Abstract

Hair loss is a common condition that affects a large number of people worldwide, impacting both men and women. Its development is closely linked to the function of hair follicle dermal papilla cells (HFDPCs), which play a pivotal role in maintaining hair growth and follicle integrity. However, these cells are particularly vulnerable to oxidative stress generated under psychological or environmental stressful conditions. Preserving the mitochondrial function and biological activity of HFDPCs is critical for preventing stress-related hair loss. This study investigated the protective and hair growth-promoting effects of 3-hydroxypropionic acid (3-HP), a naturally occurring organic acid with antioxidant potential, on HFDPCs exposed to H2O2-induced oxidative stress conditions. Treatment with 3-HP significantly enhanced cell viability and migration in H2O2-damaged HFDPCs. In addition, 3-HP reduced intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) accumulation and improved mitochondrial membrane potential as well as ATP production. Furthermore, 3-HP upregulated alkaline phosphatase (ALP) expression and activated hair growth-related signaling pathways, including the Wnt/β-catenin axis. Finally, treatment with 3-HP resulted in a significant enlargement of three-dimensional spheroids in H2O2-damaged HFDPCs. These findings suggest that 3-HP mitigates oxidative stress-induced damage and promotes hair follicle cell function, indicating its promise as a treatment option for improving oxidative stress-related hair loss conditions.

1. Introduction

Hair loss (alopecia) is highly prevalent and adversely affects psychological well-being and quality of life. Hair follicles undergo distinct growth, regression, and resting phases—anagen, catagen, and telogen-during which the dermal papilla functions as a central mesenchymal niche coordinating epithelial-mesenchymal interactions [1,2]. HFDPCs reside in the dermal papilla and contribute to the induction and sustainment of the anagen phase through the secretion of diverse growth factors and extracellular matrix components that regulate neighboring epithelial cells [3,4]. They secrete a wide range of growth factors, including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), which are crucial for hair follicle development and hair shaft elongation [5,6]. The functionality of HFDPCs is influenced by various intrinsic and extrinsic factors, with oxidative stress recognized as a major contributor [7]. Oxidative stress reflects a state in which reactive oxygen species (ROS) overwhelm endogenous antioxidant systems [8]. Excessive ROS can damage cellular components, including lipids, proteins, and DNA, leading to impaired cell function or apoptosis [9]. Such oxidative injury has been closely associated with hair follicle miniaturization, premature entry into catagen, and the progression of alopecia [10]. Previous reports indicate that HFDPCs derived from balding scalp tissue are more vulnerable to oxidative stress, leading to enhanced secretion of transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β), a well-established inhibitor of hair growth, and accelerated cellular senescence [11,12]. Furthermore, mitochondrial dysfunction in HFDPCs can exacerbate ROS production, creating a vicious cycle that impairs hair follicle regeneration [13,14]. Activation of the nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) signaling pathway enhances cellular resistance to oxidative damage through the induction of antioxidant and cytoprotective enzymes [15,16]. Activation of Nrf2 signaling in HFDPCs is therefore considered a key protective response that not only restores redox homeostasis but also helps preserve their inductive potential, thereby supporting hair growth and follicular health [17,18].

Recent studies show that oxidative stress not only disrupts intracellular redox balance but also impairs growth-related signaling networks that are essential for follicular maintenance [19]. Among these networks, the Wnt/β-catenin pathway plays a pivotal role in initiating anagen, sustaining dermal papilla inductivity, and supporting epithelial cell proliferation [20]. Reduced Wnt/β-catenin activity has been observed in prematurely regressing or miniaturized follicles, indicating that oxidative stress can suppress canonical Wnt signaling and thereby hinder transcriptional programs required for hair growth [21]. Growing evidence also demonstrates functional crosstalk between Nrf2-mediated antioxidant defenses and Wnt/β-catenin signaling [22,23]. Nrf2 activation can stabilize β-catenin and enhance the expression of its downstream targets under oxidative conditions, whereas diminished Nrf2 activity increases susceptibility to ROS-induced β-catenin degradation [24,25]. This reciprocal interaction suggests that maintaining redox homeostasis is critical for preserving the Wnt-dependent regenerative capacity of dermal papilla cells [26].

Given the detrimental effects of oxidative stress on HFDPCs and hair follicle integrity, there is increasing interest in identifying compounds capable of mitigating ROS-induced cellular damage [27]. Natural antioxidants have been widely investigated for their potential to protect HFDPCs from oxidative stress and thereby preserve hair follicle function [28,29]. 3-Hydroxypropionic acid (3-HP) has recently attracted attention as a bioactive molecule with putative antioxidant properties [30]. Although some biochemical studies have noted that 3-HP participates in cellular metabolic and redox-related pathways [31,32], these findings do not establish a defined antioxidant mechanism and have not been evaluated in hair follicle systems. Furthermore, unlike conventional thiol-based antioxidants such as glutathione or N-acetylcysteine, the mechanistic basis of 3-HP’s antioxidant actions remains unclear, and any potential distinctions should be considered hypothetical at this stage.

In this study, we aimed to elucidate the protective and regenerative effects of 3-HP on HFDPCs subjected to oxidative stress induced by hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). We hypothesized that 3-HP could mitigate oxidative damage, enhance mitochondrial function, and promote the expression of hair growth-related markers in HFDPCs. Insights into the function of 3-HP may contribute to the advancement of alternative approaches for managing oxidative stress-induced hair loss.

2. Results

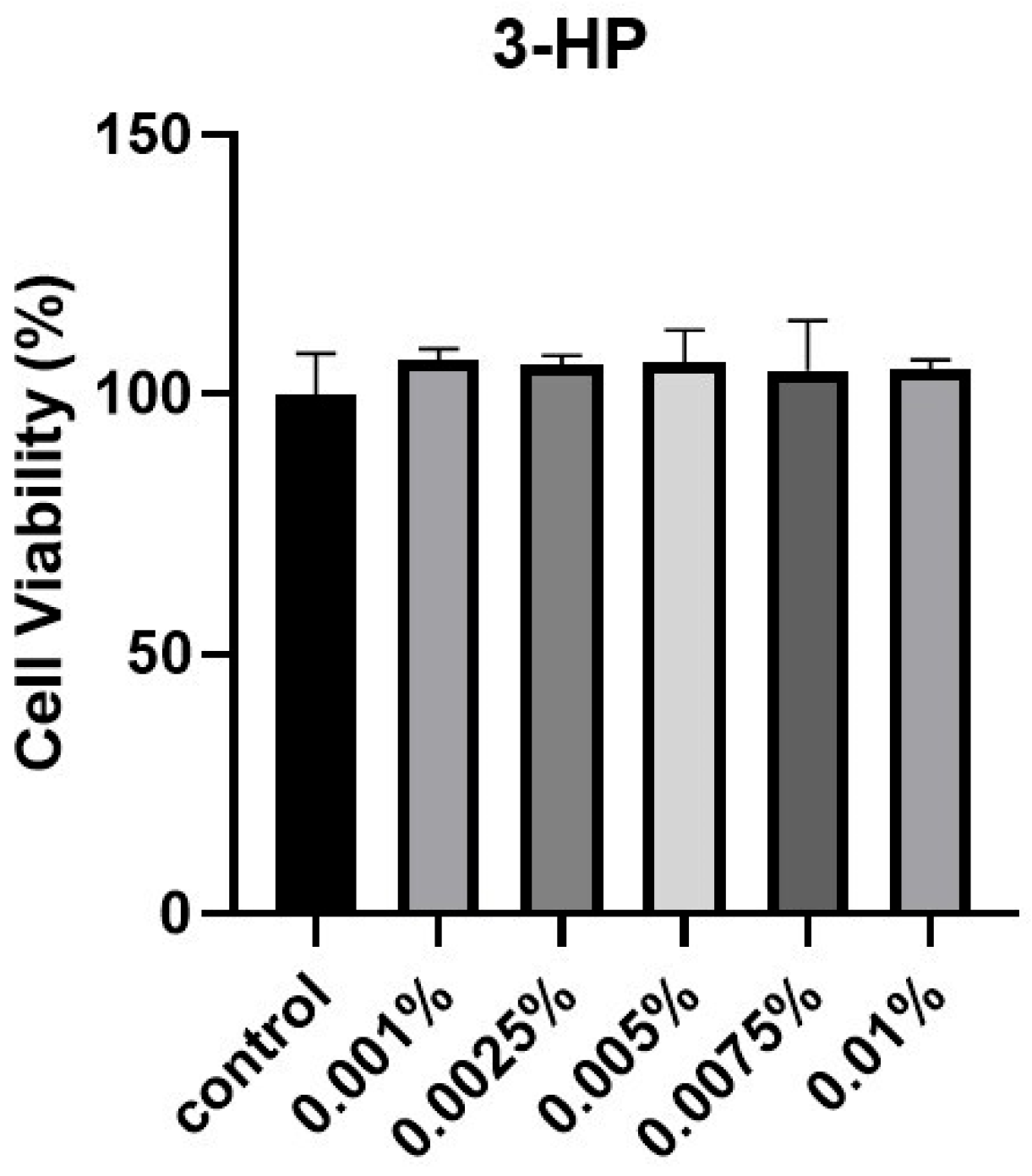

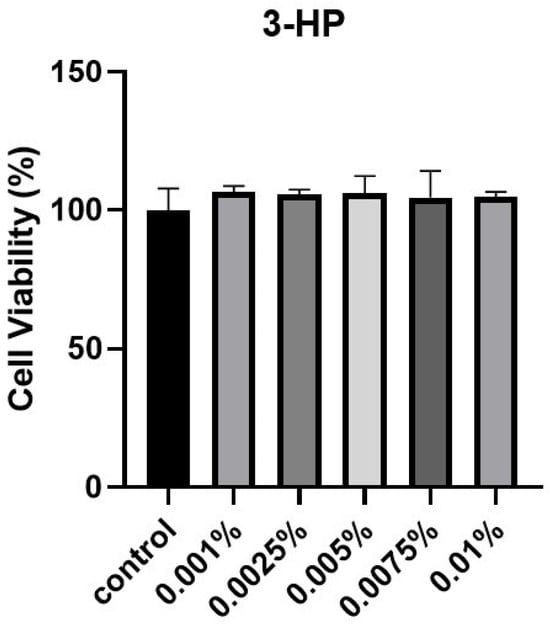

2.1. The Cell Viability of HDPCs Treated by 3-HP

To evaluate the effect of 3-HP on cell viability, HFDPCs were subjected to the EZ-Cytox cell viability assay. Cells treated with 3-HP exhibited higher viability compared with the untreated control group (Figure 1). Based on these results, concentrations from 0.005 to 0.01% were selected for subsequent experiments. In the preliminary cytotoxicity Test, concentrations above 0.02% significantly reduced cell viability, indicating potential cytotoxic effects. Therefore, 0.005–0.01% were selected as non-toxic and physiologically relevant concentrations for subsequent experiments.

Figure 1.

The influence of 3-HP on cellular viability. HFDPC viability was assessed via the EZ-Cytox assay following treatment with various concentrations of 3-HP for 24 h. This experiment was performed with at least three (n ≥ 3).

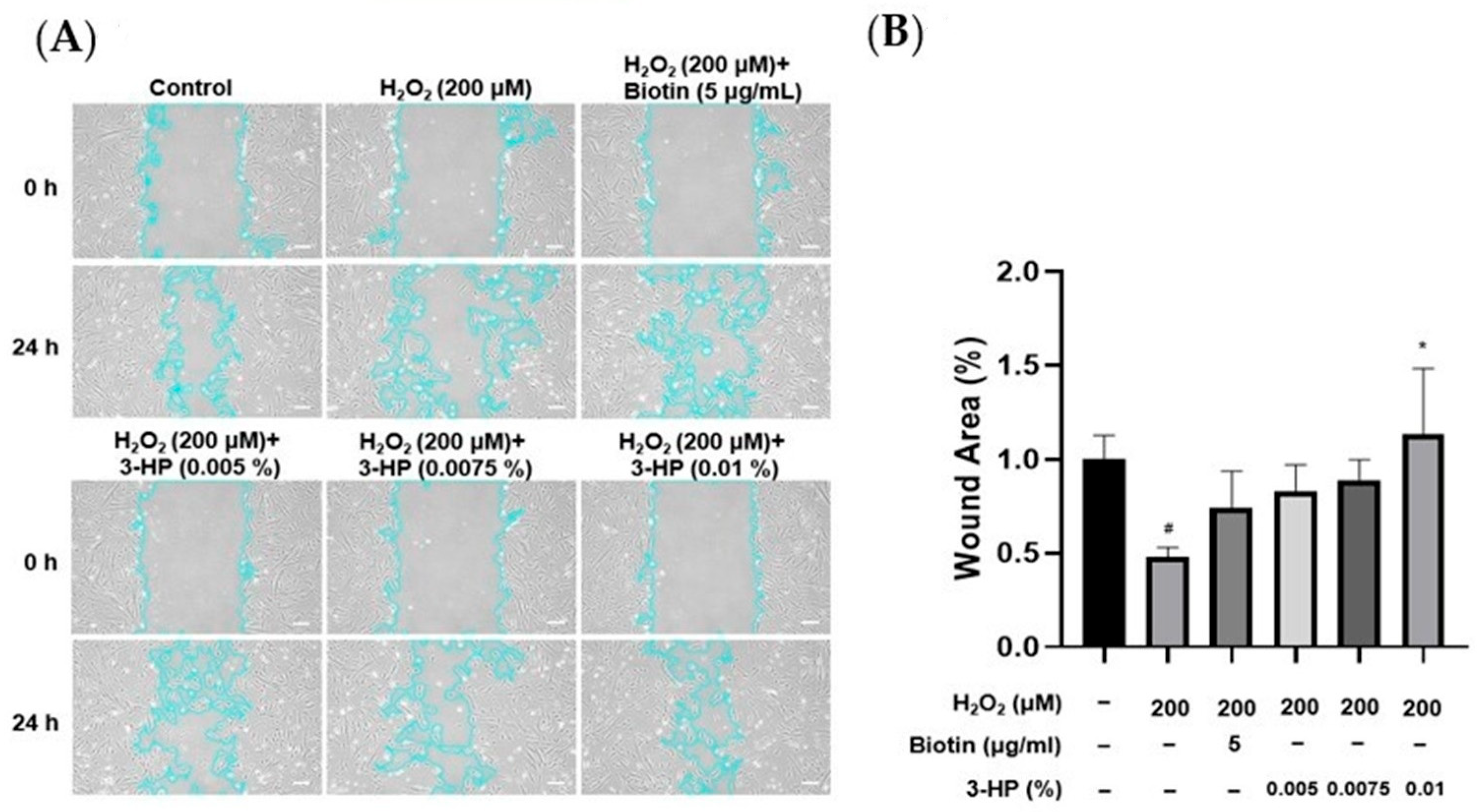

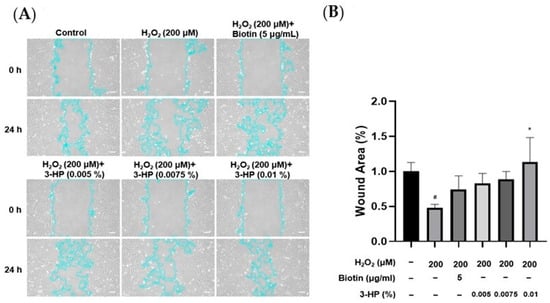

2.2. 3-HP Enhanced the Cell Wound Healing Ability of HFDPCs Damaged by H2O2

The migratory capacity of HFDPCs is essential for hair growth, as increased mobility of these cells is closely linked to the expansion of dermal papilla volume, which plays a pivotal role in regulating follicle size and hair shaft formation [33,34]. To evaluate the effect of 3-HP on wound healing, the cell migration of HFDPCs was evaluated under oxidative stress triggered by H2O2. A linear scratch was created on a confluent cell monolayer using a sterile pipette tip, and wound closure was monitored over 24 h. Compared with cells treated with H2O2 alone, the 3-HP-treated group demonstrated a significantly higher rate of wound closure, indicating enhanced migratory activity (Figure 2). These results indicate that 3-HP enhances the migratory capacity of HFDPCs and facilitates gap closure in an oxidative stress environment.

Figure 2.

The effect of 3-HP on enhancing cell migration in H2O2-damaged HFDPCs. (A) Cell migration was assessed at 0 and 24 h in HFDPCs exposed to oxidative stress induced by H2O2 and subsequently treated with 3-HP at concentrations ranging from 0.005% to 0.01%. The outlines of the cells are highlighted in light blue. (B) Quantitative analysis of the wound area (%), calculated using ImageJ software (version 1.53e). Data were presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3). * p < 0.05 vs. H2O2-treated group, # p < 0.05 vs. control group. Scale bar: 20 µm.

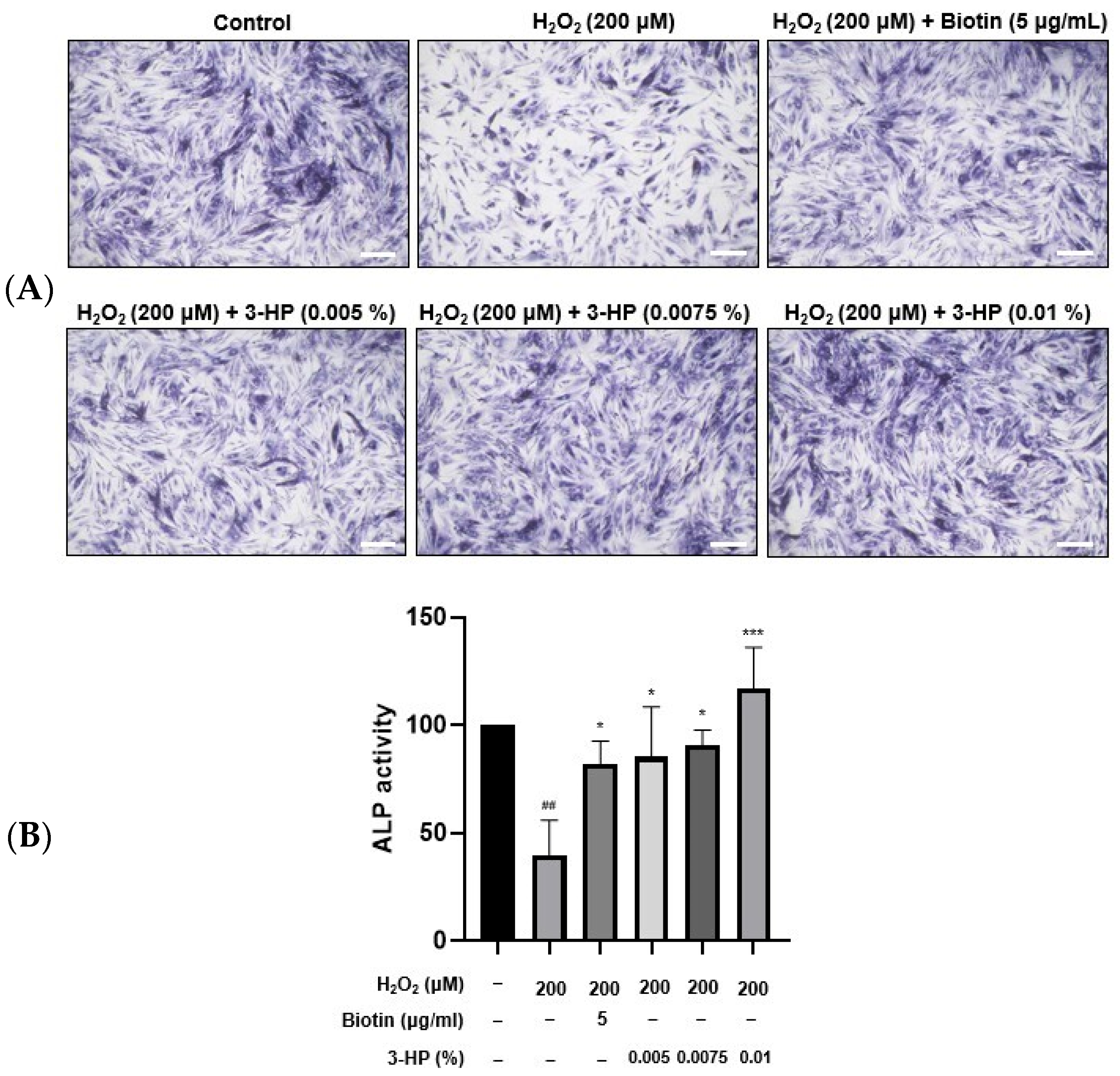

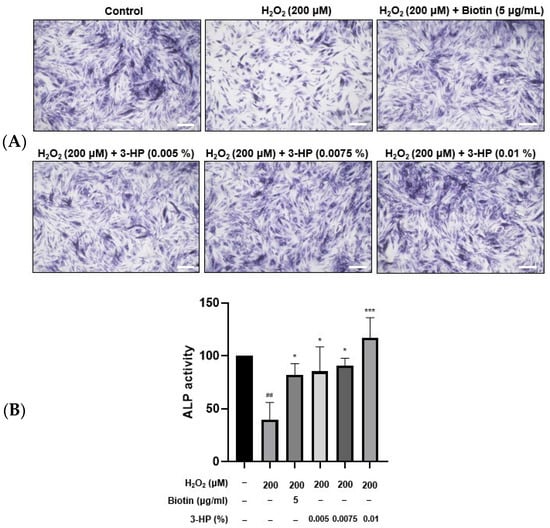

2.3. 3-HP Promoted ALP Expression in H2O2-Damaged HFDPCs

ALP plays an important role in stimulating hair follicle development and initiating hair shaft formation [35,36]. Its enzymatic activity is regarded as a reliable biomarker of the hair-inductive potential of HFDPCs, as higher ALP expression typically reflects enhanced folliculogenic capability [37]. This is particularly evident during the anagen phase, where DPCs exhibit elevated ALP levels in parallel with increased proliferation and differentiation cues within the follicular microenvironment [38]. HFDPCs play a crucial role in transitioning hair follicles from the catagen phase to the anagen phase. 5 μg/mL biotin treatment significantly enhanced ALP expression compared with the H2O2-damaged HFDPC group. Similarly, treatment with 0.01% 3-HP also led to a notable upregulation of ALP expression (Figure 3A,B).

Figure 3.

The effects of 3-HP on the ALP activity in H2O2-damaged HFDPCs. (A) HFDPCs exposed to oxidative stress by H2O2 were pretreated with 5 μg/mL biotin or 0.005-0.01% 3-HP, then incubated with ALP staining solution for 18 h. (B) The quantitative analysis of ALP activity in each group was shown. Statistical significance was determined using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s post hoc test. Data were representative of three independent experiments. ## p < 0.01 vs. control group, * p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001 vs. H2O2-treated group. Scale bar: 20 µm.

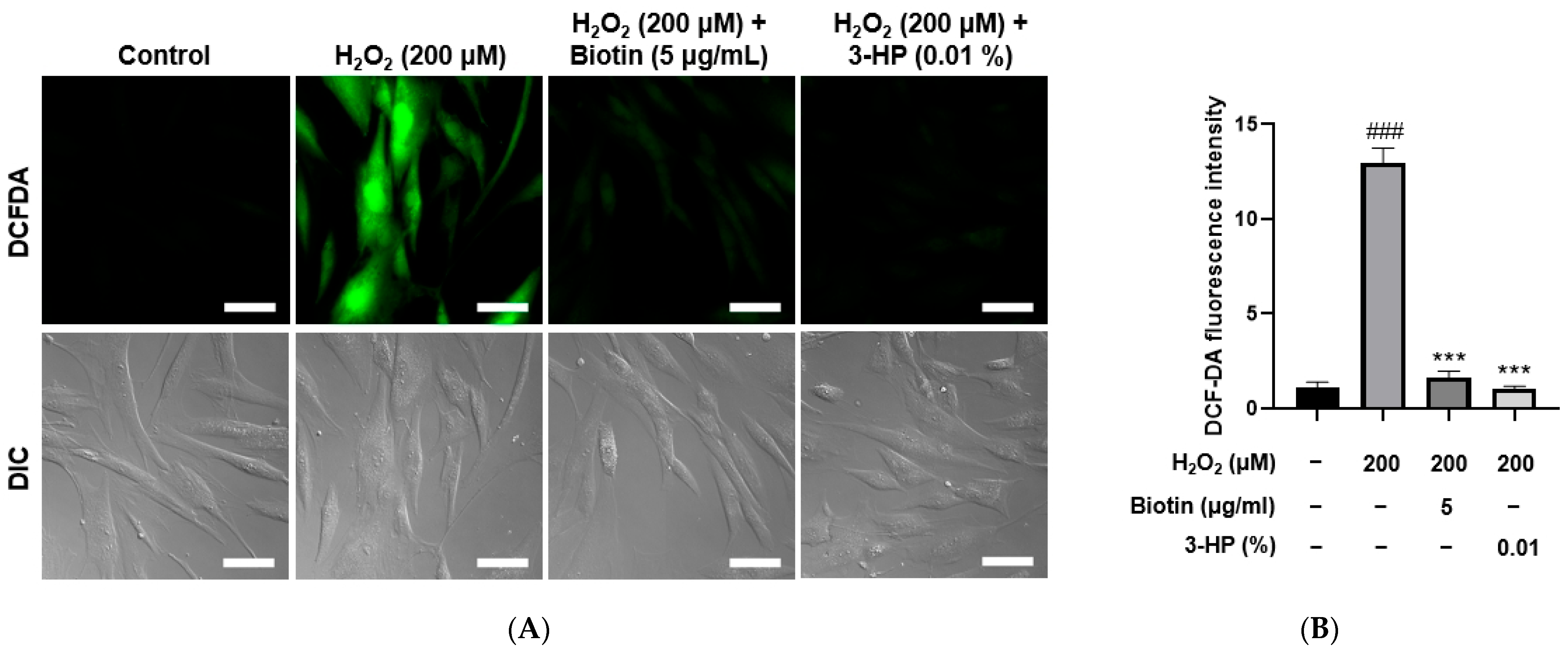

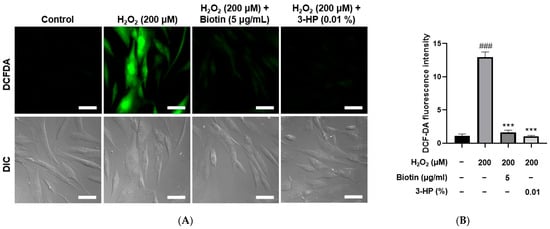

2.4. 3-HP Reduced ROS Levels in H2O2-Damaged HFDPCs

Excessive accumulation of ROS is known to induce oxidative stress, which can impair the functional capacity of dermal papilla cells to support and promote hair growth [39]. Using the DCF-DA assay, intracellular ROS generation was stimulated by treatment with 200 μM H2O2. As expected, the ROS levels in the positive control groups treated with 5 μg/mL biotin were significantly reduced compared with the H2O2-treated group. Similarly, cells treated with 0.01% 3-HP also exhibited a marked decrease in ROS levels (Figure 4A,B). Fluorescence quantification showed that 3-HP markedly reduced DCF-DA-derived fluorescence compared with the H2O2-treated group, meaning that 3-HP effectively diminished intracellular ROS accumulation in oxidatively stressed HFDPCs. These results suggest that 3-HP exerted a protective effect by attenuating H2O2-induced oxidative burden within the cells.

Figure 4.

The effect of 3-HP on intracellular ROS reduction in H2O2-damaged HFDPCs. (A) Representative fluorescence images of intracellular ROS in HFDPCs treated with 200 μM H2O2, followed by pretreatment with 5 μg/mL biotin, 100 μg/mL, and 0.01% 3-HP. ROS levels were visualized as green using the fluorescent probe DCF-DA assay. (B) The quantitative analysis of fluorescence intensity in each group was shown. Data were presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. ### p < 0.001 vs. control group; *** p < 0.001 vs. H2O2-treated group. Scale bar: 50 μm.

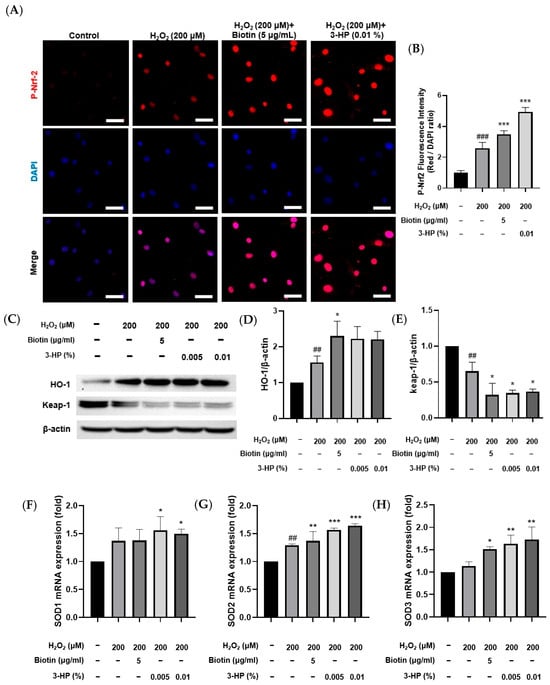

2.5. 3-HP Activated the Nrf2 Pathway in H2O2-Damaged HFDPCs

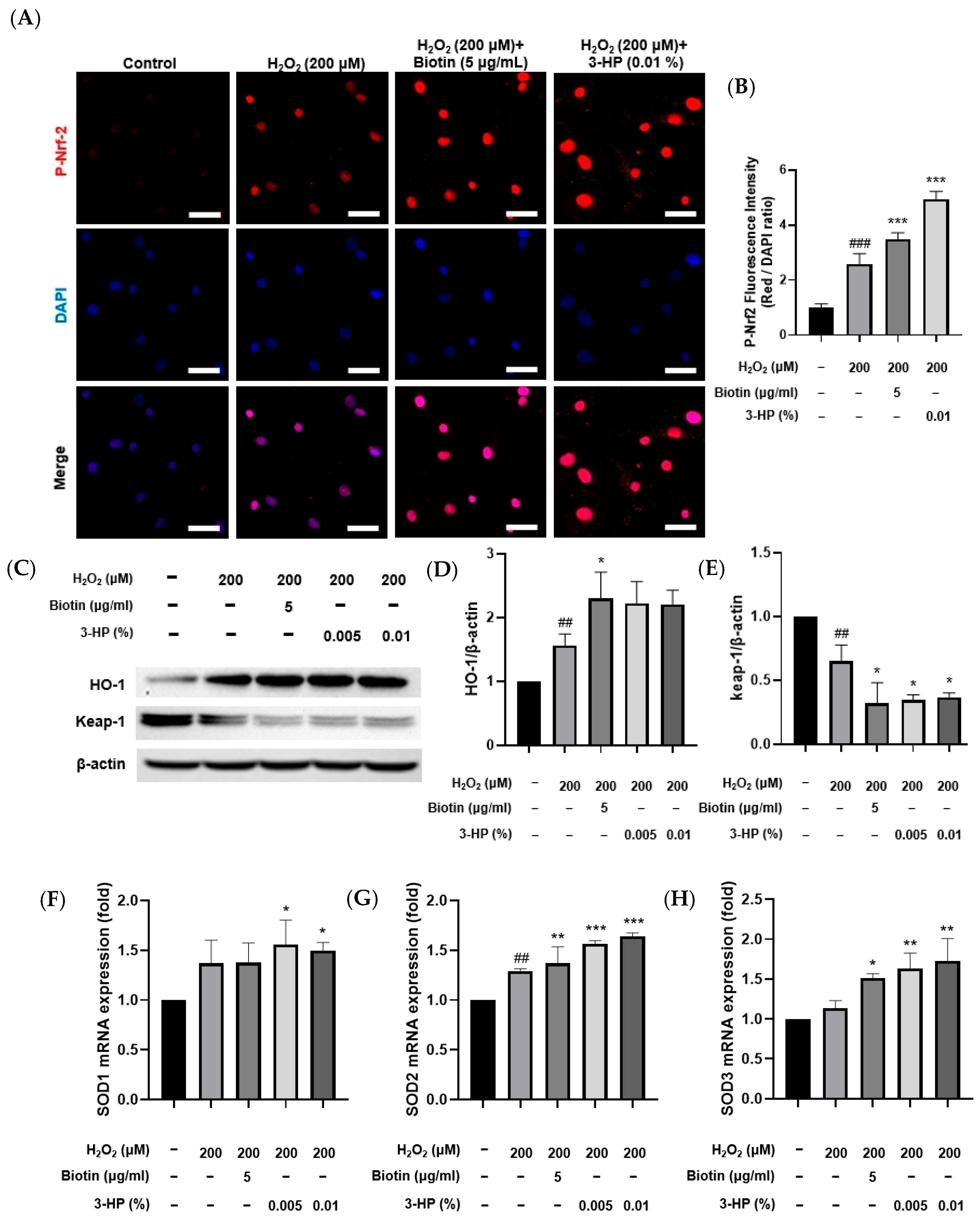

In response to elevated oxidative stress, Nrf2 activation initiates the transcriptional upregulation of antioxidant enzymes, which in turn mitigate oxidative stress–induced cellular injury [40,41,42]. Consistent with this mechanism, treatment with 3-HP markedly increased p-Nrf2 levels compared with the H2O2-treated group, indicating that 3-HP enhanced the cellular antioxidant response by promoting Nrf2 signaling (Figure 5A,B). To further investigate antioxidant regulation at the protein level, HO-1 and Keap-1 expression were first analyzed by Western blot analysis. HO-1 protein abundance increased following H2O2 exposure relative to the control group, reflecting an adaptive cytoprotective response to oxidative stress. Pretreatment with 3-HP led to a more pronounced elevation in HO-1 expression, indicating that 3-HP strengthened the Nrf2-mediated antioxidant response during oxidative stress (Figure 5C,D). In contrast, Keap-1 showed the highest abundance under basal conditions, reflecting its role as the primary suppressor that maintained Nrf2 in an inactive state during homeostasis [43]. Exposure to H2O2 reduced Keap-1 protein levels, likely through oxidative modification of its cysteine residues and subsequent protein destabilization [44]. This decline became even more pronounced when cells were pretreated with 3-HP, suggesting that 3-HP further destabilized Keap-1, thereby enabling more sustained Nrf2 activation under oxidative stress conditions (Figure 5E). To assess transcriptional regulation, mRNA expression of SOD isoforms was measured. Cells pretreated with 3-HP showed significant upregulation of all SOD isoforms, indicating that 3-HP strengthens the antioxidant defense through enhanced mitochondrial ROS clearance and Nrf2-dependent transcription (Figure 5F–H). These data demonstrated that 3-HP reinforces multiple levels of the Nrf2 antioxidant defense system by promoting Nrf2 phosphorylation, upregulating antioxidant enzymes, enhancing HO-1 induction, and reducing Keap-1 expression, thereby mitigating oxidative stress-induced dysfunction in HFDPCs.

Figure 5.

The effect of 3-HP on Nrf2 activation and antioxidant defense regulation in H2O2-damaged HFDPCs. (A) Representative mmunofluorescence images showing p-Nrf2 localization (red) in HFDPCs treated with H2O2 with or without biotin or 3-HP; nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). (B) Quantification of p-Nrf2/DAPI fluorescence intensity. (C–E) Western blot and densitometric analysis of HO-1 and Keap-1 protein levels following H2O2 and 3-HP treatment. (F–H) Relative mRNA levels of SOD1, SOD2, and SOD3 measured by qRT-PCR under oxidative stress conditions. Data were expressed as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. ## p < 0.01, ### p < 0.001 vs. control group; * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001 vs. H2O2-treated group. Scale bar: 50 μm.

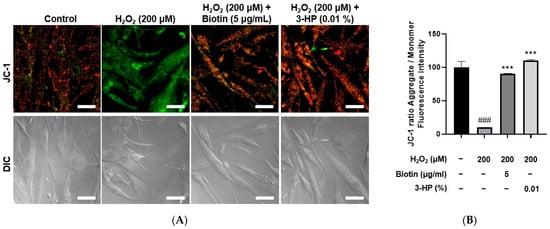

2.6. 3-HP Enhanced Mitochondrial Function in H2O2-Damaged HFDPCs

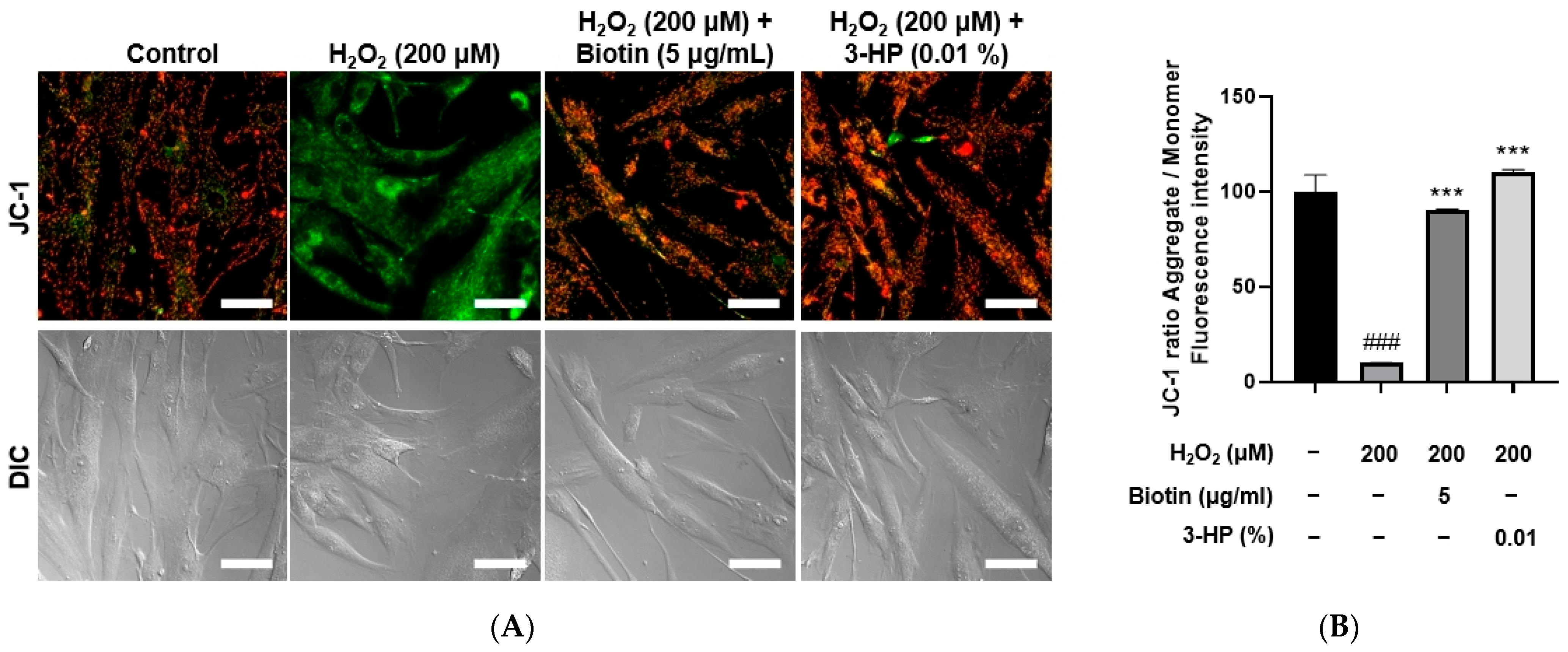

Mitochondrial activity is essential for controlling hair follicle development [45]. It is well established that the activation of mitochondrial respiration and ATP production contributes to the promotion of hair growth [46,47]. The mitochondrial membrane potential serves as an important measure of both mitochondrial performance and overall cellular health. JC-1 staining is a widely utilized method to assess ΔΨm, where healthy mitochondria with intact membrane potential show red fluorescence (JC-1 aggregates), whereas depolarized mitochondria exhibit green fluorescence (JC-1 monomers) [48]. Thus, the red/green fluorescence ratio serves as a reliable measure of mitochondrial integrity and bioenergetic status [49]. Intracellular ATP levels are a direct measure of mitochondrial bioenergetic function and overall cellular viability [50,51]. A reduction in ATP production is indicative of mitochondrial impairment, while maintenance of ATP levels reflects preserved mitochondrial function [52].

To evaluate the effects of 3-HP on mitochondrial function under oxidative stress conditions, HFDPCs were treated with 200 μM H2O2, and mitochondrial membrane potential and ATP production were assessed using JC-1 and Live Cell ATP assays, respectively. H2O2 treatment significantly disrupted mitochondrial membrane potential, as indicated by a decreased red-to-green fluorescence ratio in the JC-1 assay. However, pretreatment with 0.01% 3-HP markedly restored the membrane potential, comparable to the effects observed with 5 μg/mL biotin (Figure 6A,B). Similarly, ATP levels were significantly reduced in the H2O2-treated group, whereas both the 3-HP and positive control groups showed a substantial recovery in intracellular ATP production (Supplementary Figure S1). These results indicated that 3-HP alleviated H2O2-induced mitochondrial dysfunction and supported mitochondrial bioenergetics in HFDPCs. To further substantiate the restorative effects of 3-HP on mitochondrial activity, mitochondrial ROS production was quantified using MitoSOX Red fluorescence. H2O2 exposure led to a pronounced elevation in mitochondrial superoxide levels, confirming oxidative injury within the organelle. However, pre-treated cells with 0.01% 3-HP exhibited a significant reduction in MitoSOX fluorescence intensity, comparable to that observed in the biotin group (Supplementary Figure S2). These data demonstrated that 3-HP not only stabilized mitochondrial membrane potential and preserved ATP synthesis, but also effectively suppressed excessive mitochondrial ROS generation.

Figure 6.

The influences of 3-HP on mitochondrial membrane potential in H2O2-damaged HFDPCs. (A) Representative JC-1 fluorescence images showing mitochondrial membrane potential in HFDPCs treated with H2O2 alone, or pretreated with 5 μg/mL biotin, 100 μg/mL, and 0.01% 3-HP. High mitochondrial membrane potential is represented by red fluorescence, whereas depolarized mitochondria are visualized as green fluorescence. (B) The quantitative analysis of red/green fluorescence ratios in each group was shown. Data were presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. ### p < 0.001 vs. control group; *** p < 0.001 vs. H2O2-treated group. Scale bar: 50 μm.

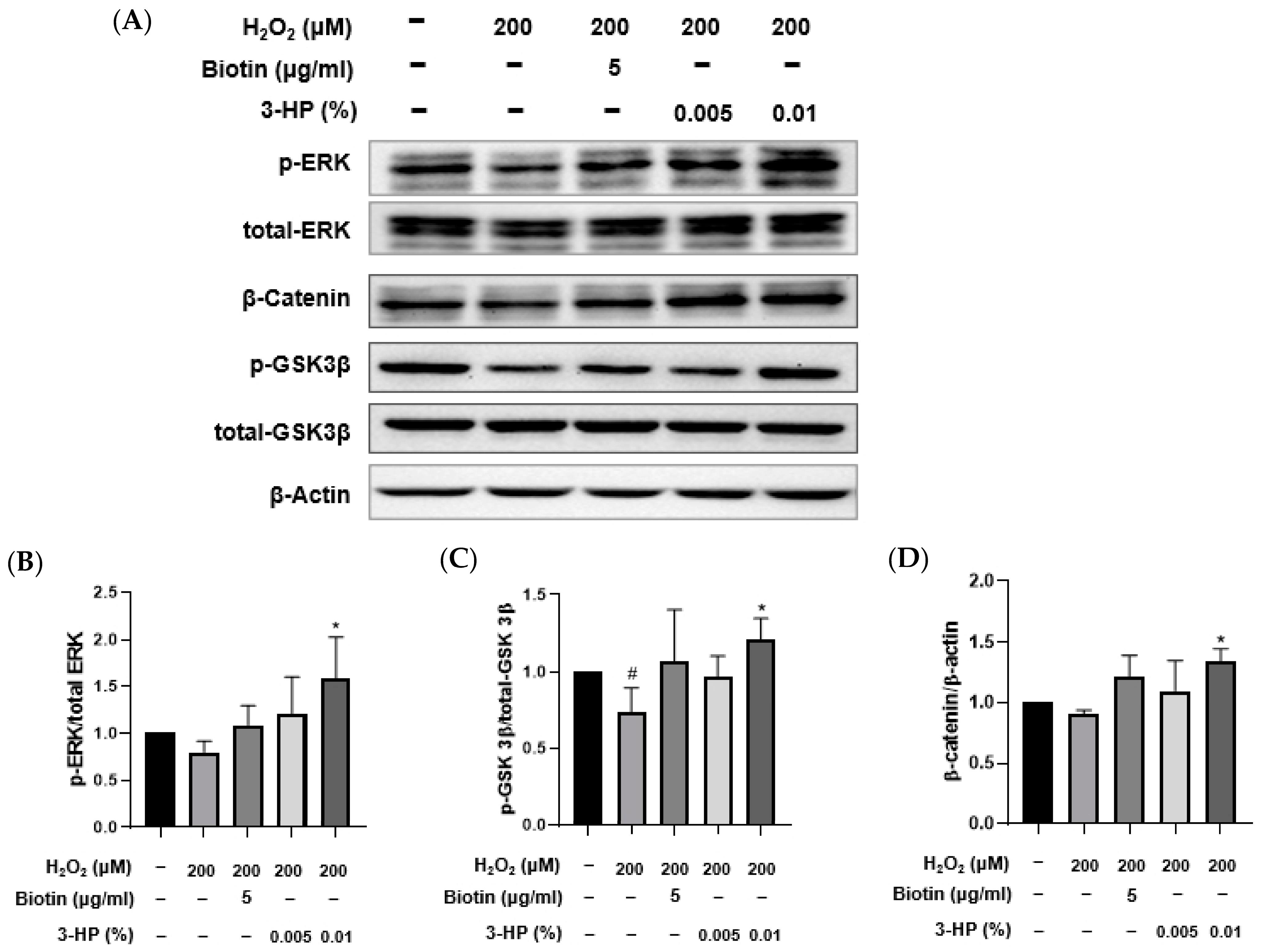

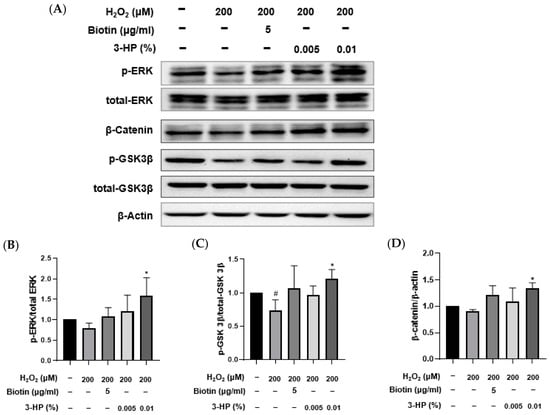

2.7. 3-HP Enhanced Hair Growth-Related Signaling Pathways in H2O2-Damaged HFDPCs

As a major element of the MAPK cascade, the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) pathway is essential for regulating cellular growth, differentiation, and viability [53,54]. Activation of this pathway is closely associated with the promotion of the anagen phase and the overall regeneration of hair follicles [55,56]. Glycogen synthase kinase 3 beta (GSK-3β) is a serine/threonine kinase involved in various cellular signaling pathways, including the Wnt/β-catenin pathway [57,58]. By inhibiting β-catenin breakdown, GSK-3β facilitates its cytoplasmic build-up and nuclear entry, thereby triggering Wnt target genes involved in cellular proliferation and survival [59,60]. As a key downstream component of Wnt signaling, β-catenin, upon nuclear accumulation, partners with TCF/LEF factors to modulate gene expression related to cellular growth and tissue maintenance [61,62]. In the context of hair biology, nuclear β-catenin accumulation is critical for hair follicle morphogenesis and the maintenance of the anagen phase [63,64]. These pathways are integral to hair growth and anagen phase maintenance.

To investigate the molecular mechanisms by which 3-HP exerts protective and pro-regenerative effects in HFDPCs under oxidative stress, the activation of ERK and GSK3β signaling, as well as β-catenin accumulation, was assessed by Western blot analysis (Figure 6A). Consistent with oxidative stress effects, H2O2 exposure led to a significant decrease in ERK and GSK3β phosphorylation and reduced β-catenin levels relative to control. Pretreatment with 3-HP, however, restored phosphorylation of ERK and GSK3β (Figure 7B,C) and markedly elevated β-catenin expression compared with the H2O2 group, suggesting enhanced activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling (Figure 7D). These effects were comparable to those observed with biotin treatment, a known hair growth-promoting agent. These findings indicated that 3-HP modulated key signaling pathways involved in hair follicle regeneration in oxidative stress-damaged HFDPCs.

Figure 7.

The effect of 3-HP on the expression of hair growth-related signaling proteins in H2O2-damaged HFDPCs. (A) Representative images of HFDPCs showing the expression of phosphorylated ERK (p-ERK), total ERK, phosphorylated GSK3β (p-GSK3β), total GSK3β, β-catenin, and β-actin. Cells were pretreated with 5 μg/mL biotin or 0.01% 3-HP, followed by exposure to 200 μM H2O2. (B–D) The quantitative analysis of each group was shown. Data were presented as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. # p < 0.05 vs. control group; * p < 0.05 vs. H2O2-treated group.

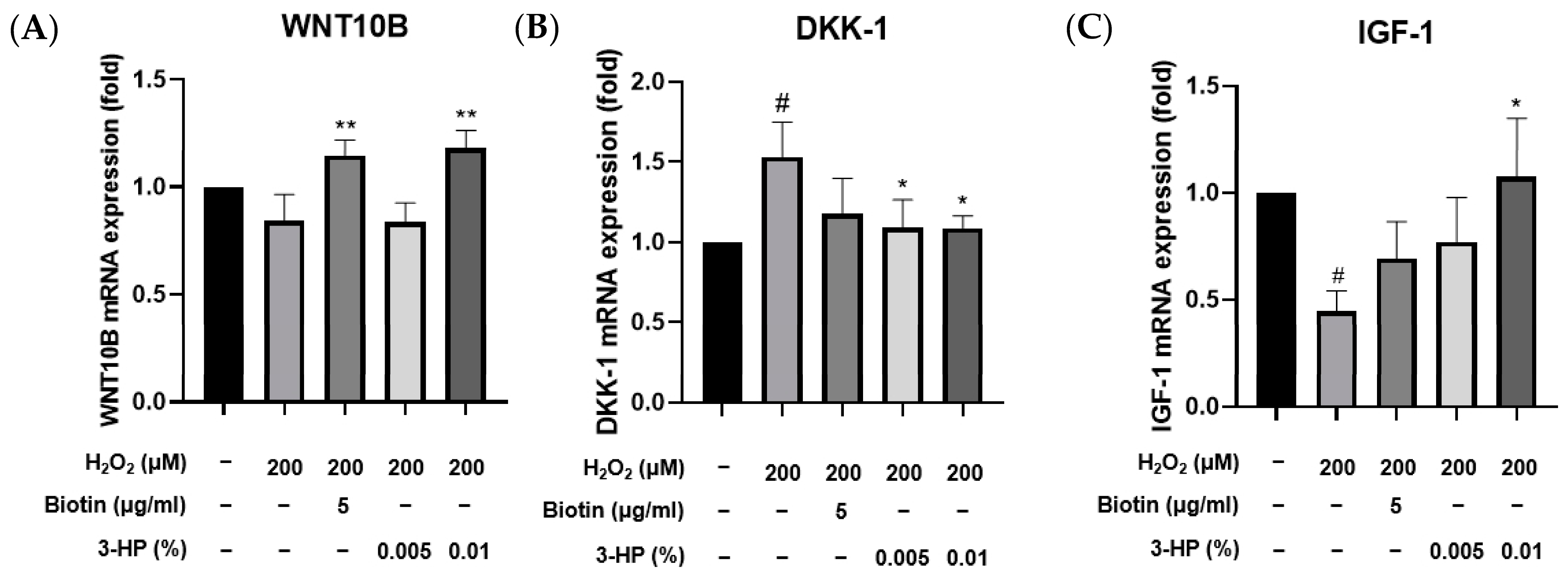

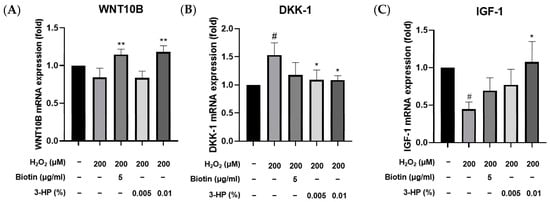

2.8. 3-HP Enhanced the Expression of Hair Growth-Related Genes in H2O2-Damaged HFDPCs

DKK-1 negatively regulates the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, promoting hair follicle regression from the anagen phase to the catagen phase, which limits hair proliferation [65] In contrast, insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) and WNT10B act as positive regulators of hair follicle development by enhancing follicular proliferation and promoting the telogen-to-anagen transition, respectively, with IGF-1 prolonging the anagen phase and WNT10B activating the canonical Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway [66,67]. DKK-1 is a known antagonist of the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway [68]. Elevated levels of DKK-1 have been implicated in the regression of hair follicles and the promotion of the catagen phase, leading to hair loss [69,70]. IGF-1 is a growth factor that promotes cell proliferation and survival [71]. In the context of hair biology, IGF-1 has been shown to stimulate the proliferation of dermal papilla cells and promote hair follicle development [72]. WNT10B is a member of the Wnt family of proteins and plays a crucial role in activating the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway, which is essential for hair follicle development and regeneration [73]. Under oxidative stress conditions in HFDPCs, altering the expression of these genes may substantially impact hair follicle regeneration. To examine the transcriptional levels of 3-HP on oxidative stress-induced damage in HFDPCs, we examined the mRNA expression levels of key hair growth-related genes, including DKK-1, IGF-1, and WNT10B, using quantitative real-time PCR.

Treatment with 3-HP notably suppressed the expression of DKK-1, a gene commonly upregulated in response to oxidative damage (Figure 8B). Conversely, the mRNA expression levels of IGF-1 and WNT10B, which are known to promote hair follicle development and anagen phase induction [74], were markedly increased following treatment with 0.01% 3-HP (Figure 8A,C). These findings indicate that 3-HP effectively regulates the expression of genes associated with follicular regeneration and may counteract the inhibitory effects of oxidative stress on hair growth.

Figure 8.

Effects of 3-HP on mRNA expression of hair growth genes in H2O2-challenged HFDPCs. Pretreatment was performed with 5 μg/mL biotin or 0.01% 3-HP for 24 h, followed by 2 h of 200 μM H2O2. Gene expression of (A) DKK-1, (B) IGF-1, and (C) WNT10B was assessed using qRT-PCR. The results were normalized to β-actin expression and are presented as fold changes relative to the H2O2-treated group. Data were expressed as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. # p < 0.05 vs. control group; * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, compared with H2O2-treated group.

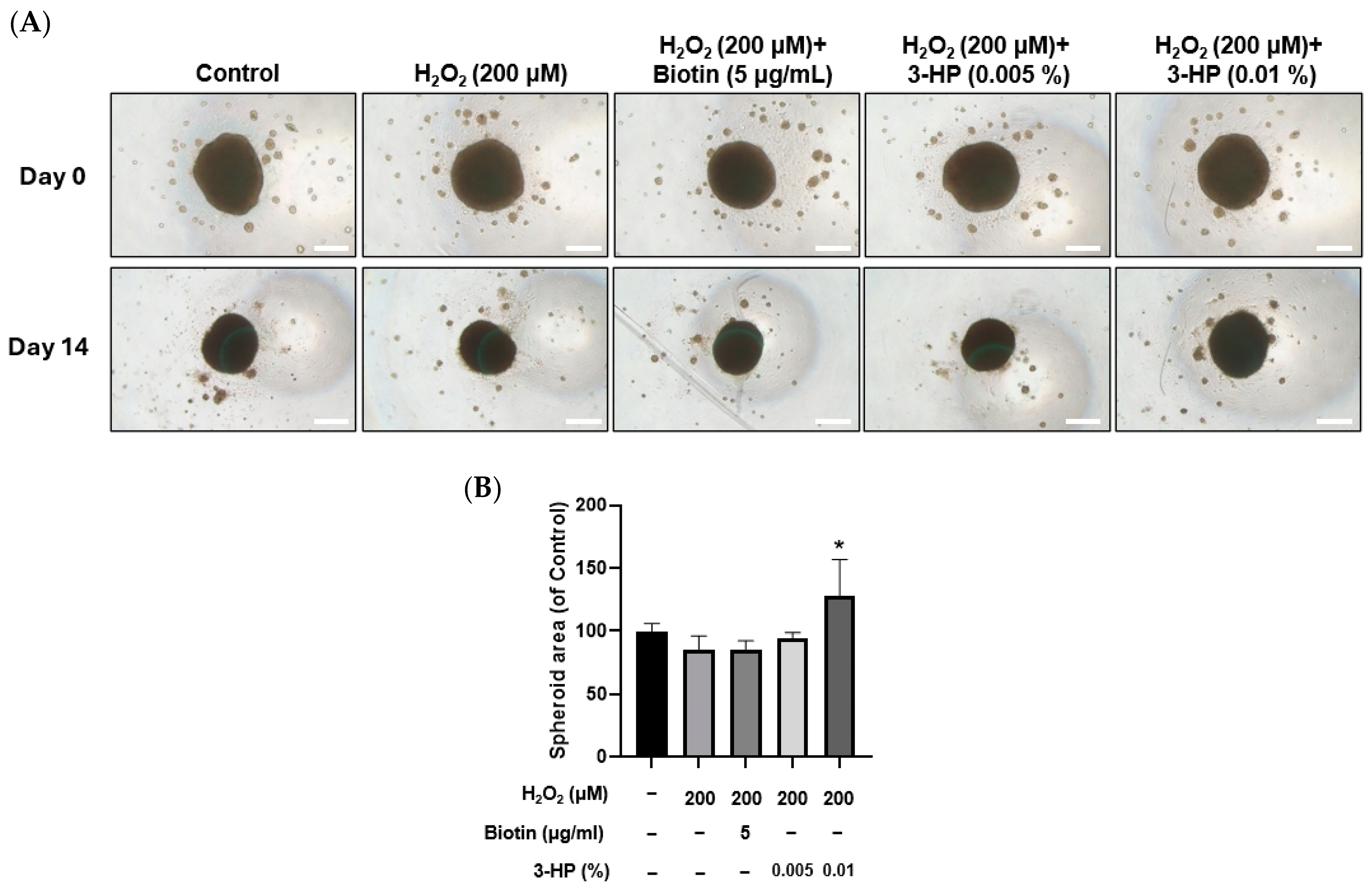

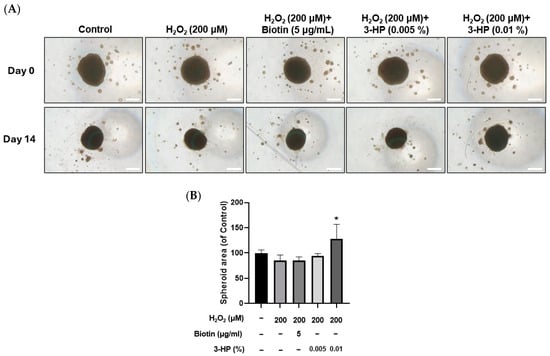

2.9. 3-HP Enhanced the Size of 3D Spheroids Formed by H2O2-Treated HFDPCs

Spheroid culture of dermal papilla cells has been reported to better preserve their gene expression patterns and hair-inductive capabilities, offering a more physiologically relevant in vitro model for evaluating dermal papilla function [75].

In this system, reductions in spheroid size are closely linked to impaired cell viability, indicating that spheroid diameter or area is a meaningful indicator of functional status [76]. In H2O2-treated HFDPCs, pretreatment with 3-HP markedly increased the diameter and area of 3D spheroids compared with the H2O2-treated group (Figure 9A,B). Since three-dimensional spheroids of dermal papilla cells retain essential hair-inductive gene expression and even possess the ability to trigger follicle neogenesis [77,78], the enlargement of spheroids by 3-HP indicates a functional restoration of DP inductivity under oxidative stress conditions.

Figure 9.

Effects of 3-HP on 3D spheroid formation in H2O2-damaged HFDPCs. (A) Representative images of HFDPCs spheroids at Day 0 and Day 14 following treatment with 200 µM H2O2, with or without pretreatment with 5 µg/mL biotin or 3-HP (0.005% or 0.01%). Scale bar = 200 µm. (B) The quantitative analysis of the spheroid area was shown. Data were expressed as mean ± SD (n = 3). * p < 0.05 vs. H2O2-treated group.

3. Discussion

Previous research has highlighted the essential role of HFDPCs in initiating and maintaining the anagen phase of the hair cycle through the secretion of growth factors and extracellular matrix components [79,80].

In this study, we demonstrated that 3-HP effectively promoted hair growth-related functions in HFDPCs, particularly under oxidative stress conditions induced by H2O2. These findings provide valuable insights into the potential application of 3-HP as a therapeutic agent for hair loss treatment. Importantly, we observed that 3-HP significantly increased the expression of ALP, a well-established marker of dermal papilla cell inductivity (Figure 3). Moreover, 3-HP reduced intracellular ROS accumulation, which is known to impair the function and viability of HFDPCs, thereby protecting the cells from H2O2-induced oxidative damage. In parallel, 3-HP treatment enhanced the nuclear translocation of Nrf2, indicating that its protective effect is mediated through activation of the Nrf2-mediated antioxidant pathway (Figure 4). Mitochondrial integrity plays a critical role in maintaining the bioenergetic capacity of HFDPCs [81]. Mitochondrial membrane potential was evaluated using the JC-1 assay. In polarized, healthy mitochondria, JC-1 accumulates and forms aggregates that emit red fluorescence, whereas in depolarized mitochondria with reduced membrane potential, JC-1 remains monomeric and emits green fluorescence [82]. The ratio of red to green fluorescence thus serves as a reliable measure of mitochondrial integrity. Furthermore, the intracellular ATP level was measured using the ATP assay to evaluate the bioenergetic function of mitochondria [83].

This suggests that 3-HP may exert its protective effects by sustaining mitochondrial function, which in turn supports cellular activities essential for hair follicle regeneration (Figure 6). Western blot analysis further revealed that 3-HP induced the activation of ERK and GSK3β/β-catenin signaling pathways, both of which are pivotal in regulating proliferation and differentiation in HFDPCs (Figure 7). While the AKT pathway is recognized for its role in supporting cell survival and hair follicle inductivity, no significant changes in AKT activation, assessed via p-AKT/AKT levels, were detected under our experimental conditions. This discrepancy warrants further investigation to elucidate whether 3-HP modulates AKT signaling under different temporal or dosage parameters. The ERK signaling pathway is essential for regulating survival, cell proliferation, and migration, processes that are critical for initiating and maintaining the anagen phase of the hair cycle [84,85]. Activation of ERK signaling in HFDPCs has been shown to enhance the secretion of key growth factors such as VEGF and IGF-1, thereby stimulating hair shaft elongation [86].

Meanwhile, GSK3β/β-catenin signaling is crucial for the development and regenerative processes of hair follicles [87]. Inhibiting GSK3β through phosphorylation allows β-catenin to build up in the cytoplasm and move into the nucleus, where it stimulates Wnt target genes to support HFDPC inductivity, follicular growth, and stem cell activation [88,89]. Therefore, the upregulation of these pathways by 3-HP means a strong potential to enhance the biological functionality of HFDPCs and promote hair regeneration. 3-HP treatment increased p-GSK3β and nuclear β-catenin expression, suggesting an association with Wnt/β-catenin pathway activation. However, direct activation remains to be verified using pathway inhibitors or reporter assays in future studies. Additionally, 3-HP treatment enhanced IGF-1 and WNT10B expression while reducing levels of DKK-1, a negative regulator of Wnt signaling (Figure 8). These findings indicate that 3-HP not only protects HFDPCs from oxidative stress but also promotes a gene expression profile conducive to hair regeneration [90]. Under oxidative stress conditions, 3-HP treatment resulted in enlarged HFDPC spheroids (Figure 9), indicating a partial restoration of dermal papilla inductive potential. Although spheroid size alone cannot fully confirm folliculogenic capacity, these results indicate that 3-HP may help maintain the 3D organization and functional activity of dermal papilla cells essential for hair inductivity [91,92].

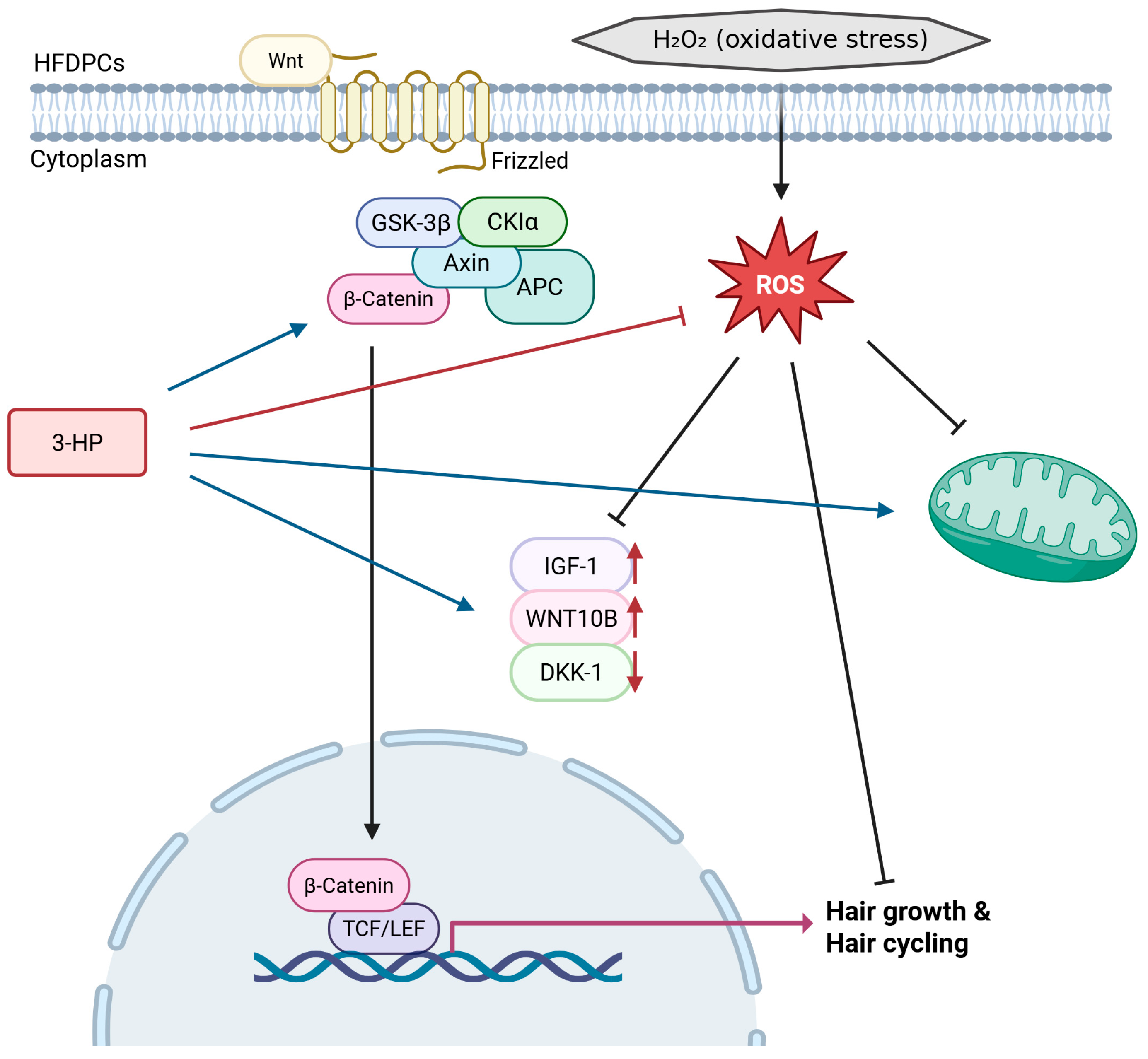

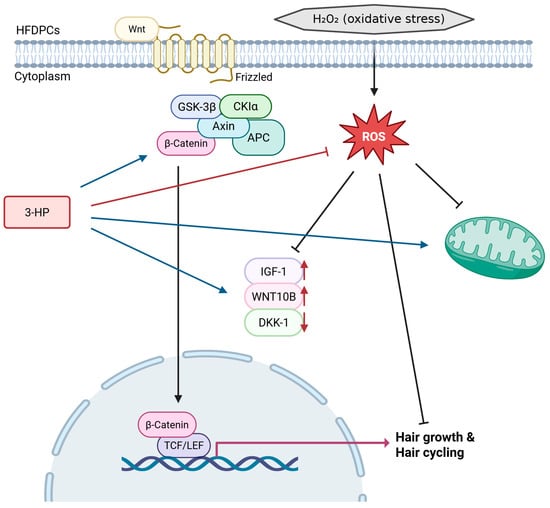

Taken together, our results emphasize the regenerative relevance of 3-HP in promoting hair follicle regeneration through modulation of the dermal papilla microenvironment (Figure 10). This activity supports its potential application as an active ingredient in topical formulations, cosmeceuticals, and pharmacological strategies for alopecia management. However, further studies using in vivo models and well-controlled clinical trials are essential to clarify the clinical relevance and safety profile of 3-HP. Such investigations will help confirm its efficacy, optimize its formulation, and potentially pave the way for its translation into dermatological therapeutics for treating various forms of hair loss, including stress-induced alopecia [93,94].

Figure 10.

Schematic representation of the proposed mechanism through which 3-HP alleviates H2O2-induced oxidative stress and stimulates Wnt/β-catenin signaling to enhance hair growth and regulate hair cycling. (created with BioRender, https://www.biorender.com/ accessed on 31 December 2025).

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Chemicals and Reagents

The 3-HP was supplied by LG Chem (Seoul, Republic of Korea). It was produced via microbial fermentation using a genetically engineered strain of Escherichia coli, with glycerol as the carbon source. 3-HP was produced in salt form via fermentation at neutral pH. Biomass was removed by microfiltration, and the 3-HP salt was recovered through crystallization. It was then converted into its acid form via acidification. Finally, 3-HP was concentrated and recovered as a 70% aqueous solution with a purity of 99.5%. Biotin at a concentration of 5 μg/mL served as a positive control because it is a well-established micronutrient known to support hair follicle function [95,96]. Biotin supports keratin structure and has been widely applied as a reference micronutrient in in vitro studies assessing dermal papilla cell function and hair-growth-related responses [97,98].

4.2. Cell Culture

HFDPCs sourced from PromoCell (Heidelberg, Germany) were maintained in follicle dermal papilla cell growth medium containing a supplement mix and 1% penicillin–streptomycin at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. Ready-to-use HFDPC Medium and a Detach Kit from the same supplier were used for cell handling. The Detach Kit included Trypsin/EDTA Solution, Trypsin Neutralization Solution, and HEPES BSS Solution.

4.3. Cell Viability Assay

HFDPC viability was measured using the EZ-CytoX assay (DoGenBio, Seoul, Republic of Korea), with cells seeded at 2 × 104 cells per well in 96-well plates and treated with various concentrations of 3-hydroxypropionic acid (3-HP; 0.001–0.01%) for 24 h. Following treatment, EZ-Cytox solution was added to each well and incubated for 2 h at 37 °C. Absorbance was measured using a BioTek Multi-Mode Microplate Reader (Winooski, VT, USA), and cell viability was calculated as described below:

where and represent the optical density values of the treated and untreated (control) groups, respectively.

Cell viability (%) = (ODtreated/ODcontrol) × 100

4.4. Wound Healing Assay

Confluent HFDPC monolayers (>90%) in 6-well plates were scratched at the center of each well using a 200 µL pipette tip. The time of scratching was set as 0 h. The cells were treated with 200 µM H2O2, 5 µg/mL biotin, and 0.005–0.01% 3-HP. Phase-contrast images were captured after 24 h using an ECLIPSE Ts2 microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) for both treated and control groups.

4.5. Alkaline Phosphatase Staining (ALP) Assay

Alkaline Phosphatase Staining was assessed by an Alkaline Phosphatase Staining Kit (Abcam, Cambridge, UK). HFDPCs were seeded in a 24-well plate. HFDPCs were treated with 200 µM H2O2, 5 µg/mL biotin, and 0.01% 3-HP. A total of 0.4 mL of fixing solution was added to each well, followed by a 5 min incubation. The wells were then washed twice with 1× PBST. After AP staining (0.4 mL per well, 6 h, dark), images were captured using an ECLIPSE Ts2 microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) and analyzed with Fiji ImageJ software, version 1.53e (Windows 64-bit; NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA).

4.6. Measurement of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)

ROS generation within HFDPCs was assessed with an H2DCFDA-based fluorescence assay (Abcam, Cambridge, UK). Cells seeded on confocal dishes were cultured for 24 h and subsequently treated with 200 µM H2O2 in the presence or absence of 5 µg/mL biotin or 0.01% 3-HP. After DCF-DA loading (10 µM, 15 min, dark), fluorescence images were acquired with a Nikon Eclipse Ti2 microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

4.7. Immunofluorescence Analysis

HFDPCs were plated in confocal dishes at a density of 5.0 × 104 cells per well and cultured. The cells were subsequently exposed to 5 µg/mL biotin, 0.01% 3-HP. Immunofluorescence staining was performed following fixation, permeabilization, and blocking, with p-Nrf2 detected using a primary antibody at 4 °C overnight and an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody at 37 °C. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI, and images were acquired using a Nikon Eclipse Ti2 microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

4.8. Measurement of Mitochondrial Membrane Potential (JC-1)

Mitochondrial membrane potential in HFDPCs was analyzed with the JC-1 Assay Kit (Abcam, Cambridge, UK). Cells seeded on confocal dishes were cultured for 24 h before treatment with 200 µM H2O2, 5 µg/mL biotin, or 0.01% 3-HP. Cells were washed with fresh culture medium and stained with 10 µM JC-1 dye. The cells were then incubated for 20 min, protected from light at 37 °C. Changes in mitochondrial membrane potential were quantified as the red-to-green fluorescence ratio of JC-1 aggregates and monomers, respectively, acquired with a Nikon Eclipse Ti2 fluorescence microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

4.9. Measurement of Mitochondrial ATP Content and Mitochondrial ROS

Cellular ATP levels and mitochondrial ROS in live HFDPCs were independently assessed using a luminescence-based Cell MeterTM ATP assay (AAT Bioquest, Pleasanton, CA, USA), and the MitoSOXTM Red mitochondrial superoxide indicator (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), respectively. In each experiment, MitoLiteTM Green FM (AAT Bioquest, Pleasanton, CA, USA) was applied concurrently to visualize mitochondria and confirm cell viability and localization. Cells seeded in confocal dishes were maintained for 24 h before measurement. Following treatment with 200 µM H2O2, 5 µg/mL biotin, and 0.01% 3-HP, the culture medium was removed and replaced with the ATP assay working solution or the MitoSOXTM staining solution, each containing MitoLiteTM Green FM, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. After incubation at 37 °C for 30 min in the dark, the cells were washed with DPBS. Fluorescence images were obtained using a Nikon Eclipse Ti2 microscope (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan).

4.10. Western Blot Analysis

HFDPCs were incubated with the indicated samples for 24 h and subsequently challenged with 200 μM H2O2 for 2 h. Cells were rinsed with PBS and lysed in RIPA buffer, and total protein content was quantified using a BCA assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Equivalent protein amounts (20 μg) were resolved by SDS–PAGE and electrotransferred onto PVDF membranes. Non-specific binding was suppressed by blocking membranes with 5% non-fat milk in TBS-T for 2 h at room temperature. Primary antibodies against p-ERK, ERK, and β-actin (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), as well as β-catenin, p-GSK3β, and GSK3β (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Carlsbad, CA, USA), were applied overnight at 4 °C. Membranes were then incubated with HRP-linked secondary antibodies for 2 h at room temperature. Western blot experiments were independently repeated three times. Protein bands were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system and imaged with the iBright 1500 Imaging System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Band intensities were quantified using Fiji ImageJ software (version 1.53e).

4.11. Real-Time Quantitative Reverse Transcriptase-Polymerase Chain Reaction

HFDPCs prepared for qRT-PCR analysis were allowed to attach in 6-well plates (5 × 104 cells/mL) for 24 h, after which oxidative stress was induced using 200 µM H2O2 in the presence or absence of 5 µg/mL biotin or 0.01% 3-HP for an additional 24 h.

Total RNA was then isolated using TRIzol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Total RNA (2 µg) was reverse-transcribed to cDNA using a commercial synthesis kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Gene expression was subsequently analyzed by qRT-PCR employing TaqMan Universal Master Mix II with UNG. The PCR mixture was prepared by combining synthesized cDNA, DEPC-treated water, TaqMan Universal Master Mix II, and gene-specific TaqMan primers at the indicated volumes.

4.12. Statistical Analyses

Results obtained from at least three independent experiments were summarized as mean ± SD. Group comparisons were conducted using one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc correction implemented in GraphPad Prism (version 8.0.1). Assumptions of normality and equal variance were examined before analysis, and p-values below 0.05 were considered significant.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that 3-HP effectively protected human follicle dermal papilla cells from oxidative stress–induced dysfunction. By restoring mitochondrial activity, reducing intracellular oxidative burden, and activating hair growth–related signaling pathways, 3-HP supported the maintenance of dermal papilla cell inductivity under stress conditions. These findings suggest that 3-HP holds promise as a functional cosmetic ingredient for managing oxidative stress–associated hair thinning.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijms27031480/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.Y.J. and D.W.S.; methodology, C.Y.J.; formal analysis, C.Y.J.; resources, S.A.W., Y.L. and W.J.; investigation, C.Y.J. and Y.H.J.; writing—original draft preparation, C.Y.J. and D.W.S.; writing—review and editing, C.Y.J. and D.W.S.; funding acquisition, D.W.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Regional Innovation System & Education(RISE) program through the Chungbuk Regional Innovation System & Education Center, funded by the Ministry of Education (MOE) and the Chungcheongbuk-do, Republic of Korea (2025-RISE-11-003-03).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data from this study are available upon demand from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The scientific illustration was created using BioRender (Toronto, ON, Canada) (https://www.biorender.com/, accessed on 31 December 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests. The study was conducted through a collaborative research and development arrangement with LG Chem and its researchers (Seung A Woo, Yura Lee, and Woochul Jung). While LG Chem supplied chemical materials, it had no role in study design, data interpretation, or decision-making regarding publication. All findings represent independent scientific analysis and academic judgment.

Abbreviations

| HFDPCs | Human Follicle Dermal Papilla Cells |

| H2O2 | Hydrogen peroxide |

| DCFDA | 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| FITC | Fluorescein isothiocyanate |

| RITC | Rhodamine B isothiocyanate |

| JC-1 | 5,5′,6,6′-tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethylbenzimidazolocarbo-cyanine iodide |

| IF | immunofluorescence |

| BCA | bicinchoninic acid |

| ERK | extracellular signal-regulated kinase |

| Nrf2 | nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 |

| GSK3β | Glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta |

| IGF-1 | Insulin-like growth factor 1 |

| DKK-1 | Dickkopf-1 |

| 3-HP | 3-hydroxypropionic acid |

References

- Kim, S.M.; Kang, J.; Yoon, H.; Choi, Y.K.; Go, J.S.; Oh, S.K.; Ahn, M.; Kim, J.; Koh, Y.S.; Hyun, J.W.; et al. HNG, a Humanin Analogue, Promotes Hair Growth by Inhibiting Anagen-to-Catagen Transition. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 4553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, B.Y. Hair-Growth Potential of Ginseng and Its Major Metabolites: A Review on Its Molecular Mechanisms. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 2703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, F.; Li, J.; Zhang, S.; Zeng, X.; Nie, J.; Li, Z. Oxidative stress in hair follicle development and hair growth: Signalling pathways, intervening mechanisms and potential of natural antioxidants. J. Cell Mol. Med. 2024, 28, e18486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, M.; Jiang, M.; Vergnes, L.; Fu, X.; de Barros, S.C.; Doan, N.B.; Huang, W.; Chu, J.; Jiao, J.; Herschman, H.; et al. Stimulation of Hair Growth by Small Molecules that Activate Autophagy. Cell Rep. 2019, 27, 3413–3421.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, C.; Miao, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, X.; Chen, C.; Hu, Z. Collagenase IV plays an important role in regulating hair cycle by inducing VEGF, IGF-1, and TGF-β expression. Drug Des. Devel Ther. 2015, 9, 5373–5383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Lu, Z.; Man, X.; Li, C.; Zhou, J.; Chen, J.; Yang, X.; Wu, X.; Cai, S.; Zheng, M. VEGF upregulates VEGF receptor-2 on human outer root sheath cells and stimulates proliferation through ERK pathway. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2012, 39, 8687–8694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, H.W.; Joo, H.; Jeon, C.Y.; Lee, Y.; Kim, M.; Shin, J.U.; Kim, J.; Kim, S.; Lee, S.; Lim, D.C.; et al. Anti-Hair Loss Effects of the DP2 Antagonist in Human Follicle Dermal Papilla Cells. Cosmetics 2024, 11, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Zhang, J.; Gomez, H.; Murugan, R.; Hong, X.; Xu, D.; Jiang, F.; Peng, Z. Reactive Oxygen Species-Induced Lipid Peroxidation in Apoptosis, Autophagy, and Ferroptosis. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2019, 2019, 5080843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Wang, M.; He, Y.; Liu, F.; Chen, L.; Xiong, X. Cellular Senescence: Ageing and Androgenetic Alopecia. Dermatology 2023, 239, 533–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, A.; Fang, Y.; Ye, L.; Meng, J.; Wang, X.; Chen, J.; Xu, X. Signaling pathways in hair aging. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2023, 11, 1278278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upton, J.H.; Hannen, R.F.; Bahta, A.W.; Farjo, N.; Farjo, B.; Philpott, M.P. Oxidative stress-associated senescence in dermal papilla cells of men with androgenetic alopecia. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2015, 135, 1244–1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertram, C.; Hass, R. Cellular responses to reactive oxygen species-induced DNA damage and aging. Biol. Chem. 2008, 389, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prie, B.E.; Iosif, L.; Tivig, I.; Stoian, I.; Giurcaneanu, C. Oxidative stress in androgenetic alopecia. J. Med. Life 2016, 9, 79–83. [Google Scholar]

- Chew, E.G.Y.; Lim, T.C.; Leong, M.F.; Liu, X.; Sia, Y.Y.; Leong, S.T.; Yan-Jiang, B.; Stoecklin, C.; Borhan, R.; Heilmann-Heimbach, S.; et al. Observations that suggest a contribution of altered dermal papilla mitochondrial function to androgenetic alopecia. Exp. Dermatol. 2022, 31, 906–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngo, V.; Duennwald, M.L. Nrf2 and Oxidative Stress: A General Overview of Mechanisms and Implications in Human Disease. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haslam, I.S.; Jadkauskaite, L.; Szabo, I.L.; Staege, S.; Hesebeck-Brinckmann, J.; Jenkins, G.; Bhogal, R.K.; Lim, F.; Farjo, N.; Farjo, B.; et al. Oxidative Damage Control in a Human (Mini-) Organ: Nrf2 Activation Protects against Oxidative Stress-Induced Hair Growth Inhibition. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2017, 137, 295–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadkauskaite, L.; Coulombe, P.A.; Schafer, M.; Dinkova-Kostova, A.T.; Paus, R.; Haslam, I.S. Oxidative stress management in the hair follicle: Could targeting NRF2 counter age-related hair disorders and beyond? Bioessays 2017, 39, 1700029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Lim, Y.J.; Kim, H.S.; Shin, H.; Kim, J.; Lee, J.N.; Lee, J.H.; Bae, S. Phloroglucinol Enhances Anagen Signaling and Alleviates H2O2-Induced Oxidative Stress in Human Dermal Papilla Cells. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2024, 34, 812–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Huang, Y.; Huang, K.; Chan, C.; Chiu, H.; Tsai, R.; Chan, J.; Lin, S. Stress-induced premature senescence of dermal papilla cells compromises hair follicle epithelial-mesenchymal interaction. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2017, 86, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, L.; Liu, B.; Chen, X.; Chen, H.; Deng, W.; Yang, C.; Ji, B.; Wan, M. Activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling is involved in hair growth-promoting effect of 655-nm red light and LED in in vitro culture model. Lasers Med. Sci. 2018, 33, 637–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, A.; Motavaf, M.; Raza, D.; McLure, A.J.; Osei-Opare, K.D.; Bordone, L.A.; Gru, A.A. Revolutionary Approaches to Hair Regrowth: Follicle Neogenesis, Wnt/ss-Catenin Signaling, and Emerging Therapies. Cells 2025, 14, 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L’Episcopo, F.; Tirolo, C.; Testa, N.; Caniglia, S.; Morale, M.C.; Impagnatiello, F.; Pluchino, S.; Marchetti, B. Aging-induced Nrf2-ARE pathway disruption in the subventricular zone drives neurogenic impairment in parkinsonian mice via PI3K-Wnt/β-catenin dysregulation. J. Neurosci. 2013, 33, 1462–1485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebrahimi, K.B.; Cano, M.; Rhee, J.; Datta, S.; Wang, L.; Handa, J.T. Oxidative Stress Induces an Interactive Decline in Wnt and Nrf2 Signaling in Degenerating Retinal Pigment Epithelium. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2018, 29, 389–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, J.; Krutsenko, Y.; Moghe, A.; Singh, S.; Poddar, M.; Bell, A.; Oertel, M.; Singhi, A.D.; Geller, D.; Chen, X.; et al. Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 and β-Catenin Coactivation in Hepatocellular Cancer: Biological and Therapeutic Implications. Hepatology 2021, 74, 741–759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchetti, B. Nrf2/Wnt resilience orchestrates rejuvenation of glia-neuron dialogue in Parkinson’s disease. Redox Biol. 2020, 36, 101664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chatterjee, S.; Sil, P.C. ROS-Influenced Regulatory Cross-Talk With Wnt Signaling Pathway During Perinatal Development. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9, 889719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, O.; Cha, H.J.; Ahn, K.J.; An, I.; An, S.; Bae, S. Identification of microRNAs involved in growth arrest and cell death in hydrogen peroxide-treated human dermal papilla cells. Mol. Med. Rep. 2014, 10, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Shin, J.Y.; Kim, J.; Kang, N.; Lee, S. Niacinamide Down-Regulates the Expression of DKK-1 and Protects Cells from Oxidative Stress in Cultured Human Dermal Papilla Cells. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2021, 14, 1519–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, J.; Jang, Y.; Sim, J.; Ryu, D.; Cho, E.; Park, D.; Jung, E. Anti-Hair Loss Effect of Veratric Acid on Dermal Papilla Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Park, Y.B.; Moon, S.; Bok, S.H.; Kim, D.; Ha, T.; Jeong, T.; Jeong, K.; Choi, M. Hypocholesterolemic and antioxidant properties of 3-(4-hydroxyl)propanoic acid derivatives in high-cholesterol fed rats. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2007, 170, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, N.; Neuzil-Bunesova, V.; Tejnecky, V.; Ganzle, M.; Schwab, C. 3-Hydroxypropionic acid contributes to the antibacterial activity of glycerol metabolism by the food microbe Limosilactobacillus reuteri. Food Microbiol. 2021, 98, 103720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, T.; Otani, T.; Yamada, R.; Ogino, H. Enhancing 3-hydroxypropionic acid production in Saccharomyces cerevisiae through enzyme localization within mitochondria. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2023, 680, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Seong, K.; Kim, D.S.; Jeong, J.S.; Kim, S.Y.; Lee, S.; Yang, S.Y.; An, B. Minoxidil-loaded hyaluronic acid dissolving microneedles to alleviate hair loss in an alopecia animal model. Acta Biomater. 2022, 143, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Kang, W.; Choi, D.; Son, B.; Park, T. Nonanal Stimulates Growth Factors via Cyclic Adenosine Monophosphate (cAMP) Signaling in Human Hair Follicle Dermal Papilla Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Liu, H.; Wu, X.; Song, Z.; Tang, H.; Gong, M.; Liu, L.; Li, F. Tetrathiomolybdate Decreases the Expression of Alkaline Phosphatase in Dermal Papilla Cells by Increasing Mitochondrial ROS Production. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, W.; Zhen, H.H.; Oro, A.E. Shh maintains dermal papilla identity and hair morphogenesis via a Noggin-Shh regulatory loop. Genes. Dev. 2012, 26, 1235–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Yoon, J.; Shin, S.H.; Zahoor, M.; Kim, H.J.; Park, P.J.; Park, W.; Min, D.S.; Kim, H.; Choi, K. Valproic acid induces hair regeneration in murine model and activates alkaline phosphatase activity in human dermal papilla cells. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e34152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwack, M.H.; Jang, Y.J.; Won, G.H.; Kim, M.K.; Kim, J.C.; Sung, Y.K. Overexpression of alkaline phosphatase improves the hair-inductive capacity of cultured human dermal papilla spheres. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2019, 95, 126–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abreu, C.M.; Reis, R.L.; Marques, A.P. Dermal papilla cells and melanocytes response to physiological oxygen levels depends on their interactions. Cell Prolif. 2021, 54, e13013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Go, M.Y.; Jeon, C.Y.; Shin, J.U.; Kim, M.; Lim, H.W.; Shin, D.W. Pinitol Improves Diabetic Foot Ulcers in Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetes Rats Through Upregulation of Nrf2/HO-1 Signaling. Antioxidants 2024, 14, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, X.; Xiong, X.; Zhu, H.; Chen, R.; Zhang, S.; Chen, G.; Jian, Z. Nrf2 Regulates Oxidative Stress and Its Role in Cerebral Ischemic Stroke. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q. Role of nrf2 in oxidative stress and toxicity. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2013, 53, 401–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellezza, I.; Giambanco, I.; Minelli, A.; Donato, R. Nrf2-Keap1 signaling in oxidative and reductive stress. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Res. 2018, 1865, 721–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Pi, J.; Zhang, Q. Signal amplification in the KEAP1-NRF2-ARE antioxidant response pathway. Redox Biol. 2022, 54, 102389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avci, P.; Gupta, G.K.; Clark, J.; Wikonkal, N.; Hamblin, M.R. Low-level laser (light) therapy (LLLT) for treatment of hair loss. Lasers Surg. Med. 2014, 46, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, K.; Han, D.; Madigan, M.A.; Lohmann, R.; Braverman, E.R. “Cold” X5 Hairlaser used to treat male androgenic alopecia and hair growth: An uncontrolled pilot study. BMC Res. Notes 2014, 7, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, H.; Choi, J.W.; Kim, J.Y.; Shin, J.W.; Lee, S.; Huh, C. Low-level light therapy for androgenetic alopecia: A 24-week, randomized, double-blind, sham device-controlled multicenter trial. Dermatol. Surg. 2013, 39, 1177–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivandzade, F.; Bhalerao, A.; Cucullo, L. Analysis of the Mitochondrial Membrane Potential Using the Cationic JC-1 Dye as a Sensitive Fluorescent Probe. Bio-Protocol 2019, 9, e3128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, G.; Yang, Y.; Xu, C.; Gao, S. A Flow Cytometry-based Assay for Measuring Mitochondrial Membrane Potential in Cardiac Myocytes After Hypoxia/Reoxygenation. J. Vis. Exp. 2018, 137, 57725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salin, K.; Villasevil, E.M.; Auer, S.K.; Anderson, G.J.; Selman, C.; Metcalfe, N.B.; Chinopoulos, C. Simultaneous measurement of mitochondrial respiration and ATP production in tissue homogenates and calculation of effective P/O ratios. Physiol. Rep. 2016, 4, e13007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patergnani, S.; Baldassari, F.; De Marchi, E.; Karkucinska-Wieckowska, A.; Wieckowski, M.R.; Pinton, P. Methods to monitor and compare mitochondrial and glycolytic ATP production. Methods Enzymol. 2014, 542, 313–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luz, A.L.; Lagido, C.; Hirschey, M.D.; Meyer, J.N. In Vivo Determination of Mitochondrial Function Using Luciferase-Expressing Caenorhabditis elegans: Contribution of Oxidative Phosphorylation, Glycolysis, and Fatty Acid Oxidation to Toxicant-Induced Dysfunction. Curr. Protoc. Toxicol. 2016, 69, 25.8.1–25.8.22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.K.; Kang, J.; Hyun, J.W.; Koh, Y.S.; Kang, J.; Hyun, C.; Yoon, K.; Lee, K.S.; Lee, C.M.; Kim, T.Y.; et al. Myristoleic Acid Promotes Anagen Signaling by Autophagy through Activating Wnt/β-Catenin and ERK Pathways in Dermal Papilla Cells. Biomol. Ther. 2021, 29, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, H.; Lin, H.; Huang, M. Lactoferrin promotes hair growth in mice and increases dermal papilla cell proliferation through Erk/Akt and Wnt signaling pathways. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2019, 311, 411–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Woo, J.; Kim, J.; Choi, M.; Shin, H.J.; Kim, Y.; Kim, J.; Shin, D.W. Iris germanica L. Rhizome-Derived Exosomes Ameliorated Dihydrotestosterone-Damaged Human Follicle Dermal Papilla Cells Through the Activation of Wnt/β-Catenin Pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 4070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsai, F.; Li, C.; Wang, L.; Chen, M.; Lee, M.; Lin, Y.; Wang, C. Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase Mediates Ebastine-Induced Human Follicle Dermal Papilla Cell Proliferation. Biomed. Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 6360503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soma, T.; Fujiwara, S.; Shirakata, Y.; Hashimoto, K.; Kishimoto, J. Hair-inducing ability of human dermal papilla cells cultured under Wnt/β-catenin signalling activation. Exp. Dermatol. 2012, 21, 307–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, D.W. The Molecular Mechanism of Natural Products Activating Wnt/β-Catenin Signaling Pathway for Improving Hair Loss. Life 2022, 12, 1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, G.; Jo, K.; Park, Y.; Kawk, H.W.; Yoo, J.; Jang, J.D.; Kang, S.M.; Kim, S.; Kim, Y. Bacillus/Trapa japonica Fruit Extract Ferment Filtrate enhances human hair follicle dermal papilla cell proliferation via the Akt/ERK/GSK-3β signaling pathway. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2019, 19, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ki, G.; Kim, Y.; Lim, H.; Lee, E.; Choi, Y.; Seo, Y. Extremely Low-Frequency Electromagnetic Fields Increase the Expression of Anagen-Related Molecules in Human Dermal Papilla Cells via GSK-3β/ERK/Akt Signaling Pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Liu, Y.; Song, Z.; Hao, F.; Yang, X. Identification of Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway in dermal papilla cells of human scalp hair follicles: TCF4 regulates the proliferation and secretory activity of dermal papilla cell. J. Dermatol. 2014, 41, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, S.B.; Park, H.J.; Lee, B. Hair-Growth-Promoting Effects of the Fish Collagen Peptide in Human Dermal Papilla Cells and C57BL/6 Mice Modulating Wnt/β-Catenin and BMP Signaling Pathways. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 11904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.; Zhu, Y.; Liu, H.; Liu, G.; Li, F. Wnt10b promotes hair follicles growth and dermal papilla cells proliferation via Wnt/β-Catenin signaling pathway in Rex rabbits. Biosci. Rep. 2020, 40, BSR20191248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, N.; Yan, J.; Gu, W.; Yang, Q.; Lin, E.; Lu, S.; Cai, B.; Xia, B.; Liu, X.; Lin, C. Dermal papilla cell-secreted biglycan regulates hair follicle phase transit and regeneration by activating Wnt/β-catenin. Exp. Dermatol. 2024, 33, e14969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.B.; Lee, J.W.; Lee, H.; Lee, K.; Hwang, H.W.; Shin, H.; Byun, J.W.; Shin, J.; Choi, G.S. Dickkopf-related Protein 2 Promotes Hair Growth by Upregulating the Wnt/β-catenin Signaling Pathway in Human Dermal Papilla Cells. Ann. Dermatol. 2024, 36, 292–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, K.; Ye, J.; Lian, X.; Yang, T. Wnt10b promotes growth of hair follicles via a canonical Wnt signalling pathway. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2011, 36, 534–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danek, P.; Kardosova, M.; Janeckova, L.; Karkoulia, E.; Vanickova, K.; Fabisik, M.; Lozano-Asencio, C.; Benoukraf, T.; Tirado-Magallanes, R.; Zhou, Q.; et al. β-Catenin-TCF/LEF signaling promotes steady-state and emergency granulopoiesis via G-CSF receptor upregulation. Blood 2020, 136, 2574–2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwack, M.H.; Kim, M.K.; Kim, J.C.; Sung, Y.K. L-ascorbic acid 2-phosphate represses the dihydrotestosterone-induced dickkopf-1 expression in human balding dermal papilla cells. Exp. Dermatol. 2010, 19, 1110–1112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwack, M.H.; Kim, M.K.; Kim, J.C.; Sung, Y.K. Dickkopf 1 promotes regression of hair follicles. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2012, 132, 1554–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwack, M.H.; Sung, Y.K.; Chung, E.J.; Im, S.U.; Ahn, J.S.; Kim, M.K.; Kim, J.C. Dihydrotestosterone-inducible dickkopf 1 from balding dermal papilla cells causes apoptosis in follicular keratinocytes. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2008, 128, 262–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Nan, W.; Si, H.; Wang, S.; Zhang, H.; Li, G. Pantothenic acid promotes dermal papilla cell proliferation in hair follicles of American minks via inhibitor of DNA Binding 3/Notch signaling pathway. Life Sci. 2020, 252, 117667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yang, Z.; Li, Z.; Gu, L.; Wang, Y.; Sung, C. Exogenous IGF-1 promotes hair growth by stimulating cell proliferation and down regulating TGF-β1 in C57BL/6 mice in vivo. Growth Horm. IGF Res. 2014, 24, 89–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, M.; Guo, H.; Qiu, W.; Lai, X.; Yang, T.; Widelitz, R.B.; Chuong, C.; Lian, X.; Yang, L. Modulating hair follicle size with Wnt10b/DKK1 during hair regeneration. Exp. Dermatol. 2014, 23, 407–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovale, L.; Lee, S.; Song, M.; Lee, J.; Son, H.J.; Sung, Y.K.; Kwack, M.H.; Choe, W.; Kang, I.; Kim, S.S.; et al. Gynostemma pentaphyllum Hydrodistillate and Its Major Component Damulin B Promote Hair Growth-Inducing Properties In Vivo and In Vitro via the Wnt/β-Catenin Pathway in Dermal Papilla Cells. Nutrients 2024, 16, 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, C.A.; Chen, J.C.; Cerise, J.E.; Jahoda, C.A.B.; Christiano, A.M. Microenvironmental reprogramming by three-dimensional culture enables dermal papilla cells to induce de novo human hair-follicle growth. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 19679–19688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazi, T.; Niibe, I.; Nishikawa, A.; Matsuzaki, T. Optimal stimulation toward the dermal papilla lineage can be promoted by combined use of osteogenic and adipogenic inducers. FEBS Open Bio 2020, 10, 197–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bejaoui, M.; Oliva, A.K.; Ke, M.S.; Ferdousi, F.; Isoda, H. 3D Spheroid Human Dermal Papilla Cell as an Effective Model for the Screening of Hair Growth Promoting Compounds: Examples of Minoxidil and 3,4,5-Tri-O-caffeoylquinic acid (TCQA). Cells 2022, 11, 2093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andl, T.; Zhou, L.; Zhang, Y. The dermal papilla dilemma and potential breakthroughs in bioengineering hair follicles. Cell Tissue Res. 2023, 391, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, H.W.; Kim, H.J.; Jeon, C.Y.; Lee, Y.; Kim, M.; Kim, J.; Kim, S.R.; Lee, S.; Lim, D.C.; Park, H.D.; et al. Hair Growth Promoting Effects of 15-Hydroxyprostaglandin Dehydrogenase Inhibitor in Human Follicle Dermal Papilla Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, C.Y.; Go, M.Y.; Kim, I.; Park, M.; Lee, H.W.; Kim, Y.; Shin, D.W. Hair Growth-Promoting Effects of Astragalus sinicus Extracts in Human Follicle Dermal Papilla Cells. Cosmetics 2025, 12, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Y.; Luo, B.; Deng, Z.; Wang, B.; Liu, F.; Li, J.; Shi, W.; Xie, H.; Hu, X.; Li, J. Mitochondrial aerobic respiration is activated during hair follicle stem cell differentiation, and its dysfunction retards hair regeneration. PeerJ 2016, 4, e1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.Y.; Choi, Y.; Kim, J.; Park, S.Y.; Nam, Y.J.; Lee, S.Y.; Jeon, J.H.; Jin, M.H.; Lee, S. Polygonum multiflorum extract support hair growth by elongating anagen phase and abrogating the effect of androgen in cultured human dermal papilla cells. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2020, 20, 144–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand, M.D.; Nicholls, D.G. Assessing mitochondrial dysfunction in cells. Biochem. J. 2011, 435, 297–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Man, X.; Li, C.; Chen, J.; Zhou, J.; Cai, S.; Lu, Z.; Zheng, M. VEGF induces proliferation of human hair follicle dermal papilla cells through VEGFR-2-mediated activation of ERK. Exp. Cell Res. 2012, 318, 1633–1640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.H.; Lee, M.J.; Lee, W.; Pyo, J.; Shin, M.; Hwang, G.S.; Shin, D.; Kim, C.E.; Park, E.; Kang, K.S. Hair Growth Stimulation Effect of Centipeda minima Extract: Identification of Active Compounds and Anagen-Activating Signaling Pathways. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Zhu, J.; Jing, J.; Xue, D.; Liu, H.; Zheng, M.; Lu, Z. VEGF165 modulates proliferation, adhesion, migration and differentiation of cultured human outer root sheath cells from central hair follicle epithelium through VEGFR-2 activation in vitro. J. Dermatol. Sci. 2014, 73, 152–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Shin, J.Y.; Choi, Y.; Kang, N.G.; Lee, S. Anti-Hair Loss Effect of Adenosine Is Exerted by cAMP Mediated Wnt/β-Catenin Pathway Stimulation via Modulation of Gsk3β Activity in Cultured Human Dermal Papilla Cells. Molecules 2022, 27, 2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, K.; Hwang, Y.; Lee, M.; Kim, N.; Roh, S.; Lee, Y.; Kim, C.D.; Lee, J.; Choi, K. Adenosine stimulates growth of dermal papilla and lengthens the anagen phase by increasing the cysteine level via fibroblast growth factors 2 and 7 in an organ culture of mouse vibrissae hair follicles. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2012, 29, 195–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.J.; Kim, M.W.; Gil, H.; Chung, Y.J.; Kim, E.M. In vitro hair growth-promoting effect of Lgr5-binding octapeptide in human primary hair cells. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2024, 23, 986–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Betriu, N.; Jarrosson-Moral, C.; Semino, C.E. Culture and Differentiation of Human Hair Follicle Dermal Papilla Cells in a Soft 3D Self-Assembling Peptide Scaffold. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamida, O.B.; Kim, M.K.; Sung, Y.K.; Kim, M.K.; Kwack, M.H. Hair Regeneration Methods Using Cells Derived from Human Hair Follicles and Challenges to Overcome. Cells 2024, 14, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.; Zhu, Z.; Sun, X.; Fu, X. Functional hair follicle regeneration: An updated review. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, Y.; Ntege, E.H.; Sunami, H.; Inoue, Y. Regenerative medicine strategies for hair growth and regeneration: A narrative review of literature. Regen. Ther. 2022, 21, 527–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.; Song, S.; Sung, J. Recent Advances in Drug Development for Hair Loss. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 3461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duchi, S.; Rebollo Torregrosa, P.; Hajuj, A.; Molho, D.; Shkoor, R.; Saada, N.A.; Fernandez, D.G.; Goldstein, D.; Perez-Fernandez, A. The formulation and in vitro evaluation of WS Biotin, a novel encapsulated form of D-Biotin with improved water solubility for hair and skin treatment applications. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2024, 46, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madaan, A.; Verma, R.; Singh, A.T.; Jaggi, M. Review of Hair Follicle Dermal Papilla cells as in vitro screening model for hair growth. Int. J. Cosmet. Sci. 2018, 40, 429–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, D.P.; Swink, S.M.; Castelo-Soccio, L. A Review of the Use of Biotin for Hair Loss. Skin. Appendage Disord. 2017, 3, 166–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almohanna, H.M.; Ahmed, A.A.; Tsatalis, J.P.; Tosti, A. The Role of Vitamins and Minerals in Hair Loss: A Review. Dermatol. Ther. 2019, 9, 51–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.