Abstract

Breast cancer (BC) is the most frequent tumour affecting women all over the world. In low- and middle-income countries, where its incidence is expected to rise further, BC seems set to become a public health emergency. The aim of the present study is to provide a systematic review of current BC screening programmes in WHO European Region to identify possible patterns. Multiple correspondence analysis was performed to evaluate the association among: measures of occurrence; GNI level; type of BC screening programme; organization of public information and awareness campaigns regarding primary prevention of modifiable risk factors; type of BC screening services; year of screening institution; screening coverage and data quality. A key difference between High Income (HI) and Low and Middle Income (LMI) States, emerging from the present data, is that in the former screening programmes are well organized, with approved screening centres, the presence of mobile units to increase coverage, the offer of screening tests free of charge; the fairly high quality of occurrence data based on high-quality sources, and the adoption of accurate methods to estimate incidence and mortality. In conclusion, the governments of LMI countries should allocate sufficient resources to increase screening participation and they should improve the accuracy of incidence and mortality rates.

1. Introduction

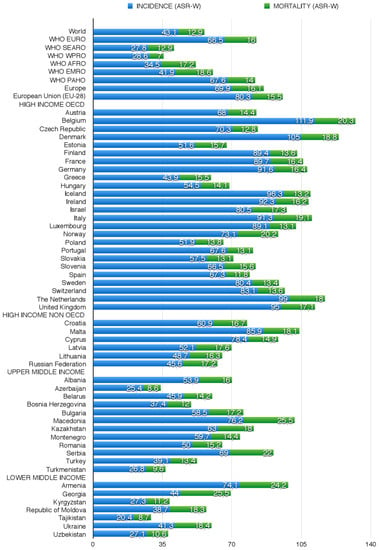

Breast cancer (BC) is the most frequent tumour affecting women all over the world, with an incidence rate of 43.1 (per 100,000 ASR-W), a mortality rate of 12.9 (per 100,000 ASR-W), and a 5-year prevalence of 239.9 [1]. In low- and middle-income countries, where its incidence is expected to rise further, BC seems set to become a public health emergency [2], while the highest incidence rates, reported in high-income countries, are partially to be attributed to earlier screening detection [3].

Indeed, in the WHO European Region rates are higher than global rates, incidence being 66.5 (per 100,000 ASR-W) and mortality 16.0 (per 100,000 ASR-W). In EU-28 countries the incidence rate is 80.3 (per 100,000 ASR-W) and the mortality rate 14.4 (per 100.000 ASR-W) [1]. Most EU-28 countries [4], including the UK [5,6,7,8], France [9,10], Italy [11], and Belgium [12,13,14,15], have national cancer prevention population-based (PB) screening programmes not only for BC, but also for cervical cancer (CC) [16] and, as of recently, colorectal cancer (CRC) [17,18]. Within the Council of Europe (CoE), which includes the EU-28 member States (MS) and 19 other countries [18], the right to health is enshrined in the “Right to Protection of Health” [19] and in Article 3 of the Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine (equal conditions for access to health services) [20,21,22].

In Europe, population-based (PB) mammography screening has reduced mortality by 25%–31%, and by 38%–48% in women receiving adequate follow-up [14]. The level of evidence regarding the usefulness of mammography in reducing mortality in women aged 50 to 74 years is “sufficient” [5].

The risk of developing BC is affected by some non-modifiable factors (e.g., age, genetic and familial risk) [23] and by others that can be modified, which are related to lifestyle (e.g., alcohol abuse, tobacco use, and body mass index) [24,25]. Prevention campaigns to reduce the risk attributable to modifiable risk factors should therefore be conducted in all countries.

The aim of the present study is to provide a systematic review of current BC screening programmes in WHO European Region countries to identify possible differences among countries based on gross national income (GNI) [26].

2. Materials and Methods

The WHO European area, which is supervised by the WHO EURO office based in Copenhagen (Denmark), includes 53 countries: Albania, Andorra, Armenia, Austria, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Belgium, Bosnia, Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Georgia, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Monaco, Montenegro, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, the Republic of Moldova, the Russian Federation, Romania, San Marino, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Tajikistan, the FYR of Macedonia, Turkey, Turkmenistan, Ukraine, the UK, and Uzbekistan. For the purposes of this study, they were grouped according to GNI level referred to per capita Gross National Income (current US$), as indicated by the World Bank [26]: lower-middle income (LMI), $1,026–$4,035; upper-middle income (UMI), $4,036–$12,475; high income (HI), $12,476 or more, and HI OECD countries (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development), whose average income is $29,016.

2.1. Sources of WHO European Epidemiological Data: Search Strategy

The main data source was the GLOBOCAN 2012 website of the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), which provides access to several databases that enable assessing the impact of BC in 184 countries or territories in the world [1,27]. Additional sources were the WHO, IARC, EUCAN and NORDCAN, the European Network of Cancer Registries (ENCR), volume X of the CI5, and the Ministerial and Public Health Agency websites of the individual countries.

A PubMed search was conducted using Early Cancer Detection OR Cancer Screening OR Screening, Cancer OR Cancer Screening Test OR Early Diagnosis of Cancer OR Cancer Early Diagnosis AND Breast Neoplasm OR Neoplasm, Breast OR Tumours, Breast OR Breast Cancer OR Cancer, Breast OR Mammary Cancer OR Breast Carcinoma AND Europe; Early Cancer Detection OR Cancer Screening OR Screening, Cancer OR Cancer Screening Test OR Early Diagnosis of Cancer OR Cancer Early Diagnosis AND Breast Neoplasm OR Neoplasm, Breast OR Tumours, Breast OR Breast Cancer OR Cancer, Breast OR Mammary Cancer OR Breast Carcinoma AND “state name”. Only works published in English in the previous 10 years were considered. A MeSH search was conducted using ((“Breast Neoplasms”[Mesh]) AND “Early Detection of Cancer”[Mesh]) AND Europe; ((“Breast Neoplasms”[Mesh]) AND “Early Detection of Cancer”[Mesh]) AND “state name” for each country.

The EMBASE database did not provide further relevant results. The registries of some websites and the www.cochranelibrary.com, Scopus, www.clinicaltrials.gov, www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu, Research gate, and Google databases and the national sites of patients’ association were also consulted. All works reporting information considered relevant for the systematic review were examined.

2.2. Data Synthesis

The 1-, 3-, and 5-year standardized prevalence rates per 100,000 population (ASR-W) for 2012 are reported in Table 1. Incidence and mortality data and their age-standardized rates per 100,000 population (ASR-W) for 2012 are reported in Figure 1. The quality of the epidemiological data of each country, based on Data Sources and Methods according to Mathers [28], is compared in Table 4. The data concerning national primary and secondary prevention campaigns are reported in Table 2. Finally, the information regarding BC screening programmes in the WHO European region is shown in Table 3.

Table 1.

Breast Cancer prevalence for each country of WHO European Region by gross income levels according to World Bank.

Figure 1.

Breast Cancer Incidence and Mortality data and their age standardized rates per 100,000 population (ASR-W), in WHO European Region Countries and in the World, according to GLOBOCAN 2012 (Andorra, Monaco and San Marino not reported).

Table 4.

Epidemiological data quality for the 53 WHO European area nations.

Table 2.

Campaigns of primary prevention and screening promotion in 53 WHO European Countries.

Table 3.

Distribution of Breast Cancer screening programmes in 53 WHO European Countries as of July 2016.

2.3. Correspondence Statistical Analysis

Multiple correspondence analysis was performed to evaluate the association among the following variables and identify possible patterns: measures of occurrence (BC incidence, mortality, and prevalence); GNI level (LMI, UMI, and HI); type of BC screening programme in place (national PB/non-national PB; spontaneous/organized) [1,20]; organization of public information and awareness campaigns regarding primary BC prevention (yes/no) of modifiable risk factors (tobacco use, alcohol, obesity, and sedentary lifestyle); type of BC screening services (public health services/public health services + mobile units); year of screening institution (before 2001, 2001 to 2005, after 2005); screening coverage (<50%, 50%–75%, >75%), and data quality. The latter measures included the availability of incidence data, the availability of mortality data, the method adopted to estimate incidence rates, and the method used to estimate mortality rates. As in a previous study by our group [94], these variables were coded as dummy or ordinal variables, as appropriate, and incorporated into the model. Data quality was grouped and defined according to:

- The availability of incidence data (three categories): “high quality”, from A to C (A = national data or high-quality regional data, coverage > 50%; B = regional data, coverage between 10 and 50%); C = regional data, coverage < 10%); “medium quality”, from D to E (D = national data, rates; E = regional data, rates; and “low quality”, from F to G (F = frequency; G = no data) [28].

- The availability of mortality data (three categories): “high/medium”, from 1 to 2 (1–2 quality complete vital registration); “low”, 3 to 4 (3 = quality complete vital registration, 4 = incomplete or sample vital registration); and “incomplete or absent”, from 5 to 6 (% = other sources: cancer registries, autopsy, etc; 6 = no data) [28].

- The quality of the method adopted to estimate incidence rates (three categories): “high” (1). rates projected to 2012 (38 countries); “medium” (from 2 to 4): (2). Most recent rates applied to 2012 population (20 countries), (3). Estimated from national mortality by modelling, using incidence mortality ratios derived from recorded data in country-specific cancer registries (13 countries), (4). Estimated from national mortality estimates by modelling, using incidence mortality ratios derived from recorded data in local cancer registries in neighbouring countries (nine European countries); “low” (from 5 to 9): (5). Estimated from national mortality estimates using modelled survival (32 countries), (6). Estimated as the weighted average of the local rates (16 countries), (7). One cancer registry covering part of a country is used as representative of the country profile (11 countries), (8). Age/sex specific rates for "all cancers" were partitioned using data on relative frequency of different cancers (by age and sex) (12 countries), (9). The rates are those of neighbouring countries or registries in the same area (33 countries) [28].

- The quality of the method used to estimate mortality rates (three categories): “high” (1). rates projected to 2012 (69 countries); “medium” (from 2 to 4): (2). Most recent rates applied to 2012 population (26 countries), (3). Estimated as the weighted average of regional rates (1 country), (4). Estimated from national incidence estimates by modelling, using country-specific survival (two countries); “low” (from 5 to 6): (5). Estimated from national incidence estimates using modelled survival (83 countries). (6). The rates are those of neighbouring countries or registries in the same area (3 countries) [28].

Finally, incidence, 5-year prevalence, and mortality data were grouped into the following classes, respectively: ≤10/100,000/population, from 10.1 to 20/100,000, from 20.1 to 30/100,000, >30/100,000), ≤100/100,000, 101–150/100,000, 151–200/100,000, 201–250/100,000, >250/100,000), ≤5/100,000, from 5.1 to 10, from 10.1 to 15 and >15/100,000. SAS/STAT software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) was used for statistical analysis.

3. Results

3.1. Systematic Review

3.1.1. High-Income OECD Countries

The group of HI OECD countries includes 25 States, 21 EU MS (Austria, Belgium, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, and UK), three CoE MS (Iceland, Norway, Switzerland), and a country with observer status in the CoE (Israel).

The highest BC incidence rates are found in Belgium (111.9), the Netherlands (99), and the UK (95) (vs. 80.3 in EU-28 and 66.5 in the WHO European region) and the lowest in Greece (43.9), Estonia (51.6), Poland (51.9), and Hungary (54.5). Mortality rates are highest in Belgium (20.3), Norway (20.2), Italy (19.1), and Denmark (18.8), and lowest in Spain (11.8), Slovakia (13.1), Portugal (13.1), and Sweden (13.4) (Figure 1).

The 1-year prevalence of BC is > 200 in Denmark and Belgium; its 3-year prevalence is >500 in Denmark, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Finland; and its 5-year prevalence is >800 in Belgium, Denmark, the Netherlands, and Finland. The lowest 1-year and 5-year prevalence rates are found in Greece and Estonia, respectively (Table 1).

In 22 of these 25 countries, data quality is high (A–C) as regards the availability of incidence data, medium/high (1–3) for the mortality data, and medium/high (1–3) for the quality of the method adopted to estimate incidence and mortality rates (Table 4).

Public information and awareness campaigns for primary cancer prevention seem to be more common in the States with a universal health service and in Mediterranean countries (Table 2). Organized BC screening programmes are active in all HI OECD countries except Greece, Czech Republic, Slovakia, and some Swiss cantons, with some differences in the target population (Table 3). In the Czech Republic, a campaign directed at women of screening age who had failed to screen was organized in 2014; nonetheless, screening remains spontaneous, meaning that mammography is prescribed by a specialist (senologist or gynaecologist). In Slovakia and Greece there is no mention of organized screening programmes. In Austria, a national screening programme adopted in 2014 (Brustkrebs-Früherkennungs programm) involves rounds at 2-year intervals. Its target population are 45–69 year olds, who are given an e-card offering a mammogram at an approved public or private centre free of charge. Women aged 40–44 years and those aged 70 years or older can also obtain BC screening free of charge, again through activation of an e-card.

3.1.2. High-Income non-OECD Countries

This group includes nine countries, five EU-28 MS (Croatia, Cyprus, Latvia, Lithuania, and Malta) and four CoE MS (Andorra, Monaco, San Marino, and Russian Federation). BC incidence and mortality rates are highest in Malta (85.9; 18.1); incidence is lowest in the Russian Federation (45.6), and mortality is lowest in Cyprus (14.9) (Figure 1). The highest 1-, 3-, and 5-year prevalence rates are found in Malta and the lowest in the Russian Federation.

Public information and awareness campaigns for primary cancer prevention are carried out in nearly all of these States. All have organized BC screening programmes except the Russian Federation, where screening is spontaneous.

In five of these nine countries, data quality is high (A-C) as regards the availability of incidence data, medium/high (1–3) for mortality data, and medium/high (1–3) for the quality of the method applied to estimate incidence and mortality (Table 4). Three countries are not evaluable.

3.1.3. Upper/Middle-Income Countries

This group includes 12 States: Albania (CoE), Azerbaijan (CoE), Belarus, the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina (CoE), Bulgaria (EU-28), Kazakhstan, Montenegro (CoE), Romania (EU-28), Republika Srpska (CoE), the FYR of Macedonia (CoE), Turkey (CoE), and Turkmenistan. The FYR of Macedonia has the highest incidence (76.2), mortality (25.5), and prevalence rates as well as 1-, 3-, and 5-year BC prevalence. Incidence and mortality are lowest in Azerbaijan (respectively 25.4 and 8.6), whereas the lowest 1-, 3-, and 5-year prevalence rate is found in Turkmenistan (Figure 1 and Table 1 respectively).

BC screening is PB and nationwide in Kazakhstan, Serbia, the FYR of Macedonia, and Turkey (Table 3); it is PB but local/regional in Belarus and Bosnia and Herzegovina; and is spontaneous in Albania, Bulgaria, and Romania. There is no evidence of BC screening in Azerbaijan or Turkmenistan (Table 3).

Data quality is high (A–C) as regards the availability of incidence data in three countries; medium/high (1–3) for mortality data in four countries; and medium/high (1–3) for the quality of the method used to estimate incidence in three countries. In all but two countries the quality of the method used to estimate mortality is high (Table 4).

3.1.4. Lower/Middle-Income Countries

This group includes seven countries: Armenia, Georgia, Republic of Moldova, and Ukraine (all CoE MS), Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan. BC incidence is highest in Armenia (74.1) and mortality in Georgia (25.5); 1-, 3-, and 5-year prevalence peaks in Armenia and is lowest in Tajikistan. PB screening programmes are active in Georgia, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan; they are also reported in Ukraine in 2002–2006, but they are no longer mentioned. In the other countries there is no evidence of BC screening.

In two of these seven countries data quality is medium/high (A–C) for data source incidence, medium/high (1–3) for data source mortality; the quality of the method used to estimate mortality is medium/high (1–3) (Table 4).

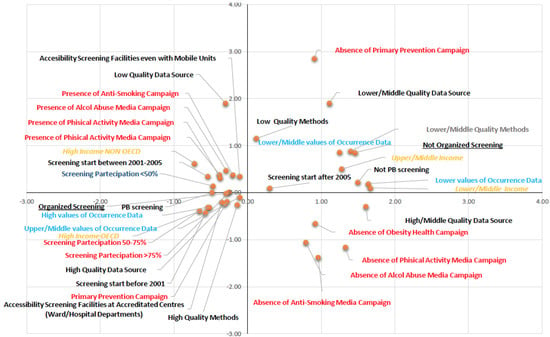

3.2. Correspondence Analysis

The results of multiple correspondence analysis are represented in Figure 2 (object scores plot). The data provided two dimensions with eigenvalues that explain 65% of the variance: dimension 1 = 0.40 and dimension 2 = 0.25. The first dimension is related to GNI level, year of BC screening institution, type of screening programme in place, and occurrence data; the second dimension relates to the quality of the availability of mortality data, the quality of the method applied to estimate incidence and mortality, and the organization of public information and awareness campaigns for primary prevention of risk factors (tobacco use, alcohol abuse, obesity, and sedentary lifestyle). Multiple correspondence analysis produced clear and interesting patterns, which are represented in the four quadrants of Figure 2. The right upper quadrant is characterized by medium/low GNI, absence of public information and awareness campaigns for primary prevention, low/medium quality of data availability, low quality of the method applied to estimate occurrence rates, low/medium quality of occurrence data, and institution of non-PB organized screening after 2005. The variables found in the left lower quadrant include: HI GNI OECD countries, organized PB screening, 50%–75% and >75% coverage, access to organized PB screening centres, institution of screening programmes before 2001, use of primary prevention public information and awareness campaigns, high/medium-high quality of occurrence data, high quality of the method applied to estimate data, and high quality data availability. The right lower quadrant shows the categories relating to the absence of public information and awareness campaigns for the primary prevention of the risk factors considered in the study (alcohol abuse, tobacco use, obesity, and sedentary lifestyle). Finally, the variables found in the upper left quadrant include HI GNI non-OECD countries, organization of public information and awareness campaigns for the primary prevention of the risk factors considered, institution of screening programmes since 2001–2005, screening coverage <50%, access to approved screening centres, use of mobile units to increase participation, and low-quality data availability.

Figure 2.

Results of multiple correspondence analysis.

4. Discussion

Over the past three decades, the number of new BC cases has more than doubled worldwide. European incidence and mortality rates vary widely, the highest being found in Belgium (HI; respectively 111.9 and 20.3) and the lowest in Tajikistan (LMI; 20.4 and 8.7). The incidence of BC in developing countries has been increasing by an annual rate of 4.4%. An encouraging finding is that in the countries that have enacted BC screening programmes (all HI States) mortality rates are declining [4]. It has been estimated that 68,000 women aged 15 to 49 years died from BC in LMIs in 2010 as opposed to only 26,000 in HI States [95]. In fact, outcomes in HI countries have improved due to a combination of early screening detection and better treatment [3]. In 1980, 37 women in every 100 new cases died in developing countries; in 2010 the figure was 26 [96]. In contrast, a reduction in the age at BC onset in developing countries is a matter for concern, since these patients account for 44.1% of all cases, while in HI countries BC has become less frequent among women of reproductive age [32]. Mortality would thus appear to correlate inversely with GNI. Mortality rates are a valuable measure of the problem and burden of BC in a country and of the effectiveness of secondary prevention through early detection. Moreover, cancer-specific mortality rates are useful to evaluate the impact of cancer management and treatment. In fact, in developed countries the combination of cancer prevention, early detection, and better treatment has reduced the incidence and mortality of the most common tumours [97,98]. Incidence rates may provide a valuable indicator to investigate risk factors and plan the adoption of prevention programmes. However, their estimation must be accurate if the phenomenon is not to be underestimated, and the absence of a PB or hospital-based cancer registry may be the cause of suboptimal accuracy of data sources. As demonstrated by the data reported above, a very different data quality is found in HI and LMI States, both in terms of the available data sources and of the methods applied to estimate incidence and mortality. This should prompt governments to invest in data source upgrading, to achieve an assessment of the tumour burden as accurate as possible, also with a view to optimising the demand and supply of diagnostic and treatment services. It should also be stressed that high rates of BC detected in advanced phases should prompt the organization of prevention campaigns.

According to the present study, not all HI countries employ awareness campaigns to prevent important risk factors such as tobacco use and alcohol abuse. HI States lacking them include Austria, Denmark, France, Iceland, and the Netherlands, a UMI country like Bulgaria, and LMI States like Georgia, and Ukraine. The same is true of the prevention of overweight and the promotion of exercise. As regards the enhancement of screening participation, HI States harness multiple means of communication that are sometimes provided in different languages, whereas awareness campaigns in LMI are organized only in Macedonia, Republika Srpska, and Turkey. It is worth stressing that with the exception of Kyrgyzstan, none of the LMI States use mobile units to reach the fraction of the target population who do not respond to the screening invitation. A key difference between HI and LMI States, emerging from the present data, is that in the former screening programmes are well organized, with approved screening centres, the presence of mobile units to increase coverage, the offer of screening tests free of charge; the fairly high quality of occurrence data based on high- quality sources, and the adoption of accurate methods to estimate incidence and mortality, whose accuracy is supported by cancer registries and PB screening.

5. Conclusions

The study suggests the following considerations: first of all, HI Countries like Slovakia, some Swiss cantons, the Russian Federation, and Greece, lack population-based (PB) screening; countries such as Austria, Denmark, France, Iceland, and the Netherlands lack prevention campaigns for the risk factors; countries such as Greece, Hungary, Luxemburg, and Russia lack high-quality data either in terms of data source and of the quality of the method used to estimate incidence and mortality rates. The governments of HI countries should allocate sufficient resources to increase screening participation by harnessing mobile units as well as devising campaigns to enhance women’s awareness of the importance of early BC diagnosis, a goal that would also ensure a more rational utilization of existing approved centres; secondly, they should improve the accuracy of incidence and mortality rates by upgrading the quality of data sources, to avoid being faced with large numbers of BC patients (also) with advanced disease in the near future. High-quality occurrence data are essential to understand cancer trends and devise control strategies. As regards low-middle income countries, they have a less efficient general organization, and the proportion of organized programmes is low in low-income countries while programmes are often absent in middle-income countries. It should however be stressed that for a screening programme to be effective the country should also have suitable facilities to manage all the new cases resulting from early diagnosis, as well as resources to ensure their follow-up. Therefore, small communities lacking specialized medical staff or economic resources to set up screening programmes could rely on nearby centres or regions having the resources and facilities for quality screening.

Author Contributions

Emma Altobelli contributed to this paper with conception and design of the study, literature review, developed statistical analysis, drafting and critical revision and editing. Leonardo Rapacchietta participated to literature search, participated to build database. Paolo Matteo Angeletti participated to literature search, acquired the data and participated in writing the paper. Luca Barbante, Filippo Valerio Profeta and Roberto Fagnano participated to acquire the data. All authors have approved the final version of manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Dikshit, R.; Eser, S.; Mathers, C.; Rebelo, M.; Parkin, D.M.; Forman, D.; Bray, F. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: Sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int. J. Cancer 2015, 136, E359–E386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bray, F.; Ren, J.S.; Masuyer, E.; Ferlay, J. Global estimates of cancer prevalence for 27 sites in the adult population in 2008. Int J Cancer 2013, 132, 1133–1145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weir, H.K.; Thun, M.J.; Hankey, B.F.; Ries, L.A.; Howe, H.L.; Wingo, P.A.; Jemal, A.; Ward, E.; Anderson, R.N.; Edwards, B.K. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2000, featuring the uses of surveillance data for cancer prevention and control. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2003, 95, 1276–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altobelli, E.; Lattanzi, A. Breast cancer in European Union: an update of screening programmes as of March 2014. Int. J. Oncol. 2014, 45, 1785–1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breast Cancer Breast Screening Programme, England Statistics for 2014–2015. Available online: http://www.hscic.gov.uk/catalogue/PUB20018/bres-scre-prog-eng-2014-15-rep.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2017).

- Northern Ireland Breast Screening Programme Annual Report & Statistical Bulletin. Available online: http://www.cancerscreening.hscni.net/pdf/BREAST_ANNUAL_REPORT_2011-12_Version_4_13_Aug_13.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2017).

- Screening Division of Public Health Wales BTW Programme Performance Report 2014-15. Available online: http://www.breasttestwales.wales.nhs.uk/reports-1 2011-2012 (accessed on 7 January 2017).

- Scottish Breast Screening Programme Statistics Year Ending 31 March 2015. Available online: https://www.isdscotland.org/Health-Topics/Cancer/Publications/2016-04-19/2016-04-19-SBSP-Cancer-Summary.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2017).

- Programme de dépistage du cancer du sein en France: résultats 2006 Institut de veille sanitaire. Available online: http://www.invs.sante.fr/publications/2009/plaquette_depistage_cancer_sein_2006/depistage_cancer_sein_2006.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2017).

- Institut de Veille Sanitaire Programme de Dépistage du Cancer du Sein en France: Résultats 2007–2008, évolutions Depuis 2004. Available online: http://www.invs.sante.fr/publications/2011/programme_depistage_cancer_sein/plaquette_depistage_cancer_sein.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2017).

- Giordano, L.; Castagno, R.; Giorgi, D.; Piccinelli, C.; Ventura, L.; Segnan, N.; Zappa, M. Breast cancer screening in Italy: evaluating key performance indicators for time trends and activity volumes. Epidemiol. Prev. 2015, 39 (Suppl. S1), 30–39. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- De Gauquier, K.; Remacle, A.; Fabri, V.; Mertens, R. Evaluation of the first round of the national breast cancer screening programme in Flanders, Belgium. Arch. Public Health 2006, 64, 71–80. [Google Scholar]

- A Van Steen Laat je Borsten Zien: Doen of Niet? Resultaten Screening. Available online: http://www.zol.be/sites/default/files/deelsites/medischebeeldvorming/verwijzers/sympoisa/20140920/dr.-van-steen-laat-je-borsten-zien-doen-of-niet.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2017).

- Broeders, M.; Moss, S.; Nyström, L.; Njor, S.; Jonsson, H.; Paap, E.; Massat, N.; Duffy, S.; Lynge, E.; Paci, E. The impact of mammographic screening on breast cancer mortality in Europe: A review of observational studies. J. Med. Screen. 2012, 19 (Suppl. S1), 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauby-Secretan, B.; Scoccianti, C.; Loomis, D.; Benbrahim-Tallaa, L.; Bouvard, V.; Bianchini, F.; Straif, K.; International Agency for Research on Cancer Handbook Working Group. Breast-cancer screening—Viewpoint of the IARC Working Group. New Engl. J. Med. 2015, 372, 2353–2358. [Google Scholar]

- Altobelli, E.; Lattanzi, A. Cervical carcinoma in the European Union: An update on disease burden, screening program state of activation, and coverage as of March 2014. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2015, 25, 474–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altobelli, E.; Lattanzi, A.; Paduano, R.; Varassi, G.; di Orio, F. Colorectal cancer prevention in Europe: Burden of disease and status of screening programs. Prev. Med. 2014, 62, 132–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altobelli, E.; D'Aloisio, F.; Angeletti, P.M. Colorectal cancer screening in countries of European Council outside of the EU-28. World J. Gastroenterol. 2016, 22, 4946–4957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- European Council. Council recommendation of 2 December 2003 on cancer screening (2003/878/EC). Off. J. Eur. Union 2003, L327, 34–38. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Report from the Commission to the Council, the European Parliament, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions Implementation of the Council Recommendation of 2 December 2003 on Cancer Screening (2003/878/EC) Brussels, 22.12.2008 COM (2008) 882. 2008. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/health//sites/health/files/major_chronic_diseases/docs/2nd_implreport_cancerscreening_co_eppac_en.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2017).

- Charter of fundamental rights of the European Union. Official Journal of the European Communities 2000/C 364/01. Available online: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/charter/pdf/text_en.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2017).

- Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Dignity of the Human Being with Regard to the Application of Biology and Medicine: Convention on Human Rights and Biomedicine. ETS No. 164. Available online: http://www.coe.int/it/web/conventions/full-list/-/conventions/treaty/164 (accessed on 7 January 2017).

- Skol, A.D.; Sasaki, M.M.; Onel, K. The genetics of breast cancer risk in the post-genome era: Thoughts on study design to move past BRCA and towards clinical relevance. Breast Cancer Res. 2016, 18, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Solis, M.A.; Maya-Nuñez, G.; Casas-González, P.; Olivares, A.; Aguilar-Rojas, A. Effects of the lifestyle habits in breast cancer transcriptional regulation. Cancer Cell Int. 2016, 16, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yung, R.L.; Ligibel, J.A. Obesity and breast cancer: risk, outcomes, and future considerations. Clin. Adv. Hematol. Oncol. 2016, 14, 790–797. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- World Bank Country and Lending Groups for July 2016. Available online: https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519 (accessed on day month year).

- Cancer Country Profiles. Available online: http://www.who.int/cancer/country-profiles/en/ (accessed on 7 January 2017).

- Mathers, C.D.; Fat, D.M.; Inoue, M.; Rao, C.; Lopez, A.D. Counting the dead and what they died from: An assessment of the global status of cause of death data. Bull. World Health Organ. 2005, 83, 171–177. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- “Early Detection”—The Austrian Breast-Cancer Screening Programme. Available online: http://www.wgkk.at/portal27/wgkkportal/content?contentid=10007.754989&viewmode=content (accessed on 7 January 2017).

- Oberaigner, W.; Buchberger, W.; Frede, T.; Daniaux, M.; Knapp, R.; Marth, C.; Siebert, U. Introduction of organised mammography screening in Tyrol: Results of a one-year pilot phase. BMC Public Health 2011, 11, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skovajsová, M; Májek, O.; Daneš, J.; Bartoňková, H.; Ngo, O.; Dušek, L. Results of the Czech National Breast Cancer Screening Programme. Klin. Onkol. 2014, 27 (Suppl. S2), 2S69–2S78. [Google Scholar]

- Breast Cancer Screening in Czech Republic. Available online: http://www.mamo.cz/index-en.php?pg=breast-screening--czech-republic (accessed on 7 January 2017).

- Results of Personalised Invitations of Czech Citizens to Cancer Screening Programmes. Available online: http://www.mamo.cz/index-en.php?pg=breast-screening--personalised-invitations--results (accessed on 7 January 2017).

- Screening for Breast Cancer (Mammography). Available online: https://www.cancer.dk/international/english/screening-breast-cancer-english/ (accessed on 7 January 2017).

- Christiansen, P.; Vejborg, I.; Kroman, N.; Holten, I.; Garne, J.P.; Vedsted, P.; Møller, S.; Lynge, E. Position paper: Breast cancer screening, diagnosis, and treatment in Denmark. Acta Oncol. 2014, 53, 433–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kemp Jacobsen, K.; O'Meara, E.S.; Key, D.; SM Buist, D.; Kerlikowske, K.; Vejborg, I.; Sprague, B.L.; Lynge, E.; von Euler-Chelpin, M. Comparing sensitivity and specificity of screening mammography in the United States and Denmark. Int. J. Cancer 2015, 137, 2198–2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jørgensen, K.J.; Zahl, P.H.; Gøtzsche, P.C. Breast cancer mortality in organised mammography screening in Denmark: Comparative study. BMJ 2010, 340, c1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Estonian Cancer Screening Registry. Available online: http://www.tai.ee/en/r-and-d/registers/estonian-cancer-screening-registry (accessed on 7 January 2017).

- Breast Cancer Screening. Available online: http://www.cancer.fi/syoparekisteri/en/mass-screening-registry/breast_cancer_screening/ (accessed on 7 January 2017).

- Informed Health Online. The Breast Cancer Screening Program in Germany, Cologne, Germany: Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG). 2006. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK361021/ (accessed on 7 January 2017).

- Biesheuvel, C.; Weigel, S.; Heindel, W. Mammography screening: Evidence, history and current practice in Germany and other European countries. Breast Care 2011, 6, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simou, E.; Tsimitselis, D.; Tsopanlioti, M.; Anastasakis, I.; Papatheodorou, D.; Kourlaba, G.; Gerasimos, P.; Maniadakis, N. Early evaluation of an organised mammography screening program in Greece 2004–2009. Cancer Epidemiol. 2011, 35, 375–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolozsvári, L.R.; Langmár, Z.; Rurik, I. Nationwide screening program for breast and cervical cancers in Hungary: Special challenges, outcomes, and the role of the primary care provider. Eur. J. Gynaecol. Oncol. 2013, 34, 419–424. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Boncz, I.; Sebestyén, A.; Pintér, I.; Battyány, I.; Ember, I. The effect of an organized, nationwide breast cancer screening programme on non-organized mammography activities. J. Med. Screen. 2008, 15, 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boncz, I.; Sebestyén, A.; Döbrossy, L.; Péntek, Z.; Budai, A.; Kovács, A.; Dózsa, C.; Ember, I. The organisation and results of first screening round of the Hungarian nationwide organised breast cancer screening programme. Ann. Oncol. 2007, 18, 795–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sigurdsson, K.; Olafsdóttir, E.J. Population-based service mammography screening: the Icelandic experience. Breast Cancer 2013, 5, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breast Czech Programme Report 2014–2015. Available online: http://www.breastcheck.ie/sites/default/files/bcheck/documents/breastcheck-programme-report-2014-2015.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2017).

- Israel Cancer Association. Breast Screening Program. Available online: http://www.cancer.org.il/template_e/default.aspx?PageId=7645 (accessed on 7 January 2017).

- TBST Working Group. Lo screening mammografico in italia per le donne tra I 45 e I 49 anni. Epidemiol. Prev. 2013, 37, 316–327. [Google Scholar]

- I Programmi di Screening Oncologici in Emilia-Romagna. Available online: http://www.epicentro.iss.it/passi/pdf2013/contributi_74_screen_febbraio2013.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2017).

- Cancer du Sein. Available online: http://www.sante.public.lu/fr/maladies/zone-corps/poitrine/cancer-sein-DOSSIER/index.html (accessed on 7 January 2017).

- Dépistage Actuel Cancer du Sein. Available online: https://plancancer.lu/about/depistage/cancer-du-sein/depistage-actuel-cancer-du-sein/ (accessed on 7 January 2017).

- Autier, P.; Shannoun, F.; Scharpantgen, A.; Lux, C.; Back, C.; Severi, G.; Steil, S.; Hansen-Koenig, D.A. Breast cancer screening programme operating in a liberal health care system: The Luxembourg mammography programme, 1992–1997. Int. J. Cancer 2002, 97, 828–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breast Cancer Screening Program. Available online: https://www.kreftregisteret.no/en/screening/breast-cancer-screening-programme/ (accessed on 7 January 2017).

- Weedon-Fekjær, H.; Romundstad, P.R.; Vatten, L.J. Modern mammography screening and breast cancer mortality: Population study. BMJ 2014, 348, g3701. [Google Scholar]

- Lund, E.; Mode, N.; Waaseth, M.; Thalabard, J.C. Overdiagnosis of breast cancer in the Norwegian Breast Cancer Screening Program estimated by the Norwegian Women and Cancer cohort study. BMC Cancer 2013, 13, 614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Research Based Evaluation of the Norwegian Breast Cancer Screening Program. Available online: https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/444d08daf15e48aca5321f2cefaac511/mammografirapport-til-web.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2017).

- Matkowski, R.; Szynglarewicz, B. First report of introducing population-based breast cancer screening in Poland: Experience of the 3-million population region of Lower Silesia. Cancer Epidemiol. 2011, 35, e111–e115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cancer Control Strategy for Poland 2015–2024. Available online: https://www.google.ch/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&ved=0ahUKEwiz9oadgbLTAhVNblAKHa-QALQQFggpMAA&url=https%3A%2F%2Fpto.med.pl%2Fcontent%2Fdownload%2F8007%2F87998%2Ffile%2FCancer%2520Plan%2520English%2520Version.pdf&usg=AFQjCNHeTuHAUcb1z0SD6ka3pE5yZQgbZA&cad=rja (accessed on 7 January 2017).

- Dourado, F.; Carreira, H.; Lunet, N. Mammography use for breast cancer screening in Portugal: Results from the 2005/2006 National Health Survey. Eur. J. Public Health 2013, 3, 386–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costa, A.R.; Silva, S.; Moura-Ferreira, P.; Villaverde-Cabral, M.; Santos, O.; Carmo, I.D.; Barros, H.; Lunet, N. Cancer screening in Portugal: Sex differences in prevalence, awareness of organized programmes and perception of benefits and adverse effects. Health Expect. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Programa Nacional para as Doenças Oncológicas, Relatorio 2014. Available online: https://www.dgs.pt/estatisticas-de-saude/estatisticas-de-saude/publicacoes/avaliacao-e-monitorizacao-dos-rastreios-oncologicos-organizados-de-base-populacional-de-portugal-continental-pdf.aspx (accessed on 7 January 2017).

- Breast Cancer Screening (DORA programme). Available online: http://www.dpor.si/en/?page_id=97 (accessed on 7 January 2017).

- Ascunce, N.; Salas, D.; Zubizarreta, R.; Almazán, R.; Ibáñez, J.; Ederra, M. Representatives of the Network of Spanish Cancer Screening Programmes (Red de Programas Españoles de Cribado de Cáncer); Cancer screening in Spain. Ann. Oncol. 2010, 21 (Suppl. S3), iii43–iii51. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- La Situacion del Cancer en España. Available online: http://www.msssi.gob.es/ciudadanos/enfLesiones/enfNoTransmisibles/docs/situacionCancer.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2017).

- Autier, P.; Koechlin, A.; Smans, M.; Vatten, L.; Boniol, M. Mammography screening and breast cancer mortality in Sweden. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2012, 104, 1080–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- La Prevenzione del Cancro al Seno. Available online: http://www.legacancro.ch/it/prevenzione_/varie_malattie_/cancro_del_seno_/mammografia_/ (accessed on 7 January 2017).

- Breast Cancer Screening by Mammography: International Evidence and the Situation in Switzerland. Available online: http://assets.krebsliga.ch/downloads/short_mammo_report_final_el_.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2017).

- Cancer de Mama. Available online: http://www.salut.ad/temes-de-salut/cancer-de-mama (accessed on 7 January 2017).

- Stamenić, V.; Strnad, M. Urban-rural differences in a population-based breast cancer screening program in Croatia. Croat. Med. J. 2011, 52, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Farazi, P.A. Cancer trends and risk factors in Cyprus. E Cancer Med. Sci. 2014, 8, 389. [Google Scholar]

- National Cancer Control Strategy: Cyprus. Available online: http://www.iccp-portal.org/sites/default/files/plans/Cyprus_National_Strategy_on_Cancer_English.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2017).

- Activities in Breast Cancer Screening in Cyprus. Available online: http://www.moh.gov.cy/Moh/MOH.nsf/All/E097A0A80F609321C22579C10039AB98/$file/Έκθεση%20δραστηριοτήτων%20πληθυσμιακού%20μαστογραφικού%20ελέγχου,%202003-2008%20.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2017).

- Breast Screening Programme. Available online: https://health.gov.mt/en/phc/nbs/Pages/Breast-Screening-Programme.aspx (accessed on 7 January 2017).

- The Monaco Health Screening Centre—An Exemplary Preventative Health Initiative. Available online: http://en.service-public-particuliers.gouv.mc/Social-health-and-families/Public-health/Prevention-and-screening/Screening-for-breast-cancer (accessed on 7 January 2017).

- The Monaco Health Screening Centre—An Exemplary Preventative Health Initiative. Available online: http://en.gouv.mc/Policy-Practice/Social-Affairs-and-Health/An-exemplary-Public-Health-system/Monaco-Health-Screening-Centre (accessed on 7 January 2017).

- Zakharova, N.A. Experience in the implementation of screening program for early detection of breast cancer in the Khanty-Mansi Autonomous Region-Yugra. Vopr. Onkol. 2013, 59, 382–385. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Screening Prevenzione. Available online: http://www.iss.sm/on-line/home/menudestra/screening-prevenzione.html (accessed on 7 January 2017).

- Kopeci, A.; Canaku, D.; Muja, H.; Petrela, K.; Mone, I.; Qirjako, G.; Hyska, J.; Preza, K. Breast cancer screening in Albania during 2007–2008. Mater. Sociomed. 2013, 25, 270–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breast Cancer Programs in Eurasia. Available online: http://archive.sph.harvard.edu/breastandhealth/files/tonya_soldak.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2017).

- Obralic, N.; Cuplov, M.Z.; Musanovic, M.; Softic, A.; Dizdarevic, Z.; Kurtovic, M.; Dalagija, F; Dzapo, M.; Basic, H. Organizational aspects of breast cancer screening in Sarajevo region. J. BUON 2008, 13, 553–557. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Breast and Cervical Cancer Detection Screening in Kazakhstan. Available online: http://www.womenscanceradvocacy.net/content/dam/wecan/pdf/Nadezhda%20Kobzar.Breast%20and%20Cervical%20cancer%20%20detection%20screening%20in%20Kazakhstan.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2017).

- Situation Analysis of Cancer Breast, Cervical and Prostate Cancer Screening in Macedonia. Available online: http://www.ecca.info/fileadmin/user_upload/Reports/UNFPA_Macedonia_Cancer_Control_Situation_Analysis.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2017).

- Breast Cancer Screening Programme in Montenegro. Available online: http://www.gov.me/ResourceManager/FileDownload.aspx?rId=224396&rType=2 (accessed on 7 January 2017).

- National Program for Early Detection for Breast Cancer Detection. Available online: http://www.mzdravlja.gov.me/ResourceManager/FileDownload.aspx?rid=60934&rType=2&file=Proposal%20of%20the%20NATIONAL%20PROGRAM%20FOR%20EARLY%20BREAST%20CANCER%20DETECTION.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2017).

- National Cancer Screening Program Serbia. Available online: http://www.skriningsrbija.rs/eng/breast-cancer-screening/documents/ (accessed on 7 January 2017).

- Regulation on the National Program for Early Detection of Breast Cancer. Available online: http://www.skriningsrbija.rs/files/File/English/REGULATION_ON_THE_NATIONAL_PROGRAM_FOR_EARLY_DETECTION_OF_BREAST_CANCER.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2017).

- Cancer Control in Turkey. Available online: http://kanser.gov.tr/Dosya/Sunular/Cancer.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2017).

- Capacity Assessment and Recommendations for Cancer Screening in Georgia. Available online: http://www.ecca.info/fileadmin/user_upload/Reports/UNFPA_Cancer_Screening_in_Georgia.pdf (accessed on 7 January 2017).

- Breast Cancer Awareness Events to Be Held in Kyrgyzstan. Available online: http://old.kabar.kg/eng/health/full/1837 (accessed on 7 January 2017).

- Forman, D.; Bray, F.; Brewster, D.H.; Gombe Mbalawa, C.; Kohler, B.; Piñeros, M.; Steliarova-Foucher, E.; Swaminathan, R.; Ferlay, J. Cancer Incidence in Five Continents; IARC Scientific Publication: Lyon, France, 2007; Volume X, pp. 856–857. [Google Scholar]

- De Glas, N.; de Craen, A.J.; Bastiaannet, E.; Op ’t Land, E.G.; Kiderlen, M.; van de Water, W.; Siesling, S.; Portielje, J.E.; Schuttevaer, H.M.; de Bock, G.T.; van de Velde, C.J.; Liefers, G.J. Effect of implementation of the mass breast cancer screening programme in older women in the Netherlands: population based study. BMJ 2014, 349, g5410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breast Cancer Screening Programme Implementation for Fertile Age Women in the Republic of Uzbekistan. Available online: http://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/breast-cancer-screening-programme-implementation-for-fertile-age-women-in-the-republic-of-uzbekistan#ixzz4Xl3XGm2k (accessed on 7 January 2017).

- Altobelli, E. Effect of National Income on Colorectal Cancer Screening in the WHO European Region. Ann. Epidemiol. 2017. under review. [Google Scholar]

- Forouzanfar, M.H.; Foreman, K.J.; Delossantos, A.M.; Lozano, R.; Lopez, A.D.; Murray, C.J.; Naghavi, M. Breast and cervical cancer in 187 countries between 1980 and 2010: A systematic analysis. Lancet 2011, 378, 1461–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. The Challenge Ahead: Progress and Setbacks in Breast and Cervical Cancer; IHME: Seattle, WA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Doll, R. Are we winning the fight against cancer? An epidemiological assessment: EACR—Muhlbock memorial Lecture. Eur. J. Cancer 1990, 26, 500–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim-Kos, H.E.; de Vries, E.; Soerjomataram, I.; Lemmens, V.; Siesling, S.; Coebergh, J.W. Recent trends of cancer in Europe: A combined approach of incidence, survival and mortality for 17 cancer sites since the 1990s. Eur. J. Cancer 2008, 10, 1345–1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).