Resilience of Post-Quantum Cryptography in Lightweight IoT Protocols: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

Research Questions

- What post-quantum cryptographic schemes have been evaluated for IoT-to-cloud security?

- What performance trade-offs (latency, bandwidth, memory) are reported when integrating PQC into IoT protocols?

- What open challenges and research gaps remain for deploying PQC in real-world IoT-cloud systems?

- How do PQC-secured lightweight protocols perform under realistic network conditions?

2. Background and Related Work

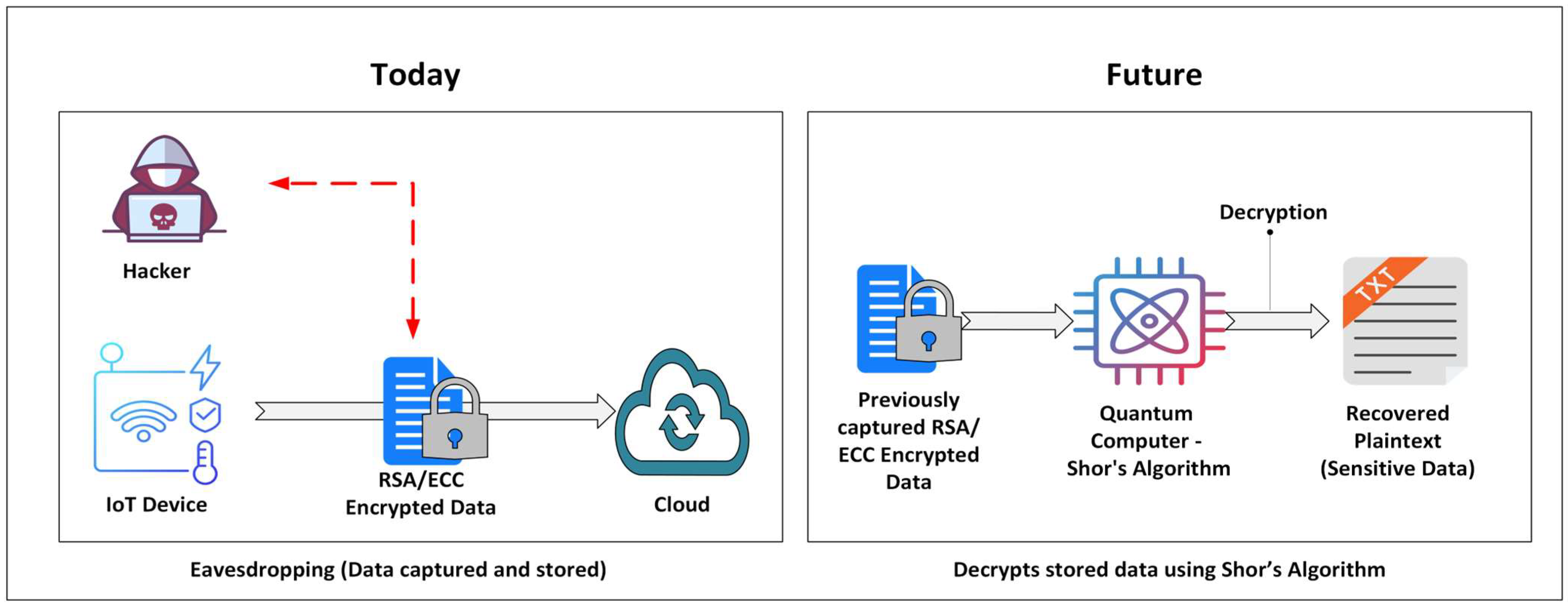

2.1. The Threat of Quantum Computing to Current Cryptography

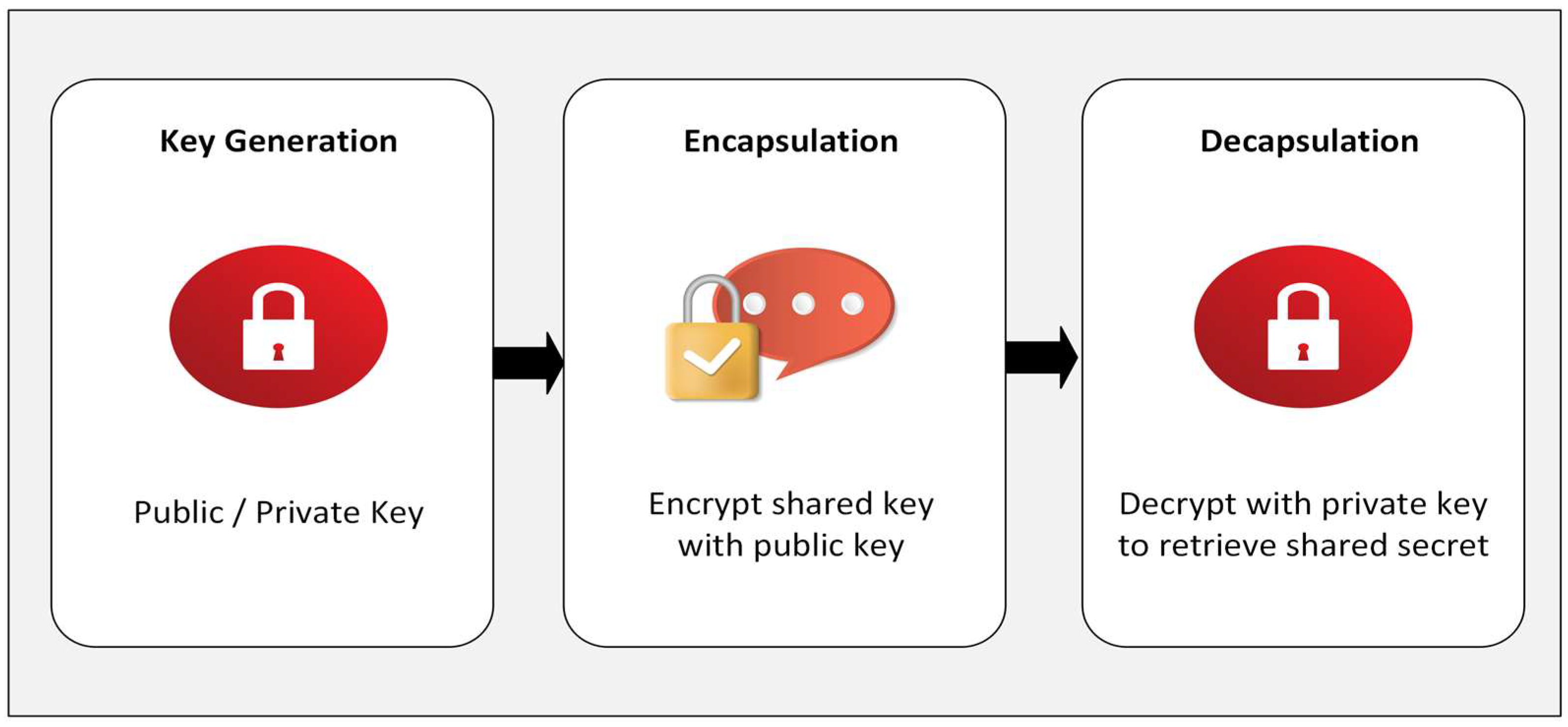

2.2. Overview of CRYSTALS-Kyber (ML-KEM)

- •

- Completes encapsulation on IoT class processors three to five times faster than classical schemes, reducing latency and energy consumption during the handshake process.

- •

- Constant-time C implementations achieve 2–4 ms encapsulation on Cortex-M4 devices within the same power envelope (based on benchmark studies summarized in Section 2.4).

- •

- Its simple message-independent design makes it more resistant to side-channel attacks than other lattice-based alternatives.

2.3. Mathematical Foundations of Kyber and Lattice-Based Cryptography

2.4. Key Prior Studies on PQC (Kyber) in IoT and Cloud Settings

- •

- Fitzgibbon et al. (2023) benchmarked NIST’s PQC finalists on a Raspberry Pi 4, representing a typical IoT class device [4]. Among the candidates, CRYSTALS-Kyber appeared as the fastest KEM, with key generation, encapsulation, and decapsulation completing in the hundreds of microseconds [14]. Kyber consistently outperformed other candidates on low-power platforms, confirming its suitability for resource-constrained IoT devices. Additionally, Dilithium was identified as the most efficient signature algorithm on the same platform, which is relevant for future authentication needs [4].

- •

- Sajimon et al. (2022) implemented several NIST PQC finalists (Level 3 security), including Kyber, on a Raspberry Pi 4 running Linux, simulating a typical IoT edge device [5]. Their evaluation recommended suitable PQC schemes based on performance in constrained environments. While specific metrics were not detailed, Kyber was among the top performers due to its known speed, reinforcing its practicality for real-world IoT deployments.

- •

- Bürstinghaus et al. (2020) integrated Kyber for key exchange and SPHINCS+ for digital signatures into an embedded TLS library (mbedTLS) [6]. Their tests on lightweight devices revealed that Kyber’s key agreement outperformed classical ECC (ECDH) by approximately 10× in speed. However, the addition of SPHINCS+ introduced high latency and memory overhead during TLS handshakes. This emphasizes the need to carefully select lightweight signature algorithms, suggesting Dilithium may be a more practical alternative for IoT use. This underscores that full PQC stacks require a balanced selection of encryption and signature schemes.

- •

- K. Mayes (2020) demonstrated that Kyber-768 on an ultra-constrained device was implemented on a Multi-application Operating System (MULTOS) security module with 13 KB of RAM [15]. Although successful, the encapsulation process took nearly 10 s, even with a cryptographic co-processor, demonstrating that Kyber can function in minimal memory environments but at the cost of speed. A related study implementing a Kyber-768 variant on a similar smart card platform with a cryptographic co-processor reported concrete performance figures: key generation in 79.6 ms, encapsulation in 102.4 ms, and decapsulation in 132.7 ms. These results demonstrate that Kyber can function in minimal memory environments with promising speed [16]. This sets a lower bound for Kyber’s practicality and suggests real-world use should target hardware at or above Cortex-M4/M7 levels.

- •

- Kumari et al. (2022) reviewed about 70 studies mapping PQC to microcontrollers and gateways [17]. They found lattice-based KEMs, particularly Kyber, offered the best trade-off among ciphertext size, speed, and code footprint (<10 KB flash, <4 KB RAM), while noting side-channel and key management challenges.

- •

- Mahdi and Abdullah (2025) emphasize that while algorithms such as CRYSTALS-Kyber are computationally efficient, practical deployment still faces hurdles [18]. These include energy consumption, hardware limitations, and scalability across heterogeneous IoT devices. Also, they proposed optimization techniques currently under exploration, such as hardware acceleration, algorithmic improvement, and hybrid frameworks to enhance feasibility. Long-term success will demand systematic engineering efforts to balance security, efficiency, and scalability.

- •

- Chung et al. (2022) evaluated Kyber-512/768 and other NIST finalists in a TLS 1.3 stack running on a Raspberry Pi 4 manufactured by Raspberry Pi Ltd., Cambridge, UK (Cortex-A72) and an STM32F411 manufactured by STMicroelectronics, Geneva, Switzerland (Cortex-M4) [19]. Full handshakes completed in 1.1 to 1.4 × the latency and fit within 32 KB RAM, showing post-quantum security is feasible on IoT hardware.

- •

- Tasopoulos et al. (2022) demonstrated that implementing PQC in TLS 1.3 for resource-constrained devices increases execution time, memory usage, and bandwidth requirements [20]. Similarly, Abbasi et al. (2025) reported that trustful PQC implementation can raise handshake size by up to 7× compared to classical approaches, although they showed that optimization strategies can reduce bandwidth demands by 40–60% [21]. Beyond TLS, Blanco-Romero et al. (2024) integrated PQC into IoT protocols such as CoAP and MQTT-SN, addressing the limited understanding of PQC’s impact on lightweight communication mechanisms [22]. Similarly, Paul et al. (2021) investigated PQC integration with Trusted Platform Modules (TPMs) in TLS, and they found it feasible but noted performance degradation when offloading hash computations [23]. Together, these works highlight both the challenges and opportunities of PQC adoption in IoT environments, emphasizing the need for optimized implementations to balance security, performance, and scalability.

- •

- Achoe (2025) recommends as future work to develop custom-built lightweight PQC-friendly versions of MQTT, CoAP, and 6LoWPAN [16]. This highlights a recognized need for research focused specifically on these IoT protocols.

- •

- Kumar et al. (2022) and Almutairi & Sheldon (2025) surveyed post-quantum cryptography in IoT and IoT-Cloud contexts, emphasizing the urgency of migrating IoT systems to quantum-safe algorithms [24,25]. Their works outline candidate schemes, integration challenges, and highlight PQC as an emerging solution to strengthen IoT-Cloud security, though neither includes an implementation study, serving primarily as conceptual motivation. On the industry side, cloud providers such as AWS have begun testing hybrid TLS configurations with Kyber in production environments, signaling that cloud infrastructures are PQC-ready and shifting the research focus toward IoT integration [26]. Alongside the transition to PQC, for instance, Hazber et al. propose a framework that leverages blockchain and AI-driven threat detection to enhance data integrity and scalability. This highlights a different but complementary approach to supporting IoT security [27].

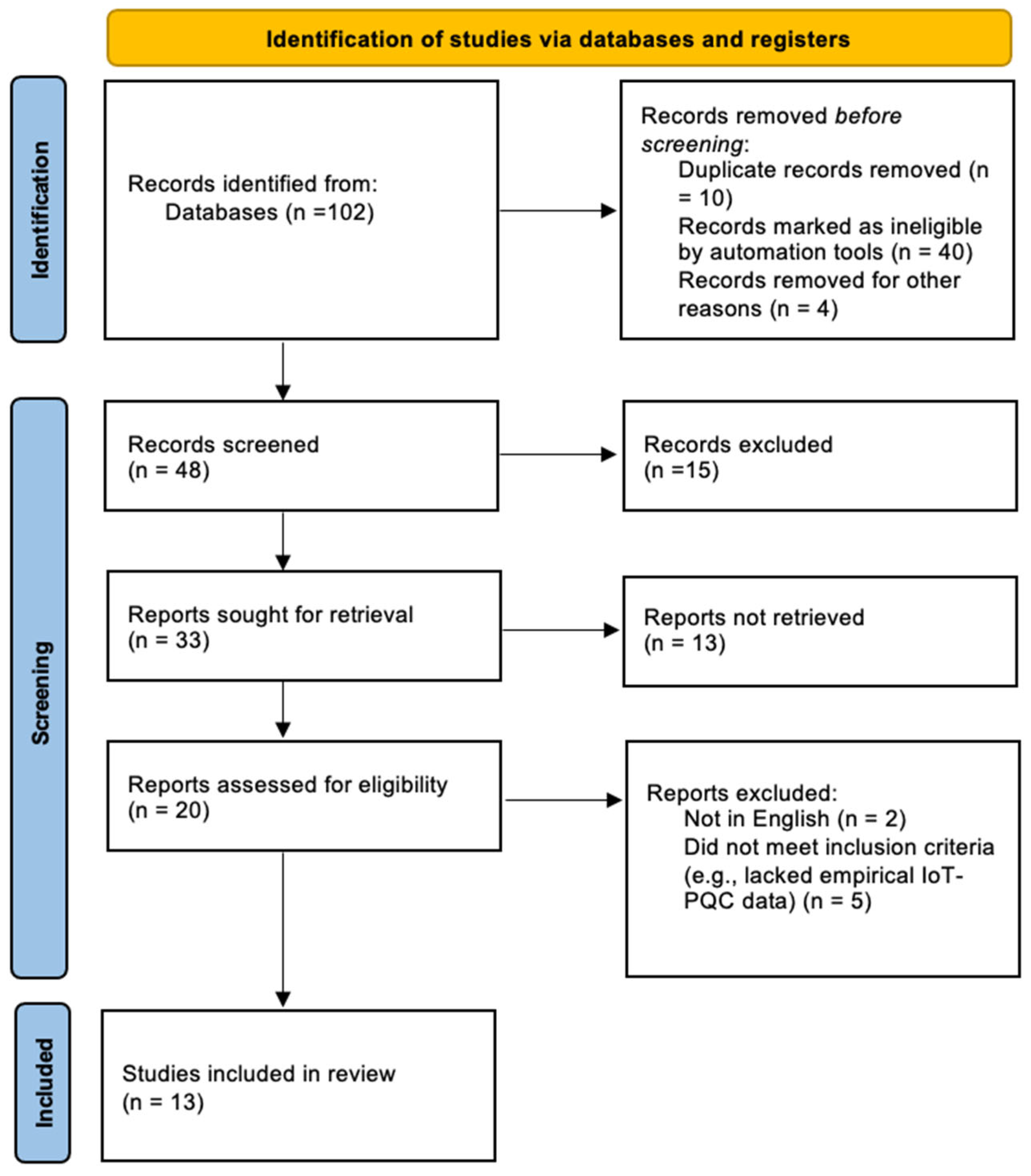

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Focus

3.2. Eligibility Criteria

3.3. Information Sources and Search Strategy

3.4. Selection Process and Data Extraction

3.5. Synthesis Approach

4. Performance Comparison: PQC vs. Traditional Crypto (RSA/ECC)

4.1. Execution Speed

4.2. Communication Overhead (Key/Ciphertext Sizes)

4.3. Symmetric Encryption Throughput

4.4. Overall Feasibility

5. Discussion: Identified Research Gaps and Challenges

5.1. The Primary Research Gap: Network Resilience in Lightweight Protocols Under Unreliable Network Conditions (RQ4)

- •

- •

- Limitation: These studies focused only on computational feasibility and explicitly excluded network-level factors such as packet loss and high latency.

- •

- Research needs: PQC’s larger key sizes and ciphertexts are most impactful in lossy IoT environments. No existing study has quantified how handshake success rates, retransmissions, and latency evolve under degraded conditions. This review asserts that the central unanswered question for the field is: What happens when these IoT protocols are tested in more realistic network environments? Therefore, future work should utilize simulation-based and real-world testbeds to evaluate the performance of PQC-resilient MQTT/CoAP under constrained networks.

5.2. Related Challenges and Future Work

5.2.1. Practical Integration Challenges (RQ1 and RQ3)

5.2.2. Resource Constraints and Optimizations (RQ2 and RQ3)

5.2.3. Security Analysis in IoT Context (RQ3)

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| IoT | Internet of Things | NIST | National Institute of Standards and Technology |

| PQC | Post-Quantum Cryptography | RSA | Rivest–Shamir–Adleman |

| ECC | Elliptic Curve Cryptography | CPU | Central Processing Unit |

| TLS | Transport Layer Security | MQTT | Message Queuing Telemetry Transport |

| CoAP | Constrained Application Protocol | KEM | Key Encapsulation Mechanisms |

| mbedTLS | embedded TLS library | RAM | Random Access Memory |

| LPWANs | Low-power WAN | HQC | Hamming Quasi-Cyclic |

| MULTOS | Multi-application Operating System | Cortex | A brand name for a family of processor cores developed by Arm. |

| WAN | Wide Area Network | RQ | research questions |

| M-LWE | Module Learning with Errors | SPHINCS+ | stateless hash-based digital signature scheme |

References

- Demir, E.D.; Bilgin, B.; Onbasli, M.C. Performance Analysis and Industry Deployment of Post-Quantum Cryptography Algorithms. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2503.12952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, D.; Lange, T. Post-quantum cryptography. Nature 2017, 549, 188–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Information Technology Laboratory. Post-Quantum Cryptography Standardization. 2024. Available online: https://csrc.nist.gov/projects/post-quantum-cryptography/selected-algorithms (accessed on 17 March 2024).

- Fitzgibbon, G.; Ottaviani, C. Constrained Device Performance Benchmarking with the Implementation of Post-Quantum Cryptography. Cryptography 2024, 8, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sajimon, P.C.; Jain, K.; Krishnan, P. Analysis of Post-Quantum Cryptography for Internet of Things. In Proceedings of the 2022 6th International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Control Systems (ICICCS), Madurai, India, 25–27 May 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bürstinghaus-Steinbach, K.; Krauß, C.; Niederhagen, R.; Schneider, M. Post-Quantum TLS on Embedded Systems: Integrating and Evaluating Kyber and SPHINCS+ with mbed TLS. In Proceedings of the 15th ACM Asia Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Taipei, Taiwan, 5–9 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Abuarqoub, A. Security Challenges Posed by Quantum Computing on Emerging Technologies. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Future Networks and Distributed Systems (ICFNDS), St. Petersburg, Russia, 26–27 November 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kirsch, Z.; Chow, M. Quantum Computing: The Risk to Existing Encryption Methods. 2015. Available online: https://www.cs.tufts.edu/comp/116/archive/fall2015/zkirsch.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Alagic, G.; Barker, E.; Chen, L.; Moody, D.; Robinson, A.; Silberg, H.; Waller, N. Recommendations for Key-Encapsulation Mechanisms. NIST Special Publication (SP) 800-227. 2025. Available online: https://csrc.nist.gov/pubs/sp/800/227/ipd (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Alagic, G.; Bros, M.; Ciadoux, P.; Cooper, D.; Dang, Q.; Dang, T.; Kelsey, J.; Lichtinger, J.; Liu, Y.-K.; Miller, C.; et al. Status Report on the Fourth Round of the Nist Post-Quantum Cryptography Standardization Process; National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Cryptographic Suite for Algebraic Lattices. Available online: https://pq-crystals.org/kyber/index.shtml (accessed on 6 August 2025).

- FIPS; NIST. Module-Lattice-Based Key-Encapsulation Mechanism Standard; National Institute of Standards and Technology: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Zong, C. The Mathematical Foundation of Post-Quantum Cryptography. Research 2024, 8, 0801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, T.; Ramachandran, G.; Jurdak, R. Post-Quantum Cryptography for Internet of Things: A Survey on Performance and Optimization. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2401.17538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayes, K. Performance Evaluation and Optimisation for Kyber on the MULTOS IoT Trust-Anchor. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Smart Internet of Things (SmartIoT), Beijing, China, 14–16 August 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Achoe, D. Post-Quantum Cryptography for Securing Future-Proof Smart Energy Infrastructure. 2025. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/392734298_POST-QUANTUM_CRYPTOGRAPHY_FOR_SECURING_FUTURE-PROOF_SMART_ENERGY_INFRASTRUCTURE (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Kumari, S.; Singh, M.; Singh, R.; Tewari, H. Post-quantum cryptography techniques for secure communication in resource-constrained Internet of Things devices: A comprehensive survey. Softw. Pract. Exp. 2022, 52, 2047–2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdi, L.H.; Abdullah, A.A. Fortifying Future IoT Security: A Comprehensive Review on Lightweight Post-Quantum Cryptography. Eng. Technol. Appl. Sci. Res. 2025, 15, 21812–21821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, C.C.; Pai, C.C.; Ching, F.S.; Wang, C.; Chen, L.J. When post-quantum cryptography meets the internet of things. In Proceedings of the 20th Annual International Conference on Mobile Systems, Applications and Services, Portland, Oregon, 27 June–1 July 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Tasopoulos, G.; Li, J.; Fournaris, A.P.; Zhao, R.K.; Sakzad, A.; Steinfeld, R. Performance Evaluation of Post-Quantum TLS 1.3 on Resource-Constrained Embedded Systems. In Information Security Practice and Experience; Springer: Cham, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Abbasi, M.; Cardoso, F.; Váz, P.; Silva, J.; Martins, P. A Practical Performance Benchmark of Post-Quantum Cryptography Across Heterogeneous Computing Environments. Cryptography 2025, 9, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco-Romero, J.; Lorenzo, V.; Almenares, F.; Sánchez, D.D.; Campo, C.; Rubio, C.G. Integrating Post-Quantum Cryptography into CoAP and MQTT-SN Protocols. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Symposium on Computers and Communications (ISCC), Paris, France, 26–29 June 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Paul, S.; Schick, F.; Seedorf, J. TPM-Based Post-Quantum Cryptography: A Case Study on Quantum-Resistant and Mutually Authenticated TLS for IoT Environments. In Proceedings of the ARES’21: The 16th International Conference on Availability, Reliability and Security, Vienna, Austria, 17–20 August 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, R.; Goyal, R. Top Threats to Cloud: A Three-Dimensional Model of Cloud Security Assurance. In Computer Networks and Inventive Communication Technologies; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 683–705. [Google Scholar]

- Almutairi, M.; Sheldon, F.T. IoT–Cloud Integration Security: A Survey of Challenges, Solutions, and Directions. Electronics 2025, 14, 1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blog, A.S. How to Tune TLS for Hybrid Post-Quantum Cryptography with Kyber. AWS. 2022. Available online: https://aws.amazon.com/blogs/security/how-to-tune-tls-for-hybrid-post-quantum-cryptography-with-kyber/#:~:text=How%20to%20tune%20TLS%20for,Maven%20project%20to%20use (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Hazber, M.A.G.; Albarrak, A.; Altamimi, M.; Muniasamy, A.; Islam, A.; Ahmed, M.A.; Alalayah, K.M.; Hussain, S.; Irshad, R.R. A blockchain-enabled edge computing framework leveraging artificial neural network and aquila optimization to enhance security and scalability of cloud-based IoT platforms. Clust. Comput. 2025, 28, 816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.B.; Seo, S.C. An Optimized Instantiation of Post-Quantum MQTT protocol on 8-bit AVR Sensor Nodes. In Proceedings of the ASIA CCS’25: The 20th ACM Asia Conference on Computer and Communications Security, Hanoi, Vietnam, 25–29 August 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Commey, D.; Appiah, B.; Klogo, G.S.; Bagyl-Bac, W.; Gadze, J.D.; Alsenani, Y.; Crosby, G.V. Performance Analysis and Deployment Considerations of Post-Quantum Cryptography for Consumer Electronics. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.02239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, Y.; Bozhko, J.; Tonyali, S.; Harrilal-Parchment, R.; Cebe, M.; Akkaya, K. A comprehensive and realistic performance evaluation of post-quantum security for consumer IoT devices. Internet Things 2025, 33, 101650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehsan, M.A.; Alayed, W.; Rehman, A.U.; Hassan, W.; Zeeshan, A. Post-Quantum KEMs for IoT: A Study of Kyber and NTRU. Symmetry 2025, 17, 881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Önder, E. Measuring the Performance of Post-Quantum Cryptography on Embedded Systems. Ph.D. Thesis, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, Worcester, MA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Hanafi, B.; Ali, M. Analyzing the research impact in post quantum cryptography through scientometric evaluation. Discov. Comput. 2025, 28, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernstein, D.J.; Bhargavan, K.; Bhasin, S.; Chattopadhyay, A.; Chia, T.K.; Kannwischer, M.J.; Paiva, T.; Ravi, P.; Tamvada, G. KyberSlash: Exploiting secret-dependent division timings in Kyber implementations. Cryptology ePrint Archive. 2024. Available online: https://eprint.iacr.org/2024/1049 (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Iavich, M.; Kuchukhidze, T. Investigating CRYSTALS-Kyber Vulnerabilities: Attack Analysis and Mitigation. Cryptography 2024, 8, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanal, P.; Karagoz, E.; Seo, H.; Azarderakhsh, R.; Mozaffari-Kermani, M. Kyber on ARM64: Compact Implementations of Kyber on 64-Bit ARM Cortex—A Processors; Lecture Notes of the Institute for Computer Sciences, Social Informatics and Telecommunications Engineering; Springer: Cham, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Canto, A.C.; Kaur, J.; Kermani, M.M.; Azarderakhsh, R. Algorithmic Security is Insufficient: A Comprehensive Survey on Implementation Attacks Haunting Post-Quantum Security. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2305.13544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghavi, B.; Azarderakhsh, R.; Kermani, M.M. ParallelNTT: Maximizing Performance of Forward and Inverse NTT on FPGA for ML-DSA and ML-KEM. In Proceedings of the Great Lakes Symposium on VLSI 2025, New Orleans, LA, USA, 30 June–2 July 2025. [Google Scholar]

| Year | Milestone |

|---|---|

| 2016 | NIST issues a call for PQC proposals. |

| December 2017–January 2019 | Round 1 (69 candidates) → Round 2 (26). |

| July 2020 | Round 3 finalists and alternates announced (7 KEM/sig algorithms). |

| 5 July 2022 | NIST selects CRYSTALS-Kyber as the sole KEM to be standardized, alongside Dilithium, Falcon and SPHINCS+ for signatures. |

| 13 August 2024 | Final FIPS 203—Module-Lattice-Based Key-Encapsulation Mechanism (ML-KEM), derived from Kyber, is published; it becomes the primary federal standard for general-purpose encryption [9]. |

| 11 March 2025 | NIST announces Hamming Quasi-Cyclic (HQC) as an additional KEM for specialized use cases and releases status report NIST IR 8545 on Round 4 [10]. |

| Variant | NIST Level | Public-Key (Bytes) | Cipher-Text (Bytes) | Symmetric Comparable |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kyber-512 | 1 | 800 | 768 | AES-128 |

| Kyber-768 | 3 | 1184 | 1088 | AES-192 |

| Kyber-1024 | 5 | 1568 | 1568 | AES-256 |

| Study | Focus Protocol | Device Benchmark | End-to-End Test | Network Condition Analysis | Key Contribution | Remaining Gap |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fitzgibbon et al. (2023) [4] | (Implicitly TLS) | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | Kyber benchmarked on Raspberry Pi, the fastest KEM among candidates. | Limited to device-level tests and not IoT protocols |

| Sajimon et al. (2022) [5] | TLS/IoT devices | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | Implemented PQC finalists on Linux-based edge devices; Kyber efficient | Did not include network or protocol-level performance |

| Bürstinghaus et al. (2020) [6] | TLS | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | Integrated Kyber + SPHINCS+ into mbedTLS, and it has faster handshakes than ECC | Signature scheme overhead too high for IoT |

| Mayes (2020) [15] | N/A (standalone Kyber) | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | Demonstrated Kyber-768 on ultra-constrained MULTOS (13 KB RAM), and its encapsulation is feasible but slow (~10 s without co-processor and ~100 ms with) | Shows Kyber’s practicality floor and no IoT protocol integration |

| Kumari et al. (2022) [17] | Survey | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | Comprehensive survey of PQC for IoT microcontrollers | No implementation results, and it is theoretical |

| Chung et al. (2022) [19] | TLS | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | Benchmarked Kyber on Cortex-M4 and Pi4, and it is feasible for IoT. | No MQTT/CoAP evaluation |

| Mahdi & Abdullah (2025) [18] | General IoT | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | Highlighted optimization, energy, scalability challenges | No protocol-level or experimental validation |

| Tasopoulos et al. (2022) [20] | TLS 1.3 | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | Showed PQC increases execution time, memory, bandwidth | Limited to TLS and no IoT protocols |

| Blanco-Romero et al. (2024) [22] | CoAP, MQTT-SN | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | Integrated PQC into lightweight IoT protocols | No adverse network analysis |

| Paul et al. (2021) [23] | TLS with TPM | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | Demonstrated PQC in TLS with TPM offloading | Performance hit with TPM hash offload |

| Achoe (2025) [16] | MQTT/CoAP | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | Called explicitly for PQC-secured lightweight protocols | No implementation, and it is only a call for research |

| YoungBeom et al. (2025) [28] | MQTT | ✓ | ✓ (partial) | ✗ | First KEM-MQTT implementation on 8-bit AVR nodes. | Excluded network performance |

| Abbasi et al. (2025) [21] | TLS (multi-platform) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Systematic TLS benchmarks across devices | TLS only and missing IoT protocols |

| Identified Gap | MQTT/CoAP | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | - | No existing study systematically evaluates Kyber over MQTT under adverse network conditions. |

| Algorithm | NIST Security Level | Public Key Size (Bytes) | Ciphertext Size (Bytes) | Relative Speed (Key Exchange) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECC (P-256) | 1 | ~64 | N/A | Baseline (1×) |

| RSA-2048 | 1 | 256 | N/A | Slower (~0.7×) |

| Kyber-512 | 1 | 800 | 768 | Much Faster (~3–5×) |

| Kyber-768 | 3 | 1184 | 1088 | Much Faster (~3–5×) |

| Kyber-1024 | 5 | 1568 | 1568 | Much Faster (~3–5×) |

| Gap Area | Description | Supporting Studies | Insights and Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|

| PQC Resilience in Lightweight IoT Protocols | Most evaluations focus on TLS, but MQTT/CoAP is largely unexplored. One KEM-MQTT study excluded network resilience. | [16,22,28] | This review highlights the lack of studies on PQC resilience in MQTT and CoAP protocols, particularly under high-latency and lossy conditions, and recommends focused practical evaluation. |

| Integration Challenges | PQC is feasible in TLS, but signatures (SPHINCS+) cause high latency. Hybrid schemes are temporarily used. | [6,21] | Explore Dilithium or hybrid TLS and standardization for IoT protocols. |

| Resource Constraints and Optimization | Ultra-constrained devices can run Kyber, but slowly without co-processors. Energy is still an issue. | [15,18] | It identifies the need to measure how PQC algorithms affect speed, memory, and energy use on ultra-low-power microcontrollers. Also, it recommends future work on creating optimized versions for embedded systems. |

| Security Evaluation in IoT Context | Some side-channel risks were identified in Kyber (e.g., Kybe-Slash) and a few IoT-specific threat models. | [34,35] | It points out the gap in side-channel analysis of Kyber in IoT and recommends that future work address timing attacks and power analysis risks in constrained environments. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Almutairi, M.; Sheldon, F.T. Resilience of Post-Quantum Cryptography in Lightweight IoT Protocols: A Systematic Review. Eng 2025, 6, 346. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng6120346

Almutairi M, Sheldon FT. Resilience of Post-Quantum Cryptography in Lightweight IoT Protocols: A Systematic Review. Eng. 2025; 6(12):346. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng6120346

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlmutairi, Mohammed, and Frederick T. Sheldon. 2025. "Resilience of Post-Quantum Cryptography in Lightweight IoT Protocols: A Systematic Review" Eng 6, no. 12: 346. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng6120346

APA StyleAlmutairi, M., & Sheldon, F. T. (2025). Resilience of Post-Quantum Cryptography in Lightweight IoT Protocols: A Systematic Review. Eng, 6(12), 346. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng6120346