The Little Ice Age and Colonialism: An Analysis of Co-Crises for Coastal Alaska Native Communities in the 18th and 19th Centuries

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Sugpiat of Kodiak: Indigenous Values as Resilience

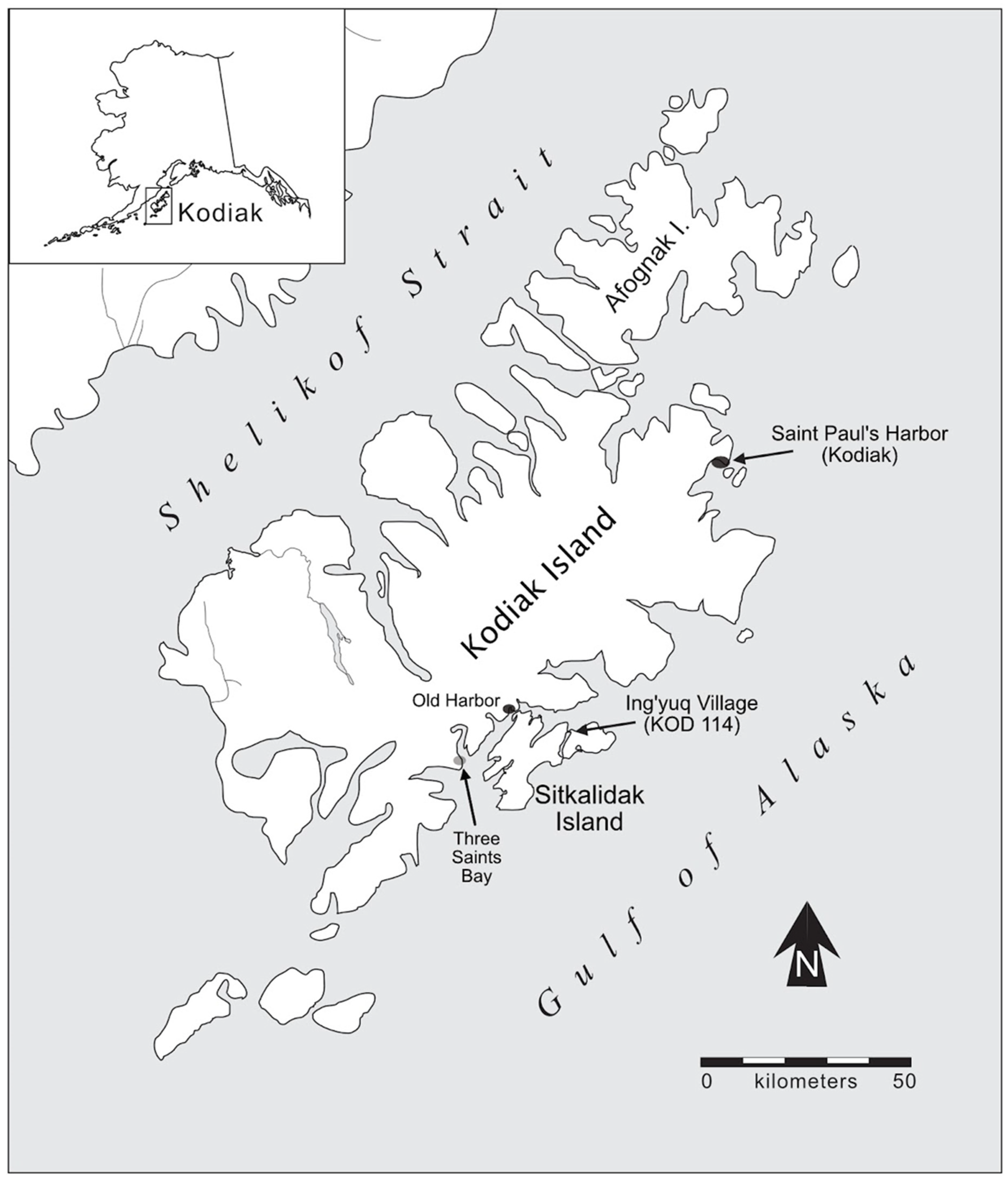

2.1. Kodiak Sugpiaq History

2.2. Kodiak Sugpiaq Values

3. Adapting to Uncertainty and Taking Sugpiaq History Seriously

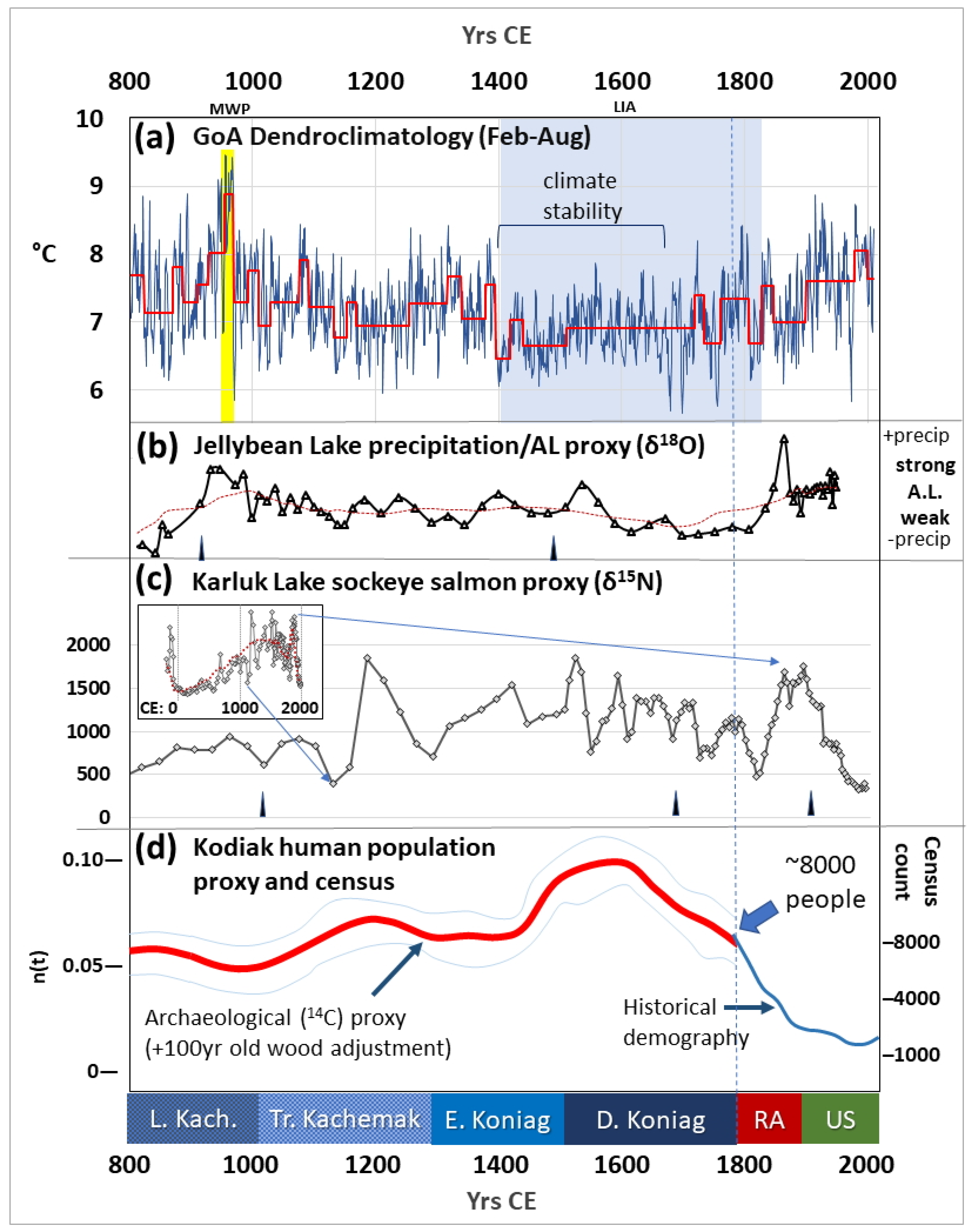

3.1. Climate and Ecological Change in the Gulf of Alaska

3.2. Risk, Resilience and Koniag Historical Ecology

3.3. Evaluating the Climate Predictions

4. Russian Colonialism and Sugpiaq Survivance

4.1. Indigenous Approaches to Climate Change and Colonialism

- a.

- Procedural injustice (Indigenous communities having diminished say in development decisions),

- b.

- Containment (restricting Indigenous mobility), and

- c.

- Settler centralization (making colonial needs and desires the focus of activities, creating dependence on colonial institutions or distributors).

4.2. Enacting Sugpiaq Survivance During the Russian Colonial Period

5. Conclusions

- Refinement of chronological precision in archaeological dating over the past millennia to clarify the timing of social and cultural changes in relation to climate regime shifts. This is coupled with the need for more archaeological data, in general, from Developed Koniag period sites.

- Evaluation of possible stewardship strategies developed by Sugpiaq ancestors both during the interval of peak population (when productive habitats would have experienced their highest rates of harvest) and under the increasingly unpredictable climates in the century before Russian arrival. Clearly resolving uncertainties surrounding the old wood offset in the paleodemographic population model is needed to determine when the population decline truly started—either before or at the inception of Russian colonization.

- Clarification of the evolving role of women in Koniag and colonial-era Sugpiaq villages, in terms of their flexible engagement in harvest and processing activities.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Alutiiq and Sugpiaq are equivalent ethnonyms. In the local language, Sugpiaq means “a real person”, while Alutiiq is an Indigenized version of the Russian term “Aleut” (based initially on lack of distinction between Unangan (Aleut) and Sugpiaq groups). Both Alutiiq and Sugpiaq are widely used and accepted by Indigenous people in the Kodiak Archipelago today. |

| 2 | We use Rodionov’s “Regime Shift Detection” plug-in for Excel that identifies statistically significant amplitude deviations in the running mean of a time series (https://www.pmel.noaa.gov/arctic-zone/bering-sea-indicators/regimes/; accessed 11 August 2022). Parameterization in regime shift analysis has huge influence over the resulting regime shift patterns. For this analysis, we have tuned the parameters to reflect regime shifts at the two times in the late 20th century (1977 and 1998) when climate shifts correlate with the most significant marine ecological changes in the Northeast Pacific. Those shifts had major implications for marine food webs and fisheries. The model, projected back to the start of the series 1200 years ago, should then capture changes with at least comparable ecosystems effects. Tuning parameters used for the regime shift analysis are: Target p = 0.05, cutoff length = 20 years, Huber tuning constant = 5. |

| 3 | The curve illustrated in Figure 2d is smoothed just enough to remove century and shorter-scale anomalies indistinguishable from calibration artifacts. Without a method to attach population values to radiocarbon measurements, the model does not include a scale of absolute population. Instead the curve is better at representing trend inflections (increase or decrease) in occupational intensity. Also, for the North Pacific Rim, and indeed anywhere that archaeologists have historically run dates on charcoal from long-lived wood samples, we must assume an old wood bias in the source dates. We attempt to mitigate this bias using information about the average age of living trees studied by forest biologists in the source region. In Figure 2d, we use a +100-year correction based on research the authors conducted, with colleagues, to estimate this error for the Sea of Okhotsk region [47]. This may need to be revised for the Gulf of Alaska if the re-dating of the Kal’unek site [48], which calculated an average offset of 250 years, is representative of the old wood offset for the region. There are statistical and functional reasons to consider 250 years to be an exagerated offset, so we stick to the +100 year adjustment here. |

References

- Lightfoot, K.G.; Gonzalez, S.L. The study of sustained colonialism: An example from the Kashaya Pomo homeland in northern California. Am. Antiq. 2018, 83, 427–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, S.L.; Panich, L.M. Situating Archaeological Approaches to Indigenous-Colonial Interaction in the Americas: An introduction. In The Routledge Handbook of the Archaeology of Indigenous-Colonial Interaction in the Americas; Panich, L.M., Gonzalez, S.L., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, E.R. Europe and the People Without History; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzhugh, B. The Evolution of Complex Hunter-Gatherers: Archaeological Evidence from the North Pacific; Kluwer Academic-Plenum Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Steffian, A.F.; Saltonstall, P.; Yarborough, L.F. Maritime Economies of the Central Gulf of Alaska After 4000 BP. In The Oxford Handbook of the Prehistoric Arctic; Friesen, T.M., Mason, O., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2016; pp. 303–322. [Google Scholar]

- Steffian, A.F. (Ed.) Imaken Ima’ut: From the Past to the Future: Seventy-Five Hundred Years of Kodiak Sugpiaq/Alutiiq History; Alutiiq Museum and Archaeological Repository: Kodiak, AK, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, D.W. Kodiak Island: The Later Cultures. Arct. Anthropol. 1998, 35, 172–186. [Google Scholar]

- Vizenor, G. (Ed.) Survivance: Narratives of Native Presence; University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, NE, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Acebo, N.P. Survivance Storytelling in Archaeology. In Routledge Handbook of the Archaeology of Indigenous-Colonial Interaction in the Americas; Panich, L.M., Gonzalez, S.L., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 468–485. [Google Scholar]

- Mishler, C. Black Ducks & Salmon Bellies: An Ethnography of Old Harbor and Ouzinkie, Alaska; Donning Co. Pub: Virginia Beach, VA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Saltonstall, P. Ancestral Alutiiq/Sugpiaq Life. Alutiiq Museum & Archaeological Repository, Difficult Discussions Project. (Video 1). Available online: https://alutiiqmuseum.org/alutiiq-people/history/our-stories/ (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Black, L.T. Russians in Alaska, 1732–1867; University of Alaska Press: Fairbanks, AK, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Black, L.T. The Russian Conquest of Kodiak. Anthropol. Pap. Univ. Alsk. 1992, 24, 165–182. [Google Scholar]

- Knecht, R.A.; Haakanson, S.; Dickson, S. Awa’uq: Discovery and Excavation of an 18th Century Alutiiq Refuge Rock in the Kodiak Archipelago. In To the Aleutians and Beyond: The Anthropology of William S. Laughlin; Frohlich, B., Harper, A.B., Gilberg, R., Eds.; The National Museum of Denmark: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2002; Volume 20, pp. 177–191. [Google Scholar]

- Shelikhov, G.I. A Voyage to America, 1783–1786; Pierce, R.A., Ed.; Ramsay, M., Translator; Limestone Press: Kingston, ON, Canada, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, H.K.; Pestrikoff, A.; Swenson, T. Braided Storytelling as a Method in Archaeology: Reimagining the Sugpiaq Past Through Story. Am. Anthropol. 2025, 127, 581–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slezkine, Y. Arctic Mirrors: Russia and the Small Peoples of the North; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Lisianski, Y. A Voyag. Round World Years 1803, 1804, 1805, and 1806; John Booth: London, UK, 1814. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, D.W. On a Misty Day You Can See Back to 1805: Ethnohistory and Historical Archaeology on the Southeastern Side of Kodiak Island, Alaska. Anthropol. Pap. Univ. Alsk. 1987, 21, 105–132. [Google Scholar]

- Crowell, A.L.; Lührmann, S. Alutiiq Culture: Views from Archaeology, Anthropology, and History. In Looking Both Ways: Heritage and Identity of the Alutiiq People; Crowell, A.L., Steffian, A.F., Pullar, G.L., Eds.; University of Alaska Press: Fairbanks, AK, USA, 2001; pp. 21–72. [Google Scholar]

- Fortuine, R. Chills and Fever: Health and Disease in the Early History of Alaska; University of Alaska Press: Fairbanks, AK, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Drabek, A.S. Liitukut Sugpiat’stun (We Are Learning How to be Real People): Exploring Kodiak Alutiiq Literature Through Core Values. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Alaska, Fairbanks, AK, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kawagley, A.O. A Yupiaq Worldview: A Pathway to Ecology and Spirit; Waveland Press: Long Grove, IL, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Carothers, C.; Black, J.; Langdon, S.J.; Donkersloot, R.; Ringer, D.; Coleman, J.; Gavenus, E.R.; Justin, W.; Williams, M.; Christiansen, F.; et al. Indigenous peoples and salmon stewardship: A critical relationship. Ecol. Soc. 2021, 26, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunn, E.S.; Johnson, D.R.; Russell, P.N.; Thornton, T.F. Huna Tlingit Traditional Environmental Knowledge, Conservation, and the Management of a “Wilderness” Park. Curr. Anthropol. 2003, 44 (Suppl. S5), S79–S103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langdon, S.J. Tidal Pulse Fishing: Selective Traditional Tlingit Salmon Fishing Techniques on the West Coast of the Prince of Wales Archipelago. In Traditional Ecological Knowledge and Natural Resource Management; Menzies, C., Ed.; University of Nebraska Press: Lincoln, NE, USA, 2006; pp. 21–46. [Google Scholar]

- Langdon, S.J. Traditional Knowledge and Harvesting of Salmon by HUNA and HINYA TLINGIT. Fisheries Information Service Report 02-104. U.S.; Department of Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, Office of Subsistence Management: Anchorage, AK, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton, T.F.; Moss, M.L.; Butler, V.L.; Hebert, J.; Funk, F. Local and Traditional Knowledge and the Historical Ecology of Pacific Herring in Alaska. J. Ecol. Anthropol. 2010, 14, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Chya, D.; Steffian, A.F. (Eds.) Unigkuat-Kodiak Alutiiq Legends; Alutiiq Museum and Archaeological Repository: Kodiak, AK, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Pullar, G.L. Ethnic Identity, Cultural Pride, and Generations of Baggage: A Personal Experience. Arct. Anthropol. 1992, 29, 182–191. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman, D.S.; Axford, Y.L.; Henderson, A.C.G.; McKay, N.P.; Oswald, W.W.; Saenger, C.; Anderson, R.S.; Bailey, H.L.; Clegg, B.; Gajewski, K.; et al. Holocene Climate Changes in Eastern Beringia (NW North America)—A Systematic Review of Multi-Proxy Evidence. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2016, 147, 312–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiles, G.C.; D’Arrigo, R.D.; Barclay, D.; Wilson, R.S.; Jarvis, S.K.; Vargo, L.; Frank, D. Surface Air Temperature Variability Reconstructed with Tree Rings for the Gulf of Alaska over the Past 1200 Years. Holocene 2014, 24, 198–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, L.; Abbott, M.B.; Finney, B.P.; Burns, S.J. Regional Atmospheric Circulation Change in the North Pacific During the Holocene Inferred from Lacustrine Carbonate Oxygen Isotopes, Yukon Territory, Canada. Quat. Res. 2005, 64, 21–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodionov, S.N.; Bond, N.A.; Overland, J.E. The Aleutian Low, storm tracks, and winter climate variability in the Bering Sea. Deep Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 2007, 54, 2560–2577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, H.L.; Kaufman, D.S.; Sloane, H.J.; Hubbard, A.L.; Henderson, A.C.G.; Leng, M.J.; Meyer, H.; Welker, J.M. Holocene atmospheric circulation in the central North Pacific: A new terrestrial diatom and δ18O dataset from the Aleutian Islands. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2018, 194, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagashima, K.; Addison, J.; Irino, T.; Omori, T.; Yoshimura, K.; Harada, N. Aleutian Low Variability for the Last 7500 Years and Its Relation to the Westerly Jet. Quat. Res. 2022, 108, 161–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finney, B.P.; Alheit, J.; Emeis, K.C.; Field, D.B.; Gutiérrez, D.; Struck, U. Paleoecological Studies on Variability in Marine Fish Populations: A Long-Term Perspective on the Impacts of Climatic Change on Marine Ecosystems. J. Mar. Syst. 2010, 79, 316–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chya, D.I. Kasaakat Tekicata When the Russians Arrived. In Imaken Ima’ut: From the Past to the Future: Seventy-Five Hundred Years of Kodiak Sugpiaq/Alutiiq History; Steffian, A.F., Ed.; Alutiiq Museum and Archaeological Repository: Kodiak, AK, USA, 2024; Chapter 4; pp. 74–103. [Google Scholar]

- Mantua, N.J.; Hare, S.R. The Pacific Decadal Oscillation. J. Oceanogr. 2002, 58, 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trites, A.W.; Miller, A.J.; Maschner, H.D.G.; Alexander, M.A.; Bograd, S.J.; Calder, J.A.; Capotondi, A.; Coyle, K.O.; Lorenzo, E.D.; Finney, B.P.; et al. Bottom-up forcing and the decline of Steller sea lions (Eumetopias jubatus) in Alaska: Assessing the ocean climate hypothesis. Fish. Oceanogr. 2007, 16, 46–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowell, A.L.; Arimitsu, M. Climate Change and Pulse Migration: Intermittent Chugach Inuit Occupation of Glacial Fiords on the Kenai Coast, Alaska. Front. Environ. Archaeol. 2023, 2, 1145220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzhugh, B.; Brown, W.A.; Misarti, N.; Takase, K.; Tremayne, A.H. Human Paleodemography and Paleoecology of the North Pacific Rim from the Mid to Late Holocene. Quat. Res. 2022, 108, 123–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Litzow, M.A.; Hunsicker, M.E.; Bond, N.A.; Burke, B.J.; Cunningham, C.J.; Gosselin, J.L.; Norton, E.L.; Ward, E.J.; Zador, S.G. The changing physical and ecological meanings of North Pacific Ocean climate indices. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 7665–7671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finney, B.P.; Gregory-Eaves, I.; Douglas, M.S.V.; Smol, J.P. Fisheries Productivity in the Northeastern Pacific Ocean over the Past 2200 Years. Nature 2002, 416, 729–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, W.A. Through a Filter, Darkly: Population Size Estimation, Systematic Error, and Random Error in Radiocarbon-Supported Demographic Temporal Frequency Analysis. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2015, 53, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, W.A. The Past and Future of Growth Rate Estimation in Demographic Temporal Frequency Analysis: Biodemographic Interpretability and the Ascendance of Dynamic Growth Models. J. Archaeol. Sci. 2017, 80, 96–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, H.; Gamble, E.; Holman, D.; Fitzhugh, B. Statistically Limiting the Error Associated with Old Wood in Archaeological Dating: A Case Study from the Kuril Islands. In Proceedings of the Symposium Presentation, Society for American Archaeology Annual Meeting, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 30 March 2017. [Google Scholar]

- West, C.F. A revised radiocarbon sequence for Karluk-1 and the Implications for Kodiak Island Prehistory. Arct. Anthropol. 2011, 48, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knecht, R.A. The Late Prehistory of the Alutiiq People: Culture Change on the Kodiak Archipelago from 1200–1750 AD. Ph.D. Dissertation, Bryn Mawr College, Bryn Mawr, PA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Halstead, P.; O’Shea, J.M. (Eds.) Bad Year Economics: Cultural Responses to Risk and Uncertainty; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Goland, C. Field scattering as agricultural risk management: A case study from Cuyo Cuyo, Department of Puno, Peru. Mt. Res. Dev. 1993, 13, 317–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowley-Conwy, P.; Zvelebil, M. Saving it for later: Storage by prehistoric hunter-gatherers in Europe. In Bad Year Economics: Cultural Responses to Risk and Uncertainty; Halstead, P., O’Shea, J.M., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1989; pp. 40–56. [Google Scholar]

- Wiessner, P. Risk, reciprocity and social influences on! Kung San economics. In Politics and History in Band Societies; Leacock, E., Lee, R., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1982; pp. 61–84. [Google Scholar]

- O’Shea, J.M. Coping with scarcity: Exchange and social storage. In Economic Archaeology: Towards an Integration of Ecological and Social Approaches; Sheridan, A., Bailey, G., Eds.; BAR International Series, No. 96; BAR Publishing: Oxford, UK, 1981; pp. 167–183. [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson, L.H. Ecological resilience—In theory and application. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 2000, 31, 425–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leslie, P.; McCabe, J.T. Response Diversity and Resilience in Social-Ecological Systems. Curr. Anthropol. 2013, 54, 114–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halstead, P.; O’Shea, J. A Friend in Need is a Friend Indeed: Social Storage and the Origins of Social Ranking. In Ranking, Resource and Exchange: Aspect of the Archaeology of Early European Society; Renfrew, C., Shennan, S., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1982; pp. 92–99. [Google Scholar]

- Steffian, A.F.; Saltonstall, P.G. Markers of identity: Labrets and social evolution on Kodiak Island, Alaska. Alsk. J. Anthropol. 2001, 1, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, R.H.; Knecht, R.A. Archaeological Research on Western Kodiak Island, Alaska: The Development of Koniag Culture. In The Late Prehistoric Development of Alaska’s Native People; Shaw, R.D., Harritt, R.K., Dumond, D.E., Eds.; Monograph Series, 4; Alaska Anthropological Association: Anchorage, AK, USA, 1988; pp. 356–453. [Google Scholar]

- Partlow, M.A. Salmon Intensification and Changing Household Organization in the Kodiak Archipelago. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, H.K. Stories of Sugpiaq Survivance: Uncovering Lifeways at Ing’yuq Village. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Kopperl, R.E. Cultural Complexity and Resource Intensification on Kodiak Island, Alaska. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- West, C.F. Human Dietary Response to Climate Change and Resource Availability. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bradford, K.; Wilson, K.B.; Hodgson, E.; Moore, J.W.; Reid, A.; Salomon, A.; Van Der Minne, C.; Armstrong, J.; Alex, K.; Benson, R.; et al. Indigenous stream caretaking for Pacific salmon: Ancestral lifeways to guide restoration, relationships, rights, and responsibilities. FACETS 2025, 10, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whyte, K. Indigenous Climate Change Studies: Indigenizing Futures, Decolonizing the Anthropocene. Engl. Lang. Notes 2017, 55, 153–162. Available online: https://muse.jhu.edu/article/711473 (accessed on 8 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Whyte, K. Settler Colonialism, Ecology, and Environmental Injustice. Environ. Soc. 2018, 9, 125–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whyte, K.; Talley, J.L.; Gibson, J.D. Indigenous Mobility Traditions, Colonialism, and the Anthropocene. Mobilities 2019, 14, 319–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marino, E. The Long History of Environmental Migration: Assessing Vulnerability Construction and Obstacles to Successful Relocation in Shishmaref, Alaska. Glob. Environ. Change 2012, 22, 374–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kretzler, I.; Gonzalez, S. On Listening and Telling Anew: Possibilities for Archaeologies of Survivance. Am. Anthropol. 2023, 125, 310–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, T.D.; Panich, L.M. (Eds.) Archaeologies of Indigenous Presence; University Press of Florida: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Atalay, S. Community-Based Archaeology: Research with, by, and for Indigenous and Local Communities; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Atalay, S. Indigenous Science for a World in Crisis. Public Archaeol. 2020, 19, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wylie, A. A Plurality of Pluralisms: Collaborative Practice in Archaeology. In Objectivity in Science: New Perspectives from Science and Technology Studies; Padovani, F., Richardson, A., Tsou, J.Y., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 189–210. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, R.T. Empire of Extinction: Russians and the North Pacific’s Strange Beasts of the Sea, 1741–1867; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Luehrmann, S. Alutiiq Villages under Russian and US Rule; University of Alaska Press: Fairbanks, AK, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, R.T. A. F. Kashevarov, the Russian-American Company, and Alaska Conservation. Alsk. J. Anthropol. 2013, 11, 51–68. [Google Scholar]

- Lightfoot, K.G.; Martinez, A.; Schiff, A.M. Daily Practice and Material Culture in Pluralistic Social Settings: An Archaeological Study of Culture Change and Persistence from Fort Ross, California. Am. Antiq. 1998, 63, 199–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowell, A.L. Ethnicity and Periphery: The Archaeology of Identity in Russian America. In The Archaeology of Capitalism in Colonial Contexts; Croucher, S.K., Weiss, L., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 85–104. [Google Scholar]

- Woodhouse-Beyer, K. Gender Relations and Socio-Economic Change in Russian America: An Archaeological Study of the Kodiak Archipelago, Alaska, 1741–1867 A.D. Ph.D. Dissertation, Brown University, Providence, RI, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Black, L.T. The Round the World Voyage of Hieromonk Gideon 1803–1809; Limestone Press: Kingston, ON, Canada, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Chya, D. Alutiiq History and Russian Occupation. Alutiiq Museum & Archaeological Repository, Difficult Discussions Project. (Video 2). Available online: https://alutiiqmuseum.org/alutiiq-people/history/our-stories/ (accessed on 8 November 2025).

- Alutiiq Museum. Alutiiq Sugpiaq Nation. Available online: https://alutiiqmuseum.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/AlutiiqSugpiaqNation2022.pdf (accessed on 9 November 2025).

- Herz, N. The Last Skipper in Ouzinkie: How Gulf of Alaska Villages Lost Their Native Fishing Fleets. Alaska Public Media Northern Journal, 5 February 2025. Available online: https://alaskapublic.org/news/economy/2025-02-05/the-last-skipper-in-ouzinkie (accessed on 8 November 2025).

| Named Traditions | Time Range | Primary Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Ocean Bay | 7500–4000 cal BP | Small and seasonally mobile groups who hunted sea mammals and harvested fish and other marine resources. Early Ocean Bay people may have lived primarily in tents and specialized in chipped stone tools. They armed their darts and spears with microblades made by a technique reminiscent of terminal Pleistocene traditions in Alaska and Siberia. Later Ocean Bay groups commonly lived in small sod houses and their lithic industry became dominated by ground slate tools. |

| Kachemak | 4000–700 cal BP | The first durable villages appear at the start of this period. Labor-intensive net fishing and processing strategies for the first time make it possible to store summer harvests for consumption in the winter lean season. Around 2500 years ago, increased crowding may have promoted growing social unrest and political competition. People started marking status with conspicuous displays of art (e.g., elaborately decorated stone lamps) and jewelry made from exotic materials. The earliest defensive sites appear a few hundred years before the end of this period. |

| Koniag | 700 cal BP to CE 1784 | The apogee of Kodiak Indigenous political development and population growth, this period saw the expansion of sod-house villages to unprecedented size (50+ houses not uncommon), gradual transition to multi-room houses and co-residence of extended kin groups. Heads of large families emerged as influential chiefs who directed the labor of kin and slaves captured in war-raids against distant enemies. Russians make first contact in 1763, but have limited influence on Kodiak people until they return 21 years later. |

| Russian Colonial Period | CE 1784–1867 | Many Sugpiaq people were defeated at the Awa’uq defensive site in Southeast Kodiak and villages around the archipelago were coerced into hunting sea otter and fur seals for the Russian fur trade. Sugpiaq men were conscripted into work parties and sent ever greater distances to harvest furs. Women were often compelled to provide food, clothing, and services for the Russian fur traders and many married Russian and Siberian colonists. Native populations plummeted through harsh treatment, disease and relocation. By 1840, only 7 Native villages remained out of well over 100 before contact. |

| U.S. Colonial Period | CE 1867-present | The U.S. purchase of Alaska in 1867 led to fevered exploration of the territory for exploitable raw materials. Around Kodiak, salmon and remaining sea otters drew intense interest. Commercial fishing, canneries, and hatcheries were established around Kodiak by the 1890s. Through the mid-20th century, boom and bust fishing fortunes flooded communities with cash then crippled them with unemployment. Political organization at local, state, and federal levels settled land claims in 1971, and Native Corporations were formed to develop the resource capital of allocated lands. Cultural heritage is playing a strong role in revitalization. Archaeology, language revival, and oral history have become tools for restoring Sugpiaq pride. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Miller, H.K.; Fitzhugh, B. The Little Ice Age and Colonialism: An Analysis of Co-Crises for Coastal Alaska Native Communities in the 18th and 19th Centuries. Heritage 2025, 8, 499. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8120499

Miller HK, Fitzhugh B. The Little Ice Age and Colonialism: An Analysis of Co-Crises for Coastal Alaska Native Communities in the 18th and 19th Centuries. Heritage. 2025; 8(12):499. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8120499

Chicago/Turabian StyleMiller, Hollis K., and Ben Fitzhugh. 2025. "The Little Ice Age and Colonialism: An Analysis of Co-Crises for Coastal Alaska Native Communities in the 18th and 19th Centuries" Heritage 8, no. 12: 499. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8120499

APA StyleMiller, H. K., & Fitzhugh, B. (2025). The Little Ice Age and Colonialism: An Analysis of Co-Crises for Coastal Alaska Native Communities in the 18th and 19th Centuries. Heritage, 8(12), 499. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage8120499