Abstract

Intrusion detection systems (IDSs) must balance detection quality with operational transparency. We present a deterministic, leakage-free comparison of three classical classifiers: Naïve Bayes (NB), Logistic Regression (LR), and Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA). We also propose a hybrid pipeline that trains LR on Autoencoder embeddings (AE). Experiments use NSL-KDD and CICIDS2017 under two regimes (with/without SMOTE (Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique) applied only on training data). All preprocessing (one-hot encoding, scaling, and imputation) is fitted on the training split; fixed seeds and deterministic TensorFlow settings ensure exact reproducibility. We report a complete metric set—Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1, Area Under the Curve (AUC), and False Alarm Rate (FAR)—and release a replication package (code, preprocessing artifacts, and saved prediction scores) to regenerate all reported tables and metrics. On NSL-KDD, AE+LR yields the highest AUC (≈0.904) and the strongest F1 among the evaluated models (e.g., 0.7583 with SMOTE), while LDA slightly edges LR on Accuracy/F1. NB attains very high Precision (≈0.98) but low Recall (≈0.24), resulting in the weakest F1, yet a low FAR due to conservative decisions. On CICIDS2017, LR delivers the best Accuracy/F1 (0.9878/0.9752 without SMOTE), with AE+LR close behind; both approach ceiling AUC (≈0.996). SMOTE provides modest gains on NSL-KDD and limited benefits on CICIDS2017. Overall, LR/LDA remain strong, interpretable baselines, while AE+LR improves separability (AUC) without sacrificing a simple, auditable decision layer for practical IDS deployment.

1. Introduction

In today’s hyperconnected society, safeguarding digital infrastructures has become a cornerstone of national, economic, and social stability. As cyber threats continue to evolve in scale and complexity, organizations must adopt intelligent and proactive defense mechanisms. Intrusion detection systems (IDSs) represent a critical layer in this defense architecture, serving to monitor and identify malicious or anomalous activity in real time. Traditionally, IDSs have relied on signature-based or rule-based techniques, which match observed patterns against known attack signatures. Although effective against previously encountered threats, these approaches often fail to detect new or obfuscated attacks and typically suffer from high false positive rates []. To address these limitations, recent efforts have turned to machine learning (ML), deep learning (DL), and hybrid methods capable of generalizing from data and adapting to new threat landscapes.

Machine learning models (both supervised and unsupervised) enable systems to learn behavioral patterns from historical traffic data []. Classical classifiers, such as Naïve Bayes (NB), Logistic Regression (LR), and Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA), apply well-established mathematical frameworks to detect anomalies in network activity []. While these models are often interpretable and computationally lightweight, they can struggle with non-linear relationships and high-dimensional feature spaces typical of modern cybersecurity datasets.

In contrast, deep learning (DL) architectures provide powerful tools for automated representation learning and pattern recognition. In particular, Autoencoders (AEs) can learn compact, informative latent embeddings from network traffic data [,,]. These embeddings can then be fed to simple yet effective downstream classifiers such as LR, yielding hybrid pipelines (AE+LR) that combine unsupervised feature learning with interpretable decision boundaries. Such DL-based representations have demonstrated strong performance in identifying complex and evolving cyber threats [,]. However, practical deployment still faces challenges related to computational demands, data requirements, and explainability [,].

Beyond intrusion detection, deep neural architectures have also been applied to security-critical communication scenarios, such as IRS (intelligent reflecting surfaces)-assisted NOMA (nonorthogonal multiple access) systems optimized via cooperative graph neural networks (CO-GNN) [], which emphasize rich visualization of performance metrics to complement tabular evaluations.

In the context of applied AI and cybersecurity engineering, conducting rigorous comparative studies is vital. Such evaluations clarify when interpretable statistical models are sufficient for effective detection and when representation learning can provide measurable gains when paired with lightweight classifiers.

This study presents a deterministic comparison of three classical classifiers (NB, LR, and LDA) and a hybrid deep-learning pipeline (AE+LR) for intrusion detection []. To ensure robustness, we employ two widely used benchmark datasets: NSL-KDD [] (derived from KDD’99) and CICIDS2017 [], which include up-to-date traffic and attack types. These datasets provide a balanced basis to examine model generalization, performance across diverse attacks, and real-world feasibility.

We assess each model using standard performance metrics: Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-score, AUC, and FAR. In addition, we provide complete tabular reporting. The key contribution of this paper includes the following:

(i) a unified, leakage-free, and deterministic evaluation protocol applied consistently across NB, LR, LDA, and a hybrid AE+LR pipeline; (ii) dual training regimes (with/without SMOTE strictly on training folds) to isolate the effect of class rebalancing; (iii) a transparent deep-representation + linear classifier baseline (AE+LR) that combines competitive AUC/F1 with auditability; (iv) complete tables (Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1, AUC, FAR) for both NSL-KDD and CICIDS2017; and (v) a replication package (code, configs, fixed seeds) enabling reproducibility.

From an operational standpoint, we interpret transparency as the use of models whose decision functions can be inspected, reproduced, and calibrated by security analysts. For this reason, we concentrate on linear probabilistic classifiers (LR/LDA) and on a hybrid AE+LR pipeline in which the deep Autoencoder is used solely as a representation learner, while the final decision layer remains a simple, auditable logistic regression classifier.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows. Section 2 provides a review of related research on IDS using ML and DL. Section 3 describes the experimental methodology. Section 4 presents the results. Section 5 discusses the findings, limitations, contextual relevance, recommendations and directions for future work.

2. Evolution of Machine Learning and Deep Learning for IDS

2.1. Classical ML Baselines for IDS

Early applications of machine learning to intrusion detection focused on algorithms like decision trees, support vector machines, k-nearest neighbors, Naïve Bayes, and Logistic Regression to classify network traffic as normal or attack []. For example, Gu and Lu [] proposed an SVM-based IDS enhanced with Naïve Bayes feature embedding, which improved detection performance by leveraging probabilistic feature–class relationships. Traditional ML models, however, often encounter challenges with the high dimensionality and complexity of network data. Naïve Bayes (NB) assumes feature independence and can underperform when features are correlated (common in network traffic), leading to high false positives, especially on minority attack classes []. Logistic Regression (LR) is a linear classifier that tends to perform well only if the data is roughly linearly separable []. LDA (Linear Discriminant Analysis), similarly, finds linear combinations of features that separate classes; it has been used both for dimensionality reduction and classification in IDS studies. For instance, a recent work in an industrial IoT (Internet of Things) context reported ~97% detection accuracy using a wrapper-based LDA classifier on the NSL-KDD dataset []. Overall, while fast and interpretable, these statistical models may struggle to capture non-linear relations in network traffic features or the complex structures present in modern attack behaviors. In addition to their competitive accuracy, LR and LDA expose linear decision functions and probabilistic outputs that can be directly inspected or combined with post hoc explanation tools, which facilitates auditing and integration into existing SOC workflows.

2.2. Deep Learning Approaches and AE-Based Representation Learning

In parallel, deep learning approaches gained popularity for their ability to learn feature representations, beginning with intrusion detection using feedforward neural network (FFNN) classifiers [,]. Autoencoders (AEs), as unsupervised neural networks, learn to compress data into a lower-dimensional latent space and reconstruct it. They have been actively studied in IDS because they can learn to model typical network traffic and derive informative latent embeddings []. Several studies analyze diverse AE architectures for intrusion detection, showing that model capacity and bottleneck size strongly affect downstream performance; for example, a simple stacked AE has reported F1-scores close to 0.90 on NSL-KDD when properly tuned []. Other works further improve AE-based pipelines by addressing data biases and outliers, reaching accuracies around 90% on NSL-KDD []. While many AE studies use reconstruction-error thresholds for anomaly scoring—whose calibration can be delicate []—an alternative is to use AE purely as a representation learner and train a lightweight supervised classifier on top of its embeddings (e.g., AE+LR), which removes the need for threshold tuning while retaining interpretability.

2.3. Ensembles and Imbalance Remedies

Beyond single models, ensemble strategies have been explored to boost robustness. Roy et al. [] introduced a stacking ensemble of boosted decision tree models, evaluated on IoT traffic with NSL-KDD and CICIDS2017; their system obtained a high overall accuracy of 98.5% on NSL-KDD and 99.11% on CICIDS2017, though detection of rare attack classes (user to root (U2R), remote to local (R2L)) remained challenging. De Souza et al. [] reported a two-step ensemble (ExtraTrees and neural networks) that achieved an impressive 99.81% accuracy on NSL-KDD; however, even this advanced model detected only 68.75% of U2R attacks, underscoring the persistent difficulty of heavily imbalanced distributions. To mitigate these issues, recent work frequently incorporates data oversampling, cost-sensitive learning [], and feature selection.

In summary, the literature indicates that learned representations from deep models—particularly Autoencoders—often enhance detection accuracy and adaptability to evolving attacks when paired with simple classifiers, while classical methods (NB, LR, LDA) remain attractive for speed, simplicity, and explainability []. Our study builds on these insights by directly comparing representative classical classifiers (NB, LR, LDA) against a hybrid pipeline that uses unsupervised deep representations with a linear decision layer (AE+LR) under a unified experimental setup.

3. Methodology

We design a fair, deterministic and leakage-free evaluation to compare classical machine learning baselines with a hybrid deep-representation pipeline for IDS. All preprocessing/resampling steps are fit only on training data; seeds are fixed across Python V.3.12.11/NumPy V.2.3.3/TensorFlow V.2.20.0, enabling exact reproducibility.

3.1. Evaluation Protocol and Datasets

We adopt a held-out scheme in both benchmarks: for NSL-KDD, we use the official KDDTrain+/KDDTest+ split; for CICIDS2017, we use a single 80/20 stratified split with random_state=42. We evaluate the binary setting (attack vs. normal) to focus on primary detection, consistent with prior IDS literature [,,,].

NSL-KDD (improved KDD’99) contains 41 features plus the label and four attack families []. Table 1 shows a summary of the information about the type of traffic contained in this dataset.

Table 1.

Class distribution in the NSL-KDD dataset (KDDTrain+ and KDDTest+ combined).

CICIDS2017 captures modern traffic/attacks with ∼80 numerical flow features [,]. Table 2 shows a summary of the information about the type of traffic contained in this dataset.

Table 2.

Attack categories from CICIDS2017 used in this study (80/20 stratified split; natural class imbalance retained).

External validity caveat: NSL-KDD is legacy, and CICIDS2017 is controlled; we retain them for comparability and availability.

3.2. Preprocessing (Uniform and Leakage-Free)

Pipelines are implemented uniformly: one-hot encoding for NSL-KDD categorical fields, min–max scaling to [0, 1], and median imputation for CICIDS2017 numerics. All transformers are fit on training only and applied to the held-out test split. To mitigate imbalance, we use SMOTE on training data only (no resampling in validation/test), preserving original test distributions—a standard, transparent practice in IDS [,].

3.3. Models and Hyperparameters

We compare well-established baselines (NB, LR, LDA) recommended by recent surveys for transparency/reproducibility [,] against a hybrid deep-representation pipeline (AE+LR) supported by prior IDS evidence [,,]. We deliberately use minimal, uniform tuning to avoid family-specific advantages. Table 3 shows a summary of model configurations used in this work.

Table 3.

Model configurations (shared across datasets unless noted).

3.4. Metrics and Reproducibility

We report Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1, AUC (from predict_proba) and False Alarm Rate (FAR), with

where represents the number of false positives and the number of true negatives.

Reporting Recall together with FAR for all models (Table 4, Table 5, Table 6 and Table 7) directly quantifies the trade-off between missed attacks and alert volume. For instance, NB attains very low FAR at the cost of extremely low Recall on NSL-KDD, whereas LR, LDA, and AE+LR achieve substantially higher Recall with modest FAR, offering more favorable operating points for real deployments.

Deterministic TensorFlow ops are enabled; exact seeds, scripts, and stored prediction scores are released in a replication package (code/configs/predict_proba), enabling byte-for-byte regeneration of tables/metrics.

All code, preprocessing artifacts, trained models, and configuration files are publicly available in our replication repository at https://github.com/miguelarcosa/IDS-KDD-CICIDS2017.git (accessed on 1 November 2025) [], ensuring full byte-level reproducibility of all tables and metrics reported in this paper.

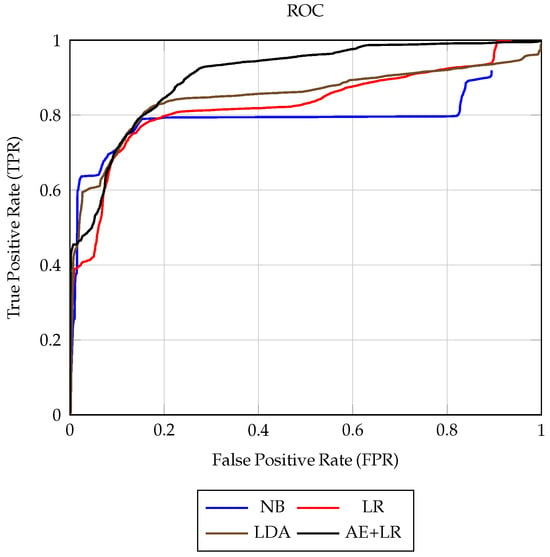

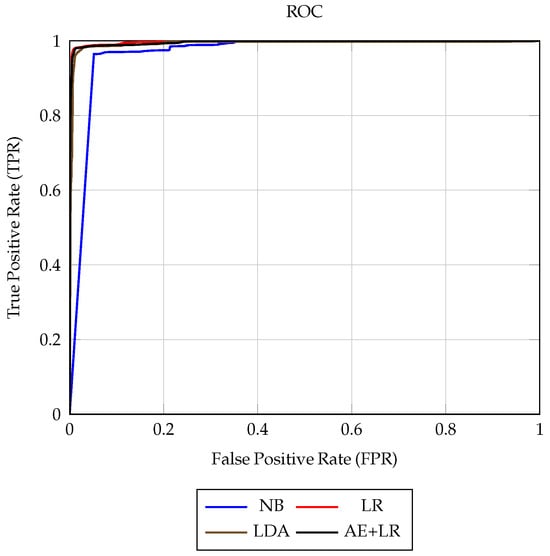

In addition to scalar metrics, we visualize model behavior on the held-out test splits by plotting receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for the four pipelines (NB, LR, LDA, AE+LR). ROC curves are computed from the saved predict_proba scores in our replication package using the scikit-learn implementation, and are shown for the regime without SMOTE, where the main AUC differences appear. The full set of confusion matrices is shown in Appendix A.

4. Results

This section reports the performance of the four evaluated approaches: Naïve Bayes (NB), Logistic Regression (LR), Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA), and the hybrid Autoencoder embeddings + Logistic Regression (AE+LR) in NSL-KDD and CICIDS2017 datasets. We present Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1, AUC, and False Alarm Rate (FAR), consistent with the evaluation protocol described earlier. Unless noted, models use default thresholds (0.5 for probabilistic outputs), and all preprocessing/SMOTE steps are fit on the training split only.

4.1. Overall Performance on NSL-KDD

Table 4 and Table 5 summarize the binary results on NSL-KDD without and with SMOTE, respectively. Across both regimes, LR, LDA, and AE+LR clearly outperform NB, which shows very high Precision but poor Recall (i.e., conservative attack labeling that misses many positives).

For reference, after applying SMOTE only on the training split, the NSL-KDD training set becomes exactly balanced at Benign:Attack = 80,892:80,892 (1:1).

Table 4.

Performance metrics of all models on the NSL-KDD test set (without SMOTE).

Table 4.

Performance metrics of all models on the NSL-KDD test set (without SMOTE).

| Model | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | FAR | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naïve Bayes | 0.5649 | 0.9800 | 0.2406 | 0.3864 | 0.0065 | 0.7987 |

| Logistic Regression (LR) | 0.7443 | 0.9142 | 0.6079 | 0.7302 | 0.0754 | 0.8276 |

| LDA | 0.7616 | 0.9249 | 0.6326 | 0.7514 | 0.0679 | 0.8484 |

| Autoencoder (AE) + LR | 0.7616 | 0.9165 | 0.6397 | 0.7534 | 0.0770 | 0.9040 |

Table 5.

Performance metrics of all models on the NSL-KDD test set (with SMOTE on training data only).

Table 5.

Performance metrics of all models on the NSL-KDD test set (with SMOTE on training data only).

| Model | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | FAR | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naïve Bayes | 0.5650 | 0.9800 | 0.2408 | 0.3866 | 0.0065 | 0.7978 |

| Logistic Regression (LR) | 0.7458 | 0.9137 | 0.6112 | 0.7324 | 0.0763 | 0.8227 |

| LDA | 0.7632 | 0.9238 | 0.6365 | 0.7537 | 0.0694 | 0.8525 |

| Autoencoder (AE) + LR | 0.7654 | 0.9166 | 0.6467 | 0.7583 | 0.0778 | 0.9043 |

- NB: Exceptionally high Precision (≈0.98) but low Recall (≈0.24) produces the lowest F1; FAR is minimal due to the conservative decision boundary.

- LR vs. LDA: LDA edges LR slightly on Accuracy/F1 and AUC in both regimes; differences are modest.

- AE+LR: Delivers the highest AUC (≈0.904) and the best Recall/F1 trade-off among the four, with Accuracy comparable to LDA.

- Effect of SMOTE: Improvements are small but consistent where they appear (e.g., LDA F1: 0.7514→0.7537; AE+LR F1: 0.7534→0.7583), indicating mild gains in detecting attacks at an approximately unchanged FAR.

On NSL-KDD, Figure 1 complements Table 4 and Table 5 by showing that the AE+LR pipeline not only attains the highest AUC (approximately 0.904) but also yields a ROC curve that lies above those of LR and LDA for most operating points, while NB lags behind, particularly in the mid-to-high FPR region. This confirms that AE+LR achieves the best overall separability between normal and attack traffic among the evaluated models.

Figure 1.

ROC curves on the NSL-KDD test split (without SMOTE) for Naïve Bayes (NB), Logistic Regression (LR), Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA), and the hybrid Autoencoder + LR (AE+LR). The AE+LR curve attains the highest AUC (approximately 0.904) and lies above those of LR and LDA for most operating points, illustrating its improved separability compared to the purely linear baselines.

4.2. Overall Performance on CICIDS2017

Table 6 and Table 7 summarize binary results on CICIDS2017. Performances are generally high across LR, LDA, and AE+LR, with NB trailing due to a high FAR and lower Precision.

Table 6.

Performance metrics of all models on the CICIDS2017 dataset (without SMOTE).

Table 6.

Performance metrics of all models on the CICIDS2017 dataset (without SMOTE).

| Model | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | FAR | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naïve Bayes | 0.8565 | 0.6364 | 0.9742 | 0.7699 | 0.1820 | 0.9711 |

| Logistic Regression (LR) | 0.9878 | 0.9722 | 0.9783 | 0.9752 | 0.0091 | 0.9961 |

| LDA | 0.9784 | 0.9426 | 0.9715 | 0.9569 | 0.0193 | 0.9923 |

| Autoencoder (AE) + LR | 0.9859 | 0.9691 | 0.9738 | 0.9715 | 0.0101 | 0.9960 |

Table 7.

Performance metrics of all models on the CICIDS2017 dataset (with SMOTE on training data only).

Table 7.

Performance metrics of all models on the CICIDS2017 dataset (with SMOTE on training data only).

| Model | Accuracy | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | FAR | AUC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naïve Bayes | 0.8564 | 0.6362 | 0.9742 | 0.7697 | 0.1821 | 0.9686 |

| Logistic Regression (LR) | 0.9862 | 0.9623 | 0.9824 | 0.9723 | 0.0126 | 0.9962 |

| LDA | 0.9735 | 0.9156 | 0.9830 | 0.9481 | 0.0296 | 0.9924 |

| Autoencoder (AE) + LR | 0.9806 | 0.9428 | 0.9805 | 0.9613 | 0.0194 | 0.9954 |

- LR and AE+LR: Both achieve a near-ceiling AUC (≈0.996). LR attains the best overall Accuracy/F1 (0.9878/0.9752) without SMOTE; AE+LR is a close second (0.9859/0.9715).

- LDA: Strong but consistently below LR/AE+LR in this dataset, with slightly higher FAR.

- NB: High Recall (≈0.97) but much lower Precision and a high FAR (≈0.18), yielding the lowest F1.

- Effect of SMOTE: On CICIDS2017 (already balanced at the aggregate level after unification), SMOTE slightly reduces Accuracy/F1 for LR and AE+LR and increases FAR, which is consistent with minor overcompensation when the base split is relatively well balanced.

On CICIDS2017, the impact of SMOTE is inherently constrained by the near-ceiling performance already achieved by LR, LDA, and AE+LR. As reported in Table 6 and Table 7, these models reach ROC AUC values close to 0.996 and very high F1-scores even without oversampling, and SMOTE only produces small fluctuations at the third or fourth decimal place. In this regime, the decision boundary already separates benign and attack traffic very effectively, so synthetic minority examples generated by SMOTE tend to lie in regions of the feature space that are already densely populated by correctly classified points, adding little new information. In addition, some attack subcategories appear with very few and potentially noisy samples, making them poor candidates for interpolation: oversampling around isolated, overlapping, or mislabeled points may fail to improve, or even slightly perturb, the classifier’s decision surface. These observations clarify that, for CICIDS2017, SMOTE operates under conditions where its theoretical benefits are limited, and its role is mainly to provide a consistent comparison with NSL-KDD rather than to drive substantial performance gains.

For CICIDS2017, Figure 2 confirms that LR, LDA, and AE+LR all operate in a near-ceiling regime, with ROC curves that are almost indistinguishable (AUC for LR and AE+LR; Table 6 and Table 7). NB, in contrast, traces a noticeably lower ROC curve, reflecting its higher FAR and reduced Precision despite very high Recall. Overall, once the feature space is well separated, the additional non-linear representation from AE does not translate into a visible ROC advantage over LR on this benchmark, even though AE+LR still matches LR in AUC.

Figure 2.

ROC curves on the CICIDS2017 test split (without SMOTE) for Naïve Bayes (NB), Logistic Regression (LR), Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA), and the hybrid Autoencoder + LR (AE+LR). The AE+LR curve attains the highest AUC and lies above those of LR and LDA for most operating points, illustrating its improved separability compared to the purely linear baselines.

Runtime Analysis

Table 8 shows that, on the smaller NSL-KDD benchmark, all models train in less than 26 s and complete inference on the entire test split in at most 0.084 s. On the larger CICIDS2017 dataset, training times increase by roughly two orders of magnitude due to the 1.68 million training flows, yet even the most expensive configuration (AE+LR with SMOTE) finishes training in about 421 s (approximately 7 min). Inference on CICIDS2017 remains inexpensive for the classical models (no more than 1.9 s to score the whole test split), and although AE+LR requires about 71–73 s to compute embeddings and predictions for the 419,995 test flows, this still corresponds to sub-millisecond latency per flow. Overall, all four pipelines keep the runtime at a level compatible with near real-time IDS deployment on commodity hardware. These results are shown in Appendix B, in Table A17, Table A18 and Table A19.

Table 8.

Training and inference time per model and dataset (median over three runs, in seconds).

4.3. Takeaways

Across both datasets, NB provides a fast but conservative baseline with high Precision and low Recall. LDA is a strong classical competitor and slightly edges LR on NSL-KDD, whereas LR leads on CICIDS2017. The hybrid AE+LR consistently offers the best AUC and competitive F1, suggesting that unsupervised embeddings help linear classifiers capture non-linear structure without sacrificing interpretability. By using the autoencoder purely to learn latent embeddings and delegating all final decisions to a linear LR classifier, AE+LR improves separability (AUC/F1) over LR/LDA while preserving the same transparent, feature-weight–based decision layer that operators can inspect, calibrate, and document. SMOTE yields modest gains in NSL-KDD (where minority attacks are scarce) and does not help—and can slightly hurt—on the unified CICIDS2017 split. These patterns align with prior IDS evidence: classical linear/probabilistic baselines remain valuable, and hybrid deep representations can further enhance linear decision functions under tabular traffic features.

4.3.1. Comparison with Related Work

It is instructive to situate our findings alongside recent IDS evaluations on NSL-KDD and CICIDS2017. Broadly, prior works report that deep learning (DL) models frequently attain near-ceiling discrimination on these corpora, whereas well-regularized linear/probabilistic baselines remain competitive, transparent references. A compact side-by-side comparison with recent IDS studies is summarized in Table 9.

Table 9.

Compact comparison with related IDS studies on NSL-KDD/CICIDS2017 (binary settings when reported).

Linear/Probabilistic baselines. Ali et al. [] report LR around ∼97% Accuracy, and NB near ∼64% on their benchmark—trends that mirror our binary CICIDS2017 results, where LR achieves 98.78% Accuracy (F1 = 0.9752), and NB substantially trails due to its low Precision and high FAR (Table 6). Our LDA is also competitive, consistent with surveys that position LR/LDA as strong, reproducible tabular baselines [,].

Deep learning and hybrids. Several studies show DL advantages on NSL-KDD/CICIDS2017. Umer and Abbasi [] report an AE–LSTM (Long Short-Term Memory) two-stage system with ∼89% accuracy on NSL-KDD, prioritizing low false alarms; Chen et al. [] obtain 86.8% on CICIDS2017 with a Deep Belief Network (DBN)+LSTM; and Roy et al. [] reach 99.11% on CICIDS2017 using a lightweight supervised ensemble. Rather than training a full end-to-end DL classifier, our study adopts a hybrid approach (AE+LR): an autoencoder provides unsupervised embeddings and a linear LR supplies an auditable decision layer. This yields near-ceiling AUC on CICIDS2017 (AUC ≈ 0.996) and the top AUC on NSL-KDD among our four families (AUC ≈ 0.904), aligning with evidence that AE-driven representation learning can improve linear separability while preserving interpretability [,,,,].

On metric deltas across papers. Absolute numbers in cross-paper comparisons routinely vary with dataset curation (binary vs. multi-class), train/test protocol (official splits vs. random), feature engineering and normalization, imbalance remedies, and leakage controls. For instance, our pipelines fit all preprocessing (and SMOTE when used) strictly on training data and evaluate on held-out splits, which can produce more conservative but comparable scores. Prior work also documents that SMOTE often helps minority Recall on NSL-KDD but has mixed value on CICIDS2017, depending on the split [,]. Within this context, our results corroborate the prevailing ranking—NB ≪ LR/LDA ≲ DL—while showing that a simple AE+LR hybrid can deliver DL-like AUC with a transparent classifier.

4.3.2. Key Takeaways

In summary, no single model is universally best for all deployment constraints. Among classical baselines, LR and LDA provide strong, transparent performance with low computational cost, as confirmed by the training and inference times in Table 8, making them attractive when interpretability and latency are priorities []. NB is generally not competitive on modern IDS corpora unless paired with additional design choices (e.g., feature engineering or hybridization; see Gu & Lu []).

Our hybrid pipeline (AE+LR) shows that using an autoencoder purely as an unsupervised representation learner can deliver near state-of-the-art AUC on CICIDS2017 while preserving an auditable linear decision layer, aligning with reports that deep representations can improve linear separability without sacrificing explainability [,].

Operationally, the results underscore two practical points: (i) addressing class imbalance (e.g., with SMOTE applied only on training data) improves minority-class Recall on NSL-KDD, whereas its benefit on CICIDS2017 depends on the split; and (ii) reporting FAR alongside Recall is essential to balance missed attacks against analyst workload. Overall, a layered IDS that uses fast statistical models for coarse filtering and learned representations for refined decisions can leverage complementary strengths under realistic constraints.

4.4. Statistical Robustness and Uncertainty Quantification

4.4.1. Statistical Analysis on NSL-KDD

The statistical evaluation on the NSL-KDD dataset, presented in Table A18, reveals varying levels of stability across the tested models:

- High Stability in LR and NB: The Logistic Regression (LR) and Naïve Bayes (NB) models demonstrate extreme stability, particularly when run without SMOTE. Their SD values are negligible (SD < 0.0001 for most metrics), and the 95% CIs are extremely narrow (e.g., CIAcc. = [0.7443, 0.7443] for LR without SMOTE). This confirms that the deterministic results initially reported for these linear models are highly reliable.

- Hybrid Model Consistency: The Autoencoder-based hybrid models (LR + AE) also exhibit high consistency, showing low SD values (SDAcc. ≈ 0.0008) and tight 95% CIs. This indicates that the observed performance improvement from deep representation learning is statistically robust and consistent across different initialization states.

- Highest Instability in LDA: In contrast, the Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) model without SMOTE displays the highest sensitivity to the random seed. The SDAcc. is significantly higher (0.1390), resulting in a wide RangeAcc. of [0.5650, 0.7616]. This high variability suggests that while LDA can occasionally achieve high performance, its average performance and practical reliability on this dataset are inconsistent.

Overall, the statistical analysis confirms that the primary conclusions regarding the relative performance and stability of the models on NSL-KDD, especially the consistent performance of the LR + AE hybrid approach, are statistically sound and independent of the random seed, except for the volatile LDA model.

4.4.2. Statistical Analysis on CICIDS2017

The statistical assessment on the CICIDS2017 dataset, presented in Table A19, demonstrates a remarkably high degree of stability across all tested models:

- Near-Zero Variance Across All Models: Both classical and hybrid models exhibit exceptional consistency, with SD values generally below 0.0005 for key metrics like Accuracy, Precision, and F1-score. For instance, LR without SMOTE shows SD ≤ 0.0004 across all reported metrics. Even the deep learning-based LR + AE models, which typically have greater stochasticity, maintain very low SDs (SDAcc. ≤ 0.0005).

- Statistical Significance of Performance Differences: The clear and high separation in the mean performance between the top-performing models (e.g., LR without SMOTE with MeanAcc. = 0.9877) and the lower-performing classical models (e.g., LDA without SMOTE with MeanAcc. = 0.8529) is validated by the non-overlapping 95% CIs. This confirms that the ranking of models is statistically significant.

- Decisive Robustness: The very low uncertainty across the board confirms that the high detection quality (e.g., AUC ≥ 0.99 for top models) is an intrinsic and robust property of the models on the CICIDS2017 dataset.

These results are shown in Appendix B.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

This study presented a rigorous, reproducible comparison of three classical clas- sifiers—Naïve Bayes (NB), Logistic Regression (LR), and Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA)—and a hybrid deep-representation pipeline based on Autoencoder embeddings with a linear classifier (AE+LR). Using the NSL-KDD and CICIDS2017 benchmarks, we reported Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1, AUC, and False Alarm Rate (FAR), with all preprocessing and any class rebalancing (SMOTE) fit strictly on the training split. In addition, we measured wall-clock training and inference times for all four pipelines (Table 8), showing that NB, LR, and LDA train in seconds on NSL-KDD and in at most a few hundred seconds on CICIDS2017, while inference for all models, including AE+LR, remains well below one millisecond per flow, which is compatible with near real-time IDS operation on commodity hardware.

- What performed best and where.

On NSL-KDD, AE+LR and LDA offered the strongest overall trade-offs. AE+LR attained the highest AUC (≈0.904; Table 5) and the best F1 among the four models in both regimes (e.g., 0.7583 with SMOTE), while LDA slightly edged LR on Accuracy/F1 and AUC (e.g., F1 0.7537 vs. 0.7324 with SMOTE). NB achieved very high Precision (≈0.98) but very low Recall (≈0.24), yielding the weakest F1; its low FAR reflects a conservative decision boundary that misses many attacks.

On CICIDS2017, performance was strong for LR, LDA, and AE+LR. LR achieved the best Accuracy/F1 without SMOTE (0.9878/0.9752), with AE+LR a close second (0.9859/0.9715), and both near-ceiling AUC (≈0.996). NB again trailed due to a much higher FAR (≈0.18) and lower Precision, despite high Recall.

- The effect of class rebalancing.

Applying SMOTE to training data produced modest gains on NSL-KDD (where rare attacks are genuinely scarce), e.g., small F1 improvements for LDA and AE+LR with essentially unchanged FAR. In the unified binary split of CICIDS2017, SMOTE did not help and in some cases slightly reduced Accuracy/F1 while increasing FAR—consistent with mild overcompensation when the base class balance is already adequate.

- Practical implications.

For operators seeking transparent and lightweight deployment, LDA and LR remain strong, reproducible baselines. Where a small computational overhead is acceptable, AE+LR provides additional separability (highest AUC) and competitive F1 by leveraging an unsupervised representation while keeping a simple, auditable linear classifier. NB remains useful as a sanity-check baseline and for resource-constrained scenarios, but its low Recall on NSL-KDD cautions against relying on it as a stand-alone detector.

- Limitations.

Our primary focus was the binary setting; then, a complete multiclass analysis and cost-sensitive operating points were not the central objective here. In addition, AE was used strictly as a feature learner (not as a thresholded anomaly detector), so conclusions about reconstruction-threshold tuning are beyond scope.

Future Work

- Multiclass and cost-aware evaluation. Extend to full multiclass NSL-KDD with macro/micro metrics and per-class PR (Precision–Recall) curves; explore cost-sensitive thresholds (e.g., penalizing FNs (false negatives) for critical attacks).

- Non-linear classical baselines. Include Support Vector Machines (with kernels) and tree ensembles (Random Forest, Gradient Boosting) as non-linear yet interpretable tabular baselines.

- Representation learning variants. Compare AE with denoising/variational variants and different bottleneck sizes; quantify when AE+LR’s gains over LR/LDA justify the added cost.

- Imbalance strategies. Evaluate cost-sensitive learning, probability calibration, and focal-type objectives; compare SMOTE with alternatives such as Synthetic Minority Over-sampling Technique for Nominal and Continuous features (SMOTE-NC) and Adaptive Synthetic Sampling (ADASYN) and informed under-sampling.

- Cross-dataset generalization. Train on one domain and test on another (e.g., NSL-KDD → CICIDS2017 or the UNSW-NB15 intrusion detection dataset) with domain adaptation/transfer learning; examine robustness to concept drift.

- Operationalization and explainability. Integrate local explanations, such as Shapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) for LR/LDA and in the AE latent space, into alerting workflows; these additions extend our focus on operational transparency by enabling analysts to see which features drive individual alerts and to validate or refine decision policies accordingly.

- Reproducible pipelines. Release notebooks that regenerate all tables and reported metrics from predict_proba/decision_function; add regression tests to guard against library drift.

- Cross-dataset validation. Replicate the full pipeline on UNSW-NB15 and the CIC-IDS-2018 dataset from the Canadian Institute for Cybersecurity (CIC) and run train→test cross-domain transfers to assess robustness under dataset shift.

- Dataset fusion and harmonization. Explore concatenating harmonized feature-spaces from NSL-KDD and CICIDS2017 (with a domain indicator) to train unified models, and quantify trade-offs in Accuracy/FAR vs. domain shift. Evaluate whether AE-based representations ease cross-domain fusion.

- Overall, the results support a pragmatic recommendation: start with LR/LDA for simplicity and transparency, and adopt AE+LR when consistent separability gains (AUC) are desired without abandoning a linear, interpretable classifier. Careful use of imbalance remedies and alarm-centric metrics (Recall and FAR) is essential for reliable IDS deployment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, methodology, validation, investigation, and data curation, M.A.-A. and R.B.; writing—original draft preparation, A.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded and supported by Universidad Politécnica Salesiana.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed in this study are publicly available and can be accessed through the following repositories: (1) The NSL-KDD Intrusion Detection Dataset, generated by the Canadian Institute for Cybersecurity at the University of New Brunswick [], is available at: https://github.com/Jehuty4949/NSL_KDD (accessed on 11 February 2025). (2) The CICIDS2017 generated by the Canadian Institute for Cybersecurity at the University of New Brunswick []. An improved version is available at []: https://intrusion-detection.distrinet-research.be/CNS2022/CICIDS2017.html (accessed on 5 February 2025). A replication repository containing all source code and configuration files has been prepared and released in https://github.com/miguelarcosa/IDS-KDD-CICIDS2017.git [].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Confusion Matrices

Table A1.

Confusion matrix for Naïve Bayes (NB) on the NSL-KDD test set (without SMOTE).

Table A1.

Confusion matrix for Naïve Bayes (NB) on the NSL-KDD test set (without SMOTE).

| Predicted Normal | Predicted Attack | |

|---|---|---|

| Actual Normal | 9647 | 63 |

| Actual Attack | 9744 | 3088 |

Table A2.

Confusion matrix for Logistic Regression (LR) on the NSL-KDD test set (without SMOTE).

Table A2.

Confusion matrix for Logistic Regression (LR) on the NSL-KDD test set (without SMOTE).

| Predicted Normal | Predicted Attack | |

|---|---|---|

| Actual Normal | 8978 | 732 |

| Actual Attack | 5032 | 7800 |

Table A3.

Confusion matrix for Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) on the NSL-KDD test set (without SMOTE).

Table A3.

Confusion matrix for Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) on the NSL-KDD test set (without SMOTE).

| Predicted Normal | Predicted Attack | |

|---|---|---|

| Actual Normal | 9051 | 659 |

| Actual Attack | 4714 | 8118 |

Table A4.

Confusion matrix for Autoencoder + LR (AE+LR) on the NSL-KDD test set (without SMOTE).

Table A4.

Confusion matrix for Autoencoder + LR (AE+LR) on the NSL-KDD test set (without SMOTE).

| Predicted Normal | Predicted Attack | |

|---|---|---|

| Actual Normal | 9021 | 689 |

| Actual Attack | 4583 | 8249 |

Table A5.

Confusion matrix for Naïve Bayes (NB) on the NSL-KDD test set (with SMOTE on training data).

Table A5.

Confusion matrix for Naïve Bayes (NB) on the NSL-KDD test set (with SMOTE on training data).

| Predicted Normal | Predicted Attack | |

|---|---|---|

| Actual Normal | 9647 | 63 |

| Actual Attack | 9742 | 3090 |

Table A6.

Confusion matrix for Logistic Regression (LR) on the NSL-KDD test set (with SMOTE on training data).

Table A6.

Confusion matrix for Logistic Regression (LR) on the NSL-KDD test set (with SMOTE on training data).

| Predicted Normal | Predicted Attack | |

|---|---|---|

| Actual Normal | 8969 | 741 |

| Actual Attack | 4989 | 7843 |

Table A7.

Confusion matrix for Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) on the NSL-KDD test set (with SMOTE on training data).

Table A7.

Confusion matrix for Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) on the NSL-KDD test set (with SMOTE on training data).

| Predicted Normal | Predicted Attack | |

|---|---|---|

| Actual Normal | 9036 | 674 |

| Actual Attack | 4664 | 8168 |

Table A8.

Confusion matrix for Autoencoder + LR (AE+LR) on the NSL-KDD test set (with SMOTE on training data).

Table A8.

Confusion matrix for Autoencoder + LR (AE+LR) on the NSL-KDD test set (with SMOTE on training data).

| Predicted Normal | Predicted Attack | |

|---|---|---|

| Actual Normal | 8955 | 755 |

| Actual Attack | 4534 | 8298 |

Table A9.

Confusion matrix for Naïve Bayes (NB) on the CICIDS2017 test set (without SMOTE).

Table A9.

Confusion matrix for Naïve Bayes (NB) on the CICIDS2017 test set (without SMOTE).

| Predicted Normal | Predicted Attack | |

|---|---|---|

| Actual Normal | 258,924 | 57,590 |

| Actual Attack | 2668 | 100,814 |

Table A10.

Confusion matrix for Logistic Regression (LR) on the CICIDS2017 test set (without SMOTE).

Table A10.

Confusion matrix for Logistic Regression (LR) on the CICIDS2017 test set (without SMOTE).

| Predicted Normal | Predicted Attack | |

|---|---|---|

| Actual Normal | 313,619 | 2895 |

| Actual Attack | 2245 | 101,237 |

Table A11.

Confusion matrix for Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) on the CICIDS2017 test set (without SMOTE).

Table A11.

Confusion matrix for Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) on the CICIDS2017 test set (without SMOTE).

| Predicted Normal | Predicted Attack | |

|---|---|---|

| Actual Normal | 310,397 | 6117 |

| Actual Attack | 2950 | 100,532 |

Table A12.

Confusion matrix for Autoencoder + LR (AE+LR) on the CICIDS2017 test set (without SMOTE).

Table A12.

Confusion matrix for Autoencoder + LR (AE+LR) on the CICIDS2017 test set (without SMOTE).

| Predicted Normal | Predicted Attack | |

|---|---|---|

| Actual Normal | 313,306 | 3208 |

| Actual Attack | 2709 | 100,773 |

Table A13.

Confusion matrix for Naïve Bayes (NB) on the CICIDS2017 test set (with SMOTE on training data).

Table A13.

Confusion matrix for Naïve Bayes (NB) on the CICIDS2017 test set (with SMOTE on training data).

| Predicted Normal | Predicted Attack | |

|---|---|---|

| Actual Normal | 258,862 | 57,652 |

| Actual Attack | 2671 | 100,811 |

Table A14.

Confusion matrix for Logistic Regression (LR) on the CICIDS2017 test set (with SMOTE on training data).

Table A14.

Confusion matrix for Logistic Regression (LR) on the CICIDS2017 test set (with SMOTE on training data).

| Predicted Normal | Predicted Attack | |

|---|---|---|

| Actual Normal | 312,536 | 3978 |

| Actual Attack | 1817 | 101,665 |

Table A15.

Confusion matrix for Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) on the CICIDS2017 test set (with SMOTE on training data).

Table A15.

Confusion matrix for Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) on the CICIDS2017 test set (with SMOTE on training data).

| Predicted Normal | Predicted Attack | |

|---|---|---|

| Actual Normal | 307,136 | 9378 |

| Actual Attack | 1755 | 101,727 |

Table A16.

Confusion matrix for Autoencoder + LR (AE+LR) on the CICIDS2017 test set (with SMOTE on training data).

Table A16.

Confusion matrix for Autoencoder + LR (AE+LR) on the CICIDS2017 test set (with SMOTE on training data).

| Predicted Normal | Predicted Attack | |

|---|---|---|

| Actual Normal | 310,363 | 6151 |

| Actual Attack | 2016 | 101,466 |

Appendix B. Execution Times

Full Experiments Set Using Random Seed Values

Table A17.

Results of execution of classification models with multiple random seeds (Raw Data).

Table A17.

Results of execution of classification models with multiple random seeds (Raw Data).

| Model | Seed | NSL-KDD | CICIDS2017 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acc. | Prec. | Rec. | F1 | FAR | AUC | Acc. | Prec. | Rec. | F1 | FAR | AUC | ||

| Logistic Regresion (LR) without SMOTE | 42 | 0.7443 | 0.9142 | 0.6079 | 0.7302 | 0.0754 | 0.8276 | 0.9878 | 0.9722 | 0.9783 | 0.9752 | 0.0091 | 0.9961 |

| 94 | 0.7443 | 0.9142 | 0.6079 | 0.7302 | 0.0754 | 0.8276 | 0.9875 | 0.9716 | 0.9780 | 0.9748 | 0.0093 | 0.9957 | |

| 112 | 0.7443 | 0.9142 | 0.6079 | 0.7302 | 0.0754 | 0.8276 | 0.9877 | 0.9722 | 0.9781 | 0.9751 | 0.0091 | 0.9957 | |

| 209 | 0.7443 | 0.9142 | 0.6079 | 0.7302 | 0.0754 | 0.8276 | 0.9876 | 0.9725 | 0.9775 | 0.9750 | 0.0090 | 0.9954 | |

| Logistic Regresion (LR) with SMOTE | 42 | 0.7458 | 0.9137 | 0.6112 | 0.7324 | 0.0763 | 0.8227 | 0.9862 | 0.9623 | 0.9824 | 0.9723 | 0.0126 | 0.9962 |

| 94 | 0.7471 | 0.9135 | 0.6133 | 0.7343 | 0.0768 | 0.8235 | 0.9857 | 0.9609 | 0.9822 | 0.9714 | 0.0131 | 0.9962 | |

| 112 | 0.7456 | 0.9134 | 0.6110 | 0.7322 | 0.0765 | 0.8221 | 0.9855 | 0.9609 | 0.9813 | 0.9710 | 0.0131 | 0.9962 | |

| 209 | 0.7447 | 0.9130 | 0.6096 | 0.7311 | 0.0767 | 0.8224 | 0.9859 | 0.9615 | 0.9819 | 0.9716 | 0.0128 | 0.9961 | |

| Naïve Bayes (NB) without SMOTE | 42 | 0.5649 | 0.9800 | 0.2406 | 0.3864 | 0.0065 | 0.7987 | 0.8565 | 0.6364 | 0.9742 | 0.7699 | 0.1820 | 0.9711 |

| 94 | 0.5649 | 0.9800 | 0.2406 | 0.3864 | 0.0065 | 0.7987 | 0.8510 | 0.6273 | 0.9744 | 0.7632 | 0.1893 | 0.9586 | |

| 112 | 0.5649 | 0.9800 | 0.2406 | 0.3864 | 0.0065 | 0.7987 | 0.8568 | 0.6370 | 0.9742 | 0.7703 | 0.1815 | 0.9734 | |

| 209 | 0.5649 | 0.9800 | 0.2406 | 0.3864 | 0.3864 | 0.7987 | 0.8520 | 0.6288 | 0.9749 | 0.7645 | 0.1881 | 0.9606 | |

| Naïve Bayes (NB) with SMOTE | 42 | 0.5650 | 0.9800 | 0.2408 | 0.3866 | 0.0065 | 0.7978 | 0.8564 | 0.6362 | 0.9742 | 0.7697 | 0.1821 | 0.9686 |

| 94 | 0.5650 | 0.9800 | 0.2407 | 0.3865 | 0.0065 | 0.7983 | 0.8494 | 0.6246 | 0.9744 | 0.7612 | 0.1915 | 0.9481 | |

| 112 | 0.5650 | 0.9800 | 0.2408 | 0.3866 | 0.0065 | 0.7984 | 0.8561 | 0.6357 | 0.9742 | 0.7694 | 0.1825 | 0.9682 | |

| 209 | 0.5650 | 0.9800 | 0.2408 | 0.3866 | 0.0065 | 0.7971 | 0.8502 | 0.6258 | 0.9749 | 0.7623 | 0.1906 | 0.9416 | |

| LDA without SMOTE | 42 | 0.7616 | 0.9249 | 0.6326 | 0.7514 | 0.0679 | 0.8484 | 0.9784 | 0.9426 | 0.9715 | 0.9569 | 0.0193 | 0.9923 |

| 94 | 0.7616 | 0.9249 | 0.6326 | 0.7514 | 0.0679 | 0.8484 | 0.9777 | 0.9415 | 0.9698 | 0.9555 | 0.0197 | 0.9919 | |

| 112 | 0.7616 | 0.9249 | 0.6326 | 0.7514 | 0.0679 | 0.8484 | 0.9779 | 0.9413 | 0.9710 | 0.9559 | 0.0198 | 0.9919 | |

| 209 | 0.7616 | 0.9249 | 0.6326 | 0.7514 | 0.0679 | 0.8484 | 0.9777 | 0.9415 | 0.9699 | 0.9555 | 0.0197 | 0.9917 | |

| LDA with SMOTE | 42 | 0.7632 | 0.9238 | 0.6365 | 0.7537 | 0.0694 | 0.9043 | 0.9735 | 0.9156 | 0.9830 | 0.9481 | 0.0296 | 0.9924 |

| 94 | 0.7634 | 0.9240 | 0.6368 | 0.7540 | 0.0692 | 0.8504 | 0.9728 | 0.9127 | 0.9835 | 0.9468 | 0.0307 | 0.9920 | |

| 112 | 0.7620 | 0.9134 | 0.6428 | 0.7546 | 0.0805 | 0.9059 | 0.9729 | 0.9135 | 0.9831 | 0.9470 | 0.0304 | 0.9920 | |

| 209 | 0.7632 | 0.9238 | 0.6365 | 0.7537 | 0.0694 | 0.8477 | 0.9724 | 0.9122 | 0.9828 | 0.9462 | 0.0309 | 0.9917 | |

| LR + AE without SMOTE | 42 | 0.7616 | 0.9165 | 0.6397 | 0.7534 | 0.0770 | 0.9040 | 0.9859 | 0.9691 | 0.9738 | 0.9715 | 0.0101 | 0.9960 |

| 94 | 0.7701 | 0.9645 | 0.6188 | 0.7540 | 0.0301 | 0.9176 | 0.9864 | 0.9738 | 0.9710 | 0.9724 | 0.0085 | 0.9956 | |

| 112 | 0.7563 | 0.9134 | 0.6319 | 0.7470 | 0.0792 | 0.8824 | 0.9846 | 0.9710 | 0.9665 | 0.9688 | 0.0094 | 0.9946 | |

| 209 | 0.7599 | 0.9184 | 0.6347 | 0.7506 | 0.0746 | 0.8962 | 0.9825 | 0.9648 | 0.9642 | 0.9645 | 0.0115 | 0.9939 | |

| LR + AE with SMOTE | 42 | 0.7654 | 0.9166 | 0.6467 | 0.7583 | 0.0778 | 0.9043 | 0.9806 | 0.9428 | 0.9805 | 0.9613 | 0.0194 | 0.9954 |

| 94 | 0.7840 | 0.9638 | 0.6449 | 0.7727 | 0.0320 | 0.9203 | 0.9809 | 0.9443 | 0.9805 | 0.9621 | 0.0189 | 0.9955 | |

| 112 | 0.7622 | 0.9133 | 0.6434 | 0.7549 | 0.0807 | 0.8818 | 0.9788 | 0.9410 | 0.9752 | 0.9578 | 0.0200 | 0.9948 | |

| 209 | 0.7620 | 0.9171 | 0.6398 | 0.7538 | 0.0764 | 0.8952 | 0.9799 | 0.9411 | 0.9799 | 0.9601 | 0.0201 | 0.9938 | |

Table A18.

Descriptive Statistics for multi-seed experiments on the NSL-KDD dataset (mean, standard deviation, 95% confidence intervals, and ranges).

Table A18.

Descriptive Statistics for multi-seed experiments on the NSL-KDD dataset (mean, standard deviation, 95% confidence intervals, and ranges).

| Model | Statistic | Metric | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acc. | Prec. | Rec. | F1 | FAR | AUC | ||

| Logistic Regresion (LR) without SMOTE | Mean | 0.7443 | 0.9142 | 0.6079 | 0.7302 | 0.0754 | 0.8276 |

| SD | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | |

| 95% CI | [0.7443, 0.7443] | [0.9142, 0.9142] | [0.6079, 0.6079] | [0.7302, 0.7302] | [0.0754, 0.0754] | [0.8276, 0.8276] | |

| Range | [0.7443, 0.7443] | [0.9142, 0.9142] | [0.6079, 0.6079] | [0.7302, 0.7302] | [0.0754, 0.0754] | [0.8276, 0.8276] | |

| Logistic Regresion (LR) with SMOTE | Mean | 0.7458 | 0.9134 | 0.6106 | 0.7325 | 0.0766 | 0.8227 |

| SD | 0.0010 | 0.0003 | 0.0009 | 0.0013 | 0.0002 | 0.0006 | |

| 95% CI | [0.7442, 0.7474] | [0.9129, 0.9139] | [0.6092, 0.6120] | [0.7304, 0.7346] | [0.0762, 0.0769] | [0.8217, 0.8236] | |

| Range | [0.7447, 0.7471] | [0.9130, 0.9137] | [0.6096, 0.6112] | [0.7311, 0.7343] | [0.0763, 0.0768] | [0.8221, 0.8235] | |

| Naïve Bayes (NB) without SMOTE | Mean | 0.5649 | 0.9800 | 0.2406 | 0.3864 | 0.0065 | 0.7987 |

| SD | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | |

| 95% CI | [0.5649, 0.5649] | [0.9800, 0.9800] | [0.2406, 0.2406] | [0.3864, 0.3864] | [0.0065, 0.0065] | [0.7987, 0.7987] | |

| Range | [0.5649, 0.5649] | [0.9800, 0.9800] | [0.2406, 0.2406] | [0.3864, 0.3864] | [0.0065, 0.0065] | [0.7987, 0.7987] | |

| Naïve Bayes (NB) with SMOTE | Mean | 0.5650 | 0.9800 | 0.2407 | 0.3866 | 0.0065 | 0.7980 |

| SD | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0000 | 0.0004 | |

| 95% CI | [0.5650, 0.5650] | [0.9800, 0.9800] | [0.2406, 0.2409] | [0.3864, 0.3867] | [0.0065, 0.0065] | [0.7975, 0.7986] | |

| Range | [0.5650, 0.5650] | [0.9800, 0.9800] | [0.2407, 0.2408] | [0.3865, 0.3866] | [0.0065, 0.0065] | [0.7978, 0.7983] | |

| LDA without SMOTE | Mean | 0.6633 | 0.9525 | 0.4367 | 0.5690 | 0.0372 | 0.8228 |

| SD | 0.1390 | 0.0390 | 0.2770 | 0.2580 | 0.0434 | 0.0363 | |

| 95% CI | [0.4421, 0.8845] | [0.8905, 1.0144] | [−0.0041, 0.8775] | [0.1586, 0.9794] | [−0.0319, 0.1063] | [0.7650, 0.8805] | |

| Range | [0.5650, 0.7616] | [0.9249, 0.9800] | [0.2408, 0.6326] | [0.3866, 0.7514] | [0.0065, 0.0679] | [0.7971, 0.8484] | |

| LDA with SMOTE | Mean | 0.7616 | 0.9249 | 0.6326 | 0.7514 | 0.0679 | 0.8484 |

| SD | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | |

| 95% CI | [0.7616, 0.7616] | [0.9249, 0.9249] | [0.6326, 0.6326] | [0.7514, 0.7514] | [0.0679, 0.0679] | [0.8484, 0.8484] | |

| Range | [0.7616, 0.7616] | [0.9249, 0.9249] | [0.6326, 0.6326] | [0.7514, 0.7514] | [0.0679, 0.0679] | [0.8484, 0.8484] | |

| LR + AE without SMOTE | Mean | 0.7629 | 0.9204 | 0.6387 | 0.7541 | 0.0730 | 0.8680 |

| SD | 0.0008 | 0.0061 | 0.0036 | 0.0005 | 0.0065 | 0.0329 | |

| 95% CI | [0.7617, 0.7641] | [0.9108, 0.9300] | [0.6330, 0.6444] | [0.7534, 0.7548] | [0.0627, 0.0833] | [0.8157, 0.9203] | |

| Range | [0.7620, 0.7634] | [0.9134, 0.9240] | [0.6365, 0.6428] | [0.7537, 0.7546] | [0.0692, 0.0805] | [0.8477, 0.9059] | |

| LR + AE with SMOTE | Mean | 0.7620 | 0.9282 | 0.6313 | 0.7512 | 0.0652 | 0.9001 |

| SD | 0.0059 | 0.0243 | 0.0089 | 0.0032 | 0.0235 | 0.0147 | |

| 95% CI | [0.7527, 0.7713] | [0.8896, 0.9668] | [0.6171, 0.6455] | [0.7462, 0.7563] | [0.0278, 0.1026] | [0.8766, 0.9235] | |

| Range | [0.7563, 0.7701] | [0.9134, 0.9645] | [0.6188, 0.6397] | [0.7470, 0.7540] | [0.0301, 0.0792] | [0.8824, 0.9176] | |

Table A19.

Descriptive statistics for multi-seed experiments on the CICIDS2017 dataset (mean, standard deviation, 95% confidence intervals, and ranges).

Table A19.

Descriptive statistics for multi-seed experiments on the CICIDS2017 dataset (mean, standard deviation, 95% confidence intervals, and ranges).

| Model | Statistic | Metric | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acc. | Prec. | Rec. | F1 | FAR | AUC | ||

| Logistic Regresion (LR) without SMOTE | Mean | 0.9877 | 0.9721 | 0.9780 | 0.9750 | 0.0091 | 0.9957 |

| SD | 0.0001 | 0.0004 | 0.0003 | 0.0002 | 0.0001 | 0.0003 | |

| 95% CI | [0.9874, 0.9879] | [0.9715, 0.9727] | [0.9774, 0.9785] | [0.9748, 0.9753] | [0.0089, 0.0093] | [0.9953, 0.9962] | |

| Range | [0.9875, 0.9878] | [0.9716, 0.9725] | [0.9775, 0.9783] | [0.9748, 0.9752] | [0.0090, 0.0093] | [0.9954, 0.9961] | |

| Logistic Regresion (LR) with SMOTE | Mean | 0.9859 | 0.9616 | 0.9823 | 0.9719 | 0.0129 | 0.9962 |

| SD | 0.0004 | 0.0010 | 0.0001 | 0.0006 | 0.0004 | 0.0000 | |

| 95% CI | [0.9854, 0.9865] | [0.9600, 0.9632] | [0.9821, 0.9825] | [0.9708, 0.9729] | [0.0123, 0.0134] | [0.9962, 0.9962] | |

| Range | [0.9857, 0.9862] | [0.9609, 0.9623] | [0.9822, 0.9824] | [0.9714, 0.9723] | [0.0126, 0.0131] | [0.9962, 0.9962] | |

| Naïve Bayes (NB) without SMOTE | Mean | 0.9857 | 0.9612 | 0.9816 | 0.9713 | 0.0129 | 0.9961 |

| SD | 0.0003 | 0.0004 | 0.0004 | 0.0004 | 0.0002 | 0.0001 | |

| 95% CI | [0.9852, 0.9862] | [0.9605, 0.9619] | [0.9809, 0.9823] | [0.9706, 0.9720] | [0.0126, 0.0133] | [0.9960, 0.9963] | |

| Range | [0.9855, 0.9859] | [0.9609, 0.9615] | [0.9813, 0.9819] | [0.9710, 0.9716] | [0.0128, 0.0131] | [0.9961, 0.9962] | |

| Naïve Bayes (NB) with SMOTE | Mean | 0.8541 | 0.6324 | 0.9744 | 0.7670 | 0.1852 | 0.9659 |

| SD | 0.0030 | 0.0050 | 0.0003 | 0.0037 | 0.0040 | 0.0074 | |

| 95% CI | [0.8493, 0.8589] | [0.6244, 0.6404] | [0.9739, 0.9750] | [0.7612, 0.7728] | [0.1788, 0.1917] | [0.9541, 0.9777] | |

| Range | [0.8510, 0.8568] | [0.6273, 0.6370] | [0.9742, 0.9749] | [0.7632, 0.7703] | [0.1815, 0.1893] | [0.9586, 0.9734] | |

| LDA without SMOTE | Mean | 0.8529 | 0.6304 | 0.9743 | 0.7654 | 0.1868 | 0.9584 |

| SD | 0.0049 | 0.0082 | 0.0001 | 0.0060 | 0.0066 | 0.0145 | |

| 95% CI | [0.8450, 0.8608] | [0.6173, 0.6435] | [0.9741, 0.9745] | [0.7559, 0.7750] | [0.1762, 0.1974] | [0.9353, 0.9814] | |

| Range | [0.8494, 0.8564] | [0.6246, 0.6362] | [0.9742, 0.9744] | [0.7612, 0.7697] | [0.1821, 0.1915] | [0.9481, 0.9686] | |

| LDA with SMOTE | Mean | 0.8531 | 0.6308 | 0.9746 | 0.7658 | 0.1865 | 0.9549 |

| SD | 0.0042 | 0.0070 | 0.0005 | 0.0050 | 0.0057 | 0.0188 | |

| 95% CI | [0.8465, 0.8598] | [0.6196, 0.6419] | [0.9738, 0.9753] | [0.7579, 0.7738] | [0.1774, 0.1957] | [0.9250, 0.9848] | |

| Range | [0.8502, 0.8561] | [0.6258, 0.6357] | [0.9742, 0.9749] | [0.7623, 0.7694] | [0.1825, 0.1906] | [0.9416, 0.9682] | |

| LR + AE without SMOTE | Mean | 0.9779 | 0.9417 | 0.9706 | 0.9559 | 0.0196 | 0.9919 |

| SD | 0.0003 | 0.0006 | 0.0008 | 0.0007 | 0.0002 | 0.0003 | |

| 95% CI | [0.9774, 0.9785] | [0.9408, 0.9427] | [0.9692, 0.9719] | [0.9549, 0.9570] | [0.0193, 0.0200] | [0.9915, 0.9924] | |

| Range | [0.9777, 0.9784] | [0.9413, 0.9426] | [0.9698, 0.9715] | [0.9555, 0.9569] | [0.0193, 0.0198] | [0.9917, 0.9923] | |

| LR + AE with SMOTE | Mean | 0.9731 | 0.9142 | 0.9832 | 0.9475 | 0.0302 | 0.9922 |

| SD | 0.0005 | 0.0021 | 0.0004 | 0.0009 | 0.0008 | 0.0003 | |

| 95% CI | [0.9724, 0.9739] | [0.9109, 0.9174] | [0.9827, 0.9838] | [0.9460, 0.9489] | [0.0289, 0.0314] | [0.9917, 0.9927] | |

| Range | [0.9728, 0.9735] | [0.9127, 0.9156] | [0.9830, 0.9835] | [0.9468, 0.9481] | [0.0296, 0.0307] | [0.9920, 0.9924] | |

References

- Ali, M.L.; Thakur, K.; Schmeelk, S.; Debello, J.; Dragos, D. Deep Learning vs. Machine Learning for Intrusion Detection in Computer Networks: A Comparative Study. Appl. Sci. 1903, 15, 1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, D.K.; Kalita, H.K. Enhanced deep autoencoder-based reinforcement learning model with improved flamingo search policy selection for attack classification. J. Cybersecur. Priv. 2025, 5, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhamahmy, M.; Ibrahim, M.; Elsabagh, M.; Keshk, H. Improving intrusion detection using LSTM-RNN to protect drones’ networks. Egypt. Inform. J. 2024, 27, 637–648. [Google Scholar]

- Tayeh, T.; Aburakhia, S.; Myers, R.; Shami, A. An Attention-Based ConvLSTM Autoencoder with Dynamic Thresholding for Unsupervised Anomaly Detection in Multivariate Time Series. Mach. Learn. Knowl. Extr. 2022, 4, 350–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewandowski, B.; Paffenroth, R. Autoencoder Feature Residuals for Network Intrusion Detection: One-Class Pretraining for Improved Performance. Mach. Learn. Knowl. Extr. 2023, 5, 868–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandi, K.; García-Dopico, A. Enhancing Performance of Credit Card Model by Utilizing LSTM Networks and XGBoost Algorithms. Mach. Learn. Knowl. Extr. 2025, 7, 20–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, N.; Chakravarty, S.; Rath, A.K.; Giri, N.C.; Gowtham, N. An optimized LSTM-based deep learning model for anomaly network intrusion detection. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacevicius, M.; Paulauskaite-Taraseviciene, A.; Zokaityte, G.; Kersys, L.; Moleikaityte, A. Comparative Analysis of Perturbation Techniques in LIME for Intrusion Detection Enhancement. Mach. Learn. Knowl. Extr. 2025, 7, 21–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, L.; Tian, Z.; Huang, H.; Li, X.; Yin, Z.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, N.; Zhai, W. Heterogeneous Secure Transmissions in IRS-Assisted NOMA Communications: CO-GNN Approach. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 34113–34125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, Q.; Hina, S.; Sajjad, H.; Zaidi, K.S.; Akbar, R. Optimization of predictive performance of intrusion detection system using hybrid ensemble model for secure systems. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2023, 9, e1552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Institute for Cybersecurity (CIC); University of New Brunswick. NSL-KDD Intrusion Detection Dataset. Available online: https://github.com/Jehuty4949/NSL_KDD (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Canadian Institute for Cybersecurity. CICIDS2017 Dataset. University of New Brunswick. 2017. Available online: https://www.unb.ca/cic/datasets/ids-2017.html (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Fuhr, J.; Wang, F.; Tang, Y. MOCA: A network intrusion monitoring and classification system. J. Cybersecur. Priv. 2022, 2, 629–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Lu, S. An effective intrusion detection approach using SVM with naïve Bayes feature embedding. Comput. Secur. 2021, 103, 102158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasotha, B.; Sasikala, T.; Krishnamurthy, M. Wrapper Based Linear Discriminant Analysis (LDA) for Intrusion Detection in IIoT. Comput. Syst. Sci. Eng. 2023, 45, 1625–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghani, H.; Virdee, B.; Salekzamankhani, S. A deep learning approach for network intrusion detection using a small features vector. J. Cybersecur. Priv. 2023, 3, 451–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calle, J.; Bojorque, R.; Plaza, A.; Morquecho, P. Detection of DDoS Attacks in Computer Networks Using Deep Learning. Commun. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2024, 2392, 291–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Hyun, S.; Cheong, Y.-G. Analysis of Autoencoders for Network Intrusion Detection. Sensors 2021, 21, 4294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Jang-Jaccard, J.; Singh, A.; Wei, Y.; Sabrina, F. Improving performance of autoencoder-based network anomaly detection on NSL-KDD dataset. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 140136–140146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, S.; Li, J.; Choi, B.-J.; Bai, Y. A lightweight supervised intrusion detection mechanism for IoT networks. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2022, 127, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza, C.A.; Westphall, C.B.; Machado, R.B. Two-step ensemble approach for intrusion detection and identification in IoT and fog computing environments. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2022, 98, 107694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, N.; Jindal, V.; Bedi, P.B. CSE-IDS: Using cost-sensitive deep learning and ensemble algorithms to handle class imbalance in network-based intrusion detection systems. Comput. Secur. 2022, 112, 102499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, S. A Comprehensive Survey on Intrusion Detection Algorithms. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2025, 121, 109863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharafaldin, I.; Lashkari, A.H.; Ghorbani, A.A. Toward generating a new intrusion detection dataset and intrusion traffic characterization. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference Information Systems Security and Privacy (ICISSP), Madeira, Portugal, 22–24 January 2018; pp. 108–116. [Google Scholar]

- Sayegh, K.; Khanduja, S.; Holt, A.G.J. Enhanced Intrusion Detection with LSTM-Based Model, Feature Selection, and SMOTE for Imbalanced Data. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, F.; Wen, S.; Nepal, S.; Paris, C.; Xiang, Y. Explainable Machine Learning in Cybersecurity: A Survey. Int. J. Intell. Syst. 2022, 37, 12305–12334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azar, A.T.; Shehab, E.; Mattar, A.M.; Hameed, I.A.; Elsaid, S.A. Deep Learning Based Hybrid Intrusion Detection Systems to Protect Satellite Networks. J. Netw. Syst. Manag. 2023, 31, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulhammed, R.; Musafer, H.; Alessa, A.; Faezipour, M.; Abuzneid, A. Features Dimensionality Reduction Approaches for Machine Learning Based Network Intrusion Detection. Electronics 2019, 8, 322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scikit-Learn: Documentation for LinearDiscriminantAnalysis. Scikit-Learn Project 2025, Stable. Available online: https://scikit-learn.org/stable/modules/generated/sklearn.discriminant_analysis.LinearDiscriminantAnalysis.html (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Arcos, M. IDS-KDD-CICIDS2017. GitHub Repository. 2025. Available online: https://github.com/miguelarcosa/IDS-KDD-CICIDS2017.git (accessed on 1 November 2025).

- Umer, Z.; Abbasi, A.A. A two-stage intrusion detection system with autoencoder and LSTMs. Appl. Soft Comput. 2022, 121, 108768. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, A.; Fu, Y.; Zheng, X. An efficient network behavior anomaly detection using a hybrid DBN-LSTM network. Comput. Secur. 2022, 114, 102600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Engelen, G.; Lynar, T.; Essam, D.; Joosen, W. Error Prevalence in NIDS Datasets: A Case Study on CIC-IDS-2017 and CSE-CIC-IDS-2018. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Communications and Network Security (CNS), Taipei, Taiwan, 30 September–3 October 2022; pp. 254–262. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).