Stille Nacht: COVID and the Ghost of Christmas 2020

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Christmas Markets in Germany

3. The Mercantile, Social and Experiential Dimensions of Christmas Markets

4. Restrictions and Limitations of Festivals under COVID-19 in 2020

4.1. Impact of COVID-19 on Christmas Markets

4.2. Augmented Christmas Markets and Virtual Reality

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Frevel, C. Geht es um mehr als Bratfett und Ballermann? Weihnachtsmärkte in Deutschland. Herder-Korrespondenz 2016, 70, 49–51. [Google Scholar]

- Spennemann, D.H.R.; Parker, M. The changing face of German Christmas Markets: Historic, mercantile, social and experiential dimensions. Heritage 2021, 4, 1821–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göbel, E.; Schramm, M. Konsum, Region und Weihnachtsmärkte. Dresdner Striezelmarkt und Nürnberger Christkindlesmarkt im Vergleich (1933–2000). Comparativ 2001, 11, 51–65. [Google Scholar]

- Hirschfelder, G. Kultur im Spannungsfeld von Tradition, Ökonomie und Globalisierung: Die Metamorphosen der Weihnachtsmärkte. Z. Volkskd. 2014, 110, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Wölfle, F.; Schnorbus, L. Weihnachtsmärkte-Charakterisierung der Besucher und Bedeutung Unterschiedlicher Faktoren für Diese. In IUBH Discussion Papers—Tourismus Hospitality; IUBH Internationale Hochschule: Erfurt, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, J.; Unglaub, H. Besucherbefragung Weihnachtsmarkt 2008—Ergebnisbericht [14/08]; Leipziger Statistik Und Stadtforschung: Leipzig, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Jürgens, U. Weihnachtsmarkt Siegen. Eine Besucheranalyse 2007. Siegen. Beiträge 2009, 13, 259–270. [Google Scholar]

- Kammerhofer-Aggermann, U.; Hiebl, E.; Keul, A.G.; Bachleitner, R.; Schreuer, M. Weihnachtsmärkte: Zentren der Sehnsüchte und des Tourismus. Tour. J. 2003, 7, 329. [Google Scholar]

- Himmelsbach, C. Eventmarketing am Beispiel des Städtischen Events Offenburger Weihnachtsmarkt. Bachelor’s Thesis, Ostfalia Hochschule für Angewandte Wissenschaften, Wolfenbüttel, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wirtschaftswoche. Umfrage. Weihnachtsmärkte: Deutsche mögen’s klein. Wirtschaftswoche, 5 December 2012. Available online: https://www.wiwo.de/unternehmen/dienstleister/umfrage-weihnachtsmaerkte-deutsche-moegens-klein/7480580.html(accessed on 11 August 2021).

- YouGov Team. Weihnachtsmarkt mit oder Ohne Fahrgeschäfte, Glühwein oder Kinderpunsch, 5 Grad Plus oder Minus. Available online: https://yougov.de/news/2016/11/21/weihnachtsmarkt-mit-oder-ohne-fahrgeschafte-gluhwe/ (accessed on 23 December 2020).

- Inhoffen, L. Drei Viertel Können sich Adventszeit ohne Weihnachtsmärkte nicht Vorstellen. Available online: https://yougov.de/news/2017/11/04/drei-viertel-konnen-sich-adventszeit-ohne-weihnach/ (accessed on 23 December 2020).

- Sonnenberg, A.-K. To-do-Listen bis Weihnachten. Available online: https://yougov.de/news/2019/12/05/-do-listen-bis-weihnachten/ (accessed on 23 December 2020).

- Wozel, H. Der Dresdner Striezelmarkt. Geschichte und Tradition des ä Ltesten Deutschen Weihnachtsmarktes; Husum Verlag: Husum, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Hartzog, L.S. Zwei Deutsche Weihnachtsmarkte: Dauer im Wechsel. Senior. Honors Thesis, Longwood University, FarmVille, VA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, T. Der Oberrhein als Wirtschaftsregion in Spätmittelalter und Früher Neuzeit. Grundsatzfragen zur Begrifflichkeit und Quellenüberlieferung. Vorträge Forsch. 2008, 68, 91–112. [Google Scholar]

- Stadt Hagen. Statistisches Jahrbuch Hagen 2008; Stadt Hagen: Hagen, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, J.; Vetterlein, U. Weihnachtsmärkte—ein boomender Faktor—Synergie oder Konkurrenz zum stationären Einzelhandel? Handel Im Fokus. Mitt. IfH 2003, 3, 173–180. [Google Scholar]

- Gansser, O.; Reich, C. FOM Weihnachtsumfrage 2020, Ergebnisse für Deutschland; ifes Institut für Empirie & Statistik, FOM Hochschule für Oekonomie & Management: München, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gansser, O. FOM Weihnachtsumfrage 2017. Ergebnisse—Einkaufsverhalten in Deutschland; Ifes Institut für Empirie & Statistik, FOM Hochschule für Oekomone & Management: Munich, Germany, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Gansser, O. Weihnachtsumfrage 2013—Einkaufsverhalten der Konsumenten in Deutschland in Bezug auf Weihnachtsgeschenke; KCS Kompetenz Centrum für Statistik und Empirie, FOM Hochschule für Oekonomie & Management: München, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- BDSM. Weihnachtsmärkte als Wirtschaftsfaktor für Kommunen und Tourismus in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland sowie dessen Beitrag zur Leistungssteigerung im mittelständischen Schaustellergewerbe und Markthandel; Bundesverband Deutscher Schausteller und Marktkaufleute: Bonn, Germany, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, G.; Weinert, S. Imoha-Studie: Weihnachtsmärkte als Wirtschaftsfaktor. Der Wochenmarkt. Hauszeitung Der Dmg Marktgilde 2002, 22, 6–7. [Google Scholar]

- Papke, G. Der Münchner Christkindlmarkt. Wirtschaftswert und Image; Referat für Arbeit und Wirtschaft: München, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Statement on the Second Meeting of the International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee Regarding the Outbreak of Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV); World Health Organisation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, E. Coronavirus cases recorded in Antarctica at Chilean research station. ABC News, 22 December 2020. Available online: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-12-22/coronavirus-cases-confirmed-in-antarctica/13007596(accessed on 11 August 2021).

- Kuebler, M.; Staudenmaier, R.; Pieper, O. Coronavirus begins shutting down public life across Germany. Deutsche Welle, 12 March 2020. Available online: https://www.dw.com/en/coronavirus-begins-shutting-down-public-life-across-germany/a-52743358(accessed on 11 August 2021).

- Deutsche Welle. What are Germany’s new coronavirus social distancing rules? Deutsche Welle, 22 March 2020. Available online: https://www.dw.com/en/what-are-germanys-new-coronavirus-social-distancing-rules/a-52881742(accessed on 11 August 2021).

- BBC News. Coronavirus: Germany slowly eases lockdown measures. BBC News, 15 April 2020. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-52299358(accessed on 23 December 2020).

- Walsh, A.; Douglas, E. Coronavirus: Germany to impose one-month partial lockdown. Deutsche Welle, 28 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- BBC News. Covid-19: Germany introduces new restrictions amid rise in cases. BBC News, 16 December 2020. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-55324422(accessed on 23 December 2020).

- Sonnenberg, A.-K. Sorgen über Weihnachts- und Silvesterpläne im Corona-Jahr sind Groß. Available online: https://yougov.de/news/2020/11/12/sorgen-uber-weihnachts-und-silvesterplane-im-coron/ (accessed on 23 December 2020).

- Arnold, A.; Obier, C. Machbarkeitsstudie zur Durchführung der Weihnachtsmärkte in Zeiten der Corona-Pandemie; Projekt GmbH: Hamburg/München, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Nöstlinger, N.; Gonzalez, C.; Posaner, J. Germany’s Christmas markets threatened by coronavirus. Politico, 30 October 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hawley, S. Germans Flocked to the Shops to Get Their Christmas Shopping Done. Now It’s Forced Them into Lockdown for the Holiday. Available online: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-12-16/germans-face-a-tough-christmas-with-covid-19-restrictions/12986132 (accessed on 23 December 2020).

- Eddy, M. ‘I just miss all of that’: Germany’s historical Christmas markets are quiet this year. The Independent, 16 December 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Eddy, M. An Unwelcome Silent Night: Germany without Christmas Markets. New York Times, 10 December 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Arab News. German Xmas markets find ways around virus. Arab News, 30 November 2020. [Google Scholar]

- ZDF. Corona-Auflagen. Glühwein to Go Spaltet Die Republik. Available online: https://www.zdf.de/nachrichten/panorama/streit-gluehwein-to-go-100.html (accessed on 23 December 2020).

- Welt. In Berlin spricht mancher schon vom „Glühwein-Strich“. Die Welt, 8 December 2020. [Google Scholar]

- ABC News. Germany ramps up national coronavirus lockdown ahead of Christmas. ABC News, 14 December 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Staudenmaier, R. COVID-19: Mulled wine stands spark controversy in Cologne. Deutsche Welle, 6 December 2020. [Google Scholar]

- ZDF. Adventszeit ohne Weihnachtsmärkte. In ZDF Heute; Zweites Deutsches Fernsehen: Mainz, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Guboff, M.; Hlacer, E. Weihnachten 2020. Drive-In-Weihnachtsmarkt: “Wunderland Kalkar” darf trotz harten Lockdowns weiter öffnen. Westfälischer Anzeiger, 14 December 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Siebnich, H. Drive-In-Weihnachtsmarkt in Rastatt ist zu Ende: Kommt die Rückkehr zu Ostern? Badische Neueste Nachrichten, 29 December 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kotsev, M. Gebrannte Mandeln und Bratwurst durchs Autofenster. Der Tagespeigel, 19 December 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Käthe Wohlfahrt. Christmas Markets. Available online: https://www.kaethe-wohlfahrt.com/en/home/ (accessed on 20 December 2020).

- Dregeno. Die Weihnachtsmacher. Virtueller Markt der Manufakturen. Available online: https://www.dregeno.de/weihnachtsmarkt/ (accessed on 23 December 2020).

- Dresden On-line Shop. Virtueller Weihnachtsmarkt Dresden 2020. Available online: https://web.archive.org/web/20201203002149/https://www.dresden-onlineshop.de/Weihnachten (accessed on 1 July 2021).

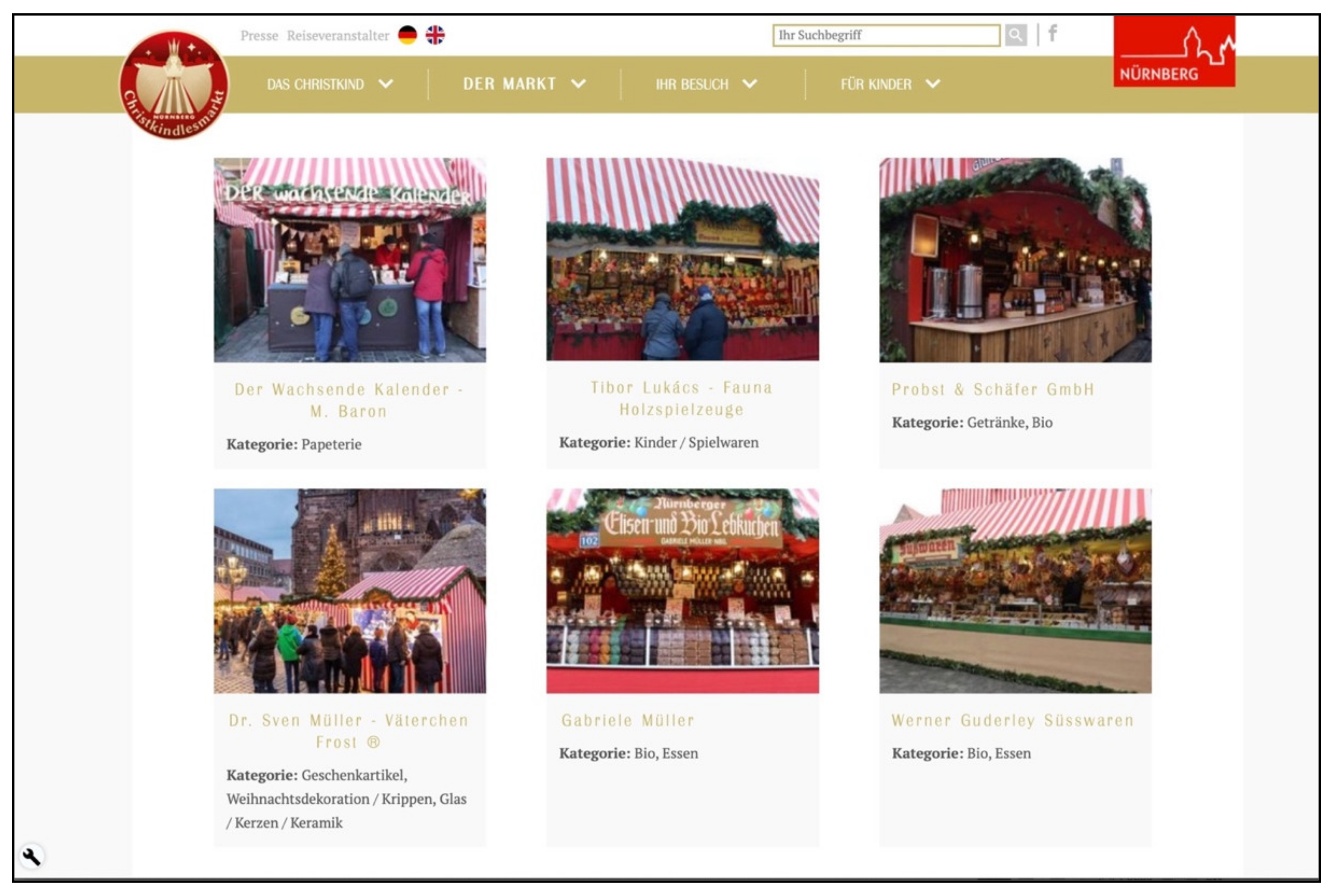

- Nürnberg Christkindlmarkt. Digitaler Christkindlesmarkt. Available online: https://www.christkindlesmarkt.de/digitaler-christkindlesmarkt-1.10614798 (accessed on 23 December 2020).

- KulturDigital. Making-of 3D-Weihnachtsmarkt DREGENO Seiffen. 2020. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Q85wu7EwAaY (accessed on 23 December 2020).

- Dietel, A. Seiffen im Erzgebirge. Virtueller Weihnachtsmarkt mit Budenzauber und Abendstimmung; RTL: Cologne, Germany, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Günther, S. Per Klick auf den Weihnachtsmarkt. Wochenendspiegel, 2 November 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kürvers, J. Wachstumschancen eines Virtuellen Weihnachtsmarkts. Interview mit Juliane Kröner, Geschäftsführerin der Dregeno Seiffen eG (Kurort Seiffen/Erzgebirge, Sachsen). Available online: https://dialog-unternehmen-wachsen.de/dialog/de/journal/52186/post/65/title/wachstumschancen+eines+virtuellen+weihnachtsmarkts (accessed on 1 July 2021).

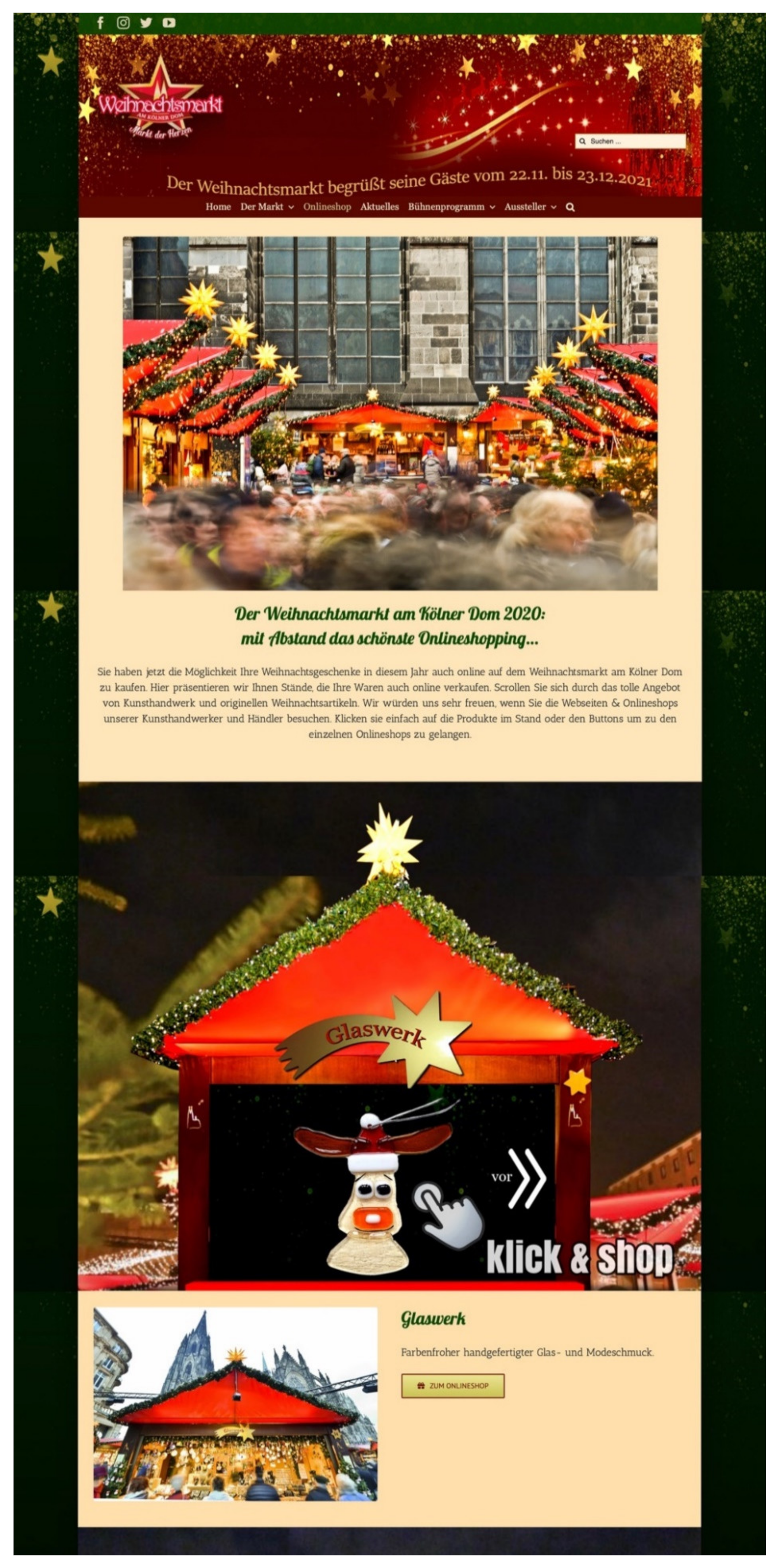

- Kölner Weihnachtsgesellschaft. Weihnachtsmarkt am Kölner Dom. Available online: http://www.koelnerweihnachtsmarkt.com/de/weihnachtsshopping-online/ (accessed on 1 July 2021).

- Kirchhoff, A. Christmas shine despite the coronavirus: Germany’s cities are festively lit. Deutsche Welle, 27 November 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Vecco, M. A definition of cultural heritage: From the tangible to the intangible. J. Cult. Herit. 2010, 11, 321–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreps, C.F. Indigenous Curation, Museums, and Intangible Cultural Heritage. In Intangible Heritage; Routledge: Milton Park, UK, 2009; pp. 193–208. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS Australia. The Burra Charter: The Australia ICOMOS Charter for Places of Cultural Significance 2013; Australia ICOMOS Inc. International Council of Monuments and Sites: Burwood, Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Kreps, C.F. Liberating Culture: Cross-Cultural Perspectives on Museums, Curation, and Heritage Preservation; Psychology Press: Road Hove, UK, 2003; Volume 7. [Google Scholar]

- Spennemann, D.H.R. Futurist rhetoric in U.S. historic preservation: A review of current practice. Int. Rev. Public Nonprofit Mark. 2007, 4, 91–99. [Google Scholar]

- Spennemann, D.H.R. The Futurist Stance of Historical Societies: An analysis of positioning statements. Int. J. Arts Manag. 2007, 9, 4–15. [Google Scholar]

- Spennemann, D.H.R. Beyond “Preserving the Past for the Future”: Contemporary Relevance and Historic Preservation. CRM J. Herit. Steward. 2011, 8, 7–22. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Basic Texts of the 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage’ for Its Protection and Promotion; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. Intangible Heritage Domains in the 2003 Convention. Available online: http://www.unesco.org/culture/ich/en/1com (accessed on 4 January 2017).

- Kasten, E.; de Graaf, T. Sustaining Indigenous Knowledge: Learning Tools and Community Initiatives for Preserving Endangered Languages and Local Cultural Heritage; BoD–Books on Demand: Nordeestedt, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Treloyn, S.; Googninda, C.R.; Nulgit, S. Repatriation of Song Materials to Support Intergenerational Transmission of Knowledge about Language in the Kimberley Region of Northwest Australia. In Endangered Languages Beyond Boundaries Publisher; Norris, M.J., Ed.; Foundation for Endangered Languages: Tirana, Albania, 2013; pp. 18–24. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Shafi, M.; Song, X.; Yang, R. Preservation of cultural heritage embodied in traditional crafts in the developing countries. A case study of Pakistani handicraft industry. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mallik, A.; Chaudhury, S.; Ghosh, H. Nrityakosha: Preserving the intangible heritage of indian classical dance. J. Comput. Cult. Herit. 2011, 4, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, K. Music as Intangible Cultural Heritage: Policy, Ideology, and Practice in the Preservation of East Asian Traditions; Routledge: Milton Park, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, M. The Heritage of Sound in the Built Environment: An Exploration; Charles Sturt University: Albury, Australia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Naguib, S.A. Engaged Ephemeral Art: Street Art and the Egyptian Spring. Transcult. Stud. 2017, 2, 53–88. [Google Scholar]

- Spennemann, D.H.R. COVID-19 on the ground: Heritage sites of a pandemic. Heritage 2021, 3, 2140–2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maffei, M.C. Culinary Traditions as Cultural Intangible Heritage and Expressions of Cultural Diversity. In Cultural Heritage, Cultural Rights, Cultural Diversity; Brill Nijhoff: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 223–249. [Google Scholar]

- Sammells, C.A. Haute Traditional Cuisines: How UNESCO’s List of Intangible Heritage Links the Cosmopolitan to the Local. In Edible Identities: Food as Cultural Heritage; Routledge: Milton Park, UK, 2016; pp. 141–158. [Google Scholar]

- Cang, V. Japan’s Washoku as Intangible Heritage: The Role of National Food Traditions in UNESCO’s Cultural Heritage Scheme. Int. J. Cult. Prop. 2018, 25, 491–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, K.A.; Műller, L. Intangible Heritage and Community Identity in Post-Apartheid South Africa. Mus. Int. 2010, 62, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, M.V. Intangible heritage tourism and identity. Tour. Manag. 2008, 29, 807–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BBC News. Tokyo Olympics: Games will go ahead ‘with or without Covid’, says IOC VP. BBC News, 7 September 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Corsini, A.; Bisciotti, G.N.; Eirale, C.; Volpi, P. Football Cannot Restart Soon during the COVID-19 Emergency! A Critical Perspective from the Italian Experience and a Call for Action; BMJ Publishing Group Ltd.; British Association of Sport and Exercise Medicine: London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, N. Falls Festival takes a raincheck as COVID-19 cancels the party. The Sydney Morning Herald, 26 August 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal, V.; Sunitha, B. COVID-19: Current pandemic and its societal impact. Int. J. Adv. Sci. Technol. 2020, 29, 432–439. [Google Scholar]

- Blake, E. ‘Our income vanished’: Australia’s galleries and museums buckle in Covid-19 storm. The Guardian, 7 May 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, M.; Spennemann, D.H.R. Anthropause on audio: The effects of COVID-19 pandemic on church bell ringing in New South Wales (Australia). J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2020, 148, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, M.; Spennemann, D.H.R. Responses to government-imposed restrictions: The sound of Australia’s church bells one year after the onset of COVID-19. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2021, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spennemann, D.H.R.; Parker, M. Hitting the ‘Pause’ Button: What does COVID tell us about the future of heritage sounds? Noise Mapp. 2020, 7, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicola, M.; Alsafi, Z.; Sohrabi, C.; Kerwan, A.; Al-Jabir, A.; Iosifidis, C.; Agha, M.; Agha, R. The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): A review. Int. J. Surg. 2020, 78, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holmes, E.A.; O’Connor, R.C.; Perry, V.H.; Tracey, I.; Wessely, S.; Arseneault, L.; Ballard, C.; Christensen, H.; Silver, R.C.; Everall, I. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: A call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 547–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spennemann, D.H.R. Your solution, their problem. Their solution, your problem: The Gordian Knot of Cultural Heritage Planning and Management at the Local Government Level. disP 2006, 42, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnston, C. What is Social Value? A Discussion Paper; Australian Government Publishing Service: Canberra, Australia, 1992.

- Canning, S.; Spennemann, D.H.R. Contested Space: Social Value and the Assessment of Cultural Significance in New South Wales, Australia. In Heritage Landscapes: Understanding Place and Communities. Proceedings of the Lismore Conference; Cotter, M.M., Boyd, W.E., Gardiner, J.E., Eds.; Southern Cross University Press: Lismore, Australia, 2001; pp. 457–468. [Google Scholar]

- Graham-McLay, C. ‘A beautiful day’: New Zealand handshakes and hugs its way back to pre-Covid-19 life. The Guardian, 9 June 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cockburn, P. Crowds swarm to shopping centres as coronavirus restrictions begin to ease, causing alarm over lack of social distancing. ABC News, 9 May 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Assunção, M. Londoners swarm pubs for one last, pre-lockdown drink ‘to enjoy a bit of freedom before it’s over for months’. New York Daily News, 5 November 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Nussio, E. Attitudinal and Emotional Consequences of Islamist Terrorism. Evidence from the Berlin Attack. Political Psychol. 2020, 41, 1151–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer-Preßler, D.; Schwemmer, C.; Fischbach, K. Collective sense-making in times of crisis: Connecting terror management theory with Twitter user reactions to the Berlin terrorist attack. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 100, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brusch, M.; Stüber, E. Developments and Classifications of Online Shopping Behavior in Germany. Int. J. Cyber Soc. Educ. 2014, 7, 147–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, R.; Deitz, G.; Royne, M.B.; Hansen, J.D.; Grünhagen, M.; Witte, C. Cross-cultural examination of online shopping behavior: A comparison of Norway, Germany, and the United States. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsche Welle. Climate change: Majority of Germans support ditching Christmas lights. Deutsche Welle, 8 December 2019. [Google Scholar]

- The Sounds of Life. Walking in Germany Christmas Market | Spandauer Weihnachtsmarkt | 4K. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Fg1c2h3a59A&t=686s (accessed on 26 December 2020).

- Goodstuff. Christmas Market in Berlin 2020—Tasting Street Foods. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eVfqJXxSXkY&t=378s (accessed on 26 December 2020).

- UNESCO. Gióng Festival of Phù Ðông and Sóc Temples. Available online: https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/ging-festival-of-ph-ng-and-sc-temples-00443 (accessed on 21 July 2021).

- UNESCO. Schemenlaufen, The Carnival of Imst, Austria. Available online: https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/schemenlaufen-the-carnival-of-imst-austria-00726 (accessed on 21 July 2021).

- Bhandari, S. Holi: Gender Dynamics and the Festival of Colors in Northern India. Berkeley J. Sociol. 2017, 60, 18–28. [Google Scholar]

- Perry, B.; Ager, L.; Sitas, R. Cultural heritage entanglements: Festivals as integrative sites for sustainable urban development. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2020, 26, 603–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Del Barrio, M.J.; Devesa, M.; Herrero, L.C. Evaluating intangible cultural heritage: The case of cultural festivals. Citycult. Soc. 2012, 3, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palma, M.L.; Palma, L.; Aguado, L.F. Determinants of cultural and popular celebration attendance: The case study of Seville Spring Fiestas. J. Cult. Econ. 2013, 37, 87–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, A.-S. Showing making: On visual documentation and creative practice. J. Mod. Craft 2012, 5, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- ISO. Acoustics—Soundscape. Part 2 Data Collection and Reporting Requirements; International Standards Organsiation: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; Volume ISO TS12913–2. [Google Scholar]

- Bembibre, C.; Strlič, M. Smell of heritage: A framework for the identification, analysis and archival of historic odours. Herit. Sci. 2017, 5, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Davis, L.; Thys-Şenocak, L. Heritage and scent: Research and exhibition of Istanbul’s changing smellscapes. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2017, 23, 723–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimkulrat, N. The role of documentation in practice-led research. J. Res. Pract. 2007, 3, M6. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, H.T.; Hachimura, K.; Yano, K.; Tanaka, S.; Furukawa, K.; Nishiura, T.; Tsutida, M.; Choi, W.; Wakita, W. Multimodal digital archiving and reproduction of the world cultural heritage” Gion Festival in Kyoto”. In Proceedings of the 9th ACM SIGGRAPH Conference on Virtual-Reality Continuum and Its Applications in Industry, Seoul, Korea, 12–13 December 2010; pp. 21–28. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Parker, M.; Spennemann, D.H.R. Stille Nacht: COVID and the Ghost of Christmas 2020. Heritage 2021, 4, 3081-3097. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage4040172

Parker M, Spennemann DHR. Stille Nacht: COVID and the Ghost of Christmas 2020. Heritage. 2021; 4(4):3081-3097. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage4040172

Chicago/Turabian StyleParker, Murray, and Dirk H. R. Spennemann. 2021. "Stille Nacht: COVID and the Ghost of Christmas 2020" Heritage 4, no. 4: 3081-3097. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage4040172

APA StyleParker, M., & Spennemann, D. H. R. (2021). Stille Nacht: COVID and the Ghost of Christmas 2020. Heritage, 4(4), 3081-3097. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage4040172