Abstract

Service users’ views and expectations of mental health nurses in a UK context were previously reviewed in 2008. The aim of this systematic review is to extend previous research by reviewing international research and work published after the original review. Five databases were searched for studies of any design, published since 2008, that addressed service user and carer views and expectations of mental health nurses. Two reviewers independently completed title and abstract, full-text screening and data extraction. A narrative synthesis was undertaken. We included 49 studies. Most included studies (n = 39, 80%) were qualitative. The importance of the therapeutic relationship and service users being supported in their personal recovery by mental health nurses were core themes identified across included studies. Service users frequently expressed concern about the quality of the therapeutic relationship and indicated that nurses lacked time to spend with them. Carers reported that their concerns were not taken seriously and were often excluded from the care of their relatives. Our critical appraisal identified important sources of bias in included studies. The findings of our review are broadly consistent with previous reviews however the importance of adopting a recovery approach has emerged as a new focus.

1. Introduction

Nurses represent approximately 44% of the global mental health workforce [1]. Mental health services are increasingly focusing on providing patient-centred care and treatment [2,3]; this requires that there is a deep understanding of the views and expectations of people experiencing mental ill-health about mental health nurses [4].

Adopting a recovery approach requires nurses to work in a collaborative way with service users to support their recovery objectives [5]. Understanding the views and expectations of service users and their carers may inform mental health policy and practice. In addition, treatment and care for a person suffering from mental ill-health may require a comprehensive and evidence-based approach that encourages service users and their carers to actively participate in their care [6]

The views and expectations of service users towards mental health nurses have been previously reviewed. A systematic review which was undertaken as part of the chief nursing officer’s review of mental health nursing in England (United Kingdom Department of health, 2006) by Bee et al. [7] included 132 studies involving 36,793 participants. The aim of the review was to examine service users’ and carers’ views and expectations of mental health nurses registered and practicing in the United Kingdom. Primary research of any type, where fieldwork was conducted in the UK and was published prior to 2005, was included in the review. The authors undertook a narrative synthesis of included studies and reported that service users viewed mental health nursing as a multifaceted profession that provides practical and social support as well as formal psychological treatments [7]. Review authors also reported consistent negative views of mental health nurses; specifically, that they were inaccessible, did not give enough information to service users, and often did not work in a way perceived as collaborative or patient-centred [7]. The review authors aimed to examine carers’ views and expectations of mental health nurses but could not identify any relevant studies [7].

The methodological quality of included studies in Bee et al. [7] review was determined using guidelines for reviewing non-randomised, observational and qualitative literature [8]. Important methodological limitations were identified across studies that included possible selection bias, and some survey instruments were not assessed for validity [7].

Bee et al. [7] limited the study setting to the United Kingdom and excluded evidence from other countries. To fully understand how people who use mental health services view and perceive MHNs, it would be informative to undertake an updated systematic review of all relevant research, regardless of where fieldwork was conducted. In part, this is because there have been substantial changes to how mental health care is provided since 2005. For example, a shift to recovery-oriented working in, the UK, Australia and North America, from around 2009 [9].

We searched Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online [MEDLINE] [OVID] and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature [CINAHL] (EbscoHost) from 2005 to 2022 to identify if a review—of any type—that examined the views and expectations of service users and/or carers about mental health nurses had been undertaken. No reviews were identified.

Aim: To extend and update the systematic review by Bee et al. [7] about the views and expectations of mental health service users and carers about mental health nurses.

2. Materials and Methods

The methodology of this systematic review complies with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses 2020 checklist (PRISMA) [10]. As far as possible, we used the methodology described by Bee et al. [7], where we have deviated, we note this in our reporting. The protocol for this review was registered with Open Science Framework (https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/QWDHU) (accessed on 26 July 2022) after searches were undertaken but prior to data analysis.

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

We included studies that met the following inclusion criteria:

- Reported the views of service users and carers towards mental health nurses.

- Were conducted from July 2005 to December 2021. The July 2005 cut-off date was chosen to coincide with the last date of the search for a similar review [7].

- Were written in English.

No restrictions were placed on the study design, fieldwork settings, or age of participants.

We did not include studies that reported individual case studies, were focused on formal therapeutic interventions (e.g., cognitive behavioural therapy) or evaluated goal-directed nursing tasks (e.g., care planning, medication supervision). In this review, we defined a mental health nurse as a registered nurse working in any mental health setting. The views and expectations of service users/carers were defined as any expressed opinions regarding any aspect of the mental health nurse–service user/carer relationship that happens outside formal therapeutic procedures or task-directed nursing interventions [7].

2.2. Information Sources

We searched five electronic databases (platform in brackets):

- Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online [MEDLINE] (OVID)

- Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature [CINAHL] [EbscoHost]

- Excerpta Medica database [EMBASE] (OVID)

- Cochrane central (WILEY)

- PsychINFO (OVID)

We did not search for grey literature—a deviation from the Bee et al. [7] methodology—because the work has not been through a transparent peer-review process [11]. Our initial search was conducted on the 1 June 2020 and updated on the 21 February 2022.

2.3. Search Strategy

We used the search terms described by Bee et al. [7]. We searched for the Medical Subject Headings (MesH) and free-text phrases such as synonyms or abbreviations. Our review focused on three concepts: (that broadly align with those used by Bee et al. [7]): 1. mental health service users and their family and friends (carers), 2. mental health nurses, 3. views and expectations. Each concept’s MeSH and free-text terms were combined using the Boolean operator ‘OR.’ The Boolean operator ‘AND’ was used to connect all three concepts. The citations were exported from bibliographic databases to Endnote (reference management software). References were then exported to Covidence, a systematic review management software package. The search strategies are shown in Supplementary Document S1.

2.4. Selection Process

Title and abstract and full-text screening was undertaken using the Covidence software package by two reviewers (NM, DK, NA, AJ, SP) any discrepancies resolved by a third.

2.5. Data Collection Process

We extracted data from included studies based on recommendations from the Cochrane handbook [12]. We were not able to use the data items from the Bee et al. [7] review as there were not reported in the manuscript. Two reviewers (NM, DK, NA, AJ, SP) independently extracted data from included studies, a third reviewer resolved any inconsistencies.

2.6. Data Items

The following data were extracted from each included study: author (coded surname, initial), year of publication, digital object identifier, the country where fieldwork was conducted, study aim, study setting (coded inpatient, community, inpatient and community (mixed), study population(s) (coded service users, carers), study design, sampling method, data collection procedures (coded interviews, focus groups, surveys), psychometric properties (validity) of measures used, approach to data analysis, summary of key study findings.

2.7. Risk of Bias Assessment

Quality appraisal of included studies was undertaken using three measures (Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality Assessment Tool (EPHPP), Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), and Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal checklist for qualitative research]. The use of formal quality appraisal measures is divergent from the Bee et al. [7] review that did not use recognised critical appraisal tools.

We used the EPHPP to assess the risk of bias for observational studies [13]. The EPHPP has established psychometric properties [13,14]. The tool has six components: 1. selection bias, 2. study design, 3. confounders, 4. blinding, 5. data collection method, 6. withdrawals and dropouts [13], each appraised as strong, moderate, or weak. The overall rating of the study is determined based on the following criteria: strong (no weak ratings), moderate (one weak rating) or weak (two or more weak ratings) [13].

For mixed method studies, we used the MMAT [15]. The measure contains five criteria: 1. the rationale for using mixed methods, 2. integration of qualitative and quantitative study components, 3. interpretation of the results, 4. divergences and inconsistencies between quantitative and qualitative findings, and 5. different study components adhering to the quality criteria of each methodological tradition. Each item is rated “yes”, “no”, “cannot tell”, [15]. The MMAT does not produce an overall quality rating.

JBI critical appraisal tool for qualitative research [16] has ten items rated “yes”, “no”, “unclear”, or “not applicable”. The items are: 1. research methodology and its philosophical perspective, 2. study design, 3. data collection method, 4. data analysis method, 5. interpretation of results, 6. cultural or theoretical location of the researcher, 7. the influence of the researcher on the study, 8. representation of participants and their perspectives, 9. ethical considerations, and 10. the relationship between the results and the participants’ views [16]. Items are reported as a summary, there is no overall quality rating.

Two reviewers completed the critical appraisal task independently. A third reviewer resolved any disagreements between reviewers.

2.8. Grouping Studies for Synthesis

We made a post hoc decision to group included studies based on study population: 1. service users, 2. carers.

In our protocol, we also stated that we would group studies based on the clinical setting where fieldwork was undertaken, this approach did not prove practical because of the large number of clinical settings we identified. We, therefore, made a post hoc decision to recode studies into three broader clinical groupings: 1. hospital inpatient, 2. community, 3. mixed [community and inpatient] services.

2.9. Data Synthesis

We summarized the findings of multiple primary studies using words and text, a technique known as narrative synthesis [17]. We extracted data from the included studies in tabular form and critically appraised the methodological quality of each study [see Table 1, Table 2, Table 3 and Table 4]. We briefly described each study to familiarize ourselves with the research and compare findings. Studies were grouped based on the views of service users and carers about MHNs, this made it easier to describe, analyze, and look for patterns within and across these groups. Emerging themes across the studies were identified. In 38 studies, in-depth interviews were conducted to collect data, yielding varying themes. These themes occasionally overlapped, necessitating the classification of some studies under multiple themes. Content and thematic analysis were mixed to comprehensively describe the findings from included studies. We could not perform a meta-analysis of the survey and experimental studies because of the heterogeneity of methodologies and outcomes.

Table 1.

Summary of the included studies.

Table 2.

Summary of the characteristics of the included studies.

Table 3.

Quality assessment for cross-sectional and experimental studies using the effective public health practice project quality assessment tool.

Table 4.

Risk of bias assessment for mixed method studies using the mixed methods appraisal tool [MMAT].

2.10. Amendments to Information Provided at Registration

We made three amendments to the study following the registration of the protocol with the Open Science Framework. Amendment one was a change to the study title, which was originally described as an updated systematic review and which we changed to a systematic review. We also amended the review aim and method to reflect this amendment. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool was listed in the protocol as the quality appraisal measure for all included studies. We considered that other quality appraisal measures were more appropriate for determining the risk of bias in included studies. Post hoc, we decided to use the EPHPP for observational and experimental and the JBI appraisal checklist for qualitative studies. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool was retained for mixed methods only. As stated above, during study synthesis, we coded studies into three clinical groupings.

3. Results

3.1. Description of Included Studies

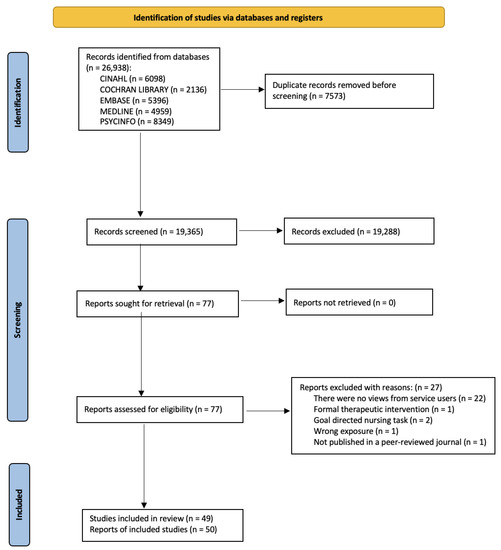

The flow of studies through the review is shown in Figure 1. Our search generated 26,938 studies. Fifty papers, reporting 49 studies, met our inclusion criteria and were included in the review. Authors of one study reported results across two papers [30,31]. Supplementary Document S2 is a complete list of all included articles. Studies excluded at full-text screening (n = 27) [68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94] are listed in Supplementary Document S3. Data extracted from included studies are summarised in Table 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

We contacted the corresponding authors of nine studies to request additional information on: 1. the clinical setting where fieldwork was conducted [29,30,31], 2. the population and sample size [30,31,34,37,41,55], 3. ethics approval [64] and 4. approach to data analysis [28,40]. As of the 27 June 2022, two authors, [28,37] responded, providing the requested information that we incorporated in the risk assessment data extraction tables, respectively.

Table 2 is a summary of the characteristics of included studies. Around eight out of ten included studies were described as qualitative and used interviews or focus groups as a method of data collection. Fieldwork for two-thirds of the studies was conducted with participants that were community dwelling. Three-fifths of the studies were conducted in countries with advanced economies, including Australia, the United Kingdom and the United States of America.

Two-thirds of studies were exclusively focused on service users. Ten studies included both service users and carers, and five just carers. The total number of service users and carers involved in included studies was 1689 and 166 (the number of carers included was not reported in three studies [30,31,34,55] respectively). The median sample size for included studies was 15 (range, five to 511). The diagnosis of participants was reported in half of the studies. The most common reported psychiatric diagnoses were schizophrenia, personality disorders, and depression.

3.2. Quality Appraisal

Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5 summarise the quality appraisal for included studies against the criteria from the relevant critical appraisal measure. All eight observational and experimental studies were rated as having a high risk of bias (Table 3). Six out of eight studies had a risk of selection bias because the authors used convenience sampling to identify participants. Most author used measures were developed specifically for the study [n = 5] that had not been validated.

The two mixed methods studies satisfied three of the five items of the MMAT (Table 4). None of the included studies addressed divergences or inconsistencies between quantitative and qualitative findings. Giménez-Díez et al. [28] did not provide a compelling rationale for utilising a mixed methods design to address the research question. In the McCloughen et al. [48] study, the authors did not demonstrate the validity of the measure used in the study.

Table 5 summarises qualitative studies against the ten JBI critical appraisal criteria. Included qualitative studies addressed the majority of JBI criteria. Two criteria that were not addressed by over half of the included studies were statements that contextualised the researcher culturally or theoretically (item 6) and addressed the effect of the researcher on the study and vice versa (item 7). We note that the authors of the two studies did not explicitly state that the study had been reviewed and approved by an ethics committee or Institutional Review Board [23,95].

Brimblecombe et al. [21] conducted a national consultation study using electronic response forms and open meetings to collect data and analysed it using content analysis. We could not identify a relevant critical appraisal tool for this type of research.

Our results are organized under service user and carer views and expectations of mental health nurses.

Table 5.

Risk of bias assessment for qualitative studies using the Joanna Briggs Institute checklist for qualitative research.

Table 5.

Risk of bias assessment for qualitative studies using the Joanna Briggs Institute checklist for qualitative research.

| Study Author | Digital Object Identifier (DOI) | Criteria 1 | Criteria 2 | Criteria 3 | Criteria 4 | Criteria 5 | Criteria 6 | Criteria 7 | Criteria 8 | Criteria 9 | Criteria 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ådnøy Eriksen et al. (2014) [18] | https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12024 (accessed on 20 June 2022) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Askey et al. (2009) [19] | https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6427.2009.00470.x (accessed on 20 June 2022) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Biringer et al. (2021) [20] | https://doi.org/10.1111/ppc.12633 (accessed on 20 June 2022) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Coatsworth-Puspoky et al. (2006) [22] | https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2006.00968.x (accessed on 20 June 2022) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Cunningham & Slevin (2005) [23] | https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2004.00769.x (accessed on 20 June 2022) | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Earle et al. (2011) [24] | https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2010.01672.x (accessed on 20 June 2022) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Evans et al. (2021) [25] | https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12795 (accessed on 20 June 2022) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Frain et al.l. (2021) [26] | https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2020.1820120 (accessed on 20 June 2022) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Gerace et al. (2018) [27] | https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12298 (accessed on 27 July 2022) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Goodwin & Happell (2006) [29] | https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-0349.2006.00413.x (accessed on 27 July 2022) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Goodwin & Happell (2007) [30] | https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840701354596 (accessed on 27 July 2022) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Goodwin & Happell (2007) [31] | https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840701354612 (accessed on 27 July 2022) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Gray & Brown (2017) [32] | https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12296 (accessed on 27 July 2022) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Gunasekara et al. (2014) [33] | https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12027 (accessed on 27 July 2022) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Happell & Palmer (2010) [35] | https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2010.488784 (accessed on 27 July 2022) (accessed on 27 July 2022) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Horgan et al. (2021) [36] | https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12768 (accessed on 27 July 2022) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Jones et al. (2007) [37] | https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04332.x (accessed on 27 July 2022) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Keogh et al. (2020) [38] | https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2020.1731889 (accessed on 27 July 2022) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Kertchok (2014) [39] | https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2014.908439 (accessed on 27 July 2022) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Lees et al. (2014) [42] | https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12061 (accessed on 27 July 2022) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Lessard- Deschênes, & Goulet (2022) [43] | https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12800 (accessed on 27 July 2022) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Lim et al. (2019) [44] | http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11937/77779 (accessed on 27 July 2022) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| McAllister et al. (2021) [45] | https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12835 (accessed on 27 July 2022) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| McCann et al. (2012) [47] | https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03836.x (accessed on 27 July 2022) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Moll et al. (2018) [49] | https://doi.org/10.3928/02793695-20180305-04 (accessed on 27 July 2022) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Montreuil et al. (2015) [50] | https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2015.1075235 (accessed on 27 July 2022) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Pitkänen et al. (2008) [51] | https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.03.003 (accessed on 27 July 2022) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Romeu-Labayen et al. (2022) [53] | https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12766 (accessed on 14 July 2022) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Rose et al. (2015) [54] | https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796013000693 (accessed on 27 July 2022) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Rydon (2005) [55] | https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-0979.2005.00363.x (accessed on 27 July 2022) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Santangelo et al. (2018) [56] | https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12317 (accessed on 27 July 2022) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Schneidtinger et al. (2019) [58] | https://doi.org/10.1111/jcap.12245 (accessed on 27 July 2022) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Shattell et al. (2007) [59] | https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-0349.2007.00477.x (accessed on 27 July 2022) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Stenhouse (2011) [61] | https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2010.01645.x (accessed on 27 July 2022) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Stewart et al. (2015) [62] | https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12107 (accessed on 27 July 2022) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Terry (2020) [63] | https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12676 (accessed on 27 July 2022) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Testerink et al. (2019) [64] | https://doi.org/10.1111/ppc.12275 (accessed on 27 July 2022) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Unclear | Yes |

| Wilson (2010) [66] | https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2010.01586.x (accessed on 27 July 2022) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes |

| Wortans et al. (2006) [67] | https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2006.00916.x (accessed on 27 July 2022) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

3.3. Service Users’ Views and Expectations of Mental Health Nurses

3.3.1. Satisfaction with Nursing Care

Nine studies (involving 1009 participants) examined service user satisfaction with mental health nursing care [28,34,35,38,40,41,57,60,65]. Service users generally reported they were satisfied with the mental health nursing care they received. For example, Saur et al. [57] surveyed 105 people with major depression who attended a primary care clinic. The authors stated that 78 [74%] service users assessed the quality of care received as excellent, and 91 [88%] reported being very satisfied with the care received [57].

3.3.2. Service User-Centred Care

Across six studies [33,36,44,48,51,62], service users consistently reported an expectation that MHNs should work in a service user-centred way. For example, Gunasekara et al. [33] interviewed 20 people with lived experience of inpatient psychiatric treatment to explore their perspectives on MHN care. Service users emphasised the importance of planning care around their specific needs and showing an interest in them as individuals [33].

3.3.3. Recovery-Focused Care

One hundred and forty-three service users participated in eight studies reporting views on how nurses supported their recovery [27,44,50,51,52,55,58,95]. Although participants across these studies did not spontaneously express, that mental health nurses were working in a recovery way, they did report expectations of aspects of care that are consistent with recovery-orientated practices. For example, a qualitative study involving nine participants by Schneidtinger & Haslinger-Baumann, [58] reported that service users viewed MHNs as supportive, accessible, and helped them develop new coping strategies, which they found supportive for their recovery. Another study by Rydon, [55] of 21 people with a mental ill-health diagnosis reported the importance of mental health nurses conveying hope to them as individuals and to their carers. Helping people to look beyond mental ill-health—engaging in hobbies and meaningful occupations—and supporting them in making their own decisions which are again recovery-focused expectations, was reported in the Pitkänen et al. [51]. Thirty-one people with mental ill-health participated in a qualitative study about their perspectives on recovery-focused care and aggression in the inpatient services [44]. Service users reported that engagement by mental health nurses in therapeutic interactions during crisis encouraged self-management of behaviour [a key component of recovery-focused care] [44].

3.3.4. Mental Health Nurse Flexibility

Across four included studies—all with a community focus—there was a narrative that service users viewed MHNs flexibility around the timings of meetings as particularly important and valuable [28,35,58,65].

3.3.5. Therapeutic Relationships

Involving 64 community dwelling people, the authors of four studies identified positive views from service users about the quality of their therapeutic relationships with MHNs [18,22,27,53,59]. Gerace et al. [27] and Shattell et al. [59] reported—from two qualitative studies involving seven and 20 participants—that service users reported that they were able to engage with MHNs in meaningful relationships.

3.3.6. Expectation of Interventions Delivered by Mental Health Nurses

The authors of 13 studies reported on service users’ expectations of the types of interventions delivered by mental health nurses [19,21,25,32,33,50,51,52,54,56,62,63,95]. Providing psychosocial support and fostering hope were identified as core interventions across multiple studies [50,51,52]. In one study, medication administration and assisting with self-care were identified by service users as examples of interventions they expect MHNs to deliver [95].

Gray & Brown, [32] conducted a qualitative study of 15 inpatients about MHNs’ physical health care. Generally, participants reported that physical health care was an important part of the work of MHNs but indicated that they often failed to pay adequate attention to addressing these needs [32].

Views of service users about the competencies of MHNs in delivering culturally congruent care were identified in one qualitative study of community dwelling participants [95]. The 15 African American adults viewed MHNs as reassuring, understanding, and supportive of their spiritual needs [95].

3.3.7. Important Qualities of Mental Health Nurses

The authors of two studies [36,55] involving 71 people with mental ill health in the community explored the values MHNs. Service users in both studies expected MHNs to treat them with respect, have a good understanding of mental ill-health, be supportive, non-discriminatory, non-stigmatizing, non-judgemental, convey hope, and a willingness to spend time talking with them [36,55].

3.3.8. Negative Views of Mental Health Nurses

Across 13 studies, services users reported notable negative views of mental health nurses, which included skills deficits, negative attitudes, and poor therapeutic engagement [20,23,25,32,42,43,44,45,48,55,59,61,62]. For example, in a study involving 119 inpatient service users from a single Mental Health service in England, the authors reported that MHNs seemingly lacked the necessary skills [but did not provide examples] to address their needs [62]. The authors reported that some service users viewed MHNs as uncaring, dismissive, and disrespectful [62]. In another study, Rose et al. [54] interviewed 37 inpatient service users with schizophrenia who reported that they rarely experienced a therapeutic relationship with MHNs on the ward [54]. In another study, inpatient service users viewed MHNs as not supportive and ineffective communicators who were quick to judge them as potentially aggressive when they expressed dissatisfaction with the care they received [44]. Not working in a collaborative way was reported by the authors of two qualitative studies [20,48]. McCloughen et al. [48] used focus groups and surveys of 18 inpatients service users. MHNs were viewed as being inaccessible and inflexible in by study participants [48].

3.3.9. Views of Mental Health Nurse Prescribers

Five studies involving 118 service users focused on service users’ views about the MHN prescribing [24,26,37,46,67]. In all five studies, service users talked about being given a choice and being more involved in decisions about their medication. Service users reported that MHN prescribers took time to build a positive therapeutic alliance and ensure that they provided detailed information about treatment options available to them [24,26,46,67]. Service users described MHN prescribers as supportive and non-judgemental [26], confident [67], prompt, courteous, responsive and thorough in their work, as well as able to communicate effectively [67].

3.4. Views and Expectations of Carers

The authors of 15 studies reported views and expectations of carers about MHNs that we have addressed under two headings: collaborating with carers and negative views [19,21,28,29,30,31,33,34,39,41,45,47,49,50,55,64].

3.4.1. Collaborating with Carers

A consistent expectation from carers that MHNs work collaboratively with them in supporting their relative was identified across seven studies [19,29,30,31,33,39,45,47]. For example, 17 carers were interviewed in a study by Kertchok [39], reporting that MHNs were generally collaborative, understood their concerns, gave them time to talk and provided information about how to care for their relatives [39].

3.4.2. Negative Views

The authors of five studies reported negative views of mental health nurses [29,30,31,45,47,64]. For example, in one study, carers reported frustration with the lack of interactions with MHNs regarding the treatment that their relatives were receiving and expressed concern that their views about how to care for their relatives were not considered [45]. McCann et al. [47] reported that carers considered their role as undervalued by MHNs who excluded them from meetings about care and treatment planning because of concerns about privacy and confidentiality. Carers viewed MHNs as not providing adequate information about service users’ illness and treatment [29,30,31].

Carers in one Australian study (number of participants not provided) reported that they were concerned that new nursing graduates—who had completed comprehensive nurse education—were not adequately prepared to work in psychiatric clinical settings [31].

4. Discussion

The aim of this systematic review was to extend and update the work by Bee et al. [7] that examined the views and expectations of mental health service users and carers about mental health nurses in the UK. We included 49 new studies published after the Bee et al. [7] systematic review. The methodological quality of included studies was generally poor, and the preponderance of qualitative studies limits the generalisability of the observations beyond the context of the research. Our results were consistent with those reported in the Bee et al. [7] review: service users were generally satisfied with the care they received from mental health nurses and considered that they provided good levels of psychosocial support. Across included studies, service users expressed concern about the quality of the therapeutic relationship with mental health nurses and low levels of collaborative working.

These observations are striking, given the profound shift over the past 15 years toward a recovery-orientated and, more recently, trauma-informed way of working [66,96]. Our findings may indicate that the necessary changes in mental health nursing practice have not occurred. Put bluntly, what mental health services say they provide and how nurses practice are starkly different. Our findings may be explained by a failure to support MHNs in developing the necessary competencies or a disregard by MHNs for this way of working.

Our review identified emergent expectations of mental health nurses around promoting recovery and addressing service users’ physical health that were not identified in the previous review.

Our findings are broadly consistent with other related reviews [97,98]. For example, Newman et al. [97] conducted an integrative literature of service users’ experiences of inpatient and community mental health services that included 34—predominantly qualitative—studies. Authors indicated that service users were rarely involved in decisions about their care [97]. In addition, Newman et al. [97] report that despite the lack of therapeutic relationships between service users and healthcare professionals, service users were satisfied with the quality of care they received, which is consistent with our findings. Eassom et al. [98] identified privacy concerns and confidentiality as barriers to carer engagement in a review of 43 studies involving 321 service users and 276 carers, which is again, consistent with our results.

The views and expectations of service users and carers about MHNs were similar. In some studies, for example, [31,62], service users and carers reported strikingly negative views about MHNs, which included deficits in fundamental skills to work in clinical environments. Although these were qualitative studies, and consequently, observations cannot be generalised, the research raises concerns about the quality of mental health nursing care service users receive. These findings are dissonant with the high levels of satisfaction reported in observational studies, which may be explained by high levels of social desirability bias in surveys of this type. To generate a deep understanding of the lived experience of mental health nursing care, large multi-centre qualitative research is required.

4.1. Limitations of the Evidence Included in the Review

Included studies had important methodological limitations that need to be considered when interpreting the findings of this review. Authors of surveys included in the review consistently relied on convenience sampling methods, for example, recruiting participants from a single clinical area or inpatient ward. Likely this may introduce selection bias limiting the generalizability of the observations. The authors of many qualitative studies did not locate themselves culturally or theoretically, nor consider how their views and experiences may influence the study findings.

4.2. Limitations of the Review Processes

There were several limitations to the review process that need to be considered. Firstly, we did not include grey literature or studies not in the English language, which may mean that important work may have been omitted. The protocol for this review was registered with the Open Science Framework (OSF) [99] after initial searches were undertaken, consequently, we cannot demonstrate that our search strategy was not amended after the review had started, and this could be an important source of bias.

4.3. Implications of the Results for Practice

The implications for practice are limited by the poor methodological quality of included studies. Understanding mental health service users’ views and expectations of nurses requires research that is methodologically rigorous, appropriately powered and uses well validated measures. The preponderance of small qualitative studies adds little by way of contribution to knowledge and may confuse or distort the evidence base.

5. Conclusions

Service users’ and carers’ views and expectations of mental health nurses have not changed much qualitatively over the last 15 years. The emerging theme is that service users expect mental health nurses to provide recovery-focused care and attend to their physical health needs. However, the poor methodological quality of included studies is concerning and means that essentially meaningful conclusions cannot be made.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijerph191711001/s1, Document S1: Search strategies; Document S2: List of included studies; Document S3: List of excluded studies.

Author Contributions

N.M., M.J. and R.G. contributed to the study conception and design. N.M., D.K., N.A., A.J. and S.P. conducted title, abstract and full-text screening, risk of bias assessment, and data extraction. M.J. and R.G. resolved conflicts between the reviewers. N.M. performed data analysis and wrote the original draft. R.G. and M.J. supervised the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The corresponding author is supported by a La Trobe University Postgraduate Research Scholarship (LTUPRS) and Research Training Program (RTP)”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article and Supplementary Material.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the authors (David Giménez Díez and Martin Jones) who responded to our emails.

Conflicts of Interest

Two studies included in this review were conducted by R.G. and M.J. R.G. was an author on the Bee et al. [7] review.

References

- World Health Organization. Mental Health Atlas 2020; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- McKay, K.; Ariss, J.; Rudnick, A. RAISe-ing awareness: Person-centred care in coercive mental health care environments—A scoping review and framework development. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2021, 28, 251–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rock, D.; Cross, S.P. Regional planning for meaningful person-centred care in mental health: Context is the signal not the noise. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2020, 29, e104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carey, T.A. Beyond patient-centered care: Enhancing the patient experience in mental health services through patient-perspective care. Patient Exp. J. 2016, 3, 46–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanhope, V.; Solomon, P. Getting to the Heart of Recovery: Methods for Studying Recovery and their Implications for Evidence-Based Practice. Br. J. Soc. Work 2008, 38, 885–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, A.; Herrman, H. Involving patients, carers and families: An international perspective on emerging priorities. BJPsych Int. 2017, 14, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bee, P.; Playle, J.; Lovell, K.; Barnes, P.; Gray, R.; Keeley, P. Service user views and expectations of UK-registered mental health nurses: A systematic review of empirical research. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2008, 45, 442–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, K.S.; Ter Riet, G.; Glanville, J.; Sowden, A.J.; Kleijnen, J. Undertaking Systematic Reviews of Research on Effectiveness: CRD’s Guidance for Carrying Out or Commissioning Reviews; No. 4 (2n); NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination: York, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hungerford, C.; Fox, C. Consumer’s perceptions of Recovery-oriented mental health services: An Australian case-study analysis. Nurs. Health Sci. 2014, 16, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adams, R.J.; Smart, P.; Huff, A.S. Shades of Grey: Guidelines for Working with the Grey Literature in Systematic Reviews for Management and Organizational Studies. Int. J. Manag. Rev. 2017, 19, 432–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Higgins, J.P.T.; Deeks, J.J. Chapter 5: Collecting data. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 6.2; Higgins, J.P.T., Thomas, J., Chandler, J., Cumpston, M., Li, T., Page, M.J., Welch, V.A., Eds.; Updated February 2021. Cochrane. 2021; Available online: http://www.training.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed on 24 May 2022).

- Thomas, B.; Ciliska, D.; Dobbins, M.; Micucci, S. A process for systematically reviewing the literature: Providing the research evidence for public health nursing interventions. Worldviews Evid.-Based Nurs. 2004, 1, 176–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armijo-Olivo, S.; Stiles, C.R.; Hagen, N.A.; Biondo, P.D.; Cummings, G.G. Assessment of study quality for systematic reviews: A comparison of the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Tool and the Effective Public Health Practice Project Quality Assessment Tool: Methodological research. J. Eval. Clin. Pract. 2012, 18, 12–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q.; Pluye, P.; Fabregues, S.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, F.; Gagnon, M.P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; O’Cathain, A.; et al. Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT), Version 2018. Registration of Copyright (#1148552). Canadian Intellectual Property Office, Industry Canada. 2018. Available online: http://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/127916259/MMAT_2018_criteria-manual_2018-08-01_ENG.pdf (accessed on 22 May 2022).

- Lockwood, C.; Munn, Z.; Porritt, K. Qualitative research synthesis: Methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing meta-aggregation. Int. J. Evid.-Based Healthc. 2015, 13, 179–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popay, J.; Roberts, H.; Sowden, A.; Petticrew, M.; Arai, L.; Rodgers, M.; Britten, N.; Roen, K.; Duffy, S. Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews. ESRC Methods Programme. 2006. Available online: https://www.lancaster.ac.uk/media/lancaster-university/content-assets/documents/fhm/dhr/chir/NSsynthesisguidanceVersion1-April2006.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2022).

- Ådnøy Eriksen, K.; Arman, M.; Davidson, L.; Sundfør, B.; Karlsson, B. Challenges in relating to mental health professionals: Perspectives of persons with severe mental illness: Challenges in Relating to Professionals. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2014, 23, 110–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askey, R.; Holmshaw, J.; Gamble, C.; Gray, R. What do carers of people with psychosis need from mental health services? Exploring the views of carers, service users and professionals. J. Fam. Ther. 2009, 31, 310–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biringer, E.; Hove, O.; Johnsen, Ø.; Lier, H.Ø. “People just don’t understand their role in it.” Collaboration and coordination of care for service users with complex and severe mental health problems. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2021, 57, 900–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brimbelecombe, N.; Tingle, A.; Murrells, T. How mental health nursing can best improve service users’ experiences and outcomes in inpatient settings: Responses to a national consultation. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2007, 14, 503–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coatsworth-Puspoky, R.; Forchuk, C.; Ward-Griffin, C. Nurse-client processes in mental health: Recipients’ perspectives. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2006, 13, 347–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunningham, G.; Slevin, E. Community psychiatric nursing: Focus on effectiveness. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2005, 12, 14–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earle, E.A.; Taylor, J.; Peet, M.; Grant, G. Nurse prescribing in specialist mental health (Part 1): The views and experiences of practising and non-practising nurse prescribers and service users. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2011, 18, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, A.M.; Quinn, C.; McKenna, B.; Willis, K. Consumers living with psychosis: Perspectives on sexuality. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2021, 30, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frain, S.; Chambers, L.; Higgins, A.; Donohue, G. “Not Left in Limbo”: Service User Experiences of Mental Health Nurse Prescribing in Home Care Settings. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2021, 42, 660–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gerace, A.; Oster, C.; O’Kane, D.; Hayman, C.L.; Muir-Cochrane, E. Empathic processes during nurse–consumer conflict situations in psychiatric inpatient units: A qualitative study. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2018, 27, 92–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giménez-Díez, D.; Maldonado Alía, R.; Rodríguez Jiménez, S.; Granel, N.; Torrent Solà, L.; Bernabeu-Tamayo, M.D. Treating mental health crises at home: Patient satisfaction with home nursing care. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2020, 27, 246–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goodwin, V.; Happell, B. Conflicting agendas between consumers and carers: The perspectives of carers and nurses. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2006, 15, 135–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, V.; Happell, B. Consumer and carer participation in mental health care: The carer’s perspective: Part 1—The importance of respect and collaboration. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2007, 28, 607–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, V.; Happell, B. Consumer and carer participation in mental health care: The Carer’s Perspective: Part 2—Barriers to effective and genuine participation. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2007, 28, 625–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, R.; Brown, E. What does mental health nursing contribute to improving the physical health of service users with severe mental illness? A thematic analysis. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2017, 26, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunasekara, I.; Pentland, T.; Rodgers, T.; Patterson, S. What makes an excellent mental health nurse? A pragmatic inquiry initiated and conducted by people with lived experience of service use: What makes an excellent mental health nurse? Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2014, 23, 101–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Happell, B.; Sundram, S.; Wortans, J.; Johnstone, H.; Ryan, R.; Lakshmana, R. Assessing Nurse-Initiated Care in a Mental Health Crisis Assessment and Treatment Team in Australia. Psychiatr. Serv. 2009, 60, 1527–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Happell, B.; Palmer, C. The Mental Health Nurse Incentive Program: The Benefits from a Client Perspective. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2010, 31, 646–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horgan, A.; O Donovan, M.; Manning, F.; Doody, R.; Savage, E.; Dorrity, C.; O’Sullivan, H.; Goodwin, J.; Greaney, S.; Biering, P.; et al. ‘Meet Me Where I Am’: Mental health service users’ perspectives on the desirable qualities of a mental health nurse. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2021, 30, 136–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, M.; Bennett, J.; Lucas, B.; Miller, D.; Gray, R. Mental health nurse supplementary prescribing: Experiences of mental health nurses, psychiatrists and patients. J. Adv. Nurs. 2007, 59, 488–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keogh, B.; Brady, A.M.; Downes, C.; Doyle, L.; Higgins, A.; McCann, T. Evaluation of a Traveller Mental Health Liaison Nurse: Service User Perspectives. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2020, 41, 799–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kertchok, R. Building Collaboration in Caring for People with Schizophrenia. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2014, 35, 872–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, B.M.; Linette, D.; Donohue-Smith, M.; Wolf, Z.R. Relationship between Perceived Nurse Caring and Patient Satisfaction in Patients in a Psychiatric Acute Care Setting. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. Ment. Health Serv. 2019, 57, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koga, M.; Furegato, A.R.F.; Santos, J.L.F. Opinions of the staff and users about the quality of the mental health care delivered at a Family Health Program. Rev. Latino-Am. Enferm. 2006, 14, 163–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lees, D.; Procter, N.; Fassett, D. Therapeutic engagement between consumers in suicidal crisis and mental health nurses: Therapeutic Engagement and Suicidal Crisis. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2014, 23, 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lessard-Deschênes, C.; Goulet, M. The therapeutic relationship in the context of involuntary treatment orders: The perspective of nurses and patients. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2022, 29, 287–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, E.; Wynaden, D.; Heslop, K.D. Consumers’ Perceptions of Nurses Using Recovery-focused Care to Reduce Aggression in All Acute Mental Health Including Forensic Mental Health Services: A Qualitative Study. J. Recovery Ment. Health 2019, 2, 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- McAllister, S.; Simpson, A.; Tsianakas, V.; Robert, G. “What matters to me”: A multi-method qualitative study exploring service users’, carers’ and clinicians’ needs and experiences of therapeutic engagement on acute mental health wards. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2021, 30, 703–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, T.V.; Clark, E. Attitudes of patients towards mental health nurse prescribing of antipsychotic agents. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2008, 14, 115–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCann, T.V.; Lubman, D.I.; Clark, E. Primary caregivers’ satisfaction with clinicians’ response to them as informal carers of young people with first-episode psychosis: A qualitative study. J. Clin. Nurs. 2012, 21, 224–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCloughen, A.; Gillies, D.; O’Brien, L. Collaboration between mental health consumers and nurses: Shared understandings, dissimilar experiences. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2011, 20, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moll, M.F.; Pires, F.C.; Ventura, C.A.A.; Boff, N.N.; da Silva, N.F. Psychiatric Nursing Care in a General Hospital: Perceptions and Expectations of the Family/Caregiver. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. Ment. Health Serv. 2018, 56, 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montreuil, M.; Butler, K.J.D.; Stachura, M.; Pugnaire Gros, C. Exploring Helpful Nursing Care in Pediatric Mental Health Settings: The Perceptions of Children with Suicide Risk Factors and Their Parents. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2015, 36, 849–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitkänen, A.; Hätönen, H.; Kuosmanen, L.; Välimäki, M. Patients’ descriptions of nursing interventions supporting quality of life in acute psychiatric wards: A qualitative study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2008, 45, 1598–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rask, M.; Brunt, D. Verbal and social interactions in Swedish forensic psychiatric nursing care as perceived by the patients and nurses. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2006, 15, 100–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romeu-Labayen, M.; Tort-Nasarre, G.; Rigol Cuadra, M.A.; Giralt Palou, R.; Galbany-Estragués, P. The attitudes of mental health nurses that support a positive therapeutic relationship: The perspective of people diagnosed with BPD. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2022, 29, 317–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, D.; Evans, J.; Laker, C.; Wykes, T. Life in acute mental health settings: Experiences and perceptions of service users and nurses. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2015, 24, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rydon, S.E. The attitudes, knowledge and skills needed in mental health nurses: The perspective of users of mental health services. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2005, 14, 78–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santangelo, P.; Procter, N.; Fassett, D. Seeking and defining the ‘special’ in specialist mental health nursing: A theoretical construct. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2018, 27, 267–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saur, C.D.; Steffens, D.C.; Harpole, L.H.; Fan, M.Y.; Oddone, E.Z.; Unützer, J. Satisfaction and Outcomes of Depressed Older Adults with Psychiatric Clinical Nurse Specialists in Primary Care. J. Am. Psychiatr. Nurs. Assoc. 2007, 13, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneidtinger, C.; Haslinger-Baumann, E. The lived experience of adolescent users of mental health services in Vienna, Austria: A qualitative study of personal recovery. J. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2019, 32, 112–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shattell, M.M.; Starr, S.S.; Thomas, S.P. Take my hand, help me out: Mental health service recipients’ experience of the therapeutic relationship. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2007, 16, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sinclair, L.; Hunter, R.; Hagen, S.; Nelson, D.; Hunt, J. How effective are mental health nurses in A&E departments? Emerg. Med. J. 2006, 23, 687–692. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Stenhouse, R.C. “They all said you could come and speak to us”: Patients’ expectations and experiences of help on an acute psychiatric inpatient ward. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2011, 18, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stewart, D.; Burrow, H.; Duckworth, A.; Dhillon, J.; Fife, S.; Kelly, S.; Marsh-Picksley, S.; Massey, E.; O’Sullivan, J.; Qureshi, M.; et al. Thematic analysis of psychiatric patients’ perceptions of nursing staff. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2015, 24, 82–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, J. ‘In the middle’: A qualitative study of talk about mental health nursing roles and work. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2020, 29, 414–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testerink, A.E.; Lankeren, J.E.; Daggenvoorde, T.H.; Poslawsky, I.E.; Goossens, P.J.J. Caregivers experiences of nursing care for relatives hospitalized during manic episode: A phenomenological study. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2019, 55, 23–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wand, T.; Schaecken, P. Consumer evaluation of a mental health liaison nurse service in the Emergency Department. Contemp. Nurse J. Aust. Nurs. Prof. 2006, 21, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, A.; Hutchinson, M.; Hurley, J. Literature review of trauma-informed care: Implications for mental health nurses working in acute inpatient settings in Australia. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2017, 26, 326–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wortans, J.; Happell, B.; Johnstone, H. The role of the nurse practitioner in psychiatric/mental health nursing: Exploring consumer satisfaction. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2006, 13, 78–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, A.E.; Racher, F.; Clements, K. Person-centered Psychiatric Nursing Interventions in Acute Care Settings. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2019, 40, 682–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowen, M.; Mason, T. Forensic and non-forensic psychiatric nursing skills and competencies for psychopathic and personality disordered patients. J. Clin. Nurs. 2012, 21, 3556–3564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çelik Ince, S.; Partlak Günüşen, N.; Serçe, Ö. The opinions of Turkish mental health nurses on physical health care for individuals with mental illness: A qualitative study. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2018, 25, 245–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleary, A.; Dowling, M. Knowledge and attitudes of mental health professionals in Ireland to the concept of recovery in mental health: A questionnaire survey. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2009, 16, 539–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusack, E.; Killoury, F.; Nugent, L.E. The professional psychiatric/mental health nurse: Skills, competencies and supports required to adopt recovery-orientated policy in practice. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2017, 24, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannouli, H.; Perogamvros, L.; Berk, A.; Svigos, A.; Vaslamatzis, G. Attitudes, knowledge and experience of nurses working in psychiatric hospitals in Greece, regarding borderline personality disorder: A comparative study. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2009, 16, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, V.; Happell, B. In our own words: Consumers’ views on the reality of consumer participation in mental health care. Contemp. Nurse 2006, 21, 4–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, V.; Happell, B. To be treated like a person: The role of the psychiatric nurse in promoting consumer and carer participation in mental health service delivery. J. Contrib. 2008, 14, 1766–1775. [Google Scholar]

- Happell, B.; Palmer, C.; Tennent, R. The Mental Health Nurse Incentive Program: Desirable knowledge 2008, skills and attitudes from the perspective of nurses. J. Clin. Nurs. 2011, 20, 901–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawamdeh, S.; Fakhry, R. Therapeutic relationships from the psychiatric nurses’ perspectives: An interpretative phenomenological study. Perspect. Psychiatr. Care 2014, 50, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurley, J. A qualitative study of mental health nurse identities: Many roles, one profession. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2009, 18, 383–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, C.; Morrissey, J.; Donohue, G. Mental health nurses’ perceived preparedness to work with adults who have child sexual abuse histories. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2021, 28, 384–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-W.; Salyers, M.P. Attitudes and Perceived Barriers to Working with Families of Persons with Severe Mental Illness: Mental Health Professionals’ Perspectives. Community Ment. Health J. 2008, 44, 337–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakeman, R. What is good mental health nursing? A Survey of Irish Nurses. Arch. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2012, 26, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeod, K.; Simpson, A. Exploring the value of mental health nurses working in primary care in England: A qualitative study. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2017, 24, 387–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Poyato, A.R.; Rodríguez-Nogueira, Ó. The association between empathy and the nurse–patient therapeutic relationship in mental health units: A cross-sectional study. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2021, 28, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munro, A.; Watson, H.; McFadyen, A. Assessing the impact of training on mental health nurses’ therapeutic attitudes and knowledge about co-morbidity: A randomised controlled trial. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2007, 44, 1430–1438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nardella, N.; Hooper, S.; Lau, R.; Hutchinson, A. Developing acute care-based mental health nurses’ knowledge and skills in providing recovery-orientated care: A mixed methods study. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2021, 30, 1170–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pounds, K.G. Client-Nurse Interaction with Individuals with Schizophrenia: A Descriptive Pilot Study. Issues in Mental Health Nursing 2010, 31, 770–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, R.; Escott, P.; Isobel, S. Collaboration as a process and an outcome: Consumer experiences of collaborating with nurses in care planning in an acute inpatient mental health unit. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2018, 27, 1204–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Romeu-Labayen, M.; Cuadra, M.A.R.; Galbany-Estragués, P.; Corbal, S.B.; Palou, R.M.G.; Rn, G.T. Borderline personality disorder in a community setting: Service users’ experiences of the therapeutic relationship with mental health nurses. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2020, 29, 868–877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, R.; Garlick, R.; Happell, B. Exploring the role of the mental health nurse in community mental health care for the aged. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2006, 27, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sclafani, M.; Caldwell, B.; Fitzgerald, E.; Mcquaide, T.A. Implementing the Clinical Nurse Specialist Role in a Regional State Psychiatric Hospital. Clin. Nurse Spec. 2008, 22, 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, B. Relationships between positive and negative attributes of self-compassion and perceived caring efficacy among psychiatric-mental health nurses. J. Psychosoc. Nurs. Ment. Health Serv. 2020, 58, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, L.; Gwinner, K. Have you got what it takes? Nursing in a Psychiatric Intensive Care Unit. J. Ment. Health Train. Educ. Pract. 2015, 10, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, M.R.; Stein-Parbury, J.; Orr, F.; Dawson, A. Working with consumers who hear voices: The experience of early career nurses in mental health services in Australia. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2019, 28, 605–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, W.; Chen, S. Nurses’ perceptions on and experiences in conflict situations when caring for adolescents with anorexia nervosa: A qualitative study. Int. J. Ment. Health Nurs. 2021, 30, 1386–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, D.W. Culturally competent psychiatric nursing care. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2010, 17, 715–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Boutillier, C.; Chevalier, A.; Lawrence, V.; Leamy, M.; Bird, V.J.; Macpherson, R.; Williams, J.; Slade, M. Staff understanding of recovery-orientated mental health practice: A systematic review and narrative synthesis. Implement. Sci. 2015, 10, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Newman, D.; O’Reilly, P.; Lee, S.H.; Kennedy, C. Mental health service users’ experiences of mental health care: An integrative literature review: Service users’ experiences of Mental Health Care. J. Psychiatr. Ment. Health Nurs. 2015, 22, 171–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Eassom, E.; Giacco, D.; Dirik, A.; Priebe, S. Implementing family involvement in the treatment of patients with psychosis: A systematic review of facilitating and hindering factors. BMJ Open 2014, 4, e006108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moyo, N. Service User Views and Expectations of Mental Health Nurses: An Updated Systematic Review. 2022. (accessed on 1 September 2022). [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).