1. Introduction

Humanoid robots have emerged as versatile platforms for applications ranging from disaster response to service and industrial tasks. Among the many challenges they face, bipedal locomotion remains particularly demanding due to its high-dimensional, underactuated dynamics and tight stability margins. Classical walking paradigms include passive walkers, which exploit gravity and mechanical design to achieve a low-energy gait at the cost of limited controllability [

1]. These semi-passive schemes combine passive dynamics with minimal actuation [

2], and fully active approaches relying on servo-driven joints [

3]. Of these, active walking has demonstrated the best performance and flexibility on real humanoids such as Atlas and Valkyrie [

4,

5].

To enhance these methods, model-based controllers—e.g., preview-control of the Zero-Moment-Point (ZMP) [

6], Model Predictive Control (MPC) on simplified pendulum models [

7], and capture-point feedback [

8]—have achieved robust walking even on uneven terrain. Bestmann and Zhang (2022) proposed an open-source omnidirectional gait generator with automated parameter tuning, demonstrating stable multi-direction walking on several humanoid platforms [

9]. Wang et al. (2022) leveraged a decoupled actuated SLIP model and high-frequency MPC to traverse challenging ground with minimal perception [

7]. Hu et al. (2023) provide a comprehensive survey of modern bipedal control methods, highlighting the enduring utility of reduced-order, model-predictive strategies alongside emerging learning-based techniques [

10]. While these model-based strategies provide robust balance and foot-placement control, a complementary line of work seeks to automatically discover effective walking policies by optimizing over high-dimensional parameter spaces. We now turn to evolutionary approaches that remove much of the manual tuning burden.

Evolutionary algorithms, particularly Genetic Algorithms (GAs), offer a complementary route by automatically discovering gait parameters in large, nonlinear search spaces without explicit dynamic models [

11]. Szabó (2023) showed that a GA can evolve a humanoid’s joint trajectories to achieve both stable walking and autonomous fall recovery, drawing inspiration from infant learning [

12]. Gupta et al. (2024) applied a multi-objective GA (NSGA-II) on an NAO robot to balance the energy efficiency and stability margin, extracting Pareto-optimal gait sets for hardware validation [

13]. More recently, Chagas et al. (2024) combined a screw-theory kinematic model with a GA to tune swing-leg trajectories and torso pitch, converging within 100 generations and successfully transferring the gait to a 14-DoF (Degrees of Freedom) humanoid for 2 m open-loop trials [

14]. The effectiveness of such search-based optimization hinges on a compact and accurate kinematic representation: if forward and inverse kinematics are costly or ill-conditioned, exploration slows and solutions degrade. This motivates our use of a screw-theoretic formulation.

Accurate kinematic modeling is essential for both model-based and evolutionary schemes. Screw theory offers a compact alternative to the classic Denavit–Hartenberg (DH) method, reducing the parameter count and simplifying the construction of Homogeneous Transformation Matrices [

15,

16]. Zhong et al. (2023) fused screw and DH formulations to derive real-time inverse kinematics for a 7-DoF humanoid arm, improving end-effector accuracy by over 70 % in hardware tests [

17]. Sun et al. (2023) used Product-of-Exponential (POE) screw modeling to plan stable gaits for a novel hybrid biped mechanism, validating the approach in simulation [

18].

Finally, real-world validation remains the gold standard. Radosavovic et al. (2024) demonstrated zero-shot sim-to-real walking with a transformer-based policy on a full-size humanoid, achieving robust locomotion over outdoor terrain without online retraining [

19]. Our work shows that these advances underline the need for hybrid frameworks that couple accurate, screw-theoretic kinematics with automated optimization to produce stable, efficient humanoid gaits deployable on real hardware. Building on these trends and gaps, our contributions are summarized below.

The main contributions of this work are as follows: (i) the development of a compact screw-theoretic kinematic formulation tailored for humanoid gait generation; (ii) the integration of this formulation with a multi-objective genetic algorithm to automate gait tuning; and (iii) the validation of the proposed method in both simulation and real hardware, showing consistent walking performance. These contributions address the gap between purely model-based strategies and purely learning-based optimization by offering a hybrid framework that balances accuracy, computational efficiency, and applicability to real platforms.

This paper presents such a framework. In

Section 2, we derive our screw-theory kinematic model construction. In

Section 3, we detail the multi-objective GA for tuning leg-swing speeds and torso angle. In

Section 4, we describe our simulation and 14-DoF hardware setup. In

Section 5, we report convergence analyses, correlation metrics, and sim-to-real trials. In

Section 6, we discuss insights and limitations, and in

Section 7, we conclude with future directions.

2. Mathematical Formulation

2.1. The Kinematic Model of the Robot

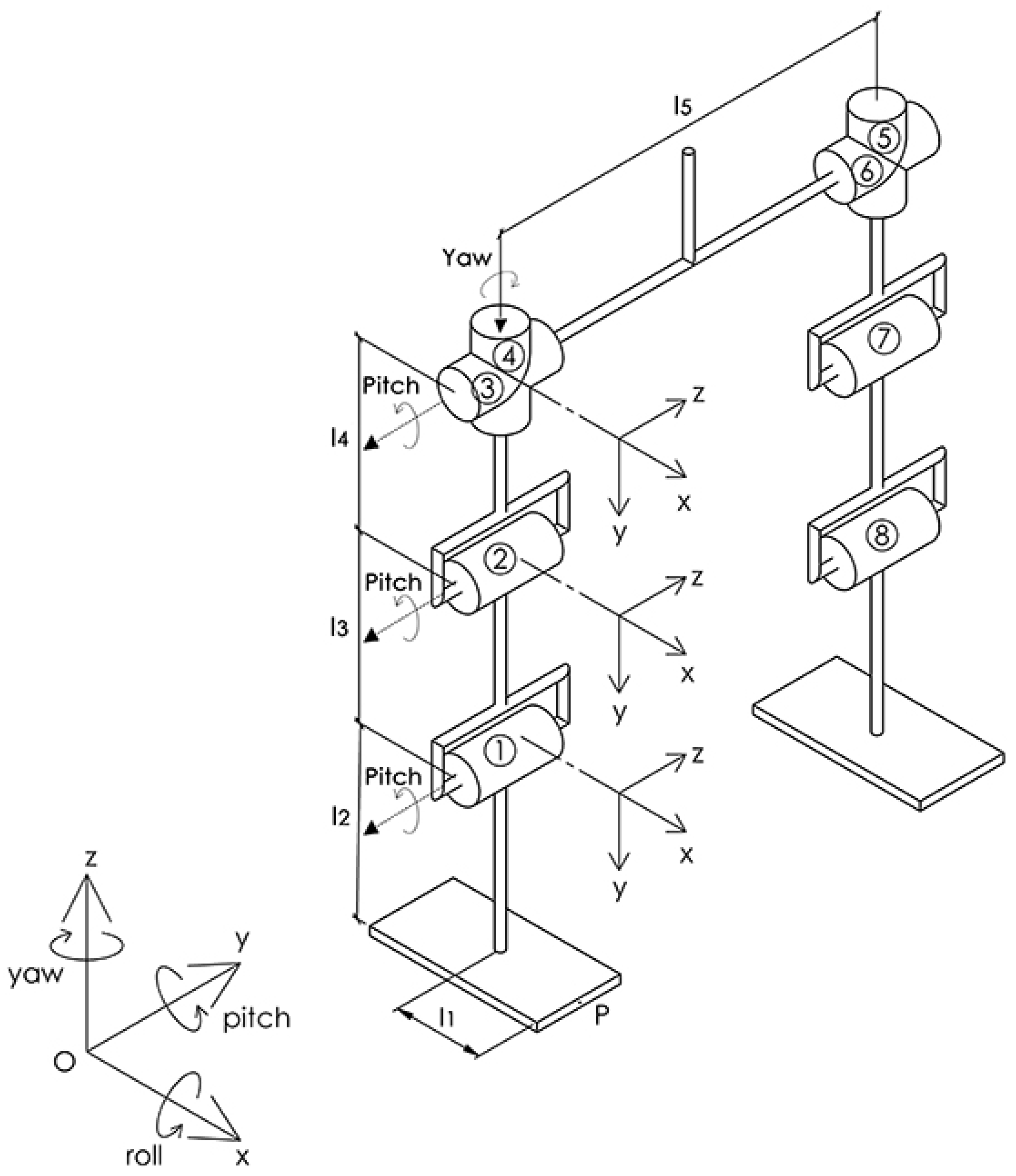

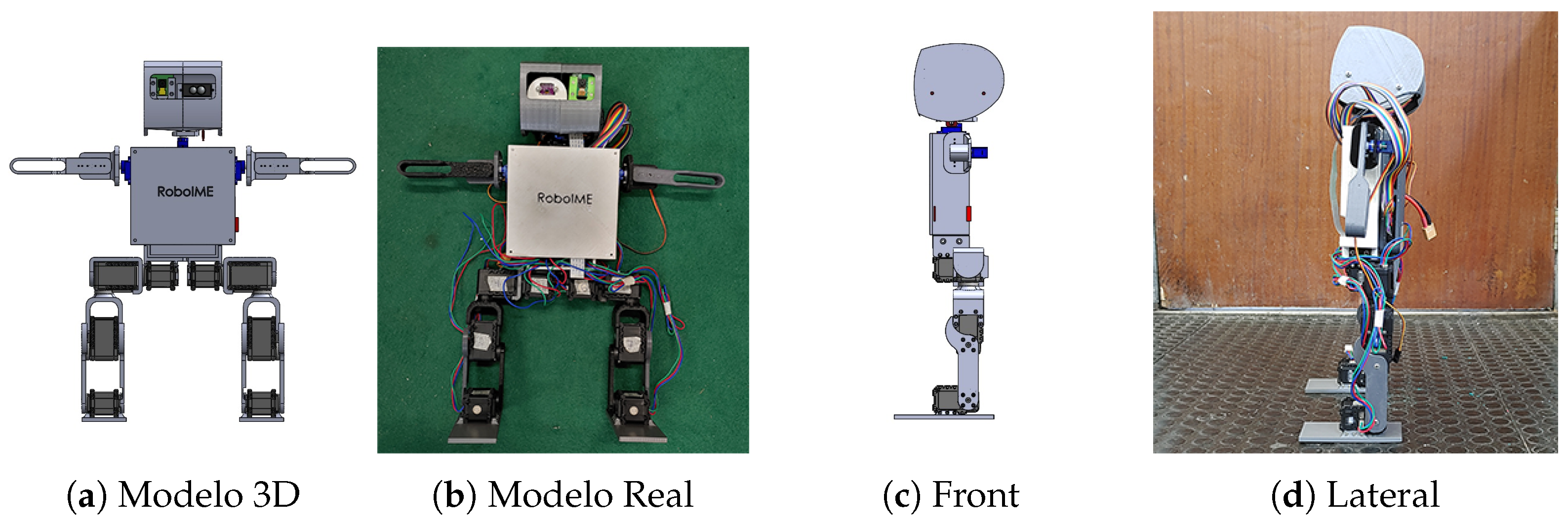

Figure 1 shows the kinematic structure of the lower limbs of the humanoid. The legs of the robot are composed of revolution joints with four degrees of freedom each, being 2 DoF on the hip and thigh, 1 DoF on the knee, and 1 DoF on the ankle.

2.2. Formulating the Kinematic Equations

Before starting the formulation of the kinematic equations, it is necessary to define the movement constraints and plan the motion of the joints. The initial conditions for obtaining the kinematics, in this work, are as follows: the upper part of the body mass is concentrated in the center of the robot; the Center of Mass (CoM) of the robot is in a fixed-height plane; there is enough friction for the robot not to slip; the gait happens in one single direction; there is no interference from external forces, such as collisions with other bodies; the joints are collision-free and the contact surface is flat.

Having defined the restrictions, the second step is to determine how the movement will be performed. That said, the planning of the movement happens as follows: initially, one of the legs of the robot is fixed and serves as a reference axis for the leg that is moving. The objective is to calculate the angular variation and the joint velocity of the moving leg from the speeds of the final effector (point p in

Figure 1), which is the foot of the robot. After the leg that started the movement lands on the ground, it becomes the reference and the leg that was at rest starts to move. The process is repeated until it finds a stop condition.

The extraction of the direct kinematic follows the sequence as indicated by the following procedure in Algorithm 1:

| Algorithm 1: Forward kinematics via SSDM (Successive Screw Displacement Method) |

- 1:

procedure Kinematic(Robot model) - 2:

Choose a fixed coordinate system; - 3:

Identify bodies, joints and axes; - 4:

Identify the screw parameters; - 5:

Build the Homogeneous Transformation Matrix (HTM) of each joint, as well as the matrix with the reference location of the end-effector; - 6:

Apply the Successive Screw Displacement Method (SSDM) with the HTM of each joint [ 15]; and - 7:

Multiply the result of the SSDM with the matrix of the end-effector. - 8:

end procedure

|

2.3. Choose a Fixed Coordinate System

In

Figure 1, the

fixed coordinate system is centered on the origin of the foot of the robot. The

z-axis points to the head of the robot, the

x-axis is in the direction of the sagittal plane, and the

y-axis is towards the frontal plane.

2.4. Identify Bodies, Joints and Axes

The joints of the robot are indicated by numbers 1 to 8. The numbers 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively, indicate the joints of the ankle, knee, hip rotation, and thigh flexion of the right leg. The joints 8, 7, 6, and 5 represent the joints of the ankle, knee, hip rotation, and flexion of the left leg. It is possible to identify the orientation of the joint axes through the Fleming Rule.

2.5. Identify the Screw Parameters

Table 1 shows the indication of the screw parameters

,

,

and the axes distances to the referred joints indicated by

,

and

, in relation to the fixed coordinate system.

2.6. Build the HTM of Each Joint, as Well as the Matrix with the Reference Location of the End-Effector

Equation (

1) shows the generic structure for obtaining HTM

for a joint

i, [

20].

The translations vector

is given by Equation (

2),

The translation vector

represents the generic displacement associated with joint

i. In the general screw-theoretic formulation, this term accounts for both revolute and prismatic joints. However, since our humanoid robot contains only revolute joints, all prismatic contributions vanish, and

simplifies accordingly. Thus, in this work,

reflects only the geometric offsets derived from the screw parameters and the reference configuration of revolute joints, with no translational degrees of freedom. We define

as

where

Thus,

Remark 1. The terms , and refer to prismatic joints; as all joints are of revolution, they are eliminated from Equation (4). The final transformation is given by Equation (

5), where

corresponds to the position of the foot of the robot.

2.7. Apply the SSDM with the HTM of Each Joint

The SSDM [

15] consists of the multiplication of HTM matrices related to screws that compose a given kinematic chain. Equation (

6) shows the application of the SSDM for each joint of the robot, that is,

where the index

i corresponds to the joints of the humanoid leg model (see

Table 1). The formulation, however, is general and can be extended to robots with a different number of joints by adjusting the product limits accordingly.

2.8. Multiply the SSDM Result by the Matrix of End-Effector

The final transformation is obtained by multiplying the matrix

by the matrix of final transformation, see Equation (

7),

where

From here we obtain the following angles

and

The angles represent the

foot/end-effector frame with respect to the fixed world frame

(

Section 2.3):

= roll about the

x-axis,

= pitch about the

y-axis, and

= yaw about the

z-axis. Angles are in radians and follow the right-hand rule. Equations (

9)–(

11) implement this extraction from the rotation part of

.

2.9. Inverse Kinematics

In inverse kinematics, the objective is to find the equations that make it possible to relate the linear and angular speeds of the end-effector, that is, of the foot of the robot, as a function of the joint speeds themselves.

Let

be the vector that contains the angular and linear speeds, see Equation (

12).

where

represents the angular velocities of the end-effector, while

denotes the linear velocities of the foot.

The joint speed vector

is represented by Equation (

13).

For an

n-joint chain,

stacks the

angular speeds of the revolute joints (units: rad/s). In our leg model (

Table 1),

and all joints are revolute; therefore,

contains no translational rates.

The relation between

and

described in [

15] is given by Equation (

14).

where

is the Jacobian described by Equation (

15)

where

and

denote the angular and linear speeds, respectively. Knowing the speeds of the tool, the objective is to find the speeds of the joints, which can be obtained by applying Equation (

16).

2.10. Trajectory Model of the Robot Foot

Assuming that the foot of the humanoid performs an elliptical movement, the velocities vector

is given by Equation (

17),

where

is the horizontal linear speed and

is the linear vertical speed of the foot of the robot, defined as follows:

and

where

is the engine rotation frequency,

is given by Equation (

20),

and

are input parameters for speed adjustment, and

is the speed of the gait.

2.11. Jacobian Matrix

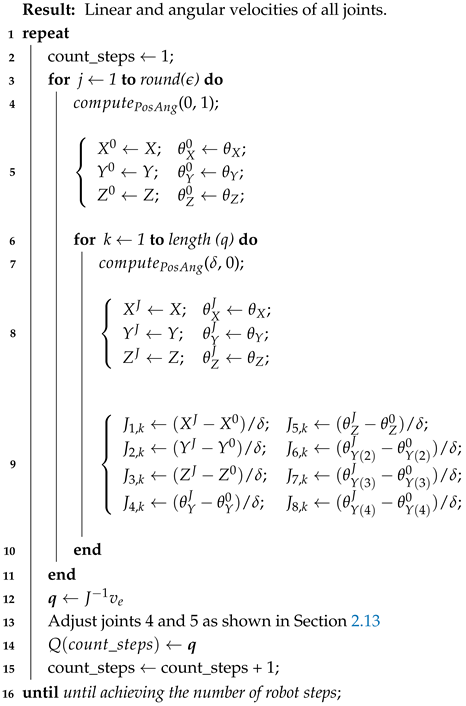

Algorithm 2, procedure Heli8m(

), takes ang_tr, axf, azf, count_steps, and the velocity vector

as parameters. On line 2, count_step receives 1, and the program begins execution. In line 3, the

program executes a loop that varies from 1 to

. In line 4, the system calls Algorithm 3, procedure

. This procedure obtains the

and

z position values, and the

,

, and

angle values of the joints. The parameter

serves to help calculate the partial derivatives of the Jacobian matrix, and the parameter

a serves to adjust the indexes of the position and velocity vectors. Line 9 shows the obtainment of the Jacobian matrix by applying the definition of the derivative. In line 12, the vector q receives the product of the inverse Jacobian matrix by the velocity vector of the final effector. Next, there is the adjustment of joints 4 and 5, which rotate the hip. In line 14, the system updates the matrix Q, which contains all the information about the speed of the joints during the steps. Finally, the procedure updates the value of count_steps in line 15 and it checks if the program has reached the final; if so, the system stops; if it does not, it reruns the loop from line 3.

| Algorithm 2: Heli8m() |

![Automation 06 00080 i001 Automation 06 00080 i001]() |

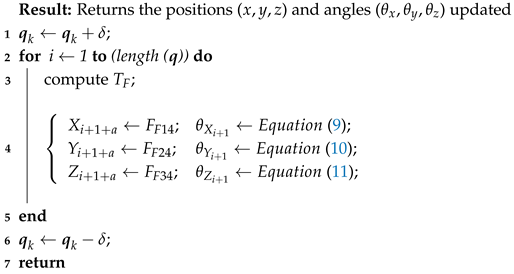

| Algorithm 3: (, a) |

![Automation 06 00080 i002 Automation 06 00080 i002]() |

2.12. Robot Memory File

Algorithm 4, procedure MemoryGen( ), is responsible for generating the memory of the robot. Initially, it calls Algorithm 2 and then in line 2, it traverses a

for ranging from 2 to the end of

matrix. In line 3, the procedure loops through vector

, which calculates the value of motor rotation frequency (

), line 4. In line 5, the program checks if the value found exceeds the frequency of motors mf, and if so,

receives the value of mf. If the

value is less than the lower limit that the engine supports,

receives (−1) mf, which is the minimum mf value. In line 11, the program checks if the

value is negative; if so,

receives the

. Finally, the system generates the

memory matrix that contains the values of the angular positions and rotation frequency of the motors for each robot joint during the steps.

| Algorithm 4: MemoryGen( ) |

![Automation 06 00080 i003 Automation 06 00080 i003]() |

2.13. Hip Rotation

The hip rotation is an input parameter, and this allows you to simplify two degrees of freedom to obtain the reversible kinematics and obtain a Jacobian matrix. This parameter variation is made by adjusting the angles of joints 4 and 5 and follows Equation (

21).

where

indicates the step number of the robot.

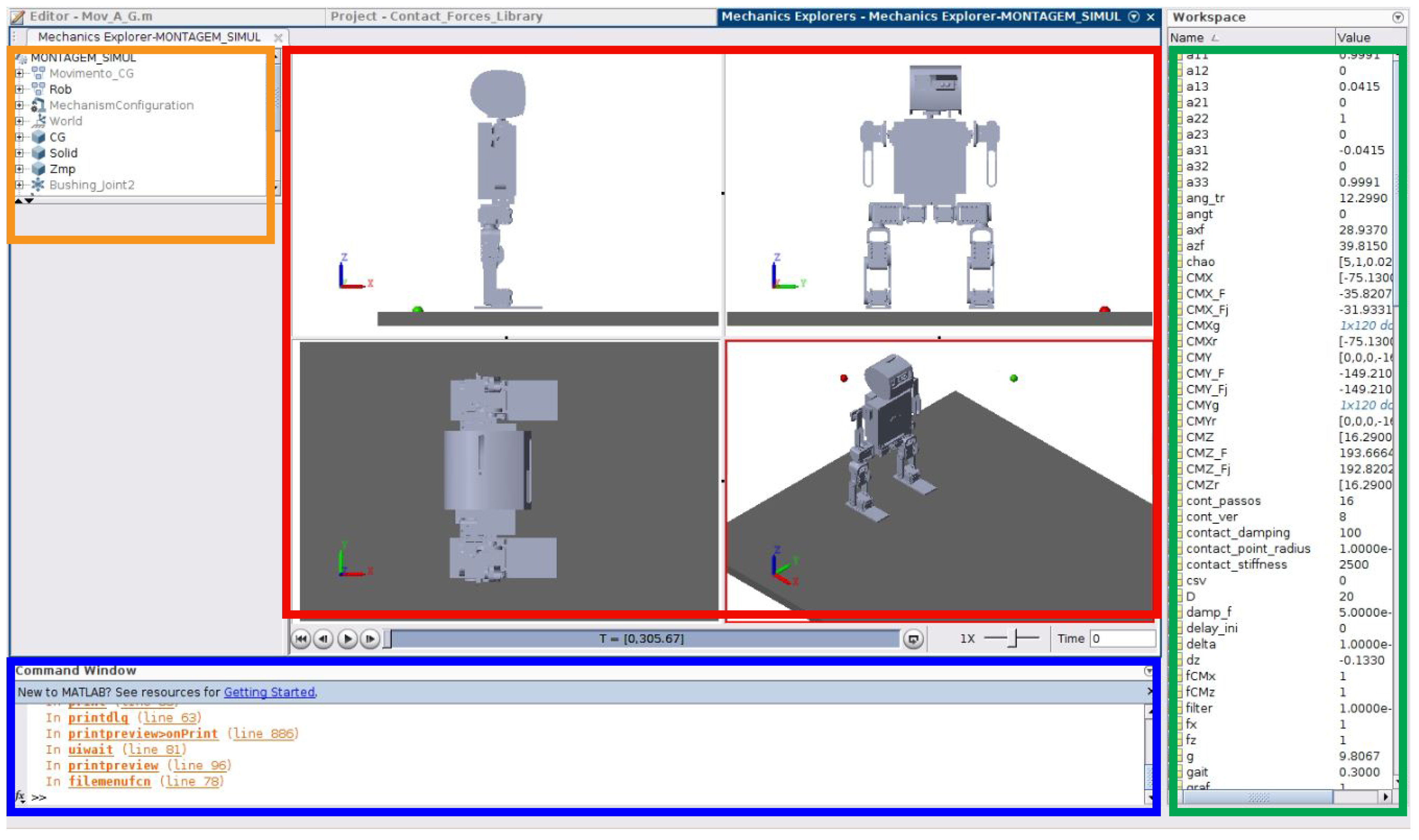

3. The Algorithm

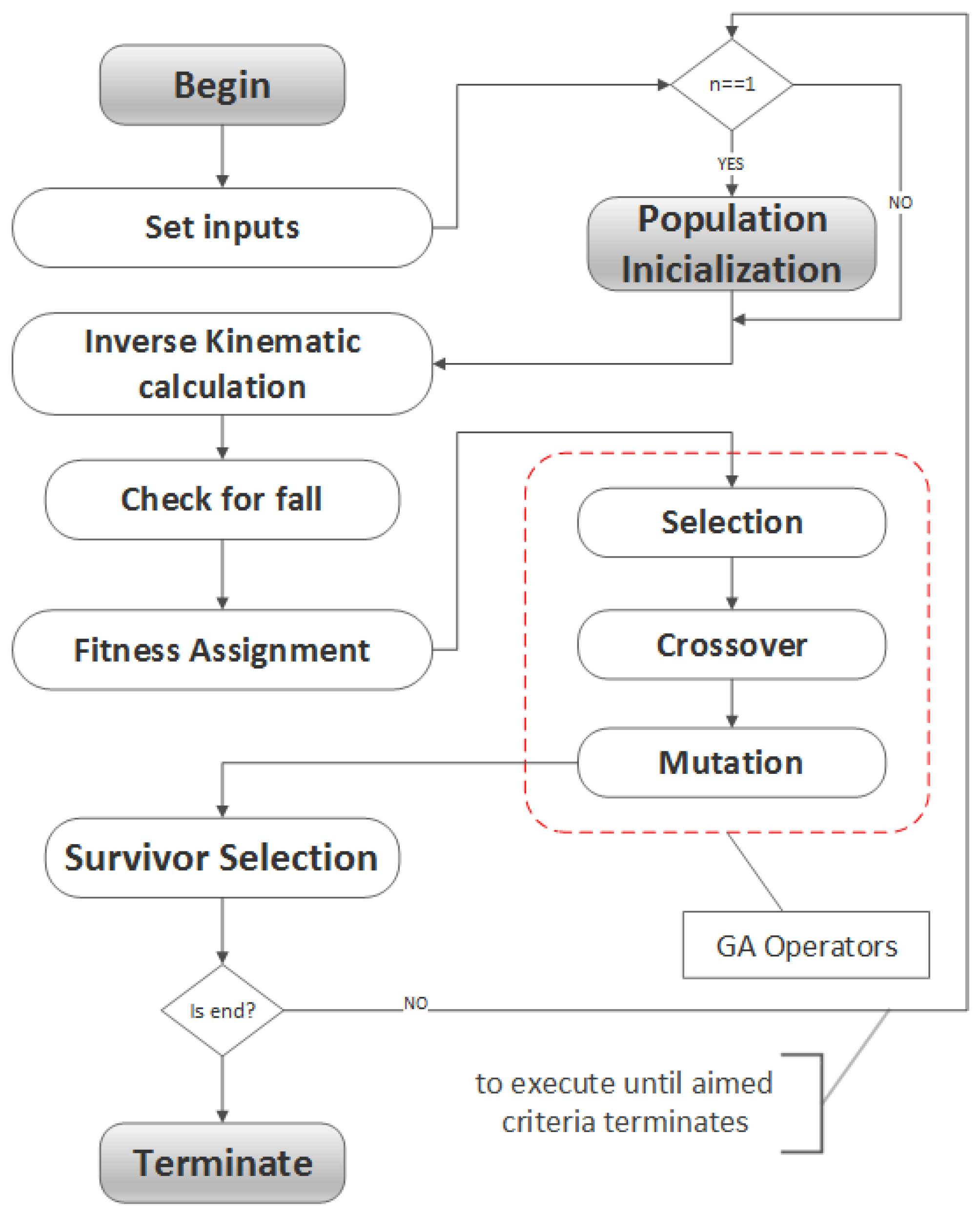

Figure 2 shows the flowchart of the proposed algorithm. Initially, the system is configured as indicated by the Set Inputs block. Then, the system checks whether it is an initial execution or not; if it is the first execution, the system loads the initial population and calculates the inverse kinematics. After the calculus, the system checks whether the parameters are suitable or not, in other words, whether the robot has fallen or not. With the information from the kinematic calculation and the platform behavior, the system calculates the value for the fitness function. The genetic algorithm parameters are adjusted, which means the surviving individuals are used as an entrance for a new generation. The completion of the process occurs when the number of predefined generations is reached.

The GA Encoding

This work uses the real value representation for genes because it is a continuous distribution rather than a discrete one. Therefore, consider the vector

with

to be the genotype for a solution with

k genes.

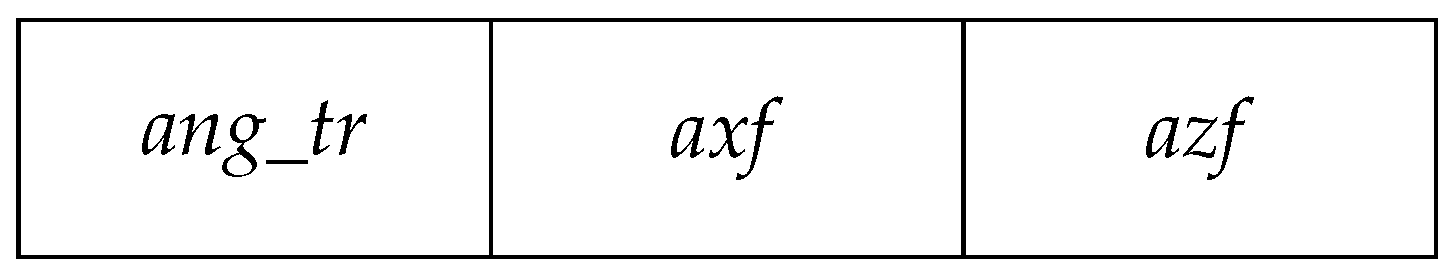

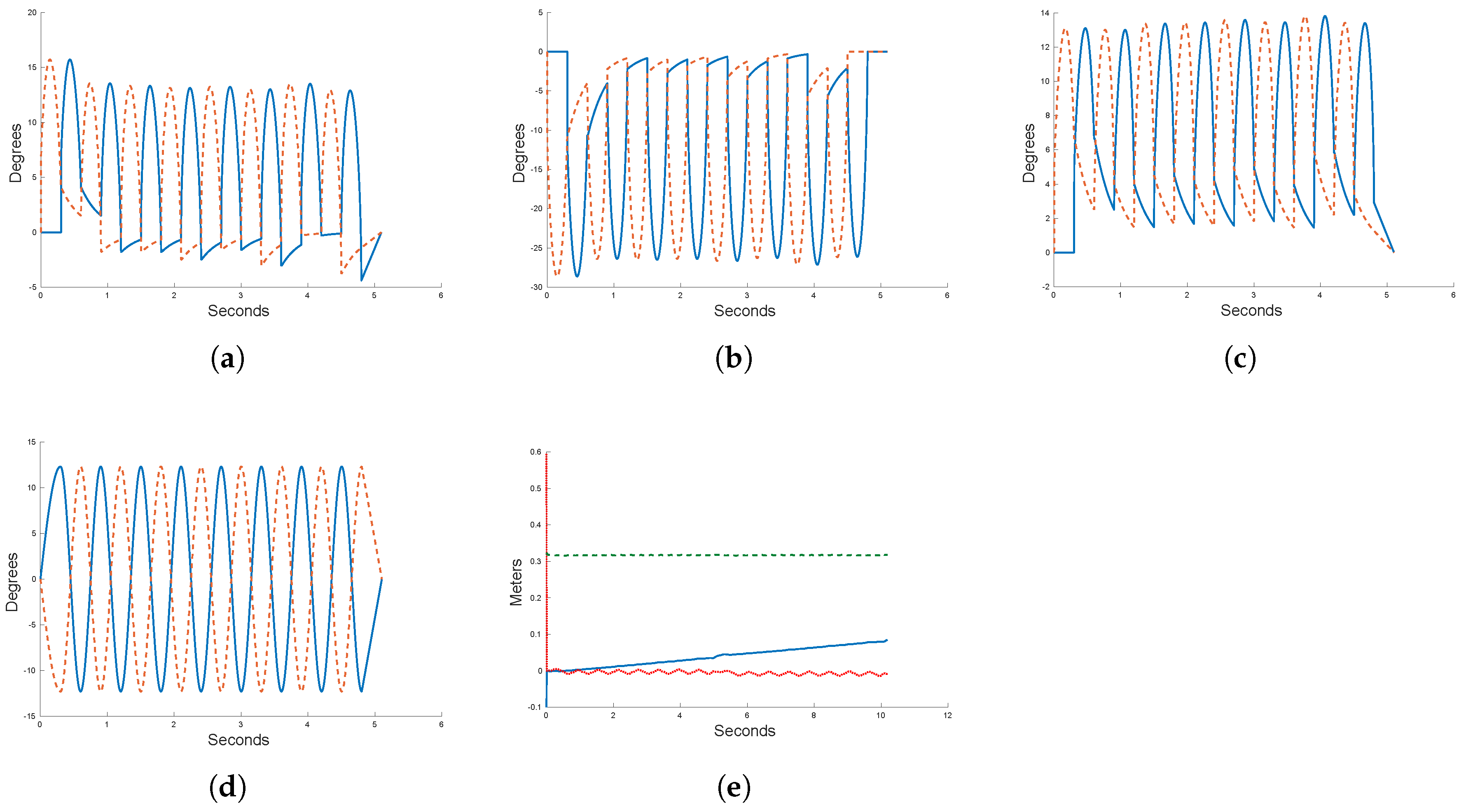

Figure 3 illustrates a chromosome with three genes, where the genes at locus 1, 2, and 3 represent the robot trunk tilt angle, robot foot horizontal velocity, and robot foot vertical velocity, respectively.

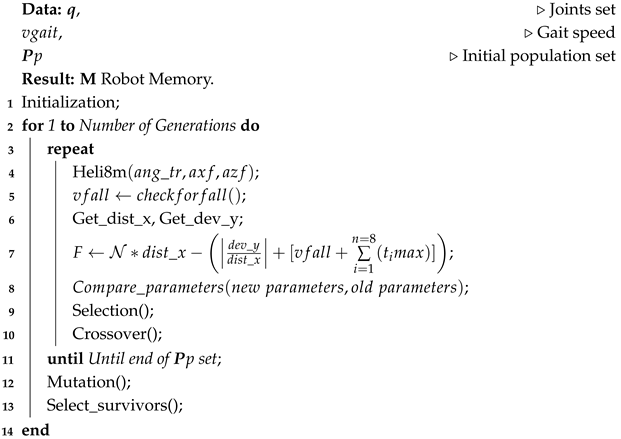

The pseudocode for Algorithm 5 takes the set of joints of the robot as input, the walking speed and the initial population, being formed by the set containing the inclination of the trunk and the foot of the robot horizontal and vertical speeds. The output is a list containing the axf, azf, and ang_tr optimized values for each generation.

In line 1, the system initializes all variables and proceeds to line 3, where it enters a repetition structure that will be executed until it reaches the total number of predefined generations. In line 4, the program calls the Heli8m( ) function, which is responsible for solving the inverse kinematics of the humanoid. In line 5, the checkforfall() function returns to fall condition, if the robot falls, the

vfall variable receives 1 as the value, otherwise, it receives 0, see Equation (

22),

In line 6, Get_distx and Get_devy are responsible for accessing the displacement values in the sagittal plane and the lateral deviation suffered by the robot during the step. Line 7 shows the calculation of the fitness function

F, which is composed of two parts, reinforcement and penalty. The reinforcement part consists of the product between the

N factor and the distance roamed in the sagittal plane. The

N factor is an estimate given by Equation (

23).

N assumes the maximum value that can be reached by the penalty; this way, the system ensures that any positive displacement will be rewarded. Equation (

24) shows the relation between the deviation suffered by the robot due to its displacement. Equation (

25) portrays the penalty ratio, in case the servomechanisms torques exceed the maximum allowed. In determining the maximum value, where

indicates the

N floor and

represents the maximum torque

of the

servomechanism associated with the joint

i, we have

where

and

| Algorithm 5: () |

![Automation 06 00080 i004 Automation 06 00080 i004]() |

In line 8, the function Compares_Parameters checks whether the new parameter is better than the previous one. If better, the algorithm keeps the new value, otherwise, the function discards it. In line 9, the algorithm calls the Selection( ) function through the roulette method. Then, the system executes the Crossover( ) function. After roaming through the entire population, the chromosomes undergo mutation. In line 14, the Select_survivors( ) function will contain the new generation individuals. The system continues the execution until it reaches the number of generations predefined at the beginning of the program.

Algorithm 6, procedure Crossover( ), describes the sequence of steps for the achievement of crossover between chromosomes. The crossover is made between the

axf,

azf and

ang_tr genes. Initially, the procedure identifies the chromosome with highest aptitude

and the lowest aptitude

—both are removed from the potential partners list. Then the system seeks a random

partner and matches it with the best element. The result of the crossover

substitutes the weakest chromosome.

| Algorithm 6: Crossover( ) |

Result: - 1

Identifies the chromosome with the highest fitness

- 2

Identifies the chromosome with the lowest fitness - 3

Removes and from the suitors list - 4

Identifies a potential partner among the rest of the population - 5

Returns with to the list of population - 6

The new chromosome is given by: .

|

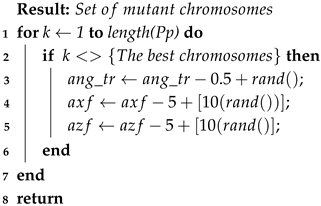

Algorithm 7, procedure Mutation( ), shows the function that realizes the chromosome mutation. The entire population set is covered; the best individuals are excluded from the process, characterizing the process of elitism. The mutation rate is given by Equation (

26), where

is the number of elements belonging to the set of the best chromosomes and

is the number of elements belonging to the set of population

,

| Algorithm 7: Mutation( ) |

![Automation 06 00080 i005 Automation 06 00080 i005]() |

6. Discussion

In this work we have presented a hybrid approach to humanoid gait generation that combines a compact screw-theory kinematic model with a multi-objective genetic algorithm (GA). By exploiting screw parameters instead of the more common Denavit–Hartenberg formulation, we reduced the number of model parameters and simplified the HTM construction, yet still achieved accurate forward and inverse kinematics for a 14-DoF biped.

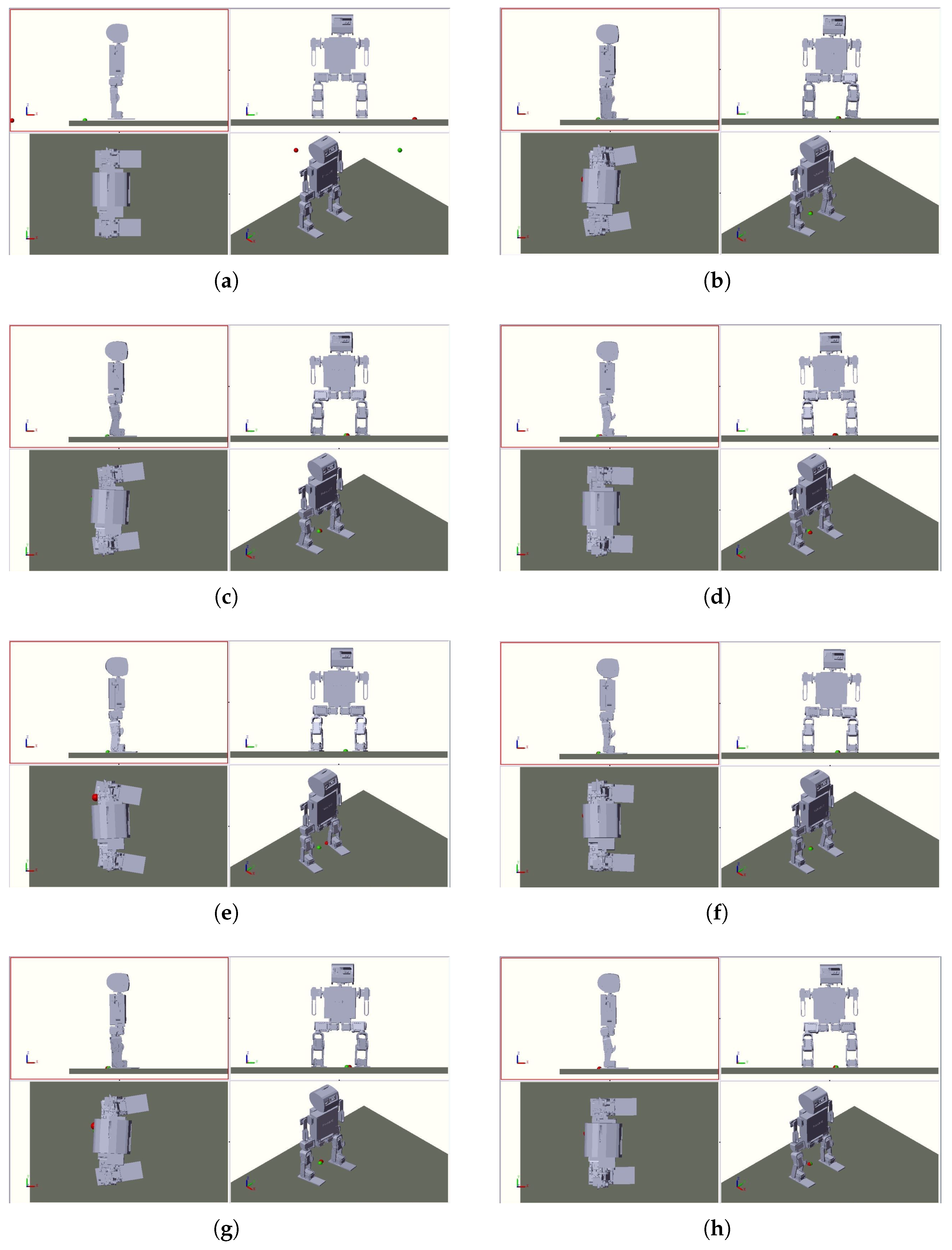

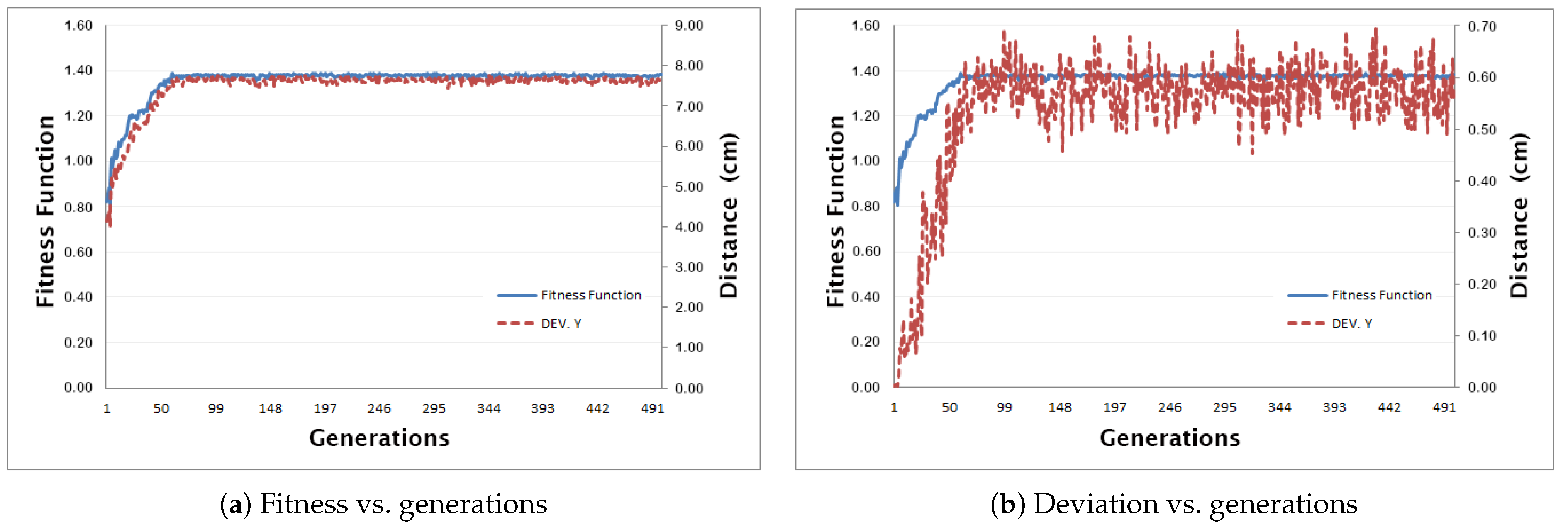

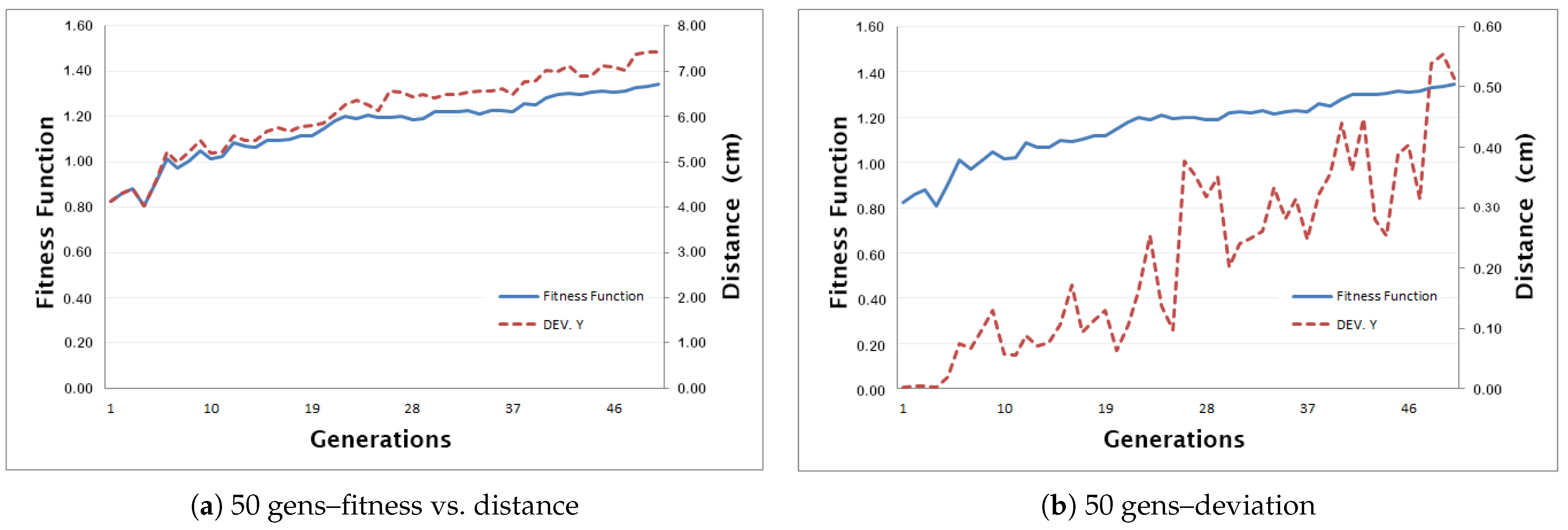

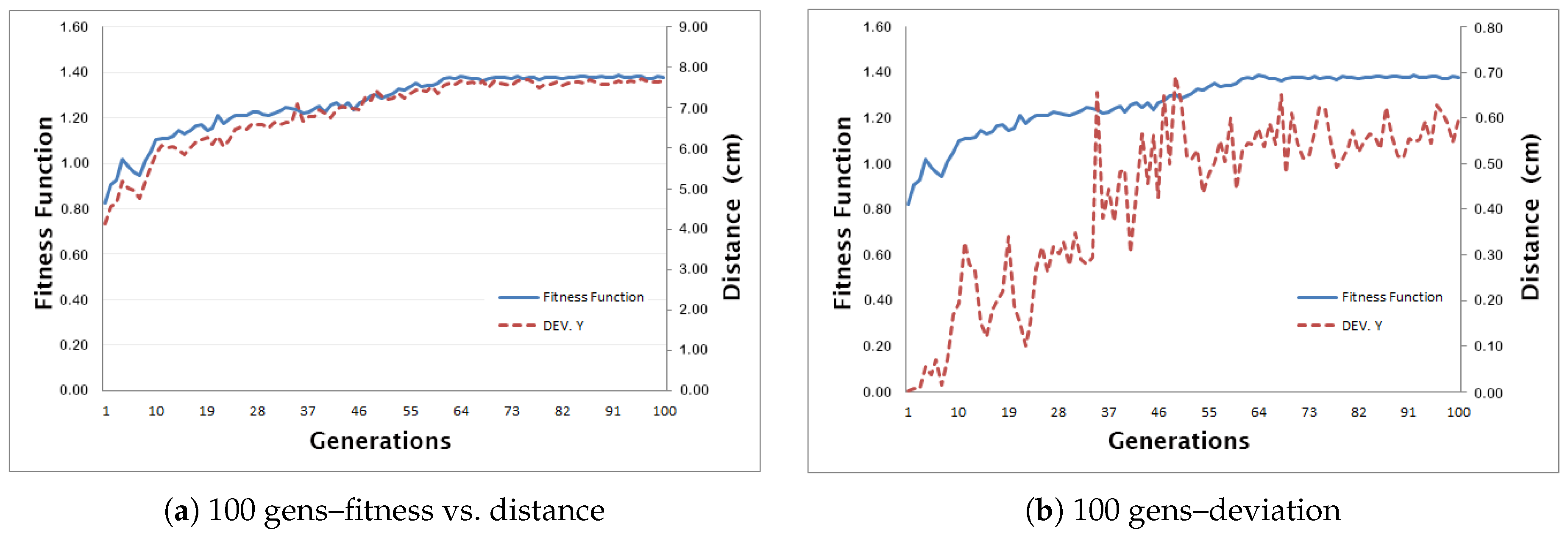

Our simulation results (

Section 5) demonstrate that the GA converges reliably within the first 100–150 generations in terms of overall fitness (step length) and lateral deviation, and fully stabilizes by generation 55 in a 500-gen run (

Figure 7). The high Pearson correlation between fitness and sagittal distance (

–

) confirms that our objective function successfully rewards long steps, while the moderate correlation with lateral deviation (

–

) highlights a residual bias toward sacrificing some stability for stride length.

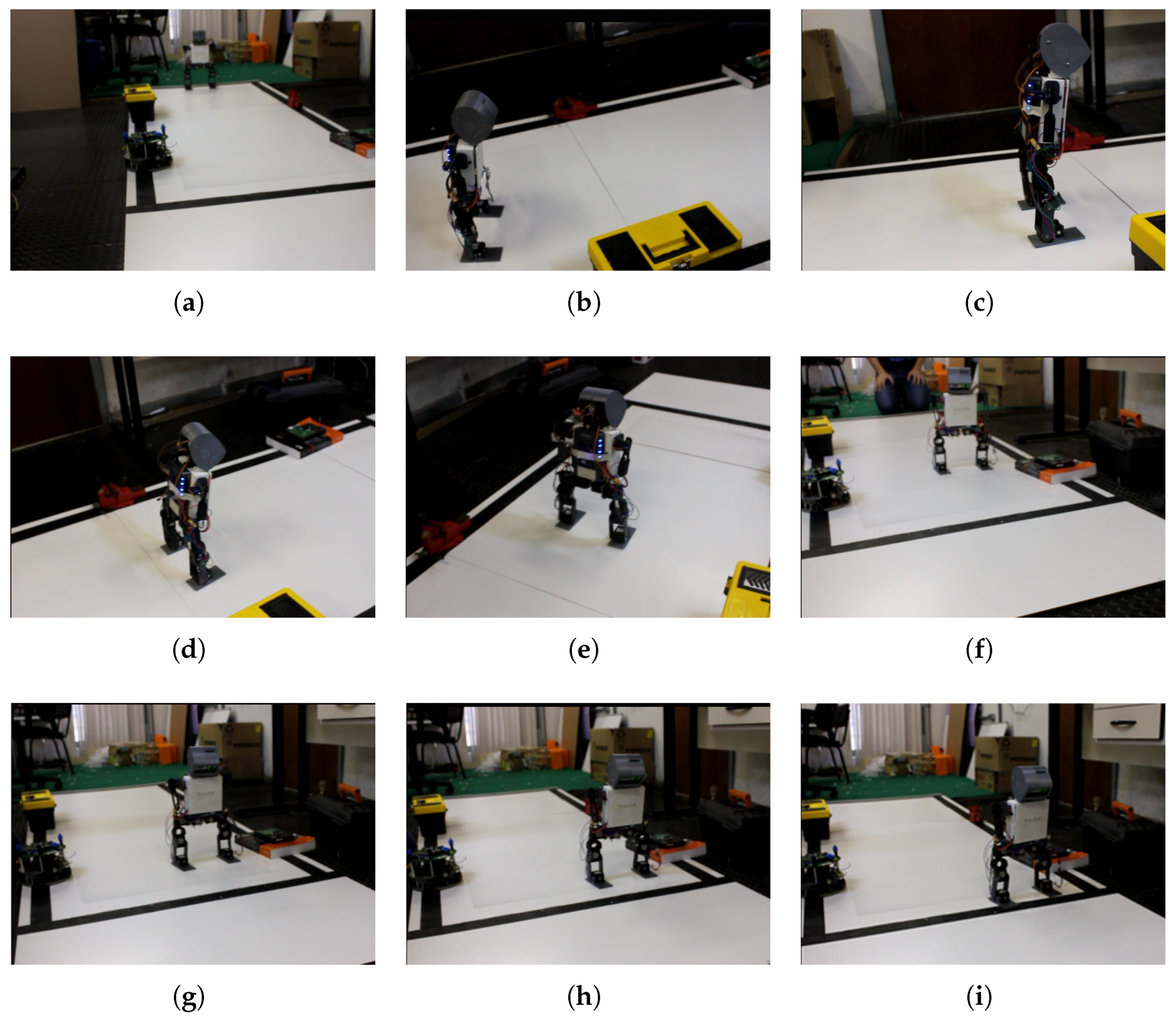

By inspecting all six population-duration scenarios (50, 100, …, 500 generations), we identified generation 421 of the 500-gen run as the best compromise: it attains the highest fitness while keeping deviation within 6.8% of the minimum observed at 150 generations (

Table 4). Deploying these parameters on the real robot yielded consistent 2 m trials without falls (

Figure 11), validating the transferability of our solutions from simulation to hardware.

Despite these strengths, several limitations remain. First, our current penalty term for lateral deviation—proportional to

—proved only moderately effective. Future work should explore alternative multi-objective schemes (e.g., Pareto-based GA [

18]) or dynamic weighting strategies that more aggressively penalize side-to-side drift.

Moreover, we assumed constant friction and neglected inter-joint compliance; extending the model to include joint elasticity, ground compliance and energy consumption metrics would yield a more holistic optimization. Likewise, adding upper-body motion as extra genes (e.g., arm swing, torso yaw) could both improve balance and reduce energy costs, aligning with human-inspired gait strategies [

12].

Finally, while screw-theory offered a concise way to derive kinematics, future implementations could incorporate dynamic stability criteria—such as zero-moment-point (ZMP) or divergent component of motion (DCM) control—within the GA loop, enabling simultaneous optimization of kinematics and dynamics.

In summary, our hybrid screw-kinematics + GA framework provides a flexible, model-based learning approach to humanoid walking. With targeted enhancements to the fitness formulation, feedback integration, and dynamic modeling, this methodology has strong potential to produce stable, efficient gaits across a wide range of tasks and terrains.

7. Conclusions

We have introduced a hybrid gait-generation framework that combines a compact screw-theory kinematic model with a multi-objective genetic algorithm to tune humanoid walking parameters automatically. By parameterizing the foot’s half-elliptical swing speeds and the torso pitch angle, our GA simultaneously maximizes sagittal stride length and minimizes lateral deviation. Simulation results demonstrate reliable convergence—plateauing by generation 55 and yielding near-optimal trade-offs by generation 100—across runs of up to 500 generations, with strong correlations between fitness and forward displacement ( 0.74–0.89) and moderate correlations with side-to-side drift ( 0.57–0.68).

We identified a generation 421 of a 500-gen run as the best compromise and validated these parameters on a 14-DoF humanoid, which successfully walked 2 m in five consecutive trials without falling. Compared to Denavit–Hartenberg-based methods, our screw-theory formulation reduces the parameter count and streamlines the construction of HTMs. At the same time, the GA obviates the need for manual tuning and explicit dynamic equation solving.

In future work, we will refine the lateral deviation penalty—potentially via Pareto-based or dynamic-weighting schemes—and integrate real-time sensor feedback (Inertial Measurement Unit (IMU), foot pressure) to enable closed-loop adaptation over uneven terrain. We will also extend the experimental evaluation to quantify end-to-end command–execution latency on the real platform and assess its impact on gait quality (e.g., lateral drift and step length), integrating these measurements into the proposed optimization and validation pipeline. We will complement the qualitative DH–screw-theoretic comparison with controlled runtime benchmarks (forward kinematics (FK)/Jacobian evaluations) on the same hardware/software stack, and integrate those metrics into the optimization study. Incorporating upper-body motion, energy consumption metrics, and dynamic stability terms (e.g., Zero-Moment Point, ZMP) directly into the GA fitness function will further enhance robustness and efficiency.