Design and Simulation of Thermally Stable Lead-Free BaHfSe3 Perovskite Solar Cells: Role of Interface Barrier Height and Temperature

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

| ETL | BaHfSe3 [20] | HTL | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Material | TiO2 [19] | ZrS2 [18] | ZnSe [33] | SnS2 [34] | Cu2O [19] | MoO3 [34] | CZTS [18] | MoS2 [34] | |

| Thickness (µm) | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Band gap (eV) | 3.2 | 2.5 | 2.81 | 1.85 | 1.5 | 2.17 | 3 | 1.5 | 1.29 |

| Electron affinity (eV) | 3.9 | 4.1 | 4.09 | 4.26 | 3.8 | 3.2 | 2.3 | 4.2 | 4.2 |

| Dielectric permittivity (relative) | 9 | 16.4 | 8.6 | 17.7 | 11 | 7.11 | 18 | 10 | 3 |

| CB density of states (1/cm3) | 1.0 × 1021 | 2.2×1018 | 2.2×1018 | 7.32×1018 | 2.2×1018 | 2.02×1017 | 1.0×1019 | 2.2×1018 | 2.2×1018 |

| VB density of states (1/cm3) | 2.0×1020 | 1.8×1019 | 1.8×1018 | 1.0×1019 | 1.8×1019 | 1.1×1019 | 2.2×1018 | 1.8×1019 | 1.9×1019 |

| Electron mobility (cm/s) | 20 | 2.3×103 | 4×102 | 50 | 9.4×10 −2 | 2.0×102 | 210 | 1.0×102 | 100 |

| Hole mobility (cm/s) | 10 | 1.3×103 | 1.1×101 | 25 | 3.5×102 | 80 | 210 | 25 | 150 |

| Donor density (1/cm3) | 2.0×1019 | 1.0×1015 | 1.0×10 18 | 9.85×10 19 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Acceptor density (1/cm3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.0×1018 | 1.0×10 18 | 1.0×10 18 | 1.0×10 17 | 1.0×10 17 |

| Contact/Parameter | Front Contact (FTO) | Back Contact (Au) |

|---|---|---|

| Metal work function, (eV) | 4.07 [35] | 5.1 [36] |

| Electron thermal velocity | 1.0 × 107 | 1.0 × 107 |

| Hole Thermal Velocity | 1.0 × 107 | 1.0 × 107 |

3. Results and Discussion

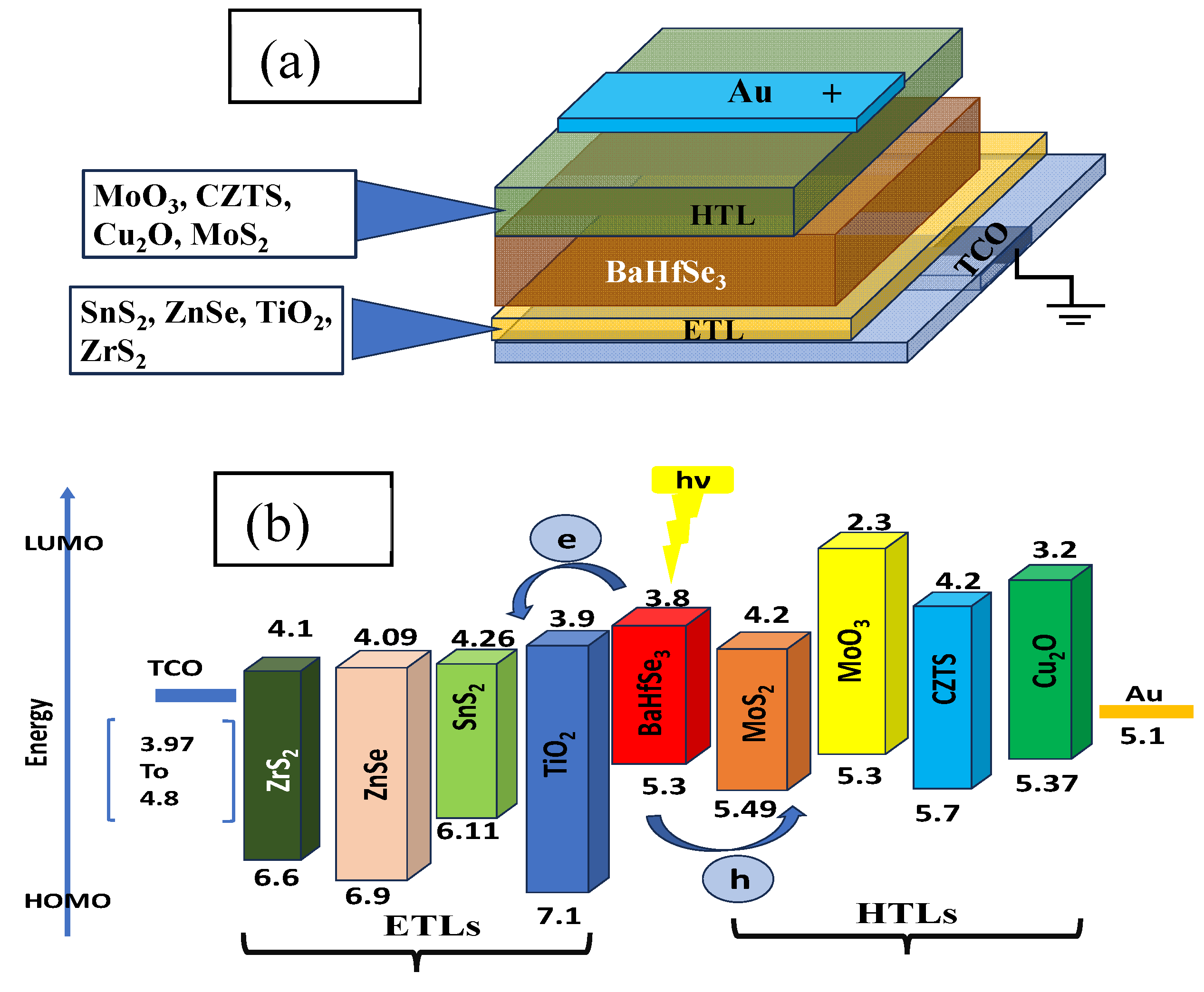

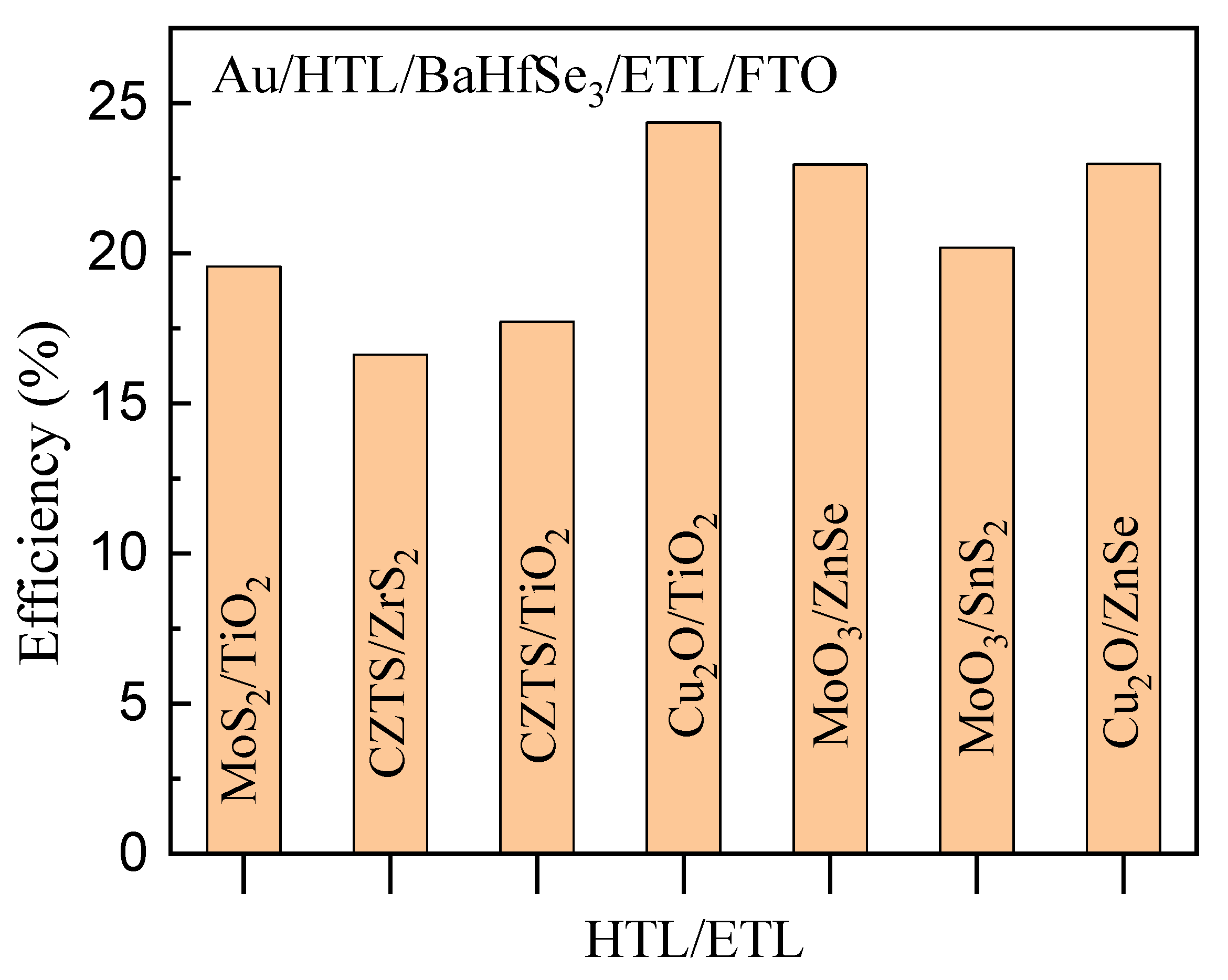

3.1. Optimization of ETL and HTL Material

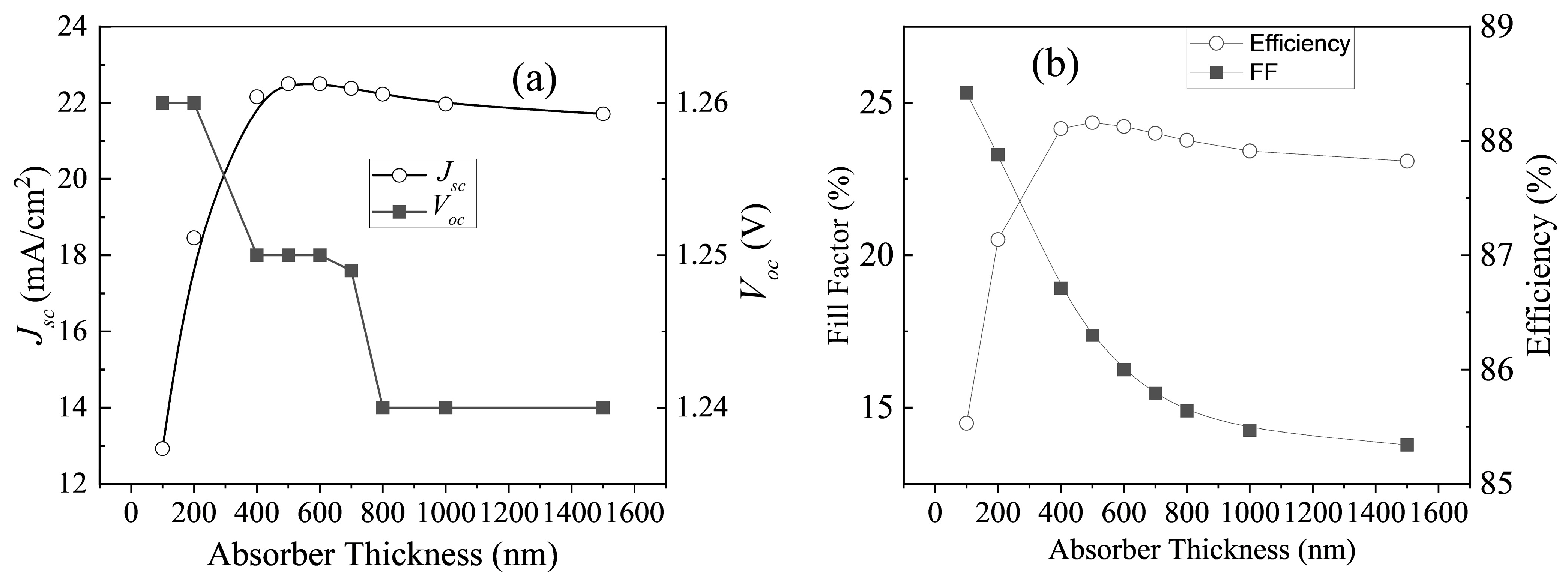

3.2. Optimization of Absorber Layer Thickness

3.3. Optimization of ETL and HTL Layers Thickness

3.4. Evaluation of the Shockley–Queisser Efficiency Limit and the Role of Radiative Recombination

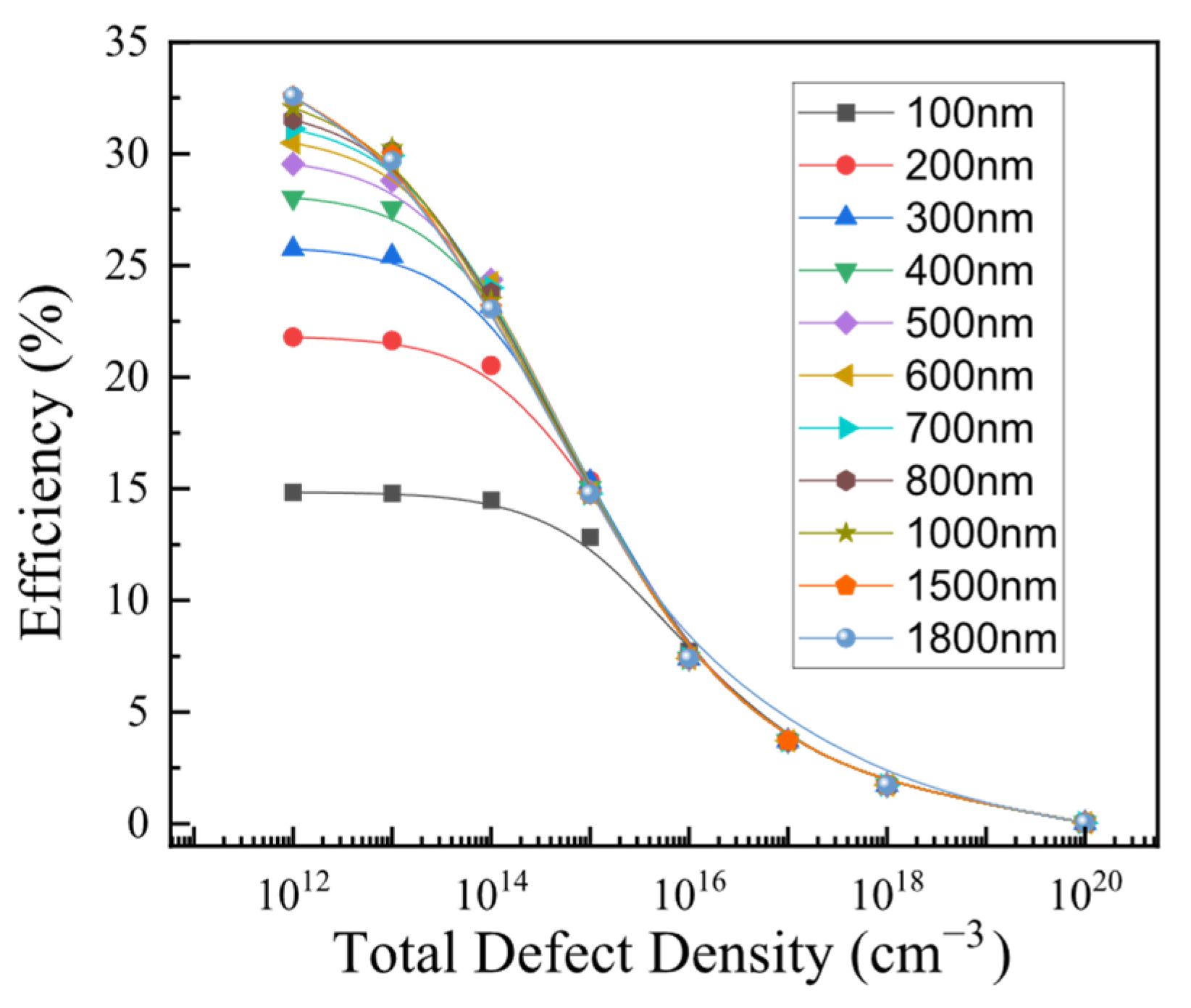

3.5. Effect of Absorber Thickness and Trap Density on Device Performance

- •

- Low trap density regime (): The minority carrier diffusion length is much greater than (), enabling nearly all photogenerated carriers to be collected efficiently. Increasing improves light absorption and thus short-circuit current density , resulting in monotonically increasing power conversion efficiency (PCE). Efficiency tends to saturate at very high thicknesses ( nm) as absorption approaches completeness and marginal gains diminish.

- •

- Moderate trap density regime (): The diffusion length becomes comparable to (), yielding an optimal absorber thickness around 500–700 nm. Thinner devices suffer from insufficient photon absorption causing low , while thicker films experience pronounced Shockley-Read-Hall (SRH) recombination losses, which reduce carrier collection efficiency and degrade performance beyond nm.

- •

- High trap density regime (): SRH recombination dominates; carrier lifetimes and diffusion lengths shrink drastically (), causing rapid recombination before carriers reach contacts. Here, and overall efficiency become largely independent of thickness and converge to a low value (~3.7%), reflecting severe recombination losses regardless of

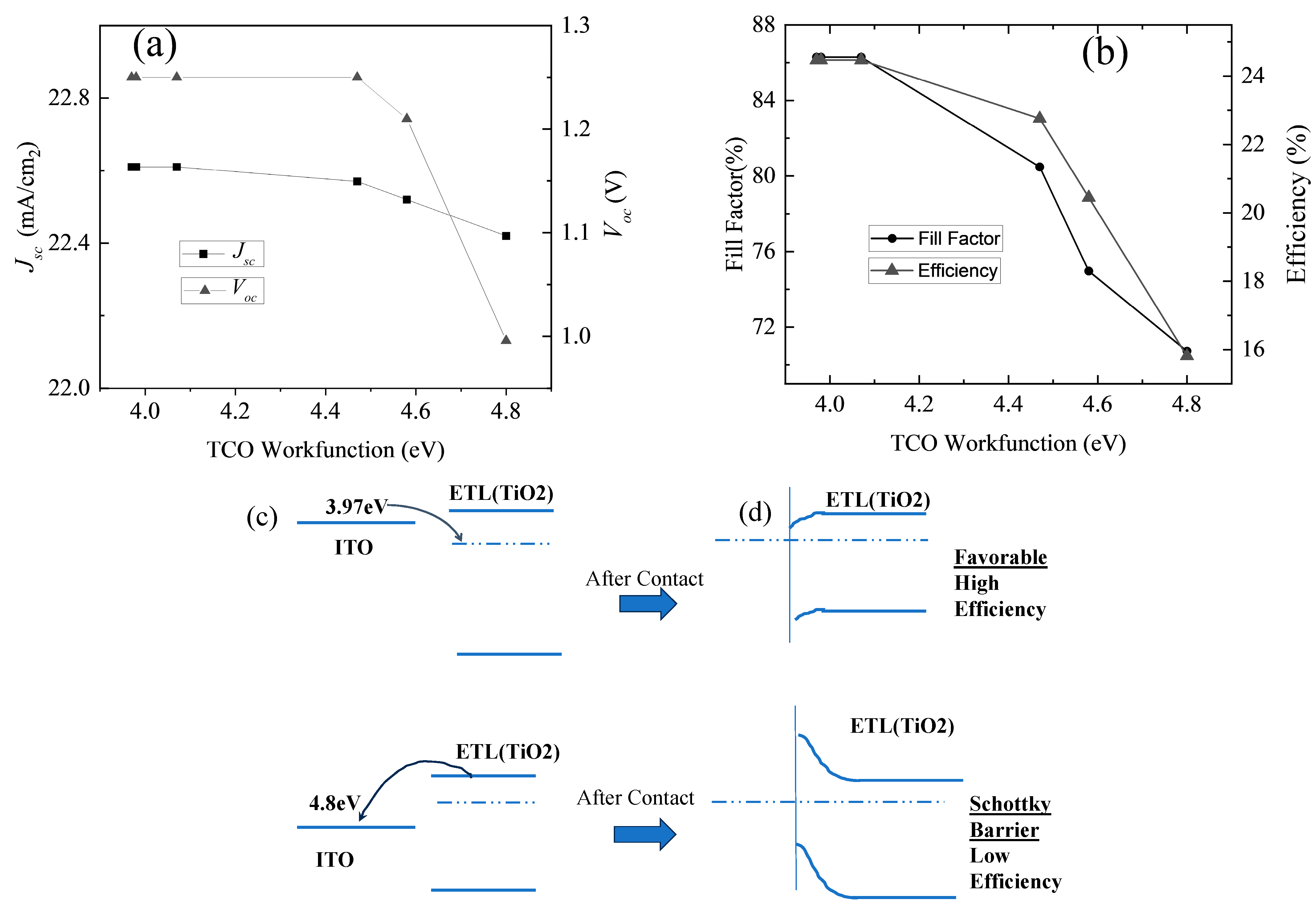

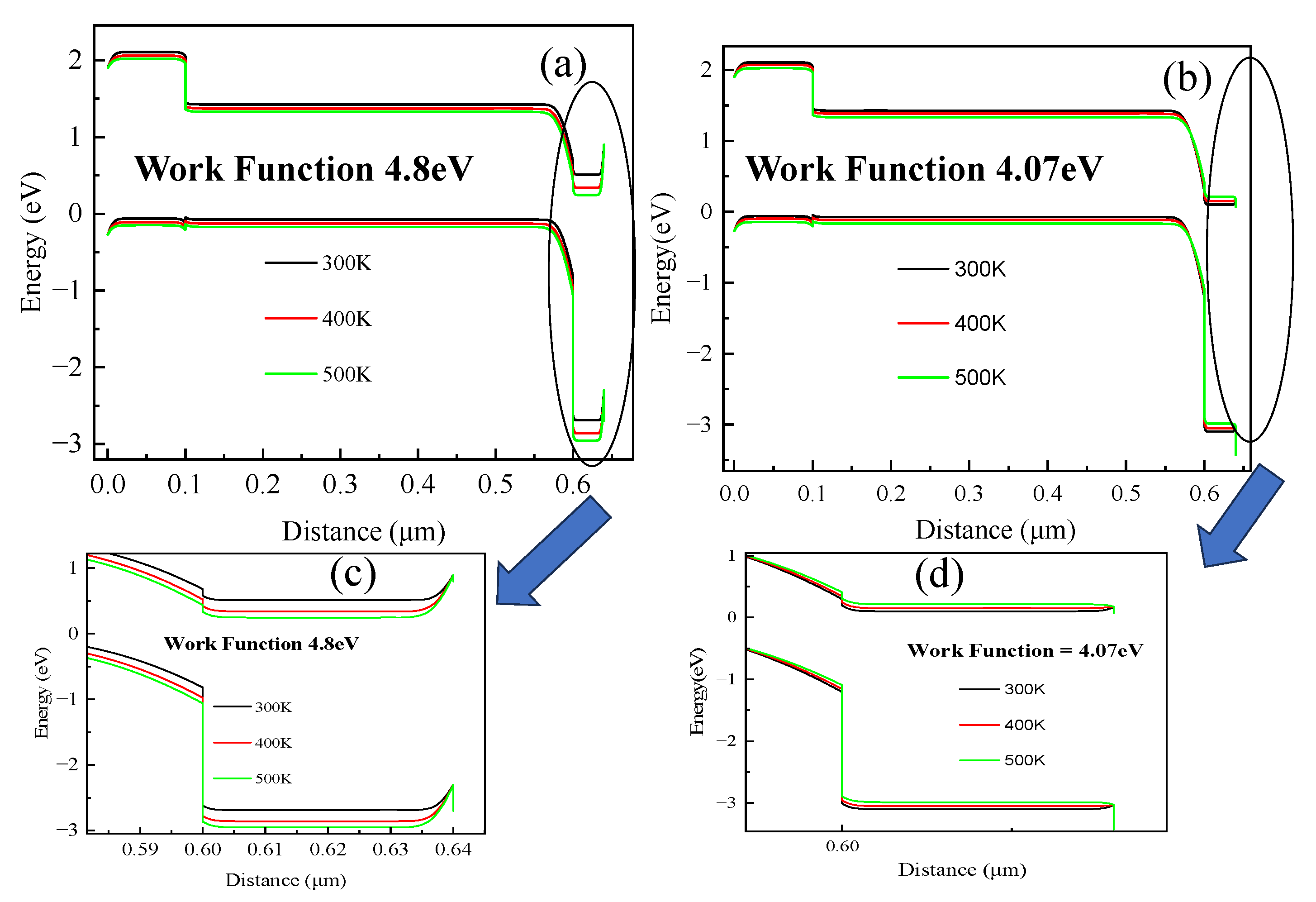

3.6. Role of Transparent Conducting Oxide (Front Contact) Work Function

- •

- Case 1: ITO Work Function (Lower Work Function)

- •

- Case 2: ITO Work Function (Higher Work Function)

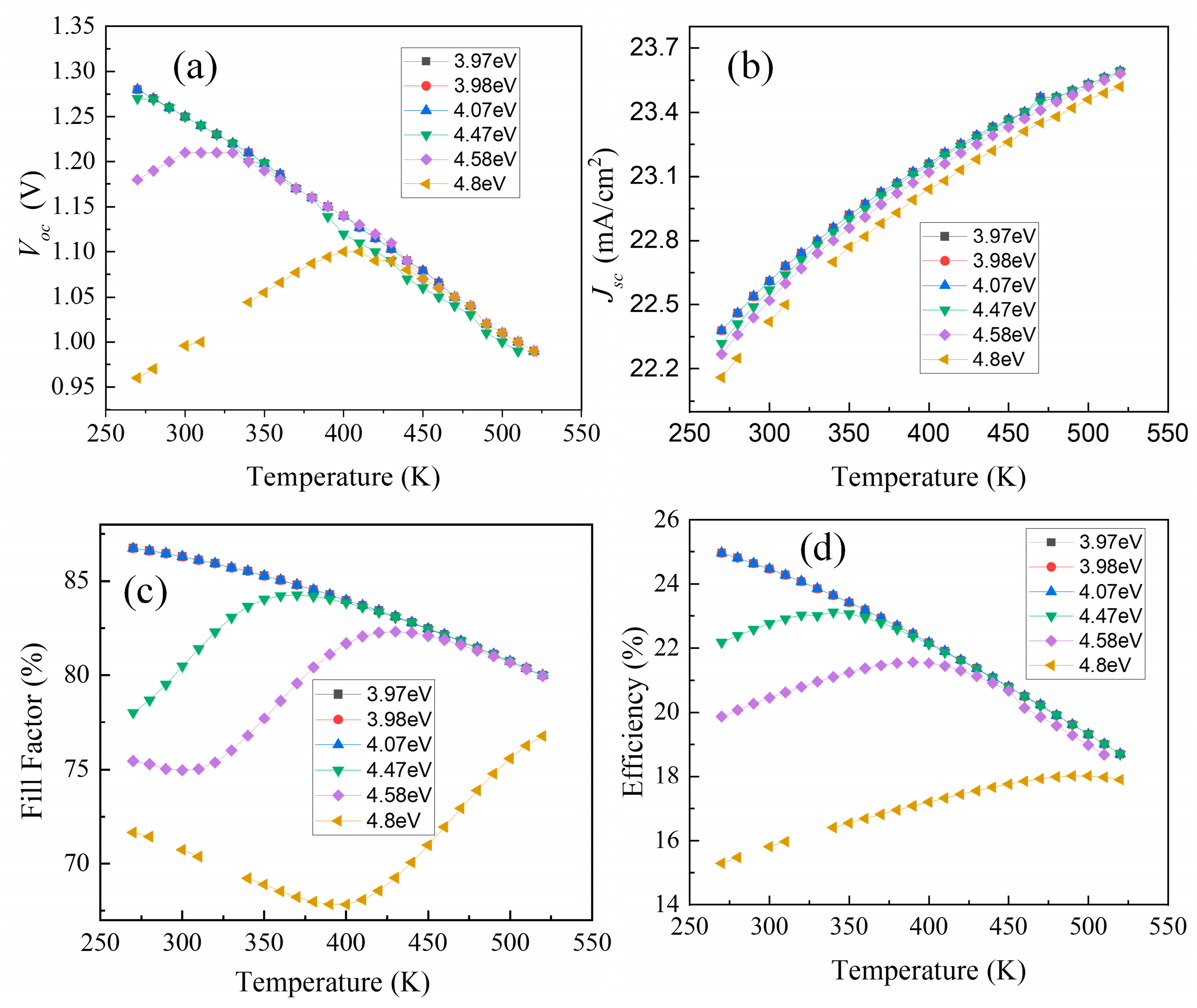

3.7. Temperature Dependence of Photovoltaic Parameters

- (a)

- Open Circuit Voltage (Voc) Behavior

- (b)

- Short-Circuit Current Density (Jsc) Behavior

- (c)

- Fill Factor Behavior

- (d)

- Efficiency () Behaviour

- Low WF (3.97–4.07 eV): Both and FF decrease monotonically, while increases slightly. The net effect is a monotonic decrease in efficiency.

- Moderate WF (4.47 eV): Despite a monotonically decreasing , the initial increase in FF causes the efficiency to first rise at low-to-intermediate temperatures. Beyond the temperature where FF peaks, efficiency decreases as recombination dominates.

- Deep WF (4.58–4.80 eV): Both and FF initially increase due to barrier reduction, leading to an initial rise in efficiency. At higher temperatures, increased recombination reduces and eventually saturates FF, producing a peak efficiency at intermediate temperature, similar to the behavior. Behaviors are summarized in the Table 3.

| WF (eV) | Voc Trend | FF Trend | Jsc Trend | η Trend |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3.97–4.07 | ↓ | ↓ | ↑ | ↓ |

| 4.47 | ↓ | ↑→↓ | ↑ | ↑→↓ |

| 4.58 | ↑→↓ | ↓→↑→↓ | ↑ | ↑→↓ |

| 4.80 | ↑→↓ | ↓→↑ | ↑ | ↑→↓ |

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hamukwaya, S.L.; Hao, H.; Zhao, Z.; Dong, J.; Zhong, T.; Xing, J.; Hao, L.; Mashingaidze, M.M. A Review of Recent Developments in Preparation Methods for Large-Area Perovskite Solar Cells. Coatings 2022, 12, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afre, R.A.; Pugliese, D. Perovskite Solar Cells: A Review of the Latest Advances in Materials, Fabrication Techniques, and Stability Enhancement Strategies. Micromachines 2024, 15, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roy, P.; Ghosh, A.; Barclay, F.; Khare, A.; Cuce, E. Perovskite Solar Cells: A Review of the Recent Advances. Coatings 2022, 12, 1089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, R.; Dai, Y.; Wang, R.; Li, L.; Park, B.; Chu, W.; Wang, C.; Li, Z.; Chen, S.; Qiao, R. Enhanced Stability and Efficiency in Perovskite Solar Cells via Mixed-Metal Chalcohalide-Alloyed Formamidinium Lead Iodide. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 7343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Chen, L.; Yu, Y.; He, D.; Shai, X.; Zhang, S.; Zhang, Z.; Feng, J.; Yi, J.; Chen, J. Advancements of Highly Efficient Perovskite Based Tandem Solar Cells. Sci. China Mater. 2025, 68, 691–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khenkin, M.V.; Katz, E.A.; Abate, A.; Bardizza, G.; Berry, J.J.; Brabec, C.; Brunetti, F.; Bulović, V.; Burlingame, Q.; Di Carlo, A. Consensus Statement for Stability Assessment and Reporting for Perovskite Photovoltaics Based on ISOS Procedures. Nat. Energy 2020, 5, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, J.; Wang, Q.; Huo, J.; Gao, F.; Gan, Z.; Zhao, Q.; Li, H. Mechanisms and Suppression of Photoinduced Degradation in Perovskite Solar Cells. Adv. Energy Mater. 2021, 11, 2002326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kore, B.P.; Jamshidi, M.; Gardner, J.M. The Impact of Moisture on the Stability and Degradation of Perovskites in Solar Cells. Mater. Adv. 2024, 5, 2200–2217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazumdar, S.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, X. Stability of Perovskite Solar Cells: Degradation Mechanisms and Remedies. Front. Electron. 2021, 2, 712785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEC 61646; Thin-Film Terrestrial Photovoltaic (PV) Modules—Design Qualification and Type Approval. IEC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008.

- Conings, B.; Drijkoningen, J.; Gauquelin, N.; Babayigit, A.; D’Haen, J.; D’Olieslaeger, L.; Ethirajan, A.; Verbeeck, J.; Manca, J.; Mosconi, E. Intrinsic Thermal Instability of Methylammonium Lead Trihalide Perovskite. Adv. Energy Mater. 2015, 5, 1500477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habisreutinger, S.N.; Leijtens, T.; Eperon, G.E.; Stranks, S.D.; Nicholas, R.J.; Snaith, H.J. Carbon Nanotube/Polymer Composites as a Highly Stable Hole Collection Layer in Perovskite Solar Cells. Nano Lett. 2014, 14, 5561–5568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saliba, M.; Matsui, T.; Domanski, K.; Seo, J.-Y.; Ummadisingu, A.; Zakeeruddin, S.M.; Correa-Baena, J.-P.; Tress, W.R.; Abate, A.; Hagfeldt, A. Incorporation of Rubidium Cations into Perovskite Solar Cells Improves Photovoltaic Performance. Science 2016, 354, 206–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Su, Z.; Canil, L.; Hughes, D.; Aldamasy, M.H.; Dagar, J.; Trofimov, S.; Wang, L.; Zuo, W.; Jerónimo-Rendon, J.J. Highly Efficient Pin Perovskite Solar Cells That Endure Temperature Variations. Science 2023, 379, 399–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwenzer, J.A.; Rakocevic, L.; Gehlhaar, R.; Abzieher, T.; Gharibzadeh, S.; Moghadamzadeh, S.; Quintilla, A.; Richards, B.S.; Lemmer, U.; Paetzold, U.W. Temperature Variation-Induced Performance Decline of Perovskite Solar Cells. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 16390–16399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjogri, S.J.; Meyer, E.L. Chalcogenide Perovskites and Perovskite-Based Chalcohalide as Photoabsorbers: A Study of Their Properties, and Potential Photovoltaic Applications. Materials 2021, 14, 7857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Y.-Y.; Agiorgousis, M.L.; Zhang, P.; Zhang, S. Chalcogenide Perovskites for Photovoltaics. Nano Lett. 2015, 15, 581–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent Mercy, E.N.; Srinivasan, D.; Marasamy, L. Emerging BaZrS3 and Ba (Zr, Ti) S3 Chalcogenide Perovskite Solar Cells: A Numerical Approach toward Device Engineering and Unlocking Efficiency. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 4359–4376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karthick, S.; Velumani, S.; Bouclé, J. Chalcogenide BaZrS3 Perovskite Solar Cells: A Numerical Simulation and Analysis Using SCAPS-1D. Opt Mater 2022, 126, 112250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srinivasan, D.; Rasu Chettiar, A.-D.; Vincent Mercy, E.N.; Marasamy, L. Scrutinizing the Untapped Potential of Emerging ABSe3 (A = Ca, Ba; B = Zr, Hf) Chalcogenide Perovskites Solar Cells. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 3454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dallas, P.; Gkini, K.; Kaltzoglou, A.; Givalou, L.; Konstantakou, M.; Orfanoudakis, S.; Boukos, N.; Sakellis, E.; Tsipas, P.; Kalafatis, A. Exploring the Potential of Powder-to-Film Processing for Proof-of-Concept BaZrS3 Perovskite Solar Cells. Mater. Today Commun. 2024, 39, 108608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bystrický, R.; Tiwari, S.K.; Hutár, P.; Sykora, M. Thermal Stability of Chalcogenide Perovskites. Inorg. Chem. 2024, 63, 12826–12838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.A.; Dwivedi, D.K.; Kumar, M. Revolutionizing Energy Band Alignment: Parabolic Grading for High-Performance BaZrS3−x Se x Chalcogenide Perovskite Solar Cells. J. Electron. Mater. 2025, 54, 10085–10099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Gahlawat, D.; Kaur, J.; Rani, U.; Madan, J.; Pandey, R.; Basu, R. Temperature-Induced Variations in the Optoelectronic and Impedance Responses of Bandgap-Engineered BaZrS3 Chalcogenide Perovskite Solar Cells: A Numerical Study. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2025, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, L.; Zhang, D.; Bu, S.; Peng, R.; Wei, Q.; Ge, Z. Synergistic Interface Energy Band Alignment Optimization and Defect Passivation toward Efficient and Simple-structured Perovskite Solar Cell. Adv. Sci. 2020, 7, 1902656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, D.; Peng, J.; Weber, K.; Catchpole, K.R.; White, T.P. Performance Limitations Imposed by the TCO Heterojunction in High Efficiency Perovskite Solar Cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 2022, 15, 5202–5216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salih, M.A.; Mustafa, M.A.; Yousef, B.A.A. Developing Lead-Free Perovskite-Based Solar Cells with Planar Structure in Confined Mode Arrangement Using SCAPS-1D. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samiul Islam, M.; Sobayel, K.; Al-Kahtani, A.; Islam, M.A.; Muhammad, G.; Amin, N.; Shahiduzzaman, M.; Akhtaruzzaman, M. Defect Study and Modelling of SnX3-Based Perovskite Solar Cells with SCAPS-1D. Nanomaterials 2021, 11, 1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zyoud, S.H.; Zyoud, A.H.; Ahmed, N.M.; Abdelkader, A.F.I. Numerical Modelling Analysis for Carrier Concentration Level Optimization of CdTe Heterojunction Thin Film–Based Solar Cell with Different Non–Toxic Metal Chalcogenide Buffer Layers Replacements: Using SCAPS–1D Software. Crystals 2021, 11, 1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.K.; Rubel, M.H.K.; Toki, G.F.I.; Alam, I.; Rahman, M.F.; Bencherif, H. Effect of Various Electron and Hole Transport Layers on the Performance of CsPbI3-Based Perovskite Solar Cells: A Numerical Investigation in DFT, SCAPS-1D, and WxAMPS Frameworks. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 43210–43230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.K.; Mohammed, M.K.A.; Pandey, R.; Arnab, A.A.; Rubel, M.H.K.; Hossain, K.M.; Ali, M.H.; Rahman, M.F.; Bencherif, H.; Madan, J. Numerical Analysis in DFT and SCAPS-1D on the Influence of Different Charge Transport Layers of CsPbBr3 Perovskite Solar Cells. Energy Fuels 2023, 37, 6078–6098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgelman, M.; Nollet, P.; Degrave, S. Modelling Polycrystalline Semiconductor Solar Cells. Thin Solid. Films 2000, 361, 527–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Li, Z.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, H. Theoretical Study and Analysis of CsSnX3 (X = Cl, Br, I) All-Inorganic Perovskite Solar Cells with Different X-Site Elements. Molecules 2024, 29, 2599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.K.; Islam, M.A.; Uddin, M.S.; Paramasivam, P.; Hamid, J.A.; Alshgari, R.A.; Mishra, V.K.; Haldhar, R. Design and Simulation of CsPb. 625Zn. 375IBr2-Based Perovskite Solar Cells with Different Charge Transport Layers for Efficiency Enhancement. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 3957–3979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotfy, L.A.; Abdelfatah, M.; Sharshir, S.W.; El-Naggar, A.A.; Ismail, W.; El-Shaer, A. Numerical Simulation and Optimization of FTO/TiO2/CZTS/CuO/Au Solar Cell Using SCAPS-1D. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 28022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.-H.; Lin, Y.-C. SCAPS-1D Simulation of Various Hole Transport Layers’ Impact on CsPbI2Br Perovskite Solar Cells Under Indoor Low-Light Conditions. Solids 2025, 6, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaykhedkar, N.; Bystrický, R.; Sykora, M.; Bucčko, T. How the Temperature and Composition Govern the Structure and Band Gap of Zr-Based Chalcogenide Perovskites: Insights from ML Accelerated AIMD. Inorg. Chem. 2023, 62, 12480–12492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimul, A.I.; Ghosh, A.; Sarker, S.R.; Alturaifi, H.A. Examining the Contribution of Charge Transport Layers to Boost the Performance over 26% in Sr3PCl3 Absorber-Based Bifacial Perovskite Solar Cells. RSC Adv. 2025, 15, 7663–7681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sławek, A.; Starowicz, Z.; Lipiński, M. The Influence of the Thickness of Compact TiO2 Electron Transport Layer on the Performance of Planar CH3NH3PbI3 Perovskite Solar Cells. Materials 2021, 14, 3295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM G173-03; Standard Tables for Reference Solar Spectral Irradiances: Direct Normal and Hemispherical on a 37° Tilted Surface. ASTM International: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2020.

- Lee, H.-M.; Kim, S.-S.; Kim, H.-K. Artificially MoO3 Graded ITO Anodes for Acidic Buffer Layer Free Organic Photovoltaics. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2016, 364, 340–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, H.; Qin, P.; Ke, W.; Guo, Y.; Dai, X.; Chen, Z.; Wang, H.; Li, B.; Zheng, Q.; Fang, G. Performance Enhancement of Polymer Solar Cells with High Work Function CuS Modified ITO as Anodes. Org. Electron. 2015, 22, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gassenbauer, Y.; Schafranek, R.; Klein, A.; Zafeiratos, S.; Hävecker, M.; Knop-Gericke, A.; Schlögl, R. Surface States, Surface Potentials, and Segregation at Surfaces of Tin-Doped In2O3. Phys. Rev. B 2006, 73, 245312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Bharti, P.; Pradhan, B. Performance Optimization of Efficient PbS Quantum Dots Solar Cells through Numerical Simulation. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 10511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, P.; Lin, Z.; Wang, J.; Yue, M.; Su, J.; Zhang, J.; Chang, J.; Hao, Y. Numerical Simulation of Planar Heterojunction Perovskite Solar Cells Based on SnO2 Electron Transport Layer. ACS Appl. Energy Mater. 2019, 2, 4504–4512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raj, A.; Kumar, M.; Singh, D.V.; Singh, B.; Dwivedi, D.K.; Anshul, A. Physical Parameter Optimization and Band Alignment Approach for Efficiency Improvement in Cs2AgBiBr6 Based Lead-Free Perovskite Solar Cells. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 32868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha, N.; Brunetti, G.; Di Carlo, A.; Ciminelli, C. Efficiency Boost of Perovskite Solar Cell in Homojunction Configuration through Tailored Band Alignment and p–n Doping Profile. J. Phys. Energy 2025, 7, 045009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mahanti, M.; Mukherjee, S.; Shirahata, N.; Ghosh, B. Design and Simulation of Thermally Stable Lead-Free BaHfSe3 Perovskite Solar Cells: Role of Interface Barrier Height and Temperature. Eng 2025, 6, 345. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng6120345

Mahanti M, Mukherjee S, Shirahata N, Ghosh B. Design and Simulation of Thermally Stable Lead-Free BaHfSe3 Perovskite Solar Cells: Role of Interface Barrier Height and Temperature. Eng. 2025; 6(12):345. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng6120345

Chicago/Turabian StyleMahanti, Moumita, Sutirtha Mukherjee, Naoto Shirahata, and Batu Ghosh. 2025. "Design and Simulation of Thermally Stable Lead-Free BaHfSe3 Perovskite Solar Cells: Role of Interface Barrier Height and Temperature" Eng 6, no. 12: 345. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng6120345

APA StyleMahanti, M., Mukherjee, S., Shirahata, N., & Ghosh, B. (2025). Design and Simulation of Thermally Stable Lead-Free BaHfSe3 Perovskite Solar Cells: Role of Interface Barrier Height and Temperature. Eng, 6(12), 345. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng6120345