Abstract

The international tertiary education sector was significantly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic due to the risk of negative learning and psychosocial experiences. Most international students who remained in the host countries demonstrated admirable resilience and adaptability during those challenging times. An integrative review of factors shaping international students’ learning and mental wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic was conducted. Five electronic databases—CINAHL, MEDLINE, ProQuest, PsycINFO, and Web of Science—were searched from 2020 to 2023 using the key search terms ‘international students’, ‘tertiary education’, ‘mental health and wellbeing’, and ‘COVID’. A total of 38 studies were included in this review. They revealed six factors across learning and psychosocial experiences. Predisposing factors for maladjustments included the students being younger and possessing poor English proficiency. Precipitating factors were related to online teaching/learning, and lack of accessibility and or insufficient learning and living resources. Perpetuating factors pertained to living arrangements. The protective factor identified was institutional support. This review highlighted that multifaceted factors were associated with international students’ experiences and mental health and wellbeing. In-depth understanding of risk and protective factors can help policymakers to prepare for unprecedented challenges and reduce disruptions to international students’ education and mental health when studying abroad.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 public health pandemic impacted all sectors of the community, including universities [1]. As the global crisis escalated, international tertiary education was among the first global sectors that were significantly impacted, as many international students returned to their countries of origin [2]. The unavoidable social isolation and close-down policies not only caused abrupt changes in the landscape of teaching delivery and learning experiences but also impacted the psycho-social wellbeing of domestic and international students [3]. In particular, the three most reported mental health issues by students were anxiety [4,5], depression [6,7], and stress [8,9]. Up to 65.5% of students felt dissatisfied with their learning experience during the pandemic [10,11,12]. However, despite knowing that there would be curfews, border closures, and travel restrictions [13], a significant number of international students still chose to remain in their host countries to continue with their studies in undergraduate or postgraduate courses.

Even prior to the pandemic, international students were considered a vulnerable group as they were at risk of developing poor mental health due to language barriers, lack of support from families and friends, and the need to acculturate to unfamiliar educational and living conditions [14,15,16]. During the pandemic, these vulnerabilities were exacerbated as most international students who chose to remain in their host countries could only contact their families and friends by phone or online due to travel restrictions and lockdowns [14,17]. Their experience with long periods of physical distancing from their loved ones induced feelings of loneliness and homesickness [17]. Some students with Asian backgrounds also experienced racial discrimination in the host community, which caused them to doubt and regret their decision to remain in their host countries [14,18].

The pandemic also caused marked disruptions to normal learning and teaching patterns. For example, all or some of the face-to-face classes were transformed into online classes; clinical placements/field work were cancelled; examination and assessment formats were changed without the students being given much notice [1,2]. These rapid changes added to the burdens faced by international students, who had to develop digital literacy quickly, ensure internet access, and learn how to navigate online learning platforms while dealing with pre-existing vulnerabilities [1,2].

Despite having a higher risk of experiencing poorer learning, mental health, and wellbeing, most international students who remained in their host countries demonstrated admirable resilience and adaptability during these times [19]. However, resilience does not negate the complexities of their experiences as these students continued to navigate numerous academic, social, and emotional challenges. To date, no study has systematically reviewed the research evidence on factors affecting international students’ learning experiences and mental wellbeing. As such, the aim of this paper was to conduct a comprehensive literature review to yield an in-depth understanding of risk and protective factors for international students.

2. Materials and Methods

An integrative review was conducted, guided by a 5-stage framework by Whittemore and Knafl (2005) [20]. An integrative review is a method of research that appraises, analyses, and integrates literature on a topic so that new frameworks and evaluations are generated. This methodology allows the inclusion of studies with diverse data collection methods, including quantitative, quantitative, or mixed methods [21]. The PRISMA statement was also used to structure the review, minimise analysis bias, and systematically present findings [22].

2.1. Literature Search Strategy

The purpose of the narrative integrative review was to collate and synthesize research evidence from 1st January 2020 to 31st December 2023 that focused on international tertiary students’ (i) learning experiences and (ii) mental health and wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic. A search was conducted in the following five electronic databases: CINAHL, MEDLINE, ProQuest, PsycINFO and Web of Science. Database-specific subject headings and relevant text words were used. Search strategies contained terms related to (international or foreign*) AND (student* or postgrad* or “post-grad*” or undergrad* or “under-grad*) AND (university* or college*) AND (‘learning’ or ‘coping’ or ‘wellbeing’ or “well being” or wellness or “mental* health*” or “mental hygiene” or stress*) AND (coronavir* OR “corona virus*” OR betacoronavir* OR COVID-19 OR “COVID-19” OR “COVID-2019” OR COVID2019 OR pandemic).

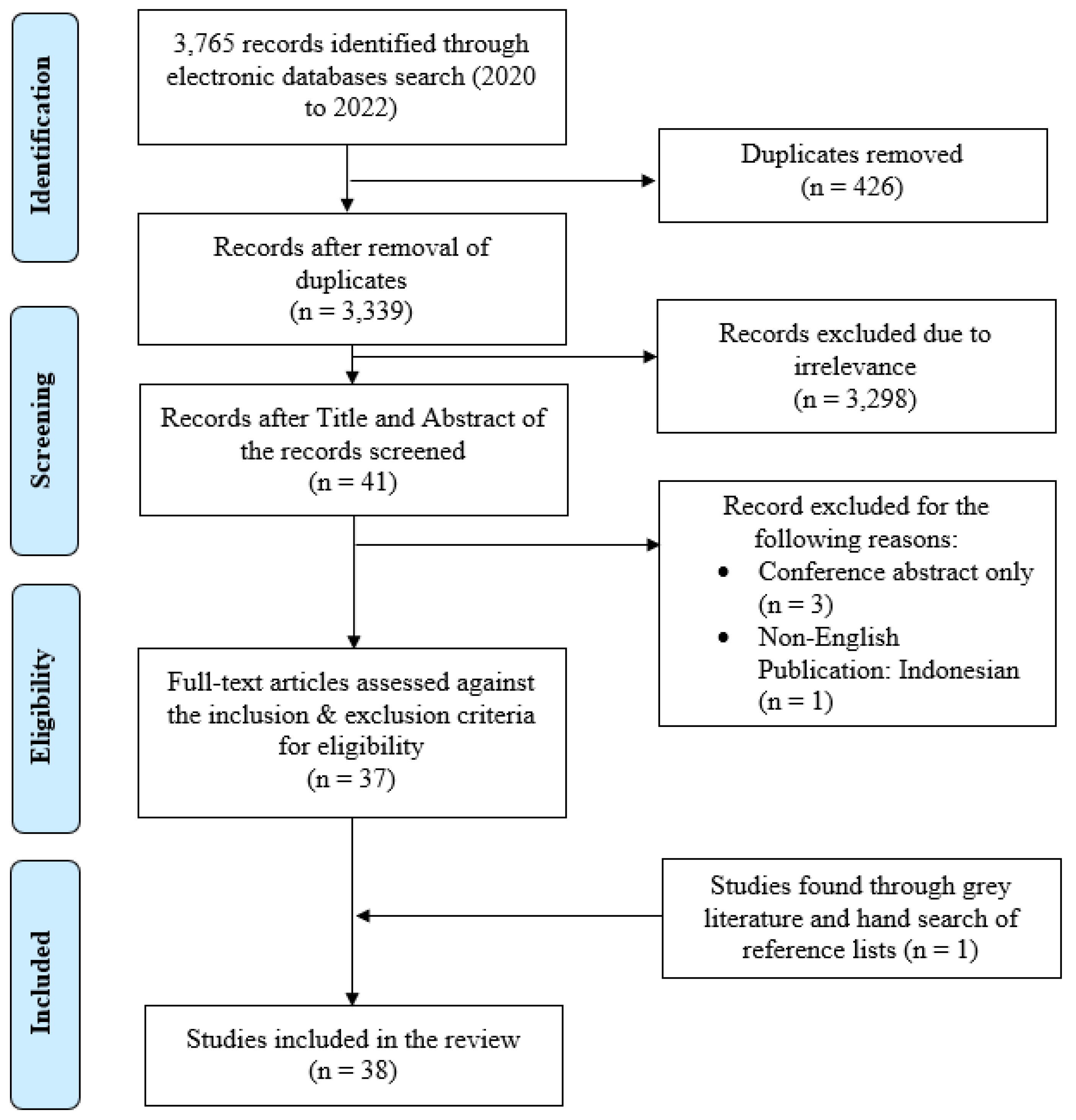

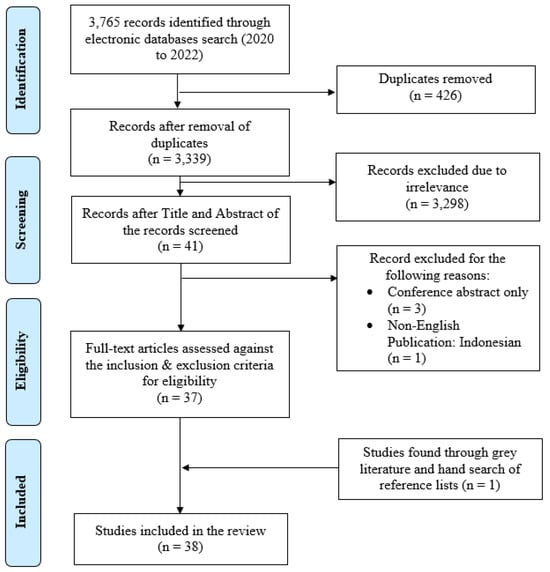

The titles and abstracts of the downloaded papers were independently screened by two reviewers (HZ and EL) to identify studies that were eligible for inclusion. Papers were eligible for inclusion if they were (a) published in English, (b) peer-reviewed, (c) had clear evidence of research methodology, and (d) relevant to the purpose of the narrative integrative review. Subsequently, the full texts of the eligible papers were retrieved and read to confirm the number of papers to be included. All divergent opinions were resolved by a third independent reviewer (EL) (Figure 1). A search of unpublished academic theses from a university library and a manual search of the reference lists were also carried out to locate any potential studies for inclusion.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the search and study selection process (PRISMA).

2.2. Quality Appraisal of Included Studies

The quality of the included papers was appraised independently by two authors (HZ and EL). Three types of studies (cross-sectional surveys, qualitative interview studies, or mixed-methods studies) were independently assessed using the mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) [23] (Hong et al., 2018). The MMAT systematically appraises the quality of studies by assessing research design, data collection method, data analysis, and interpretation of results.

2.3. Data Analysis and Narrative Synthesis

The 4Ps model of case formulation [24] was used to systematically categorise the extracted information from the included papers related to international tertiary students’ learning experiences and mental health wellbeing while living in their host countries during the COVID-19 pandemic. Using the 4Ps model of case formulation, manual coding was completed inductively based on the meaning of the identified factors and organised into (i) predisposing, (ii) precipitating, (iii) perpetuating, and (iv) protective factors. This model was selected as it allowed the researchers to categorise the data and provide a structured understanding of the risk and protective factors that contribute to international students’ experience. All of the authors checked and validated that the extracted information was sorted into the right category, and this step ensured the trustworthiness of the process. Subsequently, information extracted from each category was narratively synthesised to facilitate writing up the findings. This provided a more holistic understanding of the factors that influenced international students who stayed in their host country during the COVID-19 pandemic.

3. Results

3.1. Literature Search Results

A search of five databases generated 3765 records. Duplicated records (n = 426) were first removed, followed by excluding 3298 irrelevant records based on the title and abstract. Of the remaining 41 records, four were further excluded, as three were conference abstracts and one was a non-English publication. Full texts of the remaining 37 records were retrieved. Unpublished academic theses were also searched. A manual search of the reference lists of the 37 remaining papers identified one additional paper for inclusion. A total of 38 papers were included in the narrative integrative review.

3.2. Outcome of Critical Appraisal of Included Studies

An assessment of the included studies is presented in Table 1. All 38 included papers provided sufficient information on the study population, with selection criteria, outcome measurements, data collection methods, and data analysis. No studies were further excluded based on their quality.

Table 1.

Quality assessment of the 38 included studies using MMAT.

3.3. Characteristics of the Included Papers

All 38 papers included in this narrative integrative review involved international undergraduate or postgraduate students who remained in their host countries to continue with their studies during the COVID-19 pandemic. The sample size of the included papers ranged from 20 [6] to 7199 [45]. Of the 38 studies, 15 were conducted in China, seven in the United States of America (USA), two each in Australia and Poland, and one each in Germany, Indonesia, Italy, Jordan, Korea, The Netherlands, New Zealand, Russia, Taiwan, Turkey, United Kingdom, and Ukraine (Table 2). Twenty-eight of the 38 included studies were cross-sectional surveys; six were qualitative studies conducted via focus group interviews (n = 3), one-to-one semi-structured interviews (n = 2), and biographical method/writing an essay (n = 1); and four were mixed methods using survey and focus groups.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the 38 included papers.

3.4. Factors Influencing International Students’ Learning Experiences During the COVID-19 Pandemic

A total of 20 factors associated with the learning experiences of international students were extracted from three of the included studies. Four of the 16 factors were categorised as predisposing factors and contributed to reasons that can negatively impact the learning experiences of international students (Refers to Table 3). These four factors were (1) being female in the host country [29], (2) having English as their second language [26], (3) being in the basic year/beginning of their course [12], and (4) pressure from family [26].

Table 3.

Summary of main findings of the 38 included papers.

Ten of the studies included in this integrative review provided evidence of six precipitating factors that led to international students having poor learning experiences. They were (1) lack of practical classes or lack of clinical placements [12,46], (2) lack of resources and support for research, laboratory, and library services due to curfews [25,26,46], (3) unstable and slow internet connection [11,26,36,46], (4) encountered difficulty navigating online platforms with insufficient support for online teaching [10,11,26,36,50,53], (5) feared for their own and their families’ health [12,36,50], and (6) had a feeling of uncertainty about study progression and career opportunity [12,28].

The disruptions and changes to teaching and learning activities highlighted two perpetuating factors experienced by international students, resulting in poor learning experiences. These two factors were (1) distractions in the home environment [36,53] and (2) diminished interest in online learning due to the absence of interaction with peers and lecturers [36,50,53].

Seven of the 38 included studies identified eight protective factors deemed to be critical for international students to maintain positive learning experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. These protective factors were subcategorised into personal factors and institutional factors. Personal factors included (1) exercising self-discipline to participate in online learning activities [12], (2) perceiving self-isolation as opportunities to engage in new hobbies or connect with family/friends virtually [12,26,28,53], and (3) having social contact and sufficient COVID-19 knowledge [29]. Institutional factors included (1) receiving communication from academic staff [26], (2) having well-designed and easily accessible learning materials [12,28,36], (3) having flexible learning times [11,53], (4) receiving well-structured assessments [11,12,53], and (5) receiving individualised pastoral care and learning support from the school/ university [12,26,36].

3.5. Factors Influencing Mental Health and Wellbeing of International Students During the COVID-19 Pandemic

A total of 29 factors associated with the mental health and wellbeing of international students were extracted and grouped under the 4Ps factors. Nine of the 38 included articles identified three predisposing factors, including (1) being younger [4,9,27,35], (2) being female [9,29,34,39,43,48,49], and (3) having English as a second language [26].

Twenty-one of the included articles reported nine factors that could have precipitated poorer mental health and wellbeing of international students who stayed in the host country during the pandemic. These factors were as follows: (1) had enrolled in undergraduate courses or non-health related majors [4,37,45], (2) severity of the impact of the pandemic on the host country [7,31,41], (3) being diagnosed with COVID-19 [5,30], (4) feared for personal and family’s health [9,32,33,34,38,41], (5) felt disconnected and lonely due to curfews and social isolation [6,27,30,34,35,39,48,51,52], (6) changed from in-class to purely online teaching [8,30,35,51], (7) had feelings of uncertainty of study progression and career trajectory [6,41,49,52], (8) experienced acculturating stress [33], and (9) experienced anti-Asian sentiments [6].

Nine of the included studies identified five perpetuating factors that were associated with the mental health and wellbeing of international students during the COVID-19 pandemic. The five factors were (1) living arrangements: either in the metropolitan region of the host country, in a shared house with other people, or living alone and in rural areas [4,5,8,34,41,52]; (2) financial hardships because they were unable to work due to curfews or lacked monetary support from family [5,9,30,34,45]; (3) excessive media exposure to COVID-19 information and government management plans [5,41]; (4) close-contact with people positive for COVID-19 [5]; and (5) negative coping styles [45,47].

Sixteen articles identified six institutional and six personal factors that were perceived by international students as protective of their mental health and wellbeing during the COVID-19 pandemic. The data analysis contributed evidence that international students experienced fewer psychological issues, such as anxiety and/or depression, when their enrolled institutions (1) responded appropriately to the pandemic [44], (2) provided them with flexible visa arrangements [33], (3) had a designated international student support team [8], (4) provided them with living/financial relief [6,33,48], (5) provided them with timely and reliable information [6,33,37,38], and (6) provided sufficient resources for teaching, such as a library or flexible learning and examination systems [6,8,33] and research equipment and laboratories [33].

Six personal protection factors associated with decreased risks of experiencing anxiety and/or depression included (1) receiving social support from peers and family via virtual communication platforms [8,30,31,33,40,41,48]; (2) living arrangements involving living with family [38,45] or in big cities [35]; (3) having tuition fees paid by family or borrowing from others [45]; (4) being positive [40,41,44,47] and engaging in exercise, worship, cooking, watching COVID-19 news, and playing video games [39]; (5) seeking professional advice when experiencing negative emotions [30,42,52]; and (6) enrolling in postgraduate courses or health-related majors [34,37].

4. Discussion

Thirty-eight studies were included in this review and revealed a total of 37 factors that affected the learning, mental health, and wellbeing of international students who remained in tertiary studies during the COVID-19 pandemic. The six consistently reported factors were identified and grouped based on the 4Ps model of case formulation across learning and psychosocial experiences. Predisposing factors for maladjustments included students being younger and possessing poor English proficiency. Precipitating factors were related to online teaching/learning and lack of accessibility to or insufficient learning and living resources. Perpetuating factors pertained to living arrangements, while protective factors included institutional support.

The findings of this integrative review highlighted multifaceted factors that affected the learning and mental wellbeing of international students during the COVID-19 pandemic. The predisposing and precipitating findings showed that moving online created a challenge, particularly with the language and the content, navigating the online medium, learning how to participate virtually, and the expectation to adapt and evolve with the changes [54]. The lack of staff consistency in online teaching [54] could be part of the reason why online teaching was reported to be detrimental to learning in different countries [10,11,26,36,50,53]. Contrary to the findings of our review, a Canadian study reported that international students enjoyed online learning compared to domestic students during the pandemic [55]. The reasons for this are unknown.

Precipitating the online connectivity challenges, our findings showed the capacity of students to maintain motivation to learn [12,36,50] and self-discipline [56]. One of the protective factors perceived by international students was that they felt supported by the lecturers and that the learning materials were well designed [12,28,36]. Chien-Yuan and Guo, 2021 [56] also reported that learner–content interaction had the most significant impact on students’ learning outcomes and satisfaction. Using breakout rooms gave the students an opportunity to interact and engage with other students, filling a void in social isolation experienced due to COVID-19 lockdown requirements [57,58]. Innovative interaction techniques were particularly evident in the simulation space when moving online. Clinical skills that involve auditory and visual training can be effectively imparted through digital tools, while those that depend on manual dexterity necessitate in-person practice for effective skill consolidation [59]. This aligned with our findings that healthcare students saw the value of face-to-face clinical placement in receiving high-value education and did not find simulated online learning to be beneficial [46]. There was a need for lecturers to develop innovative modes of teaching clinical skills online [57,60]. In medicine, virtual reality showed a simulation of real-life clinical experiences, and in midwifery, skills were demonstrated online, with the use of scripts as different partners in the midwife–woman dyad. Students played the roles in a group online session, ending in a plan of care being developed [57,60].

Not surprisingly, the learning challenges faced by international students were related to their mental health and wellbeing and were thematically similar. The factors are similar to the literature in countries such as the USA, Europe, and Asia. An Australian study described international students as being considered particularly vulnerable to experiencing poor mental health when studying away from their country of origin [61]. The paper suggested that this is reasonable, considering that students face new and varied academic and cultural challenges and that international university students had higher levels of depression compared to domestic students [62].

Our findings from the 38 papers found similar student experiences of mental well-being. Predominantly, the findings of this study show that students experienced loneliness and isolation from social contacts [6,30,35,39,48,51,52], although not specifically from family or friends. There were comments that isolation was linked to a loss of face-to-face class interaction [8,30,35,51], which is also supported by a Chinese study that found that resources should be appropriate for students’ varying levels of literacy [63]. Contrary to our expectations, an Australian study reported that domestic students were more lonely compared to international students during the COVID-19 pandemic [64]. This could be partly due to the findings that international students who received better social support during the COVID-19 pandemic adjusted better both academically and psychologically [48].

Of note, students were worried about their progression in the program of study, and this was reinforced by Hawley et al., 2021 [65], who highlighted that this was true for courses related to health sciences, where it was difficult to get practical skills while the teaching was online. This made the students feel inadequately trained and prepared in terms of sufficient employability skills for their discipline, which led to uncertainty about job prospects following the completion of their education, as companies had reduced the number of internships or new graduate positions [65].

Financial hardship is discussed in the literature as a barrier to mental wellness and includes literacy in navigating the health system [63]. This was not evident in our findings; however, we delved deeper to reveal that students were concerned with contracting COVID-19 from those who had tested positive [5,45]. Our data revealed that financial stress was associated with accommodation, whether it be living in a shared arrangement or alone, and that this was closely aligned with the inability to work due to the lockdown curfews or to get a reliable source of external revenue [5,9,30,45].

We found that many authors suggested varied resources, including libraries, flexible learning spaces, research facilities, and examination techniques [6,8,33]. This is similar to the opinion of Larcombe et al., 2023 [61] and Huang et al., 2020 [63], who claim institutions have a responsibility to provide learning support for this cohort and that this is a protective factor in preserving mental wellness. Huang et al., 2020 [63] also commented that universities could provide more cross-culture activities to enhance awareness of cultural diversity on campus. As students had no physical contact with family overseas and limited capability to communicate online [8,12,30,31,33,43,48], it is reasonable to suggest that institutions should provide reliable platforms to facilitate interaction with loved ones overseas.

The findings of this review have significance in practice, particularly given the ongoing challenges faced by international students nearly five years after the COVID-19 restrictions. While emergency measurements implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic have largely subsided, the persistence of hybrid learning models and the normalisation of online teaching highlights the continued need for support. For example, it is critical to provide support for international students, including easy access to and navigation of online teaching platforms or resources, such as workshops to orient students to the new online teaching technologies and resources; to establish and keep open lines of communication with students; to identify and develop student-friendly support resources for online teaching and learning technologies; to introduce student hubs with stocked computers on campus, especially when students have poor internet connectivity in their places of residence; to facilitate the establishment of student peer support systems for new and existing international students to reduce loneliness and isolation. Universities should establish student mental wellbeing clinics within campuses where students can access mental health services at no cost or at a small fee. Furthermore, international students should be supported in building resilience and equipped with the skills needed to manage future disruptions or uncertainties in their academic and personal lives. The findings of the review emphasise the importance of universities developing student-centred and inclusive support systems to effectively address sudden disruptions and ongoing challenges. Therefore, future research could focus on identifying and evaluating effective strategies that could help international students to maintain mental health and wellbeing.

5. Conclusions

This integrative review of research evidence offers a more holistic understanding of factors that influence international students’ learning experience and their mental health and wellbeing. It provides insightful evidence for policymakers to improve support for international students in learning and mental health during a pandemic such as COVID-19. Future research could be conducted with international students to achieve a better understanding of their coping strategies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.Z., F.K., E.L. and L.N.; Methodology, H.Z., F.K., A.N., E.L. and L.N.; Formal analysis, H.Z., A.N. and E.L.; Investigation, A.N. and E.L.; Data curation, F.K.; Writing—original draft, H.Z.; Writing—review and editing, F.K., A.N., E.L., X.-Y.H. and L.N.; Supervision, X.-Y.H. and L.N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author(s).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Vanessa Varis, Faculty Librarian, Faculty of Health Sciences, Curtin University, Western Australia, for her assistance with the literature search.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Agu, C.F.; Stewart, J.; McFarlane-Stewart, N.; Rae, T. COVID-19 pandemic effects on nursing education: Looking through the lens of a developing country. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2021, 68, 153–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van de Velde, S.; Buffel, V.; Bracke, P.; Van Hal, G.; Somogyi, N.M.; Willems, B.; Wouters, E. The COVID-19 international student well-being study. Scand. J. Public Health 2021, 49, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Kumaim, N.H.; Alhazmi, A.K.; Mohammed, F.; Gazem, N.A.; Shabbir, M.S.; Fazea, Y. Exploring the impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on university students’ learning life: An integrated conceptual motivational model for sustainable and healthy online learning. Sustainability 2021, 13, 2546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.D.; Lu, J.; Ni, L.; Hu, S.; Xu, Y. Psychological outcomes and associated factors among the international students living in China during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 707342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.R.; Kim, E.J. Factors associated with mental health among international students during the COVID-19 pandemic in South Korea. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 11381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Y.; Hu, D.; Liu, X. International doctoral students negotiating support from interpersonal relationships and institutional resources during COVID-19. Curr. Issues Comp. Educ. 2022, 24, 26–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoukat, S.; Callixte, C.; Nugraha, J.; Budhy, T.I.; Irene, T. Homesickness, anxiety, depression among Pakistani international students in Indonesia during COVID-19. ASEAN J. Psychiat. 2021, 22, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagroop-Dearing, A.; Leonard, G.; Shahid, S.M.; van Dulm, O. COVID-19 lockdown in New Zealand: Perceived stress and wellbeing among international health students who were essential frontline workers. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, J. COVID-19-related traumatic effects and psychological reactions among international students. J. Epidemiol. Glob. Health 2020, 11, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T.; Robinson, L.; Gledhill, K.; Peart, A.; Yu, M.L.; Isbel, S.; Greber, C.; Etherington, J. Online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: Comparing the perceptions of domestic and international occupational therapy students. J. Allied Healt. 2022, 51, 121–129. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Q.; Horta, H.; Yuen, M. International medical students’ perspectives on factors affecting their academic success in China: A qualitative study. BMC Med. Educ. 2022, 22, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Su, H.; Liao, Z.; Qiu, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, J.; Pei, Y.; Jin, P.; Xu, J.; Qi, C. Gender differences in mental health disorder and substance abuse of Chinese international college students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 710878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sidhu, R.; Cheng, Y.E.; Collins, F.; Ho, K.C.; Yeoh, B. International student mobilities in a contagion: (Im)mobilising higher education? Geogr. Res. 2021, 59, 313–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, J.A.; Cabarkapa, S.; Leow, F.H.P.; Ng, C.H. Addressing international student mental health during COVID-19: An imperative overdue. Australas. Psychiatry. 2020, 28, 469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, C.; Del Fabbro, L.; Shaw, J. The acculturation, language and learning experiences of international nursing students: Implications for nursing education. Nurse Educ. Today 2017, 56, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vardaman, S.A.; Mastel-Smith, B. The transitions of international nursing students. Teach. Learn. Nurs. 2016, 11, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslan, H.; Pekince, H. Nursing students’ views on the COVID-19 pandemic and their perceived stress levels. Perspect Psychiatr. Care 2020, 57, 695–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, H.L.; Doherty, A.Z.; Obonyo, M. International student experiences in Queensland during COVID-19. Int. Soc. Work. 2020, 63, 815–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckstein, A. The Student: How Are International Students Coping with the COVID-19 Pandemic? Times Higher Education: London, UK, 2020. Available online: https://www.timeshighereducation.com/student/blogs/how-are-international-students-coping-covid-19-pandemic (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- Whittemore, R.; Knafl, K. The integrative review: Updated methodology. J. Adv. Nurs. 2005, 52, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torraco, R.J. Writing integrative literature reviews: Guidelines and examples. Hum. Resour. Dev. Rev. 2005, 4, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Q.N.; Pluye, P.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M.-P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; et al. Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), Version 2018. Registration of Copyright (#1148552); Canadian Intellectual Property Office, Industry Canada: Gatineau, QC, USA, 2018; Available online: http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/127916259/MMAT_2018_criteria-manual_2018-08-01_ENG.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- Engel, G.L. The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science 1977, 196, 129–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdul-Rahaman, N.; Terentev, E.; Arkorful, V.E. COVID-19 and distance learning: International doctoral students’ satisfaction with the general quality of learning and aspects of university support in Russia. Public Organ. Rev. 2022, 23, 703–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Oraibi, A.; Fothergill, L.; Yildirim, M.; Knight, H.; Carlisle, S.; O’Connor, M.; Briggs, L.; Morling, J.R.; Corner, J.; Ball, J.K.; et al. Exploring the Psychological Impacts of COVID-19 Social Restrictions on International University Students: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brownlow, C.; Eacersall, D.; Nelson, C.W.; Parsons-Smith, R.L.; Terry, P.C. Risks to mental health of higher degree by research (HDR) students during a global pandemic. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0279698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, F.; Hwang, Y.; Hodgson, N.A. Relationships between racial discrimination, social isolation, and mental health among international Asian graduate students during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Am. Coll. Health 2022, 72, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erden, G.; Özdoğru, A.A.; Coksan, S.; Ögel-Balaban, H.; Azak, Y.; Altinoğlu-Dikmeer, I.; Ergul-Topcu, A.; Yasak, Y.; Kiral-Ucar, G.; Oktay, S.; et al. Academic satisfaction, covid-19 knowledge, and subjective well-being among students at Turkish universities: A nine-university sample. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2022, 17, 2017–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.; Tong, Y.; Bai, Y.; Zhao, Z.; Quan, W.; Liu, Z.; Wang, J.; Song, Y.; Tian, J.; Dong, W. Prevalence and correlates of depression and anxiety among Chinese international students in US colleges during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0267081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, L.; Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Guo, X.; Pan, B. Association of COVID-19 pandemic-related stress and depressive symptoms among international medical students. BMC Psychiatry 2022, 22, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kivelä, L.; Joanne Mouthaan, J.; van der Does, W.; Antypa, N. Student mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: Are international students more affected? J. Am. Coll. Health 2022, 72, 414–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mbous, Y.P.V.; Mohamed, R.; Rudisill, T.M. International students challenges during the COVID-19 pandemic in a university in the United States: A focus group study. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 4, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nadareishvili, I.; Syunyakov, T.; Smirnova, D.; Sinauridze, A.; Tskitishvili, A.; Tskitishvili, A.; Zhulina, A.; Patsali, M.E.; Manafis, A.; Fountoulakis, N.K.; et al. University students’ mental health amidst the COVID-19 pandemic in Georgia. Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2022, 68, 1036–1046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Wu, Z.; Qu, X.; Liu, Y.; Peng, L.; Ge, Y.; Li, S.; Du, J.; Tang, Q.; Wang, J.; et al. Influencing factors of international students’ anxiety under online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study of 1090 Chinese international students. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 860289. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, M.; Lu, G. Online learning satisfaction and its associated factors among international students in China. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 916449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tozini, K.; Castiello-Gutiérrez, S. COVID-19 and international students: Examining perceptions of social support, financial well-being, psychological stress, and university response. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 2022, 63, 134–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahorsu, D.K.; Pramukti, I.; Strong, C.; Wang, H.; Griffiths, M.D.; Lin, C.; Ko, N. COVID-19-Related Variables and Its Association with Anxiety and Suicidal Ideation: Differences Between International and Local University Students in Taiwan. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2021, 14, 1857–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almomani, E.Y.; Qablan, A.M.; Almomany, A.M.; Atrooz, F.Y.; Sullivan, J. The coping strategies followed by university students to mitigate the COVID-19 quarantine psychological impact. Curr. Psychol. 2021, 40, 5772–5781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, A.Y.; Sit, S.M.; Lam, S.K.; Choi, A.C.; Yiu, D.Y.; Lai, T.T.; Ip, M.S.; Lam, T.H. A phenomenological study on the positive and negative experiences of Chinese international university students from Hong Kong studying in the U.K. and U.S. in the early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 738474. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lai, A.Y.; Sit, S.M.; Lai, T.T.; Wang, M.P.; Kong, C.H.; Cheuk, J.Y.; Feng, Y.; Ip, M.S.; Lam, T.H. Facemask wearing among Chinese international students from Hong Kong studying in United Kingdom universities during COVID-19: A mixed method study. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 673531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leshchyna, I.V.; Asieieva, Y.O.; Vasylieva, O.V.; Strelnikova, I.M.; Kovalska, N.A. Adjustment disorders in international students studying in English during a pandemic. Rev. Amazon Investig. 2021, 10, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Gillies, R.; He, M.Y.; Wu, C.H.; Liu, S.J.; Gong, Z.; Sun, H. Barriers and facilitators to online medical and nursing education during the COVID-19 pandemic: Perspectives from international students from low- and middle-income countries and their teaching staff. Hum. Resour. Health 2021, 19, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, K.; Li, Y.; Liu, S.; Li, C. Psychological distress and trust in university management among international students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychyol. 2021, 12, 679661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negash, S.; Kartschmit, N.; Mikolajczyk, R.T.; Watzke, S.; Matos Fialho, P.M.; Pischke, C.R.; Busse, H.; Helmer, S.M.; Stock, C.; Zeeb, H.; et al. Worsened financial situation during the COVID-19 pandemic was associated with depressive symptomatology among university students in Germany: Results of the COVID-19 international student well-being study. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 743158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trzcionka, A.; Zalewska, I.; Tanasiewicz, M. Interpretative phenomenological analysis for the comparison of Polish and foreign dentistry students’ concerns during the COVID-19 pandemic. Healthcare 2021, 9, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B. Time, temporality, and (im)mobility: Unpacking the temporal experiences among Chinese international students during the COVID-19. Popul. Space Pace. 2022, 28, e2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilczewski, M.; Gorbaniuk, O.; Giuri, P. The psychological and academic effects of studying from the home and host country during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 644096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, L.L.; Lu, L.; Wang, X.H.; Guo, X.X.; Ren, H.; Gao, Y.Q.; Pan, B.C. Prevalence and predictors of anxiety and depressive symptoms among international medical students in China during COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 761964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chirikov, I.; Soria, K.M. International Students’ Experiences and Concerns During the Pandemic. SERU Consortium, University of California, Berkeley and University of Minnesota. 2020. Available online: https://escholarship.org/content/qt43q5g2c9/supp/International_Students__Experiences_and_Concerns.pdf (accessed on 1 July 2024).

- Lai, A.Y.; Lee, L.; Wang, M.P.; Feng, Y.; Lai, T.T.; Ho, L.M.; Lam, V.S.; Ip, M.S.; Lam, T.H. Mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on international university students, related stressors, and coping strategies. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 11, 584240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Lu, L.; Wang, X.; Qu, M.; Yuan, L.; Gao, Y.; Pan, B. Relationships between cross-cultural adaption, perceived stress and psychological health among international undergraduate students from a medical university during the COVID-19 pandemic: A moderated mediation model. Front. Psychiatry 2020, 12, 783210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Q.; He, Y.J.; Zhu, Y.H.; Dai, M.C.; Pan, M.M.; Wu, J.Q.; Zhang, X.; Gu, Y.E.; Wang, F.F.; Xu, X.R.; et al. The evaluation of online course of Traditional Chinese Medicine for MBBS international students during the COVID-19 epidemic period. Integr. Med. Res. 2020, 9, 100449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, A.A.; Zarb, M.; Anderson, E.; Crane, B.; Gao, A.; Latulipe, C.; Lovellette, E.; McNeill, F.; Meharg, D. The impact of COVID-19 on the CS student learning experience: How the pandemic has shaped the educational landscape. In Proceedings of the 2022 Working Group Reports on Innovation and Technology in Computer Science Education, Dublin, Ireland, 8–13 July 2022; pp. 165–190. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L. Moving forward: International students’ perspectives of online learning experience during the pandemic. Int. J. Educ. Res. 2023, 5, 100276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chien-Yuan, S.; Guo, Y. Factors impacting university students’ online learning experiences during the COVID-19 epidemic. J. Comput. Assist. Learn. 2021, 37, 1578–1590. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, P.A.; Girgis, C.; Rustad, J.K.; Noordsy, D.; Stern, T.A. Advancing Medical Education Through Innovations in Teaching During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Prim. Care Companion CNS Disord. 2021, 23, 20nr02847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakha, A.H. The impact of Blackboard Collaborate breakout groups on the cognitive achievement of physical education teaching styles during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0279921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, A.; Forde, C. Health science staff and student experiences of teaching and assessing clinical skills using digital tools: A qualitative study. Ann. Med. 2023, 55, 2256656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradford, H.M.; Farley, C.L.; Escobar, M.; Heitzler, E.T.; Tringali, T.; Walker, K.C. Rapid curricular innovations during COVID-19 clinical suspension: Maintaining student engagement with simulation experiences. J. Midwifery Women’s Health 2021, 66, 366–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larcombe, W.; Ryan, T.; Baik, C. Are international students relatively resilient? Comparing international and domestic students’ levels of self-compassion, mental health and wellbeing. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2023, 43, 362–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravanan, C.; Subhashini, G. A systematic review on the prevalence of depression and its associated factors among international university students. Curr. Psychiatry Rev. 2021, 17, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Kern, M.L.; Oades, L.G. Strengthening university student wellbeing: Language and perceptions of Chinese international students. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 5538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingle, G.; Han, R.; Carlyle, M. Loneliness, belonging, and mental health in Australian university students pre- and post-COVID-19. Behav. Change 2022, 39, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawley, S.R.; Thrivikraman, J.; Noveck, N.; Romain, T.S.; Ludy, M.; Barnhart, L.; Chee, W.S.; Cho, M.J.; Chong, M.H.; Du, C.; et al. Concerns of college students during the COVID-19 pandemic: Thematic perspectives from the United States, Asia, and Europe. J. Appl. Learn. Teach. 2021, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).