Engineering Assessment of Small-Scale Cold-Pressing Machines and Systems: Design, Performance, and Sustainability of Screw Press Technologies in Serbia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Serbia’s Small-Scale Oil Mills

2.1. Methodology of Register Search

- Keyword Input—Relevant keywords such as “cold-pressed oil,” “vegetable oils,” “sunflower oil,” “flaxseed oil,” “pumpkin oil,” and “oil production” were entered to identify pertinent entities efficiently.

- Filter Application—The register allows refining the search by facility type (e.g., agricultural farm, processing company), activity type, geographic location (municipality), and production capacity.

- Results Analysis—The obtained list of entities was reviewed in detail, including company or farm name, address, contact details, and specifics of production activities.

- Contact with Local Agricultural Inspectorates—These authorities provide up-to-date information on registered producers within their regions.

- Participation in Agricultural and Food Exhibitions—Trade fairs offered opportunities to engage with current producers, learn about their products, and explore innovations in cold-pressed oil production.

- Monitoring Social Media Channels—Many small and medium producers use platforms like Facebook and Instagram to promote products and communicate directly with customers, providing additional current information.

2.2. Mapping

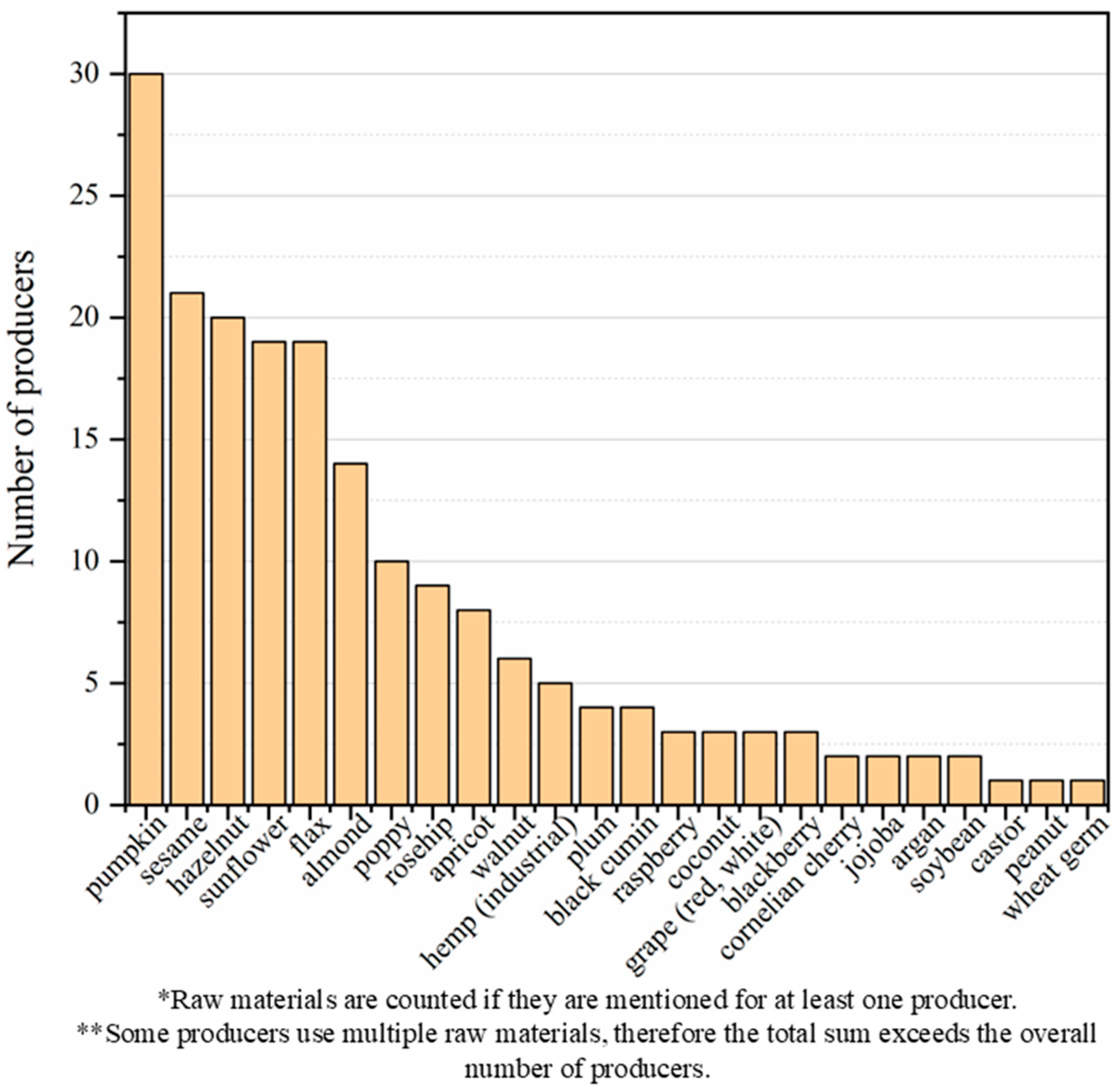

2.3. Raw Materials in Cold-Pressed Oil Production

3. Technology Behind Cold Pressing

- Type and characteristics of the raw material;

- Preparation of the material for pressing: particle size distribution, residual hull content;

- Screw press design and power;

- Pressing parameters: pressure, temperature, process duration, moisture content of feed material, oil content in the cake, etc.

4. Cold Pressing as a Green Technology

5. Market Trends and Potential

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dharmayanti, N.; Ismail, T.; Hanifah, I.A.; Taqi, M. Exploring sustainability management control system and eco-innovation matter sustainable financial performance: The role of supply chain management and digital adaptability in Indonesian context. J. Open Innov. Technol. Mark. Complex. 2023, 9, 100119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puspikaa, W.; Masudina, I.; Saputroa, T.E.; Alfarisi, S.; Restuputri, D.P.; Shariffc, S.R. Sustainable economic production quantity optimization (SEPQ) considering food waste emission and water waste emission using genetic algorithm. Sustain. Oper. Comput. 2025, 6, 140–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Z.; Zhang, C.; Huang, Z.; Jia, L.; Sun, G.; Wang, W. Advancing sustainable and innovative agriculture: An empirical study of farmers’ livelihood risks and the green transformation of food production. J. Innov. Knowl. 2025, 10, 100732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varekar, V.; Yadav, V.; Karmakar, S. Rationalization of water quality monitoring locations under spatiotemporal heterogeneity of diffuse pollution using seasonal export coefficient. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 277, 111342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zalidis, G.; Stamatiadis, S.; Takavakoglou, V.; Eskridge, K.; Misopolinos, N. Impacts of agricultural practices on soil and water quality in the Mediterranean region and proposed assessment methodology. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2002, 88, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, X.; Yang, J.; Song, W. Pollution status of agricultural land in China: Impact of land use and geographical position. Soil Water Res. 2018, 13, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; He, P.; Shen, C.; Wu, Z. Effect of irrigation amount and fertilization on agriculture non-point source pollution in the paddy field. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2019, 26, 10363–10373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burch, D. Greenhouse gas emissions in UK agriculture. Vet. Rec. 2020, 186, 729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Chen, Y.; Yang, K.; Duan, F.; Liu, P.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J. Effects of legume intercropping and nitrogen input on net greenhouse gas balances, intensity, carbon footprint and crop productivity in sweet maize cropland in South China. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 314, 127997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galford, G.L.; Peña, O.; Sullivan, A.K.; Nash, J.; Gurwick, N.; Pirolli, G.; Richards, M.; White, J.; Wollenberg, E. Agricultural development addresses food loss and waste while reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 699, 134318. [Google Scholar]

- Ragini, Y.P.; Karishma, S.; Kamalesh, R.; Saravanan, A.; TajSabreen, B.; Koushik Eswaar, D. Sustainable biorefinery approaches in the valorization of agro-food industrial residues for biofuel production: Economic and future perspectives. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2025, 75, 104239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panić, S.; Đurišić-Mladenović, N.; Petronijević, M.; Stijepović, I.; Milanović, M.; Kozma, G.; Kukovecz, A. Valorization of waste biomass towards biochar production—Characterization and perspectives for sustainable applications in Serbia. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2025, 37, 104043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antràs, P. Global Production: Firms, Contracts, and Trade Structure; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Awokuse, T.; Lim, S.; Santeramo, F.; Steinbach, S. Robust policy frameworks for strengthening the resilience and sustainability of agri-food global value chains. Food Policy 2024, 127, 102714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lužaić, T.; Romanić, R.; Grahovac, N.; Jocić, S.; Cvejić, S.; Hladni, N.; Pezo, L. Prediction of mechanical extraction oil yield of new sunflower hybrids—Artificial neural network model. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2021, 101, 5827–5833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lužaić, T.; Nakov, G.; Kravić, S.; Jocić, S.; Romanić, R. Influence of hull and impurity content in high-oleic sunflower seeds on pressing efficiency and cold-pressed oil yield. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 3012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alessandra, D.; Ramadan, M.F.; Vita Di Stefano, M.L. Cold pressed oils: A green source of specialty oils. Front. Nutr. 2023, II, 1224878. [Google Scholar]

- Rathod, M.L.; Angadi, B.M.; Bhavi, I.G. A review on optimization of process parameters of cold pressed oil extraction for high output and for enhanced quality and retained nutrients. Food Humanit. 2025, 5, 100698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoodi, L.; Gani, A.; Sircar, D.; Jan, K. Quality analysis of walnut oil extracted by cold press and solvent methods for in vitro phytochemicals, antioxidant activity and GCMS analysis. Meas. Food 2025, 18, 100223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tura, M.; Mandrioli, M.; Valli, E.; Gallina Toschi, T. Quality indexes and composition of 13 commercial hemp seed oils. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2023, 117, 105112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sannino, M.; Piccolella, S.; Maresca, G.; Siano, F.; Picariello, G.; Pacifico, S.; Faugno, S. Cooling-assisted cold-pressing: A sustainable approach to high-quality hemp seed oil extraction. Future Foods 2025, 12, 100714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubna, M.; Gull, A.; Masoodi, F.A.; Gani, A.; Nissar, J.; Ahad, T.; Nayik, G.A.; Mukarram, S.A.; Kovács, B.; Prokis, J.; et al. An overview on traditional vs. green technology of extraction methods for producing high quality walnut oil. Agronomy 2022, 12, 2258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ETIP. Bioenergy: Wieselburg, Austria, 2020.Serbia. In Bioenergy Fact Sheet; ETIP Bioenergy: Wieselburg, Austria, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Modica, G.; Pulvirenti, A.; Spina, D.; Bracco, S.; D’Amico, M.; Di Vita, G. Clustering olive oil mills through a spatial and economic GIS-based approach. Clean. Environ. Syst. 2024, 14, 100207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Business Registers Agency of the Republic of Serbia. Central Register of Business Entities. Available online: https://www.apr.gov.rs (accessed on 28 July 2025).

- Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Water Management of the Republic of Serbia. Central Register of Food Business Operators. Available online: https://registarobjekata.minpolj.gov.rs (accessed on 21 July 2025).

- Charron, N.; Lapuente, V.; Bauhr, M. The Geography of Quality of Government in Europe. Subnational Variations in the 2024 European Quality of Government Index and Comparisons with Previous Rounds; Working paper series 2024:2; University of Gothenburg: Göteborg, Sweden, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Izzo, L.; Pacifico, S.; Piccolella, S.; Castaldo, L.; Narváez, A.; Grosso, M.; Ritieni, A. Chemical analysis of minor bioactive components and cannabidiolic acid in commercial hemp seed oil. Molecules 2020, 25, 3710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanić, R. Cold pressed sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) oil. In Cold Pressed Oils: Green Technology, Bioactive Compounds, Functionality, and Applications, 1st ed.; Ramadan, M.F., Ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2020; pp. 197–218. [Google Scholar]

- Oroian, M. A new perspective regarding the adulteration detection of cold-pressed oils. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 198, 116025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Codex Alimentarius. Standard for Named Vegetable Oils Codex Stan 210-1999; Codex Alimentarius: Rome, Italy, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Tsimidou, M.Z.; Mastralexi, A.; Ozdikicierler, O. Cold pressed virgin olive oils. In Cold Pressed Oils: Green Technology, Bioactive Compounds, Functionality, and Applications, 1st ed.; Ramadan, M.F., Ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2020; pp. 547–573. [Google Scholar]

- Grahovac, N.; Lužaić, T.; Živančev, D.; Stojanović, Z.; Đurović, A.; Romanić, R.; Kravić, S.; Miklič, V. Assessing nutritional characteristics and bioactive compound distribution in seeds, oil, and cake from confectionary sunflowers cultivated in Serbia. Foods 2024, 13, 1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lužaić, T.; Kravić, S.; Stojanović, Z.; Grahovac, N.; Jocić, S.; Cvejić, S.; Pezo, L.; Romanić, R. Investigation of oxidative characteristics, fatty acid composition and bioactive compounds content in cold pressed oils of sunflower grown in Serbia and Argentina. Heliyon 2023, 9, e18201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Momot, M.; Stawicka, B.; Szydłowska-Czerniak, A. Physicochemical properties and sensory attributes of cold-pressed camelina oils from the Polish retail market. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 1924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, E.A.E.; Mohammed, D.M.; El Gawad, F.A.; Orabi, M.A.; Gupta, R.K.; Srivastav, P.P. Valorization of food processing waste byproducts for essential oil production and their application in food system. Waste Manag. Bull. 2025, 3, 100200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çakaloğlu, B.; Özyurt, V.H.; Ötleş, S. Cold press in oil extraction. A review. Ukr. Food J. 2018, 7, 640–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhassan, S.H.A.R. Mechanical Expression of Oil from Sesame (Sesamum indicum L.). Ph.D. Thesis, University of Khartoum, Khartoum, Sudan, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Nde, D.B.; Foncha, A.C. Optimization methods for the extraction of vegetable oils: A review. Processes 2020, 8, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piravi-Vanak, Z.; Dadazadeh, A.; Azadmard-Damirchi, S.; Torbati, M.; Martinez, F. The effect of extraction by pressing at different temperatures on sesame oil quality characteristics. Foods 2024, 13, 1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subroto, E.; Manurung, R.; Heeres, H.J.; Broekhuis, A.A. Optimization of mechanical oil extraction from Jatropha curcas L: Kernel using response surface method. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 63, 294–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senphan, T.; Mungmueang, N.; Sriket, C.; Sriket, P.; Sinthusamran, S.; Narkthewan, P. Influence of extraction methods and temperature on hemp seed oil stability: A comprehensive quality assessment. Appl. Food Res. 2025, 5, 100702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heriawan, Y.; Indartono, S.; Ika, A.K. Optimization of mechanical oil extraction process of Nyamplung seeds (Calophyllum inophyllum L.) by flexible single screw extruder. AIP Conf. Proc. 2018, 1984, 020013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crimaldi, M.; Faugno, S.; Sannino, M.; Ardito, L. Optimization of hemp seeds (Canapa Sativa L.) oil mechanical extraction. Chem. Eng. Trans. 2017, 58, 373–378. [Google Scholar]

- Gikuru, M.; Lamech, M.A. Study of yield characteristics during mechanical oil extraction of preheated and ground soybeans. J. Appl. Sci. Res. 2007, 3, 1146–1151. [Google Scholar]

- Dalgıç, L.; Sermet, O.S.; Özkan, G. Farklı kavurma sıcaklıklarının menengiç yağ kalite parametreleri üzerine etkisi. Acad. Food J./Akad. GIDA 2011, 9, 26–36. [Google Scholar]

- Rabadán, A.; Pardo, J.E.; Gómez, R.; Álvarez-Ortí, M. Influence of temperature in the extraction of nut oils by means of screw pressing. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 93, 354–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rombaut, N.; Savoire, R.; Thomasset, B.; Castello, J.; Van Hecke, E.; Lanoisellé, J.L. Optimization of oil yield and oil total phenolic content during grape seed cold screw pressing. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 63, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romanić, R.; Lužaić, T. Dehulling effectiveness of high-oleic and linoleic sunflower oilseeds using air-jet impact dehuller: A comparative study. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 42, e58620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chand, M.; Chopra, R.; Singh, A.; Prabhakar, P.K.; Kamboj, A.; Kumari Singh, P. Enhancement of flaxseed oil quality and yield using freeze-thaw pretreatment optimization: A novel approach. Food Chem. X 2025, 26, 102328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabrenović, B.B.; Dimić, E.B.; Novaković, M.M.; Tešević, V.V.; Basić, Z.N. The most important bioactive components of cold pressed oil from different pumpkin (Cucurbita pepo L.) seeds. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2014, 55, 521–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melo, D.; Álvarez-Ortí, M.; Nunes, M.A.; Costa, A.S.; Machado, S.; Alves, R.C.; Pardo, J.E.; Oliveira, M.B.P. Whole or defatted sesame seeds (Sesamum indicum L.)? The effect of cold pressing on oil and cake quality. Foods 2021, 10, 2108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wandhekar, S.S.; Pawar, V.S.; Shinde, S.T.; Gangakhedka, P.S. Extraction of oil from oilseeds by cold pressing: A review. Indian Food Ind. Mag. 2023, 4, 63–69. [Google Scholar]

- Ramadan, M.F. Healthy blends of high linoleic sunflower oil with selected cold pressed oils: Functionality, stability and antioxidative characteristics. Ind. Crops Prod. 2013, 43, 65–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiralan, M.; Çalik, G.; Kiralan, S.; Ramadan, M.F. Monitoring stability and volatile oxidation compounds of cold-pressed flax seed, grape seed and black cumin seed oils upon photo-oxidation. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2018, 12, 616–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Makawy, A.I.; Ibrahim, F.M.; Mabrouk, D.M.; Ahmed, K.A.; Fawzy Ramadan, M. Effect of antiepileptic drug (Topiramate) and cold pressed ginger oil on testicular genes expression, sexual hormones and histopathological alterations in mice. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 110, 409–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siejak, P.; Neunert, G.; Kaminska, W.; Dembska, A.; Polewski, K.; Siger, A.; Grygier, A.; Tomaszewska-Gras, J. A crude, cold-pressed oil from elderberry (Sambucus nigra L.) seeds: Comprehensive approach to properties and characterization using HPLC, DSC, and multispectroscopic methods. Food Chem. 2025, 464, 141758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, L.; Wu, J.L.; Liu, S.; Wu, W.W.; Liao, L.Y. Effect of alkaline microcrystalline cellulose deacidification on chemical composition, antioxidant activity and volatile compounds of camellia oil. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 186, e115214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Wu, W.; Wu, S.; Wu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liao, L. Effect of different pretreatment techniques on quality characteristics, chemical composition, antioxidant capacity and flavor of cold-pressed rapeseed oil. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 201, 116157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatnagar, A.S.; Gopala Krishna, A.G. Lipid classes and subclasses of cold-pressed and solvent-extracted oils from commercial Indian Niger (Guizotia abyssinica (L.f.) Cass.) seed. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2014, 91, 1205–1216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prescha, A.; Grajzer, M.; Dedyk, M.; Grajeta, H. The antioxidant activity and oxidative stability of cold-pressed oils. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2014, 91, 1291–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, C.Q.; Liu, W.Y.; Xi, W.P.; Cao, D.; Zhang, H.J.; Ding, M.; Chen, L.; Xu, Y.Y.; Huang, K.X. Comparison of volatile compounds of hot—pressed, cold—pressed and solvent—extracted flaxseed oils analyzed by SPME—GC/MS combined with electronic nose: Major volatile scan be used as markers to distinguish differently processed oils. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2015, 117, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belhoussaine, O.; El Kourchi, C.; Mohammed, A.; El Yadini, A.; Ullah, R.; Iqbal, Z.; Goh, K.W.; Gallo, M.; Harhar, H.; Bouyahya, A.; et al. Unveiling the oxidative stability, phytochemical richness, and nutritional integrity of cold-pressed Linum usitatissimum oil under UV exposure. Food Chem. X 2024, 24, 101785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carra, F.; Jaouhari, Y.; Disca, V.; Cecchi, L.; Mulinacci, N.; Giovannelli, L.; Ferreira-Santos, P.; Martakos, I.C.; Thomaidis, N.S.; Gallina, A.; et al. A comparative study of bioactive and volatile components in cold-pressed apricot and peach kernel oils: Implications for nutritional, nutraceuticals and cosmetics functional properties. Food Biosci. 2025, 68, 106585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teh, S.S.; Birch, J. Physicochemical and quality characteristics of cold-pressed hemp, flax, and canola seed oils. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2013, 30, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaseke, T.; Opara, U.L.; Fawole, O.A. Quality and antioxidant properties of cold-pressed oil from blanched and microwave-pretreated pomegranate seed. Foods 2021, 10, 712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadan, M.F. Introduction to cold pressed oils: Green technology, bioactive compounds, functionality, and applications. In Cold Pressed Oils: Green Technology, Bioactive Compounds, Functionality, and Applications; Ramadan, M.F., Ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Kabutey, A.; Herák, D.; Mizera, C. Assessment of quality and efficiency of cold-pressed oil from selected oilseeds. Foods 2023, 12, 3636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brühl, L. Determination of trans fatty acids in cold pressed oils and in dried seeds. Fett/Lipid 1996, 98, 380–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotkiewicz, D.; Konopka, I.; Zylik, S. State of works on the rapeseed oil processing optimization. I. Oil obtaining. Rośliny Oleiste/Oilseed Crops 1999, 20, 151–168. [Google Scholar]

- Ancuța, P.; Sonia, A. Oil press-cakes and meals valorization through circular economy approaches: A review. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 7432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grahovac, N.; Aleksić, M.; Trajkovska, B.; Marjanović Jeromela, A.; Nakov, G. Extraction and valorization of oilseed cakes for value-added food components—A review for a sustainable foodstuff production in a case process approach. Foods 2025, 14, 2244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakač, M.; Marić, A.; Đermanović, B.; Dragojlović, D.; Šarić, B.; Jovanov, P. Characterisation of fibre-rich ingredients obtained from defatted cold-pressed rapeseed cake after protein extraction. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 222, 117671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Z.; Chang, Z.L.; Qin, Z.; Liu, H.M.; Chen, Z.M.; Zhu, X.L.; Wang, Y.G.; Fan, W.; Mei, H.X.; Gu, L.B.; et al. A novel strategy for preparing lignan-rich sesame oil from cold-pressed sesame seed cake by combining enzyme-assisted treatment and subcritical fluid extraction. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 218, 119041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, P.W.; Preskett, D.; Višnjevec, A.M.; Schwarzkopf, M.; Krienke, D.; Charlton, A. Pilot scale extraction of protein from cold and hot-pressed rapeseed cake: Preliminary studies on the effect of upstream mechanical processing. Food Bioprod. Process. 2022, 133, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, D.; Cao, C.; Kong, B.; Sun, F.; Zhang, H.; Liu, Q. Micronized cold-pressed hemp seed cake could potentially replace 50% of the phosphates in frankfurters. Meat Sci. 2022, 189, 108823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waszkowiak, K.; Myszka, K.; Makowska, A.; Barthet, V.J.; Mikołajczak, B.; Zielinska-Dawidziak, M.; Kmiecik, D.; Truszkowska, M. Fermenting of flaxseed cake with Lactiplantibacillus plantarum K06 to increase its application as food ingredient—The effect on changes in protein and phenolic profiles, cyanogenic glycoside degradation, and functional properties. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2025, 217, 117419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadairo, O.S.; Nandasiria, R.; Abbasid, S.; Eskina, N.A.M.; Alukoa, R.E.; Scanlon, M.G. Efficacy of green processing techniques on the recovery of phenolic compounds from canola meal. Appl. Food Res. 2025, 5, 100976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahedifar, A.; Wu, J. Heat-induced pressed gels from canola press cakes: Exploring the impact of starting materials, stirring conditions, and carbohydrase pretreatment. Food Res. Int. 2024, 181, 114111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascual, A.; Pineda-Quiroga, C.; Goiri, I.; Atxaerandio, R.; Ruiz, R.; García-Rodríguez, A. Effects of feeding UFA-rich cold-pressed oilseed cakes and sainfoin on dairy ewes’ milk fatty acid profile and curd sensory properties. Small Rumin. Res. 2019, 175, 96–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vujetić, J.; Fraj, J.; Milinkovic Budinčić, J.; Popović, S.; Đorđević, T.; Stolić, Ž.; Popović, L. Plum protein isolate-caffeic acid conjugate as bioactive emulsifier: Functional properties and bioavailability. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 59, 6183–6193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šuput, D.; Pezo, L.; Rakita, S.; Spasevski, N.; Tomičić, R.; Hromiš, N.; Popović, S. Camelina sativa oilseed cake as a potential source of biopolymer films: A chemometric approach to synthesis, characterization, and optimization. Coatings 2024, 14, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hromiš, N.; Lazić, V.; Popović, S.; Šuput, D.; Bulut, S.; Kravić, S.; Romanić, R. The possible application of edible pumpkin oil cake film as pouches for flaxseed oil protection. Food Chem. 2022, 371, 131197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Östbring, K.; Malmqvist, E.; Nilsson, K.; Rosenlind, I.; Rayner, M. The effects of oil extraction methods on recovery yield and emulsifying properties of proteins from rapeseed meal and press cake. Foods 2020, 9, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ciurko, D.; Czyznikowska, Z.; Kancelista, A.; Łaba, W.; Janek, T. Sustainable production of biosurfactant from agro-industrial oil wastes by Bacillus subtilis and its potential application as antioxidant and ACE inhibitor. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gumul, D.; Kruczek, M.; Szary-Sworst, K.; Sabat, R.; Wywrocka-Gurgul, A. Quality, nutritional composition, and antioxidant potential of muffins enriched with flax cake. Processes 2025, 13, 1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vučurović, D.; Bajić, B.; Trivunović, Z.; Dodić, J.; Zeljko, M.; Jevtić-Mučibabić, R.; Dodić, S. Biotechnological utilization of agro-industrial residues and by-products—Sustainable production of biosurfactants. Foods 2024, 13, 711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandey, A.K.; Thakur, S.; Mehra, R.; Singh Kaler, R.S.; Paul, M.; Kumar, A. Transforming agri-food waste: Innovative pathways toward a zero-waste circular economy. Food Chem. X 2025, 28, 102604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drabinska, N.; Siger, A.; Jelen, H.H. Unravelling the importance of seed roasting for oil quality by the non-targeted volatilomics and targeted metabolomics of cold-pressed false flax (Camelina sativa L.) oil and press cakes. Food Chem. 2024, 458, 140207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Official Gazette of the State Union of Serbia and Montenegro. Regulation on Quality and Other Requirements for Edible Vegetable Oils and Fats, Margarine and Other Fat Spreads, Mayonnaise and Related Products; Official Gazette of the State Union of Serbia and Montenegro: Belgrade, Serbia, 2006; No. 23/2006; Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2013; No. 43/2013. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia. Food Safety Law; Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2009; No. 41/2009 and 17/2019. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia. Regulation on Maximum Concentrations of Certain Contaminants in Food; Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2024; Nos. 73/2024, 90/2024, 47/2025, 61/2025. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia. Regulation on Maximum Residue Levels of Plant Protection Products in Food and Feed; Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2022; Nos. 91/2022, 26/2024. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- European Union. Regulation (EC) No 178/2002 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 28 January 2002 Laying Down the General Principles and Requirements of Food Law, Establishing the European Food Safety Authority and Laying Down Procedures in Matters of Food Safety; Official Journal of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. Regulation (EC) No 852/2004 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2004 on the Hygiene of Foodstuffs; Official Journal of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. Commission Regulation (EC) No 2073/2005 of 15 November 2005 on Microbiological Criteria for Foodstuffs; Official Journal of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- European Union. Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2011 on the Provision of Food Information to Consumers; Official Journal of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Titin, S.; Popović, R.; Matkovski, B. An assessment of Serbian international sunflower oil trade. Econ. Agric. 2025, 72, 759–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, M.; Soza-Parra, J.; Circella, G. The increase in online shopping during COVID-19: Who is responsible, will it last, and what does it mean for cities? Reg. Sci. Policy Pract. 2022, 14, 162–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Wang, S. Influence of food packaging color and food type on consumer purchase intention: The mediating role of perceived fluency. Front. Nutr. 2024, 10, 1344237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ck, V.; Fukey, L.N.; Wankhar, V. Does packaging affect consumer preference during the purchase of chocolate? ECS Trans. 2022, 107, 5827–5838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Samsudin, M.R.; Zou, Y. The impact of visual elements of packaging design on purchase intention: Brand experience as a mediator in the tea bag product category. Behav. Sci. 2025, 15, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia. Monthly Statistical Bulletin 04/2025; Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2025; pp. 22–23. ISSN 2217-2092.

| No. | Original Producer Name | Region Based on NUTS 2024 1,2 | Municipality | Dominant Raw Materials (Seeds, Kernels, Nuts, Fruits, etc.) | Estimated Total Capacity (Tons of Raw Material per Year, Based on 2020–2024), and Category 3 | Potential Applications of Oils |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | “Riznica zdravlja Ripanj” Ltd., Ripanj | RS110 | Voždovac, Belgrade | sunflower, pumpkin, poppy | 12–15 (small) | foods |

| 2 | Jasna Stojanović Entrep. Trade All Nut, Belgrade | RS110 | Stari Grad, Belgrade | apricot, plum, hazelnut, blackberry, raspberry, rosehip | 8–10 (small) | foods, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals |

| 3 | Hyperic Ltd., Belgrade | RS110 | Belgrade | pumpkin, almond, sesame, flax, coconut, black cumin | 10–12 (small) | foods, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals |

| 4 | Probotanic Ltd., Belgrade | RS110 | Belgrade | black cumin, apricot, wheat germ, grape seeds, jojoba, hazelnut, avocado | 8–10 (small) | foods, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals |

| 5 | Kosta Professional Cosmetics, Belgrade | RS110 | Belgrade | rosehip, argan, jojoba, castor | 5–7 (small) | cosmetics, pharmaceuticals |

| 6 | Agrose Ltd., Granice, Mladenovac | RS110 | Mladenovac | rosehip | 2–3 (small) | cosmetics, pharmaceuticals |

| 7 | Agricultural Cooperative Živinostok, Sombor | RS121 | Sombor | flax, pumpkin, sesame, almond, hazelnut | 4–5 (small) | foods, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals |

| 8 | Linum Ltd., Čonoplja | RS121 | Sombor | sunflower, flax, pumpkin, sesame, poppy, walnut, plum, rosehip, cornelian cherry | 20–25 (medium) | foods, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals |

| 9 | PanićAgro17 Ltd., Tovariševo | RS121 | Bačka Palanka | hazelnut | 3–5 (small) | foods, cosmetics |

| 10 | Vojel Ltd., Bač | RS121 | Bač | sunflower, soybean | 250–300 (large) | foods |

| 11 | Bački Dukat Plus Ltd., Odžaci | RS121 | Odžaci | sunflower, pumpkin, flax | 155–160 (large) | foods |

| 12 | Agro jedinstvo Ltd., Karavukovo | RS121 | Odžaci | pumpkin | 12–15 (small) | foods |

| 13 | Agricultural Cooperative Agrokula, Kula | RS121 | Kula | pumpkin | 22–25 (medium) | foods |

| 14 | “Olda Group” Ltd., Seleuš | RS122 | Alibunar | sunflower | 80–90 (medium) | foods |

| 15 | Miroslav Pavela Entrep. Oil Production HC ulje, Padina | RS122 | Pančevo | sunflower, rapeseed, pumpkin, hazelnut, poppy | 5–7 (small) | foods |

| 16 | Agricultural holding Čorogar, Pančevo | RS122 | Pančevo | rapeseed, apricot, flax, hemp (industrial), poppy | 12–15 (small) | foods, pharmaceuticals |

| 17 | Uvita Ltd., Debeljača | RS122 | Kovačica | sunflower, flax, pumpkin, sesame | 10–12 (small) | foods |

| 18 | Miloš Stojkov PR Lala ulje, Crepaja | RS122 | Kovačica | sunflower, hazelnut | 8–10 (small) | foods |

| 19 | Agrolek Ltd., Novi Sad, production facility Bač | RS123 | Novi Sad | sunflower | 450–500 (large) | foods |

| 20 | Petrovec Agrar Ltd., Bački Petrovac | RS123 | Bački Petrovac | sunflower, pumpkin, flax | 300–350 (large) | foods |

| 21 | Progres Ltd., Bački Petrovac | RS123 | Bački Petrovac | sunflower | 250–300 (large) | foods |

| 22 | Pan—Union Oil Ltd., Veternik | RS123 | Novi Sad | pumpkin, flax, sesame, raspberry, blackberry | 45–50 (medium) | foods, cosmetics |

| 23 | Pavle Berbakov Entrep. “Eliks Verde”, Futog | RS123 | Novi Sad | pumpkin, flax, sesame, hazelnut, almond | 12–15 (small) | foods, cosmetics |

| 24 | Agricultural Cooperative Gramina, Novi Sad | RS123 | Novi Sad | hemp (industrial) | 8–10 (small) | pharmaceuticals |

| 25 | Vivaseed Ltd., Novi Sad | RS123 | Novi Sad | pumpkin, flax, sesame, hazelnut, almond | 10–15 (small) | foods, cosmetics |

| 26 | Sanja Arbutina Entrep. Tvoja Pilja, Novi Sad | RS123 | Novi Sad | sunflower, flax, pumpkin, hazelnut, sesame | 3–5 (small) | foods |

| 27 | Biokanna Ltd., Novi Sad | RS123 | Novi Sad | hemp (industrial) | 10–12 (small) | pharmaceuticals |

| 28 | Đorđe Mladenović Entrep. Quantum Satis, Sremska Kamenica | RS123 | Novi Sad | pumpkin, flax, sesame | 23–25 (medium) | foods |

| 29 | Be Green International mj Ltd., Sremska Kamenica | RS123 | Novi Sad | walnut, hazelnut, grape, almond, apricot | 12–15 (small) | cosmetics, pharmaceuticals |

| 30 | Željko Nićin Entrep. Omega Oil, Bečej | RS123 | Bečej | pumpkin, sesame, almond, hazelnut | 15–20 (medium) | foods, cosmetics |

| 31 | Agro-Kirish Ltd., Male Pijace | RS124 | Kanjiža | pumpkin, flax, sesame, hazelnut, almond | 12–15 (small) | foods, cosmetics |

| 32 | Agricultural holding Krstonošić, Kikinda | RS124 | Kikinda | pumpkin, hazelnut, almond, sesame, poppy | 10–12 (small) | foods, cosmetics |

| 33 | Agricultural holding Krnić, Kikinda | RS124 | Kikinda | pumpkin, hazelnut, almond, sesame, poppy | 12–15 (small) | foods, cosmetics |

| 34 | Agricultural holding Stepanov, Kikinda | RS124 | Kikinda | pumpkin, hazelnut, almond, sesame, poppy | 8–10 (small) | foods, cosmetics |

| 35 | Suncokret Ltd., Hajdukovo | RS125 | Subotica | sunflower, flax, pumpkin, sesame, poppy, walnut, plum, rosehip, cornelian cherry | 45–50 (medium) | foods |

| 36 | JS&O Ltd., Novo Miloševo | RS126 | Novi Bečej | pumpkin | 65–70 (medium) | foods |

| 37 | Biberova ulja Ltd., Perlez | RS126 | Zrenjanin | sunflower, flax, pumpkin, sesame | 12–15 (small) | foods |

| 38 | Agricultural Cooperative AlmaRosa, Sremski Karlovci | RS127 | Sremski Karlovci | rosehip | 4–5 (small) | cosmetics, pharmaceuticals |

| 39 | Vitastil Ltd., Erdevik | RS127 | Šid | sunflower | 15–20 (medium) | foods |

| 40 | Vladimir Kovač Entrep. Ekovital, Bikić Do | RS127 | Šid | sunflower, flax, pumpkin, hazelnut, almond, sesame, poppy | 15–20 (medium) | foods, cosmetics |

| 41 | Agricultural holding Đurković, Ruma | RS127 | Ruma | hemp (industrial) | 5–8 (small) | pharmaceuticals |

| 42 | Vinarija Kovačević, Irig | RS127 | Irig | red grape, white grape | 7–8 (small) | foods, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals |

| 43 | Tijana Tomašević Entrep. Srbuška, Zlatibor | RS211 | Zlatibor | rosehip | 1–2 (small) | cosmetics, pharmaceuticals |

| 44 | Agricultural holding Ivan Savić, Užice | RS211 | Užice | pumpkin, hemp (industrial) | 4–5 (small) | foods, pharmaceuticals |

| 45 | Cold-pressed Oil Production Ćićevac | RS214 | Ćićevac | sunflower, soybean, pumpkin, walnut, flax | 10–12 (small) | foods |

| 46 | Ivan Nešić Entrep. AgroPremium, Milatovac, Batočina | RS215 | Batočina | pumpkin, walnut, hazelnut, almond, sesame, poppy | 12–15 (small) | foods, cosmetics |

| 47 | Danijela Martinović Entrep. Aronica, Jagodina | RS215 | Jagodina | hazelnut, apricot, plum, raspberry, blackberry, strawberry | 4–5 (small) | cosmetics, pharmaceuticals |

| 48 | Monastery Studenica, Brezova | RS217 | Kraljevo | pumpkin | 5–6 (small) | foods |

| 49 | Vladejić Ltd., Dušanovac | RS221 | Negotin | hazelnut | 18–20 (medium) | foods, cosmetics |

| 50 | Agricultural holding Živanović, Mali Izvor, production facility Bor | RS223 | Zaječar | pumpkin, walnut, hazelnut, almond, sesame, peanut | 10–15 (small) | foods, cosmetics |

| 51 | Tatjana Ratković Entrep. Master Life Tid, Leskovac | RS224 | Leskovac | flax, sesame, apricot, rosehip, black cumin, coconut, argan | 6–8 (small) | foods, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals |

| 52 | Jovana Milutinović Entrep. Promontis, Vilandrica | RS225 | Gadžin Han | apricot, plum | 3–5 (small) | foods, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals |

| 53 | Beyond Ltd., Niš | RS225 | Niš | pumpkin, sesame, flax, coconut, black cumin | 12–15 (small) | foods, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals |

| 54 | Vladan Stanojević Entrep. Biser, Markovac | RS227 | Velika Plana | sunflower | 450–550 (large) | foods |

| 55 | Pharmanais Ltd., Babušnica | RS228 | Babušnica | sunflower, almond, rosehip, apricot | 12–15 (small) | foods, cosmetics, pharmaceuticals |

| Pressing Material | Nozzle Diameter (mm) | Heating Temperature (°C) | The Frequency of Screw Rotation (Hz) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dehulled sunflower seed | 5–8 | 60–80 | 40–60 |

| Pumpkin seed | 6–8 | 80–100 | 20–30 |

| Sesame | 10–12 | 80–100 | 20–30 |

| Flaxseed | 10–12 | 140–150 | 40–50 |

| Poppy | 6–8 | 60–80 | 40–60 |

| Industrial hemp seed | 6–8 | 80–100 | 40–50 |

| Soybean | 8–12 | 180–200 | 40–50 |

| Caraway, pomegranate seeds | 8–10 | 80–100 | 40–60 |

| Thistle seed | 6–8 | 80–100 | 40–60 |

| Grape seed | 10–12 | 100–120 | 30–40 |

| Walnut, hazelnut kernel | 8–10 | 80–100 | 40–60 |

| Almond, apricot kernel, peanut | 6–8 | 80–100 | 40–60 |

| Model | Country | Seed Capacity | Engine Power | Voltage | Dimensions (L × W × H) | Weight | Producer or Seller | Price | Photo |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KernKraft KK Oil prince F Universal | Germany | up to 15 kg/h | 2.2 kW | 400 V|3-phase | 950 × 465 × 510 mm | 80 kg | https://cms.oelpresse.de/ (accessed on 23 August 2025.) | 4300 € |  |

| KernKraft KK 20 F Universal | Germany | up to 20 kg/h | 2.2 kW | 230 V|1-phase 400 V|3-phase 230 V|3-phase | 480 × 480 × 620 mm | 135 kg | https://cms.oelpresse.de/ (accessed on 24 August 2025.) | 5900 € |  |

| KernKraft KK 40 F Universal | Germany | up to 40 kg/h | 3 kW | 230 V|1-phase 400 V|3-phase 230 V|3-phase | 550 × 475 × 630 mm | 200 kg | https://cms.oelpresse.de/ (accessed on 23 August 2025.) | 7900 € |  |

| Reinartz AP 08 | Germany | 30–40 kg/h | 4 kW | / | 1800 × 500 × 800 mm | 400 kg | https://www.reinartz.de/ (accessed on 23 August 2025.) | 6100 € |  |

| Keller KEK-P0020 screw press | Germany | 20 kg/h | 1.5 kW | / | 1500 × 810 × 700 mm | 152 kg | https://www.keller-kek.de/ (accessed on 23 August 2025.) | 3100 € |  |

| AgOil M70 Oil Press | USA | 12.5–24 kg/h | / | 220 V | 2235 × 1499 × 1118 inches | 80 kg | http://www.agoilpress.com/images/dealers/-OilPress-Brochure.pdf (accessed on 24 August 2025.) | 8450 € |  |

| YZYX70 | China | 50 kg/h | 4 kW | 380 V | 1090 × 405 × 806 mm | 195 kg | https://www.honest-industrial.com/ (accessed on 23 August 2025.) | 1250 € |  |

| YZYX90 | China | 125 kg/h | 5.5 kw | 380 V | 1200 × 550 × 1000 mm | 285 kg | https://www.honest-industrial.com/ (accessed on 23 August 2025.) | 1400 € |  |

| Mikron SZR | Serbia | 25–30 kg/h | 2.2 kW | 380 V|3-phase | 1300 × 800 × 1200 mm | 105 kg | https://mikronszr.com/?page_id=33&lang=sr (accessed on 25 August 2025.) | 2900 € |  |

| Elekro motor—Šimon, SPU-40 | Serbia | 10–40 kg | 2.2 kW | 380 V|3-phase | 1012 × 559 × 824 mm | 95 kg | https://elektromotor-simon.com/ (accessed on 25 August 2025.) | 2700 € |  |

| Raw Material | Functional Component | Content | Application | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rapeseed | fiber | 38.0 ± 1.22% | functional components for enriching food products | [73] |

| sesame | lignan | 1.26–1.35% | lignan-rich sesame oil | [74] |

| rapeseed | proteins | 7.5–27.5% | functional food ingredients | [75] |

| hemp seed | phosphates | 5.53 ± 0.67 mg/g on dry matter | frankfurter production | [76] |

| flaxseed | protein | 36.18% | fermenting with Lactiplantibacillus plantarum to increase its application as food ingredient | [77] |

| phenolic components | 3.56 ± 0.09 mg GAE/g | |||

| canola | phenolic compounds | 3.8–5 mg GAE/g | for food applications | [78] |

| canola | protein | 37.83 ± 2.47% on dry matter | heat-induced pressed gels for product alone and for a micro-structured protein extract | [79] |

| sunflower | unsaturated fatty acids | 42.49% | ewe feeding, for better milk fatty acid profile and curd sensory properties | [80] |

| rapeseed | 36.16% | |||

| plum | protein | 93.61 ± 0.21% in protein isolate | with addition of caffeic acid for production of bioactive emulsifier | [81] |

| camelina | protein | / | biopolymer films | [82] |

| hull-less pumpkin | protein | / | pouches for flaxseed oil protection | [83] |

| rapeseed | protein | 65 ± 2% in sediment on dry matter | emulsifier production | [84] |

| sunflower | whole cake | / | fermenting with Bacillus subtilis for Biosurfactant (Surfactin) production | [85] |

| rapeseed | ||||

| flaxseed | polyphenols | 14.76 ± 0.37 mg catechin/g on dry matter | production of muffins enriched with flax cake | [86] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Romanić, R.; Lužaić, T. Engineering Assessment of Small-Scale Cold-Pressing Machines and Systems: Design, Performance, and Sustainability of Screw Press Technologies in Serbia. Eng 2025, 6, 347. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng6120347

Romanić R, Lužaić T. Engineering Assessment of Small-Scale Cold-Pressing Machines and Systems: Design, Performance, and Sustainability of Screw Press Technologies in Serbia. Eng. 2025; 6(12):347. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng6120347

Chicago/Turabian StyleRomanić, Ranko, and Tanja Lužaić. 2025. "Engineering Assessment of Small-Scale Cold-Pressing Machines and Systems: Design, Performance, and Sustainability of Screw Press Technologies in Serbia" Eng 6, no. 12: 347. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng6120347

APA StyleRomanić, R., & Lužaić, T. (2025). Engineering Assessment of Small-Scale Cold-Pressing Machines and Systems: Design, Performance, and Sustainability of Screw Press Technologies in Serbia. Eng, 6(12), 347. https://doi.org/10.3390/eng6120347