This section provides a comprehensive economic assessment of the system, evaluating both capital and operational expenditures to determine the cost-effectiveness of integrating wave energy with H2 production. The analysis considers key financial metrics, including the annual energy production of the WEC system, the OPEX required for maintenance and system operation, and the energy consumption necessary for H2 production. By systematically assessing these factors, the study determines the LCOE as a foundation for understanding the financial feasibility of wave-to-hydrogen conversion. The insights gained from this analysis are then extended to the calculation of the LCOH, ensuring that both the economic and technical aspects of the system are holistically evaluated.

5.1. LCOE Assessment

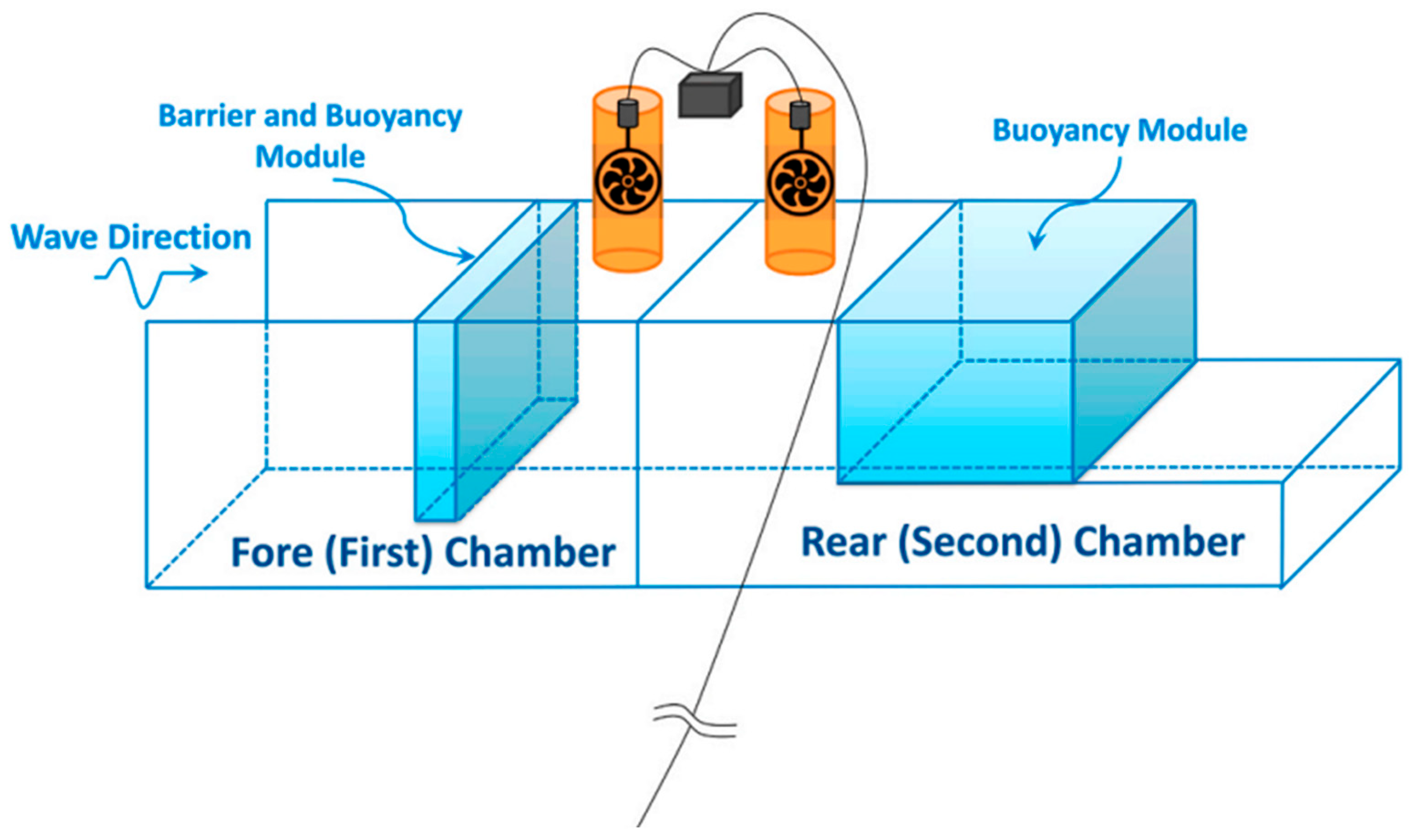

The CAPEX for the WEC are predominantly driven by the costs of its components. Detailed in

Table 4, the breakdown of these costs reveals significant investments, particularly due to the design choice of a dual-chamber oscillating water column. This design incorporates two turbines and two generators, thereby inherently increasing the overall financial outlay.

The turbines employed in this project are impulse turbines. However, accurately estimating the cost of these turbines is challenging due to the proprietary nature of the technology, which many manufacturers prefer to keep confidential. For this analysis, the turbine cost estimation was derived from a similar project involving an offshore wind farm, as documented by Hill et al. [

9]. Their research suggested that a turbine costs approximately 1400 €/kW, meaning the 1 MW WEC in this project would cost 1.4 M€. This analysis considered a 1 MW WEC instead of a larger farm to focus on understanding the H

2 production potential at the individual unit level. This approach enables a detailed assessment of the H

2 generation potential using the proposed WEC system, providing a foundational understanding of its economic and operational viability before scaling up to larger arrays or farms. As this is a double-chamber oscillating WEC, the double-impulse turbines are included in the projected cost. Another way to estimate the cost of the turbines is to use hydropower turbines. According to a study conducted by Paish, the expenses for small hydro projects tend to range from 2500 to 3000 €/kW [

46]. Although this scenario presents a higher cost, it provides a conservative estimate for financial planning. However, since this range is considerably higher and may seem excessively costly for impulse turbines, the lower value from the offshore wind farm analogy was ultimately used for more pragmatic calculations.

Furthermore, the costs associated with the generators and control systems were estimated using data from the 2022 Renewable Energy Power Generation Costs report by IRENA [

47]. According to this report, a medium-range generator would cost approximately 600 €/kW, totalling 600,000 € for the necessary generator capacity. Additionally, the costs for mooring lines and steel housing were calculated based on information provided in a report by Wave Energy Scotland, which outlines the expenditures for large-scale WECs.

Table 4.

Capital expenditures (CAPEX) regarding the dual-chamber wave energy converter (WEC).

Table 4.

Capital expenditures (CAPEX) regarding the dual-chamber wave energy converter (WEC).

| Component | Costs | Unit | Source |

|---|

| Impulse Turbine | 1,400,000 | €/turbine | [9] |

| Generator (600 €/kW) | 600,000 | €/generator | [47] |

| Mooring cost per metre | 200 | €/m | [33] |

| Control System | 400,000 | € | [47] |

| Steel Cost per Tonne | 3000 | €/tonne | [33] |

| Total Steel Housing | 900,000 | € | authors’ estimation |

The financial analysis of the BoP components for the WEC is crucial in understanding the total capital requirements for deploying a 1 MW capacity WEC. This analysis methodically breaks down the costs associated with project development, monitoring systems, installation labour, and turbine installation, all calculated on a cost-per-kilowatt basis to provide a standardised approach to financial planning and budgeting. These calculations are based on the same study by Hill et al., which estimates the costs for wind turbine installation, as shown in

Table 5 [

9].

Following the core component costs were the expenditures related to the anchoring system, comprising the anchor itself and the anchor cable. The cost of the anchor was estimated based on an assumption of its weight at 6 tonnes, priced at 2.5 €/kg. This assumption was based on standard industry practice for similar marine installations, where a 6-tonne anchor is considered sufficient to ensure stability under the expected environmental loads, such as currents and wave forces. For the anchor cable, calculations were premised on a diameter of 0.1 m. Using the density of steel and the specific water depth, a formula was applied to determine the additional cable length required beyond the direct distance. This extra length serves as a safety measure, allowing for some slack to accommodate movement and prevent the anchoring system from snapping under tension, thereby ensuring its integrity and durability. The calculated cost for the steel cable considered these factors to arrive at a total projected expense.

Marine transport expenses were derived from models and data provided by Wave Energy Scotland. For operational planning, the speed of the AHTS vessel, which is 5 knots, ca. 10 km/h, was considered. The total travel time to the installation site was estimated by dividing the journey’s distance by the vessel’s daily travel capacity, resulting in an estimated number of days required for transit. To this figure, two days were added as a buffer to account for potential delays during the installation period. The total number of days calculated for the round trip was then multiplied by the daily operational cost of the AHTS. Additionally, an extra 10% was factored into the overall costs as a weather contingency to accommodate potential delays or operational adjustments due to adverse marine conditions. This approach yielded a comprehensive estimate of the total cost for marine transportation, encompassing both the logistical and financial planning required to ensure the timely and efficient delivery and installation of the WEC components at the site.

In addition to the initial setup and operational components, the CAPEX for the WEC also encompass transportation and decommissioning costs. According to research conducted by Guo et al., these costs are quantified in €/kW [

48]. Specifically, the decommissioning costs are estimated at € 420/kW, accounting for approximately 10% of the total CAPEX. It is important to note that these costs vary based on the project’s location, as different environments and logistical challenges can significantly influence overall expenditure.

Regarding OPEX, insights from a report by Michael O’Connor highlight that wave energy projects typically incur an OPEX of 24 €/kW per year [

49]. Applying this standard rate to the specific WEC project results in an estimated operational cost of € 720,000 over the project’s expected lifetime (

Table 6). This estimation provides a baseline for budgeting the regular costs associated with operating the WEC, including maintenance, management, and routine repairs, which are essential for ensuring the installation’s longevity and efficiency.

Alongside other expenses, the costs associated with dry docking are a significant consideration. Based on a study by Agamemnon et al., the cost of a dry-docking operation in 2007 was approximately 370,000 €, which, adjusted for inflation, amounts to about 700,000 € today [

50]. However, it is important to note that this figure pertains to much larger shipping vessels than those involved in this project. Agamemnon et al. primarily focused on container ships with capacities of 1000 TEU, each TEU being a standard unit with internal dimensions of 20 feet long, 8 feet wide, and 8 feet tall [

44]. Given the smaller scale of this project, a tailored estimation is required for dry docking costs. Therefore, the cost was adjusted downward to more accurately reflect this vessel’s size and scope, estimating the dry-docking cost for a small vessel in this project to be approximately 200,000 € per operation. Over the project’s lifetime, this equates to a total of around 1 M€. Although this may still represent an overestimate, it provides a conservative figure that ensures financial prudence and buffers against unforeseen expenses, offering a safer approximation for financial planning and budgetary allocations.

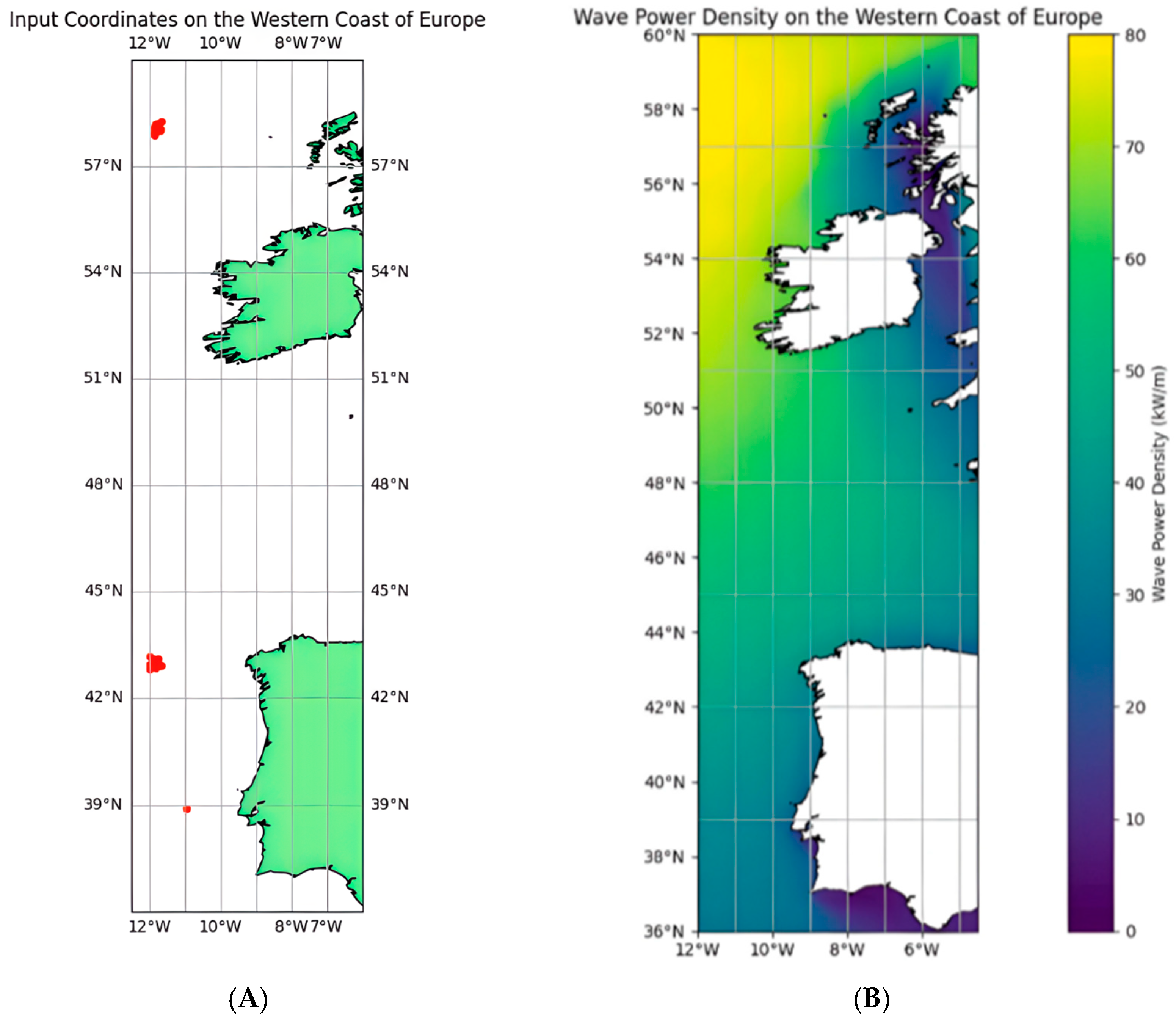

Calculating the annual energy production (Equation (1)) is a pivotal element in determining the LCOE for the WEC. A thorough understanding of the wave power density at the specific deployment location is crucial to this calculation. Cabo da Roca in Portugal was initially identified as a potential site due to its favourable marine conditions. According to an extensive literature review, the wave power density in this region is estimated to be approximately 35–40 kW/m. This metric reflects the power available per metre of wavefront and is vital for assessing the WEC’s total annual energy output.

Within Equation (1),

Poutput is the wave power density (45 kW/m). The width of the WEC is based on the dimensions provided by Company A, which is 25 m [

51]. The primary efficiency of the WEC is 70%, reflecting the efficiency of wave energy capture and conversion to pneumatic power (compressed air energy confined within the chambers of the OWC device) by the system before any power conditioning or electrical conversion processes occur. The Power Take-Off (PTO) efficiency, which refers to the combined efficiency of the turbine and electric generator, is 55% in this study. This PTO efficiency encapsulates the turbine’s capability to convert the pneumatic power of the air trapped inside the chambers into rotational energy, and the generator’s ability to convert this rotational energy into electrical energy. Additionally, the exploitation factor, which represents the operational availability and reliability of the WEC, accounting for downtime due to maintenance, suboptimal sea conditions or other natural phenomena, is 95%. Consequently, the total overall efficiency of the WEC system, which combines these factors, is calculated to be 36.6%. Capacity factor, another critical performance metric, further contextualises these efficiencies within the operational environment of the WEC. It is defined as the ratio of the actual energy produced over a period to the energy that would have been produced at continuous full power operation during the same period. As highlighted in studies such as those conducted on the Mutriku wave farm, the capacity factor significantly influences the overall energy output and economic viability of wave energy systems, underscoring its importance in assessing WEC performance alongside other efficiency metrics [

52].

It is also worth mentioning that, in addition to factors such as the need for maintenance operations, sub-optimal or survival conditions that cause energy production interruptions and affect the capacity factor of WECs, specific concerns exist for OWCs, including the effects of air humidity, which can further reduce system performance and suppress annual energy production. According to Medina-Lopez [

52], air humidity can significantly impact energy output under certain conditions. This effect has not been explicitly accounted for in the estimated annual energy production of the FOWC device in this study, as it requires a dedicated investigation to accurately assess its impact. However, general considerations of factors such as maintenance operations and the effects of air humidity on energy production have been incorporated through an assumed capacity factor of 0.95. In this context, future studies may possibly be conducted to refine this estimation, ensuring a more precise capacity factor and a more accurate assessment of annual energy production.

There are 8760 h in a year. This calculation yields an annual energy production of 3604 MWh/year (44 × 25 × 0.70 × 0.55 × 0.95 × 8760). To determine the average hourly energy output, this value is divided by the total number of hours in a year (365 days × 24 h = 8760 h), resulting in an average energy production of 411 kWh per hour. This final value accounts for all efficiency adjustments, including the capacity factor, conversion losses, and downtime considerations.

To calculate the total energy produced by the WEC over its 30-year project lifetime, the annual energy output (in kWh) was first estimated based on the WEC’s operational parameters. This annual energy was then multiplied by 1000 to convert into watt-hours, ensuring unit consistency. To account for the time value of energy production over the project’s lifespan, a discount rate of 5% was applied. The total lifetime energy is then calculated using Equation (2) [

53].

Finally, the LCOE for the project was calculated to provide a comprehensive financial assessment of the WEC’s viability. The LCOE is then calculated using Equation (3),

where r is the discount rate (i.e., 5%) and n is the project lifetime (30 years) [

9]. This formula effectively discounts future energy outputs to their present value, similar to how financial costs are adjusted in economic evaluations. Using this method, the total energy output over the project’s lifetime is accurately represented, taking into account the diminishing value of future energy production due to the 5% discount rate.

To calculate the LCOE, the model incorporates both the CAPEX and the OPEX over the project’s lifecycle, typically set at 30 years. To accurately sum these costs, the time value of money is accounted for using a discount rate, ensuring that future costs are represented in present-value terms. The total OPEX is spread across the 30-year project lifespan. To achieve this, the annual OPEX is adjusted using Equation (4), which considers the discount rate.

This approach ensures that OPEX costs are represented as a present value sum, adjusted for the effects of time and the discount rate. The adjusted OPEX is then added to the CAPEX to compute the total cost over the project’s life. This sum is then divided by the total energy output over 30 years to derive the LCOE. By using this method, both CAPEX and OPEX are appropriately accounted for over the project’s lifespan, allowing for a more accurate representation of the levelised cost, which reflects the influence of time, OPEX, and the discount rate on the overall economic analysis. In the case of Cabo da Roca, the total CAPEX was calculated to be 6,980,332 €.

The LCOE encapsulates the average cost per unit of electricity generated, factoring in all costs associated with the project from inception through decommissioning, divided by the total energy output. This metric is crucial for evaluating the economic viability of the wave energy project in comparison to alternative energy sources and for making informed decisions about investment and development in renewable energy technologies. The result of this calculation will inform future strategies regarding project scaling, potential return on investment, and competitive pricing in the energy market.

5.2. LCOH Assessment

Following the computation of the LCOE, the LCOH was calculated. Several foundational assumptions were required, including the project’s projected lifetime and the applicable discount rate. While the project’s lifetime is expected to span 30 years, that does not necessarily apply to the electrolyser system, which necessitates its own specific lifetime assessment.

Full load hours refer to the time an electrolyser operates at its maximum rated capacity over a specific period, in this case, a year. According to Agora, the electrolysers for green H

2 production should operate at about 3000–4000 h per year, as they rely on electricity from inexpensive renewable energy [

54]. For the calculations of this project, 4000 h are taken as the full load hours.

The stack lifetime of PEM electrolysers typically ranges from 60,000 to 80,000 h [

55]. This range is supported by industry reports, such as the IEA Global Hydrogen Review (2023), which indicates that modern PEM electrolysers, particularly when operated under optimised conditions and with proper maintenance, can achieve lifetimes of up to 80,000 h [

11]. The cost of replacements is 35–45% of the total system capital costs (referring only to the H

2 production in the water electrolyser and not the whole WEC module). This estimate aligns with industry and academic studies, which indicate that stack replacement costs typically constitute 30–40% of electrolyser CAPEX, depending on technology type and degradation rates. Reports support these cost assumptions, reinforcing the significance of stack replacement expenditures in long-term H

2 production economics [

11]. Assuming a stack lifetime of 80,000 h, the stack would need to be replaced every 15 years with a full load of 4000 h, meaning it would be replaced once during the 30-year project lifetime.

Table 7 provides the initial parameters used in the analysis, including the discount rate, project lifetime, stack lifetime, energy consumption and stack replacement costs as a percentage of the electrolyser system’s CAPEX.

Furthermore, the specific energy consumption of the electrolyser is significantly influenced by its operational pressure. It is crucial to specify the system pressure, as operating conditions below 30 bar can introduce inefficiencies, including higher overpotentials, increased bubble resistance, and suboptimal membrane conditions, all of which increase energy consumption. Conversely, operating the PEM electrolyser above 30 bar can mitigate these issues, enhancing the system’s overall efficiency and reducing the specific energy consumption to an assumed optimal value of 55 kWh/kgH

2. Equation (5) depicts the energy consumption when the inlet pressure is below 30 [

38].

The parameters used to calculate energy consumption for pressures below 30 bar are as follows: the outlet pressure is 30 bar, the heat capacity ratio (HCR) is 1, and the system’s total efficiency is 80%. The ambient temperature (Tamb) is 298 K, and the heat capacity (c) of H2 is 14 kJ/kgH2. With an inlet pressure of 1 bar, the energy demand increases by 2.4 kWh/kgH2, resulting in a total of 57.434 kWh/kgH2.

The assumed system efficiency of 80% corresponds to the nominal performance of a PEM electrolyser operating under stable conditions. In practice, however, the efficiency of electrolytic H

2 production varies with the intermittency of renewable power and tends to decline gradually due to membrane and catalyst degradation. Studies indicate that long-term degradation can reduce efficiency by approximately 0.5–1% per year, while variable loading from fluctuating wave energy can lower the lifetime-averaged efficiency to around 73–76% [

56]. A constant efficiency was therefore adopted here to maintain consistency across scenarios and isolate the effects of wave resource variability on cost. Nevertheless, incorporating a lifetime-averaged efficiency would likely increase the overall LCOH by 4–7%, a refinement recommended for future dynamic modelling efforts.

The H

2 system’s CAPEX was then procured by adding different components, including EPC costs, compressor costs, storage costs, reverse osmosis system costs, and electrolyser costs. According to Hill et al., a PEM electrolyser costs ca. 2000 €/kW [

9]. All these costs are detailed in

Table 8. The resulting CAPEX was dependent on the storage type and the system’s pressure, all of which were taken into account by the model itself.

The cost of desalination is based on a small-scale system. According to data from EST Water Products, a compact reverse osmosis system capable of processing approximately 5000 gallons (or 18,927 L) per day measures 30 in × 38 in × 47 in (76.2 cm × 96.52 cm × 119.38 cm) and has a maximum price of about 6900 € [

54]. Although the maintenance and chemical cleaning requirements of reverse osmosis systems can represent a notable share of OPEX in large desalination plants, their contribution here is minimal due to the small feed-water demand. The maximum freshwater requirement for H

2 production is about 3 m

3/day, corresponding to a maintenance and chemical cost of only 0.05–0.15 € m

−3 [

59,

60]. This equates to roughly 50–100 €/yr, or less than 0.01% of the total annual operating costs, confirming that desalination maintenance has a negligible influence on overall techno-economic results.

While this system is designed to produce a volume of water that exceeds the needs of a 1 MW PEM electrolyser, it provides a useful benchmark for setting a maximum price threshold in the LCOE analysis. It is important to note that the capacity required for this project’s electrolyser will likely be less than 500 kW. This consideration enables the appropriate scaling of the desalination system, ensuring that investment in capacity aligns with operational requirements.

This strategic sizing not only helps optimise the investment in infrastructure but also aligns the operational output with the project’s energy production capacities. Budget management can be effectively controlled by using the cost of a relatively larger system as a price cap, potentially driving down the CAPEX if a smaller, less expensive desalination system that meets the project’s needs can be identified. Such financial prudence is essential to maintaining the project’s overall economic viability, ensuring that the desalination process contributes positively to the sustainability and efficiency of the H2 production operation.

Following the CAPEX calculations, the OPEX had to be calculated. This encompasses several critical components, each contributing to the overall cost structure of the H

2 production process. The general OPEX for the H

2 production system is estimated at 51 €/kW per year [

9]. This cost covers the routine operation and maintenance of the H

2 production equipment, including the electrolyser and associated systems. It reflects the ongoing expenses required to keep the H

2 production process running efficiently over the project’s lifespan. This figure is crucial for calculating the overall LCOH and ensuring that the project remains economically feasible.

Beyond the base OPEX, specific costs are associated with the liquefaction and compression of H

2, depending on the chosen storage method. The liquefaction process, which converts gaseous H

2 into its liquid form to increase storage density, incurs a cost of 3 €/kgH

2 [

11]. Additionally, the storage cost for maintaining H

2 in its liquid state over a year is 0.364 €/kgH

2. While not as impactful on OPEX, it must still be included in the overall financial calculations to ensure a comprehensive cost assessment.

Compression costs also vary depending on the required storage pressure. The cost of H

2 compressed to 350 bar is 1.5 €/kgH

2, while the compression to 700 bar, which requires more sophisticated equipment and a higher energy input, is 2 €/kgH

2 [

57]. Furthermore, each compression level incurs its respective annual storage costs, 0.004 €/kgH

2 for 350 bar and 0.013 €/kgH

2 for 700 bar [

61]. Again, although these additional storage costs are relatively small, they are important to include in the overall OPEX to provide an accurate and complete financial picture of the H

2 production system.

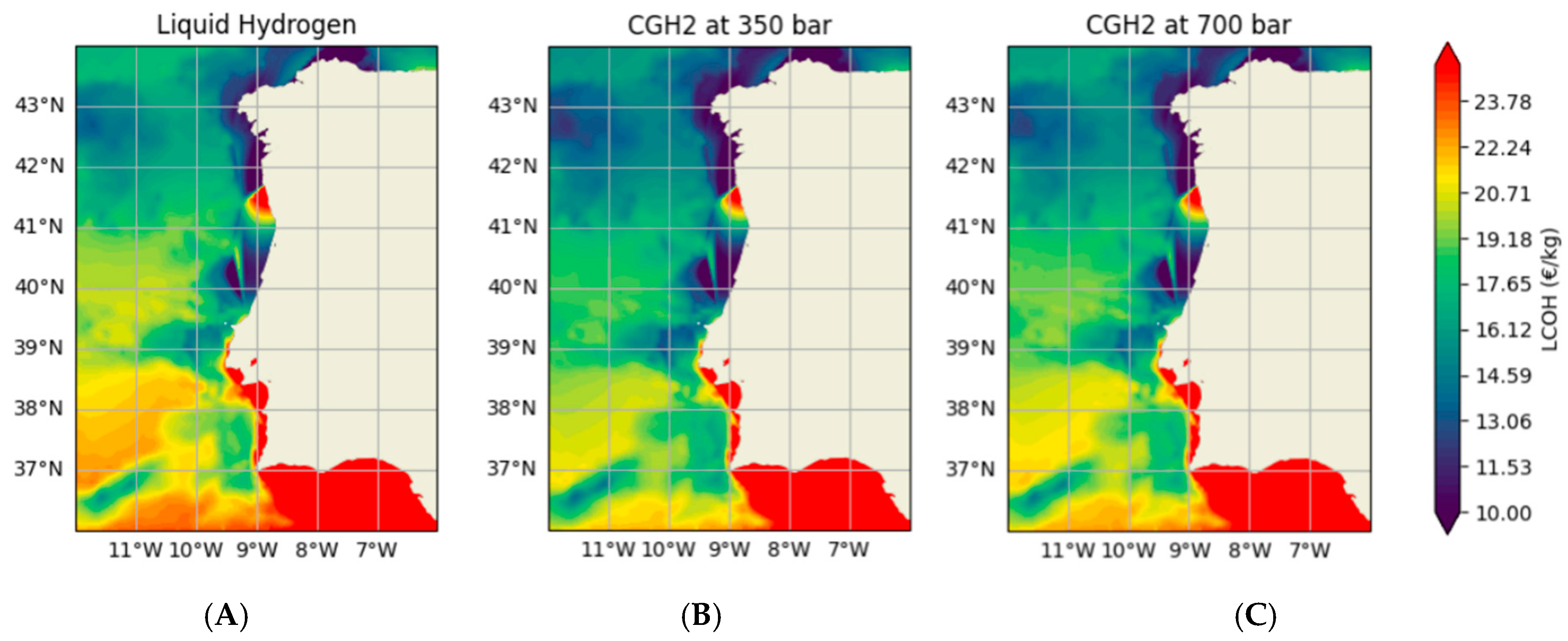

Finally, the LCOH is calculated, integrating the CAPEX, OPEX, and electricity costs, all expressed in €/kgH

2. Equation (6) displays the total OPEX calculation specifically tailored to the chosen storage technology and system pressure [

53]. It is essential to note that while the LCOH is determined per kilogram of H

2, the total H

2 demand and, consequently, the required storage volume will be assessed later to ensure they fit within the available space of the WEC. This spatial consideration is not factored into the current LCOH calculation.

The general OPEX is multiplied by the SEC (specific energy consumed) and added to the storage costs, which are then divided by the full load hours to distribute the annual storage costs over the total amount of H2 produced during those operational hours, ensuring that the cost per unit of H2 accurately reflects the operational capacity of the system. The liquefaction and compression costs (Cliq/comp) are not divided by the full load hours because these costs are typically variable and directly proportional to the amount of H2 produced, rather than fixed annual costs like storage infrastructure expenses. This distinction enables an accurate breakdown of costs based on their nature (fixed vs. variable) and their impact on H2 production economics.

The electricity costs are derived by multiplying the LCOE by the specific energy consumption associated with the system’s operating pressure. This figure is then combined with the CAPEX and OPEX to arrive at the final LCOH for the given location, as shown in Equation (7) [

53]. Electricity costs constitute the largest portion of the total cost of H

2 production, underscoring the critical role of energy efficiency in the project’s overall economic feasibility. In the case of Cabo da Roca, the OPEX costs amount to 2.23 €/kgH

2, the CAPEX sums to 0.46 €/kgH

2, and the electricity costs are 8.70 €/kgH

2, resulting in a total LCOH for Cabo da Roca of 11.39 €/kgH

2.

An essential aspect of this analysis is determining the H2 demand to assess how much H2 can be stored within the WEC. This step is crucial for understanding the storage capacity requirements and ensuring that the system design can accommodate the necessary volume of H2. However, it is important to note that this storage capacity evaluation does not directly impact the LCOH. The LCOH is calculated per kilogram, providing a holistic view of the cost of H2 production regardless of the total volume stored. This approach allows for a clear understanding of the economic viability of H2 production, independent of the specific storage capacity constraints of the WEC.

Another complexity of integrating the H

2 production system with the WEC is the effective distribution of the energy produced by the WEC across the H

2 subsystems. This distribution is influenced by the type of H

2 storage used and the duration for which the H

2 is stored. For instance, in the case of liquid H

2, a significant portion of energy must be allocated not just for liquefaction but also for maintaining the H

2 in its liquid state.

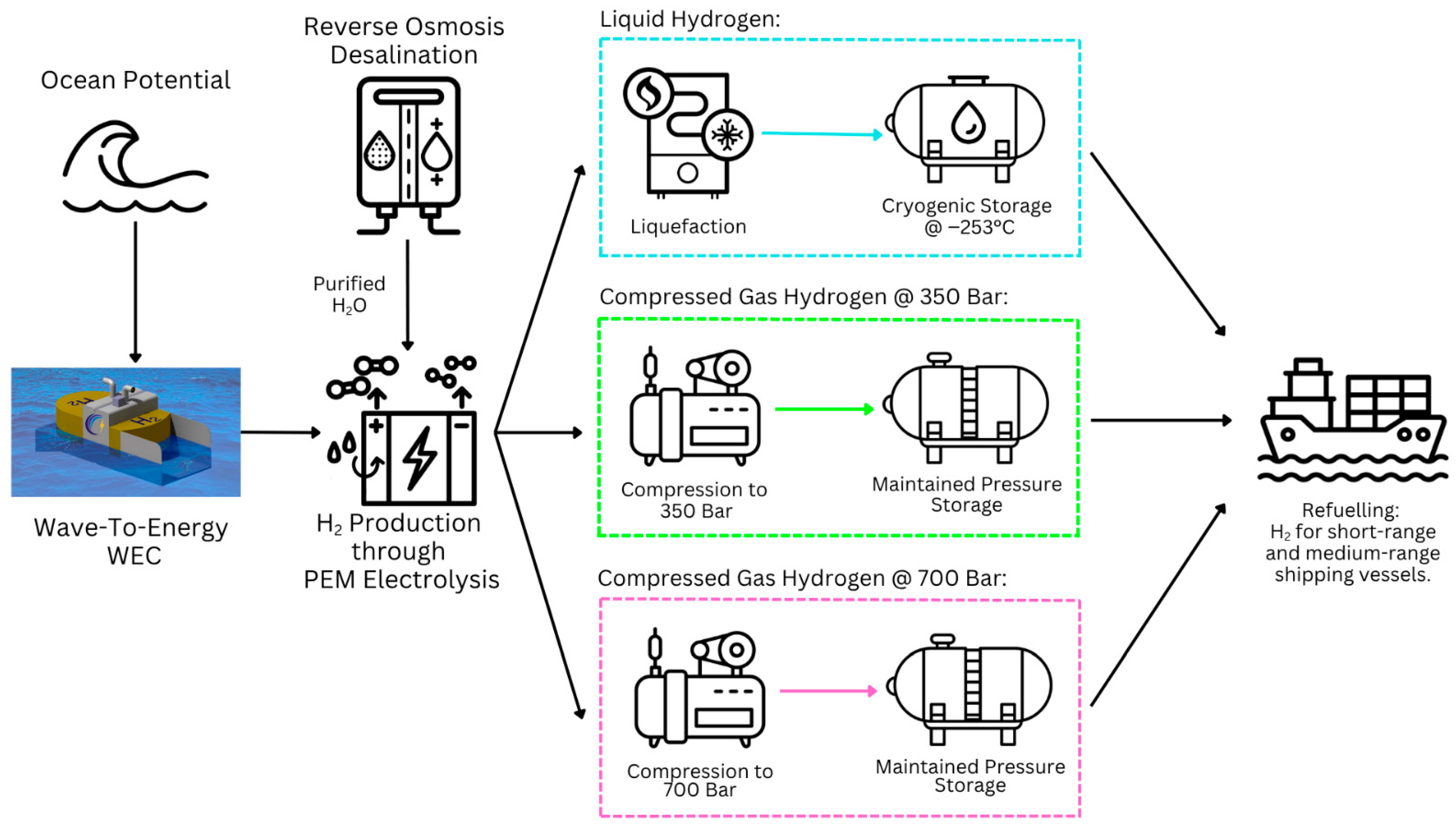

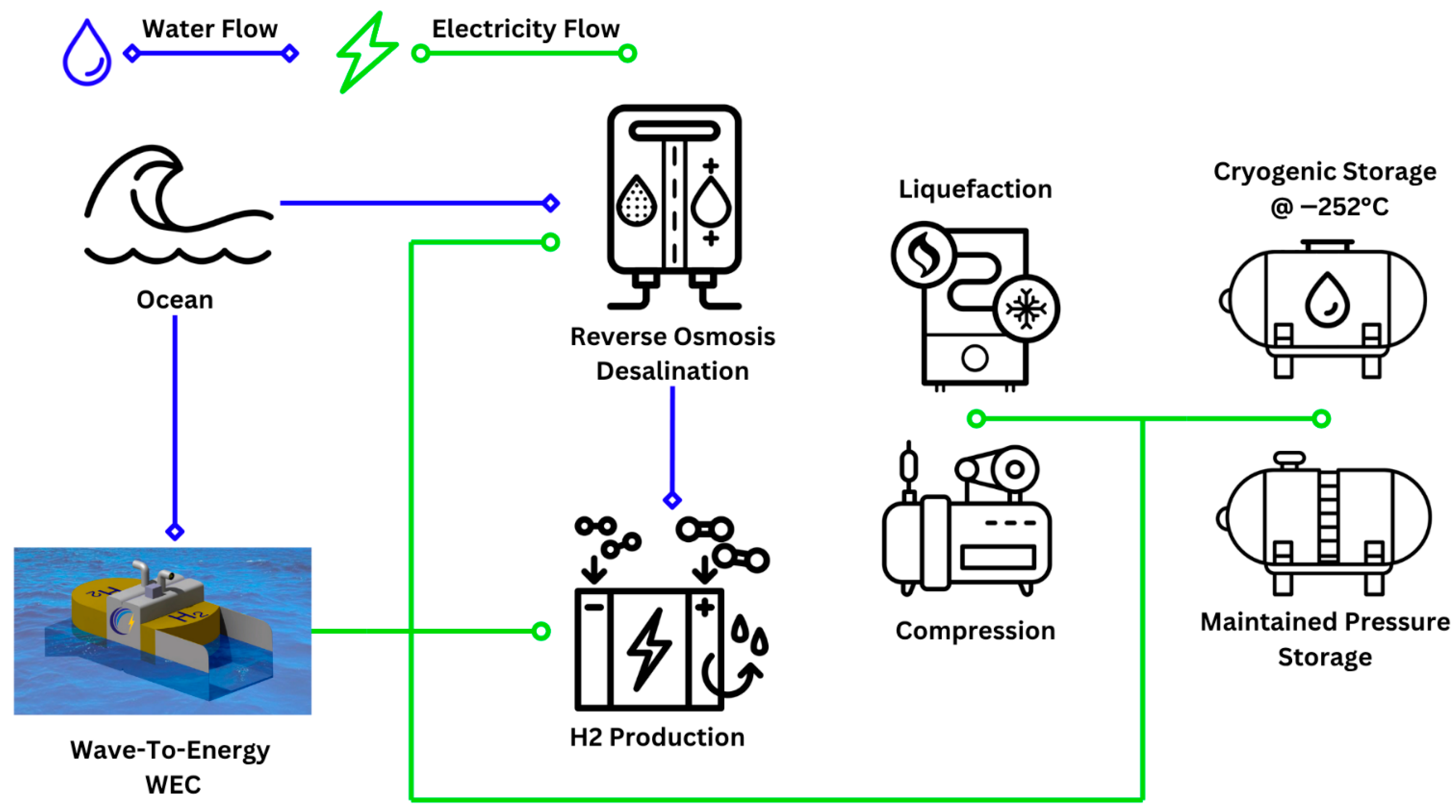

Figure 9 illustrates the energy and water flow across the WEC and H

2 systems, with power being distributed to the desalination system, electrolyser system, storage, and either compression or liquefaction.

A baseline energy allocation has been set for the control, emergency, and communication systems, which are critical for the safe and efficient operation of the WEC. These allocations are fixed at 5% and 1% of the total energy output, respectively, leaving 94% for the remaining subsystems.

The energy requirements for each storage system have been calculated based on data extracted from an extensive literature review. The energy calculation is particularly detailed for desalination, essential for ensuring the purity of water used in H

2 production. It is based on the assumption that desalination consumes approximately 3.5 kWh for every cubic metre of water processed. Considering that one cubic metre equals 1000 L and that only 9 L of water are required to produce one kilogram of H

2, the energy expenditure for desalination translates to a mere 0.0315 kWh/kgH

2.

Table 9 presents the breakdown of each component of the H

2 system and its corresponding energy requirements per kilogram of H

2.

Table 10 below provides a detailed breakdown of the energy allocation for each H

2 storage type, along with its respective components. 94% of the energy produced, excluding that allocated to control and emergency systems, is further divided according to the specific energy requirements for each storage type, as outlined in the previous table. This distribution strategy ensures that each component of the H

2 production process receives an adequate amount of energy to function efficiently while also accounting for the varying demands of different storage types. Notably, LH

2 storage systems allocate the least amount of energy for production due to the high energy demands of liquefaction and maintaining H

2 in a liquid state. In contrast, CGH

2 systems have the most energy available for production, reflecting their lower energy requirements for compression and storage. This tailored approach to energy allocation is designed to optimise the overall efficiency of the H

2 production system and maximise the output from the energy harvested by the WEC.

Finally, after determining the amount of energy allocated to H

2 production, the next step is calculating the appropriate power class for the electrolyser and the maximum H

2 output in kilograms. This calculation is based on the capacities of current PEM electrolysers, specifically referencing data from the Handtmann 1 MW electrolyser datasheet [

66]. The daily H

2 production can be accurately estimated using a straightforward proportional relationship between the energy input and the electrolyser’s capacity.

Once the daily H2 production rate is established, the next consideration is the storage requirement, which varies depending on how long H2 needs to be stored. Three storage scenarios are considered: 2 weeks, 1 month, and 2 months. The size of the H2 storage tanks will be directly influenced by these periods. The longer the storage duration, the larger the tank capacity needed to accommodate the cumulative H2 production over that period. This approach ensures that the system is designed with flexibility in mind, allowing for the storage of adequate H2 volumes based on specific operational needs and periods, while also optimising the efficiency and cost-effectiveness of the overall H2 production and storage system.

The H

2 demand is calculated using the following parameters: 311.3 kWh of energy is dedicated to H

2 production, assuming the storage technology is LH

2, and the energy produced from Cabo da Roca is 411.5 kWh. The power class of the electrolyser is 400 kWh, determined by rounding the energy dedicated to H

2 to the nearest 100. A 1 MW PEM electrolyser can produce 528 kg of H

2 per day, based on Handtmann, and it is proportional to the lower power classes of electrolysers, so for this specific configuration, 211.2 kg of H

2 per day will be produced [

66].

Given that the WEC allocates a 10 m × 10 m × 5 m space (500 m3) for H2 production systems, it is essential to calculate the remaining space available for H2 storage after accounting for the required equipment. This includes the dimensions of the electrolyser, desalination system, compression system, and liquefaction system. Conversion values were used to determine the volume of H2, based on the storage technology, with the compressed gas calculated using the ideal gas law.

The calculations for determining space availability for the storage of CGH

2 and LH

2 are based on the following parameters: the electrolyser (1 MW) occupies 1.16 m

3 [

40], while desalination requires 0.88 m

3 [

58], and compression takes up 0.48 m

3 [

67]. The liquefaction system dimensions were not specified but were assumed to be 1.5 m × 1.5 m × 1.5 m for safety calculations.

After allocating space for the necessary systems, the remaining volume available for H2 storage is 497.48 m3 for compressed H2 and 494.58 m3 for liquid H2. Converting these volumes into the equivalent kilograms of H2 can give a clearer understanding of the storage capacity for each technology at each location. This calculation is crucial for determining how much H2 can be stored within the WEC, ensuring that the design accommodates the necessary storage requirements while optimising the overall efficiency and functionality of the H2 production system.

Evaluating the techno-economic feasibility of integrating wave energy and H2 production requires a structured approach that accounts for multiple interdependent parameters. Instead of utilising a fully automated computational optimisation algorithm, this study employs a systematic manual evaluation model to iteratively assess LCOE, LCOH, and system design feasibility. Given the complex interdependencies between site selection, infrastructure costs, electrolyser operating conditions, and H2 storage methods, a purely algorithmic optimisation would struggle to capture the full scope of design trade-offs effectively.

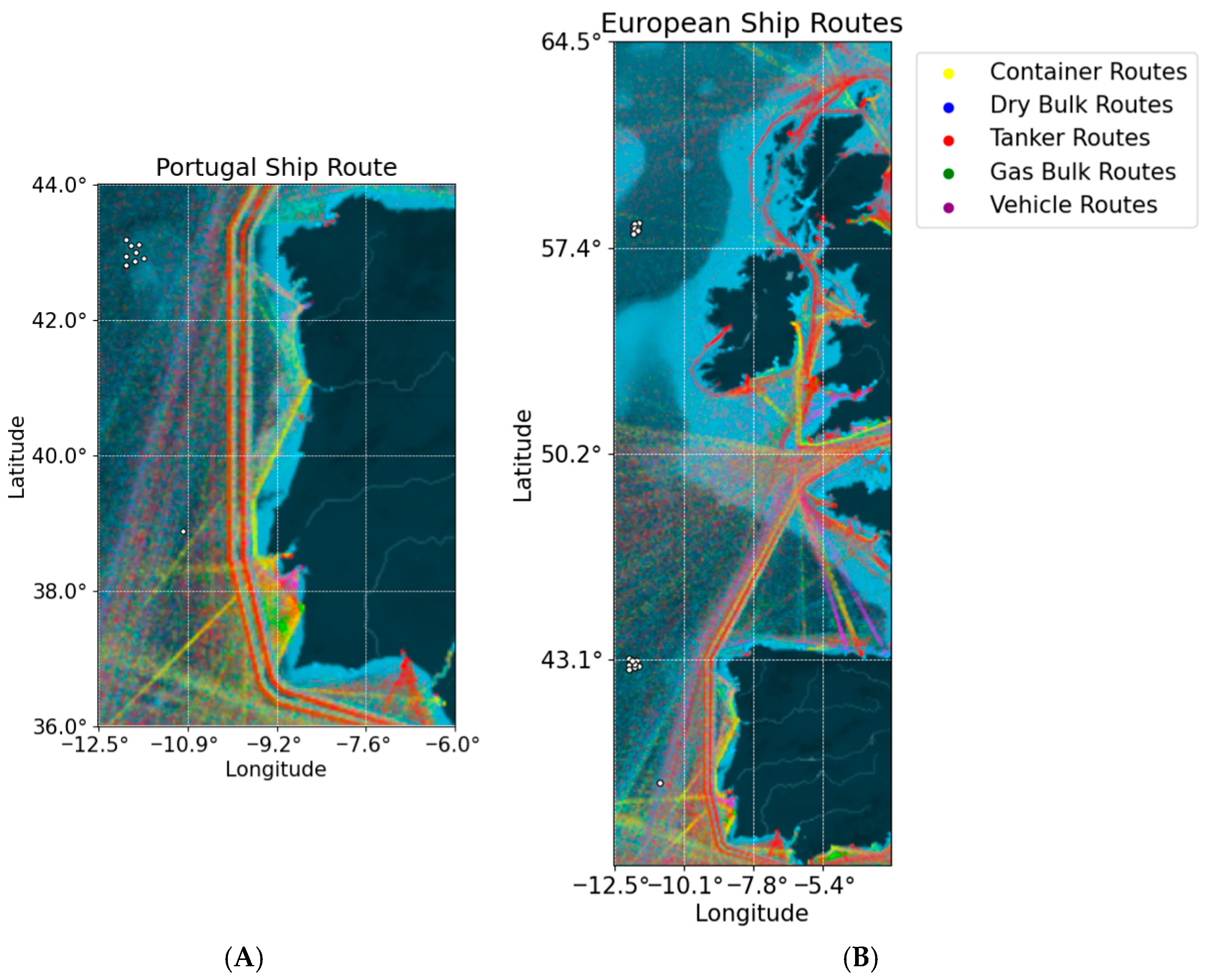

Following the calculation and organisation of LCOE and LCOH values in an Excel-based model, a structured, systematic evaluation was applied to further refine the analysis. This model incorporated multiple data points, each representing a different location with specific water depth and wave power density, as identified in the location analysis. The primary objective of this process was to identify the most advantageous sites for wave energy conversion, balancing the cost of electricity and H2 production against local environmental conditions. Decision variables, such as location selection, water depth, and wave power density, were systematically assessed. Constraints were applied to exclude sites exceeding 2000 m in depth, where mooring and installation costs would become prohibitively expensive.

By integrating numerical filtering techniques with a stepwise feasibility assessment, the model ensured that site selection was guided by technical requirements, cost considerations, and energy efficiency metrics. This iterative feasibility approach allowed for a comprehensive comparison of LCOE and LCOH values across multiple locations, providing a structured framework for identifying the most cost-effective and energy-efficient deployment options. The process ensured that selected sites met the technical requirements for WEC deployment while maximising the project’s economic viability and operational efficiency.