Abstract

Scaling up effective interventions in public health is complex and comprehensive, and published accounts of the scale-up process are scarce. Key aspects of the scale-up experience need to be more comprehensively captured. This study describes the development of a guide for reflecting on and documenting the scale-up of public health interventions, to increase the depth of practice-based information of scaling up. Reviews of relevant scale-up frameworks along with expert input informed the development of the guide. We evaluated its acceptability with potential end-users and applied it to two real-world case studies. The Scale-up Reflection Guide (SRG) provides a structure and process for reflecting on and documenting key aspects of the scale-up process of public health interventions. The SRG is comprised of eight sections: context of completion; intervention delivery, history/background; intervention components; costs/funding strategies and partnership arrangements; the scale-up setting and delivery; scale-up process; and evidence of effectiveness and long-term outcomes. Utilization of the SRG may improve the consistency and reporting for the scale-up of public health interventions and facilitate knowledge sharing. The SRG can be used by a variety of stakeholders including researchers, policymakers or practitioners to more comprehensively reflect on and document scale-up experiences and inform future practice.

1. Introduction

Effective health interventions should be scaled up to achieve population-wide benefits [1,2]. The process of ‘scale-up’ or ‘scaling up’ is commonly referred to as “deliberate efforts to increase the impact of successfully tested health interventions so as to benefit more people and to foster policy and program development on a lasting basis” [2]. In the area of health promotion and chronic disease prevention, many interventions are demonstrated to be effective, but are infrequently scaled up or disseminated for wider use [3,4,5]. While various frameworks provide guidance on the optimal steps for scaling up [2,6,7], real-world examples demonstrate that the scale-up occurs through a variety of pathways commonly influenced by the social-political implementation context, resources available for at-scale delivery, and key actors to guide the scale-up process [8,9,10,11,12].

The scientific literature on scale-up consists predominantly of frameworks on ‘how to’ scale up interventions [6,7,13,14], implementation strategies [15,16] and tools for deciding whether an intervention is appropriate or ready for scaling up [17,18]. Many papers on scale-up also describe facilitators and barriers to scale-up [9,19,20], but information on funding, partnership arrangements, delivery mechanisms and decision-making processes from real-world experiences of scale-up is usually absent or inconsistently reported [21]. This limits learning opportunities to inform future scale-up efforts despite calls to improve this reporting process [4,9,22,23,24]. While some descriptions of scale-up may be found in the grey literature, such as government databases or reports, they often lack standardized information to inform replicability [12,25,26,27]. In the peer-reviewed literature in the area of health promotion and chronic disease prevention, such as physical activity or nutrition interventions specifically, publications of scale-up efforts tend to focus on the development and design of the intervention, its characteristics, and results of interventions rather than the processes and context of disseminating and scaling up the intervention [28].

Formal guidance already exists for reporting on a variety of study types, including randomized controlled trials (CONSORT) [29,30], observational or qualitative studies [31,32,33], which facilitates improvements in reporting to enable better appraisal of the quality of the studies while assisting readers to determine applicability to their own context. A similar process for documenting case studies of scale-up has been identified as a gap in the current scale-up literature [25,34,35,36]. Case studies support effective scale-up of health interventions, as they provide an opportunity for rich description of the process of scaling up across various contexts. For this reason, the development of a ‘guide’ for reflecting on and documenting scale-up would be a valuable contribution and may facilitate the development of such case studies [35,37,38].

The purpose of this study was to develop a ‘guide’ for reflecting on and documenting the scale-up of health promotion and chronic disease prevention interventions to aid practitioners, policymakers and researchers undertaking future projects. The new ‘Scale-up Reflection Guide’ includes all important aspects of scale-up that will facilitate more detailed reporting of scale-up experiences to better capture lessons learned. This is critical for building a repository of knowledge to aid replication, understanding, synthesis and learning from previous attempts of scale-up for improving scale-up practices in the future.

In this study, we used health promotion and chronic disease prevention interventions as exemplars to demonstrate the utility of the ‘guide’.

2. Materials and Methods

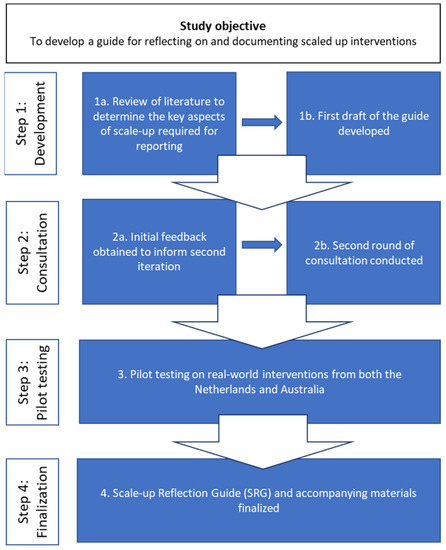

The development of the Scale-up Reflection Guide (SRG) was an iterative process and comprised (1) reviewing literature, (2) consulting with experts and (3) pilot-testing the guide prior to (4) finalisation. The process is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Key steps to developing the Scale-up Reflection Guide.

- Step 1: Development

We conducted a narrative review to assess current guidance in the literature for developing guidance or case studies in scale-up and, in absence of that, to identify broad scale-up frameworks to identify the key components required for documenting scale-up experiences. The narrative review was conducted over two phases. Firstly, a keyword search of the literature published in English between January 2000–December 2019 was conducted in the OVID MEDLINE database. Two separate search strings were performed separately and subsequently combined. The first search string included the key search terms ‘Case study’ AND [‘Framework’ OR ‘Guide’ OR ‘Checklist’ OR ‘Process model’ OR ‘Tool’] AND [‘Scale-up’ OR ‘Scaling up’]. The second search string included the terms [‘Scale-up’ OR ‘Scaling up’] AND [‘Case study’ OR ‘Framework’ OR ‘Guide’ OR ‘Checklist’ OR ‘Process model’ OR ‘Tool’].

The narrative review was designed by K.L. and M.C., and the abstracts were retrieved and assessed for relevance by K.L. Abstracts were included for full paper review if they met the following inclusion criteria: being published in peer-reviewed literature in English between 2000–2019; providing guidance for developing case studies in scale-up; and describing frameworks, process models, guides or tools associated with scaling-up interventions.

Full papers were retrieved, and relevant papers were assessed independently by two of the authors, K.L. and M.C. Frameworks, guides, tools, process models or checklists were included for further inclusion only if they specified steps or stages to guide the process of scaling up interventions into practice [39] and were applicable to a broad range of health promotion and chronic disease prevention interventions.

Papers on developing case studies were included if they provided specific instruction on the content or process required for collecting and reporting on experiences of scale-up.

Papers were excluded if they described: scale-up and/or evaluation of specific interventions without guidance on how to report scale-up experiences; facilitators and/or barriers to scale-up within a specific intervention or general experiences of scale-up without any framework for guidance; general conceptual issues relating to scale-up; study protocols for potential or existing scale-up; scale-up of biomedical or pharmacological procedures or services and/or medical information technology systems; assessments of readiness for scale-up or scalability; or implementation studies (describing implementation trials and not scale-up).

In addition to the review of the scientific literature, an open keyword search in the Google search engine was conducted, and the results of this search were scanned for relevant articles in accordance with guidance on grey literature searches [40].

- Step 2: Consultation

Following the identification of relevant literature, the key concepts from each of the eligible frameworks were extracted and collated by K.L., M.C. and F.v.N. An initial draft of the guide was generated and revised and refined in discussion with the other co-authors as academic experts in implementation and scale-up.

Next, a purposive sample of external experts with academic and policy/practice-based experience of scaling up health interventions (n = 4) specifically in the area of health promotion and chronic disease prevention were identified through professional networks in Australia and the Netherlands for further consultation to identify any gaps or areas for improvement as well as to ascertain potential usefulness for users. The consultations in Australia were conducted by K.L. and M.C., and in the Netherlands by F.v.N. A brief topic guide with question prompts was developed to guide the consultations but was employed flexibly to allow for the consultation to be responsive to the respondents. Responses to the question prompts were audio-recorded, and written notes were also taken. Following the consultations, the audio recordings and notes were reviewed and discussed by authors K.L. and F.v.N, and proposed amendments, as suggested through the consultations, were raised with all co-authors, and any changes to the SRG were reached in consultation with and agreed to by all.

- Step 3: Pilot testing

Following consultations, the revised SRG was piloted on two real-world examples of scaled-up interventions (Step 3, Figure 1), one from Australia (Get Healthy) and one from the Netherlands (Dutch Obesity Intervention in Teenagers (DOiT)). We selected these interventions, as they target NCD interventions and settings with diverse scale-up processes. The pilot also examined the practical issues in completing the SRG.

- Step 4: Finalisation

Following the pilot testing, minor amendments were made based on the pilot experience, and all the SRG and its accompanying materials were finalised.

3. Results

- Step 1a: Results of narrative and grey literature review

The initial search in OVID MEDLINE with the search terms and search term combinations yielded a total of n = 1246 abstracts and an additional n = 5 through grey literature. Following the removal of duplicates (n = 59), there were a total of n = 1192 abstracts to be reviewed as part of Phase 1 (See Supplementary File S1).

Following assessment against review criteria, a further n = 1149 were excluded. Forty-three full papers and reports were reviewed against the inclusion criteria for Phase 2. From this, 26 papers were excluded, as eight of them described facilitators of and barriers to scale-up, while a further six described the scale-up of specific interventions, and the remainder either discussed conceptual components of scale-up (n = 4), provided assessments of readiness for scale-up (n = 3), described the implementation of an intervention (n = 1) or pathways for scale-up (n = 1), provided a framework to plan for scale-up (n = 1) or articulated a knowledge translation model, within which scale-up was flagged as a step (n = 1). One article provided guidance for reporting on interventions for publication but was not specific to scale-up and was therefore excluded.

- Step 1b: Development of the initial Scale-up Reflection Guide (SRG)

From the review of peer-reviewed and grey literature (n = 17), we identified scale-up process frameworks (n = 14) and one report providing guidance on how to document scale-up case studies [12]. The remaining n = 2 papers [19,41] presented results of their own reviews of scale-up frameworks and provided an additional four frameworks not identified in this literature search.

Upon detailed review of each of these 18 scale-up frameworks and one case study guidance, seven were applicable to a broad range of public health interventions and were deemed useful for developing the key components of the SRG (see Supplementary File S2). Of the remaining frameworks, three were frameworks for determining the scalability or implementation of an intervention rather than providing a process for scale-up, and one was a review of scale-up case studies in physical activity. The remaining eight frameworks were designed for the scale-up of interventions targeting specific conditions, such as HIV or maternal and child health or health technologies.

Other frameworks that focused on implementation outcomes [15,16], sustainability [42,43] or adaptation [44,45,46] were not examined in detail but contributed to supporting information about elements of the guide (see Supplementary File S3).

The one paper that provided guidance on case studies for scale-up did not present a structure or framework for the development of the case study; rather, it posed a series of 20 questions that the author believed any scale-up case study needs to answer [12]. These questions were taken into consideration along with the remaining six frameworks that proposed similar sequential steps for scale-up [2,6,7,11,14,47]. There was considerable agreement on the important aspects influencing scale-up, such as intervention, context, decisions for scaling up, service delivery, scale-up workforce, scale-up and implementation strategy, monitoring and evaluation, facilitators and barriers and sustainability (Table 1). Four frameworks included all nine aspects [2,6,7,14], and the remaining two included seven [11] or eight [47] (Table 1). The twenty questions posed by the scale-up case study guide encompassed all the aspects identified in Table 1.

Table 1.

Common aspects of scale-up across frameworks.

Key explanations underpinning these nine common aspects of scale-up across the frameworks were also identified (Table 2). These provide clarification of the different aspects of scale-up and identified additional concepts or activities that relate to those aspects. These nine aspects were used to guide the basis of the development of the final SRG (Table 3).

Table 2.

Common aspects of scale-up.

Table 3.

Scale-up Reflection Guide sections with a description of the types of information required.

- Step 2: Consultations

Of the four advisors consulted, three classified themselves as fulfilling dual roles as policymakers and academics, and one was involved directly in scale-up as a policymaker at the community level in the area of health promotion and chronic disease prevention. The consultations with scale-up experts indicated that, first, there needed to be greater emphasis on documenting adaptations and/or modifications to the intervention and processes for scale-up over time [7]. Second, the different costs associated with scale-up as well as any financial resources made available for scale-up and delivery should be reported separately. Finally, it was recommended that the specific target population for the intervention be clearly described, along with descriptions of the implementation process and scale-up process.

- Step 3: Pilot Testing

Following revision, the SRG was tested on two real-world health promotion and chronic disease prevention interventions that had already been scaled up in the Netherlands and Australia independently by authors K.L. and F.v.N. As the aim of this pilot was to test the utility of the SRG, both authors collated the information for each of these real-world interventions based on a range of publicly available and internal documents on the interventions. The ease of completion of the SRG relating to its sense, format and structure, given the available information on each intervention, was particularly examined. As a result of this testing, minor amendments were made to the format and structure of the SRG to improve the user experience (Step 4, Figure 1). Both authors noted that the information required to complete all sections of the SRG was readily available through both public sources and internal documents for the interventions. The content generated for each intervention is provided in Supplementary File S4.

- Step 4: Finalization

- The Scale-Up Reflection Guide (SRG)

In this section, we provide a structure of how a reflection and documentation of a scale-up experience could be organised (Table 3), followed by suggested steps on how to complete it. The table below provides the detailed sections contained in the “SRG” along with a description of the information required for each of the elements in the section. The rationale for the inclusion of each of the key sections and related elements can be found in Supplementary File S3.

- Suggested activities to complete the SRG

The SRG has been designed for a range of users such as researchers, policymakers or practitioners who may have different purposes for completing the SRG. For some, they may want to learn about the scale-up of similar interventions and would complete the SRG by researching a range of information sources on the intervention. Those directly involved in the scale-up process of an intervention may use the SRG to reflect on and document their own experiences for the purposes of developing a case study for publication or reporting. Given the potential diversity in users and/or purposes, we have outlined below some proposed activities for completing the SRG. We recognise that the process is not linear and that the activities are not mutually exclusive. Depending on who is completing the SRG, it is likely that there may be varying levels of familiarity with the intervention which may influence the completeness of the SRG. We have included some suggestions for additional data collection to assist those completing the SRG if they have not been closely involved in the actual scale-up, or where there is limited information about the program that is publicly available.

- Activity 1: Collation and review of existing evidence/information and gap analysis of first draft

The purpose of Step 1 is to collate and review available information on the intervention being documented. Examples of data sources to locate such information include: peer-reviewed publications, conference proceedings; publicly available reports, factsheets, annual reports and/or other internal publications; online sources including intervention or relevant government websites; financial/budget reports and/or personal communication with relevant program managers/organisations.

For interventions still in operation, current information may be gathered from websites and program reports. Where an intervention has ceased, historical information may be more challenging to locate. Information gaps revealed through this process may then require additional data to be collected.

- Activity 2: Additional data collection to fill in the gaps

Planning for additional data collection may involve conducting interviews with stakeholders such as program managers/leaders, organisations or researchers who were involved during the formative development and decision-making of the intervention or implementation and scale-up process. Table 3 could be adapted to form an interview guide.

- Activity 3: Review, report and disseminate findings

Following the additional data collection and information review, dissemination strategies for the completed SRG may include the production of the SRG as a case study or publishing the SRG findings in peer-reviewed journals, websites or external or internal reports to summarise key learning. SRG findings may also be fed back to the relevant stakeholders involved in the process to improve their understanding of the scale-up experience as a whole.

4. Discussion

The SRG developed in this study addresses a gap in the literature on implementation and scale-up in health promotion and chronic disease prevention by which researchers, policymakers and practitioners may capitalise on previous scale-up experience to guide future practice. With few articles describing the entire experience and lessons learned from the process of scaling up public health interventions under real-world conditions, there is a need to document these well and to share experiences and lessons to reduce duplication of ineffective methods and also to reduce the need to ‘reinvent the wheel’ [36]. Building on existing scale-up models, the SRG provides a structure to facilitate comprehensive capture of key information regarding the scale-up of an intervention in one document.

The SRG provides pilot-tested steps supporting its use and encourages the use of a range of credible information sources alongside multiple perspectives. Through the experience of pilot-testing the SRG it is recommended that the SRG should be completed by those with knowledge of the intervention and its scale-up, including program managers or members of the scale-up team with input from the delivery workforce, it is recognised that this may not always be possible. This is because the information to comprehensively complete the SRG may not be always be publicly available, and those with indirect experience and/or knowledge of the scale-up may be limited in their ability to reflect on the scale-up process. Nevertheless, pilot-testing the SRG on two scaled-up real-world interventions has demonstrated the utility of the SRG to comprehensively capture the information on the process of scale-up and adaptation of real-world interventions that is missing from current frameworks and guides.

Although the SRG was designed for reporting on the scale-up of interventions retrospectively, another advantage of this SRG, if used prospectively, is that it could potentially inform the stages of scaling up and reporting as they occur and could comprise part of the process evaluation of the intervention.

As the processes of scaling up of health promotion interventions vary considerably across different contexts and may follow a variety of pathways [10], documenting key steps and understanding the differences in delivery settings and the scale-up context will provide lessons for other similar interventions that are to be scaled [35]. Comprehensive documentation may reveal hitherto unrecognised strengths and weaknesses of different scale-up approach contexts under real-world conditions. Incorporating information on the process of adaptation on the intervention over time will further provide important contextual information to understand what may have led to intervention sustainment or cessation.

The development of a publicly available shared repository to store outputs of the SRG such as case studies would further enhance the value of the SRG [34]. Centralised web repositories of descriptions of interventions, such as the Evidence-Based Cancer Control Programs (EBCCP), have supported the selection of the effective interventions to address a range of chronic disease prevention programs [56]. While this and other online repositories in the USA [57] and the Netherlands [58] have also been developed to support public health decision-making broadly, none, to our knowledge, have been designed to capture and catalogue scale-up experiences. The SRG could serve as a structured guide to facilitate a standardised approach to developing scale-up case studies suitable for collation into an easily accessible repository [25,59].

Limitations

The SRG was designed to be a pragmatic tool to reflect on and document experiences of scaling up interventions in the area of health promotion and chronic disease prevention, illustrated with physical activity and nutrition examples, though we believe its application could be broader to capture interventions across a broad spectrum of other health interventions. As a targeted approach to the literature was used, some aspects of the scale-up process could have been missed. To overcome this and to strengthen the validity of the SRG, we consulted with scale-up experts and pilot-tested the instrument with real-world interventions that were scaled up. However, we recognise that they too were limited in number. The next step would be more extensive testing in the real world and its practical application within the wider health and human services context.

Another acknowledged limitation of the SRG is that it may describe individual change interventions delivered at scale. It is meeting the expressed needs of real-world practitioners interested in scaling up their programs to reach wider populations, and the SRG will assist users in understanding why scale-up may not have worked. This is a similar research goal to our Intervention Scalability Assessment Tool (ISAT) [18], which is a tool for organisations and governments planning scaling-up interventions and provides guidance to assess the feasibility and readiness to go to scale. The SRG is a reactive tool and is not designed to assess different implementation approaches. It is standardised and therefore is not as in-depth as realist evaluations but will provide information that is comparable across scaled-up interventions.

Although our scale-up examples may be from single interventions, they can have real population-wide reach and can access hard-to-reach population groups [60,61]. Although this is not a whole-system intervention, it described programs that are major public health improvements on the myriad published programs of program effectiveness that only reach small volunteer samples. We recognise several limitations of this approach, including the effect sizes being attenuated when efficacious programs are delivered at scale [5,28]. Further, we acknowledge that we do not consider coding the upstream determinants of scale-up in the SRG, including social and political determinants, commercial determinants and influencers, and even transnational influences [62]. Nor will the SRG solve all the cross-sectoral partnerships needed to solve complex problems [63]. However, the upstream research to understand population health remains a complex contested field. Although there is a need for research integration between policy implementation research and implementation science [39], our evaluative approach provides a quite different and pragmatic approach to support health promotion and chronic disease prevention practice in real time. Our scale-up work and this SRG provides more immediate engagement to influence practice in real time.

5. Conclusions

The imperative to scale up effective interventions to achieve population-wide reach and impact has led to some advances in knowledge of how to scale up [11,64] in the area of health promotion and chronic disease prevention. However, in order to fully understand scale-up in real-world conditions, there needs to be a standardized approach to documenting the processes that underpin the development of the intervention, the intervention context, and its interaction with intervention implementation and from a variety of perspectives [35]. The SRG provides a structure and framework to reflect on and document scale-up experiences, which will improve comparisons and analysis of techniques, contexts and solutions to widespread dissemination of programs for population impact [35].

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijerph20116014/s1, Figure S1: Literature Review results; Table S1: Summary of scale-up process frameworks identified and inclusion/exclusion status; Table S2: Scale-up Reflection Guide rationale; Case studies S1: Two completed examples of scale-up using the Scale-up Reflection Guide. References [65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79] are mentioned in Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

K.L. conducted the literature review and the analysis of frameworks. K.L., M.C. and F.v.N. developed the guide, conducted the consultations, developed the manuscript and completed the examples. K.L. led the writing of the final manuscript. All other authors (A.G., B.O., A.M., L.W. and A.B.) contributed to reviewing and approving the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by The Australian Prevention Partnership Centre through the NHMRC partnership centre grant scheme (Grant ID: GNT9100003) with the Australian Government Department of Health, ACT Health, Cancer Council Australia, NSW Ministry of Health, Wellbeing SA, Tasmanian Department of Health, and VicHealth. It is administered by the Sax Institute.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethics approval for this study was obtained from the University of Sydney’s Human Research Ethics Committee Protocol No 2019/537 and the Medical Ethics Review Committee of VU University Medical Center (2019.497).

Informed Consent Statement

All stakeholders interviewed gave written and/or verbal informed consent for the consultations to be recorded and/or transcribed and used for research purposes. All consultation notes were de-identified for analysis and reporting.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The research team would like to acknowledge the following for their contributions to the development of the guide along with their expert input into the examples: Fanny Cheng, Diedona Vorfi, Oumaima Omoussa, Nicole Nathan, Rachel Sutherland, Chris Rissel, Evelien de Boer and Vincent Busch.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

References

- Milat, A.; King, L.; Bauman, A.; Redman, S. The concept of scalability: Increasing the scale and potential adoption of health promotion interventions into policy and practice. Health Promot. Int. 2013, 28, 285–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organisation, Nine Steps for Developing a Scaling-Up Strategy, 2010. Available online: http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/strategic_approach/9789241500319/en/ (accessed on 20 January 2020).

- Naylor, D.; Girard, F.; Mintz, J.; Fraser, N.; Jenkins, T.; Power, C. Unleashing Innovation: Excellent Healthcare for Canada: Report of the Advisory Panel on Healthcare Innovation, 2015. Available online: https://healthycanadians.gc.ca/publications/health-system-systeme-sante/report-healthcare-innovation-rapport-soins/alt/report-healthcare-innovation-rapport-soins-eng.pdf (accessed on 31 August 2020).

- Ben Charif, A.; Zomahoun, H.; LeBlanc, A.; Langlois, L.; Wolfenden, L.; Yoong, S.; Williams, C.M.; Lépine, R.; Légaré, F. Effective strategies for scaling up evidence-based practices in primary care: A systematic review. Implement. Sci. 2017, 12, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, C.; McCrabb, S.; Nathan, N.; Naylor, P.-J.; Bauman, A.; Milat, A.; Lum, M.; Sutherland, R.; Byaruhanga, J.; Wolfenden, L. How effective are physical activity interventions when they are scaled-up: A systematic review. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2021, 18, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milat, A.; Newson, R.; King, L. Increasing the Scale of Population Health Interventions: A Guide; Evidence and Evaluation Guidance Series; NSW Ministry of Health: Sydney, Australia.

- Cooley, L.; Kohl, R.; Ved, R. Scaling Up—From Vision to Large Scale Change: A Management Framework for Practitioners; Management Systems International: Arlington, VA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Milat, A.J.; King, L.; Newson, R.; Wolfenden, L.; Rissel, C.; Bauman, A.; Redman, S. Increasing the scale and adoption of population health interventions: Experiences and perspectives of policy makers, practitioners, and researchers. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2014, 12, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, W.; Mittman, B. Scaling-Up Health Promotion/Disease Prevention Programs in Community Settings: Barriers, Facilitators and Initial Recommendations; Report Submitted to the Patrick and Catherine Weldon Donaghue Medical Research Foundation; The Patrick and Catherine Weldon Donaghue Medical Research Foundation: West Hartford, CT, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Indig, D.; Lee, K.; Grunseit, A.; Milat, A.; Bauman, A. Pathways for scaling up public health interventions. BMC Public Health 2018, 18, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamey, G. Scaling up global health interventions: A proposed framework for success. PLoS Med. Public Libr. Sci. 2011, 8, e1001049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajans, P.; Ghiron, L.; Kohl, R.; Simmons, R. 20 Questions for developing a scaling up case study. Manag. Syst. Int. 2007. Available online: https://www.expandnet.net/PDFs/MSI-ExpandNet-IBP%20Case%20Study%2020%20case%20study%20questions.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2020).

- World Health Organisation ExpandNet. Pracical Guidance for Scaling Up Health Service Innovations, 2009. Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44180/9789241598521_eng.pdf;jsessionid=F4BCDBE30D12C3EE031541604E8CE7BE?sequence=1 (accessed on 25 January 2020).

- Simmons, R.; Shiffman, J. Scaling up health service innovations: A framework for action. In Scaling Up Health Service Delivery; Simmons, R., Ghiron, L., Eds.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Damschroder, L.; Aron, D.; Keith, R.; Kirsh, S.; Alexander, J.; Lowery, J. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement. Sci. 2009, 4, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durlak, J.; DuPre, E. Implementation matters: A review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2008, 41, 327–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koorts, H.; Eakin, E.; Estabrooks, P.; Timperio, A.; Salmon, J.; Bauman, A. Implementation and scale up of population physical activity interventions for clinical and community settings: The PRACTIS guide. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2018, 15, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milat, A.; Lee, K.; Conte, K.; Grunseit, A.; Wolfenden, L.; van Nassau, F.; Orr, N.; Sreeram, P.; Bauman, A. Intervention Scalability Assessment Tool: A decision support tool for health policy makers and implementers. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2020, 18, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milat, A.; Bauman, A.; Redman, S. Narrative review of models and success factors for scaling up public health interventions. Implement. Sci. 2015, 10, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bulthuis, S.; Kok, M.; Raven, J.; Dieleman, M. Factors influencing the scale-up of public health interventions in low- and middle-income countries: A qualitative systematic literature review. Health Policy Plan. 2020, 35, 219–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, J.; Chandramohan, D.; Hanson, K. Methods for evaluating delivery systems for scaling-up malaria control intervention. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2010, 10 (Suppl. S1), S8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milat, A.; Bauman, A.; Redman, S. A narrative review of research impact assessment models and methods. Health Res. Policy Syst. 2015, 13, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bégin, H.; Eggertson, L.; Macdonald, N. A country of perpetual pilot projects. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2009, 180, 1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaton, J.; McCay, L.; Semrau, M.; Chatterjee, S.; Baingana, F.; Araya, R.; Ntulo, C.; Thornicroft, G.; Saxena, S. Scale up of services for mental health in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet 2011, 378, 1592–1603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, R.; Salvo, D.; Ogilvie, D.; Lambert, E.; Goenka, S.; Brownson, R. Scaling up physical activity interventions worldwide: Stepping up to larger and smarter approaches to get people moving. Lancet 2016, 388, 1337–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albury, D.; Beresford, T.; Dew, S.; Horton, T.; Illingworth, J.; Langford, K. Against the Odds: Successfully Scaling Innovation in the NHS. London (UK) Innovation Unit and The Health Foundation, 2018. Available online: https://www.innovationunit.org/wp-content/uploads/Against-the-Odds-Innovation-Unit-Health-Foundation.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2020).

- Hawn, C. Going Big: How Major Providers Scale Up Their Best Ideas. Oakland, United States: California Health Care Foundation, 2012. Available online: https://www.chcf.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/PDF-GoingBigProvidersScaleUpIdeas.pdf (accessed on 5 May 2020).

- Sutherland, R.; Campbell, E.; McLaughlin, M.; Nathan, N.; Wolfenden, L.; Lubans, D.R.; Morgan, P.J.; Gillham, K.; Oldmeadow, C.; Searles, A.; et al. Scale-up of the Physical Activity 4 Everyone (PA4E1) intervention in secondary schools: 12-month implementation outcomes from a cluster randomized controlled trial. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2020, 17, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Begg, C.; Cho, M.; Eastwood, S.; Horton, R.; Moher, D.; Olkin, I.; Pitkin, R.; Rennie, D.; Schulz, K.F.; Simel, D.; et al. Improving the Quality of Reporting of Randomized Controlled Trials: The CONSORT Statement. JAMA 1996, 276, 637–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Schulz, K.; Altman, D. The CONSORT statement: Revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of parallel-group randomized trials. JAMA 2001, 285, 1987–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: Guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol 2008, 61, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albrecht, L.; Archibald, M.; Arseneau, D.; Scott, S. Development of a checklist to assess the quality of reporting of knowledge translation interventions using the Workgroup for Intervention Development and Evaluation Research (WIDER) recommendations. Implement. Sci. 2013, 8, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruk, M.E.; Yamey, G.; Angell, S.Y.; Beith, A.; Cotlear, D.; Guanais, F.; Jacobs, L.; Saxenian, H.; Victora, C.; Goosby, E. Transforming Global Health by Improving the Science of Scale-Up. PLoS Biol. 2016, 14, e1002360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Papoutsi, C. Spreading and scaling up innovation and improvement. BMJ Clin. Res. 2019, 365, l2068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitworth, J.; Sewankambo, N.; Snewin, V. Improving Implementation: Building Research Capacity in Maternal, Neonatal, and Child Health in Africa. PLoS Med. 2010, 7, e1000299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solomon, J. Case Studies: Why are they important? Nat. Clin. Pract. Cardiovasc. Med. 2006, 3, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowe, S.; Cresswell, K.; Robertson, A.; Huby, G.; Avery, A.; Sheikh, A. The case study approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2011, 11, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsen, P. Making sense of implementation theories, models and frameworks. Implement. Sci. 2015, 10, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technology in Health. Grey Matters: A Practical Tool for Searching Health-Related Grey Literature Ottawa 2018 [Updated 2019]. Available online: https://www.cadth.ca/resources/finding-evidence (accessed on 5 June 2020).

- McKay, H.; Naylor, P.-J.; Lau, E.; Gray, S.M.; Wolfenden, L.; Milat, A.; Bauman, A.; Race, D.; Nettlefold, L.; Sims-Gould, J. Implementation and scale-up of physical activity and behavioural nutrition interventions: An evaluation roadmap. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2019, 16, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shelton, R.; Cooper, B.; Stirman, S. The Sustainability of Evidence-Based Interventions and Practices in Public Health and Health Care. Annu. Rev. Public Health 2018, 39, 55–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stirman, S.; Kimberly, J.; Cook, N.; Calloway, A.; Castro, F.; Charns, M. The sustainability of new programs and innovations: A review of the empirical literature and recommendations for future research. Implement. Sci. 2012, 7, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stirman, S.; Baumann, A.; Miller, C. The FRAME: An expanded framework for reporting adaptations and modifications to evidence-based interventions. Implement. Sci. 2019, 14, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, D.; Norton, W. The Adaptome: Advancing the Science of Intervention Adaptation. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2016, 51 (Suppl. S2), S124–S131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, D.; Glasgow, R.; Stange, K. The dynamic sustainability framework: Addressing the paradox of sustainment amid ongoing change. Implement. Sci. 2013, 8, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhandari, N.; Kabir, A.; Salam, M. Mainstreaming nutrition into maternal and child health programmes: Scaling up of exclusive breastfeeding. Matern. Child Nutr. 2008, 4, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organisation. Scaling Up Projects and Initiatives for Better Health: From Concepts to Practice. Denmark, 2016. Available online: https://www.euro.who.int/en/publications/abstracts/scaling-up-projects-and-initiatives-for-better-health-from-concepts-to-practice-2016 (accessed on 8 June 2020).

- Evans, D. Hierarchy of evidence: A framework for ranking evidence evaluating healthcare interventions. J. Clin. Nurs. 2003, 12, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Merlin, T.; Weston, A.; Tooher, R. Extending an evidence hierarchy to include topics other than treatment: Revising the Australian ‘levels of evidence’. BMC Med Res Methodol 2009, 9, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Powell, B.J.; Waltz, T.J.; Chinman, M.J.; Damschroder, L.J.; Smith, J.L.; Matthieu, M.M.; Proctor, E.K.; Kirchner, J. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: Results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Implement. Sci. 2015, 10, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leeman, J.; Birken, S.; Powell, B.; Rohweder, C.; Shea, C. Beyond “implementation strategies”: Classifying the full range of strategies used in implementation science and practice. Implement. Sci. 2017, 12, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spicer, N.; Bhattacharya, D.; Dimka, R.; Fanta, F.; Mangham-Jefferies, L.; Schellenberg, J.; Tamire-Woldemariam, A.; Walt, G.; Wickremasinghe, D. ‘Scaling-up is a craft not a science’: Catalysing scale-up of health innovations in Ethiopia, India and Nigeria. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014, 121, 30–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, P.; Reid, A.; Schall, M. A framework for scaling up health interventions: Lessons from large-scale improvement initiatives in Africa. Implement. Sci. 2016, 11, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Proctor, E.; Luke, D.; Calhoun, A.; McMillen, C.; Brownson, R.; McCrary, S.; Padek, M. Sustainability of evidence-based healthcare: Research agenda, methodological advances, and infrastructure support. Implement. Sci. 2015, 10, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Cancer Institute. Evidenced-Based Cancer Control Programs USA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Available online: https://ebccp.cancercontrol.cancer.gov/index.do (accessed on 24 February 2021).

- UNC Center for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention. SNAP-Ed Toolkit: Obesity Prevention Interventions and Evaluation Framework 2020 [updated 31 July 2020]. Available online: https://snapedtoolkit.org/ (accessed on 20 January 2021).

- Brug, J.; van Dale, D.; Lanting, L.; Kremers, S.; Veenhof, C.; Leurs, M.; van Yperen, T.; Kok, G. Towards evidence-based, quality-controlled health promotion: The Dutch recognition system for health promotion interventions. Health Educ. Res. 2010, 25, 1100–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinnock, H.; Epiphaniou, E.; Pearce, G.; Parke, H.; Greenhalgh, T.; Sheikh, A.; Griffiths, C.J.; Taylor, S.J.C. Implementing supported self-management for asthma: A systematic review and suggested hierarchy of evidence of implementation studies. BMC Med 2015, 13, 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehily, C.; Bartlem, K.; Wiggers, J.; Wye, P.; Clancy, R.; Castle, D.; Wutzke, S.; Rissel, C.; Wilson, A.; McCombie, P.; et al. Evaluating the effectiveness of a healthy lifestyle clinician in addressing the chronic disease risk behaviours of community mental health clients: Study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 2017, 18, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cranney, L.; Wen, L.M.; Xu, H.; Tam, N.; Whelan, A.; Hua, M.; Ahmed, N. Formative research to promote the Get Healthy Information and Coaching Service (GHS) in the Australian-Chinese community. Aust. J. Prim. Health 2018, 24, 248–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, B.; Holden, C.; Mackinder, S. Policy Transfer in the Context of Multi-level Governance. In The Battle for Standardised Cigarette Packaging in Europe: Multi-Level Governance, Policy Transfer and the Integrated Strategy of the Global Tobacco Industry; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 17–44. [Google Scholar]

- De Leeuw, E.; Peters, D. Nine questions to guide development and implementation of Health in All Policies. Health Promot. Int. 2014, 30, 987–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, J.; de Graft-Johnson, J.; Zyaee, P.; Ricca, J.; Fullerton, J. Scaling up high-impact interventions: How is it done? Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2015, 130 (Suppl. S2), S4–S10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cooley, L.; Linn, J. Taking Innovations to Scale: Methods, Applications and Lessons; Management Systems International: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kohl, R.; Cooley, L. Scaling Up—A Conceptual and Operational Framework; Management Systems International: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Escamilla, R.; Curry, L.; Minhas, D.; Taylor, L.; Bradley, E. Scaling up of breastfeeding promotion programs in low-and middle-income countries: The “breastfeeding gear” model. Adv. Nutr. Int. Rev. J. 2012, 3, 790–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wandersman, A.; Duffy, J.; Flaspohler, P.; Noonan, R.; Lubell, K.; Stillman, L.; Blachman, M.; Dunville, R.; Saul, J. Bridging the gap between prevention research and practice: The interactive systems framework for dissemination and implementation. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2008, 41, 171–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, N.; Barker, P.M. The importance of context in implementation research. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2014, 67 (Suppl. S2), S157–S162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelletier, D.; Corsi, A.; Hoey, L.; Faillace, S.; Houston, R. The Program Assessment Guide: An approach for structuring contextual knowledge and experience to improve the design, delivery, and effectiveness of nutrition interventions. J. Nutr. 2011, 141, 2084–2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschhorn, L.R.; Talbot, J.R.; Irwin, A.C.; A May, M.; Dhavan, N.; Shady, R.; Ellner, A.L.; Weintraub, R.L. From scaling up to sustainability in HIV: Potential lessons for moving forward. Glob. Health 2013, 9, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhalgh, T.; Wherton, J.; Papoutsi, C.; Lynch, J.; Hughes, G.; A’Court, C.; Hinder, S.; Fahy, N.; Procter, R.; Shaw, S. Beyond Adoption: A New Framework for Theorizing and Evaluating Nonadoption, Abandonment, and Challenges to the Scale-Up, Spread, and Sustainability of Health and Care Technologies. J. Med. Internet Res. 2017, 19, e367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezanson, K.; Isenman, P. Scaling up nutrition: A framework for action. Food Nutr. Bull. 2010, 31, 178–186. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lobo, R.; Petrich, M.; Burns, S.K. Supporting health promotion practitioners to undertake evaluation for program development. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 1315. [Google Scholar]

- Bernal, G.; Domenech Rodiguez, M. Cultural Adaptations: Tools for Evidence-Based Practice with Diverse Populations; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Schell, S.F.; Luke, D.A.; Schooley, M.W.; Elliott, M.B.; Herbers, S.H.; Mueller, N.B.; Bunger, A.C. Public health program capacity for sustainability: A new framework. Implement. Sci. 2013, 8, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheirer, M.A. Linking sustainability research to intervention types. Am. J. Public Health 2013, 103, e73–e80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norton, W.E.; Chambers, D.A. Unpacking the complexities of de-implementing inappropriate health interventions. Implement. Sci. 2020, 15, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palinkas, L.A.; Chou, C.-P.; Spear, S.E.; Mendon, S.J.; Villamar, J.; Brown, C.H. Measurement of sustainment of prevention programs and initiatives: The sustainment measurement system scale. Implement. Sci. 2020, 15, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).