Abstract

The increasing atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions are widely recognized as the primary driving force behind the phenomenon of global warming. Considering environmental concerns and the depletion of fossil fuel reserves, the use of electric vehicles (EVs) in transportation has emerged as one of the most promising technological alternatives to conventional gasoline-powered cars. Compared to their gasoline counterparts, EVs significantly reduce the costs associated with air pollution and mitigate adverse effects on human health. Owing to these characteristics, EVs have become one of the key components of the transition toward a sustainable future, while also steering the transformation of the global automotive industry. This transition is reshaping the structure of the global automobile industry. Many countries aim to achieve their greenhouse gas reduction targets by promoting the adoption of EVs. This study aims to empirically examine the effects of electric vehicles on CO2 emissions in 15 high-income countries during the period 2010–2023, highlighting both short- and long-term environmental impacts. The analysis also considers economic and socio-demographic variables such as gross domestic product (GDP), urbanization, and fossil fuel consumption. The findings indicate that the share of EVs significantly reduces CO2 emissions, whereas sales have a short-term increasing effect.

1. Introduction

Climate change poses a significant threat to ecosystems worldwide, from the oceans to the land and various layers of the atmosphere and is largely driven by the widespread use of fossil fuels. The issue of climate change has been rigorously debated by many governments. Numerous reports highlight the adverse impacts of climate change resulting from human activities. Given the transportation sector’s substantial contribution to global greenhouse gas emissions, improving vehicle fuel economy has become an integral component of climate policy. The need to improve the economy of automobile fuel has become increasingly prominent due to declining oil reserves, the negative consequences of climate change, and emission regulations [1].

The widespread adoption of EVs plays a crucial role in mitigating the environmental impacts of CO2 emissions [2]. The energy sector is responsible for most greenhouse gas emissions that drive climate change, and a substantial share of these emissions originates from the combustion of fossil fuels. Global energy-related CO2 emissions reached approximately 34 billion tons in 2023, representing a 49% increase compared to the year 2000 [3]. Therefore, promoting green development and reducing carbon emissions emerge as key objectives of socio-economic transformation, drawing significant attention from governments and policymakers. Understanding the factors that influence carbon emissions is crucial for countries to set ambitious reduction targets and implement them effectively. Energy used in transportation accounts for 23.3% of total emissions, ranking second among energy-related CO2 sources, following electricity and heat producers [3]. Considering that global CO2 reduction targets also encompass the transport sector, collective efforts are required to transition from conventional fossil fuel-powered internal combustion engines to alternative technologies such as electric drive systems. In this context, the development of green and clean transportation can contribute effectively to global CO2 emission reduction efforts.

In recent years, the promotion of EV policies in certain countries has highlighted trends in the automotive industry toward energy efficiency and emission reduction, while expectations for reducing pollution from motor vehicles have increased [4]. By design, EV produces minimal, or even zero, exhaust emissions (especially CO2) [5]. Specifically, since EVs replace conventional fossil fuels (such as gasoline) with electrical energy, they can significantly improve energy use efficiency and help protect the environment by reducing pollution. According to a study by Kim et al. [6], battery electric vehicles (BEVs) are expected to reduce CO2 emissions by more than 60% compared to conventional vehicle models by 2050.

The main advantage of BEVs and FCEVs lies in their “zero-emission” feature and the consequent reduction in air pollution. Recent studies indicate that integrated energy and thermal management strategies can substantially improve the environmental and economic performance of fuel cell vehicles. For example, intelligent control of battery and fuel cell temperatures helps prevent overheating and extend system lifetime, while coordinated optimization between the cabin air-conditioning system and the powertrain reduces hydrogen consumption and overall operating costs [7]. However, when the entire production process is considered, the “zero-emission” characteristic of BEVs and FCEVs is not absolute, since CO2 emissions occur at various stages of the vehicle lifecycle. Furthermore, the discussion often overlooks “who or what the main polluting contributor is and in what form it occurs.” For instance, chemical pollution during the production of fuel cells and batteries (or electrochemical plants for fuel cells), emissions from vehicle manufacturing, and contamination arising from the processing of discarded batteries are also among the sources of pollution [8]. Compared with conventional vehicles, EVs are more energy-efficient. However, the overall well-to-wheel (WTW) efficiency is also influenced by the performance of the energy production system. For instance, total WTW efficiency ranges from 11% to 27% for gasoline vehicles, whereas for diesel vehicles, it is reported to lie between 25% and 37% [9]. In contrast, EVs powered by natural gas-fired power plants have WTW efficiencies between 13% and 31%, whereas EVs powered by renewable energy sources can achieve efficiencies of up to 70% [10].

Recent studies indicate that the climate benefits of EV adoption critically depend on the carbon intensity of the electricity used for charging. Scenario-based analyses show that EV penetration reduces transport emissions more effectively when the grid relies on low-carbon sources and when charging is coordinated [11]. Vehicle-to-grid strategies can further mitigate emissions by optimizing charging and discharging according to grid carbon intensity [12]. Flow-based carbon accounting models highlight the importance of incorporating electricity generation sources to accurately assess EV-related emission reductions [13]. These findings underscore the importance of considering grid decarbonization when evaluating EV impacts.

The study is built upon the following research questions: “Do EVs truly have a CO2-reducing effect?” and “How do macroeconomic factors influence this relationship?” The main objective of this research is to empirically examine the impact of EV sales and the share of EVs in new vehicle sales on CO2 emissions in 15 high-income countries—classified according to the World Bank income group ranking—over the period 2010–2023. The analysis also considers variables such as GDP, urbanization rate, and fossil fuel consumption. The study employs a panel data approach within the frameworks of fixed effects and random effects models. By investigating the effects of both total EV sales and the share of EVs in new vehicle markets on CO2 emissions in high-income countries, this research provides valuable contributions to the existing literature. Analyzing not only the absolute sales figures of EVs but also their market share allows for a more detailed assessment of their impact on emissions. Moreover, the inclusion of economic and structural control variables—such as GDP, urbanization rate, and fossil fuel consumption—enables the isolation of the EV effect from other influencing factors. The application of both fixed and random effects models enhances the reliability of the findings and adds methodological diversity to the analysis. The remaining sections of the study are organized as follows: Section 2 and Section 3 present a review of the literature, while Section 4 describes the methodology used. Section 5 provides empirical findings, and Section 6 discusses the conclusions and implications based on these findings.

2. The Types of EV

EVs are defined as vehicles in which at least one of the propulsion systems is powered by an electric motor. Considering their power supply and propulsion configurations, EVs can be categorized into three main types: BEVs, whose energy source relies solely on batteries and whose propulsion system consists only of an electric motor; hybrid electric vehicles (HEVs), which utilize both gasoline/diesel and electricity as driving energy sources and have propulsion systems based on both internal combustion engines and electric motors; and fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs), which derive energy from both fuel cells and batteries but are propelled exclusively by electric motors [14].

HEVs can be categorized based on their refueling or charging methods. They are classified into conventional HEVs and grid-connected HEVs. Conventional HEVs can be further divided into micro, mild, and full HEVs depending on their energy usage levels. On the other hand, grid-connected HEVs may be either plug-in hybrid vehicles (PHEVs) or range-extended electric vehicles (REVs) [14].

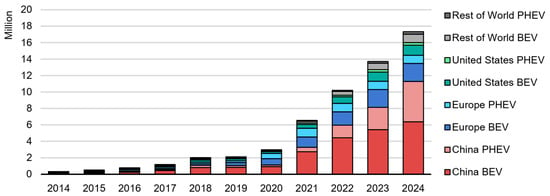

According to Figure 1, EV sales exceeded 17 million units in 2024, representing an increase of more than 25% compared to EV sales levels in 2023. In 2024, EVs accounted for more than 20% of total vehicle sales. China was the main driver of this growth, accounting for approximately two-thirds of global EV sales in 2024. The country’s EV sales recorded an annual growth rate of nearly 40% [15].

Figure 1.

Global Electric Car Sales (2014–2024) [16] (Note: Figure 1 includes new passenger cars only).

The rapid increase in EV sales has created a significant impact on the global automobile fleet. By the end of 2024, the electric car fleet reached approximately 58 million units. This figure accounts for around 4% of the total passenger car fleet and represents more than a threefold increase compared to the total number of EVs in 2021. Moreover, the global electric car stock in 2024 reduced daily oil consumption by more than one million barrels [15].

3. The Relationship Between EV and CO2 Emissions

According to projections by the International Energy Agency (IEA) [17] EVs can significantly aid global decarbonization efforts by 2035, provided that the electricity mix increasingly shifts toward low-carbon sources. EVs are widely regarded as a key component of the automotive sector’s transition toward lower greenhouse gas emissions, cleaner air, and enhanced global living standards. Compared with fossil fuels such as petrol, diesel, and natural gas, the use of electricity as an energy source in the transport sector contributes significantly to the reduction of global greenhouse gas emissions.

Onat et al. [18] conducted a comparative analysis across 50 U.S. states to evaluate BEVs, PHEVs, and HEVs, considering factors such as electricity generation, regional driving conditions, and production impacts. Their findings revealed that, based on the average electricity mix, BEVs had the lowest carbon intensity in 24 states, while HEVs were the most energy-efficient option in 45 states.

Moro & Lonza [19] examined greenhouse gas emissions from EVs across European Union countries, considering the carbon intensity of electricity generation. Their results indicate that, on average, EVs produce 50–60% lower emissions than gasoline vehicles. However, in countries relying heavily on coal or other fossil fuels for electricity generation, this advantage diminishes, and in some cases, the emission gap nearly disappears. Overall, the environmental benefits of EVs are highly contingent upon the cleanliness of a country’s electricity generation.

Sen et al. [20] analyzed the environmental impacts of EVs from a material footprint perspective using a multi-regional input–output life cycle assessment (MRIO-LCA) approach. The study found that, due to battery production, EVs consume more metals and energy than internal combustion engine vehicles during manufacturing. The intensive use of critical metals such as lithium, nickel, cobalt, copper, and aluminum increases environmental pressures at the production stage. Nevertheless, since EVs produce no direct emissions during operation, their overall greenhouse gas impact remains lower. Further research demonstrated that regions with higher shares of renewable energy achieve better environmental performance for EVs. Accordingly, the authors emphasized that battery recycling, life extension, and second-use strategies are critical for enhancing the sustainability of EVs.

Studies focusing on battery recycling and second-life applications have underscored their multifaceted benefits for the environmental sustainability of EVs. For instance, Jiang et al. [21], in a report on China, highlighted that battery recycling alleviates demand for critical raw materials and significantly reduces life-cycle CO2 emissions. In the U.S. context, Dunn et al. [22] examined the feasibility of implementing recycled content standards for lithium-ion batteries and discussed the potential implications of these targets for costs, policy design, and environmental outcomes. Similarly, Wesselkämper et al. [23] explored the economic and climatic benefits of reusing spent batteries in “second life” applications instead of direct recycling. Collectively, these studies indicate that battery recycling not only decreases raw material dependency but also plays a decisive role in reducing the carbon footprint of EVs, while policy support and technological infrastructure remain indispensable for the effectiveness of this process.

Tao et al. [24] analyzed the impact of EVs on CO2 emissions in 26 countries over the 2009–2023 period using an extended STIRPAT model. Their findings revealed that increasing EV adoption did not directly lead to emission reductions and even contributed to higher emissions in some countries. This outcome stems from the continued reliance on fossil fuels for electricity generation. The study highlights that the environmental advantages of EVs materialize most clearly when renewable energy penetration surpasses around 48% of the power mix. Moreover, renewable energy use and green technological innovation were found to reduce emissions, while economic growth and energy intensity increased them. Thus, the environmental benefits of EVs can only be fully realized in conjunction with a clean energy transition.

The potential emission reduction from EVs is estimated at around 90%, compared to approximately 25% for HEVs and 50–80% for PHEVs [25]. Several studies [25,26,27] have shown that the batteries, as the core component of EVs, have a significant impact on CO2 emissions. Specifically, the high energy consumption and emissions during battery manufacturing cause EVs to have higher CO2 emissions than conventional vehicles at the production stage. Dolganova et al. [26] emphasized that EV battery production results in greater consumption of metal and mineral resources, leading to increased emissions. Similarly, Verma et al. [25] found that although EVs have strong potential to reduce greenhouse gas emissions during use, they exhibit higher environmental impacts—such as metal consumption and human toxicity—than internal combustion engine vehicles during production, particularly in the manufacture of batteries and powertrains.

In this study, which aims to examine the impact of EVs on CO2 emissions in high-income country groups, explanatory variables include gross domestic product (GDP), urbanization rate, and fossil fuel consumption, alongside the EV variable. Hu et al. [28], who analyzed the effects of energy sources on economic growth and CO2 emissions in India between 1990 and 2018, found that fossil fuel consumption enhances economic growth but simultaneously increases CO2 emissions. Renewable energy and technological innovation contribute to economic growth but have a limited short-term effect on emission reduction. The causality results indicate a one-way linkage from energy consumption toward economic growth and carbon emissions, implying that India should intensify its efforts in renewable energy development and technological advancement to reach carbon neutrality. Studies such as Lu et al. [29], Dolge [30], González-Álvarez [31], Vogel [32], and Sarkodie [33] have generally identified a positive but regionally differentiated relationship between economic growth and CO2 emissions. Most analyses suggest that emissions tend to rise in the early stages of growth but slow down once income surpasses a certain threshold, due to the influence of green technologies and environmental policies. Similarly, Balza et al. [34], analyzing a panel dataset of 136 countries from 1970 to 2020, found that global economic growth is positively associated with CO2 emissions, providing partial evidence in favor of the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) hypothesis. According to their findings, while emissions decline beyond a certain income level in some developed countries, such a transition has not been observed in regions such as Latin America and the Caribbean.

The partial decoupling between economic activity and emissions observed in high-income countries underscores the growing importance of energy efficiency, renewable energy adoption, and low-carbon transport systems. Within this context, the widespread adoption of EVs emerges as a strategic instrument for reducing CO2 emissions in the transportation sector. Therefore, analyzing the impact of EVs on CO2 emissions in a sample of 15 high-income countries contributes to the literature on green growth and provides evidence-based insights for decarbonization-oriented transport policies.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Data and Method

This study investigates the impact of EVs on CO2 emissions using panel data for 15 high-income countries—Belgium, China, Germany, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Spain, Norway, the United Kingdom, the United States of America, Sweden, the Republic of Korea, New Zealand, Poland, and Portugal—over the period 2010–2023. The sample is restricted to high-income countries for two primary reasons. First, these economies exhibit higher levels of EV adoption, more mature charging infrastructure, and more reliable and consistent data availability. Second, high-income countries share relatively comparable structural characteristics in terms of industrial composition, environmental regulation, and energy system development. Limiting the analysis to this group enhances sample homogeneity and ensures that the estimated relationships are not confounded by large structural differences across income groups. The panel dataset consists of a total of 208 observations.

The dependent variable is per capita CO2 emissions (mt) (ln_CO2). The explanatory variables include the share of electric vehicles (ln_ev_share), electric vehicle sales (ln_ev_sale), gross domestic product (ln_gdp), urbanization rate (ln_urban), and fossil fuel consumption (% of total energy) (ln_fossil). Per capita CO2 emissions, GDP, urbanization, and fossil fuel consumption data were obtained from the World Bank, which harmonizes national statistics in line with internationally accepted reporting standards. Data on the share of electric vehicles and electric vehicle sales were sourced from the IEA. Both EV market share and EV sales were included in the model because they capture different dimensions of the electric vehicle transition. EV market share reflects the structural transformation of the overall vehicle fleet and therefore represents long-term effects, whereas EV sales measure short-term dynamics driven by annual new purchases, production processes, and energy demand. Including both variables simultaneously allows the analysis to distinguish between the long-run and short-run environmental impacts of EV adoption. Although the two variables are correlated, the examination of VIF values shows that multicollinearity remains within acceptable limits and does not distort the estimation results.

The urbanization rate is a fundamental socio-economic indicator that directly influences CO2 emissions through its impact on transportation demand, vehicle usage intensity, and energy consumption patterns. The literature frequently highlights the strong positive effect of urbanization on emission levels [35,36]. Moreover, the adoption of electric vehicles is predominantly concentrated in urban areas due to higher income levels, greater charging infrastructure availability, and better technological accessibility [37]. Therefore, including the urbanization rate as a control variable is essential for capturing structural differences in emission drivers and for indirectly accounting for the spatial distribution of EV adoption. All variables were transformed into their natural logarithmic forms to eliminate scale differences and to strengthen the assumption of linear relationships among variables.

The model is based on the following general panel data equation:

4.2. Model Specification

Empirical analysis employed both Fixed Effects (FE) and Random Effects (RE) frameworks. The FE model accounts for unobserved heterogeneity that remains constant over time within each country, effectively capturing country-specific characteristics. Conversely, the RE model treats these country-level differences as random and assumes no correlation with the explanatory variables. To determine the appropriate model specification, the Hausman test [38] was applied. The test result (χ2 = 65.55; p < 0.01) indicates that the RE estimator is inconsistent; therefore, the FE model was selected as the preferred specification for the empirical analysis.

The choice of the fixed effects (FE) estimator is grounded in both statistical and theoretical considerations. The Hausman test strongly rejects the consistency of the random effects estimator (χ2 = 65.55; p < 0.01), indicating that unobserved country-specific characteristics are correlated with the explanatory variables. The FE model effectively controls for time-invariant heterogeneity—including institutional quality, historical environmental policies, geographic conditions, and structural energy system characteristics—thereby minimizing omitted variable bias and providing more reliable estimates for policy interpretation.

4.3. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis

Table 1 presents the basic statistical properties and the correlation matrix of the variables used in the analysis. The mean values demonstrate that, after logarithmic transformation, the variables are comparable in scale and suitable for regression analysis.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Analysis Results.

An examination of the correlation matrix reveals a significant and negative relationship between ln_ev_share and ln_CO2 (r = −0.223; p < 0.01), while ln_ev_sale exhibits a positive association with ln_CO2 (r = 0.427; p < 0.01). Moreover, the ln_fossil variable demonstrates the strongest positive correlation with CO2 emissions (r = 0.526; p < 0.01). Although the relatively high correlation between ln_gdp and ln_urban (r = 0.802) raises the possibility of multicollinearity, this issue was thoroughly examined and found not to pose a concern. Specifically, the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values for all variables remained well below conventional critical thresholds, indicating that the observed correlation does not translate into harmful multicollinearity. To further verify this, an alternative specification excluding ln_urban was estimated, and the coefficient of ln_gdp remained stable in both magnitude and statistical significance. Moreover, the consistency of coefficient signs and significance levels across the baseline FE model, the Driscoll–Kraay estimations, and the country-clustered robust standard errors provides additional confirmation that the model’s estimates are not distorted by multicollinearity. Therefore, despite the relatively high pairwise correlation, no serious multicollinearity problem was found to compromise the robustness or reliability of the empirical results.

5. Results

5.1. Fixed and Random Effects Models

Table 2 presents the comparative results of the FE and RE models. According to the Hausman test results, the FE model was found to be the appropriate specification for this study.

Table 2.

Results of the FE and RE Models.

The findings indicate that the share of EVs significantly reduces CO2 emissions, whereas EV sales have a short-term increasing effect. These short-term effects are captured through the structure of the fixed effects model, which reflects the impact of annual changes in the explanatory variables on CO2 emissions within the same period. Because all variables are expressed in logarithmic form, the estimated coefficients represent short-run elasticities, indicating how year-to-year variations in EV share, EV sales, income, urbanization, and fossil fuel consumption translate into immediate changes in emissions. The positive short-run effect of EV sales is consistent with the initial carbon intensity of EV manufacturing and battery supply chains, which can temporarily increase emissions before long-term fleet renewal benefits materialize. Alternative specifications including lagged variables were tested to explore dynamic effects; however, due to the limited sample size, these models yielded unstable results and were therefore not retained. Consequently, the adopted specification appropriately reflects the short-term dynamics inherent in the annual panel data structure. Table 2 presents the comparative results of the FE and RE models. According to the Hausman test (χ2 = 65.55; p < 0.01), the RE model was found to be inconsistent, and therefore the FE model was preferred.

An 1% increase in the share of EVs leads to approximately a 0.13% reduction in CO2 emissions. However, a short-term increase in EV sales may elevate emissions due to supply chain effects and additional energy demand. As national income increases, CO2 emissions tend to decline, which can be attributed to higher environmental awareness and the adoption of green technologies in high-income countries. The finding that GDP growth contributes to lower CO2 emissions in high-income countries is consistent with a substantial body of empirical research. Some studies demonstrate that as economies reach higher income levels, investments in renewable energy, environmental technologies, and cleaner production processes expand, leading to reductions in emissions [34,39]. This pattern is also consistent with the Environmental Kuznets Curve hypothesis, which posits that environmental quality tends to improve once a certain income threshold is surpassed. Furthermore, rising income levels generally support the development and implementation of more ambitious environmental policies as well as the adoption of cleaner technologies. Therefore, the negative association between GDP and emissions observed in this study is theoretically coherent and well supported by previous empirical evidence. In contrast, higher urbanization rates are associated with increased emissions, as urban expansion typically raises transportation demand and energy consumption. Moreover, greater fossil fuel consumption directly amplifies emissions, confirming its role as one of the strongest determinants of carbon-intensive energy structures.

5.2. Robustness Checks

5.2.1. Driscoll–Kraay Robustness Test

The FE model was re-estimated using the Driscoll–Kraay robust standard error method [40], which simultaneously corrects for heteroskedasticity, autocorrelation, and cross-sectional dependence within the panel. The direction and significance of the coefficients remained consistent with the baseline model, particularly the negative effect of ln_ev_share and the positive effect of ln_ev_sale, both of which retained statistical significance. This confirms that the model results are stable and robust to different error structures.

5.2.2. Cluster-Robust Fixed Effects

To further validate the robustness of the results, the FE model was also estimated with clustered standard errors at the country level. This approach controls for variance heterogeneity across countries within the panel. The signs and significance levels of the coefficients are largely consistent with the Driscoll–Kraay estimates, indicating that the findings remain robust even when accounting for country-specific variations.

The results of the Driscoll–Kraay Robustness Test and the Cluster-Robust Fixed Effects test are presented in Table form in Appendix A.

6. Discussions and Conclusions

With climate change remaining a critical global concern, the transition toward cleaner transport technologies—such as fuel cell, hybrid, plug-in hybrid, and battery EVs that release only water vapor—has gained substantial momentum. However, whether EVs truly reduce CO2 emissions remains a central question motivating this research. This study examined the impact of EVs on CO2 emissions through a balanced panel data analysis covering 15 high-income countries over the period 2010–2023. Based on the Hausman test results, the FE model was identified as the most appropriate specification. The empirical findings reveal that the share of EVs exerts a negative (reducing) effect on CO2 emissions, whereas EV sales have a short-term positive (increasing) effect due to the carbon intensity of production processes and the existing energy mix. Furthermore, GDP growth appears to support environmental improvement, while urbanization and fossil fuel consumption contribute to higher emission levels. These results are broadly consistent with previous literature.

Although some of the findings align with established literature, this study offers several novel contributions. By jointly examining the effects of EV share and EV sales, the analysis distinguishes between the long-term structural effects of fleet electrification and the short-term emission impacts arising from EV production and supply chains—an aspect rarely explored simultaneously in previous research. Moreover, the use of an updated balanced panel covering 15 high-income countries over 2010–2023, combined with extensive robustness checks such as Driscoll–Kraay and country-clustered FE estimations, enhances the empirical credibility and policy relevance of the results. Therefore, while confirming theoretical expectations, the study advances the literature by providing a refined empirical perspective on the dual short- and long-term environmental effects of EV adoption.

Onat et al. [18], Moro & Lonza [19] and Xu et al. [41] found that a higher EV share supports long-term decarbonization in the transport sector. Conversely, Sen et al. [20] emphasized that the manufacturing of EVs may temporarily increase carbon emissions due to intensive resource use. Magazzino et al. [42] identified fossil fuel dependency as the strongest determinant of emissions, while Balza et al. [34] demonstrated that green economic transformation enables economic growth to contribute to emission reduction in developed countries. Overall, the findings suggest that the environmental impact of EVs is closely linked to the energy structure and the level of economic development.

It is important to note that these findings are derived exclusively from a sample of high-income countries. Therefore, the conclusion that the environmental impact of EVs is closely linked to the energy structure and the level of economic development should be understood within the context of advanced economies. The results cannot be directly generalized to middle- or low-income countries, where energy systems, industrial capacity, and the pace of EV adoption may differ substantially. In conclusion, to ensure a net reduction in CO2 emissions in the long term, the EV transition must be accompanied by a greater share of renewable energy in electricity generation and sustainable urban transport policies. Otherwise, in contexts where the shift to renewables remains insufficient, EVs may fall short of achieving the expected emission reductions in the short run [43].

Mandating that Electric Vehicle (EV) charging stations secure their energy supply directly through a certified Renewable Energy Certificate (REC) system is essential. This requirement guarantees that every kilowatt-hour (kWh) dispensed originates from clean sources, thereby directly mitigating the short-term emissions impact stemming from the existing carbon intensity of the energy grid. Furthermore, to immediately reduce the carbon footprint of the production chain, governments should implement tax incentives or subsidies linked to the mandated use of recycled materials in key EV manufacturing processes, particularly for battery components. This dual approach addresses both the operational and production-side emissions, aligning the EV transition with long-term decarbonization goals.

Future research could extend the analysis by incorporating variables such as the share of renewable energy generation, the density of charging infrastructure, and the proportion of fossil fuels in the energy mix, allowing for a more detailed assessment of the indirect emission effects of EVs. Furthermore, integrating institutional and regulatory factors-such as carbon taxation, EV incentives, and the stringency of environmental regulations-would provide valuable insights into the effectiveness of policy interventions in promoting sustainable decarbonization.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.Y.B. and M.B.B.; methodology, B.Y.B.; validation, B.Y.B. and M.B.B.; formal analysis, B.Y.B.; investigation, B.Y.B. and M.B.B.; data curation, B.Y.B.; writing—original draft preparation, B.Y.B. and M.B.B.; visualization, B.Y.B. and M.B.B.; writing—review and editing, M.B.B.; supervision, B.Y.B. and M.B.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support was received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available in Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/H8FOYF.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BEV | Battery Electric Vehicle |

| CO2 | Carbon Dioxide |

| EV | Electric Vehicle |

| FE | Fixed Effects |

| FCEV | Fuel Cell Electric Vehicle |

| GDP | Gross Domestic Product |

| HEV | Hybrid Electric Vehicle |

| PHEV | Plug-in Hybrid Vehicle |

| RE | Random Effects |

| REV | Range-extended Electric Vehicle |

| WTW | Well to Wheel |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Driscoll-Kraay Test Results.

Table A1.

Driscoll-Kraay Test Results.

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. Err. | t | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ln_ev_share | −0.1262 | 0.0538 | −2.34 | 0.036 |

| ln_urb | 1.7748 | 0.5982 | 2.97 | 0.011 |

| ln_gdp | −1.0069 | 0.2085 | −4.83 | 0.000 |

| ln_fos | 1.4770 | 0.1383 | 10.68 | 0.000 |

| ln_ev_sale | 0.1325 | 0.0308 | 4.30 | 0.001 |

| pop | 0.0954 | 0.0785 | 1.22 | 0.246 |

| _cons | −0.7091 | 0.7432 | −0.95 | 0.357 |

Table A2.

Cluster-Robust Fixed Effects Test Results.

Table A2.

Cluster-Robust Fixed Effects Test Results.

| Variable | Coefficient | Std. Error | t | p-Value | 95% Conf. Int. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ln_ev_share | −0.1849 | 0.1149 | −1.61 | 0.132 | [−0.4331, 0.0633] |

| ln_urb | 1.9991 | 0.5183 | 3.86 | 0.002 | [0.8794, 3.1189] |

| ln_gdp | −1.1736 | 0.1929 | −6.08 | 0.000 | [−1.5904, −0.7568] |

| ln_fos | 1.1646 | 0.2547 | 4.57 | 0.001 | [0.6143, 1.7148] |

| ln_ev_sale | 0.1776 | 0.0634 | 2.80 | 0.015 | [0.0406, 0.3145] |

| pop | 0.0925 | 0.0729 | 1.27 | 0.227 | [−0.0650, 0.2500] |

| _cons | 0.9032 | 1.0015 | 0.90 | 0.384 | [−1.2605, 3.0669] |

| Year | Coefficient | Std. Error | t | p-value | 95% CI |

| 2011 | −0.0020 | 0.0276 | −0.07 | 0.945 | [−0.0615, 0.0576] |

| 2012 | −0.0905 | 0.0143 | −6.31 | 0.000 | [−0.1215, −0.0596] |

| 2013 | −0.1074 | 0.0225 | −4.78 | 0.000 | [−0.1560, −0.0588] |

| 2014 | −0.0916 | 0.0263 | −3.48 | 0.004 | [−0.1484, −0.0348] |

| 2015 | −0.0698 | 0.0217 | −3.21 | 0.007 | [−0.1167, −0.0228] |

| 2016 | −0.0452 | 0.0354 | −1.28 | 0.224 | [−0.1215, 0.0312] |

| 2017 | −0.0378 | 0.0512 | −0.74 | 0.474 | [−0.1485, 0.0729] |

| 2018 | −0.0255 | 0.0569 | −0.45 | 0.661 | [−0.1484, 0.0973] |

| 2019 | −0.1224 | 0.0947 | −1.29 | 0.219 | [−0.3268, 0.0821] |

| 2020 | −0.0058 | 0.1389 | −0.04 | 0.967 | [−0.3059, 0.2944] |

| 2021 | 0.0888 | 0.1657 | 0.54 | 0.601 | [−0.2690, 0.4467] |

| 2022 | 0.0494 | 0.1500 | 0.33 | 0.747 | [−0.2746, 0.3733] |

| 2023 | 0.3291 | 0.1334 | 2.47 | 0.028 | [0.0409, 0.6173] |

When country and year fixed effects are controlled for, the coefficient of EV share (ln_ev_share) loses its statistical significance, indicating that the increase in EV penetration alone is not a decisive factor in reducing CO2 emissions. This suggests that broader year-specific shocks-such as national policies, the COVID-19 pandemic, or changes in energy systems-may play a more substantial role. In contrast, EV sales (ln_ev_sale) remain positive and significant, implying that EV adoption does not reduce emissions in the short run and may even contribute to higher emissions in contexts where electricity generation is still dependent on fossil fuels. GDP exhibits a negative relationship with CO2 emissions, which aligns with improvements in environmental efficiency and technological advancement in high-income countries. Fossil fuel consumption remains the strongest positive determinant of emissions, while urbanization also shows a positive effect, indicating that the expansion of urban areas tends to increase energy demand and carbon output.

References

- Urooj, A.; Nasir, A. Review of intelligent energy management techniques for hybrid electric vehicles. J. Energy Storage 2024, 92, 112132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, H.; Li, M.; Hensher, D.A.; Xie, C.; Gu, Z.; Zheng, Y. Strategizing sustainability and profitability in electric Mobility-as-a-Service (E-MaaS) ecosystems with carbon incentives: A multi-leader multi-follower game. Trans. Res. Part C Emer. Technol. 2024, 166, 104758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA. Total CO2 Emissions. 2025. Available online: https://www.iea.org/world/emissions (accessed on 10 August 2025).

- Solaymani, S. CO2 emissions patterns in 7 top carbon emitter economies: The case of transport sector. Energy 2019, 168, 989–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, J.; Guan, D.; Chalvatzis, K.; Huo, H. Assessment of electrical vehicles as a successful driver for reducing CO2 emissions in China. Appl. Energy 2016, 184, 995–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.G.; Lim, H.; Lee, J. Decarbonizing road transport in Korea: Role of electric vehicle transition policies. Trans. Res. Part D Trans. Environ. 2024, 128, 104084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, C.; Liu, W.; He, H.; Chau, K.T. Health-conscious energy management for fuel cell vehicles: An integrated thermal man-agement strategy for cabin and energy source systems. Energy 2025, 333, 137330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, N.; Prasad, K.; Lie, T.T. The electric vehicle: A review. Int. J. Electr. Hybrid Veh. 2017, 9, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albatayneh, A.; Assaf, M.N.; Alterman, D.; Jaradat, M. Comparison of the overall energy efficiency for internal combustion engine vehicles and electric vehicles. Rigas Teh. Univ. Zinat. Raksti 2020, 24, 669–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanguesa, J.A.; Torres-Sanz, V.; Garrido, P.; Martinez, F.J.; Marquez-Barja, J.M. A review on electric vehicles: Technologies and challenges. Smart Cities 2021, 4, 372–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, W.M. A scenario-based approach to predict energy demand and carbon emission of electric vehicles on the electric grid. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 77300–77310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Waldron, J.; Rodrigues, L.; Gillott, M.; Naylor, S.; Shipman, R. The role of electric vehicle charging technologies in the decarbonisation of the energy grid. Energies 2022, 15, 2447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Chao, H.; Shi, W.; Li, N. Towards carbon-free electricity: A flow-based framework for power grid carbon accounting and decarbonization. Energy Convers. Econ. 2024, 5, 396–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chau, K.T.; Li, W. Overview of electric machines for electric and hybrid vehicles. Int. J. Veh. Des. 2014, 64, 46–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEA. Global Energy Review 2025; IEA: Paris, France, 2025; Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-energy-review-2025 (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- IEA. Global EV Outlook 2025; IEA: Paris, France, 2025; Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2025 (accessed on 11 August 2025).

- IEA. Global EV Outlook 2024: Outlook for Emissions Reductions; IEA: Paris, France, 2024; Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2024 (accessed on 1 August 2025).

- Onat, N.Ç.; Kucukvar, M.; Tatari, O. Conventional, hybrid, plug-in hybrid or electric vehicles? Life cycle assessment based comparison of energy and greenhouse gas emissions. Appl. Energy 2015, 150, 36–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moro, A.; Lonza, L. Electricity carbon intensity in European Member States: Impacts on GHG emissions of electric vehicles. Trans. Res. Part D Trans. Environ. 2018, 64, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, B.; Onat, N.C.; Kucukvar, M.; Tatari, O. Material footprint of electric vehicles: A multiregional life cycle assessment. J. Clean Prod. 2019, 209, 1033–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, R.; Wu, C.; Feng, W.; You, K.; Zhou, G.; Liu, L.; Chemg, H.M. Impact of electric vehicle battery recycling on reducing raw material demand and battery life-cycle carbon emissions in China. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, J.; Kendall, A.; Slattery, M. Electric Vehicle Lithium-Ion Battery Recycled Content Standards for the US—Targets, Costs, and Environmental Impacts. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 185, 106488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wesselkämper, J.; Hendrickson, T.P.; Lux, S.; von Delft, S. Recycling or Second Use? Supply Potentials and Climate Effects of End-of-Life Electric Vehicle Batteries. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2025, 59, 15751–15765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, M.; Lin, B.; Poletti, S. Deciphering the impact of electric vehicles on carbon emissions: Some insights from an extended STIRPAT framework. Energy 2025, 316, 134473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, S.; Dwivedi, G.; Verma, P. Life cycle assessment of electric vehicles in comparison to combustion engine vehicles: A review. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 49, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolganova, I.; Patrício, J.; Castellani, V. A review of life cycle assessment studies of electric vehicles with a focus on resource use. Resources 2020, 9, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farzaneh, F.; Jung, S. Lifecycle carbon footprint comparison between internal combustion engine versus electric transit vehicle: A case study in the U.S. J. Clean Prod. 2023, 390, 136111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, K.; Raghutla, C.; Chittedi, K.R.; Zhang, R.; Koondhar, M.A. The effect of energy resources on economic growth and carbon emissions: A way forward to carbon neutrality in an emerging economy. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 298, 113448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, F.; Ma, F.; Feng, L. Carbon dioxide emissions and economic growth: New evidence from GDP forecasting. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2024, 205, 123464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolge, M. Economic growth in contrast to GHG emission reduction: The case of the European Union’s Green Deal targets. Environ. Sci. Policy 2021, 124, 144–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Álvarez, A. CO2 emissions, energy consumption, and economic growth: Evidence from a dynamic heterogeneous panel model. Energy Econ. 2023, 120, 106574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, J. GDP decoupling in high-income countries: Assessing the limits of green growth. One Earth 2023, 6, 100174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkodie, S.A.; Owusu, P.A.; Taden, J. Green growth assessment across 203 economies: Trends and insights. Sustain. Horiz. 2024, 10, 100083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balza, L.H.; Heras-Recuero, L.; Matías, D.; Yépez-García, R.A. Green or Growth? Understanding the Relationship Between Economic Growth and CO2 Emissions; (IDB Technical Note No. 2930); Inter-American Development Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2024; pp. 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poumanyvong, P.; Kaneko, S. Does urbanization lead to less energy use and lower CO2 emissions? A cross-country analysis. Energy Policy 2010, 38, 6309–6316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liddle, B. Urbanization and carbon emissions: The role of structural change. Appl. Energy 2013, 104, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Selamat, M.H.; Lee, S.N. The impact of policy incentives on the purchase of electric vehicles by consumers in china’s first-tier cities: Moderate-mediate analysis. Sustainability 2025, 17, 5319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausman, J.A. Specification tests in econometrics. Econometrica 1978, 46, 1251–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadorsky, P. Do urbanization and industrialization affect energy intensity in developing countries? Energy Econ. 2013, 37, 52–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driscoll, J.C.; Kraay, A.C. Consistent covariance matrix estimation with spatially dependent panel data. Rev. Econ. Stat. 1998, 80, 549–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Sharif, A.; Shahbaz, M.; Dong, K. Have electric vehicles effectively addressed CO2 emissions? Analysis of eight leading countries using quantile-on-quantile regression approach. Sustain. Prod. Consump. 2021, 29, 1205–1214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magazzino, C.; Mele, M.; Schneider, N.; Sarkodie, S.A. Waste generation, wealth and GHG emissions from the waste sector: Is Denmark on the path towards circular economy? Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 755, 142510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yengil Bülbül, B.; Baydar, M.B. Decarbonizing Transport: Cross-Country Evidence on Electric Vehicle Use and Carbon Emissions. In Proceedings of the 2nd Global Conference on Management and Economics, Milan, Italy, 3 October 2025. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the World Electric Vehicle Association. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).