Fabricating Partial Acylglycerols for Food Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

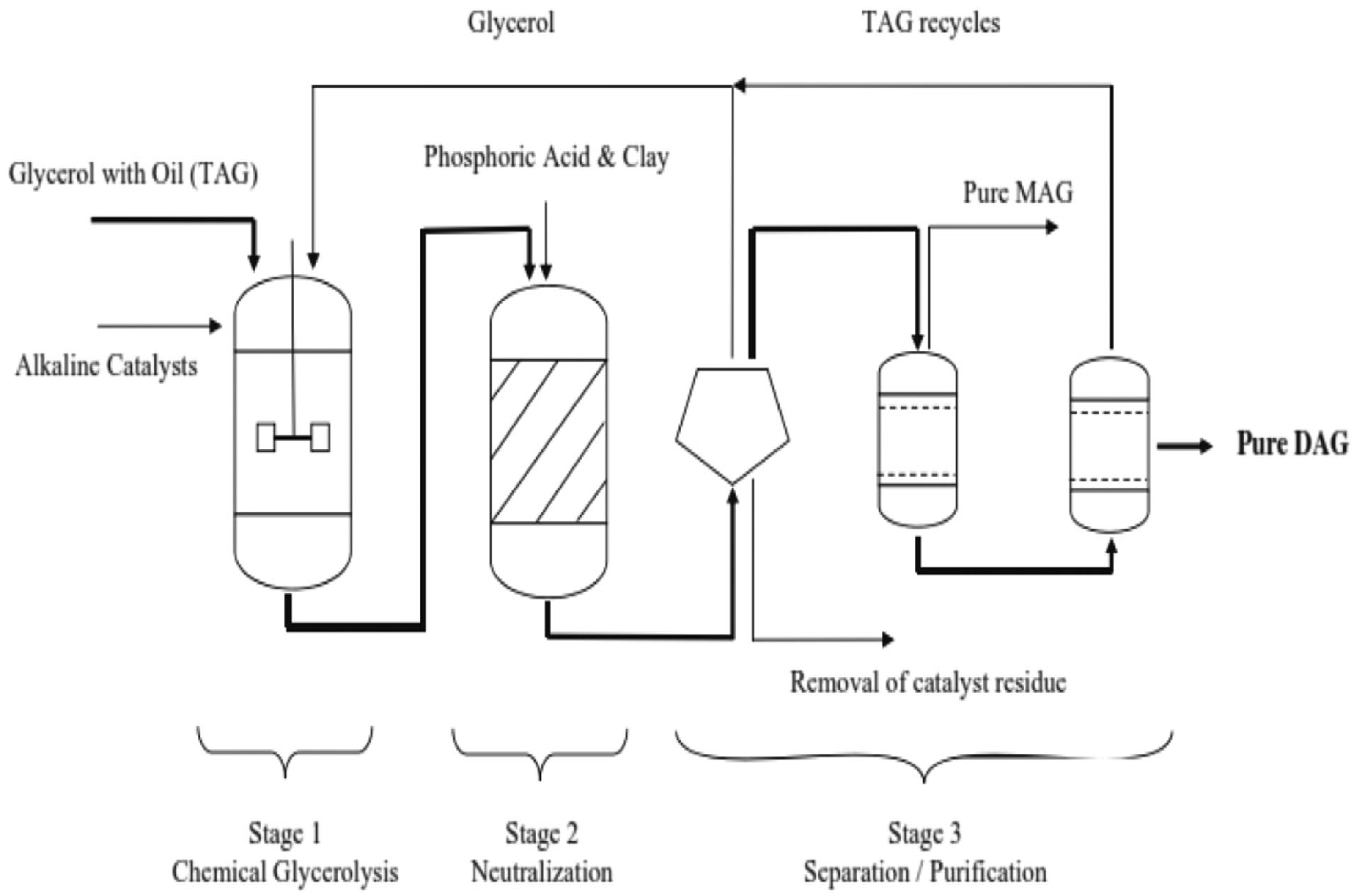

2. Comparative Assessment of Chemical and Enzymatic Routes for the Synthesis of PAs

3. Functionalities of PA for Food Applications

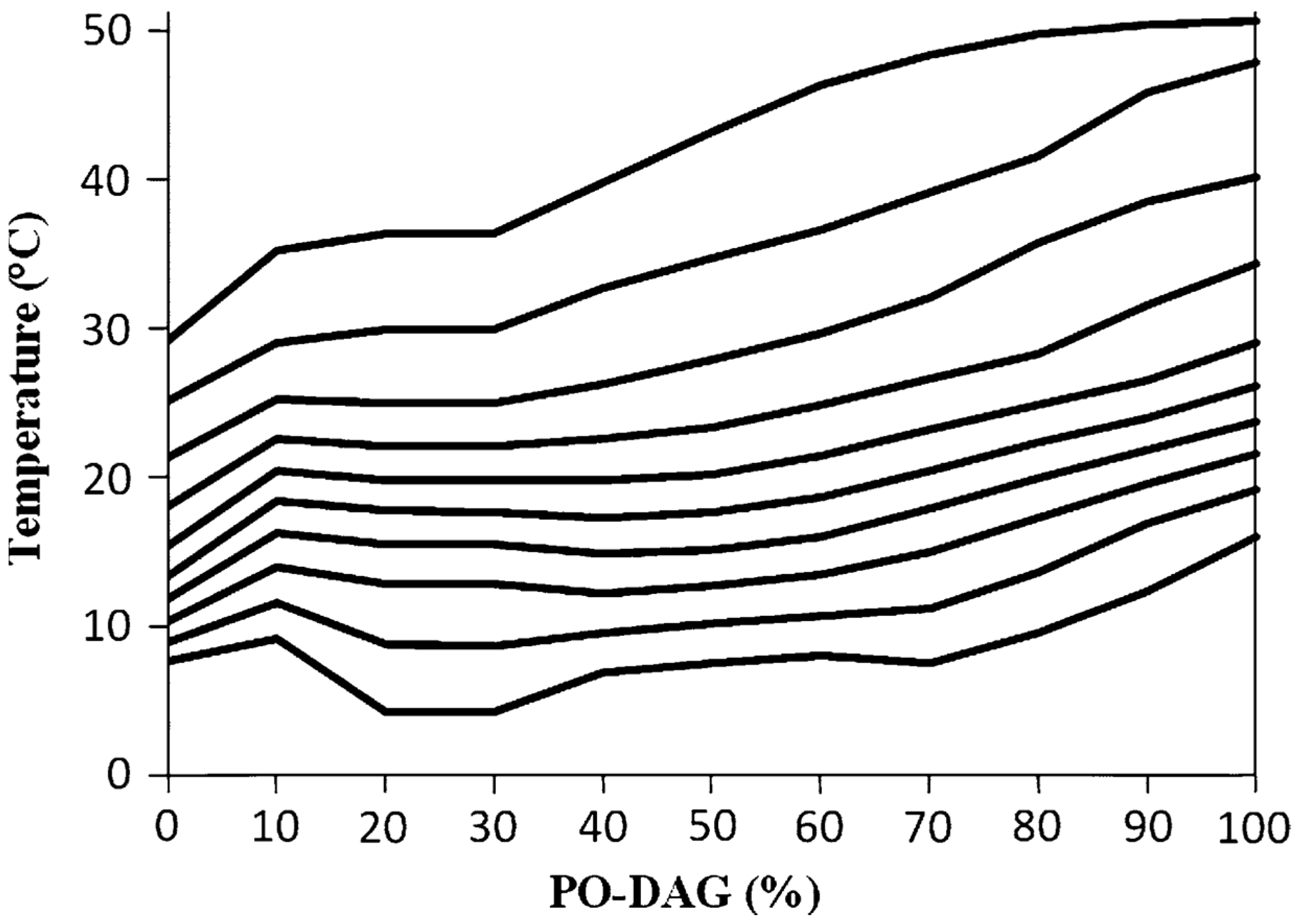

3.1. Solid Fat Content and Polymorphism of PA

3.2. Rheological Characteristics

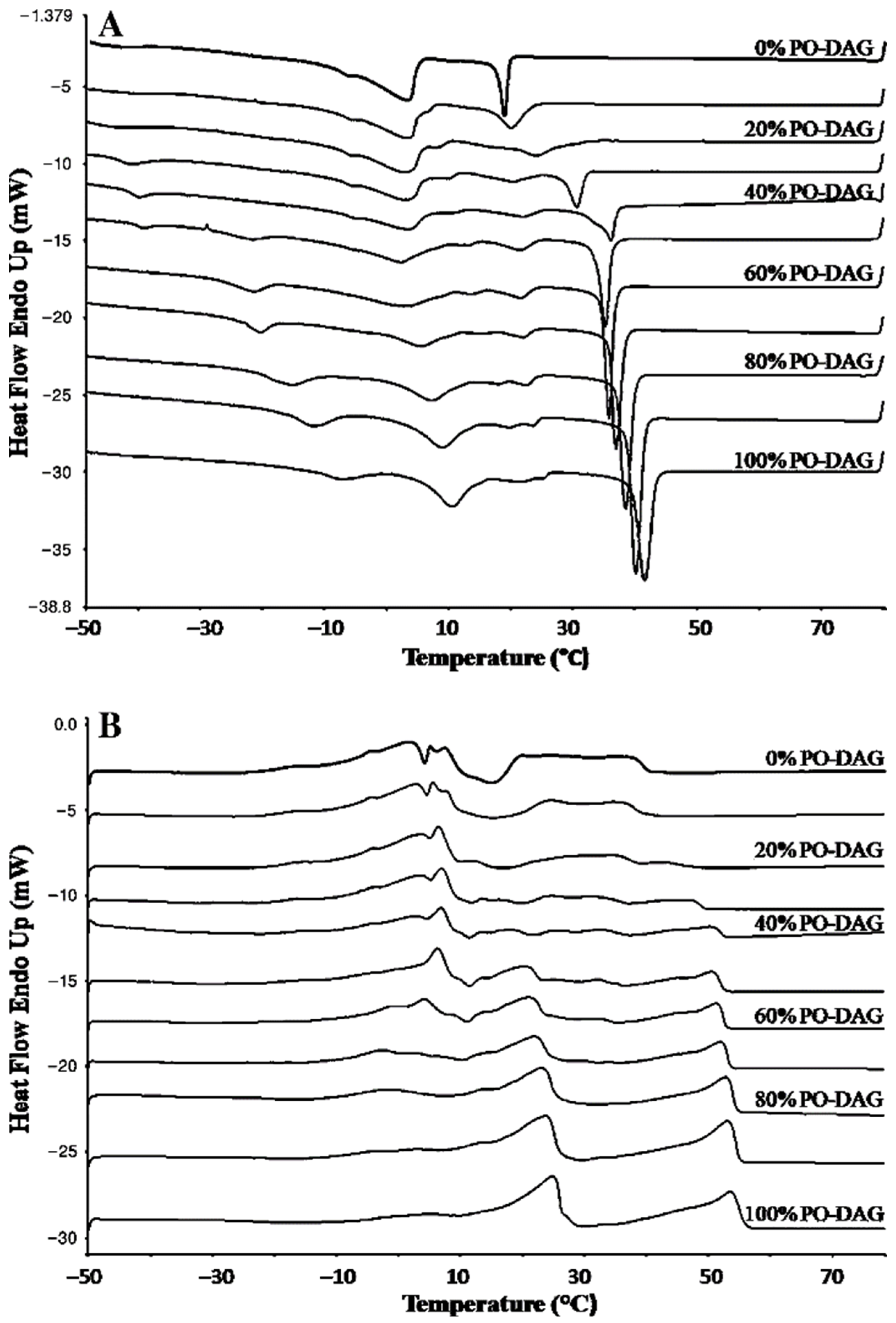

3.3. Melting Characteristics

3.4. Microstructural Morphology

4. Food Application of PA

4.1. Cooking/Frying Medium

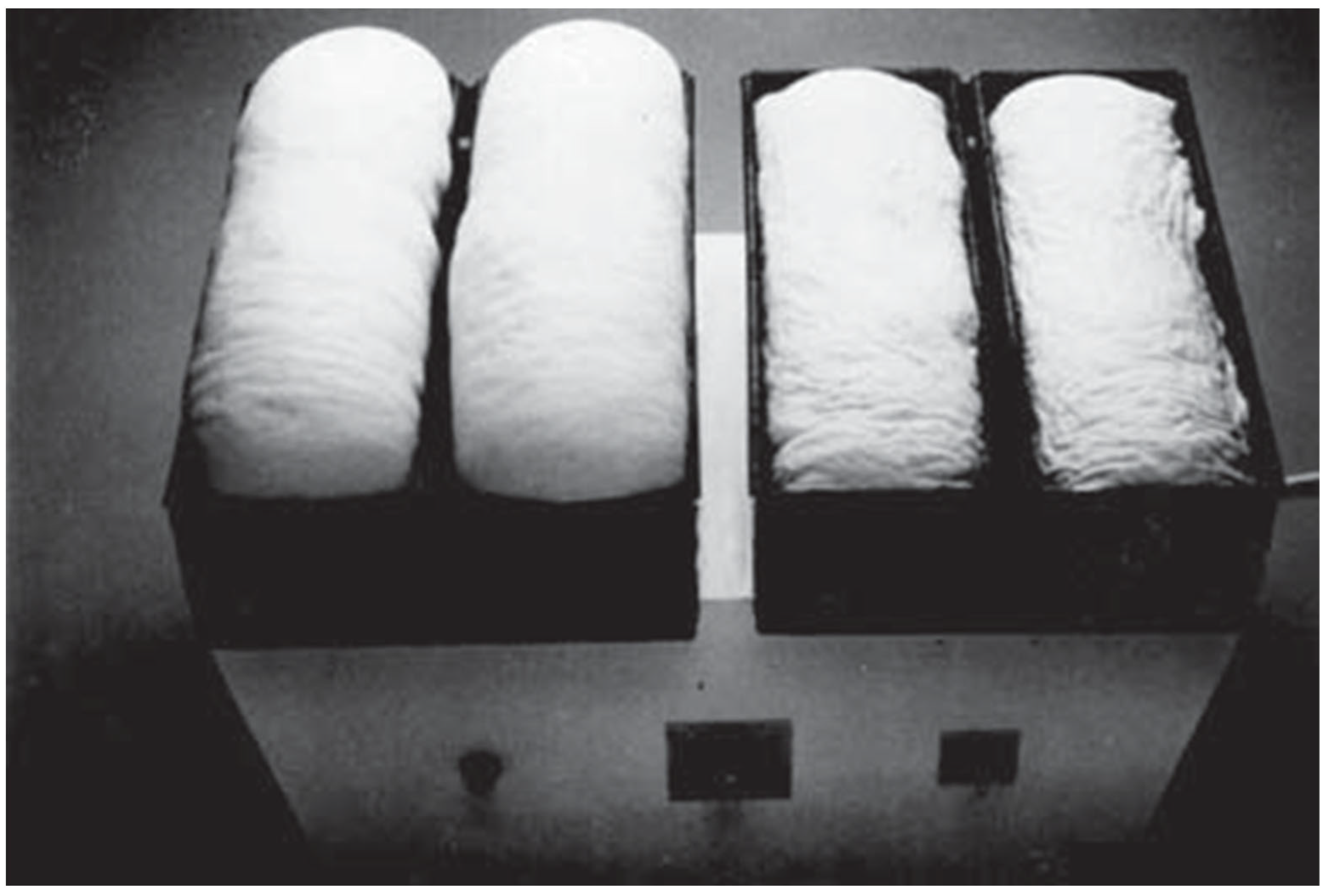

4.2. Bakery Fat

4.3. Margarine

4.4. Dairy Products

4.5. Food Emulsion

5. Technological Challenges and Probable Solutions for the Use of PA in Food Products

6. Concluding Remark and Future Prospect

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ghouila, Z.; Sehailia, M.; Chemat, S. Vegetable Oils and Fats: Extraction, Composition and Applications; Springer: Singapore, 2019; ISBN 9789811338106. [Google Scholar]

- Flickinger, B.D.; Matsuo, N. Nutritional characteristics of DAG oil. Lipids 2003, 38, 129–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taguchi, H.; Watanabe, H.; Onizawa, K.; Nagao, T.; Gotoh, N.; Yasukawa, T.; Tsushima, R.; Shimasaki, H.; Itakura, H. Double-blind controlled study on the effects of dietary diacylglycerol on postprandial serum and chylomicron triacylglycerol responses in healthy humans. J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 2000, 19, 789–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.P.; Khor, Y.P.; Lim, H.K.; Lai, O.M.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Cheong, L.Z.; Nehdi, I.A.; Mansour, L.; Tan, C.P. Fabrication of concentrated palm olein-based diacylglycerol oil-soybean oil blend oil-in-water emulsion: In-depth study of the rheological properties and storage stability. Foods 2020, 9, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, S.P.; Khor, Y.P.; Lim, H.K.; Lai, O.M.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Tan, C.P. Improved thermal properties and flow behavior of palm olein-based diacylglycerol: Impact of sucrose stearate incorporation. Processes 2021, 9, 604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palacios, D.; Busto, M.D.; Albillos, S.M.; Ortega, N. Synthesis and oxidative stability of monoacylglycerols containing polyunsaturated fatty acids by enzymatic glycerolysis in a solvent-free system. LWT 2022, 154, 112600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saberi, A.H.; Lai, O.M.; Miskandar, M.S. Melting and Solidification Properties of Palm-Based Diacylglycerol, Palm Kernel Olein, and Sunflower Oil in the Preparation of Palm-Based Diacylglycerol-Enriched Soft Tub Margarine. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2012, 5, 1674–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Q.; Peng, Z.; Dong, C. Thermal profiles, crystallization behaviors and microstructure of diacylglycerol-enriched palm oil blends with diacylglycerol-enriched palm olein. Food Chem. 2016, 202, 364–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, H.B.; Annapure, U. Designer lipids-synthesis and application—A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 116, 884–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.Y.; Tang, T.K.; Chan, E.S.; Phuah, E.T.; Lai, O.M.; Tan, C.P.; Wang, Y.; Ab Karim, N.A.; Mat Dian, N.H.; Tan, J.S. Medium chain triglyceride and medium-and long chain triglyceride: Metabolism, production, health impacts and its applications—A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2021, 62, 4169–4185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latip, R.A.; Lee, Y.Y.; Tang, T.K.; Phuah, E.T.; Tan, C.P.; Lai, O.M. Physicochemical properties and crystallisation behaviour of bakery shortening produced from stearin fraction of palm-based diacyglycerol blended with various vegetable oils. Food Chem. 2013, 141, 3938–3946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Martínez, A.; Charó-Alonso, M.A.; Marangoni, A.G.; Toro-Vazquez, J.F. Monoglyceride organogels developed in vegetable oil with and without ethylcellulose. Food Res. Int. 2015, 72, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, S.; Lin, D. Monoglycerides: Categories, Structures, Properties, Preparations, and Applications in the Food industry; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; ISBN 9780128140451. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson, R.A.; Marangoni, A.G. Diglycerides. Encycl. Food Chem. 2018, 1, 70–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, H.; Waghmare, J.; Annapure, U. Effect of mono and diglyceride of medium chain fatty acid on the stability of flavour emulsion. Food Res. 2021, 5, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, H.B.; Gogate, P.; Annapure, U. Studies on Chemical and Physical Stability of Mayonnaise Prepared from Enzymatically Interesterified Corn Oil-Based Designer Lipids. ACS Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 2, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, D.; Block, R.; Mousa, S.A. Omega-3 fatty acids EPA and DHA: Health benefits throughout life. Adv. Nutr. 2012, 3, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, H.B.; Annapure, U.S. Triglycerides of medium-chain fatty acids: A concise review. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 60, 2143–2152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichmann, T.O.; Lass, A. DAG tales: The multiple faces of diacylglycerol—Stereochemistry, metabolism, and signaling. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2015, 72, 3931–3952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satriana; Arpi, N.; Lubis, Y.M.; Adisalamun; Supardan, M.D.; Mustapha, W.A.W. Diacylglycerol-enriched oil production using chemical glycerolysis. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2016, 118, 1880–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feltes, M.M.C.; de Oliveira, D.; Block, J.M.; Ninow, J.L. The Production, Benefits, and Applications of Monoacylglycerols and Diacylglycerols of Nutritional Interest. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2013, 6, 17–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.J.; Zhang, Z.; Lai, O.M.; Tan, C.P.; Wang, Y. Diacylglycerol in food industry: Synthesis methods, functionalities, health benefits, potential risks and drawbacks. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 97, 114–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rarokar, N.R.; Menghani, S.; Kerzare, D.; Khedekar, P.B. Progress in Synthesis of Monoglycerides for Use in Food and Pharmaceuticals. J. Exp. Food Chem. 2017, 3, 1000128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saberi, A.H.; Tan, C.P.; Lai, O.M. Phase behavior of palm oil in blends with palm-based diacylglycerol. JAOCS J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2011, 88, 1857–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naderi, M.; Farmani, J.; Rashidi, L. Physicochemical and Rheological Properties and Microstructure of Canola oil as Affected by Monoacylglycerols. Nutr. Food Sci. Res. 2018, 5, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basso, R.C.; Ribeiro, A.P.B.; Masuchi, M.H.; Gioielli, L.A.; Gonçalves, L.A.G.; dos Santos, A.O.; Cardoso, L.P.; Grimaldi, R. Tripalmitin and monoacylglycerols as modifiers in the crystallisation of palm oil. Food Chem. 2010, 122, 1185–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfutimie, A.; Al-Janabi, N.; Curtis, R.; Tiddy, G.J.T. The Effect of monoglycerides on the crystallisation of triglyceride. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2016, 494, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakerardekani, A.; Karim, R.; Ghazali, H.M.; Chin, N.L. The effect of monoglyceride addition on the rheological properties of pistachio spread. JAOCS J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2013, 90, 1517–1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha-Amador, O.G.; Gallegos-Infante, J.A.; Huang, Q.; Rocha-Guzman, N.E.; Rociomoreno-Jimenez, M.; Gonzalez-Laredo, R.F. Influence of commercial saturated monoglyceride, mono-/diglycerides mixtures, vegetable oil, stirring speed, and temperature on the physical properties of organogels. Int. J. Food Sci. 2014, 2014, 513641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maruyama, J.M.; Soares, F.A.S.D.M.; D’Agostinho, N.R.; Gonçalves, M.I.A.; Gioielli, L.A.; Da Silva, R.C. Effects of emulsifier addition on the crystallization and melting behavior of palm olein and coconut oil. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 2253–2263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morita, O.; Soni, M.G. Safety assessment of diacylglycerol oil as an edible oil: A review of the published literature. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2009, 47, 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaheen, S.; Kamal, M.; Zhao, C.; Farag, M.A. Fat substitutes and low-calorie fats: A compile of their chemical, nutritional, metabolic and functional properties. Food Rev. Int. 2022, 39, 5501–5527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.-H.; Terentjev, E.M. Monoglycerides in Oils. In Edible Oleogels; AOCS Press: Champaign, IL, USA, 2018; pp. 103–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohno, Y. Deep frying oil properties of diacylglycerol rich cooking oil. J. Oleo Sci. 2002, 51, 275–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimizu, M.; Moriwaki, J.; Nishide, T.; Nakajima, Y. Thermal deterioration of diacylglycerol and triacylglycerol oils during deep-frying. JAOCS J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2004, 81, 571–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katsuta, I.; Shimizu, M.; Yamaguchi, T.; Nakajima, Y. Emission of volatile aldehydes from DAG-rich and TAG-rich oils with different degrees of unsaturation during deep-frying. JAOCS J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2008, 85, 513–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.J.; Khor, Y.P.; Kadir, N.S.A.; Lan, D.; Wang, Y.; Tan, C.P. Deep-fat Frying Using Soybean Oil-based Diacylglycerol-Palm Olein Oil Blends: Thermo-oxidative Stability, 3-MCPDE and Glycidyl Ester Formation. J. Oleo Sci. 2023, 72, 533–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jadhav, H.B.; Pratap, A.P.; Gogate, P.R.; Annapure, U.S. Ultrasound-assisted synthesis of highly stable MCT based oleogel and evaluation of its baking performance. Appl. Food Res. 2022, 2, 100156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, L.Z.; Tan, C.P.; Long, K.; Idris, N.A.; Yusoff, M.S.A.; Lai, O.M. Baking performance of palm diacylglycerol bakery fats and sensory evaluation of baked products. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2011, 113, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheong, L.Z.; Tan, C.P.; Long, K.; Suria Affandi Yusoff, M.; Lai, O.M. Physicochemical, textural and viscoelastic properties of palm diacylglycerol bakery margarine during storage. JAOCS J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2009, 86, 723–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granger, C.; Barey, P.; Combe, N.; Veschambre, P.; Cansell, M. Influence of the fat characteristics on the physicochemical behavior of oil-in-water emulsions based on milk proteins-glycerol esters mixtures. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2003, 32, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moonen, H.; Bas, H. Mono and Diglycerides. In Emulsifiers in Food Technology, 2nd ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015; Volume 1, pp. 73–91. ISBN 9781118921265. [Google Scholar]

- Cropper, S.L.; Kocaoglu-Vurma, N.A.; Tharp, B.W.; Harper, W.J. Effects of locust bean gum and mono- and diglyceride concentrations on particle size and melting rates of ice cream. J. Food Sci. 2013, 78, 811–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loi, C.C.; Eyres, G.T.; Birch, E.J. Effect of mono- and diglycerides on physical properties and stability of a protein-stabilised oil-in-water emulsion. J. Food Eng. 2019, 240, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakajima, Y. Water-retaining ability of diacylglycerol. JAOCS J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2004, 81, 907–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, S. Characterization of diacylglycerol oil mayonnaise emulsified using phospholipase A2-treated egg yolk. JAOCS J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2004, 81, 993–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, S.K.; Tan, C.P.; Long, K.; Yusoff, M.S.A.; Lai, O.M. Diacylglycerol oil-properties, processes and products: A review. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2008, 1, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, J.B.; Nielsen, N.S.; Jacobsen, C.; Mu, H. Oxidative stability of diacylglycerol oil and butter blends containing diacylglycerols. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2006, 108, 336–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Mcclements, D.J.; Decker, E.A. Impact of diacylglycerol and monoacylglycerol on the physical and chemical properties of stripped soybean oil. Food Chem. 2014, 142, 365–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.M.; Kimura, F.; Endo, Y.; Maruyama, C.; Fujimoto, K. Deterioration of diacylglycerol- and triacylglycerol-rich oils during frying of potatoes. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2005, 107, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šmidrkal, J.; Tesařová, M.; Hrádková, I.; Berčíková, M.; Adamčíková, A.; Filip, V. Mechanism of formation of 3-chloropropan-1,2-diol (3-MCPD) esters under conditions of the vegetable oil refining. Food Chem. 2016, 211, 124–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jadhav, H.B.; Kumar, D.; Casanova, F. Fabricating Partial Acylglycerols for Food Applications. Colloids Interfaces 2025, 9, 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/colloids9060080

Jadhav HB, Kumar D, Casanova F. Fabricating Partial Acylglycerols for Food Applications. Colloids and Interfaces. 2025; 9(6):80. https://doi.org/10.3390/colloids9060080

Chicago/Turabian StyleJadhav, Harsh B., Dheeraj Kumar, and Federico Casanova. 2025. "Fabricating Partial Acylglycerols for Food Applications" Colloids and Interfaces 9, no. 6: 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/colloids9060080

APA StyleJadhav, H. B., Kumar, D., & Casanova, F. (2025). Fabricating Partial Acylglycerols for Food Applications. Colloids and Interfaces, 9(6), 80. https://doi.org/10.3390/colloids9060080