Mechanistic Evaluation of Surfactant-Enhanced Oil Mobility in Tight Conglomerate Reservoirs: A Case Study of Mahu Oilfield, NW China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Materials

2.1.1. Core Samples and X-Ray Diffraction Analysis

2.1.2. Crude Oil and Formation Water Analysis

2.1.3. Surfactants

2.1.4. Fracturing Fluid Formulation in Use

2.2. Experimental Methods

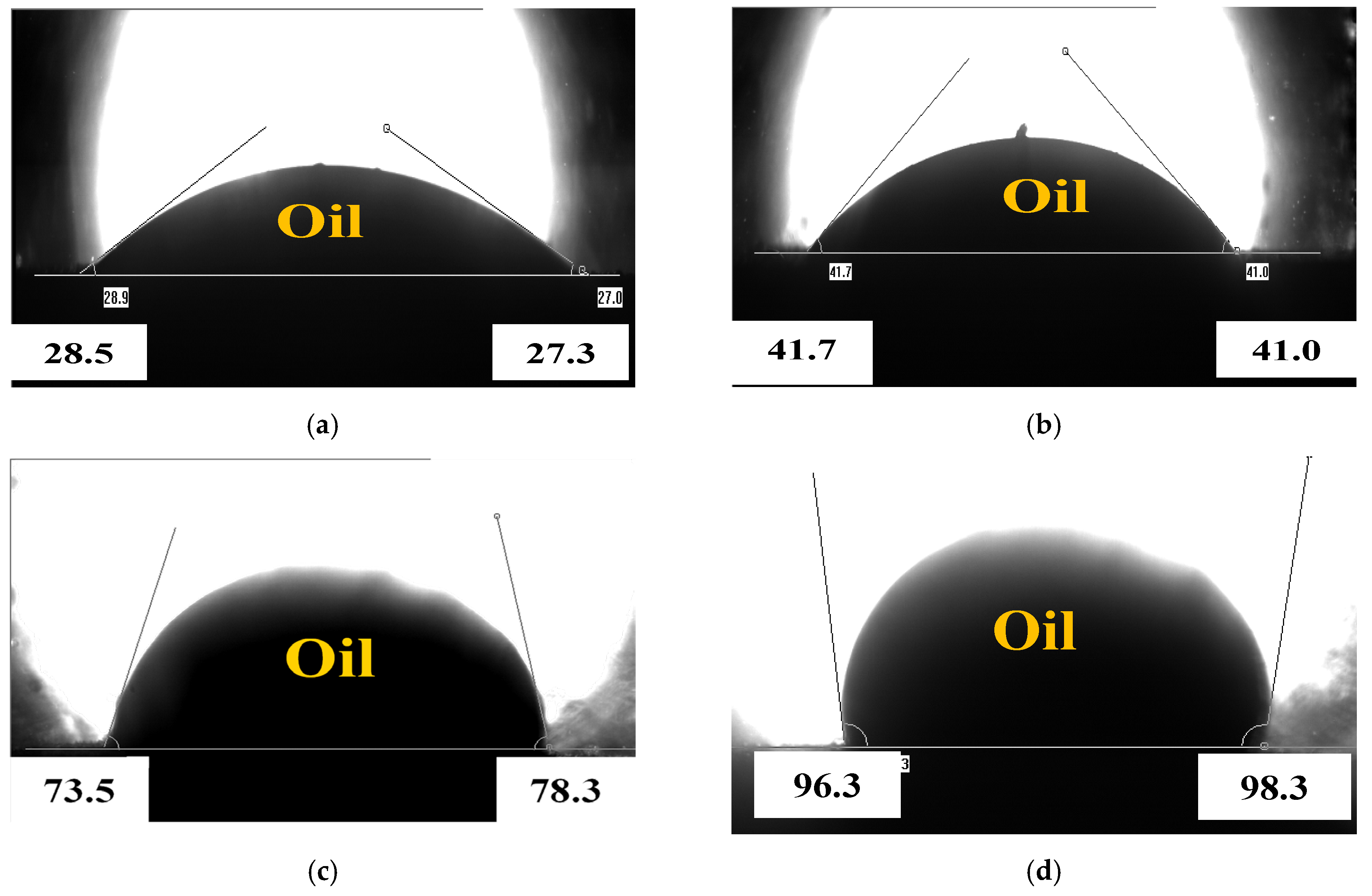

2.2.1. Wettability Contact Angle and Interfacial Tension Experiments

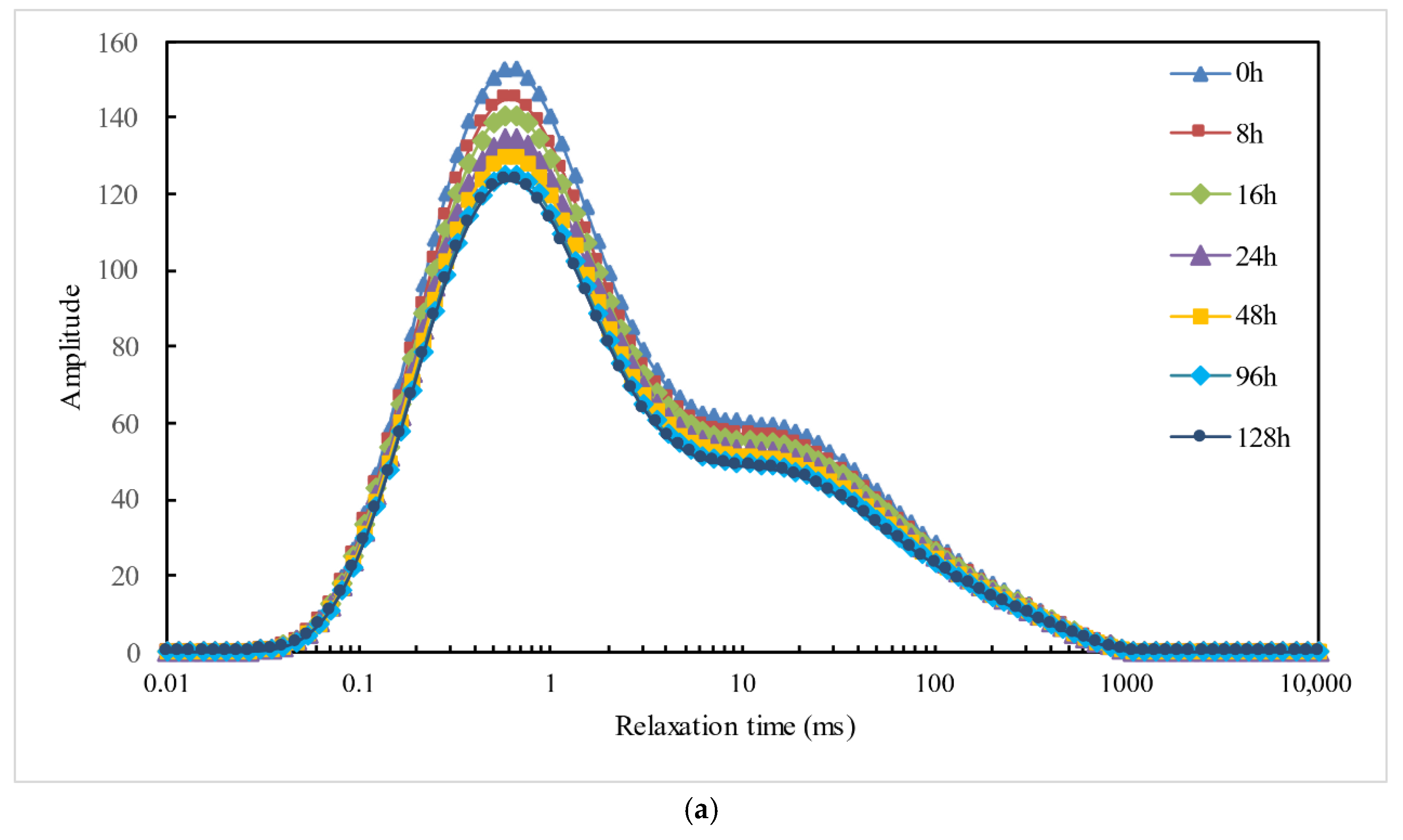

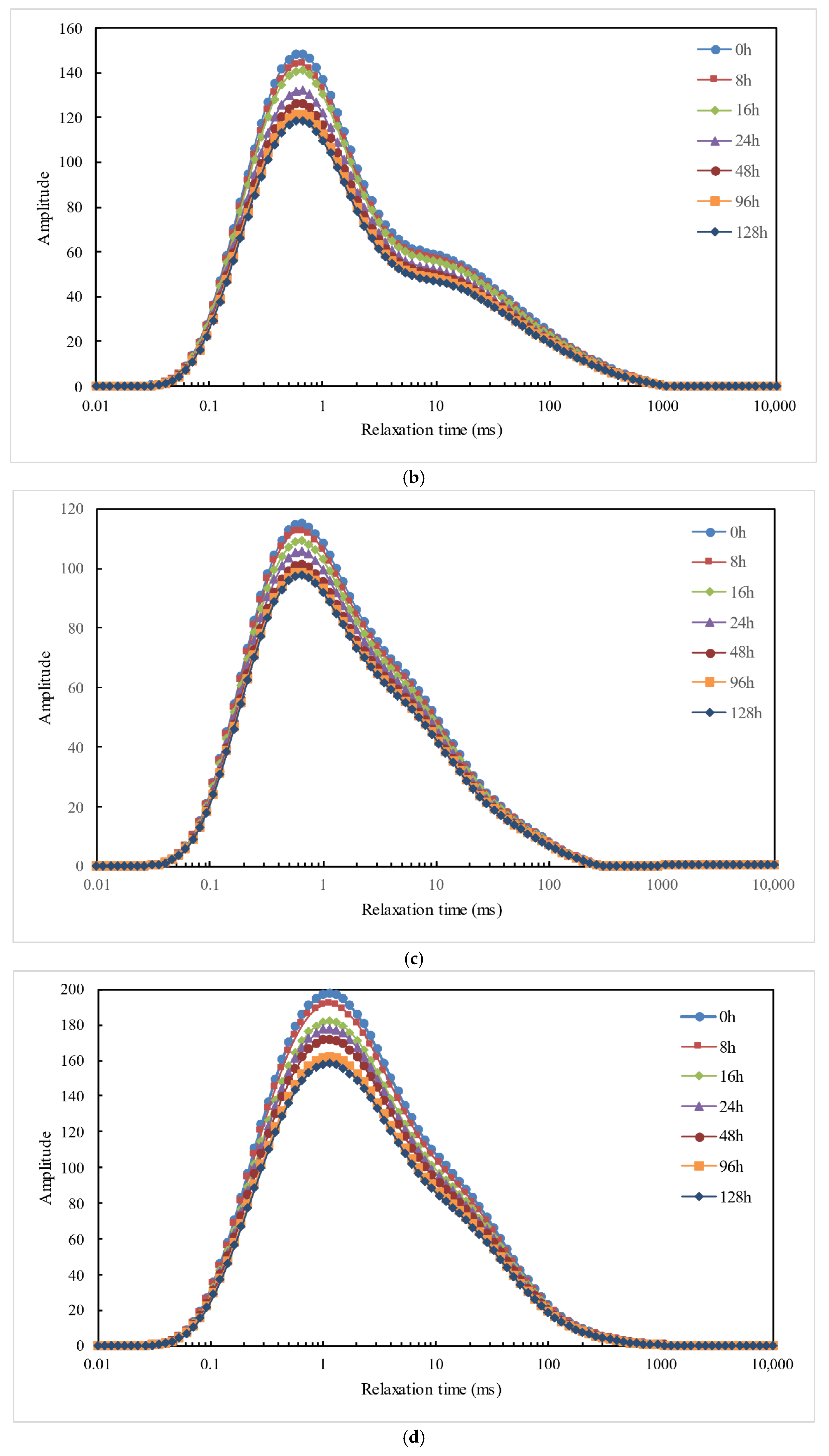

2.2.2. Imbibition Experiments and Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Experiments

- B = imbibition recovery efficiency (%)

- S0 = initial NMR T2 spectrum integral area after crude oil saturation

- Si = NMR T2 spectrum integral area at imbibition time

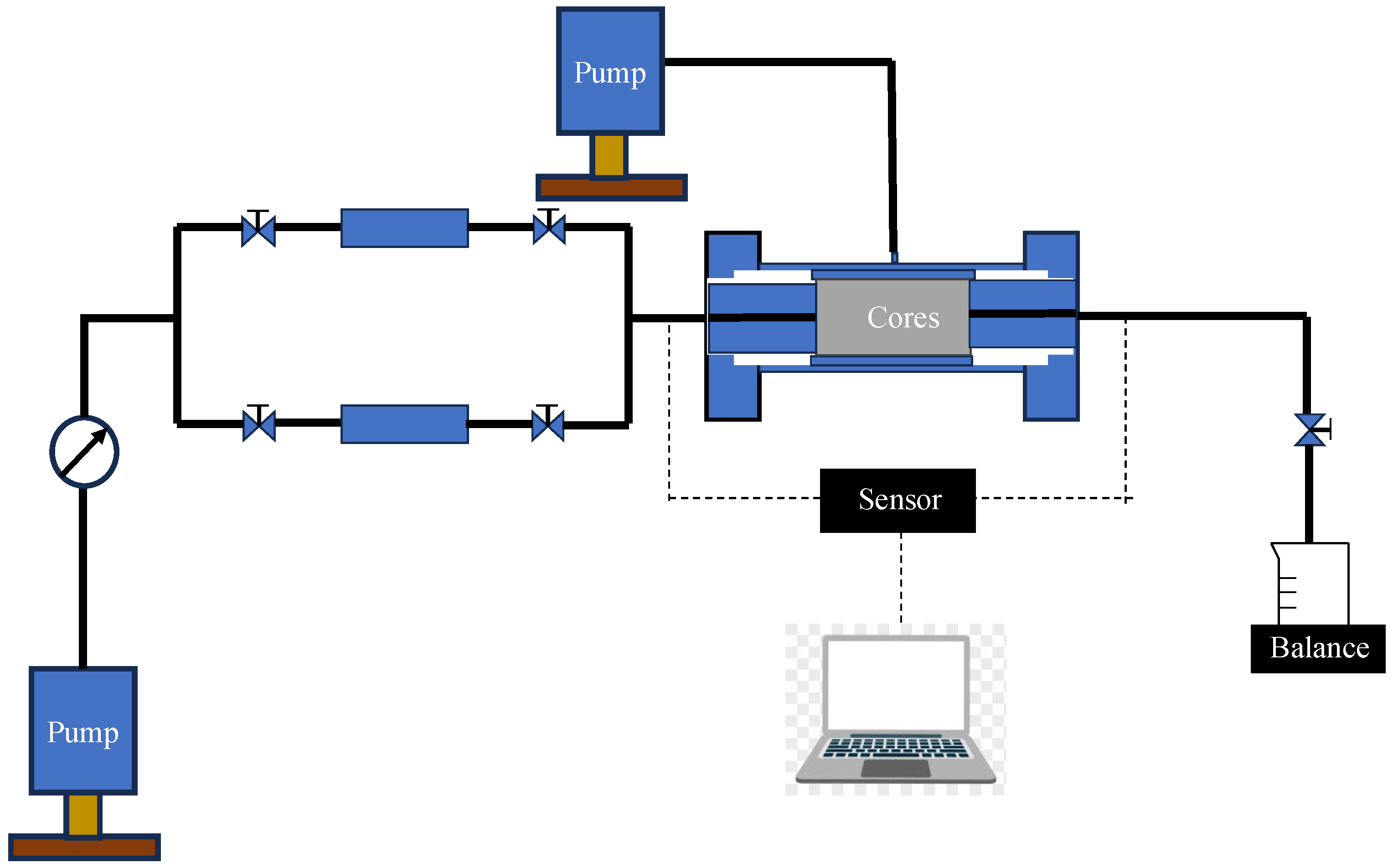

2.2.3. Relative Permeability and Oil Recovery Tests

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Results of Fracturing Fluid Evaluation in Use

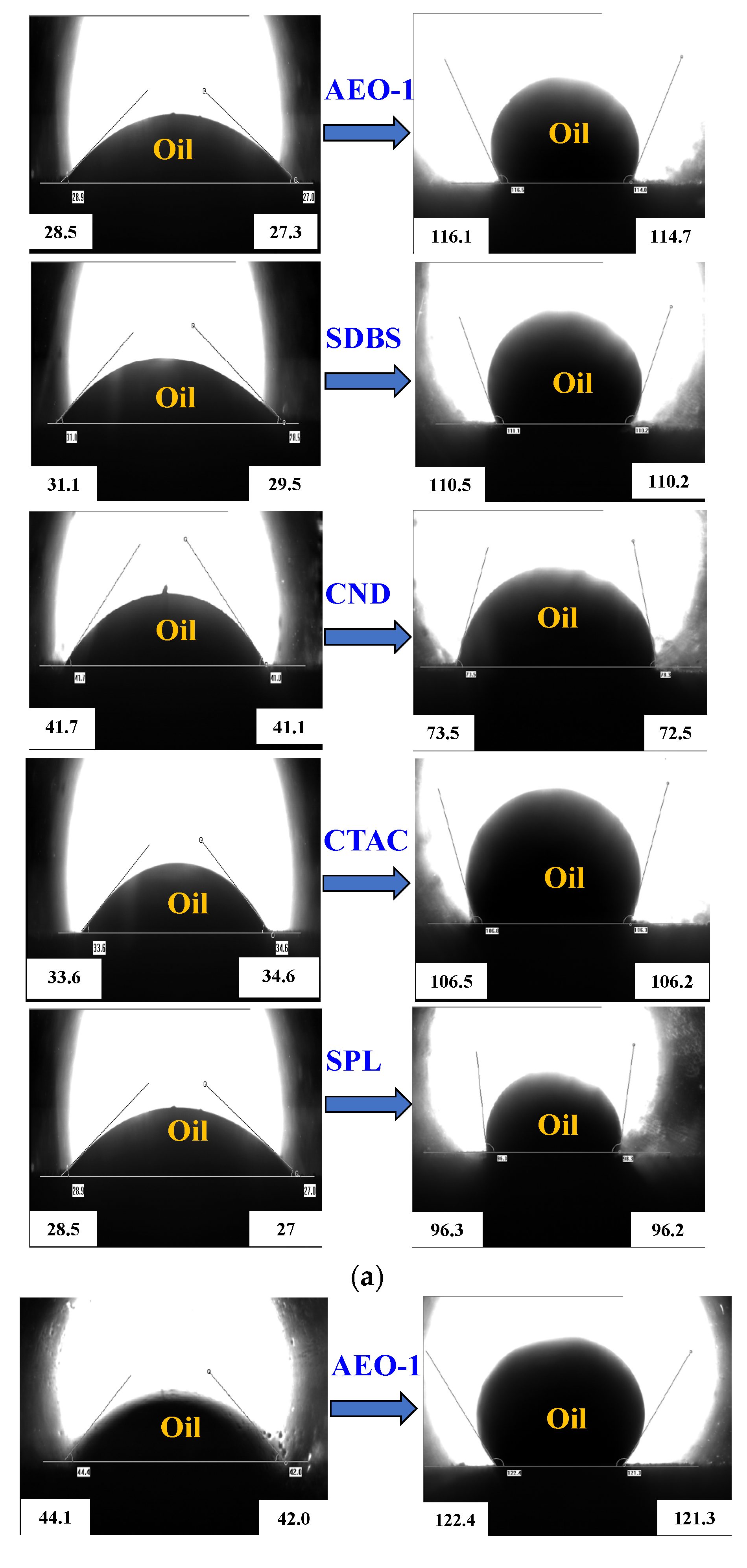

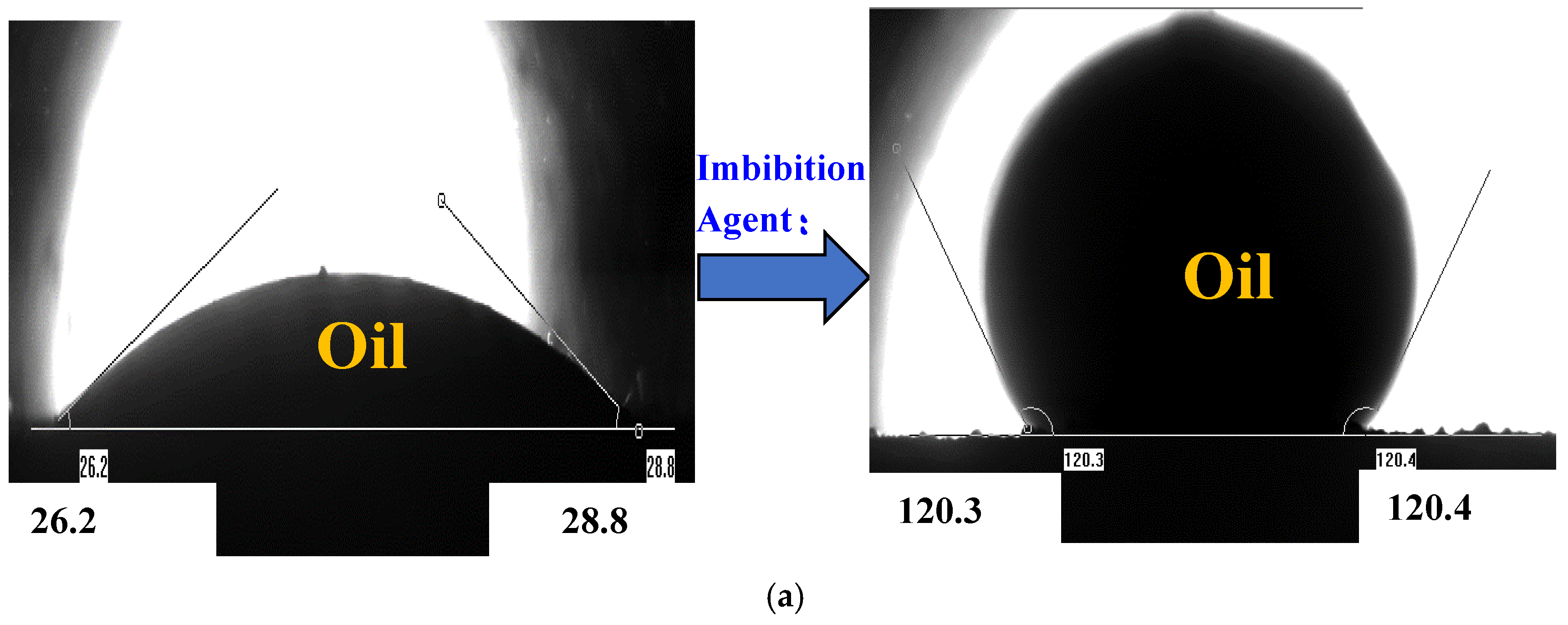

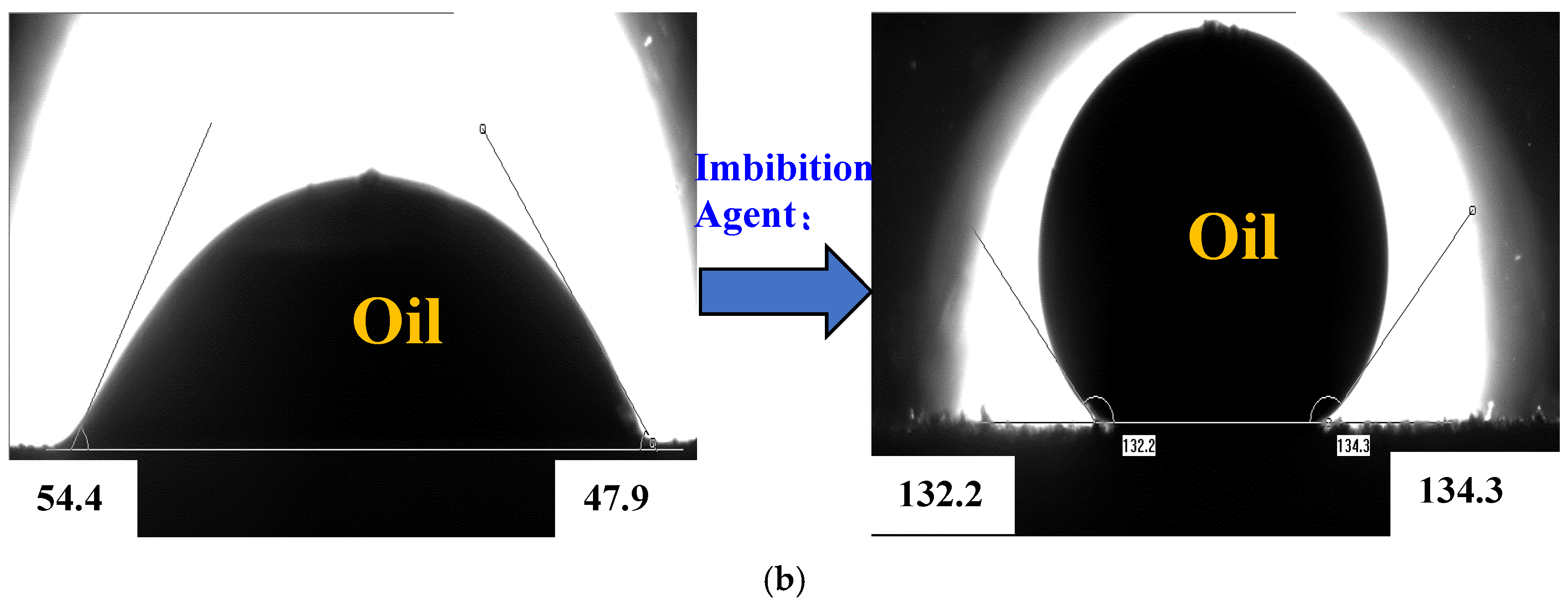

3.1.1. Wettability Modification Results

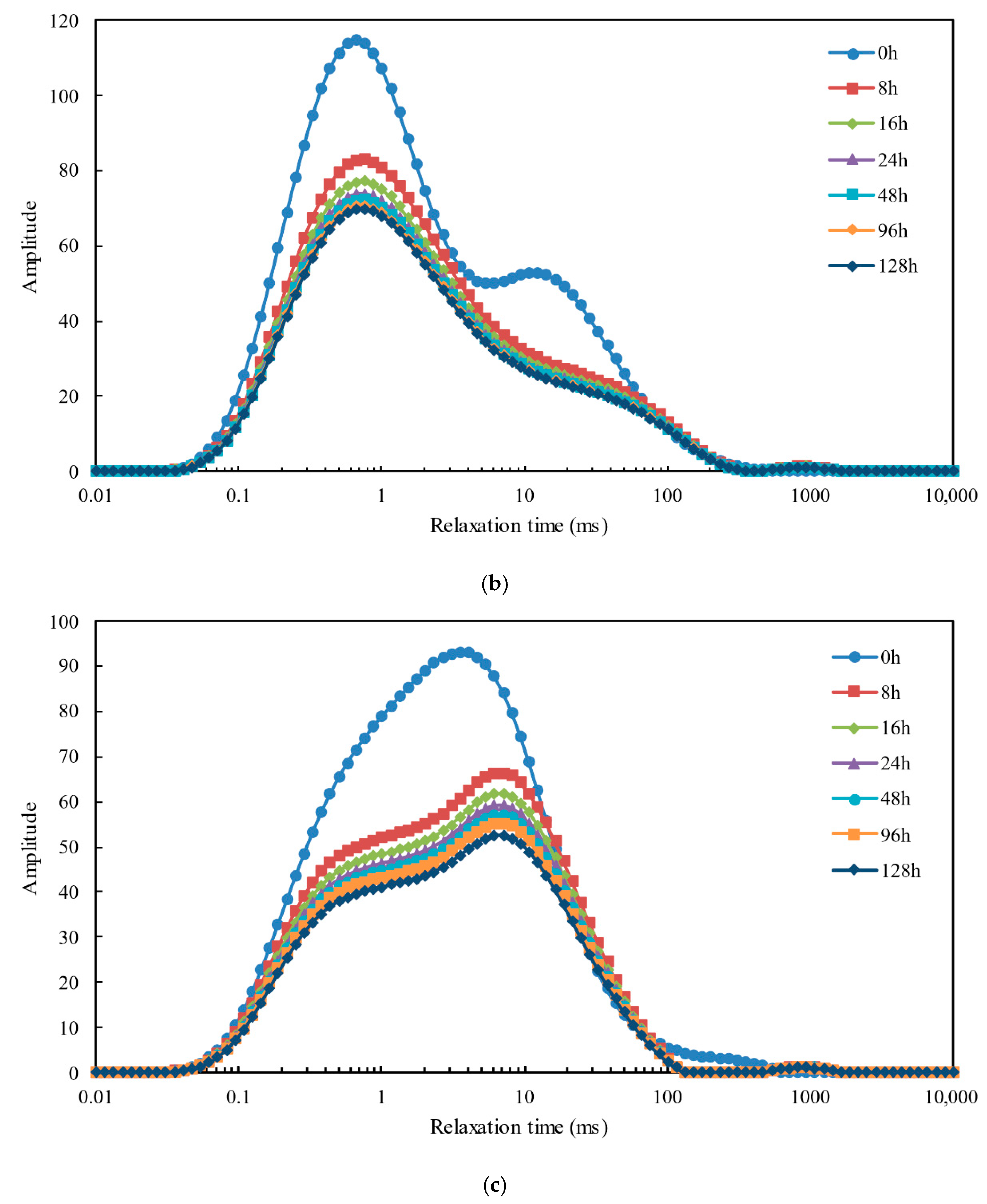

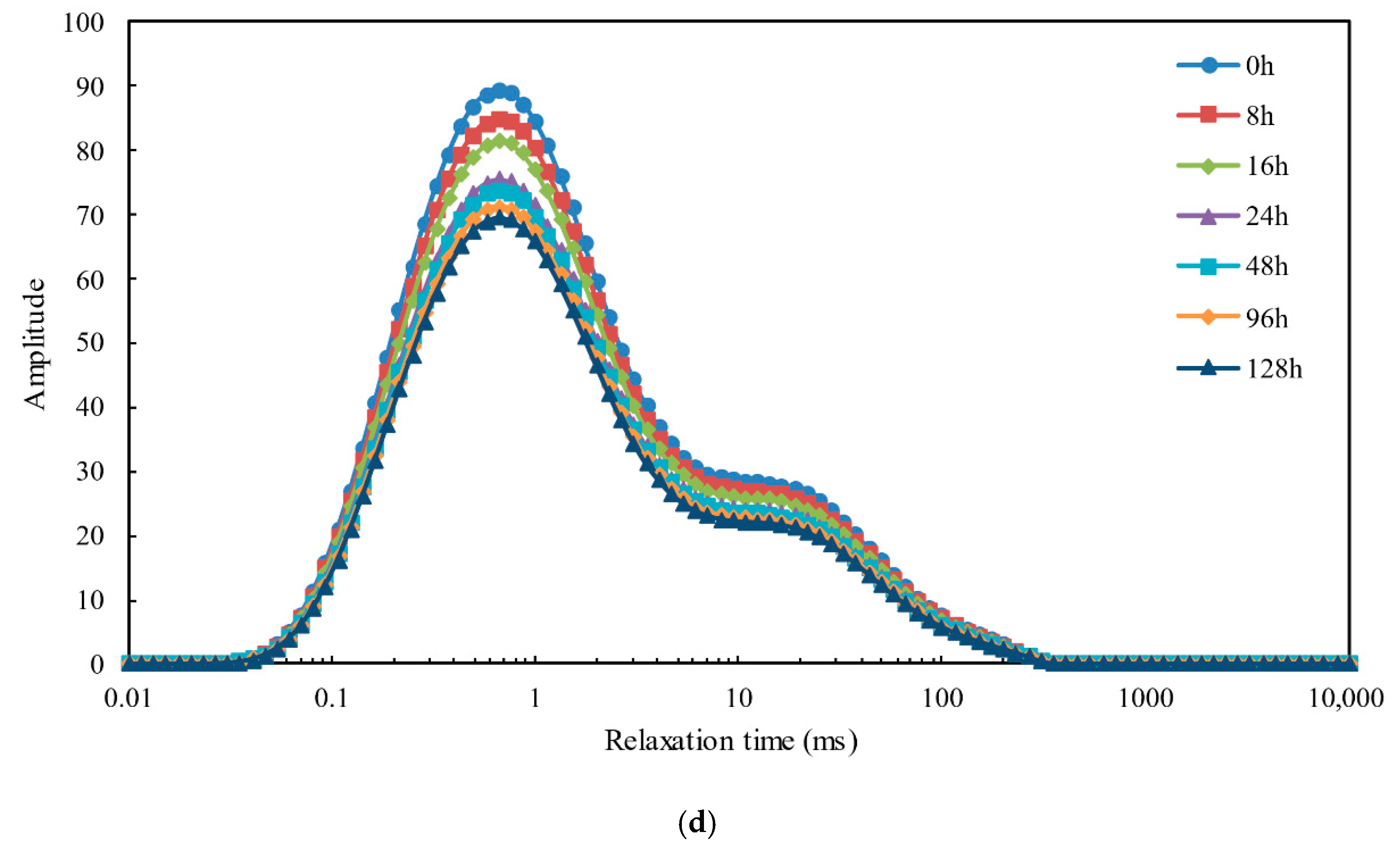

3.1.2. Spontaneous Imbibition Results

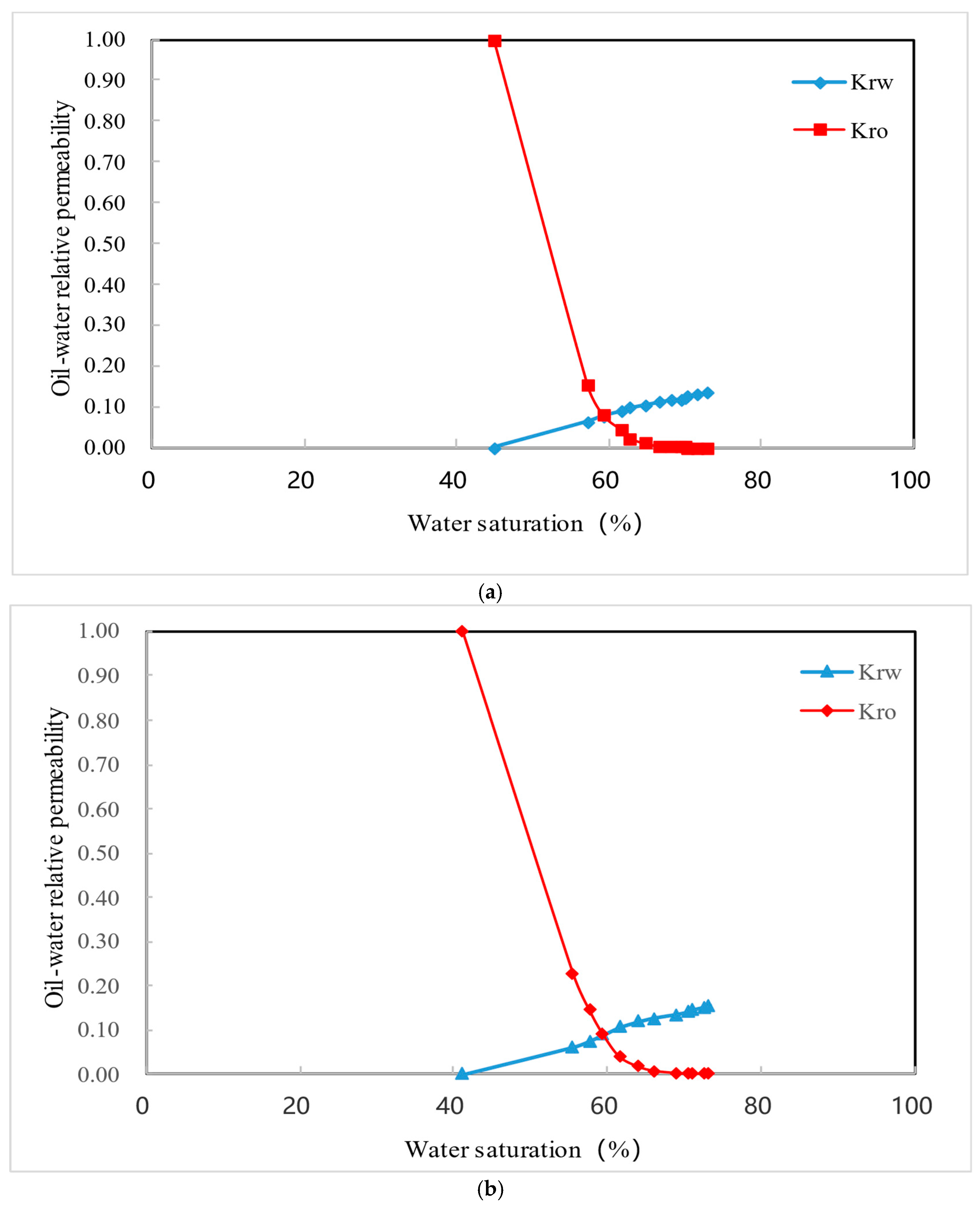

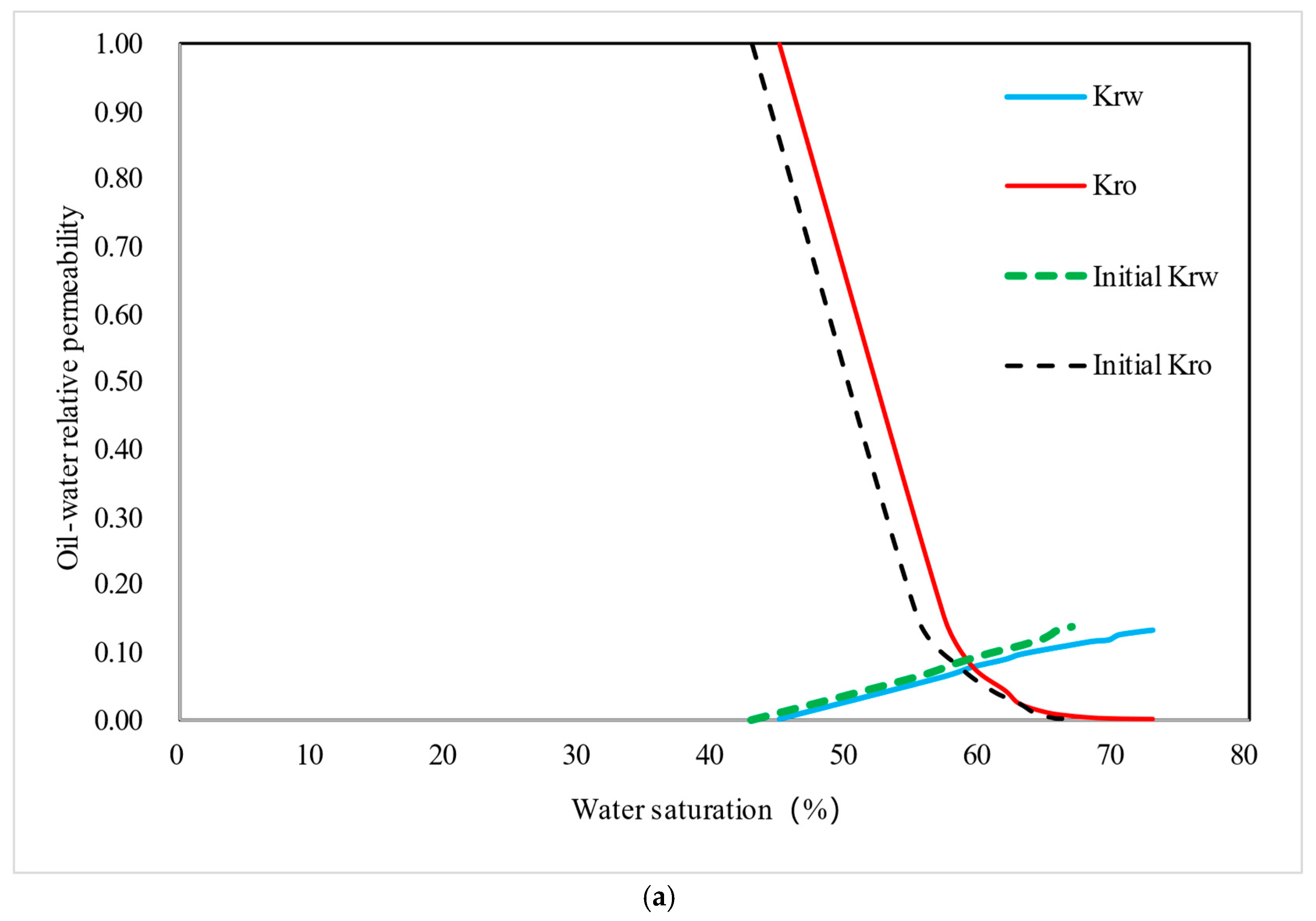

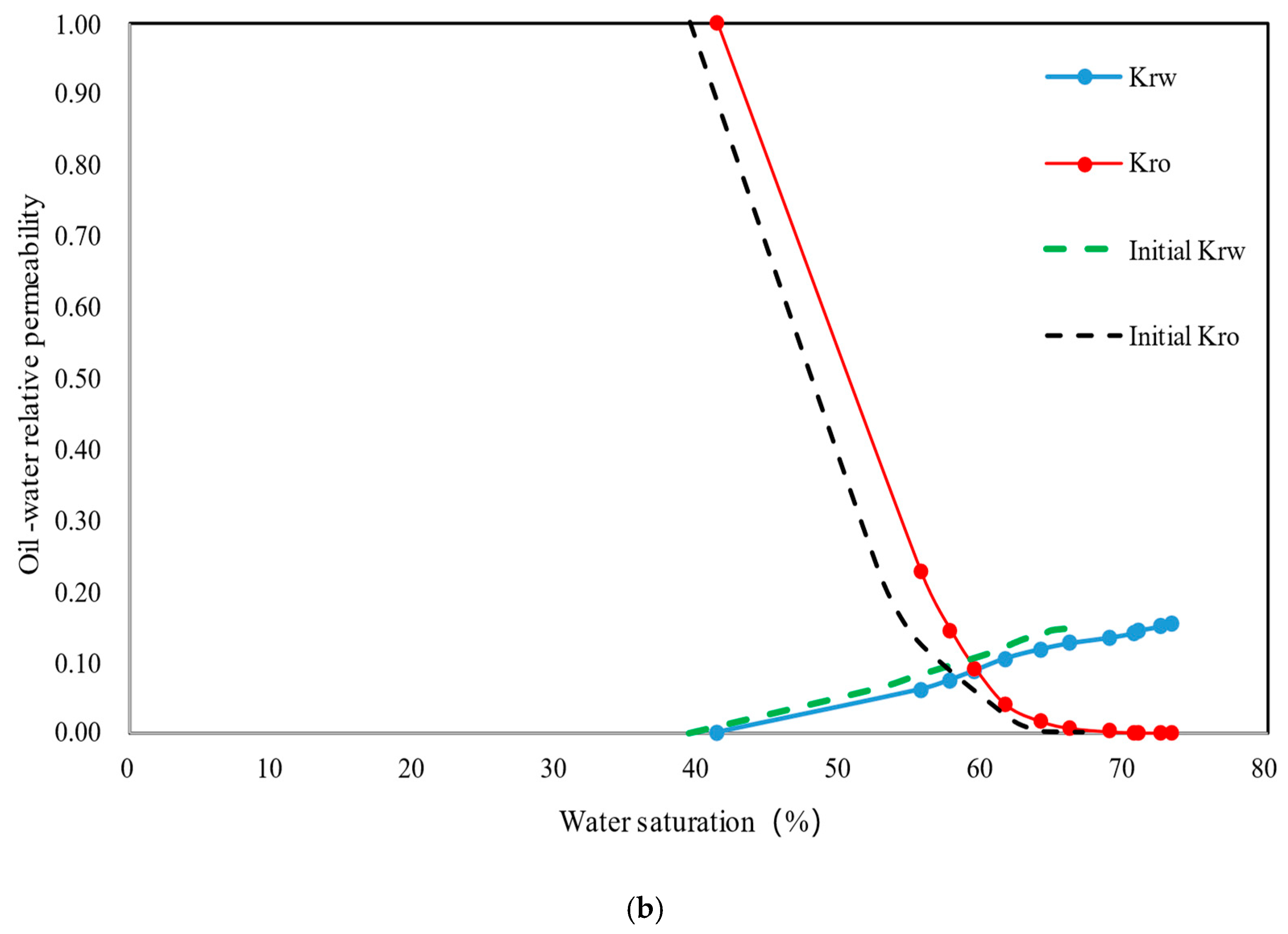

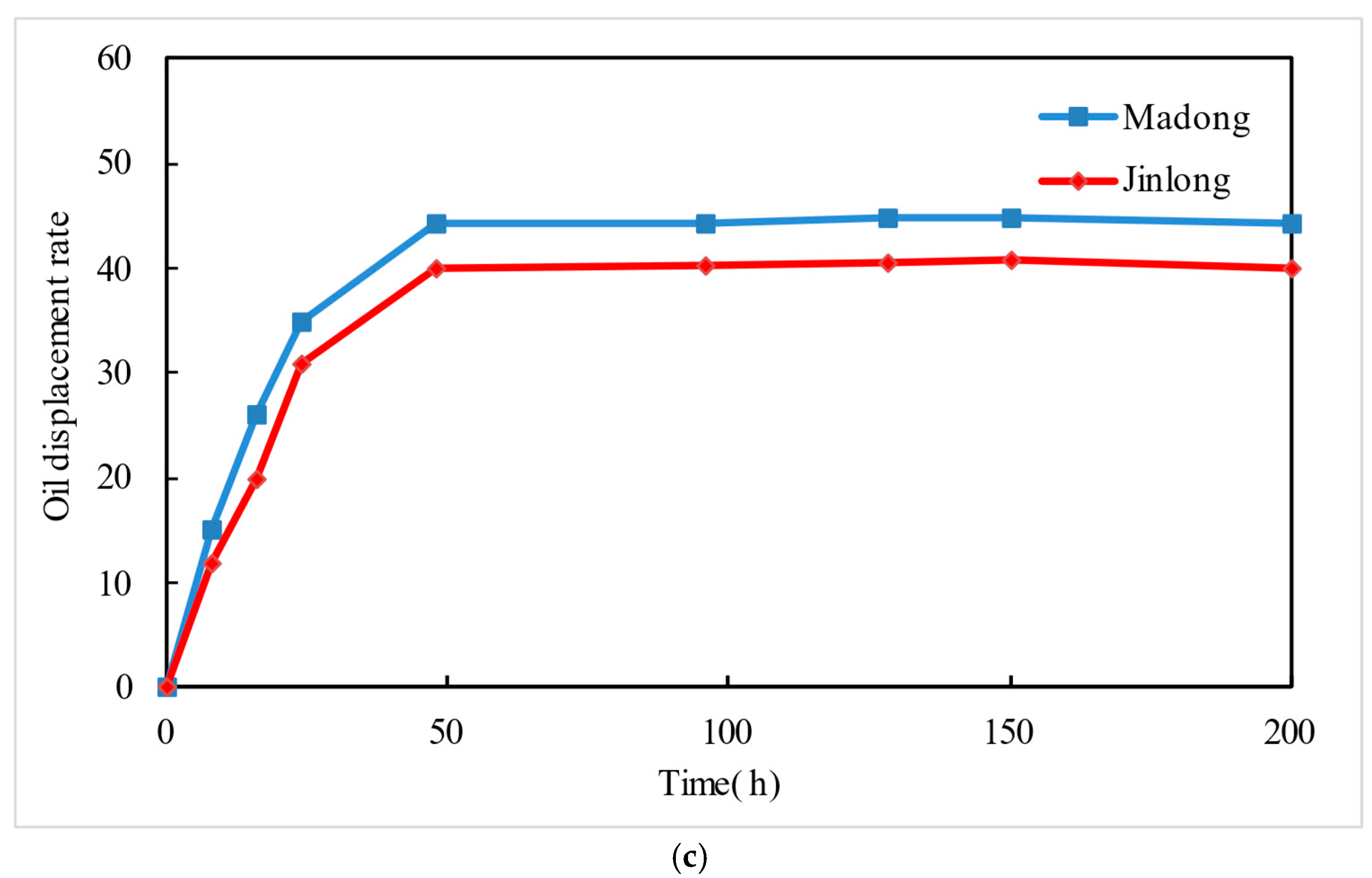

3.1.3. Relative Permeability and Oil Displacement Efficiency Analysis

3.2. Surfactant-Enhanced Oil Recovery Results

3.2.1. Wettability Modification Results

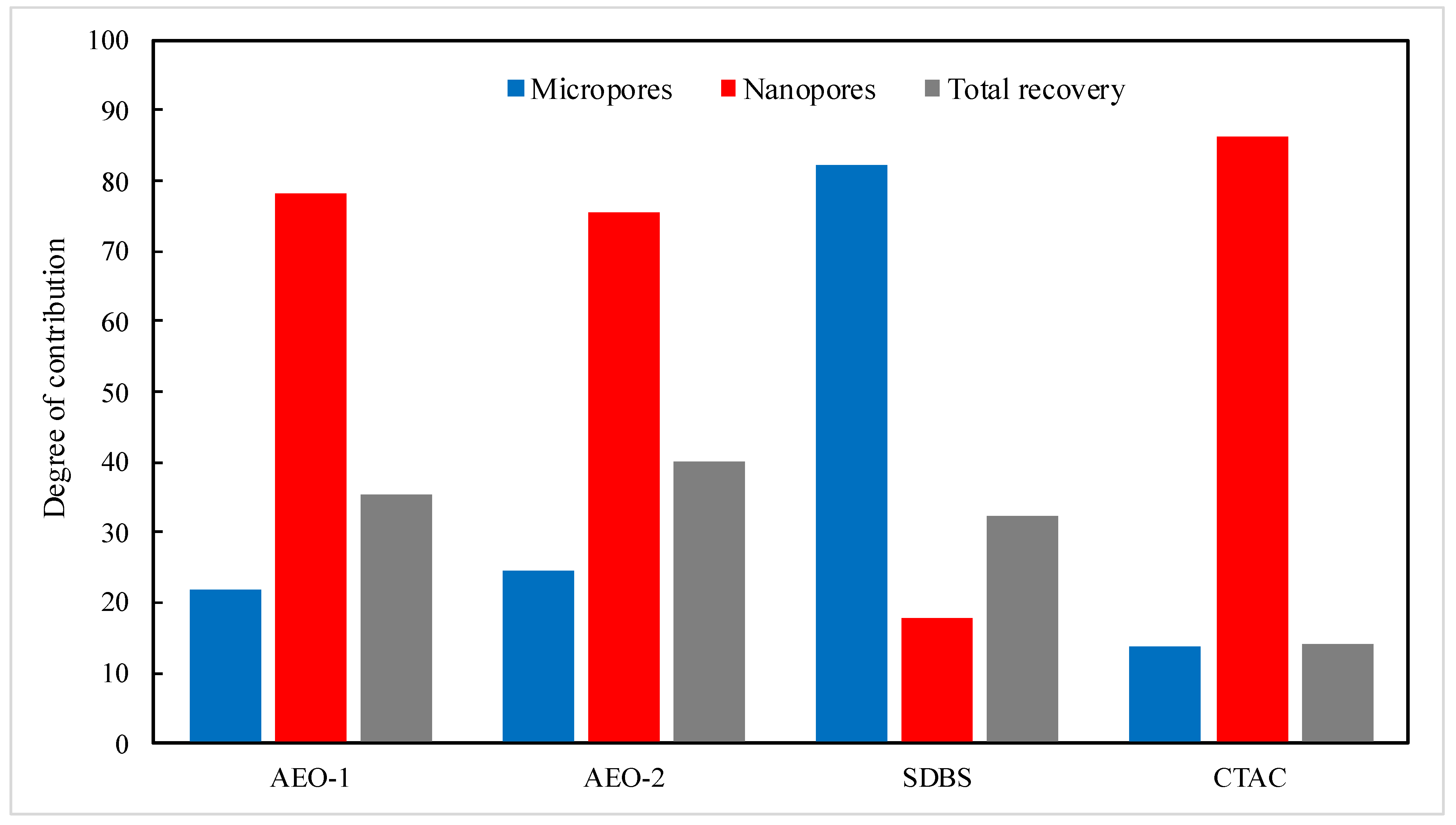

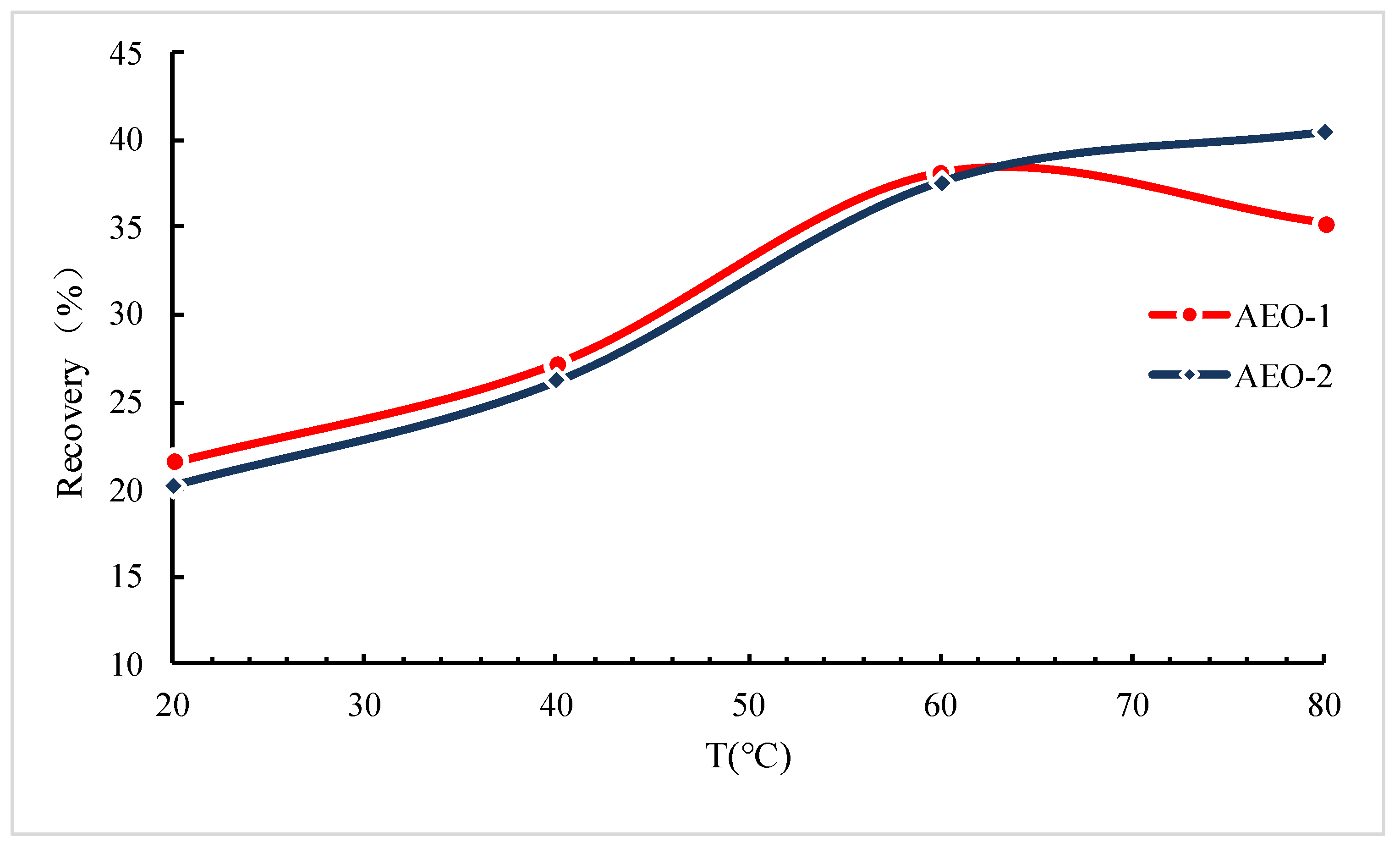

3.2.2. Imbibition Displacement Results

3.2.3. Relative Permeability and Oil Displacement Efficiency Curve Analysis

3.3. Mechanism Discussion

3.3.1. Wettability Modification Mechanism

3.3.2. Interfacial Tension (IFT) Optimization

4. Conclusions

- 1.

- Through comparative studies on different types of surfactants for enhancing crude oil mobility in tight conglomerates, non-ionic surfactant AEO-2 was found to be more suitable for low-oil-saturation reservoirs of the Wuerhe Formation in Xinjiang Oilfield. At 80 °C with 0.2% AEO-2, the imbibition recovery rate exceeds 40%, with crude oil mobilization ratios of 75.36% and 24.6% in nanopores and micropores, respectively. Nanopores serve as the primary action zone for crude oil displacement, contributing over 70% to the recovery. The fracturing fluid formulated by compounding AEO-2 can reduce residual oil saturation by more than 6%, achieving excellent oil displacement and permeability enhancement effects.

- 2.

- For the tight conglomerate reservoirs in Xinjiang Oilfield, crude oil mobilization is difficult due to issues such as small pore throats and complex wettability. AEO-2 improves the imbibition recovery rate to 40.14% by realizing core water-wettability and optimizing interfacial tension. Studies show that the synergistic mechanism of wettability reversal and interfacial tension regulation effectively enhances crude oil mobilization efficiency in strongly heterogeneous reservoirs. The adaptability of surfactants varies across different reservoirs, and further in-depth formulation optimization research should be conducted, targeting the physical properties of conglomerate and sandstone reservoirs.

- 3.

- This study provides insights into enhanced oil recovery (EOR) from tight glutenite reservoirs. Given that tight conglomerate reservoirs exhibit smaller pore sizes compared to conventional tight reservoirs, future research should focus on (1) developing nanoscale materials (e.g., nanoemulsions) tailored for nanopore confinement and (2) expanding beyond conventional wettability alteration and imbibition recovery mechanisms to systematically investigate other oil mobility enhancement mechanisms (including but not limited to nano-driving effects and structural disjoining pressure). This will establish a synergistic approach for improving oil recovery in tight conglomerates.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Soeder Daniel, J. The successful development of gas and oil resources from shales in North America. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2018, 163, 399–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, R.; Zou, C.; Mao, Z.; Yang, H.; Hui, X.; Wu, S.; Cui, J.; Su, L.; Li, S.; Yang, Z. Characteristics and distribution of continental tight oil in China. J. Asian Earth Sci. 2019, 178, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Qin, J.; Xian, C.; Fan, X.; Zhang, J.; Ding, Y. Theoretical understandings, key technologies and practices of tight conglomerate oilfield efficient development: A case study of the Mahu oilfield, Junggar Basin, NW China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2020, 47, 1275–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, W.; Lu, S.; Huang, W.; Wang, S.; Gao, Y.; Wang, W.; Li, J.; Xu, J.; Zhan, Z. Study on the full-range pore size distribution and the movable oil distribution in glutenite. Energy Fuels 2019, 33, 7028–7042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, T.; Zhang, J.; Dong, Y. Microscopic mobility of crude oil in tight conglomerate reservoirs in Mahu Sag under different development methods. Xinjiang Pet. Geol. 2024, 45, 327–333. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, Y. Optimization and Application of Differential Transformation Technology for Deep Gravel Reservoirs. Petrochem. Technol. 2024, 31, 231–233. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, W.; Lu, S.; Zhang, J.; Gao, Y.; Huang, W.; Wen, Z.; Li, J.; Li, J. NMR characterization of fluid mobility in low-permeability conglomerates: An experimental investigation of spontaneous imbibition and flooding. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2022, 214, 110483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, H.; Zhou, F.; Liu, X.; Ding, Z.; Zhang, S.; Li, F.; Xie, W.; Wang, Y.; Dong, Y.; Yao, E. Crude oil mobilization enhanced by nano-emulsion in the full fracturing process for tight oil reservoirs. Phys. Fluids 2025, 37, 73640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, Y.; Liu, Y.; He, Y.; Wang, L.; Guo, B.; Li, G.; Du, Z. Impacts of mineralogy and pore structure on spontaneous imbibition in tight glutenite reservoirs. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2023, 227, 211943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, F.Q.; Ma, C.M.; Zhang, X.Y.; Zhang, J.G.; Tan, L.; Zhao, D.D.; Li, X.K.; Jing, Y.Q. Migration rule of crude oil in microscopic pore throat of the low-permeability conglomerate reservoir in Mahu sag, Junggar Basin. Energies 2022, 15, 7359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Yu, H.; Tang, H.; Huang, T.; Zeng, H.; Wang, Y. Mechanisms of Imbibition Diffusion and Recovery Enhancing of Fracturing Fluids in Tight Reservoirs. Energy Fuels 2024, 38, 12684–12699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, M.; Zang, C.; Li, J.; Mou, X.; Wang, R.; Li, H.; Li, J. An Experimental Investigation into the Role of an In Situ Microemulsion for Enhancing Oil Recovery in Tight Formations. Energies 2024, 17, 1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, D.; Ding, C.; Li, J.; Jiang, S. Stripping Mechanism of Surfactant System Based on Residual Oil on the Surface of Sand-Conglomerate Rocks with Different Grain Size Mineral Compositions. Molecules 2024, 29, 1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, H.; Shi, J.; Wu, M.; Zhou, F.; Zhang, J.; Peng, Y.; Yu, T.; Pan, Z. Experimental Study on the Mechanism of Enhanced Imbibition with Different Types of Surfactants in Low-Permeability Glutenite Reservoirs. Molecules 2024, 29, 5953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Li, Y.; Lv, J.; Cheng, H.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Z.; Chen, C. Pore-Scale Investigation on Mobilization Mechanism of Chemical Flooding for Conglomerate Reservoir. In Offshore Technology Conference Asia; OTC: New York, NY, USA, 2020; p. D011S008R002. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, X.; Tian, Y.; Shi, Y.; Wang, X.; Leng, R.; Zheng, H.; Liang, B.X.; Zhao, S. Research on the main controlling factors and preferred formulations for chemical oil recovery in conglomerate reservoirs based on complex lithology. Geomech. Geophys. Geo-Energy Geo-Resour 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Deng, Y.; Qin, J.; Zhang, J.; Zou, Y.; Zhang, S.; Liu, S. Fracture propagation mechanism of tight conglomerate reservoirs in Mahu Sag. Processes 2023, 11, 1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Zhao, A.; Wei, Y. The dominant mineralogical triggers hindering the efficient development of the world’s largest conglomerate oilfield. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2024, 60, 688–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Gao, J.; Chang, S.; Wan, Q.; Liu, C. Study on Fracture Conductivity of Mahu Sandy Conglomerate Tight Oil Reservoir. In SPE Asia Pacific Oil and Gas Conference and Exhibition; SPE: Tulsa, OK, USA, 2021; p. D012S032R043. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, H.; Zhou, F.; Wu, J.; Zhang, K.; Ding, Z.; Xu, H.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, M.; Yao, E. The mobilization mechanism of low oil saturation reservoirs. Phys. Fluids 2024, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Degang, L.; Auricchio, G.; Schmidt, V.K.d.O.; Della-Flora, I.K.; de Andrade, C.J. Oil displacement properties of surfactin: A comparative study. Tenside Surfactants Deterg. 2023, 60, 414–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Shi, S.; Zheng, Z.; Ji, Y.; Wang, L. The practice of geology-engineering integration in the development of horizontal wells in tight conglomerate in Mahu Sag. China Pet. Explor. 2018, 23, 90–103. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, A.; Du, S. Hydration-induced damage of tight conglomerates. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 495, 153426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, S.; Zhao, A.; Zhou, W.; Wei, Y. Elemental and mineralogical mechanisms controlling the storage and flow performances of tight conglomerates. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2024, 65, 479–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, H.; Zhou, F.; Wu, J.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, K.; Xu, H.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Yao, E. Feasibility study of crude oil mobilizing with nano emulsion in low oil saturation reservoir. Geoenergy Sci. Eng. 2024, 232, 212408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sing, K.S.W.; Everett, D.H.; Haul, R.A.W.; Moscou, L.; Pierotti, R.A.; Rouquerol, J.; Siemieniewska, T. Reporting physisorption data for gas/solid systems with special reference to the determination of surface area and porosity. Pure Appl. Chem. 1985, 57, 603–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Fan, X.; Gao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wu, S.; Tian, J.; He, J. Evaluation of Original Oil Saturation in MH Depressed W Group Gravel Reservoir Based on Logging. Block Oil Gas Fields 2021, 28, 509–513. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Sheng, J.J.; Wang, X.; Ge, H.; Yao, E. Experimental study of wettability alteration and spontaneous imbibition in Chinese shale oil reservoirs using anionic and nonionic surfactants. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2019, 175, 624–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, H.; Zhou, F.; Zhang, M.; Gao, X.; Xu, H.; Yao, E.; Wang, J.; Li, Y. Optimization and friction reduction study of a new type of viscoelastic slickwater system. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 344, 117876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Huiqing, L.; Genbao, Q.; Yongcan, P.; Yang, G. Investigations on spontaneous imbibition and the influencing factors in tight oil reservoirs. Fuel 2019, 236, 755–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Li, J.; Liang, B.; Liu, J.; Sun, W.; He, J.; Lei, Y. Complex wettability behavior triggering mechanism on imbibition: A model construction and comparative study based on analysis at multiple scales. Energy 2023, 275, 127434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Bai, B.; Wu, H.; Hou, J.; Meng, Z.; Sun, R.; Li, Z.; Lu, Y.; Kang, W. Mechanisms of imbibition enhanced oil recovery in low permeability reservoirs: Effect of IFT reduction and wettability alteration. Fuel 2019, 244, 110–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Lai, F.; Fu, Y.; Li, Z.; Wang, Q. Coupling the Dynamic Contact Angle into the Dynamic Imbibition Model for Fractal Porous Media. Energy Fuels 2023, 37, 7201–7212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Well No. | No. | Formation | Length | Diameter | Porosity | Pore Volume | Permeability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (cm) | (cm) | (%) | (cc) | (10−3 μm2) | |||

| Ma 211 | 1 | P2w43 | 5 | 2.5 | 9.51 | 2.333 | 0.0076 |

| 2 | P2w43 | 5 | 2.5 | 13.65 | 3.35 | 0.0067 | |

| 3 | P2w43 | 5 | 2.5 | 9.51 | 2.33 | 0.025 | |

| 4 | P2w43 | 5 | 2.5 | 8.93 | 2.19 | 0.0072 | |

| 5 | P2w43 | 5 | 2.5 | 9.28 | 2.27 | 0.0075 | |

| Jin 222 | 6 | P3w | 5 | 2.5 | 12.088 | 2.967 | 0.091 |

| 7 | P3w | 5 | 2.5 | 14.13 | 3.468 | 0.056 | |

| 8 | P3w | 5 | 2.5 | 14.252 | 3.498 | 0.045 | |

| Jin 214 | 9 | P3w | 5 | 2.5 | 9.74 | 2.39 | 0.086 |

| 10 | P3w | 5 | 2.5 | 14.98 | 3.68 | 0.067 | |

| 11 | P3w | 5 | 2.5 | 11.49 | 2.82 | 0.072 |

| Sample No. | Quartz (%) | Plagioclase (%) | Calcite (%) | Siderite (%) | Laumontite (%) | Anhydrite (%) | Goethite (%) | Clay Minerals (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ma 211 | 52.6 | 13.7 | 1.9 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 31.8 |

| Jin 222 | 31.3 | 29.6 | 1.6 | 0 | 5.0 | 6.9 | 0 | 25.6 |

| Jin 214 | 26.1 | 24.0 | 3.1 | 2.7 | 9.9 | 3.4 | 4.8 | 26.0 |

| Sample No. | Illite/Smectite Mixed Layer (%) | Illite (%) | Chlorite (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ma 211 | 59 | 18 | 23 |

| Jin 222 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| Jin 214 | 0 | 0 | 100 |

| Surfactants | AEO-2 | CND | SDBS | CTAC | SPL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface tension (mN/m) | 29.8 | 31.43 | 32.41 | 37.19 | 39.4 |

| Interfacial tension(mN/m) | 0.64 | 0.28 | 0.66 | 1.31 | 3.79 |

| Oil recovery rate (%) | 40.14 | 25.2% | 32.28 | 14.2 | / |

| Core ID | Length (cm) | Diameter (cm) | Porosity (%) | Permeability (mD) | Oil Viscosity (mPa·s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5 | 2.5 | 12.451 | 0.0112 | 12.28 |

| 2 | 5 | 2.5 | 13.476 | 0.0241 | 12.28 |

| 3 | 5 | 2.5 | 12.91 | 0.0462 | 12.28 |

| 4 | 5 | 2.5 | 11.473 | 0.0183 | 12.28 |

| 5 | 5 | 2.5 | 16.285 | 0.0763 | 12.28 |

| 6 | 5 | 2.5 | 14.552 | 0.0656 | 12.28 |

| Core ID | Surfactant Type | Temperature (°C) | Concentration | Imbibition Recovery (%) | Wettability Alteration Degree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | AEO-1 | 80 | 0.10% | 33.21 | 78 |

| 2 | AEO-2 | 80 | 0.10% | 39.19 | / |

| 3 | SDBS | 80 | 0.10% | 32.21 | 65 |

| 4 | CTAC | 80 | 0.10% | 12.38 | 71 |

| 5 | AEO-2 | 80 | 0.20% | 40.55 | 94 |

| 6 | AEO-2 | 80 | 0.30% | 36.78 | / |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, J.; Zhang, S.; Feng, Y.; Liu, J.; Bai, H.; Li, Z.; Yao, E.; Zhou, F. Mechanistic Evaluation of Surfactant-Enhanced Oil Mobility in Tight Conglomerate Reservoirs: A Case Study of Mahu Oilfield, NW China. Fuels 2025, 6, 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/fuels6040093

Zhang J, Zhang S, Feng Y, Liu J, Bai H, Li Z, Yao E, Zhou F. Mechanistic Evaluation of Surfactant-Enhanced Oil Mobility in Tight Conglomerate Reservoirs: A Case Study of Mahu Oilfield, NW China. Fuels. 2025; 6(4):93. https://doi.org/10.3390/fuels6040093

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Jing, Sai Zhang, Yueli Feng, Jianxin Liu, Hao Bai, Ziliang Li, Erdong Yao, and Fujian Zhou. 2025. "Mechanistic Evaluation of Surfactant-Enhanced Oil Mobility in Tight Conglomerate Reservoirs: A Case Study of Mahu Oilfield, NW China" Fuels 6, no. 4: 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/fuels6040093

APA StyleZhang, J., Zhang, S., Feng, Y., Liu, J., Bai, H., Li, Z., Yao, E., & Zhou, F. (2025). Mechanistic Evaluation of Surfactant-Enhanced Oil Mobility in Tight Conglomerate Reservoirs: A Case Study of Mahu Oilfield, NW China. Fuels, 6(4), 93. https://doi.org/10.3390/fuels6040093