Protective Effects of Bauhinia forficata on Bone Biomechanics in a Type 2 Diabetes Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

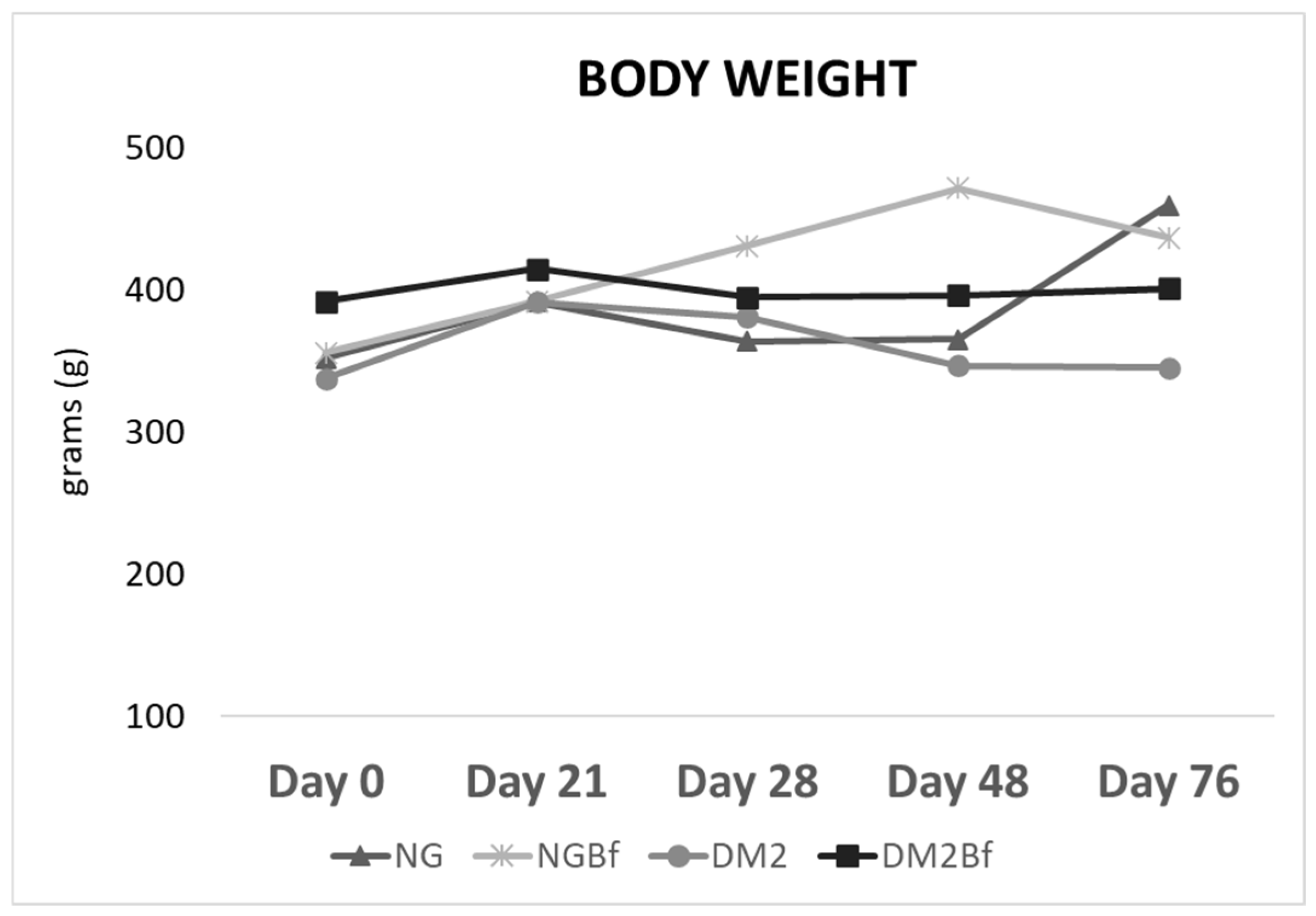

2.1. Body Weight

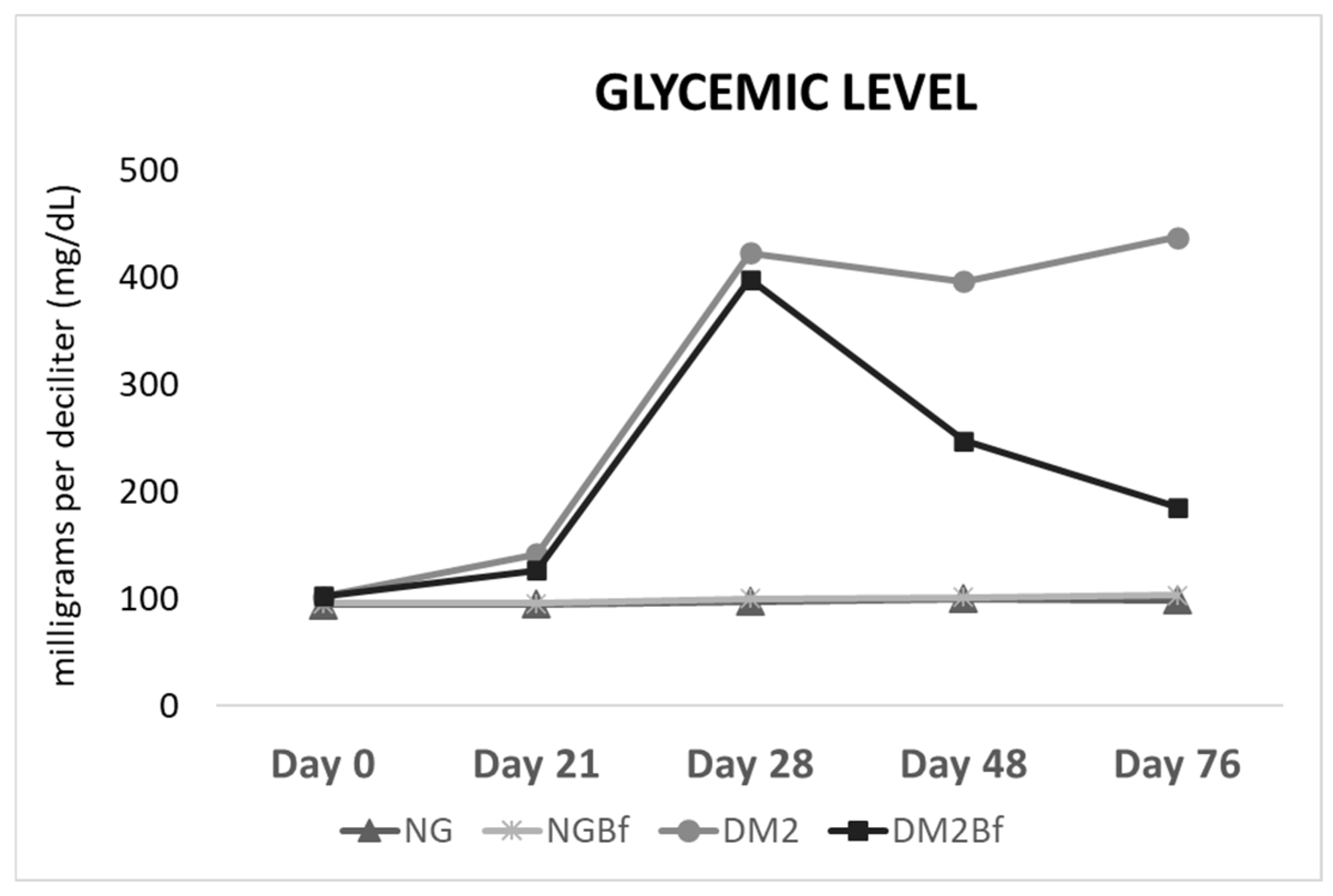

2.2. Glycemic Level

2.3. Long Bone Biomechanical Analyses

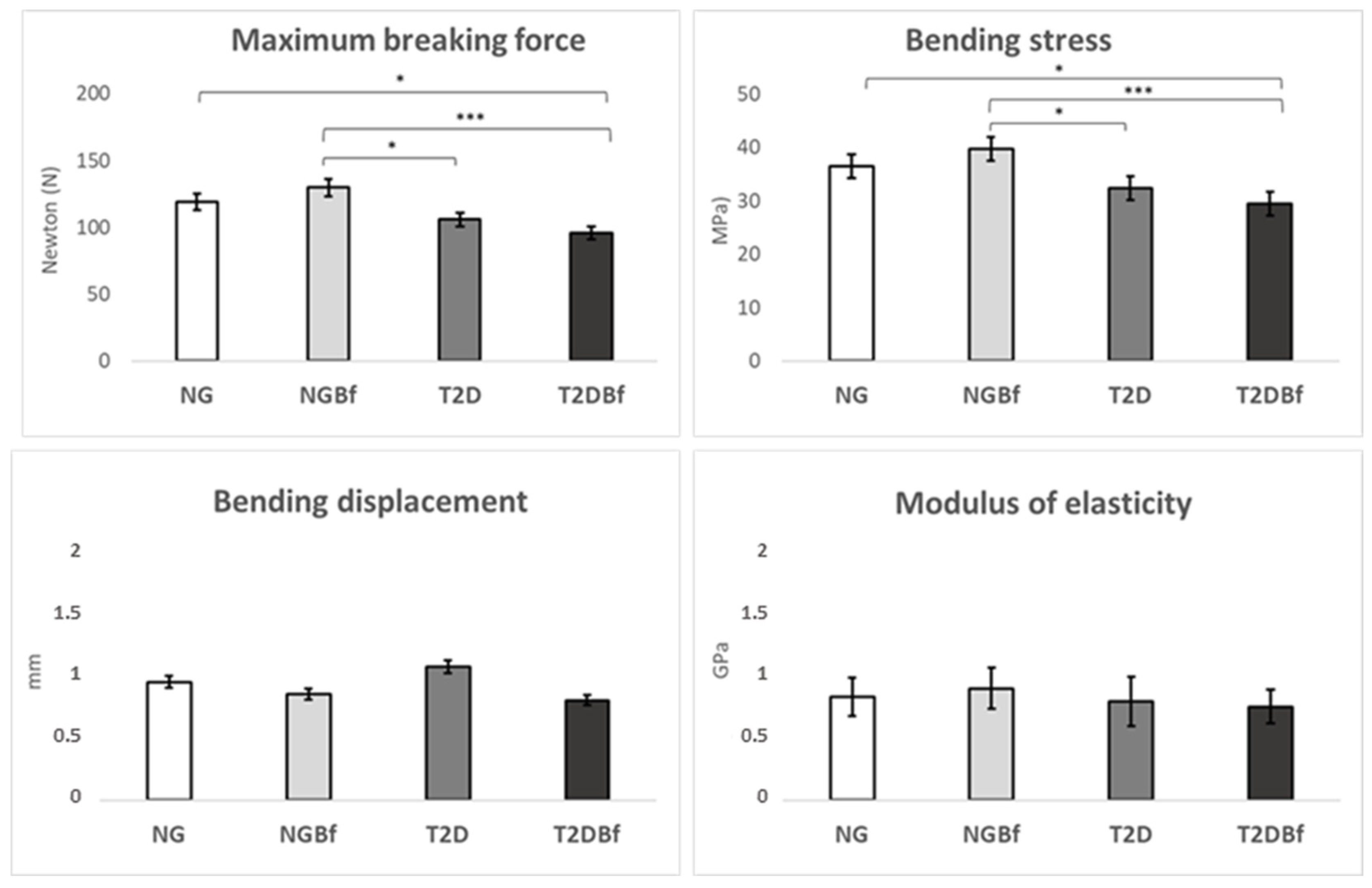

2.3.1. Three-Point Bending Test

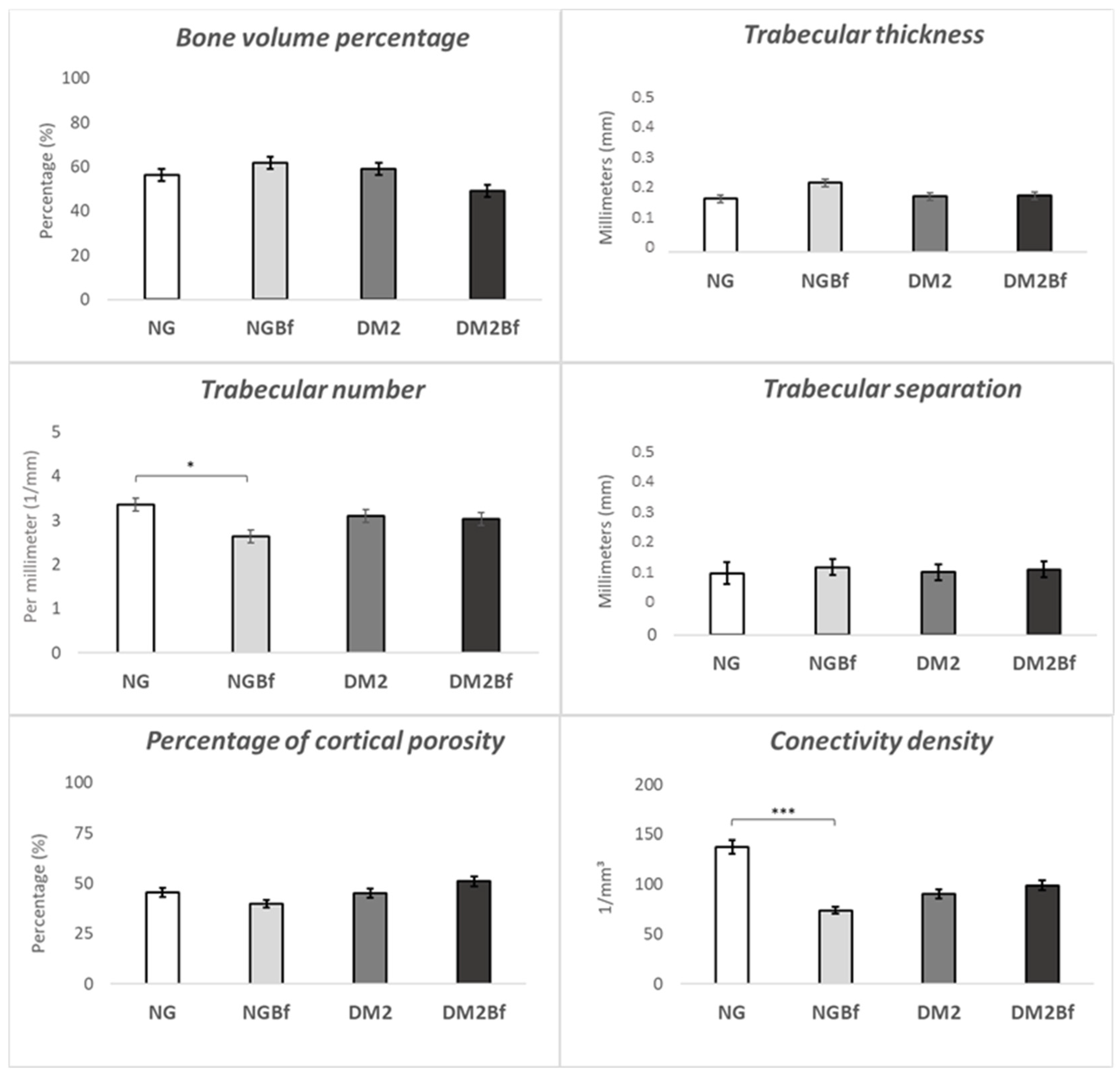

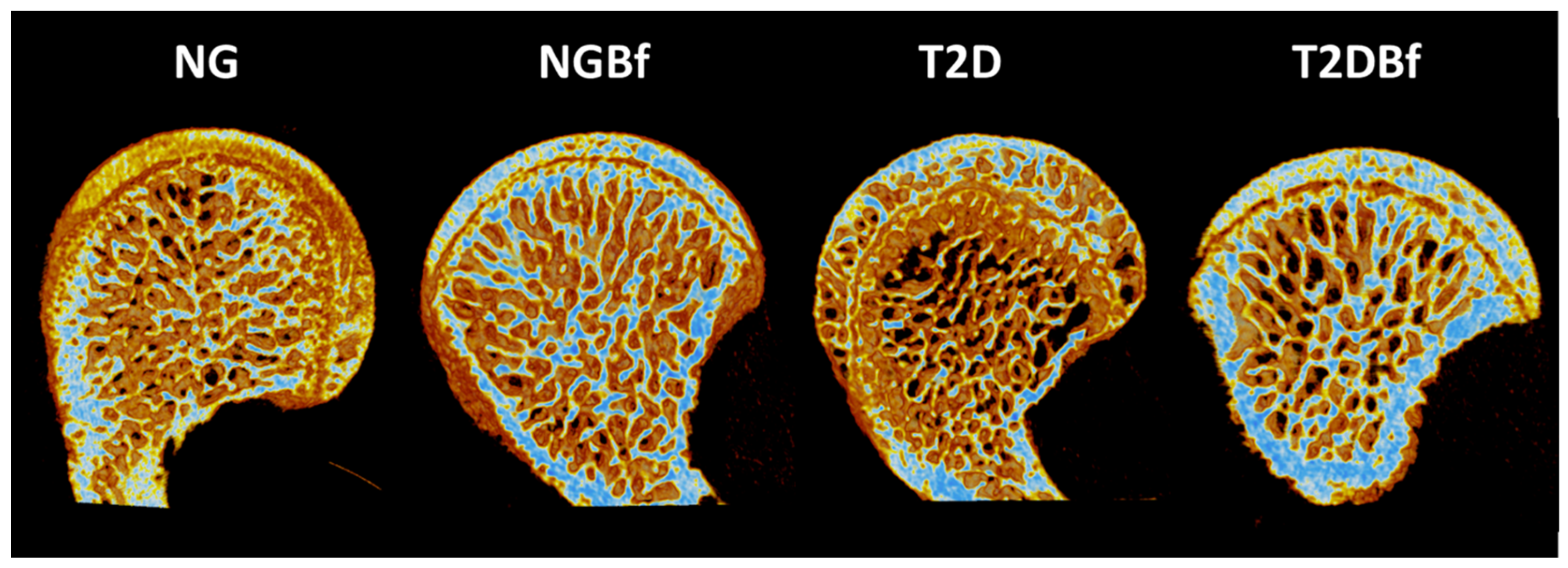

2.3.2. Microtomography (MicroCT—Femurs)

2.4. Peri-Implantar Analyses

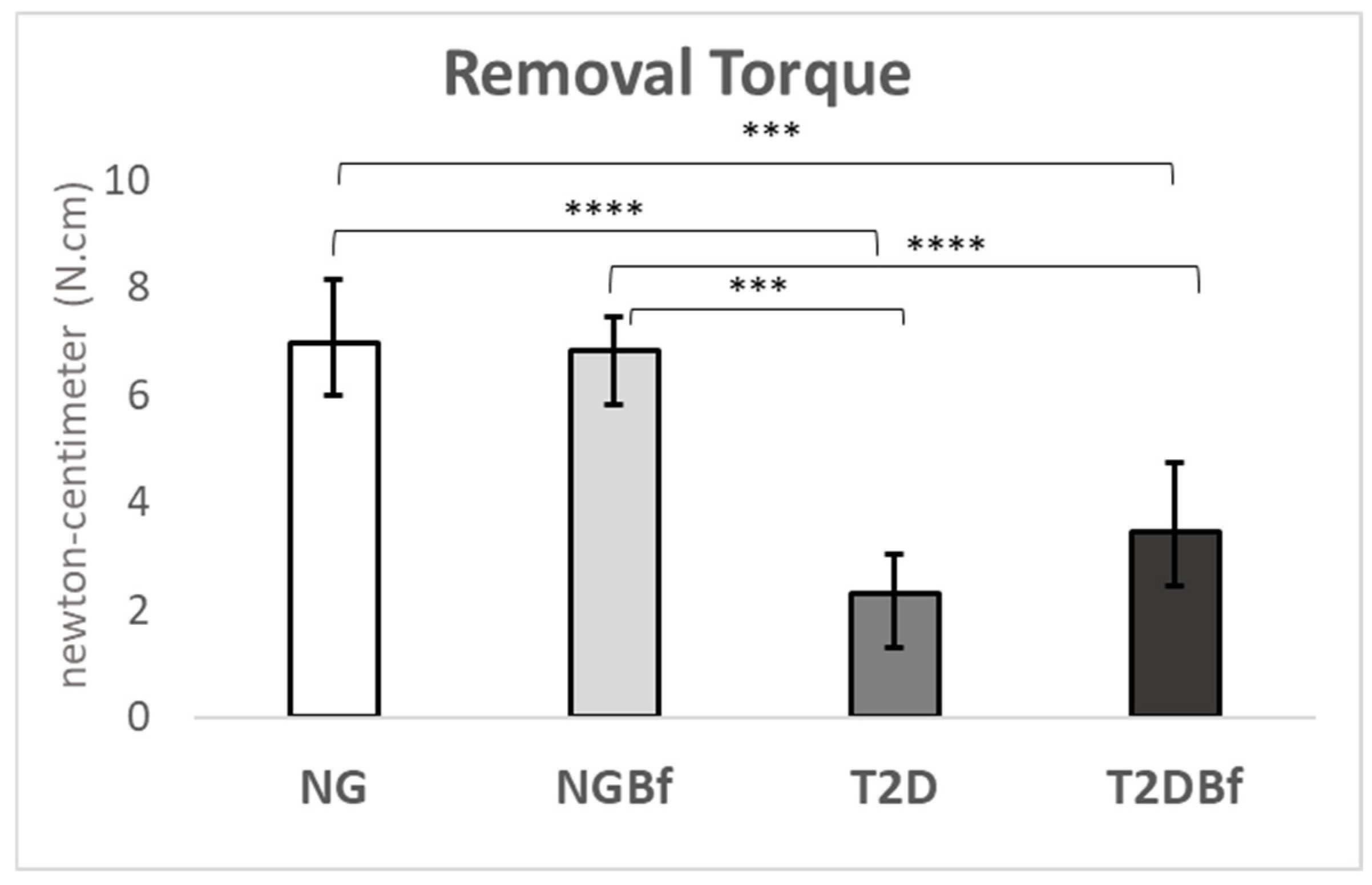

2.4.1. Biomechanical Analyses (Removal Torque—N·cm)

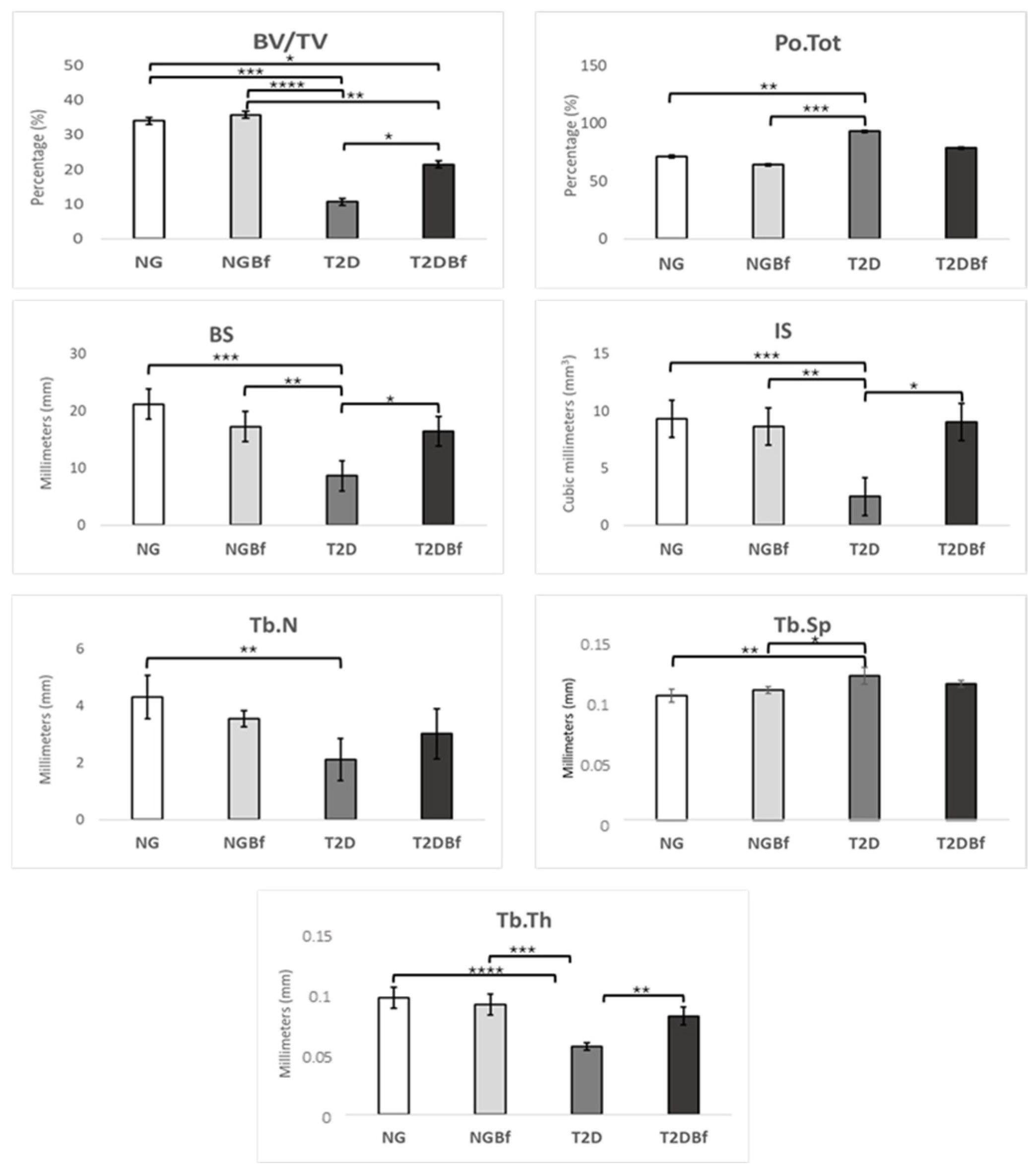

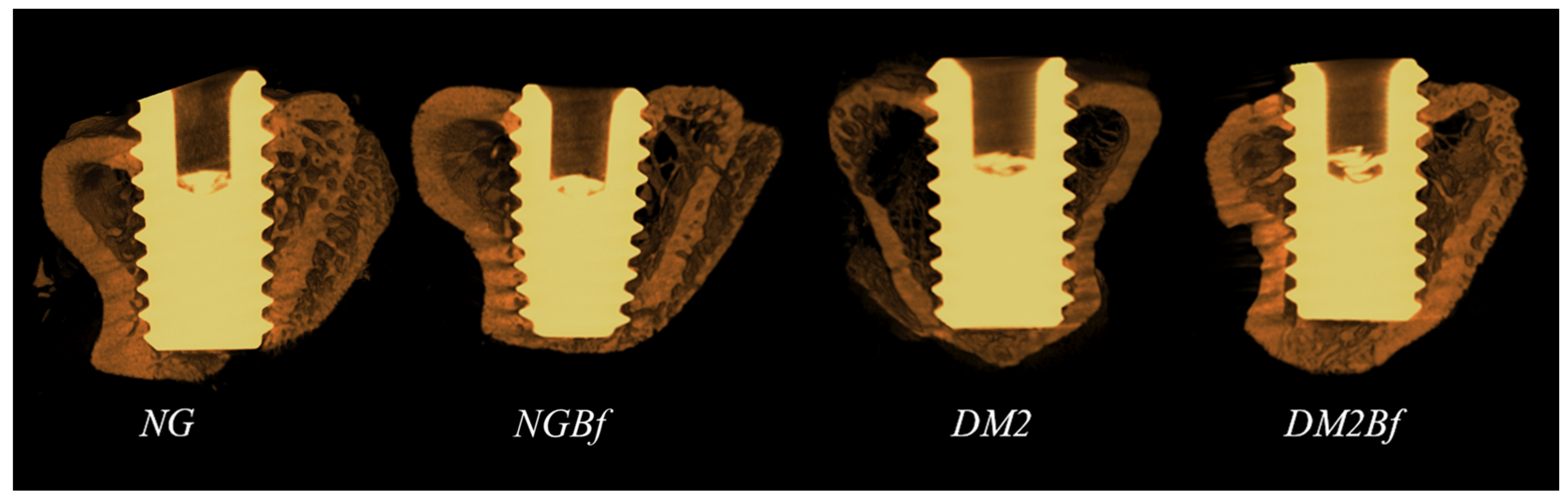

2.4.2. Microtomography (MicroCT—Titanium Implants)

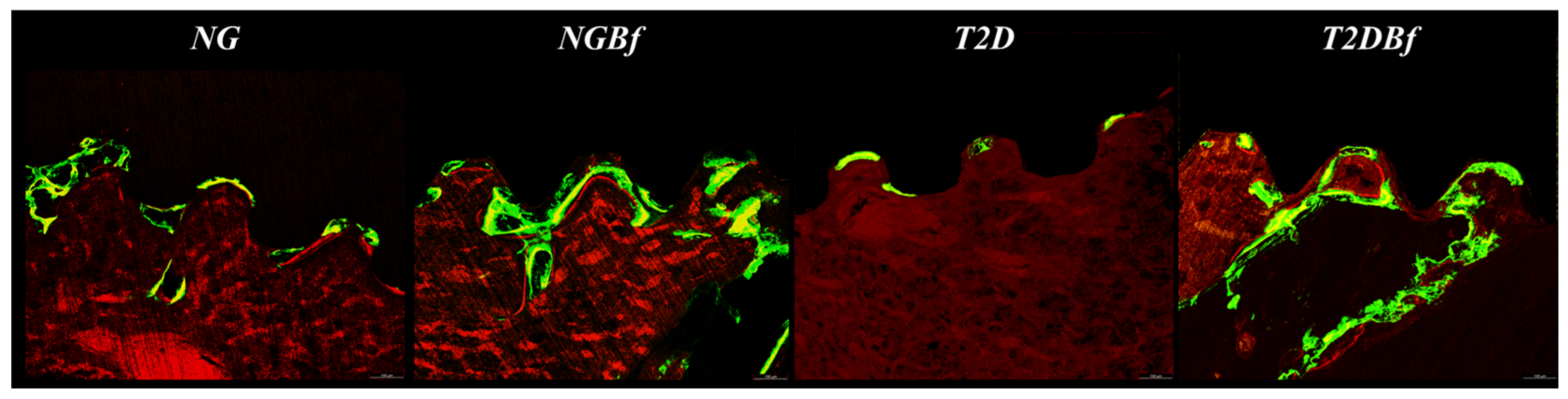

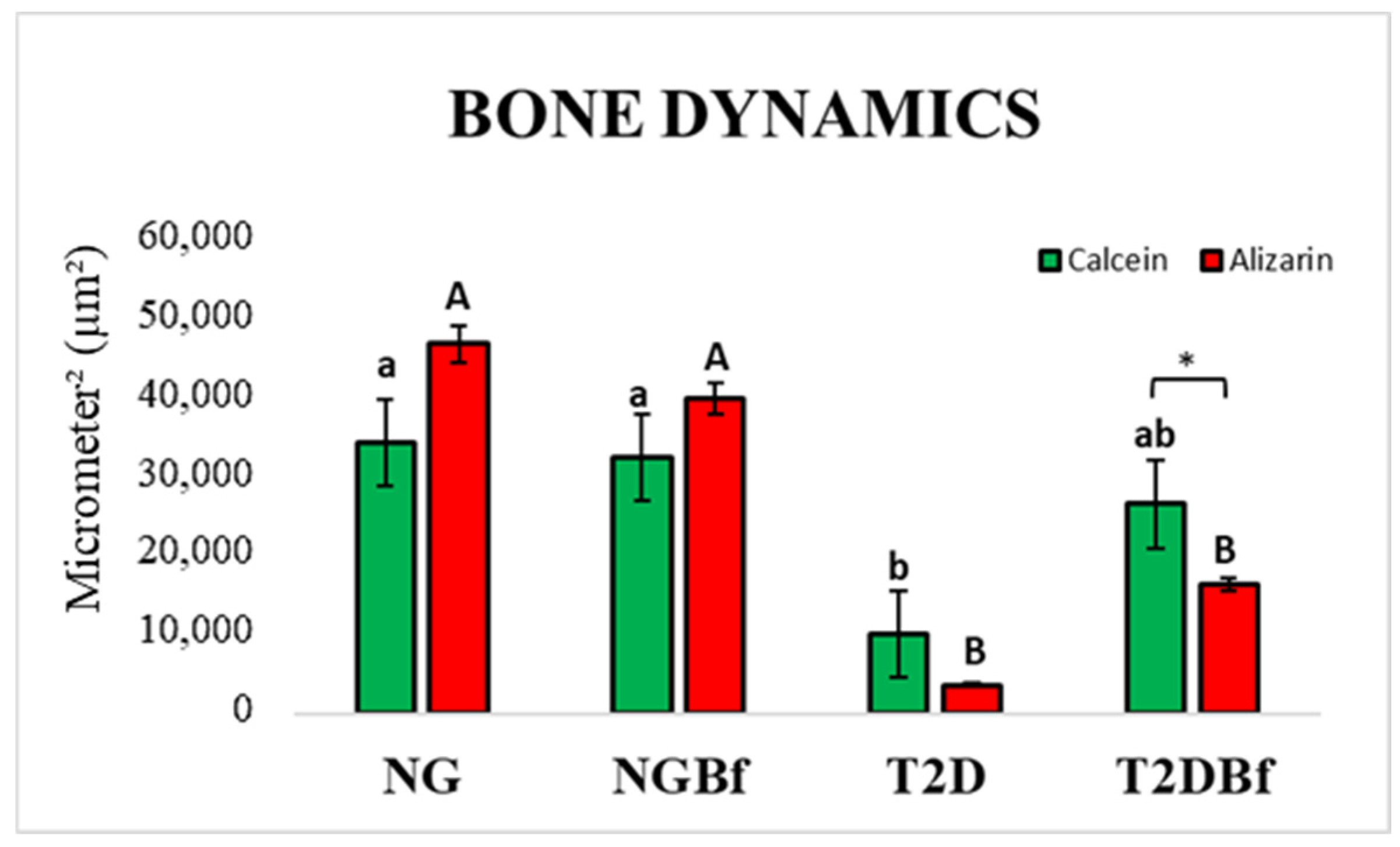

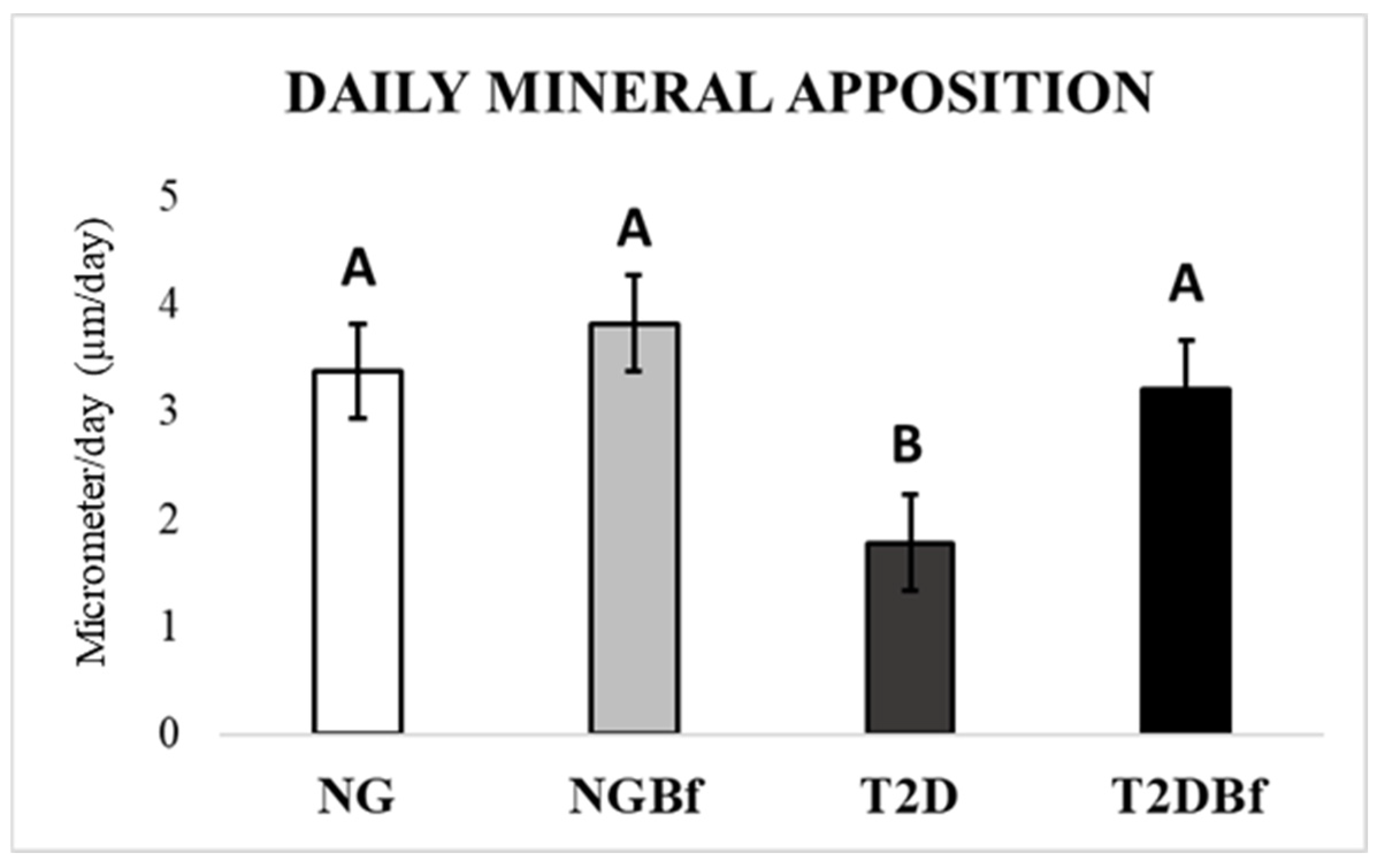

2.4.3. Confocal Laser Microscopy Analysis

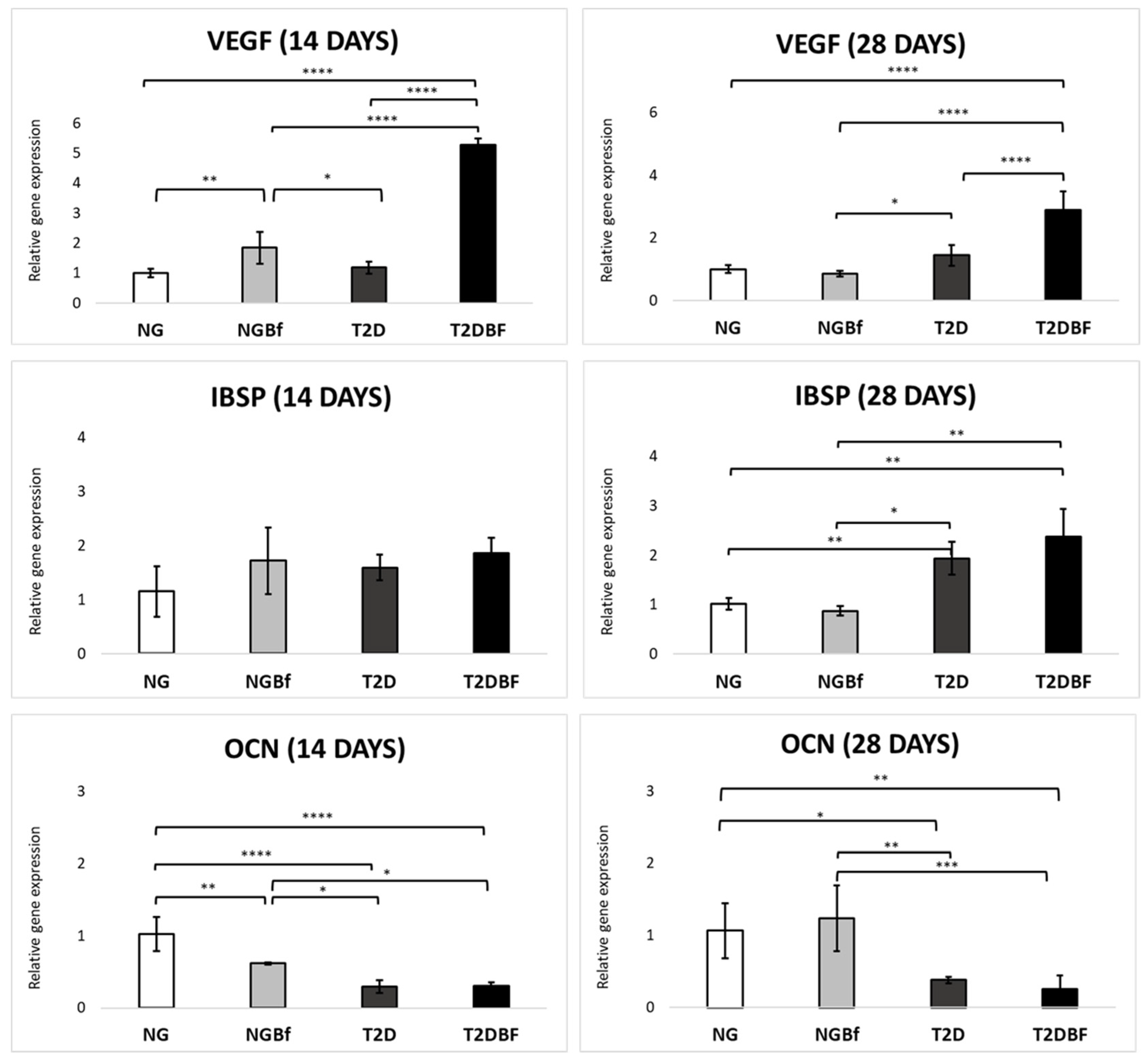

2.4.4. Molecular Analysis (RT-qPCR)

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals

4.2. Type 2 Diabetes Induction

4.3. Bauhinia forficata Link Tea

Bauhinia forficata Link Tea Chemical Profile

4.4. Implant Installation

4.5. Euthanasia and Proposed Analyses (Sample Processing)

4.5.1. Three-Point Bending Testing (EMIC)

4.5.2. Microtomography (MicroCT)

4.5.3. Peri-Implant Biomechanic (Removal Torque)

4.5.4. Confocal Laser Microscopy

4.5.5. Molecular Analysis (RT-qPCR)

4.5.6. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AGEs | Advanced glycation end-products |

| Bf | Bauhinia forficata Link |

| IBSP | Bone Sialoprotein |

| NF-kB | Nuclear factor Kappa-B |

| NG | Normoglycemic |

| NGBf | Normoglycemic treated with Bauhinia forficata |

| OCN | Osteocalcin |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| STZ | Streptozotocin |

| SUS | Brazilian Unified Health System |

| T2D | Type 2 diabetes |

| T2DBf | Type 2 diabetes treated with Bauhinia forficata |

| VEGF | Vascular endothelial growth factor |

References

- International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 7th ed.; International Diabetes Federation: Brussels, Belgium, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- American Diabetes Association Professional Practice Committee. Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes: Standards of Care in Diabetes—2024. Diabetes Care 2024, 47, 20–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siam, N.H.; Snigdha, N.N.; Tabasumma, N.; Parvin, I. Diabetes Mellitus and Cardiovascular Disease: Exploring Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, and Treatment Strategies. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2024, 25, 436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hua, Y.; Bi, R.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, L.; Guo, J.; Li, Y. Different Bone Sites-Specific Response to Diabetes Rat Models: Bone Density, Histology and Microarchitecture. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0205503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epstein, S.; Defeudis, G.; Manfrini, S.; Napoli, N.; Pozzilli, P.; Scientific Committee of the First International Symposium on Diabetes and Bone. Diabetes and Disordered Bone Metabolism (Diabetic Osteodystrophy): Time for Recognition. Osteoporos. Int. 2016, 27, 1931–1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahen, V.A.; Gerbaix, M.; Koeppenkastrop, S.; Lim, S.F.; McFarlane, K.E.; Nguyen, A.N.L.; Peng, X.Y.; Weiss, N.B.; Brennan-Speranza, T.C. Multifactorial Effects of Hyperglycaemia, Hyperinsulinemia and Inflammation on Bone Remodelling in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2020, 55, 109–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dede, A.D.; Tournis, S.; Dontas, I.; Trovas, G. Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus and Fracture Risk. Metabolism 2014, 63, 1480–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Karsenty, G. An Overview of the Metabolic Functions of Osteocalcin. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep. 2015, 13, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudio, A.; Privitera, F.; Pulvirenti, I.; Canzonieri, E.; Rapisarda, R.; Fiore, C.E. The Relationship between Inhibitors of the Wnt Signalling Pathway (Sclerostin and Dickkopf-1) and Carotid Intima-Media Thickness in Postmenopausal Women with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Vasc. Dis. Res. 2014, 11, 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitol-Palin, L.; de Souza Batista, F.R.; Gomes-Ferreira, P.H.S.; Mulinari-Santos, G.; Ervolino, E.; Souza, F.Á.; Matsushita, D.H.; Okamoto, R. Different Stages of Alveolar Bone Repair Process Are Compromised in the Type 2 Diabetes Condition: An Experimental Study in Rats. Biology 2020, 9, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, P.G.F.P.; Bonfante, E.A.; Bergamo, E.T.P.; de Souza, S.L.S.; Riella, L.; Torroni, A.; Benalcazar Jalkh, E.B.; Witek, L.; Lopez, C.D.; Zambuzzi, W.F.; et al. Obesity/Metabolic Syndrome and Diabetes Mellitus on Peri-Implantitis. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 31, 596–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bajaj, S.; Prasad, S.; Gupta, A.; Singh, V.B. Oral Manifestations in Type-2 Diabetes and Related Complications. Indian J. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012, 16, 777–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meier, C.; Schwartz, A.V.; Egger, A.; Lecka-Czernik, B. Effects of Diabetes Drugs on the Skeleton. Bone 2016, 82, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Souza, B.V.C.; Moreira Araújo, R.S.D.R.; Silva, O.A.; Faustino, L.C.; Gonçalves, M.F.B.; dos Santos, M.L.; Souza, G.R.; Rocha, L.M.; Cardoso, M.L.S.; Nunes, L.C.C. Bauhinia forficata in the Treatment of Diabetes Mellitus: A Patent Review. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2018, 28, 129–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedrete, T.A.; Hauser-Davis, R.A.; Moreira, J.C. Proteomic Characterization of Medicinal Plants Used in the Treatment of Diabetes. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 140, 294–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinafo, M.S.; Benedetti, P.R.; Gaiotte, L.B.; Costa, F.G.; Schoffen, J.P.F.; Fernandes, G.S.A.; Chuffa, L.G.A.; Seiva, F.R.F. Effects of Bauhinia forficata on Glycaemia, Lipid Profile, Hepatic Glycogen Content and Oxidative Stress in Rats Exposed to Bisphenol A. Toxicol. Rep. 2019, 6, 244–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepato, M.T.; Baviera, A.M.; Vendramini, R.C.; Brunetti, I.L. Evaluation of Toxicity after One-Month’s Treatment with Bauhinia forficata Decoction in Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Rats. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2004, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Düsman, E.; de Almeida, I.V.; Coelho, A.C.; Balbi, T.J.; Düsman Tonin, L.T.; Vicentini, V.E. Antimutagenic Effect of Medicinal Plants Achillea millefolium and Bauhinia forficata In Vivo. Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2013, 2013, 893050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pepato, M.T.; Keller, E.H.; Baviera, A.M.; Kettelhut, I.C.; Vendramini, R.C.; Brunetti, I.L. Anti-Diabetic Activity of Bauhinia forficata Decoction in Streptozotocin-Diabetic Rats. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2002, 81, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubkowski, J.; Durbin, S.V.; Silva, M.C.; Farnsworth, D.; Gildersleeve, J.C.; Oliva, M.L.; Wlodawer, A. Structural Analysis and Unique Molecular Recognition Properties of a Bauhinia forficata Lectin That Inhibits Cancer Cell Growth. FEBS J. 2017, 284, 429–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgueiro, A.C.; Folmer, V.; da Silva, M.P.; Mendez, A.S.; Zemolin, A.P.; Posser, T.; Franco, J.L.; Puntel, R.L.; Puntel, G.O. Effects of Bauhinia forficata Tea on Oxidative Stress and Liver Damage in Diabetic Mice. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2016, 2016, 8902954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Cunha, A.M.; Menon, S.; Menon, R.; Couto, A.G.; Bürger, C.; Biavatti, M.W. Hypoglycemic activity of dried extracts of Bauhinia forficata Link. Phytomedicine 2010, 17, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lino, C.d.e.S.; Diógenes, J.P.; Pereira, B.A.; Faria, R.A.; Andrade Neto, M.; Alves, R.S.; de Queiroz, M.G.; de Sousa, F.C.; Viana, G.S. Antidiabetic activity of Bauhinia forficata extracts in alloxan-diabetic rats. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2004, 27, 125–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Souza, P.; da Silva, L.M.; Boeing, T.; Somensi, L.B.; Cechinel-Zanchett, C.C.; Campos, A.; Krueger, C.M.A.; Bastos, J.K.; Cechinel-Filho, V.; Andrade, S.F. Influence of Prostanoids in the Diuretic and Natriuretic Effects of Extracts and Kaempferitrin from Bauhinia forficata Link Leaves in Rats. Phytother. Res. 2017, 31, 1521–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franco, R.R.; Mota Alves, V.H.; Ribeiro Zabisky, L.F.; Justino, A.B.; Martins, M.M.; Saraiva, A.L.; Goulart, L.R.; Espindola, F.S. Antidiabetic potential of Bauhinia forficata Link leaves: A non-cytotoxic source of lipase and glycoside hydrolases inhibitors and molecules with antioxidante and antiglycation properties. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2020, 123, 109798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Periferakis, A.; Periferakis, K.; Badarau, I.A.; Petran, E.M.; Popa, D.C.; Caruntu, A.; Costache, R.S.; Scheau, C.; Caruntu, C.; Costache, D.O. Kaempferol: Antimicrobial Properties, Sources, Clinical, and Traditional Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 15054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Castro, T.A.; Hassumi, J.S.; Julião, G.M.; Dutra, M.C.; da Silva, A.C.E.; Monteiro, N.G.; de Souza Batista, F.R.; Mulinari-Santos, G.; Lisboa-Filho, P.N.; Okamoto, R. Optimization of Peri-Implant Bone Repair in Estrogen-Deficient Rats on a Cafeteria Diet: The Combined Effects of Systemic Risedronate and Genistein-Functionalized Implants. Materials 2025, 18, 662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, F.; Liu, F.; Yu, S.; Zhang, G.; Li, J.; Sun, X. Protective Effect of Curcumin on Bone Trauma in a Rat Model via Expansion of Myeloid Derived Suppressor Cells. Med. Sci. Monit. Int. Med. J. Exp. Clin. Res. 2020, 26, e924724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semeghini, M.S.; Scalize, P.H.; Coelho, M.C.; Fernandes, R.R.; Pitol, D.L.; Tavares, M.S.; de Sousa, L.G.; Coppi, A.A.; Siessere, S.; Bombonato-Prado, K.F. Lycopene prevents bone loss in ovariectomized rats and increases the number of osteocytes and osteoblasts. J. Anat. 2022, 241, 729–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceverino, G.C.; Sanchez, P.K.V.; Fernandes, R.R.; Alves, G.A.; de Santis, J.B.; Tavares, M.S.; Siéssere, S.; Bombonato-Prado, K.F. Preadministration of yerba mate (Ilex paraguariensis) helps functional activity and morphology maintenance of MC3T3-E1 osteoblastic cells after in vitro exposition to hydrogen peroxide. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2021, 48, 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Diabetes: Key Facts; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/diabetes (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Richards, S.E.; Wijeweera, C.; Wijeweera, A. Lifestyle and socioeconomic determinants of diabetes: Evidence from country-level data. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0270476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Alves-Costa, S.; Nascimento, G.G.; de Souza, B.F.; Hugo, F.N.; Leite, F.R.M.; Ribeiro, C.C.C. Global, regional, and national burden of high sugar-sweetened beverages consumption, 1990–2021, with projections up to 2050: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2025, 122, 1413–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wajima, C.S.; Pitol-Palin, L.; de Souza Batista, F.R.; Dos Santos, P.H.; Matsushita, D.H.; Okamoto, R. Morphological and biomechanical characterization of long bones and peri-implant bone repair in type 2 diabetic rats treated with resveratrol. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 2860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, X.Q.; Han, T.; Zhang, X.; Wu, J.Z.; Rahman, K.; Qin, L.P.; Zheng, C.J. Kaempferitrin prevents bone lost in ovariectomized rats. Phytomed. Int. J. Phytother. Phytopharm. 2015, 22, 1159–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peres-Ueno, M.J.; Stringhetta-Garcia, C.T.; Castoldi, R.C.; Ozaki, G.A.T.; Chaves-Neto, A.H.; Dornelles, R.C.M.; Louzada, M.J.Q. Model of hindlimb unloading in adult female rats: Characterizing bone physicochemical, microstructural, and biomechanical properties. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0189121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boskey, A.L. Bone composition: Relationship to bone fragility and antiosteoporotic drug effects. BoneKEy Rep. 2013, 2, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonseca, H.; Moreira-Goncalves, D.; Coriolano, H.J.; Duarte, J.A. Bone quality: The determinants of bone strength and fragility. Sports Med. 2014, 44, 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Olsen, B.R. Distinct VEGF functions during bone development and homeostasis. Arch. Immunol. Ther. Exp. 2014, 62, 363–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrara, N. Vascular endothelial growth factor: Basic science and clinical progress. Endocr. Rev. 2004, 25, 581–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, C.; Wang, J.; Liu, Y.; Yu, Q.; Liu, Y.; Deng, N.; Liu, J. Functional Selenium Nanoparticles Enhanced Stem Cell Osteoblastic Differentiation through BMP Signaling Pathways. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2014, 24, 6872–6883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempster, D.W.; Compston, J.E.; Drezner, M.K.; Glorieux, F.H.; Kanis, J.A.; Malluche, H.; Meunier, P.J.; Ott, S.M.; Recker, R.R.; Parfitt, A.M. Standardized nomenclature, symbols, and units for bone histomorphometry: A 2012 update of the report of the ASBMR Histomorphometry Nomenclature Committee. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2013, 28, 2–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosla, S. Minireview: The OPG/RANKL/RANK system. Endocrinology 2001, 142, 5050–5055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, S.; Klineberg, I.; Levinger, I.; Brennan-Speranza, T.C. The effect of hyperglycaemia on osseointegration: A review of animal models of diabetes mellitus and titanium implant placement. Arch. Osteoporos. 2016, 11, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sachelarie, L.; Scrobota, I.; Cioara, F.; Ghitea, T.C.; Stefanescu, C.L.; Todor, L.; Potra Cicalau, G.I. The Influence of Osteoporosis and Diabetes on Dental Implant Stability: A Pilot Study. Medicina 2025, 61, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sampaio, P.M.; Recacho, B.J.; Fender, M.L.; Freitas, L.H.M.; Monteiro, C.R. Effects of Bauhinia forficata Link tea in the glycemic profile of diabetic patients: A literature review. Rev. Fitos 2022, 16, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verônica Cardoso de Souza, B.; de Morais Sousa, M.; Augusto Gasparotto Sattler, J.; Cristina Sousa Gramoza Vilarinho Santana, A.; Bruno Fonseca de Carvalho, R.; de Sousa Lima Neto, J.; de Matos Borges, F.; Angelica Neri Numa, I.; Braga Ribeiro, A.; César Cunha Nunes, L. Nanoencapsulation and bioaccessibility of polyphenols of aqueous extracts from Bauhinia forficata link. Food Chem. Mol. Sci. 2022, 5, 100144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, E.P.; de Freitas, B.P.; Kunigami, C.N.; Moreira, D.L.; de Figueiredo, N.G.; Ribeiro, L.O.; Moreira, R.F.A. Bauhinia forficata Link Infusions: Chemical and Bioactivity of Volatile and Non-Volatile Fractions. Molecules 2022, 27, 5415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreres, F.; Gil-Izquierdo, A.; Vinholes, J.; Silva, S.T.; Valentão, P.; Andrade, P.B. Bauhinia forficata Link authenticity using flavonoids profile: Relation with their biological properties. Food Chem. 2012, 134, 894–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gudavalli, D.; Pandey, K.; Ede, V.G.; Sable, D.; Ghagare, A.S.; Kate, A.S. Phytochemistry and pharmacological activities of five species of Bauhinia genus: A review. Fitoterapia 2024, 174, 105830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Percie du Sert, N.; Hurst, V.; Ahluwalia, A.; Alam, S.; Avey, M.T.; Baker, M.; Browne, W.J.; Clark, A.; Cuthill, I.C.; Dirnagl, U.; et al. The ARRIVE Guidelines 2.0: Updated Guidelines for Reporting Animal Research. PLoS Biol. 2020, 18, e3000410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carillon, J.; Romain, C.; Bardy, G.; Fouret, G.; Feillet-Coudray, C.; Gaillet, S.; Lacan, D.; Cristol, J.P.; Rouanet, J.M. Cafeteria diet induces obesity and insulin resistance associated with oxidative stress but not with inflammation: Improvement by dietary supplementation with a melon superoxide dismutase. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2013, 65, 254–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Smith, M.; Karthikeyan, S.; Jeffers, M.S.; Janik, R.; Thomason, L.A.; Stefanovic, B.; Corbett, D. A physiological characterization of the cafeteria diet model of metabolic syndrome in the rat. Physiol. Behav. 2016, 167, 382–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ervolino da Silva, A.C.; de Souza Batista, F.R.; Hassumi, J.S.; Pitol Palin, L.; Monteiro, N.G.; Frigério, P.B.; Okamoto, R. Improvement of Peri-Implant Repair in Estrogen-Deficient Rats Fed a Cafeteria Diet and Treated with Risedronate Sodium. Biology 2022, 11, 578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ervolino, E.; Statkievicz, C.; Toro, L.F.; de Mello-Neto, J.M.; Cavazana, T.P.; Issa, J.P.M.; Dornelles, R.C.M.; de Almeida, J.M.; Nagata, M.J.H.; Okamoto, R.; et al. Antimicrobial photodynamic therapy improves the alveolar repair process and prevents the occurrence of osteonecrosis of the jaws after tooth extraction in senile rats treated with zoledronate. Bone 2018, 120, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palin, L.P.; Polo, T.O.B.; Batista, F.R.S.; Gomes-Ferreira, P.H.S.; Garcia Junior, I.R.; Rossi, A.C.; Freire, A.; Faverani, L.P.; Sumida, D.H.; Okamoto, R. Daily melatonin administration improves osseointegration in pinealectomized rats. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2018, 26, e20170470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Molon, R.S.; Morais-Camilo, J.A.; Verzola, M.H.; Faeda, R.S.; Pepato, M.T.; Marcantonio, E., Jr. Impact of diabetes mellitus and metabolic control on bone healing around osseointegrated implants: Removal torque and histomorphometric analysis in rats. Clin. Oral Implant Res. 2013, 24, 831–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouxsein, M.L.; Boyd, S.K.; Christiansen, B.A.; Guldberg, R.E.; Jepsen, K.J.; Müller, R. Guidelines for Assessment of Bone Microstructure in Rodents Using Micro–Computed Tomography. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2010, 25, 1468–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitol-Palin, L.; Sousa, I.C.; de Araújo, J.C.R.; de Souza Batista, F.R.; Inoue, B.K.N.; Botacin, P.R.; de Vasconcellos, L.M.R.; Lisboa-Filho, P.N.; Okamoto, R. Vitamin D3-Coated Surfaces and Their Role in Bone Repair and Peri-Implant Biomechanics. Biology 2025, 14, 476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassumi, J.S.; Mulinari-Santos, G.; Fabris, A.L.D.S.; Jacob, R.G.M.; Gonçalves, A.; Rossi, A.C.; Freire, A.R.; Faverani, L.P.; Okamoto, R. Alveolar bone healing in rats: Micro-CT, immunohistochemical and molecular analysis. J. Appl. Oral Sci. 2018, 26, e20170326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, B.K.N.; Paludetto, L.V.; Monteiro, N.G.; Batista, F.R.d.S.; Kitagawa, I.L.; da Silva, R.S.; Antoniali, C.; Lisboa Filho, P.N.; Okamoto, R. Synergic Action of Systemic Risedronate and Local Rutherpy in Peri-implantar Repair of Ovariectomized Rats: Biomechanical and Molecular Analysis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Day 0 | Day 21 | Day 28 | Day 42 | Day 70 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NG | 352.1 ± 31.05 a | 391.6 ± 137.3 ab | 364 ± 25 a | 365.5 ± 36.86 a | 459.5 ± 19 b |

| NGBf | 355.8 ± 28.09 a | 391.9 ± 137.3 a | 430.9 ± 29.46 a | 471.7 ± 29.45 b | 436.7 ± 139.3 a |

| T2D | 337.9 ± 17.67 a | 391.7 ± 38.57 a | 381.1 ± 29.35 a | 346.7 ± 35.55 a | 345.5 ± 36.18 a |

| T2DBf | 391.8 ± 42.99 a | 414.9 ± 44.41 a | 395.1 ± 30.26 a | 396.5 ± 72.12 a | 401.1 ± 93.09 a |

| Day 0 | Day 21 | Day 28 | Day 42 | Day 70 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NG | 94.25 ± 7.375 a | 94.75 ± 5.817 a | 97.17 ± 6.887 a | 99.33 ± 4.141 a | 98.33 ± 6.25 a |

| NGBf | 95.22 ± 7.092 a | 95.28 ± 5.592 a | 99.44 ± 5.853 a | 100.8 ± 6.119 a | 102.5 ± 4.905 b |

| T2D | 101.6 ± 4.997 a | 141.7 ± 22.04 b | 422.3 ± 48.48 ab | 395.9 ± 55.67 ab | 437 ± 6.33 ab |

| T2DBf | 102.1 ± 7.605 a | 126.2 ± 14.83 ac | 397.5 ± 75.79 b | 246.8 ± 113.3 cd | 185.1 ± 120.1 c |

| Comparison | p Value † | |

|---|---|---|

| Calcein | NG vs. DM2 | 0.0120 |

| NGBf vs. DM2 | 0.0257 | |

| Alizarin Red | NG vs. DM2 | <0.0001 |

| NG vs. DM2Bf | 0.0004 | |

| NGBf vs. DM2 | <0.0001 | |

| NGBf vs. DM2Bf | 0.0090 |

| Bauhinia forficata (5 g) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Amount | Percentage (%) | |

| kcal | 0 kcal | 0 |

| Carbohydrates | 0 g | 0 |

| Proteins | 0 g | 0 |

| Total Fat | 0 g | 0 |

| Saturated Fat | 0 g | 0 |

| Trans Fat | 0 g | (*) |

| Dietary Fiber | 0 g | 0 |

| Sodium | 0 g | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sousa, I.C.; Pitol-Palin, L.; Batista, F.R.d.S.; de Oliveira Filho, O.N.; Frasnelli, S.C.T.; de Souza Batista, V.E.; Matsushita, D.H.; Okamoto, R. Protective Effects of Bauhinia forficata on Bone Biomechanics in a Type 2 Diabetes Model. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 1724. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18111724

Sousa IC, Pitol-Palin L, Batista FRdS, de Oliveira Filho ON, Frasnelli SCT, de Souza Batista VE, Matsushita DH, Okamoto R. Protective Effects of Bauhinia forficata on Bone Biomechanics in a Type 2 Diabetes Model. Pharmaceuticals. 2025; 18(11):1724. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18111724

Chicago/Turabian StyleSousa, Isadora Castaldi, Letícia Pitol-Palin, Fábio Roberto de Souza Batista, Odir Nunes de Oliveira Filho, Sabrina Cruz Tfaile Frasnelli, Victor Eduardo de Souza Batista, Dóris Hissako Matsushita, and Roberta Okamoto. 2025. "Protective Effects of Bauhinia forficata on Bone Biomechanics in a Type 2 Diabetes Model" Pharmaceuticals 18, no. 11: 1724. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18111724

APA StyleSousa, I. C., Pitol-Palin, L., Batista, F. R. d. S., de Oliveira Filho, O. N., Frasnelli, S. C. T., de Souza Batista, V. E., Matsushita, D. H., & Okamoto, R. (2025). Protective Effects of Bauhinia forficata on Bone Biomechanics in a Type 2 Diabetes Model. Pharmaceuticals, 18(11), 1724. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph18111724