Sustainable Management of Underwater Cultural Heritage: The Route from Discovery to Engagement—Open Issues in the Mediterranean

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- The narrative of many of the Mediterranean WW I and especially WW II battlefields or naval tragedies is not well known today by the general public.

- The exact number and location of sunken WW I and II vessels in the Mediterranean is not yet fully known.

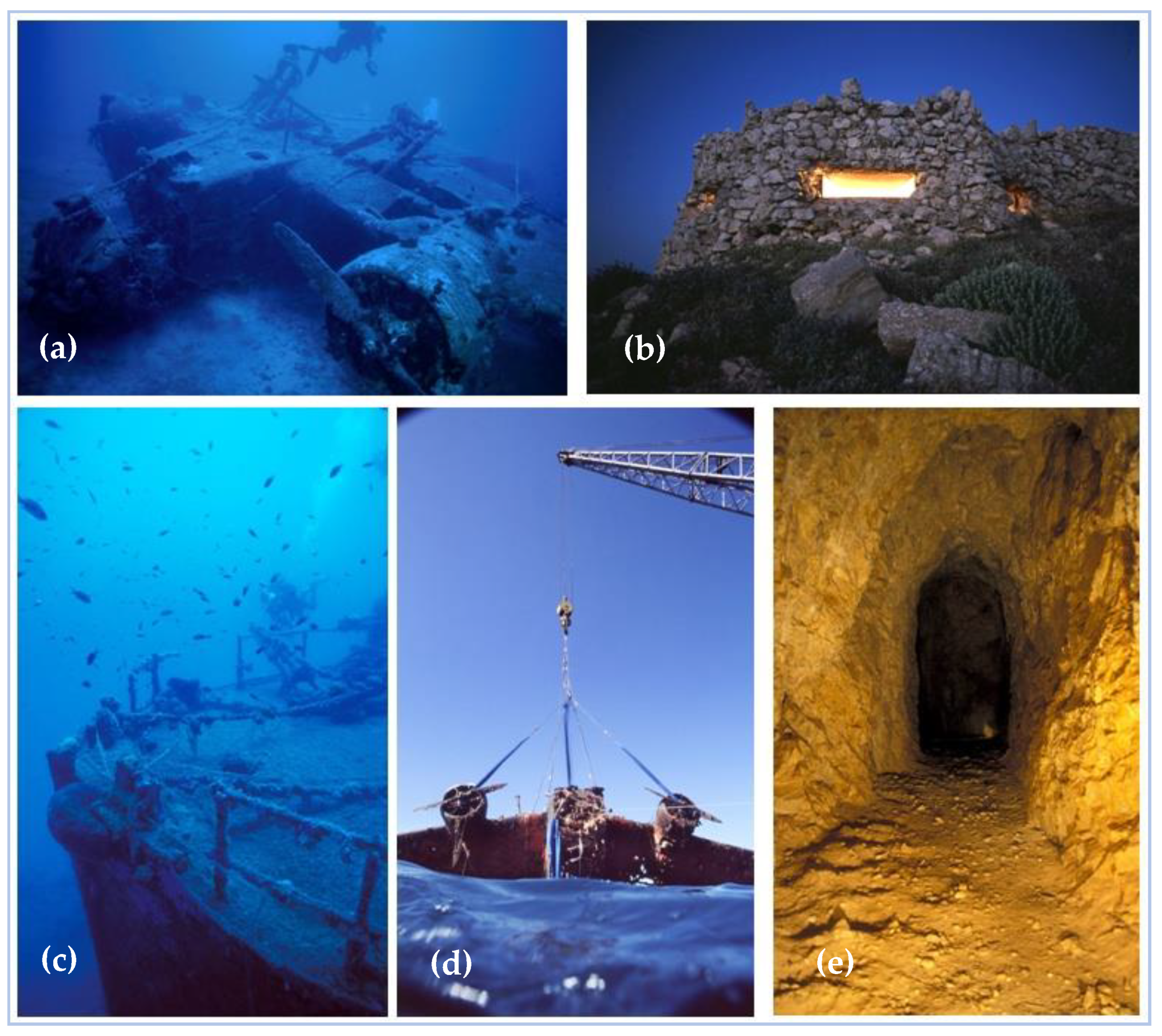

- These vessels, as evidence of WW I and II historical events, are in many cases already lost. For example, many of WW I and especially WW II UCH were or still are salvaged for scrap metal [16,20]. An example of this is S/S Oria, which sunk off the island of Patroklos near Attica Region [16]. Those that usually remain untouched are sunken vessels in deep waters or submerged aircraft.

- Archaeological research in the Mediterranean is somehow lagging behind with respect to UCH and is mainly focused on terrestrial and coastal CH, given the large number of UNESCO World Heritage Sites located in this area that are mostly found at a very short distance from the coastline (e.g., in Greece, Portugal, Italy, Malta, Tunisia, Egypt, Cyprus).

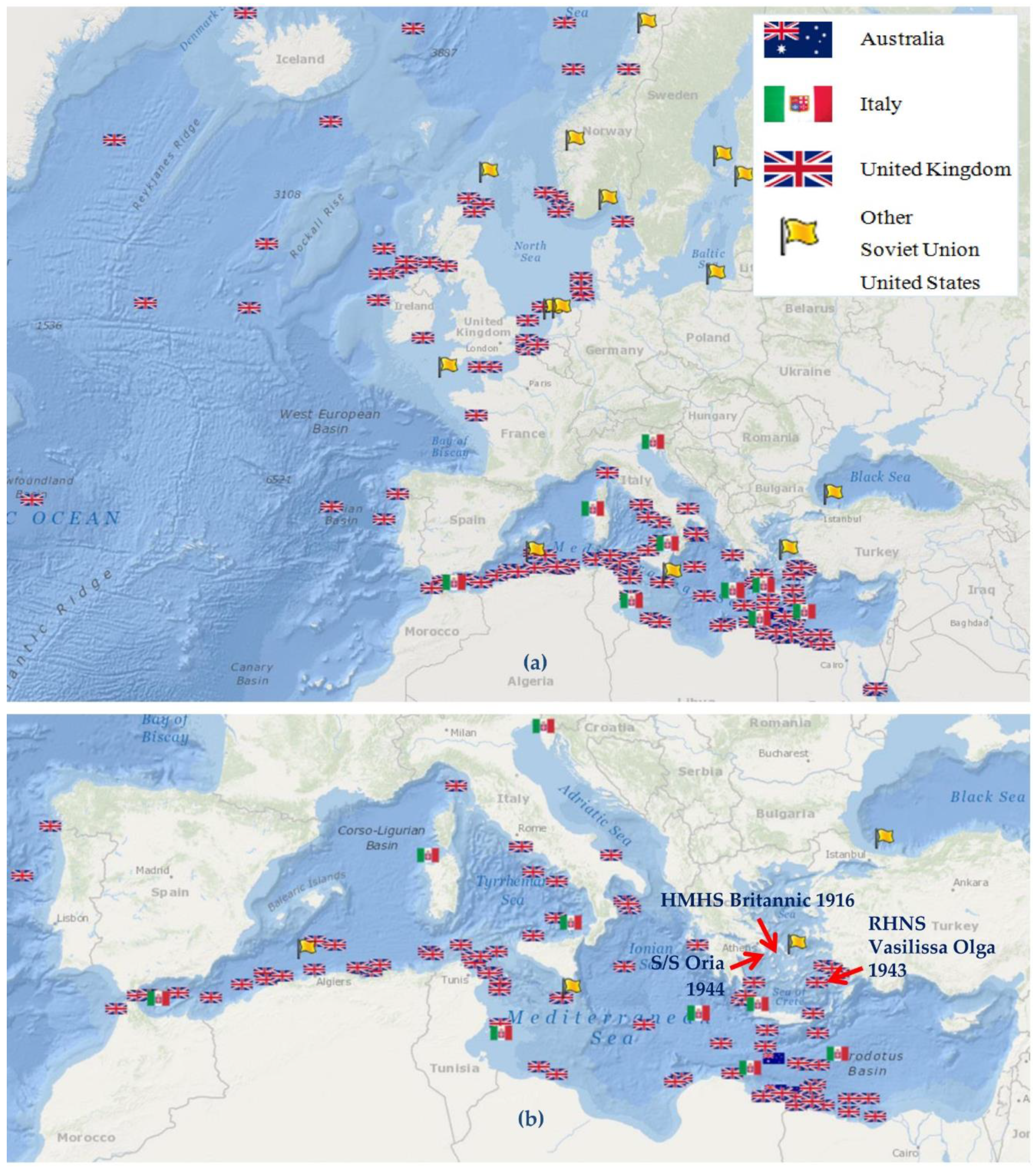

- Despite the historical value of a great number of Mediterranean sites and the abundance of their remnants (see Figure 1 below), a lack of a systematic effort to map and document these sites as WW I and II battlefield tourism destinations is noticed, which could produce value for their local communities. Such efforts though have been carried out by other relevant sites in northern Europe or elsewhere in the World (see [21]). Some well-known battlefield tourism sites are for example: Normandy France, where the D-Day Landing beaches are highly popular destinations for battlefield tourism, with the 70th anniversary in 2014 drawing some of the greatest number in visitors [22]; Solomon Islands, Oceania, shifting geography of war to layers of memory in the form of plaques, monuments, and memorials as significant reminders of the events that once made the Solomon Islands the center of world attention [21]; Chuuk state, Federated States of Micronesia, being Japan’s heavily fortified main base in the South Pacific Theater and a currently worldwide scuba diving paradise due to its numerous, virtually intact sunken ships, the “Ghost Fleet of Truk Lagoon” [23].

- Full protection of UCH has not been achieved, as UNESCO Convention (not signed by all relevant countries) protects only WW I UCH (older than 100 years), while leaving aside WW II UCH (submerged less than 100 years).

- High vulnerability, as opposed to other types of UCH, due to its construction materials and the high salinity of the Mediterranean Sea, expected to further deteriorate due to climate change impacts;

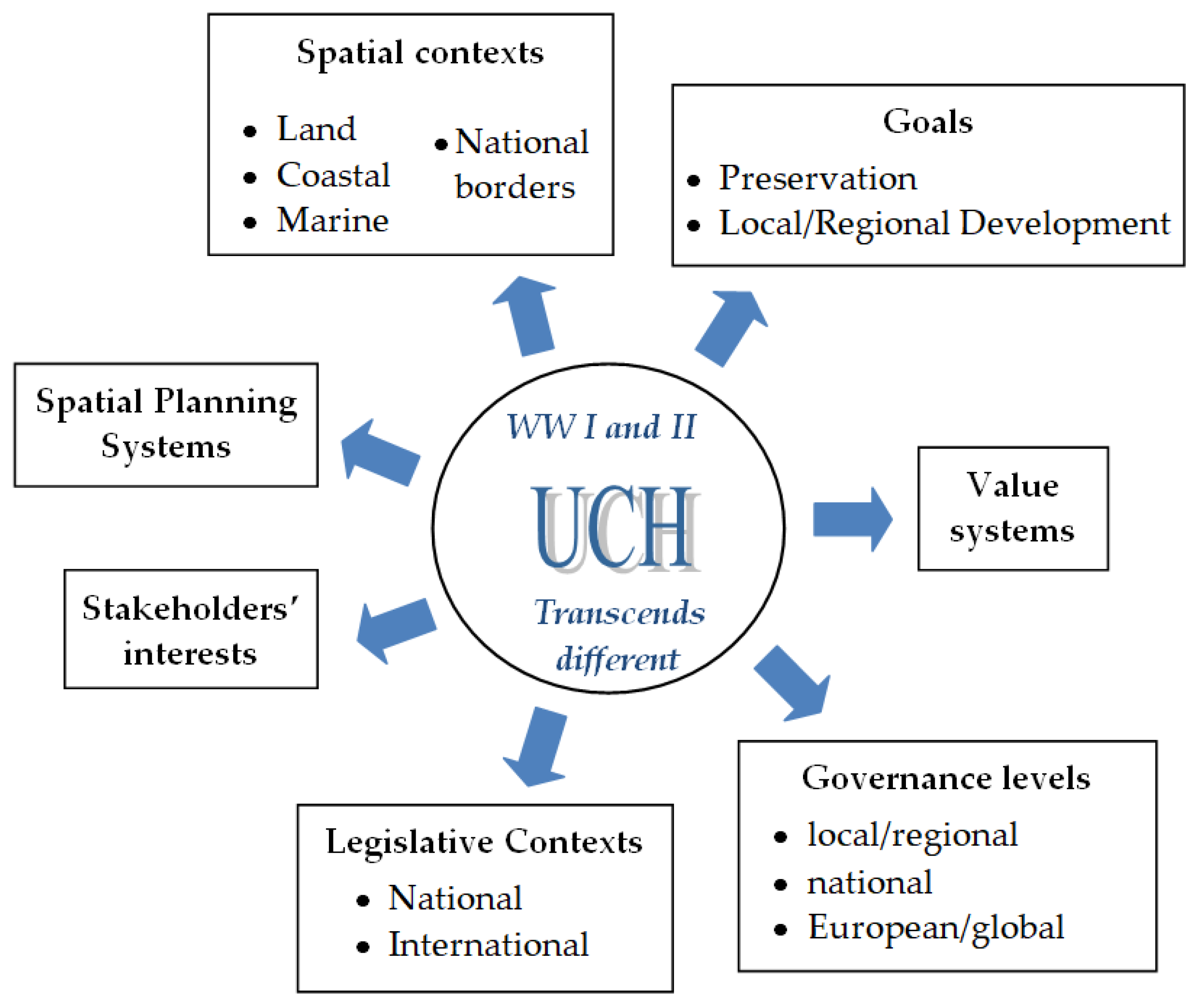

- Diverse interests/stakes involved and related inherent values ranging from local to global level, as well as the lack of common understanding and governance of UCH;

- Lack of adequate knowledge with regard to the UCH position, condition, safety, impact on the marine environment, etc.;

- Impacts related to anthropogenic factors (e.g., transportation, tourism, fishing), placing WW I and II UCH at risk.

- Rather fragmentarily exploited (e.g., diving activities), largely ignoring its social, ethical, symbolic, historical, cultural and environmental values;

- Lacking an integrated management approach of tangible and intangible UCH and related terrestrial CH aspects (wherever relevant) for understanding the full narrative behind them and transmitting lessons learnt towards the European community;

- Underestimated with regards to its power for generating growth by shifting, under certain preconditions, war scenes/remnants to economic opportunity, e.g., coastal/maritime cultural tourism, Cultural Creative Industry (CCI) productions related to WW I and II to name a few.

2. WW I and II Underwater Cultural Heritage in the Mediterranean

2.1. WW I UCH Context

2.2. WW II UCH Context

3. Current Considerations for Protection and Preservation of WW I and II UCH

3.1. Current Legislative Protection Framework

- 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) [40]: Defines the rights and responsibilities of nations with respect to their use of the world’s oceans. Its numerous provisions delineate sea areas or maritime zones as well as the rights and uses of these zones by coastal states and foreign vessels within these zones. The convention provides definitions of a warship as well as the sovereign immunity of warships on the high seas, and it is used as a reference point for the UNESCO 2001 Convention (see below). It also sets out the rights and jurisdictions of states in the sea, which indirectly affects the potential for implementing states’ UCH protection policies, in alignment with each single state’s legislative context.

- 1992 European Convention on the Protection of the Archaeological Heritage (Valetta or Malta Convention) [41]: Aims to protect archaeological heritage as a source of European common memory and a resource for historical and scientific study. Particularly, it focuses on: the maximum retention of items of archaeological value in the seabed (in-situ), the obligation to report archaeological finds, the consideration of archaeological interests in spatial planning as well as the guarantee that environmental impact statements and the ensuing decisions take sites of archaeological interest and their context into account.

- 1996 Charter on the Protection and Management of Underwater Cultural Heritage (ICOMOS Charter 1996) [42]: A supplement of the ICOMOS Protection and Management of Archaeological Heritage of 1990 [43]. It outlines the fundamental principles for UCH conservation, while it elaborates, among others, on issues of funding; research objectives; team members’ qualifications; investigation, documentation and material conservation; management and maintenance of the UCH site; and dissemination of information about the UCH. It also encourages international cooperation and exchange of specialists in order for UCH research to be facilitated, while fostering public awareness with respect to the importance of UCH and the role of the public in its protection and investigation.

- 2001 UNESCO Convention on the Protection of Underwater Cultural Heritage [3]: Constitutes an international framework for the protection of UCH older than 100 years. It provides a definition for UCH, such as ‘State vessels’, which are warships, aircraft and other non-commercial vessels that are given cultural importance. It also ensures the rights of flag states to excavate and preserve these vessels beyond their territorial waters. More specifically, in Article 2, it sets out the rights of State vessels to be consistent with state practice and international law, including the UNCLOS, and claims that nothing in the convention shall be interpreted as modifying the rules of international law and state practice pertaining to sovereign immunities, nor any state’s rights with respect to its state vessels and aircraft. The convention went beyond UNCLOS to set out the rights and duties of the coastal state and/or flag nation according to the location of the sunken UCH in the defined maritime zone. Furthermore, it uses the rules of the 1996 ICOMOS charter on the handling and management of UCH [44].

3.2. Effectively Managing WW I and II UCH in the Mediterranean—Challenges and Opportunities Ahead

3.3. Successful WW I and II UCH Sustainable Management Practices in the Pacific

4. Open Issues for WW I and II UCH Preservation and Sustainable Management in the Mediterranean

- comprehending and preserving the ‘big image’, i.e., the historical memory of world’s past failures or progress through the social, economic, and technological information UCH conveys [47], and imparting this image to future generations; and

- exploiting UCH potential to leverage local development in small islands and/or island states as well as peripheral coastal regions by drawing qualitative, long lasting, blue growth-driven, heritage-led development pathways.

4.1. From a “Silo” to an Integrated WW I and II UCH Management Approach

- (i)

- UCH management dimensions into various contexts (e.g., spatial, environmental, economic, societal), thus constituting a step towards a multi- and inter-disciplinary interaction and cooperation among a variety of disciplines. This will bring on board diversified qualities and knowledge stock that are necessary for ensuring both protection/preservation and sustainable and resilient exploitation of WW I and II UCH.

- (ii)

- Experiential knowledge and stakes of the various interested parties into scientific knowledge and decision-making processes, in an effort to create value and effectively protect UCH (good example of public engagement is the one of Australia, as presented by Viduka (2017) [8]).

- Places UCH in its wider environment, exploring positive and negative interactions of UCH with this environment. This implies the exploration and documentation of this interaction by means of an Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA), setting the ground for identifying risk or opportunity emanating from UCH, i.e., UCH as a source of pollution [76,77] or an artificial reef [78,79].

- Grasps UCH as a valuable resource, a production factor, which can create positive impulses to local economies by opening up business opportunities for new cultural experience-based products and local income creation [7,80]. This view is further enhanced by the EU blue growth strategy [81,82], fertilizing the ground for the attraction of investments in maritime activities. Sustainable exploitation of UCH has definitely the potential to be part of a vibrant blue growth strategy of EU, provided that the carrying capacity of the seascape is consciously addressed. Thus, UCH sites are potential places for sustainable experience-based tourism development, playing the role of e.g., underwater museums of the European history, but also sites of recreation and leisure in properly managed underwater parks and diving trails. These can render these historical maritime landscapes and their content visible and graspable to a larger audience.

- Engages society in the creation of a UCH narrative that embeds empirical knowledge and has multiple benefits with respect to local identity building, awareness raising on the value of UCH, establishment of community bonds and promotion of social cohesion and people’s sense of belonging [42,83,84]. WW I and II UCH sites incorporate significant evidence of past military and fatal events and disasters that are closely related to their wider land neighborhood and are strongly linked to historical trajectory and socio-cultural aspects of local communities. In this respect, these are perceived as integral parts of local identity and incorporate meanings and values for these communities. Shifting to an integrated UCH management approach implies additionally the establishment of new trails for spreading these values to society and economy in an environmentally and culturally responsible way, safeguarding thus UCH and paving the way to heritage-led LSD [6].In contrast to the view of Hannahs (2003) [85], stating that public access to archaeological sites is both incompatible with and contradictory to the goal of their preservation, many researchers share the opinion that when UCH is discovered, it should be properly managed, taking into consideration the needs of science and of the public, within the context of the prevailing legislative framework. Scott-Ireton (2007) [86] takes it a step further by designating community involvement as a critical factor for the successful management of submerged archaeological sites; but also a key driver and an effective means for monitoring shipwrecks in the community’s own backyards, providing more effective results than legislation and threat of arrest per se. Training people to respect UCH and teaching them to perceive this heritage as a historical asset determining their identity, but also a resource that can steer new economic opportunities, and a catalyst for social cohesion and environmental sustainability, can strengthen public awareness and render local communities the safeguards of this heritage to the benefit of sustainable local development.

4.2. Dealing with WW I and II UCH Management as a ”Wicked” Planning Problem

- Purely technical: Archaeological and heritage management approaches for UCH protection/preservation.

- Environmental: Role of UCH as either a pollution source or a beneficial artificial reef.

- Social and ethical: UCH linkages to diversifying localities’ values and narratives or human losses of varying nationalities.

- Technological: Tools and technologies addressing UCH research issues.

- Jurisdictional: National and international laws and conventions dedicated to UCH protection.

- neighboring coastal part, since a number of wrecks are potentially located close to the coast and their narrative are strongly linked to the coastal part as well, such as the case of Southern France, and “Operation Dragoon” in WW II or the case of Leros Island, Greece and ‘The Battle of Leros’ in WW II; and

- neighboring terrestrial part of the area through e.g., the involvement of local population in the military events or the location of military installations/operations in the land part, such as the case of Leros Island, Greece in WW II [7].

- Legislative status, e.g., abandoned/protected according to maritime laws;

- Vulnerability or risk to loss;

- Polluting source or artificial reef;

- Current condition of UCH;

- Role as historical prototype of ships and related technology that survive in a submerged museum-like status;

- War grave or memorial;

- Political, economic, cultural/historical values UCH carries;

- Spatial attributes, e.g., location, sea depth, visibility and temperature of waters;

- Social value, i.e., sense of identity based on various perspectives (local, coastal state and flag nation perspectives);

- Symbolic value—conveyor of meaning.

4.3. UCH Management Concerns in the Mediterranean Region

- The marine environment in the Mediterranean is largely exposed to global challenges, such as the climate change [100,101]. In fact, as various studies demonstrate, the Mediterranean region constitutes a hot spot with respect to, among others, climate change impacts [11,52,102], with these impacts creating a natural environment that places UCH stability at risk. The climate change strategy of EU and its member-states is considered as a positive step in coping with these risks, provided that UCH provisions are also incorporated in this strategy (ies).

- A debt crisis is unfolding in the Mediterranean during the last decade, implying that WW I and II UCH protection/preservation has to be carried out in an era of limited financial resources. In such a context, and taking into consideration the vast number of WW I and II UCH sunk in this area, valuing the importance of this UCH by developing a value/significance typology is quite critical for supporting more informed decision-making with respect to UCH protection/preservation priorities and rational use of resources.Within this stagnating economic environment though, there is an increasing stakeholders’ interest for investing in a range of maritime sectors –the comparative advantage of the Mediterranean region– being the result of the rising new wave, i.e., the ‘Blue economy’, and the European policy initiatives (Blue Growth Strategy) towards the sustainable management of marine resources.This brings to the forefront new developmental opportunities in, among others, the tourism sector in coastal and insular areas in the Mediterranean [103]. Indeed, sustainable and resilient exploitation of WW I and II UCH in this region can strongly be linked to alternative tourism, e.g., dark/battlefield, cultural or diving tourism. Diving recreation activities, for example, present a promising activity at the global level, as noticed by the Recreation Scuba Training Council Europe—RSTC and evidenced by certification statistics provided by the Professional Association of Diving Instructors, i.e., the world’s leading scuba diver training organization [104,105].Furthermore, the linkage of UCH to alternative tourism is currently being met in many places around the world and is rated high in the policy agenda of urban and regional destinations [106] (see also experience from battlefield tourism destinations in the Pacific). Additionally, this is justified by the endurance of culture and tourism in times of recession [107], a current state in many Mediterranean countries nowadays; and their multiplier effects for local economies as a whole.

- UCH exploitation is in alignment with the current trends and related policies in promoting the culture–tourism complex (e.g., Regional Innovation Strategy for Smart Specialization—RIS3) [108], in order for sustainable pathways through experience-based and of low ecological footprint tourism products to be established; while supporting the exchange of new, meaningful and authentic tourism experiences [80]. The role of UCH in providing this type of experience was noticed early enough by ICOMOS (1996) [42], stating that if UCH is sensitively managed, it can play a positive role in the promotion of recreation and tourism.

- The technological environment is also rapidly evolving and is marked by progress conducted in tools and technologies for UCH identification, monitoring, visualization etc. that facilitate UCH research as well as communication of UCH content to a larger audience (see Section 3.2).

- Developments in the legislative context that relate to the management of marine space are in progress in the Mediterranean countries, coupled with relevant planning tools (Marine Spatial Planning—MSP and Integrated Coastal Zone Management—ICZM). These prepare the ground for dealing with emerging conflicts and promoting synergies’ creation among various stakes in the marine environment; while setting up an effective spatial delineation of maritime uses to the benefit of UCH protection. However, a range of barriers appear in such a context as well, reflecting the different MSP systems of each single state involved; the stage of maturity of MSP in the various coastal states surrounding the Mediterranean Sea; the way UCH is handled within MSP studies; the provision of designated areas for UCH protection in each MSP system; and the national legislative regime as to the protection of UCH, to name a few.

- Active contested and dissonance heritage issues related to UCH are of key importance, especially for South Eastern Europe (Balkans) and Eastern Mediterranean (Greece, Turkey, Middle East). This is justified by the multicultural background of Mediterranean region (Muslims, Christians, and Jews), but also its intense historical profile depicted through numerous wars, occupations, political turnovers and social changes (e.g., colonialism, WW I and II, fascism, resistance, civil wars, communism, ethnic cleansing to name a few) [109,110].

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgements

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNESCO. Underwater Cultural Heritage from World War I. In Proceedings of the Scientific Conference on the Occasion of the Centenary of World War I, Bruges, Belgium, 26–27 June 2014; Guérin, U., da Silva, A.R., Simonds, L., Eds.; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Snyder, Κ. Clipperton Project Saving the Oceans, One Person at a Time. Available online: http://www.clippertonproject.com/oceans-have-more-historical-artifacts-than-all-museums-combined/ (accessed on 1 February 2019).

- UNESCO. The UNESCO Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage (CPUCH); UNESCO: Paris, France, 2001; pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Delgado, J.; Varmer, O. The Public Importance of World War I Shipwrecks: Why a State Should Care and the Challenges of Protection. In Proceedings of the Scientific Conference on the Occasion of the Centenary of World War I, Bruges, Belgium, 26–27 June 2014; Guérin, U., da Silva, A.R., Simonds, L., Eds.; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2015; pp. 105–116. [Google Scholar]

- Jameson, J.H.; Scott-Ireton, D.A. (Eds.) Out of the Blue; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Nutley, D.M. Look Outwards, Reach Inwards, Pass It On: The Three Tenures of Underwater Cultural Heritage Interpretation. In Out of the Blue; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2007; pp. 33–51. [Google Scholar]

- Koutsi, D.; Stratigea, A. Unburying Hidden Land and Maritime Cultural Potential of Small Islands in the Mediterranean for Tracking Heritage-Led Local Development Paths. Heritage 2019, 2, 938–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Viduka, A.J. Protection and Management of Australia’s Second World War Underwater Cultural Heritage. In Safeguarding Underwater Cultural Heritage in the Pacific; PUCHP, Ed.; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2017; pp. 77–92. [Google Scholar]

- Europeana 1914–1918. Available online: https://www.europeana.eu/portal/en/collections/world-war-I (accessed on 8 May 2019).

- Timmermans, D. UNESCO Education Initiative—Heritage for Dialogue and Reconciliation: Safeguarding Underwater Cultural Heritage from World War I. In The Underwater Cultural Heritage From World War I UNESCO the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization with the Support of Proceedings of the Scientific Conference on the Occasion of the Centenary of World War I; Guérin, U., da Silva, A.R., Simonds, L., Eds.; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2015; pp. 172–181. [Google Scholar]

- Stratigea, A.; Leka, A.; Nicolaides, C. Small and Medium-Sized Cities and Insular Communities in the Mediterranean: Coping with Sustainability Challenges in the Smart City Context; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 3–29. [Google Scholar]

- Porch, D. The Path to Victory: The Mediterranean Theater in World War II; Farrar, Straus and Giroux: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Garland, A.; McGraw, H. The United States Army in World War II: The Mediterranean Theatre of Operations: Sicily and the Surrender of Italy; Center of Military History United States Army: Washington, DC, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, M.B. Sea Transport and Supply—1914–1918. Available online: https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/sea_transport_and_supply (accessed on 7 February 2019).

- Mills, S. HMHS Britannic: The Last Titan; Shipping Books Press: Drayton, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Thoctarides, K.; Bilalis, A. Shipwrecks of the Greek Seas, Dive into Their History; Aikaterini Laskaridis Foundation: Peraias, Greece, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Mentogiannes, B. 52 Days 1943—The Queen Olga and the Battle of Leros: Underwater Filming and Research; Kastaniotes: Athens, Greece, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Zaloga, S.J. Operation Dragoon 1944, France’s Other D-Day; Osprey Publishing Ltd.: Oxford, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Tzur, Y. The Commander Yehuda Ben-Tzur Palyam & Aliya Bet Website. Available online: http://www.palyam.org/English/Hahapala/Teur_haflagot/Rafiah_en (accessed on 2 February 2019).

- Browne, K. “Ghost Battleships” of the Pacific: Metal Pirates, WWII Heritage, and Environmental Protection. J. Marit. Archaeol. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panakera, C. World War II and Tourism Development in Solomon Islands. In Battlefield Tourism; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 125–141. [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull, G. Remembering D-Day: Revealing the Hidden Wrecks under Normandy Waters. Available online: https://www.naval-technology.com/features/featureremembering-d-day-revealing-the-hidden-wrecks-under-normandy-waters-4143012/ (accessed on 1 February 2019).

- Browne, K.V. Trafficking in Pacific World War II Sunken Vessels the “Ghost Fleet” of Chuuk Lagoon, Micronesia. J. Law Soc. Sci. 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO. Safeguarding Underwater Cultural Heritage in the Pacific, Report on the Good Practice in the Protection and Management of World War II-Related Underwater Cultural Heritage; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Timmermans, D.; Guerin, U.; da Silva, A.R. (Eds.) Heritage for Peace and Reconciliation, Safeguarding the Underwater Cultural Heritage of the First World War; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Halpern, P.G. A Naval History of World War I; United States Naval Institute: Annapolis, MD, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Verlinden, V. The Demise of SMS SzentIstván. X-Ray Mag. 2018, 7–8. Available online: https://xray-mag.com/content/demise-sms-szent-istv%C3%A1n (accessed on 1 February 2019).

- Cibecchini, F.; Hulot, O. The Danton and U-95: Two Symbolic Wrecks to Illustrate and Promote the Heritage of the First World War. In Proceedings of the Scientific Conference on the Occasion of the Centenary of World War I, Bruges, Belgium, 26–27 June 2014; Guérin, U., da Silva, A.R., Simonds, L., Eds.; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2015; pp. 192–198. [Google Scholar]

- Kelkit, A.; Celik, S.; Eşbah, H. Ecotourism Potential of Gallipoli Peninsula Historical National Park. J. Coast. Res. 2010, 263, 562–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thys-Şenocak, L. Divided Spaces, Contested Pasts: The Heritage of the Gallipoli Peninsula; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Selcuk, K.; Taktak, O.; Karakas, S.; Atabay, M. Echoes from the Deep—Wrecks of the Dardanelles Campaign Gallipoli (Military History); VehbiKoc Foundation: Istanbul, Turkey; Ayhan Sahenk Foundation: Istanbul, Turkey, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod, I. Corrosion and Conservation Management of the Submarine HMAS AE2 (1915) in the Sea of Marmara, Turkey. Heritage 2019, 2, 868–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Veronico, N.A. Hidden Warships, Finding World War II’s Abandoned, Sunk, and Preserved Warships, 1st ed.; Zentih Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Dounis, C. Shipwrecks in the Greek Seas; 1900–1950 (Volume A); Finatec: Athens, Greece, 2000. (In Greek) [Google Scholar]

- WWII Shipwrecks in the Greek Seas. Available online: http://labtop.topo.auth.gr/wreckhistory/ww2witgs/ (accessed on 7 May 2019).

- Delaney, D.E. Churchill and the Mediterranean Strategy: December 1941 to January 1943. Def. Stud. 2002, 2, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chant, C. The Encyclopedia of Codenames of World War II (Routledge Revivals); Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- World War II Shipwrecks. GEBCO, IHO-IOC GEBCO, NGS, DeLorme, Esri. Available online: https://www.arcgis.com/home/webmap/viewer.html?webmap=14b4d42b21f64a2bb69fa1d2389fabdf (accessed on 9 January 2019).

- Geraga, M.; Katsou, E.; Christodoulou, D.; Iatrou, M.; Kordella, S.; Papatheodorou, G.; Mentogiannis, V.; Kouvas, K. Mapping Natural and Cultural Marine Heritage in Leros Island Greece. In Rapport du 40e Congres de la CIESM 40th; Ciesm, D.E.L.A., Ed.; CIESM: Marseille, France, 2013; Volume 40, p. 847. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Treaty Series. United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1982; pp. 397–576. [Google Scholar]

- Council of Europe. Chart of Signatures and Ratification of Treaty 143. In European Convention on the Protection of the Archaeological Heritage (Revised); Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 1992; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. Charter on the Protection and Management of Underwater Cultural Heritage (1996); ICOMOS: Paris, France, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- ICOMOS. ICOMOS Charter for the Protection and Management of the Archaeological Heritage (1990); ICOMOS: Paris, France, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Strati, A. Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage: From the Shortcomings of the UN Convention. In Unresolved Issues and New Challenges to the Law of the Sea Time before and Time after; Strati, A., Gavouneli, M., Kourtos, N., Eds.; Martinus Nijhoff Publishers: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Ehler, C.; Douvere, F. Marine Spatial Planning: A Step-by-Step Approach, IOC Manuals and Guides 53; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Papageorgiou, M. Aspects of Spatial Planning and Governance in Marine Environments. In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Environmental Science and Technology, Organized by Global Network on Environmental Science and Technology, Rhodes, Greece, 31 August–2 September 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Strati, A. The Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage: An Emerging Objective of the Contemporary Law of the Sea; Martinus Nijhoff Publishers: The Hague, The Netherlands, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Forrest, C. Culturally and Environmentally Sensitive Sunken Warships. Aust. N. Z. Marit. Law J. 2012, 26, 80–88. [Google Scholar]

- Alcaro, L.; Amato, E.; Cabioch, F.; Farchi, C.; Gouriou, V. DEEPP Project Development of European Guidelines for Potentially Polluting Shipwrecks. Deep Proj. 2007. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/echo/files/civil_protection/civil/marin/pdfdocs/deepppilotproject.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2019).

- Russell, M.A.; Murphy, L.E. USS Arizona Memorial; Dept. of Defense Legacy Resources Management Fund, and National Park Service System wide Archaeological Inventory Program, and USS Arizona Memorial: Sante Fe, NM, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod, I.D. In-Situ Corrosion Studies on Wrecked Aircraft of the Imperial Japanese Navy in Chuuk Lagoon, Federated States of Micronesia. Int. J. Naut. Archaeol. 2006, 35, 128–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giannakopoulos, C.; Bindi, M.; Le Sager, P.; Goodess, C.M.; Moriondo, M.; Kostopoulou, E. Climatic Changes and Associated Impacts in the Mediterranean Resulting from a 2 °C Global Warming. Glob. Planet. Change. 2009, 68, 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, D.J. Development of Tools and Techniques to Survey, Assess, Stabilise, Monitor and Preserve Underwater Archaeological Sites: SASMAP. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2015, XL-5/W7, 173–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Elfadaly, A.; Lasaponara, R.; Murgante, B.; Qelichi, M.M. Cultural Heritage Management Using Analysis of Satellite Images and Advanced GIS Techniques at East Luxor, Egypt and Kangavar, Iran (A Comparison Case Study). In Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Including Subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics); Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 152–168. [Google Scholar]

- Bruno, F.; Lagudi, A.; Ritacco, G.; Agrafiotis, P.; Skarlatos, D.; Cejka, J.; Kouril, P.; Liarokapis, F.; Philpin-Briscoe, O.; Poullis, C.; et al. Development and Integration of Digital Technologies Addressed to Raise Awareness and Access to European Underwater Cultural Heritage. An Overview of the H2020 i-MARECULTURE Project. In OCEANS 2017-Aberdeen; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2017; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Olejnik, C. Visual Identification of Underwater Objects Using a ROV-Type Vehicle: “Graf Zeppelin” Wreck Investigation. Pol. Marit. Res. 2008, 15, 72–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugan, I. Using New Technology to Find Shipwrecks on the Ocean Floor; Gemini Research News: Trondheim, Norway, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Bruno, F.; Lagudi, A.; Barbieri, L.; Muzzupappa, M.; Ritacco, G.; Cozza, A.; Cozza, M.; Peluso, R.; Lupia, M.; Cario, G. Virtual and Augmented Reality Tools to Improve the Exploitation of Underwater Archaeological Sites by Diver and Non-Diver Tourists. In Digital Heritage—Progress in Cultural Heritage: Documentation, Preservation, and Protection, 6th International Conference, EuroMed 2016; Ioannides, M., Fink, E., Moropoulou, A., Hagedorn, M., Fresa, A., Liestol, G., Rajcic, V., Grussenmeyer, P., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Nicosia, Cyprus, 2016; pp. 269–280. [Google Scholar]

- MARE CULTURE Project. Advanced VR, iMmersive Serious Games and Augmented REality as Tools to Raise Awareness and Access to European Underwater CULTURal Heritage. Available online: https://imareculture.eu/ (accessed on 2 February 2019).

- Firth, A. Marine Spatial Planning and the Historic Environment; Fjordr: Salisbury, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- EMODnet. Data on Bathymetry (Water Depth), Coastlines, and Geographical Location of Underwater Features: Wrecks. Available online: http://portal.emodnet-bathymetry.eu/ (accessed on 2 February 2019).

- Monfils, R. The Global Risk of Marine Pollution from WWII Shipwrecks: Examples from the Seven Seas. In International Oil Spill Conference Proceedings; American Petroleum Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; Volume 2005, pp. 1049–1054. [Google Scholar]

- Lickliter-Mundon, M.; Cantelas, F.; Coble, W.; Kinney, J.; McKinnon, J.; Meyer, J.; Pietruszka, A.; Pilgrim, B.; Pruitt, J.R.; Van Tilburg, H. Identification of a Deep-Water B-29 WWII Aircraft via ROV Telepresence Survey. J. Marit. Archaeol. 2018, 13, 167–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyropoulos, V.; Giannoulaki, M.; Charalambous, D. (Eds.) Conservation of Underwater Metallic Shipwrecks and Their Finds from the Aegean (in Greek); Dionicos: Athens, Greece, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Van Tilberg, H. Second World War Underwater Cultural Heritage Issues in Hawaii. In Safeguarding Underwater Cultural Heritage in the Pacific; PUCHP, Ed.; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2017; pp. 43–52. [Google Scholar]

- Jeffery, B. Submerged Second World War Sites in Chuuk, Guam, Pohnepei and Yap. In Safeguarding Underwater Cultural Heritage in the Pacific; PUCHP, Ed.; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2017; pp. 53–71. [Google Scholar]

- McKinnon, J. Second World War Underwater Cultural Heritage Management in Saipan. In Safeguarding Underwater Cultural Heritage in the Pacific; PUCHP, Ed.; UNESCO: Paris, France, 2017; pp. 31–42. [Google Scholar]

- Kimura, J. Interpreting Maritime Cultural Space through the Utilization of GIS: A Case Study of the Spatial Meaning of Shipwrecks in the Coastal Waters of South Australia. Master’s Thesis, Flinders University, Adelaide, Australia, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Nairn, A.D. The Development of an Australian Marine Spatial Information System (AMSIS) to Support Australian Government Ocean Policy and Multi-Use Marine Activities. In Coastal and Marine Geospatial Technologies; Green, D.R., Ed.; Coastal Systems and Continental Margins; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2010; Volume 13, pp. 17–27. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCO. The Side Event on Safeguarding Underwater Cultural Heritage (UCH) for Sustainable Development Took Place on 1 November 2018 at the Inter-Regional Meeting for the Mid-Term Review of the SAMOA Pathway (Apia, 30 October–1 November 2018). Available online: http://www.unesco.org/new/pt/culture/themes/underwater-cultural-heritage/dynamic-content-single-view/news/safeguarding_underwater_cultural_heritage_for_blue_economy-1/ (accessed on 2 February 2019).

- Said, S.Y.; Zainal, S.S.; Thomas, M.G.; Goodey, B. Sustaining Old Historic Cities through Heritage-Led Regeneration. WIT Trans. Ecol. Environ. 2013, 179, 267–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, M.D.; Go, F.M.; Yuksel, A. (Eds.) Heritage Tourism Destinations: Preservation, Communication and Development; CAB International: Boston, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Towards an Integrated Approach to Cultural Heritage for Europe; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the Council and the European Parliament—Thematic Strategy on the Protection and Conservation of the Marine Environment; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. A European Strategy for More Growth and Jobs in Coastal and Maritime Tourism; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Michel, J.; Gilbert, T.; Etkin, D.S.; Urban, R.; Waldron, J.; Blocksidge, C.T. An Issue Paper Prepared for the 2005 International Oil Spill Conference: Potentially Polluting Wrecks in Marine Waters. In International Oil Spill Conference Proceedings; American Petroleum Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2005; Volume 2005, pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Landquist, H.; Hassellöv, I.-M.; Rosén, L.; Lindgren, J.F.; Dahllöf, I. Evaluating the Needs of Risk Assessment Methods of Potentially Polluting Shipwrecks. J. Environ. Manag. 2013, 119, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spira, J. Wrecks and Reefs! Spira International Inc.: Huntington Beach, CA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Genç, T.S.; Özgül, A.; Lök, A. The Use of Artificial Reefs for Recreational Diving. Turk. J. Marit. Mar. Sci. 2017, 3, 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Stratigea, A.; Katsoni, V. A Strategic Policy Scenario Analysis Framework for the Sustainable Tourist Development of Peripheral Small Island Areas—The Case of Lefkada-Greece Island. Eur. J. Futures Res. 2015, 3, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Blue Growth Opportunities for Marine and Maritime Sustainable Growth; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Commission Staff Working Document Report on the Blue Growth Strategy towards More Sustainable Growth and Jobs in the Blue Economy; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Panagiotopoulou, M.; Somarakis, G.; Stratigea, A. Smartening Up Participatory Cultural Tourism Planning in Historical City Centers. J. Urban Technol. 2018, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- List, R.A.; Hadeed, M.; Goldzweig, R.S.; Cohen, J.L. Online Participation in Culture and Politics: Towards More Democratic Societies? Council of Europe: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Hannahs, T. Underwater Parks Versus Preserves: Data or Access; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2003; pp. 5–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott-Ireton, D.A. The Value of Public Education and Interpretation in Submerged Cultural Resource Management. In Out of the Blue; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2007; pp. 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Altvater, S. How to Integrate Maritime Cultural Heritage into Maritime Spatial Planning? Available online: https://www.submariner-network.eu/images/events/betteroffblue17/5_wsC_SAltvater-ilovepdf-compressed.pdf (accessed on 10 February 2019).

- Balint, P.J.; Stewart, R.E.; Desa, A.; Walters, L.C. Wicked Environmental Problems Managing Uncertainty and Conflict; Island Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Boyd, B.; Cotter, M.; O’Connor, W.; Sattler, D. Cognitive Ownership of Cultural Places: Social Construction and Cultural Heritage Management. Tempus 1996, 6, 123–140. [Google Scholar]

- Kisić, V. Governing Heritage Dissonance-Promises and Realities of Selected Cultural Policies; European Cultural Foundation: Belgrade, Serbia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Papuccular, H. Fragmented Memories the Dodecanese Islands during WWII. In Heritage and Memory of War Responses from Small Islands; Gilly, C., Keir, R., Eds.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2015, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jordi, P.B.; Čopič, V.; Srakar, A. Literature Review on Cultural Governance and Cities. Kult-ur 2014, 1, 183–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Council of the European Union. Council Conclusions on Participatory Governance of Cultural Heritage; The Council of the European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2014; pp. 22–24. [Google Scholar]

- Dromgoole, S. The Evolution of International Law on Underwater Cultural Heritage. In Underwater Cultural Heritage and International Law; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2013; pp. 28–64. [Google Scholar]

- Jameson, J.H. Not All Wet: Public Presentation, Stewardship, and Interpretation of Terrestrial vs. Underwater Sites. In Out of the Blue; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2007; pp. 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Fredheim, L.H.; Khalaf, M. The Significance of Values: Heritage Value Typologies Re-Examined. Int. J. Herit. Stud. 2016, 22, 466–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pye, E. Caring for the Past: Issues in Conservation for Archaeology and Museums; James & James: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Van Vliet, W. The Future of Relics from a Military Past; University of Groningen: Groningen, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fatorić, S.; Seekamp, E. A Measurement Framework to Increase Transparency in Historic Preservation Decision-Making under Changing Climate Conditions. J. Cult. Herit. 2018, 30, 168–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shearing, S. Here Today, Gone Tomorrow? Climate Change and World Heritage; Macquarie Law Working Paper Series; Macquarie University: Sydney, Australia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Alvaro, E. Climate Change and Underwater Cultural Heritage: Impacts and Challenges. J. Cult. Herit. 2016, 21, 842–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EEA. The European Environment—State and Outlook; EEA: Luxembourg, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Panagou, N.; Kokkali, A.; Stratigea, A. Towards an Integrated Participatory Marine/Coastal and Territorial Spatial Planning Approach at the Local Level-Planning Tools and Issues Raised. Reg. Sci. Inq. 2018, 10, 87–111. [Google Scholar]

- CBI. CBI Product Factsheet: Dive Tourism from Europe; CBI: The Hague, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- PADI. PADI 2019 Worldwide Corporate Statistics, Data for 2013–2018; PADI: Rancho Santa Margarita, CA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Poon, A. Tourism, Technology and Competitive Strategies; CAB International: Oxon, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Lazaretou, S. Smart Economy—Cultural and Creative Industry in Greece: Can They Support a Way Out from Recession Period? (in Greek), Working Papers 175, Bank of Greece Report. 2014, pp. 73–704. Available online: http://www.bankofgreece.gr/BogEkdoseis/Paper2014175.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2019).

- Papageorgiou, M.; Kyvelou, S. Aspects of Marine Spatial Planning and Governance: Adapting to the Transboundary Nature and the Special Conditions of the Sea. Eur. J. Environ. Sci. 2018, 8, 31–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dissonant Heritage. Available online: https://dissonantheritage.wordpress.com/ (accessed on 28 May 2019).

- Cobb, E. Cultural Heritage in Conflict: World Heritage Cities of the Middle East. Master’s Thesis, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Trindade Lopes, M.H.; Almeida, I.C.G. The Mediterranean: The Asian and African Roots of the Cradle of Civilization. In Mediterranean Identities—Environment, Society, Culture; Fuerst-Bjelis, B., Ed.; InTech: Croacia, 2017. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Argyropoulos, V.; Stratigea, A. Sustainable Management of Underwater Cultural Heritage: The Route from Discovery to Engagement—Open Issues in the Mediterranean. Heritage 2019, 2, 1588-1613. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage2020098

Argyropoulos V, Stratigea A. Sustainable Management of Underwater Cultural Heritage: The Route from Discovery to Engagement—Open Issues in the Mediterranean. Heritage. 2019; 2(2):1588-1613. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage2020098

Chicago/Turabian StyleArgyropoulos, Vasilike, and Anastasia Stratigea. 2019. "Sustainable Management of Underwater Cultural Heritage: The Route from Discovery to Engagement—Open Issues in the Mediterranean" Heritage 2, no. 2: 1588-1613. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage2020098

APA StyleArgyropoulos, V., & Stratigea, A. (2019). Sustainable Management of Underwater Cultural Heritage: The Route from Discovery to Engagement—Open Issues in the Mediterranean. Heritage, 2(2), 1588-1613. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage2020098