Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) in the Energy and Heating Sectors: Current Practices and Future Directions

Abstract

1. Introduction

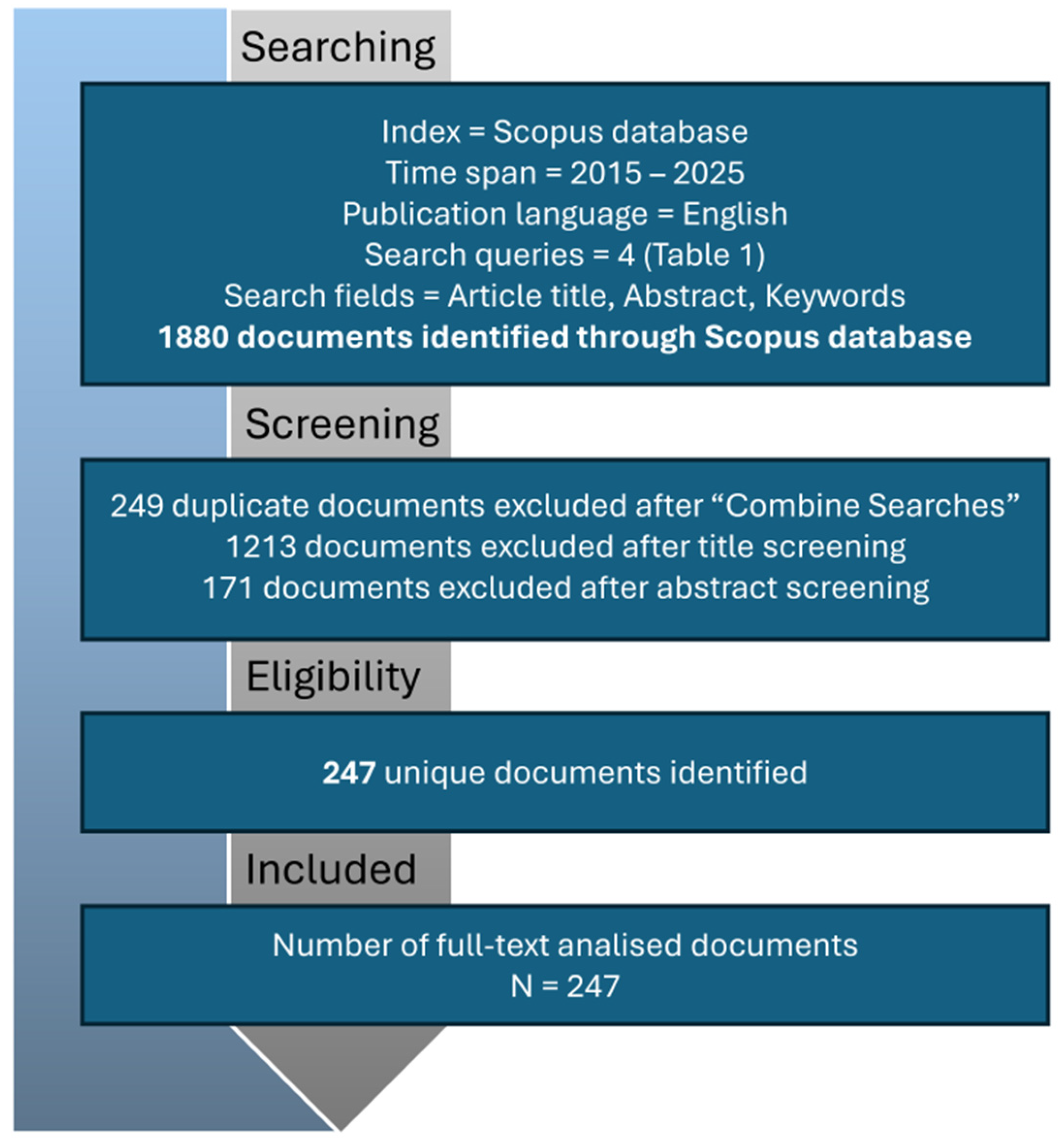

2. Materials and Methods

- The focus was exclusively on the optimization or design of the UAV itself, rather than its practical application in the energy sector.

- The article’s primary subject was peripherally related (e.g., security or logistics) with only marginal reference to energy sector inspection.

- (IC1) The article clearly described the methodology of using UAVs for inspection, maintenance, or monitoring of the defined energy or district heating infrastructure.

- (IC2) The research provided sufficient data (quantitative or qualitative) on the practical application of UAVs.

3. The Development of UAVs—An Emerging Technology Sector

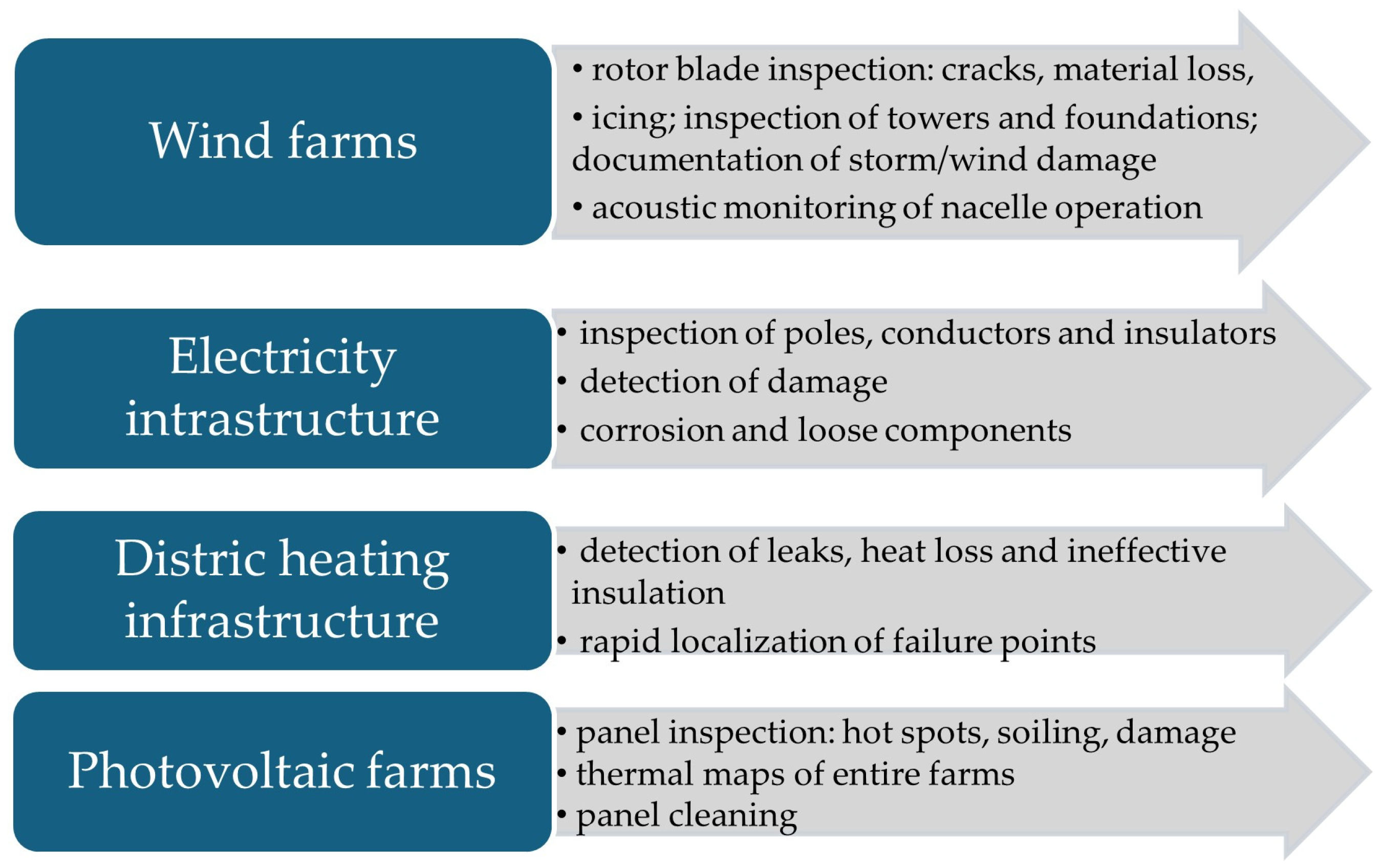

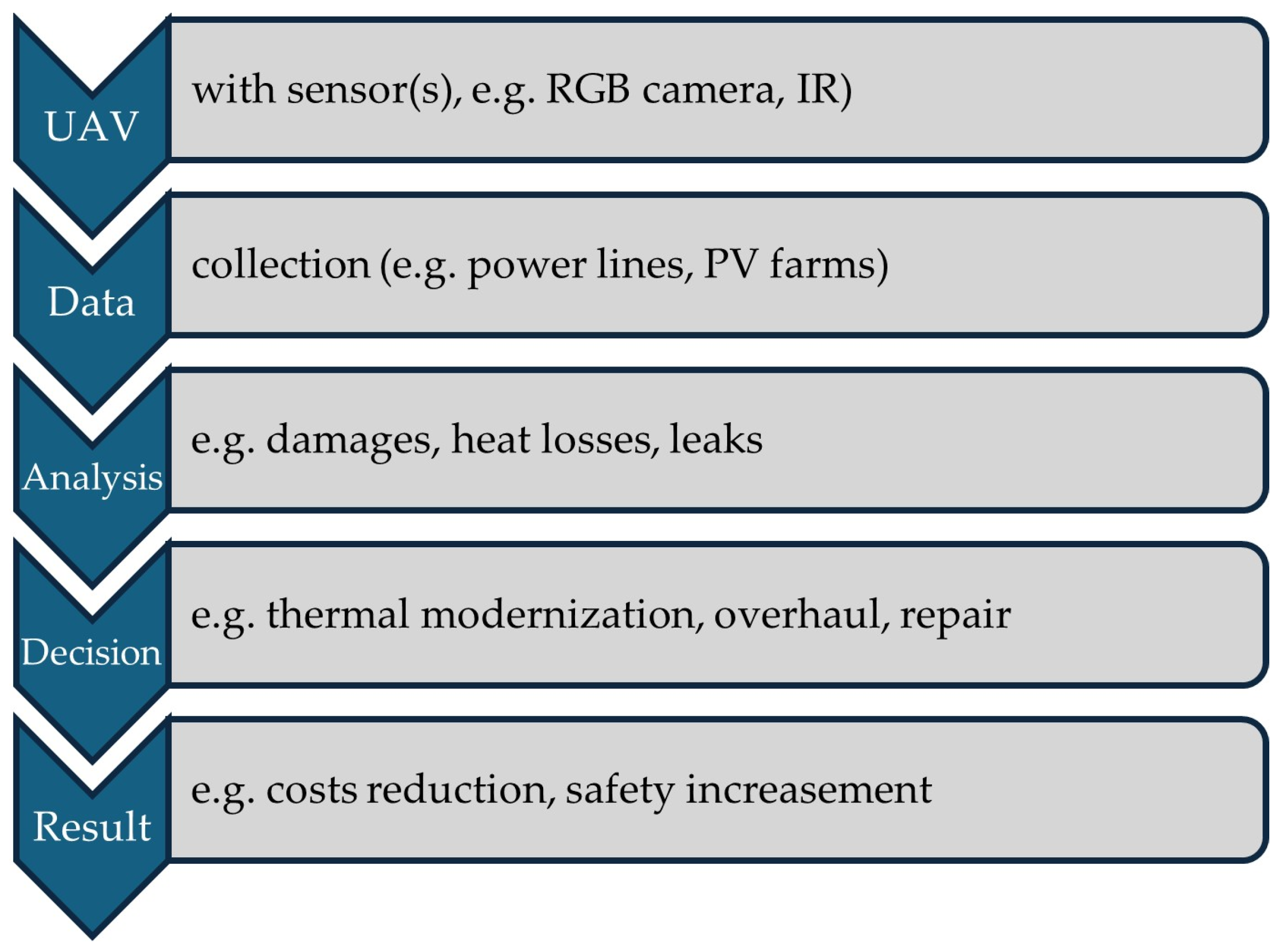

4. The Applications of UAVs in the Energy and Heating Sectors

4.1. Use of UAVs in Photovoltaic Farms

4.2. Use of UAVs in Wind Farms

4.3. Use of UAVs in Electricity Infrastructure Monitoring

4.4. Use of UAVs in District Heating Infrastructure Monitoring

5. Regulatory Barriers to the UAV Use in the Energy and Heating Sectors

5.1. Authorisation of BVLOS and Autonomous Operations

5.2. Airspace Integration and Traffic Management (UTM/U-Space)

5.3. Certification, Airworthiness, and Operator Competence (Including AI/Autonomy Certification)

5.4. Data Protection, Privacy, and Surveillance Law

6. Conclusions

- UAVs significantly reduce inspection time and operational costs while increasing safety by replacing manual, high-risk inspections.

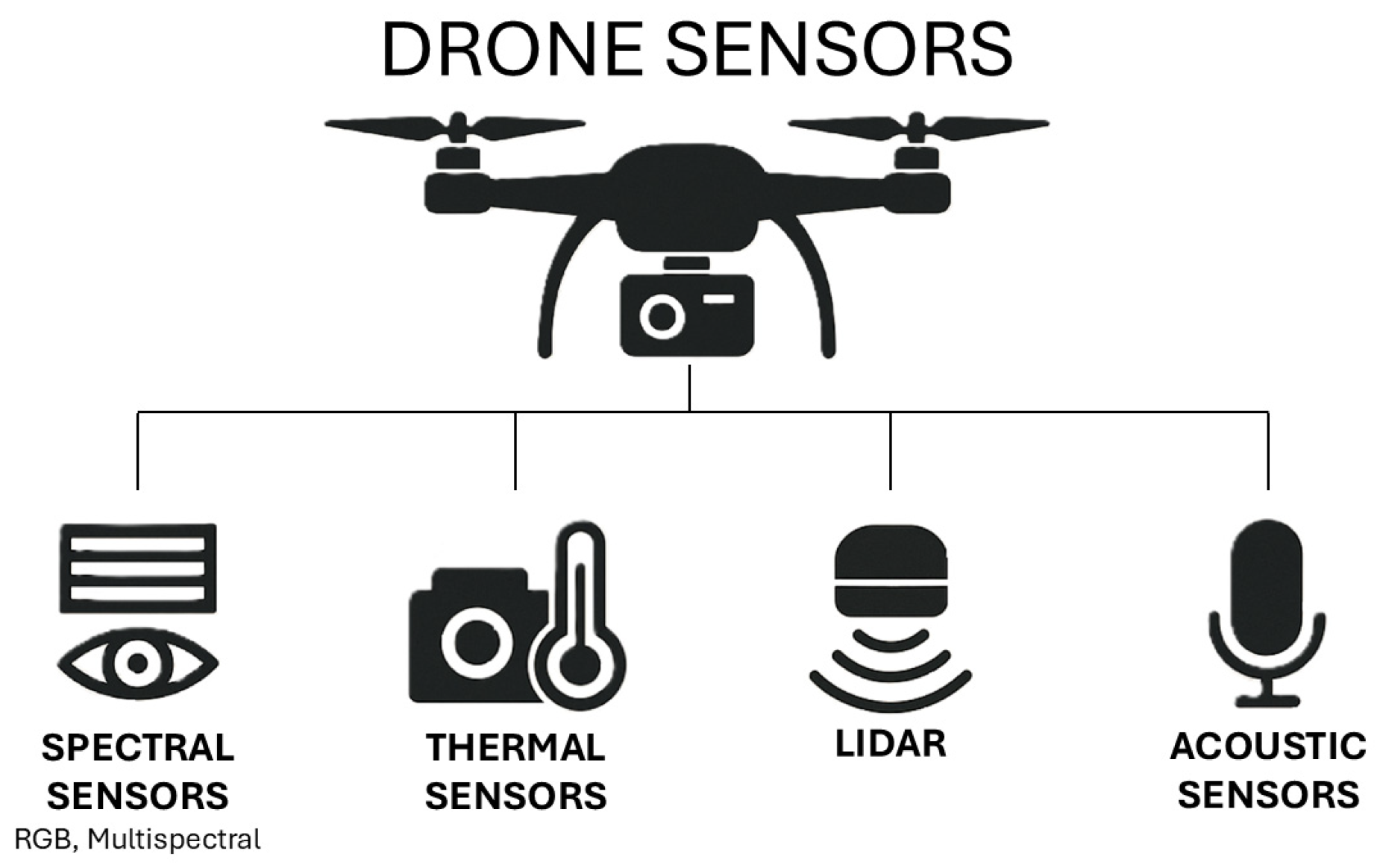

- Multi-sensor UAVs (RGB, multispectral, IR, LiDAR, acoustic) provide complementary information essential for effective defect detection.

- Integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning enables automated detection and classification, as well as supports predictive maintenance.

- Developing solutions for key technical constraints: limited flight time, limited autonomy, weather sensitivity, and limited resistance to electromagnetic interference.

- Further development and refinement of solutions for the transmission/processing of large amounts of data.

- Development of protocols for coordinating the simultaneous collection and processing of data from multiple UAVs equipped with different sensors.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| UAV | Unmanned Aerial Vehicle |

| IR | Infrared |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| RGB | Visible spectrum (R—red, G—green, B—blue) |

| LiDAR | Light Detection and Ranging |

| PV | Photovoltaics |

| BVLOS | Beyond Visual Line of Sight |

| EASA | European Union Aviation Safety Agency |

| FAA | Federal Aviation Administration (US) |

| CAAC | Civil Aviation Administration of China |

| SORA | Specific Operations Risk Assessment |

| UTM | Unmanned Traffic Management |

| DIPA | Data Protection Impact Assessments |

| GDPR | General Data Protection Regulation |

References

- International Energy Agency. Global Energy Review 2025; International Energy Agency: Paris, France, 2025.

- Graham, E.; Fulghum, N.; Altieri, K. Global Electricity Review 2025; EMBER: London, UK, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, B.; Maurer, J.; Gong, W. Applications of UAV in Landslide Research: A Review. Landslides 2025, 22, 3029–3048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, R.; Allen, C.; Masoum, M.A.S.; Seibi, A. Defect Detection and Classification on Wind Turbine Blades Using Deep Learning with Fuzzy Voting. Machines 2025, 13, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, H.; Sun, X.; Su, Y.; Hu, T.; Wang, H.; Wang, H.; Peng, C.; Guo, Q. UAV-Lidar Aids Automatic Intelligent Powerline Inspection. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2021, 130, 106987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, T.; Cunha, T.; Dias, A.; Moreira, A.P.; Almeida, J. UAV Visual and Thermographic Power Line Detection Using Deep Learning. Sensors 2024, 24, 5678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koolivand, Y.; Jan Szczerek, W.; Kofod Dahl, M.; Bendtsen, J.M.H.; Rezaeiyan, Y.; Richter, S.; Laursen, K.; Mosalmani, A.; Maurya, P.; Sadeghi, M.; et al. Thermally Powered Autonomous Water Leakage Detection System for District Heating Pipes. IEEE Sens. J. 2025, 25, 32953–32963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinde, P. Solar Panel Inspection and Cleaning Drone. Int. J. Res. Appl. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2025, 13, 2951–2954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, M.; Nazario Dejesus, E.; Shekaramiz, M.; Zander, J.; Memari, M. Identification and Localization of Wind Turbine Blade Faults Using Deep Learning. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 6319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Protić, M.P.; Ilić, Z.M.; Krstić, V.; Stojanović, M.B. Utilizing Unmanned Aerial Vehicles for Detecting Heat Losses in District Heating Networks. In Proceedings of the 2024 59th International Scientific Conference on Information, Communication and Energy Systems and Technologies (ICEST), Sozopol, Bulgaria, 1–3 July 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ince, E. Transmission Line Inspection with UAVs: A Review of Technologies, Applications, and Challenges. Int. J. Energy Smart Grid 2024, 9, 60–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayomi, N.; Fernandez, J.E. Eyes in the Sky: Drones Applications in the Built Environment under Climate Change Challenges. Drones 2023, 7, 637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, S.-J.; Na, W.S. Review of Drone-Based Technologies for Wind Turbine Blade Inspection. Electronics 2025, 14, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hariharan, R.; Saxena, A.; Dhote, V.; Srisathirapathy, S.; Almusawi, M.; Raja Kumar, J.R. Advancements in Solar-Powered UAV Design Leveraging Machine Learning: A Comprehensive Review. In Proceedings of the E3S Web of Conferences; EDP Sciences: Les Ulis, France, 2024; Volume 540. [Google Scholar]

- Aromoye, I.A.; Lo, H.H.; Sebastian, P.; Mustafa Abro, G.E.; Ayinla, S.L. Significant Advancements in UAV Technology for Reliable Oil and Gas Pipeline Monitoring. CMES-Comput. Model. Eng. Sci. 2025, 142, 1155–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corley, I.; Wallace, C.; Agrawal, S.; Putrah, B.; Lwowski, J. Aerial Infrared Health Monitoring of Solar Photovoltaic Farms at Scale. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.02128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barraz, Z.; Sebari, I.; Ait El Kadi, K.; Ait Abdelmoula, I. Towards a Holistic Approach for UAV-Based Large-Scale Photovoltaic Inspection: A Review on Deep Learning and Image Processing Techniques. Technologies 2025, 13, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghaei, M.; Kolahi, M.; Nedaei, A.; Venkatesh, N.S.; Esmailifar, S.M.; Moradi Sizkouhi, A.M.; Aghamohammadi, A.; Oliveira, A.K.V.; Eskandari, A.; Parvin, P.; et al. Autonomous Intelligent Monitoring of Photovoltaic Systems: An In-Depth Multidisciplinary Review. Prog. Photovolt. Res. Appl. 2025, 33, 381–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olayiwola, O.; Camara, F. Challenges and Opportunities for Autonomous UAV Inspection in Solar Photovoltaics. In Proceedings of the E3S Web of Conferences; EDP Sciences: Les Ulis, France, 2024; Volume 572. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, K.-C.; Lu, J.-H. Using UAV to Detect Solar Module Fault Conditions of a Solar Power Farm with Ir and Visual Image Analysis. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regulation (EU). Regulation (EU) 2018/1139 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 4 July 2018 on Common Rules in the Field of Civil Aviation and Establishing a European Union Aviation Safety Agency; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Government Publishing Office. An Act to Amend Title 49, United States Code, to Authorize Appropriations for the Federal Aviation Administration for Fiscal Years 2011 Through 2014, to Streamline Programs, Create Efficiencies, Reduce Waste, and Improve Aviation Safety and Capacity, to Provide Stable Funding for the National Aviation System, and for Other Purposes; Public Law 112-95, S. 331(8); U.S. Government Publishing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 2012.

- Dekoulis, G. Introductory Chapter: Drones. In Drones: Applications; Dekoulis, G., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2018; pp. 3–6. [Google Scholar]

- Studiawan, H.; Choo, K.-K.R. Drone and UAV Forensics. A Hands-On Approach; Studiawan, H., Choo, K.-K.R., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Kahvecioglu, S.; Oktal, H. Historical Development of UAV Technologies in the World: The Case of Turkey. In Sustainable Aviation. Energy and Environmental Issues; Karakoc, T.H., Ozerdem, M.B., Sogut, M.Z., Colpan, C.O., Altuntas, O., Açıkkalp, E., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 323–331. [Google Scholar]

- Mazur, R.; Kowalewski, Z.; Głowienka, E.; Santos, L.; Jakubiak, M. Sustainability in Aquatic Ecosystem Restoration: Combining Classical and Remote Sensing Methods for Effective Water Quality Management. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubiak, M. The Use of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles to Retard the Transformation of Environmental Resources. Pol. J. Sustain. Dev. 2024, 28, 107–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyka, K.; Wiącek, P.; Guzik, M. Surveying with Photogrammetric Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. Arch. Photogramm. Cartogr. Remote Sens. 2020, 32, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stöcker, C.; Bennett, R.; Nex, F.; Gerke, M.; Zevenbergen, J. Review of the Current State of UAV Regulations. Remote Sens. 2017, 9, 459. [Google Scholar]

- Mohsan, S.A.H.; Khan, M.A.; Noor, F.; Ullah, I.; Alsharif, M.H. Towards the Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs): A Comprehensive Review. Drones 2022, 6, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ucgun, H.; Yuzgec, U.; Bayilmis, C. A Review on Applications of Rotary-Wing Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Charging Stations. Int. J. Adv. Robot. Syst. 2021, 18, 17298814211015863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendu, B.; Mbuli, N. State-of-the-Art Review on the Application of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) in Power Line Inspections: Current Innovations, Trends, and Future Prospects. Drones 2025, 9, 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollmer, E.; Ruck, J.; Volk, R.; Schultmann, F. Detecting District Heating Leaks in Thermal Imagery: Comparison of Anomaly Detection Methods. Autom. Constr. 2024, 168, 105709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakubiak, M.; Sroka, K.; Kovalova, A. Multifunctional Applications of Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) in Ecosystem Management: Agriculture and Forestry Perspective. J. Int. Sci. Publ. Ecol. Saf. 2025, 19, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, D.; Borri, A.; Cappuzzo, F.; Di Gennaro, S. Quadrotor Trajectory Control Based on Energy-Optimal Reference Generator. Drones 2024, 8, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Telli, K.; Kraa, O.; Himeur, Y.; Ouamane, A.; Boumehraz, M.; Atalla, S.; Mansoor, W. A Comprehensive Review of Recent Research Trends on Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs). Systems 2023, 11, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakhatreh, H.; Sawalmeh, A.H.; Al-Fuqaha, A.; Dou, Z.; Almaita, E.; Khalil, I.; Othman, N.S.; Khreishah, A.; Guizani, M. Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs): A Survey on Civil Applications and Key Research Challenges. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 48572–48634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bemposta Rosende, S.; Sánchez-Soriano, J.; Gómez Muñoz, C.Q.; Fernández Andrés, J. Remote Management Architecture of UAV Fleets for Maintenance, Surveillance, and Security Tasks in Solar Power Plants. Energies 2020, 13, 5712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walpita, H.L.; Roosloot, N.; Otnes, G.; Aarseth, B.L.; Selj, J.; Nysted, V.S.; Marstein, E.S. Operation and Maintenance of Floating PV Systems: A Review. IEEE J. Photovolt. 2025, 15, 400–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pruthviraj, U.; Kashyap, Y.; Baxevanaki, E.; Kosmopoulos, P. Solar Photovoltaic Hotspot Inspection Using Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Thermal Images at a Solar Field in South India. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bommes, L.; Pickel, T.; Buerhop-Lutz, C.; Hauch, J.; Brabec, C.; Peters, I.M. Computer Vision Tool for Detection, Mapping, and Fault Classification of Photovoltaics Modules in Aerial IR Videos. Prog. Photovolt. Res. Appl. 2021, 29, 1236–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akay, S.S.; Özcan, O.; Özcan, O.; Yetemen, Ö. Efficiency Analysis of Solar Farms by UAV-Based Thermal Monitoring. Eng. Sci. Technol. Int. J. 2024, 53, 101688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamarulzaman, A.M.M.; Jaafar, W.S.W.M.; Bakar, N.A.A.; Chew, K.; Anuar, N.I.K.; Anuar, A.I.; Som, A.F.M.; Zamri, S.M.; Zainorzuli, M.Z.H. Comprehensive Analysis of Solar Photovoltaic System Defects and Inspection Techniques in Tropical Environments Using Thermal UAV: Study Case in Marang, Terengganu. In Proceedings of the E3S Web of Conferences; EDP Sciences: Les Ulis, France, 2025; Volume 599. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, W.; Yang, Q.; Hu, X.; Yan, W. Edge Intelligence for Smart EL Images Defects Detection of PV Plants in the IoT-Based Inspection System. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 10, 3047–3056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Gong, B.; Ma, B.; Tao, Z.; Wang, S. Lightweight Vision Architecture with Mutual Distillation for Robust Photovoltaic Defect Detection in Complex Environments. Sol. Energy 2025, 291, 113386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.T.; Zhang, J.T.; Liu, Y.; Liu, K.; Wang, Q.P. Spray-on Steady-State Study of Multi-Rotor Cleaning Unmanned Aerial Vehicle in Operation of Photovoltaic Power Station. Energy Rep. 2024, 11, 5638–5653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, W.H.; Wu, H.S.; Wu, J.S.; Lin, S.J. A Method for Estimating On-Field Photovoltaics System Efficiency Using Thermal Imaging and Weather Instrument Data and an Unmanned Aerial Vehicle. Energies 2022, 15, 5835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pu, J.; Zhang, Q.; Zhao, W.; Zhang, W.; Qin, Z.; Zhang, Y. Research on Refined UAV Inspection Method of Wind/Solar Power Stations Based on YOLOv8. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2025, 72, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Z. Image Acquisition Technology for Unmanned Aerial Vehicles Based on YOLO—Illustrated by the Case of Wind Turbine Blade Inspection. Syst. Soft Comput. 2024, 6, 200126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masita, K.; Hasan, A.N.; Shongwe, T.; Hilal, H.A. Deep Learning in Defect Detection of Wind Turbine Blades: A Review. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 98399–98425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Shu, Z. Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV)-Assisted Damage Detection of Wind Turbine Blades: A Review. Energies 2024, 17, 3731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernalte Sánchez, P.; Segovia Ramírez, I.; García Márquez, F.; Pedro Marugán, A.P. Acoustic Signals Analysis from an Innovative UAV Inspection System for Wind Turbines. Struct. Health Monit. 2025, 24, 2762–2775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gohar, I.; Yew, W.K.; Halimi, A.; See, J. Review of State-of-the-Art Surface Defect Detection on Wind Turbine Blades through Aerial Imagery: Challenges and Recommendations. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 144, 109970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzon, H.-H.; Chen, X.; Belcher, L.; Castro, O.; Branner, K.; Smit, J. An Operational Image-Based Digital Twin for Large-Scale Structures. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 3216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Benzon, H.-H.; Chen, X. Mapping Damages from Inspection Images to 3D Digital Twins of Large-Scale Structures. Eng. Rep. 2025, 7, e12837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Fang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Z.; Verma, A.S.; Liu, H.; Cong, F.; Tan, J. Digital Twin of Wind Turbine Surface Damage Detection Based on Deep Learning-Aided Drone Inspection. Renew. Energy 2025, 241, 122332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banaszak, Z.; Radzki, G.; Nielsen, I.; Frederiksen, R.; Bocewicz, G. Proactive Mission Planning of Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Fleets Used in Offshore Wind Farm Maintenance. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Jovan, F.; Moradi, P.; Richardson, T.; Bernardini, S.; Watson, S.; Weightman, A.; Hine, D. A Multirobot System for Autonomous Deployment and Recovery of a Blade Crawler for Operations and Maintenance of Offshore Wind Turbine Blades. J. Field Robot. 2023, 40, 73–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontenla-Carrera, G.; Aldao Pensado, E.; Veiga-López, F.; González-Jorge, H. Efficient Offshore Wind Farm Inspections Using a Support Vessel and UAVs. Ocean Eng. 2025, 332, 121416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismail, A.H.; Song, X.; Ouelhadj, D.; Al-Behadili, M.; Fraess-Ehrfeld, A. Unmanned Surface Vessel Routing and Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Swarm Scheduling for Off-Shore Wind Turbine Blade Inspection. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 284, 127534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Li, W.; Liu, C.; He, X.; Li, K. A High-Efficiency Task Allocation Algorithm for Multiple Unmanned Aerial Vehicles in Offshore Wind Power Under Energy Constraints. J. Mar. Sci. Eng. 2025, 13, 1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Wang, G.; Lu, Y.; Jia, Z. Study on a Boat-Assisted Drone Inspection Scheme for the Modern Large-Scale Offshore Wind Farm. IEEE Syst. J. 2023, 17, 4509–4520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faisal, M.A.A.; Mecheter, I.; Qiblawey, Y.; Fernandez, J.H.; Chowdhury, M.E.H.; Kiranyaz, S. Deep Learning in Automated Power Line Inspection: A Review. Appl. Energy 2025, 385, 125507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shams, F.; Omar, M.; Usman, M.; Khan, S.; Larkin, S.; Raw, B. Thermal Imaging of Utility Power Lines: A Review. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Engineering and Emerging Technologies (ICEET), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 27–28 October 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Lyu, C.; Lin, S.; Lynch, A.; Zou, Y.; Liarokapis, M. UAV-Based Deep Learning Applications for Automated Inspection of Civil Infrastructure. Autom. Constr. 2025, 177, 106285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Z.; Gong, H.; Jin, Q.; Hu, Q.; Wang, S. A Transmission Tower Tilt State Assessment Approach Based on Dense Point Cloud from UAV-Based LiDAR. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savino, P.; Graglia, F.; Scozza, G.; Di Pietra, V. Automated Corrosion Surface Quantification in Steel Transmission Towers Using UAV Photogrammetry and Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. Comput.-Aided Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 2025, 40, 2050–2070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osmani, K.; Schulz, D. A Drone-Deployable Remote Current Sensor for Non-Invasive Overhead Transmission Lines Monitoring. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 62393–62411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, R.L.; Sanchez, M.J.B.; Jimenez, M.P.; Arrue, B.C.; Ollero, A. Autonomous UAV System for Cleaning Insulators in Power Line Inspection and Maintenance. Sensors 2021, 21, 8488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Liu, Z.; Xu, C.; Zhang, Y. A Multiple Sensors Platform Method for Power Line Inspection Based on a Large Unmanned Helicopter. Sensors 2017, 17, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Dekyi, D.; Metok, M. Efficient Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Inspection and Management of Transmission Lines in Modern Electric Power Enterprises. Energy Inform. 2025, 8, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.; Jeon, M.; Lee, J.K.; Oh, K.Y. Environmental Infringement and Sag Estimation for Power Transmission Lines with Unmanned Aerial Vehicles and Multi-Modal Sensors. Comput.-Aided Civ. Infrastruct. Eng. 2025, 40, 4342–4363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, G.; Liu, L.; Liu, Z.; Wen, B.; Li, L.; Ye, Y. Real-Time Detection Method of Typical Defects in Transmission Line under Complex Lighting and Backgrounds. Clust. Comput. 2025, 28, 1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.; Sun, Q.; Liu, J.; Liu, R. ES-YOLOv8: A Real-Time Defect Detection Algorithm in Transmission Line Insulators. J. Real Time Image Process. 2025, 22, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Fang, H.; Pang, Y.; Zhu, G.; Qian, Z. PL-UNet: A Real-Time Power Line Segmentation Model for Aerial Images Based on Adaptive Fusion and Cross-Stage Multi-Scale Analysis. J. Real Time Image Process. 2025, 22, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jim Hassan, T.; Jangula, J.; Ramchandra, A.R.; Sugunaraj, N.; Chandar, B.S.; Rajagopalan, P.; Rahman, F.; Ranganathan, P.; Adams, R. UAS-Guided Analysis of Electric and Magnetic Field Distribution in High-Voltage Transmission Lines (Tx) and Multi-Stage Hybrid Machine Learning Models for Battery Drain Estimation. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 4911–4939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Chen, M.; Jin, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, H.; Yi, L.; Cai, L. Research on Electromagnetic Safety of UAV Inspection in Substation. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 78097–78106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehi Rad, S.; Zheng, Z.; Kheirollahi, R.; Mostafa, A.; Zhao, S.; Wang, Y.; Chevinly, J.; Nadi, E.; Bensala, T.; Zhang, H.; et al. Electromagnetic Interference on Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs): A Case Study of High Power Transmission Line Impacts. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2025, 11, 7501–7513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollmer, E.; Volk, R.; Schultmann, F. Automatic Analysis of UAS-Based Thermal Images to Detect Leakages in District Heating Systems. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2023, 44, 7263–7293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sledz, A.; Unger, J.; Heipke, C. UAV-Based Thermal Anomaly Detection for Distributed Heating Networks. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2020, XLIII-B1-2020, 499–505. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, K.; Villebro, F.; Forchhammer, S. UAV Image Analysis for Leakage Detection in District Heating Systems Using Machine Learning. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2020, 140, 158–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Xu, Y.; Wang, X.; Jia, T.; Xia, G.; Ma, A.; Zhang, L. Pipeline Leakage Detection for District Heating Systems Using Multisource Data in Mid- and High-Latitude Regions. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2019, 151, 207–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usamentiaga, R. Semiautonomous Pipeline Inspection Using Infrared Thermography and Unmanned Aerial Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2024, 20, 2540–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sledz, A.; Heipke, C. Thermal Anomaly Detection Based on Saliency Analysis from Multimodal Imaging Sources. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2021, 5, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lenda, G.; Borowiec, N.; Marmol, U. Study of the Precise Determination of Pipeline Geometries Using UAV Scanning Compared to Terrestrial Scanning, Aerial Scanning and UAV Photogrammetry. Sensors 2023, 23, 8257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borowski, L.; Kudrys, J.; Kubicki, B.; Slámová, M.; Maciuk, K. Phase Centre Corrections of GNSS Antennas and Its Consistency with ATX Catalogues. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 3226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudrys, J.; Prochniewicz, D.; Zhang, F.; Jakubiak, M.; Maciuk, K. Identification of BDS Satellite Clock Periodic Signals Based on Lomb-Scargle Power Spectrum and Continuous Wavelet Transform. Energies 2021, 14, 7155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vollmer, E.; Ruck, J.; Volk, R.; Schultmann, F. Leak Detection Using Thermal Imagery: Deep Learning versus Traditional Computer Vision State-of-the-Art. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2025, 228, 505–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.; Yu, F.; Hao, M.; Wu, M.; Chen, D.; Bu, C.; Lu, P.; Du, Y.; Cui, K. Leakage Diagnosis Technologies for Heating Pipe Networks: A Comprehensive Review of Currently Used Methods. Int. J. Energy Res. 2025, 2025, 8824853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadhil, T.H.; Al-Haddad, L.A.; Al-Karkhi, M.I. Legal Accountability and UAV Fault Diagnosis Explainable AI in Aviation Safety and Regulatory Compliance for Liability Challenges. Discov. Artif. Intell. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safie, S.; Khairil, R. Regulatory, Technical, and Safety Considerations for UAV-Based Inspection in Chemical Process Plants: A Systematic Review of Current Practice and Future Directions. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2025, 30, 101343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postorino, M.N.; Sarnè, G.M.L. Operational Performance of a 3D Urban Aerial Network and Agent-Distributed Architecture for Freight Delivery by Drones. Drones 2025, 9, 759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, H.A. Advances in UAV Avionics Systems Architecture, Classification and Integration: A Comprehensive Review and Future Perspectives. Results Eng. 2025, 25, 103786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union Commission. Commission Implementing Regulation (EU) 2019/947 of 24 May 2019 on the Rules and Procedures for the Operation of Unmanned Aircraft; Regulation (EU) 2019/947; European Union Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Federal Aviation Administration. Small Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS) Regulations. 14 C.F.R. Part 107. 2016. Available online: https://www.faa.gov/newsroom/small-unmanned-aircraft-systems-uas-regulations-part-107 (accessed on 16 December 2025).

- Office of Inspector General, U.S. Department of Transportation. FAA Has Made Progress in Advancing BVLOS Drone Operations but Can Do More to Achieve Program Goals and Improve Data Analysis; Office of Inspector General, U.S. Department of Transportation: Washington, DC, USA, 2025.

- The State Council of the People’s Republic of China; The Central Military Commission of the People’s Republic of China. Interim Regulation on the Administration of the Flight of Unmanned Aircraft; Order No. 761; The State Council of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China; The Central Military Commission of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2023.

- Civil Aviation Administration of China (CAAC). Regulations on Real-Name Registration of Civil Unmanned Aircraft Systems; No. AP-45-AA-2017-03; Civil Aviation Administration of China (CAAC): Beijing, China, 2017.

- Liu, M.; Liu, S. Comparative Study on the Legal Supervision System of Low-Altitude Aircraft in China and Europe Based on Key Risks. Eng. Proc. 2024, 18, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grote, M.; Pilko, A.; Scanlan, J.; Cherrett, T.; Dickinson, J.; Smith, A.; Oakey, A.; Marsden, G. Sharing Airspace with Uncrewed Aerial Vehicles (UAVs): Views of the General Aviation (GA) Community. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2022, 102, 102218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EASA. Guidelines for UAS Operations in the Open and Specific Category—Ref to Regulation (EU) 2019/947; EASA: Brussels, Belgium, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Konert, A.; Kotlinski, M. U-Space—Civil Liability for Damages Caused by Unmanned Aircraft. Transp. Res. Procedia 2020, 51, 304–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatfield, M.; Cahill, C.; Webley, P.; Garron, J.; Beltran, R. Integration of Unmanned Aircraft Systems into the National Airspace System-Efforts by the University of Alaska to Support the FAA/NASA UAS Traffic Management Program. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Aviation Administration (FAA). Normalizing Unmanned Aircraft Systems Beyond Visual Line of Sight Operations; No. FAA-2025-1908; Notice No. 25-07; Federal Aviation Administration (FAA): Washington, DC, USA, 2025.

- Yao, J. The Practice and Problems of UAVs Regulation and Legislation in Local China from the Perspective of Public Safety. Open J. Soc. Sci. 2021, 9, 54–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolahi, M.; Esmailifar, S.M.; Moradi Sizkouhi, A.M.; Aghaei, M. Digital-PV: A Digital Twin-Based Platform for Autonomous Aerial Monitoring of Large-Scale Photovoltaic Power Plants. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 321, 118963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohi, G.; Ejofodomi, O.; Ofualagba, G. Autonomous Monitoring, Analysis, and Countering of Air Pollution Using Environmental Drones. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EASA. Guidelines for the Assessment of the Critical Area of an Unmanned Aircraft; EASA: Brussels, Belgium, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Civil Aviation Administration of China (CAAC). Regulations on the Management of Civil Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Operation Safety; No. AC-91-03; Civil Aviation Administration of China (CAAC): Beijing, China, 2017.

- Fehling, C.; Saraceni, A. Technical and Legal Critical Success Factors: Feasibility of Drones & AGV in the Last-Mile-Delivery. Res. Transp. Bus. Manag. 2023, 50, 101029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Li, X. Cross-Border Data Flow in China: Shifting from Restriction to Relaxation? Comput. Law Secur. Rev. 2025, 56, 106079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Chen, Y. Personal Data Protection in China: Progress, Challenges and Prospects in the Age of Big Data and AI. Telecomm. Policy 2025, 49, 103076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Search Query No. | Topic | Search String | Number of Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Photovoltaic farms | (“UAV” OR “Unmanned Aerial Vehicles” OR “drone”) AND (“photovoltaic farm” OR “solar farm” OR “solar power plant”) | 150 |

| 2 | Wind farms | (“UAV” OR “drone” OR “Unmanned Aerial Vehicles”) AND (“wind farm” OR “wind power plant”) | 170 |

| 3 | Power lines | (“UAV” OR “Unmanned Aerial Vehicles” OR “drone”) AND (“power line” OR “transmission line”) | 1948 |

| 4 | District Heating | (“UAV” OR “Unmanned Aerial Vehicles” OR “drone”) AND (“district heating” OR “heat network” OR “heating pipes” OR “city heating”) | 25 |

| Sensor | Purpose | Advantages | Limitations | Literature Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal Infrared (IR) Camera | Measuring surface temperature distribution. Detecting hotspots, which indicate potential cell failure. | Capability to identify thermal anomalies invisible to RGB. | Higher cost compared to RGB sensors. Susceptibility to environmental conditions. | [20,39,41,42,43,44] |

| RGB Camera | Inspecting surface physical conditions. Detecting visible contaminants. Geolocating and mapping modules. | Low cost and widely available. High spatial resolution for visualizing fine surface details. | Inability to detect internal electrical defects. Dependence on lighting conditions. | [20,39,43] |

| Electroluminescence (EL) Camera | Detecting internal defects such as micro-cracks, cell breakage. | Superiority in detecting structural defects missed by thermal and RGB. | Necessity of applying current to the PV module. High sensitivity to ambient daylight | [45,46] |

| Sensor | Purpose | Advantages | Limitations | Literature Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RGB Camera | Detecting surface damage. Creating a 3D model. | Provision of high-definition visual data for surface assessment. Cost-effectiveness and wide availability | Limitation to visible surface defects. Dependence on lighting and weather conditions. | [13,51,55,56,57] |

| LiDAR | Creating accurate 3D point clouds. Analysing blade deformation and tower lean. | Provision of accurate geometric measurements. Independence from lighting conditions. | High cost. Lower resolution for surface textures compared to photogrammetry. | [13,55] |

| Thermal Infrared (IR) Camera | Identifying overheating components. | Early identification of potential mechanical failures. | Higher cost compared to RGB sensors. Susceptibility to environmental conditions. | [13,51] |

| Ultrasonic | Identifying internal cracks and voids. | Capability to verify subsurface defects. | Requirement for physical contact with the surface. Requirement for complex, stable UAV. | [13] |

| Acoustic Emission | Detecting stress waves passively during active damage events. | Capability to capture dynamic structural issues. | Interference from drone rotor noise. Requirement for an active stress event to generate a signal. | [13,53] |

| Sensor | Purpose | Advantages | Limitations | Literature Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RGB Camera | Inspecting conductors, insulators, and towers. Detecting visible structural damage and rust. | Provision of high-detail imagery. Low cost and widely available. | Limitation to visible, surface-level issues. Requirement for good lighting and proximity. | [6,33,64,65,66,71,72] |

| Thermal Infrared (IR) Camera | Detecting overheating components. | Early identification of problems before failure or outages. Effectiveness for nighttime inspections. | Susceptibility to environmental conditions. Requirement for expert analysis to prioritize severity. | [6,71,72,73] |

| LiDAR | Creating precise 3D models. Measuring distances and modelling tower deformation. | Provision of accurate geometric measurements. Independence from lighting conditions. | High cost. Lower resolution for surface textures compared to photogrammetry. | [5,71,72,73] |

| Ultraviolet (UV) Camera | Monitoring electrical discharges on fittings and insulators. | Unique capability to visualize corona discharges invisible to IR/RGB. | Limitation to specific electrical faults. | [71] |

| Sensor | Purpose | Advantages | Limitations | Literature Sources |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal Infrared (IR) Camera | Identifying thermal anomalies or hot spots. | Suitability for detecting leaks in buried pipelines. | Susceptibility to environmental conditions. Requirement for specific flight times (e.g., early morning) to avoid solar influence. | [34,80,81,82,83,84,89] |

| RGB Camera | Acquiring auxiliary data, visual context, and spatial reference. | Provision of geographical context. Reduction of false alarms by creating a pipeline buffer/mask. | Inability to directly detect leaks. | [81,83] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Jakubiak, M.; Sroka, K.; Maciuk, K.; Abazeed, A.; Kovalova, A.; Santos, L. Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) in the Energy and Heating Sectors: Current Practices and Future Directions. Energies 2026, 19, 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010005

Jakubiak M, Sroka K, Maciuk K, Abazeed A, Kovalova A, Santos L. Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) in the Energy and Heating Sectors: Current Practices and Future Directions. Energies. 2026; 19(1):5. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010005

Chicago/Turabian StyleJakubiak, Mateusz, Katarzyna Sroka, Kamil Maciuk, Amgad Abazeed, Anastasiia Kovalova, and Luis Santos. 2026. "Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) in the Energy and Heating Sectors: Current Practices and Future Directions" Energies 19, no. 1: 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010005

APA StyleJakubiak, M., Sroka, K., Maciuk, K., Abazeed, A., Kovalova, A., & Santos, L. (2026). Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) in the Energy and Heating Sectors: Current Practices and Future Directions. Energies, 19(1), 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19010005