Interlaced Laser Beam Scanning: A Method Enabling an Increase in the Throughput of Ultrafast Laser Machining of Borosilicate Glass

Abstract

1. Introduction

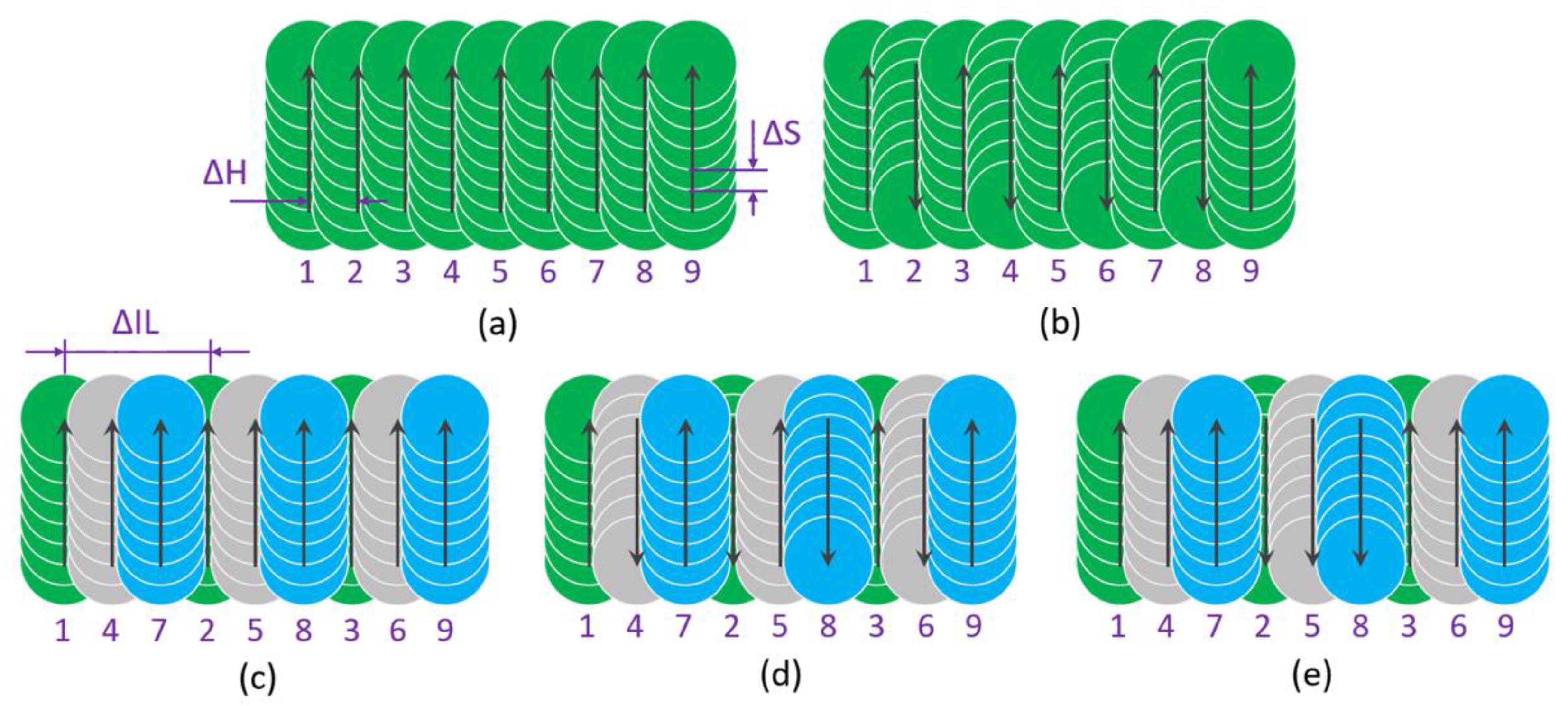

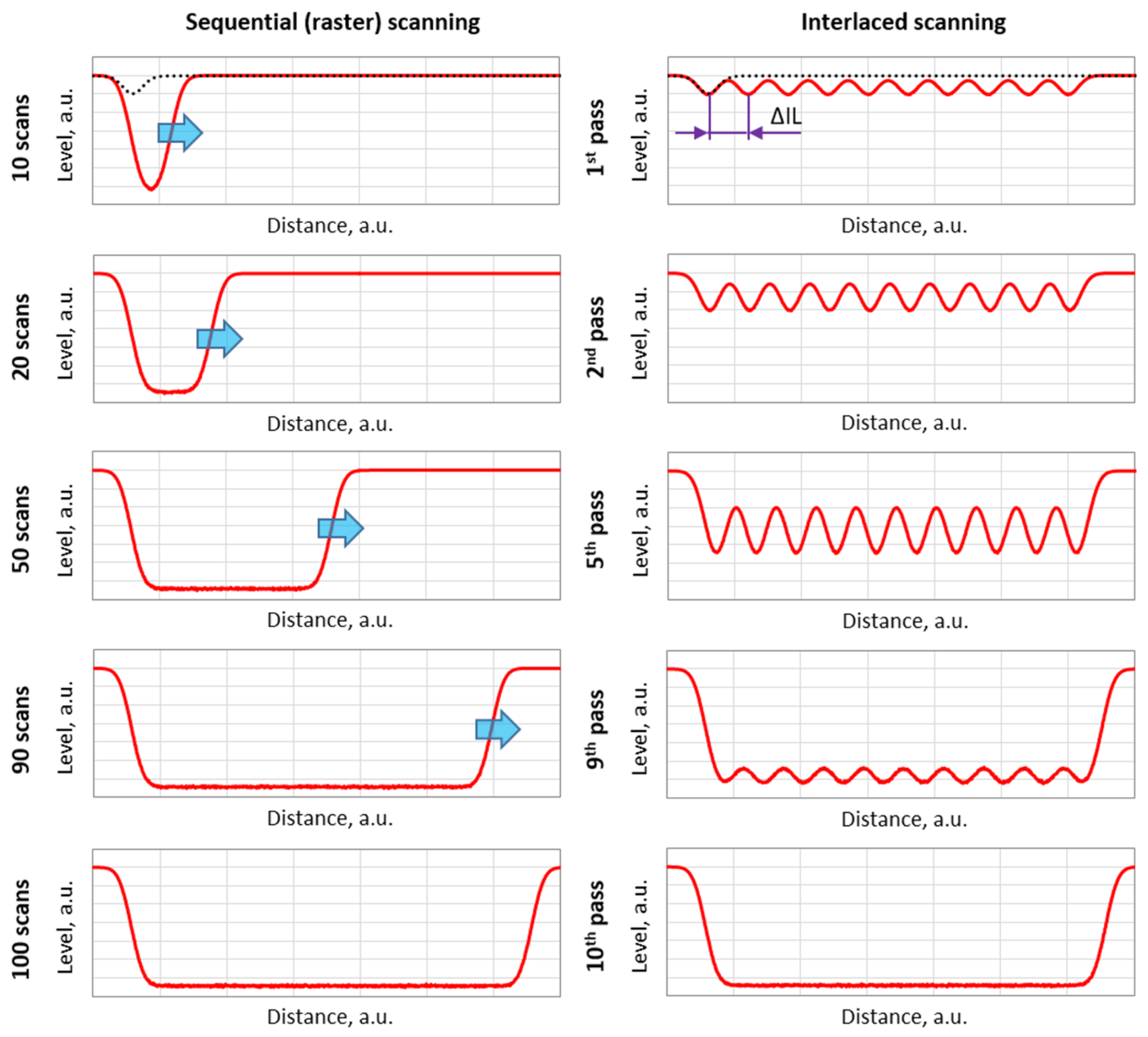

2. Interlaced Scanning Method

3. Methodology

3.1. Laser Set-Up

3.2. Laser Machining Procedure

3.3. Post-Process Cleaning

3.4. Sample Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

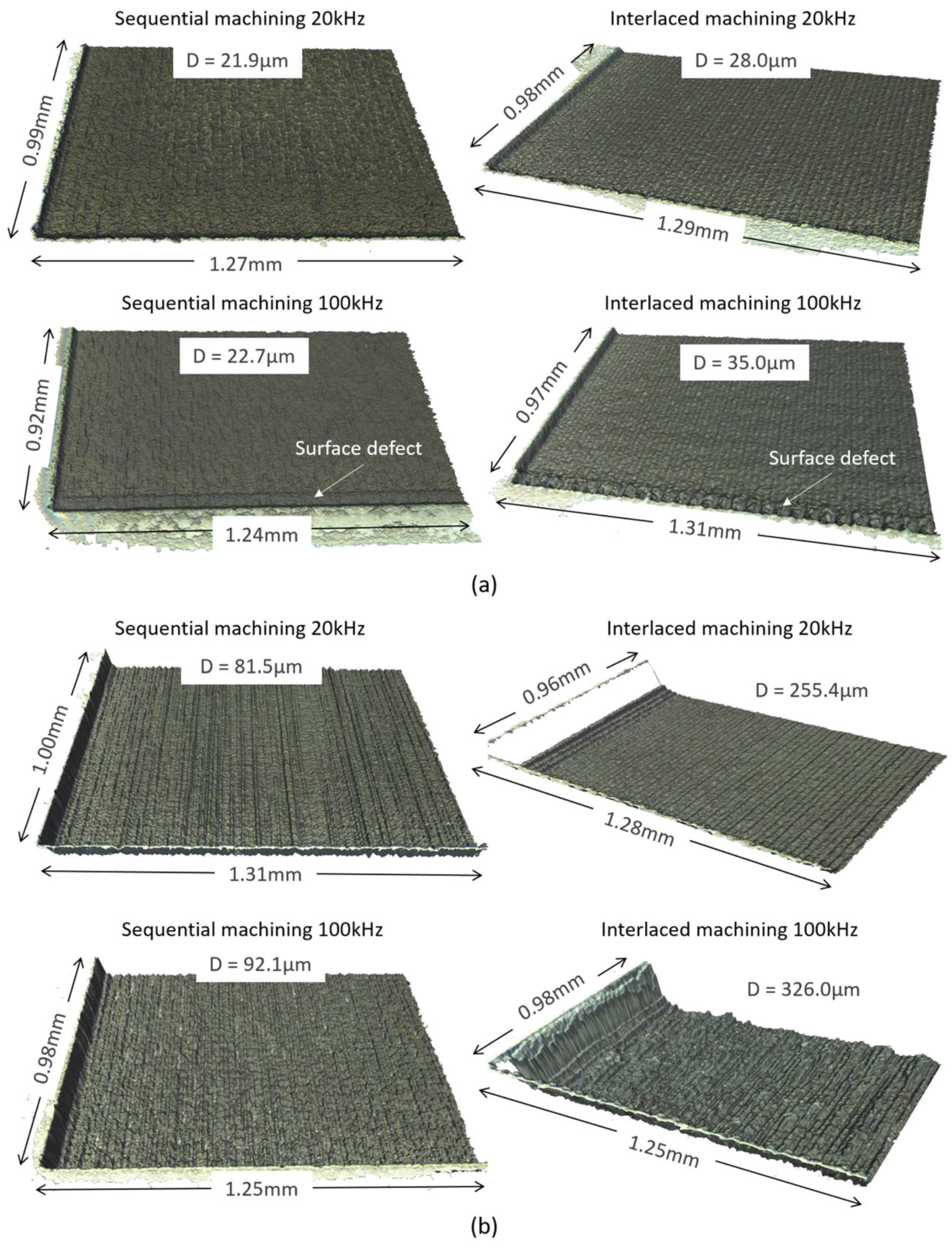

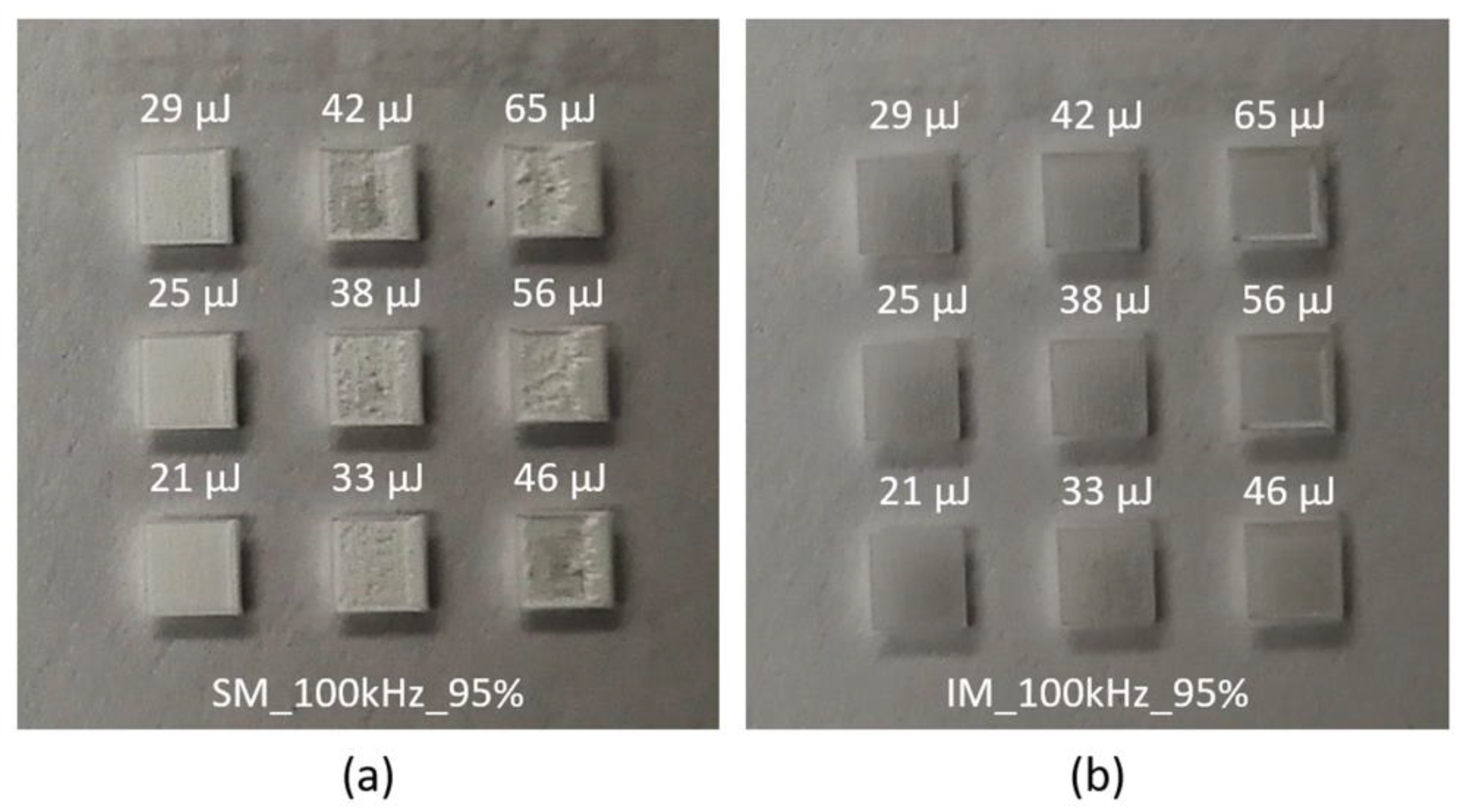

4.1. Qualitative Analysis

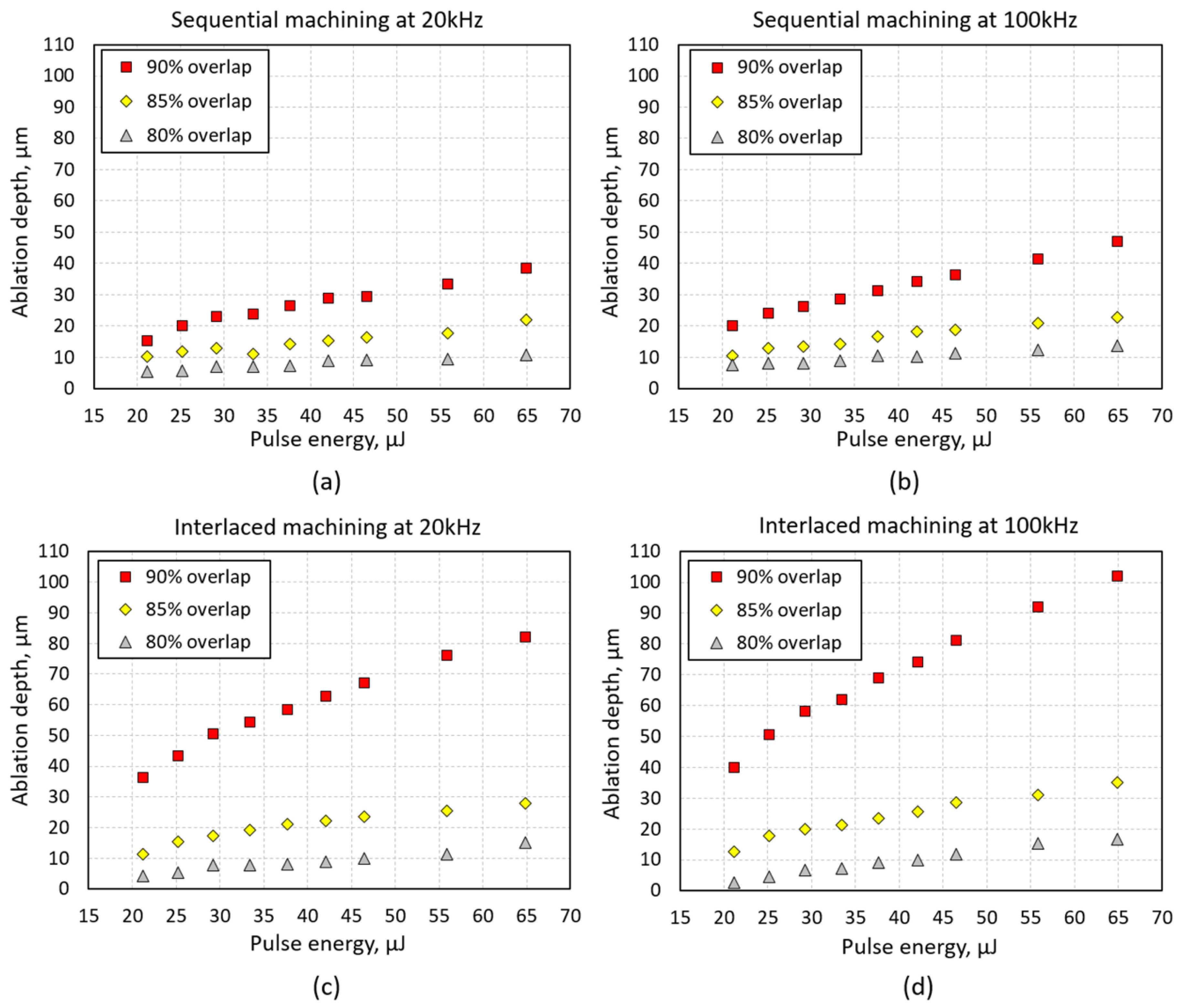

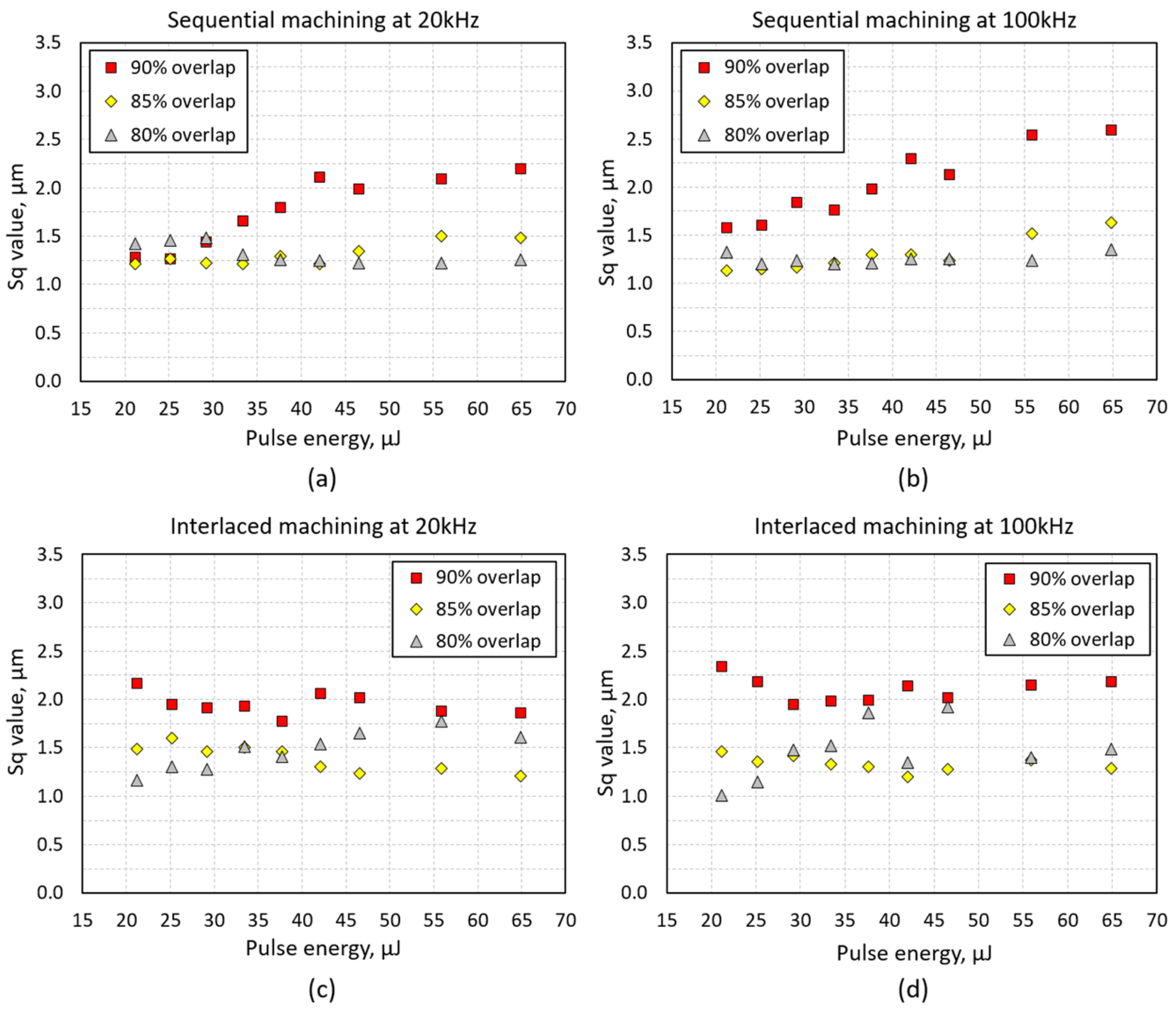

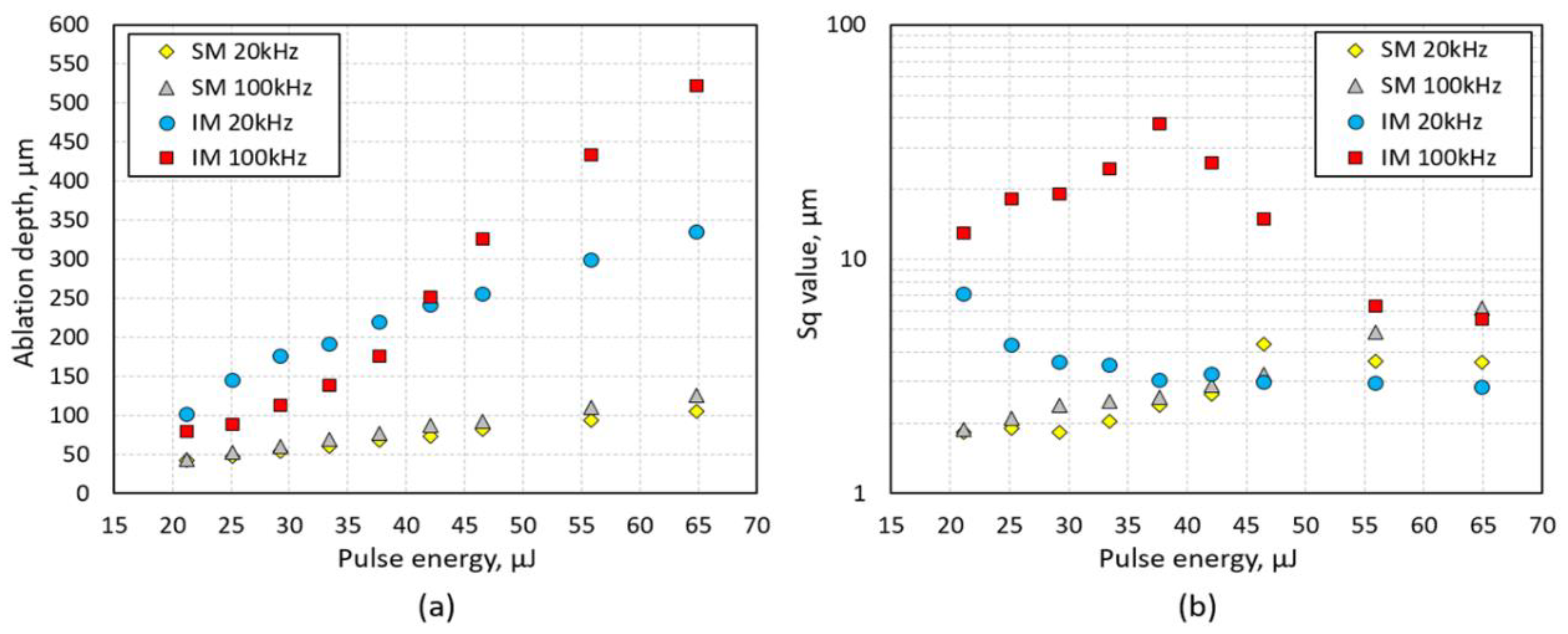

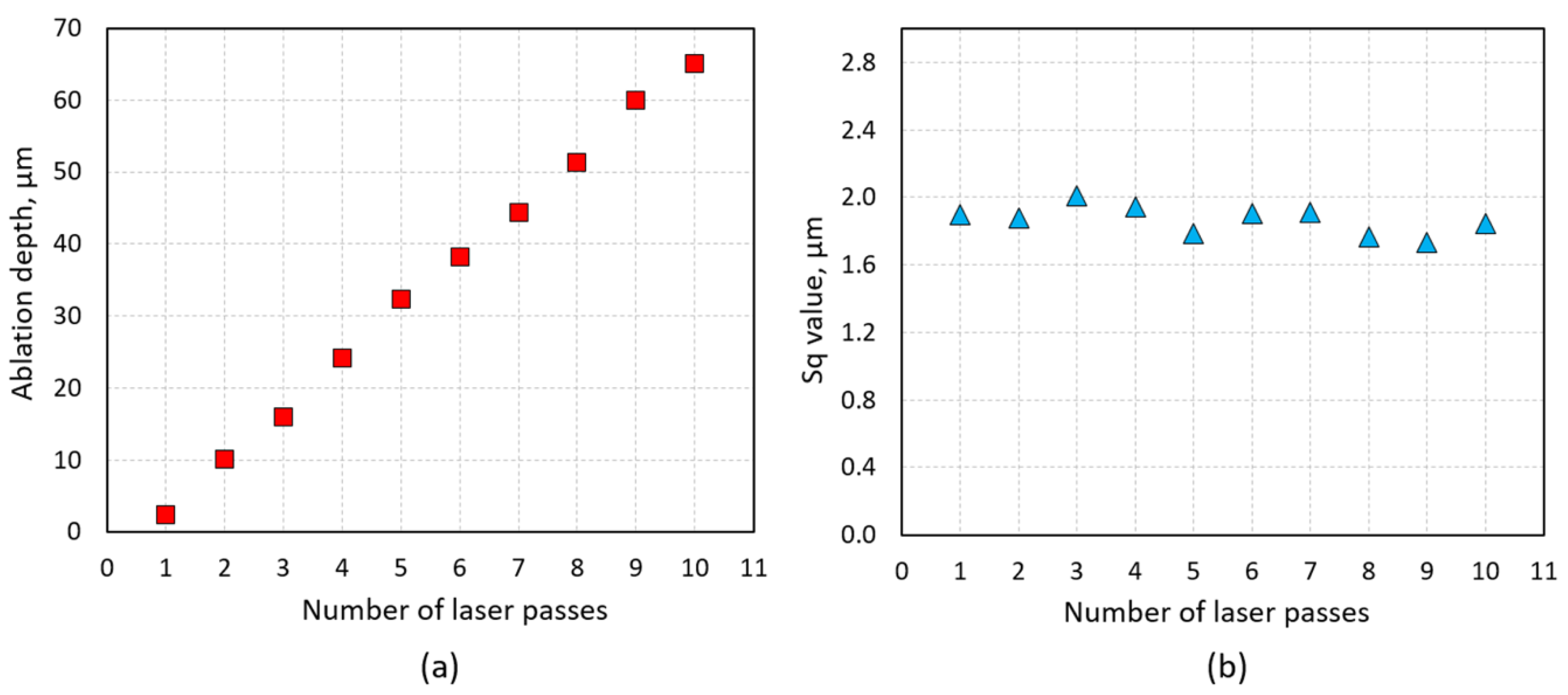

4.2. Ablation Depth and Surface Roughness

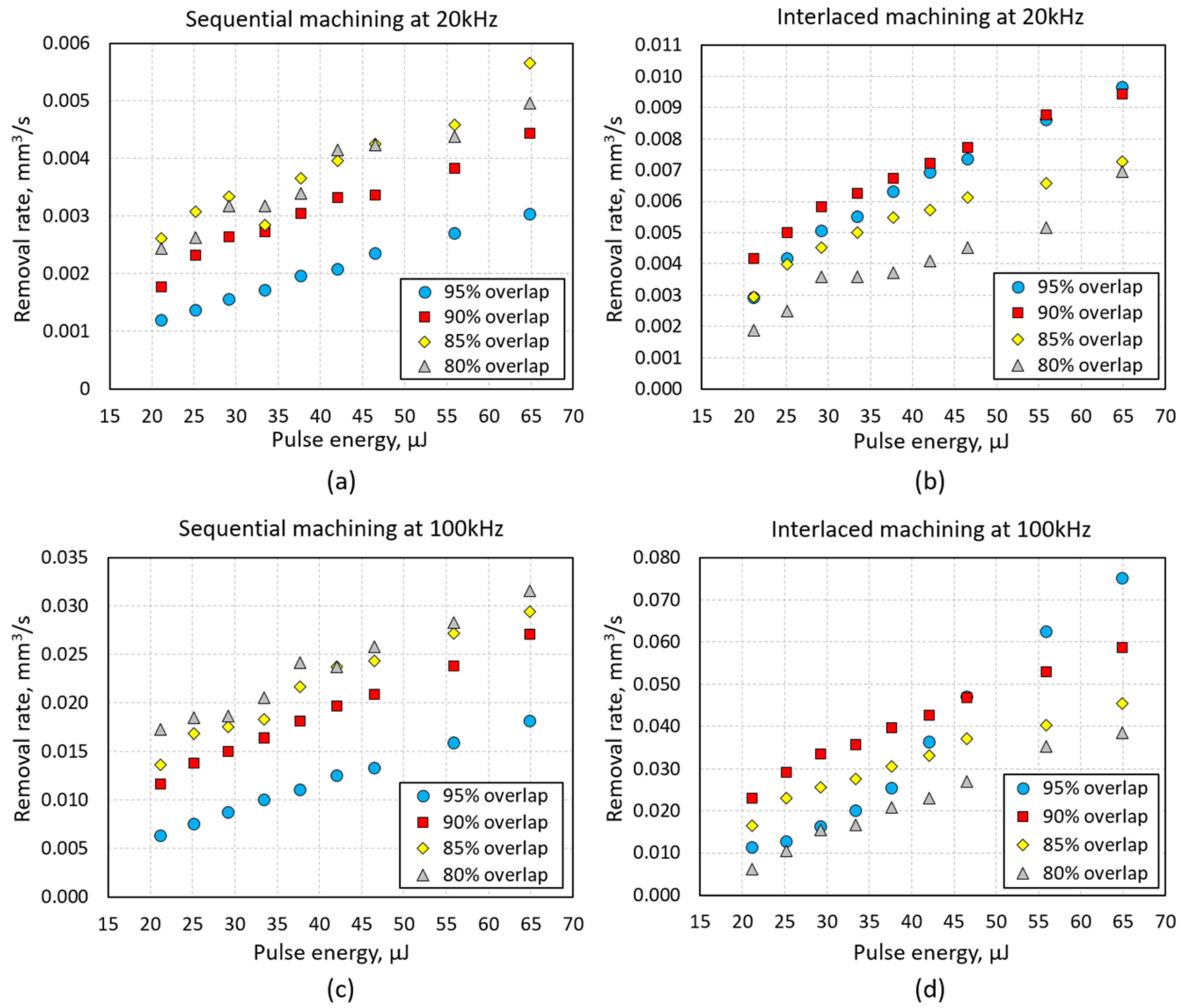

4.3. Removal Rate Analysis

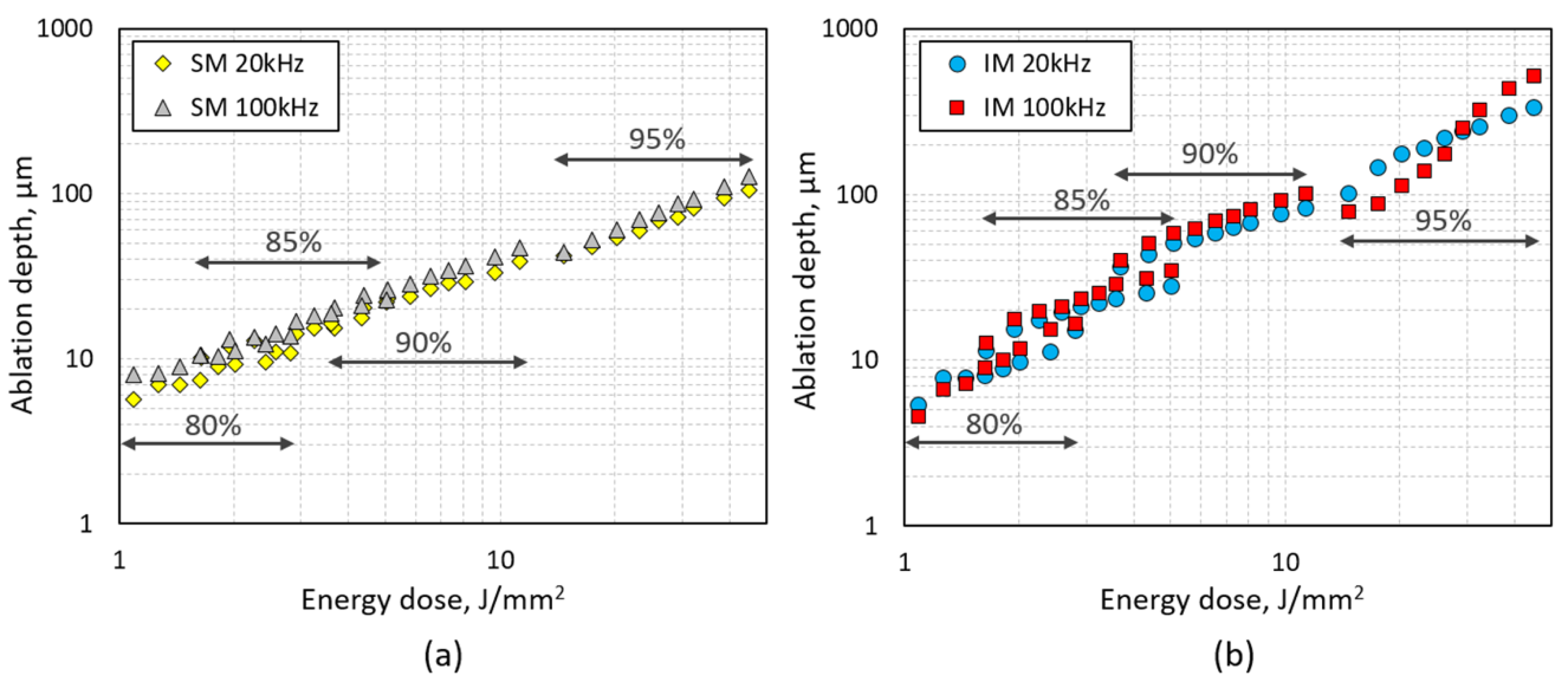

4.4. Simplified Model of IM

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Dahotre, N.B.; Harimkar, S.P. Manufacturing processes: An overview. In Laser Fabrication and Machining of Materials; Springer Science & Business Media: New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 69–96. [Google Scholar]

- Shirk, M.D.; Molian, P.A. A review of ultrashort pulsed laser ablation of materials. J. Laser Appl. 1998, 10, 18–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, S.; Yadava, V. Laser Beam MicroMachining (LBMM)—A review. Opt. Laser Eng. 2015, 73, 89–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinauskas, M.; Žukauskas, A.; Hasegawa, S.; Hayasaki, Y.; Mizeikis, V.; Buividas, R.; Juodkazis, S. Ultrafast laser processing of materials: From science to industry. Light Sci. Appl. 2016, 5, e16133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shugaev, M.V.; Wu, C.; Armbruster, O.; Naghilou, A.; Brouwer, N.; Ivanov, D.S.; Derrien, T.J.; Bulgakova, N.M.; Kautek, W.; Rethfeld, B.; et al. V Fundamentals of ultrafast laser—Material interaction. MRS Bull. 2014, 960–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeiffer, M.; Engel, A.; Weißmantel, S.; Scholze, S.; Reisse, G. Microstructuring of steel and hard metal using femtosecond laser pulses. Physci. Proc. 2011, 12, 60–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C.-W.; Tsai, X.-Z.; Chen, J.-S. Micromachining of stainless steel with controllable ablation depth using femtosecond laser pulses. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2016, 85, 1947–1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugioka, K.; Cheng, Y. Fabrication of 3D microfluidic structures inside glass by femtosecond laser micromachining. Appl. Phys. A Mater. 2014, 114, 215–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugioka, K. Progress in ultrafast laser processing and future prospects. Nanophotonics 2017, 6, 393–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, R.R.; Bookey, H.T.; Psaila, N.D.; Fender, A.; Campbell, S.; MacPherson, W.N.; Barton, J.S.; Reid, D.T.; Kar, A.K. Ultrafast-laser inscription of a three dimensional fan-out device for multicore fiber coupling applications. Opt. Express 2007, 15, 11691–11697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomas, J.; Voigtländer, C.; Becker, R.G.; Richter, D.; Tünnermann, A.; Nolte, S. Femtosecond pulse written fiber gratings: A new avenue to integrated fiber technology. Laser Photonics Rev. 2012, 6, 709–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gross, S.; Withford, M.J. Ultrafast-laser-inscribed 3D integrated photonics: Challenges and emerging applications. Nanophotonics 2015, 4, 332–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paiè, P.; Bragheri, F.; Di Carlo, D.; Osellame, R. Particle focusing by 3D inertial microfluidics. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2017, 3, 17027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, R.M.; Chen, J.; Shephard, J.D.; Thomson, R.R.; Hand, D.P. Picosecond laser welding of similar and dissimilar materials. Appl. Opt. 2014, 53, 4233–4238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wlodarczyk, K.L.; Carter, R.M.; Jahanbakhsh, A.; Lopes, A.A.; Mackenzie, M.D.; Maier, R.R.J.; Hand, D.P.; Mercedes Maroto-Valer, M. Rapid laser manufacturing of microfluidic devices from glass substrates. Micromachines 2018, 9, 409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bulgakova, N.M.; Zhukov, V.P.; Collins, A.R.; Rostohar, D.; Derrien, T.J.Y.; Mocek, T. How to optimize ultrashort pulse laser interaction with glass surfaces in cutting regimes? Appl. Surf. Sci. 2015, 336, 364–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, A.A.; Wlodarczyk, K.L.; Blair, P.; McBride, R.; Hand, D.P. High speed unltrafast laser based machining of glass. In Proceedings of the 19th International Symposium on Laser Precision Microfabrication (LPM), Edinburgh, UK, 25–28 June 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Neuenschwander, B.; Jaeggi, B.; Zimmermannn, M.; Markovic, V.; Resan, B.; Weingarten, K.; de Loor, R.; Penning, L. Laser surface structuring with 100 W of average power and sub-ps pulses. J. Laser Appl. 2016, 28, 022506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domke, M.; Piredda, G.; Bernard, B.; Matylitsky, V. Cutting thin glasses with ultrafast lasers. In Proceedings of the Lasers in Manufacturing 2017, Munich, Germany, 26–29 June 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Yakar, A.; Byer, R.L. Femtosecond laser ablation properties of borosilicate glass. J. Appl. Phys. 2004, 96, 5316–5323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hecht, E. The propagation of light. In Optics; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2017; pp. 96–158. [Google Scholar]

- Machado, L.M.; Samad, R.E.; Freitas, A.Z.; Vieira, N.D.; de Rossi, W. Microchannels direct machining using the femtosecond smooth ablation method. Physics Procedia 2011, 12, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Pulse Overlap (O) | Scanning Method & PRF Used | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SM 20 kHz | SM 100 kHz | IM 20 kHz | IM 100 kHz | |

| 75% (ΔH, ΔS = 6 μm) | v = 120 mm/s tM = 1.4 s/mm2 | v = 600 mm/s tM = 0.3 s/mm2 | v = 120 mm/s tM = 1.4 s/mm2 | v = 600 mm/s tM = 0.3 s/mm2 |

| ΔIL = 24 μm | ||||

| N = 27,889 pulses/mm2 | ||||

| 80% (ΔH, ΔS = 4.8 μm) | v = 96 mm/s tM = 2.2 s/mm2 | v = 480 mm/s tM = 0.4 s/mm2 | v = 96 mm/s tM = 2.2 s/mm2 | v = 480 mm/s tM = 0.4 s/mm2 |

| ΔIL = 24 μm | ||||

| N = 43,264 pulses/mm2 | ||||

| 85% (ΔH, ΔS = 3.6 μm) | v = 72 mm/s tM = 3.9 s/mm2 | v = 360 mm/s tM = 0.8 s/mm2 | v = 72 mm/s tM = 3.9 s/mm2 | v = 360 mm/s tM = 0.8 s/mm2 |

| ΔIL = 21.6 μm | ||||

| N = 77,284 pulses/mm2 | ||||

| 90% (ΔH, ΔS = 2.4 μm) | v = 48 mm/s tM = 8.7 s/mm2 | v = 240 mm/s tM = 1.7 s/mm2 | v = 48 mm/s tM = 8.7 s/mm2 | v = 240 mm/s tM = 1.7 s/mm2 |

| ΔIL = 24 μm | ||||

| N = 173,889 pulses/mm2 | ||||

| 95% (ΔH, ΔS = 1.2 μm) | v = 24 mm/s tM = 34.7 s/mm2 | v = 120 mm/s tM = 6.9 s/mm2 | v = 24 mm/s tM = 34.7 s/mm2 | v = 120 mm/s tM = 6.9 s/mm2 |

| ΔIL = 24 μm | ||||

| N = 693,889 pulses/mm2 | ||||

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wlodarczyk, K.L.; Lopes, A.A.; Blair, P.; Maroto-Valer, M.M.; Hand, D.P. Interlaced Laser Beam Scanning: A Method Enabling an Increase in the Throughput of Ultrafast Laser Machining of Borosilicate Glass. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2019, 3, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp3010014

Wlodarczyk KL, Lopes AA, Blair P, Maroto-Valer MM, Hand DP. Interlaced Laser Beam Scanning: A Method Enabling an Increase in the Throughput of Ultrafast Laser Machining of Borosilicate Glass. Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing. 2019; 3(1):14. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp3010014

Chicago/Turabian StyleWlodarczyk, Krystian L., Amiel A. Lopes, Paul Blair, M. Mercedes Maroto-Valer, and Duncan P. Hand. 2019. "Interlaced Laser Beam Scanning: A Method Enabling an Increase in the Throughput of Ultrafast Laser Machining of Borosilicate Glass" Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing 3, no. 1: 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp3010014

APA StyleWlodarczyk, K. L., Lopes, A. A., Blair, P., Maroto-Valer, M. M., & Hand, D. P. (2019). Interlaced Laser Beam Scanning: A Method Enabling an Increase in the Throughput of Ultrafast Laser Machining of Borosilicate Glass. Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing, 3(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp3010014