both.

However, our work has certain limitations and can be extended in several directions. It is worth noting that the demand is assumed to be deterministic, and deterministic models do not consider the cost associated with supply and demand uncertainty. One future extension is to investigate the problem by using stochastic models. Another extension of our work can incorporate market competition, i.e., one supply chain competes with another supply chain. It will be interesting to explore how market competition would affect the manufacturers’ and retailers’ decisions and their performances under a carbon labelling scheme. Third, this paper focuses mainly on theoretical models and analysis. Empirical research could be developed in the future that would corroborate the results obtained from modelling and provide more valuable contributions to the literature in this area.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Humanities and Social Science Foundation of Chinese Ministry of Education (16YJC630012), the Key Project of Natural Science Research of Higher Education of Anhui Province (KJ2016A052), the Scientific Research Foundation for the Introduction of Talents of Anhui Polytechnic University (2015YQQ009) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (71671001).

Author Contributions

Yonghong Cheng and Hui Sun developed the model and conducted the analysis. Yonghong Cheng performed the research and wrote the paper. Fu Jia reviewed and edited the manuscript. Hui Sun and Lenny Koh revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Proof of Theorem 1.

In Model NL, we first solve for the retailer’s profit Function (2). According to and the first order condition, , we obtain the retailer’s price reaction function . □

Second, solving for the manufacturer’s profit Function (1), we substitute the value of into (1) and derive . According to and equating the first order condition to zero, that is , we obtain the manufacturer’s optimal price .

Substituting the value of into the value of , the optimal retail price is obtained as . From the above equilibrium values, we derive the market demand, the total carbon emissions, and the manufacturer’s and retailer’s profits.

Proof of Theorem 2.

In Model LNR, we first solve for the retailer’s profit Function (4). According to and equating the first order condition to zero, that is , we obtain . □

Second, solving for the manufacturer’s profit Function (3), we substitute the value of into (1) and derive . According to and equating the first order condition to zero, that is , we obtain the manufacturer’s optimal price . Substituting the value of into the value of , the optimal retail price is obtained as .

However, we note that . To ensure the market demand is positive, the initial product carbon footprint must satisfy . From the above equilibrium values, we derive the total carbon emissions and the manufacturer’s and retailer’s profits.

Proof of Corollary 1.

From Proposition 2 (1), taking the first order partial derivatives of the equilibrium outcomes with respect to , we have

, , ,

, ,

. Since , , . □

Proof of Theorem 3.

In Model LR, we first solve for the retailer’s profit Function (6). According to and equating the first order condition to zero, that is , we obtain . □

Second, solving for the manufacturer’s profit Function (5), we substitute the value of into (1) and derive .

According to and equating the first order condition to 0, that is , we obtain and substitute it into , then .

Taking the derivatives of the above with respect to , we obtain

and .

From the second derivative, we note when ; then can attain the maximum value at , that is .

However, when , then can attain the minimum value at and perhaps attain the maximum value at or .

Therefore, we consider the two cases separately:

- (1)

- When , to ensure , we obtain ; therefore, the optimal product carbon footprint . Substituting this equation into , we obtain the optimal wholesale price . Substituting both into , we obtain . If , that is , the optimal product carbon footprint , , and . If , that is , the optimal product carbon footprint . However, the market demand is negative under this condition; therefore, the chain members must exit the market.

- (2)

- When , if , then ; if , then . Furthermore, comparing the two profit functions, we note that ; therefore, can attain the maximum value at and when . Otherwise, the manufacturer’s profit is negative, and the chain members must exit the market.

Proof of Corollary 2.

From Proposition 3 (2), taking the first order partial derivatives of the equilibrium outcomes with respect to , we can obtain that

,

,

,

. □

From these equations, we note that, when , , , , ; otherwise, , , , .

In addition, we can obtain that . We find that, only if , then ; otherwise, .

Taking the first order partial derivatives of with respect to , we obtain that and note that, when , . Otherwise, .

Proof of Proposition 1.

Comparing Theorem 2 and Theorem 1, we have

,,,

, , and

. □

Since , we note that .

Thus, we have , .

Proof of Proposition 2.

Comparing proposition 3 and proposition 2, we have

- (1)

- , , ,, ,;

- (2)

- ,,,. □

It is easily shown that, when , ; otherwise, .

In addition, we can obtain , and .

References

- Boardman, B. Carbon labelling: Too complex or will it transform our buying? Significance 2008, 5, 168–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M.; Vandenbergh, M.P. The potential role of carbon labeling in a green economy. Energy Econ. 2012, 34, S53–S63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, P.; Feng, Y.; Pienaar, J.; Xiad, B. A review of benchmarking in carbon labelling schemes for building materials. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 109, 108–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeroen, C.; Berghab, V.; Truffer, B.; Kallis, G. Environmental innovation and societal transitions: Introduction and overview. Environ. Innov. Soc. Transit. 2011, 1, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Hornibrook, S.; May, C.; Fearne, A. Sustainable development and the consumer: Exploring the role of carbon labelling in retail supply chains. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2015, 24, 266–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Wang, Q.; Su, B. A review of carbon labeling: Standards, implementation, and impact. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 53, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, M.; Tan, R.; Khoo, H. Prospects of carbon labelling—A life cycle point of view. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 72, 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenton, P.; Edwards-Jones, G.; Jensen, M.F. Carbon labelling and low-income country exports: A review of the development issues. Dev. Policy Rev. 2009, 27, 243–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caro, F.; Corbett, C.J.; Tan, T.; Zuidwijk, R. Double counting in supply chain carbon footprinting. Manuf. Serv. Oper. Manag. 2013, 15, 545–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, J.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, L. Carbon emission reduction decisions in the retail-/dual-channel supply chain with consumers’ preference. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 141, 852–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N.M.P.; Allwood, J.M. Strategies to reduce the carbon footprint of consumer goods by influencing stakeholders. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 35, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnetas, A.; Ritchken, P. Option pricing with downward-sloping demand curves: The case of supply chain options. Manag. Sci. 2005, 51, 566–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajadieh, M.; Jokar, M. Optimizing shipment, ordering and pricing policies in a two-stage supply chain with price-sensitive demand. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2009, 45, 564–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, M.; Tang, W.; Zhang, J. Supply chain pricing and coordination with markdown strategy in the presence of conspicuous consumers. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2016, 23, 1051–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, D.; Shah, J. Supply chain analysis under green sensitive consumer demand and cost sharing contract. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 164, 319–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darby, M.R.; Karni, E. Free competition and the optimal amount of fraud. J. Law Econ. 1973, 16, 67–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hogan, L.; Thorpe, S. Issues in Food Miles and Carbon Labeling; Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics: Canberra, Australia, 2009.

- Karl, H.; Orwat, C. Economic aspects of environmental labeling. In The International Yearbook of Environmental and Resource Economics 1999/2000; Folmer, H., Tietenberg, T.H., Eds.; Edward Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Loch, C.; Wu, Y. Social preferences and supply chain performance: An experimental study. Manag. Sci. 2008, 54, 1835–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, W.; Hwang, K.; McDonald, S.; Oates, C.J. Sustainable consumption: Green consumer behavior when purchasing products. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 18, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blengini, G.; Shields, D. Green labels and sustainability reporting: Overview of the building products supply chain in Italy. Manag. Environ. Qual. 2010, 21, 77–493. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, C.; Zhou, S. Research advances in environmentally and socially sustainable operations. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2012, 223, 585–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanclay, J.; Shortiss, J.; Aulsebrook, S. Customer response to carbon labelling of groceries. J. Consum. Policy 2011, 34, 153–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Zhong, S. Carbon labelling influences on consumers’ behaviour: A system dynamics approach. Ecol. Indic. 2015, 51, 98–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baddeley, S.; Cheng, P.; Wolfe, R. Trade Policy Implications of Carbon Labels on Food; Canadian Agricultural Trade Policy and Competitiveness Research Network Commissioned Paper. Available online: https://ageconsearch.umn.edu/bitstream/122740/2/Commissioned%20Paper%202011-04%20Wolfe%20-%202.pdf (accessed on 16 April 2018).

- Upham, P.; Dendler, L.; Bleda, M. Carbon labelling of grocery products: Public perceptions and potential emissions reductions. J. Clean. Prod. 2011, 19, 348–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, F.; Michael, B. Opportunities and challenges of carbon footprint, climate or CO2 labelling for horticultural products. Erwerbs-Obstbau 2014, 56, 73–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yenipazarli, A. Managing new and remanufactured products to mitigate environmental damage under emissions regulation. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2016, 249, 117–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, K.; Oates, W.; Portney, P. Tightening environmental standards: The benefit-cost or the no-cost paradigm? J. Econ. Perspect. 1995, 9, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagell, M.; Wu, Z. Building a more complete theory of sustainable supply chain management using case studies of 10 exemplars. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2009, 45, 37–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, A.; Lenox, M. Exploring the locus of profitable pollution reduction. Manag. Sci. 2002, 48, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalabik, B.; Fairchild, R. Customer, regulatory, and competitive pressure as drivers of environmental innovation. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2011, 131, 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundarakani, B.; De Souza, R.; Goh, M.; Wagner, S.; Manikandan, S. Modeling carbon footprints across the supply chain. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2010, 128, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Klabjan, D. Optimal Emissions Reduction Investment under Greenhouse Gas Emissions Regulations; Working Paper; Northwestern University: Evanston, IL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, X.; Xia, H.; Zhu, H. Production decisions in a hybrid manufacturing–remanufacturing system with carbon cap and trade mechanism. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2015, 162, 160–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjaafar, S.; Li, Y.; Daskin, M. Carbon footprint and the management of supply chains: Insights from simple models. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2013, 10, 99–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Benjaafar, S.; Elomri, A. The carbon-constrained EOQ. Oper. Res. Lett. 2013, 41, 172–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guenther, M.; Saunders, C.; Tait, P. Carbon labeling and consumer attitudes. Carbon Manag. 2012, 3, 445–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartikainen, H.; Roininen, T.; Katajajuuri, J. Finnish consumer perceptions of carbon footprints and carbon labelling of food products. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 73, 285–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishino, N.; Akai, K.; Tamura, H. Product differentiation and consumer’s purchase decision-making under carbon footprint scheme. Procedia CIRP 2014, 16, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Leng, M.; Parlar, M. Game-theoretic analyses of decentralized assembly supply chains: Non-cooperative equilibria vs. coordination with cost-sharing contracts. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2010, 204, 96–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamali, M.; Rasti-Barzoki, M. A game theoretic approach for green and non-green product pricing in chain-to-chain competitive sustainable and regular dual-channel supply chains. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 170, 1029–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Zhu, J.; Jiao, H. Game-theoretical analysis for supply chain with consumer preference to low carbon. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2015, 53, 3753–3768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Zhang, X.; Meng, Q. Stackelberg games and multiple equilibrium behaviors on networks. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2007, 41, 841–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Zhao, Q.; Xi, M. A retailer-supplier supply chain model with trade credit default risk in a supplier-Stackelberg game. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2017, 112, 568–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, F.; Vasnani, N.; Pacio, L. A Stackelberg game in multi-period planning of make-to-order production system across the supply chain. J. Manuf. Syst. 2018, 46, 231–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).