1. Introduction

Heritage is a complex and contested term in literature and in practice. While Hewison described it as a ‘word without definition’ [

1] there are a number of assumptions in its use. It is almost synonymous with ‘inheritance’ suggesting a historical truism and rigidity in the manifestation of the past. As people come and go, heritage remains, passed from one generation to the next. In reality, which elements of the past are preserved and in what way is a form of conscious curation. This is demonstrated in this paper’s case study of the Dobbins Inn, Carrickfergus, Northern Ireland. The medieval tower house-cum-Georgian house was restored ‘to an original castle façade’ in 2019 as part of the Townscape Heritage Initiative (THI), funded by the National Lottery Heritage Fund, Mid and East Antrim Borough Council and the property owners [

2]. The THI was a five-year funding programme (2016 to 2021) to regenerate the historic Carrickfergus Conservation Area. The scheme aimed to: preserve and enhance buildings located within the town’s conservation area; stimulate and support the economic regeneration of Carrickfergus by enhancing its distinctive historic character; and raise awareness of the rich built and cultural heritage of Carrickfergus through training and educational activities [

3]. This paper will evaluate the restoration of Dobbins in relation to the aims of the THI, while setting it in its wider heritage context, particularly that of authenticity and the drive to achieve it.

By choosing what tangible or intangible heritage is preserved, certain associated narratives are selected for commercialised or politicalised agendas. Heritage is a carefully curated story, multi-threaded, with different actors speaking to different audiences. This is further complexified when the narratives selected by one group are not the same as those selected by another. Academics, heritage workers, community groups, politicians and local businesses, to name a few, may each read a different narrative within any one form of heritage. These differences may stem from what is perceived as the dominant, most important or authentic narrative.

Despite ambiguity in meaning, heritage is considered to have intrinsic value (cultural, economic and political) and those which are more ‘authentic’ have greater value [

4]. Therefore, heritage is utterly entangled with the ‘authenticity craze’ [

5]. Early discourse surrounding authenticity portrayed a sense of achievable stability, which has since been mostly surpassed by recent scholarly work. Recent academic arguments describe authenticity as dynamic, performative, culturally and historically contingent, and relative [

5]. However, the reality within the heritage sector more broadly is that authenticity sits uncomfortably between stable and unstable. The idea that authenticity is stable is detected in the ways in which it is actively sought, praised and denied from perspectives varying from architecture, landscape and tourism. At the Dobbins and beyond, it is something desired and is invariably deemed ‘a Good Thing’ [

6].

Authenticity is an international heritage norm and embedded within heritage organisations. The ‘test of authenticity’ was included in the early preparatory meetings of UNESCO’s World Heritage Committee (WHC) at Morges, 1976, and Paris, 1977 [

7]. Its persistent use since has not resulted in a universal understanding and arguably there was never a clear consensus among those who perpetuated the notion. Ambiguity is evident in the WHC’s working documents of 1978 to 1983, with issues surrounding the ‘notion of authenticity’ described [

8]. The confusion surrounding, or different understandings of, authenticity have resulted in an increase in its use in uncritical, sweeping ways. As Stovel notes, ‘“This property is undeniably authentic…” was a favourite ICOMOS statement’ [

7]. This paper will show how different understandings of authenticity can be perceived in the case study of the Dobbins restoration.

Recent research relating to heritage has allowed a more nuanced understanding, shifting emphasis from the tangible to the many overlapping and contradictory narratives to which they relate or generate. This paper adds to the shift in discourse by considering the Dobbins as the starting point of the discussion, not an end in and of itself. Despite greater consensus that heritage is the process of passing on as well as what is passed on, in Western Europe there remains a preponderance of considering heritage as material rather than something recreated or practised [

9]. In an attempt to avert this pitfall, this paper combines the physical analysis of the building with the associated intangible heritages that have grown around the building and town, in order to connect the tangible with meanings and identities.

When the Nara document was signed in 1994, it was agreed that societies are rooted in ‘particular forms and means of tangible and intangible expression’ and they ‘should be respected’ [

10]. This was a flagship moment, broadening the emphasis from heritage as solely the legacy of the past to include it as a living expression of today’s culture [

11]. This allowed a greater scope of heritage forms to meet the criteria for conservation and preservation; however, it also perpetuated the authenticity debate [

11]. Today’s culture is created in response to a growing variety of motivations, with the tourism economy increasingly benefiting from the heritage sector. Therefore, there is greater contestation surrounding the definition of authentic, what is considered ‘real’ in contrast to ‘staged’ authenticity, and its appropriateness as a tool by which we measure the value of heritage. When authenticity is used as the basis for restoration it brings the multiple understandings to the fore, as at the Dobbins.

Heritage is frequently described as a palimpsest, a particularly enticing metaphor for archaeologists, like this paper’s authors, as it implies the chronological superimposition of story upon story that can be read if examined closely enough [

12,

13]. Useful to a degree, however, the use of palimpsest may limit our analysis of the connectivity between the past and the present: the temporal relationships are not necessarily a straight line but a dynamic and entangled web. Bartolini suggests a movement away from a linear reading of heritage towards considering brecciation [

12]. Breccia is a coarse rock comprising a variety of smaller deposits that have been consolidated. Bartolini uses the term to demonstrate how an urban landscape is at once an entity and compilation of fragments with different origins and of no chronological sequence [

12]. This term is more applicable than palimpsest when reviewing the restoration of the Dobbins. As will be shown, the restoration work demonstrates a desire for authenticity that fused the past and present together to create enmeshed heritage.

2. The Dobbins: The Hidden Tower House

Approaching Carrickfergus from Belfast, the capital of Northern Ireland, one is faced with the past. An Anglo-Norman castle, built by John de Courcy

c.1170, with a striking basalt edifice sits upon a rocky promontory on the east-facing coastline of the town. It is located in Ulster, the northernmost province of Ireland. Throughout the medieval period, Carrickfergus was a principal stronghold of the Anglo-Normans and later the English crown. De Courcy was ousted by Hugh de Lacy in the early 13th century and the latter commenced a significant building phase in the town, including additions to the castle’s defences [

14]. Following the colonisation of Ulster, the town walls were constructed (1609–1615), which demarcate the current conservation area [

15]. The walls and the area within are considered ‘an area of special architectural or historic interest’, with the built heritage a contributor to the town’s unique character [

15]. Carrickfergus comprises several scheduled monuments, including the town walls, the Anglo-Norman castle, listed buildings such as St Nicholas’ Church, probably founded by de Courcy, and Dobbins Inn.

By the end of the 17th century, Belfast had surpassed Carrickfergus as a premier town and growth slowed considerably. This was countered in the mid-to-late 20th century, when the town experienced an economic resurgence with the establishment of major manufacturing operations. This occurred alongside the Northern Ireland conflict, commonly known as the Troubles, which encouraged people to settle beyond Belfast further from the epicentre of the violence. Between 1950 and 1980 the population trebled to 27,000 residents. The rise was followed by a period of decline and approximately 5000 jobs were lost when three manufacturing companies closed in the 1980s. The ebb and flow of economic and residential activity have left their mark on the townscape. While the town’s core is medieval in origin, the appearance is predominantly late 18th to mid-19th century. The buildings are typically domestically scaled terraces comprising two or three storeys over what are now ground-floor shops, creating a space of Georgian character interrupted by a number of 20th-century replacements and additions. The latter are the result most markedly of the 1950–1980s boom. The Anglo-Norman castle and the low-rise town it dominates are separated by a considerable four-lane carriageway, which appears to almost create two distinct, even conflicting, areas: one medieval, one Georgian.

Dobbins Inn is located on High Street, fewer than 90 m from the Castle (

Figure 1). It is thought to be one of several tower houses built in the late-medieval period in Carrickfergus. Tower houses were a type of stone-built castle, considerably smaller than the sprawling Anglo-Norman castles, and indeed, serving a different purpose. They were built by a broad social and cultural spectrum [

16]; their small size meant they were within the financial reach of the lay and religious, lords, emerging gentry and merchants in both rural and urban areas [

17]. Discourse on tower houses has moved away from a once-popular militarised interpretation towards an appraisal that includes their role in social advancement, economic development and display, alongside a recognition of their comfortable and peaceful living arrangements [

16,

17]. The Dobbins Inn will not be referred to as a castle here to avoid confusion with the Anglo-Norman Carrickfergus Castle.

The Dobbins had not been investigated formally prior to its restoration, despite Carrickfergus being one of the most archaeologically explored towns in Ireland. Before its restoration, the Dobbins presented as a terraced, two-bay, three-storey building and looked little like a tower house (

Figure 2). Rectangular on plan, the rear is abutted by a complex of extensions and returns, occupying what appears to be a medieval burgage plot, while the principal elevation faces to the south. Irish tower houses display strong homogeneity in form, with little variation perceived even when compared with their Scottish and English counterparts [

17]. This uniformity is due, in part, to structural requirements. In order to build a tall and narrow structure comprising at least three stories, a slight batter was required (walls thicker at the base). It was this thickness of the ground-floor walls that hinted that the Dobbins may be older than its Georgian appearance. However, this did not extend beyond the ground floor, indicating that the building had been truncated with later fabric comprising the first and second floors.

Tower house entrances have been recorded at ground level, first-floor level and both. At the Dobbins, access was granted through a barn-style, timber-panelled, left-of-centre door, with replacement fanlight over, flanked by two timber casements to the right and a single casement to the left. These apertures were much larger than would be found at a tower house, which would utilise small and sparse windows to retain a strong, solid base with larger and more frequent windows reserved for the upper floors. The first- and second-floor apertures at the Dobbins were symmetrically arranged, with two windows per bay on the first floor and one larger per bay on the second floor. All the windows were square headed and generally uPVC. In tower houses, the ground floor was often vaulted, with vaults on other floors commonplace as they acted as a fire-break. No vault was present at the Dobbins. A crenelated parapet and wall-walk invariably adorned the top of tower houses, with a pitched wooden roof. These are the commonly found features of tower houses; however, differences are to be expected and indeed are accepted. Which floor was vaulted, the door level and other variations seem to be dependent on regional preferences [

16,

17]. No two were exactly the same and with distance, regional differences became more pronounced. At the Dobbins, truncation, several alterations and mid-20th century render made identifying these features difficult.

The 20th-century render created substantial damp issues; therefore, it was removed with consent from Listed Buildings (Historic Environment Division of Northern Ireland) and funded in part by the owners and the THI Education Programme. The removal process began at the join of the roof and second floor, with the contractors moving downwards, stripping the render by hand to reveal brickwork. The render proved to be of a sand/cement mix that was fused to the bricks that lay underneath, thus its removal destroyed many of the bricks’ faces. The bricks were identified as Carrickfergus brick due to their soft nature and inclusions, which allowed the second floor to be dated as late Georgian or first half of the 19th century (

Figure 3). However, quoin stones on the elevation’s left-hand side were Cultra sandstone, similar to that at Carrickfergus Castle, suggesting the survival of earlier fabric. The red Carrickfergus brick sat upon a layer of slate used as a levelling material prior to the former’s construction. Below the slate was roughly coursed basalt that increased in thickness as the height decreased: the evidence of a medieval building finally revealed. None of the apertures appeared to relate to the basalt construction, as evident through the use of brick to fill surrounding gaps. Any masonry scars of earlier windows were lost in the building’s re-fenestration.

The revelation of the medieval fabric led to successful acquisition of THI funding for restoration, which was subsequently completed in 2019. The majority of the work involved the removal of the plaster on the façade, new aperture configuration and addition of lime render. The work was carried out by local traditional tradespeople, using conservation-grade, locally sourced materials. The final façade was presented as a medieval tower house following extensive research, dendrochronological analyses and open conversation between the owners, architects and Listed Buildings. Plans were proposed for both a medieval and Georgian façade; however, it was concluded that for the benefit of the building, the business and the ongoing economic revitalisation of the town, the restoration would promote the building’s medieval narrative to the exclusion of its Georgian alterations (

Figure 4).

Restoration is the most commonly used term in the publicity of the Dobbins work; however, it may not accurately describe what was undertaken. Restoration is generally considered to be the return of a degraded heritage to an original state. Conservation, however, is generally accepted as local-level, physical activity conducted in relation to heritage management and may be more fitting to the work undertaken at the Dobbins [

18]. It is underpinned by legal frameworks, policy and professional standards. Through the process of conservation, a building is being asked to perform a certain narrative [

19]. It may be that a single narrative is bolstered through a building’s conservation or that a new narrative is imprinted upon it. Therefore, choice is an unavoidable bifurcation in conservation, requiring the forgoing of non-selected alternatives [

18]. While this is described as a ‘simple, and perhaps seemingly self-evident point’ [

18], it is crucial to be aware that conservation is rooted in an either/or selection process. This creates a battle between two distinct paradigms, which are not only mutually exclusive but contradictory. This was evident in the plans for the Dobbins restoration, as two distinct proposals were submitted reflecting two different responses to the inherent selection process. The differences between the plans were too great for a compromise to be sought: the selection process of conservation generates ideas that cannot be synthesised.

Preservation is different from conservation, as it has been considered traditionally as protection of heritage [

18]. However, this approach and indeed the understanding of preservation has been altered by developments in the heritage sector. Expectations of heritage are changing as a greater variety of heritages are consumed in an increasing variety of ways; while heritage managers and providers are dependent on these consumers to make heritage financially, socially or politically viable. Therefore, preservation is subject to the whim of various stakeholders, distancing it from its traditional definition. As with conservation, it requires a choice: preservation protects what heritage for whom? The work on the Dobbins could be considered any of these processes: conservation, preservation or restoration. Indeed, all three terms are used throughout the literature created, particularly the public-facing coverage. Regardless of how they are described and despite a misused confluence with inheritance, these processes cannot pass on an accurate or complete story of the past; rather, a version of the past is selected, a winner is chosen considering numerous stakeholders’ points of view. It is further complexified when authenticity is considered something within reach, achievable through conservation, preservation or restoration, as will be demonstrated through the Dobbins Inn.

Authenticity is used to describe something actual, genuine and original, within or without the heritage context. In the example of the Dobbins, genuine or original may refer to its fabric or its use. Through the restoration, the multiple layers of fabric from the medieval through to the 20th century have been altered or removed to some degree; thus rendering the building inauthentic. However, this definition can be extended in two ways in relation to heritage. Firstly, something is authentic if it is truly what it claims to be; likewise, something based on accurate and reliable facts is considered authentic [

9,

20]. These tangible yet nuanced definitions will be used to analyse the authenticity of the Dobbins, which in return will provide a deeper understanding of the term.

3. Discussion

The Dobbins was restored to present a medieval tower-house façade, while rectifying building issues such as damp in the process. The evidence to suggest that the Dobbins was once a tower house derives from a number of sources. Those already discussed were the basalt and Cultra sandstone and the wall thickness. This indicates that the lower level of the building was medieval; however, it was cartographic evidence that extended this to classify the building as a tower house. Carrickfergus is one of few towns in Ireland for which a number of maps from the late 16th century survive. The first in the sequence of maps, created by an anonymous map-maker, dates from

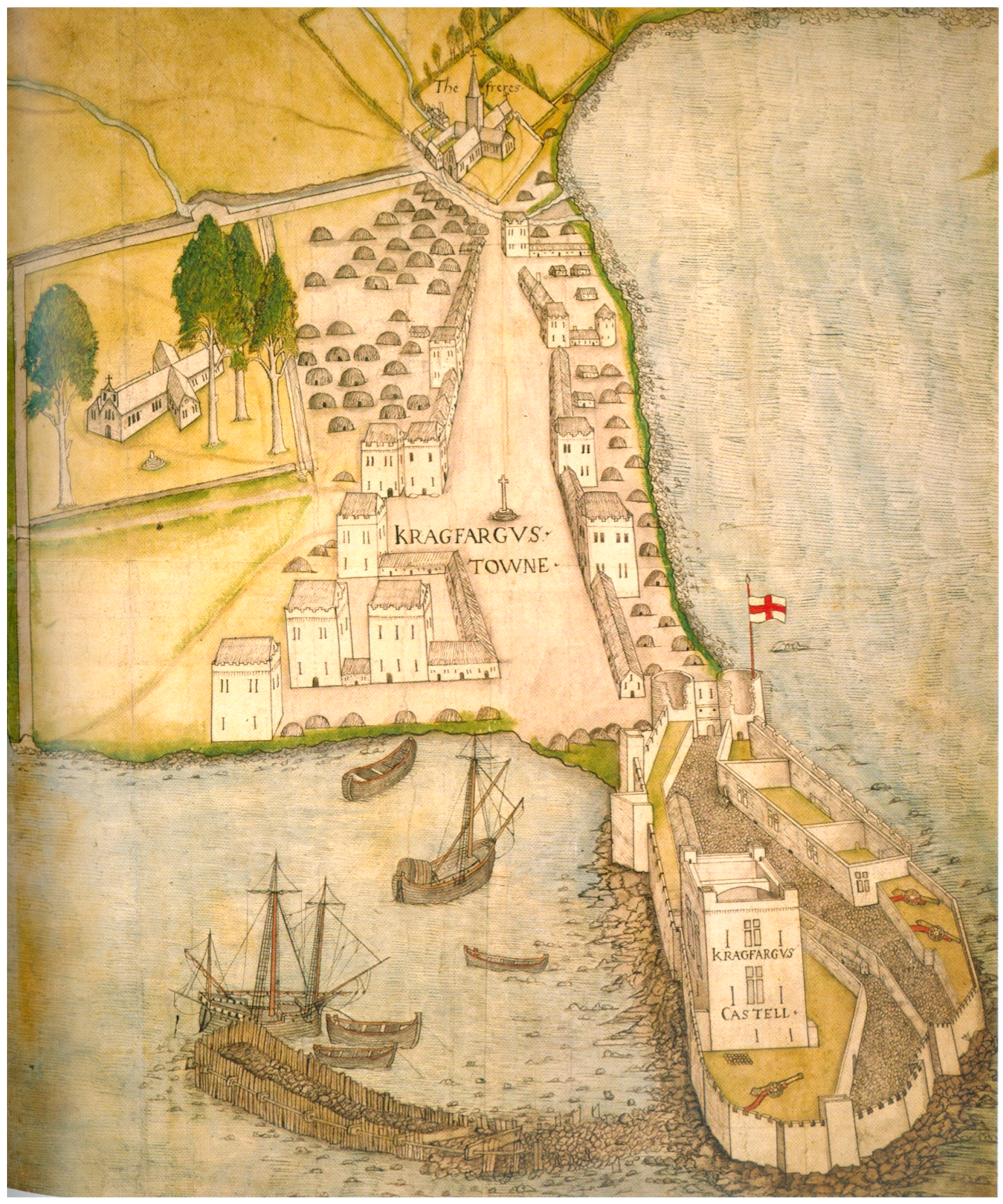

c.1560 (

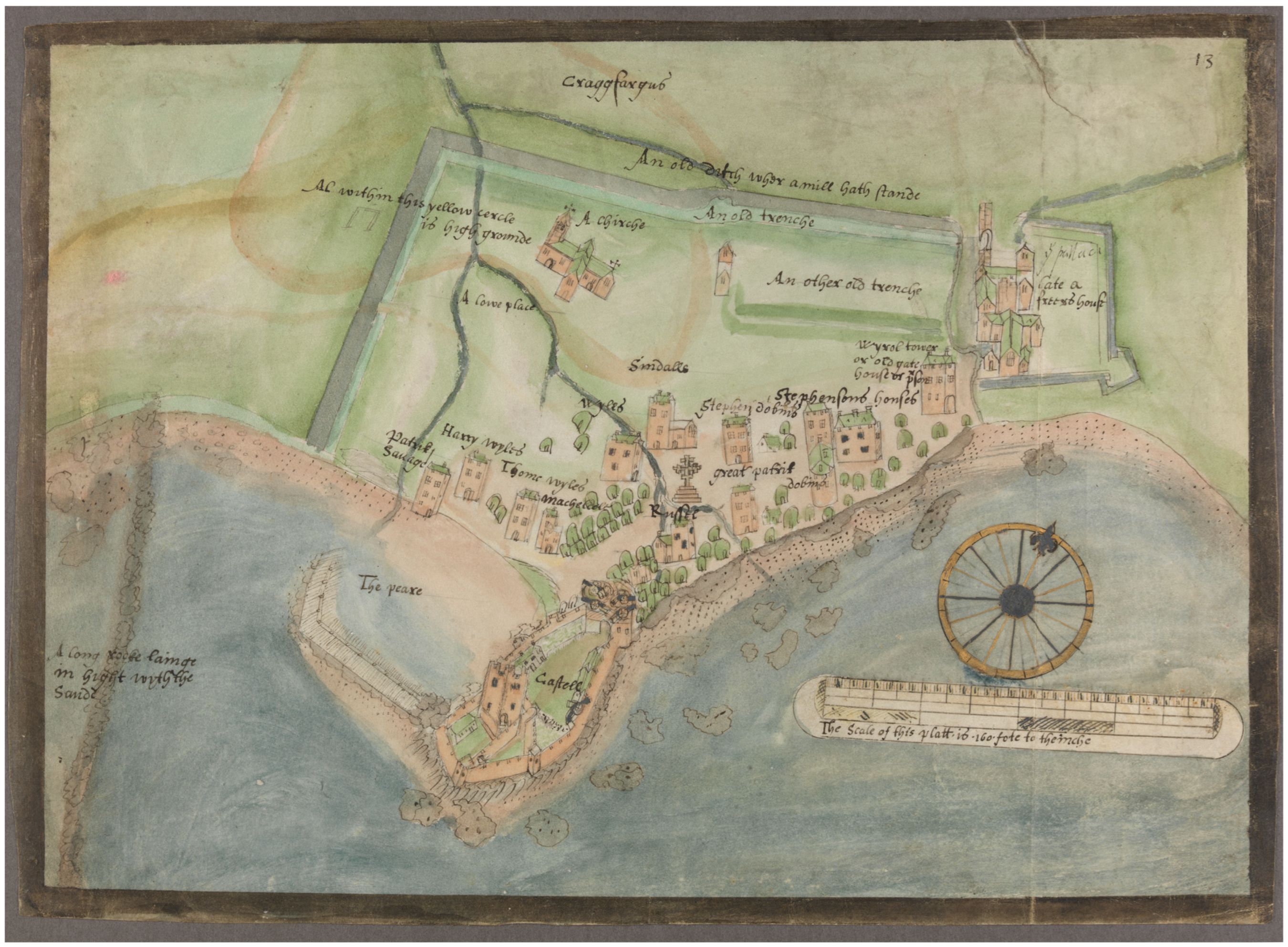

Figure 5). The castle dominates, yet three other building types can be viewed: twelve stone-built tower houses, all rectangular bar one cylindrical; one- or two-story terraces flanking the street; and a substantial number of beehive cabins. When Robert Lythe was tasked with identifying the town’s defences later in the 1560s, the map shows the town similarly dense with tower houses (

Figure 6). In the 16th century, Carrickfergus was a well-established and thriving urban centre, with Scottish, English and European trade networks [

21]. The variety of buildings suggests a merchant elite, and probably others of Anglo-Norman and later English descent, living in the tower houses with a considerable Irish population in the surrounding cabins. The difference in comfort and prestige between the building types is clear. Stephen Dobbin is listed as the owner of one of the tower houses on what would become High Street, and he may have been involved in this economy. This was the first mention of the Dobbin family, inciting the link that would remain four centuries later.

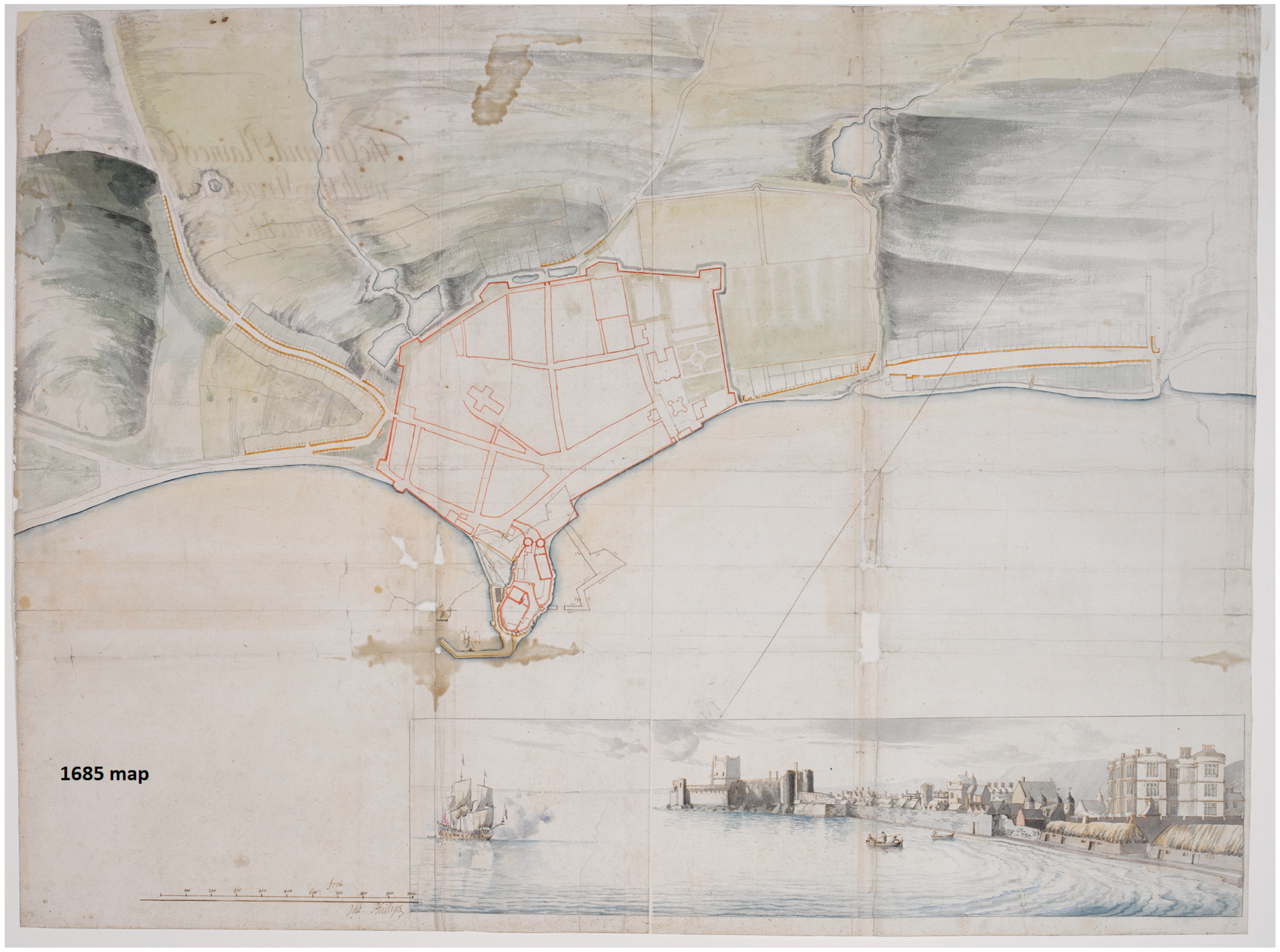

The cartographic evidence may also provide alternative interpretations. In the late 17th century, Thomas Philips was tasked, as Lythe, with surveying Carrickfergus (

Figure 7). This depiction shows a period of expansion, with the Irish and Scottish quarters extending beyond the town walls. A development phase could suggest a later date for the basalt fabric surviving at the Dobbins Inn, as tower houses were built well into the 17th century elsewhere in Ireland. Despite the ambiguity, it is likely the Dobbins Inn predates this expansion. The thickness of the walls suggests an earlier construction, which is further supported by later cartographic evidence in which the plot size is visible. The linear plot denoted on O’Kane’s 1821 map is indicative of a medieval burgage plot: long, narrow strips of land comprising the main dwelling, outbuildings such as stores and stables, and a kitchen garden. It indicates the extent of the land associated with the Dobbins and suggests a medieval date of creation, possibly contemporary with the Anglo-Norman design of the town. Carbon dating analysis was possible due to the restoration; timbers from the fireplace and window lintel returned a date of

c.1530 [

24]. This supports the evidence of late-medieval activity at the Dobbins Inn but should not be overextended to support its classification as a tower house.

What is clear from the cartographic evidence is the ownership of a tower house by Stephen Dobbin in the approximate area of today’s Dobbins Inn. Historical sources both support and contradict this. Leases held by the Carrickfergus Burghers, or Council, from 1608 onwards contain the following extract to the Dobbin family:

James Dobbin 2nd July 1627. Deed of one Castle called Dobbins Castle North west side of the street leading to Castle Warragh [

26].

The connection is not immediately apparent; however, the ‘street leading to Castle Warragh’ refers to what is now High Street leading north-east towards the present town hall (

Figure 1). This suggests that, as depicted in the maps from the previous century, a tower house on High Street was in Dobbin ownership. The issues around authenticity and whether today’s Dobbins Inn is what it claims to be surround connecting this evidence to the known structure. Some historical sources provide descriptions that may be linked to extant remains. The most useful known references to the building’s earlier appearance are derived from the OS Memoirs (1840), which describe:

…one of the original houses, shown in plan as Dobbins, is still in perfect preservation. It is on the east side of the street and in line with the other houses, from which it is distinguished merely by two small square turrets, one at each angle in front [

27].

Further in the memoirs:

The oldest house in the town is that in which the public bakery is kept, opposite the Corporation Arms Hotel, and it is said to be part of an ancient castle belonging to the Dobbin family. Portions of the projecting turrets are still visible in the front of the house [

27].

These descriptions only confuse matters: the current Dobbins Inn is located towards the south-west end of the north-side of High Street. Furthermore, it is markedly set in from the row of other buildings. High Street itself runs south-west to north-east, although this only goes so far to justify any confusion in the spatial descriptions. Where the descriptions are consistent is in describing turrets; however, the cartographic evidence suggests crenulations without corner turrets were in place. Cartographic sources are demonstrative depictions of the town yet are generally considered inaccurate for illustrating building details. For example, what appears to be the door of the tower house presented as the Dobbins shifts from the street-side in Lythe’s map to a side-alley (now filled if ever present) in a representation from 1596 [

28]. The maps were not created to provide a precise representation of the buildings depicted. However, in the earliest known map of

c.1560, the details of crenulations are very specific. In Ireland, tower houses had either Irish crenulations, which were stepped, or English, which were square. The

c.1560 depiction shows both types present in Carrickfergus, as would be expected in an English stronghold, with English crenulations at what is considered the Dobbins. Considering the strength of this evidence, the Dobbins was restored with a crenulated parapet rather than turrets. It may be the case that the Dobbins had crenulations and turrets, with only the former depicted in the maps and only the latter mentioned in the OS Memoirs. Regardless, both were removed and replaced with a Georgian elevation, as demonstrated on postcards from the late 19th/early 20th centuries. This is supported by the late-Georgian date of the Carrickfergus brick on the second floor of the building, which must have swiftly succeeded the OS descriptions.

Whether the Dobbins Inn is original, what it claims to be, or whether that claim is based on reliable facts, and ergo is authentic, can be debated continually. It is clear that definitions that focus on tangible authenticity provide little clarification. The use of ‘original’ in the traditional definition can be extended from fabric to function. This allows more ephemeral consideration of authenticity; however, function is an unpopular indicator of authenticity, as continuation of use is viewed as less pertinent when compared to maintaining the original fabric. This was highlighted in a working document for the first session of the WHC (1987). The interpretation of authenticity was challenged by those who did not consider that it necessarily entailed maintaining the original function which, to ensure its preservation, often had to be adapted [

7,

8]. This is true of the Dobbins. Constructed as a late-medieval tower house functioning as an administrative centre and merchant’s home, it may have been a bakery in the 19th century [

27] before being converted into barracks and used as such until

c.1950 [

29]. Following this, it became a hotel, which it remains today. While the use of the space has changed, the social function of the building has remained fairly consistent. Tower houses were built to reflect identity and display the increasing wealth of the town and family. In that sense, the Dobbins has not changed due to the restoration. As a hotel, the building is a symbol of the town’s economy. Likewise, it continues to display identity: that of Carrickfergus’ medieval past and touristic present. Therefore, despite this being an unpopular way to ascribe authenticity, it is useful here. Considering function beyond the utilitarian allows more intangible conceptions of authenticity to be included in the evaluation [

30]. This paper will now turn to explore the motivation for restoration and whether a drive for authenticity can be detected. In turn, this will assist the understanding of authenticity at the Dobbins and beyond.

4. The Drive for Authenticity

A desire for authenticity may have underpinned the restoration at the Dobbins. This is implied in two ways: the language surrounding the process states that the Dobbins was ‘restored to an original castle façade’ and ‘restored to the original 15th century… look’ [

2]; secondly, the act of restoration itself. In terms of language, ‘original’ is used extensively in the available information and widespread media coverage. It is evident that what was considered ‘original’ was deemed the correct or true appearance of the Dobbins:

…a new frontage was erected causing [the building] to lose its appearance of a tower house for over 150 years, which has now been restored’ [

2].

This language suggests a corrective exercise was undertaken to allow the tower house to first be found, then brought back. These stable undertones temporally anchor the correct appearance of the building in the medieval period, with the later activity seemingly inappropriate or of less importance. The building’s Georgian past is concealed by the language used (and concealed physically by the medieval-esque façade); therefore, it becomes an inferior heritage and undesirable narrative. This could be considered ‘negative curation’ or ‘heritage erasure’ [

31] as it removes the right of the building to exist in its unique complexity [

32,

33]. The stability detected in the language suggests a desire to erase complexity and the ‘plurality’ of the building [

33]; in turn, this indicates a desire for stable authenticity underpinning the restoration. The desire for stable authenticity may be related to aesthetics, similar to the ‘stylistic restoration’ common in the 19th century and the early 20th century [

34]. This was rooted in valuing heritage based on its form or style and enhancing it through whatever means necessary to create a unified, or stable, narrative [

34].

The very process of restoration further implies a drive for authenticity as it means to bring back the ‘former, original or normal’ [

34]. This initially reinforces a notion of stable authenticity; however, what is considered original is susceptible to opinions and perceptions. This creates a consideration of authenticity in contrast to a stable and achievable understanding.

Cohen proposed that authenticity is a ‘socially constructed concept’ [

35], while others argue that it is a judgement or value attributed by its observers [

36,

37,

38]. These less tangible and fixed understandings allow us to consider that authenticity was the motivation for the Dobbins restoration, yet its very nature cannot be perceived by all audiences. Considering a negotiable and contextual definition shifts this discussion away from considering authenticity in the Dobbins’ tangible remains. Instead, its authenticity can be attributed through the viewer’s judgement and valuation in a meaning-making process. To extend this further, judgement and valuation are dynamic, thus adding flux to the designation process. Therefore, what was once considered authentic may not always be the case. This allows two considerations: any heritage can be considered authentic by some and the perception of what is deemed authentic can change. This may serve as a warning to avoid major alterations to heritage: in time, will the restoration of the Dobbins be regretted and subject to de-restoration? This was a symptom of many heritage monuments restored in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Viollet-le-duc, the architect behind many restorations including the walls of Carcassonne, argued that he was creating something ‘in an ideal state that may have never existed at a given point in time’ [

39]. His restorations were ‘creations’, implying newness, based on his perception of authenticity [

11]. His ideals were considered too extreme by some contemporaries. Ruskin referred to his work as ‘a destruction out of which no remnants can be gathered: a destruction accompanied with false description of the thing destroyed’ [

40]. Viollet-le-Duc’s desire for his notion of authentic erased what may have been considered authentic by others: the parallels with the Dobbins are clear.

This evaluation demonstrates that authenticity rests somewhere between stable and unstable and has tangible connotations yet is not inherent, it is something we ascribe. As a dynamic attribute, it can be ascribed then withdrawn; likewise, it can be denied then assigned. It seems the motivation for the Dobbins restoration derived from understanding the complexity of authenticity. The process bolstered the stable authentic, while at the same time complied with a preconceived ideal and preference. Furthermore, it seems to have been accepted that there is a longer-term, meaning-making process intertwined with authenticity. Rather than a palimpsest upon which one story has been erased in favour of another, as breccia, the restoration is an amalgamation of the different stories, the existing medieval and the medieval-esque. This evaluation suggests that by striving for authenticity, the restoration has allowed the new to become part of the heritage. This discussion will now turn to explore the possible reasons behind this.

5. Why Strive for Authenticity?

Carrickfergus is a tourist destination, sustained by the town’s proximity to Belfast, 18 km to the south, and good transport links. Heritage tourism can be considered as the motivation to present a place, representing the past and/or present, to tourists [

41]. Authenticity is seen as a crucial motivation for tourists selecting a destination [

41,

42]. However, it is clear that this authenticity may be staged to suit the needs of the tourist, and indeed the local community [

43], with the former ‘usually forgiving about these matters’ [

44].

The Anglo-Norman castle is the main tourist attraction of Carrickfergus, drawing local and international culturally curious audiences. It is considered one of the best-preserved Anglo-Norman castles in Ireland [

21] and has long fuelled the town’s tourist industry. While there are extensive remains from Carrickfergus’ 18th and 19th centuries, these do not feature in the touristic narrative to the same extent as the medieval and early 17th century heritage, such as St Nicholas’ Church and the town walls. This suggests there is a dominant touristic narrative that is temporally anchored. The restoration bolstered the Dobbins’ medieval past and in doing so created another medieval focal point in Carrickfergus adding to this narrative. The result is a visual story of Carrickfergus’ medieval past characterised through the castle, church and now the Dobbins. It could be argued that demonstrating this medieval past would be hampered if the components did not appear like medieval things. If the Dobbins had not been restored, or had been restored to reflect its temporal plurality, it may have contributed to the town’s Georgian appearance, in turn boosting the early-modern narrative and shifting the emphasis away from the medieval.

It has been argued that tourist satisfaction relies more heavily on the perception of authenticity as opposed to what others may consider ‘actual’ authenticity [

41,

42]. If we consider the definition of ‘actual’ authenticity to mean the tangible and original prior to restoration [

41,

45], it appears that a perception of authenticity was of equal or more importance to the Dobbins restoration. Perceived authenticity allows audiences to glimpse a version of the past, one which complies with their imagined geography of the place or imagined associated narrative. Carrickfergus is promoted to tourists as a medieval town; therefore, it should look like one.

In striving to comply with the multiple layers of authenticity, there was inevitable discord. A distinction between the knowledge held by the community and tourists was created. The Carrickfergus community knew the Dobbins was restored and parts demonstrating the recent past were removed or re-covered. It could be argued that tourists must undertake extra effort to seek then understand this information, which they may not be willing to do as the perception of authenticity is central to their satisfaction [

41]. Therefore, one group is aware of, although can no longer see, the ‘actual’ authenticity, while the tourists see only the staged. It could be argued that this is a perforated representation of Carrickfergus: the alternative heritage of the Georgian and 20th-century past omitted from the dominant narrative. While the omission of periods reflecting the ebb and flow of the economy, successes in manufacturing as well as depression and decline and abandonment, is not surprising, it may deny the tourists the right to a fuller experience. In order to counter this knowledge gap, information boards are provided and, in time, further information will be provided in the Carrickfergus Museum.

This knowledge gap and the community’s awareness of the ‘actual’ meant the restoration was not accepted universally by the Carrickfergus community, thus extending the battle that emerged between the two proposals to the finished restoration project. When the façade was revealed the reactions, particularly on social media, were strongly divided, including calls to return the building to its Georgian appearance. This was despite the public call for input prior to the restoration, as per planning protocol, to which no objections were submitted. This criticism was the result of socially constructed authenticity. For many locals, the authentic Dobbins was that which was recognisable and familiar, thus at odds with the current appearance. The absence of this knowledge allows tourists to more readily accept the building as part of the medieval landscape. The Dobbins reinforces the medieval narrative of the town; in return, the other extant medieval heritage supports the Dobbins as an authentic reflection of the medieval past. It may be expected and so not questioned. Therefore, for the tourists, authenticity is contextual. The community’s knowledge of the ‘actual’ cannot be maintained indefinitely. Over time, the actual and staged become enmeshed and the distinction collapses [

46]; therefore, the community will accept the restoration into their perception of authenticity. This solidifies the narrative created by the restoration.

Some of the negative responses to the restoration may have been due, in part, to poor knowledge of the late-medieval past. For example, expectations of a medieval building may include bare masonry, whereas rendered or white-washed were actually the norm. There is a clear relationship between this altered understanding of the past and the in/authentic representations of medieval buildings; however, this is beyond the scope of this paper. This is not a Carrickfergus-specific symptom [

47], rather a much larger issue embedded in country-wide educational limitations. Education was a central aim of the THI; therefore, there were considerable outreach initiatives, including a presentation area in the Civic Centre, providing an overview of the restoration and the vast late-medieval knowledge generated by the research process. These initiatives had the added benefits of closing the knowledge gap and addressing the negative responses. This effectiveness of this demonstrates the negotiable quality of authenticity.

It is argued that tourism motivated the drive for authenticity at the Dobbins’ and a second stimulus will now be discussed: that of the town’s identities. Recognition of the medieval identity is evident in the restoration and the educational activities that followed it. However, Carrickfergus has a considerable yet fluctuating industrial past. The tangible evidence for this was rediscovered in the Dobbins in the form of the locally made, 19th-century brick. The restored appearance suggests that the industrial narrative was diminished in favour of the medieval, as discussed above. However, the restoration provided opportunities for training related to historic conservation practices and skills and utilised local craftworkers throughout. This bolstered the industrial identity of the town while conserving intangible industrial heritages. This intangible consideration allows another layer of authenticity to be viewed at the Dobbins, one that includes the relationship between heritage and intrinsic values [

48]. This is demonstrative of a ‘plurality in preservation’, in which the medieval is enmeshed with the industrial, as well as intangible values and narratives [

33,

49]. The restoration team appear to have considered the facets of identity and related intangible heritages extant within the town and used the restoration in a way to be beneficial to as diverse a group as possible.

6. Conclusions

The above discussion utilised a number of definitions of authenticity to analyse the restoration of the Dobbins. This paper has strived to demonstrate the complexity and dynamism of the term authenticity, building on the considerable discourse from a number of disciplines and applying this to the Dobbins. What has transpired initially appears as an unsatisfactory conclusion: it is both authentic and inauthentic. Rather than attempting to find one true definition to resolve this, this paper embraces this complexity. It has been argued that different groups will read the Dobbins in different ways and that this reading is unfixed.

The battle for authenticity required two proposals, one which favoured the Georgian architecture and one which, through restoration, highlighted the medieval past. In turn, different groups then viewed the results in both positive and negative ways, extending the conflicting and even combative undertones from the plans to the end result. This example demonstrates that authenticity is a myriad of complexities and contradictions comprising various components, including tangible, intangible, stable and dynamic, and when this is a motivation for restoration there is complex discomfort enmeshed within the result.

Our aim of detecting the need for authenticity then delivering a deeper understanding of it has been achieved although, as discussed, it is not striving to be conclusive nor a terminus. This example highlights the need for even greater contextual discourse on authenticity and its intersection with heritage, tourism, archaeology and the built environment. One could even return to the concept of palimpsest and consider this example as another layer to aid understanding: contributing yet complexifying the picture.

Accepting the oscillation of authenticity could be extended to arguing for the term’s abandonment: why use a term with so little clarity? Firstly, as has been shown here, it is something craved within the heritage sector and beyond. It is interconnected with heritage tourism and funding, meaning its extraction from discourse would be ignorant rather than useful. Secondly, the different definitions need not be in contrast to one another but can be viewed as inclusions in the same unit. Much like how the Dobbins is the result of brecciation, with its past fused to the present, the term authenticity must comprise all the definitions included here and most likely many more.