Abstract

This work focuses on finding frequent patterns in continuous flow network traffic Big Data using incremental frequent pattern mining. A newly created Zeek Conn Log MITRE ATT&CK framework labeled dataset, UWF-ZeekData24, generated using the Cyber Range at The University of West Florida, was used for this study. While FP-Growth is effective for static datasets, its standard implementation does not support incremental mining, which poses challenges for applications involving continuously growing data streams, such as network traffic logs. To overcome this limitation, a staged incremental FP-Growth approach is adopted for this work. The novelty of this work is in showing how incremental FP-Growth can be used efficiently on continuous flow network traffic, or streaming network traffic data, where no rebuild is necessary when new transactions are scanned and integrated. Incremental frequent pattern mining also generates feature subsets that are useful for understanding the nature of the individual attack tactics. Hence, a detailed understanding of the features or feature subsets of the seven different MITRE ATT&CK tactics is also presented. For example, the results indicate that core behavioral rules, such as those involving TCP protocols and service associations, emerge early and remain stable throughout later increments. The incremental FP-Growth framework provides a structured lens through which network behaviors can be observed and compared over time, supporting not only classification but also investigative use cases such as anomaly tracking and technique attribution. And finally, the results of this work, the frequent itemsets, will be useful for intrusion detection machine learning/artificial intelligence algorithms.

1. Introduction

Massive amounts of data are generated from network traffic, for example, logs, system alerts, etc., making it difficult to identify threats or anomalies without advanced data mining techniques. This work focuses on using association rule mining (ARM), a data mining technique introduced by Agrawal in 1993 [1], to find recurring associations in network attack traffic Big Data. In 1994, Agrawal and Srikant (1994) [2] developed the Apriori algorithm, a well-accepted algorithm for finding frequent itemsets and association rules. However, a major limitation of this algorithm was the generation of numerous candidate itemsets, which required multiple scans of a database, substantial storage space, and considerable computational time [3], especially when dealing with massive amounts of data, for example, when dealing with data generated from network traffic.

To address the challenges of the Apriori algorithm, Han et al. (2000) [3] developed the Frequent Pattern (FP)-Growth algorithm and a compact data structure—a frequent pattern tree or FP-tree—to collect all frequent items from a transaction. The FP-tree algorithm did not require multiple scans of the database. The dataset needed to be scanned only twice—the first time for finding frequent itemsets and the second time for constructing the FP-tree [4]. However, the traditional FP-Growth tree [3] finds patterns in static data. In this era of Big Data, when dealing with continuously generated network data, the challenge is to be able to find patterns in a continuous data stream, and hence, there is a need for incremental FP (IFP)-Growth mining.

This work focuses on finding frequent patterns in continuous flow network traffic Big Data using incremental frequent pattern mining. While FP-Growth is effective for static datasets, its standard implementation does not support incremental mining, which poses challenges for applications involving continuously growing data streams, such as network traffic logs. To overcome this limitation, an incremental FP-Growth approach is adopted for this work.

To mimic continuous flow data, the dataset was divided into staged partitions, allowing rules and frequent itemsets to be extracted incrementally without reprocessing the entire dataset. The mining process begins with an initial subset (e.g., 50% of the total dataset) to construct the base FP-tree and identify the initial set of frequent patterns. As each new increment (e.g., 60%, 70%, etc.) is added, only the new portion is scanned, and updates are applied to the existing tree structure. During each increment, support counts of previously discovered itemsets are updated, and new patterns are integrated where necessary. This reduces the computational burden and supports continuous learning from data as it arrives. Association rules are generated at each stage and filtered using specific criteria: only rules above a certain support threshold, confidence equal to 100%, and lift greater than 1.0 are retained. Additionally, a subset/superset pruning mechanism was applied to eliminate generalized patterns that are subsumed by more specific and informative rules. This methodology enabled efficient, adaptive mining from large-scale and evolving datasets, and is particularly suited for network intrusion detection where behavioral signatures evolve over time.

A Zeek Conn Log [5] MITRE ATT&CK [6] framework labeled network attack dataset, UWF-ZeekData24 [7,8], generated using the Cyber Range at The University of West Florida (UWF) [9], was used for this study. This dataset is composed of seven different MITRE ATT&CK tactics [6] and benign data. Zeek’s Conn log files track the protocols and associated information, such as IP addresses, durations, two-way bytes, states, packets, and tunnel information. In short, the Conn log files provide all the data regarding the connection between two points [5].

Incremental frequent pattern mining, by its very nature, also generates the feature subsets useful in understanding the nature of the individual attack tactics, and hence, this work also explains the nature of the individual MITRE ATT&CK tactics in terms of the important features or feature subsets that could be used to identify each tactic. This could be important information in developing any future machine learning-based intrusion detection system.

The novelty of this work is in showing how incremental FP-Growth can be used efficiently on continuous flow network traffic, or streaming network traffic data, where no rebuild is necessary when new transactions are scanned and integrated. The tree structure can be extended without having to be modified globally.

The rest of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 presents the related works; Section 3 explains the dataset; Section 4 explains the FP-Growth algorithm, including the experiment; Section 5 presents the results and discussion; Section 6 presents the conclusions, and Section 7 presents the future works.

2. Related Works

Ref. [10] designed an incremental association rule mining algorithm using a new Incremental Conditional Pattern tree (ICP-tree) and a compact sub-tree, called the Fast Incremental Updating Frequent Pattern growth algorithm (FIUFP-Growth). Considering an original database and newly inserted data, they analyzed four situations that may arise: (i) An itemset is frequent in the original database and also in the newly inserted data; (ii) an itemset is frequent in the original database but is not frequent in the newly inserted data; (iii) an itemset is not frequent in the original database but is frequent in the newly inserted data; and (iv) an itemset is not frequent in the original database and in the newly inserted transactions.

Ref. [11] mentioned that scanning the database demands checking if the new itemsets are frequent over the entire database. Moreover, thresholds are one of the most popular problems in most learning techniques. In ARM, knowledge discovery relies on specific thresholds, so any changes in the thresholds indicate that the discovered knowledge does not reflect the database anymore [11].

A similar kind of experiment has been performed on the mushroom dataset and the T10|4D100K dataset [12]. It also presented the idea of a data mining view, illustrating how this idea could be employed to materialize the results of previously mined queries in a materialized data mining view [12].

There was another approach to store the itemsets that are not large at present, but may become large itemsets after updating the database, so that the cost of processing the updated database can be reduced. Moreover, ref. [13] discusses cases where the large itemsets can be obtained without scanning the original database. Experimental results show their algorithms outperform other algorithms, especially when the original database does not need to be checked in their algorithms [13].

An adaptive algorithm (like Apriori) was proposed for incremental mining by [14]. Ref. [14] attempts to categorize different types of increments. Primarily, the increments could represent similar business trends as before or significantly different trends. It must be noted that these rules found from the increment alone may not have the required support in the updated database [14].

Ref. [15] presents a systematic survey of the existing algorithms for generating association rules from a dataset. Several dataset scans and the number of candidate itemsets generated are the two significant challenges of the rule mining problem. Several algorithms addressing the issue of the rule mining problem are reported. Algorithms designed based on Agrawal’s support–confidence framework treat the rule mining problem as a single-objective problem [15].

A performance comparison of the DB-tree and PotFP-tree with the original FP-tree and Apriori algorithms was conducted by [16]. All four algorithms were implemented and run on the same datasets generated using the resource code for generating synthetic datasets. The correctness of the implementations was confirmed by checking that the frequent itemsets generated for the same dataset by the four algorithms were the same [16].

Ref. [17] presents an implementation of the FP-Growth algorithm, which contains two methods for efficiently projecting an FP-tree. As the experimental results show, this implementation clearly outperforms Apriori and Eclat, even in highly optimized versions. However, the performance of the two projection methods, especially with regard to why the second is sometimes much slower than the first, needs further investigation [17].

Additionally, zero-day attack detection is the most challenging task in the cybersecurity domain [18]. Most of the works that have been performed on attack detection are primarily with respect to known attack detection, but very few are considered unknown or zero-day attack detection. Ref [18] focused on a zero-day attack detection system. The proposed framework is divided into two phases: (1) signature extraction and (2) zero-day attack detection. Two types of network traffic were used in this work: CICIDS2017 and real-time data (RTNITP23). The unknown variants of the DoS/DDoS attack detection have been the main concern. The two primary modules of the proposed framework are (i) DoS/DDoS attack signature extraction and (ii) unknown variants of the DoS/DDoS (high-volume) attack detection. Two categories of network traffic data are utilized: RTNITP24 and CICIDS2017 data.

In [19], the Painting-Growth and N Painting-Growth algorithms obtain all frequent itemsets only through the two-item permutation sets of transactions, being simple in principle and easy to implement, and they only scan the database once [19].

3. The Dataset: UWF-ZeekData24

This study utilizes the UWF-ZeekData24 dataset [7,8], a mission-focused network telemetry resource developed through structured data collection in a controlled cyber experimentation environment. Sourced using Zeek [5], an open-source network monitoring framework, the dataset comprises detailed connection records enriched with ground-truth adversarial labels. These labels are aligned with the MITRE ATT&CK® framework [6], allowing for structured behavioral analysis of cyber threats across various stages of the intrusion lifecycle. Unlike synthetic or public competition datasets, UWF-ZeekData24 [7] was designed to mirror realistic enterprise traffic patterns under both benign and malicious conditions, enabling robust evaluation of anomaly detection and pattern mining algorithms.

The dataset contains benign data as well as seven different ATT&CK-defined tactics: credential access [20], reconnaissance [21], initial access [22], privilege escalation [23], persistence [24], defense evasion [25], and exfiltration [26]. Within each tactic-specific subset, network sessions are represented as tabular records including features for protocol type, connection duration, byte/packet counts, service interactions, and logical groupings of source and destination IP addresses. To facilitate association rule mining and categorical analysis, these features were discretized into bins using fixed ranges derived from domain-informed thresholds and statistical heuristics.

The MITRE ATT&CK framework knowledge base classifies adversarial behavior using a matrix of tactics and techniques grounded in real-world incident observations. For example, the reconnaissance tactic [21] includes techniques like active port scanning (T1595) and network information gathering (T1590), which often appear in network data as high-frequency short-lived connections or repeated interactions with unresponsive endpoints.

By labeling each record with these behavior tags, UWF-ZeekData24 [7] enables direct correlation between mined patterns and adversary intent. In this dataset, the reconnaissance tactic has 58,095 network events. Data from tactics such as credential access [20] and privilege escalation [23] similarly offer broad coverage of targeted activities. Credential access has 871,188 recorded network events, while privilege escalation has 6048 recorded network events. Amongst the other tactics, persistence and defense evasion have the same number of recorded events as privilege escalation, while initial access has more events, recording 106,602. Exfiltration has the least number of recorded events, that is, 559. And, this dataset has 930,318 recorded events of benign data, which is regular network traffic that does not have any attacks.

This scale, combined with binning and ATT&CK tagging, enables fine-grained analysis of how threat behaviors evolve and repeat across diverse conditions. The tactic dataset serves not only as a platform for mining association rules but also for benchmarking detection systems and understanding adversarial progression within a structured framework.

4. The Experiment: Incremental FP-Growth Mining

The first sub-section of Section 4 presents the overall design of incremental FP-Growth mining; the second sub-section presents an example of incremental FP-Growth mining; and the third sub-section presents incremental FP-Growth mining as applied to UWF-ZeekData24 [7].

4.1. Incremental FP-Growth Mining

The goal of this approach is to continuously extract meaningful patterns from a growing dataset without having to restart the entire mining process each time new data becomes available. This is achieved by performing data preprocessing with binning, pattern extraction using FP-Growth, and incremental updating using the Fast Update 2 (FUP2) strategy. FUP2 allows dynamic datasets where both new transactions can be inserted and existing transactions can be deleted.

- Step 1: Data Preparation: Binning and Encoding

For preprocessing, binning was applied. And the following steps were applied:

- For continuous numeric features, binning techniques were used to divide the data into labeled intervals. Each numeric value was assigned to a specific bin, such as bin zero or bin one, depending on where it falls in the range.

- For categorical features, apply encoding using methods such as string indexing. Each unique category was assigned a label.

- Store a mapping of all bins and encoding assignments so that future batches of data can be processed consistently.

The result is a dataset of transactions where each entry contains labeled items like “duration equals bin one” or “connection state equals index zero”.

- Step 2: Run Initial FP-Growth

With the binned data, the FP-Growth algorithm was run to identify frequent itemsets and generate association rules. Each rule included the following metrics: support, confidence, and lift.

Support is a count of how often a given itemset appears in a dataset, while confidence is how frequently items in Y appear in transactions that contain X [4,27,28].

An association rule, in the form X ⇒ Y, implies that a dataset, D, has support, s, where s is the percentage of transactions in D that contain X ∪ Y (that is, contain both X and Y), or the probability, P(X ∪ Y) [4,27,28].

The association rule X ⇒ Y has confidence c in the transaction set D, where c is the percentage of transactions in D containing X that also contain Y, or the conditional probability, P(X|Y) [4,27,28].

Association rules with high confidence and strong support are referred to as strong rules [1,4,27,28]. In Big Data, however, the support may not be very high. The higher the confidence, however, the more likely it is for Y to be present in transactions that contain X.

- Step 3: Incremental Update Process

The first batch contained 50% of the data. Each new increment was an additional 10% of the data. First, the frequent itemsets were generated from 50% of the data. Then, for each new batch, we calculated how often the original frequent itemsets occur within it. Also, the previously infrequent itemsets were re-assessed to see if they now meet the minimum support threshold. Use the FUP2 strategy to determine how the itemsets should be updated:

- If an itemset was frequent before and remains frequent, keep it.

- If an itemset was previously infrequent but has now become frequent with the addition of the new batch, add it to the frequent itemsets.

- If an itemset was frequent before but now falls below the support threshold, remove it from the frequent itemsets.

With the updated support counts, recalculate the association rules. Remove rules that no longer meet the minimum confidence or lift thresholds and add any new rules that now qualify.

- Step 4: Continuing the Cycle and the Final Outcome

Repeat the preprocessing, scanning, and updating steps for each new data batch. This allows you to maintain an up-to-date collection of frequent patterns and rules without restarting the mining process each time.

By the end of the process, you will have a comprehensive set of association rules that reflect the most current state of your data. All rules are fully interpretable, since the binning and encoding mappings are retained and applied consistently. This combined method efficiently handles growing datasets while preserving human readability and analytical value.

4.2. Experimental Design of Incremental FP-Growth: An Example

To illustrate the FP-Growth algorithm and its incremental extension, we present a complete walkthrough of tree construction, mining, and update via an additional transaction. A minimum support threshold of 3 is used. Suppose we have the initial set of transactions as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Initial set of transactions.

- Step 1: Computing Itemset Frequencies

First, we compute item frequencies as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Itemset frequencies.

Item D is discarded for being infrequent (shown by the ❌). The remaining items are sorted by global frequency: B (5), E (4), A (3), and C (3).

- Step 2: Sort Transaction Table

Each transaction is filtered and sorted by frequency order, as shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Sorted in frequency order.

- Step 3: FP-Tree Construction

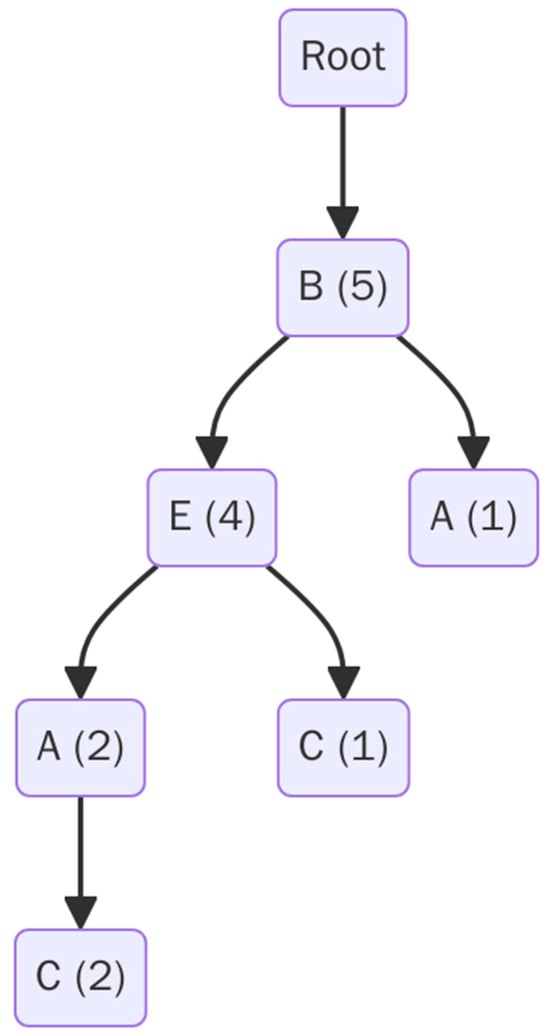

The FP-Tree is constructed from the sorted transactions, as per the header table presented in Table 4. Each path is inserted into the tree, with frequency counters incremented for each item. The resulting tree is shown in Figure 1.

Table 4.

Initial header table.

Figure 1.

FP-Tree after initial construction.

- Step 4: Frequent Itemsets (Initial Mining)

Using a minimum support of 3, Table 5 presents the frequent itemsets mined.

Table 5.

Frequent itemset after initial mining.

- Step 5: Incremental Update: Adding a New Transaction

We added a new transaction. After filtering and sorting based on global frequency order → E, A, C.

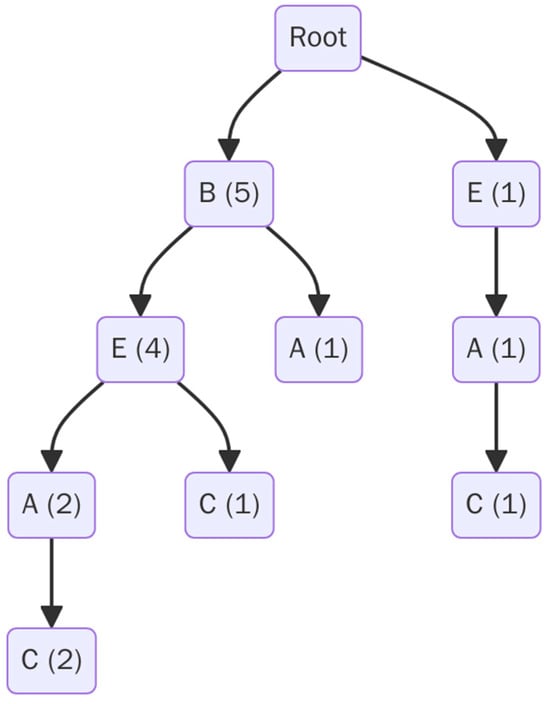

This introduces a new prefix path not previously seen in the FP-tree. The transaction E → A → C is added as a new branch under the root, as presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Updated FP-tree after incremental update (T6 = A, C, E).

As can be seen from Table 6, the header table is dynamically extended to include the newly added nodes without changing the overall structure.

Table 6.

Header table after incremental update.

- Step 6: Updated Frequent Itemsets

After incrementing the FP-tree, new support counts are computed, as shown in Table 7. The itemset {A, C} crosses the support threshold and is now frequent. This is a direct result of the newly added transaction. No previously frequent itemsets are lost. Table 8 presents the final impact of the addition or incremental addition.

Table 7.

Updated frequent itemsets.

Table 8.

Impact of incremental addition.

4.2.1. Discussion and Implications of Incremental FP-Growth as Illustrated in the Example

This example highlights several important properties of incremental FP-Growth:

- Efficiency: Only the new transaction was scanned and integrated. No rebuild was required.

- Compactness: The tree structure was extended, not modified globally.

- Scalability: The approach supports continuous learning and streaming scenarios.

- Pattern Evolution: New patterns such as {A, C} become frequent over time.

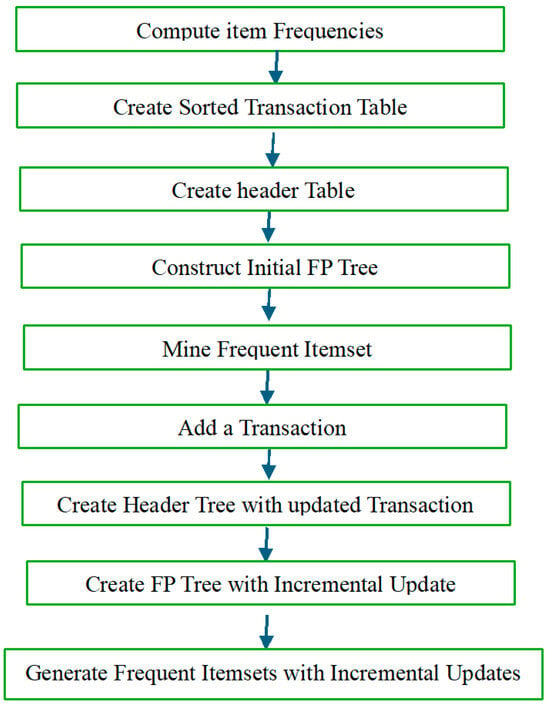

Hence, incremental updates are particularly useful in domains such as intrusion detection, where real-time adaptability is essential. A summary of the steps used in this example is presented in Figure 3. The incremental FP-Growth technique successfully adapts pattern mining in evolving datasets.

4.2.2. Conclusion from the Example of Incremental FP-Growth

Figure 3 presents a flowchart showing the core stages of incremental FP-Growth. The incremental FP-Growth technique successfully adapts to new transactions by locally extending the FP-tree and updating support counts in-place. This preserves efficiency, reduces redundancy, and facilitates scalable pattern mining in evolving datasets.

Figure 3.

Flowchart of core stages of incremental FP-Growth.

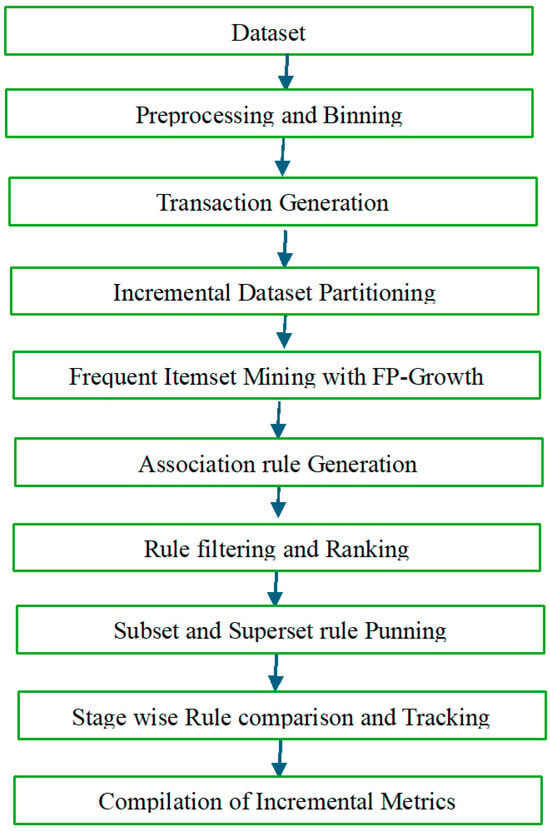

4.3. Experimental Design of Incremental FP-Growth Mining Using UWF-ZeekData24

This section presents the process used for UWF-ZeekData24 [7]. The experimental procedure follows a sequential pipeline that begins with binning and encoding and ends with rule extraction and comparative analysis. The preprocessing and binning stages convert raw numerical and categorical features into symbolic bins suitable for pattern mining. Figure 4 presents a flowchart of incremental FP-Growth as applied to UWF-ZeekData24.

Figure 4.

Incremental FP-Growth as applied to UWF-ZeekData24.

- Step 1. Transaction Generation

After preprocessing, each network event is encoded into a set of discrete feature-value tokens. These sets of tokens, each representing a row of the dataset, are treated as individual transactions. Only relevant features that pertain to the MITRE ATT&CK technique under investigation are included to ensure that the mined rules are both concise and behaviorally meaningful.

- Step 2. Incremental Dataset Partitioning

The full transactional dataset is divided into increments of 10% for analysis. The increments span from 50% to 100% of the dataset, with six separate experiments corresponding to 50%, 60%, 70%, 80%, 90%, and 100% dataset coverage. This partitioning simulates the evolution of attack behaviors over time and supports longitudinal rule discovery.

- Step 3. Frequent Itemset Mining with FP-Growth

For each increment, the FP-Growth algorithm is executed with a fixed minimum support threshold of 1%. This stage produces sets of frequent itemset combinations that meet the support requirement, serving as the foundation for subsequent association rule generation.

- Step 4. Association Rule Generation

From the mined frequent itemsets, association rules are derived using a minimum confidence threshold of 50%. Each rule is formatted as an implication (e.g., A → B), where A is the antecedent and B is the consequent. For each rule, key statistical metrics are computed, including support, confidence, and lift.

- Step 5. Rule Filtering and Ranking

To ensure interpretability and significance, the association rules undergo multi-level filtering. The criteria include the following:

- Confidence equal to 100%.

- Lift greater than 1.

- Belonging to the top 48 rules by support.

This step isolates the most meaningful and behaviorally consistent rules, which are retained for further analysis.

- Step 6. Subset and Superset Rule Pruning

Structural redundancy is reduced by removing rules that are strict subsets of more complex, higher-confidence rules. For each stage, subset rules are pruned in favor of their more descriptive supersets, which incorporate additional features or conditions. This pruning mechanism ensures that the final rule set reflects high granularity without duplicating logic.

- Step 7. Increment-Wise Rule Comparison and Tracking

All surviving rules are indexed by increment and compared across increments to assess their persistence or transformation. This analysis allows for identifying the following:

- Rules that consistently appear across all increments.

- Rules that emerge only in later stages.

- Rules that evolve structurally by acquiring additional antecedents.

This provides insights into both foundational and late-emerging behavioral trends.

- Step 8. Compilation of Incremental Metrics

Each increment is evaluated based on several key performance indicators, such as the following:

- Total number of mined rules.

- Count of high-confidence (100%) rules.

- Average and maximum support values.

- Distribution of lift values.

- Frequency of rule subset elimination.

These metrics inform the quantitative assessment of rule stability, quality, and discovery dynamics over time.

4.3.1. Data Preparation and Transformation

To ensure that the dataset was in a format suitable for association mining, the following preprocessing steps were taken:

- Exclusion of metadata columns: Non-informative features such as timestamps, unique identifiers, and raw IP addresses were excluded to focus on semantically relevant features.

- Handling missing values: Missing and null values in the raw data file are replaced with 0 to ensure that the data is usable for binning and processing.

- Removal of duplicates.

- Numeric feature binning: Continuous features (e.g., duration, dest_port_zeek) were discretized using quantile-based binning. Each numeric column was transformed into a categorical version (feature=binX) to reduce granularity and enable pattern detection across frequency buckets.

- Categorical feature encoding: Categorical features were numerically encoded using StringIndexer. Each category was mapped to a unique index, forming the foundation of transaction itemsets.

Numeric Feature Binning

Since ARM or the FP-Growth algorithm would not work well with continuous numerical features, key numerical features, such as duration, orig_bytes, resp_pkts, etc., were binned into discrete intervals based on defined value ranges. Each value is mapped to a bin number (1 through 5), with missing values assigned to bin 1. This transformation reduces noise and enables better generalization by machine learning models:

- Columns: The following numeric columns were used for binning: duration, orig_bytes, orig_pkts, orig_ip_bytes, resp_bytes, resp_pkts, resp_ip_bytes, and missed_bytes.

- Process:

- The numeric values are converted to integer bins.

- Missing values are replaced with 0.

- The values are directly converted to bins without additional statistical processing.

Nominal Feature Binning (Categorical Data)

Categorical features such as conn_state, proto, service, local_orig, and local_resp were binned mainly to handle the wide range of values:

- Columns: The following columns have been used for nominal feature binning: conn_state, service, proto, local_origin, and local_resp.

- Process:

- Top 80% Rule: The most frequent categories making up 80% of the total occurrences are assigned unique bins.

- Grouping Remaining Categories: Categories outside the top 80% are grouped into a single bin.

5. Results and Discussion

For the experiments, the following mining configurations were used:

- Support threshold: 1%. In Big Data, typically, a smaller support threshold is used.

- Confidence threshold: 50%.

- Features used: conn_state, proto, src_ip_group, dest_ip_group, src_port_zeek_bin, est_port_zeek_bin, duration_bin, orig_bytes_bin, orig_pkts_bin, orig_ip_bytes_bin, resp_bytes_bin, resp_pkts_bin, and resp_ip_bytes_bin.

The rule filtering criteria used were as follows:

- Confidence = 100%.

- Lift > 1.

- Top 48 rules by support.

- Redundant subset rules eliminated.

Software and hardware specs used were as follows:

- CPU: 4 CPUs, 87 MHz.

- Memory: 8 GB, 1 GB active memory.

- Hard Disk: 25 GB, Thick Provision Laxy Zeroed.

- Compatibility: ESXi 8.0 U2 and later (VM version 21).

- Python version: 3.10.18.

The next section presents the results by each attack tactic: Credential access [20], reconnaissance [21], defense evasion [25], exfiltration [26], initial access [22], persistence [24], privilege escalation [23], and finally, we presented results of benign data to have a baseline. Since FP-Growth mining presents a lot of rules, for each section, the analysis was performed by presenting the top rules by increment, high-confidence rules by increment, subset and superset pruning by increment, rule evolution trends, and increment-wise conclusions.

5.1. The Credential Access Tactic

5.1.1. High-Confidence Rules

Table 9 presents, by increment, the rules with 100% confidence with a lift greater than one and support greater than 1%. As Table 9 shows, some rules were added with each increment. At 50–70%, rules cluster around proto=tcp and conn_state=SF with increasing support. At 80–100%, rules involving rare REJ states, duration, and packet combinations emerge—reflecting more sophisticated credential abuse attempts.

Table 9.

Credential access: High-confidence rules by increment.

5.1.2. Top Rules for the Credential Access Tactic

Table 10 presents the top rules by increment. The rule involving {proto=tcp, service_bin=1} leading to conn_state=SF is the most stable and high-support rule across all increments. Support increases incrementally, confirming consistent credential access behavior.

Table 10.

Credential access: Top rules by increment.

5.1.3. Subset and Superset Pruning for the Credential Access Tactic

Table 11 presents subset and superset pruning by increment. Progressively, rules become layered with multiple conditions. Subsets are pruned as supersets offer stronger precision and rule quality. Pruning favors higher support.

Table 11.

Credential access: Subset and superset pruning by increment.

5.1.4. Rule Evolution Trends for the Credential Access Tactic

Table 12 presents rule evolution trends by increment, and Table 13 presents increment-wise conclusions for the credential access tactic.

Table 12.

Credential access: Rule evolution trends by increment.

Table 13.

Credential access: Increment-wise conclusions.

5.1.5. Overall Conclusion for Credential Access

From the earliest stage, credential access behavior was strongly characterized by TCP flows resulting in conn_state=SF. The rule {proto=tcp, service_bin=1} → {conn_state=SF} appeared consistently across all increments, increasing in support from 14.58% at 50% to 19.72% at 100%. Additional rules targeting conn_state=REJ and complex combinations of duration_bin, orig_bytes_bin, and resp_pkts_bin emerged in later stages. Subset pruning removed general rules like {proto=tcp} → {conn_state=SF} in favor of more precise supersets. Rule evolution reflected a shift from simple protocol–service relationships to multi-feature signatures of credential abuse, particularly at 80% and beyond.

Credential access behavior is effectively modeled by FP-Growth incremental mining. Early patterns are simple but reliable; later increments add refinement and depth.

Superset rules outperform subsets due to higher support. The progression affirms that credential access often hinges on specific service and protocol pairs (notably TCP/HTTP/SSL/SF), with rejection behaviors appearing only under more nuanced conditions. This analysis supports preemptive threat detection based on early rule emergence and validates the structured binning logic used in rule construction.

5.2. The Reconnaissance Tactic

5.2.1. High-Confidence Rules by Increment

Table 14 presents, by increment, the rules with 100% confidence with a lift greater than one and support greater than 1%. From early increments, rules concerning {proto=tcp} and {conn_state=SF} dominate, signaling stable TCP-based flows. In later increments, specialized UDP-S0 and REJ behavior emerge, indicating refined reconnaissance probing.

Table 14.

Reconnaissance: High-confidence rules by increment.

5.2.2. Top Rules for the Reconnaissance Tactic

Table 15 presents the top rules by increment. A pattern consistently dominates all increments—that proto=tcp with service_bin=1 is the most characteristic trait of legitimate or frequent reconnaissance activities.

Table 15.

Reconnaissance: Top rules by increment.

5.2.3. Subset and Superset Pruning the Reconnaissance Tactic

Table 16 presents subset and superset pruning by increment. Each increment reveals rule extensions that boost specificity and discriminative power, justifying superset preservation.

Table 16.

Reconnaissance: Subset and superset pruning by increment.

5.2.4. Rule Evolution Trends for the Reconnaissance Tactic

Table 17 presents rule evolution trends by increment, and Table 18 presents increment-wise conclusions for the reconnaissance tactic.

Table 17.

Reconnaissance: Rule evolution trends by increment.

Table 18.

Reconnaissance: Increment-wise conclusions.

5.2.5. Overall Summary for Reconnaissance

The incremental FP-Growth analysis of reconnaissance activity confirms that primary patterns such as {proto=tcp} → {conn_state=SF} and {proto=udp} → {conn_state=S0} arise early and persist across data increments. As the dataset expands, nuanced behaviors like REJ responses, port-proto interactions, and internal-to-external IP flows refine the rule landscape. Subset elimination enhanced interpretability, while high-confidence and top support rules maintained consistency, providing a dependable base for attack detection and behavior modeling.

Early stages were dominated by {proto=tcp, service_bin=1} → {conn_state=SF} with support stabilizing around 19.7% by 100%. UDP-based scanning signatures (e.g., {proto=udp, duration_bin=1} → {conn_state=S0}) emerged early and remained consistent. By the 80% stage, REJ-based rules and combinations of service_bin, resp_bytes_bin, and IP grouping helped distinguish more targeted reconnaissance activity. Rule pruning steadily favored richer antecedents. The evolution of rules showed increasing complexity, with final stages refining edge cases rather than adding entirely new behaviors.

5.3. The Defense Evasion Tactic

5.3.1. High-Confidence Rules by Increment

Table 19 presents, by increment, the rules with 100% confidence with a lift greater than one and support greater than 1%. The initial rules focus on basic TCP protocol behavior with the SF state. From 70% onward, combinations with byte and duration bins create sharper distinctions in activity. By 100%, the most complex compound behaviors appear.

Table 19.

Defense evasion: High-confidence rules by increment.

5.3.2. Top Rules for the Defense Evasion Tactic

Table 20 presents the top rules by increment. From Table 20, it can be noted that the rule { proto=tcp, conn_state=SF} → {service_bin=1} is highly consistent across increments and becomes the strongest backbone pattern in the dataset.

Table 20.

Defense evasion: Top rules by increment.

5.3.3. Subset and Superset Pruning for the Defense Evasion Tactic

Table 21 presents subset and superset pruning by increment. As per Table 21, each increment includes pruning of general rules in favor of specific behavioral refinements. This improves precision and eliminates redundancy.

Table 21.

Defense evasion: Subset and superset pruning by increment.

5.3.4. Rule Evolution Trends for the Defense Evasion Tactic

Table 22 presents rule evolution trends by increment, and Table 23 presents increment-wise conclusions for the defense evasion tactic.

Table 22.

Defense evasion: Rule evolution trends by increment.

Table 23.

Defense evasion: Increment-wise conclusions.

5.3.5. Overall Conclusion for Defense Evasion

The FP-Growth mining for defense evasion reveals consistent early indicators in TCP/SF patterns and escalating specificity through feature intersections. From 70% onward, rules like {proto=udp, resp_pkts_bin=1} → {conn_state=S0} and {duration_bin=3, service_bin=2} → {conn_state=REJ} provided insight into stealth techniques and unusual packet profiles. Support for key rules (e.g., {proto=tcp, service_bin=1} → {conn_state=SF}) remained consistent across stages, but evolved through combinations with internal IPs, response bins, and port ranges. Subset pruning optimized rule space, while support trends indicated dominant behaviors. Superset pruning improved clarity, and the progression confirmed layered evasion strategies encoded in packet-level features. The mining process clearly captured both the general shape and subtle refinements of evasion tactics over time.

5.4. The Exfiltration Tactic

5.4.1. High-Confidence Rules by Increment

Table 24 presents, by increment, the rules with 100% confidence with a lift greater than one and support greater than 1%. The initial increments are dominated by TCP/SF combinations and UDP/S0 mappings. Later increments show the emergence of more complex, multi-feature patterns involving ports, services, and response byte bins.

Table 24.

Exfiltration: High-confidence rules by increment.

5.4.2. Top Rules for the Exfiltration Tactic

Table 25 presents the top rules by increment. As per Table 25, TCP-to-SF to service_bin=1 rules hold dominance across all increments with stable and high support values.

Table 25.

Exfiltration: Top rules by increment.

5.4.3. Subset and Superset Pruning for the Exfiltration Tactic

Table 26 presents subset and superset pruning by increment. As per Table 26, the supersets increasingly absorb subsets as feature complexity improves rule discrimination.

Table 26.

Exfiltration: Subset and superset pruning by increment.

5.4.4. Rule Evolution Trends for the Exfiltration Tactic

Table 27 presents rule evolution trends by increment, and Table 28 presents increment-wise conclusions for the exfiltration tactic.

Table 27.

Exfiltration: Rule evolution trends by increment.

Table 28.

Exfiltration: Increment-wise conclusions.

5.4.5. Overall Summary for Exfiltration

The exfiltration dataset shows early rule saturation for typical TCP-based communication, with stronger evolution of UDP-based attack pathways occurring in later increments. Rules like {proto=tcp, conn_state=SF} → {service_bin=1} remained the top support rule across all increments, while UDP-based rules (e.g., {proto=udp, duration_bin=1}) suggested hidden exfiltration mechanisms. Later stages introduced combinations involving resp_bytes_bin and dest_port_zeek_bin, indicating more intricate attack paths. As with other datasets, subset pruning helped reveal more discriminative multi-condition rules over time. Superset rule retention ensures the model prioritizes generalizable behaviors. High-support rules remain stable, confirming their predictive power. Emerging complex rules help isolate attack-specific traits in the full dataset.

5.5. The Initial Access Tactic

5.5.1. High-Confidence Rules by Increment

Table 29 presents, by increment, the rules with 100% confidence with a lift greater than one and support greater than 1%.

Table 29.

Initial access: High-confidence rules by increment.

5.5.2. Top Rules for the Initial Access Tactic

Table 30 presents the top rules by increment for the initial access tactic. The top support rules remained the same, while the support increased with each increment.

Table 30.

Initial access: Top rules by increment.

5.5.3. Subset and Superset Pruning by Increment for the Initial Access Tactic

Table 31 presents subset and superset pruning by increment for the initial access tactic.

Table 31.

Initial access: Subset and superset pruning by increment.

5.5.4. Rule Evolution Trends for the Initial Access Tactic

Table 32 presents rule evolution trends by increment, and Table 33 presents increment-wise conclusions for the initial access tactic.

Table 32.

Initial access: Rule evolution trends by increment.

Table 33.

Initial access: Increment-wise conclusions.

5.5.5. Overall Conclusion for Initial Access

Initial access mining uncovered early patterns that aligned with credential access, such as {proto=tcp, conn_state=SF} and {proto=udp, conn_state=S0}. Additionally, the FP-Growth incremental mining strategy of initial access successfully uncovered the progression of attack logic across the initial access data. Early TCP+SF rules dominate, forming the backbone of the detection model. By 60%, more specific combinations like {proto=tcp, src_ip_group=Internal_IP} and {duration_bin=2, orig_bytes_bin=1, proto=tcp} emerged. As more data was introduced, the rule set became richer with layered feature interactions—especially involving service type, IP group, and byte-level granularity. Superset rule selection further enhanced precision, and by the 100% increment, the system achieved near-total behavior coverage, capturing both mainstream and fringe access attempts. The 100% stage revealed high-precision, low-support rules indicative of targeted entry attempts (e.g., {service_bin=3, duration_bin=2, proto=tcp} → {conn_state=REJ}). Rule structure matured gradually, with strong incremental reinforcement of early patterns.

5.6. The Persistence Tactic

5.6.1. High-Confidence Rules by Increment

Table 34 presents, by increment, the rules with 100% confidence with a lift greater than one and support greater than 1%.

Table 34.

Persistence: High-confidence rules by increment.

5.6.2. Top Rules for the Persistence Tactic

Table 35 presents the top rules by increment for the persistence tactic.

Table 35.

Persistence: Top rules by increment.

5.6.3. Subset and Superset Pruning by Increment for the Persistence Tactic

Table 36 presents subset and superset pruning by increment for the persistence tactic.

Table 36.

Persistence: Subset and superset pruning by increment.

5.6.4. Rule Evolution Trends for the Persistence Tactic

Table 37 presents rule evolution trends by increment, and Table 38 presents increment-wise conclusions for the persistence tactic.

Table 37.

Persistence: Rule evolution trends by increment.

Table 38.

Persistence: Increment-wise conclusions.

5.6.5. Overall Conclusion for the Persistence Tactic

The persistence dataset maintains high consistency across increments. Dominant rules centered around {proto=tcp, service_bin=1} → {conn_state=SF} and {conn_state=SF, service_bin=1} → {proto=tcp}, with minimal drift in structure. High-confidence rules anchored in TCP-based service logic stabilize by 60–70%. Minimal variation appears past 80%, and pruning consistently retains only multi-feature supersets. Patterns involving proto=tcp, service_bin=1, and conn_state=SF were the dominant structural components of credential retention behavior in this dataset. Pruning consistently removed general forms in favor of multi-feature rules.

5.7. Privilege Escalation

5.7.1. High-Confidence Rules by Increment

Table 39 presents, by increment, the rules with 100% confidence with a lift greater than one and support greater than 1%.

Table 39.

Persistence: Increment-wise conclusions.

5.7.2. Top Rules for Privilege Escalation

Table 40 presents the top rules by increment.

Table 40.

Privilege escalation: Top rules by increment.

5.7.3. Subset and Superset Pruning for Privilege Escalation

Table 41 presents subset and superset pruning by increment.

Table 41.

Privilege escalation: Subset and superset pruning by increment.

5.7.4. Rule Evolution Trends for Privilege Escalation

Table 42 presents rule evolution trends by increment, and Table 43 presents increment-wise conclusions.

Table 42.

Privilege escalation: Rule evolution trends by increment.

Table 43.

Privilege escalation: Increment-wise conclusions.

5.7.5. Overall Conclusion for Privilege Escalation

The privilege escalation dataset reveals highly stable behavioral patterns early in the incremental FP-Growth process and progressively refines them. Top support rules involving TCP, internal IPs, and service-bin=1 remained unchanged across increments. By 70%, most meaningful rules—including those involving proto=tcp, conn_state=SF, and service_bin=1—had already stabilized. Subset pruning confirms the early emergence of dominant patterns. Support-based consistency across increments ensures strong signal reliability.

5.8. Benign Data

5.8.1. High-Confidence Rules by Increment

Table 44 presents, by increment, rules with 100% confidence with a lift greater than one and support greater than 1%. The trend is as follows: TCP connections resulting in the SF state dominate early and continue to persist with higher combinations in later increments.

Table 44.

Benign data: High-confidence rules by increment.

5.8.2. Top Rules with Benign Data

Table 45 presents the top rules by increment for benign data.

Table 45.

Benign data: Top rules by increment.

5.8.3. Subset and Superset Pruning for Privilege Escalation

Table 46 presents subset and superset pruning by increment.

Table 46.

Benign data: Subset and superset pruning by increment.

5.8.4. Rule Evolution Trends by Increment

Table 47 presents rule evolution trends by increment, and Table 48 presents increment-wise conclusions.

Table 47.

Benign data: Rule evolution trends by increment.

Table 48.

Benign data: Increment-wise conclusions.

5.8.5. Overall Summary of Benign Data

The FP-Growth mining of benign traffic exhibits strong stability, shown by repetitive rule patterns, dominated from 50% onward by {proto=tcp, service_bin=1} → {conn_state=SF} and {proto=tcp, conn_state=SF} → {service_bin=1}. TCP-based rules dominated early and remained central throughout. As more data was introduced, the complexity and specificity of the rules increased, yet the essence of the benign behavior remained unchanged. The rules maintained high support throughout (≈19.7% by 100%), indicating regular, low-variance communication behavior. Rule evolution mainly involved the incorporation of additional features such as orig_bytes_bin and src_ip_group, but without structural shifts. The evolution from 1–2 condition rules to fully saturated 3–4 item rule sets confirmed the benign traffic’s repetitive and predictable nature. Pruned rules consistently gave way to supersets with stronger precision. The benign dataset confirms FP-Growth’s ability to capture stable behavioral baselines.

6. Conclusions

The experiments employed FP-Growth incremental mining on network traffic data aligned with distinct MITRE ATT&CK tactics, for example, credential access, reconnaissance, and other tactics. Each experiment processed data progressively from 50% to 100%, revealing how frequent patterns evolved as more information was introduced. The core configuration included a minimum support threshold of 1% and a confidence threshold of 50%, but only rules achieving 100% confidence with a lift exceeding 1 were considered for the final evaluation. This filtering strategy, coupled with redundancy elimination favoring supersets, ensured that only the most informative and generalizable patterns were preserved across stages.

Using credential access, results indicated that high-confidence associations were already substantial by the initial 50% increment. For instance, combinations such as proto=tcp alongside conn_state=SF consistently predicted service_bin=1, with support close to 14.6%. As data volume increased to 60% and beyond, additional rule nuances appeared. New structures incorporated source IP groupings and duration bins, exemplified by rules like proto=tcp with src_ip_group=Internal_IP mapping to conn_state=SF, supported at 8.2%. By 70%, intersecting features such as duration, original bytes, and protocol formed richer antecedents, while at 80% and higher, rules capturing rare behaviors like service_bin=2 paired with duration_bin=2 predicting conn_state=REJ surfaced, indicating more specialized credential misuse scenarios. By the final increment at 100%, layered signatures involving TCP flows and multi-bin features had fully matured. Notably, the rule proto=tcp with service_bin=1 leading to conn_state=SF remained the most dominant pattern throughout, growing steadily in support from approximately 14.6% at the outset to nearly 19.7% by the last stage. The consistent pruning of simpler subset rules in favor of detailed supersets highlighted the dataset’s gradual transition toward more specific behavioral representations.

A similar progression was observed with the reconnaissance tactic, though with slightly different focal behaviors. Early stages emphasized simple mappings, such as proto=udp coupled with duration_bin=1 frequently predicting conn_state=S0, and proto=tcp paired with service_bin=1 reliably indicating conn_state=SF. As additional increments were incorporated, the patterns grew more intricate. By 70%, rules like duration_bin=2 combined with proto=tcp and orig_bytes_bin=1 signaled shifts toward multi-feature characterizations of scanning activity. Increments at 80% and 90% revealed distinctive reconnaissance signals, notably through the emergence of rules associating service_bin=4 and extended durations with REJ states. Even in the final 100% stage, the top rule continued to involve proto=tcp with service_bin=1 predicting conn_state=SF, reaching support levels near 19.7%, mirroring trends seen in the credential access context. Throughout, subset rules that generalized over fewer features were systematically removed and replaced by more precise combinations that leveraged byte, packet, and service bins to encode increasingly specialized traffic fingerprints.

Analyzing all tactics, the findings illustrate the strength of the incremental FP-Growth approach in capturing how fundamental traffic patterns emerge early and then evolve into richer, more nuanced forms as data volume increases. In credential access, the stability of proto=tcp and service_bin=1 flows leading to SF connection states served as a baseline for distinguishing normal from suspicious credential handling. Reconnaissance exhibited comparable patterns, though multi-feature rules involving UDP probes and rejection states only matured in later increments. Across all tactics, the repeated appearance of highly confident yet sparsely supported rules suggests shared tactics across different stages of compromise or scanning activity, reinforcing the value of tracking such patterns over time. This progression from broad associations to sharply defined behaviors validates both the binning strategy used to discretize network features and the iterative mining framework that incrementally built a comprehensive picture of network threat dynamics.

This study demonstrates that incremental application of the FP-Growth algorithm, when combined with feature binning and rule filtering, offers a scalable and interpretable approach to pattern discovery in large network security datasets. Through a staged analysis of multiple MITRE ATT&CK-aligned scenarios, the method was shown to effectively surface both high-support and rare-but-meaningful rules associated with distinct tactics.

The results indicate that core behavioral rules—such as those involving TCP protocols and service associations—emerge early and remain stable throughout later increments. At the same time, more discriminative, high-lift rules involving combinations of ports, IP groupings, and packet bins become increasingly evident in later stages. Superset rules were found to generalize and refine earlier subset forms, enhancing the specificity of rule-based threat profiling.

Overall, the incremental FP-Growth framework provides a structured lens through which network behaviors can be observed and compared over time, supporting not only classification but also investigative use cases such as anomaly tracking and technique attribution. And finally, the results of this work, the frequent itemsets, will be useful for intrusion detection machine learning/artificial intelligence algorithms.

7. Future Works

Future research can extend this work in several directions. One improvement involves adaptive binning strategies, such as entropy-based or clustering-informed bin definitions, to capture finer behavioral distinctions and respond dynamically to dataset characteristics. This would reduce the rigidity introduced by static bin boundaries and enhance rule granularity.

The incorporation of time-aware association rule mining, such as sequential pattern mining or temporal FP-Growth variants, represents another promising avenue. Such extensions could reveal multi-stage attack flows, thereby increasing the utility of the mined rules in operational threat detection systems.

Furthermore, integrating additional data layers—such as process-level telemetry, system logs, or enriched packet metadata—could allow for cross-modal rule generation. This would strengthen the semantic interpretation of patterns and align them more directly with adversarial tactics.

Finally, deploying the mined rule sets into an active monitoring or alerting framework and assessing their real-time efficacy in intrusion detection pipelines would bridge the gap between offline analysis and practical security enforcement.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.S.B., D.M., and S.C.B.; methodology, A.B. (Andrew Benyacko), S.S.B., D.M., and S.C.B.; software, A.B. (Andrew Benyacko) and A.B. (Arijit Bagchi); validation, S.S.B., D.M., and S.C.B.; formal analysis, A.B. (Andrew Benyacko), S.S.B., D.M., and S.C.B.; investigation, A.B. (Andrew Benyacko), A.B. (Arijit Bagchi), S.S.B., D.M., and S.C.B.; resources, D.M., S.S.B., and S.C.B.; data curation, A.B. (Andrew Benyacko) and A.B. (Arijit Bagchi); writing—original draft preparation, A.B. (Andrew Benyacko), A.B. (Arijit Bagchi), and S.S.B.; writing—review and editing, A.B. (Andrew Benyacko), A.B. (Arijit Bagchi), S.S.B., D.M., and S.C.B.; visualization, A.B. (Andrew Benyacko), A.B. (Arijit Bagchi), and S.S.B.; supervision, D.M., S.S.B., and S.C.B.; project administration, D.M., S.S.B., and S.C.B.; funding acquisition, D.M., S.S.B., and S.C.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by 2021 NCAE-C-002: Cyber Research Innovation Grant Program, grant number: H98230-21-1-0170. This research was also partially supported by the Askew Institute at the University of West Florida.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Agrawal, R.; Imielinski, T.; Swami, A. Mining association rules between sets of items in large databases. In ACM SIGMOD Record; ACM Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993; pp. 207–216. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, R.; Srikant, R. Fast algorithms for mining association rules in large databases. In Proceedings of the 20th VLDB Conference, Santiago, Chile, 12–15 September 1994; Morgan Kaufmann: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Han, J.; Pei, J.; Yin, Y. Mining frequent patterns without candidate generation. In ACM SIGMOD Record; ACM Press: New York, NY, USA, 2000; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Han, J.; Pei, J.; Kamber, M.; Tong, H. Data Mining: Concepts and Techniques, 4th ed.; Morgan Kaufmann: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Zeek Documentation. Connection Logs. 2025. Available online: https://docs.zeek.org/en/master/logs/conn.html (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- Trellix. What Is the MITRE ATT&CK Framework? Get the 101 Guide. 2024. Available online: https://www.trellix.com/en-us/security-awareness/cybersecurity/what-is-mitre-attack-framework.html (accessed on 17 March 2025).

- UWF Datasets Portal. 2025. Available online: https://datasets.uwf.edu (accessed on 13 March 2025).

- Elam, M.; Mink, D.; Bagui, S.S.; Plenkers, R.; Bagui, S.C. Introducing UWF-ZeekData24: An enterprise MITRE ATT&CK labeled network attack traffic dataset for machine learning/AI. Data 2025, 10, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, E.; Mink, D.; Spellings, P.; Bagui, S.S.; Bagui, S.C. Classifying cyber ranges: A case-based analysis using the UWF cyber range. Encyclopedia 2025, 5, 162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagui, S.; Devulapalli, K.; Coffey, J. A heuristic approach for load balancing the FP-Growth algorithm on MapReduce. Array 2020, 7, 100035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyad, A.; Norjihan, A.G.; Maple, C.; Machado, J.; Safa, N.S. Incremental algorithm for association rule mining under dynamic threshold. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 5398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morzy, M.; Morzy, T. Incremental association rule mining using materialized data mining views. In Proceedings of the Third International Conference on Advances in Information Systems, Izmir, Turkey, 20–22 October 2004; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2004; pp. 2–10. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, P.S.M.; Lee, C.C.; Chen, A.L.P. An efficient approach for incremental association rule mining. In Methodologies for Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; Zhong, N., Zhou, L., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1999; Volume 1574, pp. 3–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarda, N.L.; Srinivas, N.V. An adaptive algorithm for incremental mining of association rules. In Proceedings of the Ninth International Workshop on Database and Expert Systems Applications (DEXA), Vienna, Austria, 26–28 August 1998; pp. 240–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, D.K.; Ghosh, A.; Nath, B. Incremental association rule mining: A survey. WIREs Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2013, 3, 157–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezeife, C.I.; Su, Y. Mining incremental association rules with generalized FP-tree. In Advances in Artificial Intelligence; Cohen, R., Spencer, B., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002; Volume 2338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgelt, C. An implementation of the FP-Growth algorithm. In Proceedings of the 1st International Workshop on Open-Source Data Mining: Frequent Pattern Mining Implementations, Chicago, IL, USA, 21 August 2005; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, A.; Sinha, D. FP-growth-based signature extraction and unknown variants of DoS/DDoS attack detection on real-time data stream. J. Inf. Secur. Appl. 2025, 89, 103996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Yin, S.; Liu, J.; Zhang, M. Research of Improved FP-Growth Algorithm in Association Rules Mining; Hindawi Publishing Corporation: London, UK, 2015; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- MITRE ATT&CK. Credential Access, Tactic TA0006—Enterprise. 2025. Available online: https://attack.mitre.org/tactics/TA0006/ (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- MITRE ATT&CK. Reconnaissance, Tactic TA0043—Enterprise. 2025. Available online: https://attack.mitre.org/tactics/TA0043/ (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- MITRE ATT&CK. Initial Access, Tactic TA0001—Enterprise. 2025. Available online: https://attack.mitre.org/tactics/TA0001/ (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- MITRE ATT&CK. Privilege Escalation, Tactic TA0004—Enterprise. 2024. Available online: https://attack.mitre.org/tactics/TA0004/ (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- MITRE ATT&CK. Persistence, Tactic TA0003—Enterprise. 2025. Available online: https://attack.mitre.org/tactics/TA0003/ (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- MITRE ATT&CK. Defense Evasion, Tactic TA0005—Enterprise. 2025. Available online: https://attack.mitre.org/tactics/TA0005/ (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- MITRE ATT&CK. Exfiltration, Tactic TA0010—Enterprise. 2025. Available online: https://attack.mitre.org/tactics/TA0010/ (accessed on 17 April 2025).

- Bagui, S.; Just, J.; Bagui, S. Deriving strong association mining rules using a dependency criteria, the lift measure. Int. J. Data Anal. Tech. Strateg. 2009, 1, 297–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, P.-N.; Steinbach, M.; Kumar, V. Introduction to Data Mining; Pearson Addison Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).