Comprehensive Genomic Profiling of Small-Cell Lung Cancer Reveals Frequent Potentially Targetable Alterations

Abstract

1. Introduction

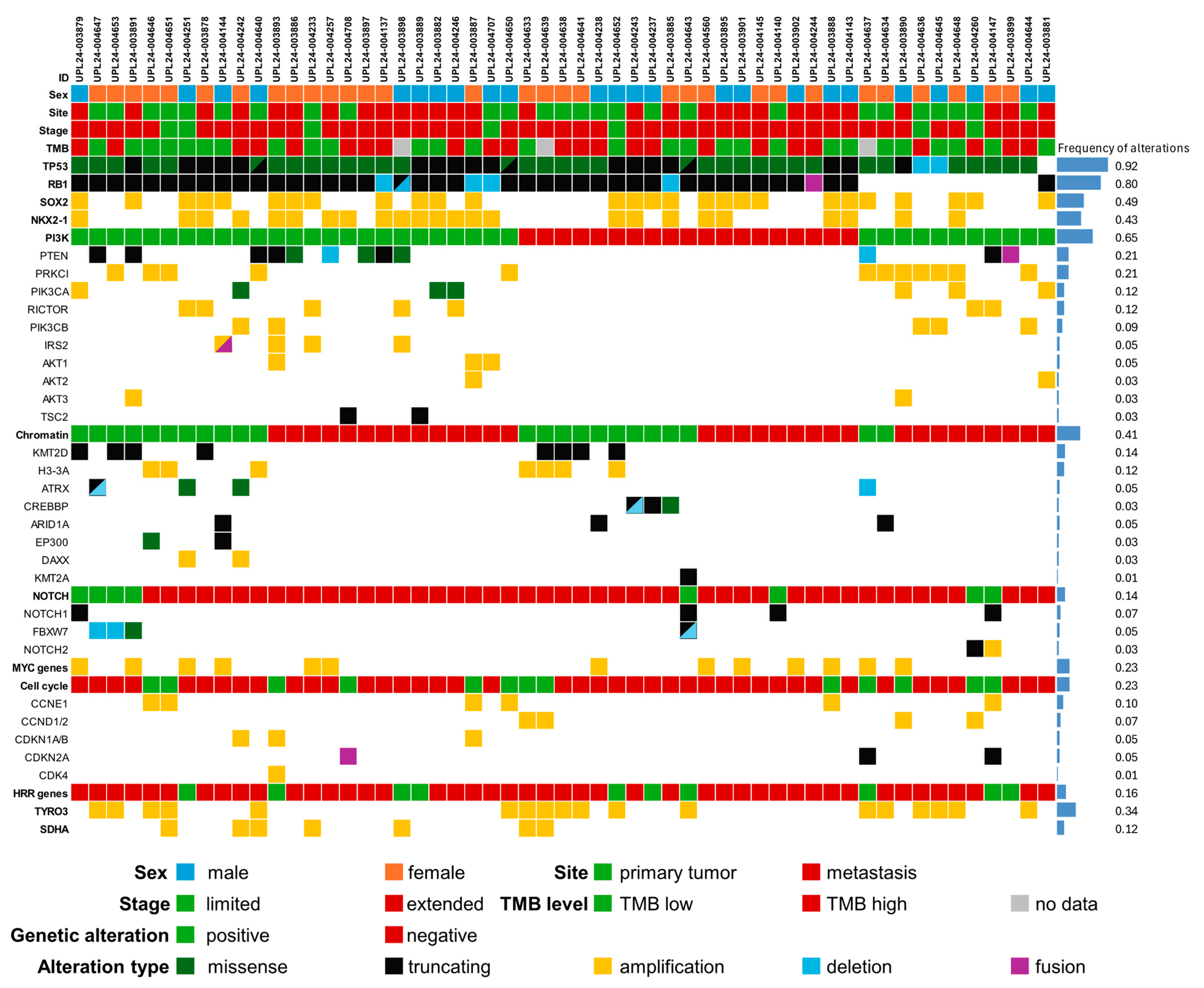

2. Results

2.1. Recurrent Small Genetic Variants

2.2. Recurrent Copy Number Changes

2.3. Genetic Alterations Recurrent in NSCLC

2.4. Correlation with Clinical Parameters

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Patients and Samples

4.2. Comprehensive Genomic Profiling

4.3. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rudin, C.M.; Durinck, S.; Stawiski, E.W.; Poirier, J.T.; Modrusan, Z.; Shames, D.S.; A Bergbower, E.; Guan, Y.; Shin, J.; Guillory, J.; et al. Comprehensive genomic analysis identifies SOX2 as a frequently amplified gene in small-cell lung cancer. Nat. Genet. 2012, 44, 1111–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- George, J.; Lim, J.S.; Jang, S.J.; Cun, Y.; Ozretić, L.; Kong, G.; Leenders, F.; Lu, X.; Fernández-Cuesta, L.; Bosco, G.; et al. Comprehensive genomic profiles of small cell lung cancer. Nature 2015, 524, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Solta, A.; Ernhofer, B.; Boettiger, K.; Megyesfalvi, Z.; Heeke, S.; Hoda, M.A.; Lang, C.; Aigner, C.; Hirsch, F.R.; Schelch, K.; et al. Small cells—Big issues: Biological implications and preclinical advancements in small cell lung cancer. Mol. Cancer 2024, 23, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Megyesfalvi, Z.; Gay, C.M.; Popper, H.; Pirker, R.; Ostoros, G.; Heeke, S.; Lang, C.; Hoetzenecker, K.; Schwendenwein, A.; Boettiger, K.; et al. Clinical insights into small cell lung cancer: Tumor heterogeneity, diagnosis, therapy, and future directions. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2023, 73, 620–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sivakumar, S.; Moore, J.A.; Montesion, M.; Sharaf, R.; Lin, D.I.; Colón, C.I.; Fleischmann, Z.; Ebot, E.M.; Newberg, J.Y.; Mills, J.M.; et al. Integrative Analysis of a Large Real-World Cohort of Small Cell Lung Cancer Identifies Distinct Genetic Subtypes and Insights into Histologic Transformation. Cancer Discov. 2023, 13, 1572–1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhou, H.; Hu, Y.; Luo, R.; Zhao, Y.; Pan, H.; Ji, L.; Zhou, T.; Zhang, L.; Long, H.; Fu, J.; et al. Multi-region exome sequencing reveals the intratumoral heterogeneity of surgically resected small cell lung cancer. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 5431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ross, J.S.; Wang, K.; Elkadi, O.R.; Tarasen, A.; Foulke, L.; E Sheehan, C.; A Otto, G.; Palmer, G.; Yelensky, R.; Lipson, D.; et al. Next-generation sequencing reveals frequent consistent genomic alterations in small cell undifferentiated lung cancer. J. Clin. Pathol. 2014, 67, 772–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, L.; Luo, J.; Ge, T.; Fan, P.; Sun, L.; Hou, L.; Li, J.; Yu, H.; Wu, C.; et al. Comprehensive genomic profiling of combined small cell lung cancer. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2021, 10, 636–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wagner, A.H.; Devarakonda, S.; Skidmore, Z.L.; Krysiak, K.; Ramu, A.; Trani, L.; Kunisaki, J.; Masood, A.; Waqar, S.N.; Spies, N.C.; et al. Recurrent WNT pathway alterations are frequent in relapsed small cell lung cancer. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Oh, M.S.; Garon, E.B.; Lisberg, A.E.; Cummings, A.L.; Barrett, A.; Ashok, A.; Mauer, E.; Yilma, B.; Goldman, J.W. Brief Report: The Genomic Landscape of Small Cell Lung Cancer in Never-Smoking Patients. Clin. Lung Cancer 2025, 26, 434–439.e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roper, N.; Velez, M.J.; Chiappori, A.; Kim, Y.S.; Wei, J.S.; Sindiri, S.; Takahashi, N.; Mulford, D.; Kumar, S.; Ylaya, K.; et al. Notch signaling and efficacy of PD-1/PD-L1 blockade in relapsed small cell lung cancer. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Horvath, L.; Lang, C.; Boettiger, K.; Aigner, C.; Dome, B.; Megyesfalvi, Z. Potential subtype-specific therapeutic approaches in small cell lung cancer. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 2024, 36, 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cardano, M.; Buscemi, G.; Zannini, L. Sex Disparities in P53 Regulation and Functions: Novel Insights for Personalized Cancer Therapies. Cells 2025, 14, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rockwell, N.C.; Yang, W.; Warrington, N.M.; Staller, M.V.; Griffith, M.; Griffith, O.L.; Gurnett, C.A.; Cohen, B.A.; Baldridge, D.; Rubin, J.B. Sex- and mutation-specific p53 gain-of-function activity in gliomagenesis. Cancer Res. Commun. 2021, 1, 148–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang, H.; Ou, Q.; Li, D.; Qin, T.; Bao, H.; Hou, X.; Wang, K.; Wang, F.; Deng, Q.; Liang, J.; et al. Genes associated with increased brain metastasis risk in non-small cell lung cancer: Comprehensive genomic profiling of 61 resected brain metastases versus primary non-small cell lung cancer (Guangdong Association Study of Thoracic Oncology 1036). Cancer 2019, 125, 3535–3544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, Y.; Jin, Y.; Li, Q.; Yuan, X. Advances in Lung Cancer Driver Genes Associated with Brain Metastasis. Front. Oncol. 2021, 10, 606300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hashemi, M.; Etemad, S.; Rezaei, S.; Ziaolhagh, S.; Rajabi, R.; Rahmanian, P.; Abdi, S.; Koohpar, Z.K.; Rafiei, R.; Raei, B.; et al. Progress in targeting PTEN/PI3K/Akt axis in glioblastoma therapy: Revisiting molecular interactions. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 158, 114204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakre, N.; Wildey, G.; Behtaj, M.; Kresak, A.; Yang, M.; Fu, P.; Dowlati, A. RICTOR amplification identifies a subgroup in small cell lung cancer and predicts response to drugs targeting mTOR. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 5992–6002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Krencz, I.; Sztankovics, D.; Danko, T.; Sebestyen, A.; Khoor, A. Progression and metastasis of small cell lung carcinoma: The role of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway and metabolic alterations. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2021, 40, 1141–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Liu, Y.; Justilien, V.; Fields, A.P.; Murray, N.R. Recurrent copy number gains drive PKCι expression and PKCι-dependent oncogenic signaling in human cancers. Adv. Biol. Regul. 2020, 78, 100754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Johnson, S.S.; Liu, D.; Ewald, J.T.; Robles-Planells, C.; Christensen, K.A.; Bayanbold, K.; Wels, B.R.; Solst, S.R.; O’Dorisio, M.S.; Allen, B.G.; et al. Auranofin Inhibition of Thioredoxin Reductase Sensitizes Lung Neuroendocrine Tumor Cells (NETs) and Small Cell Lung Cancer (SCLC) Cells to Sorafenib as well as Inhibiting SCLC Xenograft Growth. bioRxiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, S.S.; Liu, D.; Ewald, J.T.; Robles-Planells, C.; Pulliam, C.; Christensen, K.A.; Bayanbold, K.; Wels, B.R.; Solst, S.R.; O’Dorisio, M.S.; et al. Auranofin inhibition of thioredoxin reductase sensitizes lung neuroendocrine tumor cells (NETs) and small cell lung cancer (SCLC) cells to sorafenib as well as inhibiting SCLC xenograft growth. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2024, 25, 2382524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Alves, R.d.C.S.; Meurer, R.T.; Roehe, A.V. MYC amplification is associated with poor survival in small cell lung cancer: A chromogenic in situ hybridization study. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 140, 2021–2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mollaoglu, G.; Guthrie, M.R.; Böhm, S.; Brägelmann, J.; Can, I.; Ballieu, P.M.; Marx, A.; George, J.; Heinen, C.; Chalishazar, M.D.; et al. MYC Drives Progression of Small Cell Lung Cancer to a Variant Neuroendocrine Subtype with Vulnerability to Aurora Kinase Inhibition. Cancer Cell 2017, 31, 270–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Peifer, M.; Fernández-Cuesta, L.; Sos, M.L.; George, J.; Seidel, D.; Kasper, L.H.; Plenker, D.; Leenders, F.; Sun, R.; Zander, T.; et al. Integrative genome analyses identify key somatic driver mutations of small-cell lung cancer. Nat. Genet. 2012, 44, 1104–1110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kirk, N.A.; Kim, K.-B.; Park, K.-S. Effect of chromatin modifiers on the plasticity and immunogenicity of small-cell lung cancer. Exp. Mol. Med. 2022, 54, 2118–2127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Park, S.-M.; Choi, E.-Y.; Bae, M.; Kim, S.; Park, J.B.; Yoo, H.; Choi, J.K.; Kim, Y.-J.; Lee, S.-H.; Kim, I.-H. Histone variant H3F3A promotes lung cancer cell migration through intronic regulation. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Su, D.; Zhang, D.; Jin, J.; Ying, L.; Han, M.; Chen, K.; Li, B.; Wu, J.; Xie, Z.; Zhang, F.; et al. Identification of predictors of drug sensitivity using patient-derived models of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wang, L.; Cybula, M.; Rostworowska, M.; Wang, L.; Mucha, P.; Bulicz, M.; Bieniasz, M. Upregulation of Succinate Dehydrogenase (SDHA) Contributes to Enhanced Bioenergetics of Ovarian Cancer Cells and Higher Sensitivity to Anti-Metabolic Agent Shikonin. Cancers 2022, 14, 5097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Yong, L.; Fang, Y.; Jin, L.; Zhang, X.; Luis, M.A.; Lin, X.; Tang, S.; Cai, F. Unveiling the hidden role of SDHA in breast cancer proliferation: A novel therapeutic avenue. Cancer Cell Int. 2025, 25, 108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Qian, X.; Zhu, L.; Xu, M.; Liu, H.; Yu, X.; Shao, Q.; Qin, J. Shikonin suppresses small cell lung cancer growth via inducing ATF3-mediated ferroptosis to promote ROS accumulation. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2023, 382, 110588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Park, M.; Kuen, D.-S.; Park, J.; Choi, M.; Kim, Y.; Roh, E.C.; Choi, Y.J.; Kim, Y.G.; Chung, Y.; Cho, S.Y.; et al. TYRO3 blockade enhances anti-PD-1 therapy response by modulating expression of CCN1 in tumor microenvironment. J. Immunother. Cancer 2023, 11, e006084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ban, J.; Qian, J.; Zhang, C.; Li, J. Recent advances in TAM mechanisms in lung diseases. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jiang, Z.; Lim, S.-O.; Yan, M.; Hsu, J.L.; Yao, J.; Wei, Y.; Chang, S.-S.; Yamaguchi, H.; Lee, H.-H.; Ke, B.; et al. TYRO3 induces anti–PD-1/PD-L1 therapy resistance by limiting innate immunity and tumoral ferroptosis. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 131, e139434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Hamilton, G.; Rath, B.; Klameth, L.; Hochmair, M. Receptor tyrosine kinase expression of circulating tumor cells in small cell lung cancer. Oncoscience 2015, 2, 629–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Borghaei, H.; de Marinis, F.; Dumoulin, D.; Reynolds, C.; Theelen, W.S.M.E.; Percent, I.; Gutierrez Calderon, V.; Johnson, M.L.; Madroszyk-Flandin, A.; Garon, E.B.; et al. SAPPHIRE: Phase III study of sitravatinib plus nivolumab versus docetaxel in advanced nonsquamous non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann. Oncol. 2024, 35, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smart, S.K.; Vasileiadi, E.; Wang, X.; DeRyckere, D.; Graham, D.K. The Emerging Role of TYRO3 as a Therapeutic Target in Cancer. Cancers 2018, 10, 474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, L.; Ouyang, H.; Xu, X.; Du, Y.; Ti, X. Mutational landscape of homologous recombination-related genes in small-cell lung cancer. Cancer Med. 2023, 12, 4486–4495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tlemsani, C.; Takahashi, N.; Pongor, L.; Rajapakse, V.N.; Tyagi, M.; Wen, X.; Fasaye, G.-A.; Schmidt, K.T.; Desai, P.; Kim, C.; et al. Whole-exome sequencing reveals germline-mutated small cell lung cancer subtype with favorable response to DNA repair-targeted therapies. Sci. Transl. Med. 2021, 13, eabc7488, Erratum in: Sci. Transl. Med. 2021, 13, eabm6064. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.abm6064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Knelson, E.H.; Patel, S.A.; Sands, J.M. PARP Inhibitors in Small-Cell Lung Cancer: Rational Combinations to Improve Responses. Cancers 2021, 13, 727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kong, R.; Patel, A.S.; Sato, T.; Jiang, F.; Yoo, S.; Bao, L.; Sinha, A.; Tian, Y.; Fridrikh, M.; Liu, S.; et al. Transcriptional Circuitry of NKX2-1 and SOX1 Defines an Unrecognized Lineage Subtype of Small-Cell Lung Cancer. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2022, 206, 1480–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rekhtman, N. All That Is Small Is Not a Small-Cell Carcinoma: Thoracic SMARCA4-Deficient Undifferentiated Tumors Masquerading as SCLC. Clin. Cancer Res. 2024, 30, 1708–1711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Milbury, C.A.; Creeden, J.; Yip, W.-K.; Smith, D.L.; Pattani, V.; Maxwell, K.; Sawchyn, B.; Gjoerup, O.; Meng, W.; Skoletsky, J.; et al. Clinical and analytical validation of FoundationOne®CDx, a comprehensive genomic profiling assay for solid tumors. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0264138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Genomic Alteration (N, %) | Primary Tumors (n = 26) | Metastatic Sites (n = 29) | Significance (p Value) |

|---|---|---|---|

| TP53 gene | 26 (100%) | 28 (97%) | 0.527 |

| missense | 19 (73%) | 16 (55%) | 0.136 |

| truncating | 8 (31%) | 12 (41%) | 0.297 |

| RB1 gene | 19 (73%) | 26 (90%) | 0.107 |

| PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway | 17 (65%) | 17 (59%) | 0.407 |

| PTEN * | 3 (12%) | 9 (31%) | 0.076 |

| Chromatin regulators | 16 (62%) | 7 (24%) | 0.005 |

| NOTCH pathway | 5 (19%) | 3 (10%) | 0.291 |

| MYC-family * | 5 (19%) | 8 (28%) | 0.342 |

| Cell cycle genes | 7 (27%) | 6 (21%) | 0.410 |

| Homologous repair genes | 5 (19%) | 5 (17%) | 0.561 |

| SOX2 | 8 (31%) | 19 (66%) | 0.010 |

| NKX2-1 | 5 (19%) | 19 (65%) | <0.001 |

| TYRO3 | 17 (65%) | 1 (3%) | <0.001 |

| SDHA | 4 (15%) | 3 (10%) | 0.437 |

| Genomic Alteration | Total (n = 55) | Female (n = 31) | Male (n = 24) | Significance (p Value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TP53 gene | 54 (98%) | 31 (100%) | 23 (96%) | 0.436 |

| missense | 35 (64%) | 25 (81%) | 10 (42%) | 0.003 |

| truncating | 20 (36%) | 6 (19%) | 14 (58%) | 0.003 |

| RB1 | 45 (82%) | 25 (81%) | 20 (83%) | 0.542 |

| PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway | 34 (62%) | 20 (65%) | 14 (58%) | 0.424 |

| PTEN | 12 (22%) | 10 (32%) | 2 (8%) | 0.033 |

| Chromatin regulators | 23 (42%) | 15 (48%) | 8 (33%) | 0.199 |

| NOTCH pathway | 8 (15%) | 6 (19%) | 2 (8%) | 0.225 |

| MYC-family | 13 (24%) | 5 (16%) | 8 (33%) | 0.121 |

| Cell cycle genes | 13 (24%) | 9 (29%) | 4 (17%) | 0.228 |

| Homologous repair genes | 10 (18%) | 5 (16%) | 5 (21%) | 0.458 |

| SOX2 | 27 (49%) | 12 (39%) | 15 (63%) | 0.069 |

| NKX2-1 | 24 (44%) | 11 (36%) | 13 (54%) | 0.133 |

| TYRO3 | 18 (33%) | 13 (42%) | 5 (21%) | 0.085 |

| SDHA | 7 (13%) | 5 (16%) | 2 (16%) | 0.331 |

| Characteristic | Total | Female | Male |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | 55 | 31 (56%) | 24 (44%) |

| Age, median (range) | 64 (43–87) | 65 (43–73) | 64 (53–87) |

| Stage at diagnosis | |||

| limited | 7 (13%) | 3 (10%) | 4 (17%) |

| extended | 48 (87%) | 28 (90%) | 20 (83%) |

| Survival, median | 8.5 | 8.0 | 9.0 |

| >24 months | 10 (18%) | 6 (19%) | 4 (17%) |

| Site of biopsy | |||

| primary tumor | 26 (47%) | 15 (48%) | 11 (46%) |

| metastasis, brain | 21 (38%) | 12 (39%) | 9 (38%) |

| metastasis, liver | 4 (7%) | 3 (10%) | 1 (4%) |

| metastasis, other | 4 (7%) | 1 (3%) | 3 (13%) |

| Biopsy type | |||

| FFPE | 34 (62%) | 17 (55%) | 17 (71%) |

| cytology | 21 (38%) | 14 (45%) | 7 (29%) |

| Tumor purity (%) | |||

| median (range) | 81 (24–98) | 80 (24–98) | 84 (29–98) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schmalz, D.; Krabóth, Z.; Czoma, V.; Urbán, P.; Gyenesei, A.; Ruzsics, I.; Sárosi, V.; Boronkai, Á.; Papp, E.; Kajtár, B. Comprehensive Genomic Profiling of Small-Cell Lung Cancer Reveals Frequent Potentially Targetable Alterations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11512. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311512

Schmalz D, Krabóth Z, Czoma V, Urbán P, Gyenesei A, Ruzsics I, Sárosi V, Boronkai Á, Papp E, Kajtár B. Comprehensive Genomic Profiling of Small-Cell Lung Cancer Reveals Frequent Potentially Targetable Alterations. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11512. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311512

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchmalz, Dániel, Zoltán Krabóth, Veronika Czoma, Péter Urbán, Attila Gyenesei, István Ruzsics, Veronika Sárosi, Árpád Boronkai, Emőke Papp, and Béla Kajtár. 2025. "Comprehensive Genomic Profiling of Small-Cell Lung Cancer Reveals Frequent Potentially Targetable Alterations" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11512. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311512

APA StyleSchmalz, D., Krabóth, Z., Czoma, V., Urbán, P., Gyenesei, A., Ruzsics, I., Sárosi, V., Boronkai, Á., Papp, E., & Kajtár, B. (2025). Comprehensive Genomic Profiling of Small-Cell Lung Cancer Reveals Frequent Potentially Targetable Alterations. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11512. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311512