Emotional Intelligence, Perceived Stress, and Burnout in Undergraduate Medical Students: A Cross-Sectional Correlational Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Setting and Participants

2.2. Study Design and Data Collection

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.4. Ethical Approval and Consent

3. Results

3.1. Participants

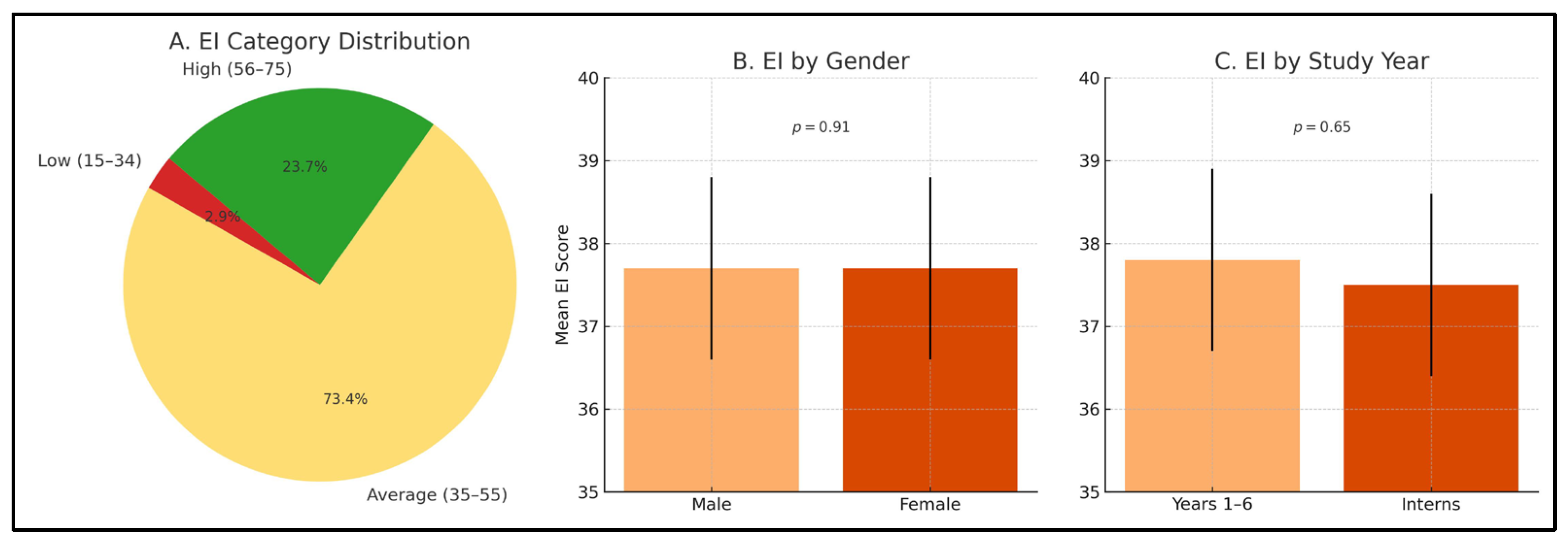

3.2. Emotional Intelligence

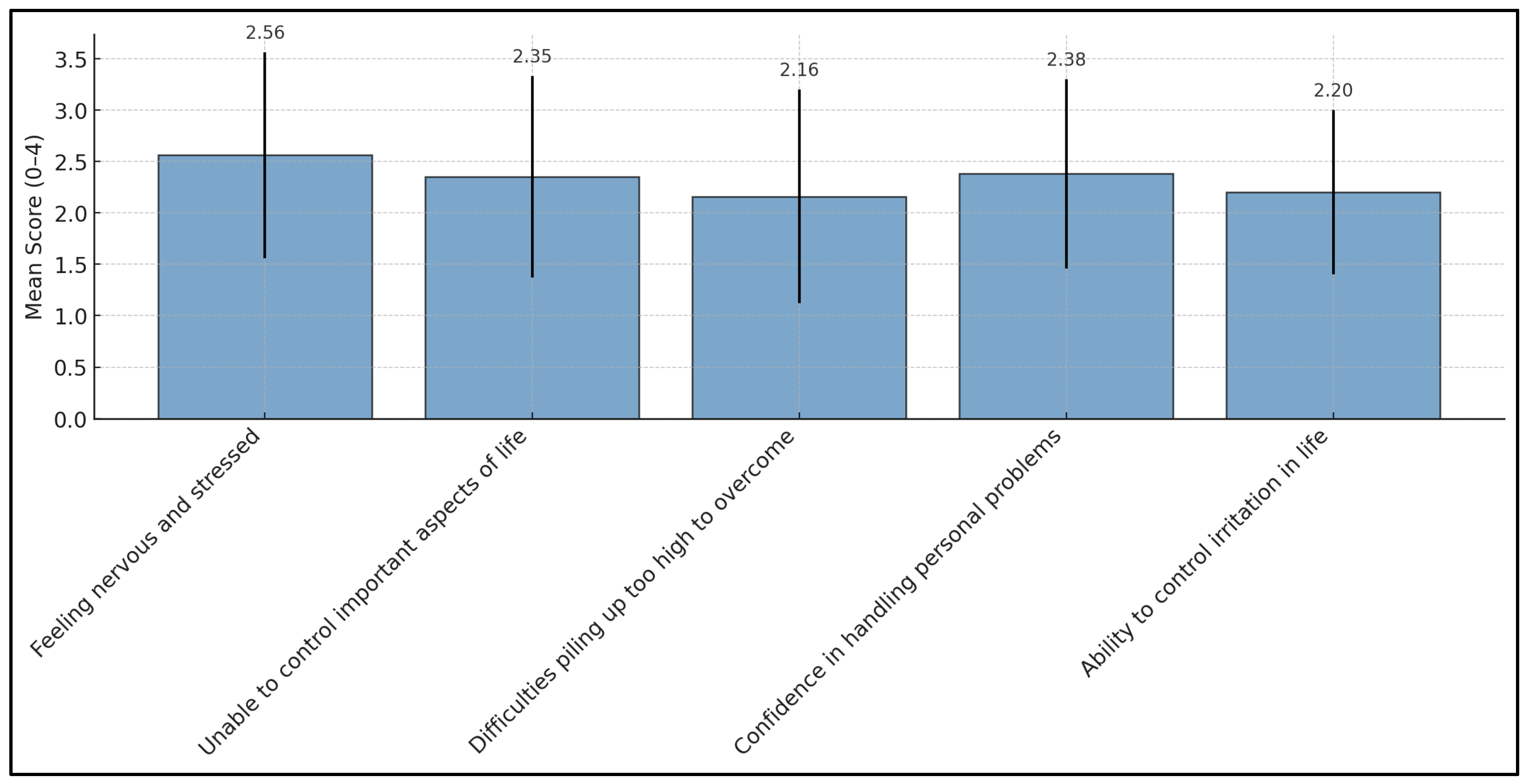

3.3. Perceived Stress

3.4. Burnout

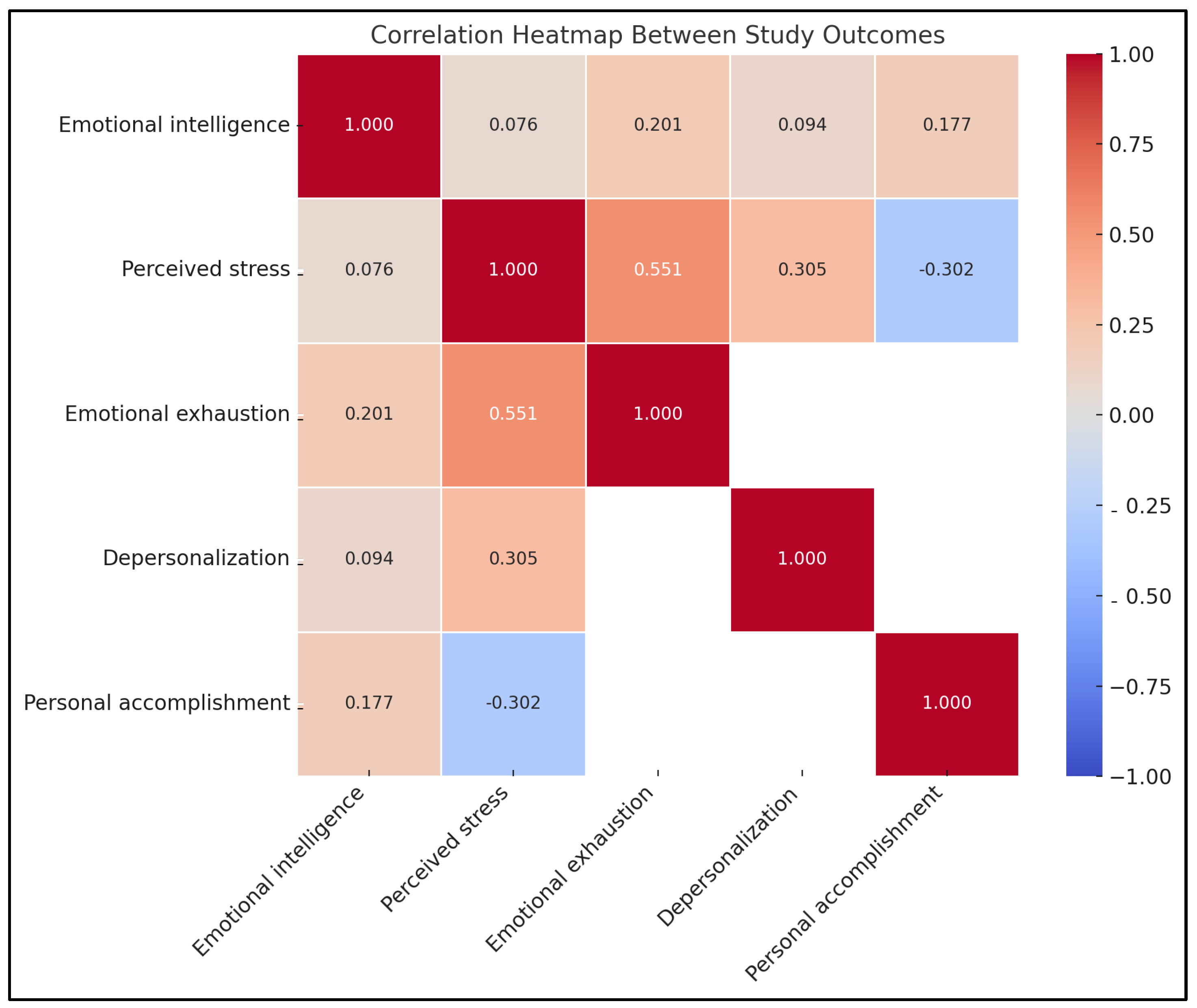

3.5. Correlation Between Emotional Intelligence, Perceived Stress, and Burnout

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| EI | Emotional Intelligence |

| NARS | National Academic Reference Standards |

| QPD | Quality for Personal Development |

| MENA | Middle East and North Africa |

| CME | Continuous Medical Education |

| PSS | Perceived Stress Scale |

| MBI | Maslach Burnout Inventory |

Appendix A

| EI Domain | Mean | Standard Deviation (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Self-awareness | 2.89 | 0.81 |

| Self-regulation | 2.47 | 0.89 |

| Motivation | 2.50 | 0.99 |

| Empathy | 2.97 | 0.84 |

| Social skills | 2.68 | 0.87 |

Appendix B

| PSS Item | Mean | Standard Deviation (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Feeling nervous and stressed | 2.66 | 1.04 |

| Unable to control important aspects of life | 2.35 | 1.02 |

| Difficulties piling up too high to overcome | 2.16 | 1.06 |

| Confidence in handling personal problems | 2.38 | 0.90 |

| Ability to control irritation in life | 2.20 | 0.78 |

References

- Chye, S.M.; Kok, Y.Y.; Chen, Y.S.; Er, H.M. Building resilience among undergraduate health professions students: Identifying influencing factors. BMC Med. Educ. 2024, 24, 1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daud, N.; Rahim, A.F.A.; Pa, M.N.M.; Ahmad, A.; Yusof, N.A.; Hassan, N.M.; Idris, N.A. Emotional Intelligence Among Medical Students and Its Relationship with Burnout. Educ. Med. J. 2022, 14, 49–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahid, M.H.; Sethi, M.R.; Shaheen, N.; Javed, K.; Qazi, I.A.; Osama, M.; Ilah, A.; Firdos, T. Effect of academic stress, educational environment on academic performance & quality of life of medical & dental students; gauging the understanding of health care professionals on factors affecting stress: A mixed method study. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0290839. [Google Scholar]

- Almutairi, H.; Alsubaiei, A.; Abduljawad, S.; Alshatti, A.; Fekih-Romdhane, F.; Husni, M.; Jahrami, H. Prevalence of burnout in medical students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Social Psychiatry 2022, 68, 1157–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avila-Carrasco, L.; Díaz-Avila, D.L.; Reyes-López, A.; Monarrez-Espino, J.; Garza-Veloz, I.; Velasco-Elizondo, P.; Vázquez-Reyes, S.; Mauricio-González, A.; Solís-Galván, J.A.; Martinez-Fierro, M.L. Anxiety, depression, and academic stress among medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Front. Psychol. 2023, 13, 1066673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshehri, A.; Alshehri, B.; Alghadir, O.; Basamh, A.; Alzeer, M.; Alshehri, M.; Nasr, S. The prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms among first-year and fifth-year medical students during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. BMC Med. Educ. 2023, 23, 411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voltmer, E.; Köslich-Strumann, S.; Voltmer, J.-B.; Kötter, T. Stress and behavior patterns throughout medical education—A six year longitudinal study. BMC Med. Educ. 2021, 21, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bru-Luna, L.M.; Martí-Vilar, M.; Merino-Soto, C.; Cervera-Santiago, J.L. Emotional intelligence measures: A systematic review. Healthcare 2021, 9, 1696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravikumar, R.; Rajoura, O.P.; Sharma, R.; Bhatia, M.S.; Bhatia Sr, M.S. A study of emotional intelligence among postgraduate medical students in Delhi. Cureus 2017, 9, e989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sfeir, E.; El Othman, R.; Barakat, M.; Hallit, S.; Obeid, S. Personality traits and mental health among Lebanese medical students: The mediating role of emotional intelligence. Healthcare 2022, 10, 2516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jamil, S.; Jamil, S.; Ullah, M.S. Correlation between emotional intelligence and academic stress in undergraduate medical students. Health Prof. Educ. J. 2020, 3, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeneessier, A.S.; Azer, S.A. Exploring the relationship between burnout and emotional intelligence among academics and clinicians at King Saud University. BMC Med. Educ. 2023, 23, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tur-Porcar, A.M.; Cuartero-Monteagudo, N.; Fernández-Garrido, J. Learning environments in health and medical studies: The mediating role of emotional intelligence. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Sang, B.; Ding, C. How Emotional Intelligence Influences Students’ Life Satisfaction During University Lockdown: The Chain Mediating Effect of Interpersonal Competence and Anxiety. Behav. Sci. 2024, 14, 1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cañero Pérez, M.; Mónaco Gerónimo, E.; Montoya Castilla, I. Emotional intelligence and empathy as predictors of subjective well-being in university students. Eur. J. Investig. Health Psychol. Educ. 2019, 9, 19–29. [Google Scholar]

- Khorasani, E.C.; Ardameh, M.; Sany, S.B.T.; Tehrani, H.; Ghavami, V.; Gholian-Aval, M. The influence of emotional intelligence on academic stress among medical students in Neyshabur, Iran. BMC Psychiatry 2023, 23, 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, A.A.; Bahnassy, A.A.; Al-Hamdan, N.A.; Almudhaibery, F.S.; Alyahya, A.Z. Perceived stress and associated factors among medical students. J. Fam. Community Med. 2016, 23, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinen, I.; Bullinger, M.; Kocalevent, R.-D. Perceived stress in first year medical students-associations with personal resources and emotional distress. BMC Med. Educ. 2017, 17, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atlam, S.A. Burnout syndrome: Determinants and predictors among medical students of Tanta University, Egypt. Egypt. J. Community Med. 2018, 36, 61–73. [Google Scholar]

- Mohasseb, M.M.; Said, H.S. Stress and Burnout among Egyptian Undergraduate Medical Students. Egypt. J. Community Med. 2021, 39, 93–103. [Google Scholar]

- Chong, L.Z.; Foo, L.K.; Chua, S.-L. Student Burnout: A Review on Factors Contributing to Burnout Across Different Student Populations. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Altannir, Y.; Alnajjar, W.; Ahmad, S.O.; Altannir, M.; Yousuf, F.; Obeidat, A.; Al-Tannir, M. Assessment of burnout in medical undergraduate students in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. BMC Med. Educ. 2019, 19, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almalki, S.A.; Almojali, A.I.; Alothman, A.S.; Masuadi, E.M.; Alaqeel, M.K. Burnout and its association with extracurricular activities among medical students in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Med. Educ. 2017, 8, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El-Gabry, D.A.; Okasha, T.; Shaker, N.; Elserafy, D.; Yehia, M.; Aziz, K.A.; Bhugra, D.; Molodynski, A.; Elkhatib, H. Mental health and wellbeing among Egyptian medical students: A cross-sectional study. Middle East Curr. Psychiatry 2022, 29, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumann, M.; Baraka, A. Using REFLECT rubric for assessing the reflective use of e-portfolios, a qualitative pilot study at Alexandria Faculty of Medicine. J. Health Prof. Educ. Innov. 2024, 1, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahin, M.A. Emotional intelligence and perceived stress among students in Saudi health colleges: A cross-sectional correlational study. J. Taibah Univ. Med. Sci. 2020, 15, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S.; Kamarck, T.; Mermelstein, R. Perceived stress scale. In Measuring Stress: A Guide for Health and Social Scientists; Oxford University Press Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1994; Volume 10, pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Maslach, C.; Jackson, S.E.; Leiter, M.P. Maslach Burnout Inventory; Scarecrow Education: Lanham, MD, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team, R. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2015; pp. 171–203. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelmohsen, S.R.; Khired, Z.A.; El-Ma’doul, A.S.; Barakat, A.M.; Kasemy, Z.A. Emotional Intelligence and Academic Performance Among Egyptian and Saudi Arabian Undergraduate Medical Students: A Cross Sectional Study. Res. Sq. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, H.E.; Bady, Z.; Abdelhamid, Z.G.; Elawfi, B.; AboElfarh, H.E.; Elboraay, T.; Abdel-Salam, D.M. Factors influencing stress and resilience among Egyptian medical students: A multi-centric cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 2024, 24, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cairns, P.; Isham, A.E.; Zachariae, R. The association between empathy and burnout in medical students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. Educ. 2024, 24, 640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleh, E.G.; Darraj, M.A.; Yassin, A.K.; Elsayed, M.G. Perceived Stress among Jazan Medical Students: A Preliminary Study for Effective Intervention Program. Egypt. J. Hosp. Med. 2024, 95, 2092–2099. [Google Scholar]

- Ebrahim, O.S.; Sayed, H.A.; Rabei, S.; Hegazy, N. Perceived stress and anxiety among medical students at Helwan University: A cross-sectional study. J. Public Health Res. 2024, 13, 22799036241227891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tokumasu, K.; Nishimura, Y.; Sakamoto, Y.; Obika, M.; Kataoka, H.; Otsuka, F. Differences in Stress Perception of Medical Students Depending on In-Person Communication and Online Communication during the COVID−19 Pandemic: A Japanese Cross-Sectional Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sehlo, M.G.; Al-Zaben, F.N.; Khalifa, D.A.; Agabawi, A.K.; Akel, M.S.; Nemri, I.A.; Abd Al-Wassie, L.K. Stress among medical students in a college of medicine in Saudi Arabia: Sex differences. Middle East Curr. Psychiatry 2018, 25, 150–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niemi, P.; Vainiomäki, P. Medical students’ distress–quality, continuity and gender differences during a six-year medical programme. Med. Teach. 2006, 28, 136–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Worly, B.; Verbeck, N.; Walker, C.; Clinchot, D.M. Burnout, perceived stress, and empathic concern: Differences in female and male Millennial medical students. Psychol. Health Med. 2019, 24, 429–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Sunni, A.; Latif, R. Perceived stress among medical students in preclinical years: A Saudi Arabian perspective. Saudi J. Health Sci. 2014, 3, 155–159. [Google Scholar]

- Shriram, V.; Bhimani, N.; Aundhakar, N.; Zingade, U.; Kowale, A. Study of perceived stress among I MBBS medical students. J. Educ. Technol. Health Sci. 2015, 2, 8–12. [Google Scholar]

- Ghouri, M.; Noor, A.; Majeed, Z.; Abida, T.; Mehmood, Z.; Rajput, R. Comparison of perception of academic stress among medical and non-medical students. Rehabil. J. 2024, 8, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, A.; Mehdi, A. A Study on Perceived Stress among Medical Students from a Private Medical College in North India. Indian J. Psychiatry 2021, 64 (Suppl. S3), S582–S583. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, S.; Prakash, J.; Das, R.; Srivastava, K. A cross-sectional assessment of stress, coping, and burnout in the final-year medical undergraduate students. Ind. Psychiatry J. 2016, 25, 179–183. [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha, D.B.; Katuwal, N.; Tamang, A.; Paudel, A.; Gautam, A.; Sharma, M.; Bhusal, U.; Budhathoki, P. Burnout among medical students of a medical college in Kathmandu; A cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0253808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahan, S.S.; Nerali, J.T.; Parsa, A.D.; Kabir, R. Exploring the association between emotional intelligence and academic performance and stress factors among dental students: A scoping review. Dent. J. 2022, 10, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goldman, C.M.; Chuning, A.E.; Lane, R.D.; Smith, R.; Weihs, K.L. Emotional awareness amplifies affective sensitivity to social support for women with breast cancer. J. Health Psychol. 2024. ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lionetti, F.; Pluess, M. The role of environmental sensitivity in the experience and processing of emotions: Implications for well-being. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2024, 379, 20230244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-H.; Joo, M.-H. The moderating effects of self-care on the relationships between perceived stress, job burnout and retention intention in clinical nurses. Healthcare 2023, 11, 1870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilic, I.; Zivanovic Macuzic, I.; Ilic, M. High risk of burnout syndrome and associated factors in medical students: A cross-sectional analytical study. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0304515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiss, H.; Pikó, B.F. Risk and protective factors of student burnout among medical students: A multivariate analysis. BMC Med. Educ. 2025, 25, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.R.; Iwanaga, K.; Chan, F.; Hu, W.; Zhou, K.; Chen, X.; Chan, C.C.; Tansey, T.N. The Constructs of the Lazarus and Folkman’s Stress-Appraisal-Coping Theory as Predictors of Subjective Well-Being in College Students During the Ongoing COVID-19 Pandemic. J. Asia Pac. Couns. 2023, 13, 41–65. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Category | N (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 131 (49.62%) |

| Male | 133 (50.38%) | |

| Nationality | Egyptian | 223 (84.47%) |

| Non-Egyptian | 41 (15.53%) | |

| Residence | In Alexandria | 180 (68.18%) |

| Outside Alexandria (commute) | 82 (31.06%) | |

| Not reported | 2 (0.76%) | |

| Study Year | Academic years 1–6 | 172 (65.15%) |

| Internship | 92 (34.85%) | |

| Last Academic Grade | Excellent (85–100%) | 93 (35.23%) |

| Very good (75–85%) | 108 (40.91%) | |

| Good (65–75%) | 52 (19.70%) | |

| Pass (60–65%) | 10 (3.79%) | |

| Fail (<60%) | 1 (0.38%) |

| Burnout Category | Male | Female | Years 1–6 | Interns | p-Value (Gender) | p-Value (Year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotional Exhaustion | ||||||

| High | 45.9% | 48.1% | 51.7% | 38.0% | 0.738 | 0.011 * |

| Moderate | 36.1% | 37.4% | 36.6% | 37.0% | ||

| Low | 18.0% | 14.5% | 11.6% | 25.0% | ||

| Depersonalization | ||||||

| High | 54.9% | 43.5% | 53.5% | 41.3% | 0.057 | 0.029 * |

| Moderate | 30.8% | 31.3% | 31.4% | 30.4% | ||

| Low | 14.3% | 25.2% | 15.1% | 28.3% | ||

| Personal Accomplishment | ||||||

| Low | 77.4% | 88.5% | 82.6% | 83.7% | 0.054 | 0.537 |

| Moderate | 18.8% | 9.2% | 14.0% | 15.1% | ||

| High | 3.8% | 2.3% | 3.0% | 2.3% | ||

| Burnout (Overall) | ||||||

| Burnout | 29.3% | 31.3% | 30.8% | 29.3% | 0.83 | 0.915 |

| No Burnout | 70.7% | 68.7% | 69.2% | 70.7% |

| Predictor | β (Beta Coefficient) | 95% Confidence Interval | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (Male vs. Female) | −1.06 | [−2.21, 0.08] | 0.068 |

| Academic Year (Intern vs. Years 1–6) | −0.07 | [−1.37, 1.22] | 0.910 |

| Academic Grade (Very Good vs. Excellent) | 0.34 | [−0.96, 1.63] | 0.609 |

| Academic Grade (Good vs. Excellent) | 1.04 | [−0.51, 2.60] | 0.188 |

| Academic Grade (Pass vs. Excellent) | −0.36 | [−3.26, 2.53] | 0.805 |

| Academic Grade (Fail vs. Excellent) | 2.34 | [−9.82, 14.49] | 0.705 |

| Academic Year (Sixth Year (new) vs. First Year) | 2.04 | [−0.27, 4.35] | 0.084 |

| Academic Year (Sixth Year (old) vs. First Year) | 1.69 | [−0.22, 3.60] | 0.083 |

| Academic Year (Second Year vs. First Year) | 3.16 | [−1.21, 7.52] | 0.155 |

| Academic Year (Fourth Year vs. First Year) | 1.64 | [−2.78, 6.05] | 0.467 |

| Academic Year (Third Year vs. First Year) | −2.96 | [−11.60, 5.68] | 0.501 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Academic Society for International Medical Education. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schumann, M.; Ghorab, H.M.; Baraka, A. Emotional Intelligence, Perceived Stress, and Burnout in Undergraduate Medical Students: A Cross-Sectional Correlational Study. Int. Med. Educ. 2025, 4, 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/ime4020023

Schumann M, Ghorab HM, Baraka A. Emotional Intelligence, Perceived Stress, and Burnout in Undergraduate Medical Students: A Cross-Sectional Correlational Study. International Medical Education. 2025; 4(2):23. https://doi.org/10.3390/ime4020023

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchumann, Marwa, Hossam M. Ghorab, and Azza Baraka. 2025. "Emotional Intelligence, Perceived Stress, and Burnout in Undergraduate Medical Students: A Cross-Sectional Correlational Study" International Medical Education 4, no. 2: 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/ime4020023

APA StyleSchumann, M., Ghorab, H. M., & Baraka, A. (2025). Emotional Intelligence, Perceived Stress, and Burnout in Undergraduate Medical Students: A Cross-Sectional Correlational Study. International Medical Education, 4(2), 23. https://doi.org/10.3390/ime4020023