Abstract

The global increase in the population of Visually Impaired People (VIPs) underscores the rapidly growing demand for a robust navigation system to provide safe navigation in diverse environments. State-of-the-art VIP navigation systems cannot achieve the required performance (accuracy, integrity, availability, and integrity) because of insufficient positioning capabilities and unreliable investigations of transition areas and complex environments (indoor, outdoor, and urban). The primary reason for these challenges lies in the segregation of Visual Impairment (VI) research within medical and engineering disciplines, impeding technology developers’ access to comprehensive user requirements. To bridge this gap, this paper conducts a comprehensive review covering global classifications of VI, international and regional standards for VIP navigation, fundamental VIP requirements, experimentation on VIP behavior, an evaluation of state-of-the-art positioning systems for VIP navigation and wayfinding, and ways to overcome difficulties during exceptional times such as COVID-19. This review identifies current research gaps, offering insights into areas requiring advancements. Future work and recommendations are presented to enhance VIP mobility, enable daily activities, and promote societal integration. This paper addresses the urgent need for high-performance navigation systems for the growing population of VIPs, highlighting the limitations of current technologies in complex environments. Through a comprehensive review of VI classifications, VIPs’ navigation standards, user requirements, and positioning systems, this paper identifies research gaps and offers recommendations to improve VIP mobility and societal integration.

1. Introduction

Approximately 2.2 billion people around the world have near or distant vision impairment [1]. Visual Impairment (VI) reduces quality of life and lowers workforce participation and productivity. The World Health Organization estimates an annual global productivity loss of US$411 billion due to VI [1].

Currently, the most widely used aids for Visually Impaired People (VIPs) are white canes and guide dogs. However, these two aids are unable to provide safe and accurate navigation as neither can identify complex street signs or scenarios. Consequently, a significant challenge remains for VIPs to navigate independently. Considerable efforts are therefore being made to find a solution to VIPs’ navigation and wayfinding, initially focusing on Positioning, Navigation, and Timing (PNT) sensors.

Such efforts in seeking to develop high-performance mobility aids, however, suffer from the existing limitations of sensors. For example, while the main PNT sensor, Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS), can deliver PNT information for users worldwide, with meter positioning accuracy using pseudo-range measurements and centimeter positioning accuracy using carrier phase measurements in real-time, it is unavailable both indoors and in urban environments where GNSS signals can be reflected, obstructed, and attenuated. This leads to potential errors and outages in the provision of PNT information for navigation. Alternatives to GNSS, such as dead reckoning, indoor positioning, and computer vision, can address these limitations. However, challenges in their implementation encompass issues such as inaccurate stereo cameras, reduced visual sensor performance in low-light conditions, and the significant size of Lidar sensors, among others.

An initial hurdle that must be surmounted in developing a high-performance positioning system for navigation and wayfinding for VIPs is the segregation of visually impaired research between medical and engineering disciplines. As an initial suggestion, promoting interdisciplinary collaboration among experts from diverse fields can enhance navigation solutions for VIPs.

To bridge this gap comprehensively, Section 2 of this paper delineates the global definitions of VI to provide a greater understanding of its spectrum. Section 3 outlines the principal international and regional standards of navigation for VIPs. Section 4 explores VIP mobility requirements across environmental, system, and user aspects. A notable research gap emerges concerning the understanding of VIP mobility requirements, particularly the lack of behavioral data in individual and crowd scenarios. To address this deficiency, a series of experiments are conducted at the Pedestrian Accessibility Movement Environment Laboratory (PAMELA), and the findings, which can serve as a foundation for future research endeavors, are highlighted in Section 5. These insights play a pivotal role in enhancing and extending environmental features and indoor navigation systems.

Section 6 scrutinizes existing positioning and navigation systems designed for VIPs and identifies seven limitations in current navigation aids for VIPs, encompassing positioning accuracy, gaps in transition areas, user comfort, motivation, multi-mode feedback, complex object detection, and social concerns such as scalability, cost-effectiveness, and privacy leakage. Notably, a quantitative analysis of these limitations is lacking, underscoring a critical research gap. Section 7 discusses the impact of pandemics, such as COVID-19, on the daily lives of VIPs. It highlights the relevant technologies developed to help overcome the challenges associated with navigation during such times.

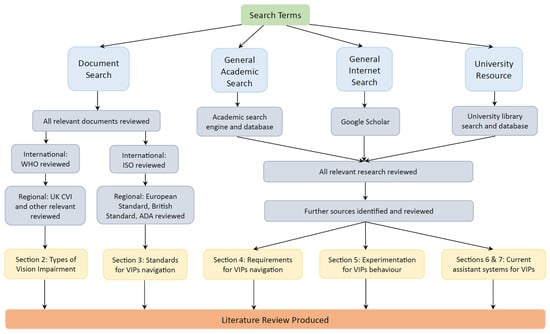

The inclusion criteria include literature studies related to visual impairment classification, navigation systems, mobility aids, AI assistants, and the impact of COVID-19 on VIPs. Studies involving outdated technologies or lacking validation are excluded. A systematic search, employing terms such as “visually impaired” and “wayfinding,” spans academic and public databases, with efforts to minimize bias through multiple reviewers and thorough exploration of the literature. Figure 1 presents the methodological framework for the comprehensive literature review. The key methods of this review are outlined below:

Figure 1.

Methodological framework for the comprehensive literature review.

- Review Justification: Section 1 delves into the navigation challenges faced by Visually Impaired People (VIPs);

- Precise Review Objective: This aims to develop a high-performance positioning system for VIPs, addressing the segregation of visually impaired research between medical and engineering disciplines;

- Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria: The included literature covers topics such as ‘classification of visual impairment’, ‘standards of navigation systems for visually impaired people’, ‘navigation assistants for visually impaired people’, ‘mobility aids for visually impaired people’, ‘positioning and wayfinding of navigation systems’, ‘artificial intelligence assistants for visually impaired people’, and ‘impact of COVID-19 on visually impaired people’. The excluded literature consists of outdated technological interventions and studies lacking validation;

- Explicit Literature Search: Key search terms include ‘visually impaired’, ‘mobility aids’, ‘navigation’, ‘positioning’, and ‘wayfinding’. This review encompasses publicly available documents, academic journals, conference papers, reports, and university theses from general academic engines, public scholar databases, and the university’s internal database up to the beginning of 2024;

- Efforts to Reduce Selection Bias and Identify All the Relevant Literature: Multiple reviewers assess the literature for reliability. A systematic search of the ‘grey literature’ is conducted using internet search engines;

- Quality Ranking of the Reviewed Literature: The literature with higher international impact and research significance is given higher importance;

- Suitability of Included Studies: Tables summarize the studies, providing information on authors, system performance, main system components, advantages, and disadvantages;

- Results and Interpretations: Findings are discussed at the end of each section, comparing them to other published works and related topics;

- Review Limitations: Limitations and future research directions are addressed in each section;

- Conclusion: The final section offers a concise summary of the primary review findings and the objectives of this review.

This paper aims to lay a robust foundation for the development of a fully autonomous positioning/navigation assistant system dedicated to VIPs. The objective is to overcome the limitations inherent in current mobility aids. Such a system would contribute to advancing the field and fostering the development of improved mobility aids for VIPs in complex environments.

2. Literature Review of Types of Vision Impairment

In order to develop a high-performance positioning system for navigation and wayfinding for VIPs, a prerequisite is to consider the details of the diverse visual impairment as classified by the International Classification of Diseases, 11th edition (ICD-11) [2], the UK Certificate of Vision Impairment (CVI), and pertinent international standards. It is worth noting at the onset that International Standards Organisation (ISO), is an independent, non-governmental, international standard development organization composed of representatives from the national standards organizations of member countries. Their headquarters are in Geneva, Switzerland.

2.1. WHO Classification of Visual Impairment

In accordance with the World Health Organization (WHO)guidelines outlined in the ICD-11, Visual Impairment (VI) can be categorized based on distance and near acuity impairment and classified into various severity categories [2], as illustrated in Table 1. In studying visually impaired mobility, it is essential to establish consistent criteria for defining and categorizing the severity of VI to ensure comparability among studies using similar discretized experimental samples. The WHO (2018) [2] classification serves as the global standard, offering a robust and reliable reference framework.

Table 1.

ICD classification of visual impairment severity [2].

However, the categorization introduced by the ICD-11 is primarily limited by its reliance on a fixed visual acuity as the key indicator of any VI level. In reality, visual acuity is inconsistent and varies across different operational scenarios. VIPs exhibit varying performance in different illumination levels; for instance, individuals with Hereditary Retinal Diseases (HRDs) often experience diminished visual function in low-light conditions [3]. Hence, it is important to assess a combination of visual functions in diverse environmental settings. Moreover, the ICD-11 may not incorporate new knowledge that contributes to the current comprehension of VI [4]. Beyond the universal ICD-11 standard [2], regional variations in VI classification may exist across different geographical areas [5].

2.2. UK Classification of Visual Impairment (CVI)

In the UK, the CVI is utilized, and it includes the following two categories of individuals:

- Sight impaired (partially sighted);

- Severely sight impaired (blind).

In 2018, the CVI incorporated self-reporting mechanisms concerning individual living circumstances. Furthermore, the revised CVI excluded both sight variation under different light levels and the comprehensive assessment of peripheral and central field loss [6].

The revised CVI in 2018 introduces increased ambiguity, with two primary limitations: (i) insufficient details regarding the severity of VI and (ii) discrepancies between the UK CVI and ICD-11. This has certain consequences. First, objective measures of visual function may not rigorously detail VI severity, and subjectivity from healthcare professionals can abrogate these measures. Second, misalignments with ICD-11 classifications highlight gaps between global and local standards. Ongoing revisions of the CVI continue to differentiate these standards in their classification methods [5].

2.3. Classification of Visual Impairment in International Research

The significance of employing consistent classification methods in research is essential, ensuring a robust comparison of the results. Ambiguities in international standards result in disparities in describing VI test samples, as illustrated in Table 2, which summarizes ten research works on visual impairment, mobility, and evacuation.

Table 2.

Descriptions of test samples in a selection of studies investigating visually impaired mobility [5].

The main limitations of research outlined in Table 2 include (i) insufficient control for similar variables or an equivalent number of subdivisions, (ii) hindered experimental validity, (iii) lack of precise value, (iv) lack of consideration of participants’ general health conditions, (v) time-consuming self-report and natural history reports, and (vi) high costs for specialists to determine visual function accurately [5].

4. Literature Review of the Requirements of Visually Impaired People

The foundation for developing a positioning and navigation system for VIPs hinges on a thorough exploration of the requirements specific to any particular VI. This is indispensable for validating ongoing research and development efforts in this domain. Section 4.1 of this paper provides detailed definitions of mobility capacity and mobility performance. Furthermore, environmental and user requirements for specific applications are outlined in the same section. Section 4.2 delves into the details of system and user requirements.

4.1. Mobility Capacity, Mobility Performance, Environmental and User Requirements

Mobility capacity is the fundamental ability of individuals to mobilize. This is typically assessed in a controlled setting, often a laboratory, and this evaluation allows for the individual optimization of both physiological and psychological elements. Mobility performance is the realistic ability of an individual to mobilize, accounting for their motivation and considering the influence of the surrounding environment and mobility tools. Figure 3 illustrates the correlation between capacity and performance, elucidating their influence on behavioral modeling. The comprehension of mobility capacity and performance evolves through an iterative methodology, where an individual’s motivation, environment, and mobility tools are systematically isolated, tested, and refined [5].

Figure 3.

Transitioning from mobility capacity to the development of new requirements [5].

In the development of mobility performance, as is evident in several studies [23,24], the fundamental requirements of VIPs encompass the following:

- Obstacle and hazard awareness;

- Orientation and wayfinding (‘Where am I?’).

Prominent intervention methods to enhance mobility performance involve environmental augmentations and the use of mobility aids. The optimization of specific environmental augmentations has been shown to improve mobility performance. These include factors such as illuminance level and color temperature, contrast, color, signage, and auditory, olfactory, and tactile interactions. A research gap is evident, emphasizing the need for future studies to establish specific standards for color temperature, hue, and chroma. Furthermore, exploring their consequences on perceived contrast and objectively measuring mobility performance is crucial for advancing our understanding in this domain [5].

Table 6 outlines the requirements for general environmental features. A literature gap is denoted as a concept yet to be explored in existing research. The significance of these gaps lies in their potential impact on mobility performance. Requirements are categorized as either ‘hard’ (essential) or ‘soft’ (desirable or ideal), aligning with the framework proposed by [23]. These specifications delineate ways in which navigation systems can address current gaps, which are contributed by [25].

Table 6.

Requirements for generic environmental features [5].

4.2. System and User Requirements

Required Navigation Performance (RNP) of positioning, which includes the following: accuracy, integrity, availability, and continuity, is essential for navigation applications such as VIP navigation assistant systems. By providing information with centimeter positioning accuracy in real-time, PNT sensors, such as GNSS, can effectively achieve RNP. For instance, implementing GNSS in mapping and Geographic Information System (GIS) applications expedites the precise data acquisition process, leading to reductions in equipment and labor expenditures [27].

In addition, PNT technologies can provide precise positioning by determining the user’s location on Earth. These technologies can utilize a user’s positioning/timing information to obtain routes and turning instructions. Such PNT technologies can also enable precise time information, thereby helping to synchronize different parts of the navigation system. This ensures the provision of timely information during a VIP’s navigation. Furthermore, technologies are transferable; the knowledge and experience from other PNT applications can support developing the navigation system for VIPs to navigate independently and confidently.

In conjunction with environmental enhancements in Section 4.1, mobility tools with PNT technologies have been devised to aid VIPs. Study [28] categorizes current mobility tools into three distinct types:

- Electronic Travel Aids (ETAs), designed for obstacle detection and hazard awareness;

- Electronic Orientation Aids (EOAs), focused on orientation and wayfinding (‘Where am I?’);

- Binary Electronic Mobility Systems (BEMS) seeks to combine the advantages of both ETAs and EOAs.

These mobility tools have inherent limitations. Early devices predominantly comprised ETAs that struggled to address challenges beyond obstacle detection for a VIP, neglecting their orientation and navigation needs. While the introduction of EOAs aimed to rectify this deficiency, nevertheless, the positioning technology underlying current EOAs falls short in providing comprehensive indoor and outdoor coverage, confining users to a combination of ETAs and EOAs based on the operational scenario. Beyond the conventional ETAs, EOAs, and BEMS, an emergent technology, Sensory Substitution (SS), captures the environment visually and translates it into an alternative sensory input, unlocking the potential to convey a dense array of information to the user. However, a limitation of SS technology lies in its inability to deliver this information density in a medium that can be processed by the user. In summary, for these mobility tools to be effective, they must tackle two major challenges: 1. Effectively categorizing information that is useful to the user. 2. Delivering this information to the user in an accessible and usable format [5].

The deficiencies in these technologies can be attributed to the segregation of visually impaired research between the medical and engineering disciplines, which, as a consequence, has impeded technology developers from accessing a comprehensive set of user requirements.

The following outlines the key user requirements for mobility tools designed for visually impaired individuals within the current positioning domain:

- Smaller Size and Lightweight (higher scalability): Navigation systems with considerable dimensions and weight hinder their adoption by VIPs for navigation purposes;

- Higher Affordability (cost-effectiveness) and Lower Learning Time: The substantial cost and learning time associated with existing systems discourage users from dedicating significant energy to familiarising themselves with the navigation technology;

- Less Infrastructure Implementation: Navigation systems requiring significant environmental changes, such as the installation of BLE beacons at Points of Interest, pose challenges and entail additional infrastructure investments;

- Multimodal Feedback Design: Many assistant aids incorporate only an audio feedback system, which may prove ineffective in noisy environments. Given the critical role of the feedback system in navigation, it should be designed to offer multi-modal feedback options;

- Real-time Information Delivery: The complexity of object detection operations results in delays in real-time information delivery. Any delay poses a risk of exposing users to hazardous situations;

- Privacy Considerations: Digital systems may put VIPs at risk of privacy leaks. None of the mentioned systems have adequately addressed data management, including audio and image data, during and after navigation. Establishing ethical professional standards for system development is crucial to safeguarding users’ data [29];

- Coverage Area/Limitations: Assessing the system’s range from single-room to global capabilities, considering specific environmental limitations that might impact visually impaired users;

- Market Maturity: Examining the development stage of assistive tools for VIPs, from concept to product availability, to determine their market maturity;

- Output Data: Evaluating the types of information provided by the system, including 2D or 3D coordinates, relative or absolute positions, and dynamic parameters such as speed, heading, uncertainty, and variances [30];

- Update Rate: Determining how frequently the system updates information, whether on-event, on request, or at periodic intervals, to meet the needs of VIPs [30];

- Interface: Considering the various interaction interfaces, including man-machine interfaces such as text-based, graphical, and audio, as well as electrical interfaces such as USB, fiber channels, or wireless communications, for optimal accessibility [30];

- Scalability: Assessing the scalability of the system, taking into account its adaptability with area-proportional node deployment and any potential accuracy loss;

- Approval: Considering the legal and regulatory aspects regarding the system’s operation, including its certification by relevant authorities, to ensure compliance with standards and enhance user trust;

- Intrusiveness/User Acceptance: Evaluating the impact of the system on VIPs, distinguishing between disturbing and imperceptible levels of intrusiveness to ensure high user acceptance;

- Number of Users: Determining the system’s capacity for the visually impaired group, ranging from single-user setups (e.g., total station) to support an unlimited number of users (e.g., passive mobile sensors), ensuring inclusivity [30].

- Long-term Performance: Integrating longitudinal studies to assess navigation systems’ usability and effectiveness for VIPs is crucial for understanding their adaptation to changing conditions and ensuring sustainability.

It is evident that a notable research gap exists in quantifying these requirements to a significant extent, given the multitude of criteria; it is challenging for users to identify an optimal system for a specific application. All of the above requirements show the complexity and multidimensionality of the optimization problem faced by users. For each application, the sixteen user requirements above need to be carefully weighed against one another [30]. To meet market demands, any embedded technology must exhibit characteristics such as being cost-effective, energy-efficient, low-latency, compact, requiring minimal maintenance, involving a minimal amount of dedicated infrastructure, and meeting the requirements for RNP across diverse and complex environments.

To bridge the research gap arising from the lack of behavioral data to understand the requirements of VIPs in realistic scenarios, Section 5 explores experimentation at the Pedestrian Accessibility Movement Environment Laboratory (PAMELA) to overcome this. This experimentation aims to investigate and compare the behavior of VIPs both in individual settings and within crowds. The section concludes by consolidating the findings and offering future recommendations derived from the experimentation. This contribution serves to refine the requirements of VIPs for navigation and wayfinding in realistic scenarios.

5. PAMELA Experimentation for Investigating and Comparing the Behavior of Visually Impaired People

This section outlines experimentation conducted to bridge the literature gaps outlined, encompassing the absence of behavioral data for VIPs in individual and crowd scenarios. It addresses the necessity for an empirical and consistent experimental process to effectively overcome the gaps, highlighting the imperative for an empirical and consistently applied experimental process to address this gap.

5.1. Overview of PAMELA Experimentation

The PAMELA (Pedestrian Accessibility Movement Environment Laboratory) experiment aims to observe visually impaired participants in controlled environments, analyzing their behavior amidst unidirectional and opposing crowd flows. The goal is to develop an empirical model predicting the movement of visually impaired people in diverse scenarios, both individually and within crowds, including normal and evacuation situations. The findings from this experiment serve as a basis for subsequent research, contributing to the refinement and expansion of environmental features and indoor navigation systems [5].

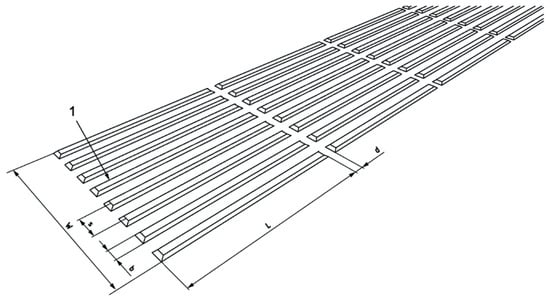

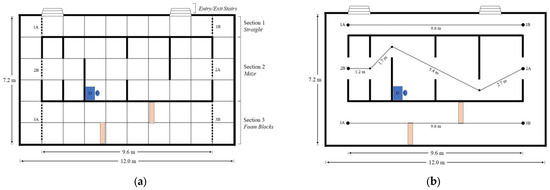

PAMELA serves as a versatile platform for the investigation of pedestrian mobility and environmental interactions under controlled conditions. The facility’s variable lighting system, capable of adjusting illumination levels from near darkness to over 1000 lux, allows for the exploration of the impacts of lighting on mobility. The platform layout, validated for empirical, repeatable, and real-world relevance, consists of three defined sections: (1) a straight path, (2) a maze with barriers, and (3) a straight path with two foam blocks at ground level, 1.2 m in length, 0.2 m in depth, and 0.13 m in height (Figure 4). Lighting, calibrated to a uniform 256 lux at platform level, simulates typical indoor lighting. Cameras positioned over each section record all aspects of the experiment, while Pozyx, a Real-time Locating System (RTLS), tracks participants. Codamotion tracks participants in one section, enabling a separate data fusion study. Video footage, Pozyx, and Codamotion data are cross-compared for reliability, and questionnaires complement data collection. The platform’s controlled environment and integrated systems provide a comprehensive framework for investigating pedestrian behavior and mobility.

Figure 4.

Mobility course configuration and walking path on the platform at PAMELA [5]: (a) sections of the PAMELA platform; (b) proposed walking paths of VIPs.

The testing scenarios included the following five different environments:

- individual;

- unidirectional group flow restricted;

- unidirectional group flow unrestricted;

- opposing group flow restricted;

- opposing group flow unrestricted.

In the individual scenario, participants completed one forward and one reverse pass for each section. For all other scenarios, participants performed one pass per section in a restricted and unrestricted group flow. Restricted scenarios required participants to adhere to the speed of the slowest person, fostering group cohesion, while unrestricted scenarios allowed free traversal without jogging or running, inducing higher stress and dynamic behaviors. Unidirectional group flow involved VIPs in groups with Normally Sighted People (NSPs) moving in one direction. Opposing group flow tested two groups simultaneously, each with up to seven NSPs and one VIP, moving toward each other in opposing directions. Data collected included the following: time to traverse sections, effective speed, qualitative behavior from video footage, walking speed, walking path, and psychological performance from questionnaires.

In participant recruitment, VIPs were classed on the basis of a formal diagnosis of VI beyond correctable refractive errors, supported by a CVI, while NSPs did not have VI beyond correctable refractive errors. Separate questionnaires, detailed in Appendix B and Appendix C, were designed for VIPs and NSPs, covering age, gender, and previous evacuation experience. VIP questionnaires additionally gathered information on VI, and post-experiment sections assessed participant comfort on each platform section using a 5-point Likert scale. These experiments, conducted between 9 and 11 April 2019, involved 61 participants, including 12 VIPs with varied impairments. The experiment has limitations, notably in the uneven age distribution among VIPs, with 10 out of 12 individuals being above 50 years old. While this may present a constraint, it is important to emphasize that the primary factor influencing VIP mobility is the cause of VI, as supported by [31]. To maintain a focus on the diverse impact of distinct visual impairments, this study intentionally excluded individuals who self-reported the onset of age-related mobility problems.

The visually impaired group comprised nine males and three females, exhibiting an uneven age distribution. Table 7 outlines the self-reported visual function ratings (VA: Visual Acuity, CS: Contrast sensitivity, VF: Visual Field), aimed at identifying the most valued visual function, and explores correlations with mobility using a 3-point Likert scale (where 1 is poor, 2 is fair, and 3 is good). In contrast, NSPs had a younger mean age than VIPs in this experiment, potentially limiting the representation of the broader age range in realistic environments. Nevertheless, since the primary role of NSPs is to serve as dynamic obstacles with minimal cognitive interaction, the age difference is not considered to limit this research’s outcomes. Additionally, the older VIPs sample aligns with the higher likelihood of visual impairment occurring with age [5].

Table 7.

Self-reported visual function of the VIPs (CVI: Certificate of Visual Impairment, PVL: Peripheral Vision Loss, SI: Sight Impaired, SSI: Severely Sight Impaired, VA: Visual Acuity, CS: Contrast Sensitivity, VF: Visual Field, SD: Standard Deviation, CV: Coefficient of Variation) [5].

5.2. Summary of Performance of PAMELA Experimentation

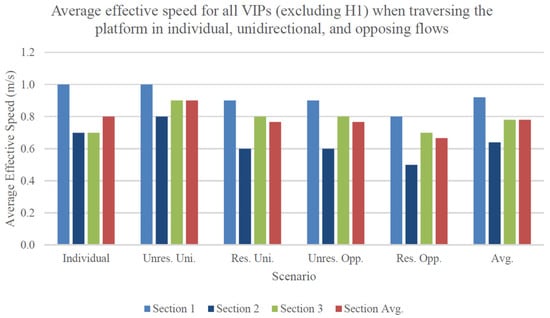

Figure 5 shows the average effective speed for all VIPs (excluding H1 for a fair comparison) during their traversal of the platform in individual, unidirectional, and opposing flows. When considering the section average for each scenario, the effective speeds of VIPs exhibit a remarkable degree of consistency, demonstrating only minor variations (within a range of 0.2 m/s). Ordered in terms of decreasing velocity, the unrestricted unidirectional flow records the highest average effective speed of 0.9 m/s, followed by individual performance, restricted unidirectional, and unrestricted opposing flows (0.8 m/s). Ultimately, the restricted opposing flow presents the lowest average effective speed across sections, measuring at 0.7 m/s.

Figure 5.

Average (avg.) effective speed for all VIPs when traversing the platform in individual, unidirectional, and opposing flows [5].

A major conclusion that can be inferred from these results is that group conditions failed to yield significant disparities in the overall effective performance of VIPs in comparison to their individual performance. Notably, the unrestricted unidirectional flow results in average performance enhancements for the majority of VIPs, in contrast to expectations based on the literature review. Additionally, Section 1 consistently exhibited the most favorable average effective performance, while, except for individual performance, Section 2 presented the least favorable outcomes. This implies that obstacles posed constraints on performance in all scenarios, with larger obstacles (including environmental boundaries) exerting a more substantial limiting effect on group performance when compared with smaller ground-level obstacles.

Table 8 illustrates the distribution of results for the average effective speed of all VIPs (excluding H1) during their traversal of the platform in individual, unidirectional, and opposing flows. The unrestricted unidirectional flow exhibited the smallest spread across sections, followed by the restricted unidirectional and unrestricted opposing flows. Notably, the unrestricted unidirectional flow possessed the largest and most consistent advantage in average effective performance relative to the other scenarios.

Table 8.

Spread of average (avg.) effective speed for all VIPs (H1 excluded) when traversing the platform in individual, unidirectional (uni.), and opposing (opp.) flows (SD: Standard Deviation, CV: Coefficient of Variation, Res.: Restricted, Unres.: Unrestricted) [5].

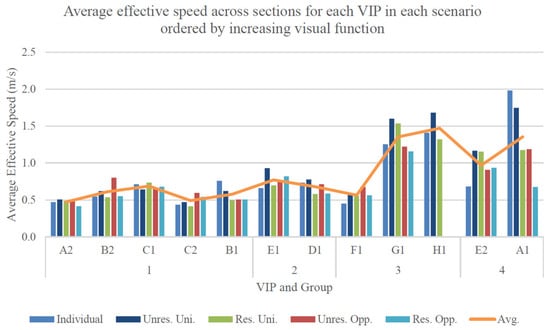

Figure 6 illustrates the average effective walking speed across sections for each VIP in different scenarios (ascending visual function). The VIPs were initially grouped and further sorted based on their self-reported visual function scores within each group. Notably, the visual function scores were discretely categorized into four unevenly sized groups (where Group 1 represents the lowest visual function, and Group 4 represents the highest visual function). This prevents a quantitative assessment of the observed positive trend in effective walking speed with increasing visual function. Additionally, the exclusion of opposing flow data from H1 in calculating their average further limits the available data points for defining this relationship. A more in-depth analysis of each group’s overall average supports the apparent positive trend, with Group 1 exhibiting the lowest average effective speed at 0.6 m/s, followed by Group 2 at 0.7 m/s, Group 3 (excluding H1) at 0.9 m/s, and Group 4 recording the highest value at 1.2 m/s. Despite these trends, the spread of these data does not reveal significant correlations with increasing visual function, most likely because of the limited sample size within each group.

Figure 6.

Average effective speed across sections for each VIP in each scenario ordered by increasing visual function [5].

VIPs were interviewed to determine whether the presence of NSPs affected their behavior. Out of the twelve VIPs surveyed, nine indicated that the presence of NSPs influenced their behavior, with the majority of respondents (seven out of nine) asserting that such influence positively contributed to the overall performance of VIPs. Contrary to expectations, these findings suggest that interactions with NSPs are likely to enhance the performance of VIPs.

It is noteworthy that effective performance within the opposing flows did not solely depend on immediate interactions between opposing groups. Instead, it appears that each VIP may have modulated their walking speed from the beginning of the opposing pass. An inherent limitation lies in the lack of control over the presence of another VIP in every session due to constraints in participant recruitment. Future research should aim to explore opposing flows with a controlled number of VIPs. This is relevant for studies in environments such as hospitals, care homes, or other spaces where VIPs are more prevalent [5].

5.3. Conclusions of PAMELA Experimentation

Understanding VIPs’ requirements involves analyzing their behavior in various scenarios. In group settings, VIPs performed better than in individual scenarios. The unrestricted unidirectional condition showed the highest effectiveness, with 75% of VIPs experiencing improved performance. Conversely, the restricted opposing flow yielded the worst average performance, with only 45% of VIPs showing improvement.

Despite the effectiveness of unrestricted conditions, they led to undesirable behaviors, such as overtaking, collisions, and disorientation. In contrast, the restricted condition provided smoother flows, reflecting the preference of VIPs for enhanced safety and ease of lane formation. In all group scenarios, VIPs utilized the NSPs around them for orientation through visual, auditory, or haptic coupling, enhancing walking efficiency and obstacle avoidance. Unidirectional flows supported this behavior, while opposing flows led to collisions and deadlock.

A positive correlation was found between walking speed and self-reported comfort when VIPs traversed the platform individually. This correlation was maintained in unidirectional flows but diminished in opposing flows. In undesirable group conditions, VIPs’ control of walking behavior is coupled with the crowd’s state while they are decoupled from their psychological state.

NSPs prioritized contact avoidance with VIPs, enabling natural lane formations, particularly in opposing conditions. Removing VIPs from group scenarios resulted in significant reductions in NSP completion times but did not enhance flow safety. Furthermore, NSPs showed reduced effective performance in restricted versus unrestricted conditions. In restricted flows, NSPs preferred a line-abreast group formation, differing from the river-like movement in unrestricted flows, characterized by elevated and varied walking speeds, as defined by [32]. In opposing flows, the inadequate maintenance of group formations resulted in collisions in restricted passes, while collisions occurred at higher speeds in unrestricted passes. Both the NSPs and VIPs expressed a preference for the restricted condition.

In the presence of VIPs, the narrowest section (Section 1) showed the best VIP performance, extending to NSPs in restricted conditions. Removing the VIPs led to the widest section (Section 3), yielding the best NSPs performance. This underscores the VIPs’ impact on flow limitations, particularly in sections with obstacles (Section 2 and Section 3). The classical speed-density relationship applies to NSPs without a VIP but is inapplicable when a VIP is introduced [5].

5.4. Limitations and Recommendations of PAMELA Experimentation

The experiments conducted offer several noteworthy contributions. First, they contribute by carefully examining variations in behavior and performance among individual VIPs when operating independently and within controlled group settings. Second, this study significantly addresses a research gap, as existing models insufficiently associate a static reduction in walking speed to simulate a VIP’s behavior relative to their normally sighted counterpart. Third, it is established that models should consider individual, unidirectional, and opposing flows (including both restricted and unrestricted conditions) due to substantial variations in group behavior among them. Fourth, the experiments reinforce findings from the existing literature. For example, the classical inverse relationship between speed and density, as proposed by [33], persists in NSP-only group conditions. Consequently, while the novel behavior of VIPs is described, realistic NSP performance, as simulated in previous studies, enhances the credibility of the current experiment [5].

There are several limitations to this series of experiments. First, while the experiment has extracted novel VIP–NSP group behaviors, it has not been performed exhaustively, considering the multitude of visual impairment and operational scenarios that exist but could not be adequately represented in this study. The logistical constraints in participant recruitment and clinical visual function testing also restricted the depth to which correlations between speed, density, and visual function could be explored. Nonetheless, the diversity of participants’ visual impairment, ranging from no light sensitivity to moderate partial sight in both eyes, provided a sufficiently comprehensive performance dataset. The inclusion of VIPs with a diverse spectrum of walking speeds allowed for distinct characteristics in each pass.

Second, it is recommended that future research explore larger group sizes, as the maximum unidirectional group size of seven (and fourteen in opposing flows) may be inadequate in generating realistic densities in all scenarios. VIPs’ behavior predominantly constrained group performance, and the threshold at which density became the limiting factor was undiscovered because of the restricted group size.

Finally, the instructions provided to participants may need to be refined. Some participants did not consistently interpret the ‘restricted’ or ‘unrestricted’ instruction. For instance, some understood an unrestricted pass as an opportunity to traverse the platform as quickly as possible, while others interpreted it as an instruction to move freely. This misunderstanding led to inconsistencies in NSP–VIP interactions, with some participants overtaking the VIP while others remained behind, physically guiding the VIP in such instances.

For future experiments on VIP user requirements, it is essential to provide participants with a more comprehensive briefing to ensure their equal understanding of the experiment’s objectives in both unrestricted and restricted conditions. However, it is worth noting that inconsistent VIP–NSP interactions remain realistic due to participants’ individual interpretations of flow conditions [5], as observed in instances where group members assisted each other in evacuations involving VIPs [8].

Subsequent research should build upon the empirical foundations of the PAMELA experimentation to determine their manifestations in real-world scenarios. For example, the PAMELA experimentation did not address performance variations in scenarios such as varying angles of opposing flows (such as the meeting of opposing groups at right-angled intersections) or with environmental changes and different mobility aids, such as guide dogs [5]. In conclusion, future research will validate the proposed PAMELA systems across diverse real-world environments to ensure their practicality and effectiveness.

8. Conclusions and Future Research

All too often, the limited mobility of VIPs greatly affects their quality of life. Moreover, while ISO standards exist to provide them with greater opportunities for increasing their mobility, these suffer from drawbacks that stifle their potential, such as a lack of integration between appropriate software and physical navigation aids. In order for VIPs to fully participate in all activities of society, a high quality, reliable positioning system for their navigation and wayfinding is a pre-requisite. However, a problem arises in that findings in the medical and engineering fields relating to the mobility of VIPs are segregated. This is compounded by the wide spectrum of visual impairment which must be taken into account when devising any navigation and wayfinding system.

This paper attempts to overcome this challenge by initially examining the fundamental mobility requirements for VIPs and, based upon a thorough literature review, derives sixteen major requirements. Unfortunately, behavioral insights to inform VIPs’ mobility needs are often lacking. This paper, therefore, outlines the results of a series of experiments in a specially designed environment at PAMELA. This involved VIPs in various operating scenarios, providing crucial behavioral information for the design of any positioning system for VIP navigation and wayfinding. Based on the fundamental mobility requirements and the VIP behaviors examined, this paper assesses current positioning systems, highlights four major limitations, and provides avenues for further research.

Such research can enhance high-precision positioning technology for VIPs by conducting behavioral experiments in diverse environments. Table A1 in Appendix A provides a summary of the main methodology risks and their mitigation strategies. To address these risks, particularly the low positioning accuracy in GNSS-denied environments, potential improvements include:

- Quantifying the navigation system requirements, given that current knowledge has limitations in defining these for VIPs. This includes accuracy, integrity risk, alarm limits, availability, and continuity. These factors can be derived from user requirements, VIP behaviors, infrastructure environments, and risk analysis. This process may lead to various requirement categories based on the visual function of the VIP and/or their operating environments;

- Quantifying the situational awareness requirements to ensure safety, including the integrity budget;

- Implementing advanced carrier phase GNSS positioning technologies, such as RTK (Real-Time Kinematic) and Precise Point Positioning (PPP), as the current understanding of requirements indicates that a centimeter to decimeter accuracy level is necessary for VIPs’ navigation;

- Developing an integrity monitoring algorithm that supports carrier phase positioning, namely Carrier Phase Receiver Autonomous Integrity Monitoring (CRAIM);

- Developing an integrity monitoring layer for indoor positioning systems. In addition to Fault Detection and Exclusion (FDE) and computing the protection level, this improvement involves identifying faulty modes and models and overbounding the error distribution to ensure safety;

- Conducting a feasibility assessment for indoor positioning systems that can meet VIPs’ navigation requirements. This assessment should follow the system requirements and use the protection level value of each indoor positioning system;

- Developing an integrity monitoring algorithm for SLAM methods in case the feasibility assessment suggests using SLAM;

- Performing a cost–benefit analysis for the candidate indoor positioning systems;

- Developing a situational awareness layer that ensures safety.

Alongside technical advancements, it is crucial to prioritize user comfort in the development of assistive technologies. Potential directions include cost reduction (cost-effectiveness), reduced size and weight to enhance scalability, shortened learning times, implementation of a multimode feedback system, real-time information delivery, and privacy protection. Future research should include interviews or surveys to better understand the needs and preferences of VIPs, as suggested by [61]. These research efforts can make smart cities more inclusive for visually impaired communities. By applying the findings across disciplines, we can improve the accessibility of technologies such as autonomous vehicles for visually impaired groups.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M.F., C.F., A.M. and W.Y.O.; writing—original draft preparation, C.F. and A.M.; writing—review and editing, J.M.F., A.M. and W.Y.O.; supervision, A.M., W.Y.O. and J.M.F.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Summary of methodology of navigation systems for VIPs.

Table A1.

Summary of methodology of navigation systems for VIPs.

| Methodology Category | Methodology Name | Techniques | Limitation(s) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bluetooth-related | Hybrid BLE beacons and Google Tango | 1. ‘Fingerprinting’ method for reducing effects from BLE signal attenuation (with KNN algorithm) 2. Tango (with RGB-D camera) models the 3D indoor environment and performs accurate indoor localization in real-time 3. Close-loop approach to reduce drift errors by Tango 4. BLE beacons provide coarse location detections to find the correct ADF to be loaded in Tango to provide correct users’ positions 5. The app finds the shortest path for navigation between the origin and the selected destinations using Dijkstra’s algorithm | 1. Predicted locations jump around 2. A small algorithm variation leads to varying accuracy in results 3. Tango has drift errors over time in estimating the camera’s positions 4. The size of ADF by Tango is limited to one floor | [40] |

| Bluetooth-related | ASSIST | 1. Body camera (GoPro) captures and sends images to detection server 2. YOLO head detection 3. Detection server to perform facial and emotion recognition 4. Navigation server processes BLE localization 5. The phone performs BLE and Tango localization, provides feedback to users | 1. Easily attenuated BLE signals 2. Loading of a large ADF (exceeds 60 MB) triggers the internal timeout/crash within Tango SDK; the size of the ADF is limited to one floor | [86] |

| Bluetooth-related | Bluetooth indoor positioning based on RSSI and Kalman filtering | 1. Achieve an accurate Bluetooth transmission model: traditional wireless signal propagation model + more training with environmental parameters and standards RSSI values in 1 m 2. Apply Kalman filtering to smooth Bluetooth signals to reduce problems such as signal drift and shock 3. A more accurate positioning by applying the weighted least square algorithm + weight to each element of the error vector 4. Four-border positioning method to calculate the coordinates of the unknown target device | 1. Some positioning points (near the obstacles) have more significant errors than others, far from the real positioning point, meaning the system is not precise 2. Filtering can only lower part of RSSI drifts; a more stable signal is needed 3. The superposition problem should be solved | [87] |

| GNSS-related | Atmospheric augmentation PPP algorithm | 1. Doppler-smoothing reduces the errors/noise of pseudorange measurements and figures out the gross errors 2. Doppler integration method detects carrier phase outliers 3. A stochastic model based on carrier-on-noise can weigh GNSS observation 4. International GNSS Service (IGS) products reduce satellite-related errors 5. Square Root Information Filtering (SRIF) linearizes multi-GNSS and dual-frequency PPP equations for high-robustness positioning results | 1. The phase center offset and variation (in the smartphone GNSS antenna) are not considered due to the lack of information on the patch antenna in correcting receiver errors 2. The future challenge lies in achieving fast, high-precision positioning in GNSS-denial environments, which requires combining PPP technology with other sensors such as IMU, cameras, etc. | [88] |

| Vision-related | VSLAM, PoI-graph, wayfinding, obstacle detection, and route-following algorithm | 1. VSLAM utilizes RGB and depth images to generate an offline ‘virtual blind road’ and localize users online 2. PoI graph is important in wayfinding, where the system plans the global shortest path (A* based algorithm) 3. Route finding: combines all information and applies the dynamic subgoal selection method to build the guiding information | Lack of positioning in outdoor and more complex environments | [38] |

| IMU-related | GNSS, IMU, visual navigation data fusion system | 1. The error compensation module in MSDF can correct scale-factor errors in IMU data and remove bias in IMU data. 2. VO pose estimations converted to E-Frame before data fusion to resolve the earth rotations about I-Frame 3. Kalman filtering or Extended Kalman filtering for data fusion | 1. This architecture is designed for UAVs; further investigations are needed to prove the applicability for VIPs’ navigation 2. Further reduction in the drift errors of IMU and improvement in the sampling rate of vision sensors (to achieve lower computation time for the procession of the image captured) | [89] |

Appendix B

VIPs Questionnaire

Complete Prior to Experiment

Session ID: ___________ Initials: ______ Age: ______ Gender: M/F

(1) What is the diagnosis/cause of your visual impairment and do you have a CVI classification?

__________________________________________________________________________

(2) How would you describe your sight in these categories? (Circle as appropriate)

Acuity (ability to read signs and text) Poor/Fair/Good

Contrast sensitivity (ability to detect poorly lit objects) Poor/Fair/Good

Peripheral vision (seeing objects coming from the side of your vision) Poor/Fair/Good

(3) Do you use any assistive devices? These can include glasses, canes, guide dogs, voice-over software and screen-readers.

__________________________________________________________________________

(4) Please provide any additional details on your visual impairment

__________________________________________________________________________

(5) Have you ever participated in an evacuation (such as a fire drill?) Yes/No

If so, have you ever felt unsafe or unable to evacuate? Yes/No

Please provide additional details as to why this is:

__________________________________________________________________________

Complete Following Experiment

The platform is defined as Section 1: No obstacles, Section 2: Corridors, Section 3: Foam steps

Please rate your comfort in each scenario on a scale of (1) to (5), where (1) is least comfort and (5) is the most.

(1) Individually: Comfort

Section 1 1/2/3/4/5

Section 2 1/2/3/4/5

Section 3 1/2/3/4/5

(2) In the unrestricted single flow: Comfort

Section 1 1/2/3/4/5

Section 2 1/2/3/4/5

Section 3 1/2/3/4/5

(3) In the unrestricted opposing flow: Comfort

Section 1 1/2/3/4/5

Section 2 1/2/3/4/5

Section 3 1/2/3/4/5

(4) When traversing the platform, please rank the following on a scale of (1) to (5), where (1) was the least comfortable scenario, and (5) was the most comfortable scenario.

Individually _____

In a restricted single group flow _____

In an unrestricted single group flow _____

In a restricted opposing group flow _____

In an unrestricted opposing group flow _____

(5) Did you feel that the presence of normally sighted people on the platform affected your actions during the experiment? Yes/No

If so, how, and why was this?

__________________________________________________________________________

(6) Did you feel that the presence of another visually impaired person on the platform (if applicable) affected your actions during the experiment? Yes/No

If so, how, and why was this?

__________________________________________________________________________

Appendix C

NSPs Questionnaire

Complete Prior to Experiment

Session ID: ___________ Initials: ______ Age: ______ Gender: M/F

(1) Have you ever participated in an evacuation (such as a fire drill?) Yes/No

If so, have you ever felt unsafe or unable to evacuate? Yes/No

Please provide additional details as to why this is:

__________________________________________________________________________

Complete Following Experiment

The platform is defined as Section 1: No obstacles, Section 2: Corridors, Section 3: Foam steps

Please rate your comfort in each scenario on a scale of (1) to (5), where (1) is the least comfort and (5) is the most comfort.

(1) In the unrestricted single flow: Comfort

Section 1 1/2/3/4/5

Section 2 1/2/3/4/5

Section 3 1/2/3/4/5

(2) In the unrestricted opposing flow: Comfort

Section 1 1/2/3/4/5

Section 2 1/2/3/4/5

Section 3 1/2/3/4/5

(3) When traversing the platform, please rank the following on a scale of (1) to (5), where (1) was the least comfortable scenario, and (5) was the most comfortable scenario.

In a restricted single group flow _____

In an unrestricted single group flow _____

In a restricted opposing group flow _____

In an unrestricted opposing group flow _____

(4) Did you feel that the presence of visually impaired people on the platform affected your actions during the experiments? Yes/No

If so, how, and why was this?

__________________________________________________________________________

References

- World Health Organization. Blindness and Vision Impairment. 2022. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/blindness-and-visual-impairment (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Diseases (11th Revision); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kumaran, N.; Moore, A.T.; Weleber, R.G.; Michaelides, M. Leber Congenital Amaurosis/Early-Onset Severe Retinal Dystrophy: Clinical Features, Molecular Genetics and Therapeutic Interventions. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2017, 101, 1147–1154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dandona, L.; Dandona, R. Revision of Visual Impairment Definitions in the International Statistical Classification of Diseases. BMC Med. 2006, 4, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feghali, J.M. Function to Functional: Investigating the Fundamental Human, Environmental, and Technological Factors Affecting the Mobility of Visually Impaired People. 2022.

- Great Britain Department of Health and Social Care. Certificate of Vision Impairment for People Who are Sight Impaired (Partially Sighted) or Severely Sight Impaired (Blind). 2018. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/6318b725d3bf7f77d2995a5c/certificate-of-vision-impairment-form.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- Samoshin, D.; Istratov, R. The Characteristics of Blind and Visually Impaired People Evacuation in Case of Fire. Fire Saf. Sci. 2014, 11, 1160–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørensen, J.G.; Dederichs, A.S. Evacuation Characteristics of Visually Impaired People—A Qualitative and Quantitative Study. Fire Mater. 2015, 39, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manduchi, R.; Kurniawan, S. Mobility-Related Accidents Experienced by People with Visual Impairment. AER J. Res. Pract. Vis. Impair. Blind. 2011, 4, 44–54. [Google Scholar]

- Long, R.G.; Rieser, J.J.; Hill, E.W. Mobility in Individuals with Moderate Visual Impairments. J. Vis. Impair. Blind. 1990, 84, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swenor, B.K.; Muñoz, B.; West, S.K. Does Visual Impairment Affect Mobility Over Time? the Salisbury Eye Evaluation Study. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2013, 54, 7683–7690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, M.S.; Cook, G.K.; Webber, G.M.B. Emergency Lighting and Wayfinding Provision Systems for Visually Impaired People: Phase I of a Study. Int. J. Light. Res. Technol. 1999, 31, 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Salive, M.E.; Guralnik, J.; Glynn, R.J.; Christen, W.; Wallace, R.B.; Ostfeld, A.M. Association of Visual Impairment with Mobility and Physical Function. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1994, 42, 287–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zeng, J.; Liu, X.; Ding, S. Effect of Obstacle Density on the Travel Time of the Visually Impaired People. Fire Mater. 2019, 43, 162–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leat, S.J.; Lovie-Kitchin, J. Visual Function, Visual Attention, and Mobility Performance in Low Vision. Optom. Vis. Sci. 2008, 85, 1049–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brouwer, D.M.; Sadlo, G.; Winding, K.; Hanneman, M.I.G. Limitations in Mobility: Experiences of Visually Impaired Older People. Br. J. Occup. Ther. 2008, 71, 414–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BS ISO 21542; Building Construction. Accessibility and Usability of the Built Environment. International Organisation of Standards: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 90–117.

- BS EN ISO 9241-171:2008; Ergonomics of Human-System Interaction: Guidance on Software Accessibility. International Organisation of Standards: Geneva, Switzerland, 2009.

- EN 301 549; European Standard for Digital Accessibility. European Telecommunications Standards Institute: Sophia Antipolis, France, 2021.

- United States Department of Justice. 2010 ADA Standards for Accessible Design; United States Department of Justice: Washington, DC, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- BS 8300-1:2018; Design of an Accessible and Inclusive Built Environment—External Environment. Code of Practice. The British Standards Institution: London, UK, 2018.

- BS 8300-2:2018; Design of an Accessible and Inclusive Built Environment—Building. Code of Practice. The British Standards Institution: London, UK, 2018.

- Strothotte, T.; Fritz, S.; Michel, R.; Raab, A.; Petrie, H.; Johnson, V.; Reichert, L.; Schalt, A. Development of Dialogue Systems for the Mobility Aid for Blind People: Initial Design and Usability Testing. In Proceedings of the Second Annual ACM Conference on Assistive Technologies, New York, NY, USA, 11–12 April 1996; pp. 139–144. [Google Scholar]

- Loomis, J.M.; Golledge, R.D.; Klatzky, R.L. GPS-Based Navigation Systems for the Visually Impaired; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 2001; pp. 429–446. [Google Scholar]

- Spinks, R.; Worsfold, J.; Di Bon-Conyers, L.; Williams, D.; Ochieng, W.Y.; Mericliler, G. Interviewed by: Feghali, J.M. 2021. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vLgWKestjEE (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- Wayfindr. Open Standard for Audio-Based Wayfinding—Recommendation 2.0. 2018. Available online: http://www.wayfindr.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/Wayfindr-Open-Standard-Rec-2.0.pdf (accessed on 19 August 2024).

- El-Sheimy, N.; Lari, Z. GNSS Applications in Surveying and Mobile Mapping; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 1711–1733. [Google Scholar]

- Feghali, J.M.; Mericliler, G.; Penrod, W.; Lee, D.B.; Kaiser, J. How Much Is Too Much? Understanding the Appropriate Amount of Information from ETAs and EOAs for Effective Mobility; Berndtsson, I., IMC Executive Committee, Eds.

- Kuriakose, B.; Shrestha, R.; Sandnes, F.E. Tools and Technologies for Blind and Visually Impaired Navigation Support: A Review. IETE Tech. Rev. 2022, 39, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mautz, R. Indoor Positioning Technologies; ETH Zurich: Zürich, Switzerland, 2012; pp. 15–16. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, I.; Turano, K.A.; Broman, A.T.; Bandeen-Roche, K.; Munoz, B.; West, S.K. Measures of Visual Function and Percentage of Preferred Walking Speed in Older Adults: The Salisbury Eye Evaluation Project. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2006, 47, 65–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moussaïd, M.; Perozo, N.; Garnier, S.; Helbing, D.; Theraulaz, G. The Walking Behaviour of Pedestrian Social Groups and its Impact on Crowd Dynamics. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e10047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weidmann, U. Transporttechnik Der Fussgänger; Institut für Verkehrsplanung: Zürich, Switzerland, 1992; Volume 90. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y.; Li, Z.; Li, G.; Wang, B.; Zhu, M.; Shi, P. Multi-Sensory Visual-Auditory Fusion of Wearable Navigation Assistance for People With Impaired Vision. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2023, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Munoz, J.P.; Rong, X.; Chen, Q.; Xiao, J.; Tian, Y.; Arditi, A.; Yousuf, M. Vision-Based Mobile Indoor Assistive Navigation Aid for Blind People. IEEE Trans. Mob. Comput. 2019, 18, 702–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masud, U.; Saeed, T.; Malaikah, H.M.; Islam, F.U.; Abbas, G. Smart Assistive System for Visually Impaired People Obstruction Avoidance through Object Detection and Classification. Access 2022, 10, 13428–13441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarze, T.; Lauer, M.; Schwaab, M.; Romanovas, M.; Böhm, S.; Jürgensohn, T. A Camera-Based Mobility Aid for Visually Impaired People. Künstl. Intell. 2016, 30, 29–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, J.; Lian, S.; Liu, Z.; Wang, K.; Liu, D. Virtual-Blind-Road Following-Based Wearable Navigation Device for Blind People. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2018, 64, 136–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ton, C.; Omar, A.; Szedenko, V.; Tran, V.H.; Aftab, A.; Perla, F.; Bernstein, M.J.; Yang, Y. LIDAR Assist Spatial Sensing for the Visually Impaired and Performance Analysis. IEEE Trans. Neural Syst. Rehabil. Eng. 2018, 26, 1727–1734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nair, V.; Tsangouri, C.; Xiao, B.; Olmschenk, G.; Seiple, W.H.; Zhu, Z. A Hybrid Indoor Positioning System for Blind and Visually Impaired using Bluetooth and Google Tango. J. Technol. Pers. Disabil. 2018, 6, 61–81. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Sala, A.; Losilla, F.; Sánchez-Aarnoutse, J.; García-Haro, J. Design, Implementation and Evaluation of an Indoor Navigation System for Visually Impaired People. Sensors 2015, 15, 32168–32187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sammouda, R.; Alrjoub, A. Mobile Blind Navigation System using RFID. In Proceedings of the 2015 Global Summit on Computer & Information Technology (GSCIT), Sousse, Tunisia, 11–13 June 2015; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Patil, K.; Jawadwala, Q.; Shu, F.C. Design and Construction of Electronic Aid for Visually Impaired People. IEEE Trans. Hum. Mach. Syst. 2018, 48, 172–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bindhu, V.; Tavares, J.M.R.S.; Boulogeorgos, A.A.; Vuppalapati, C. Indoor Navigation Assistant for Visually Impaired (INAVI); Springer Singapore Pte. Limited: Singapore, 2021; pp. 239–253. [Google Scholar]

- Kammoun, S.; Bouaziz, R.; Saeed, F.; Qasem, S.N.; Al-Hadhrami, T. HaptiSole: Wearable Haptic System in Vibrotactile Guidance Shoes for Visually Impaired Wayfinding. KSII Trans. Internet Inf. Syst. 2023, 17, 3064–3082. [Google Scholar]

- Sato, D.; Oh, U.; Naito, K.; Takagi, H.; Kitani, K.; Asakawa, C. NavCog3: An Evaluation of a Smartphone-Based Blind Indoor Navigation Assistant with Semantic Features in a Large-Scale Environment. In Proceedings of the 19th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility (ASSETS ‘17), Baltimore, MD, USA, 20 October–1 November 2017; pp. 270–279. [Google Scholar]

- Marzec, P.; Kos, A. Low Energy Precise Navigation System for the Blind with Infrared Sensors. In Proceedings of the 2019MIXDES—26th International Conference “Mixed Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems”, Rzeszow, Poland, 27–29 June 2019; pp. 394–397. [Google Scholar]

- Guerreiro, J.A.; Ahmetovic, D.; Sato, D.; Kitani, K.; Asakawa, C. Airport Accessibility and Navigation Assistance for People with Visual Impairments. In Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Glasgow, Scotland UK, 2 May 2019; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Kuriakose, B.; Shrestha, R.; Sandnes, F.E. DeepNAVI: A Deep Learning Based Smartphone Navigation Assistant for People with Visual Impairments. Expert Syst. Appl. 2023, 212, 118720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo Guerrero, J.; Quezada-V, C.; Chacon-Troya, D. Design and Implementation of an Intelligent Cane, with Proximity Sensors, GPS Localization and GSM Feedback. In Proceedings of the In 2018 IEEE Canadian Conference on Electrical & Computer Engineering (CCECE), Quebec, QC, Canada, 13–16 May 2018; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Saaid, M.F.; Mohammad, A.M.; Megat Ali, M.S.A.M. Smart Cane with Range Notification for Blind People. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Conference on Automatic Control and Intelligent Systems (I2CACIS), Selangor, Malaysia, 22–22 October 2016; pp. 225–229. [Google Scholar]

- Elmannai, W.; Elleithy, K. Sensor-Based Assistive Devices for Visually-Impaired People: Current Status, Challenges, and Future Directions. Sensors 2017, 17, 565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, Z.A. Design and Evaluation of Two Obstacle Detection Devices for Visually Impaired People. J. Eng. Res. 2023, 11, 100–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinde, S.H.; Munot, M.V.; Kumar, P.; Boob, S. Intelligent Companion for Blind: Smart Stick. Int. J. Innov. Technol. Explor. Eng. 2019, 8, 2278–3075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Alwis, D.; Samarawickrama, Y.C. Low Cost Ultrasonic Based Wide Detection Range Smart Walking Stick for Visually Impaired. Int. J. Multidiscip. Stud. 2016, 3, 123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yusof, Z.M.; Billah, M.M.; Kadir, K.; Rohim, M.A.; Nasir, H.; Izani, M.; Razak, A. Design and Analysis of a Smart Blind Stick for Visual Impairment. Indones. J. Electr. Eng. Comput. Sci. 2018, 11, 848–856. [Google Scholar]

- Mukhiddinov, M.; Cho, J. Smart Glass System using Deep Learning for the Blind and Visually Impaired. Electronic 2021, 10, 2756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, S.U.; Ranganath, S.; Ashwin, T.S.; Reddy, G.R.M. A Google Glass Based Real-Time Scene Analysis for the Visually Impaired. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 166351–166369. [Google Scholar]

- Kuriakose, B.; Shrestha, R.; Sandnes, F.E. Exploring the User Experience of an AI-Based Smartphone Navigation Assistant for People with Visual Impairments. In Proceedings of the 15th Biannual Conference of the Italian SIGCHI Chapter, Torino, Italy, 20–22 September 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Fusco, G.; Coughlan, J.M. Indoor Localization for Visually Impaired Travelers using Computer Vision on a Smartphone. In Proceedings of the 17th International Web for all Conference, Taipei, Taiwan, 20–21 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, W.; Xie, Z.; Yuan, P.; Wang, R.; Chen, H.; Xiao, B. A Mobile Intelligent Guide System for Visually Impaired Pedestrian. J. Syst. Softw. 2023, 195, 111546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girshick, R.; Donahue, J.; Darrell, T.; Malik, J. Rich Feature Hierarchies for Accurate Object Detection and Semantic Segmentation. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Columbus, OH, USA, 23–28 June 2014; pp. 580–587. [Google Scholar]

- Dai, J.; Li, Y.; He, K.; Sun, J. R-FCN: Object Detection Via Region-Based Fully Convolutional Networks. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Barcelona, Spain, 5–10 December 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Szegedy, C.; Reed, S.; Fu, C.; Berg, A.C. Ssd: Single Shot Multibox Detector. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ECCV 2016: 14th European Conference, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 11–14 October 2016; pp. 21–37. [Google Scholar]

- Bochkovskiy, A.; Wang, C.; Liao, H.M. Yolov4: Optimal Speed and Accuracy of Object Detection. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2004.10934. [Google Scholar]

- Moharkar, L.; Varun, S.; Patil, A.; Pal, A. A Scene Perception System for Visually Impaired Based on Object Detection and Classification using CNN. ITM Web Conf. 2020, 32, 03039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashiq, F.; Asif, M.; Ahmad, M.B.; Zafar, S.; Masood, K.; Mahmood, T.; Mahmood, M.T.; Lee, I.H. CNN-Based Object Recognition and Tracking System to Assist Visually Impaired People. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 14819–14834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, R.C.; Yadav, S.; Dutta, M.K.; Travieso-Gonzalez, C.M. Efficient Multi-Object Detection and Smart Navigation using Artificial Intelligence for Visually Impaired People. Entropy 2020, 22, 941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahraman, M.; Turhan, C. An Intelligent Indoor Guidance and Navigation System for the Visually Impaired. Assist. Technol. 2022, 34, 478–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barontini, F.; Catalano, M.G.; Pallottino, L.; Leporini, B.; Bianchi, M. Bianchi. Integrating Wearable Haptics and Obstacle Avoidance for the Visually Impaired in Indoor Navigation: A User-Centered Approach. IEEE Trans. Haptics 2021, 14, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuriakose, B.; Shrestha, R.; Sandnes, F.E. SceneRecog: A Deep Learning Scene Recognition Model for Assisting Blind and Visually Impaired Navigate using Smartphones. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC), Melbourne, Australia, 17–20 October 2021; pp. 2464–2470. [Google Scholar]

- Plikynas, D.; Žvironas, A.; Budrionis, A.; Gudauskis, M. Indoor Navigation Systems for Visually Impaired Persons: Mapping the Features of Existing Technologies to User Needs. Sensors 2020, 20, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theodorou, P.; Meliones, A. Gaining Insight for the Design, Development, Deployment and Distribution of Assistive Navigation Systems for Blind and Visually Impaired People through a Detailed User Requirements Elicitation. Univ. Access Inf. Soc. 2022, 22, 841–867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akter, T.; Dosono, B.; Ahmed, T.; Kapadia, A.; Semaan, B. I Am Uncomfortable Sharing what I Can See: Privacy Concerns of the Visually Impaired with Camera Based Assistive Applications. In Proceedings of the 29th USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 20), Berkeley, CA, USA, 12 August 2020; pp. 1929–1948. [Google Scholar]

- Ran, X.; Chen, H.; Zhu, X.; Liu, Z.; Chen, J. DeepDecision: A Mobile Deep Learning Framework for Edge Video Analytics. In Proceedings of the IEEE INFOCOM 2018—IEEE Conference on Computer Communications, Honolulu, HI, USA, 16–19 April 2018; pp. 1421–1429. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, H.M.; Khan, H.M.; Abbas, K.; Abbas, K.; Khan, H.N.; Khan, H.N. Investigating the Impact of COVID-19 on Individuals with Visual Impairment. Br. J. Vis. Impair 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lourens, H. The politics of touch-based help for visually impaired persons during the COVID-19 pandemic: An autoethnographic account. In The COVID-19 Crisis; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2021; pp. 67–76. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo, J.; Beheshti, M.; Fang, Y.; Flanagan, S.; Giudice, N.A. COVID-19 and Visual Disability: Can’t Look and Now Don’t Touch. PM&R 2021, 13, 415–421. [Google Scholar]

- Bernard, A.; Weiss, S.; Rahman, M.; Ulin, S.S.; D’Souza, C.; Salgat, A.; Panzer, K.; Stein, J.D.; Meade, M.A.; McKee, M.M. The Impact of COVID-19 and Pandemic Mitigation Measures on Persons with Sensory Impairment. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 234, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shalaby, W.S.; Odayappan, A.; Venkatesh, R.; Swenor, B.K.; Ramulu, P.Y.; Robin, A.L.; Srinivasan, K.; Shukla, A.G. The Impact of COVID-19 on Individuals Across the Spectrum of Visual Impairment. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 227, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gombas, J.; Csakvari, J. Experiences of Individuals with Blindness Or Visual Impairment during the COVID-19 Pandemic Lockdown in Hungary. Br. J. Vis. Impair. 2021, 40, 378–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahfuz, S.; Sakib, M.N.; Husain, M.M. A Preliminary Study on Visually Impaired Students in Bangladesh during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Policy Futures Educ. 2022, 20, 402–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrestha, S.; Lu, D.; Tian, H.; Cao, Q.; Liu, J.; Rizzo, J.; Seiple, W.H.; Porfiri, M.; Fang, Y. Active Crowd Analysis for Pandemic Risk Mitigation for Blind Or Visually Impaired Persons. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision—ECCV 2020 Workshops, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; pp. 422–439. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, G.; Pundlik, S. Influence of COVID-19 Lockdowns on the Usage of a Vision Assistance App among Global Users with Visual Impairment: Big Data Analytics Study. J. Med. Internet Res. 2021, 23, e26283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellomo, N.; Chaplain, M.A. Predicting Pandemics in a Globally Connected World, Volume 1: Toward a Multiscale, Multidisciplinary Framework Through Modeling and Simulation; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Nair, V.; Budhai, M.; Olmschenk, G.; Seiple, W.H.; Zhu, Z. ASSIST: Personalized Indoor Navigation Via Multimodal Sensors and High-Level Semantic Information; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 0–0. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, C.; Yuan, J.; Liu, H.; Qiu, J. Bluetooth Indoor Positioning Based on RSSI and Kalman Filter. Wirel. Pers. Commun. 2017, 96, 4115–4130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zheng, F.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, D.; Shi, C. Instantaneous Sub-Meter Level Precise Point Positioning of Low-Cost Smartphones. Navigation 2023, 70, navi.597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balamurugan, G.; Jayaraman, V.; Naidu, D.V. Survey on UAV Navigation in GPS Denied Environments. In Proceedings of the2016 International Conference on Signal Processing, Communication, Power and Embedded System (SCOPES), Paralakhemundi, India, 3–5 October 2016; pp. 198–204. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).