Abstract

In order to develop nurses’ identities properly, they need to publicise their professional competences and make society aware of them. For that, this study was conducted to describe the competences that society currently attributes to nursing professionals and how nursing is valued in society. This review was based on the conceptual framework by Whittemore and Knafl. The literature search was conducted using PubMed, WOS, and CINAHL databases, and the search strategy was based on a combination of natural language and standardised keywords, with limits and criteria for inclusion, exclusion, and quality. The results of the studies were classified and coded in accordance with the competence groups of the professional profile described in the Tuning Educational Structures in Europe programme. Fourteen studies were selected. The most commonly reported competence groups were as follows: nursing practice and clinical decision making; and communication and interpersonal competences. Nursing is perceived as a healthcare profession dedicated to caring for individuals. Its other areas of competence and its capacity for leadership are not well known. In order to develop a professional identity, it is essential to raise awareness of the competences that make up this professional profile.

1. Introduction

A nurse’s professional identity (NPI) was described by Fargemoen as “the values and beliefs held by the nurse that guide her/his thinking, actions, and interaction with the patient” [1] (p. 437) that are considered to be inherent to professional development. The four key elements that make up NPI are the theoretical and practical knowledge that professional nurses must acquire; the definition of the professional role, setting out what nurses must know, do, think, and feel; the nurses’ own social and moral values, which cause them to behave in an expected, desirable manner; and the social image or representation of the profession, encompassing the prestige and value assigned to it by society [1,2,3].

Thus, the social or public image of the profession is a key component of professional identity. Generally speaking, nursing is recognised within society as a healthcare profession in its own right [4], whose essence lies in delivering care in close contact and developing ongoing relationships with patients, who are always vulnerable and completely or partially dependent [1]. The nursing profession is demanding, advocating for, and constructing a body of distinct, specific scientific knowledge that is produced and corroborated by its members [5]. This would provide a reasoned foundation for NPI to differentiate nursing from other professions and define its nature, characteristics, knowledge, and activities. However, it is very important that these aspects are made visible and highlighted within society so that the nursing profession is recognised for what it is. A number of studies highlight the fact that nursing professionals perceive patients as being unaware of and not understanding the role and tasks involved in nurses’ professional performance [6,7]. This lack of knowledge is even present among nursing students themselves, who, before starting the nursing degree, were not able to describe what nursing is or what nurses do [8,9,10]. As a result, nursing professionals are frequently mistaken for other healthcare workers [11,12,13] or defined by comparing healthcare workers with one other [14]. Therefore, it seems that the general public is unaware of the current academic, scientific, and professional situation of the profession, resulting in the profession often being misrepresented [4,15]. This may stem from the image that is sometimes portrayed in the media, the image of a secondary, passive, limited profession [6] that does not reflect its real competencies, thus rendering its competencies either invisible or unrecognised by society [16].

In the last decade, the nursing profession has evolved largely due to curriculum changes and the enactment of legislation aimed at structuring healthcare professions. In the United States, in 2021, the American Association of Colleges of Nurses established new guidelines for the purpose of shaping the education of nurses in a report entitled The Essentials: Core Competencies for Professional Nursing Education. This report lists 10 domains and their associated competencies, which are the essence of the nursing profession and practice [17]. In turn, in Europe, the Bologna declaration initiated a new competence-based training model developed through the Tuning Educational Structures in Europe programme in 1999 [18]. Both models describe curriculum outcomes in terms of competences, understood as the dynamic combination of attributes regarding knowledge, skills, attitudes, and responsibilities. As a result, nursing professions are defined by the set of competences that their professionals must possess. These programmes established the competencies that define the nursing profession by classifying them into five groups of competencies, as in the case of Europe, or into ten domains, as in the case of the United States [17,18]. Table 1 describes both classifications and identifies common areas between them.

Table 1.

Reference frameworks for the general descriptors of a bachelor’s degree programme in Nursing in Europe and in the United States.

This competence-based structure offers new guidance for understanding and learning nursing, and for current and future nursing professionals and students to work on their NPIs. It is therefore essential to gain an understanding of what is perceived about what nurses do and/or can do and the value that society places on the profession. Therefore, the aim of this study was to describe the competences that society currently attributes to nursing professionals and how nursing is valued in society.

2. Materials and Methods

Design: An integrative review was made. The stages followed in this review are based on the methodological framework developed by Whittemore and Knafl [19]: problem identification; rigorous search strategy; comprehensive evaluation; interpretation and critical analysis of selected data; synthesis and presentation of selected data.

Search Method: The databases explored were PubMed, WOS, and CINAHL. The search strategy was based on a combination of the following keywords: social perception/image/representation and nurse/nurses/nursing. The thesaurus of each database was selected for the search using standardised terms. Natural language keywords were used in the search by title and abstract. Details of the search strategies employed can be seen in Table 2. The search was conducted in April and May 2021. Finally, key authors in the selected documents were identified, and the snowballing technique was used.

Table 2.

Search strategies.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria: The search was limited to studies published between 2016 and 2021 in English, Spanish, and/or Portuguese. The inclusion criteria were as follows: articles whose object of study was the social image of nursing (IC1); original or review articles using a qualitative, quantitative, and/or mixed methodology (IC2).The exclusion criteria were as follows: articles using ahistorical methodology (EC1); studies with samples of nursing students in their second year and above or samples of professional nurses (EC2).The latter criterion was applied because first-year nursing students’ social image of the nursing profession remains intact. However, over time, their social image becomes self-image and is influenced by academic training and clinical placements.

Quality appraisal: The methodological quality of the studies was assessed using MMAT [20], an appraisal tool for qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods studies and reviews. The templates for the different methodologies were reviewed independently by the researchers. A low methodological quality score was used as an exclusion criterion (EC3).

Data extraction and analysis: The data extraction and synthesis followed the steps set out by Whittemore and Knafl [19]. The researchers read the selected studies exhaustively. Using an analytical comparative framework, the results of the studies were classified and coded in accordance with the competence groups defined by the Tuning Programme, as described in the Introduction section. We believe that this coding is flexible and specific enough to define the competence profile of a nurse in any context.

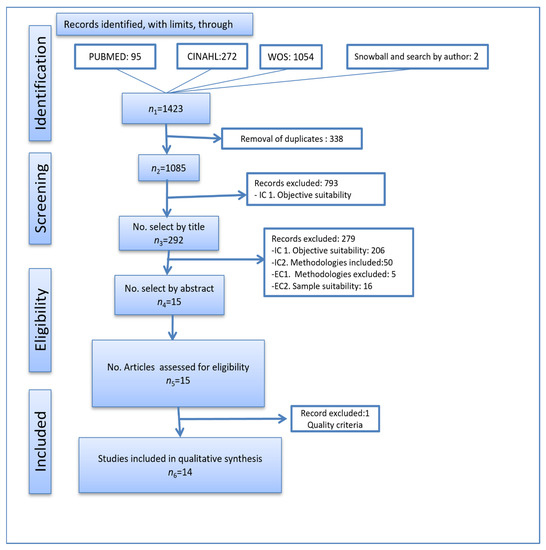

Search outcomes: When the search limits were applied, 1423 articles were found, of which two were identified by searching for key authors using the snowballing technique. Once duplicates were removed, there was a total of 1085 articles remaining. In the review, we discarded studies whose titles did not expressly focus on the perception of nursing competencies. We then proceeded to read the abstracts of the 292 selected titles, applying the established inclusion and exclusion criteria. As a result, 206 were discarded because their objectives were not in line with our research objectives; a further 55 were discarded because they had used a historical method, were letters to the editor, reflection articles, or similar; and a further 16 were discarded because they sought to ascertain nurses’ perceptions of other professional or user groups on the subject. The 15 resulting documents were read in their entirety and were assessed using the MMAT tool. One of them scored poorly and was therefore discarded (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Prisma flow diagram showing the article selection process.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Analysis

Fourteen articles were included in the review, which, in methodological terms, were three reviews, four quantitative studies, five qualitative studies, and two mixed methods studies. Study samples included young individuals and university students (three); nursing students (five); professionals working with nurses in teams (one); and, the general public users of healthcare facilities (one). Finally, another study took news in the media as a source of information. Table 3 shows a summary of the studies included.

Table 3.

Summary of the studies included.

3.2. Qualitative Analysis

A number of studies detected widespread ignorance of nursing functions, activities, and roles, and an inability to differentiate them from those exercised by doctors [23,32,33]. However, other studies report that nursing is viewed as a health sciences profession [33] whose primary mission is to care or deliver care [22,28,33,34]. Care is understood as the delivery of help, assistance, and services to patients and sick people, for whom nurses should act as resources during their processes [22,26,34]. The findings on professional competences and social perception are shown below.

3.2.1. Professional Competences Perceived by Society

Some studies have described in great depth the skill sets or groups of competences that society attributes to and/or expects from the nursing profession. We classified their contributions into the five groups of the Tuning framework:

Knowledge and cognitive competences: they include the possession of sound, up-to-date knowledge, a willingness to engage in lifelong learning, and the development of critical thinking skills and emotional intelligence to enable engagement with patients without burnout [26,30,34]. Two studies identified a perception of nurses as less intellectually capable [22] or inclined more to being skilled than to being intelligent [24]. There is limited representation of nursing research and the ability to apply this research evidence to nursing practice. Čukljek [26] reported that the items “Research is vital to nursing as a profession” and “Nurses incorporate research findings in their clinical practice” were viewed as largely irrelevant by their sample, obtaining an average score below agree. In the sample in the study by Albar [34], only 46% answered agree in response to the research profile, and 33% affirmed that nursing practice is based on scientific evidence.

Nursing practice and clinical decision making: nursing practice was mentioned in all the studies reviewed, suggesting that nursing is viewed as a predominantly practical profession [32]. Nursing is understood as a profession that operates primarily in the clinical setting. There is a tendency to perceive the nursing profession as existing primarily within hospitals [28,33,34]. As a result, the hospital setting is the main symbol representing nursing, as it is viewed as the physical space in which most nurses deliver care [28,33]. Other symbols include the uniform or clothing that nurses tend to wear in hospitals [26] and the equipment and instruments they use on a daily basis: stethoscope, gloves, etc. [30]. Nursing students agreed with this relationship between nursing and the hospital as the main working environment. For instance, the first-year nursing students participating in the study by Čukljek [26] explained that nurses care for sick individuals at the hospital. In addition, the sample in the study by Yilmaz [27] saw themselves working as clinical nurses in surgical and paediatric departments, for example, rather than in areas such as education or teaching, administration, and management in the healthcare sector. Other settings, such as home care [24,28] and end-of-life care [22], were rarely mentioned in the studies. Regarding health prevention, promotion, and recovery, Albar [34] reported that 84% of their sample of first-year nursing students agreed that the role of nurses was associated with health prevention, 90% with health promotion, and 94% with recovery. The techniques described include healing wounds, monitoring vital signs, taking samples, administering medication and fluids, taking anthropometric measurements, providing basic care, controlling pain, and working with technology [22,24,28,32,34]. Regarding clinical decision making, the nursing profession is even presented as “providing medical care”, an undeniably vague nuance found in Elmorshedy [25]. In other studies, nursing is viewed as a subordinate profession that depends on, assists, or helps doctors [22,25,29,34], with some alluding to a lack of overall autonomy, and, more specifically, to a lack of decision-making autonomy, and others to a lesser degree of responsibility [22,34]. Despite this being the predominant stance, other studies contradicted perceptions of this subordinate position. In Pierroti [28], nurses are identified as doctors’ assistants due to the 24/7 clinical care provided by the group in comparison with the brief contact between doctors and patients. Girvin [23] detected two conflicting positions; on the one hand, nursing is viewed as an autonomous profession characterised by comprehensive roles, broad knowledge, and high visibility, while on the other hand, nurses are perceived as doctors’ helpers or apprentices. However, Glerean [22] found that nursing is viewed as a profession with a low level of autonomy, despite nurses being perceived as independent professionals. The sample in Čukljek [26] displayed high levels of disagreement with the item “Nurses do not follow physicians’ orders without questions”, echoing Albar [34], in which 36% of the sample of students agreed with the item “Nurses make decisions on care autonomously”. The most extreme contradiction can be found in the study by Sanz Vega [24], where 69.1% of the sample agreed completely or somewhat with the item “Nursing involves functions that do not require a doctor to be present”, and only 2.1% agreed that one of the conditions required to be a nurse was obedience. Meanwhile, 10.7% of the sample disagreed with the item “Nurses only perform activities on a doctor’s orders”, indicating that more than 89% agreed with this statement.

Professional values and the role of the nurse: the professional values with the greatest representation were having a vocation, inclination, drive, or enthusiasm for the profession, and responsibility [24,29,33,34]. On the other hand, other studies included flexibility to change, versatility to take on different roles, and ability to cope with occupational risks, death, and times of maximum demand [22,28,30]. After these, the most represented values were altruism; being humane, possessing human sensibilities, or being humanitarian; respect, tolerance, and open-mindedness; being committed or dedicated to the profession; being hard-working; and self-sacrifice [22,28,29,30,33]. Finally, values with less representation were fellowship and being supportive; professionalism; determination and trustworthiness; solidarity; honesty and compassion; and being disciplined, cautiousness, and meticulousness [22,28,30,33].

Communication and interpersonal competences: these included empathy, active listening, communication skills, friendliness, and ability to establish close interpersonal relationships with patients [22,28,30,34].

Leadership and team working: these include connecting with other members of the multidisciplinary team, being able to engage in collaborative work, efficiency, leadership or charisma, and good time management [29,30]. Competences related to education, teaching, research, and management are only sporadically mentioned among nursing students or any other type of sample and in review studies [24,28,34]. With regard to management, Elmorshedy [25] found that 68.9% of their sample answered disagree to the idea of nurses holding senior management positions, as they viewed them as lacking the necessary training and skills.

3.2.2. Prestige and Value Attached by Society

The sample in Pierroti [28] viewed nursing as an essential, vital profession for improving patients’ health, as nurses are responsible for providing all forms of care, corroborating the findings of a number of studies. In the review by Terry [12], nurses are acknowledged to have a significant impact on the general population. Equally, in Yilmaz [27], 66% of the participants evaluated nurses’ professional status very positively, while only 12.5% evaluated it negatively. The sample in Browne [30] also made a very positive professional evaluation of nurses. The image of nursing observed by Glerean [22] portrays a profession that is highly valued and needed by the population.

More specifically, the sample in Sanz Vega [24] displayed high levels of trust in nurses: 97% of users would welcome nurses into their homes, 76% trusted nurses to apply new techniques, and 50% trusted nurses to prescribe medication, although 71.3% would confirm the prescription with a doctor. In addition, in the study by Čukljek [26], first-year nursing students showed the highest levels of agreement on the following items: “Nurses act as resource persons for individuals with health problems”, and “The service given by nurses is as important as that given by physicians”.

Some studies compared evaluations of different healthcare professionals by nursing students, other healthcare professionals, users, and the general public. With some ambivalence, the sample in Pierroti [28] viewed nurses as equally important as doctors but said that doctors enjoyed greater prestige. In Terry [21], nurses are considered inferior to doctors or with a lower social status. Similarly, Glerean [22] showed that the nursing profession has low levels of recognition or social status. We identified the lowest level of social status in Elmorshedy [25], whose sample, university students and teachers, stated that they would be ashamed to have a nurse in their family.

According to the findings reported by Girvin [23], the nursing profession is sometimes not recommended by school career advisors or family members because it is not viewed as the ideal career. Conversely, in Sanz Vega [24], 73.4% of the respondents viewed the profession as a good occupation that they would recommend to their loved ones.

In consonance with Sánchez-Gras [31], and according to Girvin [23], nurses are generally portrayed in the press as professionals with a secondary role associated with another profession, with little responsibility, autonomy, or decision-making capacity. The nursing profession is conveyed as uninteresting, unchallenging, and lacking in creativity and responsibility, with few opportunities for growth or promotion, with a low academic level, low pay, and low social status. According to these studies, the image conveyed in the media centres around mistakes made by nursing professionals, errors with an impact on patients’ health, negligence, and even crimes committed by nurses [23,31]. In contrast, the sample in Sanz Vega [24] disagreed with the image of nursing portrayed by the media for failing to do justice to the profession’s social status or prestige. According to Girvin [23], websites belonging to official institutions and healthcare facilities reveal the dominance of medicine over the other healthcare professions. Nursing is barely represented: it is not even listed as a service or as one of 10 professions featured, unlike other professions such as medicine [23].

4. Discussion

Our findings suggest that nursing is perceived as a healthcare profession whose primary function is to provide care, which is consistent with other studies that also link nurses to care work [8] for the sick in hospital, administering medication [10], or performing patient hygiene [6,35,36]. To this end, society considers it vital, almost a prerequisite, that nurses possess high technical skills, thus perpetuating the classical view of healthcare, nursing care, the nursing profession, and the recipient of care. The social perception of nurses’ knowledge and cognitive competences is in line with American and European structures alike, although nursing research and the application of nursing evidence to nursing practice is considered to be of little to no relevance by society. Even though there is no doubt that nursing research has increased considerably, society still seems to be unaware of nurses’ research competence. This may be related to the image of the clinical nurse, dedicated to caring for sick people in the hospital. Areas such as health promotion, disease prevention, and assisting healthy individuals have not been reflected in society’s perception either, which echoes previous studies [8].

Even communication skills are reduced to interpersonal relations, which are established between nurses and patients in the care setting, ignoring other contexts such as interprofessional relations and communication through mass media, which are included in our profile. The competence to communicate in political contexts and to participate in health policies has not emerged. This is likely to be linked to the dependent role attributed to the profession. The limited involvement and visibility of nurses in these decision-making groups is increasingly evident and vindicated by professionals. In this regard, the International Council of Nurses states that it is critical to ensure that nurses have a say in the development and implementation of healthcare policies in order to ensure that these policies are effective in meeting the real needs of patients, families, and communities around the world. This aspect has been investigated by different authors, such as Benton, Al Maaitah [37]; Rasheed and Younas [38]; and, Cervera-Gasch and Mena-Tudela [39]; who have proposed interesting interventions to include this competence in the nursing colleges. However, in order to achieve this status, society needs to become aware of nurses’ real competences and value them.

Society identifies communicative values and competences, but relates them more to personal attributes than to professional competences. This view is confirmed by studies that identify the following professional values as qualities of nurses: being responsible and skilful [40]; compassionate and kind [13]; kind, patient, and affectionate [41]. This perception favours an out-dated view of the profession, tied to its historical background, thus downplaying the importance of professionalism. In addition, a number of healthcare managers and many nurse educators maintain a vocational style, which can lead to considerable differences between nursing education institutions in terms of the overall vision of nursing [42].

Leadership and team work competences coincide with some of the ideas presented in this review. Society perceives nurses as being able to work collaboratively with other professionals. At the same time, however, society places nurses in an inferior position to other team members. Although the value attributed to the nursing profession is similar to that of the medical profession, it is perceived as a secondary role associated with another profession, lacking the training and skills for team management, with few opportunities for growth or promotion, and with little responsibility, autonomy, or decision-making capacity. This vision is more prominent in certain cultural contexts where this lack of autonomy is understood as obedience, where nurses are perceived as simply following the doctor’s instructions [10,40,43]. The idea of being subordinated to the medical profession also influences the self-concept and professional identity of nurses [4] and their social perception. It is sometimes argued that the social prestige of nursing is poor because it is compared to other professions such as medicine [35,44], highlighting that choosing to study medicine as opposed to nursing is linked to the higher status of medicine [14]. Nevertheless, nurses’ knowledge, skills, and abilities, which underpin the profile defined in the aforementioned programmes, do equip them with the competences to work autonomously and independently. Authors have shown that nursing was considered to be as prestigious as the medical profession, ranking it higher in terms of the trust patients place in them [6]. It is important to note that, according to the annual Gallup report, nurses have been selected for the twentieth year running by the American population as the professionals they trust the most for their honesty and ethics. They were voted for by 81% of the sample, ranking ahead of doctors, teachers, pharmacists, and the military [45]. In addition, our findings suggest that the value that society places on nursing is positive, and it is perceived as an essential profession for improving people’s health.

The limitations of this integrative review include the methodological variability of the studies reviewed, which hindered the comparison of their results, and the wide range of territories covered, which produced conflicting results depending on the majority culture in the region of study.

5. Conclusions

The competences attributed by society to nursing professionals do not match the set of competences described in the professional profile of nurses. A lack of knowledge and a partial vision of nursing leave out essential aspects of the profession, such as nurses’ capacity for research and leadership, health policy planning, and health management. These aspects constrain the development of the profession and the creation of a professional identity, and therefore it is essential to make society aware of the real professional competencies of nurses.

This article provides a comparison between the competences defining the nursing profile as per the European and American frameworks, and the skills attributed by society to nurses and how society perceives them. It also provides the ideal framework for comparing reality and perceptions, enabling researchers to identify competence areas that are less known or valued by society in order to be able to address them.

Professional nurses must realise that the solution to the mismatches between the projected image, the perceived image, and reality must come from nurses themselves as a whole and in different contexts, such as faculties, professional associations, scientific associations, etc., focusing on the least known areas, such as research, teaching, and management. In particular, nurses need to take on and project their capacity for leadership to be able to participate fully in the development of health policies and health legislation. To this end, it appears to be essential that nurses follow the ICN guidelines and assume their role as health leaders. Nurses can do this by using traditional media and today’s wide array of social media, embracing and developing their own social media skills, which they could use to make their research results more visible, beyond professional circles. Finally, it is also essential to influence prospective students, e.g., through recruitment open days, and people who influence their choice of career, such as educators, career advisors, and parents, so that they can advise students with knowledge of the reality of the profession’s competences.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.R.-P. and C.T.-M.; methodology, M.R.-P. and C.T.-M.; software, M.R.-P., C.T.-M. and A.D.-P.; formal analysis, M.R.-P. and C.T.-M.; investigation, M.R.-P., C.T.-M., F.M.-N. and A.D.-P.; resources, M.R.-P., C.T.-M., F.M.-N. and A.D.-P.; data curation, M.R.-P., C.T.-M., F.M.-N. and A.D.-P.; writing—original draft preparation, M.R.-P., C.T.-M. and A.D.-P.; writing—review and editing, M.R.-P. and C.T.-M.; visualization, F.M.-N.; supervision, M.R.-P. and C.T.-M.; project administration, M.R.-P. and C.T.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Fargemoen, M.S. Professional identity: Values embedded un meanningful nursing practice. J. Adv. Nurs. 1997, 25, 434–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celma Vicente, M. Cultura Organizacional y Desarrollo Profesional de las Enfermeras. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Granada, Granada, Spain, 2007. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10481/1792 (accessed on 3 January 2022).

- Pimentel, M.H.; Pereira, F.A.; Pereira da Mata, M.A. La construcción de la identidad social y profesional de una profesión femenina: Enfermería. Prism. Soc. 2011, 7, 1–23. Available online: http://www.isdfundacion.org/publicaciones/revista/numeros/7/secciones/abierta/06-identidad-social-profesion-femenina-enfermera.html (accessed on 3 January 2022).

- Hoeve, Y.; Jansen, G.; Roodbol, P. The nursing profession: Public image, self-concept and professional identity. J. Adv. Nurs. 2014, 70, 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vega Angarita, O.M. Estructura del conocimientos contemporaneo de enfermería. Rev. Cienc. Cuid. 2006, 3, 53–68. Available online: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=2533967 (accessed on 3 January 2022).

- Woods-Giscombe, C.L.; Johnson Rowsey, P.; Kneipp, S.; Lackey, C.; Bravo, L. Student perspectives on recruiting underrepresented ethnic minority students to nursing: Enhancing outreach, engaging family, and correcting misconceptions. J. Prof. Nurs. 2020, 36, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasmussen, P.; Henderson, A.; McCallum, J.; Andrew, N. Professional identity in nursing: A mixed method research study. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2021, 52, 103039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teresa-Morales, C.; González-Sanz, J.D.; Rodríguez-Pérez, M. Components of the nursing role as perceived by first-year nursing students. Nurse Educ. Today 2021, 102, 104906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamieson, I.; Harding, T.; Withington, J.; Hudson, D. Men entering nursing: Has anything changed? Nurs. Prax. N. Z. 2019, 35, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, R. Professional Identity of Male Nursing Students in 3-Year Colleges and Junior Male Nurses in China. Am. J. Mens Health 2020, 14, 1557988320936583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Verdugo, M.; Ponce-Blandón, J.A.; López-Narbona, F.J.; Romero-Castillo, R.; Guerra-Martín, M.D. Social Image of Nursing. An Integrative Review about a Yet Unknown Profession. Nurs. Rep. 2021, 11, 460–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-I.; Yu, H.-Y.; Chin, Y.-F.; Lee, L.-H. There is nothing wrong with being a nurse: The experiences of male nursing students in Taiwan. Jpn. J. Nurs. Sci. 2017, 14, 332–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liu, H.Y.; Li, Y.L. Crossing the gender boundaries: The gender experiences of male nursing students in initial nursing clinical practice in Taiwan. Nurse Educ. Today 2017, 58, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, R.K.; Diefenbeck, C. Challenging stereotypes: A glimpse into nursing’s difficulty recruiting African Americans. J. Prof. Nurs. 2020, 36, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Norman, K.M. The image of community nursing: Implications for future student nurse recruitment. Br. J. Community Nurs. 2015, 20, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crisp, N. Nursing-the wave of the future. BMJ 2018, 361, k2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Association of Colleges of Nursing. The Essentials: Core Competencies for Professional Nursing Education. 2021. Available online: https://www.aacnnursing.org/Portals/42/AcademicNursing/pdf/Essentials-2021.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2022).

- European Union. Tuning Educational Structures in Europe. In Guidelines and References Points for the Design and Delivery of Degree Programmes in Nursing; European Commision: Goningen, The Netherlands, 2018; Available online: https://www.calohee.eu/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/1.4-Guidelines-and-Reference-Points-for-the-Design-and-Delivery-of-Degree-Programmes-in-Nursing-READER-v3.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2022).

- Whittemore, R.; Knafl, K. The integrative review: Updated methodology. J. Adv. Nurs. 2005, 52, 546–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q.; Pluye, P.; Fábregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Pierre, D.; Marie-Pierre, G.; Frances, G.; Belindah, N.; et al. Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), version 2018. 2018. Available online: http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/127916259/MMAT_2018_criteria-manual_2018-08-01_ENG.pdf (accessed on 3 January 2022).

- Terry, D.; Peck, B.; Carden, C.; Perkins, A.J.; Smith, A. Traversing the Funambulist’s Fine Line between Nursing and Male Identity: A Systematic Review of the Factors that Influence Men as They Seek to Navigate the Nursing Profession. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2020, 10, 691–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glerean, N.; Hupli, M.; Talman, K.; Haavisto, E. Young peoples’ perceptions of the nursing profession: An integrative review. Nurse Educ. Today 2017, 57, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girvin, J.; Jackson, D.; Hutchinson, M. Contemporary public perceptions of nursing: A systematic review and narrative synthesis of the international research evidence. J. Nurs. Manag. 2016, 24, 994–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sanz Vega, C.M.; Martínez Espinosa, A.; Longo Alonso, C.; Charro Alonso, S.; Antón Martínez, G.; Losada Riesgo, V.C. Una fotografía de la imagen social de la Enfermería. RqR Enfermería Comunitaria Rev. SEAPA 2020, 8, 31–41. Available online: https://ria.asturias.es/RIA/handle/123456789/13170 (accessed on 3 January 2022).

- Elmorshedy, H.; AlAmrani, A.; Hassan, M.H.A.; Fayed, A.; Albrecht, S.A. Contemporary public image of the nursing profession in Saudi Arabia. BMC Nurs. 2020, 19, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Čukljek, S.; Jureša, V.; Grgas Bile, C.; Režek, B. Changes in Nursing Students’ Attitudes Towards Nursing During Undergraduate Study. Acta Clin. Croat 2017, 56, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yilmaz, A.A.; Ilce, A.; Can Cicek, S.; Yuzden, G.E.; Yigit, U. The effect of a career activity on the students’ perception of the nursing profession and their career plan: A single-group experimental study. Nurse Educ. Today 2016, 39, 176–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierroti, V.W.; Guirardello, E.d.B.; Toledo, V.P. Nursing knowledge patterns: Nurses’ image and role in society perceived by students. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2020, 73, e20180959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çetinkaya, A.; Rahman, S.; Elbi, H.; Altan, S. Perceptions of intern physicians about nursing profession: A qualitative research. Cukurova Med. J. 2019, 44, 148–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Browne, C.; Wall, P.; Batt, S.; Bennett, R. Understanding perceptions of nursing professional identity in students entering an Australian undergraduate nursing degree. Nurse Educ. Pract. 2018, 32, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Gras, S. Imagen de la enfermería a través de la prensa escrita ¿necesitamos visibilizar los cuidados enfermeros? Cult. Cuid. 2017, 21, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Crawford, R.M.; Gallagher, P.; Harding, T.; McKinlay, E.M.; Pullon, S.R. Interprofessional undergraduate students talk about nurses and nursing: A qualitative study. Nurse Educ. Today 2016, 39, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastias, F.; Giménez, I.; Fabaro, P.; Ariza, J.; Caño-Nappa, M.J. Social representations of nurses. Differences between incoming and outgoing Nursing students. Investig. Educ. Enferm. 2020, 38, e05. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albar, M.J.; Sivianes-Fernández, M. Percepción de la identidad profesional de la enfermería en el alumnado de grado. Enfermería Clínica 2016, 26, 194–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaw, S.Y.; Wu, L.T.; Holroyd, E.; Wang, W.; Lopez, V.; Lim, S.; Chow, Y.L. Why not nursing? Factors influencing healthcare career choice among Singaporean students. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2016, 63, 530–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Marcinowicz, L.; Owlasiuk, A.; Perkowska, E. Exploring the ways experienced nurses in Poland view their profession: A focus group study. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2016, 63, 336–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benton, D.C.; Al Maaitah, R.; Gharaibeh, M. An integrative review of pursing policy and political competence. Int. Nurs. Rev. 2017, 64, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rasheed, S.P.; Younas, A.; Mehdi, F. Challenges, Extent of Involvement, and the Impact of Nurses’ Involvement in Politics and Policy Making in in Last Two Decades: An Integrative Review. J. Nurs. Scholarsh. 2020, 52, 446–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cervera-Gasch, Á.; Mena-Tudela, D.; Castro-Sánchez, E.; Santillan-Garcia, A.; Andreu-Pejó, L.; González-Chordá, V.M. Necessary political competences for nurses from the perception of the student body: Cross-sectional study in Spain. Nurse Educ. Today 2022, 109, 105229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kluczyńska, U. Motives for choosing and resigning from nursing by men and the definition of masculinity: A qualitative study. J. Adv. Nurs. 2017, 73, 1366–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teresa Morales, C.; Feria Lorenzo, D.J.; Rodríguez Pérez, M. Imagen social y valoración de la profesión enfermera para el alumnado del Grado de Enfermería. Temperamentvm 2019, 15, e12540. Available online: http://ciberindex.com/c/t/e12540 (accessed on 3 January 2022).

- Findlow, S. Higher education change and professional-academic identity in newly ‘academic’ disciplines: The case of nurse education. High. Educ. 2012, 63, 117–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, M.L.; Tseng, Y.H.; Hodges, E.; Chou, F.H. Lived Experiences of Novice Male Nurses in Taiwan. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2018, 29, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kämmer, J.E.; Ewers, M. Stereotypes of experienced health professionals in an interprofessional context: Results from a cross-sectional survey in Germany. J. Interprof. Care 2021, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallup. Gallup’s Annual Rating of the Honesty and Ethics of Various Professions. 2021. Available online: https://news.gallup.com/poll/388649/military-brass-judges-among-professions-new-image-lows.aspx (accessed on 3 January 2022).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).