Parental Stress and Child Quality of Life after Pediatric Burn

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Measures

- Did you see the incident (accident) in which your child got hurt?

- When your child was hurt (or when you first heard it had happened) did you feel really helpless, like you wanted to make it stop but could not?

- Were you with your child in the ambulance or helicopter on the way to the hospital?

- Does your child have any behavior problems or problems paying attention?

2.2. Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Patient and Family Characteristics

3.2. Clinical Characteristics of the Burn Assessment

3.3. Event Questions for Parents

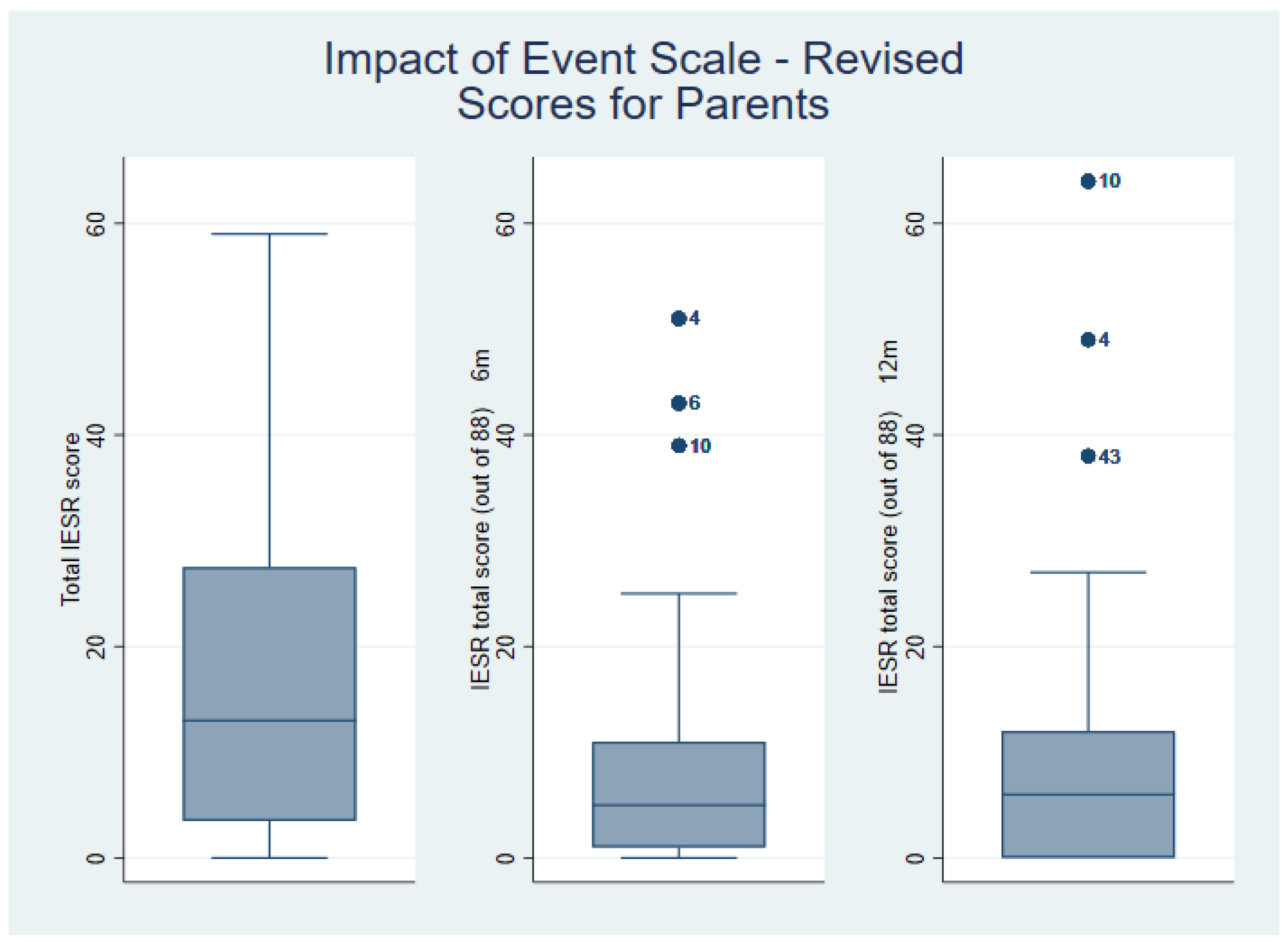

3.4. Impact of Event Scale-Revised

3.5. Parent CARe Burn Scale

3.6. Post-Traumatic Growth Scores for Parents

3.7. Patient-Reported and Parent-Reported Psychosocial Quality of Life Scores

3.8. Regression Analyses

3.8.1. Univariate Analyses for Potential Covariates for Model Assessing Parental Post-Traumatic Stress Symptoms

3.8.2. Multivariate Analysis—Explanatory Factors for Early Parental Post-Traumatic Stress Symptoms

3.8.3. Multivariate Analysis—Explanatory Factors for Longer-Term Parental Post-Traumatic Stress Symptoms

3.8.4. Pairwise Correlations between Parental Post-Traumatic Stress Symptoms and Parental QoL

3.8.5. Pairwise Correlations between Parental Post-Traumatic Stress Symptoms and Child QoL

4. Discussion

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Woolard, A.; Hill, N.; McQueen, M.; Martin, L.; Milroy, H.; Wood, F.; Bullman, I.; Lin, A. The psychological impact of paediatric burn injuries: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duke, J.; Randall, S.; Vetrichevvel, T.; McGarry, S.; Boyd, J.; Rea, S.; Wood, F. Long-term mental health outcomes after unintentional burns sustained during childhood: A retrospective cohort study. Burn. Trauma 2018, 6, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dahl, O.; Wickman, M.; Bjornhagen, V.; Friberg, M.; Wengstrom, Y. Early assessment and identification of posttraumatic stress disorder, satisfaction with appearance and coping in patients with burns. Burn. J. Int. Soc. Burn Inj. 2016, 42, 1678–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, M.; Holzer, C.; Richardson, L.; Epperson, K.; Ojeda, S.; Martinez, E.; Sunan, O.; Herndon, D.; Meyer, W.I. Quality of Life of Young Adult Survivors of Pediatric Burns Using World Health Organization Disability Assessment Scale II and Burn Specific Health Scale-Brief: A Comparison. J. Burn Care Res. 2015, 36, 521–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chong, H.; Quinn, L.; Cooksey, R.; Molony, D.; Jeeves, A.; Lodge, M.; Carney, B. Mortality in paediatric burns at the Women’s and Children’s Hospital (WCH), Adelaide, South Australia: 1960–2017. Burns 2020, 46, 207–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Sousa, A. Psychological Aspects of Paediatric Burns (A Clinical Review). Ann. Burn. Fire Disasters 2010, 23, 155–159. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, E.A.; De Young, A.C.; Kimble, R.; Kenardy, J.A. Review of a Parent’s Influence on Procedural Distress and Recovery. Clin. Child Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2018, 21, 224–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakker, A.; Van der Heijden, P.G.; Van Son, M.J.; Van Loey, N.E. Course of traumatic stress reactions in couples after a burn event to their young child. Health Psychol. 2013, 32, 1076–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Young, A.C.; Hendrikz, J.; Kenardy, J.A.; Cobham, V.E.; Kimble, R.M. Prospective evaluation of parent distress following pediatric burns and identification of risk factors for young child and parent posttraumatic stress disorder. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2014, 24, 9–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hawkins, L.; Centifanti, L.; Holman, N.; Taylor, P. Parental Adjustment following Pediatric Burn Injury: The Role of Guilt, Shame, and Self-Compassion. J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2019, 44, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allahham, A.; Cooper, M.; Mergelsberg, E.; Fear, M.; Martin, L.; Wood, F. A comparison of parent-reported and self-reported psychosocial function scores of the PedsQL for children with non-severe burns. Burns 2023, 49, 1122–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffiths, C.; Tollow, P.; Cox, D.; White, P.; Pickles, T.; Harcourt, D. Testing the Responsiveness of and Defining Minimal Important Difference (MID) Values for the CARe Burn Scales: Patient-Reported Outcome Measures to Assess Quality of Life for Children and Young People Affected by Burn Injuries, and Their Parents/Caregivers. Eur. Burn J. 2021, 2, 249–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cann, A.; Calhoun, L.; Tedeschi, R.; Taku, K.; Vishnevsy, T.; Triplett, K.; Danhauer, S. A short form of the Posttraumatic Growth Inventory. Anxiety Stress Coping 2010, 23, 127–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tedeschi, R.; Calhoun, L. The Posttraumatic Growth Inventory: Measuring the positive legacy of trauma. J. Trauma Stress 1996, 9, 455–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egberts, M.R.; Engelhard, I.M.; de Jong, A.E.E.; Hofland, R.G.; Van Loey, N.E. Parents’ memories and appraisals after paediatric burn injury: A qualitative study. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 2019, 10, 1615346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winston, F.K.; Kassam-Adams, N.; Garcia-Espana, F.; Ittenbach, R.; Cnaan, A. Screening risk of persistent posttraumatic stress in injured children and their parents. JAMA 2003, 290, 643–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGarry, S.; Girdler, S.; McDonald, A.; Valentine, J.; Wood, F.; Elliott, C. Paediaric medical trauma: The impact on parents of burn survivors. Burns 2013, 39, 1114–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varni, J.; Seid, M.; Kurtin, P. PedsQL 4.0: Reliability and validity if the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory version 4.0 generic core scales in healthy and patient populations. Med. Care 2001, 39, 800–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vittinghoff, E.; Glidden, D.; Shiboski, S.; McCulloch, C. Regression Methods in Biostatistics: Linear, Logistic, Survival and Repeated Methods Models, 2nd ed.; Statistics for Biology and Health; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. Stata, in Stata Statistical Software; StataCorp LP: College Station, TX, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bakker, A.; Maertens, K.J.; Van Son, M.J.; Van Loey, N.E. Psychological consequences of pediatric burns from a child and family perspective: A review of the empirical literature. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2013, 33, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rimmer, R.B.; Alam, N.B.; Sadler, I.J.; Hansen, L.; Foster, K.N.; Caruso, D.M. Burn-injured youth may be at increased risk for long-term anxiety disorders. J. Burn Care Res. 2014, 4, 154–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halim, N.; Holland, A.; McNaugh, A.; Cameron, C.; Lystad, R.; Badgery-Parker, T.; Mitchell, R. Impact of childhood burns in academic performance: A matched population-based cohort study. Arch. Dis. Child. 2023, 108, 808–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spronk, I.; Legemate, C.; Dokter, J.; Van Loey, N.E.; Van Baar, M.E.; Polinder, S. Predictors of health-related quality-of-life agter burn injuries: A systematic Review. Crit. Care 2018, 22, 160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duke, J.; Bauer, J.; Fear, M.; Rea, S.; Wood, F.; Boyd, J. Burn injury, gender and cancer risk: Population-based cohort study using data from Scotland and Western Australia. BMJ Open 2014, 4, e003845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, T.; Dimanopoulos, T.; Shoesmith, V.; Fear, M.; Wood, F.; Martin, L. Grip strength in children after non-severe burn injury. Burns 2023, 49, 924–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elrod, J.; Schiestl, C.M.; Mohr, C.; Landolt, M. Incidence, severity and pattern of burns in children and adolscents: Anepidemiological study among immigrant and Swiss patients in Switzerland. Burns 2019, 45, 1231–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holm, S.; Tell, K.; Karlsson, M.; Huss, F.; Pompermaier, L.; Elmasry, M.; Lofgren, J. Sociodemographic Patterns of Pediatric Patients in Specialised Burn Care in Sweden. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. Glob. Open 2022, 10, e426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, M.A.; Schlichting, L.E.; Rogers, M.L.; Harrington, D.T.; Vivier, P.M. Neighborhood risk: Socioeconomic status and hospital admission for paediatric burn patients. Burns 2021, 47, 1451–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rimmer, R.B.; Bay, R.C.; Alam, N.B.; Sadler, I.J.; Richey, K.J.; Foster, K.N.; Caruso, D.M.; Rosenberg, D. Measuring the Burden of Pediatric Burn Injury for Parents and Caregivers: Informed Burn Center Staff Can Help to Lighten the Load. J. Burn Care Res. 2015, 15, 421–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, K.-C. Impact of long-term outcomes on the caregivers of burn survivors. Burns 2023, 49, 317–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawrence, J.; Rosenberg, L.; Mason, S.; Fauerbach, J. Comparing parent and child perceptions of stigmatizing behavior experienced by children with burn scars. Body Image 2011, 8, 7073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, L.; Byrnes, M.; Bulsara, M.K.; McGarry, S.; Rea, S.; Wood, F. Quality of life and posttraumatic growth after adult burn: A prospective, longitudinal study. Burns 2017, 43, 1400–1410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egberts, M.R.; van de Schoot, R.; Geenen, R.; Van Loey, N.E. Parents’ posttraumatic stress after burns in their school-aged child: A prospective study. Health Psychol. 2017, 36, 419–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Egberts, M.R.; Van de Schoot, R.; Geenen, R.; Van Loey, N.E. Mother, father and child traumatic stress reactions after paediatric burn: Within-family co-occurence and parent-child discrepancies in apprisals of child stress. Burns 2018, 44, 861–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, E.A.; De Young, A.C.; Kimble, R.; Kenardy, J.A. Impact of Parental Accute Psychological Distress in Young Child Pain-Related Behaviour Through Differences in Parenting Behavior During Pediatric Wound Care. J. Clin. Psychol. Med. Settings 2019, 26, 516–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| IESR | Median (IQR) | Range |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline (4 weeks) | 13 (3.5–27.5) | 0–59 |

| 6 months | 5 (1–11) | 0–51 |

| 12 months | 6 (0–12) | 0–64 |

| CARe Domain | 6-Month Score Mean (SD) | Published Norms 6 m Mean (SD) | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parent Positive Growth | 49.5 (34.73) | 61.92 (25.16) | 0.0196 |

| Parent concerns for appearance | 55.4 (37.83) | 82.22 (25.34) | <0.0001 * |

| Parent Negative Mood Score | 54.3 (32.77) | 60.06 (12.80) | 0.2399 |

| Self Worth/Positive Mood | 56.8 (33.58) | 70.32 (19.00) | 0.0089 |

| Parent Social Situations | 57.5 (38.9) | 77.74 (28.44) | 0.0010 * |

| Parent Physical Health | 50.04 (32.29) | 69.56 (24.56) | 0.0002 * |

| Parent Partner Relationships | 61.2 (39.68) | 72.03 (24.89) | 0.0706 |

| CARe Domain | 6-Month Score Median (IQR) | 12-Month Score Median (IQR) | Wilcoxon Signed-Rank Test p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parent Positive Growth | 30 (55–75) | 55 (30–86) | 0.16 |

| Parent concerns for appearance | 61 (10–91) | 61 (30–100) | 0.07 |

| Parent Negative Mood Score | 60 (44–76) | 60 (53–85) | 0.33 |

| Parent Positive Mood Score | 66.5 (51–71) | 68 (48–80) | 0.51 |

| Parent Social Situations | 70 (11–100) | 70 (23–100) | 0.37 |

| Parent Physical Health | 54 (31–71) | 54 (31–81) | 0.39 |

| Parent Partner Relationships | 65 (28–100) | 65 (43–100) | 0.55 |

| Posttraumatic Growth Score Overall score (out of 50) | 19 (9.5–25) | 14.5 (6.5–28) | 0.22 |

| Dependent Variable | Independent Variable | Odds Ratio | Standard Error | p-Value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline IESR | Female | 1.75 | 0.498 | 0.048 | 1.004, 3.060 |

| Parent Education | overall test chi2 13.23 (2) p = 0.0013 | ||||

| some tertiary | 4.78 | 2.509 | 0.003 | 1.71, 13.36 | |

| university | 2.02 | 1.049 | 0.173 | 0.73, 5.59 | |

| Predictor 2 | 3.89 | 1.48 | <0.0001 | 1.85. 8.20 | |

| 6 month IESR | Female | 2.50 | 0.844 | 0.006 | 1.29, 4.85 |

| Other language | 2.23 | 0.726 | 0.014 | 1018, 4.22 | |

| Predictor 2 | 3.75 | 1.722 | 0.004 | 1.53, 9.23 | |

| 12 month IESR | Female | 3.15 | 1.290 | 0.005 | 1.41, 7.03 |

| Other language | 4.21 | 1.641 | <0.001 | 1.93, 9.04 | |

| Predictor 2 | 4.60 | 20,249 | 0.002 | 1.767, 11.99 | |

| 6-Month Timepoint | 6 m IESR | Parent Positive Growth | Parent Concerns for Appearance | Parent Negative Mood Score | Parent Positive Mood Score | Parent Social Situations | Parent Physical Health | Parent Partner Relationships | Post-traumatic Growth Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6-month IESR | 1 | ||||||||

| Parent Positive Growth | 0.21 | 1 | |||||||

| Parent concerns for appearance | −0.39 * | 0.52 * | 1 | ||||||

| Parent Negative Mood Score | −0.14 | 0.75 * | 0.72 * | 1 | |||||

| Parent Positive Mood Score | −0.15 | 0.75 * | 0.72 * | 0.93 * | 1 | ||||

| Parent Social Situations | −0.57 * | 0.51 * | 0.86 * | 0.74 * | 0.81 * | 1 | |||

| Parent Physical Health | −0.16 | 0.67 * | 0.63 * | 0.84 * | 0.89 * | 0.69 * | 1 | ||

| Parent Partner Relationships | −0.14 | 0.69 * | 0.65 * | 0.88 * | 0.85 * | 0.66 * | 0.76 * | 1 | |

| Post-traumatic Growth Score | 0.49 * | 0.46 * | −0.49 * | 0.22 | 0.03 | −0.51 * | 0.04 | 0.22 | 1 |

| 12-Month Timepoint | 12 m IESR | Parent Positive Growth | Parent Concerns for Appearance | Parent Negative Mood Score | Parent Positive Mood Score | Parent Social Situations | Parent Physical Health | Parent Partner Relationships | Post-traumatic Growth Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 12-month IESR | 1 | ||||||||

| Parent Positive Growth | −0.01 | 1 | |||||||

| Parent concerns for appearance | −0.34 * | 0.72 * | 1 | ||||||

| Parent Negative Mood Score | −0.27 | 0.84 * | 0.81 * | 1 | |||||

| Parent Positive Mood Score | −0.15 | 0.84 * | 0.82 * | 0.96 * | 1 | ||||

| Parent Social Situations | −0.33 * | 0.67 * | 0.89 * | 0.83 * | 0.87 * | 1 | |||

| Parent Physical Health | −0.25 | 0.79 * | 0.74 * | 0.88 * | 0.92 * | 0.79 * | 1 | ||

| Parent Partner Relationships | 0.15 | 0.84 * | 0.75 * | 0.89 * | 0.89 * | 0.71 * | 0.86 * | 1 | |

| Post-traumatic Growth Score | 0.38 * | 0.49 * | −0.34 * | 0.0425 | 0.14 | −0.28 | 0.22 | 0.35 * | 1 |

| Baseline | IESR | PedsQL PSF (Parent-scored) | PedsQL PSF (Child-scored) | |

| IESR | 1 | |||

| PedsQL PSF (Parent-scored) | −0.1281 | 1 | ||

| PedsQL PSF (Child-scored) | −0.1788 | 0.5068 * p = 0.0019 | 1 | |

| 6 m | IESR | 1 | ||

| PedsQL PSF (Parent-scored) | −0.2618 | 1 | ||

| PedsQL PSF (Child-scored) | −0.2739 | 0.6986 * p = 0.0001 | 1 | |

| 12 m | IESR | 1 | ||

| PedsQL PSF (Parent-scored) | −0.4615 * p = 0.0060 | 1 | ||

| PedsQL PSF (Child-scored) | −0.1726 | 0.4198 * p = 0.0411 | 1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Atapattu, D.; Shoesmith, V.M.; Wood, F.M.; Martin, L.J. Parental Stress and Child Quality of Life after Pediatric Burn. Eur. Burn J. 2024, 5, 77-89. https://doi.org/10.3390/ebj5020007

Atapattu D, Shoesmith VM, Wood FM, Martin LJ. Parental Stress and Child Quality of Life after Pediatric Burn. European Burn Journal. 2024; 5(2):77-89. https://doi.org/10.3390/ebj5020007

Chicago/Turabian StyleAtapattu, Dinithi, Victoria M. Shoesmith, Fiona M. Wood, and Lisa J. Martin. 2024. "Parental Stress and Child Quality of Life after Pediatric Burn" European Burn Journal 5, no. 2: 77-89. https://doi.org/10.3390/ebj5020007

APA StyleAtapattu, D., Shoesmith, V. M., Wood, F. M., & Martin, L. J. (2024). Parental Stress and Child Quality of Life after Pediatric Burn. European Burn Journal, 5(2), 77-89. https://doi.org/10.3390/ebj5020007