1. Introduction

Epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) and its reverse process, mesenchymal–epithelial transition (MET), are fundamental biological programs that enable cells to alter their identity, respond to environmental cues and acquire new functional states. Rather than representing binary switches, these processes generate a spectrum of epithelial (E), intermediate epithelial/mesenchymal (E/M), and mesenchymal (M) phenotypes, collectively contributing to cellular plasticity. In cancer, such plasticity underpins tumor progression, invasion, metastatic dissemination, and therapy resistance, making the regulation of EMT/MET a central focus in efforts to understand the molecular drivers of metastasis and identify potential therapeutic vulnerabilities [

1,

2,

3,

4].

Among the molecular features associated with EMT-related plasticity, the CD44 adhesion receptor occupies a prominent position. The CD44 gene undergoes extensive alternative splicing to generate the standard isoform CD44s and multiple epithelial-associated variant isoforms (CD44v). A large body of evidence demonstrates that CD44 isoform usage correlates with transitions along the E/M axis: CD44s is mostly enriched in mesenchymal and invasive states, whereas CD44v isoforms are associated with epithelial and stem-like phenotypes [

5,

6,

7]. This splicing switch is governed primarily by the epithelial splicing regulators ESRP1 and ESRP2, which promote the inclusion of variant exons and thereby sustain epithelial identity. Downregulation of ESRP1/2 is a characteristic molecular feature of EMT and favors a CD44s-dominant profile linked to enhanced cellular motility [

8,

9,

10].

Multiple upstream signaling pathways converge on EMT programs, including TGF-β, Wnt, and Notch signaling. In malignant contexts, these pathways have been shown to modulate epithelial and mesenchymal gene expression programs, in part through transcriptional repression of epithelial regulators such as ESRP1 and ESRP2, thereby indirectly influencing alternative splicing patterns, including CD44 isoform selection [

11,

12]. While these regulatory relationships have been extensively characterized in cancer, it remains unclear as to what extent core splicing-based mechanisms of epithelial–mesenchymal plasticity are preserved during physiological, non-transformed cell identity transitions. Non-malignant cellular systems provide a powerful framework for dissecting the core mechanisms underlying cell-state plasticity without the confounding influence of oncogenic mutations and tumor-associated epigenetic instability. Importantly, however, such non-transformed systems have rarely been exploited to systematically map alternative splicing architectures associated with epithelial–mesenchymal identity states, particularly with respect to CD44 isoform regulation and its splicing control by ESRP proteins. In this regard, primary human fibroblasts, induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells, and iPS-derived mesenchymal stem cells (iPS-MSCs) represent three well-defined and experimentally accessible cell identities. Fibroblasts display classical mesenchymal morphology and transcriptional profiles, whereas iPS cells form compact epithelial colonies characteristic of pluripotent states. iPS-MSCs, generated from iPS cells through directed differentiation, exhibit mesenchymal features while retaining aspects of their pluripotent origin at the transcriptional level. Notably, somatic reprogramming itself is driven by a MET process that mirrors key elements of EMT/MET transitions observed during development and cancer progression [

13,

14,

15]. Together, this system provides a controlled and physiologically relevant framework for exploring molecular events associated with transitions along the E/M axis, independent of malignant transformation [

16,

17].

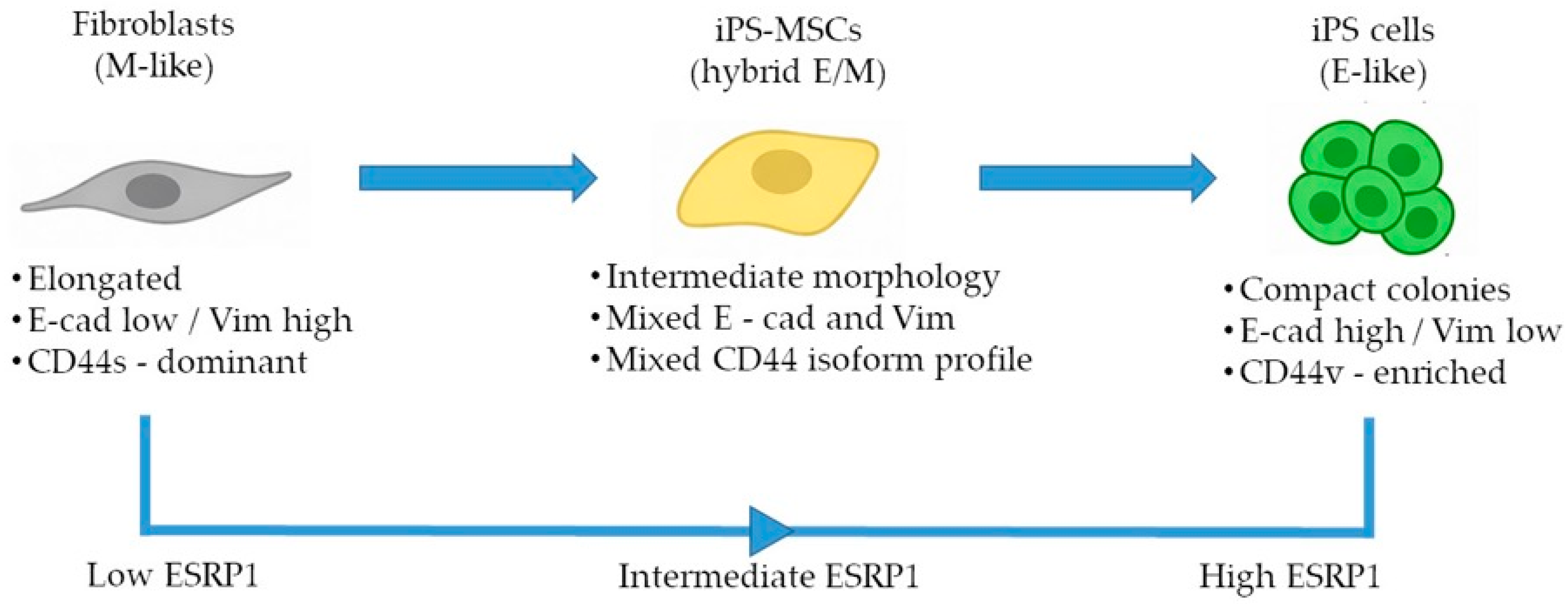

Here, we establish a non-transformed human benchmark system to investigate ESRP1-mediated CD44 alternative splicing across defined epithelial, intermediate, and mesenchymal identity states. By decoupling epithelial–mesenchymal plasticity from oncogenic transformation, this system allows for the assessment of fundamental, physiological splicing regulation associated with cell-state identity. Our aim was to determine whether these cell states recapitulate splicing-based regulatory patterns known to accompany EMT in cancer while disentangling core identity-associated mechanisms from context-dependent signaling pathways. Using an integrated analysis of CD44 alternative splicing and ESRP expression, we describe coordinated, identity-associated patterns that stratify epithelial, intermediate, and mesenchymal states along the E/M axis.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Generation of iPS Cells

Primary human neonatal dermal fibroblasts were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA; Cat. No. PCS-201-010) and cultured according to the supplier’s instructions provided by ATCC. Cells were used for reprogramming between passages 3 and 6 and routinely tested negative for mycoplasma contamination. Fibroblasts were reprogrammed into induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells using the feeder-free CytoTune™ iPS 2.0 Sendai Reprogramming Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, fibroblasts were seeded two days prior to transduction onto 6-well plates at a density of 5 × 104 cells per well in standard fibroblast culture medium. Reprogramming was initiated by transduction with Sendai viral vectors encoding the four Yamanaka factors OCT3/4, SOX2, KLF4, and c-MYC. Seven days after transduction, cells were transferred onto vitronectin-coated plates (5 µg/mL; Thermo Fisher Scientific), and the culture medium was replaced with Essential 8 (E8) medium (Life Technologies, Waltham, MA, USA, Cat No. A1517001) on the following day. Emerging iPS cell colonies were monitored for 3–4 weeks. Individual colonies were manually selected and expanded to prevent spontaneous differentiation and overconfluency. All procedures were performed in strict accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol.

2.2. Differentiation of iPS Cells into Mesenchymal Stem Cells

Mesenchymal stem cells derived from iPS cells (iPS-MSCs) were generated using the STEMdiff™ Mesenchymal Progenitor Kit (StemCell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada). Differentiation procedures were performed exactly as specified by the manufacturer, including medium changes, induction steps, and maintenance conditions, until a stable MSC-like population was obtained.

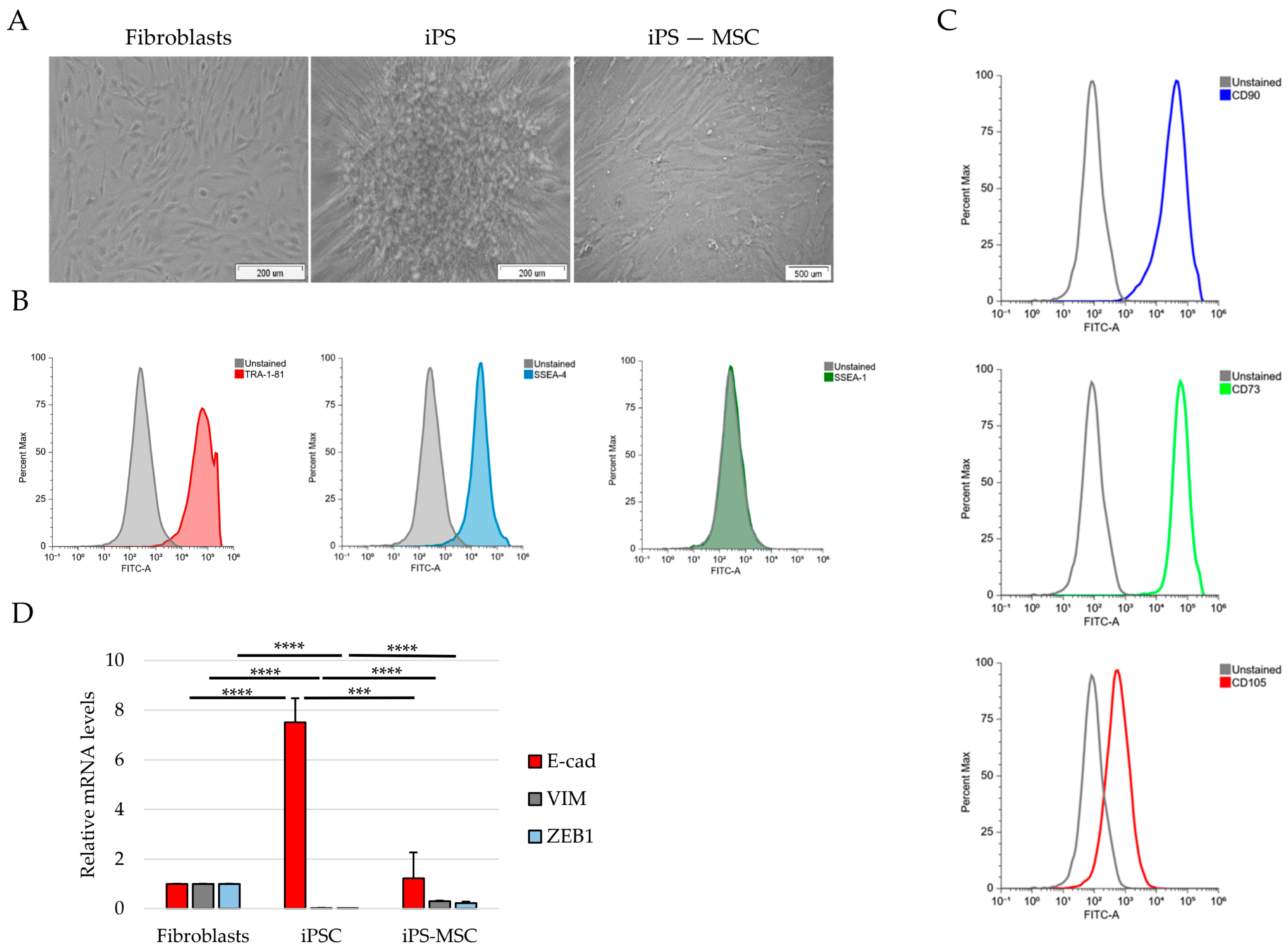

2.3. Flow Cytometry

Cells were fixed in 70% ethanol for 10 min at 37 °C and permeabilized in 90% methanol for 30 min on ice. After washing, cells were incubated with primary antibodies diluted in FACS buffer (FC001) for 30 min at room temperature, followed by incubation with fluorophore-conjugated secondary antibodies for an additional 30 min. After final washes, cells were resuspended in PBS and analyzed using a FACSAria I flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). At least 10,000 events were acquired per sample. Fluorescence signals were analyzed using unstained and isotype controls to establish gating strategies. The following antibodies were used: SSEA-1, SSEA-4 (1:200), TRA-1-60 (Alexa Fluor™ 488-conjugated, Thermo Fisher Scientific), TRA-1-81, CD73-FITC (1:20), CD90-FITC (1:5), and CD105-FITC (1:20) (STEMCELL Technologies, Cologne, Germany).

2.4. RNA Isolation and Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen, 74136, Venlo, The Netherlands) following the supplied protocol. First-strand cDNA synthesis was performed with the RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher, K1622) using 1 μg of total RNA and both oligo (dT) and random primers.

Quantitative PCR reactions were set up with Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, 4368702, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and primer pairs listed in

Supplementary Table S1. Reactions included cDNA corresponding to 7.5 ng of input RNA and 300 nM primers and were run on a LightCycler 480 system (Roche, Basel, Switzerland). Primer specificity was verified by melt curve analysis and agarose gel electrophoresis. Gene expression levels were normalized to ACTB and calculated using the Pfaffl method [

18].

2.5. siRNA Transfection

Transient gene silencing was performed using small interfering RNAs (siRNAs). Cells were seeded in 12-well plates and transfected with siRNAs targeting ESRP1 (Genomed, Warsaw, Poland; 100 pmol per well) using Oligofectamine™ Transfection Reagent (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. A non-targeting siRNA (Ambion, Foster City, CA, USA, Cat. No. 4390847) was used as a negative control. Cells were harvested 48 h post-transfection for downstream analyses. All experiments were performed using at least three independent biological replicates.

The siRNA sequence used for ESRP1 knockdown was:

5′-CACAAGCAGAGUAUUUA-3′.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

All quantitative data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) from at least three independent biological replicates. Statistical analyses were performed using Microsoft Excel. For comparisons between two groups, a two-tailed Student’s t-test was applied. For analyses involving more than two independent groups, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used where appropriate. Statistical significance thresholds were defined as * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001; **** p < 0.0001. Exact group comparisons are specified in the corresponding figure legends.

4. Discussion

In this study, we used a non-transformed cellular system composed of human foreskin fibroblasts, iPS-derived mesenchymal stem cells, and fully reprogrammed iPS cells to reconstruct a minimal and physiologically relevant epithelial–mesenchymal identity framework [

19,

20]. By integrating morphological observations, lineage marker profiling and targeted analysis of EMT-associated transcripts, we demonstrate that these three cell states reproducibly segregate into mesenchymal (fibroblasts), intermediate epithelial/mesenchymal (iPS-MSCs), and epithelial (iPS) identity states at the population level. Importantly, this distribution was reflected not only in classical EMT markers such as E-cad and VIM, but also in the architecture of CD44 isoform expression, a splicing-driven switch strongly implicated in cancer progression and metastasis [

1,

2,

3]. Taken together, our results support the use of this simplified model as a tractable platform to dissect selected identity-associated molecular features to positioning along the E/M axis, rather than dynamic EMT/MET transitions.

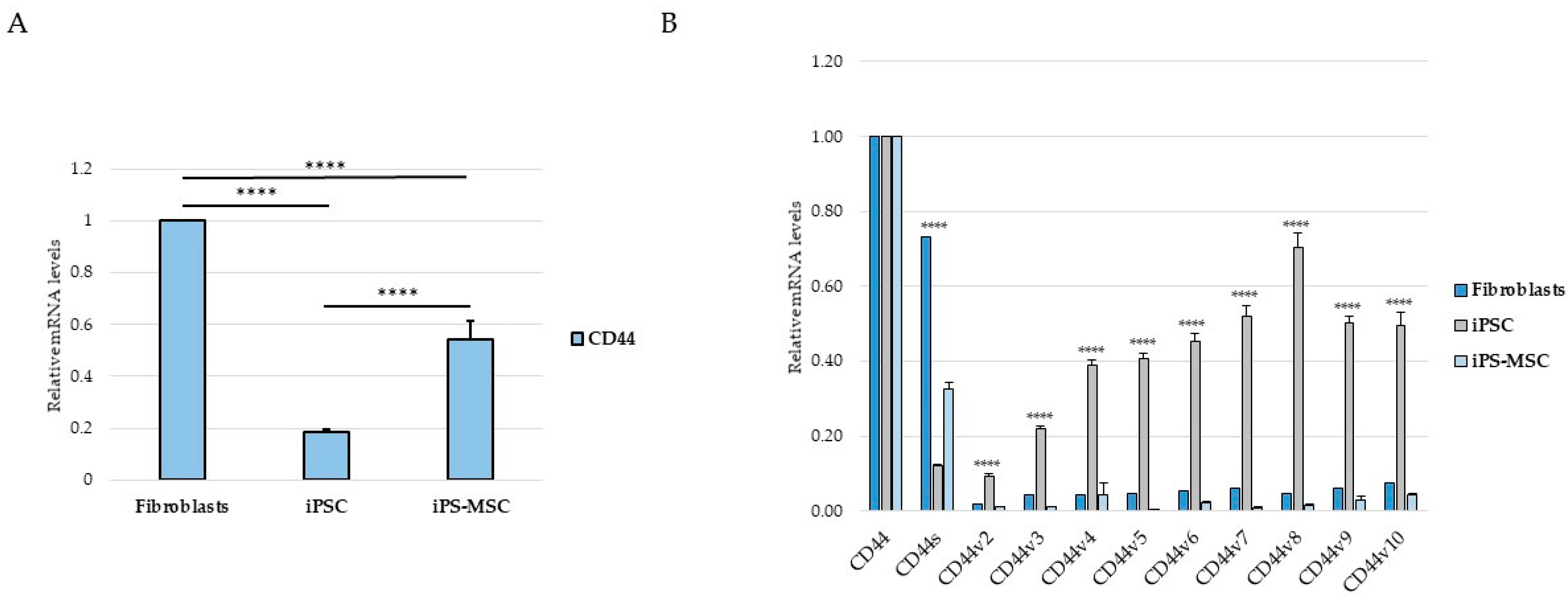

A key finding of our study is the structured pattern of CD44 isoform usage that mirrors the hierarchical organization of cellular identity states. Fibroblasts predominantly expressed the standard CD44s isoform, consistent with their mesenchymal identity, whereas iPS cells exhibited broad upregulation of numerous epithelial-associated CD44 variant exons (v2–v10). iPS-MSCs occupied an intermediate position, characterized by partial inclusion of variant exons. These observations are consistent with extensive literature demonstrating that CD44 alternative splicing is a central determinant of cellular behavior, influencing processes such as adhesion, migration, receptor availability, and stemness [

4,

5,

6,

21]. In cancers, the transition from CD44v to CD44s is a well-established molecular hallmark of EMT and has been associated with increased invasiveness, metabolic adaptation, and metastatic potential [

4,

5]. By recapitulating this isoform distribution pattern in a non-malignant cellular system, our findings suggest that CD44 splicing is closely linked to fundamental programs of cell-state identity rather than being exclusively cancer-specific.

The intermediate behavior of iPS-MSCs is particularly notable. Although they are routinely classified as mesenchymal stem cells, their transcriptional and phenotypic properties have been shown to differ from those of tissue-derived MSCs. Several studies indicate that iPS-MSCs retain remnants of epithelial identity, including residual E-cadherin expression, activity of the miR-200 family, and partial repression of key EMT-associated transcription factors [

7,

8]. Our results support this concept: iPS-MSCs displayed moderate expression of E-cadherin and Vimentin, intermediate total CD44 levels and partial inclusion of multiple CD44 variant exons, collectively positioning them within an intermediate epithelial/mesenchymal identity at the population level. Intermediate epithelial/mesenchymal states have been proposed to combine epithelial and mesenchymal traits and have been associated with collective migration and tissue repair in specific biological contexts [

3,

9]. Thus, the iPS-MSC state may represent a useful surrogate for dissecting mechanisms specific to epithelial–mesenchymal plasticity rather than to terminal differentiation.

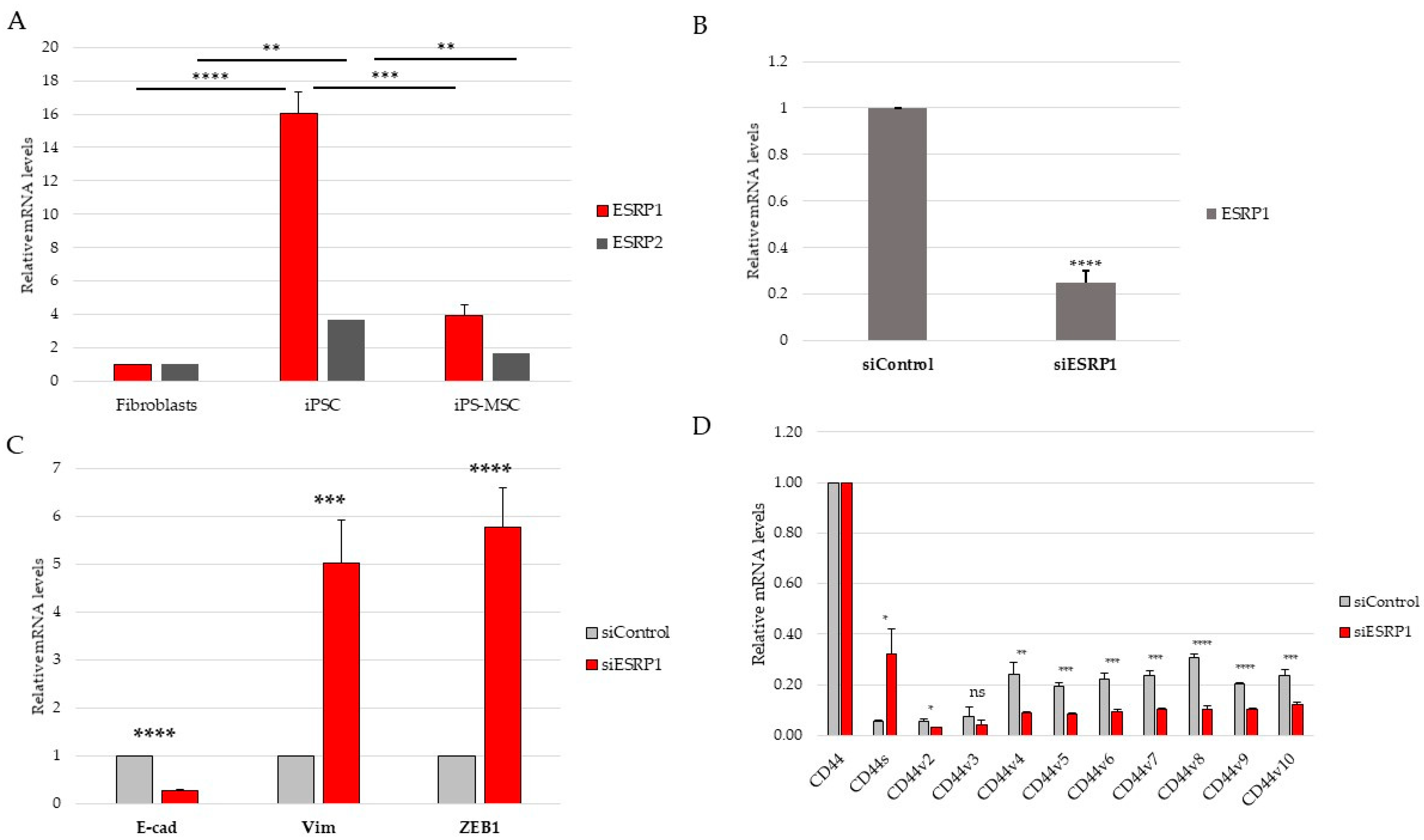

Although the present study focused primarily on CD44 alternative splicing and its regulation by ESRP1/2, the proposed model also enables the exploration of signaling pathways associated with epithelial–mesenchymal plasticity. ESRP1 and ESRP2 are well-established epithelial splicing regulators whose repression represents a hallmark of EMT, mediated by transcription factors such as TGF-β, ZEB1, and Snail [

10,

11,

22].

Although both ESRP1 and ESRP2 exhibited expression patterns consistent with epithelial identity, ESRP1 was selected for functional perturbation due to its higher expression in epithelial iPS cells and its well-established dominant role in epithelial-specific alternative splicing. While potential compensatory or partially redundant functions of ESRP2 cannot be excluded, addressing such interactions would require combinatorial perturbation approaches beyond the scope of the present study.

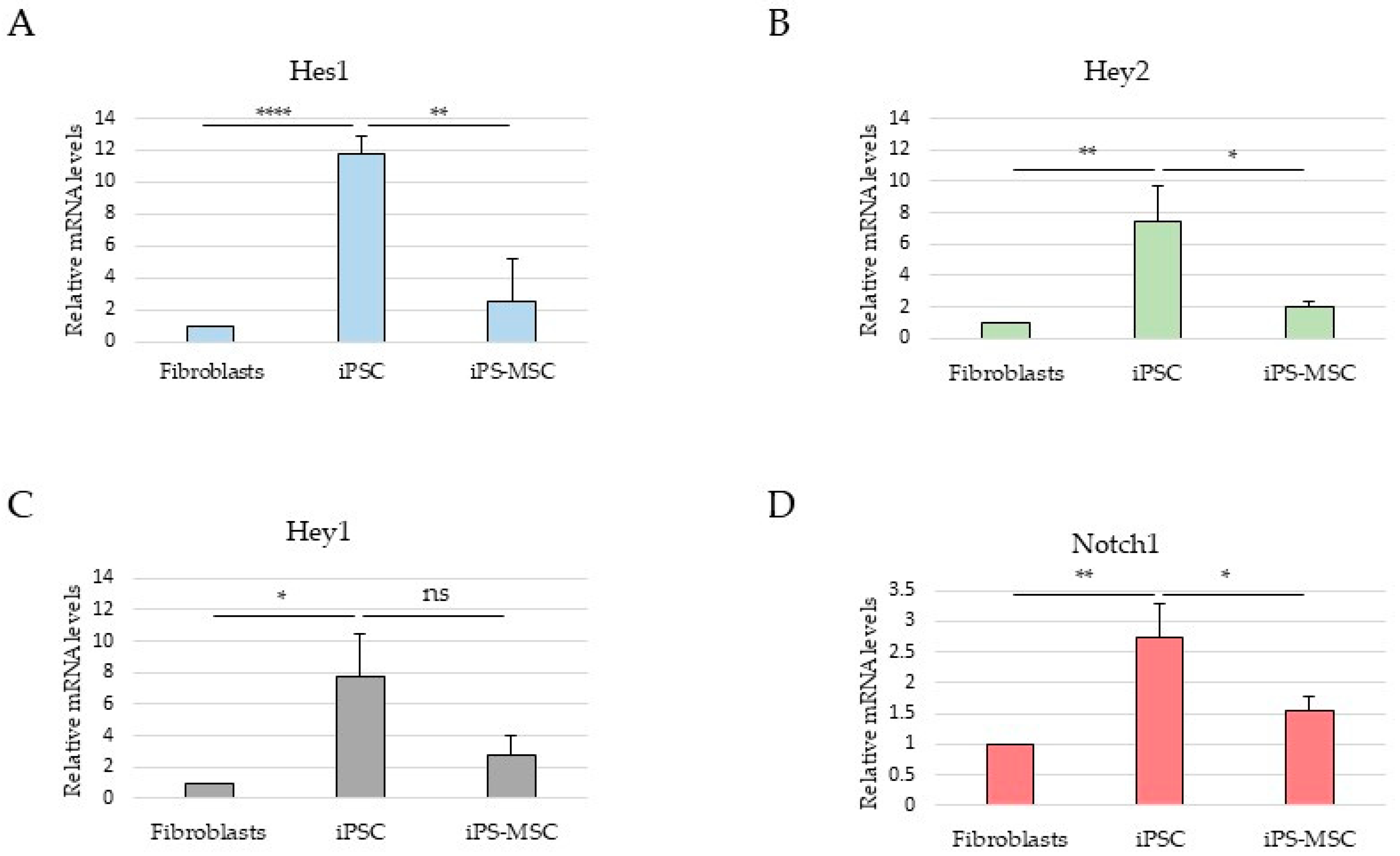

In this context, analysis of selected Notch pathway components was included to provide broader signaling background [

12,

13]. However, in this non-transformed system, Notch-related transcriptional readouts did not parallel ESRP1 expression or CD44 isoform composition and were highest in iPS cells, consistent with reported roles of Notch signaling in pluripotency maintenance rather than in promoting mesenchymal identity [

14,

23]. These observations underscore the context-dependent configuration of EMT-associated regulatory pathways during physiological cell-state transitions.

Together, these findings indicate that while ESRP1/2 expression closely aligns with CD44 isoform selection along the epithelial–mesenchymal spectrum, Notch signaling represents an independent and context-dependent regulatory layer that does not directly parallel EMT-associated splicing changes in this model. This observation highlights that regulatory axes described in cancer may adopt distinct configurations during physiological cell-state transitions. An important implication of our findings is that non-malignant systems can capture selected molecular features associated with EMT and MET programs without the confounding effects of genomic instability and heterogeneous mutational backgrounds characteristic of cancer cells [

1,

15,

24,

25]. This distinction is particularly relevant in fields where EMT is often incorrectly equated with malignancy, rather than being recognized as a normal and highly regulated developmental and regenerative process. Importantly, epithelial–mesenchymal plasticity is not restricted to cancer but represents a fundamental biological process operating during embryonic development, tissue regeneration, wound healing, and fibrotic remodeling [

1,

15]. In these physiological contexts, transient or partial EMT-like programs enable cells to acquire migratory and adaptive properties without permanent loss of epithelial identity [

1,

2]. CD44 and its alternative splicing have been implicated in several non-malignant settings, including stem cell maintenance, tissue repair, and fibroblast activation, suggesting that regulation of CD44 isoform usage represents a general mechanism of cell-state plasticity rather than a cancer-specific phenomenon [

5,

6,

7]. In light of this, the non-transformed system used here should be viewed primarily as a model of physiological epithelial–mesenchymal identity regulation, with relevance to cancer-associated EMT arising from shared underlying molecular programs rather than direct tumor-specific behavior [

1,

2].

This study also highlights several strengths of the proposed model. It is experimentally accessible, highly reproducible, and does not rely on genetic engineering. The defined identity states were robust and well-characterized at the morphological, phenotypic, and transcriptional levels. Moreover, because iPS cells are generated from fibroblasts and iPS-MSCs are subsequently derived from iPS cells, the system provides experimentally accessible mesenchymal, intermediate epithelial/mesenchymal, and epithelial identity states generated through defined reprogramming and differentiation procedures. This feature more closely mirrors identity changes observed during reprogramming, regeneration, and development than conventional immortalized cell lines [

8,

9]. In contrast to inducible cancer EMT–MET models based on transient growth factor stimulation (e.g., TGF-β exposure and withdrawal), the present system does not model dynamic EMT–MET transitions. Instead, it provides stable and experimentally accessible epithelial, intermediate, and mesenchymal identity states, enabling the analysis of identity-associated molecular programs independent of acute signaling perturbations.

Nevertheless, some limitations should be acknowledged. First, although the three examined cell populations clearly differ in their epithelial–mesenchymal (E/M) status, they represent discrete identity states rather than a continuous phenotypic landscape. Future studies employing single-cell transcriptomics approaches or time-resolved analyses during differentiation could provide a more refined view of intermediate identity states and transition dynamics. Second, CD44 alternative splicing is regulated by numerous signaling pathways beyond ESRP1/2 and Notch—including Wnt, FGFR2, Rbfox2, and hypoxia-associated pathways, which were not explored in the current experimental setting [

10,

16,

26]. Dissecting the interplay between these regulatory axes will be important for a more comprehensive understanding of splicing-based epithelial–mesenchymal plasticity. Finally, functional assays such as migration, adhesion, or spheroid formation would further strengthen the causal link between molecular identity states and associated cellular behaviors. An additional limitation is the absence of protein-level validation of ESRP1 knockdown. Although ESRP1 silencing at the transcript level was efficient and consistently associated with altered CD44 splicing patterns, direct assessment of ESRP1 protein levels (e.g., by Western blotting) would be required to fully substantiate the extent of knockdown at the protein level. This analysis was beyond the scope of the present study and will be addressed in future work.