SAT-Based Optimization Framework for Electric Vehicle Charging Station Routing Under Real-World Constraints

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Proposes a SAT-based optimization model that selects optimal EV charging stations by encoding real-world constraints (SoC, cost, distance, charger type).

- Integrates Google OR-Tools CP-SAT solver to efficiently evaluate feasible charging routes and minimize travel time, distance, and cost.

2. Literature Review

3. Preliminaries

3.1. Problem Definition

- Td(s): Total driving distance to and from the station;

- Tt(s): Total travel time including driving, waiting, and charging;

- Tr(s): Charging fee rate in USD/kWh.

3.2. Unified Problem Scope

4. Mathematical Model for the Charging Station

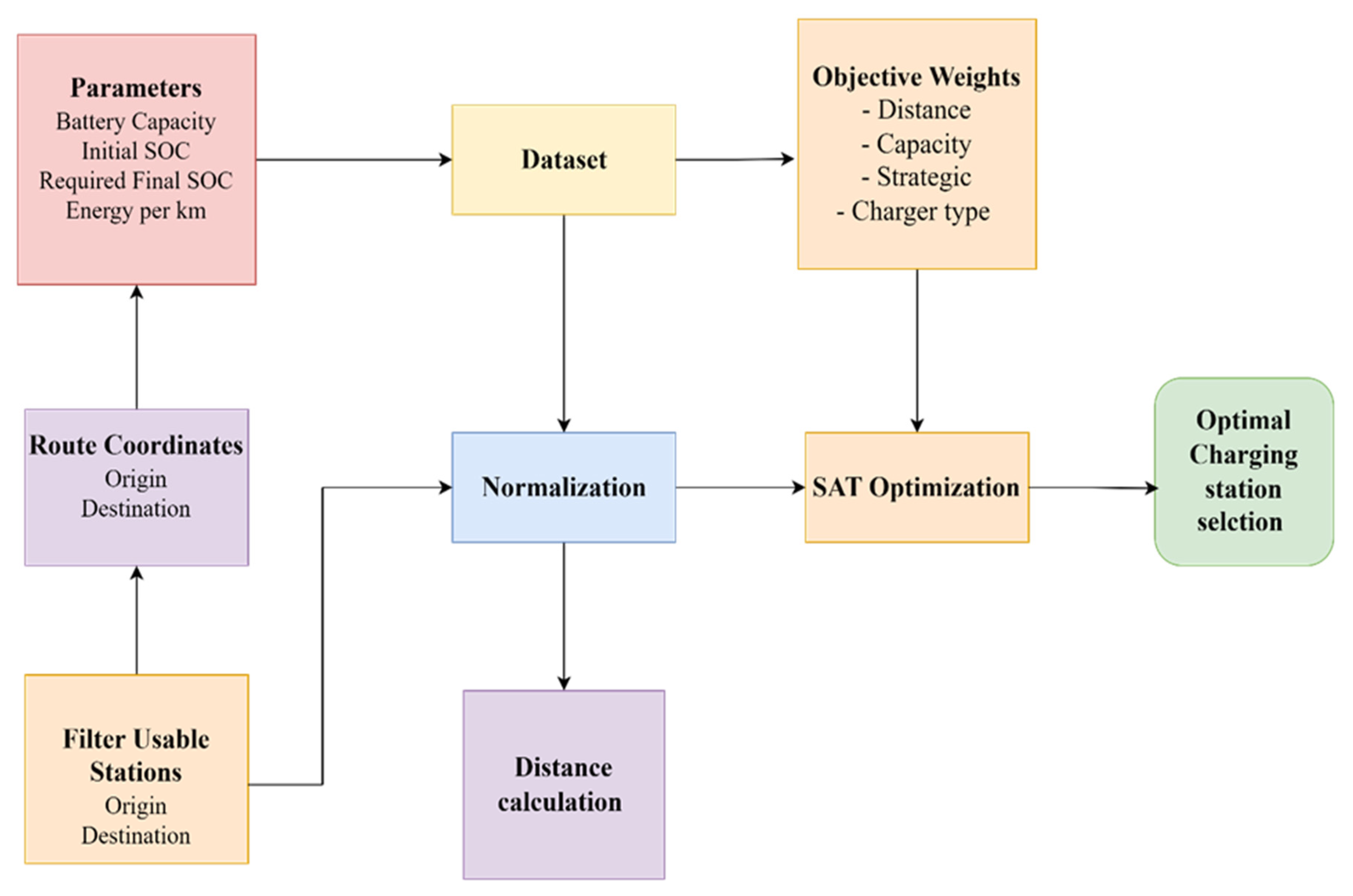

4.1. Data Modelling and Problem Setup

4.2. Decision Variable Definition

Incorporating Sequence-Dependency in Route Modeling

4.3. Objective Function

- S = {1, 2, n}: the set of all candidate charging stations.

- Xi ∈ {0, 1}: a binary decision variable indicating whether charging station i is selected (xi = 1) or not (xi = 0).

- : precomputed normalized distance from the vehicle’s current location or previous stop to station i,

- : inverse normalized power capacity of station i,

- : normalized strategic importance of the station’s location,

- : normalized compatibility score between station i’s charger and the EV’s supported charging standard.

- wd: weight for distance (minimize deviation from the route),

- wc: weight for charger performance (prefer higher capacity),

- ws: weight for strategic importance (e.g., proximity to highways),

- wt: weight for charger type compatibility.

4.4. Constraint Modeling

4.5. Conjunctive Normal Form (CNF) Transformation Using De Morgan’s Theorem

CNF Encoding for Arithmetic and Pseudo-Boolean Constraints

4.6. Solver Integration

| Algorithm 1: Optimal EV Charging Station Selection via SAT-Based Multi-Criteria Optimization |

| Require: Set of candidate stations ; 1: Distance vector ; Capacity vector ; 2: ; Compatibility vector ; 3: Weight parameters where ; 4: Selection limit , detour threshold , compatibility threshold ; 5: Ensure: Optimal subset of stations 6: Normalization: 7: for to do 8: 9: 10: 11: ▹(Already in [0, 1]) 12: end for 13: Define binary decision variables: 14: Objective Function: 15: Constraints: 16: 17: if 18: if 19: 20: for all 21: Encode all constraints into CNF clauses: 22: Use De Morgan’s Theorem, auxiliary variables, and Tseitin transformation 23: Pass encoded CNF clauses to CP-SAT solver: 24: Solve to find feasible assignment of minimizing the objective 25: Output: 26: return |

4.7. Reproducibility

4.8. Performance Metrics

- Total Distance (km): This represents the cumulative travel distance from the origin to the destination, including any detours to selected charging stations. It is computed using geographic coordinates via Haversine or routing APIs.

- Estimated Time (min): Total travel time is estimated by incorporating route travel speed, detour delays, and time spent at charging stations based on availability and power capacity.

- Total Energy Consumption (kWh): Calculated as the product of travel distance and the EV’s energy consumption rate (kWh/km), this metric ensures energy feasibility given the battery’s state of charge (SoC).

- Total Cost ($): Derived from the charging rate ($/kWh) at the selected station(s) and the amount of energy required during each stop.

- Number of Charging Stops: Indicates how many charging stations were selected by the model within the allowed maximum stops. It reflects route simplicity and continuity.

- Average Weighted Score: The mean of the individual station scores computed via the weighted multi-objective function combining normalized distance, inverse capacity, strategic importance, and charger compatibility.

- Computation Time (s): Time taken by the CP-SAT solver to find an optimal station subset that satisfies all CNF-encoded constraints and minimizes the objective.

- Memory Usage (MB): RAM consumed during the execution, measured using Python 3.12 memory profilers to ensure computational scalability.

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Results

5.2. Discussion

5.3. Computational Overhead of CNF Conversion Using De Morgan’s Theorem

5.4. SAT-Based Framework Performs in Large-Scale, Geographically Dispersed, Non-Urban Networks

5.5. Handling Real-Time Dynamics

5.6. Higher Average Weighted Score

5.7. Comparison with Hybrid and AI-Augmented Optimization

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SAT | Boolean Satisfiability Problem |

| CNF | Conjunctive Normal Form |

| SoC | State of Charge (of the EV battery) |

| CP-SAT | Constraint SAT Solver (Google OR-Tools) |

| EV | Electric Vehicle |

| AC/DC | Alternating Current/Direct Current (Charger Type) |

| LP | Linear Programming |

References

- Ahmad, A.; Khalid, M.; Ullah, Z.; Ahmad, N.; Aljaidi, M.; Malik, F.A.; Manzoor, U. Electric Vehicle Charging Modes, Technologies and Applications of Smart Charging. Energies 2022, 15, 9471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljaidi, M.; Aslam, N.; Kaiwartya, O. Optimal Placement and Capacity of Electric Vehicle Charging Stations in Urban Areas: Survey and Open Challenges. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Jordan International Joint Conference on Electrical Engineering and Information Technology (JEEIT), Amman, Jordan, 9–11 April 2019; pp. 238–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljaidi, M.; Aslam, N.; Chen, X.; Kaiwartya, O.; Khalid, M. An Energy Efficient Strategy for Assignment of Electric Vehicles to Charging Stations in Urban Environments. In Proceedings of the 2020 11th International Conference on Information and Communication Systems (ICICS), Irbid, Jordan, 7–9 April 2020; pp. 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlJamal, M.; Mughaid, A.; Al shboul, B.; Bani-Salameh, H.; Alzubi, S.; Abualigah, L. Optimizing risk mitigation: A simulation-based model for detecting fake IoT clients in smart city environments. Sustain. Comput. Informatics Syst. 2024, 43, 101019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljaidi, M.; Aslam, N.; Chen, X.; Kaiwartya, O.; Al-Gumaei, Y.A. Energy-efficient EV Charging Station Placement for E-Mobility. In Proceedings of the IECON 2020 the 46th Annual Conference of the IEEE Industrial Electronics Society, Singapore, 18–21 October 2020; pp. 3672–3678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljaidi, M.; Aslam, N.; Samara, G.; Almatarneh, S.; AL-Qawasmi, K.; Alqammaz, A. EV Charging Station Placement and Sizing Techniques: Survey, Challenges and Directions for Future Work. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Arab Conference on Information Technology (ACIT), Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 22–24 November 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljaidi, M.; Alsarhan, A.; Samara, G.; Alazaidah, R.; Almatarneh, S.; Khalid, M.; Al-Gumaei, Y.A. NHS WannaCry Ransomware Attack: Technical Explanation of The Vulnerability, Exploitation, and Countermeasures. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Engineering Conference on Electrical, Energy, and Artificial Intelligence (EICEEAI), Zarqa, Jordan, 6–8 December 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljaidi, M.; Aslam, N.; Chen, X.; Kaiwartya, O.; Al-Gumaei, Y.A.; Khalid, M. A Reinforcement Learning-based Assignment Scheme for EVs to Charging Stations. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 95th Vehicular Technology Conference: (VTC2022-Spring), Helsinki, Finland, 19–22 June 2022; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quttoum, A.N.; Alsarhan, A.; Moh’d, A.; Alshareet, O.; Nawaf, S.; Khasawneh, F.; Aljaidi, M.; Alshammari, M.; Awasthi, A. ABLA: Application-Based Load-Balanced Approach for Adaptive Mapping of Datacenter Networks. Electronics 2023, 12, 3689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quttoum, A.N.; Nawaf, S. An Autonomous Dynamic Navigation Model for Shortest Path Routing of Electrical Vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 20th International Conference on Mobile Ad Hoc and Smart Systems (MASS), Toronto, ON, Canada, 25–27 September 2023; pp. 622–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velimirović, L.Z.; Janjić, A.; Vranić, P.; Velimirović, J.D.; Petkovski, I. Determining the Optimal Route of Electric Vehicle Using a Hybrid Algorithm Based on Fuzzy Dynamic Programming. IEEE Trans. Fuzzy Syst. 2023, 31, 609–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqahtani, H.; Kumar, G. Efficient Routing Strategies for Electric and Flying Vehicles: A Comprehensive Hybrid Metaheuristic Review. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2024, 9, 5813–5852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Shao, C.; Hu, Z.; Shahidehpour, M. An MILP Method for Optimal Planning of Electric Vehicle Charging Stations in Coordinated Urban Power and Transportation Networks. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2023, 38, 5406–5419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azéma, M.; Desaulniers, G.; Mendoza, J.E.; Pesant, G. A Constraint Programming Model for the Electric Bus Assignment Problem with Parking Constraints. In Integration of Constraint Programming, Artificial Intelligence, and Operations Research; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; Volume 14742, pp. 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Qiu, Y.; Coates, R.L.; Dobbelaere, C.M.; Seles, P. Depot Charging Schedule Optimization for Medium- and Heavy-Duty Battery-Electric Trucks. World Electr. Veh. J. 2024, 15, 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, P.S.; Schiffer, M. Electric Vehicle Charge Scheduling with Flexible Service Operations. Transp. Sci. 2023, 57, 1605–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslinger, X.; Gaar, E.; Parragh, S.N. An exact approach for the multi-depot electric vehicle scheduling problem. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.13063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavvos, E.; Gerding, E.H.; Brede, M. A Comprehensive Game-Theoretic Model for Electric Vehicle Charging Station Competition. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2022, 23, 12239–12250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, B.; Ghaddar, B.; Nathwani, J. Electric vehicle routing with charging/discharging under time-variant electricity prices. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2021, 130, 103285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keskin, M.; Çatay, B. Partial recharge strategies for the electric vehicle routing problem with time windows. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2016, 65, 111–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruglieri, M.; Pezzella, F.; Pisacane, O.; Suraci, S. A matheuristic for the electric vehicle routing problem with time windows. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1506.00211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eén, N.; Sörensson, N. Translating pseudo-boolean constraints into SAT. J. Satisf. Boolean Model. Comput. 2006, 2, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biere, A.; Järvisalo, M.; Kiesl, B. Preprocessing in SAT solving. In Handbook of Satisfiability; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 391–435. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, T.; Cassandras, C.G.; Pourazarm, S. Energy-aware Vehicle Routing in Networks with Charging Nodes. IFAC Proc. Vol. 2014, 47, 9611–9616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Google; OR-Tools CP-SAT Solver. Available online: https://developers.google.com/optimization/cp/cp_solver (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Krupke, D. The CP-SAT Primer: Using and Understanding Google OR-Tools’ CP-SAT Solver. Available online: https://d-krupke.github.io/cpsat-primer/ (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Accorsi, L.; Vigo, D. A fast and scalable heuristic for the solution of large-scale capacitated vehicle routing problems. Transp. Sci. 2021, 55, 815–967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, P.; Arruda, A. Post-Improving the Capacitated Vehicle Routing Problem Using a Max-SAT Solver. In Workshop Brasileiro de Lógica (WBL); Sociedade Brasileira de Computação (SBC): Porto Alegre, Brazil, 2025; pp. 32–39. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Ding, Y.; Chen, Z.; Su, Z.; Zhuang, Y. Heuristic Algorithms for Heterogeneous and Multi-Trip Electric Vehicle Routing Problem with Pickup and Delivery. World Electr. Veh. J. 2024, 15, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murgai, S.; Bhagwat, H.; Dandekar, R.; Dandekar, R.; Panat, S. A Scientific Machine Learning Approach for Predicting and Forecasting Battery Degradation in Electric Vehicles. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.14347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, W.; Le, H.; Nguyen, K.T.P.; Gogu, C.; Medjaher, K.; Morio, J.; Wu, D. A generic physics-informed machine learning framework for battery remaining useful life prediction using small early-stage lifecycle data. Appl. Energy 2025, 384, 125314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Ma, W.; Wang, L.; Ren, Y.; Yu, C. Enabling In-Depot Automated Routing and Recharging Scheduling for Automated Electric Bus Transit Systems. J. Adv. Transp. 2021, 2021, 5531063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.; Liu, C.; Dai, B.; Li, J.; Wu, Z.; Guo, Y. Electric vehicle routing problem considering energy differences of charging stations. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 418, 138184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesam Sadati, M.E.; Çatay, B.; Aksen, D. An efficient variable neighborhood search with tabu shaking for a class of multi-depot vehicle routing problems. Comput. Oper. Res. 2021, 133, 105269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manriquez-Padilla, C.G.; Cueva-Perez, I.; Dominguez-Gonzalez, A.; Elvira-Ortiz, D.A.; Perez-Cruz, A.; Saucedo-Dorantes, J.J. State of Charge Estimation Model Based on Genetic Algorithms and Multivariate Linear Regression with Applications in Electric Vehicles. Sensors 2023, 23, 2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mavrovouniotis, M.; Ellinas, G.; Polycarpou, M. Ant Colony Optimization for the Electric Vehicle Routing Problem. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Symposium Series on Computational Intelligence (SSCI), Bangalore, India, 18–21 November 2018. [Google Scholar]

| Refs. | Method | SoC Estimation | Charging Time | Cost | Distance | Charger Type Compatibility | Real-Time Optimization | Gap |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [13] | MILP for CS Network Design | ✘ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✘ | SoC and dynamic decision-making not modelled; logic rules not encoded. |

| [14] | Constraint Programming | ✔ | ✔ | ✘ | ✔ | ✔ | ✘ | Scalable for depot use only; lacks integration of CNF/logical structure. |

| [15] | Queuing Theory + Simulation | ✘ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✘ | ✘ | SoC, charger compatibility, and logic constraints not modelled. |

| [16] | Branch & Price algorithm | ✔ | ✘ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✘ | Static planning; does not model constraints as logic expressions. |

| [17] | Multi-objective Lineal Programing (3-index MILP) Optimization | ✘ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✘ | Cannot adapt to real-time SoC/state or handle CNF-based decisions. |

| [18] | Game Theory | ✘ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✘ | Highly theoretical; lacks direct integration of SoC or logical feasibility checks. |

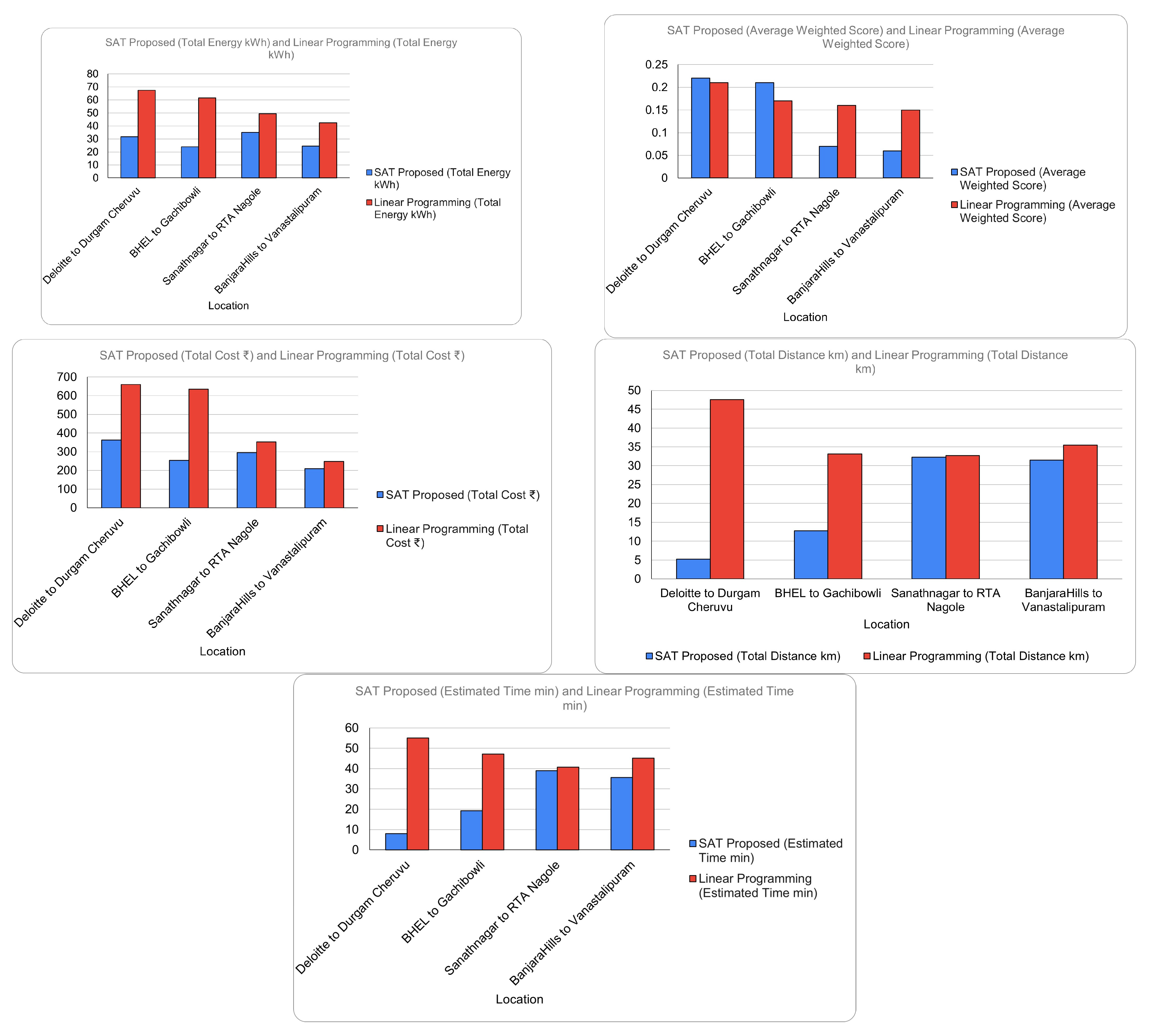

| Method | Location | Total Distance (km) | Estimated Time (min) | Total Energy (kWh) | Total Cost ($) | Number of Stops | Average Weighted Score | Computation Time (s) | Memory Usage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

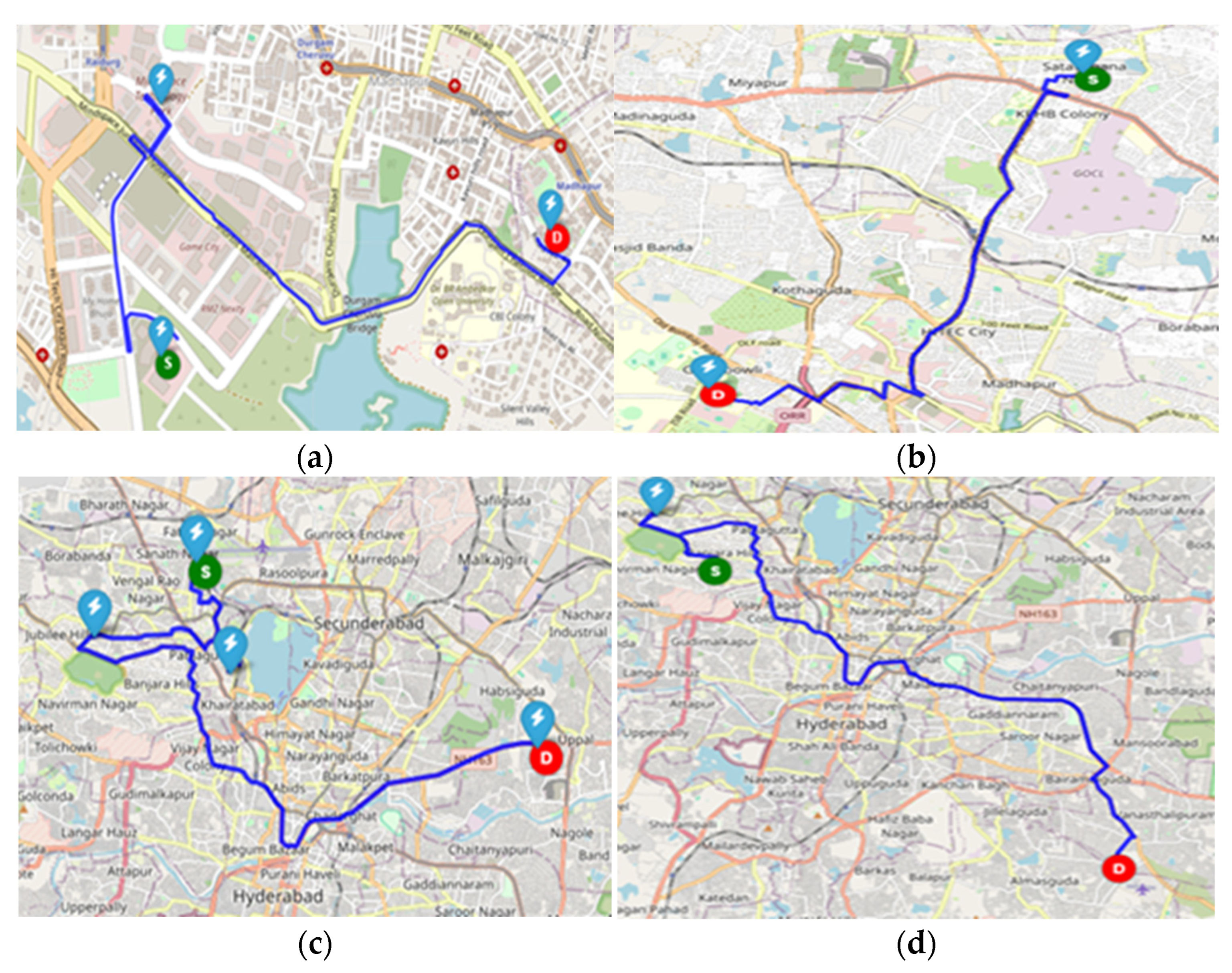

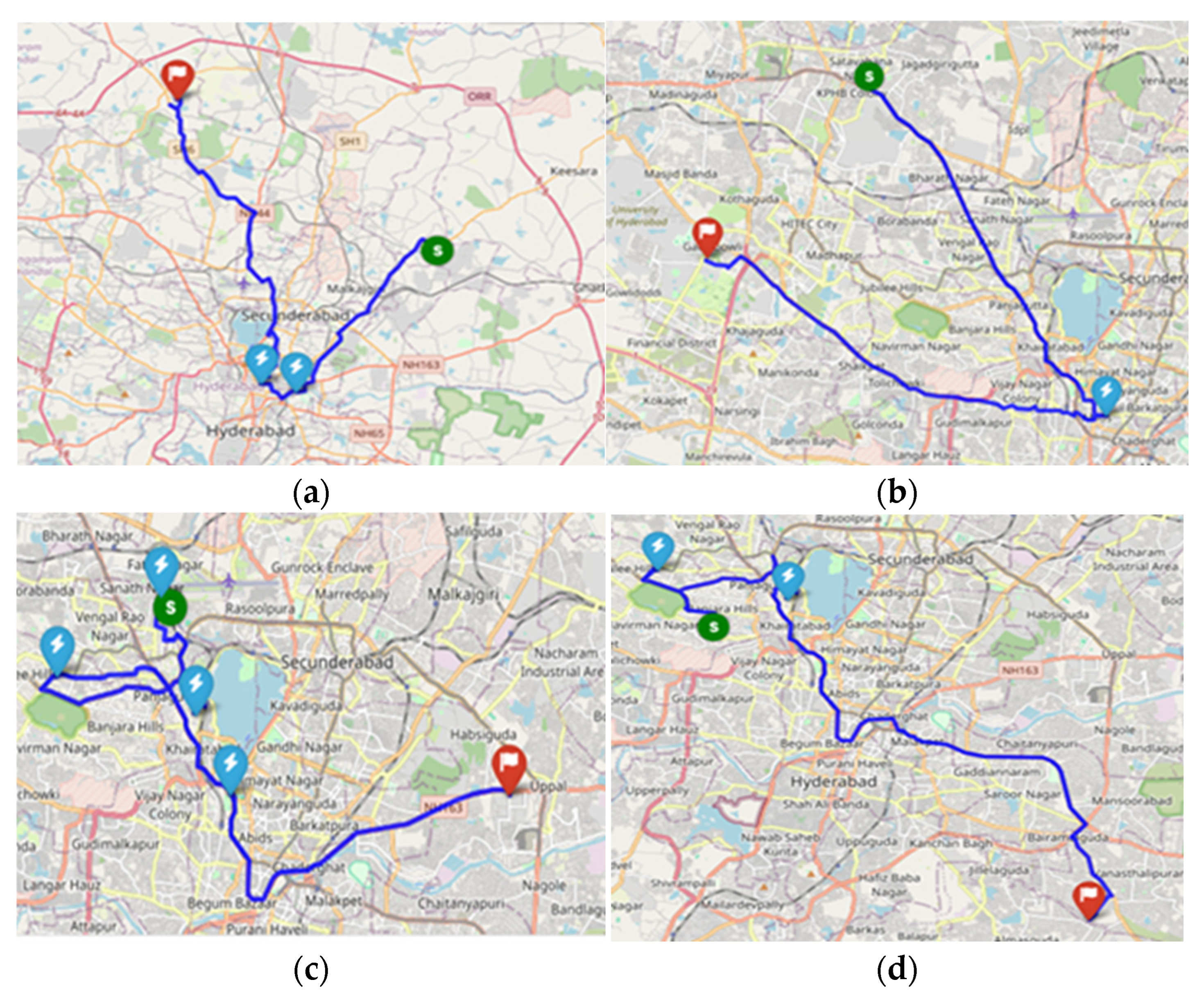

| SAT Proposed | Deloitte Meenakshi Station to Durgam Cheruvu | 5.25 | 7.98 | 31.6 | 4.35 | 3 | 0.2138 | 0.02 | 228.75 MB |

| Linear Programming | 47.56 | 55.02 | 67.35 | 7.92 | 2 | 0.2057 | 0.05 | 282.33 MB | |

| SAT Proposed | BHEL MIG Colonyto Gachibowli | 12.81 | 19.33 | 23.94 | 3.04 | 2 | 0.2115 | 0.01 | 299.31 MB |

| Linear Programming | 33.13 | 47.15 | 61.48 | 7.61 | 1 | 0.1224 | 5.01 | 283.36 MB | |

| SAT Proposed | Sanathnagar IT Park to RTA Nagole | 32.29 | 39.02 | 34.95 | 3.54 | 4 | 0.0637 | 2.11 | 299.69 MB |

| Linear Programming | 32.69 | 40.7 | 49.25 | 4.22 | 4 | 0.1601 | 1.21 | 301.52 MB | |

| SAT Proposed | Banjara Hills to Vanasthalipuram | 31.46 | 35.69 | 24.42 | 2.52 | 1 | 0.0609 | 0.11 | 305.56 MB |

| Linear Programming | 35.53 | 45.14 | 42.38 | 2.98 | 2 | 0.1551 | 2.2 | 301.88 MB | |

| Mixed Integer Nonlinear Programming) with dynamic programming [24] | Simulated Network | 120 | 180 | 25 | -- | 2 | -- | 5 | -- |

| EVRPTW-TP (Variable Neighborhood Search + Tabu Search hybrid, supported by Lagrangian Relaxation [19] | Kitchener–Waterloo fleet delivery | 150 | 240 | 35 | 37.80 | 3–4 | -- | 120 | -- |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the World Electric Vehicle Association. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ravipati, S.S.R.K.; Jalluri, S.R.; Kunta, S. SAT-Based Optimization Framework for Electric Vehicle Charging Station Routing Under Real-World Constraints. World Electr. Veh. J. 2025, 16, 659. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj16120659

Ravipati SSRK, Jalluri SR, Kunta S. SAT-Based Optimization Framework for Electric Vehicle Charging Station Routing Under Real-World Constraints. World Electric Vehicle Journal. 2025; 16(12):659. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj16120659

Chicago/Turabian StyleRavipati, Shiva Sai Rama Krishna, Srinivasa Rao Jalluri, and Srikanth Kunta. 2025. "SAT-Based Optimization Framework for Electric Vehicle Charging Station Routing Under Real-World Constraints" World Electric Vehicle Journal 16, no. 12: 659. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj16120659

APA StyleRavipati, S. S. R. K., Jalluri, S. R., & Kunta, S. (2025). SAT-Based Optimization Framework for Electric Vehicle Charging Station Routing Under Real-World Constraints. World Electric Vehicle Journal, 16(12), 659. https://doi.org/10.3390/wevj16120659