A Prototype and Efficiency Analysis of Indirect Regenerative Evaporative Cooling System for Electronics

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

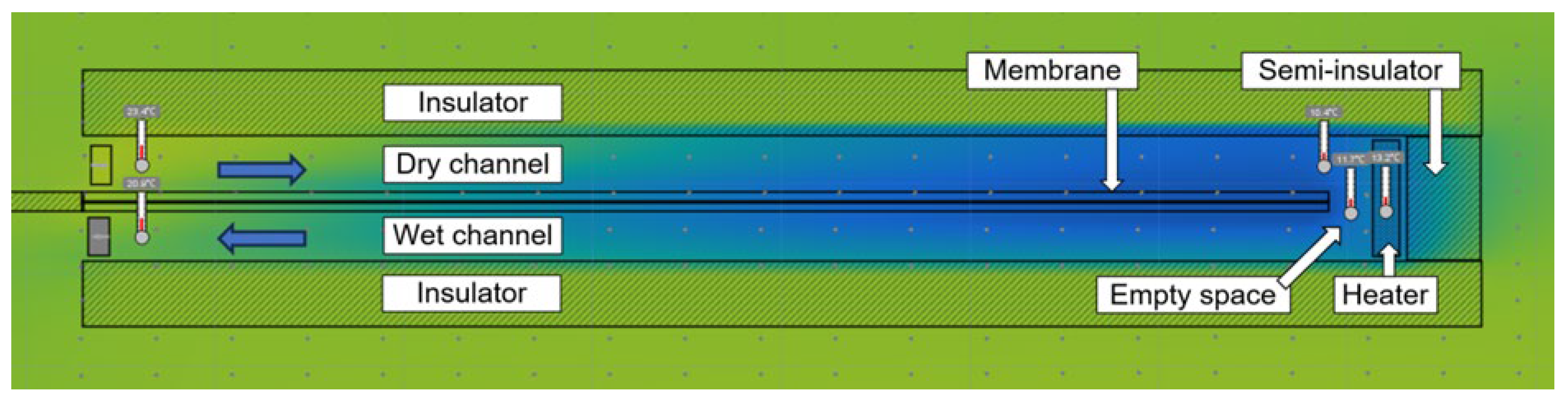

2.1. IREC Heat Exchanger and Test Rig

2.2. Simplified 2D Simulations

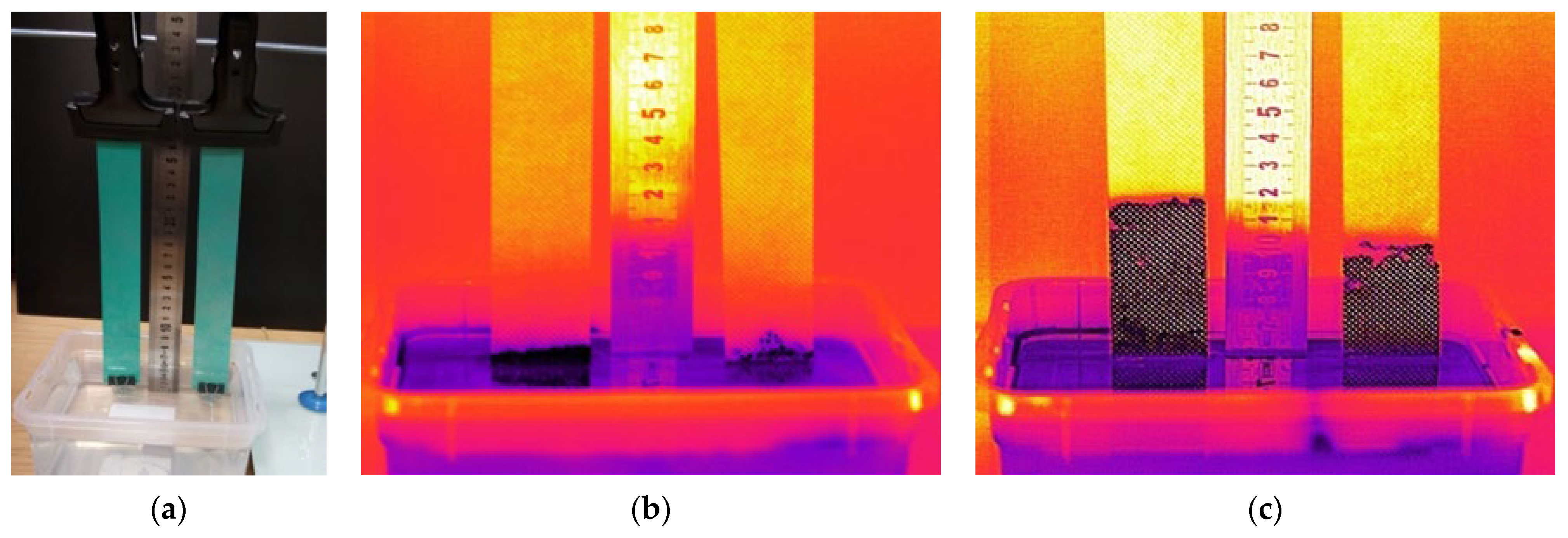

2.3. Investigations and Selection of Porous Membranes

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Simulation Results

3.2. Experimental Results of the FFR Prototype

- The considered design (FFR) of the apparatus.

- The efficiency of organizing the process of heat transfer from the heat-loaded surface.

4. Conclusions

- In the unloaded mode, the heat exchanger showed sufficiently high efficiency, confirming the effectiveness of the IREC technology for the proposed device design.

- During the tests of the current heat exchanger design, several features having a significant impact on the cooling process efficiency and the overall cooling system operation were identified:

- High hydraulic resistance due to low channel height and the 180º air flow turn. This resulted in significant pressure losses, especially in wet channels, and led to the fan operating outside its design zone, energy overconsumption, and increased flow rate measurement errors. Means of pressure loss reduction should be considered, such as HMX channels’ geometry changes. To enhance experimental accuracy, it is recommended to proportionally increase the dimensions of the cooled surface and heat exchanger. Also, for the next prototype, a more precise selection of fans and their performance characteristics should be made.

- Heat input occurs at the flow turn in the device and has a decisive impact on the cooling system’s efficiency. The warm dry air leaving the dry channels heats up, absorbing heat from the hot plate surface and enters the wet channels. As a result, the warm dry air entering the wet channels intensifies the evaporation process from the hydrophilic membrane’s surface, while also transferring heat back to the dry channels, pushing the heat exchanger beyond its effective operation zone. This likely occurs due to the low height of the wet channels and relatively low air flow velocities, leading to the rapid saturation of water vapor near the heat source and weakened evaporation in the main part of the wet channels. Consequently, the air’s relative and absolute humidity at the wet channels outlet are low, which is caused by non-characteristic temperature distribution fields in the device (for setups operating based on IREC technology), as well as the aforementioned channel geometry limitations and airflow organization methods.

- Taking into account the operating features of the IREC device with the FFR design, three efficiency coefficients were proposed, their possible values were analyzed from the point of view of the technology application feasibility for electronic devices cooling, and recommendations were developed aiming to increase the cooling the efficiency of systems using IREC devices.

- Further research is required on the device, considering the influence of the identified factors:

- Testing of a device with an increased height of wet channels. This solution would significantly reduce hydraulic losses and intensify the evaporation process in the wet channels.

- Testing of a device with an increased gap between the heat exchanger membranes and the cooled surface.

- Further research on the membrane materials separating wet channels from dry channels is required.

- Future developments of the setup can include configurations where the heat source has a hydrophilic porous layer with water running through it, along with various heat exchange intensification methods, such as finning or surface treatment.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IREC | Indirect Regenerative Evaporative Cooling |

| DPEC | Dew Point Evaporative Cooling |

| M-cycle | Maisotsenko Cycle |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goals |

| FFR | Full Flow Return |

| HMX | Heat and Mass Exchanger |

References

- Zhang, Z.; Wang, X.; Yan, Y. A review of the state-of-the-art in electronic cooling. e-Prime Adv. Electr. Eng. Electron. Energy 2021, 1, 100009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thesiya, D.; Patel, H.; Patange, G.S. A comprehensive review electronic cooling: A nanomaterial perspective. Int. J. Thermofluids 2023, 19, 100382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aglawe, K.R.; Yadav, R.K.; Thool, S.B. Preparation, applications and challenges of nanofluids in electronic cooling: A systematic review. Mater. Today Proc. 2021, 43, 366–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naphon, P.; Wiriyasart, S.; Wongwises, S. Thermal cooling enhancement techniques for electronic components. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2015, 61, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghrabie, H.M.; Elsaid, K.; Wilberforce, T.; Sayed, E.T.; Abdelkareem, M.A.; Olabi, A.G. Applications of Nanofluids in Cooling of Electronic Components. In Encyclopedia of Smart Materials; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 310–318. [Google Scholar]

- Maghrabie, H.M.; Olabi, A.G.; Sayed, E.T.; Wilberforce, T.; Elsaid, K.; Doranehgard, M.H.; Abdelkareem, M.A. Microchannel heat sinks with nanofluids for cooling electronic components: Performance enhancement, challenges, and limitations. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2023, 37, 101608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agostini, B.; Fabbri, M.; Park, J.E.; Wojtan, L.; Thome, J.R.; Michel, B. State of the art of high heat flux cooling technologies. Heat Transf. Eng. 2007, 28, 258–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohel Murshed, S.M.; Nieto de Castro, C.A. A critical review of traditional and emerging techniques and fluids for electronics cooling. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 78, 821–833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Śmierciew, K.; Butrymowicz, D.; Karwacki, J.; Bergander, M.J.; Gagan, J. Design, fabrication, and investigations of prototype supersonic micro-ejector for innovative cooling system of electronic components. Int. J. Refrig. 2023, 153, 323–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, W.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, X. Research on passive cooling of electronic chips based on PCM: A review. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 340, 117183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Sun, W.; Zhang, Z.; Ling, Z.; Fang, X. Thermal protection of electronic devices based on thermochemical energy storage. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2021, 186, 116507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanda, G. Cooling solutions for an electronic equipment box operating on UAV systems under transient conditions. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2020, 152, 106286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahiraei, M.; Heshmatian, S. Electronics cooling with nanofluids: A critical review. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 172, 438–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulpagare, Y.; Bhargav, A. Advances in data center thermal management. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 43, 981–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arulprakasajothi, M.; Raja, N.D.; Saranya, A.; Elangovan, K.; Murugapoopathi, S.; Poyyamozhi, N.; Amesho, K.T. Optimizing heat transfer efficiency in electronic component cooling through fruit waste-derived phase change material. J. Energy Storage 2024, 80, 110238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhu, J.; Li, J.; Feng, H.; Hu, D.; Chen, X.; Li, Q. Chill and charge: A synergistic integration for future compact electronics. Device 2024, 2, 100367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zou, A.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Z. Impact of jet intermittency on surface-structured heat sinks for electronics liquid cooling. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 236, 121911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymanski, P.; Paluch, R. Experimental investigation on heat pipes supported by soy wax and lauric acid for electronics cooling. J. Energy Storage 2024, 83, 110813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, S.; Shukla, D.; Kumar Panigrahi, P. A review on coolant selection for thermal management of electronics and implementation of multiple-criteria decision-making approach. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 245, 122807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anandhabalaji, V.; Babu, M.; Brintha, R. Energy consumption by cryptocurrency: A bibliometric analysis revealing research trends and insights. Energy Nexus 2024, 13, 100274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Chen, Z.; Qian, C.; Li, Q.; Chen, X. Durable and mechanically robust superhydrophobicradiative cooling coating. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 478, 147341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandi, K.; Jaganathan, V.M.; Suresh, S.; Akhil, A.K. Experimental analysis simulation of passive flexible heat transfer device. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2024, 199, 108902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, G.; Li, J.; Jia, Z. Power-saving exploration for high-end ultra-slim laptop computers with miniature loop heat pipe cooling module. Appl. Energy 2019, 239, 859–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Yan, W.; Wang, S. Study on heat transfer characteristics of a dual-evaporator ultra-thin loop heat pipe for laptop cooling. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 241, 122395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, F.; Zhou, G.; Zhou, J.; Huai, X.; Jiang, Y. A novel ultra-thin vapor chamber with radial-gradient hierarchical wick for high-power electronics cooling. Int. J. Therm. Sci. 2023, 183, 107896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azarifar, M.; Arik, M.; Chang, J.Y. Liquid cooling of data centers: A necessity facing challenges. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 247, 123112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Li, Y.; Chen, Z.; Deng, L.; Gan, Y. Ultra-thin flattened heat pipe with a novel band-shape spiral woven mesh wick for cooling smartphones. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2020, 146, 118792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paneerselvam, P.; Narendranathan, S.K.; Suyamburajan, V.; Murugaiyan, T.; Singh Shekhawat, K.; Rengasamy, G. A review on recent progress in battery thermal management system in electric vehicle application. Mater. Today Proc. 2024, in press. [CrossRef]

- Chavan, S.; Venkateswarlu, B.; Prabakaran, R.; Salman, M.; Joo, S.W.; Choi, G.S.; Kim, S.C. Thermal runaway and mitigation strategies for electric vehicle lithium-ion batteries using battery cooling approach: A review of the current status and challenges. J. Energy Storage 2023, 72, 108569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teranishi, A.; Kurogi, T.; Senaha, I.; Matsuda, S.; Yasuda, K. Mist cooling lithium–ion battery thermal management system for hybrid electric vehicles. Appl. Energy 2024, 364, 123214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Lu, Y.; Ouyang, H.; Ren, X.; Yang, J.; Guo, H.; Han, X.; Zhang, C.; Wu, Y. Theoretical and experimental investigations on liquid immersion cooling battery packs for electric vehicles based on analysis of battery heat generation characteristics. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 310, 118478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amosedinakaran, S.; Kannan, R.; Kannan, S.; Ramkumar, A.; Suresh, S.; Bhuvanesh, A. Performance Analysis for Battery Stability Improvement using Direct Air Cooling Mechanism for Electric Vehicles. e-Prime Adv. Electr. Eng. Electron. Energy 2024, 8, 100585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Du, X.; Wei, Y.; Zhu, H.; Kong, Y.; Zhao, H.; Jiao, B.; Liu, X.; Qian, X.; Yang, R. Hotspot Thermal Management Using Thermoelectric and Microchannel Hybrid Cooling at Transient and Steady States. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2025, 265, 125556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacak, A.; Sierpowski, K.; Baran, B.; Malecha, Z.; Worek, W.; Cetin, S.; Pandelidis, D. Impact of air distribution on dew point evaporative cooler thermal performance. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2023, 224, 120137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, J.; Xu, W.; Fu, Y.; Huo, H. Experimental research on the cooling performance of a new regenerative dew point indirect evaporative cooler. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 43, 102921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Ren, C.; Yang, C.; Tu, M.; Luo, B.; Fu, J. Energy and exergy performance comparison of conventional, dew point and new external-cooling indirect evaporative coolers. Energy Convers. Manag. 2021, 230, 113824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Akhlaghi, Y.G.; Zhao, X.; Li, J. Experimental and numerical investigation of a high-efficiency dew-point evaporative cooler. Energy Build. 2019, 197, 120–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Wang, R.; Li, C.; Wang, S.; Long, J.; Chua, K.J. Towards a thermodynamically favorable dew point evaporative cooler via optimization. Energy Convers. Manag. 2020, 203, 112224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Ma, X.; Zhao, X.; Fancey, K. Experimental investigation of a super performance dew point air cooler. Appl. Energy 2017, 203, 761–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dizaji, H.S.; Hu, E.; Chen, L.; Pourhedayat, S.; Wae-hayee, M. Proposing the Concept of Mini Maisotsenko Cycle Cooler for Electronic Cooling Purposes; Experimental Study. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2021, 27, 101325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Liu, J. A state-of-art review of dew point evaporative cooling technology and integrated applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 191, 114142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Wen, T.; Wang, Q.; Xu, X. A review of dew-point evaporative cooling: Recent advances and future development. Appl. Energy 2022, 312, 118785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapilan, N.; Isloor, A.M.; Karinka, S. A comprehensive review on evaporative cooling systems. Results Eng. 2023, 18, 101059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajjad, U.; Abbas, N.; Hamid, K.; Abbas, S.; Hussain, I.; Ammar, S.M.; Sultan, M.; Ali, H.M.; Hussain, M.; Rehman, T.U.; et al. A review of recent advances in indirect evaporative cooling technology. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2021, 122, 105140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.S.; MohdZubir, M.N.; Muhamad, M.R.B.; Kazi, S.N.; Öztop, H.F.; Abdullah, S.; Shaikh, K. A technological review of dew point evaporative cooling: Experimental, analytical, numerical and optimization perspectives. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 91, 109544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, M.H.; Sultan, M.; Miyazaki, T.; Koyama, S.; Maisotsenko, V.S. Overview of the Maisotsenko cycle—A way towards dew point evaporative cooling. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 66, 537–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güzelel, Y.E.; Olmuş, U.; Büyükalaca, O. Simulation of a desiccant air-conditioning system integrated with dew-point indirect evaporative cooler for a school building. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2022, 217, 119233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulaiman, M.A.; Adham, A.M.; Hasan, H.F.; Benim, A.C.; Anjal, H.A. Performance analysis of novel dew point evaporative cooler with shell and tube design through different air-water flow configurations. Energy 2024, 289, 129922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Chen, W.; Zhang, D.; Wen, T. Performance evaluation of counter flow dew-point evaporative cooler with a three-dimensional numerical model. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2023, 219, 119483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandelidis, D.; Niemierka, E.; Pacak, A.; Jadwiszczak, P.; Cichoń, A.; Drąg, P.; Worek, W.; Cetin, S. Performance study of a novel dew point evaporative cooler in the climate of central Europe using building simulation tools. Build. Environ. 2020, 181, 107101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Wang, S.; Lin, J.; Shao, Y.; Gao, F.; Chua, K.J. The enhanced dew-point evaporative cooling with a macro-roughened structure. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2024, 219, 124898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comino, F.; Romero-Lara, M.J.; Ruiz de Adana, M. Experimental and numerical study of dew-point indirect evaporative coolers to optimize performance and design. Int. J. Refrig. 2022, 142, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohani, A.; Sayyaadi, H.; Mohammadhosseini, N. Comparative study of the conventional types of heat and mass exchangers to achieve the best design of dew point evaporative coolers at diverse climatic conditions. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 158, 327–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhu, G.; Liu, M.; Guo, C.; Lv, J.; Wang, L. Theoretical study on the wetting rate in wet channel of dew-point evaporative cooler based on Marangoni effect. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 73, 106806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-González, J.; Comino, F.; Navas-Martos, F.J.; Ruiz de Adana, M. Manufacturing and experimental analysis of a dew-point indirect evaporative cooler using fused deposition modelling 3D printing and polymeric materials. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2023, 230, 120683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Lv, J.; Zhu, M.; Wang, L.; Li, S.; Hu, E. Experiment for the performance of a thin membrane inclined automatic wicking dew-point evaporative cooling device based on simulation results. Energy Build. 2024, 308, 114021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Lv, J.; Zhu, M.; Wang, L.; Liang, L.; Chen, Q. Simulation study of a thin membrane inclined automatic wicking dew-point evaporative cooling device. J. Build. Eng. 2023, 72, 106601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Khalid, W.; Ali, H.M.; Sajid, M.; Ali, Z.; Ali, M. An experimental investigation on the novel hybrid indirect direct evaporative cooling system. Int. Commun. Heat Mass Transf. 2024, 155, 107503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero-Lara, M.J.; Comino, F.; Ruiz de Adana, M. Experimental assessment of the energy performance of a renewable air-cooling unit based on a dew-point indirect evaporative cooler and a desiccant wheel. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 310, 118486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, J.; Xu, H.; Xu, T.; Liu, H.; Qin, J. Study on the performance of a unit dew-point evaporative cooler with fibrous membrane and its application in typical regions. Case Stud. Therm. Eng. 2024, 24, 100881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, L.; Wang, X.; Hu, E.; Ng, K.C. A vision of dew point evaporative cooling: Opportunities and challenges. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2024, 244, 122683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracking SDG7: The Energy Progress Report. Available online: https://trackingsdg7.esmap.org/ (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Sustainable Development Goal 7.3: Calls for Doubling the Global Rate of Improvement in Energy Efficiency Between Compared with the 1990–2010 Baseline. Sustainable Energy for All Project. Available online: https://www.seforall.org/our-work/sustainable-development-goal-7-sdg7 (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- SDG 7—Affordable and Clean Energy. Eurostat. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=SDG_7_-_Affordable_and_clean_energy (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Tracking SDG7: The Energy Progress Report—2024. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/tracking-sdg7-the-energy-progress-report-2024 (accessed on 13 June 2025).

- Xie, C. Interactive Heat Transfer Simulations for Everyone. Phys. Teach. 2012, 50, 237–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Association of Textile Chemists and Colorists (AATCC). Technical Manual, Test Method for Vertical Wicking of Textiles (TM-197); AATCC: Durham, NC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Komisarczyk, A.; Dziworska, G.; Krucińska, I.; Michalak, M.; Strzembosz, W.; Kaflak, A.; Kałuża, M. Visualisation of Liquid Flow Phenomena in Textiles Applied as a Wound Dressing. Autex Res. J. 2013, 13, 141–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kałuża, M.; Hatzopoulos, A. Application of extension rings in thermography for electronic circuits imaging. Quant. InfraRed Thermogr. J. 2024, 1, 50–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morosuk, T.; Tsatsaronis, G. The ‘‘Cycle Method’’ used in the exergy analysis of refrigeration machines: From education to research. In Proceedings of the 19th International Conference on Efficiency, Cost, Optimization, Simulation and Environmental Impact of Energy Systems, Crete, Greece, 12–14 July 2006; Frangopoulos, C., Rakopoulos, C., Tsatsaronis, G., Eds.; National Technical University of Athens: Athens, Greece, 2006; Volume 1, pp. 157–163. [Google Scholar]

- Online Interactive Psychrometric Chart. Available online: https://www.flycarpet.net/en/psyonline (accessed on 10 July 2025).

- Morosuk, T.; Tsatsaronis, G. Strengths and limitations of advanced exergetic analyses. In Proceedings of the ASME International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition, Proceedings (IMECE), San Diego, CA, USA, 15–21 November 2013; Volume 6B. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khliyeva, O.; Shestopalov, K.; Ierin, V.; Zhelezny, V.; Chen, G.; Neng, G. Environmental and Energy Comparative Analysis of Expediency of Heat-Driven and Electrically-Driven Refrigerators for Air Conditioning Application. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2023, 219, 119533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Heating | Thermocouple | Ambient | Input | Empty Space | Output | Dry Channel | Dissipated Power |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mode | Tth, °C | Ta, °C | TDB, °C | TH, °C | Tout, °C | TDC, °C | P, W |

| Off | 13.2 | 22.6 | 23.4 | 11.7 | 20.9 | 10.4 | 0 |

| On | 45 | 22.6 | 23.4 | 32.4 | 20.3 | 18.7 | 9.09 |

| Heating | Thermocouple | Ambient | Input | Empty Space | Output | Dry Channel | Dissipated Power | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mode | Tth, °C | Ta, °C | RH, % | TDB, °C | RHDB, % | DP, °C | WB, °C | TH, °C | RHH, % | Tout, °C | RHout, % | TDC, °C | RHDC, % | P, W |

| Off | 15.4 | 22.6 | 29.4 | 23.8 | 27.0 | 3.6 | 13.4 | 11.6 | 58.7 | 20.2 | 48,7 | 7.6 | 77.8 | 0 |

| On | 45.0 | 22.9 | 28.4 | 24.3 | 25.1 | 3.1 | 13.0 | 31.6 | 17.2 | 22.1 | 41,4 | 18.0 | 38.3 | 9 |

| Heating is On | Heating is Off | |

|---|---|---|

| Points/Process | H, kJ/kg | H, kJ/kg |

| Heat Source (HS) | 57.5 | no |

| 1 | 35.1 | 35.3 |

| 2 | 36.5 | 36.5 |

| 3 | 30.1 | 20.1 |

| 4 | 43.9 | 24.1 |

| 5 | 39.7 | 38.6 |

| at (Tdp) | 15.0 (3.12 °C) | 16.1 (3.7 °C) |

| Process | Value, kJ/kg | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| 1.4 | heat supply during the process of air injection into the heat exchanger (with an increase in temperature of approximately 1 °C) | |

| −6.3 | real cooling process of the supplied air in dry channels of the heat exchanger | |

| 13.8 | real process of heat transfer to cooled dry air from the surface of a heating source without changing the absolute moisture content in real FFR HMX | |

| 27.3 | “ideal”/theoretical process of heat transfer to cooled dry air from the surface of a heating source without changing the absolute moisture content in real FFR HMX | |

| −4.2 | real cooling process of heated air in the wet channels of a heat exchanger due to the evaporation process | |

| 0 | adiabatic cooling of heated air in wet channels of a heat exchanger due to the evaporation process (actual process is not shown) | |

| 0 | adiabatic cooling of heated air in wet channels of a heat exchanger due to the evaporation process (“ideal process” is not shown) | |

| −21.4 | “ideal”/theoretical process of the supplied air cooling in the dry channels of the heat exchanger | |

| −22.4 | cooling capacity potential of the ambient air | |

| 42.4 | “ideal”/theoretical process of heat transfer to cooled dry air from the surface of a heating source without changing the absolute moisture content in theoretical FFR HMX |

| Value | Meaning | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| The IREC unit’s cooling capacity is low compared to the ambient air’s cooling potential. The heat exchanger is either not operating efficiently under the current ambient inlet conditions, or the temperature of the heated surface is too high, or the ambient air temperature is too low. | There are several potential reasons that could have caused this. First of all, one should evaluate the temperature level of the heat source and the environment. Perhaps the temperature level of the heat source is too high or the ambient temperature is too low. A similar situation is also possible with a low or moderate temperature of the heat source and high temperature and relative humidity of the environment. If there is no critical need to supply low-temperature cooled air to the heated surface, the feasibility of using a heat exchanger should be considered. The geometry of the device is incorrectly selected. First of all, it is necessary to consider changing (increasing) the length and number of cells of the heat exchanger. | |

| The cooling capacity of the IREC unit is equal to the cooling potential of the surrounding air. Depending on the temperature level of the heated surface and the surrounding environment, its value can be quite significant. This is the lower limit of efficiency for the rational use of the IREC unit in the current design. | It is recommended to conduct a technical and economic analysis of this device in comparison with the use of classic cooling systems based on forced convection (fan + radiator). Since the positive effect of using the IREC device increases with increasing ambient temperature, it is recommended to optimize the design and geometry of the device for conditions with higher temperatures. | |

| The IREC unit’s cooling capacity exceeds the cooling potential of the environment. The use of the device is justified! | Further increase in the productivity and efficiency of the heat exchanger may consist of the following:

|

| Coefficients | Value | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| In the case when this coefficient takes values below zero, the numerical negative values are difficult to analyze for an accurate quantitative assessment, considering all possible reasons for it. In general, it means that the cooling capacity potential of the ambient air is significant comparing to the IREC HMX cooling capacity increment. Its application is preferable at high ambient temperatures and/or lower humidity of ambient air. | ||

| 0.5 | Heat removal from the heated surface should be improved | |

| 0.09 ÷ 0.15 (15) | At this stage of the investigation, the actual value is senseless, since the FFR was tested with an extremely overpowered fan, VKM 150, with a peak power of 100 W, a volumetric flowrate about 580 m3/h, and a pressure 350 Pa. This fan was dedicated for test rig operation in a wide range of volumetric flowrates and pressures to define the limits of the tested prototypes. Therefore, even with smooth fan control, its power consumption greatly exceeds the power of the fan selected for the required flow and pressure parameters. The estimated value in brackets, provided that the fan is selected for a given volumetric flow rate for the FFR prototype. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Levchenko, D.; Olbrycht, R.; Kałuża, M.; Felczak, M.; Kubiak, P.; Więcek, B. A Prototype and Efficiency Analysis of Indirect Regenerative Evaporative Cooling System for Electronics. Energies 2025, 18, 6288. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236288

Levchenko D, Olbrycht R, Kałuża M, Felczak M, Kubiak P, Więcek B. A Prototype and Efficiency Analysis of Indirect Regenerative Evaporative Cooling System for Electronics. Energies. 2025; 18(23):6288. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236288

Chicago/Turabian StyleLevchenko, Dmytro, Robert Olbrycht, Marcin Kałuża, Mariusz Felczak, Przemysław Kubiak, and Bogusław Więcek. 2025. "A Prototype and Efficiency Analysis of Indirect Regenerative Evaporative Cooling System for Electronics" Energies 18, no. 23: 6288. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236288

APA StyleLevchenko, D., Olbrycht, R., Kałuża, M., Felczak, M., Kubiak, P., & Więcek, B. (2025). A Prototype and Efficiency Analysis of Indirect Regenerative Evaporative Cooling System for Electronics. Energies, 18(23), 6288. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236288