Bioinspired Mechanical Materials—Development of High-Toughness Ceramics through Complexation of Calcium Phosphate and Organic Polymers

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The Structure of Bone and Related Tissues

2.1. Carbonated Apatite and Its Interface

2.2. Biosynthesis of Bone

2.3. Bioceramics and Woods as Biological Mechanical Materials

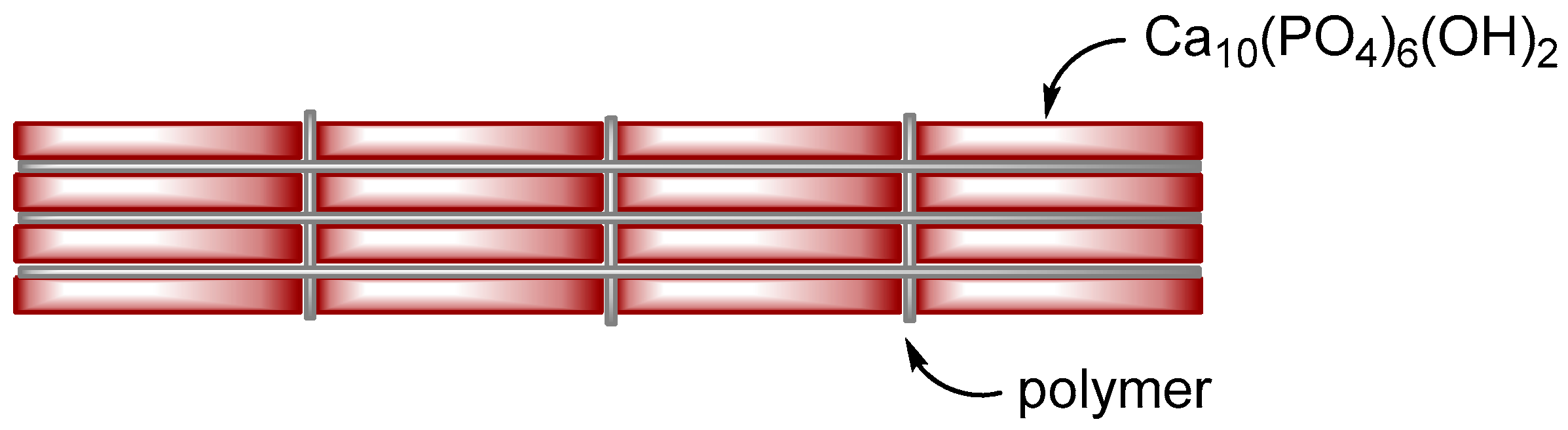

3. Composite Materials Related to Bone

3.1. General Features of Organic–Inorganic Composites

3.2. Preparation of Organic–Inorganic Composites

- Direct mixing of polymer and inorganic crystals.

- Polymerization of the monomer in the presence of the inorganic crystal powder.

- Crystallization of the inorganic phase in the presence of the organic polymer.

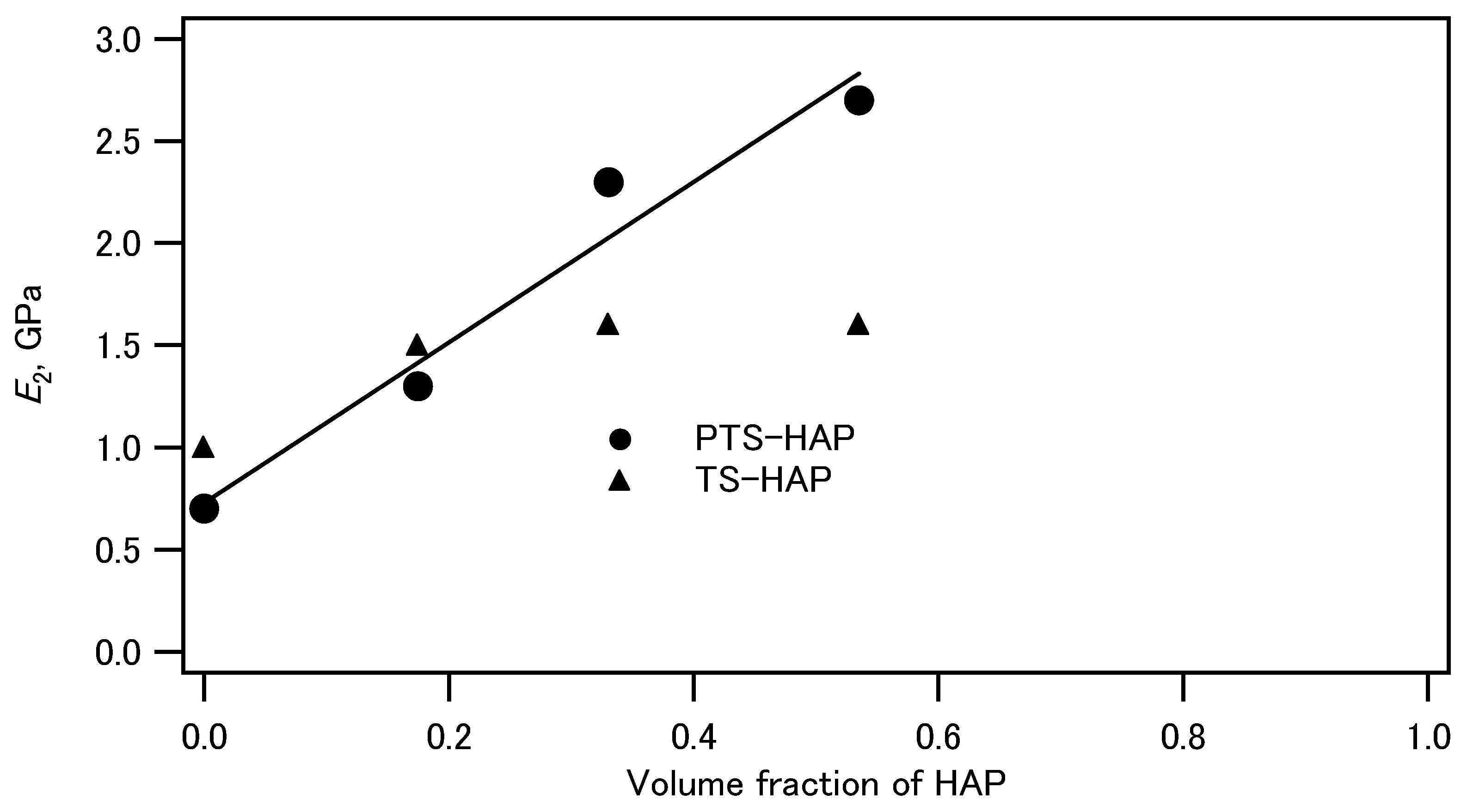

3.3. Composite of Hydroxyapatite and Polysaccharide

3.3.1. Creating Green Structural Materials in an Environmentally Friendly Process

3.3.2. Starch–Hydroxyapatite Composites

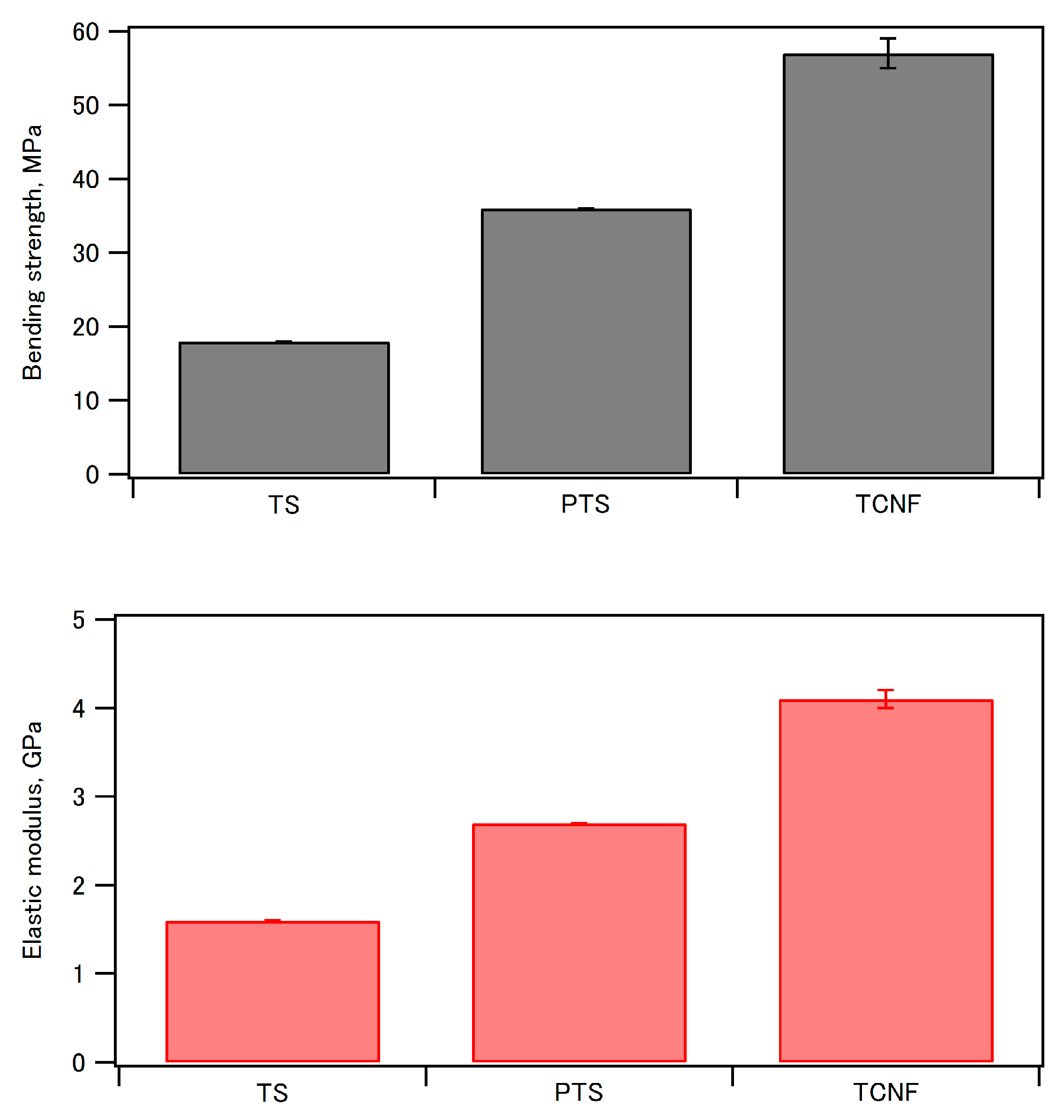

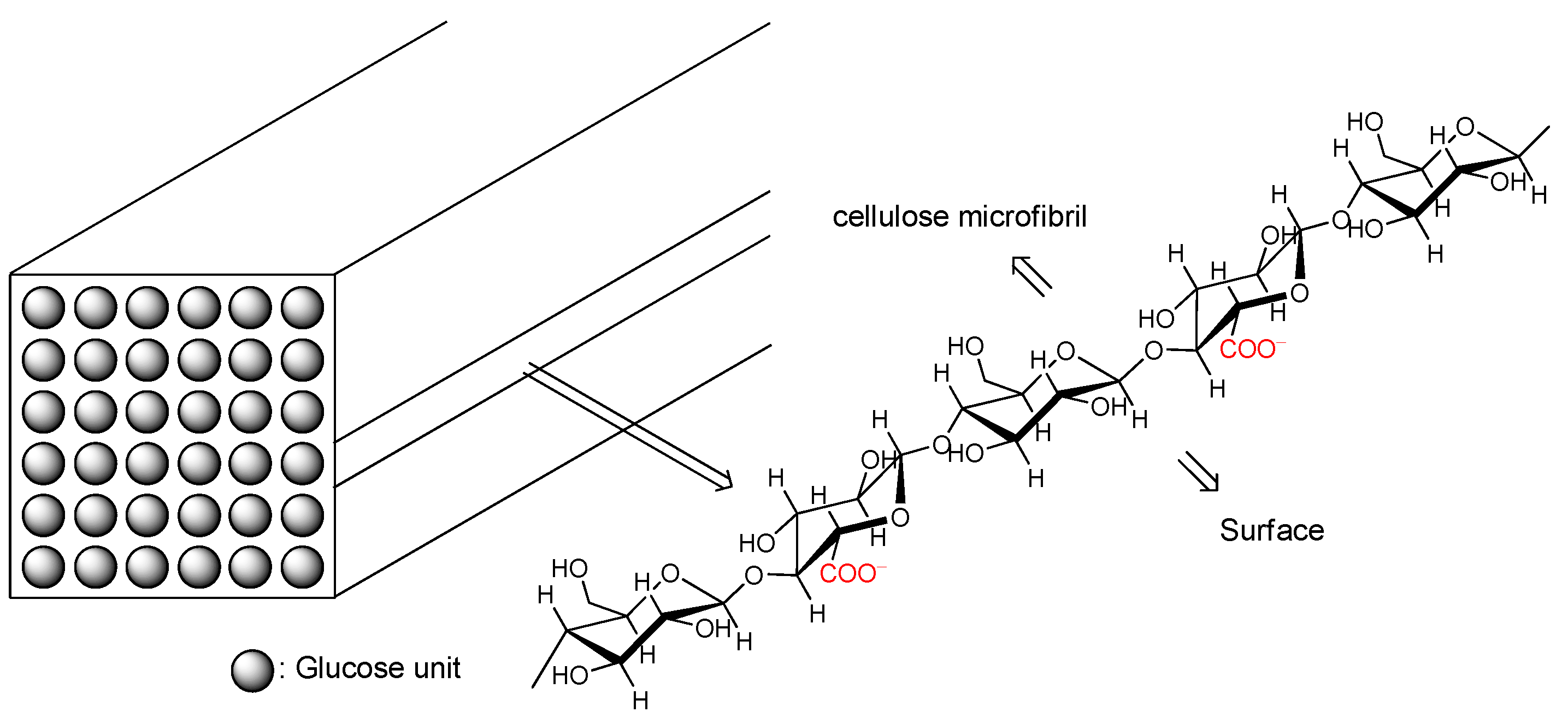

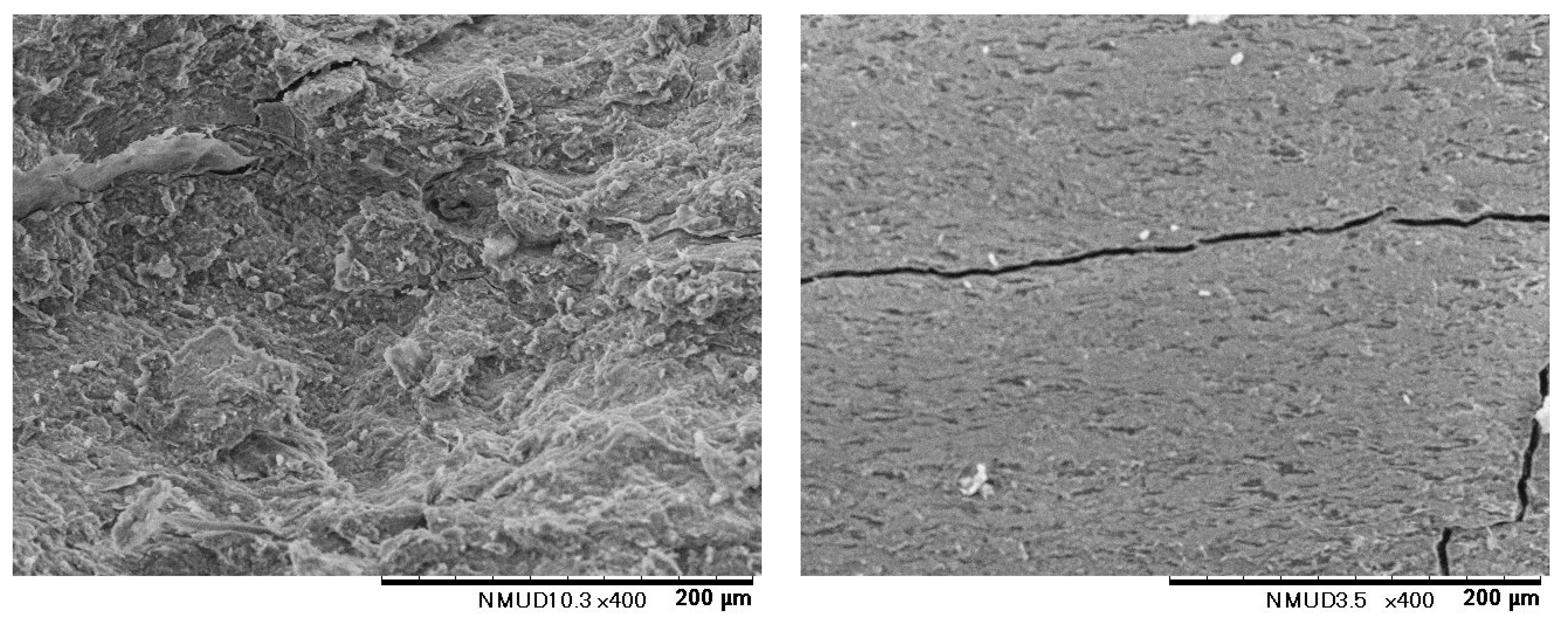

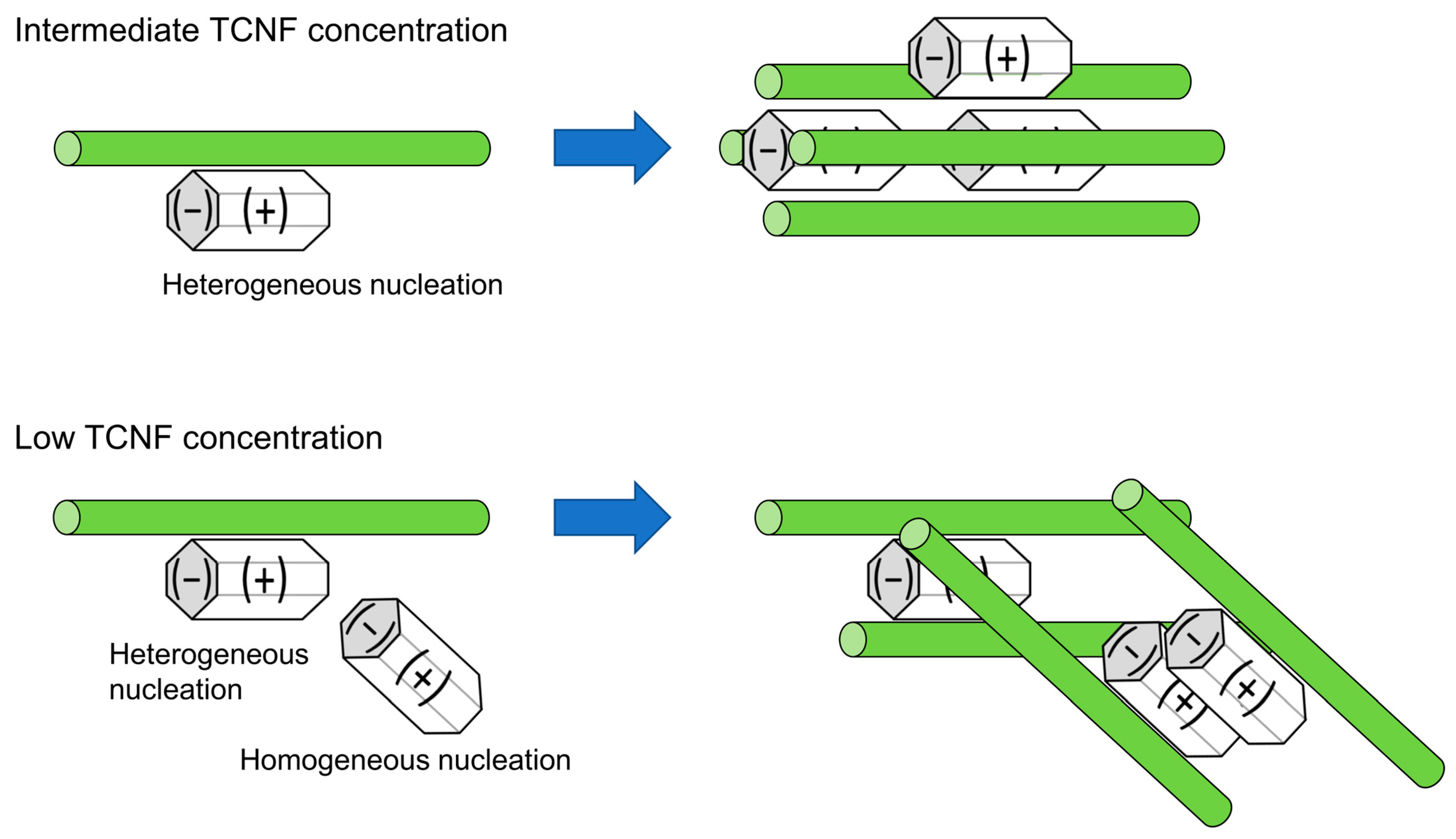

3.3.3. Cellulose Nanofibers–Hydroxyapatite Composites

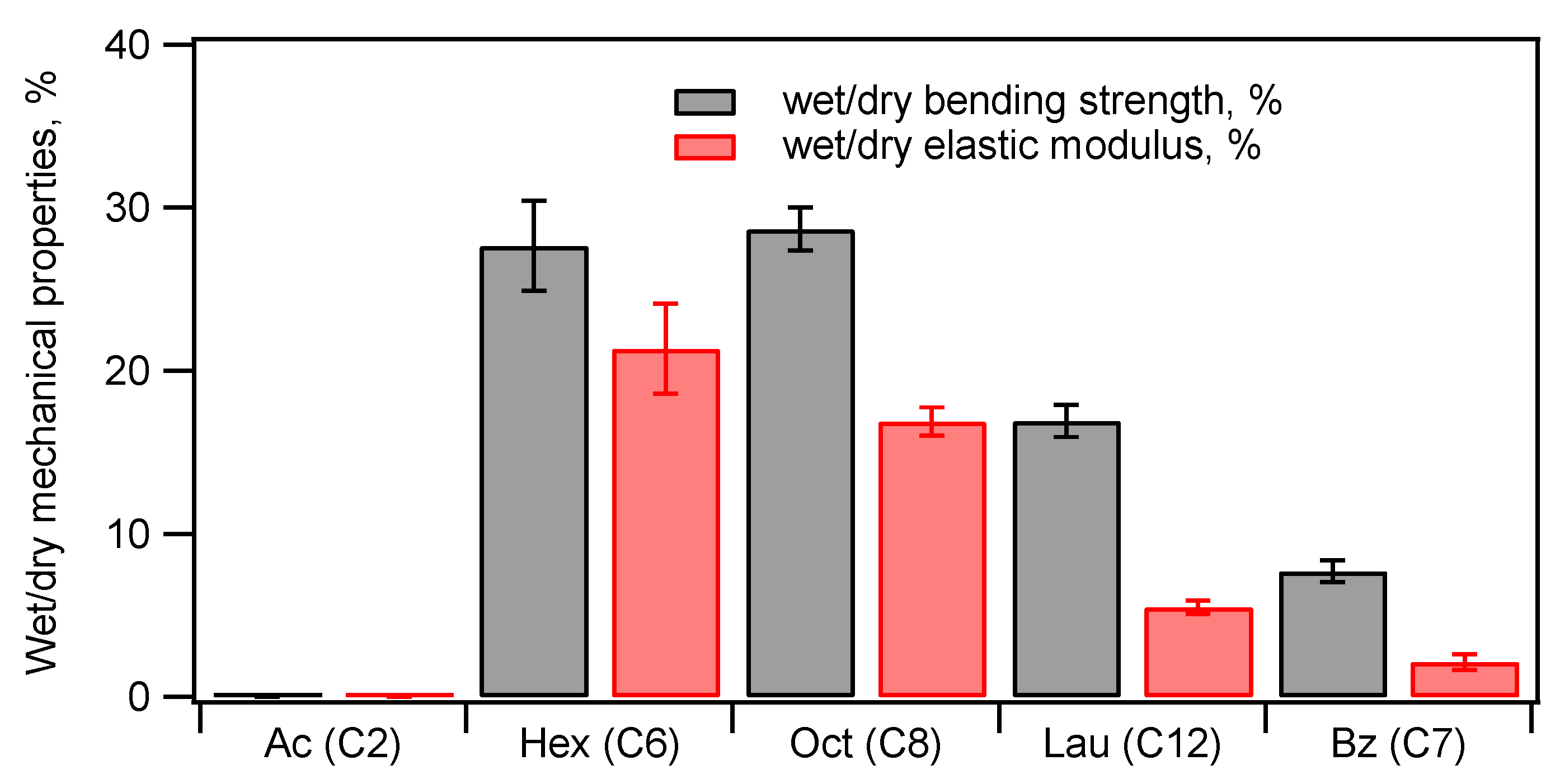

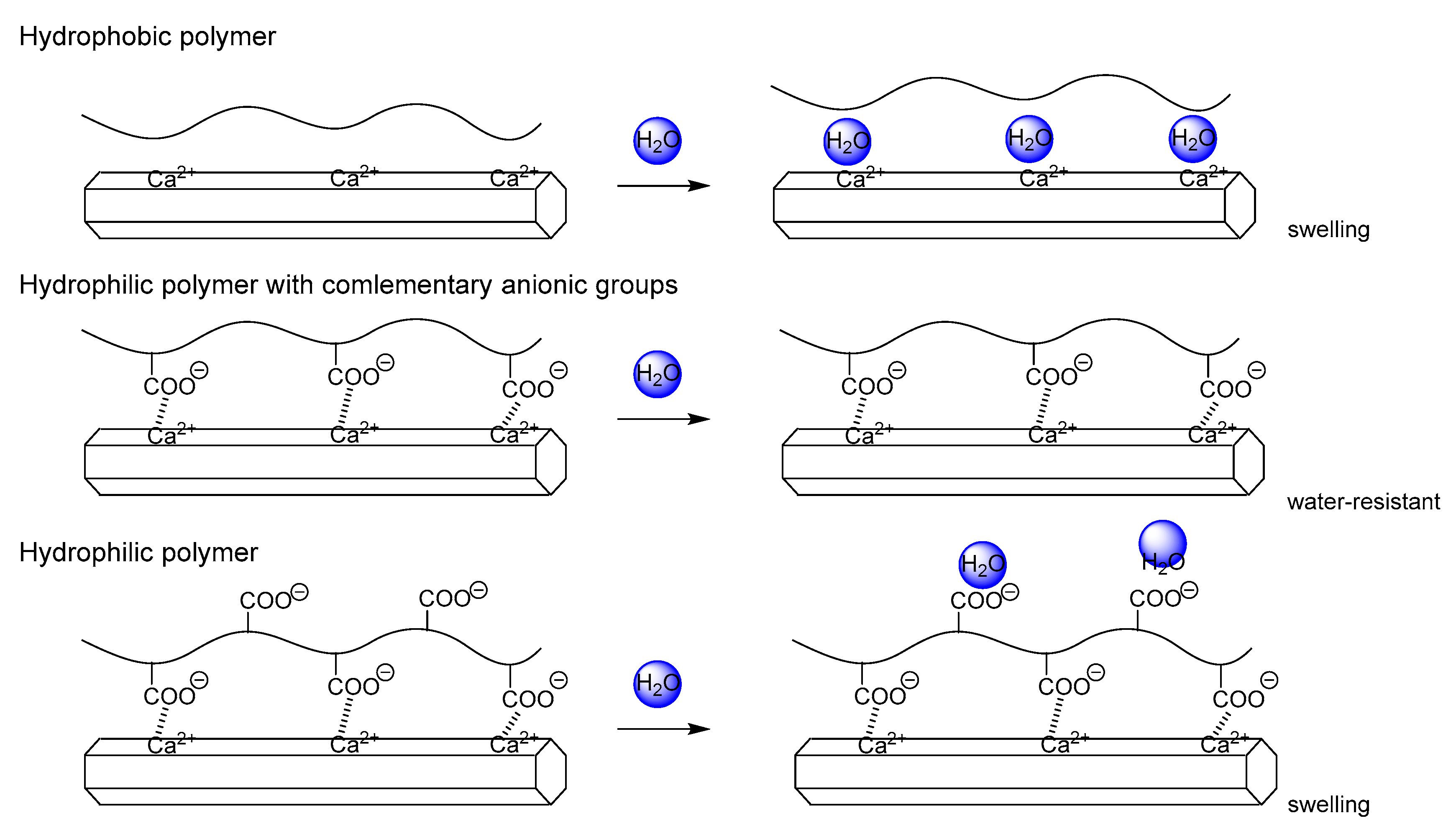

3.4. Introduction of Hydrophobic Groups for Water-Resistance Enhancement

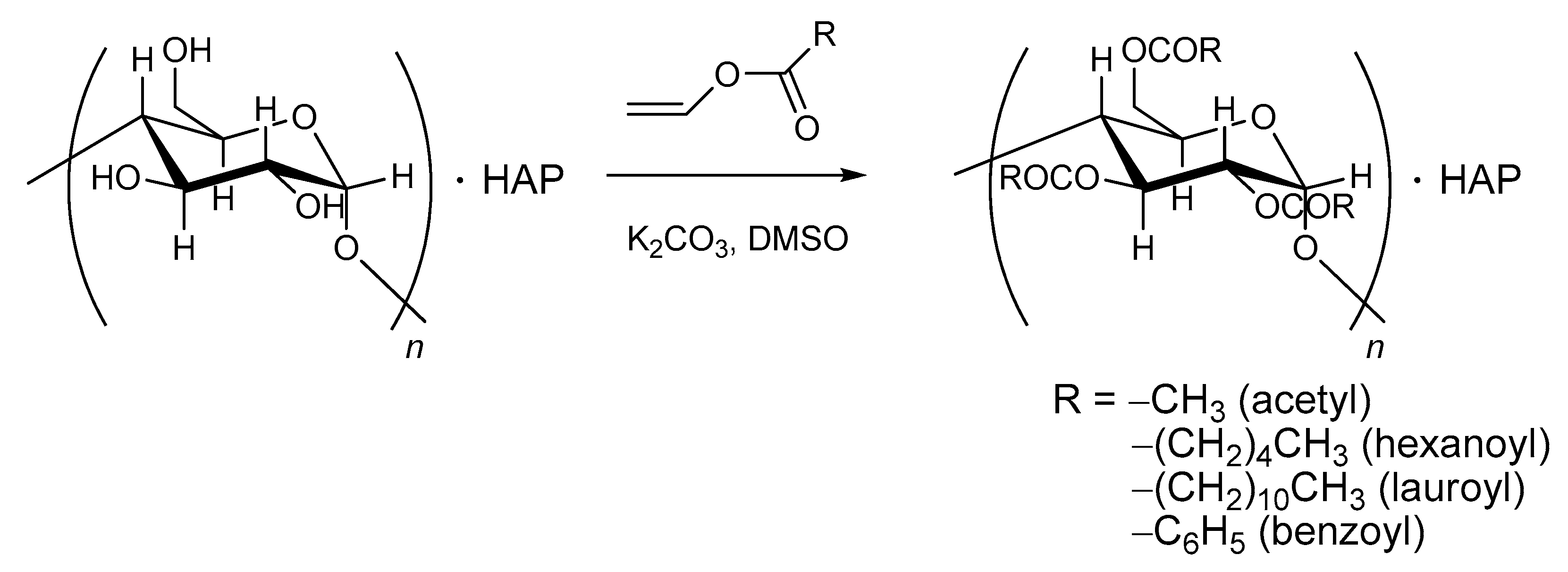

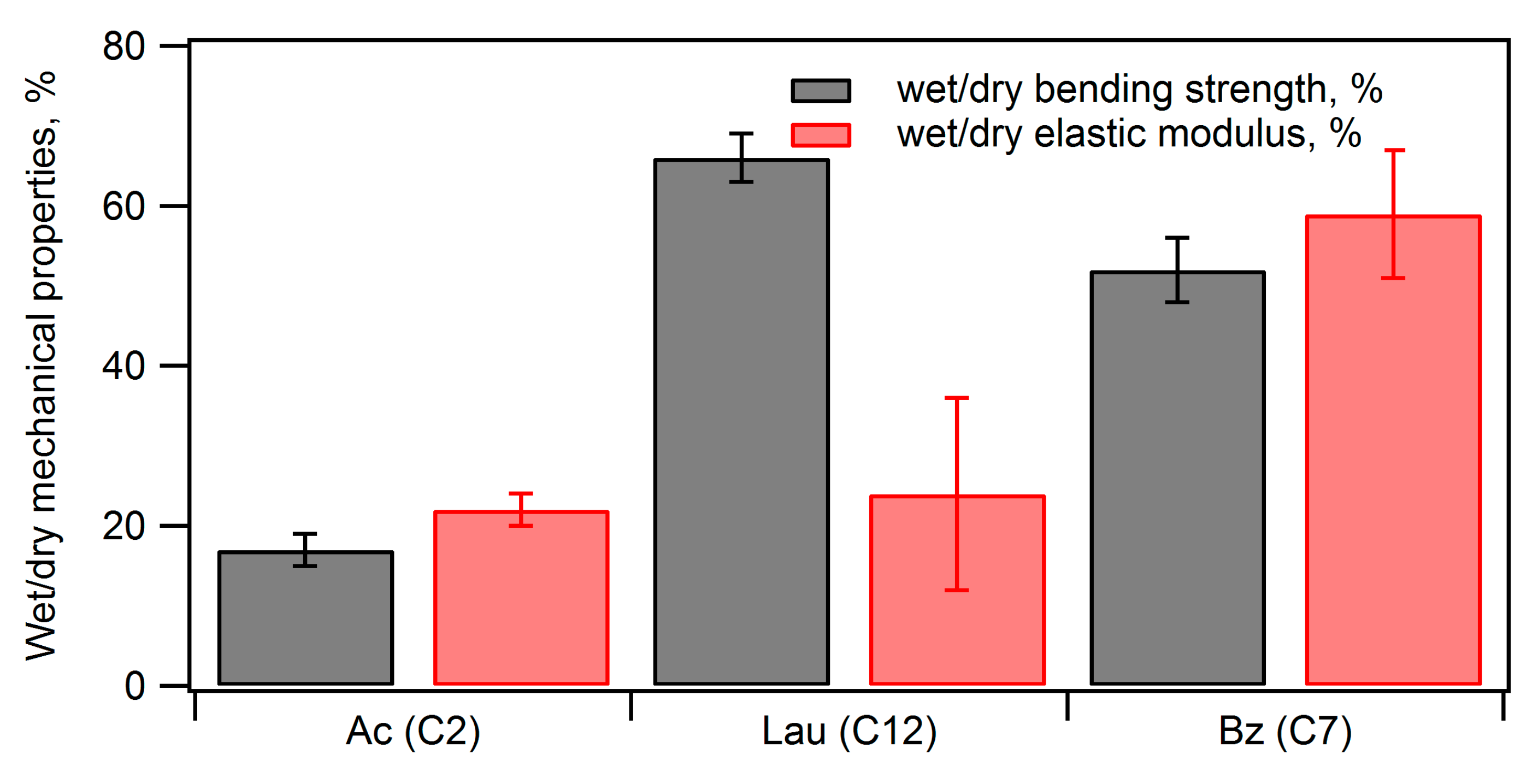

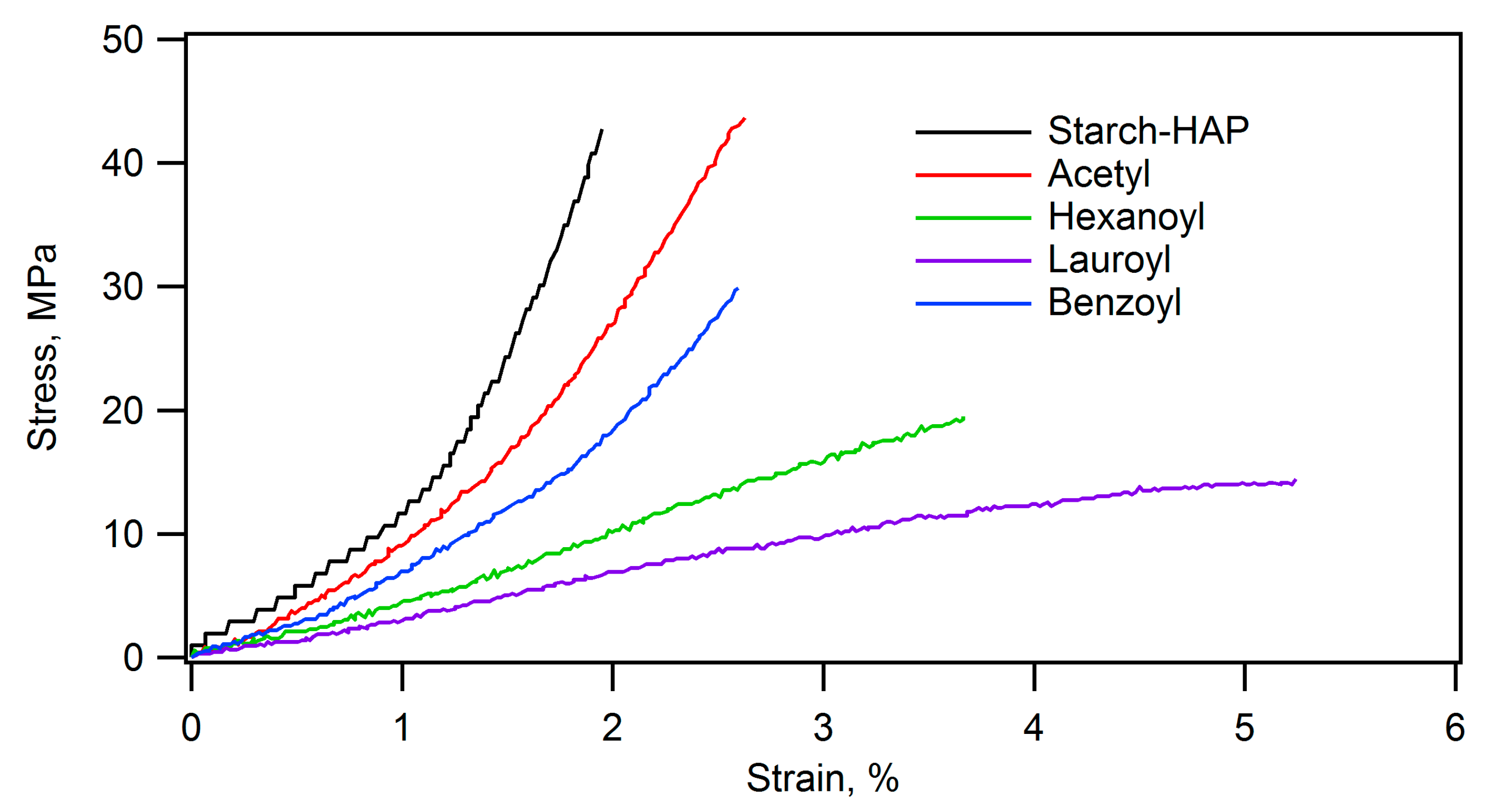

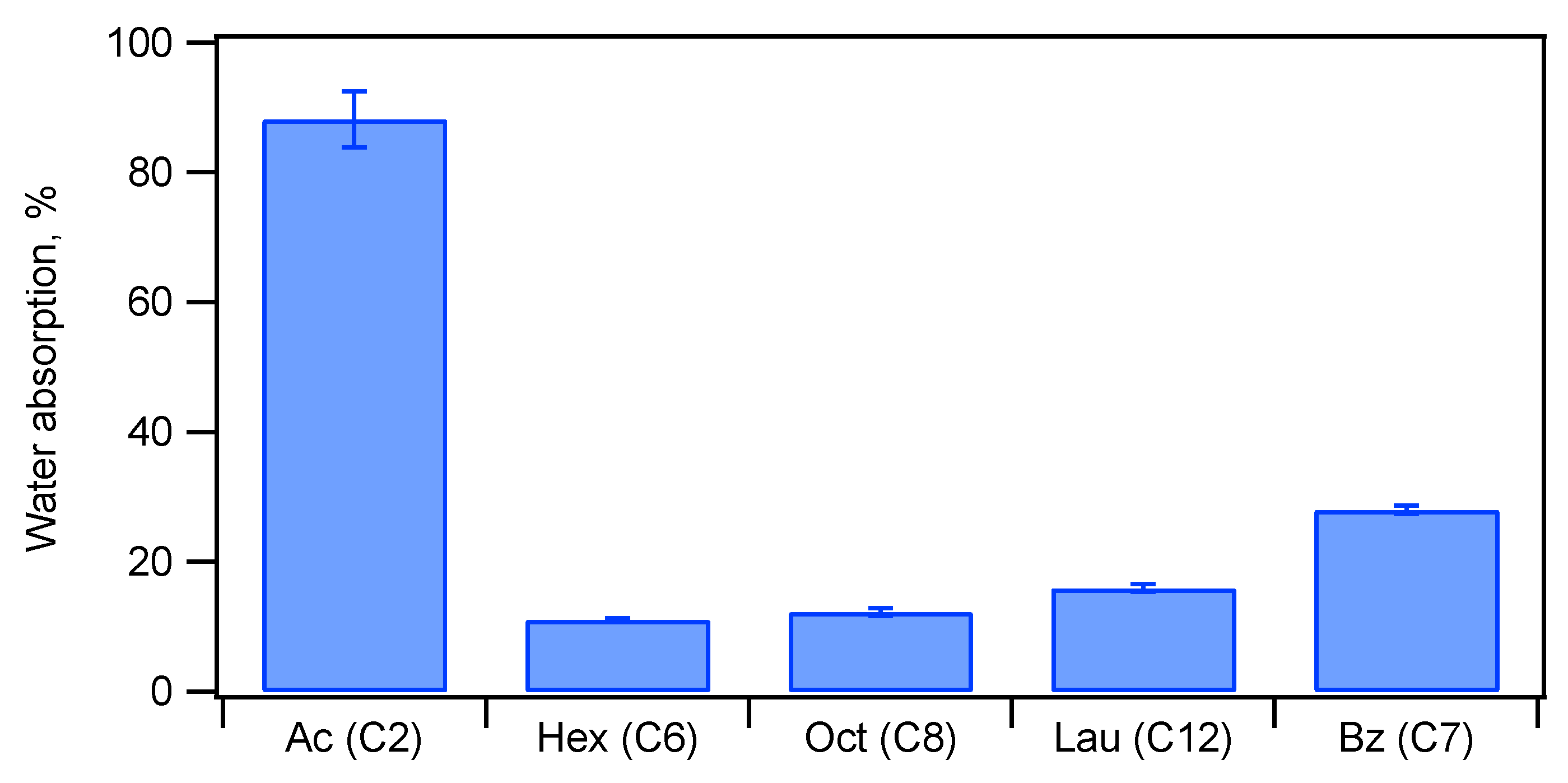

3.4.1. Acylation of Phosphorylated Starch–HAP Composites

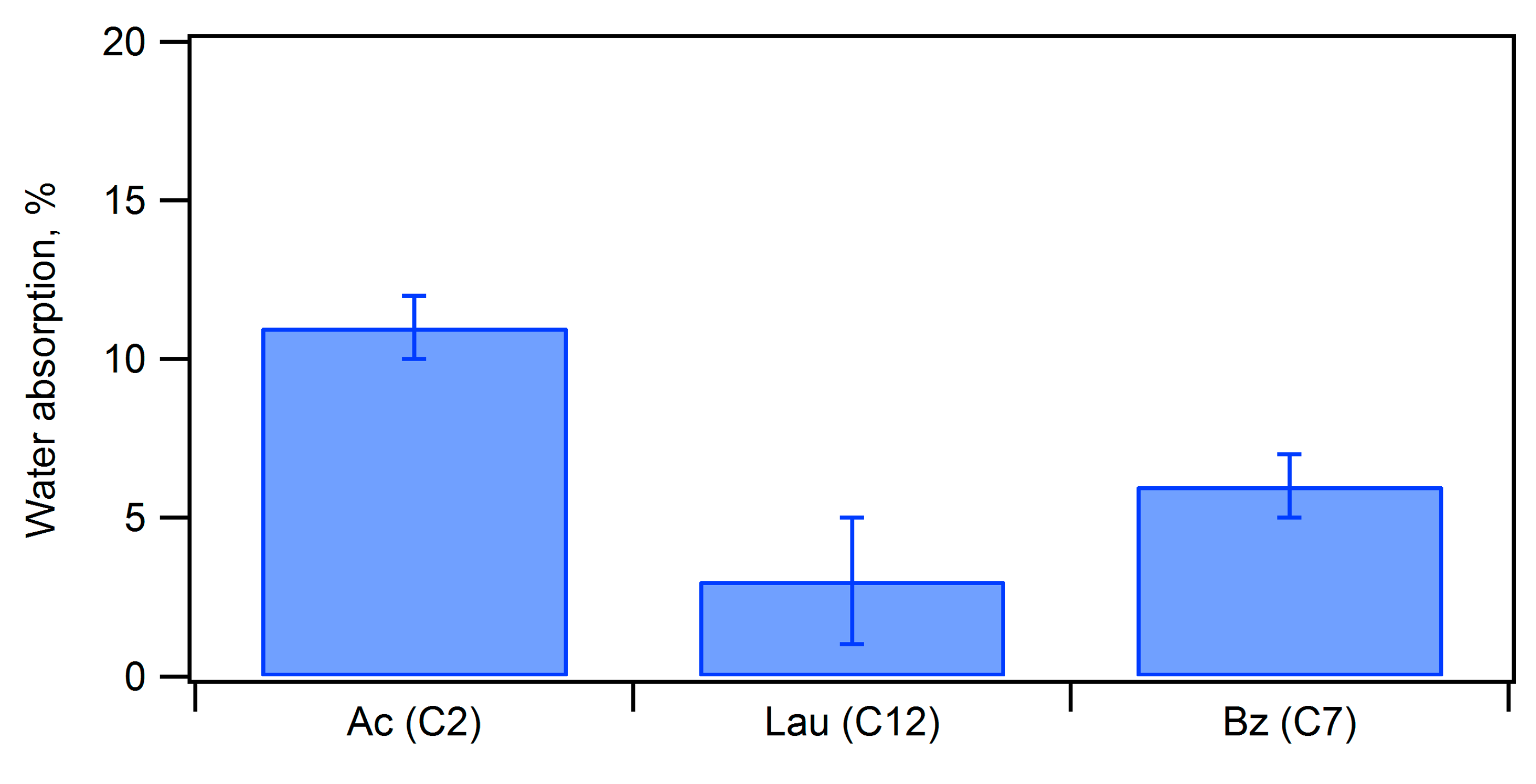

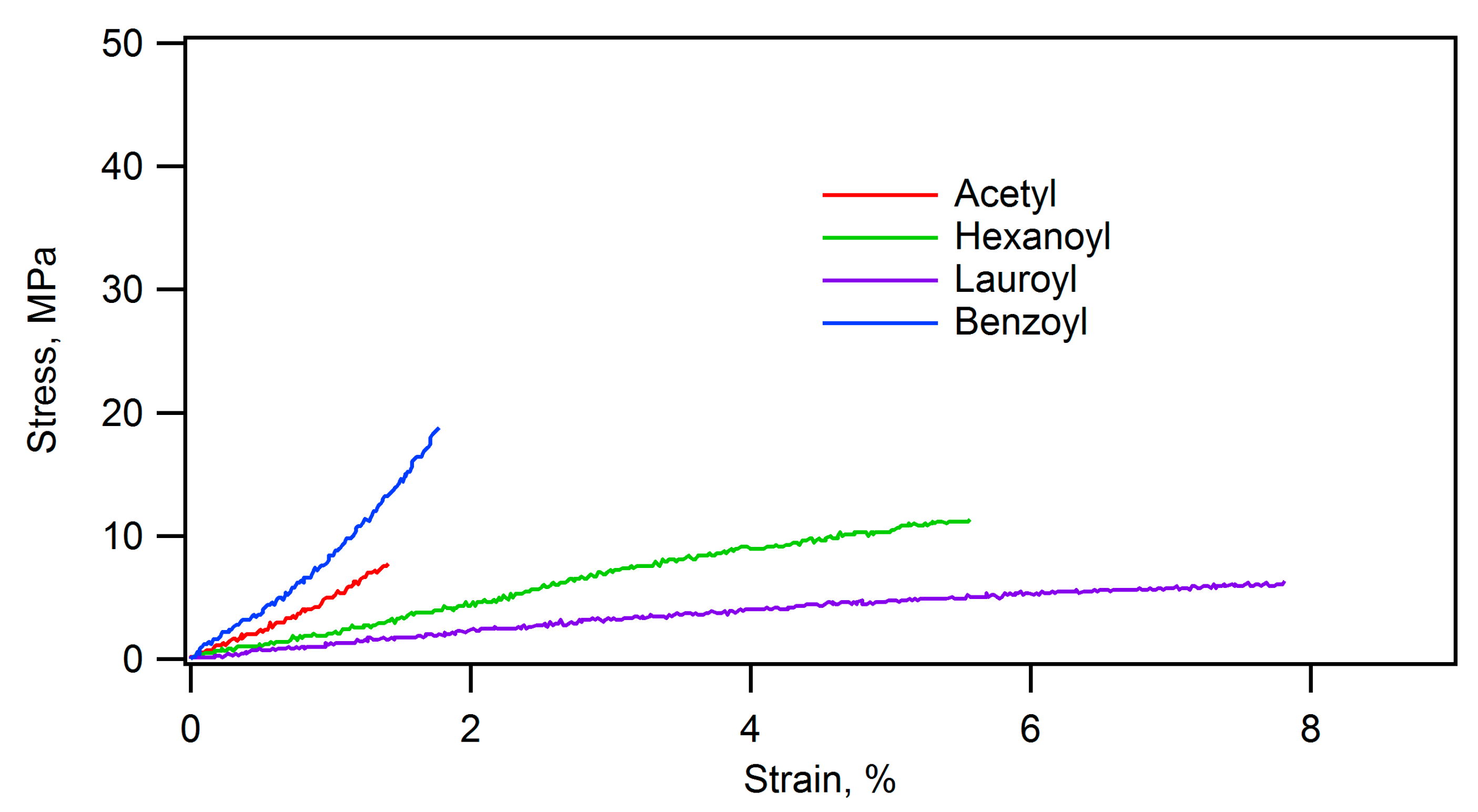

3.4.2. Acylation of TCNF–HAP Composites

3.4.3. Comparison of the Water Resistance of Starch–HAP, Cellulose–HAP, and Poly(DL-lactide)–HAP

4. Future Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Elias, H.-G. An Introduction to Polymer Science; VCH: Berlin, Germany, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Eerkes-Medrano, D.; Thompson, R.C.; Aldridge, D.C. Microplastics in freshwater systems: A review of the emerging threats, identification of knowledge gaps and prioritisation of research needs. Water Res. 2015, 75, 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stock, S.R. The Mineral-Collagen Interface in Bone. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2015, 97, 262–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nudelman, F.; Lausch, A.J.; Sommerdijk, N.A.J.M.; Sone, E.D. In vitro models of collagen biomineralization. J. Struct. Biol. 2013, 183, 258–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Q.; Yang, H.; Han, Z.; Ling, Z.; Yu, S. An all-natural bioinspired structural material for plastic replacement. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 5401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curto, M.; Le Gall, M.; Catarino, A.I.; Niu, Z.; Davies, P.; Everaert, G.; Dhakal, H.N. Long-term durability and ecotoxicity of biocomposites in marine environments: A review. RSC Adv. 2021, 11, 32917–32941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olszta, M.J.; Cheng, X.; Jee, S.S.; Kumar, R.; Kim, Y.; Kaufman, M.J.; Douglas, E.P.; Gower, L.B. Bone structure and formation: A new perspective. Mater. Sci. Eng. R 2007, R58, 77–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granke, M.; Does, M.D.; Nyman, J.S. The Role of Water Compartments in the Material Properties of Cortical Bone. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2015, 97, 292–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorozhkin, S.V.; Epple, M. Biological and Medical Significance of Calcium Phosphates. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 3130–3146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, S.; Wagner, H.D. The Material Bone: Structure-Mechanical Function Relations. Annu. Rev. Mater. Sci. 1998, 28, 271–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Ji, B.; Jager, I.L.; Arzt, E.; Fratzl, P. Materials become insensitive to flaws at nanoscale: Lessons from nature. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 2003, 100, 5597–5600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouville, F.; Maire, E.; Meille, S.; Van de Moortele, B.; Stevenson, A.J.; Deville, S. Strong, tough and stiff bioinspired ceramics from brittle constituents. Nat. Mater. 2014, 13, 508–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilbrink, D.V.; Utz, M.; Ritchie, R.O.; Begley, M.R. Scaling of strength and ductility in bioinspired brick and mortar composites. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2010, 97, 193701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Gupta, H.S. Deformation and Fracture Mechanisms of Bone and Nacre. Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 2011, 41, 41–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakhavand, N.; Shahsavari, R. Universal composition-structure property maps for natural and biomimetic platelet-matrix composites and stacked heterostructures. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currey, J.D. What determines the bending strength of compact bone? J. Exp. Biol. 1999, 202, 2495–2503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nalla, R.K.; Balooch, M.; Ager, J.W., III; Kruzic, J.J.; Kinney, J.H.; Ritchie, R.O. Effects of polar solvents on the fracture resistance of dentin: Role of water hydration. Acta Biomater. 2005, 1, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, E.E.; Awonusi, A.; Morris, M.D.; Kohn, D.H.; Tecklenburg, M.M.J.; Beck, L.W. Three structural roles for water in bone observed by solid-state NMR. Biophys. J. 2006, 90, 3722–3731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Samuel, J.; Sinha, D.; Zhao, J.C.; Wang, X. Water residing in small ultrastructural spaces plays a critical role in the mechanical behavior of bone. Bone 2014, 59, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul-E-Noor, F.; Singh, C.; Papaioannou, A.; Sinha, N.; Boutis, G.S. Behavior of Water in Collagen and Hydroxyapatite Sites of Cortical Bone: Fracture, Mechanical Wear, and Load Bearing Studies. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 21528–21537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nyman, J.S.; Roy, A.; Shen, X.; Acuna, R.L.; Tyler, J.H.; Wang, X. The influence of water removal on the strength and toughness of cortical bone. J. Biomech. 2006, 39, 931–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitta Kruize, C.; Panahkhahi, S.; Putra, N.E.; Diaz-Payno, P.; van Osch, G.; Zadpoor, A.A.; Mirzaali, M.J. Biomimetic Approaches for the Design and Fabrication of Bone-to-Soft Tissue Interfaces. ACS Biomater. Sci. Eng. 2023, 9, 3810–3831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, J.M.; Cameron, M.; Crowley, K.D. Structural variations in natural F, OH, and Cl apatites. Am. Mineral. 1989, 74, 870–876. [Google Scholar]

- Dorozhkin, S.V. Calcium Orthophosphates in Nature, Biology and Medicine. Materials 2009, 2, 399–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, K.; Kogure, T.; Kumagai, Y.; Tanaka, J. Crystal Orientation of Hydroxyapatite Induced by Ordered Carboxyl Groups. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2001, 240, 133–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Y.-Y.; Rawal, A.; Schmidt-Rohr, K. Strongly bound citrate stabilizes the apatite nanocrystals in bone. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 52, 22425–22429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wise, E.R.; Maltsev, S.; Davies, M.E.; Duer, M.J.; Jaeger, C.; Loveridge, N.; Murray, R.C.; Reid, D.G. The Organic-Mineral Interface in Bone Is Predominantly Polysaccharide. Chem. Mater. 2007, 19, 5055–5057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eden, M. Structure and formation of amorphous calcium phosphate and its role as surface layer of nanocrystalline apatite: Implications for bone mineralization. Materialia 2021, 17, 101107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gower, L.B. Biomimetic Model Systems for Investigating the Amorphous Precursor Pathway and Its Role in Biomineralization. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 4551–4627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, A.; Veis, A. Phosphorylated Proteins and Control over Apatite Nucleation, Crystal Growth, and Inhibition. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 4670–4693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rho, J.; Kuhn-Spearing, L.; Zioupos, P. Mechanical properties and the hierarchical structure of bone. Med. Eng. Phys. 1998, 20, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barthelat, F.; Yin, Z.; Buehler, M.J. Structure and mechanics of interfaces in biological materials. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2016, 1, 16007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fratzl, P.; Weinkamer, R. Nature’s hierarchical materials. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2007, 52, 1263–1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nudelman, F.; Pieterse, K.; George, A.; Bomans, P.H.H.; Friedrich, H.; Brylka, L.J.; Hilbers, P.A.J.; de With, G.; Sommerdijk, N.A.J.M. The role of collagen in bone apatite formation in the presence of hydroxyapatite nucleation inhibitors. Nat. Mater. 2010, 9, 1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinosa, H.D.; Rim, J.E.; Barthelat, F.; Buehler, M.J. Merger of structure and material in nacre and bone? Perspectives on de novo biomimetic materials. Prog. Mater. Sci. 2009, 54, 1059–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagermaier, W.; Klaushofer, K.; Fratzl, P. Fragility of Bone Material Controlled by Internal Interfaces. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2015, 97, 201–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okada, A.; Usuki, A. Twenty Years of Polymer-Clay Nanocomposites. Macromol. Mater. Eng. 2006, 291, 1449–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfield, W.; Grynpas, M.D.; Tully, A.E.; Bowman, J.; Abram, J. Hydroxyapatite reinforced polyethylene—A mechanically compatible implant material for bone replacement. Biomaterials 1981, 2, 185–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeoka, Y.; Hayashi, M.; Sugiyama, N.; Yoshizawa-Fujita, M.; Aizawa, M.; Rikukawa, M. In situ preparation of poly(L-lactic acid-co-glycolic acid)/hydroxyapatite composites as artificial bone materials. Polym. J. 2015, 47, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stupp, S.I.; Ciegler, G.W. Organoapatite: Materials for artificial bone. I. Synthesis and microstructure. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 1992, 26, 169–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Embery, G.; Rees, S.; Hall, R.; Rose, K.; Waddington, R.; Shellis, P. Calcium- and hydroxyapatite binding properties of glucuronic acid-rich and iduronic acid-rich glycosaminoglycans and proteoglycans. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 1998, 106, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kirkham, J.; Brookes, S.J.; Shore, R.C.; Wood, S.R.; Smith, D.A.; Zhang, J.; Chen, H.; Robinson, C. Physico-chemical properties of crystal surfaces in matrix-mineral interactions during mammalian biomineralisation. Current Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2002, 7, 124–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertoni, E.; Bigi, A.; Falini, G.; Panzavolta, S.; Roveri, N. Hydroxyapatite/polyacrylic acid nanocrystals, J. Mater. Chem. 1999, 9, 779–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J.; Saiz, E.; Bertozzi, C.R. A New Approach to Mineralization of Biocompatible Hydrogel Scaffolds: An Efficient Process toward 3-Dimensional Bonelike Composites. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 1236–1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, M.; Ikoma, T.; Itoh, S.; Matsumoto, H.N.; Koyama, Y.; Takakuda, K.; Shinomiya, K.; Tanaka, J. Biomimetic synthesis of bone-like nanocomposites using the self-organization mechanism of hydroxyapatite and collagen. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2004, 64, 819–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pramanik, N.; Biswas, S.K.; Pramanik, P. Synthesis and Characterization of Hydroxyapatite/Poly(Vinyl Alcohol Phosphate) Nanocomposite Biomaterials. Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 2008, 5, 20–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meldrum, F.C.; Coelfen, H. Controlling Mineral Morphologies and Structures in Biological and Synthetic Systems. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 4332–4432. [Google Scholar]

- Fujisawa, R.; Tamura, M. Acidic bone matrix proteins and their roles in calcification. Front. Biosci. 2012, 17, 1891–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleman, R.J.; Jack, K.S.; Perrier, S.; Grondahl, L. Hydroxyapatite Mineralization in the Presence of Anionic Polymers. Cryst. Growth Des. 2013, 13, 4252–4259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veis, A.; Dorvee, J.R. Biomineralization Mechanisms: A New Paradigm for Crystal Nucleation in Organic Matrices. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2013, 93, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Liu, Q.; Zhao, Z.; Wang, W.; Zheng, L.; Li, Z. Preparation and Characterization of Phosphorylated Collagen and Hydroxyapatite Composite as a Potential Bone Substitute. Chem. Lett. 2013, 42, 83–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morimune-Moriya, S.; Kondo, S.; Sugawara-Narutaki, A.; Nishimura, T.; Kato, T.; Ohtsuki, C. Hydroxyapatite formation on oxidized cellulose nanofibers in a solution mimicking body fluid. Polym. J. 2015, 47, 158–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, W.; Zhang, H.; Yin, J.; Yang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Li, J.; Yao, F. Hydroxyapatite Crystal Formation in the Presence of Polysaccharide. Cryst. Growth Des. 2016, 16, 1247–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusakabe, A.; Hirota, K.; Mizutani, T. Crystallisation of hydroxyapatite in phosphorylated poly(vinyl alcohol) as a synthetic route to tough mechanical hybrid materials. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2017, 70, 487–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diegmueller, J.J.; Cheng, X.; Akkus, O. Modulation of Hydroxyapatite Nanocrystal Size and Shape by Polyelectrolytic Peptides. Cryst. Growth Desig. 2009, 9, 5220–5226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, G. Rigid Biological Systems as Models for Synthetic Composites. Science 2005, 310, 1144–1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schweizer, S.; Taubert, A. Polymer-Controlled, Bio-Inspired Calcium Phosphate Mineralization from Aqueous Solution. Macromol. Biosci. 2007, 7, 1085–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, L.C.; Newcomb, C.J.; Kaltz, S.R.; Spoerke, E.D.; Stupp, S.I. Biomimetic Systems for Hydroxyapatite Mineralization Inspired by Bone and Enamel. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 4754–4783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munch, E.; Launey, M.E.; Alsem, D.H.; Saiz, E.; Tomsia, A.P.; Ritchie, R.O. Tough, Bio-Inspired Hybrid Materials. Science 2008, 322, 1516–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roeder, R.K.; Converse, G.L.; Kane, R.J.; Yue, W. Hydroxyapatite-Reinforced Polymer Biocomposites for Synthetic Bone Substitutes. JOM 2008, 60, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Wang, X.; Ma, J.; Huang, L. Preparation of phosphorylated chitosan/chitosan/hydroxyapatite composites by co-precipitation method. Adv. Mater. Res. 2009, 79–82, 401–404. [Google Scholar]

- Nudelman, F.; Sommerdijk, N.A.J.M. Biomineralization as an inspiration for materials chemistry. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 6582–6596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, C.Y.; Chen, J.; Zhuang, Z.; Zhang, T.; Wang, X.P.; Fang, Q.F. In situ hybridization and characterization of fibrous hydroxyapatite/chitosan nanocomposite. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2012, 124, 397–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onoki, T.; Nakahira, A.; Tago, T.; Hasegawa, Y.; Kuno, T. Novel low temperature processing techniques for apatite ceramics and chitosan polymer composite bulk materials and its mechanical properties. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2012, 262, 263–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Ning, X.; Bai, Y.; Jia, W. A scalable synthesis of non-agglomerated and low-aspect ratio hydroxyapatite nanocrystals using gelatinized starch matrix. Mater. Lett. 2013, 113, 142–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleek, K.; Taubert, A. New developments in polymer controlled, bioinspired calcium phosphate mineralization from aqueous solution. Acta Biomater. 2013, 9, 6283–6321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.; Wang, J.; Ai, X.; Zhang, S. Biomimetic self-assembly of apatite hybrid materials: From a single molecular template to bi-/multi-molecular templates. Biotechnol. Adv. 2014, 32, 744–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Won, J.-E.; El-Fiqi, A.; Jegal, S.-H.; Han, C.-M.; Lee, E.-J.; Knowles, J.C.; Kim, H.-W. Gelatin-apatite bone mimetic co-precipitates incorporated within biopolymer matrix to improve mechanical and biological properties useful for hard tissue repair. J. Biomater. Appl. 2014, 28, 1213–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Baker, B.A.; Mou, X.; Ren, N.; Qiu, J.; Boughton, R.I.; Liu, H. Biopolymer/Calcium Phosphate Scaffolds for Bone Tissue Engineering. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2014, 3, 469–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, Y.; Yin, P.; Liang, B.; Wang, H.; Guo, L. Bioinspired Design and Assembly of Layered Double Hydroxide/Poly(vinyl alcohol) Film with High Mechanical Performance. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 15154–15161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Q.; Jiang, L.; Tang, Z. Bioinspired Layered Materials with Superior Mechanical Performance. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014, 47, 1256–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegst, U.G.K.; Bai, H.; Saiz, E.; Tomsia, A.P.; Ritchie, R.O. Bioinspired structural materials. Nat. Mater. 2015, 14, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Le, H.; Natesan, K.; Pranti-Haran, S. Mechanical property and biocompatibility of co-precipitated nano hydroxyapatite-gelatine composites. J. Adv. Ceram. 2015, 4, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakir, M.; Jolly, R.; Khan, M.S.; e Iram, N.; Khan, H.M. Nano-hydroxyapatite/chitosan starch nanocomposite as a novel bone construct: Synthesis and in vitro studies. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2015, 80, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakharov, N.A.; Demina, L.I.; Aliev, A.D.; Kiselev, M.R.; Matveev, V.V.; Orlov, M.A.; Zakharova, T.V.; Kuznetsov, N.T. Synthesis and Properties of Calcium Hydroxyapatite/Silk Fibroin Organomineral Composites. Inorg. Mater. 2017, 53, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miculescu, F.; Maidaniuc, A.; Voicu, S.I.; Thakur, V.K.; Stan, G.E.; Ciocan, L.T. Progress in Hydroxyapatite. Starch Based Sustainable Biomaterials for Biomedical Bone Substitution Applications. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 8491–8512. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, R.L.; Zhu, Y.J.; Chen, F.F.; Qin, D.D.; Xiong, Z.C. Bioinspired Macroscopic Ribbon Fibers with a Nacre-Mimetic Architecture Based on Highly Ordered Alignment of Ultralong Hydroxyapatite Nanowires. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 12284–12295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zima, A. Hydroxyapatite-chitosan based bioactive hybrid biomaterials with improved mechanical strength. Spectrochim. Acta A 2018, 193, 175–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawasaki, T.; Takahashi, S.; Ikeda, K. Hydroxyapatite high-performance liquid chromatography: Column performance for proteins. Eur. J. Biochem. 1985, 152, 361–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.; Yeo, M.; Kim, M.; Kim, G. Biomimetic cellulose/calcium-deficient hydroxyapatite composite scaffolds fabricated using an electric field for bone tissue engineering. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 20637–20647. [Google Scholar]

- Malkaj, P.; Pierri, E.; Dalas, E. The crystallization of hydroxyapatite in the presence of sodium alginate. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2005, 16, 733–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingole, V.H.; Vuherer, T.; Maver, U.; Vinchurkar, A.; Ghule, A.V.; Kokol, V. Mechanical Properties and Cytotoxicity of Differently Structured Nanocellulose-hydroxyapatite Based Composites for Bone Regeneration Application. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klemm, D.; Heublein, B.; Fink, H.; Bohn, A. Cellulose: Fascinating Biopolymer and Sustainable Raw Material. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 3358–3393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schierbaum, F. The Current World Corn Situation: Production, Uses and Ending Stocks; Revised Figures for Fiscal Years 2006/07, 2007/08, Current Figures 2008/09, Production Profiles and Outlook. Starch—Stärke 2010, 62, 272–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuda, K.; Shigemasa, R.; Hirota, K.; Mizutani, T. In Situ Crystallization of Hydroxyapatite on Carboxymethyl Cellulose as a Biomimetic Approach to Biomass-Derived Composite Materials. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 12127–12137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuda, K.; Mizutani, T. Hybridization of chemically modified cellulose and hydroxyapatite for development of biomass-derived tough and water resistant structural materials. In Proceedings of the JCCM-14, Tokyo, Japan, 14–16 March 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Brandrup, J.; Immergut, E.H.; Grulke, E.A. (Eds.) Polymer Handbook, 4th ed.; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Okuda, K.; Hirota, K.; Mizutani, T.; Aoyama, Y. Co-precipitation of tapioca starch and hydroxyapatite. Effects of phosphorylation of starch on mechanical properties of the composites. Results Mater. 2019, 3, 100035. [Google Scholar]

- Okuda, K.; Mizutani, T.; Hirota, K.; Hayashi, T.; Zinno, K. Nonbrittle Nanocomposite Materials Prepared by Coprecipitation of TEMPO-Oxidized Cellulose Nanofibers and Hydroxyapatite. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 158–167. [Google Scholar]

- Okita, Y.; Saito, T.; Isogai, A. Entire Surface Oxidation of Various Cellulose Microfibrils by TEMPO-Mediated Oxidation. Biomacromolecules 2010, 11, 1696–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiner, S.; Addadi, L. Design strategies in mineralized biological materials. J. Mater. Chem. 1997, 7, 689–702. [Google Scholar]

- Okuda, K.; Aoyama, Y.; Hirota, K.; Mizutani, T. Effects of Hydration on Mechanical Properties of Acylated Hydroxyapatite-Starch Composites. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2022, 4, 1666–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okuda, K.; Kido, E.; Hirota, K.; Mizutani, T. Water-resistant Tough Composites of Cellulose Nanofibers and Hydroxyapatite. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2023, 5, 8082–8088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neuendorf, R.E.; Saiz, E.; Tomsia, A.P.; Ritchie, R.O. Adhesion between biodegradable polymers and hydroxyapatite: Relevance to synthetic bone-like materials and tissue engineering scaffolds. Acta Biomater. 2008, 4, 1288–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, P.; Malho, J.; Rahimi, K.; Schacher, F.H.; Wang, B.; Demco, D.E.; Walther, A. Nacre-mimetics with synthetic nanoclays up to ultrahigh aspect ratios. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 5967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.-C.; Zhu, Y.-J.; Xiong, Z.-C.; Lu, B.-Q. Bioinspired fiberboard-and-mortar structural nanocomposite based on ultralong hydroxyapatite nanowires with high mechanical performance. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 399, 125666. [Google Scholar]

| Ceramic-Reinforced Polymer | Polymer-Reinforced Ceramics | |

|---|---|---|

| Major component | Polymer (matrix, continuous phase) | Ceramics (filler, dispersed phase) |

| Minor component | Ceramics (filler, dispersed phase) | Polymers (matrix, continuous phase) |

| Examples | Glass–fiber reinforced plastics | Laminated glass |

| Polyamide–clay composites | Bones | |

| Tire | Teeth |

| Bending Strength, MPa | Elastic Modulus, GPa | Density, g/cm3 | Uniaxial Press Pressure, MPa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTS–HAP, HAP 70 wt% | 47 | 4.9 | 1.72 | 120 |

| CMC–HAP, HAP 70 wt% | 113 | 7.7 | 1.8 | 120 |

| TCNF–HAP, HAP 62 wt% | 80 | 11.6 | 1.94 | 300 |

| Poly(methyl methacrylate) | 118 | 3.4 | 1.19 | |

| Polyamide-6 | 118 | 2.8 | 1.14 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mizutani, T.; Okuda, Y. Bioinspired Mechanical Materials—Development of High-Toughness Ceramics through Complexation of Calcium Phosphate and Organic Polymers. Ceramics 2023, 6, 2117-2133. https://doi.org/10.3390/ceramics6040130

Mizutani T, Okuda Y. Bioinspired Mechanical Materials—Development of High-Toughness Ceramics through Complexation of Calcium Phosphate and Organic Polymers. Ceramics. 2023; 6(4):2117-2133. https://doi.org/10.3390/ceramics6040130

Chicago/Turabian StyleMizutani, Tadashi, and Yui Okuda. 2023. "Bioinspired Mechanical Materials—Development of High-Toughness Ceramics through Complexation of Calcium Phosphate and Organic Polymers" Ceramics 6, no. 4: 2117-2133. https://doi.org/10.3390/ceramics6040130

APA StyleMizutani, T., & Okuda, Y. (2023). Bioinspired Mechanical Materials—Development of High-Toughness Ceramics through Complexation of Calcium Phosphate and Organic Polymers. Ceramics, 6(4), 2117-2133. https://doi.org/10.3390/ceramics6040130