Full-Lifecycle Deterioration Characteristics and Remaining Life Prediction of ZnO Varistors Based on PSO-SVR and iForest

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background and Significance

1.2. Research Status and Deficiencies

1.3. Research Content and Innovations

1.3.1. Research Content

1.3.2. Main Innovations

- Construction of a full-lifecycle multi-parameter dataset: Addressing the gap of incomplete dataset coverage, an 8/20 μs impulse current accelerated deterioration experiment is conducted to collect 441 sets of valid data from nine same-batch samples, covering the entire process from initial state to complete failure. This dataset provides a complete data foundation for subsequent model construction and ensures that the model can reflect the full deterioration evolution law.

- Multi-parameter fusion characterization strategy: To fully capture the comprehensive information of the deterioration process, five core electrical parameters are integrated to construct a feature vector, leveraging their complementary responses across different degradation stages. PCA dimensionality reduction is used to eliminate redundant information, and the first principal component (PC1) with a variance contribution rate of 69.8% is selected as the input feature. The correlation coefficient between PC1 and the deterioration degree reached 0.96, which is significantly higher than that of any single parameter, effectively improving the accuracy and robustness of state assessment.

- Collaborative mechanism of prediction and threshold determination: To solve the disconnection between remaining life prediction and failure threshold determination, a “PSO-SVR + iForest” combined model is proposed. The PSO-SVR model realizes high-precision quantitative prediction of remaining life (test set = 0.9726), MSE = 0.00142) and the iForest model accurately identifies the failure threshold (AUC = 0.984, accuracy = 95.9%), realizing the synergy of life prediction and early warning.

2. Deterioration Experiment of ZnO Varistors

2.1. Deterioration Mechanism and Deterioration Characterization of ZnO Varistors

2.2. Experimental Design and Implementation

2.3. Experimental Results and Analysis of Deterioration Laws

3. Remaining Life Prediction Based on PCA and PSO-SVR

3.1. Principal Component Analysis

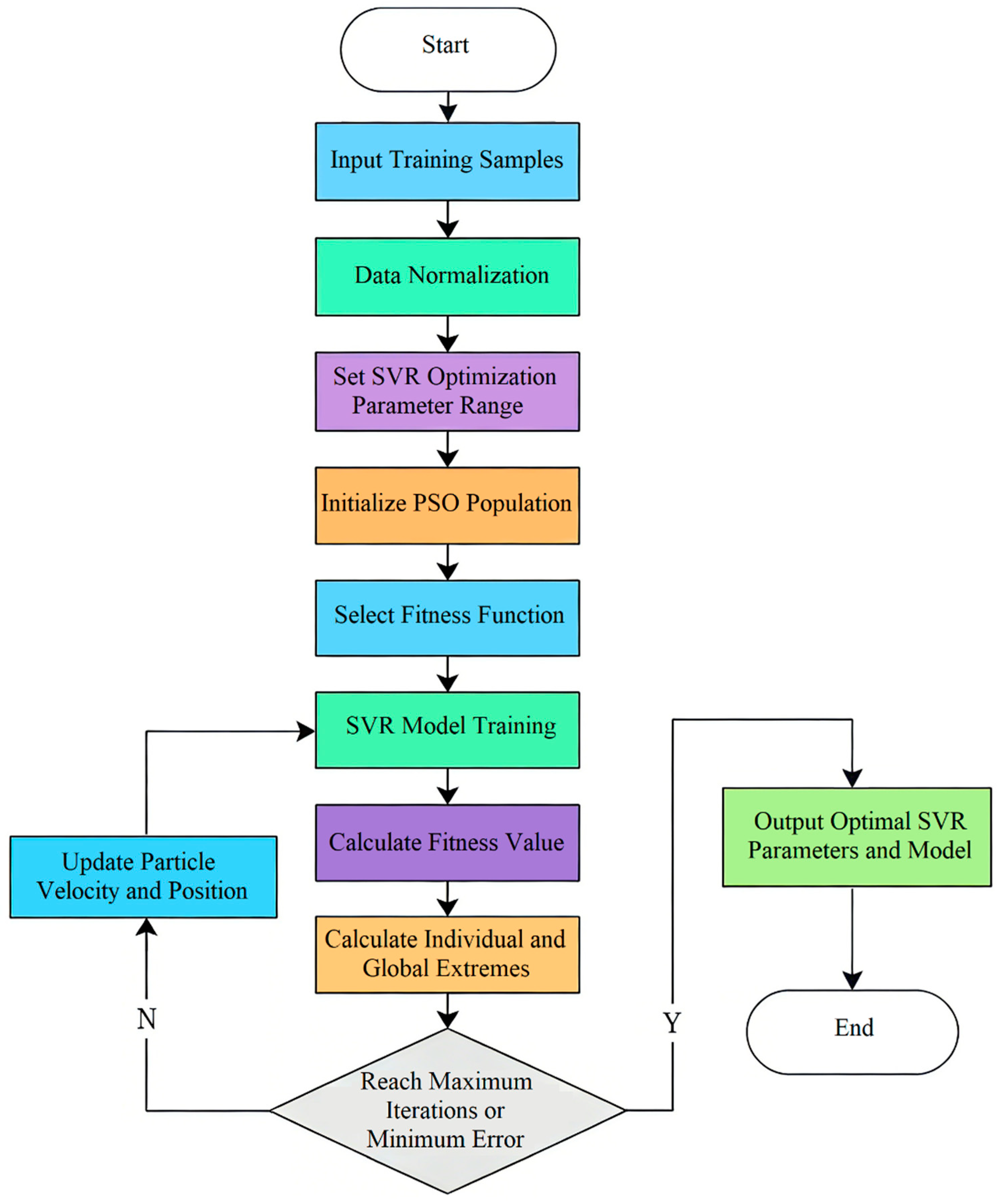

3.2. Construction and Optimization of PSO-SVR Model

3.2.1. SVR Model Construction

- is the RBF kernel function, is the kernel parameter that controls the influence range of the sample, and is the Euclidean distance between the input feature and the sample ;

- and are Lagrange multipliers, satisfying the constraint conditions , , and

- is the bias term, which adjusts the position of the regression hyperplane;

- The values of , , and are obtained by solving the quadratic programming problem under the constraint of the -insensitive loss function.

3.2.2. PSO Algorithm Parameter Optimization

- and are the velocity and position of the particle in the -th iteration, respectively, and each particle position corresponds to a combination of the SVR parameters ();

- and are the velocity and position of the particle in the -th iteration;

- is the inertia weight, which balances the global search ability and local convergence ability of the algorithm. In this study, a linear decreasing strategy is adopted: , , and decreases linearly with the increase in number of iteration;

- and are learning factors, which are set to 2 in this study to adjust the learning ability of the particle to its own optimal position and the global optimal position;

- and are random numbers that are uniformly distributed in the interval [0, 1], which increase the randomness of the search;

- is the optimal position (optimal parameter combination) found by the particle itself in the first iterations;

- is the optimal position (global optimal parameter combination) found by the entire particle swarm in the first iterations.

3.2.3. Algorithm Flow and Parameter Setting

3.3. Model Verification and Comparative Analysis

4. Failure Life Threshold Prediction Based on iForest

4.1. Construction of Anomaly Detection Model

- is the anomaly score of sample and is the number of samples used to construct the isolation tree;

- is the path length of sample in the isolation tree, which is defined as the number of edges passed from the root node of the tree to the leaf node where the sample is located. Abnormal samples are more likely to be isolated in the early stage of tree construction, so their path lengths are shorter;

- is the expected path length of all of the samples in the isolation tree, which is used to standardize the path length of a single sample. For samples of size , can be calculated through the harmonic number approximation;

- The value range of the anomaly score is [0, 1]. The closer is to 1, the higher the anomaly degree of the sample; the closer it is to 0, the more normal the sample is.

4.2. Threshold Prediction Results and Verification

4.2.1. Model Performance Evaluation

4.2.2. Determination and Verification of Failure Threshold

4.3. Application of the Combined Model

5. Conclusions and Prospects

5.1. Conclusions

- A comprehensive full-lifecycle dataset is constructed and the deterioration evolution laws are clarified. By designing an 8/20 μs impulse current accelerated deterioration experiment, 441 sets of valid data covering nine same-batch 07D241K ZnO varistors from initial state to complete failure are collected, effectively addressing the problem of incomplete dataset coverage in existing studies. The analysis of the experimental results reveals the intrinsic deterioration laws of the core parameters: varistor voltage () exhibits a three-stage characteristic of “slow increase–stabilization–rapid decrease”; nonlinear coefficient () attenuates by ~56% throughout the deterioration process; leakage current () remains stable in most stages but shows a “steep rise” near failure; parallel resistance () and parallel capacitance () change regularly with the evolution of the grain boundary layer defects ( first increases then decreases, first decreases then stabilizes and increases). Additionally, obvious individual differences in parameter changes among same-batch samples further confirm the necessity of multi-parameter fusion characterization.

- A high-precision remaining life prediction model based on PCA and PSO-SVR is established. To capture comprehensive deterioration information through complementary parameter responses, five core electrical parameters (, , , , ) are fused, with PCA dimensionality reduction applied to eliminate redundant information. The first principal component (PC1) with a variance contribution rate of 69.8% is selected as the model input, and its correlation coefficient with the deterioration degree reaches 0.96—significantly higher than that of any single parameter. The PSO algorithm is used to optimize the key parameters of SVR (penalty factor , allowable error , kernel parameter ), solving the problem that traditional algorithms are prone to falling into local optimal solutions. The test set performance of the model shows that the coefficient of determination () reaches 0.9726 and the mean squared error (MSE) is only 0.00142, which is significantly superior to traditional SVR and BP neural networks. The model exhibits excellent adaptability to small-sample scenarios, perfectly matching the practical challenge of time-consuming data collection for ZnO varistors.

- The iForest algorithm realizes accurate determination of the failure threshold. To solve the disconnection between remaining life prediction and failure threshold determination, the iForest anomaly detection model is constructed with the first two principal components (cumulative contribution rate ≥ 85%) as input features. The model achieves an AUC of 0.984 and an overall detection accuracy of 95.9%, demonstrating an excellent ability to distinguish between normal and abnormal samples. The average predicted failure threshold () deviates only 5% from the actual threshold (), which can accurately identify the failure critical point of ZnO varistors, providing a reliable basis for engineering early warning.

- The “PSO-SVR + iForest” combined model realizes collaborative optimization of prediction and early warning. With an overall accuracy of 99.89%, it integrates quantitative life prediction and qualitative threshold determination, solving the disconnection between prediction and early warning in existing research. Notably, the current study focuses on offline technical validation, with data collected via the standardized experimental platform (Figure 3). While the model achieves high-precision offline prediction, online application in actual power systems is ongoing. The core parameters required for the model are currently obtained through offline measurements and follow-up research on online parameter acquisition (via non-intrusive sensing technologies) has made initial progress, laying a solid foundation for engineering transformation.

5.2. Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AUC | Area Under the ROC Curve |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| IEC | International Electrotechnical Commission |

| iForest | Isolation Forest |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| MOV | Metal-Oxide Varistor |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| PSO | Particle Swarm Optimization |

| RBF | Radial Basis Function |

| SPD | Surge Protective Device |

| SVR | Support Vector Regression |

References

- Zacarias, T.G.; Sant’Ana, W.C. A Bibliometric and Comprehensive Review on Condition Monitoring of Metal Oxide Surge Arresters. Sensors 2024, 24, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEC 61643-12:2019; Low-Voltage Surge Protective Devices-Part 12: Surge Protective Devices Connected to Low-Voltage Power Systems-Selection and Application Principles. International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC): Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- Kim, S.-W.; Kim, N.-H.; Kil, G.-S. Assessment of MOV Deterioration Under Energized Conditions. Energies 2020, 13, 4018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, P.; Yin, Y.; Wang, L.; Guo, J.; Li, Z.; Zhou, K.; Zhu, G.; Xu, Y. Analysis of the Failure Mechanism of ZnO Varistors Influenced by High-Resistance Media Based on Multi-Field Coupling Simulation. High Volt. 2025, 10, 673–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjbar, B.; Darvishi, A.; Dashti, R.; Shaker, H.R. A Survey of Diagnostic and Condition Monitoring of Metal Oxide Surge Arrester in the Power Distribution Network. Energies 2022, 15, 8091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Huang, X.; Cao, T.; Shao, B.; Liu, Y. Research on Electrothermal Characteristics of Metal Oxide Varistors Based on Multi-Physical Fields. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2022, 16, 3636–3644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, T.; Wu, Y.; Liao, Z.; Liu, G.; Hu, S.; Han, Y.; Qu, L.; Li, L. Study on the Failure Causes and Improvement Measures of Arresters in 10 kV Distribution Transformer Areas. Energies 2025, 18, 4501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, J. Comprehensive Analysis of Transient Overvoltage Phenomena for Metal-Oxide Varistor Surge Arrester in LCC-HVDC Transmission System with Special Protection Scheme. Energies 2022, 15, 7034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, F.; Chen, W.; Wang, X.; Huang, T.; Cui, Z.; Nie, X. Transient Response Characteristics of Metal Oxide Arrester Under High-Altitude Electromagnetic Pulse. Energies 2022, 15, 3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Xing, H.; Li, P.; Li, C.; Lv, D.; Yang, S. An Experimental Study of the Failure Mode of ZnO Varistors Under Multiple Lightning Strokes. Electronics 2019, 8, 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Zhou, L.; Huang, L.; Fu, A.; Wang, D.; Guo, L.; Ma, Y. Electrothermal Characteristics of Zinc Oxide Varistors with Different Aging States After Multiple Lightning Strikes Based on Voronoi Network Finite Element Model. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2024, 229, 110096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiago, A.N.; Credson, d.S.; Estácio, T.W.N.; João, V.C. Short Duration Current Impulse Waveform Effects on the Degradation and Energy Absorption Capability of Zinc Oxide Varistors. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2023, 220, 109336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, G.; Zhou, Q.; Chen, R.; Shen, J.; Bian, X.; Zhang, Y. Research on Life Prediction of Surge Protective Device Based on Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 2025 13th Asia-Pacific International Conference on Lightning (APL), Bali, Indonesia, 17–20 June 2025; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habibollahi Najaf Abadi, H.; Modarres, M. Predicting System Degradation with a Guided Neural Network Approach. Sensors 2023, 23, 6346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, X.; Zou, H.; Wang, P.; Song, K.; Xie, G. High-Frequency Test of Electric Locomotive Arrester and Its PHM Design. Energies 2024, 17, 5523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Han, Y.; Dong, Y.; Liao, Z.; Zhang, P.; Huang, W.; Liu, G.; Zhang, J.; He, S. An Intelligent Online Diagnosis Method for Surge Arresters Status Based on ZnO Varistors Impulse Aging Test. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 74, 3540810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araujo, B.V.S.; Rodrigues, G.A.; de Oliveira, J.H.P.; Silva, A.M. Monitoring ZnO Surge Arresters Using Convolutional Neural Networks and Image Processing Techniques Combined with Signal Alignment. Measurement 2025, 248, 116889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, S.; Zhang, X.; Wang, G.; Zeng, J.; Ruan, Y. A Fault Identification Method for Metal Oxide Arresters Combining Suppression of Environmental Temperature and Humidity Interference with a Stacked Autoencoder. Energies 2023, 16, 8033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olesz, M.; Litzbarski, L.S.; Redlarski, G. Leakage Current Measurements of Surge Arresters. Energies 2023, 16, 6480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Li, C.; Zhou, Y.; Su, Q.; Wu, X. Leakage Current Sensing Method for DC Surge Arresters Based on TMR Sensor and Flux-Concentrating Coil Structure. IEEE Sens. J. 2025, 25, 39587–39599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walczak, K. Indirect Method of Moisture Degree Evaluation in Varistors by Means of Dielectric Spectroscopy. Energies 2025, 18, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaini, N.H.; Ab-Kadir, M.Z.A.; Rameli, N.H.; Ahmad, N.I.; Rahman, S.A.; Azizan, M.M. Evaluation of Surge Protective Devices (SPD) on Photovoltaic (PV) System Installations: Mitigating the Impact of Lightning Strikes. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE 5th International Conference in Power Engineering Applications (ICPEA), Bandar Baru Bangi, Malaysia, 14–15 July 2025; pp. 164–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Huang, L.; Wang, S.; Zhong, X.; Zheng, Z.; Wu, R.; Sun, Q. Effective Protection Distance of SPD in PV System Under Lightning Surge. IEEE J. Photovolt. 2024, 14, 637–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsovilis, T.E.; Hadjicostas, A.Y.; Staikos, E.T.; Peppas, G.D. An Experimental Methodology for Modeling Surge Protective Devices: An Application to DC SPDs for Electric Vehicle Charging Stations. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2024, 60, 1645–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsukamoto, N.; Ishii, M. Repetitive Impulse Withstand Performance of Metal–Oxide Varistors. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2017, 32, 1674–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, N.; Xie, Y.-Z.; Wu, Y.; Li, Z.; Canavero, F.G. An Equation-Based Dynamic Nonlinear Model of Metal-Oxide Arrester and Its SPICE Implementation. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2023, 70, 2919–2923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, F.; Chen, W.; Wang, X.; Nie, X.; Li, S. Response Characteristics of a ZnO Arrester Under Nanosecond Electromagnetic Pulse. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 154000–154009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Shen, J.; Xiao, Y.; Huang, X.; Cao, T. Withstanding Capability and Aging Mechanism of Metal-Oxide Varistors Under DC Temporary Overvoltage. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2024, 227, 109982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, R.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Wei, Y.; Zhou, M.; Li, C.; Fan, Y. Parallel Impulse Current Shunt Performance of Multiple MOVs for 500 kV Series Compensation. IEEE Trans. Power Deliv. 2023, 38, 2782–2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Xing, H.; Li, C.; Cai, R.; Lv, D. Micro-Degradation Characteristics and Mechanism of ZnO Varistors Under Multi-Pulse Lightning Strike. Energies 2020, 13, 2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 16927.1-2011; High-Voltage Test Techniques—Part 1: General Definitions and Test Requirements. Standardization Administration of China (SAC): Beijing, China, 2011.

- Muremi, L.; Bokoro, P. Degradation Classification of Low-Voltage Zinc Oxide Varistors Using K-NN Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE PES/IAS PowerAfrica, Johannesburg, South Africa, 7–11 October 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gałka, Ł. Optimized Deep Isolation Forest. Pattern Recognit. Lett. 2025, 197, 88–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, N.J.; Behera, R.K. EMD-Att-LSTM: A Data-Driven Strategy Combined with Deep Learning for Short-Term Load Forecasting. J. Mod. Power Syst. Clean Energy 2022, 10, 1229–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monemizadeh, V.; Kiani, K. Detecting Anomalies Using Rotated Isolation Forest. Data Min. Knowl. Discov. 2025, 39, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gałka, Ł.; Karczmarek, P. Deterministic Attribute Selection for Isolation Forest. Pattern Recognit. 2024, 151, 110395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Research Gaps | Solutions |

|---|---|

| Incomplete full-lifecycle dataset coverage | Conduct 8/20 μs impulse accelerated deterioration experiments, collecting 441 sets of data from 9 samples (initial state to complete failure) |

| Over-reliance on single-parameter characterization | Fusion of 5 core parameters () + principal component analysis (PCA) dimensionality reduction to eliminate redundancy |

| Disconnected remaining life prediction and failure threshold determination | Integrate Particle Swarm Optimization-Support Vector Regression (PSO-SVR) (quantitative prediction) and iForest (qualitative threshold) to establish a collaborative mechanism |

| Parameter | Mean | Standard Deviation | Minimum Value | Maximum Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (V) | 239.6 | 12.6 | 180.3 | 253.4 |

| 51.3 | 11.4 | 22.5 | 65.4 | |

| (μA) | 0.7 | 1.1 | 0.0 | 7.8 |

| (MΩ) | 14.77 | 1.02 | 12.89 | 17.70 |

| (pF) | 150.2 | 10.7 | 124.1 | 161.4 |

| Sample | A1 | A2 | A3 | A4 | A5 | A6 | A7 | A8 | A9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PC1 | 0.699 | 0.721 | 0.696 | 0.705 | 0.700 | 0.698 | 0.715 | 0.760 | 0.791 |

| PC1 + 2 | 0.923 | 0.907 | 0.923 | 0.916 | 0.861 | 0.860 | 0.911 | 0.913 | 0.901 |

| Dataset | MSE | MAE | RMSE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training set | 0.00096 | 0.01985 | 0.03108 | 0.9781 |

| Test set | 0.00142 | 0.02514 | 0.04026 | 0.9726 |

| Model | MSE | MAE | RMSE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional SVR | 0.00443 | 0.05663 | 0.06653 | 0.9186 |

| BP neural network | 0.00323 | 0.03792 | 0.05686 | 0.9496 |

| PSO-SVR | 0.00142 | 0.02514 | 0.04026 | 0.9726 |

| Category | Predicted Normal/Class 0 | Predicted Abnormal/Class 1 |

|---|---|---|

| Actually normal/Class 0 | 388 | 12 |

| Actually abnormal/Class 1 | 6 | 35 |

| Category | Number of Damaged Data Rows Diagnosed by the Model | Number of Actual Damaged Data Rows | Predicted Threshold | Actual Threshold |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A1 | 53, 56~59 | 55~59 | 0.442 | 0.458 |

| A9 | 58~63 | 58~63 | 0.431 | 0.462 |

| Average value | - | - | 0.437 | 0.460 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Zhu, Z.; Xiao, H.; Xu, Z.; Yang, J.; Huang, Z. Full-Lifecycle Deterioration Characteristics and Remaining Life Prediction of ZnO Varistors Based on PSO-SVR and iForest. Energies 2026, 19, 367. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020367

Zhu Z, Xiao H, Xu Z, Yang J, Huang Z. Full-Lifecycle Deterioration Characteristics and Remaining Life Prediction of ZnO Varistors Based on PSO-SVR and iForest. Energies. 2026; 19(2):367. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020367

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhu, Zhiheng, Hongyang Xiao, Zhengwang Xu, Jixin Yang, and Zhou Huang. 2026. "Full-Lifecycle Deterioration Characteristics and Remaining Life Prediction of ZnO Varistors Based on PSO-SVR and iForest" Energies 19, no. 2: 367. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020367

APA StyleZhu, Z., Xiao, H., Xu, Z., Yang, J., & Huang, Z. (2026). Full-Lifecycle Deterioration Characteristics and Remaining Life Prediction of ZnO Varistors Based on PSO-SVR and iForest. Energies, 19(2), 367. https://doi.org/10.3390/en19020367