Abstract

Cholecystokinin 1 receptor (CCK1R) is activated by singlet oxygen (1O2) in type II photodynamic action in isolated rat, mouse, and Peking duck pancreatic acini. To examine whether this is maintained outside the microenvironment of pancreatic acinar cell, photodynamic activation of CCK1R from human, rat, mouse, and Peking duck expressed in CHO-K1 cells was examined, as monitored with Fura-2 fluorescence calcium imaging. Photodynamic action with sulphonated aluminum phthalocyanine was found to trigger persistent calcium oscillations in CCK1R-CHO-K1 cells transfected with human, rat, mouse or Peking duck CCK1R gene, which were blocked by 1O2 quencher Trolox C. After tagging protein photosensitizer miniSOG to C-terminus of these CCK1R, photodynamic action was found to similarly trigger persistent calcium oscillations in CCK1R-miniSOG-CHO-K1 cells expressing human, rat, mouse, and Peking duck receptor constructs. Incubation with Trolox C 300 μM during LED light irradiation also prevented photodynamic CCK1R activation in CCK1R-miniSOG-CHO-K1 cells. In contrast, human M3R was not photodynamically activated with SALPC or tagged miniSOG as the photosensitizer. These data, together, suggest that photodynamic CCK1R activation is maintained outside of the pancreatic acinar cell, making possible photodynamic CCK1R activation in CCK1R-expressing organs and tissues other than the pancreas, with high spatiotemporal precision.

1. Introduction

G protein coupled receptors (GPCR) are among the largest families of functional proteins [1,2]. GPCR ligands account for a predominant proportion of all clinically available drugs [3,4]. The large repertoires of small molecule ligands for GPCR are relatively well-explored for pharmacology and therapeutics against human and animal diseases [4,5], but ligand-independent pharmacology of different sub-families of GPCR, however, remains poorly investigated, let alone with any spatial or temporal precision [6].

Ligand-independent GPCR regulation typically includes temperature regulation [7,8,9,10,11], regulation by the lipid microenvironment of the plasma membrane such as cholesterol content [12,13,14], by transmembrane potential [15,16,17,18,19], and regulation by localized concentration of reactive oxygen species such as the lowest lying excited state of molecular oxygen, the delta singlet oxygen (Δ1O2) [6,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29].

Most interestingly, cholecystokinin 1 receptor (CCK1R), a member of the A-class GPCR predominantly expressed at the basolateral plasma membrane in pancreatic acinar cells, has been shown to be activated permanently by 1O2 generated via type II photodynamic action, with inherent spatial and temporal precision, but with the antagonist-binding site remaining fully intact after photodynamic activation [6,21,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31]. CCK1R both in the freshly isolated mammalian (rat, mouse), avian (Peking duck) pancreatic acini [21,31], and in the rat pancreatic acinar tumor cell line AR4-2J could be readily activated via type II photodynamic action, with either photosensitizer dye (such as sulphonated aluminum phthalocyanine, SALPC) [21,23] or with genetically encoded protein photosensitizers (GEPP) (such as KillerRed, miniSOG) after a brief pulse of light irradiation (1–2 min) [23,25,26,27,28]. The detailed molecular mechanisms for such permanent photodynamic activation of CCK1R are being elucidated (reviewed in [6,22,29,32,33,34]) and the list of GPCR permanently activated by photodynamic action is expanding [35].

The agonist-stimulated activation of CCK1R receptors are known to regulate vital physiological functions [36,37]. The human, rat, mouse, chicken, and Peking duck CCK1R all regulate satiety sensation and feeding, gallbladder contraction, gastric emptying, neurodevelopment, digestive enzyme secretion, inflammation, muscle growth and body weight gain, and other functions [38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61]. Although CCK1R is expressed and functions in numerous organs and tissues other than the exocrine pancreas, it is not known whether CCK1R outside of the microenvironment of the pancreatic acinar cell would maintain the special property of being activated by photodynamic action, bearing in mind that the plasma membrane environment, such as cholesterol content, has a major effect on CCK1R activation by agonist stimulation with CCK octapeptide [12,13,14].

The aim of the present work was, therefore, to investigate whether CCK1R expressed outside of the microenvironment of the pancreatic acinar cell would maintain this special property of permanent photodynamic activation. The photodynamic activation of the human, rat, mouse, and Peking duck was therefore examined after ectopically expression in CHO-K1 cells (the alternative is to try to isolate and examine each and every CCK1R-expressing native cell type). Data obtained indicate that photodynamic action with SALPC, or with miniSOG tagged to C-terminus of CCK1R, activated both the free-standing CCK1R and miniSOG-tagged CCK1R (construct CCK1R-miniSOG), confirming that photodynamic CCK1R activation is possible outside of the microenvironment of the pancreatic acinar cell. In parallel experiments, the human M3R was found not photodynamically activated with SALPC or with tagged miniSOG as the photosensitizer.

2. Results

2.1. Agonist-Stimulated Activation of Ectopically Expressed Human, Rat, Mouse and Peking Duck CCK1R

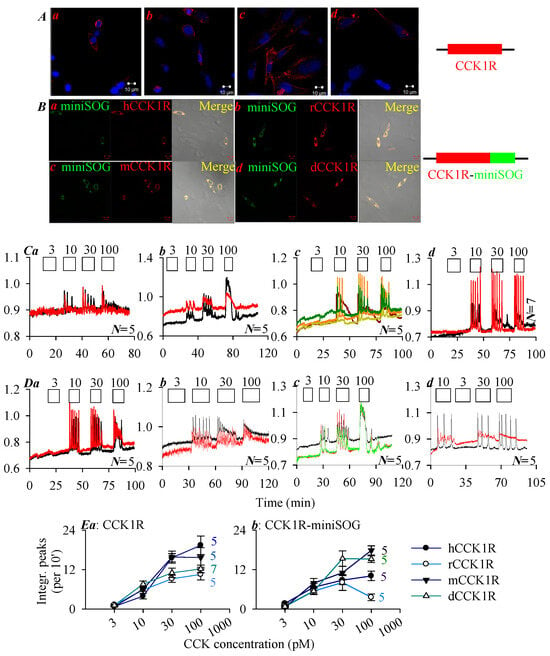

CHO-K1 cells transfected with plasmid pCCK1R-cDNA3.1+ containing the CCK1R gene or plasmid pCCK1R-miniSOG-cDNA3.1+ containing fused construct CCK1R-miniSOG (Figure 1A,B) were processed for immunocytochemistry. Confocal imaging revealed plasma membrane CCK1R localization (red, Figure 1A) or localization of construct CCK1R-miniSOG (yellow) containing CCK1R (red) and miniSOG (green) (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

Human, rat, mouse, Peking duck CCK1R and their miniSOG constructs CCK1R-miniSOG were expressed and stimulated with CCK octapeptide. Immunocytochemsitry is shown in panels (A,B), whereas calcium imaging traces are shown in panels (C,D). (A) CCK1R expression: (a) hCCK1R, (b) rCCK1R, (c) mCCK1R, (d) dCCK1R. (B) CCK1R-miniSOG expression: (a) hCCK1R-miniSOG, (b) rCCK1R-miniSOG, (c) mCCK1R-miniSOG, (d) dCCK1R-miniSOG. Twenty-four (24) hours after transfection, the transfected cells were processed for immunocytochemistry. The fixed and attached cells were incubated sequentially with primary rabbit anti-CCK1R antibody and TRITC-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit secondary antibody; the expression of CCK1R (A(a–d): TRITC, λex 543 nm; Hochest 33342, λex 405 nm), and CCK1R-miniSOG (B(a–d): TRITC, λex 543 nm; miniSOG, λex 488 nm) were verified, as seen in the merged images (B(a–d)). Scale bars: 10 μm. CHO-K1 cells were transfected with plasmid pCCK1R-3.1+ (A) or pCCK1R-miniSOG-3.1+ (B). Twenty-four (24) h after transfection, CCK1R- or CCK1R-miniSOG-CHO-K1 cells were loaded with Fura-2 AM, attached to the bottom cover-slip of Sykes-Moore perfusion chambers, and perifused. CCK at 3, 10, 30, and 100 pM were added, as indicated by the horizontal bars. (C(a–d)) CHO-K1 cells expressing the human, rat, mouse, and Peking duck CCK1R, respectively. (D(a–d)) CHO-K1 cells expressing construct CCK1R-miniSOG, with CCK1R of the human, rat, mouse, and Peking duck origin. The calcium traces shown in (C,D) are from one typical experiment out of N identical experiments (N = 5–7), with each color-coded trace representing one individual cell. (E) Dose–response curves of CCK stimulation in CCK1R-CHO-K1 (a) and CCK1R-miniSOG-CHO-K1 (b) cells, with integrated calcium peak areas above baseline (per 10 min) calculated. (E(a)) CCK1R. (E(b)) CCK1R-miniSOG.

To examine whether the human, rat, mouse, and Peking duck CCK1R ectopically expressed in CCK1R-CHO-K1 and CCK1R-miniSOG-CHO-K1 cells retained their function, these cells were stimulated with CCK octapeptide (Figure 1C,D). Since CCK1R is known to be coupled to the Gq—phospholipase C—inositol trisphosphate (IP3)—IP3 receptor (IP3R)—Ca2+ signaling pathway, CCK1R activation was monitored by imaging cytosolic calcium concentration [2,22,30,32,36]. Stimulation with CCK 3, 10, 30, and 100 pM was found to elicit concentration-dependent calcium increases in CCK1R-CHO-K1 cells expressing the human, rat, mouse, and Peking duck receptor (Figure 1C(a–d)), and also in CCK1R-miniSOG-CHO-K1 cells expressing the human, rat, mouse, and Peking duck receptor construct CCK1R-miniSOG (Figure 1D(a–d)). Very clear CCK dose–response curves were found (calcium peak area above baseline) (Figure 1E). The dose–response curves for both free-standing human, rat, mouse, Peking duck CCK1R (Figure 1E(a)) and for the corresponding CCK1R-miniSOG construct (Figure 1E(b)) are shown. The minimum effective CCK concentrations used to trigger regular calcium oscillations in CCK1R-CHO-K1 and CCK1R-miniSOG-CHO-K1 cells were found to remain in the low picomolar range (Figure 1).

The susceptibility of the ectopically expressed human, rat, mouse, Peking duck CCK1R and their miniSOG-tagged constructs to photodynamic activation, with photosensitizer SALPC and miniSOG respectively, was then examined, as shown below.

2.2. Photodynamic Activation of the Human, Rat, Mouse and Peking Duck CCK1R with Photosensitizer SALPC

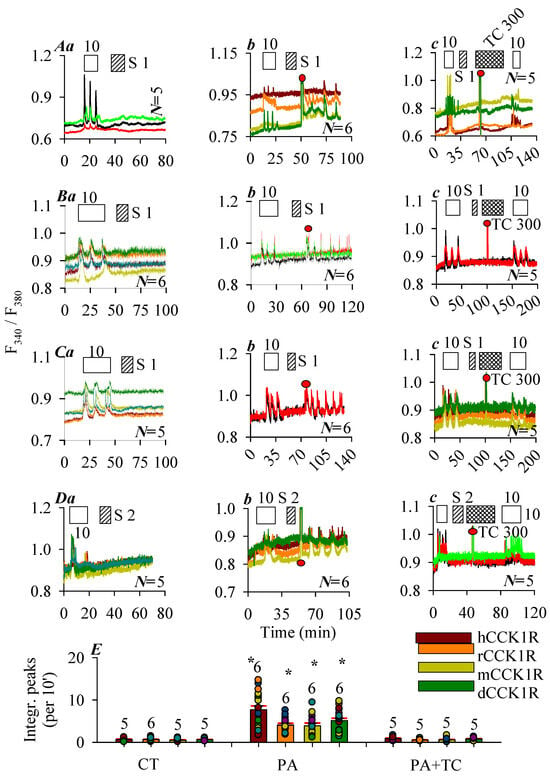

In this series of experiments, photosensitizer SALPC (1 or 2 μM) in the dark was found to have no effect on basal calcium in CCK1R-CHO-K1 cells expressing the human, rat, mouse, and Peking duck CCK1R, although stimulation with CCK 10 pM elicited regular calcium oscillations, which were readily washed out (Figure 2A(a), hCCK1R; Figure 2B(a), rCCK1R; Figure 2C(a), mCCK1R; Figure 2D(a), dCCK1R). After the washing out of SALPC (1, 2 μM), red LED irradiation (675 nm, 50, 60, 50, 40 mW·cm−2, 1.5 min) was found to trigger persistent calcium oscillations in CHO-K1 cells positively expressing the human, rat, mouse, and Peking duck CCK1R (Figure 2A(b), hCCK1R; Figure 2B(b), rCCK1R; Figure 2C(b), mCCK1R; Figure 2D(b), dCCK1R). Repeat SALPC (1, 2 μM) photodynamic action (675 nm, 50, 60, 50, 40 mW·cm−2, 1.5 min), but in the presence of the 1O2 quencher Trolox C 300 μM, failed to induce any calcium spikes, although a second dose of CCK 10 pM readily triggered calcium oscillations (Figure 2A(c), hCCK1R; Figure 2B(c), rCCK1R; Figure 2C(c), mCCK1R; Figure 2D(c), dCCK1R). In separate experiments, it was confirmed that Trolox C 300 μM had no effect on calcium oscillations induced by agonist CCK 10 pM in CCK1R-CHO-K1 cells expressing the human, rat, mouse, and Peking duck CCK1R (Figure S1b–e).

Figure 2.

Photodynamic CCK1R activation with SALPC. CHO-K1 cells were transfected with plasmid pCCK1R and, 24 h later, CCK1R-CHO-K1 cells were loaded with Fura-2 AM, attached to the bottom cover-slips of Sykes-Moore perfusion chambers, and perifused. CCK (empty bar), SALPC (stippled bar), Trolox C (crossed bar), and red LED (675 nm, 50 mW·cm−2, 1.5 min) irradiation were applied as indicated by the horizontal bars: (A) Human CCK1R; (B), rat CCK1R; (C), mouse CCK1R; (D), Peking duck CCK1R. In each case, panel (a) shows CCK stimulation followed by SALPC; (b) CCK stimulation followed by SALPC and LED irradiation; (c) CCK stimulation followed by SALPC, LED irradiation in the presence of Trolox C, and finished with a second identical dose of CCK. Note that CCK 10 pM was applied in (A–D). SALPC 1 μM was applied in (A–C), 2 μM in (D). Trolox C 300 μM was applied in (A–D). Red LED (675 nm, 1.5 min) (filled red circle: ●) irradiation was at 50 mW·cm−2 in (A,C), 60 mW·cm−2 in (B), and 40 mW·cm−2 in (D). The original calcium tracings in panels (A–D) are each from one typical experiment out of N repeats (as indicated in panel), with every color-coded trace representing one individual cell. (E) The calcium responses were calculated as integrated peak area per 10 min (integrated peak area during 30 min immediately after red LED irradiation in (A–D) (b,c); corresponding time period 30 min in (A–D) (a) were presented. Photodynamic activation (PA) of CCK1R was compared with controls (CT) in the absence of SALPC and LED irradiation, and with photodynamic activation in the presence of Trolox C (PA + TC). Asterisk (*) indicates statistical significance at p < 0.05 (N = 5–7). Symbols on graph: CT: control; PA: photodynamic action; TC: Trolox C; S: SALPC.

Quantification of photodynamically–induced calcium spikes demonstrated clearly that SALPC photodynamic action (SALPC 1 or 2 μM + 675 nm, 60, 50, 45, 40 mW·cm−2, 1.5 min) activated the free-standing human, rat, mouse, and Peking duck CCK1R, but these photodynamic activations were blocked by the 1O2 quencher Trolox C (Figure 2E).

2.3. Photodynamic Activation of the Human, Rat, Mouse and Peking Duck CCK1R with Tagged Protein Photosensitizer miniSOG

Effects of photodynamic action with the in-frame miniSOG on human, rat, mouse, and Peking duck CCK1 were examined in CCK1R-miniSOG-CHO-K1 cells expressing construct CCK1R-miniSOG (miniSOG tagged to C-terminus of CCK1R) (Figure 1B). Parental CHO-K1 cells transfected with blank vector pcDNA3.1+ (pcDNA3.1+-CHO-K1 cells) showed no endogenous CCK1R; CCK of up to 100 nM did not have any effect on basal calcium in these empty vector-transfected pcDNA3.1+-CHO-K1 cells (Figure S1a).

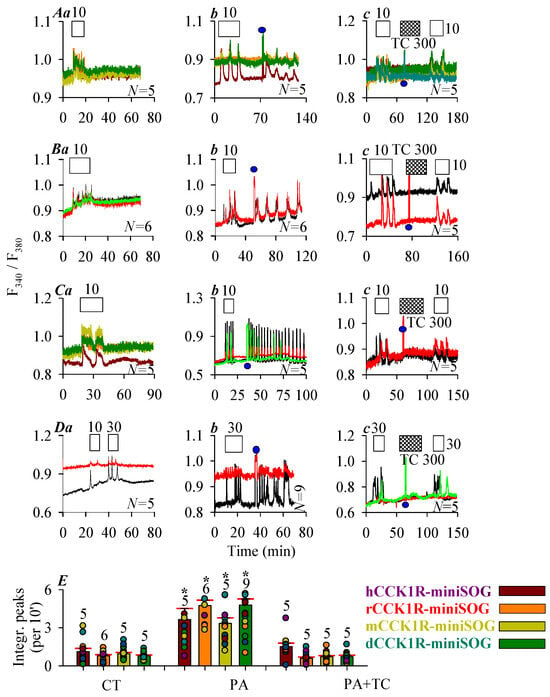

CCK at 10 or 30 pM were found to elicit robust calcium responses in CHO-K1 cells expressing the human, rat, mouse, and Peking duck receptor construct CCK1R-miniSOG (Figure 3A(a), hCCK1R-miniSOG; Figure 3B(a), rCCK1R-miniSOG; Figure 3C(a), mCCK1R-miniSOG; Figure 3D(a), pdCCK1R-miniSOG). CCK-induced calcium oscillations disappeared immediately after wash out of CCK (Figure 3A(a–c)–D(a–c)), note that subsequent blue LED irradiation (450 nm, 85 mW·cm−2, 1.5 min) elicited fresh calcium oscillations which persisted long after cessation of LED light irradiation (Figure 3A(b), hCCK1R; Figure 3B(b), rCCK1R; Figure 3C(b), mCCK1R; Figure 3D(b), dCCK1R). Although 1O2 quencher Trolox C (300 μM) had no effect on calcium oscillations induced by agonist CCK in CHO-K1 cells expressing the human, rat, mouse, and Peking duck receptor construct CCK1R-miniSOG (Figure S1f–i), in the presence of Trolox C, blue LED irradiation no longer induced any calcium increases, although all subsequent second dose of CCK (10 or 30 pM) triggered regular calcium oscillations (Figure 3A(c), hCCK1R; Figure 3B(c), rCCK1R; Figure 3C(c), mCCK1R; Figure 3D(c), dCCK1R). Quantified calcium response after photodynamic action (450 nm, 85 mW·cm−2, 1.5 min) in CCK1R-miniSOG-CHO-K1 cells confirmed activation of human, rat, mouse, and Peking duck CCK1 receptors in construct CCK1R-miniSOG, which was prevented by treatment with Trolox C (Figure 3E).

Figure 3.

Photodynamic CCK1R activation with C-terminal-tagged miniSOG. CHO-K1 cells were transfected with plasmid pCCK1R-miniSOG, with CCK1R gene of human, rat, mouse, and Peking duck origin. Twenty-four hours (24 h) after transfection, CCK1R-miniSOG-CHO-K1 cells were loaded with Fura-2 AM, attached to the bottom cover-slip of Sykes-Moore perfusion chambers, and perifused. CCK (empty bar), Trolox C (crossed bar), and blue LED (450 nm, 85 mW·cm−2, 1.5 min) (filled blue circle: ●) irradiation were applied, as indicated by the horizontal bars ((A), human; (B), rat; (C), mouse; (D), Peking duck). In each case in (A–D), (a) shows CCK stimulation alone; (b) CCK followed by a pulse of blue LED light, (c) CCK 10 pM followed by a pulse of blue LED light in the presence of Trolox C 300 μM (A–D), and finally followed by a second identical dose of CCK. Note the different CCK concentrations used: CCK 10 pM in (A–C), CCK 30 pM (D). The color-coded calcium traces shown (each trace from one individual cell) are from one typical experiment out of N identical experiments (N = 5–9). (E) The calcium peak area above baseline (per 10 min) from controls (CT) (from panels (A–D) (a)), photodynamically treated cells (PA) (from panels (A–D) (b)), and photodynamically treated cells in the presence of Trolox C (PA + TC) (from panels (A–D) (c)) were calculated for 30 min immediately after cessation of LED irradiation or the corresponding time period in the absence of light and compared (A–D). The asterisk (*) indicates statistically significant differences compared with corresponding controls at p < 0.05 with Student’s t-test.

The above data clearly indicated that photodynamic action with the photosensitizer dye SALPC or with the in-frame protein photosensitizer miniSOG activated human, rat, mouse, and Peking duck CCK1R. Photodynamic CCK1R activation is maintained outside of the plasma membrane microenvironment of the pancreatic acinar cell. For comparisons, we also examined the possible effect of photodynamic action with SALPC or tagged miniSOG on human acetylcholine M3 receptors in parallel experiments.

2.4. Lack of Photodynamic Effect on Human M3R

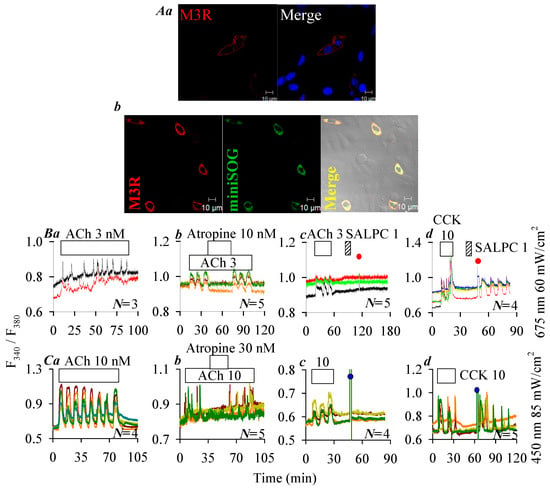

Immunocytochemistry performed 24 h after plasmid transfection revealed plasma membrane localization of the human M3R (red) in hM3R-CHO-K1 cells (Figure 4A(a)), and plasma membrane localization of construct hM3R-miniSOG (orange in merged micrograph) containing hM3R (red) and miniSOG (green) in hM3R-miniSOG-CHO-K1 cells (Figure 4A(b)). Note that the intracellular expression of receptor construct M3R-miniSOG seemed to have increased compared to M3R receptor alone (compare Figure 4A(a) and Figure 4A(b)). It would be interesting to investigate such a difference if confirmed true in the future. Since M3R is coupled to the Gq—phospholipase C—inositol trisphosphate (IP3)—IP3 receptor (IP3R)—Ca2+ signaling pathway, M3R activation was monitored by imaging cytosolic calcium concentration [6,20,21]. ACh 3 nM triggered regular calcium oscillations in hM3R-CHO-K1 cells (Figure 4B(a)), which were inhibited reversibly with atropine 10 nM (Figure 4B(b)). After wash out of ACh-triggered calcium oscillations in hM3R-CHO-K1 cells, perfusion of SALPC 1 μM or subsequent LED light (675 nm) irradiation (60 mW·cm−2, 1.5 min) was found to have no effect on baseline calcium (Figure 4B(c)). However, persistent calcium oscillations appeared under identical photodynamic intensity (SALPC 1 μM, LED 675 nm, 60 mW·cm−2, 1.5 min) in rCCK1R-CHO-K1 cells expressing the rat CCK1R in time-matched parallel experiments (Figure 4B(d)). Although both CCK stimulation and SALPC photodynamic action induced calcium oscillations (Figure 4B(d)), the CCK (10 pM) effect was readily washed out, but photodynamically induced calcium oscillations persisted after completion of the 1.5 min duration of light irradiation (Figure 4B(d)).

Figure 4.

Lack of photodynamic effect on hM3R plasma membrane expression of hM3R (A(a)), and of fusion protein hM3R-miniSOG (A(b)). Twenty-four (24) hours after transfection, cells were fixed and attached to cover-slips, incubated sequentially with primary rabbit anti-M3R antibody and TRITC-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit secondary antibody. Expression of M3R (A(a), λex: TRITC/543 nm; Hochest 33342, λex: 405 nm), and of M3R-miniSOG (A(b), λex: TRITC/543 nm; λex: 488 nm) were verified in merged images. Scale bars: 10 μm. hM3R- or rCCK1R-CHO-K1 and hM3R- or CCK1R-miniSOG-CHO-K1 cells loaded with Fura-2 AM were attached to cover-slips forming the bottom part of a Sykes-Moore perfusion chamber, perfused, and exposed to CCK (empty bar), ACh (empty bar), atropine (empty bar) and SALPC (stippled bar) as indicated by the horizontal bars (B,C): (B(a)) ACh 3 nM; (B(b)) ACh 3 nM, atropine 10 nM; (B(c)) ACh 3 nM, SALPC 1 μM, red light (675 nm, 60 mW·cm−2, 1.5 min); (B(d)) CCK 10 pM, SALPC 1 μM, red light (675 nm, 60 mW·cm−2, 1.5 min); (C(a)) ACh 10 nM, 65 min; (C(b)) ACh 10 nM, atropine 30 nM; (C(c)) ACh 10 nM, blue light (450 nm, 85 mW·cm−2, 1.5 min); (C(d)) CCK 10 pM, blue light (450 nm, 85 mW·cm−2, 1.5 min). In each panel (B(a–d),C(a–d)), the calcium traces are from one typical experiment out of N identical repeats (N = 3–5), with each trace representing one individual cell. The time of LED light application is indicated by red (675 nm, ●) or blue (450 nm, ●) filled circles.

ACh 10 nM triggered calcium oscillations also in hM3R-miniSOG-CHO-K1 cells expressing the construct hM3R-miniSOG (Figure 4C(a)). ACh-triggered calcium oscillations were blocked reversibly by atropine 30 nM (Figure 4C(b)). Calcium increases elicited by ACh 10 nM were readily washed out in hM3R-miniSOG-CHO-K1 cells, but subsequent LED (450 nm) light irradiation (85 mW·cm−2, 1.5 min) had no effect (Figure 4C(c)). In time-matched (same day experiments) parallel experiments, however, it was re-confirmed that after wash out of CCK 10 pM-elicited calcium oscillations, LED light (450 nm) irradiation (85 mW·cm−2, 1.5 min) induced persistent calcium oscillations in hCCK1R-miniSOG-CHO-K1 cells expressing the construct hCCK1R-miniSOG (Figure 4C(d)).

Therefore human, rat, mouse, and Peking duck CCK1R could all be photodynamically activated in type II photodynamic action, with either SALPC as the photosensitizer or with miniSOG attached to the C-terminal of the receptor as the photosensitizer. Under identical conditions, the human M3R was not at all affected by photodynamic action.

The protein sequences and structures of the human, rat, mouse, and Peking duck CCK1R and human M3R were then examined to shed possible light on the molecular mechanisms for photodynamic activation of CCK1R or the lack of effect on the M3R.

2.5. Structural Correlates of Permanent Photodynamic Activation of the Human, Rat, Mouse and Peking Duck CCK1R

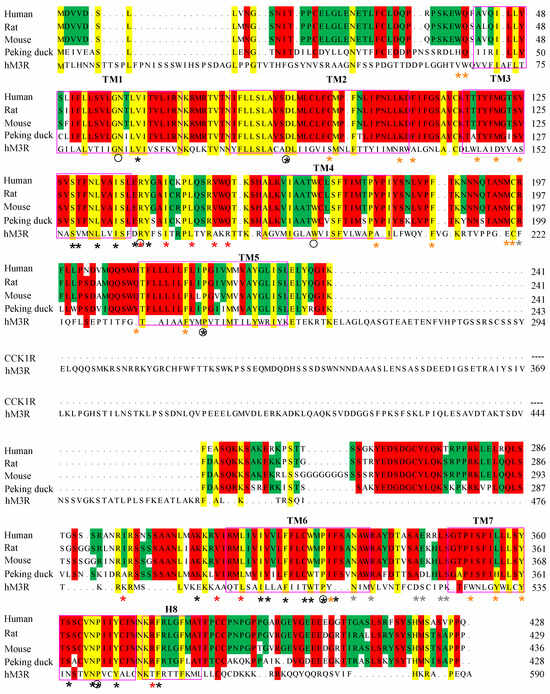

Examination of the receptor protein sequence revealed that the human, rat, mouse and Peking duck CCK1R all shared the same “Y3.30F3.31M3.32” motif in TM3, which has been found previously to be important for photodynamic activation [27,28]. This motif is lacking in the human M3R; the corresponding residue triplet is A3.30I3.31D3.32 (Figure 5). It is noted that all the higher vertebrate CCK1R also shared an extended version of “YFM” in TM7—“Y7.53C7.54F7.55M7.56” (Figure 5, denoted with the Ballesteros-Weinstein numbering system, see legend), whereas in the un-susceptible human M3R, the corresponding sequence is “Y7.53A7.54L7.55C7.56” (Figure 5). Of the critical residues identified in early point mutation experiments of human CCK1R (marked with an asterisk * in Figure 5), only C2.57, M3.32, Y3.51, Y4.60, M195.ECL2, C196.ECL2, C6.47, W6.48, Y7.43, and Y7.53 are completely conserved in the vertebrate CCK1R examined in this work and also susceptible to 1O2 oxidation (Figure 5). Note that Y7.53 is also part of the “Y7.53C7.54F7.55M7.56” motif mentioned above. A cluster of 1O2-susceptible residues “Y418S/T419H420M421” in the C-terminus of the human CCK1R is also found in the rat, mouse, and Peking duck CCK1R; a similar cluster of residues is not found in the human M3R (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Sequence alignment of CCK1R. The human (Homo sapiens), rat (Rattus norvegicus), mouse (Mus musculus), and Peking duck (Anas platyrhynchos domestica) CCK1R full sequences are aligned. hCCK1R (NP_000721.1), rCCK1R (NP_036820.1), mCCK1R (NP_033957.1), and dCCK1R (MN250295.1) were aligned with Mega 7. Asterisks (*) indicate key residues for the activation of hCCK1R by CCK-8S (grey, CCK-8 recognition; brown, CCK-8 binding; black, conformational change; red, G protein binding). Black circles denote Ballesteros–Weinstein reference residues N1.50, D2.50, R3.50, W4.50, P5.50, P6.50, and P7.50. Pink rectangles outline TM1-7 and H8, with lettering placed above the sequence. Colored background indicates complete identity of residues.

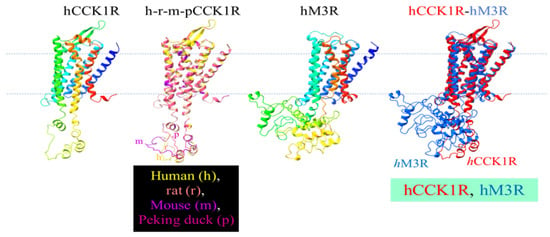

The solved human CCK1R structure (7F8X) was used as a template to predict the structure of the rat, mouse, and Peking duck CCK1R (Figure 6). The similarities of these human receptor homologs are readily noted. Other than the 7 TM helix, note the short ICL1, ECL1, the twisted ICL2, bipartite beta sheet ECL2, extended ICL3, near horizontal helical ECL3, and helix 8 (Figure 6). Note the overlapping secondary structures in ICL3, with noted variations in the secondary-structure-free region in all these vertebrate structures (Figure 6). A comparison of hCCK1R and hM3R structures reveals that not much deviates among TM1-4, but TM5 in hM3R dips deeply into the cytosol and ICL3 in hM3R is much more extensive (Figure 6). Merged structures of human hCCK1R/hM3R revealed extensive diversion in ICL3 in the refractory hM3R, among other more subtle differences (Figure 6). The beta sheet structure in ECL2 and the horizontal helix in ECL3 in CCK1R are not seen in ECL2 and ECL3 in hM3R, but a more extensive helix 8 C-terminal tail is noted in the human ACh M3R (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Modeled structure of human, rat, mouse, Peking duck CCK1R, of human M3R, of merged mammalian and avian CCK1R, and of merged human CCK1R and M3R. The 3D structures were generated by Swiss-Model using human CCK1R (PDB: 7F8X) as template. Human CCK1R and M3R are each color gradient-coded (blue-to-red corresponds to N- to C-terminus). Human, rat, mouse, and Peking duck CCK1R are merged (h-r-m-p) with ChimeraX 1.3: human, yellow; rat, brown; mouse, purple; Peking duck, erythritol (a version of merged h-r-m-pCCK1R has been published previously in [31]). The human M3R structure is generated by Swiss-Model using rat M3R (PDB: 4DAJ) as template. Human CCK1R and M3R are merged with ChimeraX 1.3: hCCK1R, red; hM3R, blue.

3. Discussion

In the present work, it was found that the human, rat, mouse, and Peking duck CCK1R ectopically expressed in positive CCK1R-CHO-K1 cells were all photodynamically activated with either perifused photosensitizer SALPC or in CCK1R-miniSOG-CHO-K1 cells with C-terminal-tagged protein photosensitizer miniSOG. The photodynamic CCK1R activation was blocked with 1O2 quencher Trolox C. Although the CCK1R were all susceptible (with some variations in sensitivity and, therefore, varied LED 450 nm power density was used) to photodynamic activation, the human, rat, mouse, and Peking duck CCK1R showed similar responses towards picomolar CCK stimulation. These data suggest that photodynamic CCK1R activation is maintained outside of the plasma membrane microenvironment of the pancreatic acinar cell.

CCK stimulation of the human, rat, mouse, and Peking duck CCK1R, ectopically expressed as free-standing CCK1R or as construct CCK1R-miniSOG in CHO-K1 cells, triggered calcium oscillation dose-dependently (Figure 1). Tagging with miniSOG did not seem to drastically change CCK1R or CCK1R-miniSOG sensitivity towards CCK stimulation (Figure 1).

It is known that SALPC photodynamic action activated CCK1R permanently both in the isolated rat, mouse, and Peking duck pancreatic acini [21,30,31] and activated human CCK1R ectopically expressed in CCK1R-HEK-293 cells [23]. SALPC (i.e., AlPcS4) with central conjugated Al3+ and four peripheral sulfonate groups showed good aqueous solubility and high 1O2 quantum yield [7,62,63,64,65]; both the central Al3+ and the peripheral sulfate groups have been found to be needed for photodynamic CCK receptor activation [35]. SALPC had no effect in the dark on baseline calcium in CCK1R-CHO cells expressing the human, rat, mouse, and Peking duck CCK1R (Figure 2A(a)–D(a)); but subsequent red LED light irradiation (675 nm, 60, 50, 40 mW·cm−2) triggered persistent calcium oscillations (Figure 2A(b)–D(b)); in the presence of the 1O2 quencher Trolox C, red LED light irradiation (675 nm, 60, 50, 40 mW·cm−2) no longer had any effect (Figure 2A(c)–D(c)). These data are similar to previous works with the human CCK1R [23,25,26,27,28]. This would suggest that all vertebrate CCK1R, ectopically expressed outside of the pancreatic acinar cell plasma membrane microenvironment, could be photodynamically activated with SALPC as the photosensitizer, with 1O2 being the predominant reactive intermediate.

The genetically encoded protein photosensitizer miniSOG (λex 448 nm, λem 500 nm), with a 1O2 quantum yield of ≥0.03 ± 0.01 [66], could effectively activate the human CCK1R photodynamically [23,25,26]. The present work found that miniSOG fusion to the C-terminal of CCK1R did not seem to change the receptor sensitivity drastically towards CCK stimulation, for all vertebrate CCK1R examined in this work (Figure 1). CCK stimulation induced calcium oscillations in all vertebrate receptor constructs in CCK1R-miniSOG-CHO-K1 cells, which were readily washed out (Figure 3A(a)–D(a)); LED (450 nm, 85 mW·cm−2) irradiation then induced fresh calcium oscillations (Figure 3A(b)–D(b)); In the presence of 1O2 quencher Trolox C, LED light irradiation (450 nm) no longer induced any calcium oscillations with all vertebrate CCK1R-miniSOG in transfected CHO-K1 cells (Figure 3A(c)–D(c)); The vitamin E analog of Trolox C, as 1O2 quencher in the μM to mM range, has been used before to block the effect of 1O2 [67,68,69]; we could confirm that Trolox C had no effect on CCK stimulated receptor activation and calcium oscillations (Figure S1).

Parallel experiments found that although the human hM3R was not affected by SALPC photodynamic action, with either SALPC or C-terminal-tagged miniSOG as the photosensitizer, the rat rCCK1R was readily activated in SALPC photodynamic activation (Figure 4). The human receptor construct hM3R-miniSOG was not photodynamically activated when the human receptor construct hCCK1R-miniSOG was readily photodynamically activated (Figure 4). These data confirm that neither the free-standing hM3R nor the hM3R-miniSOG construct share the property of photodynamical activation which is unique to human, rat, mouse, or Peking duck CCK1R, either as stand-alone CCK1R or as CCK1R-miniSOG construct (Figure 2 and Figure 3). It may be noted here that both vertebrate CCK1R (Figure 2, Figure 3 and Figure 4 in this work) and human CCK2R [35] are photodynamically activated with tagged protein photosensitizer miniSOG, although it is known that only agonist-stimulated activation of the human CCK1R is affected by plasma membrane cholesterol content whereas agonist-stimulated activation of the human CCK2R is not affected by cholesterol content [12,13,14,70]. This suggests that cholesterol oxidation might not play a role in the photodynamic activation of CCK1R and CCK2R, although singlet oxygen oxidation fingerprints have been established for plasma membrane cholesterol [71]. This is indirectly supported by the fact that although Y3.51 is critical for cholesterol binding and cholesterol sensitivity of agonist-stimulated activation of the human CCK1R [14], this Y3.51 is part of the ERY motif in CCK1R of all high vertebrates and of the DRY motif in the refractory human ACh M3R (Figure 5). In this context, it may be noted that while agonist-stimulated activation of CCK1R is affected by cholesterol and sphigolipid content, some other A-class GPCR are not [12,14,70,72]. It would be interesting, in the future, to investigate whether other plasma membrane physicochemical properties such as membrane viscosity, which is known to facilitate secretory protein accumulation at the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) exit sites (ERES) but attenuate transport to the Golgi apparatus [73], would affect photodynamic CCK1R activation at the plasma membrane. Other than plasma membrane-delimited expression, we also detected some intracellular expression of both CCK1R (Figure 1A) and M3R (Figure 4A(a)) and their constructs (CCK1R-miniSOG, Figure 1B, and M3R-miniSOG, Figure 4A(b)). This could mean that both receptors were in transit to the plasma membrane after synthesis at the endoplasmic reticulum or recycled to endosomes after activation at the plasma membrane. Whether intracellular CCK1R would play a role distinct from the cell surface receptor will be an interesting topic to further investigate in the future. For this matter, photodynamic activation of intracellular CCK1R with a tagged protein photosensitizer would offer obvious advantages over ligand-dependent receptor pharmacology, because no agonists would then be needed to cross the plasma membrane barrier and diffuse to the targeted intracellular receptor, as shown previously [26].

The human, rat, mouse, and Peking duck CCK1R protein sequence and structure are compared with the human M3R (Figure 5 and Figure 6) to shed light on the molecular mechanisms for photodynamic activation of CCK1R or lack of effect on M3R.

For agonist-stimulated activation of the human CCK1R, CCK-binding residues include those in the extracellular loops 1-3 (ECL1-3) (F107.ECL1, M195.ECL2, R197.ECL2, L347.ECL3, S348.ECL3), in hydrophobic cavities beneath the ECL (F107.ECL1, C196.ECL2, T118/3.29, M121/3.32), and in lower (towards intracellular space) parts of the TM domains (I210/5.39, N333/6.55, R342/6.58, Y7.43) [74,75,76]. CCK stimulation of CCK1R showed slight variations in sensitivity in the human, rat, mouse, and Peking duck receptors (Figure 1). Note that Cys2.57 and Trp6.48 are conserved in all these high vertebrate species, to stabilize the CCK1R structure (Figure 5). The ligand-binding pocket in the M3R crystal structure is composed of D3.32, S3.36, N3.37, T5.42, L225.ECL2, N6.52, K523.ECL3, and Y7.43; the bound ligand tended to be deeply embedded in the TM core spiral bundles and covered by conserved residues Y3.33, Y6.51, Y7.39 [77,78,79,80,81]. The M3R ligand-binding pocket contains only one residue Y7.43 which could be oxidized by 1O2. For CCK1R, the agonist CCK-binding pocket contains not only Y7.43, but also other 1O2-susceptible residues (C2.57, M3.32, M195.ECL2, W6.48) (Figure 5).

For photodynamic CCK1R activation, we need to examine only critical residues that are also susceptible to 1O2 oxidation. Among the 1O2-susceptible residues Met, Trp, Cys, His, and Tyr [22,82,83], Met oxidation and Met(O) reduction by methionine sulfoxide reductase (Msr), in particular, has been associated with finely tuned functional protein activities and related physiological functions [33]. Permanent photodynamic CCK1R activation by 1O2 with both SALPC and miniSOG may be associated with residues critical for agonist-stimulated CCK1R activation [84,85,86,87,88]. Such critical residues also susceptible to 1O2 oxidation are Cys94/2.57, Met121/3.32, Met195.ECL2, Trp326/6.48, and Tyr360/7.43. Of these five residues, Cys94/2.57, Trp326/6.48, and Tyr360/7.43 are conserved in the human, rat, mouse, and Peking duck CCK1R (Figure 5).

We have found previously that TM3, especially the Y3.30F3.31M3.32 motif in the human CCK1R, is a pharmacophore for photodynamic CCK1R activation in fusion construct miniSOG-CCK1R [28]. Alignment of TM3 sequences of CCK1R revealed a consensus sequence of Y3.30F3.31M3.32 in the human, rat, mouse, and Peking duck CCK1R; the corresponding motif in the refractory human ACh M3R is A3.30I3.31D3.32 (Figure 5).

Vertebrate CCK1R structures modeled after the human structure show almost complete overlap, but note the varied size of ICL3 of CCK1R from different species, as noted previously (Figure 6) [31]. Five structural motifs critically involved in agonist-stimulated activation of GPCR, including the human CCK1R, are as follows: Na+ pocket [D87/2.50S128/3.39S332/7.45N366/7.49], transmission switches [C325/6.47W326/6.48xP328/6.50] and [P221/5.50T129/3.40F322/6.44], ionic lock switch [E138/3.49R139/3.50Y140/3.51], ionic lock [R139/3.50 to K6.30], and Tyr toggle switch [N366/7.49P367/7.50xxY370/7.53] [76,89,90,91]. The DSSN, CWxP, ERY, RK, and NPxxY motifs for agonist-stimulated human CCK1R activation are identical to the CCK1R of rat, mouse, and Peking duck. Although it is not known yet whether these motifs involved in agonist-stimulated GPCR activation are important for photodynamic CCK1R activation, the 1O2-susceptible Met121/3.32 and Met195.ECL2, as mentioned above, might be relevant due to the sulfur–aromatic interactions of Met.

Met interacts with aromatic residues within a distance of 7 Å, known as sulfur–aromatic interaction [92]. Met residue may bridge with one or two aromatic residues [93], such as F31-M72-Y19 in human estrogen receptor [94], W578-M585-Y436 in lipoxygenase (at 3.8 Å, 3.9 Å) [95], M144-F141 in calmodulin [96], F214-M181-Y198 in inositol polyphosphate kinase (PDB: 6C8A) (F214-M181 at 4.6 Å; Y198-M181 at 4.5 Å), and Y34-M37-F55 in human ferritin (PDB: 2FHA) [94], to stabilize the protein structures or to facilitate ligand–receptor binding [92,97].

In the human CCK1R-antagonist complex structure, aromatic residues within 7 Å from M3.32 include Y7.43, W6.48, and F6.52; therefore, interactions of W6.48-M3.32-W6.52 [91] may exist in the resting CCK1R (Figure 5). In CCK-activated human CCK1R [76], the distance between M3.32 and the nearby aromatic residues increased, interaction between M3.32 and W6.48 or F6.52 disappeared, and M3.32 interaction with Y7.43 also weakened, possibly due to the binding of G protein [91]. Oxidized Met becomes more hydrophilic, increasing the Met-aromatic bridge strength by 0.5–1.4 kCal/mol [96]. Met144 replacement by glutamine (Q) in calmodulin (to simulate oxidation) is known to increase the frequency of native interaction between M/Q144 and F141 from 12% to 49%, decreasing the distance from 11.2 to 5.1 Å [96], whereas Met109 replacement in calmodulin by glutamine (Q) increases the interactions of M109-F141 and M124-F141 to stabilize the Ca2+-saturated state of calmodulin [98]. Met230 oxidation of cytochrome C peroxidase is known to result in a stronger interaction of Met230-Trp191 (distance between Met and W pyrrole ring C atom decreasing by 0.2 Å) [93]. M3.32 oxidation of CCK1R may similarly result in enhanced interactions between M3.32 and W6.48 or F6.52. Such covalent changes would be different from agonist-stimulated receptor activation, therefore leading to permanent photodynamic activation.

The CCK1R protein isolated from rat pancreatic acini was found previously to be converted from dimer to monomer, near quantitatively, after SALPC photodynamic oxidative activation [24]. TM6 is known to be important for the formation of CCK1R dimers due to the existence of a hydrophobic interface consisting of aliphatic I6.38, V6.42, and L6.46 [99]. The corresponding M6.38, I6.42, and L6.46 in Peking duck CCK1R may imply that the Peking duck CCK1R be slightly different in terms of receptor dimerization from mammalian CCK1R (Figure 5). Met oxidation to MetO by 1O2 generated in type II photodynamic action may strengthen interactions between Met3.32 and W6.48 or F6.52, this two-bridge interaction (W6.48-Met3.32-F6.52) might break the nearby hydrophobic interface formed by the hydrophobic residues (I6.38, V6.42, L6.46) between two CCK1R protein molecules, to promote monomer formation, at least in the human, rat, and mouse CCK1R. Importantly, other than Met3.32, W6.48 and F6.52 are also conserved in the human, rat, mouse, and Peking duck CCK1R, and the three aliphatic residues at the corresponding positions of CCK1R are human, rat, and mouse—IVL, Peking duck—MIL. Other than the aromatic F, all other residues are hydrophobic (aliphatic) residues. Met3.32 photodynamic oxidation or evolution to Q3.32 would help to break such hydrophobic interface, resulting in CCK1R dimer-to-monomer conversion that has been observed experimentally with rat pancreatic acinar cell CCK1R [24]. Further, the varied length of disordered region in ICL3 of the human, rat, mouse, and Peking duck CCK1R may exert a graded effect on the monomerization process, related to the disordered region-regulated liquid phase separation of proteins [31,100]. In sharp contrast to the agonist stimulation- and photodynamic action-induced CCK1R monomerization [24], muscarinic receptor agonist carbachol seems to stimulate dimerization/oligomerization of both human [101] and rat [102] muscarinic ACh M3R.

In conclusion, the human, rat, mouse, and Peking duck CCK1R are all photodynamically activated outside of the pancreatic acinar cell plasma membrane microenvironment. In contrast, the human ACh M3R are unaffected by photodynamic action. It is noteworthy that, other than M(Q)121/3.32, M(K/T)195.ECL2), 1O2-susceptible critical residues C2.57, W6.48 and Y7.43 are all conserved in all these vertebrate species examined. The Y3.30F3.31M3.32 triplet in the human, rat, mouse, and Peking duck CCK1R is of particular interest. The fact that permanent photodynamic activation of CCK1R is maintained outside of the plasma membrane microenvironment of the pancreatic acinar cells suggests that photodynamic activation of CCK1R could be used to study CCK1R physiology, pharmacology, and probably therapeutics in organs and tissues other than the exocrine pancreas, with inherent spatiotemporal precision and specificity that are associated with genetically encoded protein photosensitizers, genetically guided photobiophysics [103,104,105], and other related biotechnologies [106,107,108,109].

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

Sulfated cholecystokinin octapeptide (CCK, #1166) was from Tocris Cookson (Bristol, UK). MEM amino acid mixture (50×, #11130051), trypsin 0.25% (#25200056), fetal bovine serum (FBS, #10099141), and cell culture medium mix DMEM/F12 (#11320033) were from Thermo Scientific (Shanghai, China). Fura-2 AM (#21020) was from AAT Bioquest (Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Goat anti-CCK1R antibody (#ab77269) and tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate (TRITC)-conjugated donkey anti-goat secondary antibody (#ab6738), rabbit anti-M3R primary antibody (#ab41169), and TRITC-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit secondary antibody (#ab7080) were all from Abcam (Cambridge, UK). JetPRIME® transfection reagent (#114-07) was from Polyplus-Transfection (Illkirch, France). Cell-Tak (#354241) was from BD Bioscience (Bedford, MA, USA). Plasmid extraction kit (#4992422) was from TianGen Biochemicals (Beijing, China). Sulfonated aluminum phthalocyanine (SALPC, #AlPcS 834) was from Frontier Scientific (West Logan, UT, USA). Hoechst 33342 (#H342) was from DojinDo (Beijing, China). Plasmids pcDNA3.1+/hCCK1R (GenBank accession number AY322549, #CCKAR00000) and pcDNA3.1+/hM3R (GenBank accession number X15266, (#MAR00000) were from cDNA Resource Center (Rolla, MO, USA). HiPure Total RNA Plus Mini Kit (#R4121-02) was from Magen (Guangzhou, China). 2×Taq Master Mix (#P112-01) was from Vazyme (Nanjing, China). GoScript Reverse Transcription Kit (#238813) was from Promega (Shanghai, China). Trolox C (#238813), acetylcholine (ACh, #A6625) and soybean trypsin inhibitor (#T9128) were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). GoldView (#GV-2) was from SaiBaiSheng (Beijing, China).

Ringer’s buffer had the following composition (in mM): NaCl 118, KCl 4.7, CaCl2 2.5, MgCl2 1.13, NaH2PO4 1.0, D-glucose 5.5, HEPES 10, L-glutamine 2.0, and BSA 20 g·L−1, MEM amino acid mixture (50×) 2%, soybean trypsin inhibitor 0.1 g·L−1, pH adjusted to 7.4 with 4 M NaOH and oxygenated with pure O2. BSA, amino acid mixture, and soybean trypsin inhibitor were omitted for perifusion during calcium imaging.

4.2. Cell Culture

Chinese hamster ovary K1 (CHO-K1) cells purchased from Shanghai Institute of Life Sciences, Chinese Academy of Sciences were cultured in DMEM/F12 (1:1), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco, Shanghai, China) in a CO2 incubator under 5% CO2 at 37 °C.

4.3. Vector Constructs and CHO-K1 Cell Transfection

The human CCK1R and human M3R plasmids phM3R pcDNA3.1+/hCCK1R and pcDNA3.1+/hM3R were bought from the cDNA Resource Center (Bloomsburg, PA, USA). The rat rCCK1R (NM_012688.3), mouse mCCK1R (NM_009827.2), and Peking duck dCCK1R (MN250295.1) genes were mammalian code-optimized and synthesized by Genscript (Nanjing, China) for the construction of plasmid with pCCK1R-3.1+.

Mammalian codon-optimized miniSOG (GenBank accession number JX999997) was synthesized from nucleotides (Genscript, Nanjing, China). The miniSOG sequence: ATGGAGAAGTCTTTCGTGATCACCGACCCCAGGCTGCTGATAACCCAATCATCTT CGCCTCCGACGGCTTTCTGGAGCTGACAGAGTACAGCCGGGAGGAGATCCTGGG CAGGAATGGCCGGTTTCTGCAGGGCCCCGAGACCGATCAGGCCACAGTGCAGA AGATCAGAGACGCTATCAGAGATCAGCGCGAGATCACCGTGCAGCTGATCAAC TACACAAAGTCCGGCAAGAAGTTCTGGAATCTGCTGCACCTGCAGCCCATGCGC GACCAGAAGGGCGAGCTGCAGTACTTCATCGGCGTGCAGCTGGATGGCTGA. For the construction of fused plasmids pCCK1R-miniSOG, phM3R-miniSOG, this miniSOG sequence was amplified and ligated to 3′ end of the receptor (CCK1R, M3R) open reading frame in vectors pCCK1R-3.1+ or phM3R (Genscript, Nanjing, China).

Plasmids obtained as described above were used to transfect CHO-K1 cells. A predetermined amount of each plasmid (2 µg DNA) was mixed in transfection buffer (200 µL) before addition of the transfection reagent (jetPRIME®, 4 µL of stock). The mixture was allowed to sit for 10 min at room temperature before use. CHO-K1 cells were planted in each culture plate (35 mm) and, 24 h later, 200 µL of the above transfection mixture (containing plasmid and transfection reagent jetPRIME®) was added. Transfected CHO-K1 cells were used for immunocytochemistry and for calcium imaging 24 h after transfection.

4.4. Immunocytochemistry

Parental CHO-K1 cells were planted on the glass cover-slips and cultured overnight before transfection, as shown above. At 24 h after transfection, CHO-K1 cells expressing the human, rat, mouse, Peking duck CCK1R or human, rat, mouse, Peking duck receptor construct CCK1R-miniSOG, human M3R, human receptor construct M3R-miniSOG were fixed, permeabilized, and blocked for immunocytochemistry. Cells were counter-stained with Hoechst 33342 for 15 min after incubation with secondary antibodies. Stained cells were imaged in a confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM710, Jena, Germany), under oil objective 63×/1.40, with λex for Hoechst 33342 at 405 nm; λex for TRITC (CCK1R or M3R) at 543 nm; and λex for miniSOG at 488 nm.

4.5. Photodynamic Treatment

Parental CHO-K1 cells, CCK1R-CHO-K1, M3R-CHO-K1 cells were incubated with photosensitizer SALPC (1 or 2 μM, 10 min), before washing out and irradiation with red LED 675 nm (60, 50, 45, 40 mW·cm−2, 1.5 min). Parental CHO-K1 cells, CCK1R-miniSOG-CHO-K1, and hM3R-miniSOG-CHO-K1 cells were irradiated with blue LED 450 nm (85 mW·cm−2, 1.5 min).

LED light source was from LAMPLIC, with appropriate light head (675 nm or 450 nm) attached (Shenzhen, China). The irradiation light power density used was determined at the level of attached cells in the Sykes-Moore perfusion chamber with a power meter as reported previously (IL1700, International Light Inc., Newburyport, MA, USA) [25,26,27,28,31].

4.6. Calcium Imaging

Cells were loaded with Fura-2 AM (10 µM) in a shaking bath (37 °C, 30 min, 50 cycles per min) and then attached to the bottom cover-slip (coated with Cell-Tak, 1.74 g·L−1, 3 µL on each cover-slip) of Sykes-Moore perfusion chambers for at least 30 min before perifusion and experimentation.

The cell-attached perifusion chamber was placed on the platform of a Nikon NE 3000 inverted fluorescence microscope connected to the calcium imaging device (Photon Technology International, PTI, Edison, NJ, USA) with alternating excitations at 340 nm/380 nm (monochromator DeltaRam X, PTI). Emission (emitter 510 ± 40 nm) was detected with a CCD (NEO-5.5-CL-3, Andor/Oxford Instruments, Belfast, UK). The fluorescence ratios F340/F380 indicative of cytosolic calcium concentrations were plotted against time with SigmaPlot (version 15.0), as reported previously [21,24,25,26,27,28,31,110,111,112,113].

4.7. Data Analyses

All data are presented as mean ± SEM (standard error of means). The Student’s t-test was performed for comparison between control and experimental groups. Statistical significance at p < 0.05 is indicated by an asterisk (*).

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijms262412011/s1.

Author Contributions

Z.-J.C. conceived the idea of the project, supervised the experimentations, and revised the final versions of the MS. J.W. performed the experiments, analyzed data, and wrote the initial drafts. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by grants to Z.-J.C. from The Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC, Nos. 32271278, 31971170).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We thank Xiao Bing Xie for assistance with the SigmaPlot software.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

| ACh | Acetylcholine |

| AlPcS4 | Sulphonated (4) aluminum phthalocyanine |

| CCD | Charge coupled device |

| CCK1R | Cholecystokinin 1 receptor |

| CHO | Chinese hamster ovary cells |

| dCCK1R | Duck cholecystokinin 1 receptor |

| ECL | Extracellular loop |

| ER | Endoplasmic reticulum |

| ERES | Endoplasmic reticulum exit sites |

| FBS | Fetal bovine serum |

| GPCR | G protein coupled receptor |

| GPCR-ABSO | G protein coupled receptor activated by singlet oxygen |

| GEPP | Genetically encoded protein photosensitizer |

| hCCK1R | Human cholecystokinin 1 receptor |

| HEK293 | Human embryonic kidney cell line 293 |

| hM3R | Human type 3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor |

| ICL | Intracellular loop |

| LED | Light emission diode |

| M3R | Type 3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor |

| miniSOG | mini singlet oxygen generator |

| mCCK1R | Mouse cholecystokinin 1 receptor |

| Msr | Methionine sulfoxide reductase |

| MEM | Minimum essential medium |

| PDB | Photodynamic biology; Protein Data Bank |

| PTI | Photon Technology International Inc. |

| 1O2 | Singlet oxygen |

| pCCK1R | Peking duck cholecystokinin 1 receptor |

| rCCK1R | Rat cholecystokinin 1 receptor |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| SALPC | Sulphonated aluminum phthalocyanine |

| SEM | Standard error of means |

| TM | Transmembrane domain |

| TRITC | Tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate |

References

- Alexander, S.P.H.; Kelly, E.; Mathie, A.A.; Peters, J.A.; Veale, E.L.; Armstrong, J.F.; Buneman, O.P.; Faccenda, E.; Harding, S.D.; Spedding, M.; et al. The concise guide to pharmacology 2023/24: Introduction and other protein targets. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2023, 180(SI 2), S1–S22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alexander, S.P.H.; Christopoulos, A.; Davenport, A.P.; Kelly, E.; Mathie, A.A.; Peters, J.A.; Veale, E.L.; Armstrong, J.F.; Faccenda, E.; Harding, S.D. The concise guide to pharmacology 2023/24: G protein-coupled receptors. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2023, 180, S23–S144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Congreve, M.; de Graaf, C.; Swain, N.A.; Tate, C.G. Impact of GPCR structures on drug discovery. Cell 2020, 181, 81–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hauser, A.S.; Chavali, S.; Masuho, I.; Jahn, L.J.; Martemyanov, K.A.; Gloriam, D.E.; Babu, M.M. Pharmacogenomics of GPCR drug targets. Cell 2018, 172, 41–54.e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, P.; Scharf, M.M.; Bermudez, M.; Egyed, A.; Franco, R.; Hansen, O.K.; Jagerovic, N.; Jakubík, J.; Keserű, G.M.; Kiss, D.J.; et al. Progress on the development of class A GPCR-biased ligands. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2025, 182, 3249–3300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.J. To activate a G protein coupled receptor permanently by cell surface photodynamic action in the gastrointestinal tract. World J. Gastroenterol. 2025, 31, 102423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, E.K.; Cui, Z.J. Photodynamic action of sulphonated aluminium phthalocyanine (SALPC) on isolated rat pancreatic acini. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1990, 39, 1445–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brennan, S.C.; Mun, H.C.; Delbridge, L.; Kuchel, P.W.; Conigrave, A.D. Temperature sensing by the calcium-sensing receptor. Front. Physiol. 2023, 14, 1117352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohnishi, K.; Sokabe, T.; Miura, T.; Tominaga, M.; Ohta, A.; Kuhara, A. G protein-coupled receptor-based thermosensation determines temperature acclimatization of Caenorhabditis elegans. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 1660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Cerezales, S.; Boryshpolets, S.; Afanzar, O.; Brandis, A.; Nevo, R.; Kiss, V.; Eisenbach, M. Involvement of opsins in mammalian sperm thermotaxis. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 16146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Tong, F.; Zhou, B.; He, M.D.; Liu, S.; Zhou, X.M.; Ma, Q.; Feng, T.Y.; Du, W.J.; Yang, H.; et al. TMC6 functions as a GPCR-like receptor to sense noxious heat via Gαq signaling. Cell Discov. 2025, 10, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harikumar, K.G.; Puri, V.; Singh, R.D.; Hanada, K.; Pagano, R.E.; Miller, L.J. Differential effects of modification of membrane cholesterol and sphingolipids on the conformation, function, and trafficking of the G protein-coupled cholecystokinin receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 2176–2185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harikumar, K.G.; Zhao, P.; Cary, B.P.; Xu, X.; Desai, A.J.; Dong, M.; Mobbs, J.I.; Toufaily, C.; Furness, S.G.B.; Christopoulos, A.; et al. Cholesterol-dependent dynamic changes in the conformation of the type 1 cholecystokinin receptor affect ligand binding and G protein coupling. PLoS Biol. 2024, 22, e3002673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christofidi, M.; Tzortzini, E.; Mavromoustakos, T.; Kolocouris, A. Effects of membrane cholesterol on the structure and function of selected class A GPCRs—Challenges and future perspectives. Biochemsitry 2025, 64, 4011–4049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, D.; Bentulila, Z.; Tauber, M.; Ben-Chaim, Y. G protein-coupled receptors regulated by membrane potential. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 13988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tauber, M.; Ben-Chaim, Y. Voltage sensors embedded in G protein-coupled receptors. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 5295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.J.C.; Zhou, Y.; Cao, C. Thermodynamics of GPCR activation. Biophys. Rep. 2015, 1, 115–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.J.C.; Zhou, Y.; Cao, C. Proton transfer during class-A GPCR activation: Do the CWxP motif and the membrane potential act in concert? Biophys. Rep. 2018, 4, 115–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezanilla, F. How membrane proteins sense voltage. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2008, 9, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.Y.; Song, Z.M.; Cui, Z.J. Lasting inhibition of receptor-mediated calcium oscillations in pancreatic acini by neutrophil respiratory burst--a novel mechanism for secretory blockade in acute pancreatitis? Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2013, 437, 361–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, Y.P.; Xiao, R.; Cui, H.; Cui, Z.J. Selective activation by photodynamic action of cholecystokinin receptor in the freshly isolated rat pancreatic acini. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2003, 139, 872–880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.N.; Li, Y.; Cui, Z.J. Photodynamic physiology-photonanomanipulations in cellular physiology with protein photosensitisers. Front. Physiol. 2017, 8, 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.N.; Li, Y.; Jiang, W.Y.; Cui, Z.J. Cholecystokinin 1 receptor—A unique G protein-coupled receptor activated by singlet oxygen (GPCR-ABSO). Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, W.Y.; Li, Y.; Li, Z.Y.; Cui, Z.J. Permanent photodynamic cholecystokinin 1 receptor activation: Dimer-to-monomer conversion. Cell Mol. Neurobiol. 2018, 38, 1283–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Cui, Z.J. NanoLuc bioluminescence-driven photodynamic activation of cholecystokinin 1 receptor with genetically-encoded protein photosensitizer miniSOG. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Cui, Z.J. Photogenetical activation of cholecystokinin 1 receptor with different genetically encoded protein photosensitizers and from varied subcellular sites. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Cui, Z.J. Photodynamic activation of the cholecystokinin 1 receptor with tagged genetically encoded protein photosensitizers: Optimizing the tagging patterns. Photochem. Photobiol. 2022, 98, 1215–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Cui, Z.J. Transmembrane domain 3 is a transplantable pharmacophore in the photodynamic activation of cholecystokinin 1 receptor. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2022, 5, 539–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.J. Photodynamic vision at low light level—what is more important, the prethetic retinal or the apo-rhodopsin moiety? FASEB J 2025, 39, e70470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.J.; Kanno, T. Photodynamic triggering of calcium oscillation in the isolated rat pancreatic acini. J. Physiol. 1997, 504, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Cui, Z.J. Photodynamic activation of cholecystokinin 1 receptor is conserved in mammalian and avian pancreatic acini. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.J.; Matthews, E.K. Photodynamic modulation of cellular function. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 1998, 19, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cui, Z.J.; Han, Z.Q.; Li, Z.Y. Modulating protein activity and cellular function by methionine residue oxidation. Amino Acids 2012, 43, 505–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, Z.J. GPCR-ABSO—G protein coupled receptor activated by singlet oxygen. J. Beijing Normal Univ. (Nat. Sci.) 2020, 56, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, W.Z.; Cui, Z.J. Permanent photodynamic activation of the cholecystokinin 2 receptor. Biomolecules 2020, 10, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.J.; Cui, Z.J. How does cholecystokinin stimulate exocrine pancreatic secretion? From birds, rodents, to humans. Am. J. Physiol. Reg. Integr. Physiol. 2007, 292, R666–R678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regard, J.B.; Sato, I.T.; Coughlin, S.R. Anatomical profiling of G protein-coupled receptor expression. Cell 2008, 135, 561–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- South, E.H.; Ritter, R.C. Capsaicin application to central or peripheral vagal fibers attenuates CCK satiety. Peptides 1988, 9, 601–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, R.C.; Brenner, L.A.; Tamura, C.S. Endogenous CCK and the peripheral neural substrates of intestinal satiety. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1994, 713, 255–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degen, L.; Matzinger, D.; Drewe, J.; Beglinger, C. The effect of cholecystokinin in controlling appetite and food intake in humans. Peptides 2001, 22, 1265–1269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berna, M.J.; Jensen, R.T. Role of CCK/gastrin receptors in gastrointestinal/metabolic diseases and results of human studies using gastrin/CCK receptor agonists/antagonists in these diseases. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2007, 7, 1211–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishimura, S.; Bilgüvar, K.; Ishigame, K.; Sestan, N.; Günel, M.; Louvi, A.; Lei, S. Functional synergy between cholecystokinin receptors CCKAR and CCKBR in mammalian brain development. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0124295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, T.; Dolai, S.; Xie, L.; Winter, E.; Orabi, A.I.; Karimian, N.; Cosen-Binker, L.I.; Huang, Y.C.; Thorn, P.; Cattral, M.S.; et al. Ex vivo human pancreatic slice preparations offer a valuable model for studying pancreatic exocrine biology. J. Biol. Chem. 2017, 292, 5957–5969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pathak, V.; Flatt, P.R.; Irwin, N. Cholecystokinin (CCK) and related adjunct peptide therapies for the treatment of obesity and type 2 diabetes. Peptides 2018, 100, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyborg, N.C.B.; Kirk, R.K.; de Boer, A.S.; Andersen, D.W.; Bugge, A.; Wulff, B.S.; Thorup Inger Clausen, T.R. Cholecystokinin-1 receptor agonist induced pathological findings in the exocrine pancreas of non-human primates. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 2020, 399, 115035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, C.C.; Davidson, W.S.; Hibbard, S.K.; Georgievsky, M.; Lee, A.; Tso, P.; Woods, S.C. Intraperitoneal CCK and fourth-intraventricular Apo AIV require both peripheral and NTS CCK1R to reduce food intake in male rats. Endocrinology 2014, 155, 1700–1707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kageyama, H.; Kita, T.; Horie, S.; Takenoya, F.; Funahashi, H.; Kato, S.; Hirayama, M.; Lee, E.Y.; Sakurai, J.; Inoue, S.; et al. Immunohistochemical analysis of cholecystokinin A receptor distribution in the rat pancreas. Regul. Pept. 2005, 126, 137–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moralejo, D.H.; Ogino, T.; Kose, H.; Yamada, T.; Matsumoto, K. Genetic verification of the role of CCK-AR in pancreatic proliferation and blood glucose and insulin regulation using a congenic rat carrying CCK-AR null allele. Res. Commun. Mol. Pathol. Pharmacol. 2001, 109, 259–274. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Peitl, B.; Dobronte, R.; Drimba, L.; Sari, R.; Varga, A.; Nemeth, J.; Pazmany, T.; Szilvassy, Z. Involvement of cholecystokinin in baseline and post-prandial whole body insulin sensitivity in rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2010, 644, 251–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plaza, A.; Merino, B.; Cano, V.; Dominguez, G.; Perez-Castells, J.; Fernandez-Alfonso, M.S.; Sengenes, C.; Chowen, J.A.; RuizGayo, M. Cholecystokinin is involved in triglyceride fatty acid uptake by rat adipose tissue. J. Endocrinol. 2018, 236, 137–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avirineni, B.S.; Singh, A.; Zapata, R.C.; Phillips, C.D.; Chelikani, P.K. Dietary whey and egg proteins interact with inulin fiber to modulate energy balance and gut microbiota in obese rats. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2022, 99, 108860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimazoe, T.; Morita, M.; Ogiwara, S.; Kojiya, T.; Goto, J.; Kamakura, M.; Moriya, T.; Shinohara, K.; Takiguchi, S.; Kono, A.; et al. Cholecystokinin-A receptors regulate photic input pathways to the circadian clock. FASEB J. 2008, 22, 1479–1490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshimichi, G.; Lo, C.C.; Tamashiro, K.L.; Ma, L.; Lee, D.M.; Begg, D.P.; Liu, M.; Sakai, R.R.; Woods, S.C.; Yoshimatsu, H.; et al. Effect of peripheral administration of cholecystokinin on food intake in apolipoprotein AIV knockout mice. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2012, 302, G1336–G1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Ohta, H.; Izumi, H.; Matsuda, Y.; Seki, M.; Toda, T.; Akiyama, M.; Matsushima, Y.; Goto, Y.; Kaga, M.; et al. Behavioral and cortical EEG evaluations confirm the roles of both CCKA and CCKB receptors in mouse CCK induced anxiety. Behav. Brain Res. 2013, 237, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.G.; Liu, J.X.; Jia, X.X.; Geng, J.; Yu, F.; Cong, B. Cholecystokinin octapeptide regulates the differentiation and effector cytokine production of CD4+ T cells in vitro. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2014, 20, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takiguchi, S.; Suzuki, S.; Sato, Y.; Kanai, S.; Miyasaka, K.; Jimi, A.; Shinozaki, H.; Takata, Y.; Funakoshi, A.; Kono, A.; et al. Role of CCK-A receptor for pancreatic function in mice: A study in CCK-A receptor knockout mice. Pancreas 2002, 24, 276–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Sinovas, A.; Fernández, E.; Manteca, X.; Fernández, A.G.; Goñalons, E. CCK is involved in both peripheral and central mechanisms controlling food intake in chickens. Am. J. Physiol. 1997, 272, R334–R340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degolier, T.F.; Brown, D.R.; Duke, G.E.; Palmer, M.M.; Swenson, J.R.; Carraway, R.E. Neurotensin and cholecystokinin contract gallbladder circular muscle in chickens. Poult. Sci. 2013, 92, 2156–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Kassas, S.; Odemuyiwa, S.; Hajishengallis, G.; Connell, T.D.; Nashar, T.O. Expression and regulation of cholecystokinin receptor in the chicken’s immune organs and cells. J. Clin. Cell Immunol. 2016, 7, 471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, I.C.; Meddle, S.L.; Wilson, P.W.; Wardle, C.A.; Law, A.S.; Bishop, V.R.; Hindar, C.; Robertson, G.W.; Burt, D.W.; Ellison, S.J.; et al. Decreased expression of the satiety signal receptor CCKAR is responsible for increased growth and body weight during the domestication of chickens. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 304, E909–E921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, R.; Cui, Z.J. Mutual dependence of VIP/PACAP and CCK receptor signaling for a physiological role in duck exocrine pancreatic secretion. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2003, 286, R189–R198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, M.; Zhao, S.; Liu, W.; Lee, C.; Zhang, W.; Wang, P. Photosensitizers for photodynamic therapy. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2019, 8, e1900132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allison, R.R.; Sibata, C.H. Oncologic photodynamic therapy photosensitizers: A clinical review. Photodiagn. Photodyn. Ther. 2010, 7, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matthews, E.K.; Cui, Z.J. Photodynamic action of sulphonated aluminium phthalocyanine (SALPC) on AR4-2J cells, a carcinoma cell line of rat exocrine pancreas. Br. J. Cancer 1990, 61, 695–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al-Laith, M.; Matthews, E.K.; Cui, Z.J. Photodynamicdrug action on isolated rat pancreatic acini. Mobilization of arachidonic acid and prostaglandin production. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1993, 46, 567–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Westberg, M.; Bregnhøj, M.; Etzerodt, M.; Ogilby, P.R. Temperature sensitive singlet oxygen photosensitization by LOV-derived fluorescent flavoproteins. J. Phys. Chem. B 2017, 121, 2561–2574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitasaka, S.; Yagi, M.; Kikuchi, A. Suppression of menthyl anthranilate (UV-A sunscreen)-sensitized singlet oxygen generation by Trolox and α-tocopherol. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2020, 19, 913–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giordano, M.E.; Caricato, R.; Lionetto, M.G. Concentration dependence of the antioxidant and prooxidant activity of Trolox in HeLa cells: Involvement in the induction of apoptotic volume decrease. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 1058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, F.S.; Wang, Q.; Han, J.Z.; Goswamee, P.; Gupta, A.; McQuiston, A.R.; Liu, Q.L.; Zhou, L. Photodynamic modification of native HCN channels expressed in thalamocortical neurons. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2020, 11, 851–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meza, U.; Delgado-Ramírez, M.; Romero-Méndez, C.; Sánchez-Armass, S.; Rodríguez-Menchaca, A.A. Functional marriage in plasma membrane: Critical cholesterol level-optimal protein activity. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 177, 2456–2465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girotti, A.W.; Korytowski, W. Cholesterol as a singlet oxygen detector in biological systems. Methods Enzymol. 2000, 319, 85–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oasa, S.; Mak, W.H.; Maddox, A.L.; Lima, C.; Saftics, A.; Terenius, L.; Jovanović-Talisman, T.; Vukojević, V. Effects of ethanol and opioid receptor antagonists naltrexone and LY2444296 on the organization of cholesterol- and sphingomyelin-enriched plasma membrane domains. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2025, 16, 4133–4146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiménez-Rojo, N.; Feng, S.H.; Morstein, J.; Pritzl, S.D.; Asaro, A.; López, S.; Xu, Y.; Harayama, T.; Vepřek, N.A.; Arp, C.J.; et al. Optical control of membrane viscosity modulates ER-to-Golgi trafficking. ACS Cent. Sci. 2025, 11, 1736–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Archer-Lahlou, E.; Escrieut, C.; Clerc, P.; Martinez, J.; Moroder, L.; Logsdon, C.; Kopin, A.; Seva, C.; Dufresne, M.; Pradayrol, L.; et al. Molecular mechanism underlying partial and full agonism mediated by the human cholecystokinin-1 receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 10664–10674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, N.; Smagghe, G. CCK(-like) and receptors: Structure and phylogeny in a comparative perspective. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2014, 209, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.F.; Yang, D.H.; Zhuang, Y.W.; Croll, T.I.; Cai, X.Q.; Dai, A.T.; He, X.H.; Duan, J.; Yin, W.C.; Ye, C.Y.; et al. Ligand recognition and G-protein coupling selectivity of cholecystokinin A receptor. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2021, 17, 1238–1244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wess, J.; Blin, N.; Mutschler, E.; BlumL, K. Muscarinic acetylcholine receptors: Structural basis of ligand binding and G protein coupling. Life Sci. 1995, 56, 915–922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballesteros, J.A.; Weinstein, H. Integrated methods for the construction of three-dimensional models and computational probing of structure-function relations in G protein-coupled receptors. Methods Neurosci. 1995, 25, 366–428. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Archundia, M.; Cordomi, A.; Garriga, P.; Perez, J.J. Molecular modeling of the M3 acetylcholine muscarinic receptor and its binding site. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2012, 2012, 789741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruse, A.C.; Hu, J.; Pan, A.C.; Arlow, D.H.; Rosenbaum, D.M.; Rosemond, E.; Green, H.F.; Liu, T.; Chae, P.S.; Dror, R.O.; et al. Structure and dynamics of the M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor. Nature 2012, 482, 552–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruse, A.C.; Li, J.; Hu, J.; Kobilka, B.K.; Wess, J. Novel insights into M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor physiology and structure. J. Mol. Neurosci. 2014, 53, 316–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pattison, D.I.; Rahmanto, A.S.; Davies, M.J. Photo-oxidation of proteins. Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2012, 11, 38–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, M.J. Protein oxidation and peroxidation. Biochem. J. 2016, 473, 805–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foucaud, M.; Archer-Lahlou, E.; Marco, E.; Tikhonova, I.G.; Maigret, B.; Escrieut, C.; Langer, I.; Fourmy, D. Insights into the binding and activation sites of the receptors for cholecystokinin and gastrin. Regul. Pept. 2008, 145, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, L.J.; Gao, F. Structural basis of cholecystokinin receptor binding and regulation. Pharmacol. Ther. 2008, 119, 83–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigoux, V.; Escrieut, C.; Fehrentz, J.A.; Poirot, S.; Maigret, B.; Moroder, L.; Gully, D.; Martinez, J.; Vaysse, N.; Fourmy, D. Arginine 336 and asparagine 333 of the human cholecystokinin-A receptor binding site interact with the penultimate aspartic acid and the C-terminal amide of cholecystokinin. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 20457–20464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escrieut, C.; Gigoux, V.; Archer, E.; Verrier, S.; Maigret, B.; Behrendt, R.; Moroder, L.; Bignon, E.; Silvente-Poirot, S.; Pradayrol, L.; et al. The biologically crucial C terminus of cholecystokinin and the non-peptide agonist SR-146,131 share a common binding site in the human CCK1 receptor. Evidence for a crucial role of Met-121 in the activation process. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 7546–7555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer-Lahlou, E.; Tikhonova, I.; Escrieut, C.; Dufresne, M.; Seva, C.; Pradayrol, L.; Moroder, L.; Maigret, B.; Fourmy, D. Modeled structure of a G-protein-coupled receptor: The cholecystokinin-1 receptor. J. Med. Chem. 2005, 48, 180–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Yang, D.; Wu, M.; Guo, Y.; Guo, W.; Zhong, L.; Cai, X.; Dai, A.; Jang, W.; Shakhnovich, E.I.; et al. Common activation mechanism of class A GPCRs. eLife 2019, 8, e50279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mobbs, J.I.; Belousoff, M.J.; Harikumar, K.G.; Piper, S.J.; Xu, X.M.; Furness, S.G.B.; Venugopal, H.; Christopoulos, A.; Danev, R.; Wootten, D.; et al. Structures of the human cholecystokinin 1 (CCK1) receptor bound to Gs and Gq mimetic proteins provide insight into mechanisms of G protein selectivity. PLoS Biol. 2021, 19, e3001295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.F.; He, C.L.; Wang, M.; Zhou, Q.T.; Yang, D.H.; Zhu, Y.; Feng, W.B.; Zhang, H.; Dai, A.T.; Chu, X.J.; et al. Structures of the human cholecystokinin receptors bound to agonists and antagonists. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2021, 17, 1230–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valley, C.C.; Cembran, A.; Perlmutter, J.D.; Lewis, A.K.; Labello, N.P.; Gao, J.; Sachs, J.N. The methionine-aromatic motif plays a unique role in stabilizing protein structure. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 34979–34991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, D.S.; Warren, J.J. A survey of methionine-aromatic interaction geometries in the oxidoreductase class of enzymes: What could Met-aromatic interactions be doing near metal sites? J. Inorg. Biochem. 2018, 186, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weber, D.S.; Warren, J.J. The interaction between methionine and two aromatic amino acids is an abundant and multifunctional motif in proteins. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2019, 672, 108053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray, H.B.; Winkler, J.R. Hole hopping through tyrosine/tryptophan chains protects proteins from oxidative damage. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 10920–10925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, A.K.; Dunleavy, K.M.; Senkow, T.L.; Her, C.; Horn, B.T.; Jersett, M.A.; Mahling, R.; McCarthy, M.R.; Perell, G.T.; Valley, C.C.; et al. Oxidation increases the strength of the methionine-aromatic interaction. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2016, 12, 860–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, K.S.; Das, R. An “up” oriented methionine-aromatic structural motif in SUMO is critical for its stability and activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2021, 297, 100970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walgenbach, D.G.; Gregory, A.J.; Klein, J.C. Unique methionine-aromatic interactions govern the calmodulin redox sensor. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 505, 236–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harikumar, K.G.; Dong, M.; Cheng, Z.; Pinon, D.I.; Lybrand, T.P.; Miller, L.J. Transmembrane segment peptides can disrupt cholecystokinin receptor oligomerization without affecting receptor function. Biochemistry 2006, 45, 14706–14716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, A.Y.; Khaodeuanepheng, N.P.; Amarasekara, D.L.; Correia, J.J.; Lewis, K.A.; Fitzkee, N.C.; Hough, L.E.; Whitten, S.T. Intrinsically disordered regions that drive phase separation form a robustly distinct protein class. J. Biol. Chem. 2023, 299, 102801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Curto, E.; Ward, R.J.; Pediani, J.D.; Milligan, G. Ligand regulation of the quaternary organization of cell surface M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors analyzed by fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) imaging and homogeneous time-resolved FRET. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 23318–23330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.X.; Hu, K.; Liu, T.; Stern, M.K.; Mistry, R.; Challiss, R.A.J.; Costanzi, S.; Wess, J. Novel structural and functional insights into M3 muscarinic receptor dimer/oligomer formation. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288, 34777–34790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, A.Q.; Li, S.S.; Li, H.L.; Zhong, L.L.; Tian, G.B.; Zhao, X.Y.; Wang, Q.P. A rapid and reproducible method for generating germ-free Drosophila melanogaster. Biophys. Rep. 2024, 10, 364–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.; Heng, J.; Liu, F.; Zhang, S.; Liu, P. Isolation and proteomic study of fish liver lipid droplets. Biophys. Rep. 2023, 9, 120–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Ronan, E.A.; Iliff, A.J.; Al-Ebidi, R.; Kitsopoulos, P.; Grosh, K.; Liu, J.; Xu, X.Z.S. Characterization of auditory sensation in C. elegans. Biophys. Rep. 2024, 10, 351–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Fan, Z.; Liu, J. Generation and characterization of nanobodies targeting GPCR. Biophys. Rep. 2024, 10, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.G.; Ma, D.F.; Hu, S.X.; Li, M.; Lu, Y. Real-time analysis of nanoscale dynamics in membrane protein insertion via single-molecule imaging. Biophys. Rep. 2024, 10, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.M.; Guo, Q.H.; Guan, J.X.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, T.; Xie, L.P.; Fan, J. Single-molecule tracking in living microbial cells. Biophys. Rep. 2025, 11, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Tian, B.Y.; Xu, X.J.; Luan, H.Q.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, W.H.; Hu, L.Q.; Li, Y.Y.; Yao, Y.C.; Li, W.X.; et al. Neuronal synaptic architecture revealed by cryo-correlative light and electron microscopy. Biophys. Rep. 2025, 11, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweiry, J.H.; Shibuya, I.; Asada, N.; Niwa, K.; Doolabh, K.; Habara, Y.; Kanno, T.; Mann, G.E. Acute oxidative stress modulates secretion and repetitive Ca2+ spiking in rat exocrine pancreas. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1999, 1454, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oomori, Y.; Habara, Y.; Kanno, T. Muscarinic and nicotinic receptor-mediated Ca2+ dynamics in rat adrenal chromaffin cells during development. Cell Tissue Res. 1998, 294, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satoh, Y.; Sano, K.; Habara, Y.; Kanno, T. Effects of carbachol and catecholamines on ultrastructure and intracellular calcium-ion dynamics of acinar and myoepithelial cells of lacrimal glands. Cell Tissue Res. 1997, 289, 473–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okada, N.; Ohshio, G.; Manabe, T.; Imamura, M.; Habara, Y.; Kanno, T. Intracellular Ca2+ dynamics and in vitro secretory response in acute pancreatitis induced by a choline-deficient, ethionine-supplemented diet in mice. Digestion 1995, 56, 502–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).