Developing a Burn-Specific Family-Centered Care (BS-FCC) Framework: A Multi-Method Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

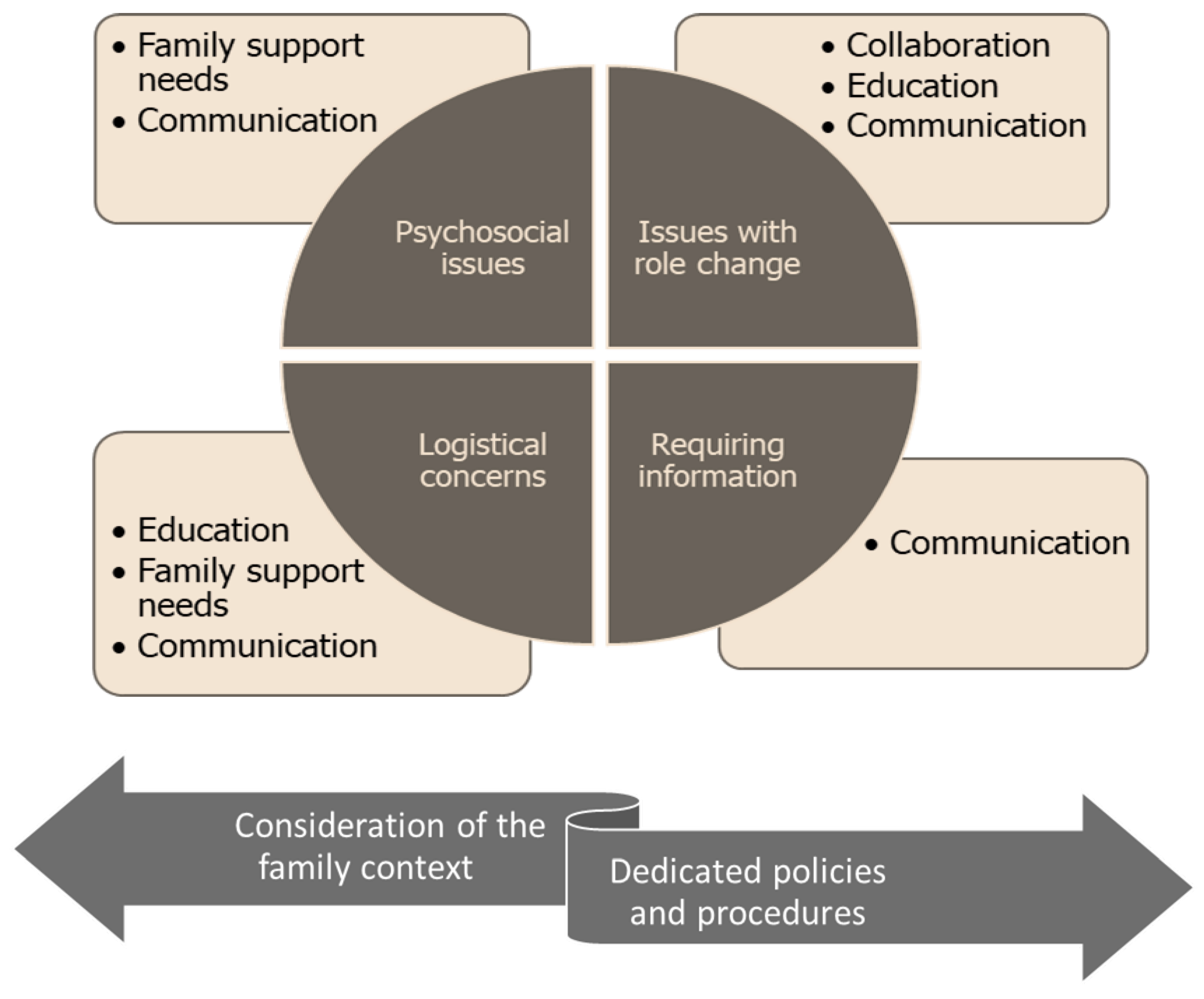

2.2. Components of FCC

- Collaboration: A partnership between healthcare staff, families, and the patient is central to FCC. Collaboration is required across the illness and care trajectory to enhance patients’ and families’ abilities to maintain control over the patient’s care plan and delivery, particularly as care becomes increasingly complex [18,19]. Within the context of collaboration, healthcare professionals are encouraged to relinquish their role as a single authority. Instead, this role is shared with the family. It has been suggested that FCC models should have defined roles for each family member, the patient, and all healthcare staff involved in the care [16].

- Communication: FCC models help to facilitate communication and the exchange of information across all stakeholders involved in patient care, including the family. The exchange of information was encouraged to be open, timely, complete, and objective [20]. FCC models encourage healthcare professionals to utilize a variety of strategies to communicate with and support caregivers and patients as well as disease-specific information to help patients and family members make appropriately informed disease-related decisions [21].

- Education: Education about care provision and the disease was deemed necessary to facilitate FCC. Education centers should focus on mutual learning, whereby patients, family members, and healthcare professionals all learn and support each other [22].

- Family support needs: FCC acknowledges that family members may experience an adverse impact on their own well-being as part of the ongoing demands of caregiving and recognizes that families are often stressed and can have difficulties coping. Thus, FCC models emphasize support for the family’s well-being by employing strategies such as providing emotional support and education/training on delivering hands-on care [23].

- Consideration of the family context: The conceptualization of family varies across FCC models. Families are considered to have ‘the ultimate responsibility’ and should have a constant presence throughout the care and illness trajectory. FCC should identify family strengths and cultural values to deliver culturally sensitive care [24].

- Dedicated policies and procedures: To support implementation, FCC models should have dedicated policies and procedures that are also transparent. Also, the macro- and micro-levels of society need to be considered when trying to implement family-centered practices [25].

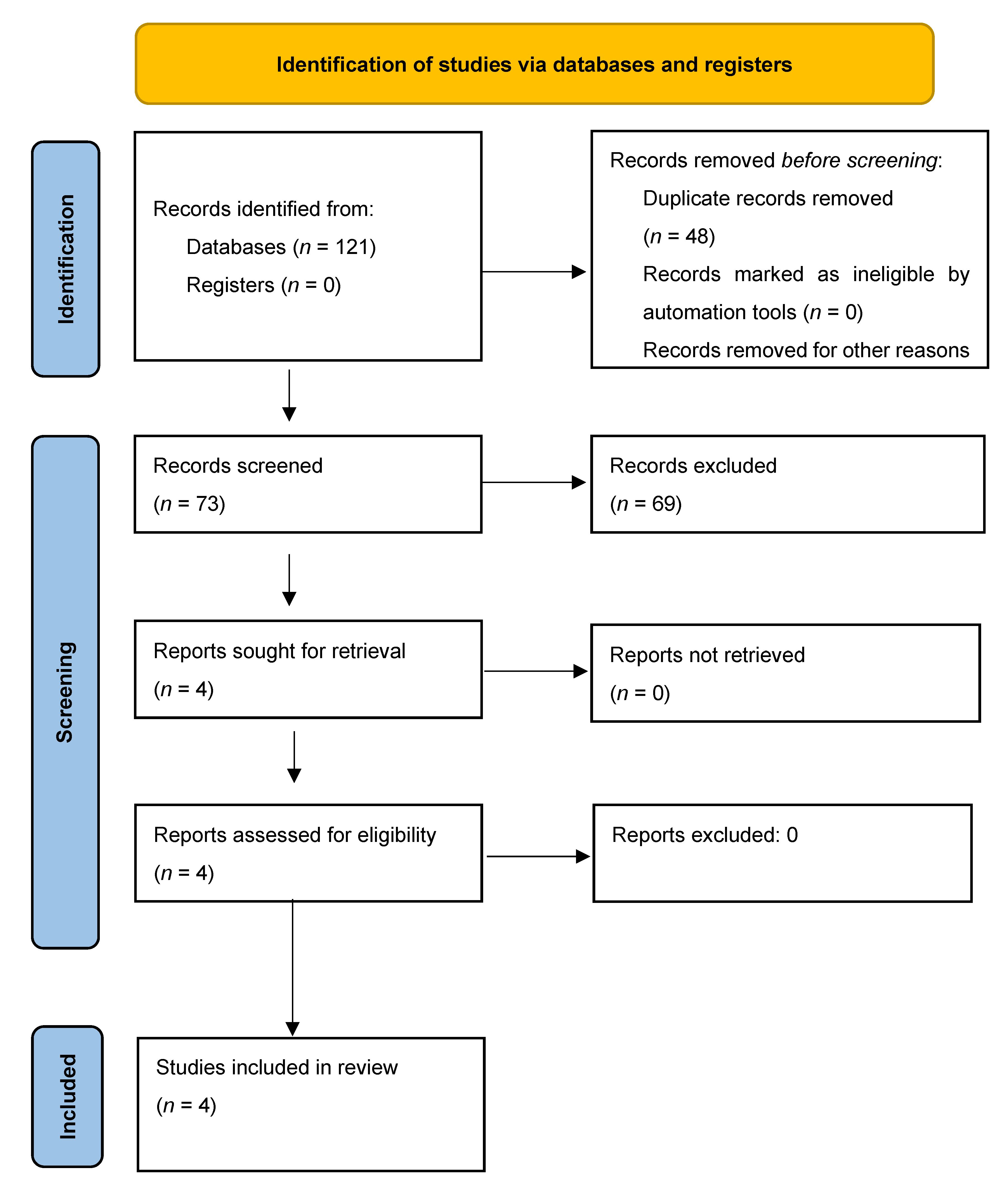

2.3. Umbrella Review Phase

2.4. Literature Search Strategy and Data Collection

2.5. Selecting the Studies

2.6. Methodological Quality

2.7. Data Extraction and Synthesis

2.8. Qualitative Phase

2.9. Integrating Both Datasets

3. Results

3.1. Study Characteristics

3.2. Meta-Themes

3.3. Meta-Theme 1: Psychosocial Issues

“…I just could not think straight at that point. I mean how could this happen on that day. I was wondering why it occurred on that very day because he was always doing okay on his own needing no assistance from anyone”.[35]

“…I could not bear his crying during the wound dressing. It made me also cry. Even with my tears, I stayed with him…I could not just allow him to go through all that pain alone. I had to hide the tears, be strong be there for him.”[34]

“…He could not even move his leg not alone his hands. The wounds I saw were also hard to look at. I knew he had high blood pressure even before the incident, and I was really worried it will affect him looking at the wound”.[35]

3.4. Meta-Theme 2: Issues with Role Changes

“…as the only person taking care of three family members at the same time, and I had work as well because I was not on annual leave. So, every morning I would come and see all three of them, buy medications, dressing materials and get them food. After some few days, I just had to request for leave immediately because I just could not combine it all”.[34]

“In fact, it was not an easy time for me, and my family. I felt burdened with the turn of events though. It was really a big work for me because I was just unprepared at that time to handle the events. The incident was just in my mind and I could not stop thinking about it.”[35]

3.5. Meta-Theme 3: Logistical Concerns

“Sometimes I was worried because of the money involved in the hospital care. The medications were expensive, not to mention the dressing materials. We had to purchase the dressing materials about three times a week. It was difficult getting through those times because I had to think about his welfare and be thinking about where else to get money at the same time.”[35]

3.6. Meta-Theme 4: Requiring Information

“…I remember there was a time a nurse said the wound was okay, later another nurse also said the wounds were not looking too good.”[34]

3.7. Formulating the Burn-Specific FCC Framework

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- WHO Factsheet on Burns. Available online: www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/burns (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Woolard, A.; Hill, N.; McQueen, M.; Martin, L.; Milroy, H.; Wood, F.M.; Lin, A. The psychological impact of paediatric burn injuries: A systematic review. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodha, P.; Shah, B.; Karia, S.; De Sousa, A. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) following burn injuries: A comprehensive clinical review. Ann. Burn. Fire Disasters 2020, 33, 276. [Google Scholar]

- Bäckström, J.; Willebrand, M.; Sjöberg, F.; Haglund, K. Being a family member of a burn survivor–Experiences and needs. Burn. Open 2018, 2, 193–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.M.; Jakab, M.; Marinelli, B.; Kraguljac, A.; Stevenson, C.; Moore, A.; Mehta, S. A questionnaire on satisfaction of family members regarding interdisciplinary family meetings in the intensive care unit. Can. J. Anesth./J. Can. D’anesthésie 2019, 66, 740–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelman, R.D.; Tmanova, L.L.; Delgado, D.; Dion, S.; Lachs, M.S. Caregiver burden: A clinical review. JAMA 2014, 311, 1052–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Association, A. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV-TR), Text Revision; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, C.; Fussell, A.; Rumsey, N. Considerations for psychosocial support following burn injury—A family perspective. Burns 2007, 33, 986–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, L.; Pratt, J.; Hunter, J. Family centred care: A review of qualitative studies. J. Clin. Nurs. 2006, 15, 1317–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clay, A.M.; Parsh, B. Patient-and family-centered care: It’s not just for pediatrics anymore. AMA J. Ethics 2016, 18, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Care, C.O.H.; Patient, I.F.; Care, F.-C. Patient-and family-centered care and the pediatrician’s role. Pediatrics 2012, 129, 394–404. [Google Scholar]

- Goldfarb, M.J.; Bibas, L.; Bartlett, V.; Jones, H.; Khan, N. Outcomes of patient-and family-centered care interventions in the ICU: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Care Med. 2017, 45, 1751–1761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, N.; Fox, J. 748 Burn Center Family Needs Study Brings Changes to The Unit Practice. J. Burn. Care Res. 2022, 43 (Suppl. 1), S180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martha, D.; Sousa, V.D.; Mendes, I.A.C. An overview of research designs relevant to nursing: Part 3: Mixed and multiple methods. Rev. Lat.-Am. De Enferm. 2007, 15, 1046–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuo, D.Z.; Houtrow, A.J.; Arango, P.; Kuhlthau, K.A.; Simmons, J.M.; Neff, J.M. Family-centered care: Current applications and future directions in pediatric health care. Matern. Child Health J. 2012, 16, 297–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kokorelias, K.M.; Gignac, M.A.M.; Naglie, G.; Cameron, J.I. Towards a universal model of family centered care: A scoping review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2019, 19, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, D.O.; Horner, S.D. Family-centered collaborative negotiation: A model for facilitating behavior change in primary care. J. Am. Acad. Nurse Pract. 2008, 20, 194–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, K.; Mace, S.E.; Dietrich, A.M.; Knazik, S.; Schamban, N.E. Patient and family–centred care for pediatric patients in the emergency department. Can. J. Emerg. Med. 2008, 10, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, J.N.; Barfield, R.; Hinds, P.S.; Kane, J.R. A process to facilitate decision making in pediatric stem cell transplantation: The individualized care planning and coordination model. Biol. Blood Marrow Transplant. 2007, 13, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attharos, T.; Phuphaibul, R.; Khampalikit, S.; Tilokskulchai, F. Development of a Family-Centered Care Model for the Children with Cancer in a Pediatric Cancer Unit; Mahidol University: Nakhon Pathom, Thailand, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Regan, K.M.; Curtin, C.; Vorderer, L. Paradigm shifts in inpatient psychiatric care of children: Approaching child- and family-centered care. J. Child Adolesc. Psychiatr. Nurs. 2017, 30, 186–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beers, L.S.; Cheng, T.L. When a teen has a tot: A model of care for the adolescent parent and her child: You can mitigate the health and educational risks faced by an adolescent parent and her child by providing a medical home for both. This “teen-tot” model of family-centered care provides a framework for success. Contemp. Pediatr. 2006, 23, 47–52. [Google Scholar]

- Tluczek, A.; Zaleski, C.; Stachiw-Hietpas, D.; Modaff, P.; Adamski, C.R.; Nelson, M.R.; Reiser, C.A.; Ghate, S.; Josephson, K.D. A tailored approach to family-centered genetic counseling for cystic fibrosis newborn screening: The Wisconsin model. J. Genet. Couns. 2011, 20, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kissane, D.; Lichtenthal, W.G.; Zaider, T. Family care before and after bereavement. Omega-J. Death Dying 2008, 56, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perrin, J.M.; Romm, D.; Bloom, S.R.; Homer, C.J.; Kuhlthau, K.A.; Cooley, C.; Duncan, P.; Roberts, R.; Sloyer, P.; Wells, N.; et al. A family-centered, community-based system of services for children and youth with special health care needs. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2007, 161, 933–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aromataris, E.; Fernandez, R.; Godfrey, C.M.; Holly, C.; Khalil, H.; Tungpunkom, P. Summarizing systematic reviews: Methodological development, conduct and reporting of an umbrella review approach. JBI Evid. Implement. 2015, 13, 132–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pollock, M.; Fernandes, R.M.; Pieper, D.; Tricco, A.C.; Gates, M.; Gates, A.; Hartling, L. Preferred Reporting Items for Overviews of Reviews (PRIOR): A protocol for development of a reporting guideline for overviews of reviews of healthcare interventions. Syst. Rev. 2019, 8, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Moher, D. Updating guidance for reporting systematic reviews: Development of the PRISMA 2020 statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2021, 134, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shea, B.J.; Reeves, B.C.; Wells, G.; Thuku, M.; Hamel, C.; Moran, J.; Moher, D.; Tugwell, P.; Welch, V.; Kristjansson, E.; et al. AMSTAR 2: A critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ 2017, 358, j4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayuo, J.; Wong, F.K.Y. Issues and concerns of family members of burn patients: A scoping review. Burns 2021, 47, 503–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lernevall, L.S.; Moi, A.L.; Cleary, M.; Kornhaber, R.; Dreyer, P. Support needs of parents of hospitalised children with a burn injury: An integrative review. Burns 2020, 46, 771–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundara, D.C. A review of issues and concerns of family members of adult burn survivors. J. Burn. Care Res. 2011, 32, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wong, F.K.Y.; Bayuo, J.; Chung, L.Y.F.; Zhang, L.; Wang, T. Challenges of nurses and family members of burn patients: Integrative review. Nurs. Open 2023, 10, 3547–3560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bayuo, J.; Bristowe, K.; Harding, R.; Agbeko, A.E.; Baffour, P.K.; Agyei, F.B.; Wong, F.K.Y.; Allotey, G.; Agbenorku, P.; Hoyte-Williams, P.E. “Managing uncertainty”: Experiences of family members of burn patients from injury occurrence to the end-of-life period. Burns 2021, 47, 1647–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayuo, J.; Aniteye, P.; Richter, S.; Agbenorku, P. Exploring the background, context, and stressors of caregiving to elderly burned patients: A qualitative inquiry. J. Burn. Care Res. 2022, 43, 196–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bayuo, J.; Bristowe, K.; Harding, R.; Agbeko, A.E.; Wong FK, Y.; Agyei, F.B.; Agambire, R. “Hanging in a balance”: A qualitative study exploring clinicians’ experiences of providing care at the end of life in the burn unit. Palliat. Med. 2021, 35, 417–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Q1 (PICO Components) | Q2 (Methods Established Prior to the Review) | Q3 (Study Design Selection) | Q4 (Comprehensive Literature Search Strategy) | Q5 (Study Selection in Duplicate) | Q6 (Data Extraction in Duplicate) | Q7 (List of Excluded Studies and Justifications) | Q8 (Description of Included Studies) | Q9 (Risk of Bias Assessment) | Q10 (Reporting Sources of Funding) | Q11 (Meta-Analysis Performed) | Q12 (Potential Impact of Risk of Bias Assessment) | Q13 (Accounting for Risk of Bias in Including Studies) | Q14 (Explanation for Heterogeneity) | Q15 (Adequate Investigation of Publication Bias) | Q16 (Reporting Conflict of Interests) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bayuo and Wong [30] | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | N/A | No | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes |

| Lernevall et al. [31] | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | N/A | No | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes |

| Sundara [32] | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | N/A | No | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes |

| Wang et al. [33] | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | N/A | No | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Yes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bayuo, J.; Agbeko, A.E. Developing a Burn-Specific Family-Centered Care (BS-FCC) Framework: A Multi-Method Study. Eur. Burn J. 2023, 4, 280-291. https://doi.org/10.3390/ebj4030025

Bayuo J, Agbeko AE. Developing a Burn-Specific Family-Centered Care (BS-FCC) Framework: A Multi-Method Study. European Burn Journal. 2023; 4(3):280-291. https://doi.org/10.3390/ebj4030025

Chicago/Turabian StyleBayuo, Jonathan, and Anita Eseenam Agbeko. 2023. "Developing a Burn-Specific Family-Centered Care (BS-FCC) Framework: A Multi-Method Study" European Burn Journal 4, no. 3: 280-291. https://doi.org/10.3390/ebj4030025

APA StyleBayuo, J., & Agbeko, A. E. (2023). Developing a Burn-Specific Family-Centered Care (BS-FCC) Framework: A Multi-Method Study. European Burn Journal, 4(3), 280-291. https://doi.org/10.3390/ebj4030025