Antioxidant, Xanthine Oxidase, α-Amylase and α-Glucosidase Inhibitory Activities of Bioactive Compounds from Rumex crispus L. Root

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

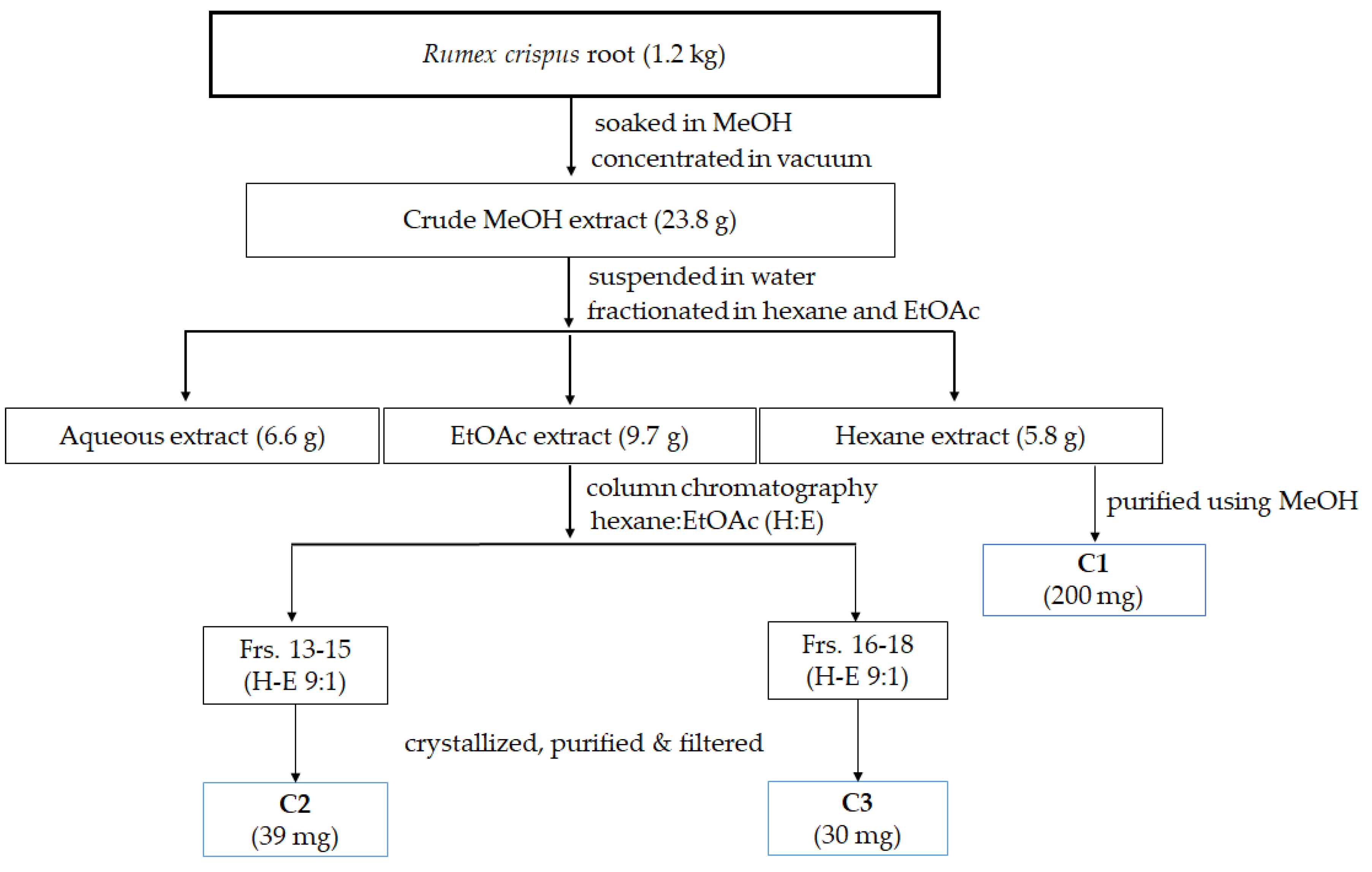

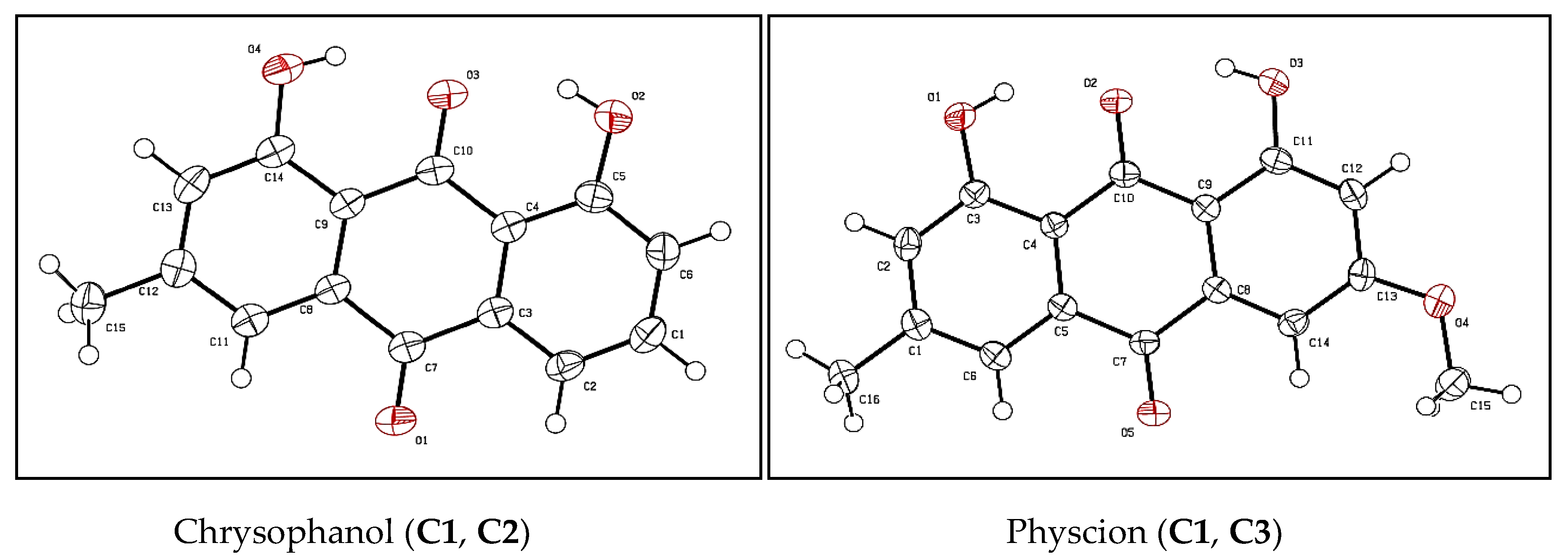

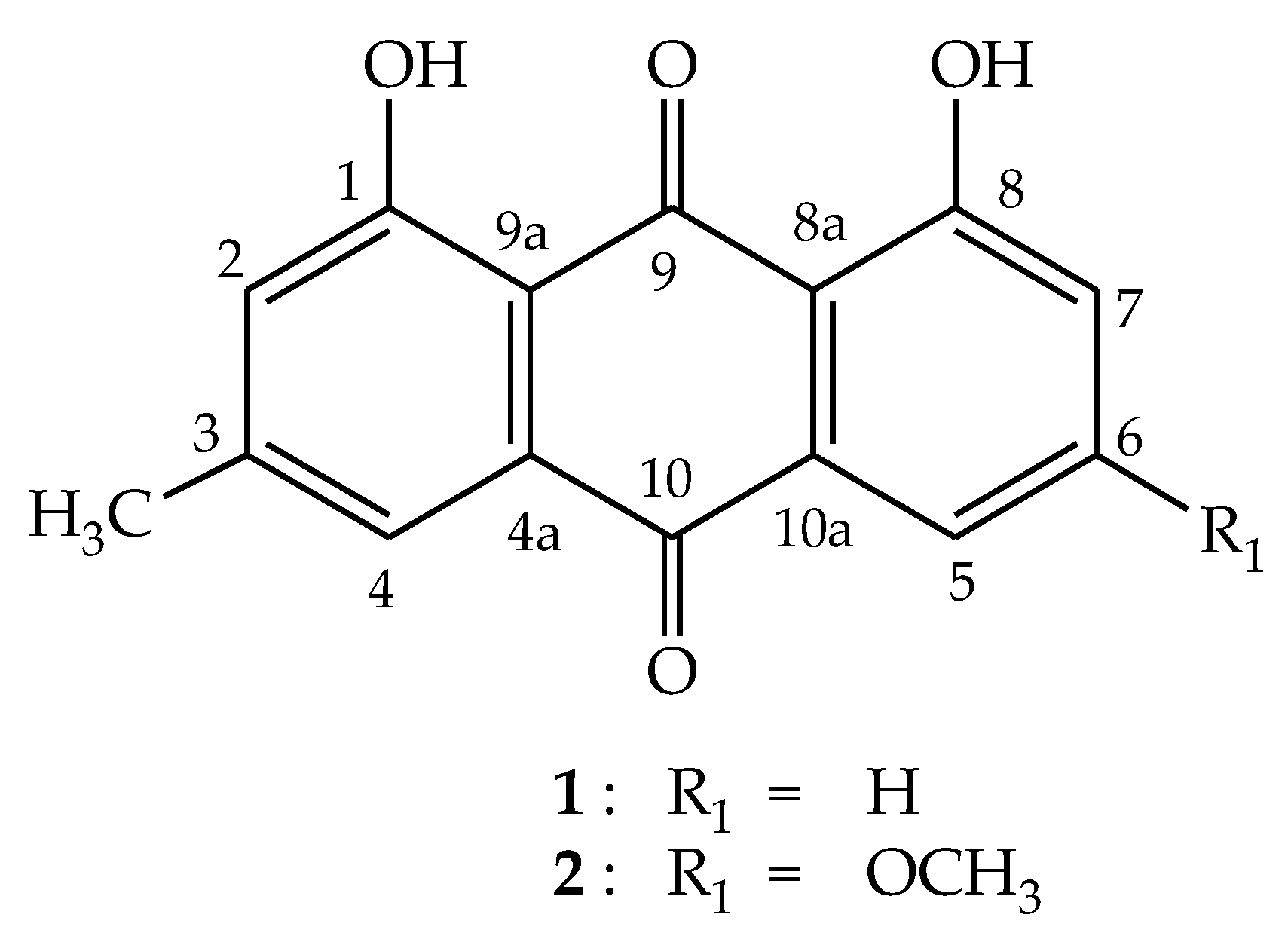

2.1. Structure Elucidation of Isolated Fractions

2.2. NMR Structural Elucidation

2.3. Quantitative Analysis of Fraxetin from Rumex Crispus Root

2.4. Antioxidant Activities of the Isolated Fractions

2.5. In Vitro Inhibition of Xanthine Oxidase (XOD), α-Amylase (AAI) and α-Glucosidase (AGI)

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Materials

4.2. Extraction of Rumex Crispus Root

4.3. Isolation of Pure Compounds

4.4. Antioxidants Activity

4.5. Identification and Quantification of Isolated Compounds

4.6. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Data of Chrysophanol and Physcion

4.7. Xanthine Oxidase Inhibition (XOD) Activity

4.8. α-Amylase Inhibition (AAI) Assay

4.9. α-Glucosidase Inhibition (AGI) Assay

4.10. Statistical Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cavers, P.B.; Harper, J.L. Rumex obtusifolius L. and R. crispus L. J. Ecol. 1964, 52, 737–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orbán-Gyapai, O.; Liktor-Busa, E.; Kúsz, N.; Stefkó, D.; Urbán, E.; Hohmann, J.; Vasas, A. Antibacterial Screening of Rumex Species Native to the Carpathian Basin and Bioactivity-Guided Isolation of Compounds from Rumex aquaticus. Fitoterapia. 2017, 118, 101–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Idris, O.A.; Wintola, O.A.; Afolayan, A.J. Comparison of the Proximate Composition, Vitamins (Ascorbic Acid, α-Tocopherol and Retinol), Anti-Nutrients (Phytate and Oxalate) and the GC-MS Analysis of the Essential Oil of the Root and Leaf of Rumex crispus L. Plants 2019, 8, 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mostafa, H.A.M.; Elbakry, A.A.; Eman, A.A. Evaluation of Antibacterial and Antioxidant Activities of Different Plant Parts of Rumex vesicarius L. (polygonaceae). Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2011, 3, 109–118. [Google Scholar]

- Kulczyński, B.; Sidor, A.; Gramza-Michałowska, A. Characteristics of Selected Antioxidative and Bioactive Compounds in Meat and Animal Origin Products. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, B.L.; Norhaizan, M.E.; Liew, W.P.; Sulaiman Rahman, H. Antioxidant and Oxidative Stress: A Mutual Interplay in Age-Related Diseases. Antioxidant and Oxidative Stress: A Mutual Interplay in Age-Related Diseases. Front Pharmacol. 2018, 9, 1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegiera, M.; Kosikowska, U.; Malm, A.; Smolarz, H. Antimicrobial Activity of the Extracts from Fruits of Rumex, L. Species. Open Life Sci. 2011, 6, 1036–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feduraev, P.; Chupakhina, G.; Maslennikov, P.; Tacenko, N.; Skrypnik, L. Variation in Phenolic Compounds Content and Antioxidant Activity of Different Plant Organs from Rumex crispus L. and Rumex obtusifolius L. at Different Growth Stages. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, N.; Saxena, S. Potential Xanthine Oxidase Inhibitory Activity of Endophytic Lasiodiplodia pseudotheobromae. App. Biochem. Biotech. 2014, 173, 1360–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, M.T.T.; Awale, S.; Tezuka, Y.; Tran, Q.L.; Watanabe, H.; Kadota, S. Xanthine Oxidase Inhibitory Activity of Vietnamese Medicinal Plants. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2004, 27, 1414–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lien, Y.H.; Logan, J.L. Cross-reactions between Allopurinol and Febuxostat. Am. J. Med. 2017, 130, e67–e68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chohan, S. Safety and Efficacy of Febuxostat Treatment in Subjects with Gout and Severe Allopurinol Adverse Reactions. J. Rheumatol. 2011, 38, 1957–1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cos, P.; Ying, L.; Calomme, M.; Hu, J.P.; Cimanga, K.; Van, P.B.; Pieters, L.; Vlietinck, A.J.; Berghe, D.V. Structure−Activity Relationship and Classification of Flavonoids as Inhibitors of Xanthine Oxidase and Superoxide Scavengers. J. Nat. Prod. 1998, 61, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pacher, P.; Nivorozhkin, A.; Szabó, C. Therapeutic Effects of Xanthine Oxidase Inhibitors: Renaissance Half a Century After the Discovery of Allopurinol. Pharmacol. Rev. 2006, 58, 87–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed Isa, S.S.P.; Ablat, A.; Mohamad, J. The Antioxidant and Xanthine Oxidase Inhibitory Activity of Plumeria rubra Flowers. Molecules 2018, 23, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotelle, N.; Bernier, J.L.; Henichart, J.P.; Catteau, J.P.; Gaydou, E.; Wallet, J.C. Scavenger and Antioxidant Properties of Ten Synthetic Flavones. Free Radical Bio. Med. 1992, 13, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Diabetes Federation. IDF Diabetes Atlas, 8th ed. Available online: http://diabetesatlas.org/key-messages.html (accessed on 1 August 2018).

- Leahy, J.L. Pathogenesis of Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Arch. Med. Res. 2005, 36, 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abesundara, K.J.M.; Matsui, T.; Matsumoto, K. α-Glucosidase Inhibitory Activity of some Sri Lanka Plant Extracts, one of which, Cassia auriculata, Exerts a Strong Antihyperglycemic Effect in Rats Comparable to the Therapeutic Drug Acarbose. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004, 52, 2541–2545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, A.; Wilson, R.; Bradley, H.; Thomson, J.A.; Small, M. Free Radical Activity is type 2 Diabetes. Diabetic Med. 1990, 7, 27–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliwell, B.; Gutteridge, J.M.C. Free radicals in Biology and Medicine, 4th ed.; Clarendon: Oxford, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Logani, M.K.; Davis, R.E. Lipid Peroxidation in Biologic Effects and Antioxidants: A Review. Lipids 1979, 15, 485–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhu, C.G.; Devi, D.B. Protective Antioxidant Effect of Vitamins C and E in Streptozotocin Induced Diabetic Rats. Ind. J. Exp. Biol. 2000, 38, 101–104. [Google Scholar]

- Nagarajan, S.; Jain, H.C.; Aulakh, G.S. Indigenous Plants Used in the Control of Diabetes; Publication and Information Directorate CSIR: New Delhi, India, 1987; p. 586. [Google Scholar]

- Jain, S.R.; Sharma, S.N. Hypoglycemic Drugs of Indian Indigenous Origin. Planta Medica 1967, 15, 439–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anjali, P.; Manoj, K.M. Same Comments on Diabetes and Herbal Therapy. Ancient Sci. Life 1995, 15, 27–29. [Google Scholar]

- Idris, O.A.; Wintola, O.A.; Afolayan, A.J. Phytochemical and Antioxidant Activities of Rumex crispus L. in Treatment of Gastrointestinal Helminths in Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Bio. 2017, 12, 1071–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maksimović, Z.; Kovacević, N.; Lakusić, B.; Cebović, T. Antioxidant Activity of Yellow Dock (Rumex crispus L., Polygonaceae) Fruit Extract. Phytother Res. 2011, 25, 101–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Ou, B.; Prior, R.L. The Chemistry Behind Antioxidant Capacity Assays. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 1841–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elzaawely, A.A.; Xuan, T.D.; Tawasta, S. Antioxidant and Antibacterial Activities of Rumex japonicus Houtt. Aerial Parts. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2005, 28, 2225–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriana, Y.; Xuan, T.D.; Quy, T.N.; Minh, T.N.; Van, T.M.; Viet, T.D. Antihyperuricemia, Antioxidant, and Antibacterial Activities of Tridax procumbens L. Foods 2019, 8, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagao, A.; Seki, M.; Kobayashi, H. Inhibition of Xanthine Oxidase by Flavonoids. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 1999, 63, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shieh, D.E.; Liu, L.T.; Lin, C.C. Antioxidant and Free Radical Scavenging Effects of Baicalein, Baicalin and Wogonin. Anticancer Res. 2000, 20, 2861–2865. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, P.; Gupta, R. Alpha-amylase Inhibition can Treat Diabetes Mellitus. RRJMHS. 2016, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Z.; Zhang, W.; Feng, F.; Zhang, Y.; Kang, W. α-Glucosidase Inhibitors Isolated from Medicinal Plants. Food Sci. Hum. Wellness. 2014, 3, 136–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, Z.H.; Alam, M.K.; Akhtaruzzaman, M. Nutritional Composition, Total Phenolic Content, Antioxidant and α-Amylase Inhibitory Activities of Different Fractions of Selected Wild Edible Plants. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Minh, T.N.; Xuan, T.D.; Ahmad, A.; Elzaawely, A.A.; Teschke, R.; Van, T.M. Efficacy from Different Extractions for Chemical Profile and Biological Activities of Rice Husk. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh, T.N.; Tuyen, P.T.; Khang, D.T.; Quan, N.V.; Ha, P.T.T.; Quan, N.T.; Yusuf, A.; Fan, X.; Van, T.M.; Khanh, T.D.; et al. Potential Use of Plant Wastes of Moth Orchid (Phalaenopsis Sogo Yukidian ‘V3′) as an Antioxidant Source. Foods 2017, 6, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh, T.N.; Khang, D.T.; Tuyen, P.T.; Minh, L.T.; Anh, L.H.; Quan, N.V.; Ha, P.T.T.; Quan, N.T.; Toan, N.P.; Elzaawely, A.A.; et al. Phenolic Compounds and Antioxidant Activity of Phalaenopsis Orchid Hybrids. Antioxidants 2016, 5, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van, T.M.; Xuan, T.D.; Minh, T.N.; Quan, N.V. Isolation and Purification of Potent Growth Inhibitors from Piper methysticum Root. Molecules 2018, 23, 1907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh, T.N.; Xuan, T.D.; Tran, H.-D.; Van, T.M.; Andriana, Y.; Khanh, T.D.; Quan, N.V.; Ahmad, A. Isolation and Purification of Bioactive Compounds from the Stem Bark of Jatropha podagrica. Molecules 2019, 24, 889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viet, T.D.; Xuan, T.D.; Van, T.M.; Andriana, Y.; Rayee, R.; Tran, H.-D. Comprehensive Fractionation of Antioxidants and GC-MS and ESI-MS Fingerprints of Celastrus hindsii Leaves. Medicines 2019, 6, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh, T.N.; Xuan, T.D.; Van, T.M.; Andriana, Y.; Viet, T.D.; Khanh, T.D.; Tran, H.-D. Phytochemical Analysis and Potential Biological Activities of Essential Oil from Rice Leaf. Molecules 2019, 24, 546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, C.; Liu, X.; Jiang, Z.; Geng, S.; Ma, H.; Liu, B. Interaction Mechanism of Flavonoids and α-Glucosidase: Experimental and Molecular Modelling Studies. Foods 2019, 8, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Sample Availability: Samples of the compounds are available from the authors. |

| Fractions | Retention Time | Peak Area (%) | Compounds | Chemical Formula | Molecular Weight | Similarity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | 20.70 | 73.39 | Chrysophanol | C15H10O4 | 254 | 90.8 |

| 22.98 | 24.82 | Physcion | C16H12O5 | 284 | 91.8 | |

| C2 | 20.71 | 98.10 | Chrysophanol | C15H10O4 | 254 | 98.1 |

| C3 | 22.99 | 97.79 | Physcion | C16H12O5 | 284 | 97.8 |

| Position | 1 | 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| δC* | δC | δC** | δC | |

| 1 | 161.1 | 162.7 | 162.5 | 162.5 |

| 2 | 124.2 | 124.4 | 124.5 | 124.5 |

| 3 | 149.0 | 149.3 | 148.4 | 148.4 |

| 4 | 120.4 | 121.4 | 121.3 | 121.3 |

| 5 | 119.2 | 119.9 | 108.2 | 108.2 |

| 6 | 137.2 | 136.9 | 166.5 | 166.5 |

| 7 | 123.9 | 124.6 | 106.8 | 106.8 |

| 8 | 161.4 | 162.4 | 165.2 | 165.2 |

| 9 | 191.4 | 192.6 | 190.8 | 190.7 |

| 10 | 181.3 | 182.0 | 181.5 | 181.9 |

| 4a | 132.8 | 133.3 | 133.2 | 133.2 |

| 8a | 115.7 | 115.9 | 110.3 | 110.3 |

| 9a | 113.6 | 113.8 | 113.7 | 113.7 |

| 10a | 133.2 | 133.7 | 135.3 | 135.2 |

| CH3 | 21.6 | 22.2 | 22.1 | 22.1 |

| OCH3 | 56.0 | 56.0 | ||

| Fractions | Retention Time | Compounds | Concentration |

|---|---|---|---|

| (µg/g DW) | |||

| C2 | 20.70 ± 0.02 | Chrysophanol | 32.50 ± 0.11 |

| C3 | 22.99 ± 0.05 | Physcion | 25.04 ± 0.08 |

| Fractions | IC50 (µg/mL) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| DPPH | ABTS | FRAP | |

| C1 | 35.0 ± 1.6a | 194.7 ± 2.0a | 1366.5 ± 8.4a |

| C2 | 10.0 ± 0.3c | 34.3 ± 0.7c | 312.6 ± 6.3c |

| (39.4 µM) | (135.0 µM) | (1230.7 µM) | |

| C3 | 12.0 ± 0.2c | 44.8 ± 0.8b | 408.6 ± 6.8b |

| (42.3 µM) | (157.7 µM) | (1438.7 µM) | |

| BHT* | 19.2 ± 0.3b | 46.9 ± 0.9b | 422.1 ± 1.1b |

| (87.1 µM) | (212.8 µM) | (1915.8 µM) | |

| Fractions | IC50 (µg/mL) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| XOD | AAI | AGI | |

| C1 | 88.8 ± 0.9a | 199.1 ± 1.4a | 91.6 ± 1.4b |

| C2 | 36.4 ± 0.6c | 117.3 ± 1.0b | 20.1 ± 0.6c |

| (143.3 µM) | (461.8 µM) | (79.1 µM) | |

| C3 | 45.0 ± 0.7b | 113.3 ± 1.3c | 18.9 ± 0.4c |

| (158.5 µM) | (398.9 µM) | (66.5 µM) | |

| Allopurinol* | 20.5 ± 0.5d | - | - |

| (150.6 µM) | |||

| Acarbose* | - | 90.9 ± 0.8d | 143.8 ± 2.6a |

| (140.8 µM) | (222.7 µM) | ||

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Minh, T.N.; Van, T.M.; Andriana, Y.; Vinh, L.T.; Hau, D.V.; Duyen, D.H.; Guzman-Gelani, C.d. Antioxidant, Xanthine Oxidase, α-Amylase and α-Glucosidase Inhibitory Activities of Bioactive Compounds from Rumex crispus L. Root. Molecules 2019, 24, 3899. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24213899

Minh TN, Van TM, Andriana Y, Vinh LT, Hau DV, Duyen DH, Guzman-Gelani Cd. Antioxidant, Xanthine Oxidase, α-Amylase and α-Glucosidase Inhibitory Activities of Bioactive Compounds from Rumex crispus L. Root. Molecules. 2019; 24(21):3899. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24213899

Chicago/Turabian StyleMinh, Truong Ngoc, Truong Mai Van, Yusuf Andriana, Le The Vinh, Dang Viet Hau, Dang Hong Duyen, and Chona de Guzman-Gelani. 2019. "Antioxidant, Xanthine Oxidase, α-Amylase and α-Glucosidase Inhibitory Activities of Bioactive Compounds from Rumex crispus L. Root" Molecules 24, no. 21: 3899. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24213899

APA StyleMinh, T. N., Van, T. M., Andriana, Y., Vinh, L. T., Hau, D. V., Duyen, D. H., & Guzman-Gelani, C. d. (2019). Antioxidant, Xanthine Oxidase, α-Amylase and α-Glucosidase Inhibitory Activities of Bioactive Compounds from Rumex crispus L. Root. Molecules, 24(21), 3899. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24213899