Abstract

The increasing penetration of inverter-based renewable generation has reduced rotational inertia in power systems worldwide, causing steeper frequency drops after severe contingencies and increasing the risk of load shedding. In the Honduran context, this study evaluates the dynamic response of the National Interconnected System (NIS) operating in island mode through detailed DIgSILENT PowerFactory simulations, explicitly incorporating the national Under-Frequency Load Shedding (UFLS) scheme. Five disturbance scenarios were analyzed, including generation losses of 100 MW, 200 MW, and 262 MW, to assess the frequency support provided by Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESSs) and Flywheel Energy Storage Systems (FESSs). Results show that, in the base case, frequency decreased to 55.3 Hz during a 200 MW loss, confirming the system’s high vulnerability. The integration of a 75 MW BESS improved frequency stability to 58.74 Hz, preventing UFLS activation, while a 320 MW equivalent FESS provided only short-term inertial support with limited effectiveness. Quantitatively, the BESS reduced the minimum frequency, delayed UFLS activation by approximately 3.5 s, and provided sustained support, whereas the FESS contributed mainly during the first 5 s of the disturbance. In the most severe contingency (262 MW generation loss), the combined operation of BESS and FESS prevented total system collapse, improving the frequency nadir to 58.6 Hz. These results confirm that BESS provides more robust and sustained frequency support than FESS under the analyzed conditions, highlighting its effectiveness for improving system stability in low-inertia networks such as Honduras. The findings offer useful insights for future studies on storage integration and frequency regulation strategies.

1. Introduction

1.1. General Considerations

Frequency stability is a fundamental indicator of power system security, reflecting the instantaneous balance between generation and demand. The global energy transition has led to a significant increase in inverter-based renewable generation, causing a substantial reduction in rotational inertia. This reduction results in a lower minimum frequency during severe contingencies, shortens the time window for protection systems to act, and increases the risk of under-frequency load shedding (UFLS) or even system collapse. In low-inertia networks, solutions providing rapid and coordinated support are a research priority. Among them, Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS) and Flywheel Energy Storage Systems (FESS) have emerged as promising technologies, offering synthetic inertia, fast frequency regulation, and active power injection during the critical first seconds after a disturbance.

The Honduran National Interconnected System (NIS) typically operates interconnected with the Central American Electrical System (SER), which provides frequency support and enhances stability. However, when the NIS runs in island mode due to maintenance or contingencies, frequency becomes highly vulnerable to large disturbances. This situation is aggravated by the increasing penetration of photovoltaic generation, representing more than 25% of installed capacity and contributing no rotational inertia because of its inverter-based interface [1]. Under these conditions, Honduras relies mainly on the spinning reserve of the Francisco Morazán hydroelectric plant (El Cajón) and the UFLS scheme. This approach involves high operational costs and frequent disconnections. Therefore, there is a pressing need to explore technological and planning solutions, including generation expansion strategies, microgrid development, and improved response under fault or contingency conditions, to reduce dependence on UFLS and strengthen overall system resilience [2,3,4,5,6].

1.2. State of the Art

This section presents the state of the art on energy storage technologies applied to power systems, with emphasis on their role in frequency regulation and dynamic support. Although it is not structured as a formal systematic review, it provides a focused and coherent synthesis of the most relevant studies and recent advances directly related to the objectives of this work. The discussion highlights key trends, comparative analyses between different storage technologies, and their reported performance under various operational contexts.

In recent years, there has been growing interest in energy storage technologies for power systems, with emphasis on their role in frequency regulation. Among these, flywheel energy storage systems (FESS) and battery energy storage systems (BESS) have attracted attention due to their ability to provide fast dynamic response and sustained energy support. To assess research activity in this field, a bibliometric analysis was conducted using the SCOPUS database with the search terms “power system” AND “flywheel energy storage” AND “battery”. A total of 179 publications were identified, including journal articles, conference papers, and book chapters.

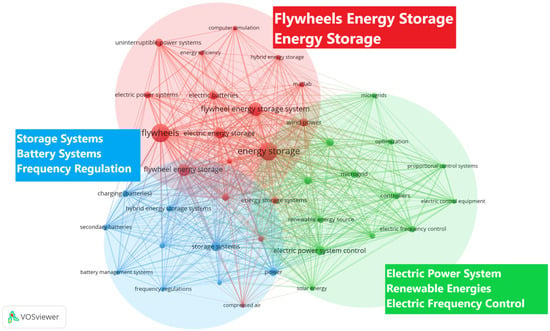

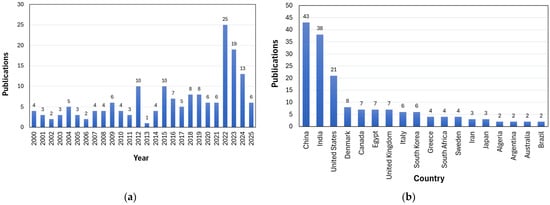

Figure 1 shows the thematic keyword map generated with VOSviewer software version 1.6.20 [7]. Three main clusters were identified: (i) flywheel energy storage and efficiency, linked to hybrid systems and electric power applications; (ii) battery storage and frequency regulation, associated with charging, management, and control strategies; and (iii) power systems and frequency control, connected to renewable integration, microgrids, and optimization methods. These clusters confirm that studies in the field focus on the complementary roles of BESS and FESS in frequency stability. Figure 2a illustrates the evolution of publications between 2000 and 2024. During the early years, research output was limited, with fewer than ten studies per year, then increased gradually after 2016, reaching a maximum in 2022 with more than 25 publications. Although there was a decline in 2023 and 2024, the number of studies remains higher than in the initial period, confirming the growing importance of hybrid energy storage for system stability. Figure 2b shows the distribution of publications by country. China, India, and the United States lead research, followed by Denmark, Canada, Egypt, the United Kingdom, and Italy. In contrast, Latin America is underrepresented, with only Argentina and Brazil reporting two publications each, highlighting the lack of regional contributions.

Figure 1.

Thematic keyword map related to Flywheels in power systems.

Figure 2.

Publications related to Flywheels and battery storage systems: (a) Publications by year and (b) Publications by country.

The increasing penetration of intermittent renewable sources such as solar and wind has reduced system inertia, thereby increasing vulnerability to generation or load contingencies. In this context, energy storage systems (ESS), particularly battery energy storage systems (BESS) and flywheel energy storage systems (FESS) have emerged as key technologies for providing primary frequency regulation (PFR/PCR) and other ancillary services. Early studies such as [8] highlighted the suitability of fast-response ESS (FESS and BESS) compared to conventional technologies, identifying their strategic role in renewable-dominated systems. More recent reviews [9,10] confirmed that the most promising ESS for frequency regulation in modern grids are BESS, FESS, supercapacitors, and SMES, although cost and proper sizing remain open challenges.

In relation to control and operation strategies, several approaches have been proposed to avoid state-of-charge (SOC) saturation and ensure resource availability. B-1 and B-3 introduced variable droop control as an alternative to balance system dynamics and stored energy. The paper in [11] emphasized the importance of scheduling transactions in the German market, where SOC management is partially delegated to intraday transactions. More recently, Refs. [11,12] have explored SOC-dependent droop and adaptive control schemes to enhance BESS availability during PFR. In parallel, Ref. [13] proposed signal decomposition (VMD), assigning fast components to FESS (high power, low energy) and slower components to BESS (sustained energy), thereby reducing degradation costs and improving joint performance.

Concerning technology comparison, multiple works have shown that FESS excels in high power density, sub-second response time, and virtually unlimited cycle life [14,15]. These characteristics make it suitable for damping fast fluctuations, although its short autonomy (seconds to minutes) remains a limitation. In contrast, BESS provides sustained energy, a critical condition to prevent load shedding in weak or islanded grids. This complementarity has been reinforced in hybrid schemes: Refs. [11,16] show that a combined BESS-FESS design can triple the lifetime of batteries and improve economic performance. Authors in [12] confirm this synergy in wind farms, while Refs. [13,17] propose coordinated control and SOC partitioning strategies to optimize hybrid operation.

The literature has also widely discussed economic and aging aspects. Paper in [8] established that revenues from regulation often exceed those from energy arbitrage, particularly for FESS, whose net-zero energy profile is advantageous in regulation markets. The authors in [11] concluded that BESS design and sizing largely determine degradation, more so than fine-tuned control policies. At the same time, Refs. [12,16] highlighted that combining technologies mitigates battery degradation by limiting deep cycles and high power peaks.

Finally, recent reviews [10] stress the importance of applying these insights to low-inertia, weak grids, where the combined effect of fast power support and sustained energy is most critical. However, most studies focus on European, North American, or Asian contexts, with little evidence from Latin American semi-radial systems with islanding operation. This gap represents the opportunity addressed in our research. Table 1 presents a summary of literature discussions related to BESS and FESS in frequency regulation.

Table 1.

Summary of Literature Discussions in Relation to BESS and FESS Roles in Frequency Regulation.

1.3. Motivation and Contributions

The Honduran NIS faces growing stability challenges due to high renewable penetration and its semi-radial topology. Under islanded operation, frequency exhibits abrupt drops that frequently trigger the Under-Frequency Load Shedding Scheme (UFLS/EDCBF), with negative consequences for reliability and social costs. International literature demonstrates that BESS and FESS can support frequency following disturbances, although with distinct roles: FESS is effective at damping rapid fluctuations, while BESS is decisive in providing sustained energy. However, there is a lack of applied evidence in weak Latin American grids, where the combination of fast response and sustained support can determine whether a system remains stable or collapses under severe contingencies.

This research aims to address this gap by evaluating the expected improvement in frequency stability of the Honduran NIS once the BESS installation at the Amarateca substation is completed (scheduled for May 2026). Additionally, for research purposes, the study explores how the inclusion of a Flywheel Energy Storage System (FESS) could further enhance system performance at the same substation. A hybrid configuration, in which flywheels provide initial dynamic stabilization and batteries sustain frequency regulation until hydraulic turbines restore equilibrium, emerges as an effective approach to mitigate transient instability. This approach is particularly relevant for the Honduran NIS when operating in isolation, where rapid dynamic response is essential to prevent UFLS activation, minimize frequency dips, and ensure a continuous and reliable power supply. The Amarateca substation was selected because it is the newest 230 kV facility in the system, offering adequate space for both BESS and FESS installations and providing additional voltage support to the 230 kV transmission network.

Accordingly, this study evaluates representative scenarios in the Honduran NIS, providing technical insights for ESS control and sizing in similar weak grids. The main goals are presented below:

- Compare the performance of BESS and FESS in primary frequency regulation under critical scenarios in the NIS (islanded operation), considering metrics such as nadir, minimum Frequency, and UFLS/EDCBF activation stages.

- Analyze advanced control policies, including synthetic inertia and deadbands for BESS, to reduce unnecessary activations and enhance stability.

- Explore BESS-FESS coordination strategies based on signal decomposition and SOC partitioning, as the foundation for cost-effective hybrid schemes.

- Propose operational and sizing guidelines for ESS tailored to weak Central American grids, aimed at strengthening operational security and resilience under renewable-driven contingencies.

2. Problem Formulation and Description

2.1. Honduras Power Electrical System

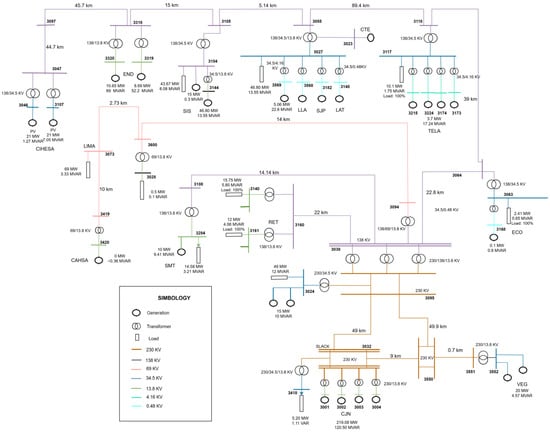

This research relied on an UNAH dataset based on the Honduran power system network. The information consisted of Excel spreadsheets containing technical specifications of buses, transmission lines, transformers, loads, and generating units, along with a general single-line diagram of the national interconnected grid, as presented in Figure 3. The overall system can be summarized as follows:

Figure 3.

Single-line diagram of the modeled Honduran power grid.

- Generation: 156 buses, of which 114 are operational with an installed capacity of 2033.79 MW, and 42 are non-operational totaling 8.00 MW.

- Transmission lines: 138 lines in service and 3 out of service.

- Two-winding transformers: 184 active and 10 inactive units and three-winding transformers: 49 active units, none out of service.

- Load: 87 active buses with a demand of 2005 MW, and 15 inactive buses totaling 161 MW.

The national grid of Honduras is mainly radial, a configuration that increases its exposure to failures. However, the single-line diagram reveals that certain central zones of the country present partial meshed interconnections. This semi-radial topology integrates unidirectional transmission corridors with localized backup loops, which enhances operational flexibility in key areas but preserves structural weaknesses in peripheral regions.

2.2. Study Region of the Honduran Grid for Energy Storage with Flywheels

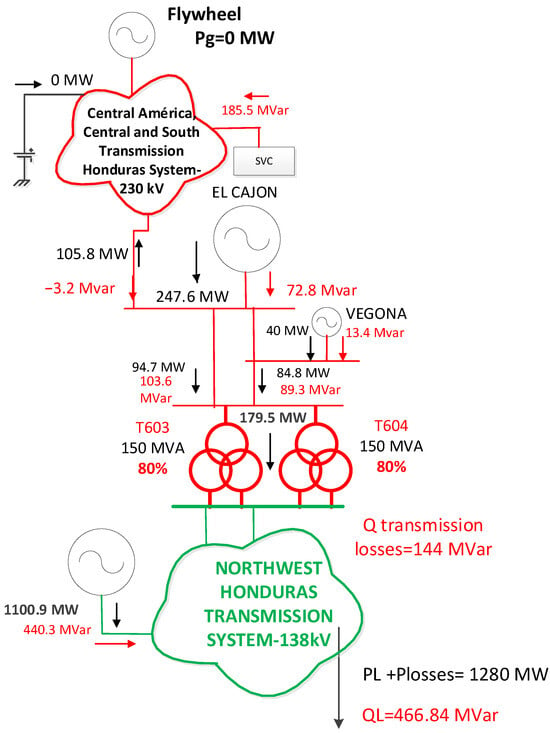

Figure 4 illustrates the main 230 kV transmission network in Honduras. Within this system, the ‘El Cajón’ hydroelectric plant is highlighted as the country’s most significant generation facility, both in terms of installed capacity and its critical role in the operation of the national power grid. This plant serves a strategic function as the interconnection point between the central–southern network, operating at 230 kV, and the northwestern network, which operates at 138 kV. The interconnection between these two sections is enabled through power transformers located at El Cajón, which facilitate energy transfer across different voltage levels and ensure the operational integration of the system.

Figure 4.

Modeled diagram of the 230 kV main transmission network in Honduras and proposed location of compensation and storage devices at the Amarateca substation.

In the central–southern network, the Amarateca substation is identified as the reference point for the present study. For modeling purposes, this substation has been selected as the integration node for compensation and storage devices. Specifically, the model incorporates a Static Var Compensator (SVC), a 75 MW battery energy storage system (BESS), and a flywheel energy storage system (FESS). It should be emphasized that these devices are not part of the existing infrastructure at Amarateca; rather, they represent a conceptual configuration used within the simulation framework. The aim is to analyze the dynamic performance of the system and its ability to withstand instability events under different operating conditions.

2.3. Simulation Tools

In this study, DIgSILENT PowerFactory version 13.1 (series 13.1) was employed to model and simulate the dynamic behavior of the Honduran National Interconnected System (NIS) under severe contingencies. PowerFactory is a widely recognized platform for power system analysis, extensively applied in studies of generation, transmission, and industrial networks. Its proven reliability, flexible modeling capabilities, and advanced simulation algorithms have established it as a benchmark tool in both academia and industry.

The selected version includes all essential modules for steady-state and dynamic analysis, such as load flow, short-circuit, and quasi-dynamic simulations, as well as extended libraries for modeling batteries (ElmBattery), photovoltaic systems (ElmPvsys), direct current machines (ElmDcm), and series RLC filters (ElmSfilt). The software also provides a scripting interface that enables automation and large-scale parametric studies, facilitating iterative simulations for different contingency cases.

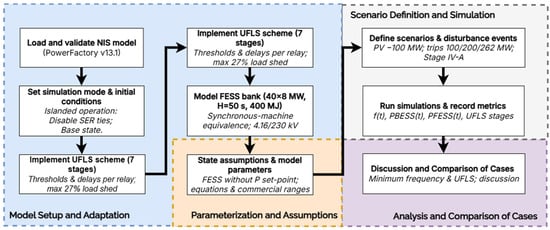

The modeling and simulation workflow followed in this study is summarized in Figure 5. The procedure was designed to ensure consistency, reproducibility, and clarity in the representation of both the BESS and FESS dynamics.

Figure 5.

Methodological workflow for the modeling, simulation, and analysis of the Honduran National Interconnected System (NIS) using DIgSILENT PowerFactory.

- Load and validate the NIS model (PowerFactory v13.1): The national database was imported and verified for topological integrity, including bus, line, transformer, and load data.

- Set simulation mode and initial conditions: The system was initialized under a balanced pre-fault condition. To emulate islanded operation, the Sistema Eléctrico Regional (SER), the Central American Regional Electricity System interconnecting Honduras with neighboring countries, was disabled by opening the interties. This configuration isolates the Honduran grid and allows the assessment of its autonomous frequency stability.

- Implement the Under-Frequency Load Shedding (UFLS) scheme: The seven-stage national UFLS configuration was modeled using multiple frequency relays, each parameterized with activation thresholds and delay times. The scheme progressively disconnects up to 27% of the total load during critical frequency declines, reproducing the staged behavior defined by the National Dispatch Center (CND) and summarized in Table 2.

Table 2. Under-Frequency Load Shedding Scheme.

Table 2. Under-Frequency Load Shedding Scheme. - Model the 75 MW Battery Energy Storage System (BESS): The BESS model incorporated a dedicated frequency-control loop with a ±0.5 Hz deadband and proportional gain (Kfrecbat = 50), enabling dynamic power injection or absorption when frequency deviations exceed the tolerance range.

- Model the Flywheel Energy Storage System (FESS): A synchronous machine-based representation was used to emulate the flywheel’s inertial response. Each 8 MW unit (H = 50 s, 400 MJ) was connected at 4.16 kV and coupled via a step-up transformer to the 230 kV bus at the Amarateca substation. A bank of 40 such units was modeled to assess high-inertia scenarios.

- Define scenarios and disturbance events: The simulations considered generation loss events of 100 MW, 200 MW, and 262 MW, along with a 100 MW photovoltaic power variation, representing typical and extreme operational conditions of the Honduran grid.

- Run simulations and record performance metrics: Key outputs like system frequency f(t), active power responses PBESS(t) and PFESS(t), and UFLS activation stages were recorded for each scenario.

- Compare results and compile summary metrics: The minimum frequency (nadir), UFLS activation timing, and overall recovery trends were analyzed and summarized in Table 3 for comparative evaluation among cases.

Table 3. Minimum Frequency reached in the analyzed cases for the worst contingency.

Table 3. Minimum Frequency reached in the analyzed cases for the worst contingency.

This methodology provides a systematic framework for evaluating the performance of BESS and FESS in mitigating frequency deviations during islanded operation. The approach ensures consistency between model configuration, control implementation, and metric assessment, offering practical insights applicable to similar low-inertia grids across the Central American region.

3. Theoretical Foundation

The electrical system frequency is a direct indicator of the balance between generation and demand. Under normal operating conditions, synchronous generators rotate at constant speed, maintaining nominal frequency. However, sudden disturbances, such as unexpected generation loss or abrupt load increases produce immediate frequency deviations that may jeopardize system stability if not corrected promptly.

In Honduras, the National Interconnected System (SIN) often operates in synchrony with the Regional Electricity System (SER), whose higher inertia provides additional stability. When operating in island mode, however, the SIN exhibits limited inertia and heightened vulnerability, particularly due to the high penetration of variable renewable energy. More than 25% of the installed capacity derives from solar and wind power, which, being inverter-based resources, do not contribute to rotational inertia.

To mitigate blackout risks, Honduras relies on an Under-Frequency Load Shedding (UFLS) scheme, which operates in multiple stages once critical thresholds are reached. While effective, frequent activation of UFLS leads to supply interruptions, economic losses, and increased operational stress on hydropower plants such as El Cajón, the country’s main spinning reserve.

In this context, advanced storage technologies such as Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS) and Flywheel Energy Storage Systems (FESS) provide complementary solutions. BESS can respond within seconds, injecting or absorbing power to regulate frequency and reduce minimum Frequency. Notably, the 75 MW BESS is in the installation process at the Amarateca substation, which will be the first large-scale system in Central America, and offers synthetic inertia and voltage support. The cost of this system is approximately 52 MUSD. Flywheels, by contrast, store kinetic energy and release it almost instantaneously during frequency drops, delivering short bursts of active power in the first seconds following a disturbance. Although their energy capacity is limited, this immediate response bridges the critical gap until batteries or hydro reserves are fully activated.

4. Methodology for Analysis and Modeling

4.1. Integration of the Under-Frequency Load Shedding Scheme

To simulate the system’s dynamic response to low-frequency events, the Under-Frequency Load Shedding (UFLS) scheme was implemented in the Honduran Power System database using DIgSILENT PowerFactory. This scheme operates by progressively disconnecting loads to restore system frequency following a major generation loss. The disconnections occur in successive stages, each activated according to the severity of the frequency deviation. In the most critical scenario, if all stages of the scheme are triggered, up to 27% of the total system load is disconnected (Table 2).

A frequency relay model was configured with multiple trip thresholds associated with different load groups, replicating the staged operation of the national UFLS scheme. This implementation aims to evaluate whether storage resources, specifically battery energy storage systems (BESS) and flywheel energy storage systems (FESS), can arrest the frequency decline before any disconnections take place. Each relay was parameterized with two key settings: the activation frequency threshold and the corresponding delay time.

The UFLS scheme consists of seven stages, five of which are regional. This means that all interconnected countries (Mexico and Central America) cooperate by shedding load during regional low-frequency events. In the case of a more severe contingency, the interconnection lines between countries are opened, leaving each nation operating in islanded mode and relying on the final UFLS stages for frequency recovery, as shown in Table 2.

This scheme, established by the National Dispatch Center (CND), uses a standardized national nomenclature to identify distribution circuits. In this system, the first three letters indicate the substation to which the circuit belongs, the letter “L” that follows designates a transmission or distribution circuit, the next number represents the voltage level, and the last two digits identify the specific line. For instance, BER L207 refers to line 07 of the Bermejo substation at 13.8 kV (voltage level 2), whereas AGC L628 designates line 28 of the Aguacaliente substation at 230 kV (voltage level 6).

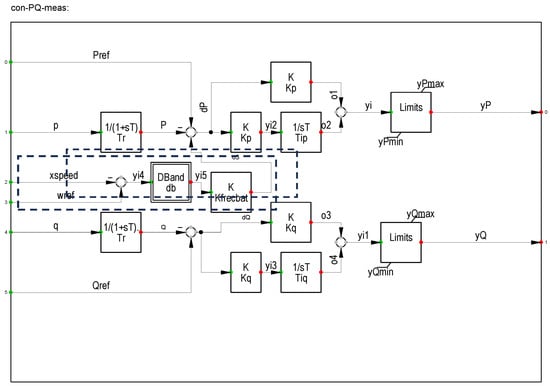

4.2. Integration of Frequency Control Loop for the 75 MW Battery

The battery model in DIgSILENT PowerFactory already includes a generic scheme for active and reactive power control. However, for this study, an enhancement was introduced to ensure a dynamic battery response during frequency events. The additional logic, directly embedded into the existing control structure (see Figure 6), is organized in three stages. First, the speed (w) is measured in p.u. through the variable xspeed (which is the variable that represents the speed in Figure 6) and compared against the nominal reference (wref = 1 pu). The deviation passes through a dead-band block of ±0.5 Hz, preventing unnecessary responses to minor fluctuations. If the deviation exceeds this band, the signal is amplified by a proportional gain (Kfrecbat = 50). This output is then fed into the active power controller, enabling the battery to inject or absorb power only when justified by significant frequency drops.

Figure 6.

Modified control scheme for active battery power injection in the event of frequency drops.

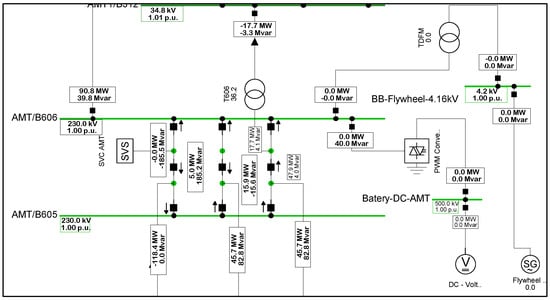

4.3. Modeling of the Flywheel in DIgSILENT PowerFactory

A synchronous machine model was selected to represent the flywheel energy storage system (FESS), given that its rotating masses inherently provide an inertial response. A two-pole unit was configured to operate at 3600 rpm, with an apparent power rating of 10 MVA and a power factor of 0.8, corresponding to an active power capacity of 8 MW. The inertia constant (H) was adjusted to a high value of 50 s, resulting in a device capable of storing approximately 400 MJ of kinetic energy. The 40 flywheel bank was connected to a 4.16 kV bus and coupled to the system through a step-up transformer, which raised the voltage to 230 kV. This configuration enabled its interconnection to the same bus at the Amarateca substation, where the battery storage system is located (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Connection to the interconnected power system in Amarateca of the 40-flywheel bank modeled using synchronous machines.

For this modeling approach, the active power output of the synchronous machine was set to zero, ensuring that its sole interaction with the system originated from the inertial response to frequency variations. This configuration adequately reproduces the behavior of a real flywheel during the initial seconds of energy discharge. To estimate the mass of the rotating components required to achieve the target inertia constant (H = 50 s), a classical formulation commonly applied in the design of synchronous electrical machines was employed.

This choice reflects the methodological adaptation of a synchronous machine model that represents a commercial flywheel unit of two poles with the technical specifications as presented below. The general expression used to calculate the inertia constant H for rotational systems (), specifically adapted for synchronous machines, is given by (1), obtained from [21]:

where WR2 represents the product of the rotor weight (0, in pounds) and the square of the average radius (R, in feet) of 3.28 feets, RPM denotes the flywheel mechanical rotor speed in revolutions per minute (3600 r.p.m.), and MVA rating corresponds to the machine’s rated apparent power (10 MVA each flywheel, with a power factor of 0.8). After performing the necessary unit conversions and rearranging the expression in (1) to solve for W (weight in pounds of the rotational parts of the flywheel), the resulting rotor weight in pounds is obtained and converted to tons as follows in (2):

With the estimated weight of the rotating parts of the selected model, the next step is to calculate the amount of kinetic energy that can be stored. The kinetic energy in a rotational system can be determined from the inertia constant (H), where H is expressed in seconds, E denotes the stored kinetic energy in megajoules (MJ), and P represents the machine’s active power in megawatts (MW), as presented in (3):

The calculated kinetic energy represents the available contribution of the model during a sudden generation loss and enables the assessment of its response capability in the first seconds of a contingency. To validate the consistency of the model against commercial flywheel technologies, technical specifications were collected to summarize their most relevant characteristics. The simulated model, represented by a synchronous machine rated at 8 MW operating at 3600 rpm with an inertia constant of 50 s and storing 400 MJ, falls within the commercial ranges of 2–5 MW and 10–15 MW units. Flywheels in the 2–5 MW range typically exhibit inertia constants between 30 and 80 s, rotational speeds of 1500–3000 rpm, and rotor masses of 15–30 t; units in the 10–15 MW range generally operate at 750–1500 rpm, with inertia constants of 50–120 s and rotor masses of 30–60 t. While the proposed model presents a comparable inertia constant, its rotor mass (7.06 t) is considerably lower. Furthermore, it surpasses commercial devices in stored kinetic energy (400 MJ compared to 80–150 MJ), reflecting the methodological configuration aimed at representing a high-inertia scenario. In a parallel arrangement of 40 units, the cumulative storage capacity would reach 16,000 MJ.

5. Dynamics, Simulations, and Results

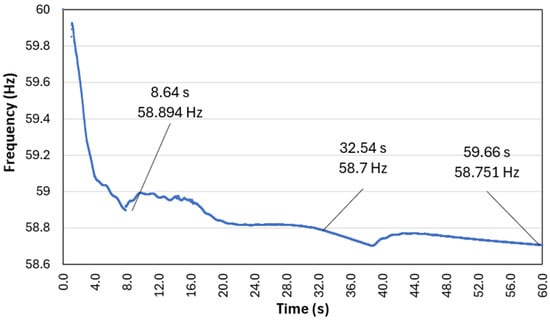

5.1. Case 1: 100 MW Photovoltaic Variations

In the first scenario, the National Interconnected System (NIS) operates in islanded mode without storage technologies, relying solely on El Cajón’s spinning reserve and the Under-Frequency Load Shedding (UFLS) scheme. A sudden loss of 100 MW was simulated, producing a frequency drop that reached a minimum of 58.700 Hz (Figure 8). Despite UFLS activation, which triggered the penultimate stage, and the response of El Cajón, the frequency only recovered to 58.751 Hz. This behavior highlights that the current system capacity is insufficient to restore secure operating margins under contingencies of this magnitude.

Figure 8.

Frequency response of the NIS under a 100 MW loss with only El Cajón and UFLS regulation.

5.2. Case 2: 200 MW Generation Loss

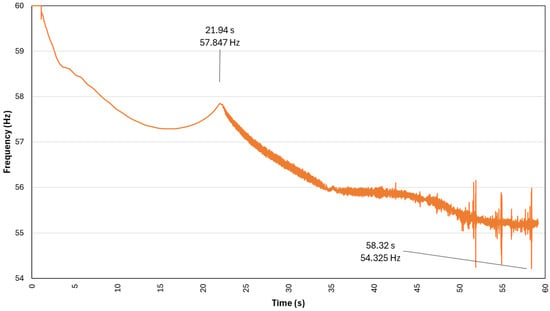

When simulating a 200 MW loss without additional support technologies, the system experienced a critical frequency decline, reaching a minimum of 54.325 Hz without signs of recovery. Neither UFLS nor El Cajón’s spinning reserve was able to contain the event, leading to a complete system collapse caused by massive generator disconnections triggered by sustained under-frequency protection, as presented in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Frequency response of the NIS in Case 2.

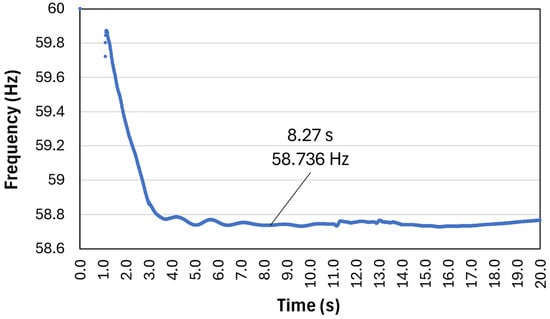

5.3. Case 3: 200 MW Generation Loss with Battery Support

With the integration of the 75 MW Battery Energy Storage System (BESS) under a 200 MW generation loss, the system exhibited a significant improvement. The minimum frequency recorded was 58.736 Hz at 8.270 s (Figure 10), thus avoiding the 58.5 Hz threshold that would trigger UFLS protection. The battery delivered a maximum output of 51.37 MW at 16.81 s, demonstrating a fast and effective response. This intervention stabilized the system frequency without collapse. Moreover, due to the implemented control strategy, the battery sustained its discharge throughout the contingency, providing continuous support.

Figure 10.

Frequency response of the SIN with the integration of a 75 MW BESS during a 200 MW generation loss.

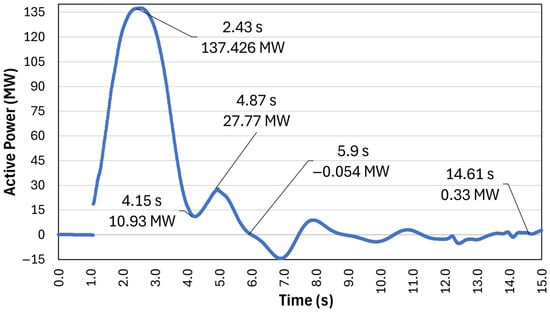

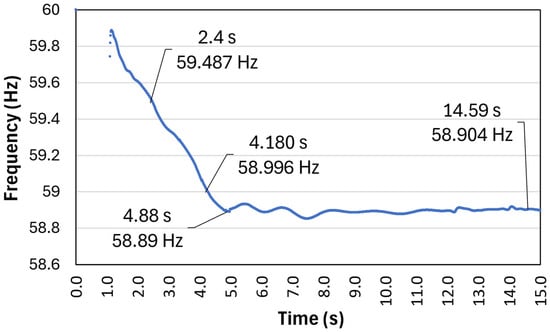

5.4. Case 4: 200 MW Generation Loss with Battery and Flywheel Support

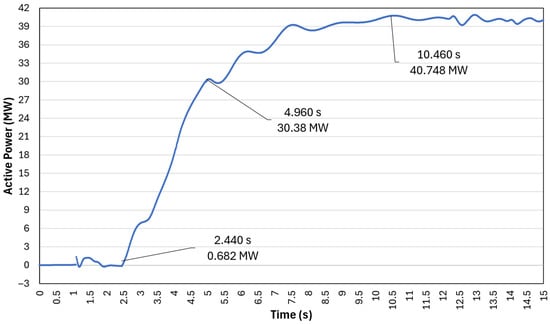

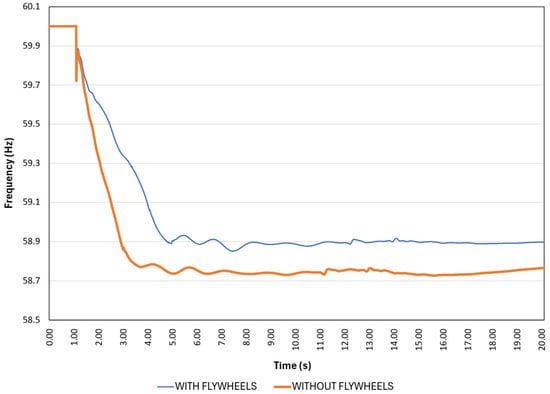

With the simultaneous integration of the 75 MW BESS and a bank of 40 flywheels, the NIS faced a 200 MW contingency with a faster response. The flywheels delivered a peak output of 137.03 MW at 2.55 s, although their contribution was short-lived (Figure 11). The minimum system frequency was 58.890 Hz, only 0.116 Hz higher than the case without flywheels (58.736 Hz), while the final stabilized value was 58.904 Hz, as presented in Figure 12. Although the improvement was minor, the flywheels alleviated the battery, reducing its maximum output from 51.37 MW to 40.82 MW (Figure 13). Nevertheless, UFLS stages were still activated, and the technical benefit remained limited.

Figure 11.

Total active power delivered by the bank of 40 flywheels modeled with synchronous machines for a deficit of 200 MW.

Figure 12.

Frequency response of the SIN with 75 MW BESS and 40 flywheels (320 MW equivalent) during a 200 MW generation loss.

Figure 13.

Active power delivered by the 75 MW BESS during a 200 MW generation loss with the participation of 40 flywheels.

As shown in Figure 11, the flywheel bank reached its maximum output of 137.426 MW within only 2.43 s. At the same instant, the BESS had barely begun discharging, providing just 0.682 MW (see Figure 13), while system frequency remained at 59.487 Hz (see Figure 12), before UFLS activation. However, the flywheels’ initial burst was ineffective: within less than seconds two (2 s) and three (3 s) (see Figure 11), the FESS output decreased sharply (see Figure 11), being almost depleted before frequency reached its minimum at 4.88 s (see Figure 12). By 4.15 s, flywheels were providing only 10.93 MW (see Figure 11), while the BESS output had risen to 30.38 MW (see Figure 13) and the frequency had dropped to 58.996 Hz (see Figure 11). After 5.90 s, the flywheels contributed almost no power (0.054 MW) (see Figure 11). In contrast, the BESS continued ramping up, and by 10 s was supplying 40.748 MW in a sustained manner (see Figure 13), effectively stabilizing the frequency at around 58.904 Hz (see Figure 12). This behavior illustrates the fundamental difference between the two technologies: while flywheels provide a brief but intense initial impulse, the battery offers slower, sustained support that is critical for system recovery.

As shown in Figure 14, the scenario without flywheels exhibits a sharp frequency decline to approximately 58.73 Hz, with no clear recovery. With flywheels integrated, the minimum frequency rises slightly to 58.85 Hz, and the curve profile shows a minor attenuation of the initial slope. However, this improvement is negligible considering the installed flywheel capacity (320 MW equivalent) and the high inertia (2000 s). The UFLS stages were still triggered, and no substantial enhancement in overall system stabilization was observed. Consequently, the contribution of flywheels proved limited and hardly perceptible in terms of dynamic response. Table 3 summarizes the minimum frequency reached for each analyzed case.

Figure 14.

Comparison of SIN frequency response with and without flywheel support during a 200 MW generation loss.

5.5. Case 5: 262 MW Generation Loss with Only BESS

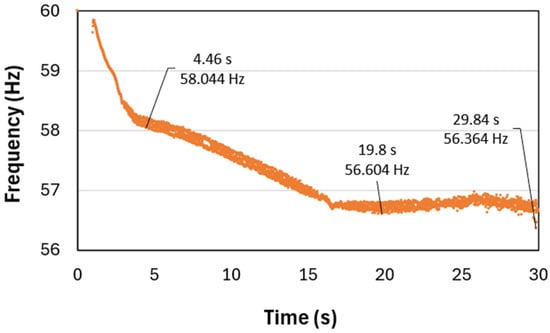

In this scenario, 262 MW of photovoltaic generation are simultaneously disconnected after the National Interconnected System (NIS) becomes isolated, corresponding to the activation of Stage IV-A of the Under-Frequency Load Shedding (UFLS) scheme. Figure 15 illustrates the system frequency response considering only the BESS support. Under this condition, the system collapses due to under-frequency, reaching 56.6 Hz after 20 s, with all UFLS stages fully activated (see Table 2).

Figure 15.

Frequency response with only BESS support (262 MW outage generation).

These results indicate that, when operating exclusively with the BESS, the NIS can withstand generation losses up to approximately 200 MW, beyond which frequency stability cannot be maintained and the system enters a full load-shedding condition.

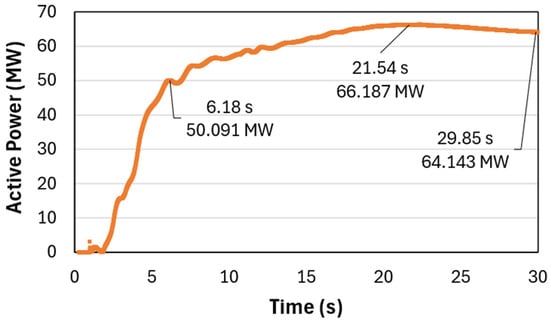

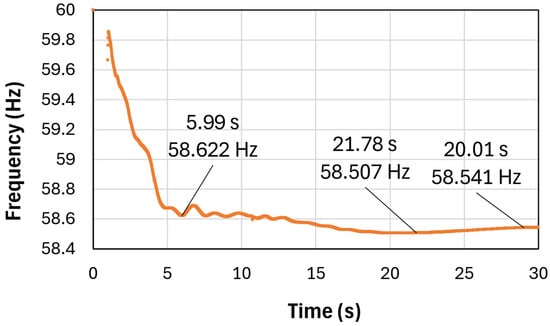

5.6. Case 5: 262 MW Generation Loss with BESS and FESS

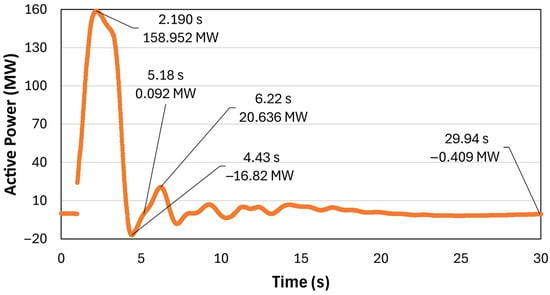

To evaluate the effect of the Flywheel Energy Storage System (FESS) during a simultaneous 262 MW photovoltaic generation loss, Figure 16 and Figure 17 present the dynamic responses of the FESS and BESS.. Figure 16 illustrates that the system delivers a maximum active power of 159 MW at 2.2 s, which then declines to 0 MW after 5.2 s. This inertial contribution of the FESS prevents system collapse due to under-frequency, as shown in Figure 18, where the minimum frequency reaches 58.6 Hz after 6 s. The frequency subsequently stabilizes but does not recover because all Under-Frequency Load Shedding (UFLS) stages have been activated and the entire spinning reserve of the NIS is exhausted. Figure 17 also indicates that the BESS reaches its maximum power output approximately 21 s after the disturbance.

Figure 16.

Total active power response by FESS support (262 MW outage generation).

Figure 17.

Active Power response by BESS support (262 MW outage generation).

Figure 18.

Frequency response with BESS and FESS support (262 MW outage generation).

This is the only case in which the FESS exhibits a significant stabilizing effect. In the previous scenario (Case 4), the system collapsed due to low frequency; however, with the inclusion of the FESS, the frequency slope is improved, and the nadir is reached at 6 s, compared to 4.5 s in the case without FESS. Therefore, the bank of 40 flywheels (total 320 MW) increases the maximum tolerable generation outage before frequency collapse to 262 MW. This contingency is extremely unlikely, as it would require both a loss of interconnection with the Regional Electric System (SER)—resulting in the isolation of Honduras (Stage IV-A)—and the simultaneous disconnection of eight photovoltaic plants totaling 262 MW. A single event of this nature does not justify the acquisition of 40 FESS units.

6. Conclusions

This study presented a dynamic frequency stability assessment of the Honduran National Interconnected System (NIS) under islanded operation, integrating the national Under-Frequency Load Shedding (UFLS) scheme within DIgSILENT PowerFactory simulations. The analysis compared the frequency response provided by Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS) and Flywheel Energy Storage Systems (FESS) across multiple generation-loss contingencies, including a new critical case of 262 MW simultaneous PV outage.

The main findings can be summarized as follows:

- The installation of a 75 MW BESS at Amarateca, currently under construction, significantly improves system resilience. During a 200 MW generation trip, the BESS limited the frequency nadir to 58.74 Hz, effectively preventing UFLS activation.

- The FESS, modeled as 40 synchronous units of 8 MW each (total 320 MW), provided a fast inertial contribution, reducing the initial rate of change of frequency (RoCoF) and delaying UFLS activation by approximately 3.5 s. However, its effect was transient and insufficient to maintain frequency stability in severe contingencies without BESS support.

- Under the combined operation of BESS + FESS, the system avoided collapse even under a 262 MW generation loss, achieving a minimum frequency of 58.6 Hz. This configuration represents the technical upper limit of generation outage that the isolated NIS can withstand.

- The results confirm that BESS offers more sustained and robust frequency support than FESS, validating its prioritization in Honduras’s ongoing storage deployment strategy. FESS may complement BESS through short-term inertial support, but its implementation is less economically justified given current regional conditions.

Methodologically, this work demonstrates a reproducible framework for integrating national UFLS schemes and energy storage models into large-scale stability simulations. The proposed workflow ensures consistency between model initialization, parameterization, and performance evaluation, serving as a reference for similar studies in weak or low-inertia grids across Latin America.

Based on the results, it is recommended to the National Dispatch Center (CND) that the BESS should not be limited exclusively to regulating power exchanges for maintaining the Area Control Error (ACE) at zero, but that it should also participate as a source of synthetic inertia, enabling direct frequency regulation—particularly under isolated operation of the Honduran NIS. It is also suggested that a deadband of 0.5 Hz be adopted to prevent unnecessary BESS activations under normal operating fluctuations.

Although this study focused exclusively on the technical dimension, excluding cost and lifecycle analyses, future work will expand toward techno-economic evaluations and control-strategy optimization to support decision-making for future hybrid energy storage deployment in Central America.

Furthermore, future research should include field trials to validate these results under real operating conditions, as well as integration with ancillary services such as Area Control Error (ACE) regulation, spinning reserve sizing under stochastic PV and load variations, and the assessment of different renewable penetration scenarios. These extensions will contribute to the development of a comprehensive framework for storage-based frequency support and system resilience in the Central American region.

Author Contributions

Contributions: Conceptualization, D.A.R.-L.; methodology, D.A.R.-L.; software, D.A.R.-L., D.T.-A. and C.V.-A.; validation, D.A.R.-L., D.T.-A. and C.V.-A.; formal analysis, D.A.R.-L. and J.M.T.; investigation, D.A.R.-L. and J.M.T.; resources, J.M.T.; data curation, C.V.-A. and J.M.T.; writing—original draft preparation, D.A.R.-L., D.T.-A. and C.V.-A.; writing—review and editing, D.A.R.-L. and. J.M.T.; supervision, D.A.R.-L. and J.M.T.; project administration, D.A.R.-L. and J.M.T. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Directorate of Scientific, Humanistic, and Technological Research (DICIHT): PI-602.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding authors. Data are confidential due to the requirements of the power system operator of Honduras. Nevertheless, the data are available on request from the corresponding authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the Red Iberoamericana de Investigación en Energía y Sostenibilidad Energética (RIBIERSE), as well as the National Autonomous University of Honduras (UNAH) and its Department of Electrical Engineering for providing access to the academic license of DIgSILENT PowerFactory, which was essential for performing the transient dynamic stability simulations in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ramos-Gómez, J.I.; Molina-García, A.; Muñoz-Tabora, J. Power System Modeling and Simulation for Distributed Generation Integration: Honduras Power System as a Case Study. Energies 2025, 18, 4777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, V.B.; Paixão, U.C., Jr.; Moreira, C.E.; Soares, T.M.; Tabora, J.M.; Tostes, M.E.d.L.; Bezerra, U.H.; Albuquerque, B.S.; Gouveia, L.D.S. Modelagem de Um Sistema de Distribuição Real Desbalanceado e Análise Do Impacto Da Geração Distribuída Utilizando o Software OpenDSS. Simpósio Bras. Sist. Elétricos-SBSE 2020, 1, SBSE2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues Dos Reis, J.; Muñoz Tabora, J.; Carvalho de Lima, M.; Pessoa Monteiro, F.; Cruz de Aquino Monteiro, S.; Holanda Bezerra, U.; Emília de Lima Tostes, M. Medium and Long Term Energy Forecasting Methods: A Literature Review. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 29305–29326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huaquisaca Paye, J.C.; Vieira, J.P.A.; Tabora, J.M.; Leão, A.P.; Cordeiro, M.A.M.; Junior, G.C.; Morais, A.P.d.; Farias, P.E. High Impedance Fault Models for Overhead Distribution Networks: A Review and Comparison with MV Lab Experiments. Energies 2024, 17, 1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreira, G.A.M.; Tabora, J.M.; Soares, T.M.; de Lima Tostes, M.E.; Bezerra, U.H.; de M. Carvalho, C.C.M.; de Matos, E.O. Demand Side Management Strategies for the Introduction of Electric Vehicles: A Case Study. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Colombian Caribbean Conference (C3), Barranquilla, Colombia, 22–25 November 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Tabora, J.M.; Paixão Júnior, U.C.; Rodrigues, C.E.M.; Bezerra, U.H.; Tostes, M.E.d.L.; de Albuquerque, B.S.; de Matos, E.O.; Nascimento, A.A. do Hybrid System Assessment in On-Grid and Off-Grid Conditions: A Technical and Economical Approach. Energies 2021, 14, 5284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VOSviewer—Visualizing Scientific Landscapes. Available online: https://www.vosviewer.com// (accessed on 29 June 2024).

- Barelli, L.; Bidini, G.; Bonucci, F.; Castellini, L.; Fratini, A.; Gallorini, F.; Zuccari, A. Flywheel Hybridization to Improve Battery Life in Energy Storage Systems Coupled to RES Plants. Energy 2019, 173, 937–950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elalfy, D.A.; Gouda, E.; Kotb, M.F.; Bureš, V.; Sedhom, B.E. Comprehensive Review of Energy Storage Systems Technologies, Objectives, Challenges, and Future Trends. Energy Strategy Rev. 2024, 54, 101482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rishi, O.; Garg, T.; Kumar, G.; Verma, R.; Singh, D. Performance Analysis of Multi-Area AGC Control of Interconnected Power System with Renewable Energy Sources (RESs) and Energy Storage System (ESS). In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/IAS Industrial and Commercial Power System Asia (I&CPS Asia), Pattaya, Thailand, 9–12 July 2024; pp. 49–54. [Google Scholar]

- Akram, U.; Nadarajah, M.; Shah, R.; Milano, F. A Review on Rapid Responsive Energy Storage Technologies for Frequency Regulation in Modern Power Systems. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 120, 109626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.; Shin, B.Y.; Han, S.; Jung, S.; Park, B.; Jang, G. Compensation for the Power Fluctuation of the Large Scale Wind Farm Using Hybrid Energy Storage Applications. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2012, 22, 5701904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Huang, Y.; Dou, X.; Wang, S.; Chu, T. Optimal Energy Storage Configuration for Primary Frequency Regulation Performance Considering State of Charge Partitioning. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2025, 16, 2659–2668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastián, R.; Peña Alzola, R. Flywheel Energy Storage Systems: Review and Simulation for an Isolated Wind Power System. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 6803–6813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Makarov, Y.; Desteese, J.; Viswanathan, V.; Nyeng, P.; McManus, B.; Pease, J. On the Use of Energy Storage Technologies for Regulation Services in Electric Power Systems with Significant Penetration of Wind Energy. In Proceedings of the 2008 5th International Conference on the European Electricity Market, Lisboa, Portugal, 28–30 May 2008; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Arghandeh, R.; Pipattanasomporn, M.; Rahman, S. Flywheel Energy Storage Systems for Ride-through Applications in a Facility Microgrid. IEEE Trans. Smart Grid 2012, 3, 1955–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E., N.S.G.; Cañizares, C.A.; Bhattacharya, K.; Sohm, D. Frequency Regulation Model of Bulk Power Systems With Energy Storage. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2022, 37, 913–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrigo, F.; Bompard, E.; Merlo, M.; Milano, F. Assessment of Primary Frequency Control through Battery Energy Storage Systems. Int. J. Electr. Power Energy Syst. 2020, 115, 105428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brivio, C.; Mandelli, S.; Merlo, M. Battery Energy Storage System for Primary Control Reserve and Energy Arbitrage. Sustain. Energy Grids Netw. 2016, 6, 152–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debanjan, M.; Karuna, K. An Overview of Renewable Energy Scenario in India and Its Impact on Grid Inertia and Frequency Response. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 168, 112842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, W.D., Jr. Elements of Power System Analysis, 4th ed.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).