Proton Binding of Halloysite Nanotubes at Varied Ionic Strength: A Potentiometric Titration and Electrophoretic Mobility Study

Abstract

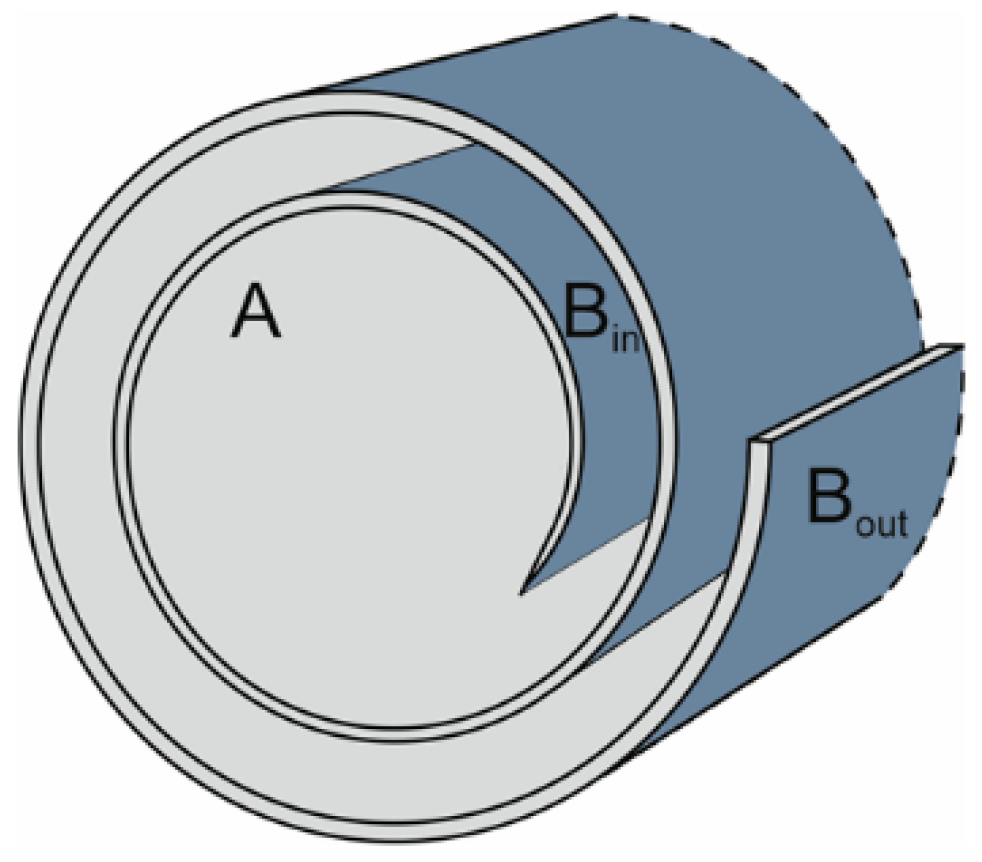

1. Introduction

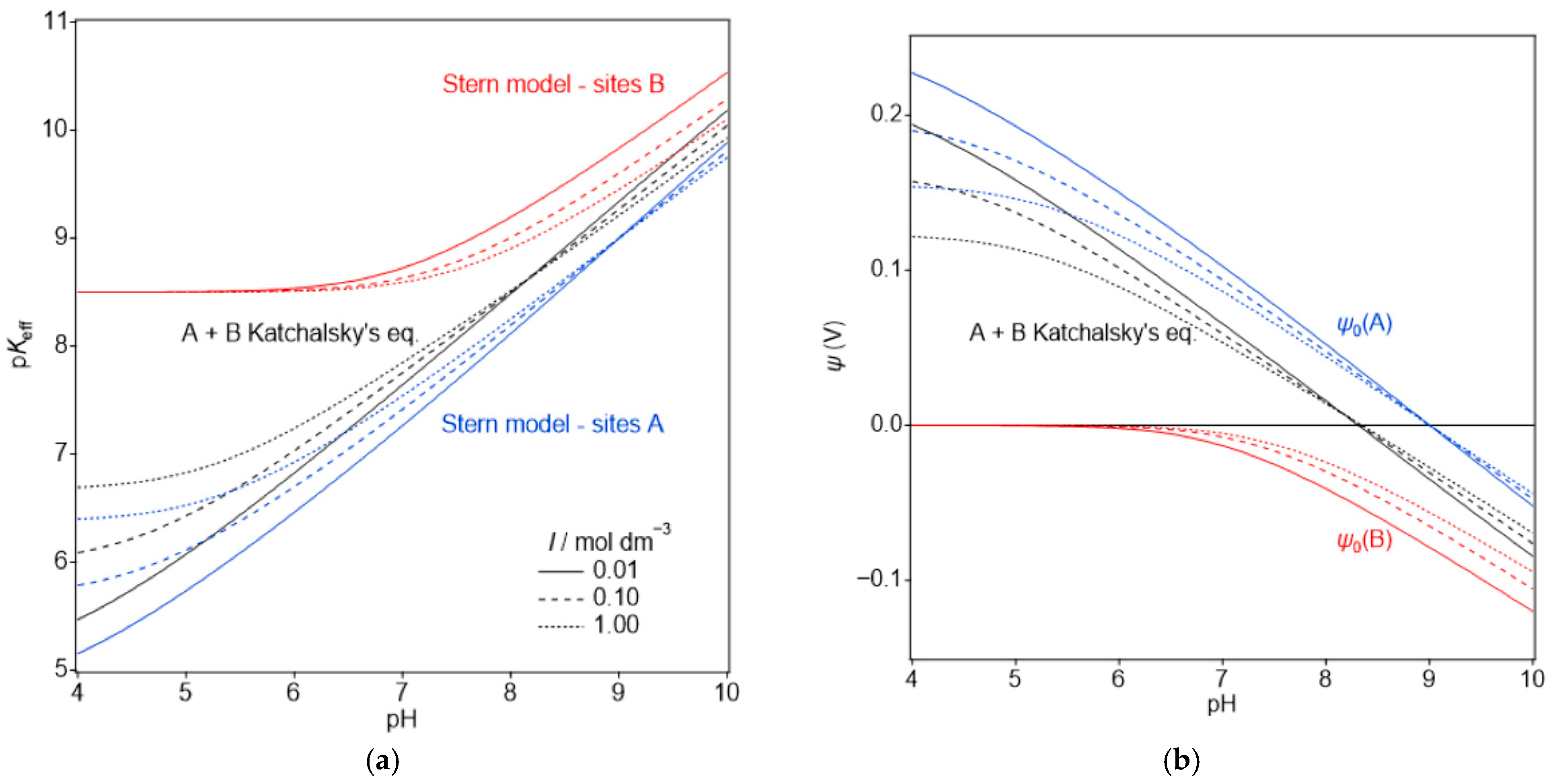

Stern Model of pH-Dependent Surface Charging

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

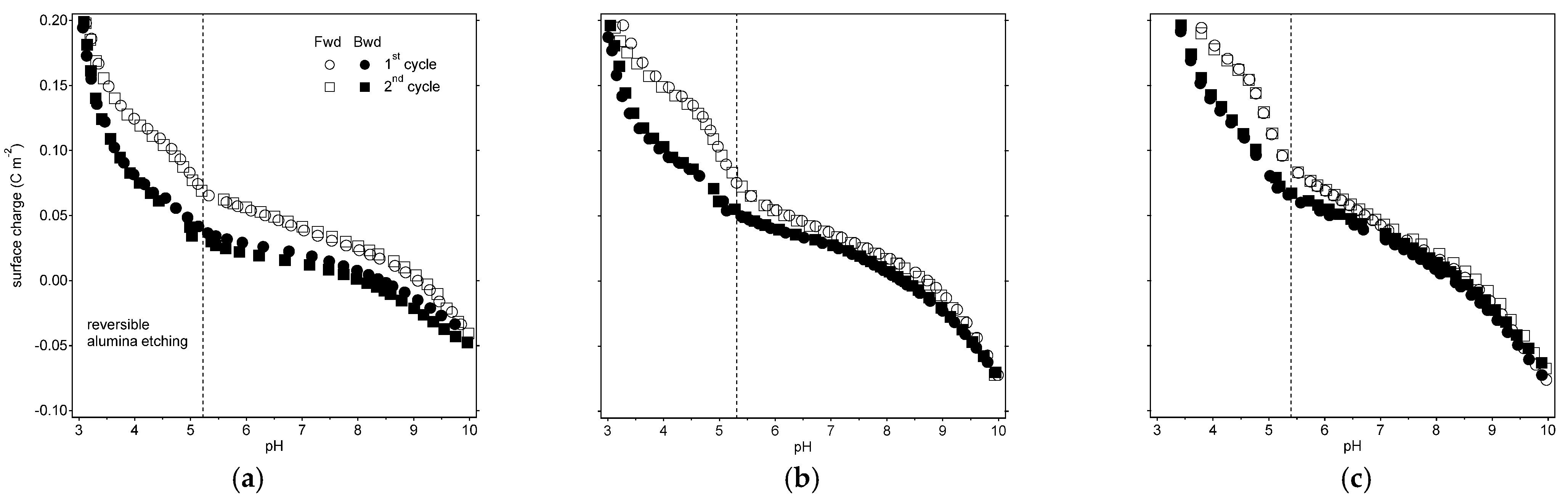

3.1. Charge Titration Reversibility: The Dissolution-Deposition of Surface Groups

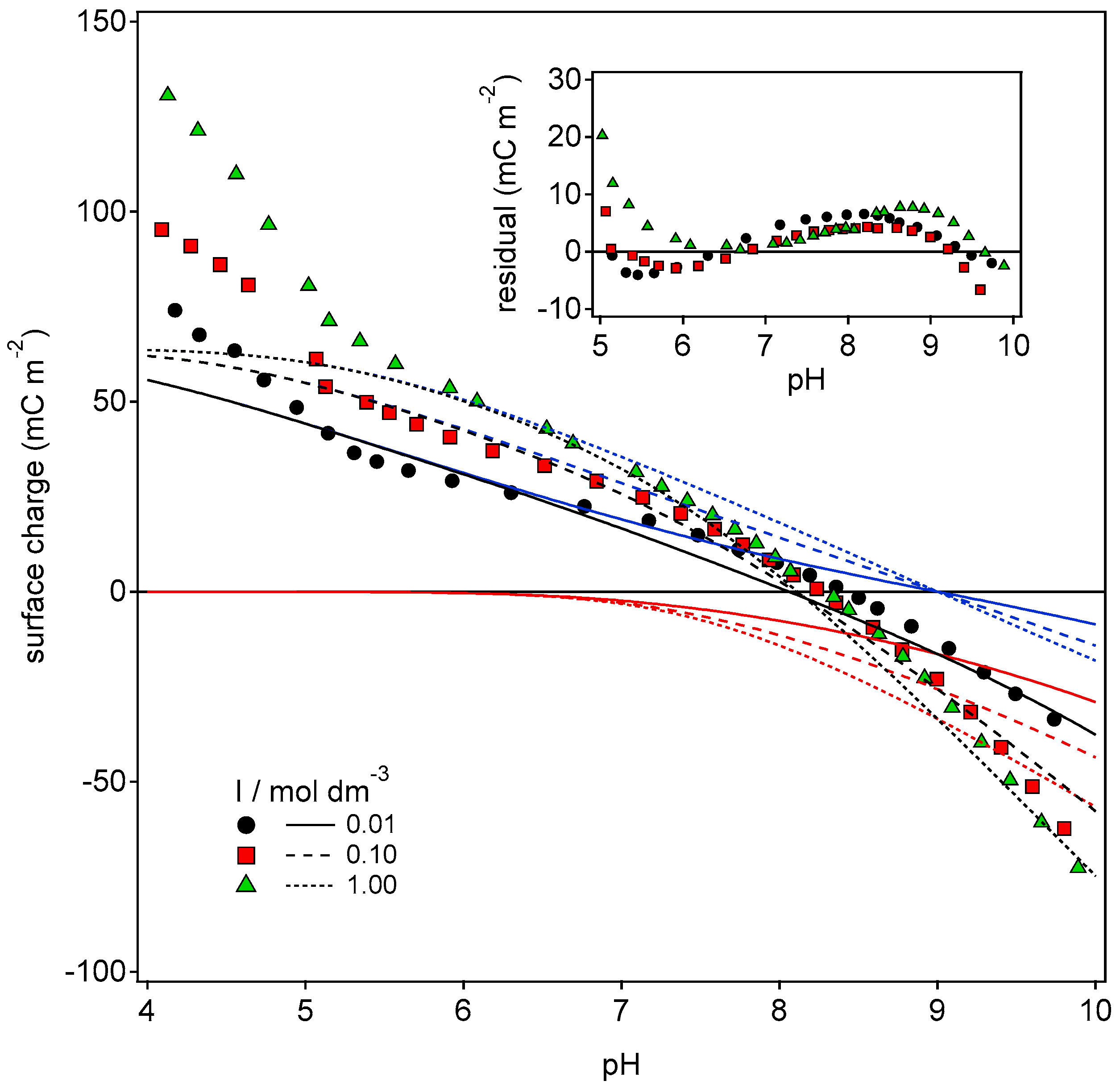

3.2. Stern Model for the HNT Interior and the Charging Mechanism of HNT Under the Quasi-Reversibility Conditions

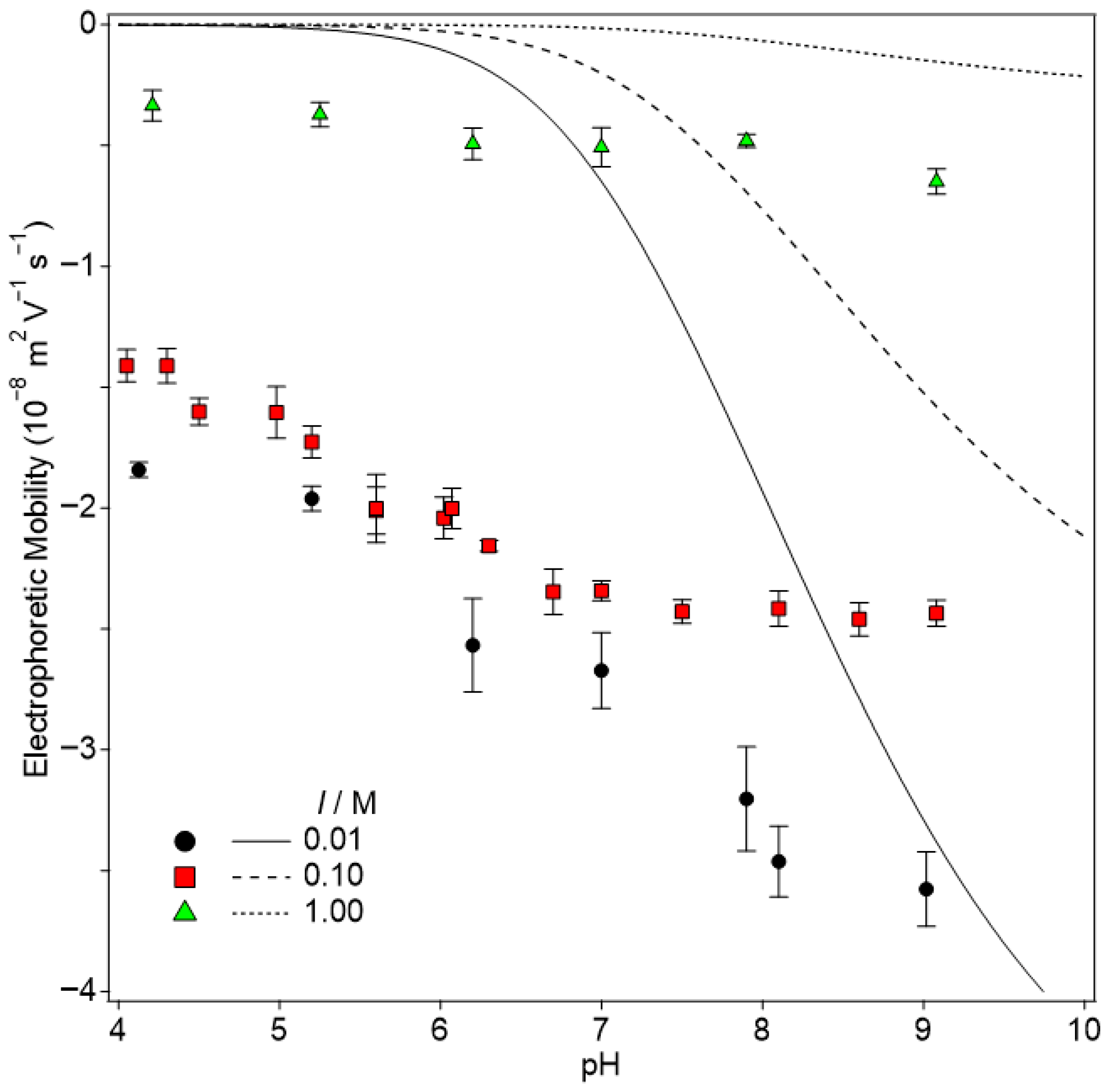

3.3. The Outer Silica Surface and Electrophoretic Mobility of the HNT

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Joussein, E.; Petit, S.; Churchman, J.; Theng, B.; Righi, D.; Delvaux, B. Halloysite Clay Minerals—A Review. Clay Min. 2005, 40, 383–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrante, F.; Armata, N.; Lazzara, G. Modeling of the Halloysite Spiral Nanotube. J. Phys. Chem. C 2015, 119, 16700–16707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gray-Wannell, N.; Cubillas, P.; Aslam, Z.; Holliman, P.J.; Greenwell, H.C.; Brydson, R.; Delbos, E.; Strachan, L.-J.; Fuller, M.; Hillier, S. Morphological Features of Halloysite Nanotubes as Revealed by Various Microsco-pies. Clay Min. 2023, 58, 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozza, R.; Ferrante, F. Computational study of water adsorption on halloysite nanotube in different pH environments. Appl. Clay Sci. 2020, 190, 105589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrante, F.; Armata, N.; Cavallaro, G.; Lazzara, G. Adsorption Studies of Molecules on the Halloysite Surfaces: A Computational and Experimental Investigation. J. Phys. Chem. C 2017, 121, 2951–2958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massaro, M.; Noto, R.; Riela, S. Past, Present and Future Perspectives on Halloysite Clay Minerals. Molecules 2020, 25, 4863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lvov, Y.; Abdullayev, E. Functional polymer–clay nanotube composites with sustained release of chemical agents. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2013, 38, 1690–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lvov, Y.M.; Shchukin, D.G.; Möhwald, H.; Price, R.R. Halloysite Clay Nanotubes for Controlled Release of Protective Agents. ACS Nano 2008, 2, 814–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergaro, V.; Lvov, Y.M.; Leporatti, S. Halloysite Clay Nanotubes for Resveratrol Delivery to Cancer Cells. Macromol. Biosci. 2012, 12, 1265–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazzara, G.; Cavallaro, G.; Panchal, A.; Fakhrullin, R.; Stavitskaya, A.; Vinokurov, V.; Lvov, Y. An assembly of organic-inorganic composites using halloysite clay nanotubes. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2018, 35, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massaro, M.; Amorati, R.; Cavallaro, G.; Guernelli, S.; Lazzara, G.; Milioto, S.; Noto, R.; Poma, P.; Riela, S. Direct chemical grafted curcumin on halloysite nanotubes as dual-responsive prodrug for pharmacological applications. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2016, 140, 505–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hári, J.; Sárközi, M.; Földes, E.; Pukánszky, B. Long term stabilization of PE by the controlled release of a natural antioxidant from halloysite nanotubes. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2018, 147, 229–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katana, B.; Rouster, P.; Varga, G.; Muráth, S.; Glinel, K.; Jonas, A.M.; Szilagyi, I. Self-Assembly of Protamine Biomacromolecule on Halloysite Nanotubes for Immobilization of Superoxide Dismutase Enzyme. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2019, 3, 522–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lvov, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhang, L.; Fakhrullin, R. Halloysite Clay Nanotubes for Loading and Sustained Release of Functional Compounds. Adv. Mater. 2016, 28, 1227–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, A.C.; Ferreira, C.; Veiga, F.; Ribeiro, A.J.; Panchal, A.; Lvov, Y.; Agarwal, A. Halloysite clay nanotubes for life sciences applications: From drug encapsulation to bioscaffold. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2018, 257, 58–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavallaro, G.; Lazzara, G.; Milioto, S. Exploiting the Colloidal Stability and Solubilization Ability of Clay Nanotubes/Ionic Surfactant Hybrid Nanomaterials. J. Phys. Chem. C 2012, 116, 21932–21938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tombácz, E.; Szekeres, M. Interfacial Acid−Base Reactions of Aluminum Oxide Dispersed in Aqueous Electrolyte Solutions. 1. Potentiometric Study on the Effect of Impurity and Dissolution of Solid Phase. Langmuir 2001, 17, 1411–1419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll-Webb, S.A.; Walther, J.V. A surface complex reaction model for the pH-dependence of corundum and kaolinite dissolution rates. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1988, 52, 2609–2623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katana, B.; Takács, D.; Szerlauth, A.; Sáringer, S.; Varga, G.; Jamnik, A.; Bobbink, F.D.; Dyson, P.J.; Szilagyi, I. Aggregation of Halloysite Nanotubes in the Presence of Multivalent Ions and Ionic Liquids. Langmuir 2021, 37, 11869–11879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katana, B.; Takács, D.; Csapó, E.; Szabó, T.; Jamnik, A.; Szilagyi, I. Ion Specific Effects on the Stability of Halloysite Nanotube Colloids—Inorganic Salts versus Ionic Liquids. J. Phys. Chem. B 2020, 124, 9757–9765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasbakhsh, P.; Churchman, G.J.; Keeling, J.L. Characterisation of properties of various halloysites relevant to their use as nanotubes and microfibre fillers. Appl. Clay Sci. 2013, 74, 47–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borkovec, M.; Jönsson, B.; Koper, G.J.M. Ionization Processes and Proton Binding in Polyprotic Systems: Small Molecules, Proteins, Interfaces, and Polyelectrolytes. In Surface and Colloid Science; Matijević, E., Ed.; Springer: Boston, MA, USA, 2001; Volume 16, pp. 99–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hesleitner, P.; Babic, D.; Kallay, N.; Matijevic, E. Adsorption at solid/solution interfaces. 3. Surface charge and potential of colloidal hematite. Langmuir 1987, 3, 815–820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bretti, C.; Cataldo, S.; Gianguzza, A.; Lando, G.; Lazzara, G.; Pettignano, A.; Sammartano, S. Thermodynamics of Proton Binding of Halloysite Nanotubes. J. Phys. Chem. C 2016, 120, 7849–7859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kallay, N.; Čakara, D. Reversible Charging of the Ice–Water Interface. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2000, 232, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, D.F.; Wennerström, H. Colloidal Domain; Wiley-Vch: Weinheim, Germany, 1999; ISBN 0471242470. [Google Scholar]

- Israelachvili, J.N. Intermolecular and Surface Forces; Academic Press: Oxford, UK, 2011; ISBN 0123919339. [Google Scholar]

- Kallay, N.; Dojnović, Z.; Čop, A. Surface potential at the hematite–water interface. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2005, 286, 610–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blesa, M.A.; Kallay, N. The metal oxide—Electrolyte solution interface revisited. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 1987, 28, 111–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rouster, P.; Dondelinger, M.; Galleni, M.; Nysten, B.; Jonas, A.M.; Glinel, K. Layer-by-layer assembly of enzyme-loaded halloysite nanotubes for the fabrication of highly active coatings. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2019, 178, 508–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, S.; Reyes, C.; Liu, J.; Rodgers, P.A.; Wentworth, S.H.; Sun, L. Facile Hydroxylation of Halloysite Nano-tubes for Epoxy Nanocomposite Applications. Polymer 2014, 55, 6519–6528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čakara, D. Charging Behavior of Polyamines in Solution and on Surfaces: A Potentiometric Titration Study. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Thommes, M.; Kaneko, K.; Neimark, A.V.; Olivier, J.P.; Rodriguez-Reinoso, F.; Rouquerol, J.; Sing, K.S.W. Physisorption of gases, with special reference to the evaluation of surface area and pore size distribution (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 2015, 87, 1051–1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, M.; Skarba, M.; Galletto, P.; Cakara, D.; Borkovec, M. Effects of Heat Treatment on the Aggrega-tion and Charging of Stöber-Type Silica. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2005, 292, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yates, D.E.; Healy, T.W. The structure of the silica/electrolyte interface. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1976, 55, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pourbaix, M. Atlas of Electrochemical Equilibria in Aqueous Solutions, 2nd ed.; National Association of Corrosion Engineers: Houston, TX, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Wieland, E.; Stumm, W. Dissolution kinetics of kaolinite in acidic aqueous solutions at 25 °C. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 1992, 56, 3339–3355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullayev, E.; Joshi, A.; Wei, W.; Zhao, Y.; Lvov, Y. Enlargement of Halloysite Clay Nanotube Lumen by Se-lective Etching of Aluminum Oxide. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 7216–7226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wells, J.D.; Koopal, L.K.; de Keizer, A. Monodisperse, Nonporous, Spherical Silica Particles. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2000, 166, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrens, S.H.; Borkovec, M.; Schurtenberger, P. Aggregation in Charge-Stabilized Colloidal Suspensions Re-visited. Langmuir 1998, 14, 1951–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trefalt, G.; Behrens, S.H.; Borkovec, M. Charge Regulation in the Electrical Double Layer: Ion Adsorption and Surface Interactions. Langmuir 2015, 32, 380–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrens, S.H.; Christl, D.I.; Emmerzael, R.; Schurtenberger, P.; Borkovec, M. Charging and Aggregation Properties of Carboxyl Latex Particles: Experiments versus DLVO Theory. Langmuir 2000, 16, 2566–2575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schudel, M.; Behrens, S.; Holthoff, H.; Kretzschmar, R.; Borkovec, M. Absolute Aggregation Rate Constants of Hematite Particles in Aqueous Suspensions: A Comparison of Two Different Surface Morphologies. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 1997, 196, 241–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’BRien, R.W.; White, L.R. Electrophoretic mobility of a spherical colloidal particle. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 2 1978, 74, 1607–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katana, B.; Takács, D.; Bobbink, F.D.; Dyson, P.J.; Alsharif, N.B.; Tomšič, M.; Szilagyi, I. Masking specific effects of ionic liquid constituents at the solid–liquid interface by surface functionalization. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2020, 22, 24764–24770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Surface Sites | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| A (alumina) | 0.8 | 9.00 | 0.5 |

| B (silica) | 8.50 | 0.8 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Katana, B.; Čakara, D. Proton Binding of Halloysite Nanotubes at Varied Ionic Strength: A Potentiometric Titration and Electrophoretic Mobility Study. Colloids Interfaces 2025, 9, 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/colloids9060079

Katana B, Čakara D. Proton Binding of Halloysite Nanotubes at Varied Ionic Strength: A Potentiometric Titration and Electrophoretic Mobility Study. Colloids and Interfaces. 2025; 9(6):79. https://doi.org/10.3390/colloids9060079

Chicago/Turabian StyleKatana, Bojana, and Duško Čakara. 2025. "Proton Binding of Halloysite Nanotubes at Varied Ionic Strength: A Potentiometric Titration and Electrophoretic Mobility Study" Colloids and Interfaces 9, no. 6: 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/colloids9060079

APA StyleKatana, B., & Čakara, D. (2025). Proton Binding of Halloysite Nanotubes at Varied Ionic Strength: A Potentiometric Titration and Electrophoretic Mobility Study. Colloids and Interfaces, 9(6), 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/colloids9060079