Policy Synergy Scenarios for Tokyo’s Passenger Transport and Urban Freight: An Integrated Multi-Model LEAP Assessment

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Building a systematic forecasting and evaluation framework.

- Evaluating the impact of different policy pathways on carbon emissions in Tokyo’s transport sector.

- Identify the key drivers to achieve deep emissions reductions and carbon neutrality.

- Providing quantitative support and scenario analysis for Tokyo to achieve its carbon neutrality goal by 2050.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Theoretical Foundation

2.2. Data Source and Variable Settings

- Socioeconomic variables (Data source: Tokyo Metropolitan Statistical Yearbook) [22]: GDP, population, employment, road length, vehicle stock.

- Transport activity variables: Annual turnover of railway, bus, taxi, ordinary truck and minivan.

- Energy and technology variables: Energy intensity (EI), energy structure (energy share), emission factor (EF), etc.

2.3. Variable Prediction Models

- Time series models were used to predict socioeconomic variables (Employment, road length and vehicle stock).

- Multiple regression models (MLR) and generalized linear models (GLM) were used to predict the activity levels (turnover) of various transportation modes.

2.3.1. Time Series Model

2.3.2. Multiple Regression Models

2.4. LEAP Model Construction and Scenario Design

2.4.1. System Boundary

2.4.2. Calculation Formula

2.4.3. Scenario Design

- (1)

- Baseline scenario (Business-as-Usual, BAU)

- (2)

- Energy structure optimization scenario (A)

- (3)

- Emission factors optimization scenario (B)

- (4)

- Energy intensity optimization scenario (C)

- (5)

- Scenario combination and integrated analysis design

2.4.4. Sensitivity Analysis Settings

3. Results

3.1. Socioeconomic Factors and Traffic Turnover Forecast Results

3.1.1. Forecasting Results of Time Series Models

- (1)

- Employment

- (2)

- Road length

- (3)

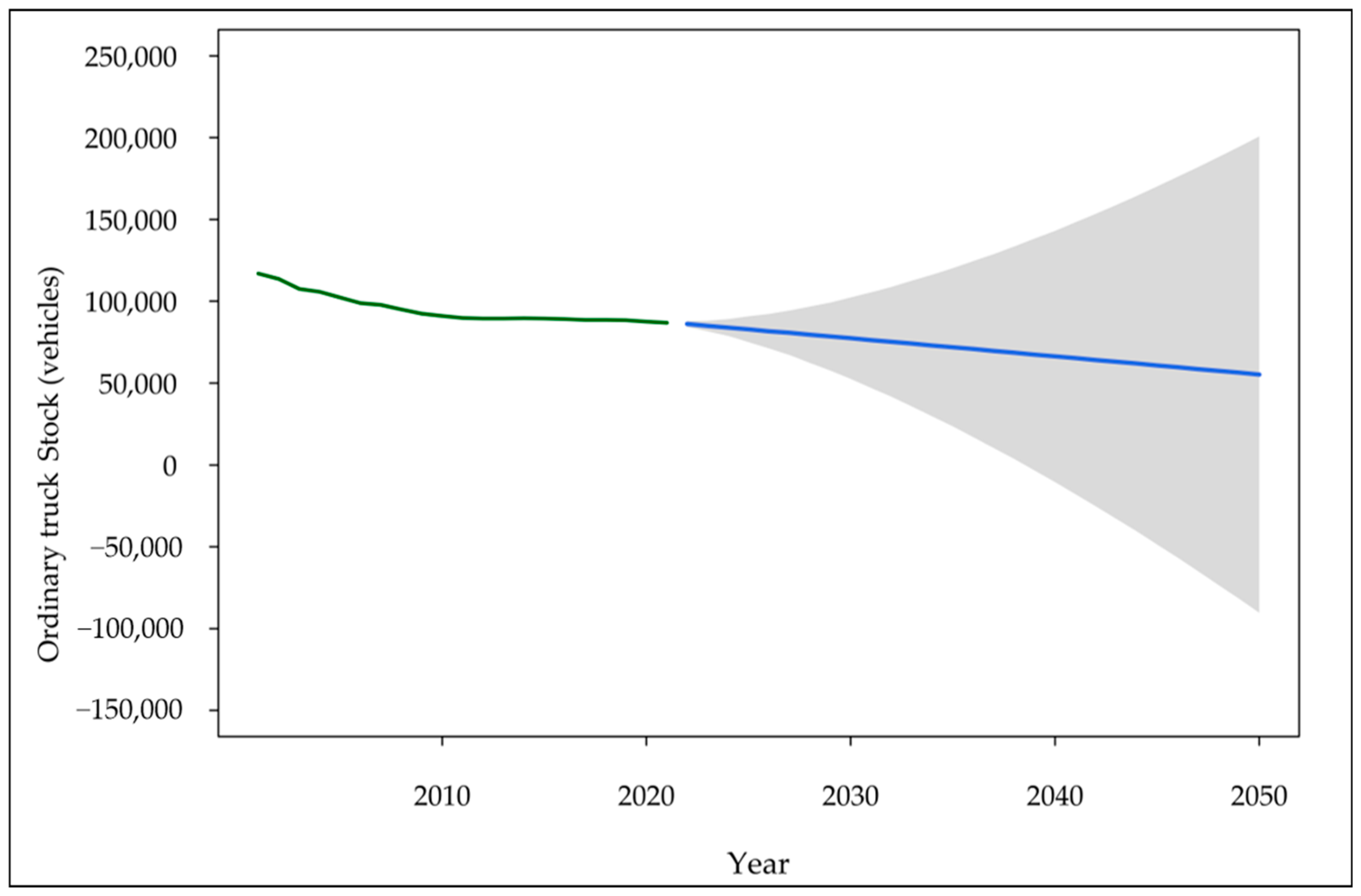

- Ordinary truck stock

- (4)

- Minivan stock

3.1.2. Forecasting Results of Regression Models

- (1)

- Railway turnover

- (2)

- Bus turnover

- (3)

- Taxi turnover

- (4)

- Ordinary truck turnover

- (5)

- Minivan turnover

3.2. LEAP Model Scenario Analysis Results

3.2.1. Comparative Analysis of Single-Factor Scenarios

3.2.2. Comparative Analysis of Multi-Factor Scenarios

3.2.3. Emission Reduction Characteristics by Sector

3.3. Univariate Sensitivity Analysis Results

4. Discussion and Conclusions

4.1. Timing Optimization of Multi-Policy Coordination

4.2. Industry and Spatial Differences: Characteristics and Significance of Bus and Freight Emission Reduction in Tokyo

4.3. Demand and Substitution: Primarily Structural Adjustment

4.4. Contributions and Limitations

4.5. Transferability and Boundary Conditions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| LEAP | Long-range Energy Alternatives Planning |

| ZEV | Zero-Emission Vehicle |

| ASI | Avoid-Shift-Improve |

| SDGs | Sustainable Development Goals |

| EF | Emission Factor |

| EI | Energy Intensity |

| MLR | Multiple Linear Regression |

| GLM | Generalized Linear Model |

Appendix A. Socioeconomic Data

Appendix A.1. Population

| Year | Population (Person) | Growth Rate |

|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 7,967,602 | |

| 2002 | 8,023,202 | |

| 2003 | 8,081,959 | |

| 2004 | 8,129,801 | |

| 2005 | 8,183,907 | |

| 2006 | 8,247,810 | |

| 2007 | 8,318,841 | |

| 2008 | 8,387,659 | |

| 2009 | 8,451,067 | |

| 2010 | 8,502,527 | |

| 2011 | 8,541,979 | |

| 2012 | 8,575,228 | |

| 2013 | 8,951,575 | |

| 2014 | 9,016,342 | |

| 2015 | 9,102,598 | |

| 2016 | 9,205,712 | |

| 2017 | 9,302,962 | |

| 2018 | 9,396,595 | |

| 2019 | 9,486,618 | |

| 2020 | 9,570,609 | |

| 2021 | 9,572,763 | |

| 2022 | 9,678,063 | 1.10% |

| 2023 | 9,784,522 | 1.10% |

| 2024 | 9,892,152 | 1.10% |

| 2025 | 10,000,966 | 1.10% |

| 2026 | 10,110,977 | 1.10% |

| 2027 | 10,222,198 | 1.10% |

| 2028 | 10,334,642 | 1.10% |

| 2029 | 10,448,323 | 1.10% |

| 2030 | 10,563,255 | 1.10% |

| 2031 | 10,647,761 | 0.80% |

| 2032 | 10,732,943 | 0.80% |

| 2033 | 10,818,807 | 0.80% |

| 2034 | 10,905,357 | 0.80% |

| 2035 | 10,992,600 | 0.80% |

| 2036 | 11,025,578 | 0.30% |

| 2037 | 11,058,655 | 0.30% |

| 2038 | 11,091,831 | 0.30% |

| 2039 | 11,125,106 | 0.30% |

| 2040 | 11,158,481 | 0.30% |

| 2041 | 11,136,164 | −0.20% |

| 2042 | 11,113,892 | −0.20% |

| 2043 | 11,091,664 | −0.20% |

| 2044 | 11,069,481 | −0.20% |

| 2045 | 11,047,342 | −0.20% |

| 2046 | 10,981,058 | −0.60% |

| 2047 | 10,915,172 | −0.60% |

| 2048 | 10,849,681 | −0.60% |

| 2049 | 10,784,583 | −0.60% |

| 2050 | 10,719,876 | −0.60% |

Appendix A.2. GDP

| Year | GDP (Billion Yen) | Growth Rate |

|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 95,251.5 | |

| 2002 | 94,354.8 | |

| 2003 | 95,275.2 | |

| 2004 | 98,083.6 | |

| 2005 | 99,379.7 | |

| 2006 | 99,870.9 | |

| 2007 | 99,931.5 | |

| 2008 | 97,253.8 | |

| 2009 | 91,673.8 | |

| 2010 | 91,374.8 | |

| 2011 | 92,857.3 | |

| 2012 | 91,908.9 | |

| 2013 | 106,212.4 | |

| 2014 | 106,502.9 | |

| 2015 | 110,018.9 | |

| 2016 | 111,213.4 | |

| 2017 | 113,409.8 | |

| 2018 | 114,983.9 | |

| 2019 | 115,063.3 | |

| 2020 | 109,601.6 | |

| 2021 | 113,685.9 | |

| 2022 | 114,368.0 | 0.60% |

| 2023 | 115,054.2 | 0.60% |

| 2024 | 115,744.5 | 0.60% |

| 2025 | 116,439.0 | 0.60% |

| 2026 | 117,137.6 | 0.60% |

| 2027 | 117,840.4 | 0.60% |

| 2028 | 118,547.4 | 0.60% |

| 2029 | 119,258.7 | 0.60% |

| 2030 | 119,974.3 | 0.60% |

| 2031 | 120,694.1 | 0.60% |

| 2032 | 121,418.3 | 0.60% |

| 2033 | 122,146.8 | 0.60% |

| 2034 | 122,879.7 | 0.60% |

| 2035 | 123,617.0 | 0.60% |

| 2036 | 124,358.7 | 0.60% |

| 2037 | 125,104.9 | 0.60% |

| 2038 | 125,855.5 | 0.60% |

| 2039 | 126,610.6 | 0.60% |

| 2040 | 127,370.3 | 0.60% |

| 2041 | 127,994.4 | 0.49% |

| 2042 | 128,621.6 | 0.49% |

| 2043 | 129,251.8 | 0.49% |

| 2044 | 129,885.1 | 0.49% |

| 2045 | 130,521.5 | 0.49% |

| 2046 | 131,161.1 | 0.49% |

| 2047 | 131,803.8 | 0.49% |

| 2048 | 132,449.6 | 0.49% |

| 2049 | 133,098.6 | 0.49% |

| 2050 | 133,750.8 | 0.49% |

Appendix A.3. Road Length

| Year | Road Length (m) |

|---|---|

| 2001 | 11,732,964 |

| 2002 | 11,764,651 |

| 2003 | 11,779,907 |

| 2004 | 11,817,413 |

| 2005 | 11,831,701 |

| 2006 | 11,845,329 |

| 2007 | 11,862,644 |

| 2008 | 11,874,179 |

| 2009 | 11,883,031 |

| 2010 | 11,853,075 |

| 2011 | 11,841,112 |

| 2012 | 11,863,272 |

| 2013 | 11,870,062 |

| 2014 | 11,874,641 |

| 2015 | 11,891,476 |

| 2016 | 11,897,638 |

| 2017 | 11,934,266 |

| 2018 | 11,967,937 |

| 2019 | 11,976,665 |

| 2020 | 11,985,125 |

| 2021 | 11,998,427 |

| 2022 | 12,007,695 |

| 2023 | 12,015,386 |

| 2024 | 12,021,768 |

| 2025 | 12,027,065 |

| 2026 | 12,031,460 |

| 2027 | 12,035,108 |

| 2028 | 12,038,135 |

| 2029 | 12,040,647 |

| 2030 | 12,042,732 |

| 2031 | 12,044,462 |

| 2032 | 12,045,898 |

| 2033 | 12,047,090 |

| 2034 | 12,048,078 |

| 2035 | 12,048,899 |

| 2036 | 12,049,580 |

| 2037 | 12,050,145 |

| 2038 | 12,050,614 |

| 2039 | 12,051,003 |

| 2040 | 12,051,326 |

| 2041 | 12,051,594 |

| 2042 | 12,051,817 |

| 2043 | 12,052,001 |

| 2044 | 12,052,154 |

| 2045 | 12,052,282 |

| 2046 | 12,052,387 |

| 2047 | 12,052,475 |

| 2048 | 12,052,547 |

| 2049 | 12,052,608 |

| 2050 | 12,052,658 |

Appendix A.4. Employment

| Year | Employment (1000 Person) |

|---|---|

| 2001 | 6330 |

| 2002 | 6385 |

| 2003 | 6379 |

| 2004 | 6453 |

| 2005 | 6557 |

| 2006 | 6832 |

| 2007 | 6885 |

| 2008 | 6781 |

| 2009 | 6728 |

| 2010 | 7117 |

| 2011 | 7062 |

| 2012 | 7070 |

| 2013 | 7163 |

| 2014 | 7312 |

| 2015 | 7400 |

| 2016 | 7517 |

| 2017 | 7682 |

| 2018 | 7922 |

| 2019 | 8061 |

| 2020 | 8104 |

| 2021 | 8146 |

| 2022 | 8240 |

| 2023 | 8334 |

| 2024 | 8428 |

| 2025 | 8521 |

| 2026 | 8615 |

| 2027 | 8709 |

| 2028 | 8803 |

| 2029 | 8897 |

| 2030 | 8991 |

| 2031 | 9085 |

| 2032 | 9178 |

| 2033 | 9272 |

| 2034 | 9366 |

| 2035 | 9460 |

| 2036 | 9554 |

| 2037 | 9648 |

| 2038 | 9742 |

| 2039 | 9835 |

| 2040 | 9929 |

| 2041 | 10,023 |

| 2042 | 10,117 |

| 2043 | 10,211 |

| 2044 | 10,305 |

| 2045 | 10,399 |

| 2046 | 10,492 |

| 2047 | 10,586 |

| 2048 | 10,680 |

| 2049 | 10,774 |

| 2050 | 10,868 |

Appendix A.5. Ordinary Truck Stock

| Year | Ordinary Truck Stock (Vehicle) |

|---|---|

| 2001 | 116,882 |

| 2002 | 113,666 |

| 2003 | 107,599 |

| 2004 | 105,828 |

| 2005 | 102,312 |

| 2006 | 98,832 |

| 2007 | 97,732 |

| 2008 | 95,077 |

| 2009 | 92,451 |

| 2010 | 90,948 |

| 2011 | 89,743 |

| 2012 | 89,456 |

| 2013 | 89,413 |

| 2014 | 89,627 |

| 2015 | 89,496 |

| 2016 | 89,090 |

| 2017 | 88,615 |

| 2018 | 88,634 |

| 2019 | 88,505 |

| 2020 | 87,625 |

| 2021 | 86,882 |

| 2022 | 86,075 |

| 2023 | 84,869 |

| 2024 | 83,981 |

| 2025 | 82,924 |

| 2026 | 81,703 |

| 2027 | 80,776 |

| 2028 | 79,604 |

| 2029 | 78,447 |

| 2030 | 77,477 |

| 2031 | 76,258 |

| 2032 | 75,169 |

| 2033 | 74,141 |

| 2034 | 72,921 |

| 2035 | 71,878 |

| 2036 | 70,790 |

| 2037 | 69,600 |

| 2038 | 68,573 |

| 2039 | 67,439 |

| 2040 | 66,289 |

| 2041 | 65,254 |

| 2042 | 64,094 |

| 2043 | 62,983 |

| 2044 | 61,923 |

| 2045 | 60,758 |

| 2046 | 59,675 |

| 2047 | 58,586 |

| 2048 | 57,431 |

| 2049 | 56,362 |

| 2050 | 55,247 |

Appendix A.6. Minivan Stock

| Year | Minivan Stock (Vehicle) |

|---|---|

| 2001 | 287,104 |

| 2002 | 273,301 |

| 2003 | 257,137 |

| 2004 | 248,956 |

| 2005 | 240,924 |

| 2006 | 232,741 |

| 2007 | 227,375 |

| 2008 | 216,140 |

| 2009 | 207,763 |

| 2010 | 201,080 |

| 2011 | 196,572 |

| 2012 | 192,015 |

| 2013 | 188,633 |

| 2014 | 186,394 |

| 2015 | 183,962 |

| 2016 | 182,005 |

| 2017 | 179,989 |

| 2018 | 178,136 |

| 2019 | 176,335 |

| 2020 | 173,030 |

| 2021 | 171,255 |

| 2022 | 169,480 |

| 2023 | 167,705 |

| 2024 | 165,930 |

| 2025 | 164,155 |

| 2026 | 162,380 |

| 2027 | 160,605 |

| 2028 | 158,830 |

| 2029 | 157,055 |

| 2030 | 155,280 |

| 2031 | 153,505 |

| 2032 | 151,730 |

| 2033 | 149,955 |

| 2034 | 148,180 |

| 2035 | 146,405 |

| 2036 | 144,630 |

| 2037 | 142,855 |

| 2038 | 141,080 |

| 2039 | 139,305 |

| 2040 | 137,530 |

| 2041 | 135,755 |

| 2042 | 133,980 |

| 2043 | 132,205 |

| 2044 | 130,430 |

| 2045 | 128,655 |

| 2046 | 126,880 |

| 2047 | 125,105 |

| 2048 | 123,330 |

| 2049 | 121,555 |

| 2050 | 119,780 |

Appendix A.7. Auto-ARIMA Model Detection Results

| Variables | Training Set/Test Set Partitioning | Test RMSE | Test MAE | Test MAPE | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Road length | Train: 2013–2019; Test: 2020–2021 | 3319.21 | 2939.13 | 0.0245% | The error percentage is extremely small, and the extrapolation is more like a “smooth continuation of the trend”. |

| Employment | Train: 2000–2017; Test: 2018–2021 | 158.05 | 154.63 | 1.92% | A typical “random walk + drift” pattern is available for short-term fitting. |

| Ordinary truck stock | Train: 2001–2018; Test: 2019–2021 | 1112.11 | / | 0.54% | The error percentage is low; however, d = 2 will make long-term forecasts more “linear/quadratic trending”. |

| Minivan stock | Train: 2001–2018; Test: 2019–2021 | 748.57 | 638.41 | 0.73% | The accuracy is good; residual diagnosis requires combining different lag interpretations. |

| Variables | Original Sequence ADF p-Value | Original Sequence KPSS p-Value | Actual Model Difference d | Key Results | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Road length | 0.044 | 0.07409 | 1 | ADF p = 0.830; KPSS (Level) p = 0.10 | The short sample size results in limited power of the test; using d = 1 is a safe approach. |

| Employment | 0.345 | 0.013182 | 1 | ADF p = 0.023; KPSS p = 0.10 | The last two tests after the difference consistently point to “closer to stationary”. |

| Ordinary truck stock | 0.99 | 0.01436 | 2 | KPSS p = 0.10; PP p = 0.010; ADF p = 0.462 | KPSS/PP supports stationarity, but ADF is not significant (common in small samples). |

| Minivan stock | 0.623 | 0.0154577 | 2 | KPSS p = 0.10; ADF p = 0.520 | KPSS strongly suggests differential processing is required; KPSS passes after differential processing. |

| Variables | Ljung–Box p (Check Residuals) | Manual Ljung–Box | The Final Model for the Full Sample is Ljung–Box p (Check Residuals) | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Road length | 0.468 | lag = 3 (fitdf = 2) p = 0.141 | 0.723 | The residuals can be regarded as white noise, and the model setting is clean in terms of statistical diagnosis. |

| Employment | 0.0546 | lag = 10 p = 0.3568 | 0.0657 | The residual autocorrelation is “significant at the boundary,” but becomes insignificant after changing to a longer lag. |

| Ordinary truck stock | 0.1195 | lag = 10 p = 0.4517 | 0.1062 | The residuals passed the white noise test; the diagnostic results were stable. |

| Minivan stock | 0.0245 | lag = 8 (fitdf = 1) p = 0.1305 | 0.3858 | The default test on the training set indicated autocorrelation, but it was not significant after customizing the lag; the residuals of the full-sample model passed. |

Appendix B. Transportation Turnover

Appendix B.1. Railway

| Year | Passenger Turnover (1000 Person-km) | GDP (Billion Yen) |

|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 83,304,143 | 106,212.4 |

| 2014 | 83,045,682 | 106,502.9 |

| 2015 | 85,030,432 | 110,018.9 |

| 2016 | 85,990,616 | 111,213.4 |

| 2017 | 87,257,665 | 113,409.8 |

| 2018 | 88,314,835 | 114,983.9 |

| 2019 | 87,819,136 | 115,063.3 |

| 2020 | 58,518,423 | 109,601.6 |

| 2021 | 68,739,549 | 113,685.9 |

| Turnover = 2.045 × 107 + 647.3 × GDP | ||

| 2022 | 94,480,406 | 114,368.0 |

| 2023 | 94,924,584 | 115,054.2 |

| 2024 | 95,371,415 | 115,744.5 |

| 2025 | 95,820,965 | 116,439.0 |

| 2026 | 96,273,168 | 117,137.6 |

| 2027 | 96,728,091 | 117,840.4 |

| 2028 | 97,185,732 | 118,547.4 |

| 2029 | 97,646,157 | 119,258.7 |

| 2030 | 98,109,364 | 119,974.3 |

| 2031 | 98,575,291 | 120,694.1 |

| 2032 | 99,044,066 | 121,418.3 |

| 2033 | 99,515,624 | 122,146.8 |

| 2034 | 99,990,030 | 122,879.7 |

| 2035 | 100,467,284 | 123,617.0 |

| 2036 | 100,947,387 | 124,358.7 |

| 2037 | 101,430,402 | 125,104.9 |

| 2038 | 101,916,265 | 125,855.5 |

| 2039 | 102,405,041 | 126,610.6 |

| 2040 | 102,896,795 | 127,370.3 |

| 2041 | 103,300,775 | 127,994.4 |

| 2042 | 103,706,762 | 128,621.6 |

| 2043 | 104,114,690 | 129,251.8 |

| 2044 | 104,524,625 | 129,885.1 |

| 2045 | 104,936,567 | 130,521.5 |

| 2046 | 105,350,580 | 131,161.1 |

| 2047 | 105,766,600 | 131,803.8 |

| 2048 | 106,184,626 | 132,449.6 |

| 2049 | 106,604,724 | 133,098.6 |

| 2050 | 107,026,893 | 133,750.8 |

Appendix B.2. Bus

| Year | Passenger Turnover (1000 Person-km) | GDP (Billion Yen) | Road Length (m) | Employment (1000 Person) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 6,562,722 | 95,251.5 | 11,732,964 | 6330 |

| 2002 | 6,876,038 | 94,354.8 | 11,764,651 | 6385 |

| 2003 | 6,970,146 | 95,275.2 | 11,779,907 | 6379 |

| 2004 | 6,686,382 | 98,083.6 | 11,817,413 | 6453 |

| 2005 | 6,605,573 | 99,379.7 | 11,831,701 | 6557 |

| 2006 | 6,751,827 | 99,870.9 | 11,845,329 | 6832 |

| 2007 | 6,547,959 | 99,931.5 | 11,862,644 | 6885 |

| 2008 | 6,200,817 | 97,253.8 | 11,874,179 | 6781 |

| 2009 | 6,199,802 | 91,673.8 | 11,883,031 | 6728 |

| 2010 | 6,621,299 | 91,374.8 | 11,853,075 | 7117 |

| 2011 | 6,733,028 | 92,857.3 | 11,841,112 | 7062 |

| 2012 | 7,380,847 | 91,908.9 | 11,863,272 | 7070 |

| 2013 | 7,708,862 | 106,212.4 | 11,870,062 | 7163 |

| 2014 | 7,472,885 | 106,502.9 | 11,874,641 | 7312 |

| 2015 | 8,171,069 | 110,018.9 | 11,891,476 | 7400 |

| 2016 | 8,739,225 | 111,213.4 | 11,897,638 | 7517 |

| 2017 | 9,490,794 | 113,409.8 | 11,934,266 | 7682 |

| 2018 | 9,193,662 | 114,983.9 | 11,967,937 | 7922 |

| 2019 | 8,936,956 | 115,063.3 | 11,976,665 | 8061 |

| 2020 | 2,998,425 | 109,601.6 | 11,985,125 | 8104 |

| 2021 | 3,737,046 | 113,685.9 | 11,998,427 | 8146 |

| Turnover = 73,070,000 + 70.54 × GDP − 7.069 × Road_length + 1562 × Employment | ||||

| 2022 | 9,126,003 | 114,368.0 | 12,007,695 | 8240 |

| 2023 | 9,266,868 | 115,054.2 | 12,015,386 | 8334 |

| 2024 | 9,417,275 | 115,744.5 | 12,021,768 | 8428 |

| 2025 | 9,574,087 | 116,439.0 | 12,027,065 | 8521 |

| 2026 | 9,739,126 | 117,137.6 | 12,031,460 | 8615 |

| 2027 | 9,909,741 | 117,840.4 | 12,035,108 | 8709 |

| 2028 | 10,085,043 | 118,547.4 | 12,038,135 | 8803 |

| 2029 | 10,264,289 | 119,258.7 | 12,040,647 | 8897 |

| 2030 | 10,446,857 | 119,974.3 | 12,042,732 | 8991 |

| 2031 | 10,632,230 | 120,694.1 | 12,044,462 | 9085 |

| 2032 | 10,818,430 | 121,418.3 | 12,045,898 | 9178 |

| 2033 | 11,008,220 | 122,146.8 | 12,047,090 | 9272 |

| 2034 | 11,199,763 | 122,879.7 | 12,048,078 | 9366 |

| 2035 | 11,392,796 | 123,617.0 | 12,048,899 | 9460 |

| 2036 | 11,587,130 | 124,358.7 | 12,049,580 | 9554 |

| 2037 | 11,782,601 | 125,104.9 | 12,050,145 | 9648 |

| 2038 | 11,979,061 | 125,855.5 | 12,050,614 | 9742 |

| 2039 | 12,174,842 | 126,610.6 | 12,051,003 | 9835 |

| 2040 | 12,372,975 | 127,370.3 | 12,051,326 | 9929 |

| 2041 | 12,561,933 | 127,994.4 | 12,051,594 | 10,023 |

| 2042 | 12,751,427 | 128,621.6 | 12,051,817 | 10,117 |

| 2043 | 12,941,409 | 129,251.8 | 12,052,001 | 10,211 |

| 2044 | 13,131,828 | 129,885.1 | 12,052,154 | 10,305 |

| 2045 | 13,322,643 | 130,521.5 | 12,052,282 | 10,399 |

| 2046 | 13,512,284 | 131,161.1 | 12,052,387 | 10,492 |

| 2047 | 13,703,826 | 131,803.8 | 12,052,475 | 10,586 |

| 2048 | 13,895,700 | 132,449.6 | 12,052,547 | 10,680 |

| 2049 | 14,087,877 | 133,098.6 | 12,052,608 | 10,774 |

| 2050 | 14,280,358 | 133,750.8 | 12,052,658 | 10,868 |

Appendix B.3. Taxi

| Year | Passenger Turnover (1000 Person-km) | GDP (Billion Yen) | Population (Person) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 2,501,799 | 95,251.5 | 7,967,602 |

| 2002 | 2,512,254 | 94,354.8 | 8,023,202 |

| 2003 | 2,571,931 | 95,275.2 | 8,081,959 |

| 2004 | 2,429,262 | 98,083.6 | 8,129,801 |

| 2005 | 2,493,216 | 99,379.7 | 8,183,907 |

| 2006 | 2,501,707 | 99,870.9 | 8,247,810 |

| 2007 | 2,423,085 | 99,931.5 | 8,318,841 |

| 2008 | 2,379,616 | 97,253.8 | 8,387,659 |

| 2009 | 2,277,617 | 91,673.8 | 8,451,067 |

| 2010 | 2,032,325 | 91,374.8 | 8,502,527 |

| 2011 | 1,752,631 | 92,857.3 | 8,541,979 |

| 2012 | 1,598,157 | 91,908.9 | 8,575,228 |

| 2013 | 1,596,038 | 106,212.4 | 8,951,575 |

| 2014 | 1,518,477 | 106,502.9 | 9,016,342 |

| 2015 | 1,473,754 | 110,018.9 | 9,102,598 |

| 2016 | 1,457,567 | 111,213.4 | 9,205,712 |

| 2017 | 1,438,910 | 113,409.8 | 9,302,962 |

| 2018 | 1,425,221 | 114,983.9 | 9,396,595 |

| 2019 | 1,267,885 | 115,063.3 | 9,486,618 |

| 2020 | 667,959 | 109,601.6 | 9,570,609 |

| 2021 | 764,770 | 113,685.9 | 9,572,763 |

| Turnover = exp(19.99 − 8.072 × 10−7 × Population + 1.398 × 10−5 × GDP) | |||

| 2022 | 961,198 | 114,368.0 | 9,678,063 |

| 2023 | 890,549 | 115,054.2 | 9,784,522 |

| 2024 | 824,361 | 115,744.5 | 9,892,152 |

| 2025 | 762,408 | 116,439.0 | 10,000,966 |

| 2026 | 704,470 | 117,137.6 | 10,110,977 |

| 2027 | 650,338 | 117,840.4 | 10,222,198 |

| 2028 | 599,808 | 118,547.4 | 10,334,642 |

| 2029 | 552,686 | 119,258.7 | 10,448,323 |

| 2030 | 508,782 | 119,974.3 | 10,563,255 |

| 2031 | 480,039 | 120,694.1 | 10,647,761 |

| 2032 | 452,701 | 121,418.3 | 10,732,943 |

| 2033 | 426,710 | 122,146.8 | 10,818,807 |

| 2034 | 402,013 | 122,879.7 | 10,905,357 |

| 2035 | 378,558 | 123,617.0 | 10,992,600 |

| 2036 | 372,455 | 124,358.7 | 11,025,578 |

| 2037 | 366,444 | 125,104.9 | 11,058,655 |

| 2038 | 360,523 | 125,855.5 | 11,091,831 |

| 2039 | 354,692 | 126,610.6 | 11,125,106 |

| 2040 | 348,950 | 127,370.3 | 11,158,481 |

| 2041 | 358,405 | 127,994.4 | 11,136,164 |

| 2042 | 368,119 | 128,621.6 | 11,113,892 |

| 2043 | 378,099 | 129,251.8 | 11,091,664 |

| 2044 | 388,352 | 129,885.1 | 11,069,481 |

| 2045 | 398,887 | 130,521.5 | 11,047,342 |

| 2046 | 424,588 | 131,161.1 | 10,981,058 |

| 2047 | 451,820 | 131,803.8 | 10,915,172 |

| 2048 | 480,666 | 132,449.6 | 10,849,681 |

| 2049 | 511,215 | 133,098.6 | 10,784,583 |

| 2050 | 543,557 | 133,750.8 | 10,719,876 |

Appendix B.4. Ordinary Truck

| Year | Freight Turnover (1000 Tons-km) | Stock (Vehicle) |

|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 6,171,446 | 118,740 |

| 2002 | 5,844,815 | 116,882 |

| 2003 | 5,682,172 | 113,666 |

| 2004 | 5,710,084 | 107,599 |

| 2005 | 5,499,298 | 105,828 |

| 2006 | 5,776,746 | 102,312 |

| 2007 | 5,377,405 | 98,832 |

| 2008 | 5,099,318 | 97,732 |

| 2009 | 4,989,595 | 95,077 |

| 2010 | 3,844,672 | 92,451 |

| 2011 | 5,377,923 | 90,948 |

| 2012 | 4,832,928 | 89,743 |

| 2013 | 3,750,563 | 89,456 |

| 2014 | 4,042,682 | 89,627 |

| 2015 | 3,887,436 | 89,496 |

| 2016 | 3,754,995 | 89,090 |

| 2017 | 3,699,343 | 88,615 |

| 2018 | 3,759,156 | 88,634 |

| 2019 | 3,800,921 | 88,505 |

| 2020 | 3,702,722 | 87,625 |

| 2021 | 3,479,665 | 86,882 |

| Turnover = −3,605,000 + 86.96 × Stock | ||

| 2022 | 3,880,082 | 86,075 |

| 2023 | 3,775,208 | 84,869 |

| 2024 | 3,697,988 | 83,981 |

| 2025 | 3,606,071 | 82,924 |

| 2026 | 3,499,893 | 81,703 |

| 2027 | 3,419,281 | 80,776 |

| 2028 | 3,317,364 | 79,604 |

| 2029 | 3,216,751 | 78,447 |

| 2030 | 3,132,400 | 77,477 |

| 2031 | 3,026,396 | 76,258 |

| 2032 | 2,931,696 | 75,169 |

| 2033 | 2,842,301 | 74,141 |

| 2034 | 2,736,210 | 72,921 |

| 2035 | 2,645,511 | 71,878 |

| 2036 | 2,550,898 | 70,790 |

| 2037 | 2,447,416 | 69,600 |

| 2038 | 2,358,108 | 68,573 |

| 2039 | 2,259,495 | 67,439 |

| 2040 | 2,159,491 | 66,289 |

| 2041 | 2,069,488 | 65,254 |

| 2042 | 1,968,614 | 64,094 |

| 2043 | 1,872,002 | 62,983 |

| 2044 | 1,779,824 | 61,923 |

| 2045 | 1,678,516 | 60,758 |

| 2046 | 1,584,338 | 59,675 |

| 2047 | 1,489,639 | 58,586 |

| 2048 | 1,389,200 | 57,431 |

| 2049 | 1,296,240 | 56,362 |

| 2050 | 1,199,279 | 55,247 |

Appendix B.5. Minivan

| Year | Freight Turnover (1000 Tons-km) | Stock (Vehicle) |

|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 237,080 | 287,104 |

| 2002 | 227,558 | 273,301 |

| 2003 | 210,318 | 257,137 |

| 2004 | 202,979 | 248,956 |

| 2005 | 204,458 | 240,924 |

| 2006 | 201,065 | 232,741 |

| 2007 | 198,707 | 227,375 |

| 2008 | 185,718 | 216,140 |

| 2009 | 182,575 | 207,763 |

| 2010 | 116,912 | 201,080 |

| 2011 | 120,043 | 196,572 |

| 2012 | 148,650 | 192,015 |

| 2013 | 137,925 | 188,633 |

| 2014 | 115,825 | 186,394 |

| 2015 | 117,326 | 183,962 |

| 2016 | 102,702 | 182,005 |

| 2017 | 103,820 | 179,989 |

| 2018 | 103,823 | 178,136 |

| 2019 | 104,482 | 176,335 |

| 2020 | 84,454 | 173,030 |

| 2021 | 83,765 | 171,255 |

| Turnover = −136,800 + 1.378 × Stock | ||

| 2022 | 99,189 | 169,480 |

| 2023 | 96,743 | 167,705 |

| 2024 | 94,297 | 165,930 |

| 2025 | 91,852 | 164,155 |

| 2026 | 89,406 | 162,380 |

| 2027 | 86,960 | 160,605 |

| 2028 | 84,514 | 158,830 |

| 2029 | 82,068 | 157,055 |

| 2030 | 79,622 | 155,280 |

| 2031 | 77,176 | 153,505 |

| 2032 | 74,730 | 151,730 |

| 2033 | 72,284 | 149,955 |

| 2034 | 69,838 | 148,180 |

| 2035 | 67,392 | 146,405 |

| 2036 | 64,946 | 144,630 |

| 2037 | 62,500 | 142,855 |

| 2038 | 60,054 | 141,080 |

| 2039 | 57,608 | 139,305 |

| 2040 | 55,162 | 137,530 |

| 2041 | 52,716 | 135,755 |

| 2042 | 50,270 | 133,980 |

| 2043 | 47,824 | 132,205 |

| 2044 | 45,378 | 130,430 |

| 2045 | 42,933 | 128,655 |

| 2046 | 40,487 | 126,880 |

| 2047 | 38,041 | 125,105 |

| 2048 | 35,595 | 123,330 |

| 2049 | 33,149 | 121,555 |

| 2050 | 30,703 | 119,780 |

Appendix C. Energy Intensity

Appendix C.1. Railway

Appendix C.2. Bus

Appendix C.3. Taxi

| Type | Energy Consumption (L/km, m3/km, kWh/km) | Energy Intensity (L/Person-km, m3/Person-km, kWh/Person-km) | Turnover (1000 Person-km) | Average Energy Intensity of Fossil Fuels (L/Person-km) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LPG | 0.1020 | 0.07849 | 399,387 | 0.0631 |

| LPG-HV | 0.0595 | 0.04579 | 296,730 | |

| HV | 0.0630 | 0.04846 | 61,354 | |

| PHV | 0.0316 | 0.02434 | 0 | |

| Diesel | 0.0640 | 0.04923 | 185 | |

| Gasoline | 0.0746 | 0.05741 | 6992 | |

| Hydrogen | 0.0002 | 0.00017 | 0 | 6885 |

| EV | 0.1500 | 0.11538 | 123 | 6781 |

Appendix C.4. Ordinary Truck

| Average Daily Load Capacity (ton/day) | Average Number of Trips Per Day (trip/day) | Average Load Per Vehicle (ton/trip) |

|---|---|---|

| 10.34 | 2.47 | 4.19 |

| Energy Consumption (km/kg) | Energy Consumption (kg/km) | Energy Intensity (m3/ton-km) |

|---|---|---|

| 148 | 0.0067568 | 0.0000403 |

| Battery Capacity (kWh) | Theoretical Driving Range (km) | Energy Consumption (kWh/km) | Energy Intensity (kWh/ton-km) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 83 | 100 | 0.83 | 0.1981 |

Appendix C.5. Minivan

| Average Daily Load Capacity (ton/day) | Average Number of Trips Per Day (trip/day) | Average Load Per Vehicle (ton/trip) |

|---|---|---|

| 2.17 | 2.61 | 0.83 |

| hydrogen Volume (m3) | Theoretical Driving Range (km) | Energy Consumption (m3/km) | Energy Intensity (m3/ton-km) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0.157 | 200 | 0.000765 | 0.00092 |

| Energy Consumption (km/L) | Energy Consumption (L/km) | Energy Intensity (L/ton-km) |

|---|---|---|

| 17.9 | 0.055866 | 0.06719 |

Appendix D. Scenario Design

Appendix D.1. Energy Structure Optimization

| Type | Service Life (Year) |

|---|---|

| Bus | 5 |

| Taxi | 4 |

| Ordinary truck | 4 |

| Minivan | 3 |

| Year | Vehicle Type | Indicators/Targets | Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2030 | Truck | The proportion of electrified vehicles (including EVs/PHVs) in new car sales reaches 20–30%. | https://www.mlit.go.jp/page/content/001580237.pdf (accessed on 4 December 2025) |

| 2030 | Truck | A total of 5000 fuel cell/electric commercial vehicles have been introduced. | |

| 2030 | Truck | The target for non-fossil fuel vehicles is 5%. | https://www.meti.go.jp/shingikai/sankoshin/green_innovation/industrial_restructuring/pdf/030_03_00.pdf (accessed on 4 December 2025) |

| 2030 | Bus | The target for non-fossil fuel vehicles is 5%. | |

| 2030 | Taxi | The target for non-fossil fuel vehicles is 8%. | |

| 2040 | Minivan | 100% of new cars are electric vehicles or use decarbonized fuels | |

| 2030 | FCV Minivan | The target number of units introduced is approximately 3600. | https://www.metro.tokyo.lg.jp/information/press/2025/04/2025041804# (accessed on 4 December 2025) |

| 2030 | FCV Truck | The target number of units introduced is approximately 500. | |

| 2030 | FCV Bus | The target number of units introduced is approximately 300. | |

| 2030 | FCV Taxi | The target number of units introduced is approximately 600. | |

| 2035 | FCV commercial vehicle | The target is at least 300 units (EV or FCV). | |

| 2030 | ZEV Bus | The target number of units introduced is approximately 300. | https://www.kankyo.metro.tokyo.lg.jp/documents/d/kankyo/zeroemission_tokyo-strategy-files-zero_emission_tokyo_strategy (accessed on 4 December 2025) |

| 2050 | All vehicles | 100% Zero Emissions (All ZEVs, such as EVs/FCVs) |

Appendix D.2. Emission Factor Optimization (For Hydrogen and Electricity)

| Year | Emission Factor (kgCO2/kgH2) | Emission Factor (kgCO2/m3H2) |

|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 3.4 | 136.62 |

| 2030 | 1.5 | 60.27 |

| 2040 | 0.6 | 24.11 |

| 2050 | 0 | 0 |

| Year | Emission Factor (kgCO2/kWh) | Data Sources |

|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 0.436 | https://e-lcs.jp/news/.assets/2021%E5%B9%B4%E5%BA%A6-CO2%E6%8E%92%E5%87%BA%E5%AE%9F%E7%B8%BE%EF%BC%88%E7%A2%BA%E5%A0%B1%E5%80%A4%EF%BC%89.pdf (accessed on 4 December 2025) |

| 2030 | 0.37 | https://www.meti.go.jp/shingikai/enecho/denryoku_gas/denryoku_gas/sekitan_karyoku_wg/pdf/002_04_00.pdf (accessed on 4 December 2025) |

| 2050 | 0 | https://www.enecho.meti.go.jp/category/others/basic_plan/pdf/20250218_01.pdf (accessed on 4 December 2025) |

Appendix D.3. Energy Intensity Optimization (For Traditional Fossil Energy)

| Type | Average Annual Decline Rate |

|---|---|

| Taxi | 3.60% |

| Bus | 0.49% |

| Ordinary truck | 1.35% |

| Minivan | 2.96% |

Appendix E. Univariate Sensitivity Analysis

Appendix E.1. Purpose and Setting

- (1)

- Perturbation Targets: Electricity and Hydrogen Production Emission Factors

- (2)

- Perturbation Range: ±20% (2022–2049), fixed at 0 in 2050

- (3)

- Indicators: E2040 and CumE_2022–2050.

Appendix E.2. Case Selection

Appendix E.3. Analysis Results

| Scenarios | E_2040 Base (kt) | E_2040 Low (kt) | E_2040 High (kt) | Range (kt) | Range (%) | CumE_2022-2050 Base (kt) | CumE_2022-2050 Low (kt) | CumE_2022-2050 High (kt) | Range (kt) | Range (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | 1994.95 | 2024.30 | 1972.69 | 51.61 | 2.59 | 68,535.29 | 69,361.95 | 67,908.40 | 1453.54 | 2.12 |

| A3B | 1751.15 | 1783.09 | 1726.61 | 56.48 | 3.23 | 63,531.73 | 64,410.75 | 62,857.62 | 1553.13 | 2.44 |

| A3BC | 1586.42 | 1618.36 | 1561.87 | 56.48 | 3.56 | 59,694.50 | 60,573.51 | 59,020.38 | 1553.13 | 2.60 |

References

- Hulkkonen, M.; Mielonen, T.; Prisle, N.L. The atmospheric impacts of initiatives advancing shifts towards low-emission mobility: A scoping review. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 713, 136133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Sixth Assessment Report. 2022. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/assessment-report/ar6/ (accessed on 8 April 2022).

- A National Institute for Environmental Studies (NIES); Ministry of the Environment, Japan (MOEJ). National GHG Inventory Document of Japan (April 2025); NIES: Tsukuba, Japan; MOEJ: Tokyo, Japan, 2025; Available online: https://www.nies.go.jp/gio/en/aboutghg/index.html (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism (MLIT). Logistics Census; MLIT: Tokyo, Japan, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kawasaki, T.; Loh, Z.T.; Sugimura, Y.; Hanaoka, S. Geospatial extent of CO2 emission of transportation and the impact of decarbonization policy in Japan. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 496, 145117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathiesen, B.V.; Lund, H.; Connolly, D.; Wenzel, H.; Østergaard, P.A.; Möller, B.; Nielsen, S.; Ridjan, I.; Karnøe, P.; Sperling, K.; et al. Smart Energy Systems for coherent 100% renewable energy and transport solutions. Appl. Energy 2015, 145, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Z.H.; Sun, S.J.; Wang, Y.S.; Ni, J.R.; Qian, X.P. Impact of New Energy Vehicle Development on China’s Crude Oil Imports: An Empirical Analysis. World Electr. Veh. J. 2023, 14, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hainsch, K.; Löffler, K.; Burandt, T.; Auer, H.; Crespo del Granado, P.; Pisciella, P.; Zwickl-Bernhard, S. Energy transition scenarios: What policies, societal attitudes, and technology developments will realize the EU Green Deal? Energy 2022, 239, 122067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzwigol, H.; Kwilinski, A.; Lyulyov, O.; Pimonenko, T. The role of environmental regulations, renewable energy, and energy efficiency in finding the path to green economic growth. Energies 2023, 16, 3090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokyo Metropolitan Government, Bureau of Environment. Zero Emission Tokyo Strategy; Tokyo Metropolitan Government: Tokyo, Japan, 2019. Available online: https://www.kankyo.metro.tokyo.lg.jp/en/about_us/zero_emission_tokyo/strategy.html (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Meng, L.H.; Li, M.; Asuka, J. A scenario analysis of the energy transition in Japan’s road transportation sector based on the LEAP model. Environ. Res. Lett. 2024, 19, 044059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeuchi, K.; Nugroho, S.B.; Kawazu, E. Mobility and energy policies to achieve net zero emissions as key opportunities to build a prosperous society. IATSS Rev. 2022, 47, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barhoumi, E.M.; Okonkwo, P.C.; Farhani, S.; Belgacem, I.B.; Zghaibeh, M.; Mansir, I.B.; Bacha, F. Techno-economic analysis of photovoltaic-hydrogen refueling station case study: A transport company Tunis-Tunisia. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2022, 47, 24523–24532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockholm Environment Institute. LEAP: Introduction. 2023. Available online: https://leap.sei.org/default.asp?action=introduction (accessed on 25 June 2025).

- Li, L.; Sun, S.; Zhong, L.; Han, J.; Qian, X. Novel spatiotemporal nonlinear regression approach for unveiling the impact of urban spatial morphology on carbon emissions. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 125, 106381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Guo, Z.; Li, L.; Zheng, Z.; Wang, J.; Anno, S.; Qian, X. Decoding public sentiments on energy transition in Japan’s three major metropolitan areas: Social media analysis using machine learning. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 495, 145038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UN DESA). Goal 11: Make Cities and Human Settlements Inclusive, Safe, Resilient and Sustainable; UN DESA: New York, NY, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford, J.; Coutard, O. Urban energy transitions: Places, processes and politics of socio-technical change. Urban Stud. 2014, 51, 1353–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geels, F.W. A socio-technical analysis of low-carbon transitions: Introducing the multi-level perspective into transport studies. J. Transp. Geogr. 2012, 24, 471–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ). Sustainable Urban Transport: Avoid–Shift–Improve (A-S-I); GIZ: Eschborn, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Bongardt, D.; Breithaupt, M.; Creutzig, F. Beyond the Fossil City: Towards Low-Carbon Transport and Green Growth. In Sustainable Urban Transport Technical Document No. 6; Deutsche Gesellschaft für Technische Zusammenarbeit (GTZ): Eschborn, Germany, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Tokyo Metropolitan Government. Tokyo Statistical Yearbook (Annual Issues 2000–2021); Bureau of General Affairs, Statistics Division: Tokyo, Japan. Available online: https://www.toukei.metro.tokyo.lg.jp/tnenkan/tn-index.htm (accessed on 4 January 2026).

- National Institute of Population and Social Security Research. Future Population Projections by Municipality: Table 2. Total Population by Municipality [Excel File]. 2024. Available online: https://www.ipss.go.jp/pp-shicyoson/j/shicyoson23/2gaiyo_hyo/hyo2.xlsx (accessed on 4 January 2026).

- 77 Research and Consulting Co., Ltd. Tokyo’s Population Outlook and Economic Trends: Population Forecast and Implications for Regional Development [PDF Report]. 2023. Available online: https://www.77rc.co.jp/article_source/data/newsrelease/files/1f743913fdc6dd3c7ede72fcda8a23f4434b0f82.pdf (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Tokyo Metropolitan Government. New Target for Introduction of Fuel Cell Commercial Vehicles in Tokyo Has Been Set! Target for Introduction of Approximately 10,000 Fuel Cell Taxis by 2035 also Set [Press Release]. 18 April 2025. Available online: https://www.metro.tokyo.lg.jp/information/press/2025/04/2025041804.html (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- C40 Cities Climate Leadership Group; Tokyo Metropolitan Government. Zero Emission Tokyo Strategy [Case Study]. 2020. Available online: https://www.c40.org/case-studies/zero-emission-tokyo-strategy/ (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- InfluenceMap. Need for Vehicle Electrification–Japan: Electrified Vehicles Target by 2035 [Webpage]. 2023. Available online: https://japan.influencemap.org/policy/2035-vehicle-electrification-target-5357?lang=EN (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- National Tax Agency. Table of Useful Lives for Depreciable Assets [PDF]. n.d. Available online: https://www.nta.go.jp/taxes/shiraberu/taxanswer/shotoku/pdf/2100_01.pdf (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Ministry of the Environment; National Institute for Environmental Studies. Greenhouse Gas Emissions and Removals in Fiscal Year 2021 (Final Figures) [PDF]. 21 April 2023. Available online: https://www.env.go.jp/content/000168210.pdf (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Renewable Energy Institute. Revised Basic Hydrogen Strategy Offers No Clear Path to Carbon Neutrality [Position Paper]. 2023. Available online: https://www.renewable-ei.org/pdfdownload/activities/REI_Hydrogen_PositionPaper_2023_EN.pdf (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Renewable Energy Institute. Energy Mix to Support a Decarbonized Japan in 2050: Toward the Formulation of the Next Basic Energy Plan. 2021. Available online: https://www.enecho.meti.go.jp/committee/council/basic_policy_subcommittee/2021/044/044_006.pdf (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism (MLIT). Measures for Automotive Decarbonization by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism [Presentation]. 2024. Available online: https://www.ntsel.go.jp/Portals/0/resources/forum/2024files/NTSELForum2024_Inv01.pdf (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- IPCC. Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. In Working Group III Contribution to the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). Global EV Outlook 2024; IEA: Paris, France, 2024; Available online: https://iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2024 (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Bistline, J.E.T.; Young, D.T. The role of natural gas in reaching net-zero emissions in the electric sector. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Assessment of Technologies for Improving Light-Duty Vehicle Fuel Economy—2025–2035; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Reducing Fuel Consumption and Greenhouse Gas Emissions of Medium- and Heavy-Duty Vehicles, Phase Two: Final Report; The National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanguinetti, A.; Queen, E.; Yee, C.; Akanesuvan, K. Average impact and important features of onboard eco-driving feedback: A meta-analysis. Transp. Res. Part F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2020, 70, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meckling, J.; Sterner, T.; Wagner, G. Policy sequencing toward decarbonization. Nat. Energy 2017, 2, 918–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Packaging and Sequencing Policies for More Effective Climate Action; OECD Net Zero+ Policy Papers, No. 10; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency (IEA). The Future of Rail; IEA: Paris, France, 2019; Available online: https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/fb7dc9e4-d5ff-4a22-ac07-ef3ca73ac680/The_Future_of_Rail.pdf (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Unruh, G.C. Understanding carbon lock-in. Energy Policy 2000, 28, 817–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT). Total Cost of Ownership for Tractor-Trailers in Europe: Battery-Electric Versus Diesel; ICCT: Washington, DC, USA, 2021; Available online: https://theicct.org/publication/total-cost-of-ownership-for-tractor-trailers-in-europe-battery-electric-versus-diesel/ (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Avishan, F.; Yanıkoğlu, İ.; Alwesabi, Y. Electric bus fleet scheduling under travel time and energy consumption uncertainty. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2023, 156, 104357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Transport Forum (ITF/OECD). Towards Road Freight Decarbonisation; ITF: Paris, France, 2018; Available online: https://www.itf-oecd.org/towards-road-freight-decarbonisation (accessed on 4 December 2025).

- Tokyo Metropolitan Government (TMG). Final Energy Consumption and Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Tokyo; Tokyo Metropolitan Government: Tokyo, Japan, 2021.

- Tokyo Metropolitan Government (TMG). Outline of Zero Emission Tokyo Strategy; Tokyo Metropolitan Government: Tokyo, Japan, 2019. Available online: https://www.kankyo.metro.tokyo.lg.jp/documents/d/kankyo/outline-of-zero-emission-tokyo-strategy (accessed on 6 November 2025).

- Tokyo Metropolitan Government, Bureau of Industrial and Labor Affairs. Tokyo Metropolitan Government’s Efforts to Expand and Promote the Use of Hydrogen Energy: As of June 2025; Tokyo Metropolitan Government: Tokyo, Japan, 2025.

- OECD/International Transport Forum. Policy Priorities for Decarbonising Urban Passenger Transport; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ozawa, A.; Tsani, T.; Kudoh, Y. Japan’s pathways to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050—Scenario analysis using an energy modeling methodology. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 169, 112943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuda, K.; Ochi, Y.; Hasegawa, T.; Gomi, K. Quantification of the vision of net zero CO2 emissions in 2050 for Kyoto City. J. Jpn. Soc. Civ. Eng. Ser. G Environ. Res. 2021, 77, I_285–I_292. [Google Scholar]

- Hao, X.; Yan, C.; Narumi, D. Assessing CO2 reduction effects through decarbonization scenarios in the residential and transportation sectors: Challenges and solutions for Japan’s hilly and mountainous areas. Sustainability 2024, 16, 10342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type | Scenario Codes |

|---|---|

| Single-Factor | A1, A2, A3, B, C |

| Two-Factor | A1B, A2B, A3B, A1C, A2C, A3C |

| Multi-Factor | A1BC, A2BC, A3BC |

| Regression Model | Transportation Mode | Regression Equation | Accuracy Testing | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted R2 | R2 | p-Value | |||

| MLR | Railway | Turnover = 2.045 × 107 + 647.3 × GDP | 0.9890 | 0.9900 | |

| Bus | Turnover = 73,070,000 + 70.54 × GDP − 7.069 × Road_length + 1562 × Employment | 0.8466 | 0.8722 | ||

| Ordinary truck | Turnover = −3,605,000 + 86.96 × Stock | 0.7004 | 0.7154 | ||

| Minivan | Turnover = −136,800 + 1.378 × Stock | 0.8901 | 0.8956 | ||

| Accuracy Testing | |||||

| MAE | MAPE | RMSE | |||

| GLM | Taxi | Turnover = exp(19.99 − 8.072 × 10−7 × Population + 1.398 × 10−5 × GDP) | 168,618.01 | 10.99% | 205,007.77 |

| Modes | Maximum VIF | DW Value | Ljung–Box p-Value | ADF (p) | Conservative Inference Adjustment | Remark |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rail | 6.31 | 1.86 | 0.19 | 0.95 | HAC Steady SE | Residual stationarity is generally good |

| Bus | 8.36 | 1.46 | 0.22 | 0.39 | Newey–West correction | Slight autocorrelation exists, but the residuals are acceptable. |

| Taxi | 7.28 | 1.16 | 0.058 | / | Newey–West Remains Stable After Adjustment | The residuals showed slight autocorrelation but did not constitute a spurious regression. |

| Ordinary truck | 1.00 | 1.16 | 0.27 | / | Log-diff robustness test | Slight autocorrelation but acceptable residual randomness. |

| Minivan | 1.00 | 2.89 | 0.09 | / | No corrections needed | autocorrelation disappears. |

| Scenarios | Emissions in 2050 (kt CO2) | Cumulative Emissions (kt CO2) | 2050 Emission Reduction Ratio (VS BAU) (%) | Cumulative Emission Reduction Ratio (VS BAU) (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BAU | 3044.90 | 93,296.10 | / | / |

| A1 | 2824.40 | 89,963.80 | 7.24 | 3.57 |

| A2 | 2913.20 | 90,845.20 | 4.33 | 2.63 |

| A3 | 2854.80 | 90,051.90 | 6.24 | 3.48 |

| B | 1030.00 | 68,535.30 | 66.17 | 26.54 |

| C | 2834.70 | 88,801.70 | 6.90 | 4.82 |

| A1B | 680.20 | 63,627.30 | 77.66 | 31.80 |

| A2B | 670.80 | 63,955.20 | 77.97 | 31.45 |

| A3B | 680.50 | 63,531.70 | 77.65 | 31.90 |

| A1C | 2672.50 | 86,168.30 | 12.23 | 7.64 |

| A2C | 2761.30 | 87,049.40 | 9.31 | 6.70 |

| A3C | 2696.70 | 86,214.70 | 11.44 | 7.59 |

| A1BC | 528.30 | 59,831.80 | 82.65 | 35.87 |

| A2BC | 519.00 | 60,159.40 | 82.96 | 35.52 |

| A3BC | 522.30 | 59,694.50 | 82.85 | 36.02 |

| Sectors | CO2 Emissions (kt) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2021 | 2025 | 2030 | 2035 | 2040 | 2045 | 2050 | Cumulative Emission | |

| Railway | 1292.50 | 1680.50 | 1565.50 | 1202.30 | 820.90 | 418.60 | 0 | 31,574.60 |

| Bus | 188.10 | 444.90 | 439.80 | 390.40 | 354.30 | 344.30 | 338.90 | 11,539.00 |

| Taxi | 10.10 | 8.90 | 4.90 | 3.00 | 2.00 | 1.50 | 0.10 | 127.60 |

| Ordinary truck | 769.10 | 749.70 | 602.90 | 464.10 | 348.00 | 250.40 | 165.80 | 14,245.40 |

| Minivan | 112.80 | 137.30 | 103.20 | 72.10 | 50.80 | 34.90 | 23.50 | 2345.30 |

| Total | 2372.60 | 3021.30 | 2716.30 | 2131.90 | 1576.00 | 1049.70 | 528.30 | 59,831.90 |

| Policy Leverage | National Level | Tokyo Metropolitan Area | Scenario Correspondence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Decarbonization of power systems | Power structure objectives, market rules, power grid planning and investment, national carbon policy and subsidy framework. | Local renewable energy promotion, green electricity procurement for public buildings/public institutions, demand-side management and demonstration. | B (Electricity Emission Factor) |

| Decarbonization of Hydrogen Supply | Hydrogen Energy Strategy, Supply Chain Planning, Standards and Certification, National Subsidies/Demonstrations. | Site Layout and Permit Coordination, Demonstration Operations, Public Procurement-Driven. | B (Hydrogen Emission Factor) |

| Vehicle Technology and Access | Vehicle Regulations and Standards, Fuel Efficiency/Emission Controls, National Purchase Subsidies and Tax System. | Local Subsidies, Government Procurement Priority, Low Emission Zones/Delivery Management. | A (ZEVs replacement) |

| Infrastructure | National Subsidy Mechanism, Technical Standards, Cross-Regional Trunk Network Planning. | Site Selection, Permitting, Land Use Coordination, Public Station Renovation. | A (ZEVs replacement Feasibility) |

| Operational efficiency and demand management | Industry guidelines and standards, partial funding support. | Bus route and fleet scheduling optimization, urban logistics organization, congestion/parking management, public transportation guidance. | C (Energy efficiency) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Kong, D.; Li, L.; Kong, D.; Sun, S.; Qian, X. Policy Synergy Scenarios for Tokyo’s Passenger Transport and Urban Freight: An Integrated Multi-Model LEAP Assessment. Energies 2026, 19, 366. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020366

Kong D, Li L, Kong D, Sun S, Qian X. Policy Synergy Scenarios for Tokyo’s Passenger Transport and Urban Freight: An Integrated Multi-Model LEAP Assessment. Energies. 2026; 19(2):366. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020366

Chicago/Turabian StyleKong, Deming, Lei Li, Deshi Kong, Shujie Sun, and Xuepeng Qian. 2026. "Policy Synergy Scenarios for Tokyo’s Passenger Transport and Urban Freight: An Integrated Multi-Model LEAP Assessment" Energies 19, no. 2: 366. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020366

APA StyleKong, D., Li, L., Kong, D., Sun, S., & Qian, X. (2026). Policy Synergy Scenarios for Tokyo’s Passenger Transport and Urban Freight: An Integrated Multi-Model LEAP Assessment. Energies, 19(2), 366. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020366