Abstract

Addressing poverty is one of the United Nations’ Millennium Development Goals. Alleviating relative poverty by stimulating the endogenous motivation of poor people to improve their ability for self-proliferation and diffusion is the focus of attention worldwide. China, as the world’s most populous country, has already left absolute poverty, and the vast rural areas are facing the challenge of managing relative poverty. We use the Delphi method to select three representative cases from the typical cases of rural entrepreneurship published by the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, and describe the diffusion process and poverty reduction effect of returning farmers’ ‘entrepreneurship’ through the whole process analysis method. We found that the entrepreneurship diffusion model based on returning farmers has a bright future and great potential to improve rural poverty. Using family and local ties and the internet, returning farmers can effectively spread their entrepreneurial experience to other poor households, lowering their entrepreneurial risks and barriers, and thus collectively bringing more farmers out of poverty. The entrepreneurship diffusion of returning farmers can increase farmers’ income, promote the employment and entrepreneurship of poor households and improve the rural ecological environment, thus alleviating the multidimensional poverty of farmers in economic, social and ecological aspects. This provides an experience and reference for developing countries to solve the problems of poverty, especially poverty governance in rural areas. It is worth noting that implementing the diffusion of entrepreneurship among returning farmers requires the support of appropriate policies and the active participation of local governments.

1. Introduction

“Eradicating poverty in all its forms throughout the world” is the first of the 17 United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and this is the foundation for improving human wellbeing and narrowing the gap between rich and poor [1]. However, we are still far from achieving the goal of ending global poverty by 2030, and reductions in global poverty have been accompanied by political instability and local conflicts, economic marginalization, rural decline, natural disasters, climate change, backward production technology and other factors [2,3,4,5]. Accordingly, progress in reducing global poverty has been attributed to steady economic growth and the growth of wealth in many developing countries. China, the world’s most populous country, for example, has experienced rapid economic growth since its reform and opening up in 1978, which has led to a dramatic reduction in extreme poverty [6].

China has made some achievements in poverty governance but faces more challenges in the governance of relative poverty. According to the World Bank, at $1.90 per day, China has reduced poverty for more than 850 million people over the past 40 years, contributing more than 70% to global reductions in poverty, and has been the first developing country to achieve the UN’s poverty reduction target [7]. In this context, China has completed the historic elimination of absolute poverty, and needs to shift its poverty alleviation work to a “post-poverty reduction era” with a wider range of people, higher standards of poverty eradication and more sustained efforts [8]. However, China’s poverty eradication model is mostly government-led, and although this top-down “campaign-style” poverty alleviation action has accomplished political tasks in the short term, the relatively backward economic development of less developed regions has not fundamentally changed [9]. Poor areas still suffer from financial exclusion, a lack of capacity and a relatively high risk of re-entering poverty [10].

In recent years, China’s policy stance toward the countryside has activated rural resources, making it a unique trend in the Chinese social context for migrant workers to return home and start their own businesses. In developing countries, the growing number of self-employed in people the non-agricultural sector is a distinctive feature of many rural areas [11]. Migrant workers who return to their hometowns to start their own businesses are migrant workers who have been working outside their home area all year round for their own reasons and objective social reasons [12]. The data show that the number of Chinese migrant workers returning to their hometowns is 3.1 times higher than it was in the 1990s [13]. According to the statistics of the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, the number of migrant workers who have returned to their hometowns to start their own business is over 4.5 million, accounting for 68.5% of the total population of migrant workers engaged in entrepreneurial activities in their hometowns in rural areas [14]. In the current context of China’s development, there are various reasons why migrant workers return to their hometowns to start their own businesses [15]. On the one hand, advances in science and technology have led to higher demand for labor in urban development [16,17]. At the same time, there has been an increase in the level of consumption, making migrant workers in the city feel more pressure in terms of security, employment, resources and other aspects of life. On the other hand, migrant workers returning to their hometowns have certain resource advantages. Their entrepreneurial activities can help promote the combination of industrial and commercial capital and rural resources, and accelerate the two-way flow of production factors between urban and rural areas [18].

Migrant workers returning to their hometowns to start their own businesses have potential for solving the problem of relative poverty in China. Previous studies have pointed out that the poor can improve the success rate of their entrepreneurial endeavors by taking advantage of policies, introducing new technologies and catering to market demand, and small businesses in rural communities are a driver of poverty alleviation, job creation and resilience [19,20,21,22]. In China, the rising trend of migrant workers returning to their hometowns to start their own businesses has largely corrected the long-standing pattern of a one-way flow of quality capital from rural to urban areas, bringing better quality human capital, considerable material capital and relatively rich social capital to rural areas [23,24]. Meanwhile, returning farmers can drive talents, capital and other factors to return to the countryside; implement entrepreneurial behavior through family and geographical connections [25,26]; improve the level of regional human resources; and stimulate the endogenous power of poor groups to escape poverty. The return of labor to rural areas through entrepreneurship will create a “demographic dividend” in rural areas, which will drive the growth of employment and income of neighboring farmers through spillover effects [27] and alleviate relative poverty from economic, social and ecological perspectives.

Based on this, we propose to improve China’s relative poverty through the model of returning farmers entrepreneurship diffusion. On the one hand, the proposal of this model provides new ideas for research on relative poverty governance, which is conducive to enriching the theory of poverty governance. On the other hand, this poverty reduction model can provide new methods for countries with the same dilemma to actually solve relative poverty, and has good application value.

2. Background and Methods

2.1. Background

Absolute poverty lines reflect a fixed level of material welfare, while relative poverty is a concept that increases with a country’s economic development [28]. Townsend believed that relative poverty means not only the lack of the most basic means of living, but also the subjective psychological feeling of deprivation compared with the rest of society [29]. Relative poverty places more emphasis on the inequality of social development and is the poverty of people in comparison with the wealth of others. It no longer refers to basic needs but is relative to other groups [30]. This makes the alleviation of relative poverty more challenging than absolute poverty.

Defining relative poverty as a percentage of monetary income is the criterion currently adopted by most countries around the world. The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) proposed a poverty line of 50% or 60% of the median or average income of a country or region [31]; the World Bank defines members of society with incomes below one-third of the average income as relatively poor [32]; the EU has chosen 60% of the median income as the “threshold” [32]; Australia uses 50% of the median income as the annual poverty line [33]. Internationally, most countries or regions usually adopt a uniform relative income poverty line. However, a prominent problem in China’s economy and society is the unbalanced and insufficient development, which is mainly reflected in the large gap between the income levels of urban and rural areas and in the economic development of different regions [34,35]. Therefore, the option of dividing relative poverty groups by urban and rural areas and by regions (by provincial units) is needed [28]. Because the main problem we have addressed in this study is relative poverty in rural areas, considering the availability of the data, we chose 50% of the per capita disposable income of rural residents as the indicator of relative poverty in the economic dimension [36,37]. In addition, because relative poverty is multidimensional and dynamic, many scholars have also pointed out the need to reduce the sense of deprivation of the poor in multiple dimensions [38]. In addition to economic income, relative poverty also needs to consider social resources (employment opportunities, infrastructure and social security) and environmental resources (habitat) that individuals need to participate normally in community or social activities [39,40], largely because economic development is often accompanied by environmental destruction, depriving people of the right to enjoy a good ecological environment [41].

In the field of economics, the traditional strategy for governing relative poverty broadly consists of two dimensions. One is the strategy of development economics. In contrast to the vicious cycle of poverty in which a country is poor because it is poor [42], and the low-level equilibrium trap of Nelson [43], scholars have devised numerous government-led alternatives to break the low-level equilibrium trap through investment, including Schultz’s human capital theory [44], Rodan’s “Big Push” theory [45] and Rostow’s takeoff theory [46]. However, over the years, these strategies have not proven to be effective in generating economic growth in developing countries, let alone in solving the problem of relative poverty that arises from economic growth [44,45,46,47,48]. Relative poverty and shortage are not solely determined by resources and capital, but are closely related to mentality, culture, behavioral ability and incentives [49,50]. The second strategy is “trickle-down economics” [51], which is popular in mainstream economics. This doctrine is based on the market belief that the benefits received by the rich will eventually be passed on to the poor through trickle-down effects. Adequate market competition induces factor mobility due to the marginal diminution of factor rewards, and the equalization of factor returns will achieve regional equilibrium. The fruits of economic growth will eventually benefit ordinary workers and low-income groups [52,53]. However, because of the monopolistic nature of capital and the heterogeneity of capital and labor factors, the growth dividend created by market competition and its trickle-down effect can barely fill not only the wealth gap caused by the “capital divide” but also the income gap caused by the differences in labor ability [54]. Therefore, the trickle-down effect is not effective in alleviating the problem of relative poverty. It is clear that these two mainstream ideas have limitations in improving the ability of poor households to escape poverty.

Therefore, alleviating multidimensional poverty is more complicated and difficult than solving absolute poverty and we must find a way to alleviate relative poverty by relying on the ability of poor households themselves [55,56]. The concept of diffusion by returning farmers’ entrepreneurship may be a good schema. Rogers proposed the theory of the diffusion of innovation, which is a process of innovation diffusing through a medium that helps various members of a social system accept new ideas, products and services [57]. Entrepreneurial diffusion by returning farmers is a typical form of diffusion through innovation. After entrepreneurs have accumulated a certain amount of capital in the non-agricultural sector, they can help other poor people accept entrepreneurial ideas and implement entrepreneurial behaviors by means of their unique family and geopolitical ties, the internet and other high-quality entrepreneurial resources such as modern technology, business ideas and production methods [58]. Returning entrepreneurial farmers have family ties and local social networks that enable them to launch their businesses more easily than outside investors [59]. The forms of diffusion include centralized diffusion systems and non-centralized diffusion systems. A centralized diffusion system is fully controlled by the government and experts, and eventually spreads to the general population [60]. Decentralized diffusion of innovation comes from users and practitioners and the whole diffusion process is fully controlled by the general public, thus the decentralized diffusion system is more dynamic than the centralized diffusion system [57]. The model of returning farmers’ entrepreneurship belongs to the decentralized diffusion system, which alleviates relative poverty by acting on the endogenous and exogenous causes of relative poverty. First, from the perspective of the internal causes of relative poverty, the diffusion by returning farmers’ entrepreneurship not only broadens sustainable income channels of farmers and changes their negative attitudes towards market participation, but also creates a new platform for the dissemination of new technologies and ideas and injects vitality into the inclusive development of villages [61]. Second, from the perspective of the external causes of relative poverty, the proliferation of entrepreneurship among returning farmers will alleviate the social exclusion and self-exclusion triggered [62] by external factors causing poverty, such as policies and natural resources, and will contribute to the alleviation of multidimensional relative poverty. It can be seen that the diffusion of entrepreneurship among returning farmers is an important means of improving the endogenous ability of poor households to alleviate poverty.

2.2. Methods

We adopted the overall research approach in this study. In this approach, we can obtain more open information and learn more details about the case context and experience by describing the events in detail. This approach is suitable for in-depth dissection of the social phenomenon being studied in small amounts through actual observation [63,64]. More importantly, this approach not only answers broader and more complex questions, but also allows for the use of text, pictures and dialogue to convey a novel perspective [65].

The main goal of this study is to explore how the diffusion of entrepreneurship among returning farmers alleviates the problem of relative poverty. However, due to the large variability and complexity of relative poverty in rural areas, the implementation process and the effects of this model have not been systematically studied. We analyze three representative cases in China using an overall research approach. On the one hand, this approach allows us to draw general patterns by showing the various steps of the study in detail, which enhances the feasibility and rigor of the research process. On the other hand, we can use this approach to compare different cases horizontally and vertically to draw more realistic conclusions, which enhances the scientific accuracy of the research findings. Thus, it provides a new way of thinking for alleviating relative poverty.

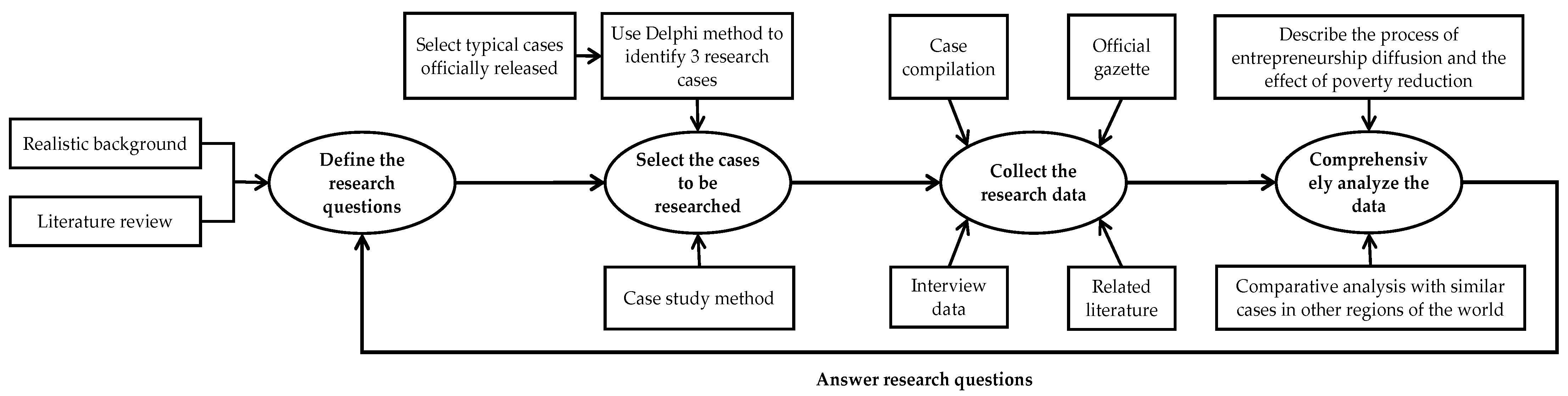

The steps of our study are as follows.

Step 1: Define the research questions. We asked the following two questions: (1) What type of entrepreneurship model has been used in China to alleviate relative poverty? Can it effectively stimulate the endogenous motivation of poor households instead of relying excessively on government policies? (2) How has this model succeeded in improving relative poverty under conditions that are free from overdependence on the government?

Step 2: Select the cases to be researched. To answer the research questions, we chose the case study approach because it is suitable for an in-depth study of socioeconomic phenomena with a fairly small number of observations. China is a vast country, and its geography, history and culture lead to different problems of poverty in various regions; therefore, different means of reducing poverty are needed [66]. China’s Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs announced the “2020 National Rural Entrepreneurship and Innovation Excellent Leaders Typical Case” [67] covering the vast rural areas of China in various types of farmers’ return home business diffusion classic stories; these cases highlight the representative entrepreneurs (cultural, technical, good innovation, management) and the leading role of entrepreneurial projects (appropriate technology, moderate scale, sustainable ecological environment and significant demonstration effect).

In order to select the most representative projects from these cases to analyze the internal logic of the entrepreneurial diffusion model to alleviate relative poverty, we use the Delphi method to consult experts in the research field. Finally, three typical entrepreneurial diffusion projects were selected: traditional planting case, diversified agriculture case and emerging industries case (represented by e-commerce entrepreneurship). These three projects cover the current industrial development characteristics of rural areas with different levels of development in China and all show that the entrepreneurial diffusion model can effectively alleviate relative poverty. In addition, according to the opinions of experts, we measure the poverty reduction effect of entrepreneurial diffusion model from three dimensions of economy, society and ecology, which will provide reference and enlightenment for relative poverty governance in other countries.

Step 3: Collect the research data. Our data mainly came from 4 aspects. The first part was the compilation of cases of outstanding rural entrepreneurship and innovation leaders in 2020, which were our basic data. The second part was the government gazette of each province and city, which mainly included the macro data involved in the cases. The third part was the team’s field interviews, which helped us grasp the research process more accurately. The fourth part was the reference literature, which was mainly for case three.

Step 4: Comprehensively analyze the data. Based on the research data and the background, we described 3 important aspects of the 3 cases, namely the context in which they are located, the entrepreneurial diffusion process and the effect of poverty reduction; we also summarized the general conclusions. In addition, we selected cases from other parts of the world that are similar to the results of this study. These cases cover both developing and developed countries and also show that entrepreneurial diffusion is conducive to alleviating relative poverty in rural areas. We hope to illustrate the feasibility and potential of the model described in this study by comparing it with similar cases in other parts of the world.

The research procedure is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Research Steps.

3. Diffusion of Returning Farmers’ Entrepreneurship: The Dawn of Relative Poverty Governance in China

The diffusion of returning farmers’ entrepreneurship can help alleviate the poverty of farmers within economic, social and ecological dimensions. Firstly, entrepreneurship diffusion can help more poor people accumulate capital and ensure the sustainable livelihoods of farmers, thus reducing the risk of returning to poverty due to economic income shocks, which have a significant effect on the alleviation of the economic dimension of poverty in farmers [68]. Secondly, entrepreneurship diffusion can drive the poor to take the initiative in employment and entrepreneurship, motivate them to participate in the market and enhance the employment absorption capacity of rural areas [69,70,71], which has a significant effect on the social development dimension of alleviating poverty in farming households. Finally, returning farmers, influenced by advanced urban concepts, are more likely to have the concept of green development, which will also be transmitted to other farmers through entrepreneurial diffusion, leading most entrepreneurs to pursue a better living environment and take responsibility for protecting the ecological environment in rural areas, which helps rural areas achieve sustainable development goals [72] and has a significant effect on alleviating poverty in the ecological and environment dimensions of farming households.

3.1. Entrepreneurial Diffusion in Traditional Agriculture: Family Ties

Luojiashan Village [67] in Shanxi Province is located in the central region of China and is among the extremely poor villages of Lin County, a very poor county, with an average annual income of less than CNY3000 per person in the village before 2017. The natural conditions of Luojiashan Village are suitable for traditional farming (mainly red dates), but it is limited by the rough operations of small farmers (small scale and weak organization), with low and unstable economic benefits and serious poverty problems. In recent years, the provincial government of Shanxi has guided migrant workers to actively participate in the construction of their hometowns, and has supported them through business subsidies and technical training in an attempt to help poor households improve their ability to lift themselves out of poverty through a model driven by returning entrepreneurs.

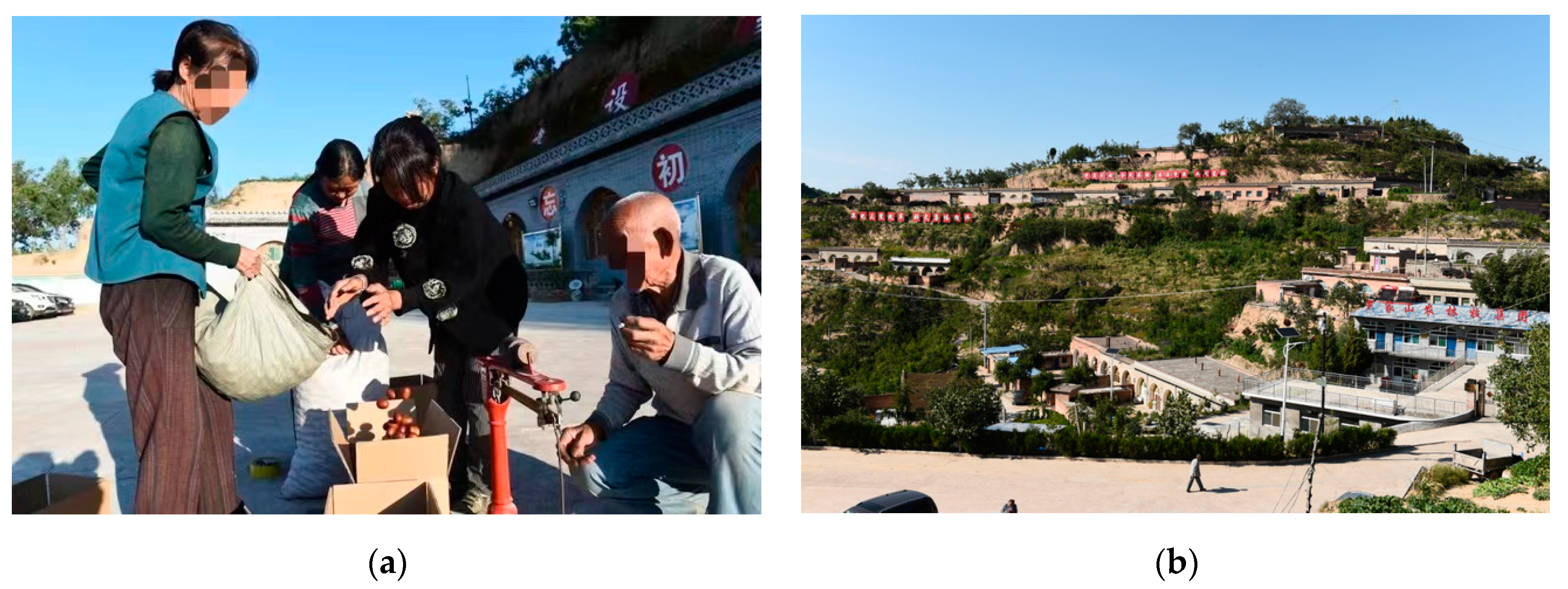

In 2017, Z, a returned entrepreneurial farmer from Luojiashan Village, started his entrepreneurial activities in his hometown. The entrepreneurial farmer chose the jujube industry as an entry point to lead the villagers to wealth and rural revitalization based on the resource endowments of the countryside. The villagers in this village have lived in the same geographical environment for generations and they are related to each other by kinship ties, forming a social network of “acquaintances”, which is an effective vehicle for entrepreneurial diffusion. First, Entrepreneurial Farmer Z took the lead in establishing the Luojiashan Jujube Professional Cooperative with his family and relatives and called on 99% of the villagers to invest in their land contracting rights, giving them the right to share in the profits to increase the income from their properties. Secondly, under the leadership of the cooperative, the villagers implemented the management of 600 mu of jujube trees and established a unified system. The quality and quantity of jujubes was guaranteed, which increased the villagers’ family business income. In addition, the cooperative signed a purchase and sale contract with a local agricultural company and solved the marketing problem through the “company + cooperative” model (As shown in Figure 2a). Finally, through stable development of the planting industry, the villagers joined the agricultural product processing industry on their own initiative. Through investment, they established a cold storage facility, an organic fertilizer factory and Luojiashan’s breeding base, and established Shanxi Luojiashan Food Technology Co. With the guidance of the government, driven by returning entrepreneurial farmers and operated by cooperatives, the entrepreneurial activities of Luojiashan Village in the field of traditional agriculture developed towards the trend of crop specialization, which greatly improved the economic benefits [73]. The village’s per capita disposable income reached CNY8000 in 2020 [14], exceeding the relative poverty line of Shanxi Province (50% of the per capita disposable income of rural residents in Shanxi Province in 2020 as the standard line, i.e., CNY6939 [74]). In the past 3 years, 56 poor households in the village have been employed. In 2019, a cooperative canteen was established to provide free meals to all village residents over 70 years old. The cooperative raised CNY10 million to open and green 3.6 km of the roads out of the mountains, widen and green one kilometer of the main street in the village and improve the level of construction of infrastructure (As shown in Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

Entrepreneurial activities in traditional agriculture: (a) Farmers selling red dates; (b) Village roads hardened. Note: (a,b) from Living Morning News Datong: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1679058782975100260 (accessed on 15 June 2022).

This kind of entrepreneurial activity in traditional agriculture, linked by family ties, is suitable for diffusion in small areas (villages), mainly through cooperative business models to increase crop specialization and thus solve the problem of relative poverty in rural areas. In this type of diffusion, the cooperatives run by returning farmers activate rural land resources for local farmers and solve the problem of arable land fragmentation. At the same time, the “cooperative + enterprise” model effectively solved the issue of marketing agricultural products and provided villagers with more employment opportunities and wage income. Furthermore, the strong kinship ties among villagers, thanks to the rural clustering and the survival of generations of neighbors, contributed to the spread of the benefits of entrepreneurship.

3.2. Entrepreneurial Diffusion in Diversified Agriculture: The Dual Connection of Family Ties and Geography

Tianjiazhai Town [67], Xining City, Qinghai Province, located in the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau region, is a typical poverty-stricken region in western China. In 2015, 28 poverty-stricken villages (22 key poverty-stricken villages and 6 general poverty-stricken villages) were registered in Tianjiazhai Town. The region has experienced a serious loss of the young and strong labor force, and it is difficult to alleviate the poverty of farm households whose main source of income is traditional agricultural production.

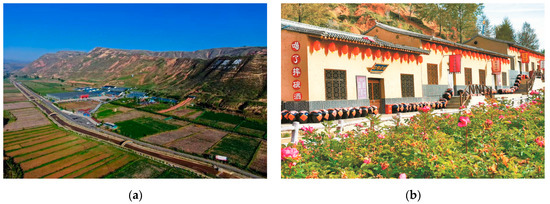

As a resident of the town, W, a returned entrepreneurial farmer, is leading a joint venture with poor households by developing diversified agriculture and rural tourism. Influenced by the traditional Chinese rural society based on “human relationships”, Entrepreneurial Farmer W expects to solve the problem of poor households having only a single way to increase their income through farming, breeding and working outside the home. First, he called on several friends and relatives to establish the “Qian Ziyuan Agricultural Science and Technology Expo” through the connections of family ties. According to the soil conditions and climate conditions in Qinghai Province, they introduced the characteristic industry of the saline production of fruitless Chinese wolfberry bud tea, as well as the development of planting and tourism as part of a science and technology park. After determining the characteristic industry, Entrepreneurial Farmer W began to use the geopolitical advantages to call on neighboring villagers to join in the production and construction of Qian Ziyuan, mainly for planting and cultivation of the park, to help these villagers earn a wage income. Further, in order to strengthen the characteristic brand, Qian Ziyuan introduced “space crop” flower seeds and launched the only “Space Plant Expo” in Qinghai [75]. As the economic benefits brought by Qian Ziyuan were seen by more poor farmers in town, they began to take the initiative to join the processing industry and tourism industry, in addition to plant cultivation, and to gain more economic income by imitating the entrepreneurial behavior. According to statistics, the development of Qian Ziyuan has led to the creation of a total of six professional cooperatives and three entrepreneurial enterprises for college students in the town, while more than 30 farmers operate businesses in the areas of catering, contract farming, agricultural product insurance, service management, etc. [76]. In 2020, the per capita disposable income of entrepreneurial farmers in Tianjiazhai Town reached CNY15,000, far exceeding the relative poverty standard of Qinghai Province (according to the figures for 2020 in Qinghai Province, 50% of the per capita disposable income of rural residents, as the standard line, was CNY6171 [77]). It inspired 721 households with 2203 poor people from 28 poor villages in Tianjiazhai Township to start their own business [78]. With the growth of the collective economy, Tianjiazhai built a cultural square and raised funds for 660 solar streetlights. It also relocated 80 households and 227 people in areas prone to geological disasters to Donghe New Village to ensure their housing safety. Moreover, 1200 mu of wasteland and saline land have been transferred and improved to become a leisure resort park with economic, social and ecological benefits (As shown in Figure 3a).

Figure 3.

Entrepreneurial activities in the field of diversified agriculture: (a) Improved ecological environment in Tianjiazhai town; (b) Hotels built by poor households for leisure tourism. Note: (a) from Qinghai Daily: http://www.qhio.gov.cn/system/2020/12/09/013299214.html (accessed on 8 August 2022); (b) from Qinghai Daily: https://epaper.tibet3.com/qhrb/html/202206/02/content_97061.html (accessed on 8 August 2022).

With scientific and technological innovation as the goal, through the promotion of agricultural diversification and the entrepreneurial schema driven by returning farmers, Tianjiazhai Town has built an advantageous industrial system of complex fields based on modern agriculture, preservation of agricultural products, processing and logistics as the key, with leisure agriculture and rural tourism as the core, relying on the characteristic industrial advantages of Qian Ziyuan. The cooperative coordinated and promoted the integration and interaction of agroecological industrialized planting, production and processing, scientific research, rural tourism, culture, health and other industries to alleviate poverty (As shown in Figure 3b). Compared with the ability of family relationships to drive farmers to start a business, the advantage of geopolitical links is that they can drive a broader area, allowing cooperation with others in seeding, production and sales, and in developing industry clusters while reducing transaction costs.

3.3. Entrepreneurial Diffusion in Rural E-Commerce: The Breakthrough of the Internet

Lingshan County [67] in Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region is a place where China’s ethnic minorities gather, and the complex culture of ethnic minorities makes it difficult for poor households to increase their income. In recent years, the government of Lingshan County has vigorously developed the “e-commerce poverty alleviation” model, calling on farmers to use the internet to share about their rural life, sell special agricultural products and showcase different ethnic cultures.

Entrepreneurial Farmer G is an ordinary ethnic minority woman from Lingshan County, Guangxi, who started a rural e-commerce business in her hometown in response to the policy call and to take care of her son. Firstly, with the help of her nephew, who has filming skills, she set up the “Qiao Fu Jiu Mei” e-commerce team with her husband and other family members, and insisted on uploading videos of agricultural products on live media every day to share the details of her traditional rural life and rural cuisine (As shown in Figure 4a). This model of using family members as the main business partners reduced management costs. In less than a year, the number of her fans exceeded 2 million. Next, the Qiao Fu Jiu Mei e-commerce team initiated the e-commerce mode of selling agricultural products through Netflix Live. Through the method of geographic links, the team drove nearby villagers to join the business team in areas such as filming, customer service, commenting and replying, e-commerce delivery and packing, etc., which increased the wage income of poor households. As the benefits of live e-commerce continue to emerge, Entrepreneurial Farmer G began to actively guide other farmers to use e-commerce sales of agricultural products in order to realize their self-worth. She cooperated with Lingshan TianYu E-commerce Co. Ltd. to carry out e-commerce training for poor households, mainly teaching skills such as video shooting and live streaming with goods (As shown in Figure 4b), with a total of more than 100 trainees, hoping to make live streaming into a new farming activity. In addition, the Qiao Fu Jiu Mei team cooperated with various fruit planting cooperatives and other professional cooperatives, using the internet for sales to overcome the problems previously faced by farmers, such as price pressures and agricultural product stagnation. In recent years, Qiao Fu Jiu Mei has made use of online live appeals to actively explore the “net red economy + consumption poverty alleviation” model, to develop and grow e-business industries to alleviate poverty industry, to drive people to increase their income and to inject fresh vitality into alleviating consumption poverty.

Figure 4.

Rural e-commerce entrepreneurship: (a) Entrepreneur G sells through live e-commerce; (b) Entrepreneur G trains other farmers in e-commerce. Note: (a) from China Women’s Daily: https://new.qq.com/rain/a/20200506A0OWLZ00 (accessed on 10 August 2022); (b) from Guangxi Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region Department of Agriculture and Rural Development: http://nynct.gxzf.gov.cn/xwdt/gxlb/gx/t10993633.shtml (accessed on 24 August 2022).

With the global rise of e-commerce, the role of the internet in reducing poverty has gradually come to the fore. This internet-based rural e-commerce entrepreneurship schema breaks the traditional diffusion path of family and geographical ties and expands the radiation range of entrepreneurial diffusion. The e-commerce business driven by Entrepreneur G has given impetus to the county’s sales chain of agricultural products and has driven a combined online and offline sales model of agricultural products. More than 30,000 poor people have benefited from this program, and they are engaged in e-commerce operations, after-sales services, logistics, docking and packing and express delivery [79]. Since 2017, the cumulative sales of Lingshan County’s e-commerce industry for alleviating poverty have reached CNY3.58 billion. This poverty alleviation model has driven 121 poor villages to develop special poverty alleviation industries, and the livelihood of 63,000 poor people has been secured, with an average increase in annual income of CNY2680 per household [80]. Driven by the diffusion of entrepreneurship, the per capita disposable income of rural residents reached CNY14,108, exceeding the relative poverty standard of Qinghai Province (50% of the per capita disposable income in 2020, i.e., CNY7407 [81]). Driven by Qiao Fu Jiu Mei’s live e-commerce broadcasts, the government of Lingshan County has vigorously developed the “Internet+” poverty alleviation model and has set up cold storage and insurance facilities, logistics enterprises and deep processing enterprises in the main production areas of agricultural products to improve and protect the infrastructure of rural e-commerce. From a national perspective, as of December 2020, China’s rural internet users numbered 309 million and the internet penetration rate in rural areas was 55.9%. In this context, there is huge space for the growth of rural internet users as UGC (user original content) producers.

4. Discussion

4.1. How Entrepreneurship Diffusion Promotes Improvements in Relative Poverty

In the context of this study, we focused on alleviating relative poverty by improving the self-development capacity of poor households. The effective reduction in relative poverty is not only reflected in income level above the relative poverty line but also in the reduction in deprivation felt by poor households in terms of their social life and ecological environment [82], or an increase in their sense of gain. Guided by equality and equity, poor households are feeling more benefits in all aspects, and the gap between them and other groups is narrowing [83,84,85,86]. Policymakers must choose appropriate means to improve the ability of local poor households in terms of self-proliferation and differentiation, and consider the socio-economic characteristics of the management area and factors such as poor households’ education level [28]. It is necessary to understand the natural and human characteristics of the environment before analyzing the root causes of social and economic problems.

In China, as in many developing countries in the world, the low degree of mechanization in traditional agriculture makes small farmers more interdependent and creates a good spirit of cooperation [87]. Most small farmers live together on a small scale, increasing the emotional interactions among them. Therefore, returning farmers’ entrepreneurship is very suitable for the rural ‘acquaintance society’ and cultural customs linked [88,89] by family ties and geography, and it is easier to drive other farmers’ entrepreneurial behavior through these connections.

We made a comparative analysis of the entrepreneurial diffusion factors and the poverty-reducing effects of the three cases (as shown in Table 1 and Table 2).

Firstly, we found that entrepreneurial farmers, government and related enterprises jointly promoted the growth in entrepreneurship [90]. As the first, or first batch of, entrepreneurial farmers, returning entrepreneurial farmers have a huge demonstration effect. Because of people living together day and night, this entrepreneurial model can be quickly emulated by the surrounding poor households. Those who start businesses later can obtain the support of farmers in terms of technology, marketing and other aspects, thus actively extending the industrial chain and greatly reducing the cost of entrepreneurship [91]. In addition, the government’s participation in farmers’ entrepreneurship in various forms is a major feature of China [92]. The government has issued various preferential policies for entrepreneurship, calling on the labor force to return home to start businesses. After completing the primary cultivation of entrepreneurial projects after returning home to start a business, entrepreneurial farmers are encouraged to actively carry out entrepreneurial diffusion to drive more poor households to start a business. Unlike the stage of solving absolute poverty, the government mainly provides support in the form of technology, capital, tax and other aspects to encourage entrepreneurial leaders to play a leading role, rather than direct assistance. In addition, enterprises promote the development of entrepreneurial diffusion. For a long time, limited by education, capital and experience, the greatest bottleneck in farmers’ entrepreneurship was the construction of market channels. Enterprises or cooperatives can make a difference in the area of market channels and can help farmers build market confidence by means of cooperation, such as in the ‘company + farmer’ model. This leads to imitation by subsequent entrepreneurial farmers and ultimately to the formation of entrepreneurial industry clusters.

Secondly, we found that the patterns of entrepreneurial diffusion were different in different entrepreneurial fields, which further affected the scope and coverage of diffusion. In the field of traditional planting, entrepreneurial projects mainly develop a cooperative economy through family connections and tend to cooperate with close family members to improve the ability of poor households to reduce market risks [93]. This diffusion model has a small geographical range of radiation, mainly within the basic unit of a village. Geographic relationships (neighborhoods and fellowship), to a certain extent, transcend regional restrictions between villages and can help expand the scope to larger areas, such as townships, and drive more people to participate [94]. The use of internet technologies can break the restrictions of kinship and geography. Even if poor households and entrepreneurial leaders have no kinship ties or close geographical relationships, they can also participate in entrepreneurial activities through the internet, which can radiate to a wider range [95].

Finally, our three cases confirmed that entrepreneurial diffusion has a good effect on reducing relative poverty. In the dimension of economic benefits, we referred to the relative poverty line of China and each province in 2020 as the standard. The results show that the followers of the entrepreneurs have exceeded the relative poverty line of each province in terms of income, but in the traditional planting industry where kinship ties were the main diffusion method, they have not exceeded the national relative poverty line, as occurred in the other two cases. This may be limited by the short industrial chain. In addition, the entrepreneurial diffusion of returning farmers has effectively improved the employment rate and social security level of the regional population. The degree of development of infrastructure and the protection of the ecological environment increased with the needs of industrial development and improvement in the collective economic level. Therefore, this model has both social and ecological benefits for alleviating relative poverty.

Table 1.

Comparative Analysis of the Elements of Entrepreneurial Diffusion of Three Cases.

Table 1.

Comparative Analysis of the Elements of Entrepreneurial Diffusion of Three Cases.

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elements of entrepreneurial diffusion | Industry | Traditional planting industry | Diversified agriculture industry | Rural e-commerce industry |

| Reasons for returning | Policy guidance, local complex, getting rid of the plight of urban employment | Policy guidance, local complex, needs of realizing self-worth | Policy guidance, local complex, family responsibility | |

| Main participants | Returning hometown entrepreneurial farmers, government, cooperatives, enterprises | Returning hometown entrepreneurial farmers, government, enterprises | Returning hometown entrepreneurial farmers, government, enterprises | |

| Diffusion mode | Family connection | Family connections, geographic connections | Family connections, geographic connections, internet connections | |

| Driving scope | Village scope | Town scope | County scope | |

Table 2.

Comparative Analysis of Poverty Reduction Effects of three cases.

Table 2.

Comparative Analysis of Poverty Reduction Effects of three cases.

| Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before | After | Before | After | Before | After | ||

| The effect of poverty reduction | Income (the relative poverty standard of China is CNY8565 [96]) | The relative poverty standard in Shanxi Province is CNY6939 | Average disposable income is CNY8000 | The relative poverty standard in Shanxi Province is CNY6171 | Average disposable income is CNY15000 | The relative poverty standard in Shanxi Province is CNY7407.5 | Average disposable income is CNY14,108 |

| Employment | Mainly engaged in unstable agricultural production | The employment and entrepreneurship of 56 people in the village | Mainly engaged in unstable agricultural production and unstable basic work in cities | The employment and entrepreneurship of 2203 poverty populations in the village | Mainly engaged in the unstable fruit industry and urban labor activities, facing unemployment at any time | The employment and entrepreneurship of more than 30,000 people in the county | |

| Social security | Government-led social assistance projects to meet basic survival needs. Relying on the ‘family pension’ | Poor households have the financial ability to buy all kinds of commercial insurance. The village co-founded a pensioner canteen with the cooperative | Government-led social assistance. Migrant workers have no insurance in urban and rural areas. Poor housing conditions for poor households | Poor households have the financial ability to buy all kinds of commercial insurance. Relocation of 227 people for alleviating poverty and improving their living conditions | Basic pension insurance and basic medical insurance, which are quite different from those of urban residents, and the amount is not high | Government subsidies for entrepreneurship and employment. Increased pension insurance | |

| Infrastructural development | There was no road out of the mountain Lack of a water supply and heating in the village Lack of communication equipment | Hardened 3.6 km of mountain road Built a cultural square Improved water, electricity, heating, and communication facilities | Most villages in the town had not built streetlights There was no market for daily shopping | Built a cultural square. Installed solar streetlights A new integrated market has been established | Weak information infrastructure Lack of logistics points | Improved construction of infrastructure in the main production areas of agricultural products. Added more logistics points. | |

| Ecological environment | Dirty, messy and poor living environment | Greened 1000 m of the village’s main street and establishment of the Environmental Sanitation Management Leading Group | The ecological environment of the saline-alkaline land is harsh and crops could be planted | The saline-alkali land became a leisure resort after improvement, which improved the local ecological environment | Land quality had been damaged by traditional production methods with high use of fertilizers and pesticides | Adopted low-carbon technologies to produce fruits, tea, and other crops, reducing environmental pollution | |

4.2. Similarities and Differences between Our Case and Similar Projects in Other Regions of the World

Many countries or regions in the world are also aware of the potential to alleviate poverty in rural areas through entrepreneurial diffusion. In this section, we selected the Republic of Uganda, the Republic of Cameroon, the United States, the Philippines and other countries with different political backgrounds for analysis, and found that the farmer-to-farmer model and the “youth into the countryside” model have the same underlying logic as the return of Chinese migrant workers.

The model of farmer-to-farmer entrepreneurship has been adopted by many countries. For example, due to the scarcity of resources, many farmers in the Republic of Uganda began entrepreneurial bricolage. Its entrepreneurial purpose is similar to that of Chinese farmers, that is, to eliminate poverty and improve people’s welfare. Entrepreneurial agriculture in the Republic of Uganda also faces the problem of weak protection against risk and insufficient resources. However, farmers with a rich educational background who are younger are usually good agricultural managers and can be used as an example for dealing with agricultural products. They can obtain cheap human resources [97], are good at identifying target market segments and can introduce improved seed and fertilizer technologies. Their entrepreneurial behavior is profitable, which is highly consistent with the characteristics of returning entrepreneurial farmers in China. The difference is that most of the skills of these Ugandans are acquired through informal learning and experience. They rely on the government, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and agricultural technology extension personnel to improve their entrepreneurial ability and all have benefited from different training programs [98]. However, Chinese entrepreneurial farmers returning home have mainly improved their entrepreneurial ability through work experience, but have also responded to entrepreneurial policies to reduce entrepreneurial resistance [99]. Both returning farmers in China and farmers in Uganda have taught planting techniques, management experience and market information to other small farmers who have not yet escaped poverty, helping them improve their ability for self-proliferation and differentiation, and eliminating poverty through reducing dependence on the government and informal organizations. The same development model has also been demonstrated in the Republic of Cameroon. The Republic of Cameroon has implemented farmer-to-farmer extension through farmer trainers, that is, enabling development and promotion among farmers through technical consultation, supervision activities, publicity and training. The data show that 94.4% of farmers believe that they have acquired new skills and increased their income in this way [100]. We believe that this is also a model of entrepreneurial diffusion, similar to the diffusion in China, and that it has achieved a consistent effect. Specifically, China‘s returning farmers use special family and geographical ties to teach entrepreneurial skills to poor households.

Cultivating young entrepreneurial leaders in rural areas has also begun to be favored by many countries. In the United States, youth entrepreneurship is increasingly being positioned as an important component of business development and revitalization, as young residents have the potential to make unique contributions to the economic landscape and rural communities [101]. They may exhibit unique attitudes and motivational advantages, such as greater responsiveness to new information and technology [102]. Developing countries such as India and Ghana have developed strategies to attract young people to agriculture by investing heavily in new technologies, with the aim of giving young people a leading role [103,104,105]. The Welsh government supports young farmers to enter decision-making positions to develop entrepreneurial activities with older, skilled farmers. Young farmers can effectively deploy management practices and entrepreneurial skills to improve resource availability and productivity [106]. This approach has increased the value of agricultural production and promoted the development of diversified agriculture [107]. The Malaysian government launched an entrepreneurial model for agricultural design in 2005 [108]. However, policy-driven agricultural entrepreneurship has a high failure rate and requires small farmers to take the initiative to adopt advanced information and communication technologies. In order to solve this problem, the national government has implemented a strategy of investing large sums of money to attract young people to agriculture. Young people have strong digital literacy, that is, the ability to obtain information tools, make rational use of digital resources and communicate efficiently [109,110]. However, youth may perceive employment in the agricultural sector to have a stigma [111,112]. Therefore, governments need to design program to change youth’s perceptions of agriculture, especially in developing countries [109,113]. This would convey advanced entrepreneurial skills and knowledge to other farmers and realize the transformation from traditional entrepreneurial farmers to multiple entrepreneurial farmers, which will ensure the stable alleviation poverty and economic stability of the community and solve the problems of small farmers in entrepreneurship.

In summary, poor people around the world are plagued by resource scarcity and low investment rates [114]. They need the example of entrepreneurial leaders. High-quality farmers and young people with advanced technology should drive other farmers to start businesses, which is essentially the same as the entrepreneurial diffusion in our case study [115]. They can provide management experience, entrepreneurship projects and advanced technologies to poor people with insufficient self-development ability, thus improving their welfare. Returning farmers’ entrepreneurship is a distinct phenomenon in Chinese society. They have mainly improved their entrepreneurial ability through working experience, and because of their kinship ties or geographical connections to rural society, they can effectively use the familiar rural social network to diffuse entrepreneurship practices to other farmers. Moreover, returning entrepreneurial farmers in China return to their local area to carry out production activities, as they have stronger attachments to their local area and will not easily leave, which has a positive effect on driving farmers’ entrepreneurship in the long run.

Our cases and the cases in other parts of the world show that entrepreneurial diffusion is conducive to increasing the economic income of the poor and alleviating relative poverty.

5. Conclusions

With the successful realization of eliminating absolute poverty, reducing relative poverty in the future is an increasing concern. Therefore, we must find a model to ensure the ability for self-proliferation and differentiation by improving the endogenous motivation of poor households. Over-reliance on the government must be shaken off [116]. The alleviation of relative poverty should not be limited to improving the economic income of poor households, but should consider the extent to which their social security and ecological rights are protected. The solutions described in the three examples we discussed here may provide inspiration for initiatives to reduce poverty in other regions of China and other parts of the world that are relatively poor. We hope that these examples will inspire the rest of the world to develop comparative advantageous industries based on the rational development of regional resources, thus alleviating relative poverty.

Countries with poverty problems can use returning entrepreneurial farmers as an effective means of promoting entrepreneurial activities in rural areas. Farmers returning home to start a business can effectively drive the return of talents, funds and other factors to the countryside, and also bring back a high-quality labor force to poor areas. The actual value and significance of returning entrepreneurial farmers to poor areas exceeds their own entrepreneurial activities [15] and has a significant impact on the economic and social development of poor areas. Through entrepreneurial diffusion, the overall development of rural areas has changed from “blood transfusion” to “blood donation”, which has helped to promote the integration of talents and industries in rural areas, to expand the agglomeration effect of rural industries, to build a long-term mechanism to alleviate relative poverty and to inject new vitality into efforts towards the goal of common prosperity.

It should be emphasized that the government should give policy support to returning entrepreneurial farmers in the early stages of entrepreneurship diffusion to reduce the obstacles to the diffusion of entrepreneurship. In other words, the government should further pay attention to, and guide the behavior of, those returning home to start a business in rural areas, and vigorously encourage farmers to return home to start a business. Specifically, it should be possible to reduce the threshold for entrepreneurship in rural areas through inclusive financial entrepreneurship loan policies, guiding returning farmers to establish high-quality, high-level enterprises, thus revitalizing the vitality of the rural economic system and injecting new momentum into reducing poverty in rural areas at the source. In addition, the government should comprehensively consider the local economy and entrepreneurial market environment, improve entrepreneurial support policies to attract farmers to return home to start businesses and not ignore the intergenerational and regional heterogeneity in the characteristics of returning entrepreneurial farmers [117]. This would avoid the vicious circle of increasing the scale of returning entrepreneurial groups without increasing their income, thereby increasing the possibility of farmers falling into poverty traps.

Over the past 40 years, China has provided a large number of practical cases for researchers around the world in terms of reducing poverty through the spread of entrepreneurship among returning farmers, mostly relative poverty.

6. Limitations and Future Research

Although the three cases described in this review all show the significant benefits of entrepreneurial diffusion to poor households, there are still areas for improvement. First of all, we evaluated the effect of entrepreneurial diffusion on reducing relative poverty mainly in terms of income level, which can also be obtained from official data. However, there are no detailed data on the environment protection brought about by entrepreneurial diffusion. We can only provide a qualitative analysis through actual observations and interviews. Obtaining quantitative data to describe the social and ecological benefits of entrepreneurial diffusion is still a challenge for future research. Moreover, we did not consider the optimal size of entrepreneurial diffusion. If more and more people become involved in similar projects to produce similar products, this is bound to lead to excessive market supply and lower prices, leading the poor into a poverty trap. The case study area is therefore being monitored and assessed on a long-term basis to ensure that the economic situation of poor households and those involved in entrepreneurship is improving, and that their social and ecological rights are also guaranteed. Such monitoring should be carried out through third-party agencies or government departments. For example, authorities should monitor whether the annual income of poor households is stable or growing, whether their employment is stable and whether the ecological environment in which they live is improving.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Z. and C.Y.; Methodology, Y.Z. and S.Y.; Validation, Y.Z., Y.X. and W.W.; Formal Analysis, Y.Z., C.Y. and S.Y.; Investigation, Y.Z., C.Y. and S.Y.; Data Curation, Y.Z. and C.Y.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, Y.Z.; Writing—Review and Editing, C.Y., S.Y. and W.W.; visualization, Y.Z. and W.W.; Supervision, Y.X.; Project Administration, Y.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, 2021SRZ04 and 2021SPS01.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Tollefson, J. UN approves global to-do list for next 15 years. Nature 2015, 525, 434–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.S.; Arshad, M.; Qian, L.; Zhao, M.; Mehmood, Y.; Kächele, H. Economic impact of climate change on crop farming in Bangladesh: An application of Ricardian method. Ecol. Econ. 2019, 164, 106354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wu, W.; Wang, Y. Global poverty dynamics and resilience building for sustainable poverty reduction. J. Geogr. Sci. 2021, 31, 1159–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, R.; Sultana, S.; Wang, J.; Mostofa, M.G.; Sarker, T.; Shah, M.M.R.; Hossain, M.S. Revegetation of coal mine degraded arid areas: The role of a native woody species under optimum water and nutrient resources. Environ. Res. 2022, 204, 111921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabbany, M.G.; Mehmood, Y.; Hoque, F.; Sarker, T.; Hossain, K.Z.; Khan, A.A.; Hossain, M.S.; Roy, R.; Luo, J. Do credit constraints affect the technical efficiency of Boro rice growers? Evidence from the District Pabna in Bangladesh. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 444–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, Y.; Zhang, F. The future path to China’s poverty reduction—Dynamic decomposition analysis with the evolution of China’s poverty reduction policies. Soc. Indic. Res. 2021, 158, 507–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Feng, X.; Wang, S.; Qiu, H. China’s poverty alleviation over the last 40 years: Successes and challenges. Aust. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2020, 64, 209–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.X.; Yan, X.Q. A Prospective Study on the Establishment of New Rural Poverty Standard after Year 2020. Issues Agric. Econ. 2020, 5, 17–27. [Google Scholar]

- Ascher, W. Coping with intelligence deficits in poverty-alleviation policies in low-income countries. Policy Sci. 2021, 54, 345–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, A.; Mullainathan, S.; Shafir, E.; Zhao, J. Poverty impedes cognitive function. Science 2013, 341, 976–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brünjes, J.; Diez, J.R. ‘Recession push’ and ‘prosperity pull’ entrepreneurship in a rural developing context. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2013, 25, 251–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, F.Z.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, X.B.; Tsai, C.H.; Lin, D.D. Farmers’ work-life quality and entrepreneurship will in China. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. Available online: http://www.moa.gov.cn/xw/shipin/202204/t20220427_6397912.htm (accessed on 18 July 2022).

- China Economic Net. Available online: http://www.ce.cn/xwzx/gnsz/gdxw/201711/03/t20171103_26743334.shtml (accessed on 3 July 2022).

- Duan, J.; Yin, J.; Xu, Y.; Wu, D. Should I stay or should I go? Job demands’ push and entrepreneurial resources’ pull in Chinese migrant workers’ return-home entrepreneurial intention. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2020, 32, 429–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F. China’s poverty alleviation “miracle” from the perspective of the structural transformation of the urban–rural dual economy. China Political Econ. 2021, 4, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias-Abey, M. Justice on Our Fields: Can “Alt-Labor” Organizations Improve Migrant Farm Workers’ Conditions? Harv. CR-CLL Rev. 2018, 53, 167. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.; Xiong, A.; Li, H.; Westlund, H.; Li, Y. Does social capital influence small business entrepreneurship? Differences between urban and rural China. Ann. Reg. Sci. 2019, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, S.; Korsgaard, S. Resources and bridging: The role of spatial context in rural entrepreneurship. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2018, 30, 224–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvão, A.R.; Mascarenhas, C.; Marques, C.S.E.; Braga, V.; Ferreira, M. Mentoring entrepreneurship in a rural territory—A qualitative exploration of an entrepreneurship program for rural areas. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 78, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gyimah, P.; Lussier, R.N. Rural entrepreneurship success factors: An empirical investigation in an emerging market. J. Small Bus. Strategy 2021, 31, 5–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, A.; Barber III, D. The gap in transition planning education opportunities for rural entrepreneurs. Am. J. Entrep. 2020, 13, 92–125. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Z. Social-Capital Mobilization and Income Returns to Entrepreneurship: The Case of Return Migration in Rural China. Environ. Plan. A Econ. Space 2002, 34, 1763–1784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Démurger, S.; Xu, H. Return Migrants: The Rise of New Entrepreneurs in Rural China. World Dev. 2011, 39, 1847–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M. Literature Review on Entrepreneurship Practice in Agriculture, Rural and Farmers under the Background of Rural Revitalization. Open Access Libr. J. 2022, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baniasadi, N.; Sadegh, E.; Ahmad, K. Factors influencing the development of rural entrepreneurship: A case study of Iran. Adv. Environ. Biol. 2013, 7, 1930–1936. [Google Scholar]

- Deller, S.; Kures, M.; Conroy, T. Rural entrepreneurship and migration. J. Rural Stud. 2019, 66, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Li, X.; Li, W.; Feng, J. Differences and Influencing Factors of Relative Poverty of Urban and Rural Residents in China Based on the Survey of 31 Provinces and Cities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Townsend, P. Poverty in the United Kingdom: A Survey of Household Resources and Standards of Living; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1979; pp. 46–49. [Google Scholar]

- Nolan, B.; Marx, I. Economic inequality, poverty, and social exclusion. In The Oxford Handbook of Economic Inequality; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009; pp. 315–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkire, S.; Santos, M.E. Measuring Acute Poverty in the Developing World: Robustness and Scope of the Multidimensional Poverty Index. World Dev. 2014, 59, 251–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/25141 (accessed on 6 July 2022).

- Bradbury, B.; Saunders, P. Housing costs and poverty: Analysing recent Australian trends. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2022, 37, 1073–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, M.; Chen, L.; Li, W. Financial Deepening, Spatial Spillover, and Urban–Rural Income Disparity: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, C.C.; Ma, Z.X. The analysis of the regional economic growth and the regional financial industry development difference in China based on the Theil index. Int. J. Econ. Financ. Stud. 2021, 13, 128–154. [Google Scholar]

- Ravallion, M.; Chen, S. Global poverty measurement when relative income matters. J. Public Econ. 2019, 177, 104046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, X. Literature review of relative poverty research. Voice Publ. 2020, 6, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, K.; Zhao, Y.; Ma, Y.; Li, Z. Green supply chain poverty alleviation through microfinance game model and cooperative analysis. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 226, 1022–1041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Li, S. Eliminating poverty through development: The dynamic evolution of multidimensional poverty in rural China. Econ. Polit. Stud. 2022, 10, 85–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Luo, Q.; Chen, G.; Zhang, Z.; Jin, P. Differences and dynamics of multidimensional poverty in rural China from multiple perspectives analysis. J. Geogr. Sci. 2022, 32, 1383–1404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, C.; Zhang, W. Green, poverty reduction and spatial spillover: An analysis from 21 provinces of China. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 24, 13610–13629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priyangga, M.R.Y.; Yasyfi, M.H. Quo Vadis Kebijakan: Analisa Vicious Circle of Poverty Nelayan Tradisional akibat Kebijakan PSBB. NeoRespublica J. Ilmu Pemerintah. 2020, 2, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, F. Is there a “Middle-income Trap”? Theories, experiences and relevance to China. China World Econ. 2012, 20, 49–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, C.B.; Carter, M.R.; Timmer, C.P. A century-long perspective on agricultural development. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2010, 92, 447–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayode, K.; Kelikume, G.; Olusegun, A.K. Entrepreneurial innovation and co-ordination failure: An application of a big push model to nigerian economy. Int. J. Econ. Commer. Manag. 2015, 3, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Rostow, W.W. The stages of economic growth: A non-communist manifesto (1960). In The Globalization and Development Reader: Perspectives on Development and Global Change; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; pp. 52–61. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, C.B.; Garg, T.; McBride, L. Well-Being Dynamics and Poverty Traps. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 2016, 8, 303–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.S.; Hua, Y.F.; Tao, R.; Moldovan, N.C. Can health human capital help the sub-Saharan Africa out of the poverty trap? An ARDL model approach. Front. Public Health 2021, 642, 697826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lade, S.J.; Haider, L.J.; Engström, G.; Schlüter, M. Resilience offers escape from trapped thinking on poverty alleviation. Sci. Adv. 2017, 3, e1603043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Wang, W.; Zhang, L. The power of informal institutions: The impact of clan culture on the depression of the elderly in rural China. J. Integr. Agric. 2021, 20, 1107–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berisha, E. Trickle Down? A little bit. Econ. Bull. 2018, 38, 725–732. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, H.U.R.; Nassani, A.A.; Aldakhil, A.M.; Abro, M.M.Q.; Islam, T.; Zaman, K. Pro-poor growth and sustainable development framework: Evidence from two step GMM estimator. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 206, 767–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.; Khan, K.B.; Zaman, K.; Musah, M.B.; Sudiapermana, E.; Aziz, A.R.A.; Anis, S.N.M. Achieving pro-poor growth and environmental sustainability agenda through information technologies: As right as rain. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 41000–41015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garfinkel, I.; Haveman, R.H. Earnings Capacity, Poverty, and Inequality; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.L. Review of Poverty Alleviation Work in Rural Areas in China and Its Future Prospects. J. Hum. Rts. 2017, 16, 205. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Cao, P.; Huang, S. Household financial literacy and relative poverty: An analysis of the psychology of poverty and market participation. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 898486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogers, E.M.; Singhal, A.; Quinlan, M.M. An integrated approach to communication theory and research. In Diffusion of Innovations; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 432–448. [Google Scholar]

- Batista, C.; McIndoe-Calder, T.; Vicente, P.C. Return Migration, Self-selection and Entrepreneurship. Oxf. Bull. Econ. Stat. 2017, 79, 797–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C. Return migration, online entrepreneurship and gender performance in the Chinese ‘Taobao families’. Asia Pac. Viewp. 2020, 61, 478–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dibra, M. Rogers theory on diffusion of innovation-the most appropriate theoretical model in the study of factors influencing the integration of sustainability in tourism businesses. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 195, 1453–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutter, C.; Bruton, G.D.; Chen, J. Entrepreneurship as a solution to extreme poverty: A review and future research directions. J. Bus Ventur. 2019, 34, 197–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X. Asean-China cooperation for poverty reduction. In China’s E-Commerce Poverty Alleviation Policy Practices and Cases; World Scientific: Singapore, 2022; pp. 23–39. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.; He, C.; Chen, L.; Cao, S. Improving food security in China by taking advantage of marginal and degraded lands. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 171, 1020–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Yang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Xue, Y. Using Marginal Land Resources to Solve the Shortage of Rural Entrepreneurial Land in China. Land 2022, 11, 1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Zhang, Y.; Xue, Y.; Xue, Y. Toward a Socio-Political Approach to Promote the Development of Circular Agriculture: A Critical Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 13117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhou, Y. Spatio-temporal patterns of rural poverty in China and targeted poverty alleviation strategies. J. Rural Stud. 2017, 52, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.D.; P, L.B. Compilation of Typical Cases of Outstanding Leaders in Rural Entrepreneurship and Innovation; China Agriculture Press: Beijing, China, 2021; pp. 40–224. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, H.; Zhang, H.; Yu, Y.; Xu, D.; Wang, H. The Influencing Mechanism of Social Capital on the Identification of Entrepreneurial Opportunities for New Farmers. Am. J. Ind. Bus. Manag. 2020, 10, 1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Mu, R. Mass Entrepreneurship and Mass Innovation in China. In The Oxford Handbook of China Innovation; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 254–271. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L. Integration and Optimization of E-Commerce Industry Cluster and Green Supply Chain Network under the Background of Rural Revitalization. J. Sociol. Ethnol. 2021, 3, 64–83. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Fan, Y. Research on the Linkage Mechanism between Migrant Workers Returning Home to Start Businesses and Rural Industry Revitalization Based on the Combination Prediction and Dynamic Simulation Model. Comput. Intell. Neurosci. 2022, 2022, 1848822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, Z.; Keqiang, W.; Hung, T.K.; Zijun, W. Configuration Analysis of Determinants of Returning Home Entrepreneurial Model Based on FSQCA Method. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Education and Technology 2021, Malang, Indonesia, 18–19 September 2021; pp. 24–31. [Google Scholar]

- Jaeck, M.L.; Lifran, R. On-farm management of rice cultivars: How economic determinants drive diversity. Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2013, 19, 325–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanxi Provincial Bureau of Statistics. Available online: http://tjj.shanxi.gov.cn/tjsj/tjgb/202103/t20210318_729368.shtml (accessed on 15 July 2022).

- Xinhua News Agency. Available online: https://news.sina.com.cn/c/2020-10-04/doc-iivhvpwz0277460.shtml (accessed on 15 August 2022).

- Qinghai News Network. Available online: http://www.qhnews.com/newscenter/system/2022/07/08/013598147.shtml (accessed on 15 September 2022).

- Qinghai Provincial Bureau of Statistics. Available online: http://tjj.qinghai.gov.cn/tjData/yearBulletin/202103/t20210304_71860.html (accessed on 12 September 2022).

- Qinghai Daily. Available online: https://epaper.tibet3.com/founder/SearchServlet.do (accessed on 22 September 2022).

- China National Radio. Available online: http://gongyi.cnr.cn/news/20190515/t20190515_524613533.shtml (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- NTV. Available online: https://baijiahao.baidu.com/s?id=1681718227419807875&wfr=spider&for=pc (accessed on 28 September 2022).

- Lingshan County People’s Government. Available online: http://zwgk.gxls.gov.cn/auto2662/tjxx/202101/t20210129_3470205.html (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- Yamamori, T. The Smithian ontology of ‘relative poverty’: Revisiting the debate between Amartya Sen and Peter Townsend. J. Econ. Methodol. 2019, 26, 70–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravallion, M.; Chen, S. Weakly relative poverty. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2011, 93, 1251–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, A. Equality Street: Ideology and attitudes towards the purely relative definition of poverty. Econ. Aff. 2022, 42, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, J. Social equality, relative poverty and marginalised groups. In The Equal Society: Essays on Equality in Theory and Practice; Lexington Books: London, UK, 2015; pp. 21–41. [Google Scholar]

- Jiuwen, S.; Tian, X. China’s anti-poverty strategy and post-2020 relative poverty line. China Econ. 2020, 15, 62–75. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Huang, X.; Bao, H.X.H.; Ju, X.; Zhong, T.; Chen, Z.; Zhou, Y. Rural land rights reform and agro-environmental sustainability: Empirical evidence from China. Land Use Policy 2018, 74, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Kapucu, N. Examining the impacts of disaster resettlement from a livelihood perspective: A case study of Qinling Mountains, China. Disasters 2018, 42, 251–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, Y. Efficiency of construction land allocation in China: An econometric analysis of panel data. Land Use Policy 2018, 74, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Q.; Mai, Q. How to Improve New Generation Migrant Workers’ Entrepreneurial Willingness—A Moderated Mediation Examination from the Sustainable Perspective. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zameer, H.; Shahbaz, M.; Vo, X.V. Reinforcing poverty alleviation efficiency through technological innovation, globalization, and financial development. Technol. Forecast. Soc. 2020, 161, 120326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; de Sherbinin, A.; Liu, Y. China’s poverty alleviation resettlement: Progress, problems and solutions. Habitat Int. 2020, 98, 102135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Zhou, J.X.; Wang, Y.; Xi, Y. Rural Entrepreneurship in an Emerging Economy: Reading Institutional Perspectives from Entrepreneur Stories. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2013, 51, 183–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X.; Li, X.; Zhu, R.; Sun, Y.; Wang, Q. The Relationship Network within Spatial Situation: Embeddedness and Spatial Constraints of Farmers’ Behaviors. Land 2022, 11, 485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, H.; Li, L.; Qian, X.; Zeng, Y. Can rural e-commerce service centers improve farmers’ subject well-being? A new practice of ‘internet plus rural public services’ from China. Int. Food Agribus. Manag. Rev. 2020, 23, 681–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China. Available online: http://www.gov.cn/guoqing/2021-04/09/content_5598662.htm (accessed on 21 September 2022).

- Tindiwensi, C.K.; Munene, J.C.; Sserwanga, A.; Abaho, E.; Namatovu-Dawa, R. Farm management skills, entrepreneurial bricolage and market orientation. J. Agribus. Dev. Emerg. Econ. 2020, 10, 717–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tindiwensi, C.K.; Abaho, E.; Munene, J.C.; Muhwezi, M.; Nkote, I.N. Entrepreneurial bricolage in smallholder commercial farming: A family business perspective. J. Fam. Bus. Manag. 2020, 11, 423–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Zhu, H. Return migrants’ entrepreneurial decisions in rural China. Asian Popul. Stud. 2020, 16, 61–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsafack, S.; Degrande, A.; Franzel, S.; Simpson, B. Farmer-to-farmer extension: A survey of lead farmers in Cameroon. In ICRAF Working Paper; World Agroforestry Centre: Nairobi, Kenya, 2015; pp. 1–64. [Google Scholar]

- De Guzman, M.R.T.; Kim, S.; Taylor, S.; Padasas, I. Rural communities as a context for entrepreneurship: Exploring perceptions of youth and business owners. J. Rural Stud. 2020, 80, 45–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]