Microplastics’ Impact on the Development of AOM/DSS-Induced Colitis-Associated Colorectal Cancer in Mice

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

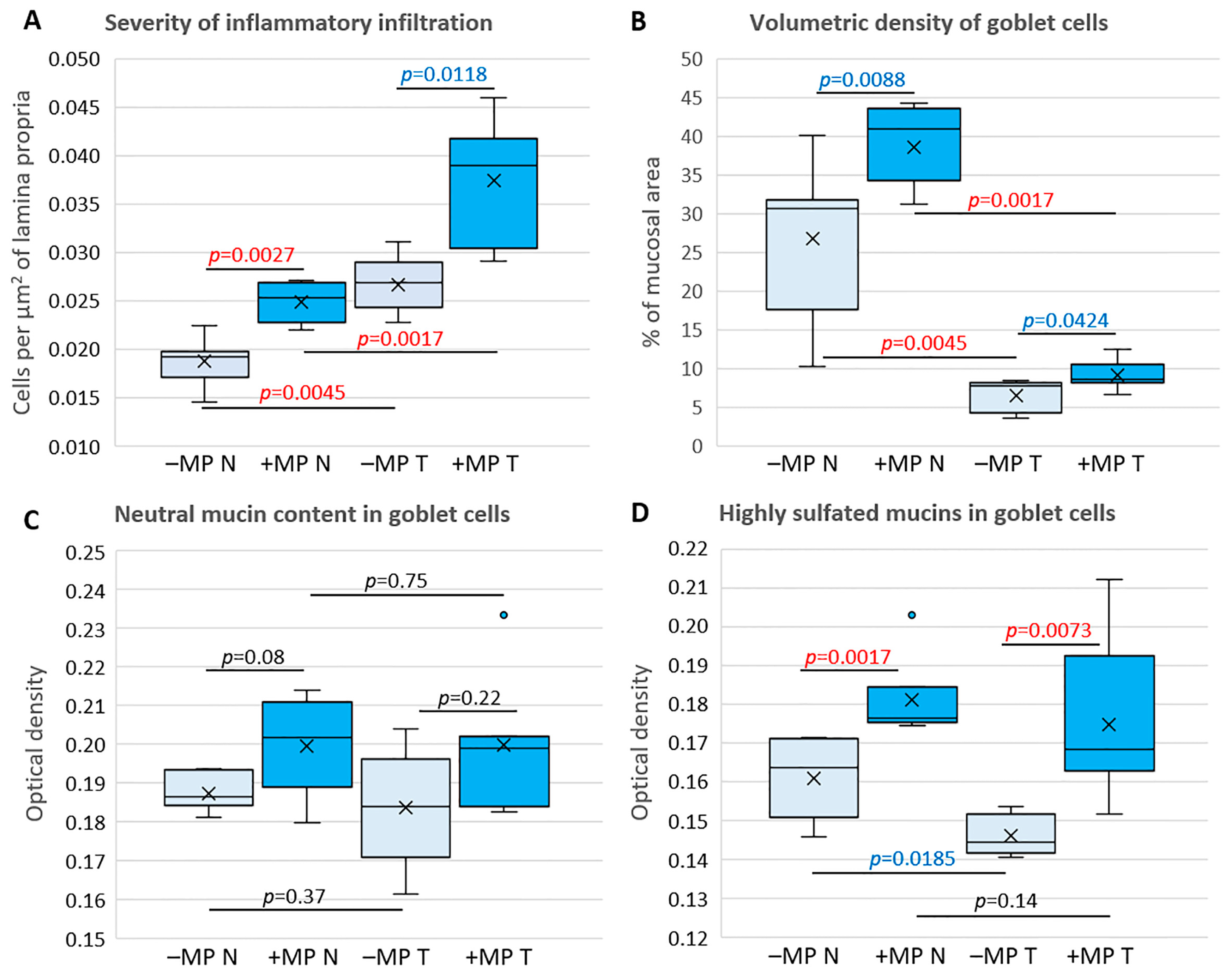

3. Discussion

Limitations of the Study and Further Research Objectives

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals

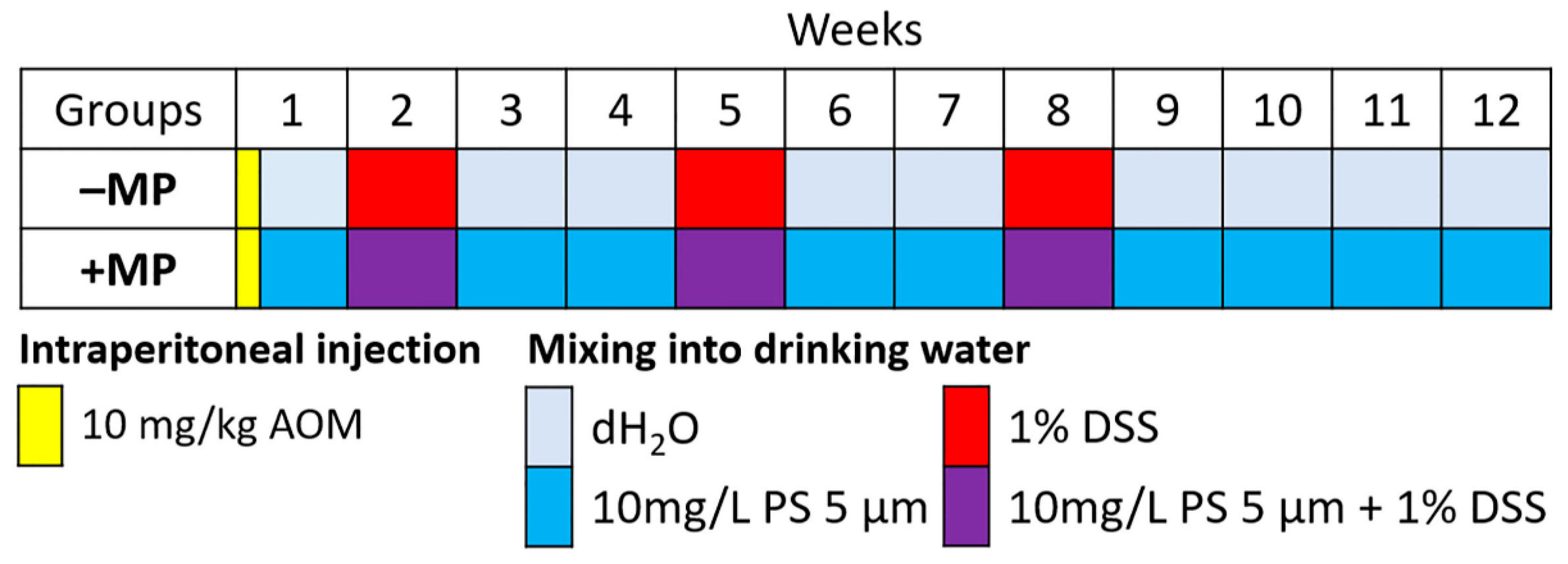

4.2. Experimental Groups

4.3. Microplastic Consumption Model

4.4. AOM/DSS-Induced Colitis-Associated Colorectal Cancer Model

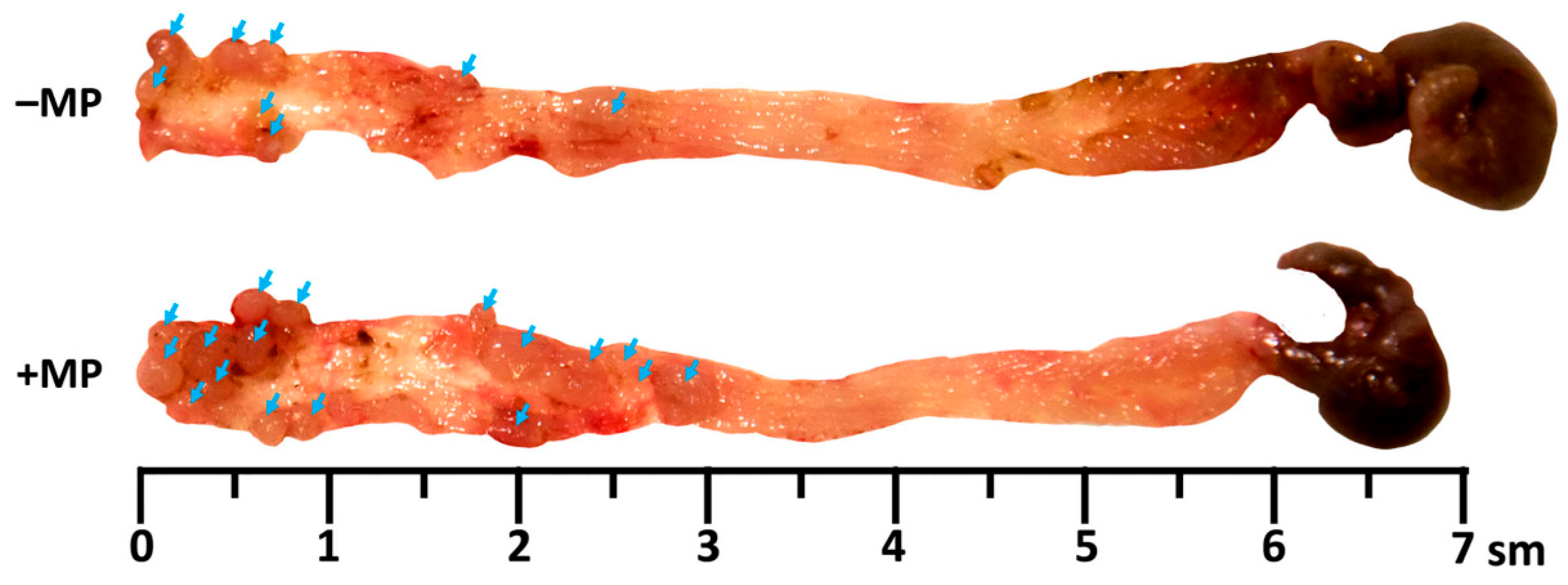

4.5. Macroscopic Evaluation of Tumor Nodes in the Colon

4.6. Histological Study of the Colon

4.6.1. Preparation of Histological Specimens

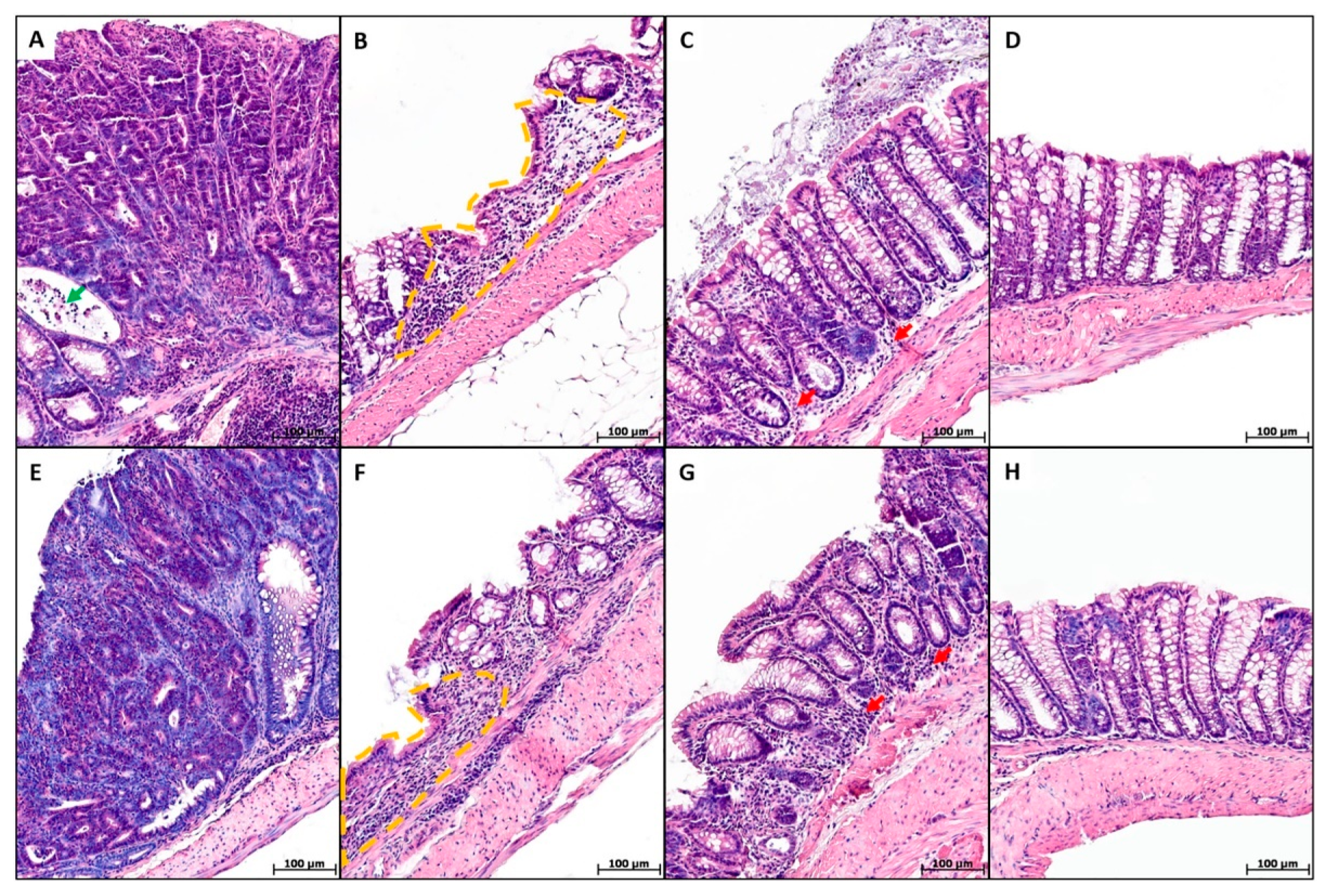

4.6.2. Prevalence of the Pathological Process

4.6.3. Severity of Inflammatory Infiltration

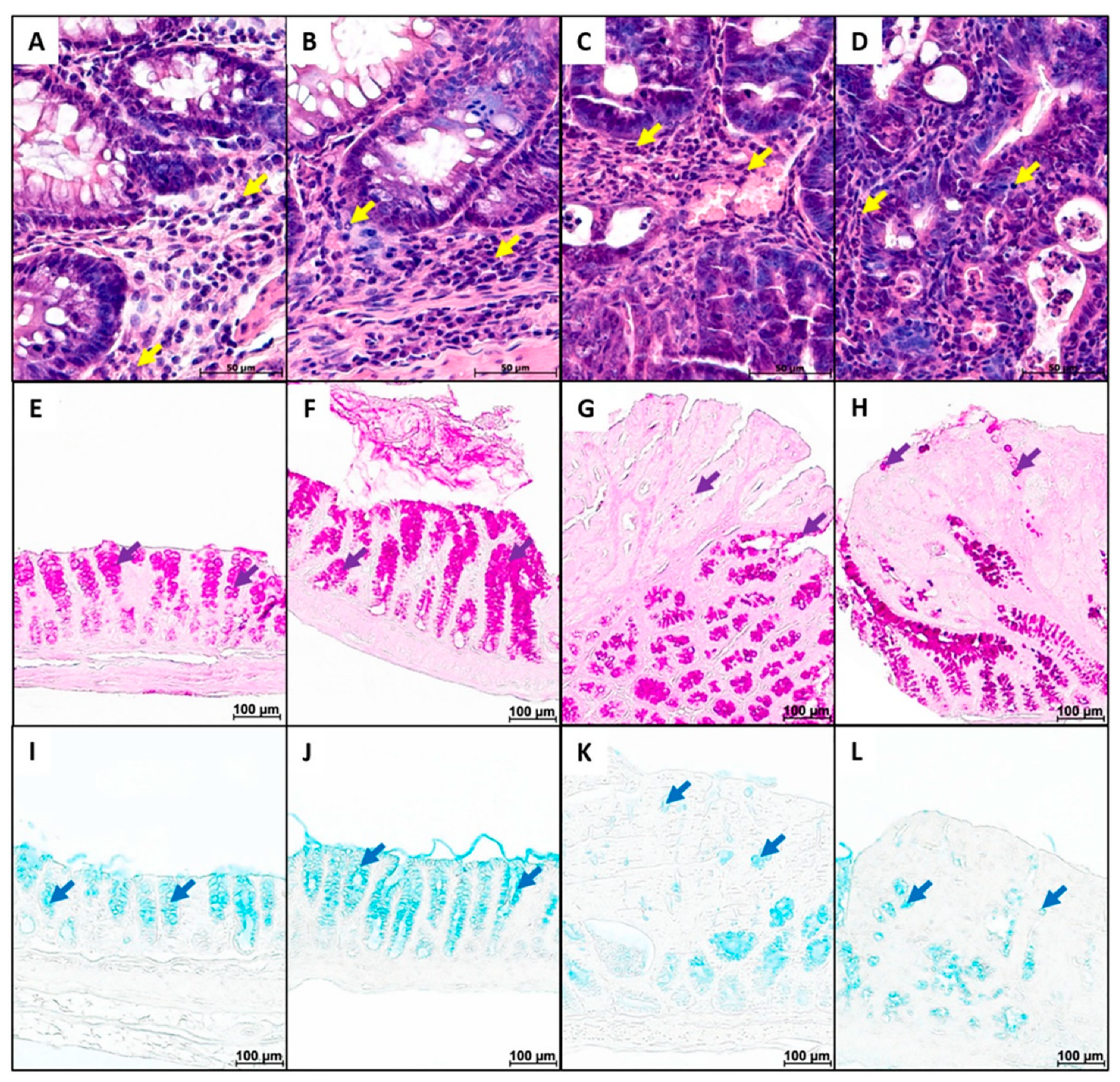

4.6.4. Goblet Cell Content and Mucus Properties

4.6.5. Enteroendocrine Cell Content

4.7. Real-Time PCR

4.8. ELISA

4.9. Statistics

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AOM | Azoxymethane |

| Bax | BCL2-associated X, apoptosis regulator |

| CAC | Colitis-associated colorectal cancer |

| Cldn2, Cldn4, Cldn7 | Claudin 2, 4, 7 |

| CRC | Colorectal cancer |

| DSS | Dextran sulfate sodium salt |

| EEC | Enteroendocrine cell |

| H&E | Hematoxylin and eosin staining |

| IBD | Inflammatory bowel disease |

| IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10 | Interleukin-1 beta, -6, -10 |

| Mki67 | Marker of proliferation Ki-67 |

| MP | Microplastic |

| Muc1, Muc3, Muc13 | Mucin 1, 3, 13 |

| NP | Nano-plastic |

| PA | Polyamide |

| PAS-reaction | Periodic Acid-Schiff-reaction |

| PC | Polycarbonate |

| PE | Polyethylene |

| PET | Polyethylene terephthalate |

| PMMA | Poly methyl methacrylate |

| PP | Polypropylene |

| PS | Polystyrene |

| PU | Polyurethane |

| PVC | Polyvinyl chloride |

| qRT-PCR | Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction |

| TNF-α | Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha |

References

- Zolotova, N.; Kosyreva, A.; Dzhalilova, D.; Makarova, O.; Fokichev, N. Harmful Effects of the Microplastic Pollution on Animal Health: A Literature Review. Peerj 2022, 10, e13503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dube, E.; Okuthe, G.E. Plastics and Micro/Nano-Plastics (MNPs) in the Environment: Occurrence, Impact, and Toxicity. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winiarska, E.; Jutel, M.; Zemelka-Wiacek, M. The Potential Impact of Nano- and Microplastics on Human Health: Understanding Human Health Risks. Environ. Res. 2024, 251, 118535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senathirajah, K.; Attwood, S.; Bhagwat, G.; Carbery, M.; Wilson, S.; Palanisami, T. Estimation of the Mass of Microplastics Ingested—A Pivotal First Step towards Human Health Risk Assessment. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 404, 124004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ke, D.; Zheng, J.; Liu, X.; Xu, X.; Zhao, L.; Gu, Y.; Yang, R.; Liu, S.; Yang, S.; Du, J.; et al. Occurrence of Microplastics and Disturbance of Gut Microbiota: A Pilot Study of Preschool Children in Xiamen, China. eBioMedicine 2023, 97, 104828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, K.D.; Covernton, G.A.; Davies, H.L.; Dower, J.F.; Juanes, F.; Dudas, S.E. Human Consumption of Microplastics. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 7068–7074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danopoulos, E.; Twiddy, M.; Rotchell, J.M. Microplastic Contamination of Drinking Water: A Systematic Review. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0236838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Raamsdonk, L.W.D.; van der Zande, M.; Koelmans, A.A.; Hoogenboom, R.L.A.P.; Peters, R.J.B.; Groot, M.J.; Peijnenburg, A.A.C.M.; Weesepoel, Y.J.A. Current Insights into Monitoring, Bioaccumulation, and Potential Health Effects of Microplastics Present in the Food Chain. Foods 2020, 9, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Chen, Z.; Chen, Y.; Yang, F.; Yao, W.; Xie, Y. Microplastics and Nanoplastics: Emerging Contaminants in Food. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 10450–10468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuri, G.; Karanasiou, A.; Lacorte, S. Microplastics: Human Exposure Assessment through Air, Water, and Food. Environ. Int. 2023, 179, 108150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kutralam-Muniasamy, G.; Shruti, V.C.; Pérez-Guevara, F.; Roy, P.D. Microplastic Diagnostics in Humans: “The 3Ps” Progress, Problems, and Prospects. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 856, 159164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roslan, N.S.; Lee, Y.Y.; Ibrahim, Y.S.; Tuan Anuar, S.; Yusof, K.M.K.K.; Lai, L.A.; Brentnall, T. Detection of Microplastics in Human Tissues and Organs: A Scoping Review. J. Glob. Health 2024, 14, 04179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.; Wang, M.; Feng, Z.; Wang, Z.; Lv, M.; Chang, J.; Chen, L.; Wang, C. Human Microplastics Exposure and Potential Health Risks to Target Organs by Different Routes: A Review. Curr. Pollut. Rep. 2023, 9, 468–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, R.-H.; Chen, H.-T.; Lee, I.-T.; Vo, T.-T.-T.; Wang, Y.-L. Microplastics and Nanoplastics in Health Concerning Cellular Toxicity Mechanisms, Exposure Pathways, and Global Mitigation Strategies. Life 2025, 15, 1449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Zhang, B.; Yao, Q.; Feng, X.; Shen, T.; Guo, P.; Wang, P.; Bai, Y.; Li, B.; Wang, P.; et al. Toxicological Effects of Micro/Nano-Plastics on Mouse/Rat Models: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1103289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goswami, S.; Adhikary, S.; Bhattacharya, S.; Agarwal, R.; Ganguly, A.; Nanda, S.; Rajak, P. The Alarming Link between Environmental Microplastics and Health Hazards with Special Emphasis on Cancer. Life Sci. 2024, 355, 122937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abbas, G.; Ahmed, U.; Ahmad, M.A. Impact of Microplastics on Human Health: Risks, Diseases, and Affected Body Systems. Microplastics 2025, 4, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, B.; Zhong, Y.; Huang, Y.; Lin, X.; Liu, J.; Lin, L.; Hu, M.; Jiang, J.; Dai, M.; Wang, B.; et al. Underestimated Health Risks: Polystyrene Micro- and Nanoplastics Jointly Induce Intestinal Barrier Dysfunction by ROS-Mediated Epithelial Cell Apoptosis. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2021, 18, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolotova, N.; Dzhalilova, D.; Tsvetkov, I.; Silina, M.; Fokichev, N.; Makarova, O. Microplastic Effects on Mouse Colon in Normal and Colitis Conditions: A Literature Review. PeerJ 2025, 13, e18880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravindra, K.; Kaur, M.; Mor, S. Impacts of Microplastics on Gut Health: Current Status and Future Directions. Indian. J. Gastroenterol. 2025. advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, F.; Ren, H.; Zhang, Y. Analysis of Microplastics in Human Feces Reveals a Correlation between Fecal Microplastics and Inflammatory Bowel Disease Status. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 414–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolotova, N.; Dzhalilova, D.; Tsvetkov, I.; Makarova, O. Influence of Microplastics on Morphological Manifestations of Experimental Acute Colitis. Toxics 2023, 11, 730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zolotova, N.; Silina, M.; Dzhalilova, D.; Tsvetkov, I.; Fokichev, N.; Makarova, O. Influence of Microplastics on Manifestations of Experimental Chronic Colitis. Toxics 2025, 13, 701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Wang, J.; Wei, X.; Chang, L.; Liu, S. Proinflammatory Properties and Lipid Disturbance of Polystyrene Microplastics in the Livers of Mice with Acute Colitis. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 750, 143085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, S.; Li, H.; Wang, J.; Wu, B.; Guo, X. Polystyrene Microplastics Aggravate Inflammatory Damage in Mice with Intestinal Immune Imbalance. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 833, 155198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, T.; Wang, D.; Zhao, Y.; Li, X.; Yang, G.; Jin, Y. Polystyrene Microplastics Exacerbate Experimental Colitis in Mice Tightly Associated with the Occurrence of Hepatic Inflammation. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 844, 156884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xie, S.; Zhang, R.; Li, Z.; Liu, C.; Chen, Y.; Yu, Q. Microplastics Perturb Colonic Epithelial Homeostasis Associated with Intestinal Overproliferation, Exacerbating the Severity of Colitis. Environ. Res. 2023, 217, 114861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Wan, Y.; Song, L.; Wang, L.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Huang, D. Polystyrene Nanobeads Exacerbate Chronic Colitis in Mice Involving in Oxidative Stress and Hepatic Lipid Metabolism. Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2023, 20, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzhalilova, D.; Zolotova, N.; Fokichev, N.; Makarova, O. Murine Models of Colorectal Cancer: The Azoxymethane (AOM)/Dextran Sulfate Sodium (DSS) Model of Colitis-Associated Cancer. PeerJ 2023, 11, e16159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seyedian, S.S.; Nokhostin, F.; Malamir, M.D. A Review of the Diagnosis, Prevention, and Treatment Methods of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J. Med. Life 2019, 12, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.C.; Itzkowitz, S.H. Colorectal Cancer in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: Mechanisms and Management. Gastroenterology 2022, 162, 715–730.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global Cancer Statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA A Cancer J. Clin. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.W.; Harpaz, N.; Itzkowitz, S.H.; Parsons, R.E. Molecular Mechanisms in Colitis-Associated Colorectal Cancer. Oncogenesis 2023, 12, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bopanna, S.; Ananthakrishnan, A.N.; Kedia, S.; Yajnik, V.; Ahuja, V. Risk of Colorectal Cancer in Asian Patients with Ulcerative Colitis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2017, 2, 269–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Jiang, C.; Morgan, E.; Zahwe, M.; Cao, Y.; Bray, F.; Jemal, A. Colorectal Cancer Incidence Trends in Younger versus Older Adults: An Analysis of Population-Based Cancer Registry Data. Lancet Oncol. 2025, 26, 51–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akimoto, N.; Ugai, T.; Zhong, R.; Hamada, T.; Fujiyoshi, K.; Giannakis, M.; Wu, K.; Cao, Y.; Ng, K.; Ogino, S. Rising Incidence of Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer—A Call to Action. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 18, 230–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mashayekhi-Sardoo, H.; Ghoreshi, Z.-A.-S.; Askarpour, H.; Arefinia, N.; Ali-Hassanzadeh, M. The Clinical Relevance of Microplastic Exposure on Colorectal Cancer: A Systematic Review. Cancer Epidemiol. 2025, 97, 102840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roslan, N.S.; Lee, Y.Y.; Anuar, S.T.; Yusof, K.M.K.K.; Brentnall, T.; Lai, L.A.; Ali, A.A.M.; Ibrahim, Y.S. Comparative Analysis of Physical and Polymer Characteristics of Microplastics Detected in Human Colorectal Cancer Samples from the United States and Malaysia. J. Gastro. Hepatol. 2025, 40, 2723–2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, D.; Liu, H.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, H.; Qiu, M.; Yang, Z.; Hao, J.; Jiang, Z.; Gao, M.; Zhang, X.; et al. Microplastics Promote Chemoresistance by Mediating Lipid Metabolism and Suppressing Pyroptosis in Colorectal Cancer. Apoptosis 2025, 30, 2287–2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, W.; Han, Y.; Zhang, M.; Zhu, K.; Yang, Z.; Qiu, M.; Guo, Y.; Dong, Z.; Hao, J.; Zhang, X.; et al. Effects of Microplastics on Chemo-Resistance and Tumorigenesis of Colorectal Cancer. Apoptosis 2025, 30, 1005–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, W.; Hao, J.; Zhang, M.; Liu, H.; Tian, F.; Zhang, X.; Jiang, Z.; Chen, C.; Gao, M.; Zhang, H. Identification and Analysis of Microplastics in Peritumoral and Tumor Tissues of Colorectal Cancer. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 16130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetin, M.; Demirkaya Miloglu, F.; Kilic Baygutalp, N.; Ceylan, O.; Yildirim, S.; Eser, G.; Gul, H.İ. Higher Number of Microplastics in Tumoral Colon Tissues from Patients with Colorectal Adenocarcinoma. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2023, 21, 639–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhang, H.; Shi, L.; Jia, Y.; Sheng, H. Detection and Quantification of Microplastics in Various Types of Human Tumor Tissues. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2024, 283, 116818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Qu, J.; Jin, H.; Mao, W. Associations between Microplastics in Human Feces and Colorectal Cancer Risk. J. Hazard. Mater. 2025, 495, 139099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuai, Y.; Chen, Z.; Xie, K.; Chen, J.; He, J.; Gao, J.; Yu, C. Long-Term Exposure to Polystyrene Microplastics Reduces Macrophages and Affects the Microbiota–Gut–Brain Axis in Mice. Toxicology 2024, 509, 153951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Li, R.; Li, J.; Zou, J. Polystyrene Nanoplastics Promote Colitis-Associated Cancer by Disrupting Lipid Metabolism and Inducing DNA Damage. Environ. Int. 2025, 195, 109258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q.; Dai, H.; Wang, B.; Xu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Ma, Q.; Xu, F.; Cheng, H.; Sun, D.; et al. Nanoplastics Shape Adaptive Anticancer Immunity in the Colon in Mice. Nano Lett. 2023, 23, 3516–3523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, K.H.D. Toxic Effects of Nanoplastics on Animals: Comparative Insights into Microplastic Toxicity. Environments 2025, 12, 429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.K.; Ma, X.; Lichtfouse, E.; Robert, D. Nanoplastics Are Potentially More Dangerous than Microplastics. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2023, 21, 1933–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wibowo, A.A.; Sitompul, A.; Yasmina, A.; Oktaviyanti, I.K.; Lahdimawan, A.; Damayanthi, E.D. An Increase in Inflammatory Cells Related to the Increase Incidence of Colitis and Colorectal Cancer. Bali Med. J. 2022, 11, 499–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, M.; Yin, W.; Zhang, J.; Yin, J.; Tang, X.; Ling, J.; Tang, Z.; Yin, W.; Wang, X.; Ni, Q.; et al. Role of Gut Microbiota and Bacterial Metabolites in Mucins of Colorectal Cancer. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2023, 13, 1119992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Y.S.; Ho, S.B. Intestinal Goblet Cells and Mucins in Health and Disease: Recent Insights and Progress. Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 2010, 12, 319–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontaine, N.; Meslin, J.C.; Doré, J. Selective in Vitro Degradation of the Sialylated Fraction of Germ-Free Rat Mucins by the Caecal Flora of the Rat. Reprod. Nutr. Dev. 1998, 38, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, A.M.; Wright, D.P. Bacterial Glycosulphatases and Sulphomucin Degradation. Can. J. Gastroenterol. 1997, 11, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atanga, R.; Singh, V.; In, J.G. Intestinal Enteroendocrine Cells: Present and Future Druggable Targets. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 8836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.A.; O’Flaherty, E.A.A.; Guccio, N.; Punnoose, A.; Darwish, T.; Lewis, J.E.; Foreman, R.E.; Li, J.; Kay, R.G.; Adriaenssens, A.E.; et al. Single-Cell Transcriptomic Atlas of Enteroendocrine Cells along the Murine Gastrointestinal Tract. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0308942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mawe, G.M.; Hoffman, J.M. Serotonin Signaling in the Gastrointestinal Tract. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013, 10, 473–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunawardene, A.R.; Corfe, B.M.; Staton, C.A. Classification and Functions of Enteroendocrine Cells of the Lower Gastrointestinal Tract. Int. J. Exp. Pathol. 2011, 92, 219–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Liang, Y.; Cao, L.; Dong, X.; Sun, D. Neuroendocrine Differentiation: A Risk Fellow in Colorectal Cancer. World J. Surg. Onc 2023, 21, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almasmoum, H. The Roles of Transmembrane Mucins Located on Chromosome 7q22.1 in Colorectal Cancer. CMAR 2021, 13, 3271–3280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelaseyed, T.; Bergström, J.H.; Gustafsson, J.K.; Ermund, A.; Birchenough, G.M.H.; Schütte, A.; van der Post, S.; Svensson, F.; Rodríguez-Piñeiro, A.M.; Nyström, E.E.L.; et al. The Mucus and Mucins of the Goblet Cells and Enterocytes Provide the First Defense Line of the Gastrointestinal Tract and Interact with the Immune System. Immunol. Rev. 2014, 260, 8–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senapati, S.; Ho, S.B.; Sharma, P.; Das, S.; Chakraborty, S.; Kaur, S.; Niehans, G.; Batra, S.K. Expression of Intestinal MUC17 Membrane-Bound Mucin in Inflammatory and Neoplastic Diseases of the Colon. J. Clin. Pathol. 2010, 63, 702–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, M.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, X.; Ma, P.; Li, Y.; Wu, Y.; Chen, X.; Deng, X.; Yang, T.; Mao, X.; et al. Claudin-2 Promotes Colorectal Cancer Growth and Metastasis by Suppressing NDRG1 Transcription. Clin. Transl. Med. 2021, 11, e667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ueda, J.; Semba, S.; Chiba, H.; Sawada, N.; Seo, Y.; Kasuga, M.; Yokozaki, H. Heterogeneous Expression of Claudin-4 in Human Colorectal Cancer: Decreased Claudin-4 Expression at the Invasive Front Correlates Cancer Invasion and Metastasis. Pathobiology 2007, 74, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Wang, X.; Li, W.; Wang, K.; Ding, L. Expression and Clinical Significance of Claudin-7 in Patients with Colorectal Cancer. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 2018, 17, 1533033818817774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mrouj, K.; Andrés-Sánchez, N.; Dubra, G.; Singh, P.; Sobecki, M.; Chahar, D.; Al Ghoul, E.; Aznar, A.B.; Prieto, S.; Pirot, N.; et al. Ki-67 Regulates Global Gene Expression and Promotes Sequential Stages of Carcinogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2021, 118, e2026507118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, R.S. Apoptosis in Cancer: From Pathogenesis to Treatment. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011, 30, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzhalilova, D.; Silina, M.; Tsvetkov, I.; Kosyreva, A.; Zolotova, N.; Gantsova, E.; Kirillov, V.; Fokichev, N.; Makarova, O. Changes in the Expression of Genes Regulating the Response to Hypoxia, Inflammation, Cell Cycle, Apoptosis, and Epithelial Barrier Functioning during Colitis-Associated Colorectal Cancer Depend on Individual Hypoxia Tolerance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuomisto, A.E.; Mäkinen, M.J.; Väyrynen, J.P. Systemic Inflammation in Colorectal Cancer: Underlying Factors, Effects, and Prognostic Significance. WJG 2019, 25, 4383–4404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira Miranda, D.; Soares De Lima, T.A.; Ribeiro Azevedo, L.; Feres, O.; Ribeiro Da Rocha, J.J.; Pereira-da-Silva, G. Proinflammatory Cytokines Correlate with Depression and Anxiety in Colorectal Cancer Patients. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 739650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Merlin, D. Unveiling Colitis: A Journey through the Dextran Sodium Sulfate-Induced Model. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 2024, 30, 844–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Liu, D.; Zhan, J.; Liu, X.; Li, P.; Ma, X.; Hou, H.; Wang, P. Polystyrene Microplastics Induce Kidney Injury via Gut Barrier Dysfunction and C5a/C5aR Pathway Activation. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 342, 122909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Zhuang, J.; Chen, Q.; Xu, L.; Yue, X.; Qiao, D. Polyvinyl Chloride Microplastics Induced Gut Barrier Dysfunction, Microbiota Dysbiosis and Metabolism Disorder in Adult Mice. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 241, 113809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, S.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, S.; Chen, Y.; Yuan, H.; Xu, H. Polystyrene Microplastics Exacerbated Liver Injury from Cyclophosphamide in Mice: Insight into Gut Microbiota. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 840, 156668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaoyong, W.; Jin, H.; Jiang, X.; Xu, B.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Jin, M. Benzo [a] Pyrene-Loaded Aged Polystyrene Microplastics Promote Colonic Barrier Injury via Oxidative Stress-Mediated Notch Signalling. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 457, 131820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Ye, Y.; Han, Y.; Wang, Q.; Lu, H.; Li, J.; Qian, W.; Zeng, X.; Zhang, Z.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Microplastics Dampen the Self-Renewal of Hematopoietic Stem Cells by Disrupting the Gut Microbiota-Hypoxanthine-Wnt Axis. Cell Discov. 2024, 10, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Yang, B.; Zhu, X.; Li, Q.; Song, E.; Song, Y. Oral Exposure of Polystyrene Microplastics and Doxycycline Affects Mice Neurological Function via Gut Microbiota Disruption: The Orchestrating Role of Fecal Microbiota Transplantation. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 467, 133714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Chen, T.; Liu, J.; Hou, Y.; Tan, Q.; Zhang, X.; Li, Z.; Farooq, T.H.; Yan, W.; Li, Y. Intestinal Flora Variation Reflects the Short-Term Damage of Microplastic to the Intestinal Tract in Mice. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 246, 114194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Ma, Y.; Han, X.; Chen, Y. Systematic Toxicity Evaluation of Polystyrene Nanoplastics on Mice and Molecular Mechanism Investigation about Their Internalization into Caco-2 Cells. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 417, 126092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, J.; Sun, X.; Wang, Y.; Su, J.; Li, G.; Wang, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Li, B.; Zhang, G.; et al. Biological Interactions of Polystyrene Nanoplastics: Their Cytotoxic and Immunotoxic Effects on the Hepatic and Enteric Systems. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2023, 264, 115447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jia, R.; Han, J.; Liu, X.; Li, K.; Lai, W.; Bian, L.; Yan, J.; Xi, Z. Exposure to Polypropylene Microplastics via Oral Ingestion Induces Colonic Apoptosis and Intestinal Barrier Damage through Oxidative Stress and Inflammation in Mice. Toxics 2023, 11, 127, Correction in Toxics 2023, 11, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, G.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Su, J.; Lu, Z.; Zhang, F.; Ding, W. Polystyrene Microplastic-Induced Oxidative Stress Triggers Intestinal Barrier Dysfunction via the NF-κB/NLRP3/IL-1β/MCLK Pathway. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 345, 123473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Djouina, M.; Vignal, C.; Dehaut, A.; Caboche, S.; Hirt, N.; Waxin, C.; Himber, C.; Beury, D.; Hot, D.; Dubuquoy, L.; et al. Oral Exposure to Polyethylene Microplastics Alters Gut Morphology, Immune Response, and Microbiota Composition in Mice. Environ. Res. 2022, 212, 113230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zolotova, N.A.; Dzhalilova, D.S.; Khochanskiy, D.N.; Tsvetkov, I.S.; Kosyreva, A.M.; Ponomarenko, E.A.; Diatroptova, M.A.; Mikhailova, L.P.; Mkhitarov, V.A.; Makarova, O.V. Morphofunctional Changes in Colon after Cold Stress in Male C57BL/6 Mice Susceptible and Tolerant to Hypoxia. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2021, 171, 499–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Lemos, B.; Ren, H. Tissue Accumulation of Microplastics in Mice and Biomarker Responses Suggest Widespread Health Risks of Exposure. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 46687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Huang, S.; Zhao, L.; Liu, J.; Ma, Q.; Wang, Y.; Dong, Y.; Li, C.; Qiu, P. Chang Qing Formula Ameliorates Colitis-Associated Colorectal Cancer via Suppressing IL-17/NF-κB/STAT3 Pathway in Mice as Revealed by Network Pharmacology Study. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 893231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Lai, L.A.; Brentnall, T.A.; Pan, S. Biomarkers for Colitis-Associated Colorectal Cancer. WJG 2016, 22, 7882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, F.; Sarker, D.B.; Jocelyn, J.A.; Sang, Q.-X.A. Molecular and Cellular Effects of Microplastics and Nanoplastics: Focus on Inflammation and Senescence. Cells 2024, 13, 1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Yang, J.; Chen, L.; He, J.; Qu, D.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, J.; Li, J.; et al. Gut Microbiota Participates in Polystyrene Microplastics-Induced Hepatic Injuries by Modulating the Gut–Liver Axis. ACS Nano 2023, 17, 15125–15145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Z.; Yang, Y.; Chen, S.; Wu, Z. Long-Term Exposure to Polystyrene Microspheres and High-Fat Diet–Induced Obesity in Mice: Evaluating a Role for Microbiota Dysbiosis. Environ. Health Perspect. 2024, 132, 097002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, S.; Yan, C.; Cai, G.; Xu, Q.; Zou, H.; Gu, J.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, Z.; Bian, J. Gut Dysbiosis Exacerbates Inflammatory Liver Injury Induced by Environmentally Relevant Concentrations of Nanoplastics via the Gut-Liver Axis. J. Environ. Sci. 2025, 155, 250–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.; Li, X.; Gao, H.; Hu, W.; Yu, S.; Li, X.; Lei, L.; Yang, F. The Role of Gut Microbiota in Mediating Increased Toxicity of Nano-Sized Polystyrene Compared to Micro-Sized Polystyrene in Mice. Chemosphere 2024, 358, 142275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, J.B.; Lagas, J.S.; Broestl, L.; Sponagel, J.; Rockwell, N.; Rhee, G.; Rosen, S.F.; Chen, S.; Klein, R.S.; Imoukhuede, P.; et al. Sex Differences in Cancer Mechanisms. Biol. Sex Differ. 2020, 11, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharya, S.; Sadhukhan, D.; Saraswathy, R. Role of Sex in Immune Response and Epigenetic Mechanisms. Epigenet. Chromatin 2024, 17, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsokkou, S.; Konstantinidis, I.; Papakonstantinou, M.; Chatzikomnitsa, P.; Liampou, E.; Toutziari, E.; Giakoustidis, D.; Bangeas, P.; Papadopoulos, V.; Giakoustidis, A. Sex Differences in Colorectal Cancer: Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Clinical Outcomes. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 5539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.M.; Kim, N.; Son, H.J.; Park, J.H.; Nam, R.H.; Ham, M.H.; Choi, D.; Sohn, S.H.; Shin, E.; Hwang, Y.-J.; et al. The Effect of Sex on the Azoxymethane/Dextran Sulfate Sodium-Treated Mice Model of Colon Cancer. J. Cancer Prev. 2016, 21, 271–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Notbohm, H.L.; Moser, F.; Goh, J.; Feuerbacher, J.F.; Bloch, W.; Schumann, M. The Effects of Menstrual Cycle Phases on Immune Function and Inflammation at Rest and after Acute Exercise: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Acta Physiol. 2023, 238, e14013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oertelt-Prigione, S. Immunology and the Menstrual Cycle. Autoimmun. Rev. 2012, 11, A486–A492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuentes, N.; Cabello, N.; Nicoleau, M.; Chroneos, Z.C.; Silveyra, P. Modulation of the Lung Inflammatory Response to Ozone by the Estrous Cycle. Physiol. Rep. 2019, 7, e14026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group | Tumor Nodes Number | Total Area of Tumor Nodes, mm2 | Tumor Node Diameter, mm |

|---|---|---|---|

| –MP | 6 (4; 8) | 21.6 (8.7; 26.1) | 1.8 (1.3; 2.1) |

| +MP | 12 (11; 16) | 38.2 (29.0; 43.6) | 1.6 (1.3; 2.0) |

| p-level | 0.002 | 0.018 | 0.9 |

| Group | Tumor | Ulcer | Inflammation | All |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| –MP | 2.9 (1.2; 8.7) | 5.9 (4.6; 7.2) | 57.2 (53.5; 60.1) | 73.4 (62.6; 79.2) |

| +MP | 33.3 (19.2; 45.2) | 4 (3.3; 4.5) | 58.2 (46.2; 60.2) | 98.9 (93.1; 96.4) |

| p-level | 0.009 | 0.18 | 0.8 | 0.003 |

| Genes | –MP | +MP | p-Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Muc1 | 0 (0; 0.2) | 0 (0; 0) | 0.45 |

| Muc3 | 88 (17; 147) | 218 (66; 560) | 0.33 |

| Muc13 | 8.6 (0.7; 31.5) | 2 (1.7; 6.2) | 0.70 |

| Cldn2 | 0.01 (0; 0.22) | 0 (0.13) | 0.94 |

| Cldn4 | 5.5 (1.2; 15.9) | 23.2 (3.7; 56.3) | 0.23 |

| Cldn7 | 7 (0.4; 14.3) | 8.3 (3.3; 11.3) | 0.76 |

| Bax | 9.5 (0; 40.3) | 15.9 (4.2; 21.5) | 0.85 |

| Mki67 | 0.2 (0; 18.2) | 4.3 (1.3; 35.5) | 0.42 |

| Cytokines | –MP | +MP | p-Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| IL-6 | 65.3 (62.2; 93.8) | 73.9 (69.0; 74.7) | 0.72 |

| IL-10 | 21.9 (19.4; 32.1) | 20.6 (19.8; 24.4) | 0.81 |

| TNF-α | 27.0 (26.8; 30.0) | 31.2 (26.4; 33.1) | 0.41 |

| IL-1β | 36.1 (32.9; 39.0) | 36.4 (29.7; 55.2) | 0.81 |

| Genes | Primer Sequences | |

|---|---|---|

| Actb | For: | CCTGCCACCCAGCACAAT |

| Rev: | GGGCCGGACTCGTCATAC | |

| Cldn2 | For: | TGCGACACACAGCACAGGCATCAC |

| Rev: | TCAGGAACCAGCGGCGAGTAG | |

| Cldn4 | For: | TCGTGGGTGCTCTGGGGATGCT |

| Rev: | GCGGATGACGTTGTGAGCGGTC | |

| Cldn7 | For: | GCCTTGGTAGCATGTTCCTGGA |

| Rev: | GGTACGCAGCTTTGCTTTCACTG | |

| Muc1 | For: | GGTGACCACTTCTGCCAACT |

| Rev: | TCCTTCTGAGAGCCACCACT | |

| Muc3 | For: | TGTTCAGCTTTACTGTGTTTCAA |

| Rev: | TTGCATGTCTCCTCAGGATT | |

| Muc13 | For: | AGCATGTCCCAGCTTTCTCA |

| Rev: | CCATTTGCTGCCTGAGGA | |

| Bax | For: | CATGGACTGGAGAAGGGACT |

| Rev: | ACCCCATTCTTCCTGATGC | |

| Mki67 | For: | AGGCGAAGTGGAGCTTCTGA |

| Rev: | GCTGCTGCTTCTCCTTCACTG |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zolotova, N.; Kirillova, M.; Dzhalilova, D.; Tsvetkov, I.; Fokichev, N.; Makarova, O. Microplastics’ Impact on the Development of AOM/DSS-Induced Colitis-Associated Colorectal Cancer in Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11511. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311511

Zolotova N, Kirillova M, Dzhalilova D, Tsvetkov I, Fokichev N, Makarova O. Microplastics’ Impact on the Development of AOM/DSS-Induced Colitis-Associated Colorectal Cancer in Mice. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11511. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311511

Chicago/Turabian StyleZolotova, Natalia, Maria Kirillova, Dzhuliia Dzhalilova, Ivan Tsvetkov, Nikolai Fokichev, and Olga Makarova. 2025. "Microplastics’ Impact on the Development of AOM/DSS-Induced Colitis-Associated Colorectal Cancer in Mice" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11511. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311511

APA StyleZolotova, N., Kirillova, M., Dzhalilova, D., Tsvetkov, I., Fokichev, N., & Makarova, O. (2025). Microplastics’ Impact on the Development of AOM/DSS-Induced Colitis-Associated Colorectal Cancer in Mice. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11511. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311511