Green Strategies for the Synthesis of Heterocyclic Derivatives with Potential Against Neglected Tropical Diseases

Abstract

1. Introduction

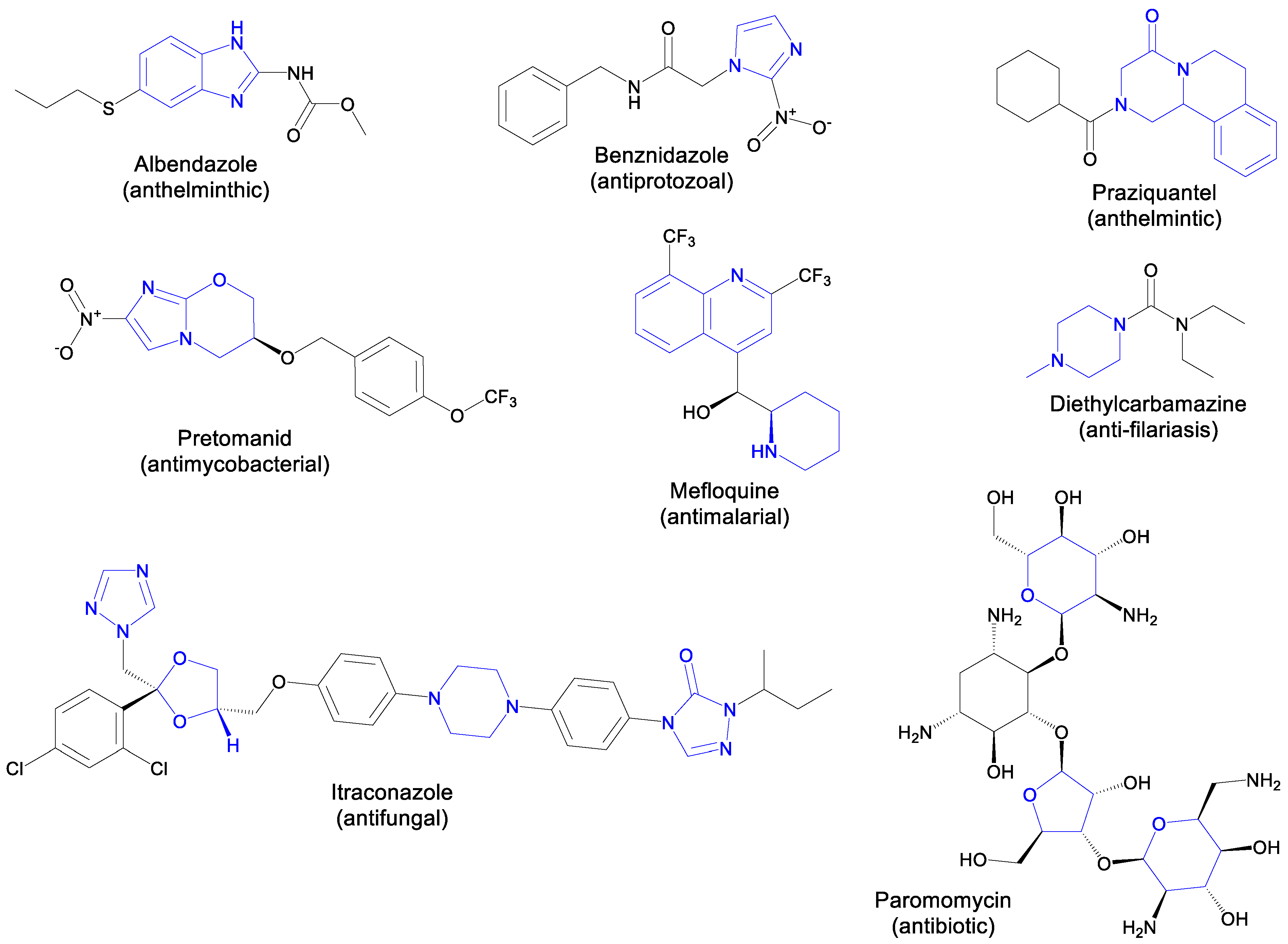

2. Neglected Tropical Diseases and the Climate Emergency

3. Heterocycles in the Development of New Treatments for NTDs

4. Green Chemistry Principles

5. Heterocyclic Scaffolds for NTD Drug Discovery: Green Synthetic Approaches

5.1. Microwave-Assisted Sustainable Synthesis: Solvent-Free and Green-Solvent Pathways

5.2. Ultrasound as a Green Tool for the Synthesis of Heterocyclic Scaffolds

5.3. Mechanochemical Advances Enabling One-Pot Multistep Organic Synthesis

5.4. Ionic Liquids as Catalysts in Green Chemistry Approaches

5.5. Deep Eutectic Solvents in Sustainable Heterocycle Synthesis

5.6. Comparative Summary of Green Approaches in Heterocyclic Synthesis

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization. Neglected Tropical Diseases. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/neglected-tropical-diseases#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Tidman, R.; Abela-Ridder, B.; de Castañeda, R.R. The Impact of Climate Change on Neglected Tropical Diseases: A Systematic Review. Trans. R. Soc. Trop. Med. Hyg. 2021, 115, 147–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora, C.; McKenzie, T.; Gaw, I.M.; Dean, J.M.; von Hammerstein, H.; Knudson, T.A.; Setter, R.O.; Smith, C.Z.; Webster, K.M.; Patz, J.A.; et al. Over Half of Known Human Pathogenic Diseases Can Be Aggravated by Climate Change. Nat. Clim. Change 2022, 12, 869–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- IPCC. Global Warming 1.5 °C; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/sr15/ (accessed on 12 October 2025).

- Liu, Q.; Tan, Z.-M.; Sun, J.; Hou, Y.; Fu, C.; Wu, Z. Changing Rapid Weather Variability Increases Influenza Epidemic Risk in a Warming Climate. Environ. Res. Lett. 2020, 15, 044004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, M.; O’Boyle, N.M. Analysis of the Structural Diversity of Heterocycles amongst European Medicines Agency Approved Pharmaceuticals (2014–2023). RSC Med. Chem. 2025, 16, 4540–4570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shearer, J.; Castro, J.L.; Lawson, A.D.G.; MacCoss, M.; Taylor, R.D. Rings in Clinical Trials and Drugs: Present and Future. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 65, 8699–8712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barcellos, C.; Matos, V.; Lana, R.M.; Lowe, R. Climate Change, Thermal Anomalies, and the Recent Progression of Dengue in Brazil. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 5948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peerzada, M.N.; Hamel, E.; Bai, R.; Supuran, C.T. Deciphering the Key Heterocyclic Scaffolds in Targeting Microtubules, Kinases and Carbonic Anhydrases for Cancer Drug Development. Pharmacol. Ther. 2021, 225, 107860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desai, N.; Monapara, J.; Jethawa, A.; Khedkar, V.; Shingate, B. Oxadiazole: A Highly Versatile Scaffold in Drug Discovery. Arch. Pharm. 2022, 355, 2200123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De, S.; Aamna, B.; Sahu, R.; Parida, S.; Behera, S.K.; Dan, A.K. Seeking Heterocyclic Scaffolds as Antivirals against Dengue Virus. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2022, 240, 114576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maus, H.; Barthels, F.; Hammerschmidt, S.J.; Kopp, K.; Millies, B.; Gellert, A.; Ruggieri, A.; Schirmeister, T. SAR of Novel Benzothiazoles Targeting an Allosteric Pocket of DENV and ZIKV NS2B/NS3 Proteases. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2021, 47, 116392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrd, C.M.; Grosenbach, D.W.; Berhanu, A.; Dai, D.; Jones, K.F.; Cardwell, K.B.; Schneider, C.A.; Yang, G.; Tyavanagimatt, S.; Harver, C.; et al. Novel Benzoxazole Inhibitor of Dengue Virus Replication That Targets the NS3 Helicase. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 1902–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nobori, H.; Toba, S.; Yoshida, R.; Hall, W.W.; Sawa, H.; Sato, A. Identification of Compound-B, a Novel Anti-Dengue Virus Agent Targeting the Non-Structural Protein 4A. Antiviral Res. 2018, 155, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, S.; Zhao, J.; Wu, X.; Yao, Y.; Wu, F.; Lin, Y.-L.; Li, X.; Kneubehl, A.R.; Vogt, M.B.; Rico-Hesse, R.; et al. Synthesis, Structure-Activity Relationship and Antiviral Activity of Indole-Containing Inhibitors of Flavivirus NS2B-NS3 Protease. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 225, 113767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Francesconi, V.; Rizzo, M.; Schenone, S.; Carbone, A.; Tonelli, M. State-of-The-Art Review on the Antiparasitic Activity of Benzimidazolebased Derivatives: Facing Malaria, Leishmaniasis, and Trypanosomiasis. Curr. Med. Chem. 2023, 31, 1955–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vázquez-Jiménez, L.K.; Juárez-Saldivar, A.; Gómez-Escobedo, R.; Delgado-Maldonado, T.; Méndez-Álvarez, D.; Palos, I.; Bandyopadhyay, D.; Gaona-Lopez, C.; Ortiz-Pérez, E.; Nogueda-Torres, B.; et al. Ligand-Based Virtual Screening and Molecular Docking of Benzimidazoles as Potential Inhibitors of Triosephosphate Isomerase Identified New Trypanocidal Agents. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 10047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Téllez-Valencia, A.; Ávila-Ríos, S.; Pérez-Montfort, R.; Rodríguez-Romero, A.; Tuena de Gómez-Puyou, M.; López-Calahorra, F.; Gómez-Puyou, A. Highly Specific Inactivation of Triosephosphate Isomerase from Trypanosoma cruzi. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002, 295, 958–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores Sandoval, C.A.; Cuevas Hernández, R.I.; Correa Basurto, J.; Beltrán Conde, H.I.; Padilla Martínez, I.I.; Farfán García, J.N.; Nogueda Torres, B.; Trujillo Ferrara, J.G. Synthesis and Theoretic Calculations of Benzoxazoles and Docking Studies of Their Interactions with Triosephosphate Isomerase. Med. Chem. Res. 2012, 22, 2768–2777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.Y.; Calvet, C.M.; Gunatilleke, S.S.; Ruiz, C.; Cameron, M.D.; McKerrow, J.H.; Podust, L.M.; Roush, W.R. Rational Development of 4-Aminopyridyl-Based Inhibitors Targeting Trypanosoma Cruzi CYP51 as Anti-Chagas Agents. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 7651–7668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandyopadhyay, D.; Samano, S.; Villalobos-Rocha, J.C.; Enid Sanchez-Torres, L.; Nogueda-Torres, B.; Rivera, G.; Banik, B.K. A Practical Green Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Benzimidazoles against Two Neglected Tropical Diseases: Chagas and Leishmaniasis. Curr. Med. Chem. 2018, 24, 4714–4725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nieto-Meneses, R.; Castillo, R.; Hernández-Campos, A.; Maldonado-Rangel, A.; Matius-Ruiz, J.B.; Josué Trejo-Soto, P.; Nogueda-Torres, B.; Dea-Ayuela Ma, A.; Bolás-Fernández, F.; Méndez-Cuesta, C.; et al. In Vitro Activity of New N-Benzyl-1H-Benzimidazol-2-Amine Derivatives Against Cutaneous, Mucocutaneous and Visceral Leishmania Species. Exp. Parasitol. 2018, 184, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Luca, L.; Ferro, S.; Buemi, M.R.; Maria Monforte, A.; Gitto, R.; Schirmeister, T.; Maes, L.; Rescifina, A.; Micale, N. Discovery of Benzimidazole-Based Leishmania mexicana Cysteine Protease CPB2.8ΔCTE Inhibitors as Potential Therapeutics for Leishmaniasis. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2018, 92, 1585–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, P.R.; de Oliveira, J.F.; da Silva, A.L.; Queiroz, C.M.; Feitosa, A.P.S.; Duarte, D.M.F.A.; da Silva, A.C.; de Castro, M.C.A.B.; Pereira, V.R.A.; da Silva, R.M.F.; et al. Novel Indol-3-Yl-Thiosemicarbazone Derivatives: Obtaining, Evaluation of in Vitro Leishmanicidal Activity and Ultrastructural Studies. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2020, 315, 108899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahran, M.; William, S.; Ramzy, F.; Sembel, A. Synthesis and In Vitro Evaluation of New Benzothiazole Derivatives as Schistosomicidal Agents. Molecules 2007, 12, 622–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayoka, G.; Keiser, J.; Häberli, C.; Chibale, K. Structure–Activity Relationship and In Vitro Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) Studies of N-Aryl 3-Trifluoromethyl Pyrido[1,2-A]Benzimidazoles That Are Efficacious in a Mouse Model of Schistosomiasis. ACS Infect. Dis. 2018, 5, 418–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Bialy, S.A.; Taman, A.; El-Beshbishi, S.N.; Mansour, B.; El-Malky, M.; Bayoumi, W.A.; Essa, H.M. Effect of a Novel Benzimidazole Derivative in Experimental Schistosoma Mansoni Infection. Parasitol. Res. 2013, 112, 4221–4229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moreira, B.P.; Gava, S.G.; Haeberlein, S.; Gueye, S.; Santos, E.S.S.; Weber, M.H.W.; Abramyan, T.M.; Grevelding, C.G.; Mourão, M.M.; Falcone, F.H. Identification of Potent Schistosomicidal Compounds Predicted as Type II-Kinase Inhibitors against Schistosoma Mansoni C-Jun N-Terminal Kinase SMJNK. Front. Parasitol. 2024, 3, 1394407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vernekar, S.K.V.; Qiu, L.; Zhang, J.; Kankanala, J.; Li, H.; Geraghty, R.J.; Wang, Z. 5′-Silylated 3′-1,2,3-Triazolyl Thymidine Analogues as Inhibitors of West Nile Virus and Dengue Virus. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 4016–4028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar Vishvakarma, V.; Shukla, N.; Kumari, K.; Patel, R.; Singh, P. A Model to Study the Inhibition of NsP2B-NsP3 Protease of Dengue Virus with Imidazole, Oxazole, Triazole Thiadiazole, and Thiazolidine Based Scaffolds. Heliyon 2019, 5, e02124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saudi, M.; Zmurko, J.; Kaptein, S.; Rozenski, J.; Gadakh, B.; Chaltin, P.; Marchand, A.; Neyts, J.; Aerschot, A.V. Synthetic Strategy and Antiviral Evaluation of Diamide Containing Heterocycles Targeting Dengue and Yellow Fever Virus. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 121, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benmansour, F.; Eydoux, C.; Quérat, G.; de Lamballerie, X.; Canard, B.; Alvarez, K.; Guillemot, J.-C.; Barral, K. Novel 2-Phenyl-5-[(E)-2-(Thiophen-2-Yl)Ethenyl]-1,3,4-Oxadiazole and 3-Phenyl-5-[(E)-2-(Thiophen-2-Yl)Ethenyl]-1,2,4-Oxadiazole Derivatives as Dengue Virus Inhibitors Targeting NS5 Polymerase. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 109, 146–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdani, S.S.; Khan, B.A.; Hameed, S.; Batool, F.; Saleem, H.N.; Mughal, E.U.; Saeed, M. Synthesis and Evaluation of Novel S-Benzyl- and S-Alkylphthalimide-Oxadiazole-Benzenesulfonamide Hybrids as Inhibitors of Dengue Virus Protease. Bioorg. Chem. 2020, 96, 103567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, M.; Curty Lechuga, G.; Lara, L.S.; Souto, B.A.; Viganò, M.; Cabral Bourguignon, S.; Calvet, C.M.; Oliveira, F.J.; Alves, C.; Souza-Silva, F.; et al. Synthesis, Structure-Activity Relationship and Trypanocidal Activity of Pyrazole-Imidazoline and New Pyrazole-Tetrahydropyrimidine Hybrids as Promising Chemotherapeutic Agents for Chagas Disease. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 182, 111610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papadopoulou, M.V.; Bloomer, W.D.; Rosenzweig, H.S.; Chatelain, E.; Kaiser, M.; Wilkinson, S.R.; McKenzie, C.; Ioset, J.-R. Novel 3-Nitro-1H-1,2,4-Triazole-Based Amides and Sulfonamides as Potential Antitrypanosomal Agents. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 5554–5565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campo, V.L.; Sesti-Costa, R.; Carneiro, Z.A.; Silva, J.S.; Schenkman, S.; Carvalho, I. Design, Synthesis and the Effect of 1,2,3-Triazole Sialylmimetic Neoglycoconjugates on Trypanosoma Cruzi and Its Cell Surface Trans-Sialidase. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2012, 20, 145–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fernandes, F.S.; Santos, H.; Lima, S.R.; Conti, C.; Rodrigues, M.T.; Zeoly, L.A.; Ferreira, L.L.G.; Krogh, R.; Andricopulo, A.D.; Coelho, F. Discovery of Highly Potent and Selective Antiparasitic New Oxadiazole and Hydroxy-Oxindole Small Molecule Hybrids. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2020, 201, 112418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ricardo Teixeira, R.; Rodrigues, A.; Socorro, A.; Paula, M.; Rossi Bergmann, B.; Salgado Ferreira, R.; Vaz, B.G.; Vasconcelos, G.A.; Luís, W. Synthesis and Leishmanicidal Activity of Eugenol Derivatives Bearing 1,2,3-Triazole Functionalities. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 146, 274–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil, S.R.; Asrondkar, A.; Patil, V.; Sangshetti, J.N.; Kalam Khan, F.A.; Damale, M.G.; Patil, R.H.; Bobade, A.S.; Shinde, D.B. Antileishmanial Potential of Fused 5-(Pyrazin-2-Yl)-4H-1,2,4-Triazole-3-Thiols: Synthesis, Biological Evaluations and Computational Studies. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2017, 27, 3845–3850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleghorn, L.A.T.; Woodland, A.; Collie, I.T.; Torrie, L.S.; Norcross, N.; Luksch, T.; Mpamhanga, C.; Walker, R.G.; Mottram, J.C.; Brenk, R.; et al. Identification of Inhibitors of the Leishmania Cdc2-Related Protein Kinase CRK3. ChemMedChem 2011, 6, 2214–2224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.A. Pyrazole: An Emerging Privileged Scaffold in Drug Discovery. Future Med. Chem. 2023, 15, 2011–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Tian, S.; Yang, X.; Liu, Z. Synthesis Methods of 1,2,3-/1,2,4-Triazoles: A Review. Front. Chem. 2022, 10, 891484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, S.; Sahiba, N.; Teli, S.; Teli, P.; Kumar Agarwal, L.; Agarwal, S. Advances in the Synthetic Strategies of Benzoxazoles Using 2-Aminophenol as a Precursor: An Up-to-Date Review. RSC Adv. 2023, 12, 24093–24111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowman, W.R.; Bridge, C.F.; Brookes, P. Synthesis of Heterocycles by Radical Cyclisation. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2000, 1, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.-H.; Liu, P.-L.; Wong, F.F. Vilsmeier Reagent-Mediated Synthesis of 6-[(Formyloxy)Methyl]-Pyrazolopyrimidines via a One-Pot Multiple Tandem Reaction. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 47098–47107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chahal, M.; Dhillon, S.; Rani, P.; Kumari, G.; Kumar Aneja, D.; Kinger, M. Unravelling the Synthetic and Therapeutic Aspects of Five, Six and Fused Heterocycles Using Vilsmeier–Haack Reagent. RSC Adv. 2023, 12, 26604–26629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastas, P.T.; Kirchhoff, M.M. Origins, Current Status, and Future Challenges of Green Chemistry. Acc. Chem. Res. 2002, 35, 686–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anastas, P.T.; Warner, J.C. Green Chemistry; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2000; Volume 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tucker, J.L. Green Chemistry, a Pharmaceutical Perspective. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2006, 10, 315–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erythropel, H.C.; Zimmerman, J.B.; de Winter, T.M.; Petitjean, L.; Melnikov, F.; Lam, C.H.; Lounsbury, A.W.; Mellor, K.E.; Janković, N.Z.; Tu, Q.; et al. The Green ChemisTREE: 20 Years after Taking Root with the 12 Principles. Green Chem. 2018, 20, 1929–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayanand Katre, S. Microwaves in Organic Synthetic Chemistry—A Greener Approach to Environmental Protection: An Overview. Asian J. Green Chem. 2024, 8, 68–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, S.; Talreja, S. Green Chemistry and Microwave Irradiation Technique: A Review. J. Pharm. Res. Int. 2022, 34, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawande, M.B.; Shelke, S.N.; Zboril, R.; Varma, R.S. Microwave-Assisted Chemistry: Synthetic Applications for Rapid Assembly of Nanomaterials and Organics. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 1338–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatel, G.; Varma, R.S. Ultrasound and Microwave Irradiation: Contributions of Alternative Physicochemical Activation Methods to Green Chemistry. Green Chem. 2019, 21, 6043–6050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmani, H.R.; Mosslemin, M.H.; Sadeghi, B. Microwave-Assisted Green Synthesis of 4,5-Dihydro-1H-Pyrazole-1-Carbothioamides in Water. Mol. Divers. 2018, 22, 743–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Algul, O.; Kaessler, A.; Apcin, Y.; Yilmaz, A.; Jose, J. Comparative Studies on Conventional and Microwave Synthesis of Some Benzimidazole, Benzothiazole and Indole Derivatives and Testing on Inhibition of Hyaluronidase. Molecules 2008, 12, 736–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohamed Al-Zaydi, K. A Simplified Green Chemistry Approaches to Synthesis of 2-Substituted 1,2,3-Triazoles and 4-Amino-5-Cyanopyrazole Derivatives Conventional Heating versus Microwave and Ultrasound as Ecofriendly Energy Sources. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2009, 16, 805–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patil, S.A.; Patil, R.; Miller, D.D. Microwave-Assisted Synthesis of Medicinally Relevant Indoles. Curr. Med. Chem. 2011, 18, 615–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chui, W.-K.; Dolzhenko, A.V.; Dolzhenko, A.V. Microwave-Assisted Synthesis of S-Triazino[2,1-B][1,3]Benzoxazoles, S-Triazino[2,1-B][1,3]Benzothiazoles, and S-Triazino[1,2-A]Benzimidazoles. Synthesis 2006, 2006, 597–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cintas, P.; Luche, J.-L. Green Chemistry. The sonochemical approach. Green Chem. 1999, 1, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatel, G. How Sonochemistry Contributes to Green Chemistry? Ultrason. Sonochem. 2018, 40, 117–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, P.A.T.M.; Oliveira, A.R.; Cardoso, M.V.O.; Santiago, E.F.; Barbosa, M.O.; Siqueira, L.R.P.; Moreira, D.R.M.; Bastos, T.M.; Brayner, F.A.; Soares, M.B.P.; et al. Phthalimido-Thiazoles as Building Blocks and Their Effects on the Growth and Morphology of Trypanosoma cruzi. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 111, 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliança, A.S.S.; Oliveira, A.R.; Feitosa, A.P.S.; Ribeiro, K.R.C.; de Castro, M.C.A.B.; Leite, A.C.; Alves, L.C.; Brayner, F.A. In vitro evaluation of cytotoxicity and leishmanicidal activity of phthalimido-thiazole derivatives. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2017, 105, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rock, J.; Garcia, D.; Espino, O.; Shetu, S.A.; Chan-Bacab, M.J.; Moo-Puc, R.; Patel, N.B.; Rivera, G.; Bandyopadhyay, D. Benzopyrazine-Based Small Molecule Inhibitors as Trypanocidal and Leishmanicidal Agents: Green Synthesis, In Vitro, and In Silico Evaluations. Front. Chem. 2021, 9, 725892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

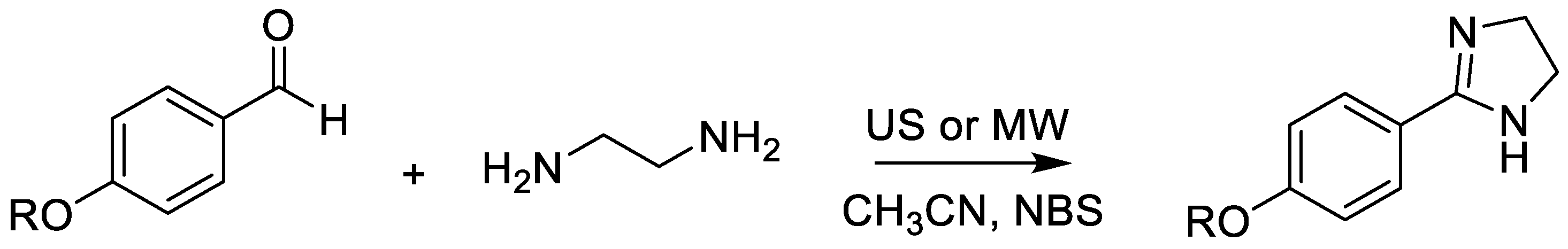

- Torres-Jaramillo, J.; Blöcher, R.; Chacón-Vargas, K.F.; Hernández-Calderón, J.; Sánchez-Torres, L.E.; Nogueda-Torres, B.; Reyes-Arellano, A. Synthesis of Antiprotozoal 2-(4-Alkyloxyphenyl)-Imidazolines and Imidazoles and Their Evaluation on Leishmania mexicana and Trypanosoma cruzi. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 3673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biedermann, N.; Schnürch, M. Advances in Mechanochemical Methods for One-Pot Multistep Organic Synthesis. Chem. Eur. J. 2025, 31, e202500798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.; Liu, C.; Yu, L.; Hou, H.; Sun, W.; Fang, K. Synthesis of Benzimidazole by Mortar–Pestle Grinding Method. Green Chem. Lett. Rev. 2021, 14, 612–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EL-Sayed, T.; Aboelnaga, A.; Hagar, M. Ball Milling Assisted Solvent and Catalyst Free Synthesis of Benzimidazoles and Their Derivatives. Molecules 2016, 21, 1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, R.; Kumar, K. Synthetic and Medicinal Perspective of Quinolines as Antiviral Agents. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 215, 113220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

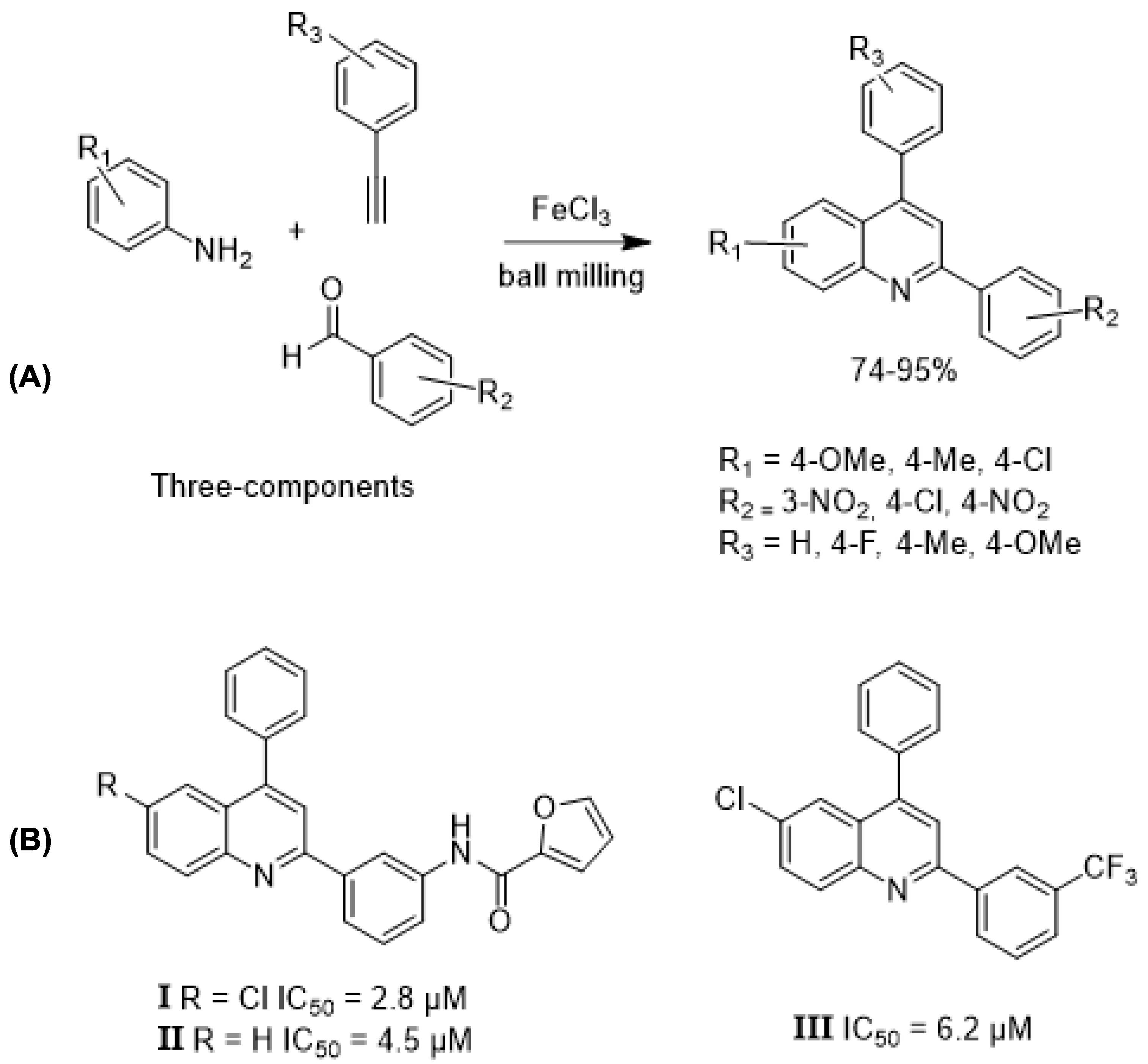

- Tan, Y.; Wang, F.; Asirib, A.M.; Marwanib, H.M.; Zhang, Z. FeCl3-Mediated One-Pot Cyclization–Aromatization of Anilines, Benzaldehydes, and Phenylacetylenes Under Ball Milling: A New Alternative for the Synthesis of 2,4-Diphenylquinolines. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 2017, 65, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oluwafemi, K.A.; Phunguphungu, S.; Gqunu, S.; Isaacs, M.; Hoppe, H.C.; Klein, R.; Kaye, P.T. Synthesis and Trypanocidal Activity of Substituted 2,4-DiaryIquinoline Derivatives. Arkivoc 2021, viii, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

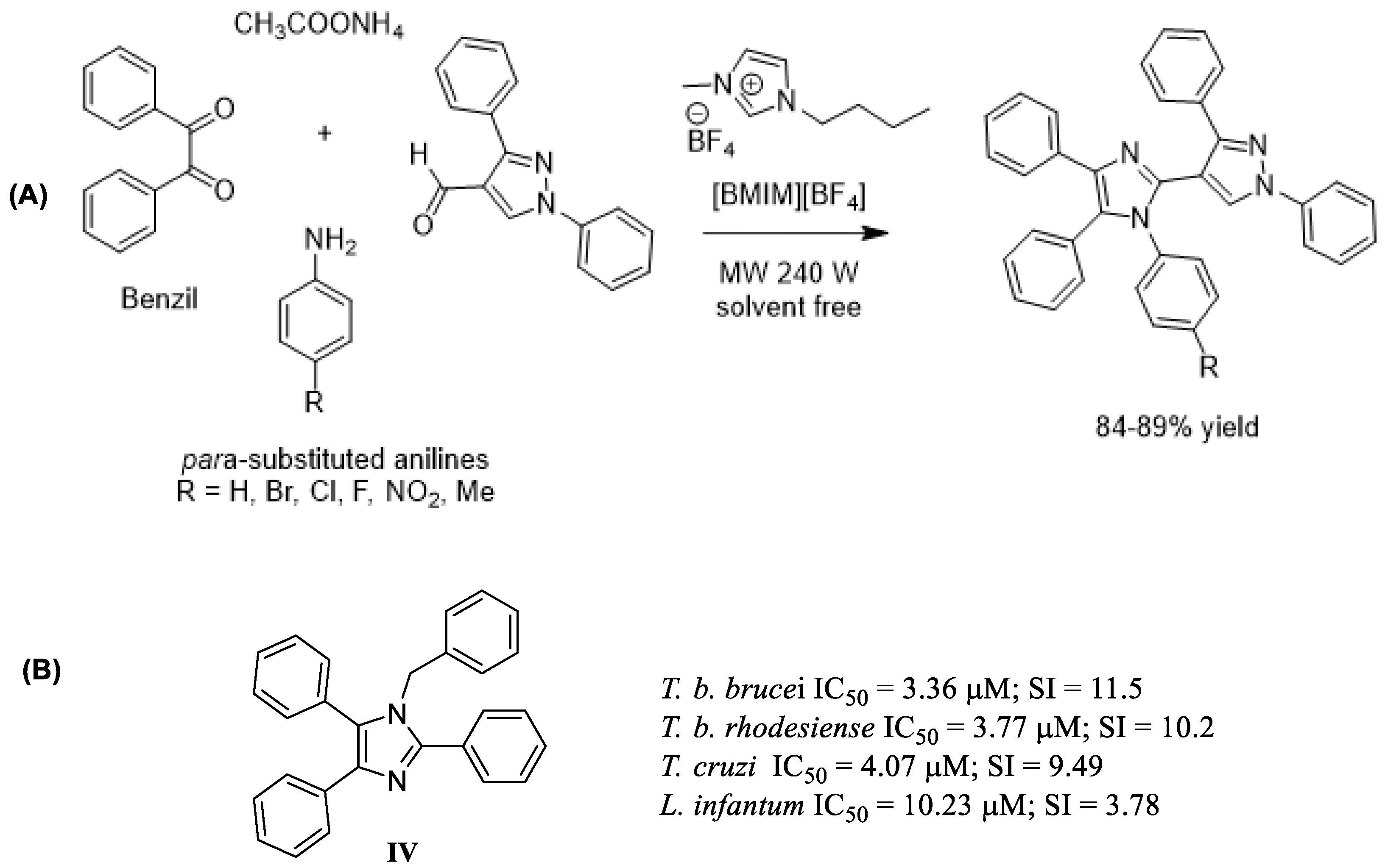

- Dwivedi, J.; Jaiswal, S.; Kapoor, D.U.; Sharma, S. Catalytic Application of Ionic Liquids for the Green Synthesis of Aromatic Five-Membered Nitrogen Heterocycles. Catalysts 2025, 15, 931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, M.A.A.; Kadry, A.M.; Bekhit, S.A.; Abourehab, M.A.S.; Amagase, K.; Ibrahim, T.M.; El-Saghier, A.M.M.; Bekhit, A.A. Spiro Heterocycles Bearing Piperidine Moiety as Potential Scaffold for Antileishmanial Activity: Synthesis, Biological Evaluation, and In Silico Studies. J. Enzym. Inhib. Med. Chem. 2022, 38, 330–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maity, P.; Mitra, A.K. Ionic Liquid-Assisted Approaches in the Synthesis of Nitrogen-Containing Heterocycles: A Focus on 3- to 6-Membered Rings. J. Ion. Liq. 2025, 5, 100146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

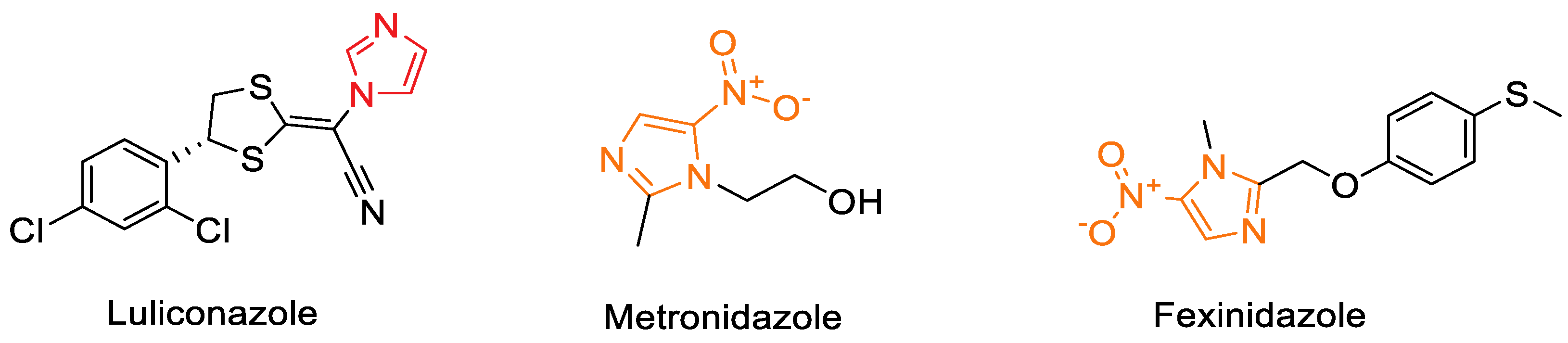

- Shokri, A.; Abastabar, M.; Keighobadi, M.; Emami, S.; Fakhar, M.; Teshnizi, S.H.; Makimura, K.; Rezaei-Matehkolaei, A.; Mirzaei, H. Promising Antileishmanial Activity of Novel Imidazole Antifungal Drug Luliconazole Against Leishmania Major: In Vitro and In Silico Studies. J. Glob. Antimicrob. Resist. 2018, 14, 260–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shirole, G.D.; Kadnor, V.A.; Tambe, A.S.; Shelke, S.N. Brønsted-Acidic Ionic Liquid: Green Protocol for Synthesis of Novel Tetrasubstituted Imidazole Derivatives under Microwave Irradiation via Multicomponent Strategy. Res. Chem. Interm. 2016, 43, 1089–1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, R.; Torres-Gutiérrez, E.; Hernández-Núñez, E.; Gutiérrez-Castro, C.; Nogueda-Torres, B.; Hernández-Luis, F.; Giles-Rivas, C.G. In vitro evaluation of arylsubstituted imidazoles derivatives as antiprotozoal agents and docking studies on sterol 14α-demethylase (CYP51) from Trypanosoma cruzi, Leishmania infantum, and Trypanosoma brucei. Parasitol. Res. 2019, 118, 1533–1548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Domingues, L.; Duarte, A.R.C.; Jesus, A.R. How Can Deep Eutectic Systems Promote Greener Processes in Medicinal Chemistry and Drug Discovery? Pharmaceuticals 2024, 17, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Truong, V.A.; Tran, M.H.; Nguyen, T.H.; Nguyen, H.T. Deep Eutectic Solvent as a Green Catalyst for the One-Pot Multicomponent Synthesis of 2-Substituted Benzothiazole Derivatives. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 39462–39471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrone, S.; Messa, F.; Troisi, L.; Salomone, A. N-, O- and S-Heterocycles Synthesis in Deep Eutectic Solvents. Molecules 2023, 28, 3459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falcini, C.; de Gonzalo, G. Deep Eutectic Solvents as Catalysts in the Synthesis of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients and Precursors. Catalysts 2024, 14, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velásquez-Torres, M.; Trujillo-Ferrara, J.G.; Godínez-Victoria, M.; Jarillo-Luna, R.A.; Tsutsumi, V.; Sánchez-Monroy, V.; Posadas-Mondragón, A.; Cuevas-Hernández, R.I.; Santiago-Cruz, J.A.; Pacheco-Yépez, J. Riluzole, a Derivative of Benzothiazole as a Potential Anti-Amoebic Agent Against Entamoeba Histolytica. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, F.; Di Giorgio, C.; Robin, M.; Azas, N.; Gasquet, M.; Detang, C.; Costa, M.; Timon-David, P.; Galy, J.-P. In Vitro Activities of Position 2 Substitution-Bearing 6-Nitro- and 6-Amino-Benzothiazoles and Their Corresponding Anthranilic Acid Derivatives against Leishmania infantum and Trichomonas vaginalis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002, 46, 2588–2594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Green Chemistry Principle | Example of Application in Heterocyclic Synthesis | Advantages | Potential Relevance for NTD Drug Discovery | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

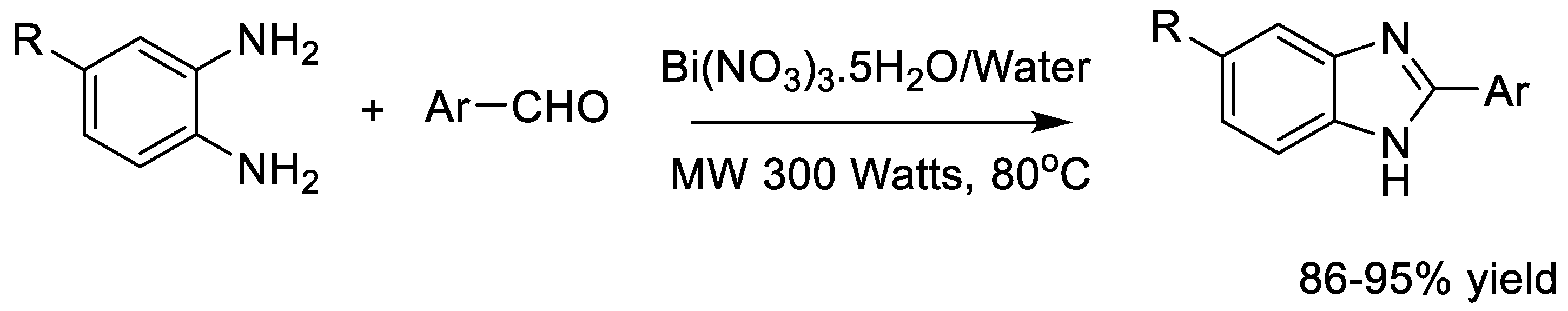

| Energy Efficiency/Solvent-Free or Green Solvents (Microwave-Assisted Organic Synthesis—MAOS) | Synthesis of benzimidazole derivatives using Bi(NO3)3·5H2O in aqueous medium under microwave irradiation. | Fast reactions; high yields (up to 94%); use of water or solvent-free conditions; high atom economy; reduced waste; minimal purification. | Access to benzimidazole scaffolds with activity against Chagas disease and leishmaniasis. | [21,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59] |

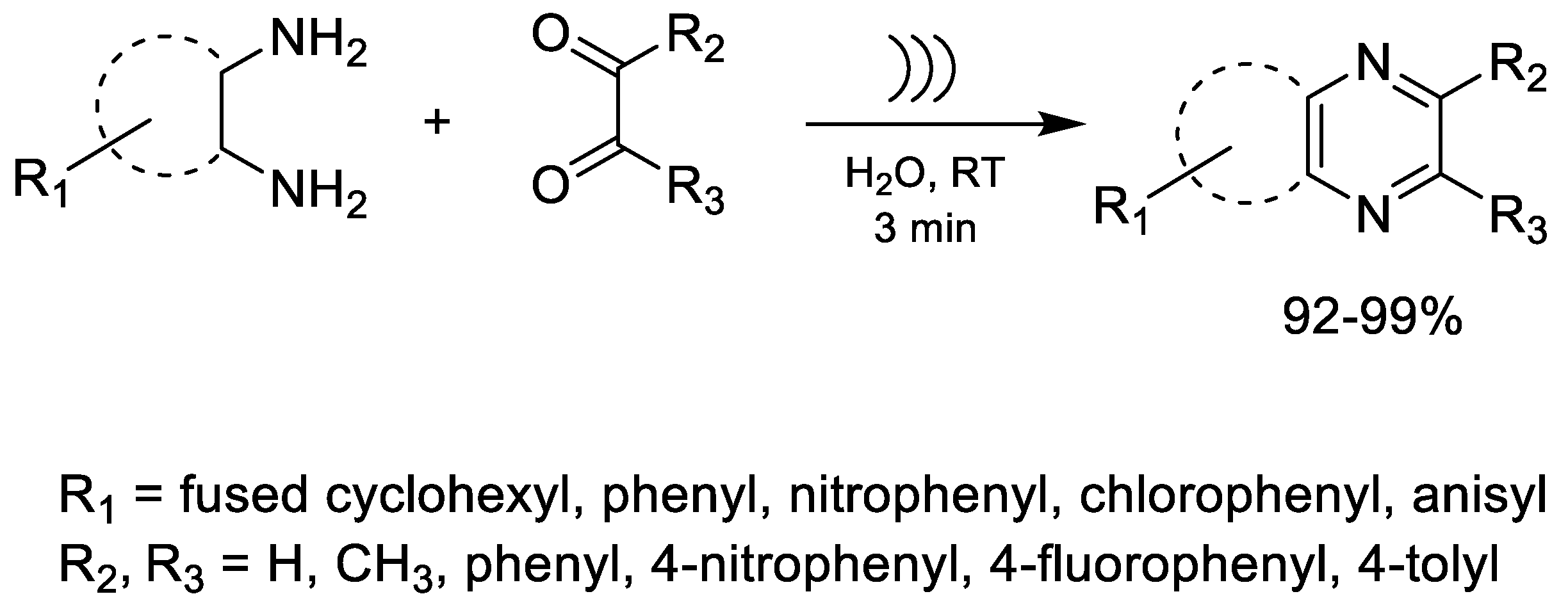

| Alternative Energy Sources/Mild Reaction Conditions (Ultrasound-Assisted Synthesis) | Ultrasound-assisted synthesis of benzopyrazines in water without catalysts or hazardous solvents (~3 min). | High yields (>92%); catalyst-free; eco-friendly solvent; mild conditions; broad substrate tolerance. | Generates benzopyrazine derivatives with leishmanicidal and trypanocidal activity. | [54,60,61,62] |

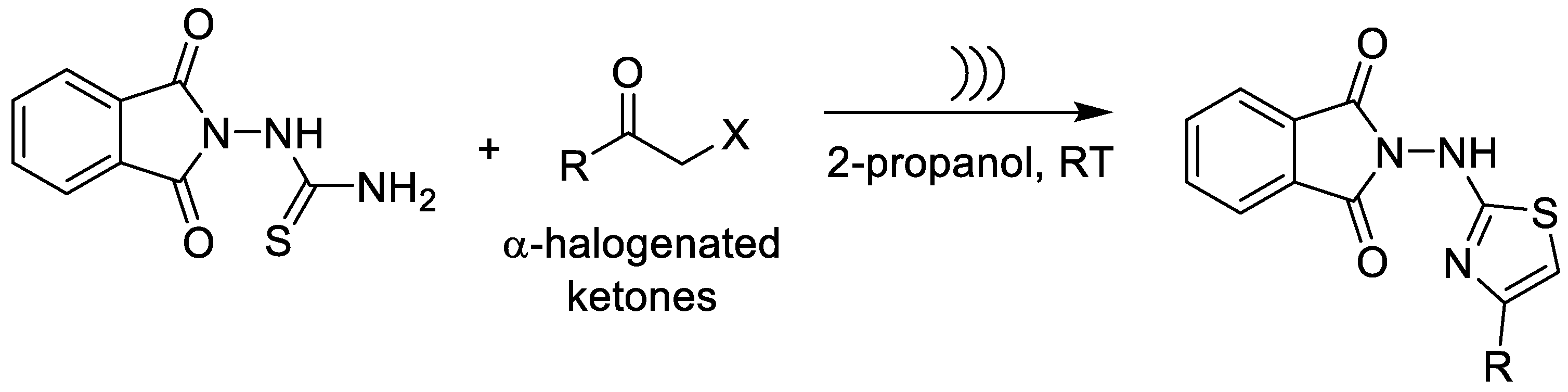

| Alternative Energy Sources/Ultrasound-Assisted Hantzsch Cyclization | Construction of phthalimido–thiazole derivatives via ultrasound-assisted Hantzsch cyclization at room temperature (1 h, 36–65% yield). | Mild conditions; reduced energy input; shorter reaction times vs. thermal processes; avoids harsh reagents; suitable for scale-up. | Derivatives showed potent trypanocidal and leishmanicidal activity; best hits comparable to benznidazole and showing favorable SI values. | [62,63] |

| Ultrasound-Assisted, Catalyst-Free Heterocycle Formation in Water | Eco-friendly synthesis of benzopyrazines in aqueous medium without additives, catalysts, or hazardous solvents; reaction completed in ~3 min. | Very high yields (>92%); no catalyst or toxic solvent required; excellent functional-group tolerance; minimal waste. | Benzopyrazine analogs exhibited activity against L. mexicana and T. cruzi, with potencies comparable to miltefosine and nifurtimox. | [64] |

| Alternative Energy Sources/Comparative Use of Ultrasound vs. Microwave for Imidazoline Construction | Construction of imidazoline derivatives using ultrasound (20 min) or microwave (40 min), outperforming conventional heating (4–5 h). | Major reduction in reaction time; high yields (60–80%); lower energy consumption; milder conditions; compatibility with diverse substituents. | Several imidazolines displayed IC50 < 1 µg/mL against L. mexicana and promising activity against T. cruzi; some derivatives exhibited very high selectivity (SI > 100). | [65] |

| Waste Prevention/Solvent-Free One-Pot Approaches (Mechanochemistry) | Solvent-free mechanochemical synthesis of 2,4-diphenylquinolines via multicomponent reaction using FeCl3. | Solvent-free; reduced energy consumption; fewer purification steps; high atom economy; efficient one-pot route. | Quinoline scaffolds are key in drugs for malaria, TB, parasites, and viruses. | [66,67,68,70] |

| Use of Alternative Solvents and Catalysts (Ionic Liquids) | Multicomponent synthesis of tetrasubstituted imidazoles using [BMIM][BF4] under microwave irradiation and solvent-free conditions. | Recyclable medium; high yields (84–89%); short time (10–12 min); metal-free/solvent-free possible. | Imidazole-containing drugs treat HAT, Chagas disease, fungal infections, and other NTDs. | [72,73,74,76]; |

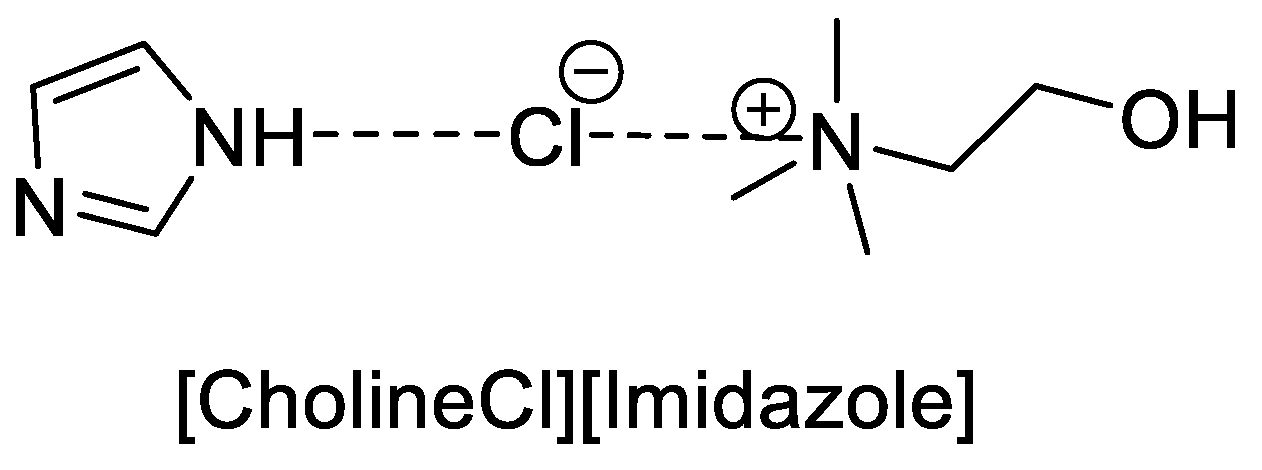

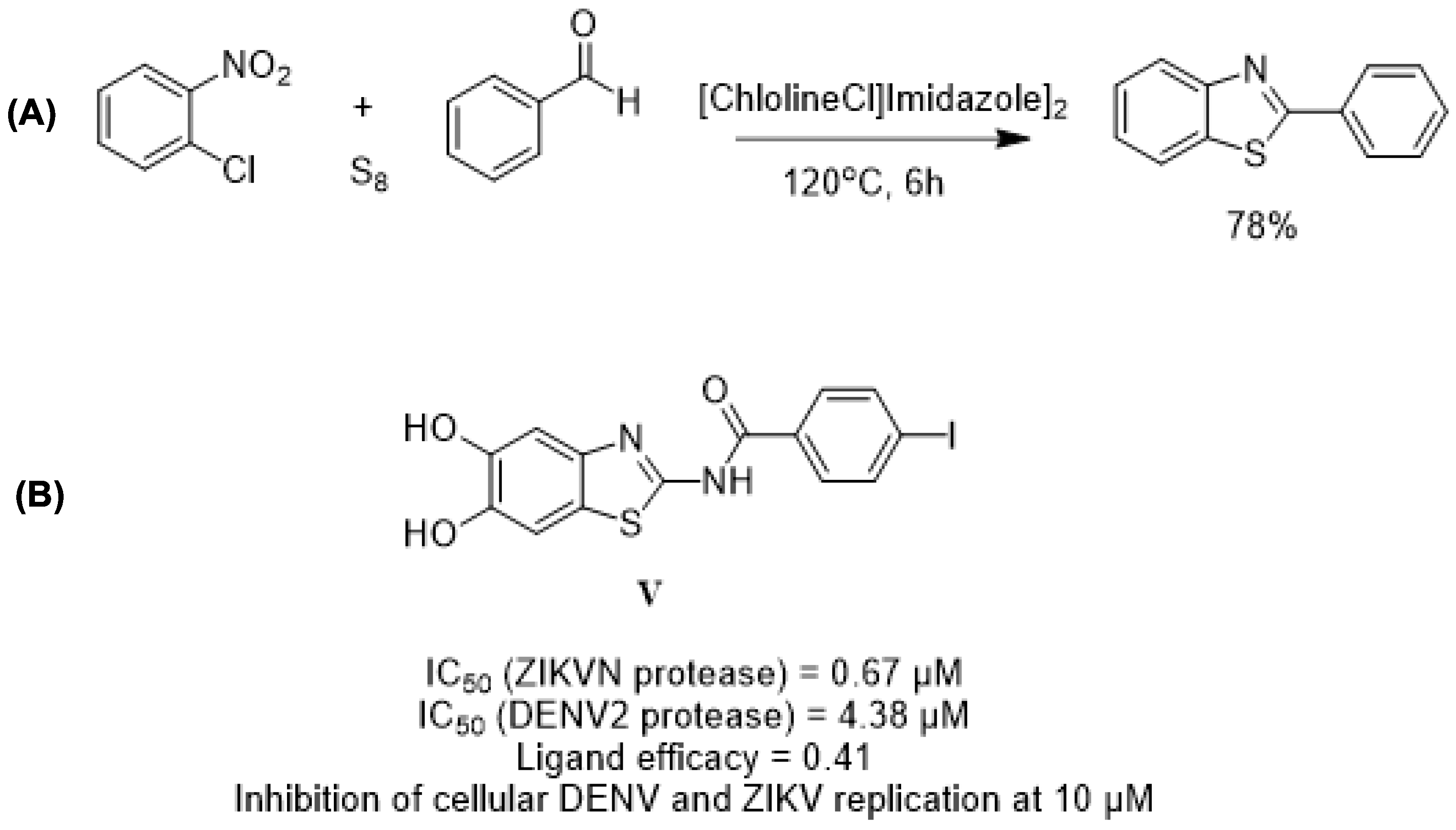

| Benign, Biodegradable Solvents (Deep Eutectic Solvents—DESs) | DES-catalyzed synthesis of 2-phenylbenzothiazoles using CholineCl/Imidazole DES under solvent-free conditions. | Biodegradable, low-cost medium; solvent-free; tunable catalytic environment; high yields; low environmental impact. | Benzothiazole derivatives showed antiparasitic and antiviral activity relevant for NTD discovery. | [78,79,80,81] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Péret, V.A.C.; de Oliveira, R.B. Green Strategies for the Synthesis of Heterocyclic Derivatives with Potential Against Neglected Tropical Diseases. Reactions 2025, 6, 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/reactions6040066

Péret VAC, de Oliveira RB. Green Strategies for the Synthesis of Heterocyclic Derivatives with Potential Against Neglected Tropical Diseases. Reactions. 2025; 6(4):66. https://doi.org/10.3390/reactions6040066

Chicago/Turabian StylePéret, Vinícius Augusto Campos, and Renata Barbosa de Oliveira. 2025. "Green Strategies for the Synthesis of Heterocyclic Derivatives with Potential Against Neglected Tropical Diseases" Reactions 6, no. 4: 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/reactions6040066

APA StylePéret, V. A. C., & de Oliveira, R. B. (2025). Green Strategies for the Synthesis of Heterocyclic Derivatives with Potential Against Neglected Tropical Diseases. Reactions, 6(4), 66. https://doi.org/10.3390/reactions6040066