Abstract

There is increasing interest in using magnesium (Mg) alloy orthopedic devices because of their mechanical properties and bioresorption potential. Concerns related to their rapid degradation have been issued by developing biodegradable micro- and nanostructured coatings to enhance corrosion resistance and limit the release of hydrogen during degradation. This systematic review based on four databases (PubMed®, Embase, Web of Science™ and ScienceDirect®) aims to present state-of-the-art strategies, approaches and materials used to address the critical factors currently impeding the utilization of Mg alloy devices. Forty studies were selected according to PRISMA guidelines and specific PECO criteria. Risk of bias assessment was conducted using OHAT and SYRCLE tools for in vitro and in vivo studies, respectively. Despite limitations associated with identified bias, the review provides a comprehensive analysis of preclinical in vitro and in vivo studies focused on manufacturing and application of Mg alloys in orthopedics. This attests to the continuous evolution of research related to Mg alloy modifications (e.g., AZ91, LAE442 and WE43) and micro- and nanocoatings (e.g., MAO and MgF2), which are developed to improve the degradation rate required for long-term mechanical resistance to loading and excellent osseointegration with bone tissue, thereby promoting functional bone regeneration. Further research is required to deeply verify the safety and efficacy of Mg alloys.

1. Introduction

Titanium, cobalt–chromium-based alloys and stainless steels are widely used in orthopedics for fixation devices and joint prostheses due to their favorable mechanical properties, corrosion resistance and ability to biologically integrate with the human body (biocompatibility) [1]. Recently, bioresorbable fixation devices have been proposed for certain surgical procedures, such as osteotomies of small bone segments or at the epiphysis level, even in long bones like hallux valgus. These devices do not interfere with X-ray imaging techniques and eliminate the need for a second surgery, which could pose potential risks to the patient and additional costs [2,3].

There is considerable interest in the new generation of orthopedic devices manufactured from magnesium (Mg) and its alloys. Mg and its alloys exhibit favorable biocompatibility and mechanical properties. Indeed, Mg possesses several advantageous mechanical properties: a Young’s modulus of approximately 41–45 GPa, a considerable range of elongation from 3% to 21.8% and an ultimate tensile strength ranging from 160 to 263 MPa. These values are notably close to those exhibited by bone, differentiating Mg from other materials commonly used in orthopedics. With a high specific strength (strength-to-weight ratio of about 130 kN m/kg) and good energy absorption capability, even in load-bearing applications, Mg emerges as a promising candidate in orthopedics. These characteristics contribute to reducing the occurrence of stress shielding phenomena in various procedures [4]. Additionally, its density, ranging from 1.74 to 1.84 g/cm3 depending on alloying composition, is comparable to that of bone (1.8–2.1 g/cm3), endowing Mg with a lightweight quality. [5]. Although there are concerns about the biocompatibility of Mg-based alloys due to their rapid degradation, it is important to note that the degradation products, including non-toxic Mg ions, promote bone formation, angiogenesis and stimulate bone healing [6]. Magnesium is a cofactor for many enzymes in human metabolism and is also involved in tissue-healing; of note, extra Mg2+ do not cause cytotoxicity in the human body and are eliminated through urine [7]. Nevertheless, rapid corrosion in aqueous environments, caused by a low standard electrode potential (−2.37 V), can lead to negative surgical outcomes, such as bone fractures and the release of hydrogen gas. This gas can form bubbles around the implant, accumulating and expanding, thereby impairing the stability of the local microenvironment. Displacement or rupture of the peri-implant tissues may occur, as well as compression of peripheral vessels, leading to cellular damage, pH alteration and, in the worst case, necrosis and bone erosion. From a mechanical standpoint, a too-fast degradation process can compromise the favorable characteristics of the Mg alloy: swift corrosion will harm the mechanical integrity of the Mg implants, resulting in the rapid release of the aforementioned products (hydrogen and hydroxide ions). Consequently, it is imperative to control the degradation rate of Mg implants to ensure an appropriate spatiotemporal complementarity between bone regeneration/remodeling and Mg implant degradation, thereby avoiding compromising the structural integrity. This approach can prevent potential harm to patient health and reduce overall healthcare costs [8].

The use of coatings represents a strategy to improve corrosion resistance and reduce hydrogen release during the degradation of magnesium alloys. Thanks to the advent of the nanotechnologies, nanostructured coatings can also be obtained, further improving the protective barrier function, to limit the contact between the metal surface and environmental elements such as oxygen, water and other chemicals, thereby preventing corrosion. Additionally, coatings can act as a sacrificial layer, allowing the metal to corrode on top of the coating—which can help to slow down the corrosion process and decrease the amount of hydrogen emitted. Coatings can function as a hydrogen diffusion barrier, diminishing blistering, cracking and other damage resulting from the excessive release of hydrogen during Mg alloy degradation. Biodegradable surface coatings can significantly impede rapid degradation and enhance the biological activity of magnesium alloys. Coatings are typically applied to magnesium alloys through mechanical, physical, chemical or biological techniques. The coatings can be divided into metallic coatings such as metal oxides, ceramic coatings or polymeric coatings consisting of both synthetic and natural polymers [9,10].

The objectives of this systematic review, prepared following the PRISMA guidelines [11], were to evaluate the latest approaches, coating materials and strategies proposed up to 2022 for Mg alloys, to address bias risks in the analysis of collected individual studies and to identify the most effective strategies to overcome issues hindering the use of Mg-alloy-based devices. The study commenced with an evaluation of the literature on medical devices for orthopedic applications, specifically examining Mg-based alloys and their possible use in orthopedics. The research focused on the factors that improve osseointegration and probed viable solutions to mitigate the corrosion of these alloys.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Eligibility Criteria

Eligibility criteria defined by the PECO (population, exposure, comparison, outcome) statement were used to select the studies included in the current systematic review. The population of interest (P) was differentiated according to the experimental study models considered: preclinical models, in vivo and in vitro, concerning the use of magnesium alloys for the realization of orthopedic devices. Preclinical in vitro studies included experimental models using human or animal cell lines (except non-mammalian) or primary cells, such as mesenchymal stem cells and osteoblasts, used in monolayer cultures, co-cultures and three-dimensional culture models. For in vivo studies, the following models were included: rodents (e.g., rats and mice of any strain), lagomorphs, sheep and any other experimental animal, without restriction as to sex, age, species, in which such alloys have been surgically implanted in bone to study their osseointegration. The exposure of interest (E) will be magnesium-alloy-based devices, coated or uncoated, or with functionalized surfaces or any other surface modification that improves the osseointegration of such devices. The comparator (C) will be any animal or cell treatment group not exposed to magnesium-alloy-based devices or any cell treatment group exposed to vehicle control only or any animal or cell treatment group exposed to a control alloy already in clinical use, such as a titanium alloy (e.g., Ti6Al4V), which has also been the reference group in clinical trials. Studies without a reference group were excluded. As for the population, the outcomes (O) were also differentiated according to the type of model considered. For in vitro models, the primary outcome was cell adhesion, proliferation/viability and bone matrix deposition and the secondary outcomes were an increase in gene expression (e.g., PCR) and/or specific protein synthesis (e.g., ELISA) related to the osseointegration process. For in vivo models, the primary outcome was the histological appearance of osseointegration of the implanted device and the secondary outcomes were increases in bone histomorphometric parameters such as bone-to-implant contact.

2.2. Search Strategy

The bibliographic search was conducted in four databases according the indications of the PRISMA guidelines [11] in the period between 2012 and 2022. All references identified by the search were uploaded to the Rayyan Systematics Reviews research tool (https://www.rayyan.ai/) and duplicate references, narrative and/or systematic reviews, editorial conference abstracts and non-English references were eliminated. The collected references were then assessed for relevance to the current review topic by reading the full text and irrelevant references to population (e.g., animal cell lines and/or primary mesenchymal stem cells and/or osteoblasts), exposure (e.g., magnesium alloy) or outcome (e.g., cell viability, histomorphometric parameters) were excluded. An evaluation of the bibliographic references of the selected papers was also carried out to assess whether further articles could be considered related to the topic of the current review and, if necessary, added manually.

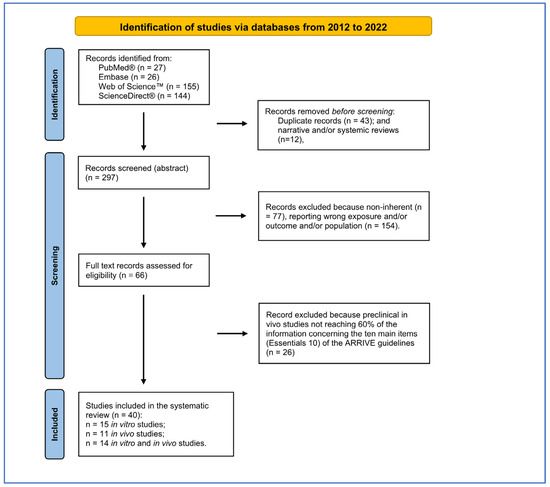

This evaluation/selection activity was carried out independently by four authors (D.B., A.D.L., V.C., L.R.) and any uncertainties in the choice of references were resolved by joint evaluation with the intervention of a supervisor (M.F., G.G.). The summary flowchart of the entire reference selection process is reported in Figure 1. Subsequently, two authors (D.B., V.C.) performed a further selection of the selected references of the in vivo preclinical studies, considering those references that reported at least 60% of the information on the ten essential points (Essentials 10) of the ARRIVE guidelines (Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments guide) [12] that should be included in a publication reporting the results of animal research. These guidelines ensure that studies are reported in sufficient detail to allow adequate evaluation of the research from a methodological point of view and to allow possible replication of the methods or results. Finally, the selected studies were imported into Zotero (v. 6.0.19), which was used as the reference manager.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram followed for reference selection process.

2.2.1. Databases

The following databases were used for the literature search:

- PubMed®—https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ (accessed on 12 December 2022)

- Embase—https://www.embase.com/ (accessed on 13 December 2022)

- Web of Science™—https://access.clarivate.com/ (accessed on 12 December 2022)

- ScienceDirect®—https://www.sciencedirect.com/ (accessed on 14 December 2022)

2.2.2. Search Strings

The PubMed® search string used a combination of MeSH keywords and Boolean operators (AND/OR/NOT) based on parameters defined in the PECO instruction’s Exposure and Outcome sections. This string was adapted and calibrated to work on Embase, Web of Knowledge and ScienceDirect. Additional supporting information on the search string structure is available in Supplementary File SA.

2.3. Parameters Extracted from the Studies

The data extraction method was defined by three reviewers (G.G., D.B., L.R.) to obtain all the information necessary for (Table 1): (1) the risk of bias assessment for in vitro studies (Cochrane RoB2 and OHAT) [13,14]; (2) the evaluation of risk of bias for in vivo studies (SYRCLE) [15] and (3) to report results [14].

Table 1.

Selected in vitro studies included in the systematic review.

2.4. Risk of Bias Assessments within Individual Studies

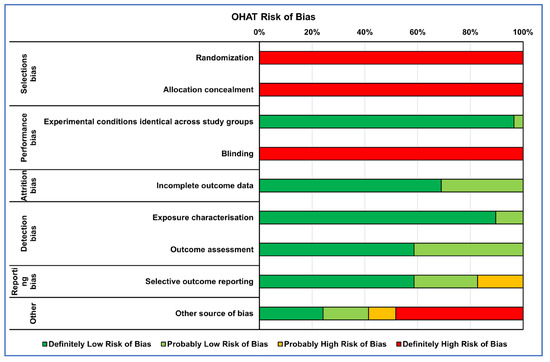

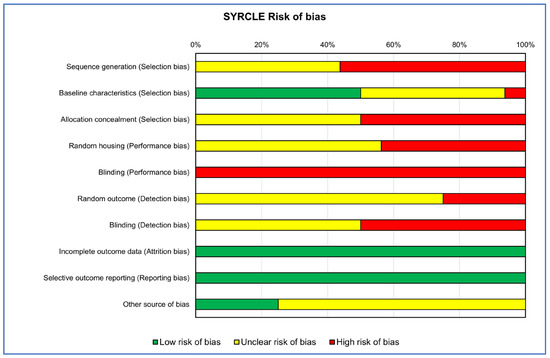

The collected references’ internal quality was assessed by two reviewer groups using risk of bias (RoB) evaluation: one for in vitro studies (A.C., V.C., A.D.L. and L.R.) and the other for in vivo studies (D.B., V.C. and G.G.). Each group conducted an independent assessment. If differences in assessments arose, these were resolved through collegial discussion or with the intervention of a supervisor (M.F. or G.G.) if no agreement was achieved. There is presently no validated tool for assessing the internal validity of in vitro studies. The tools used to date, including Cochrane RoB2 and OHAT, are based on those created for either human or animal studies and cover similar areas. Therefore, to assess the RoB of the in vitro studies, we used OHAT’s tool, which comprises a set of evaluation criteria that are common to each test’s experimental flow. These criteria target the main domains of bias, including selection bias, performance bias, attrition bias, detection bias, selective reporting bias and other sources of bias. For each domain, five alternative responses were available for each question. “Definitely Low Risk of Bias”, “Probably Low Risk of Bias”, “Probably High Risk of Bias”, “Definitely High Risk of Bias” or “Not Reported”. Regarding the assessment of the RoB in in vivo preclinical studies, we utilized the SYRCLE RoB tool, which shares the same bias domains as the OHAT tool. The SYRCLE RoB tool provides three possible answers: “Low risk of bias”, “Unclear risk of bias” and “High risk of bias”.

3. Results

The bibliographic search led to the selection of 352 records from four search engines (Figure 1). After 43 duplicates and 12 reviews were removed, the remaining 297 records were screened using Rayyan software. The PRISMA checklist is reported as Supplementary File SB.

Two-hundred-thirty-one records were excluded because they did not correspond to the eligibility criteria defined by PECO, reported incorrect populations, exposures or outcomes or were narrative reviews. Of the 66 records assessed for eligibility, 26 records were excluded because they did not reach 60% of information required by the ten main elements (Essentials 10) of the ARRIVE guidelines. Of the forty records selected, fifteen concerned in vitro studies, eleven were in vivo studies and fourteen were in vitro and in vivo (nine were considered only for the in vitro part because the in vivo part did not reach 60% of the Essential 10 of ARRIVE). The list of items extracted from in vitro and in vivo studies have been in the Supplementary File SC.

3.1. Risk of Bias Assessment

The RoB evaluation of the studies reporting both in vitro and in vivo data was performed using OHAT and SYRCLE tools for the in vitro and in vivo parts, respectively, receiving those studies’ two RoB evaluations. RoB summaries are presented through heatmaps (Figure 2 and Figure 3). The selection bias mainly concerned the methods of assigning the experimental models to the various treatments, which did not occur in random assignment or were not described, leading precisely to the risk of selection of the best models for certain treatments, influencing the experimental results (high risk of bias in vitro: 100%; in vivo: 38%). Also, for the performance bias, both the method of assignment and the researchers’ knowledge of the treatments assigned to specific models could have led to the risk of overestimating the performance of a treatment (high risk of bias in vitro: 50%; in vivo: 72%). As regards the detection bias of the in vivo studies, the analysis conducted on the selected literature highlighted how this was mainly determined by the lack of a methodology for analyzing the blinded results or the assignment of cases to be analyzed always being random (high risk of bias in vivo: 38%).

Figure 2.

Heatmap of percentage OHAT RoB for in vitro studies.

Figure 3.

Heatmap of percentage SYRCLE RoB for in vivo studies.

Finally, for both types of study, the results of ‘Other sources of bias’, counted for in vitro studies as ‘Definitely high risk’ for 45% and for those in vivo as ‘Unclear risk of bias’ for 65%, were due to not clearly reporting which software or statistical test was used for the analysis and, if present, often not suitable for that type of data, as well as not reporting a priori power analysis, especially for in vivo studies, and the significance level adopted.

3.2. Narrative Results Synthesis

3.2.1. In Vitro Studies

The high degradation rate of Mg alloys represents one of the major issues to handle to improve their biocompatibility and osseointegration capability. The results of the literature review indicate that efforts to modify the properties of magnesium (Mg) can be classified into three main lines of action, which are often interconnected: (i) the development of alloys that combine Mg with key elements; (ii) the exploration of novel surface treatment techniques, also able to create and/or incorporate nanostructures, aimed at controlling Mg degradation, improving biocompatibility and enhancing interactions with cells and tissues involved in the healing process (e.g., micro-arc oxidation, MAO) and (iii) the exploiting of organic/inorganic nanocomposites, which play a crucial role in bone metabolism due to their biomimetic and structural properties, thereby promoting cell growth. The synthesis of in vitro results follows these three main lines of action. Table 1 reports the in vitro studies selected on the osseointegration capability of Mg-based alloys, uncoated (mainly control groups) or coated with various functionalized surfaces, ranging from inorganic to more complex treatment until nutraceuticals.

In Vitro Studies of Mg Alloys without Coatings

In vitro studies provide compelling evidence demonstrating that functionalizing Mg with elements of various natures (e.g., germanium, zirconium, rare elements like gadolinium, silver, strontium, etc.) significantly enhances the performance of the material. These improvements manifest in terms of enhanced cellular viability, improved adhesion characteristics and increased osteogenic differentiation capability of the investigated cell types [16,17,18].

In Vitro Studies of Mg Alloys with Inorganic Coatings

In addition to the creation of Mg alloys with the different elements, positive results were also obtained through the exploration of different innovative surface modification techniques. Surface modification is an effective way of altering the biological performance of an implant device. Surface properties, including hydrophilicity, roughness and chemical composition, play important roles in cellular and bacterial responses.

For example, micro-arc oxidation (MAO), an electrochemical surface approach to generate a microporous and adherent coating of alloy, was used by Liu et al., who added lithium (Li) to AZ91 alloy (Li-MAO) to improve the angiogenic and osteogenic activity of Mg, obtaining a nanoporous coating [19]. The direct and indirect interaction of rat bone mesenchymal stromal cells (rBMSCs) with MAO, Li-MAO and AZ91 samples showed that rBMSCs spread better in MAO and Li-MAO surfaces in comparison with AZ91 control substrate, affected by corrosion and wider corrosive gaps. Li-MAO improved the proliferation of cells, the expression of high levels of genes connected to the osteogenic differentiation as runt-domain transcription factors 2 (Runx-2), alkaline phosphatase (Alp), collagen type I alpha 1 chain (Col1a1) and osteocalcin (Ocn) and an increase in mineralization nodule formation compared to AZ91 alloy. Through the Western blot assay, Liu et al. hypothesized that the nanoporous Li coating positively influenced osteogenic differentiation by activating the Wnt/β-catenin pathway. The authors carried out other investigations that showed no differences in the corrosion resistance between MAO and Li-MAO, which was in any case superior to that of AZ91, and which highlighted the better angiogenic capacity of Li-MAO.

The efficiency of the MAO approach was also investigated by Shangguan et al., who compared the biological effects of calcium-phosphate (Ca-P)-contained MAO coating, pulse electrodeposition (PED) Ca-P coating and strontium phosphate (SrP) conversion coating in MC3T3-E1 cell line [20]. A cell viability assay revealed that cells cultured with extracts derived from Ca-P MAO increased their proliferation rate, and, after 7 days of treatment, high levels of ALP protein release, especially in the Ca-P MAO group, followed by the Sr-P coating, were observed compared to other samples. Following the possibility of using Mg alloy as a delivery of soluble factors to improve its osteointegration attitude, Kim et al. modified AZ31 alloy through layer-by-layer coating (LBL), the MAO approach and hydrothermal treatment (HT) for 24 h with Bone Morphogenetic Protein (BMP)-2 at various concentrations (20, 50 or 100 ng/mL). These biomaterials were tested indirectly for proliferation and osteogenic abilities on MC3T3 cell lines [21]. The data suggested a strongly positive effect of BMP50 and 100 coated to AZ31 on cell adhesion ability and ALP expression compared to other samples.

Xie et al. used the plasma electrolytic oxidation (PEO) technique to modify the surface of the Mg alloy, fabricating through simple immersion processes a construct of manganese (Mn) and iron (Fe) oxyhydroxide duplex layers on the PEO-treated AZ31 (PEO-Mn/Fe) [22]. Through this combined approach, the authors deeply explored the possibility of using rare earth elements to improve corrosion resistance and limit the release of ions. The C3H10T1/2 cells were seeded onto the scaffolds, and bioactivity data revealed that the PEO-Fe/Mn scaffold promotes cell growth, alkaline phosphatase activity and bone-related gene expression after 3–7 days of treatment. Furthermore, Li et al. tested biofunctional zinc (Zn) and Fe co-decorated Mg-based implants with nanoflower morphology using zinc-doped ferric oxyhydroxide nanolayer Mg alloy (PEO-FeZn, PEO-Fe and PEO-Zn) [23]. The results demonstrated that direct contact of PEO-Fe and PEO-FeZn1 and PEO-Zn2 on C3H10T1/2 cell line induced an increase in cell proliferation, ALP release and mRNA expression of Runx2, Al, Ocn and Opn during the experimental times. Meanwhile, the mineralization efficiency evaluated by Alizarin Red S (ARS) assay showed that the PEO-FeZn2 group displayed an increase in mineralization nodules formation compared to other samples. Li et al. investigated the possible use of hydroxyapatite (HA) as an outer layer of a ceramic coating of Mg alloy combining PEO and hydrothermal treatment, validating the osteoinductive role of a new bilayer-structured coating (termed HAT). This coating comprises an outer layer of HA nanorods and an inner layer of pores-sealed MgO with HA/Mg(OH)2 [24]. Viability assessment on Rabbit Mesenchymal Stromal Cells (RBMSCs) and human fetal osteoblast cell line (hFOB) 1.19 seeded on the HAT-coated Mg alloys revealed an increase in proliferation, as well as bone sialoprotein and osteopontin secretion and formation of mineralization nodules. Meanwhile, the mineralization efficiency evaluated by Alizarin Red S assay showed that the PEO-FeZn2 group displayed an increase in mineralization nodules formation compared to other samples.

Another way to enhance the corrosion resistance and cytocompatibility of AZ31 scaffolds is the use of fluoride treatment to acquire an MgF2 coating. Yu W et al. revealed that the MgF2-coated AZ31 (FAZ31) scaffolds enhanced proliferation, attachment and osteogenic ability of rBMSCs maintained on FAZ31 more than on AZ31 scaffolds [25]. Another biomimetic compound to increase Mg scaffold osteointegration and biocompatibility is fluoridated hydroxyapatite (FHA). FHA coating possesses a nanoneedle structure that can mimic collagen fibers and is derived from hydroxyapatite (HA), where OH- in the HA lattice is substituted with F- to form FHA. FHA nanocoatings, due to their optimal biocompatibility, biodegradability and osteogenic properties, can be easily coated onto biodegradable Mg substrates by electrochemical deposition because they are more stable, with low dissolution and high cell response. Shen et al. demonstrated the biological effects of direct contact of AZ31 alloy coated with a biomimetic FHA and HA via a microwave aqueous approach with MC3T3-E1 cell line. The data revealed that FHA and HA coatings promoted a reduction in cell proliferation and an increase in osteogenic differentiation, as confirmed by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) analysis and ALP staining [26] The role of FHA was also described by Cao Z. et al., who investigated the bioactivity role of FHA and tantalum (Ta) on Mg samples in MC3T3 cell lines [27]. The obtained data suggested that the combination of the nanoneedle structure and Ta ion’s function would synergistically enhance the osteogenic properties and cell proliferation of Mg/FHA and Mg/FHA/Ta groups more than on another sample.

Plasma immersion ion implantation (PIII) was used to realize a functionalized titanium oxide (TiO2) in TiO2/Mg2TiO4 nanolayer on the surface of WE43 magnesium by Lin Z et al., 2019 [28]. Adopting this approach, the investigated cells displayed an increase in cell viability and an induction of ALP protein release, osteogenic markers expression and mineralization nodules deposition after 14–21 days of treatment with the TiO2/Mg2TiO4 nanolayer compared to the WE43 control alloy.

Cheng et al. evaluated the effects of pure Mg alloy uncoated or coated with layered double hydroxides (LDH) (Mg-Al LDH and Mg(OH)2) on MC3T3-E1 maintained with derived extract alloys [29]. The cells treated with Mg-Al LDH samples displayed significantly higher cell proliferation, osteointegration abilities and mineralization nodules deposition amount compared to other samples. These data were also confirmed by Cheng et al., who investigated nanostructures of AZ31 Mg alloy treated with a Mg−Al layered double hydroxide (AZ31 Al-LDH) with the same cell line model [30].

Zhang et al. presented evidence of the effect of osteogenic markers expression after co-treatments with Ca–P-coated, Sr–P-coated and uncoated Mg–Sr alloy discs, immersed in different pH grading solutions, on an RMSCs model [31]. After 7 and 21 days of culture, RMSCs on Sr–P coating showed an increase in cell proliferation, ALP release and mineralization nodules formation compared to the other groups. The same effect on proliferation and osteogenic differentiation was observed in MC3T3-E1 cell line treated with extracts derived by AZ91-3Ca Mg alloy modified using diammonium hydrogen phosphate and calcium nitrate (both named CP) to obtain CP4100 and CP710 by Ali et al. It was demonstrated that CP4100 and CP710 induce an increase in proliferation, cells adhesion and osteogenic markers expression of Runx-2, Col-1a and Alp compared to AZ91-3 Ca Mg alloy [32].

Regarding the third line of action, hydroxyapatite (HA), the most important inorganic component of human bones, was investigated as coating for Mg also doped with Sr at different concentrations in comparison to uncoated ZK60 Mg alloy. The rBMSCs maintained on the surface of the alloys showed an increase in proliferation ability and osteogenic genes expression, as well as ALP protein release, in Sr-doped HA-coated samples compared to the HA-coated alloys [33]. In order to improve the stability, compact structure and efficiency of the osteointegration process of HA coatings on Mg alloys, You et al. developed a series of HA-based coatings through a hydrothermal treatment of brushite precursor (DCPD) [34]. MC3T3-E1 cell lines seeded on Mg DCPD revealed an increase in cell viability, mitochondrial activity, cell adhesion and osteogenic differentiation.

The electrospinning process was used by Perumal et al. to realize a cylindrical mesh cage implant with circular holes of AZ31 magnesium coated with a nanocomposite material containing polycaprolactone (PCL) at different percentages, pluronic F127 and nanohydroxyapatite (nHA), which significantly improve viability, osteogenic activity and mineralization activity of MG63 in comparison to AZ31 alloy alone [35].

In Vitro Studies of Mg Alloys with Organic Coatings

The effects of AZ31 Mg alloy coated with corrosion-resistant silane enriched with high- and low-molecular-weight hyaluronic acid (HA) (hHA-AZ31 and l-HA-AZ31) were tested in correlation with titanium alloy coated in the same way by Agarwal et al. Biocompatibility tests revealed that HA-Ti had the ability to increase cell proliferation, adhesion and osteogenic gene expression [36].

Another compound useful for medical applications is dexamethasone (Dex), a type of corticosteroid well-known to facilitate osseointegration. Lee J.H. et al. investigated the effects of direct contact of Mg coated with Dex/Black phosphorus (BP)/poly(lactide-co-glycolide)(PLGA) with the MC3T3 cell line. The results highlighted a strong proliferation and osteointegration ability of Mg-Dex/BP/PLGA compared to the control alloy [37].

Peng et al. fabricated through hydrothermal film a Zn-contained polydopamine (PDA) film to coat AZ31 in order to enhance osteogenic abilities and also improve antibacterial and anti-inflammatory action [38]. The extracts derived by these alloys were used to evaluate some main biological parameters like proliferation ability and adhesion, which were enhanced by coatings in comparison to the control alloy for MC3T3-E1 cell line. qRT-PCR analysis of osteogenic genes and ALP protein release on cells highlighted no differences in the expression of Runx-2 and collagen type II A (Coll II A) between the different coatings. Moreover, the extract of the Zn-contained PDA-coated sample was able to activate RAW264.7 polarization to the M2 phenotype (anti-inflammatory type) compared to the control alloy, suggesting anabolic activity also from an immunological point of view.

The osteogenic role of extracts derived from AZ31 Mg alloy coated with HA or HA/chitosan–metformin (HA/CS-MF), through hydrothermal treatment, on MC3T3-E1 cells was also investigated by Li et al. [39]. The osteogenic data revealed a significant increase in the expression of osteogenic genes and ALP release in the AZ31/HA/CS-MF extract, indicating that the AZ31/HA/CS-MF had the strongest osteogenic induction ability compared to AZ31 and AZ31/HA. This was further confirmed by the results of the viability tests analysis.

Li et al. investigated the osteoimmunomodulation effects of curcumin WE43 Mg-coated alloy on reducing inflammation around an implant and favoring its osseointegration [40]. They fabricated a three-layered coating on Mg with a different combination of polylactic acid (PLA) containing curcumin-loaded F-encapsulated mesoporous silica nanocontainers (cFMSNs) in different amounts and dicalcium phosphate dehydrate (DCPD). The higher cFMSN content exhibited better corrosion protection of the Mg substrate at 21 days of immersion and the presence of curcumin induced an increase in ALP release, osteogenic genes expression and mineralization nodules deposition. Furthermore, curcumin release induced a rapid macrophage phenotype change from M1 to M2, significantly downregulating pro-inflammatory factors (TNF-α, IL-1β, iNOS) and upregulating anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-10, CD206, ARG), resulting in a higher immunomodulatory efficiency.

The role of Mg alloy on osteoclast activation and immunomodulation was investigated by Negrescu et al. [41]. The electrospinning technique was used to fabricate poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL) fibers loaded with coumarin (CM) and/or zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO) using the commercial AZ31 Mg alloy as single and combined formulas. The results obtained on RAW 264.7 cells treated with extracts of alloys revealed an increase in viable cells and an induction of macrophage–osteoclast differentiation, as shown by tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) staining and actin cytoskeleton staining of the receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand (RANKL)-stimulated RAW 264.7 cells.

Concerning this advantage, Cheon et al. investigated a new biomimetic alloy in which Ta was deposited onto the surface of a poly(ether imide) PEI coating on magnesium implants using a plasma ion immersion implantation (PIII) technique [42]. The Ta/PEI-coated Mg induced an increase in cell viability and ALP activity in the MC3T3-E1 cell line compared to PEI-Mg coated after 10 days of direct contact with them.

A recent investigation suggested the role of hyaluronic acid associated to berberine (HA/BBR) as a component of a new biomaterial with antibacterial properties. Zhang et al. tested the effects of this new biomaterial on MC3T3-E1 cell lines [43]. Cell viability and osteogenic analysis demonstrated that this innovative materials combination showed excellent cell compatibility and induced an increase in ALP release and calcium nodules deposition compared to other samples.

Pandele et al. investigated another biological component used as a biomimetic scaffold—resveratrol, which was covalently immobilized onto cellulose acetate polymeric membranes used as a coating on a Mg-1Ca-0.2Mn-0.6Zr alloy, named Mg-CA-Res [44]. The Mg-CA-Res induced a significant increase in cell proliferation (MC3T3 cell line), ALP activity and extracellular matrix mineralization after 7 and 14 days of treatment compared to Mg-CA.

3.2.2. In Vivo Studies

In vivo studies have shown that combining Mg alloy with organic/inorganic molecules is the most widely studied method for enhancing material properties. Thirteen selected in vivo studies evaluated the osseointegration capabilities of uncoated or coated Mg alloy with different types of inorganic and/or organic substances. Table 2 provides a summary of information from selected in vivo studies ordered by the biomaterial type investigated: Mg alloys without coating, those with simple or successive inorganic coatings and finally Mg alloys coated with organic molecules. The primary objective of all the included in vivo studies is to assess the degradation and/or resorption profile of the different materials and evaluate their replacement capabilities with newly formed bone.

Table 2.

Selected in vivo studies included in the systematic review.

In Vivo Studies with Mg Alloys without Coatings

Kleer et al. compared two different Mg alloys: La2 and LAE442 in comparison to porous ß-tricalcium phosphate scaffolds [45]. The gas formation evaluated with radiological examination indicates a similar distribution of gas accumulations in the musculature in the two Mg alloys and no gas formation in controls. The microtomography analyses showed that LA2 alloy was degrading faster and in a dis-homogeneous manner compared to the LAE442 alloy, which exhibited better osseointegration, suggesting its possible examination in weight-bearing bone defects [45].

Using the synchrotron (SRμCT), Krüger et al. assessed the degradation and osseointegration of Mg alloys combined with gadolinium (Gd) [8]. The authors implanted Mg-5Gd and Mg-10Gd screws in comparison with Ti screw and polyether-ether-ketone (PEEK), demonstrating better osseointegration and newly formed bone in degraded Mg alloy zones compared to the other two materials, where the bone results were more mature. However, Mg-10Gd was preferred compared to Mg-5Gd as it degraded faster and less homogeneously than Mg-10Gd [8].

A Mg-based biodegradable alloy with germanium (Ge) was developed by Bian et al. [16]. The selected Mg-3 Ge alloy showed good performance in terms of resorption with high resistance to degradation compared to other alloys and optimal osseointegration with the bone that grows onto the surface of the implant, with a possible complete reabsorption in three months [16].

Lindtner et al. showed that a biodegradable magnesium alloy based on WE43 (Mg-Y-Nd-HRE composition) has several advantages compared to implants that use other degradable implant materials, such as reinforced PLGA [46]. The study showed that the WE43 had a significantly greater BV/TV compared to the self-reinforced PLGA implants taken as a control in the early analysis (4 weeks of implantation). However, there were no significant differences observed at other times (12 and 24 weeks). Importantly, push-out testing revealed highly significantly greater shear strength (τu) in the Mg alloy in all implantation periods. Although it showed clear signs of local degradation, osseointegration was not impaired, as indicated by newly formed bone that covered the surface of degraded implant parts with the same degree of unaltered parts, without noticeable local or systemic inflammation. Furthermore, the WE43 alloy exhibited markedly superior bone–implant interface strength and a greater amount of peri-implant bone than the self-reinforced copolymeric controls [46].

Liu et al., investigated magnesium alloy with scandium (Sc), one of the rare earth elements, ref. [47] used in its β-phase, which had been reported to exhibit a shape memory effect (Mg-30% wt Sc alloy). With respect to animal studies, this alloy exhibited slow degradation, with an ions Sc release far from the chronic toxicity level of this element. Only a little gas generation was observed without bone homeostasis perturbation at the initial stage compared to the HP-Mg used as control, wherein the released gas influenced bone remodeling. However, a problem of this alloy is the possible excess presence of impurities (especially Fe, Ni and Cu) that must be controlled as this leads to too rapid degradation of the Mg alloy, resulting in an excessive release of Sc ions [47].

In Vivo Studies with Mg Alloys with Inorganic Coatings

Kopp et al. showed the long-term (18-month) osseointegration abilities of the Mg-Ca-Zn (ZX00MEO)-based Mg alloy screws when the surface was modified through plasma-electrolytic oxidation (PEO) compared to non-surface-modified screws [48]. Implanted screws showed improved absorption behavior through reduced degradation rates, faster bone formation and increased quality around the modified implants [48].

PEO techniques were also used for surface modification of the WE43-based locking plates and screws by Rendenbach et al. to evaluate osteosynthesis and osseointegration at 6 and 12 months [49]. Regarding radiological and histological screw and plate degradation, PEO-treated WE-43 implants showed high wear resistance, ensuring a good seal of the implant, as high degradation can lead to the failure of the fixation. Furthermore, the decrease in degradation also determined a low hydrogen gas release, reducing the associated risk of perturbation of bone healing. The bone–implant contact percentage (BIC) and lamellar bone quantification evidenced how PEO surface modification had beneficial effects, improving osseointegration. In fact, PEO surface modification of WE43 screws and plates had no impact on the surrounding bone quality in comparison to untreated implants, although the surrounding BV/TV was reduced in both implants when compared with unimplanted animals. However, no control with animals with a screw hole without an implant was performed, so it remains unclear if this effect was due to the biomaterial or the surgical procedure itself [49]. Xie et al. used a simple immersion process to construct Mn and Fe oxyhydroxide duplex layers on the PEO-treated AZ31 (PEO–Mn/Fe) implant, which showed the best corrosion resistance compared to other unmodified and modified alloys (AZ31, PEO AZ31, PEO-Mn AZ31, PEO-Fe AZ31) [22]. Furthermore, a rat femur implantation experiment showed that the PEO–Fe/Mn–coated AZ31 alloy had the best bone regeneration and osteointegration abilities. In fact, large voids between the formed bone and the implants were observed in the PEO and PEO–Mn groups, while the PEO–Mn/Fe group had increased bone formation compared to other implant groups and the bone adhered more closely to the implant surface, indicating it to be the most favorable for bone regeneration and osteointegration [22].

Witting et al., starting from their previous studies on LAE442 alloy in porous form, evaluated the effectiveness of coatings of magnesium fluoride (MF2), combined with polylactic acid (PLA) or Ca-P, in slowing the degradation of the LAE442 alloy in promoting osseointegration in a rabbit model, using TCP as a control [50]. Although the coating of MF2 improved the rapid degradation with gas formation of this alloy, it did not control it. The results relating to osseointegration indicated that the presence of Ca-P compared to the other coatings increased bone regeneration in terms of bone volume and newly formed trabeculae. Conversely, as regards the speed of degradation, PLA slowed down this process but did not control the strong gas production, which was better controlled by the Ca-P coating [50].

In the study of Cheng et al., where Zr and N ions were simultaneously added into AZ91 Mg alloys by plasma immersion ion implantation (PIII), it was observed that there was a change in implant volume and bone formation around the modified implants relative to simple AZ91 implants, which were used as the control [17]. It was shown that the modified implant volume decreased much more slowly, and there was a corresponding increase in the amount of newly formed bone relative to the controls. In addition to the increase in the amount of bone that formed on the implant surface, obvious gas evolution was not observed in the Zr-N-implanted AZ91 group, in contrast to the AZ91 implants, which had adverse effects on cell adhesion, growth and differentiation [17].

Yu et al. have used a fluoride treatment to acquire a MgF2 coating with better corrosion resistance compared to other coatings [25]. This coating had discrete biocompatibility and an effective corrosion protective layer, which enable abundant new bone formation in the defects, which grew into the pores of the scaffolds. An obvious resorption zone with void formation was observed around the AZ31 scaffolds, whereas the FAZ31 surface constituted a stable and biocompatible interface for the attachment of osteoprogenitor cells, as well as subsequent proliferation, differentiation, calcification and final bone formation [25].

A functionally modified TiO2/Mg2TiO4 nanolayer on WE43 implant, through the plasma ion immersion implantation (PIII) technique, was investigated by Lin et al. [28]. The increase in new bone formation adjacent to the treated WE43 was higher than that of the titanium control and untreated WE43. Furthermore, this layer seemed to exhibit photoactive bacterial disinfection ability when irradiated by ultraviolet light due to intracellular reactive oxygen species (ROS) production, indicating how the TiO2/Mg2TiO4 nanolayer in these implants can significantly promote new bone formation, suppress bacterial infection and contain the degradation of implants simultaneously. The obtained results also evidenced that not only did PIII-treated WE43 samples stimulate new bone formation significantly compared to untreated implants but they also restored the mechanical property of the formed bone similarly to the level of the surrounding mature bone.

In Vivo Studies with Mg Alloys with Organic Coatings

Finally, Li et al. investigated the role of a self-healing coating with a three-layered structure and containing curcumin at different concentrations, described above, in favoring osseointegration and modulating the inflammatory response to Mg alloy degradation [40]. Their multifunctional coatings showed high corrosion resistance four weeks after implantation, and those with the highest curcumin concentration (20FMSN) modulated its surrounding immune microenvironment towards anti-inflammation (downregulation of TNF-α, IL-1β and iNOS, as well as an upregulation of IL-10, CD206 and ARG), thus facilitating osseointegration compared to the coatings with moderate (10FMSN) and lowest (5FMSN) amounts of curcumin [40].

4. Discussion

In recent years, there has been a growing interest in devices based on magnesium alloys, with a focus on biocompatibility features, mechanical properties, performance and strategies developed or adopted to overcome the degradation drawback. This interest is clearly demonstrated by numerous studies, encompassing both experimental approaches and narrative as well as systematic reviews [4,51,52]. However, preclinical studies on these alloys still exhibit various biases, as highlighted in the current review through a risk analysis of the selected papers. In vitro studies were found to be particularly problematic due to selection bias, while in vivo studies were affected by performance bias, both of which can compromise internal validity. Selection bias is often caused by an inadequate or poorly described randomization process or non-concealed allocation, leading to an overestimation or underestimation of the exposure effect and resulting in inaccurate conclusions about the effectiveness of using these alloys. Furthermore, researchers’ awareness of the groups to which the assessed outcomes belong determines the latter, leading to unequal assessment of outcomes between groups and possible biased results. Additionally, more than 60% of the identified high risk of bias or probably/unclear risk of bias in the ‘other sources of bias’ category were attributed to the lack of consistent reporting of statistical information.

In general, the major critical aspect of Mg alloys is represented by its rapid degradation, which results in hydrogen formation in peri-implant tissues and consequent impairment of bone regeneration and limitation in the osseointegration process. To overcome this drawback, several types of alloy modifications have been proposed with the aim of ensuring more homogeneous and controllable degradation phenomena.

None of the modifications proposed in the studies selected for the review reported relief of post-implantation clinical complications in bone tissue. Mg alloys La2 and LAE442 showed slow and homogeneous degradation, more efficient in the LAE442 alloy with retention in device shape throughout the experimental time and providing a better osseointegration [45]. The strategy of adding specific elements like Ag or Gd to the Mg alloy did not lead to satisfactory results in terms of better control of degradation, both in in vitro and in vivo evaluations and in the cellular response to high doses of released Mg ions [18], although the results of osseointegration were interesting [8]. The addition of germanium (>2.5 wt% Ge) to achieve an increasingly better mechanical performance and biodegradability of the Mg alloy provided an improvement in corrosion resistance and a contained production of hydrogen at the implant site that did not affect its osseointegration [16]. The Mg-Y-Nd-HRE alloy, based on the WE43 one, also demonstrated superior osseointegrative capabilities compared to a polymeric control hypothesized for the fixation of small bone lesions [46]. Finally, the modification of WE43 alloy with the addition of Sc (Mg-30 wt%Sc) showed improvement in corrosion rate while still maintaining mechanical properties suitable for bone [47].

Another alternative used to control excessive corrosion of Mg alloys and improve their osseointegration is surface modification with overlay coatings. Literature findings, summarized in the present review, suggest how nanotechnologies serve as a highly valuable tool for modifying and improving the surfaces of Mg alloys. Nanoflowers, nanorods and nanoneedles represent some of the morphologies that can be adopted to modify Mg alloys’ surfaces by using MAO, PEO and hydrothermal treatment, MgF2, oxides or a combined scheme of surface modification techniques. These modifications have demonstrated beneficial properties such as bioabsorbable implant materials and have proven their safety and performance at the device level. MAO and PEO are similar processes involving the electrolysis of a conductive material immersed in an electrolyte but differ in terms of plasma generation, process control and the coating structures produced. MAO coatings often contain ceramic phases and may be porous, while PEO coatings are often denser and more uniform than those produced by MAO. In the studies selected in the current review, MAO was used to improve corrosion resistance and biocompatibility [19,20], as in the case of the results obtained for lithium MAO nanocoating [19]. Calcium phosphate MAO coating on Mg-Sr alloy exhibited the greatest performance in terms of alloy degradation, cell proliferation and alkaline phosphatase activity when compared to Sr-P and Ca-P PED coatings, suggesting it could hold potential for use in orthopedics [20]. Regarding the use of PEO, Kermasorb® demonstrated its biocompatibility and ability to reduce the rate of degradation of ZX00 alloy, which was also confirmed by the presence of residual material up to 18 months after implantation, and improved its osseointegration [48]. The ability of PEO to control the degradation rate was confirmed also for WE43 alloy, which is progressively depleted over the period of 12 months of implantation, resulting in improved osseointegration in part due to its moderate osteostimulative effect [49].

The most interesting results are obtained from multifunctional and composite coatings. PEO-treated Mg alloys’ performance was improved by adding nanobiofunctionalized monolayer or multilayer coatings through immersion or hydrothermal treatments [22,23,24]. The PEO-FeZn nanolayer on AZ31 alloy improved in vitro osteogenic differentiation and showed a specific antibacterial activity by blocking bacterial immune evasion and promoting activation of the NOX-ROS signaling axis of neutrophils [23]. The duplex nanosheet film with an inner layer of MnOOH and an outer layer of FeOOH on PEO-coated AZ31 alloy improved the ability to induce osteogenesis in vitro and bone regeneration and osseointegration in vivo due to the enhanced corrosion resistance and the timed release of bioactive ions (e.g., Mg, Fe and Mn) [22]. The bilayer-structured coating (HAT) composed of an outer layer of hydroxyapatite nanorods and an inner layer of pores-sealed MgO with HA/Mg(OH)2, was realized on Mg surface, adopting plasma electrolytic oxidation and hydrothermal treatment. This composite coating is able to modulate anti-inflammatory macrophage response, suppress osteoclastogenesis and facilitated the recruitment and differentiation of osteogenic cells in the surrounding environment [24]. The barrier effect of HAT against body fluids prevented them from reaching the Mg substrate, delaying its degradation and allowing the new bone to act as an additional, more pronounced barrier.

Single-step hydrothermal processing has shown promise in its ability to generate coatings with good adhesion and high crystallinity on rigid substrates. The Ca-P coatings deposited by the single-step hydrothermal method had the effect of reducing the degradation rate of AZ91-3Ca alloy by 60% and hydrogen gas evolution rate by 65% [32]. Additionally, they demonstrated better biocompatibility and viability and increased osteogenic differentiation when compared to pre-osteoblasts, according to in vitro studies. The association of MAO and hydrothermal treatment to immobilize different concentrations of BMP-2 on Ca-P coating improved biocompatibility, delayed the degradation rate of AZ31 and promoted bone formation through sustained BMP-2 release; the BMP-2 concentration was below 50 ng/mL [21].

MgF2-based coatings were proposed to coat AZ31 (FAZ31) and LAE442 (PLA- or CaP-P) alloys [25,50]. The latter was also supplemented with the addition of Ca-P or PLA, and there was an important improvement in corrosion resistance, biocompatibility and osteogenic activity in both studies. FAZ31 and Ca-P had superior osteoconductive and osteoinductive properties, increasing the osseointegration process. However, scaffolds with PLA coating degraded more slowly despite increased gas formation. Additionally, fluorinated hydroxyapatite (FHA) was used to coat AZ31 and AZ31B alloys [26,27]. The FHA coating, also in association with hydrothermal synthesis and magnetron sputtering, improved osteogenic differentiation in vitro and offered favorable long-term protection for Mg alloy, increasing the corrosion resistance of the implants [26,27].

Mg alloy coatings with metal nitrides and/or oxide layers, such as the combination of ZrN, ZrO2 and Al2O3 [17], TiO2 and Mg2TiO4 [28], layered double hydroxides (LDH) with Al(NO3)3 [29,30] or ceramics such as SrP and CaP [31], Sr-doped hydroxyapatite [33] or hierarchically structured hydroxyapatite [34], seem to enhance corrosion resistance by providing a favorable implant surface for cell adhesion, viability and growth, thus improving osteogenesis in vitro, which, in turn, further promotes bone regeneration and osseointegration. Furthermore, a self-antibacterial capability due to oxidative stress induced by ROS production has been highlighted for TiO2/Mg2TiO4 nanolayers [28].

Another interesting way to improve Mg alloy degradation rate, osteogenic and osseointegration potentials is the development of composite coatings [35,36,37,38,39,42]. Most of them enhance in vitro osteoblast differentiation and ECM mineralization, such as the combination of PCL/pluronic/nHA electrospun on AZ31 mesh cage [35], the high-molecular-weight hyaluronic-acid-functionalized silane-coated AZ31 Mg alloys (h-HA-AZ31) [36] or the double coating with osteogenic dexamethasone-loaded black phosphorus and poly(lactide-co-glycolide) (Mg-Dex/BP/PLGA) [37]. In addition, some composite coatings improve macrophages’ polarization into M2 phenotype to reduce inflammation, such as polydopamine films coupled with Zn ions deposited on hydrothermal-treated AZ31 alloy (Mg-Al LDH) [38] or hydroxyapatite/chitosan–metformin (HA/CS-MF) composite coating achieved on AZ31 alloy by hydrothermal treatment [39]. Although tantalum magnetron sputtering onto the surface of poly(ether imide) coatings demonstrates excellent corrosion protection, it does not show any evidence of osseointegration [42].

Finally, the inclusion of natural compounds such as resveratrol, coumarin, curcumin or berberine in coatings brought benefits in relation to their ability to modulate the inflammatory response, always deriving from the degradation of the Mg alloys [40,41,43,44]. The three-layered coating with its self-healing function containing different concentrations of curcumin reduced the rate of Mg alloy degradation and improved osteodifferentiation and osteointegration proportionally to the increasing concentration of curcumin [40]. The macrophage inflammatory activity and osteoclast differentiation response to AZ31 alloy coated with an electrospun composite of PCL fibers loaded with coumarin and/or ZnO nanoparticles were mainly influenced by the ZnO and coumarin presence, providing the best corrosion behavior and the most favorable response in terms of morphological behavior, cell survival and proliferation [41]. The covalent immobilization of resveratrol to CA coating applied to the Mg alloy proved to be effective in vitro in stimulating the vitality and differentiation of osteoblasts and mineralization of the extracellular matrix [44]. Very interesting, and equally complex, is the use of berberine associated with hyaluronic acid to create a multilayer antibacterial coating with a composite based on magnesium hydroxide and poly(alendronate sodium methacrylate)/poly(dimethyldiallylammonium chloride)/poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate on AZ31 Mg alloy (MgA-Mg(OH)2-PALNMA/PDADMAC/PEGDA). The topological structure of the composite pattern seems to be responsible for the high antibacterial capacity and its biocompatibility and osteogenic differentiation [43].

As far as methodology is concerned, the most frequently used cells in the in vitro studies were the Mouse Osteoblastic cell line MC3T3-E1 (62%) [17,18,20,21,26,27,28,29,30,34,37,38,39,42,43,44], followed by Osteosarcoma Cell Line MG63 (7%) [16,35], BMSCs (21%) derived from rat [19,33], rabbit, [24,31] or human [25,40], Mouse Fibroblast-like cell lines (CH3/10T1/2) (7%) [22,23] and Human Fetal Osteoblastic cell line (hFOB 1.19) (3%) [24]. Few studies also investigated the effects of different Mg alloys on the osteoclast cell activation using Mouse Macrophage cell line RAW 264.7 [38,39,40,41]. Most of the collected in vitro studies primarily adopted extracts methodology rather than direct cell-material contact, which imposes limitations on the extent of conclusions that can be drawn from the results. This methodological choice is likely attributed to the release of degradation products from the Mg materials upon contact with cells, which could potentially have adverse effects on cell cultures before the actual effects can be accurately determined. The search strategy did not yield any co-culture studies or advanced in vitro models, which could have introduced a higher level of complexity to the investigations and increased the relevance of the results. All the studies adopted the same tests to evaluate cell behavior in terms of viability (e.g., live and dead, MTT and CKK8), cell adhesion and morphology (e.g., SEM or confocal microscopy) and to understand the osteointegration capability of tested Mg-based alloys, such as qRT-PCR analysis of osteogenic genes, Western blot technique, ELISA assay, Alizarin Red and Sirius red dye staining for cellular and extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins.

For in vivo studies, the most used animal model was the rat (54%) [8,17,22,28,40,46,47], followed by the rabbit (31%) [16,25,45,50]; only two studies were carried out on a large animal model (minipig 15%) [48,49]. Regarding the implant site, the Mg alloy implants were inserted in femoral condyle (38%) [17,25,28,40,47], trochanter (23%) [22,45,50] or diaphysis (15%) [46,49], tibial metaphysis (15%) [8,16] and frontal bone (8%) [48]. In most of in vivo studies, the Mg alloy implants had porous cylinders (31%) [25,45,46,50] or non-porous cylindrical shapes (46%) [8,17,22,28,40,47] or sample screws (15%) [16,48] or plates fixed with screws (8%) [49]. All these studies used microtomography to evaluate in vivo and/or ex vivo degradation of implanted Mg alloys, while osseointegration was assessed through histological evaluation with different staining (e.g., hematoxylin–eosin; Toluidine Blue-Pyronine Y; Lévai–Laczkó, Giemsa, Van Gieson’s and Picrofuchsin). Out of the thirteen in vivo studies, only two of them specifically examined the mechanical competence of the bone tissue regenerated after Mg device implantation. Considering the unique characteristics of these materials, it is crucial to conduct more comprehensive investigations to accurately assess the quality and mechanical competence of the regenerated bone.

Although not an aim of this systematic review, an additional literature search was conducted to determine whether any of the approaches presented here had been evaluated at a higher level, including systematic reviews, meta-analyses and clinical trials. The search retrieved few studies, comprising a single systematic review and four studies (two pilot, one retrospective and one prospective) [2,53,54,55]. At least four of these papers referred to the use of the MgYREZr (magnesium, yttrium, rare earth and zirconium) alloy from Syntellix AG (Hannover, Germany), employed as a screw for the consolidation of comminuted fractures, hallux valgus and tibial osteotomies. Overall, these articles emphasized that the MgYREZr alloy is non-inferior to titanium screws in terms of biocompatibility, resistance to mechanical loading and not requiring removal due to its absorption and not producing artifacts in CT. Only one article referred to the use of Mg-5wt%Ca-1wt%Zn alloy, which demonstrated bone healing and complete resorption one year after treatment. This is attributed to the continuous degradation of the Mg alloy and the potential formation of a biomimetic calcification matrix (CCP) at the degradation interface, which may have contributed to the bone formation process [56].

5. Conclusions

This systematic review summarizes 40 preclinical in vitro and in vivo studies on the use of Mg alloys for the manufacturing of fracture fixation devices. The in vitro results indicate three main approaches to modify the properties of magnesium (Mg): (i) developing Mg alloys with key elements, (ii) exploring surface treatment techniques to control degradation and improve biocompatibility and (iii) using organic/inorganic nanocomposites to promote cell growth and mimic bone properties. Furthermore, in vivo studies have demonstrated extensive research on combining Mg alloys with various organic and inorganic molecules to enhance material properties, specifically focusing on osseointegration and modulation of material degradation. In particular, the review reveals the progress in research on Mg alloy modifications (e.g., AZ31, AZ91, LAE442 and WE43) and types of coatings (e.g., PEO, MgF2 and oxides) to achieve improved materials in terms of degradation rate. Ensuring long-term mechanical resistance to loading and excellent osseointegration with bone tissue are crucial to promote functional bone regeneration for fracture healing. Nanotechnologies have certainly improved this field of application, and the realization of nanostructures and/or nanocoating has certainly enhanced the characteristics of these peculiar materials by improving their corrosion resistance and osseointegrative properties.

Despite promising advances in Mg alloys, it is essential to emphasize that further investigation is necessary to establish and confirm their efficacy and safety, especially when the nanodimension is involved. Despite the limitations associated with selection, performance and detection bias, the present systematic review offers a broad overview of the development of Mg alloys for orthopedics. These limitations could have been mitigated by implementing rigorous research methodologies or guidelines to ensure reliable and comprehensive results.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijms25010282/s1.

Author Contributions

G.G.: Conceptualization, formal analysis, project administration, supervision, validation, writing—review and editing; D.B.: Conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, visualization, writing original draft; A.D.L.: Data curation, investigation, visualization, writing original draft; V.C.: Data curation, investigation, validation, writing original draft; L.R.: Conceptualization, data curation, investigation, validation, writing original draft; A.C.: Data curation, investigation; M.S.: Supervision, validation, writing—review and editing; S.T.: Supervision, writing—review and editing; A.T.: Supervision, writing—review and editing; G.P.: Supervision, writing—review and editing; M.F.: Supervision, writing—review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported partially by the Italian Ministry of Health—Ricerca Corrente and the Italian Ministry of University and Research—Industrial Research Project and not predominantly Experimental Development (area of specialization “Health”) [grant number ARS01_01205].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All data are available in the manuscript and in the Supplementary Files.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Abbreviation

Mg: Magnesium; PCR: Polymerase Chain Reaction; ELISA: Enzyme Linked Immunosorbent Assay; Rob: Risk of Bias; OHAT: Office of Health Assessment and Translation; SYRCLE: SYstematic Review Centre for Laboratory animal Experimentation; ARRIVE: Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments; Ti: Titanium; Ge: Germanium; Al: Aluminum; Zr: Zirconium; Ag: Silver; Gd: gadolinium; SEM: Scanning Electron Microscopy; Col1A1: Collagen type I alpha; Ocn: Osteocalcin; Sr: Strontium; Ca: Calcium; P: Phosphate; SrP: Strontium Phosphate; Mn: Manganese; Fe: Iron; Zn: Zinc; Bsp: Bone sialoprotein; Opn: Osteopontin; FHA: fluoridated hydroxyapatite; HA: Hydroxyapatite; Ta: Tantalum; HF: Hydrofluoric acid; nHA: nanohydroxyapatite; Li: Lithium; TCP: ß-tricalcium phosphate; Micro-CT: Micro-computed tomography; PEEK: Polyetheretherketone; MAO: Micro-Arc Oxidation; PED: Pulse Electrodeposition; PEO: Plasma Electrolytic Oxidation; HT: Hydrothermal Treatment; PIII: Plasma Immersion Ion Implantation.

References

- Jin, W.; Chu, P.K. Orthopaedic Implants. In Encyclopedia of Biomedical Engineering; Narayan, R., Ed.; Elsevier: Oxford, UK, 2019; pp. 425–439. [Google Scholar]

- Windhagen, H.; Radtke, K.; Weizbauer, A.; Diekmann, J.; Noll, Y.; Kreimeyer, U.; Schavan, R.; Stukenborg-Colsman, C.; Waizy, H. Biodegradable magnesium-based screw clinically equivalent to titanium screw in hallux valgus surgery: Short term results of the first prospective, randomized, controlled clinical pilot study. Biomed. Eng. Online 2013, 12, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangdal, S.; Singh, D.; Joshi, N.; Soni, A.; Sament, R. Functional outcome of ankle fracture patients treated with biodegradable implants. Foot Ankle Surg. 2012, 18, 153–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasr Azadani, M.; Zahedi, A.; Bowoto, O.K.; Oladapo, B.I. A review of current challenges and prospects of magnesium and its alloy for bone implant applications. Prog. Biomater. 2022, 11, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniac, I.; Miculescu, M.; Mănescu Păltânea, V.; Stere, A.; Quan, P.H.; Păltânea, G.; Robu, A.; Earar, K. Magnesium-Based Alloys Used in Orthopedic Surgery. Materials 2022, 15, 1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.F.; Gu, X.N.; Witte, F. Biodegradable metals. Mater. Sci. Eng. R Rep. 2014, 77, 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorentini, D.; Cappadone, C.; Farruggia, G.; Prata, C. Magnesium: Biochemistry, Nutrition, Detection, and Social Impact of Diseases Linked to Its Deficiency. Nutrients 2021, 13, 1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krüger, D.; Galli, S.; Zeller-Plumhoff, B.; Wieland, D.C.F.; Peruzzi, N.; Wiese, B.; Heuser, P.; Moosmann, J.; Wennerberg, A.; Willumeit-Römer, R. High-resolution ex vivo analysis of the degradation and osseointegration of Mg-xGd implant screws in 3D. Bioact. Mater. 2021, 13, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng-Zheng, Y.; Wei-Chen, Q.; Rong-Chang, Z.; Xiao-Bo, C.; Chang-Dong, G.; Shao-Kang, G.; Yu-Feng, Z. Advances in coatings on biodegradable magnesium alloys. J. Magnes. Alloys 2020, 8, 42–65. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Liu, W.; Ngai, T. Polymer coatings on magnesium-based implants for orthopedic applications. J. Polym. Sci. 2022, 60, 32–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. PLoS Med. 2021, 18, e1003583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- du Sert, N.P.; Hurst, V.; Ahluwalia, A.; Alam, S.; Avey, M.T.; Baker, M.; Browne, W.J.; Clark, A.; Cuthill, I.C.; Dirnagl, U.; et al. The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: Updated guidelines for reporting animal research. PLoS Biol. 2020, 18, e3000410. [Google Scholar]

- Sterne, J.A.C.; Savović, J.; Page, M.J.; Elbers, R.G.; Blencowe, N.S.; Boutron, I.; Cates, C.J.; Cheng, H.Y.; Corbett, M.S.; Eldridge, S.M.; et al. RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2019, 366, l4898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OHAT. Handbook for Conducting a Literature-Based Health Assessment Using OHAT Approach for Systematic Review and Evidence Integration; Office of Health Assessment and Translation (OHAT) Division of the National Toxicology Program National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, 2019. Available online: https://ntp.niehs.nih.gov/whatwestudy/assessments/noncancer/handbook (accessed on 8 November 2023).

- Hooijmans, C.R.; Rovers, M.M.; de Vries, R.B.; Leenaars, M.; Ritskes-Hoitinga, M.; Langendam, M.W. SYRCLE’s risk of bias tool for animal studies. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2014, 14, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bian, D.; Zhou, W.; Deng, J.; Liu, Y.; Li, W.; Chu, X.; Xiu, P.; Cai, H.; Kou, Y.; Jiang, B.; et al. Development of magnesium-based biodegradable metals with dietary trace element germanium as orthopaedic implant applications. Acta Biomater. 2017, 64, 421–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, M.; Qiao, Y.; Wang, Q.; Qin, H.; Zhang, X.; Liu, X. Dual ions implantation of zirconium and nitrogen into magnesium alloys for enhanced corrosion resistance, antimicrobial activity and biocompatibility. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2016, 148, 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mostofi, S.; Rad, E.B.; Wiltsche, H.; Fasching, U.; Szakacs, G.; Ramskogler, C.; Srinivasaiah, S.; Ueçal, M.; Willumeit, R.; Weinberg, A.-M.; et al. Effects of Corroded and Non-Corroded Biodegradable Mg and Mg Alloys on Viability, Morphology and Differentiation of MC3T3-E1 Cells Elicited by Direct Cell/Material Interaction. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0159879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Li, T.; Yang, C.; Wang, D.; He, G.; Cheng, M.; Wang, Q.; Zhang, X. Lithium-Incorporated Nanoporous Coating Formed by Micro Arc Oxidation (MAO) on Magnesium Alloy with Improved Corrosion Resistance, Angiogenesis and Osseointegration. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 2019, 15, 1172–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shangguan, Y.; Sun, L.; Wan, P.; Tan, L.; Wang, C.; Fan, X.; Qin, L.; Yang, K. Comparison study of different coatings on degradation performance and cell response of Mg-Sr alloy. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2016, 69, 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Kim, Y.K.; Kim, K.S.; Lee, K.B.; Lee, M.H. Enhancement of bone formation on LBL-coated Mg alloy depending on the different concentration of BMP-2. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2019, 173, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J.; Cheng, S.; Zhong, G.; Zhou, R.; Zhang, C.; He, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, F. Oxyhydroxide-Coated PEO-Treated Mg Alloy for Enhanced Corrosion Resistance and Bone Regeneration. J. Funct. Biomater. 2022, 13, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhang, D.; Peng, F.; Xie, J.; Zhang, X.; Qian, S.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.; Yu, B. Zinc-doped ferric oxyhydroxide nano-layer enhances the bactericidal activity and osseointegration of a magnesium alloy through augmenting the formation of neutrophil extracellular traps. Acta Biomater. 2022, 152, 575–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B.; Gao, P.; Zhang, H.; Guo, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Han, Y. Osteoimmunomodulation, osseointegration, and in vivo mechanical integrity of pure Mg coated with HA nanorod/pore-sealed MgO bilayer. Biomater. Sci. 2018, 6, 3202–3218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, W.; Zhao, H.; Ding, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Sun, B.; Shen, J.; Chen, S.; Zhang, B.; Yang, K.; Liu, M.; et al. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of MgF2 coated AZ31 magnesium alloy porous scaffolds for bone regeneration. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2017, 149, 330–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shen, S.; Cai, S.; Bao, X.; Xu, P.; Li, Y.; Jiang, S.; Xu, G. Biomimetic fluoridated hydroxyapatite coating with micron/nano-topography on magnesium alloy for orthopaedic application. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 339, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Li, L.; Yang, L.; Yao, L.; Wang, H.; Yu, X.; Shen, X.; Yao, L.; Wu, G. Osteoinduction Evaluation of Fluorinated Hydroxyapatite and Tantalum Composite Coatings on Magnesium Alloys. Front. Chem. 2021, 9, 727356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Chu, P.K.; Wang, L.; Pan, H.; Zheng, Y.; Wu, S.; Liu, X.; Cheung, K.M.C.; Wong, T.; et al. A functionalized TiO2/Mg2TiO4 nano-layer on biodegradable magnesium implant enables superior bone-implant integration and bacterial disinfection. Biomaterials 2019, 219, 119372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, S.; Zhang, D.; Li, M.; Liu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Qian, S.; Peng, F. Osteogenesis, angiogenesis and immune response of Mg-Al layered double hydroxide coating on pure Mg. Bioact. Mater. 2020, 6, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Lan, L.; Li, M.; Chu, X.; Zhong, H.; Yao, M.; Peng, F.; Zhang, Y. Pure Mg-Al Layered Double Hydroxide Film on Magnesium Alloys for Orthopedic Applications. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 24575–24584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Wang, W.; Zhang, X.; Nune, K.C.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, N.; Misra, R.D.K.; Yang, K.; Tan, L.; Yan, J. The effect of different coatings on bone response and degradation behavior of porous magnesium-strontium devices in segmental defect regeneration. Bioact. Mater. 2020, 6, 1765–1776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A.; Ikram, F.; Iqbal, F.; Fatima, H.; Mehmood, A.; Kolawole, M.; Chaudhry, A.; Siddiqi, S.; Rehman, I. Improving the in vitro Degradation, Mechanical and Biological Properties of AZ91-3Ca Mg Alloy via Hydrothermal Calcium Phosphate Coatings. Front. Mater. 2021, 8, 715104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Yang, G.; Zhou, W.; Hu, J.; Jia, W.; Lu, W. One-pot hydrothermal synthesis, in vitro biodegradation and biocompatibility of Sr-doped nanorod/nanowire hydroxyapatite coatings on ZK60 magnesium alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 799, 71–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, M.; Echeverry-Rendón, M.; Zhang, L.; Niu, J.; Zhang, J.; Pei, J.; Yuan, G. Effects of composition and hierarchical structures of calcium phosphate coating on the corrosion resistance and osteoblast compatibility of Mg alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2021, 120, 111734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perumal, G.; Ramasamy, B.; Nandkumar, A.M.; Doble, M. Nanostructure coated AZ31 magnesium cylindrical mesh cage for potential long bone segmental defect repair applications. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2018, 172, 690–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, S.; Duffy, B.; Curtin, J.; Jaiswal, S. Effect of High- and Low-Molecular-Weight Hyaluronic-Acid-Functionalized-AZ31 Mg and Ti Alloys on Proliferation and Differentiation of Osteoblast Cells. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 4, 3874–3884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.H.; Baek, S.M.; Lee, G.; Kim, S.J.; Kim, H.S.; Hahn, S.K. Biocompatible Magnesium Implant Double-Coated with Dexamethasone-Loaded Black Phosphorus and Poly(lactide-co-glycolide). ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2020, 3, 8879–8889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, F.; Cheng, S.; Zhang, R.; Li, M.; Zhou, J.; Wang, D.; Zhang, Y. Zn-contained mussel-inspired film on Mg alloy for inhibiting bacterial infection and promoting bone regeneration. Regen. Biomater. 2020, 8, rbaa044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, H.; Qin, Z.; Ouyang, Y.; Zheng, B.; Wei, H.; Ou, J.; Shen, C. Hydroxyapatite/chitosan-metformin composite coating enhances the biocompatibility and osteogenic activity of AZ31 magnesium alloy. J. Alloys Compd. 2022, 909, 164694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bo, L.; Run, H.; Jing, Y.; Lei, L.; Liang, Q.; Jianhong, Z.; Yufeng, Z.; Shuilin, W.; Yong, H. A self-healing coating containing curcumin for osteoimmunomodulation to ameliorate osseointegration. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 403, 126323. [Google Scholar]

- Negrescu, A.M.; Necula, M.G.; Gebaur, A.; Golgovici, F.; Nica, C.; Curti, F.; Iovu, H.; Costache, M.; Cimpean, A. In Vitro Macrophage Immunomodulation by Poly(ε-caprolactone) Based-Coated AZ31 Mg Alloy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheon, K.H.; Park, C.; Kang, M.H.; Kang, I.G.; Lee, M.K.; Lee, H.; Kim, H.E.; Jung, H.D.; Jang, T.S. Construction of tantalum/poly(ether imide) coatings on magnesium implants with both corrosion protection and osseointegration properties. Bioact. Mater. 2020, 6, 1189–1200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Liang, R.; Xu, K.; Zheng, S.; Mukherjee, S.; Liu, P.; Wang, C.; Chen, Y. Construction of multifunctional micro-patterned PALNMA/PDADMAC/PEGDA hydrogel and intelligently responsive antibacterial coating HA/BBR on Mg alloy surface for orthopedic application. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2022, 132, 112636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pandele, A.; Neacsu, P.; Cimpean, A.; Staras, A.; Miculescu, F.; Iordache, A.; Voicu, S.; Thakur, V.; Toader, O. Cellulose acetate membranes functionalized with resveratrol by covalent immobilization for improved osseointegration. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 438, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleer, N.; Julmi, S.; Gartzke, A.-K.; Augustin, J.; Feichtner, F.; Waselau, A.-C.; Klose, C.; Maier, H.; Wriggers, P.; Meyer-Lindenberg, A. Comparison of degradation behaviour and osseointegration of the two magnesium scaffolds, LAE442 and La2, in vivo. Materialia 2019, 8, 100436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindtner, R.A.; Castellani, C.; Tangl, S.; Zanoni, G.; Hausbrandt, P.; Tschegg, E.K.; Stanzl-Tschegg, S.E.; Weinberg, A.M. Comparative biomechanical and radiological characterization of osseointegration of a biodegradable magnesium alloy pin and a copolymeric control for osteosynthesis. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2013, 28, 232–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, J.; Lin, Y.; Bian, D.; Wang, M.; Lin, Z.; Chu, X.; Li, W.; Liu, Y.; Shen, Z.; Liu, Y.; et al. In vitro and in vivo studies of Mg-30Sc alloys with different phase structure for potential usage within bone. Acta Biomater. 2019, 98, 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kopp, A.; Fischer, H.; Soares, A.P.; Schmidt-Bleek, K.; Leber, C.; Kreiker, H.; Duda, G.; Kröger, N.; van Gaalen, K.; Hanken, H.; et al. Long-term in vivo observations show biocompatibility and performance of ZX00 magnesium screws surface-modified by plasma-electrolytic oxidation in Göttingen miniature pigs. Acta Biomater. 2023, 157, 720–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rendenbach, C.; Fischer, H.; Kopp, A.; Schmidt-Bleek, K.; Kreiker, H.; Stumpp, S.; Thiele, M.; Duda, G.; Hanken, H.; Beck-Broichsitter, B.; et al. Improved in vivo osseointegration and degradation behavior of PEO surface-modified WE43 magnesium plates and screws after 6 and 12 months. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2021, 129, 112380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]