Abstract

The path planning process for an unmanned aerial vehicle is a complex process due to different operating environment conditions and aircraft constraints. The particle swarm optimization algorithm is one of several heuristic techniques used to solve the path planning problem. However, it has been observed that this algorithm tends to converge prematurely to a local optimum, resulting in poor quality paths. This paper proposes an adaptive strategy for calculating the inertia weight (KPSO) of the particles in the PSO algorithm for UAV path planning in a real-world environment. The strategy was applied to a reconnaissance mission during an eruptive event based on the Popocatepetl volcano area in Mexico and was found to outperform other adaptive strategies from the literature in a specific scenario.

1. Introduction

In recent years, unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) have gained relevance due to their versatility and ability to perform specific tasks autonomously. Autonomy, understood as the ability of an aircraft to perform functions without human intervention [1], has become a fundamental factor for UAVs. This allows them to perform various activities in a field such as telecommunications, logistics, inspection, surveillance, search and rescue, among others [2,3,4,5,6]. However, the success of these missions depends heavily on a fundamental aspect of UAV autonomy: the path planning process.

This process must consider multiple factors, such as the presence of obstacles, weather conditions, and mission objectives. An inadequate route can result in extended flight times, increased fuel usage, or loss of the aircraft. Therefore, different algorithms for route planning have been developed, such as heuristic, sample-based, and biologically based algorithms [7,8,9], among which the particle swarm optimization (PSO) algorithm stands out due to its simplicity and ability to solve complex problems without requiring exhaustive knowledge of the problem in question [10]. However, the challenge lies in finding the right balance between the exploration and exploitation capabilities of the algorithm, as an imbalance can affect its performance and lead to convergence to local optima, resulting in paths unsuitable for the UAV mission. A critical component that influences the performance and convergence of the PSO algorithm is the calculation of the inertia weight [11]. Over the years, various strategies have been proposed to dynamically compute the value of the inertia weight into the PSO algorithm to improve the algorithm’s ability to explore and exploit the search space [12].

In this context, this paper proposes a strategy for calculating the inertia weight of the PSO algorithm, called KPSO, applied to the path planning of a UAV based on a convex function with respect to a control factor. This strategy provides the PSO with an intense search space exploration capability at the beginning of its execution, as well as a smooth transition to the search space exploitation stage. It is also proposed that the paths obtained using our strategy be contrasted against different strategies established in the literature. For this purpose, a real-world operating environment based on the Popocatepetl volcano area in Mexico was used to simulate the development of a reconnaissance mission in an eruptive event and to contrast the algorithm’s performance using the strategy proposed in this paper. The objective is to validate that the proposed strategy performs better than other adaptive strategies regarding convergence, swarm diversity, and the quality of the paths found. The results obtained have the potential to contribute to the improvement of the PSO algorithm and its applicability to a wide range of optimization problems.

The subsequent sections of this paper are structured as follows: Section 2 presents the theoretical underpinnings of path planning, the PSO algorithm. Section 3 contains related work on inertia weighting strategies. Section 4 presents the strategy proposed in this paper, and metrics for assessing swarm diversity. Section 5 describes the details of the operating environment for the simulation and experimentation stage, as well as the results obtained. Finally, Section 6 presents the conclusions of the present paper and potential directions for future research.

2. Background

2.1. UAV Path Planning

Path planning for UAVs is a process that involves determining the points in space that describe the trajectory to be followed. It is a global optimization challenge of a complex nature, in which the constraints of both the environment and the aircraft itself must be considered [13].

UAVs, which have experienced rapid development in both civil and military applications, find in the path planning process a crucial element to make the most of their capabilities. This planning can directly influence the effectiveness of the mission they are tasked with. When carrying out path planning, it is essential to consider several factors to achieve an optimal result. These factors include the optimization and completeness of the path, as well as the computational complexity of the algorithm in the process. In addition, it is essential to consider variables such as maximum path length and maximum aircraft turn and tilt angles [14].

The path to be followed by the aircraft during a flight is defined as the set of configurations that the aircraft can achieve when moving from one configuration to another. In essence, this path becomes an interpolation of coordinates describing the position of the UAV, as highlighted in the work of Sebbane [1]. The solution to the path planning problem focuses on optimizing an objective function that is formulated in terms of the distance the aircraft travels between the configurations connecting a point of origin to a point of destination, all under the fulfillment of various constraints.

The representation of the path to be followed by the UAV is modeled as a set of coordinates representing the configurations to be achieved by the aircraft, also known as waypoints. This is defined by the following expression:

where K is the total number of waypoints making up the path.

The constraints associated with the path planning process, arising from aircraft limitations, include the maximum turn angle and the maximum elevation angle. The turn angle refers to the angle formed by two path segments that describe a change in direction of flight of the aircraft. This angle indicates the magnitude of the rotation that the UAV must make to change its heading to a new direction and is determined by the following equation:

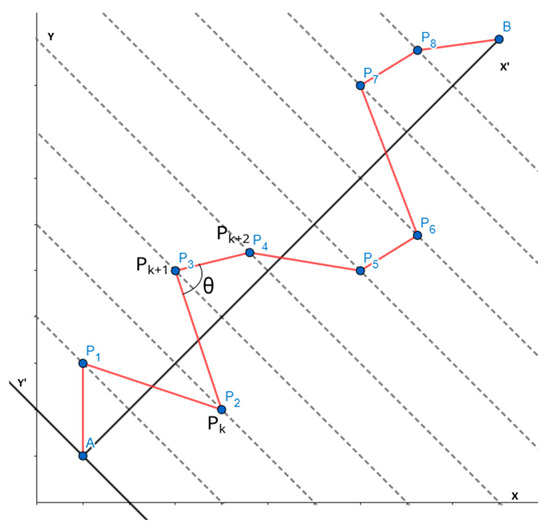

As shown in Figure 1, the angle θ represents the turning angle formed by segments and .

Figure 1.

Transformation of coordinates and turn angle on the path.

The turn angle is critical to the UAV path planning process as it determines how much it must turn to follow the desired trajectory, affects its maneuverability, and its response during flight.

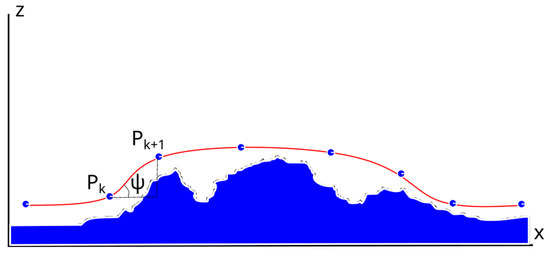

Likewise, the elevation angle is the angle between the horizontal plane and the line of sight or path of the UAV with respect to a reference point. This angle indicates how much the UAV rises or falls with respect to the horizontal and is determined by the following equation:

The elevation angle is directly related to the UAV altitude control. In autonomous flight, it is essential for following three-dimensional paths that include altitude changes as show in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Representation of UAV operating height and path elevation angle.

In addition, it is essential to consider the operating altitude of the UAV depending on the mission objective and the safety of the aircraft. In missions where stealth and radar detection avoidance are the priority, it is necessary to ensure that the operating altitude is as low as possible, without compromising the aircraft to possible collisions with obstacles such as trees or high voltage lines [15]. Therefore, the altitude for each of the points along the path is limited by the following expression:

2.2. Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO)

The particle swarm optimization (PSO) algorithm is a process in which a set of agents, called particles, move through a search space to find an optimal solution to a given problem [16]. In the path planning context, the particles inside the swarm represent possible paths to guide a UAV from its origin to its destination, avoiding obstacles present in the operating environment.

The process begins by initializing the swarm of particles, assigning them random positions in the search space, and evaluating the qualification of these positions. Once the swarm is initialized, each particle explores the search space by updating its velocity and position.

where:

- is the inertial motion factor of the particle.

- are cognitive and social learning factors, respectively.

- are random factors between 0 and 1.

- represents the best historical position that the particle has ever occupied.

- represents the best historical position among all particles in the swarm.

The position of the particle represented by is updated by the following expression:

According to the equations presented, first, the velocity at which the particles move in the search space and their new position is decided. Then, the aptness of the solution is evaluated at its current position. This process is repeated until the stopping conditions of the algorithm are fulfilled, as illustrated in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1. Particle swarm optimization |

| 1: for each particle i = 1, 2, …, n |

| randomly |

| 3: evaluate particle |

| 5: end for |

| 7: do |

| 8: for each particle i = 1, 2, …, n |

| 9: update particle velocity according to Equation (5) |

| 10: update particle position according to Equation (6) |

| 11: evaluate particle |

| 13: end for |

| 15: while maximum iteration or stop criteria are not attained |

The basic variant of the algorithm (BPSO) uses fixed values for the inertia weight and learning factors . However, properly balancing exploration and exploitation can be challenging and can lead to premature convergence to local optima. To address this problem, different mechanisms have been proposed; one of these mechanisms consists of dynamically varying the cognitive and social learning factors as described by Equations (7) and (8).

where:

- are the maximum and minimum values of the learning factors of the algorithm.

- is the current iteration and is the total number of iterations of the algorithm.

With this approach, the cognitive learning factor decreases, while the social learning factor increases with each iteration. This prioritizes the exploration of the search space at the beginning of the optimization process, leaving the exploitation of the space where the optimal value could be found for the final stage of the process.

3. Related Work

Finding the right balance between the exploration and exploitation capabilities of the PSO is a problem that has been attacked from different perspectives. One of them consists of combining the PSO algorithm with other algorithms that allow avoiding convergence to a local optimum by providing a better balance between the exploration and exploitation capabilities of the algorithm. Some approaches have opted to incorporate techniques for dynamic obstacle management and smoothing of the UAV path to provide higher-quality trajectories [17]. In [18], the PSO was combined with the gravitational search algorithm (GSA) to improve the convergence speed of the algorithm in solving the underwater electric dipole source localization problem. Another alternative was presented in [19], where the PSO was combined with the Gray Wolf Optimization (GWO) algorithm to obtain a mechanism for calculating the inertia weight. In [20], an approach combining the PSO with the simulated annealing algorithm is proposed, presenting better stability and efficiency than other PSO variants.

Inertia weight is a determining factor to properly balance the search capabilities of the PSO; for this reason, different strategies for its calculation have been proposed. Shi and Eberhart in [10] suggest a linearly decreasing approach for the calculation of the inertia weight (LPSO) to improve the performance of the PSO. This approach was taken up in [21], where the calculation of the inertia weight is described according to expression (9), where are the maximum and minimum values of the inertial weight, is the current iteration, and is the total number of iterations of the algorithm, resulting in a faster convergence compared to standard PSO.

However, this approach decreases the global search capability of the PSO towards the end of its execution, even when, in some cases, this ability is necessary to get out of a local optimum. This can lead the PSO to fail in complex problems.

In contrast, a second approach uses a high-order nonlinear function to reduce the inertia weight (NLPSO), as shown in Equation (10), where is a factor that controls the rate of change of the inertia weight. This method improves both convergence speed and solution accuracy relative to the standard PSO and LPSO [22].

The accelerated convergence rate of the NLPSO is due to the fact that the value of the inertia weight decays rapidly, favoring local search. This is not a problem for the unconstrained optimization problems with which the NLPSO was tested.

On the other hand, Li and Gao proposed a PSO implementation with an exponent decreasing inertia weight (EPSO), as defined in Equation (11), which helps the algorithm escape local optima more easily and prevents premature convergence [23].

Among them, and are parameters that control the rate of change of the inertia weight. However, when it comes to optimizing a benchmark function such as the Rastrigin function, whose local minima increase with the size of the problem, the EPSO approach tends to get trapped in a local optimum.

To address the slow convergence of the PSO in the specific path planning problem, a strategy called distant-dependent sigmoidal inertia weight (DSIPSO) was proposed in [24]. In this strategy, each particle dynamically adjusts its inertia weight based on its distance from the global best particle in the swarm and then uses a sigmoid function to calculate the inertia weight as described in Equation (12).

where represents the distance metric between the particle and the global best particle in the swarm. This approach showed the best results compared to other PSO variants for different benchmark functions. Similarly, it showed the best routes in various scenarios for path planning of a smart vehicle in a two-dimensional environment, so it could yield good results in the three-dimensional scenario proposed in this paper.

In a similar approach, Tian et al. use a sigmoid function to propose a nonlinear dynamic adjustment for the inertia weight (CSPSO), as described in Equation (13).

where is used to adjust the rate of change of the sigmoid function. The proposed strategy maintains a high inertia weight value and a slower rate of change, which allows the algorithm to maintain a higher number of iterations in the global search process and, in turn, improve the global search capabilities [25].

In [26], a concave function exponential decreasing scheme and a concave function increasing scheme for the inertia weight calculation were introduced. The first strategy was designed to explore the impact of the inertia weight change speed on the algorithm. This approach allows maintaining a high value of inertia weight during a large number of iterations, which can favor the global search capacity of the algorithm. However, this may affect the local search capability of the PSO since, in some cases, it is more convenient for the inertia weight to be kept at a uniformly low value during the last iterations of the algorithm. The second strategy was designed to explore the effect of nonlinear increasing inertia weight on algorithm evolution. This strategy allows the value of the inertia weight to be increased slowly with respect to the algorithm iterations. This allows the inertia weight to be kept in a low range of values and then increased towards the last iterations of the algorithm. However, this limits the global search capability of the algorithm, favoring convergence to a local optimum, and the accelerated increase in the inertia weight towards the end of the algorithm iterations does not influence the optimal solution found by that time.

Among them, is a variable parameter reserved for weight change.

These strategies were tested against other variants of the PSO algorithm, using different benchmark functions, except the DSIPSO strategy which was also tested in a two-dimensional environment. In this paper, these strategies were applied to a reconnaissance mission in a complex environment and serve as a benchmark to compare with the proposed strategy.

4. Proposed Method

4.1. PSO Implementation for the Path Planning Problem

The value of the inertia weight significantly affects the performance of the PSO algorithm. Different approaches to inertia weight have been extensively explored, with various strategies proposed in the literature, all demonstrating improved performance over the original algorithm.

In this paper, an adaptive strategy for inertia weight calculation called KPSO is proposed, as described by the expression (17)

where is a factor that decreases linearly in a range from and .

The proposed function is convex for , which implies that the rate of decrease of inertia weight is not constant. At first, when maintains a high value, the inertia weight decreases rapidly; as decreases, so does the rate of decrease of the inertia weight. This allows the PSO an intense exploration of the search space during the first iterations, as well as a smooth transition to the exploitation of the search space, which reduces the risk of particles being trapped in a local optimum. Additionally, the proposed strategy is highly adaptable since the linear decrement of can be adjusted according to the number of iterations and the complexity of the problem.

On top of that, it is crucial to model the objective function of the PSO algorithm, which allows for determining the qualification of each particle in the swarm. In the context of path planning, the objective function is stated in terms of the length of the path, with the aim of minimizing its distance. Considering K waypoints composing the path, the objective function is described by the expression (18)

To reduce the computation time, a waypoint coordinate transformation was carried out. The new coordinate system is formed from the line joining the start and destination point of the mission, which represents the new axis, as well as from the line perpendicular to it, which represents the new axis, as illustrated in Figure 1.

The axis is divided into equidistant segments, drawing a straight line perpendicular to the axis on which the corresponding coordinate on the axis is located. Considering then a safe operating height above the ground level, illustrated in Figure 2, the waypoints to be determined can be expressed as

Thus, the path planning process starts with the initialization of the position and velocity of the swarm particles according to the coordinate transformation described above. The swarm is evaluated to establish the personal best position of each particle. Subsequently, the inertia weight is calculated with which the velocity and position of each particle are updated, evaluating its fitness with each update until the stopping condition of the algorithm is reached.

4.2. Swarm Diversity Measurement

On the other hand, due to the difficulty in adequately balancing the exploration and exploitation capabilities of the algorithm, it is important to measure them to analyze the behavior of the algorithm. This measurement can be performed in terms of swarm diversity, which is a way of monitoring the degree of convergence or divergence of the PSO in the search process [27]. Swarm diversity was analyzed from three approaches: population diversity, velocity diversity, and cognitive diversity.

Position diversity provides information on the distribution of particles in the search space and whether they tend to converge or diverge. This can be expressed by the following equation:

where represents the average of the current position of the particles in each dimension.

In turn, the trend of the velocity of each particle provides information about the activity of the particles, allowing them to know the tendency of the particles to expand or converge in the search space. This is expressed by the following equation:

where represents the average of the current particle velocity in each dimension.

Finally, cognitive diversity represents the distribution of all current moving targets found by particles. This is expressed by the following equation:

where represents the average of all particles’ best position on each dimension.

Although it is wanted for the path distance obtained by the PSO algorithm to be as small as possible, it is important to study the measuring of the diversity of the swarm while considering the position and velocity of the particles since the algorithm tends to converge to a local optimum. With PSO iterations, it is observed that the distance between particles decreases, causing the same effect on the diversity of the population. This impacts the overall search capability of the algorithm and in turn can lead to premature convergence [28]. The measuring of diversity provides information that can help to properly balance the capabilities of the algorithm to find a suitable solution.

5. Simulation and Experimentation

The modeling of the operating environment is the process by which information about the physical elements present is transformed into a data model that facilitates path planning. The operating environment modeled in this paper corresponds to the area of the Popocatepetl volcano, located 40 km from Mexico City, Mexico.

Since 1990, the activity of the Popocatepetl volcano has increased, so that in December 1994, an event was recorded that was characterized by a series of consecutive explosions produced by magmatic gases, which opened the central dome of the volcano, causing ash fall and the formation of a new mouth in the eastern part of the interior of the crater. Since then, the volcano has been more active, with explosions, fumaroles, and ash fall. The risk posed by the increased volcanic activity of Popocatepetl makes it necessary to maintain constant monitoring, especially during an eruptive event. For this reason, a model of the Popocatepetl volcano environment and possible risk zones is proposed as a test scenario for a UAV whose mission is to perform a reconnaissance flight over the area during a strombolian eruption, for which it is necessary to carry out the path planning process.

The terrain modeling was carried out using data from the Mexican elevation continuum, which represents the elevations of the continental territory (Z) whose location is defined by coordinates (X, Y). The points are regularly spaced and distributed.

The operating environment was divided into two scenarios according to the wind patterns in the region from October to May and June to September [29]. For both scenarios, a first risk zone was considered around the volcano crater, and three additional risk zones were considered, distributed towards the east of the volcano for the first scenario and towards the west for the second scenario. The distribution of the risk zones for the October-May scenario is shown in Table 1, while for the June-September scenario it is shown in Table 2 where (X, Y, Z) represent the coordinates where the risk zone is located, while (X′, Y′, Z′) denote the dimensions of each axis of the ellipsoid that models the risk zone in both tables.

Table 1.

Location of the risk zones for the October–May scenario.

Table 2.

Location of the risk zones for the June–September scenario.

It is in these scenarios that the path planning process was carried out using the PSO algorithm in different variants, to contrast the results with those obtained when using the PSO variant that is proposed in this paper.

The configuration parameters for the implementation of the PSO algorithm are: number of particles composing the swarm, N = 50; number of waypoints composing the path, K = 20; maximum number of iterations, T = 4000; inertial weight, ; learning factors, ; maximum turn angle ; maximum elevation angle, ; mission control points, ; so that the mission requires the following paths .

5.1. Results

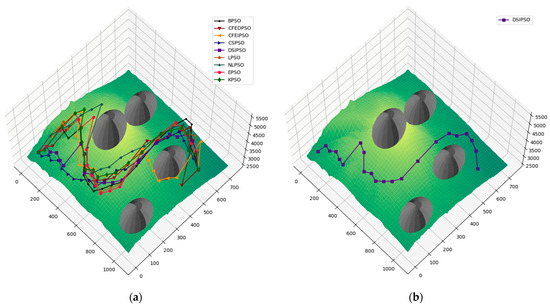

Under the conditions described above, thirty experiments were carried out with each of the strategies for calculating the inertia weight in each scenario. The paths obtained by the PSO algorithm using the different adaptive strategies for the October–May scenario are shown in Figure 3. Considering the feasible paths for a UAV, in the October–May scenario, the DSIPSO strategy presented the best fitness value, i.e., it obtained the shortest path. It also presented the best paths on average based on the number of experiments performed. In terms of swarm diversity, both position diversity and cognitive diversity registered intermediate values with respect to those obtained by the other strategies; see the values highlighted in Table 3’s results for the October–May scenario.

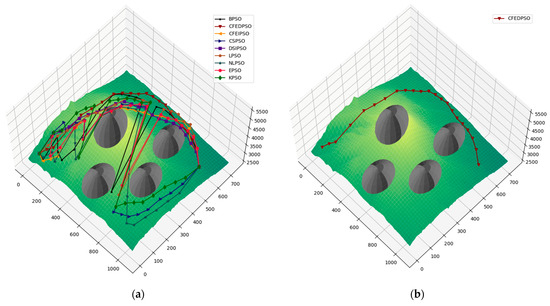

Figure 3.

(a) Paths obtained for the October–May scenario with the different strategies for inertia weight calculation. (b) Path determined by the DSIPSO strategy; the best obtained for the October–May scenario.

Table 3.

Results for the October–May scenario.

On the other hand, the proposed strategy KPSO ranked third among the tested strategies with respect to the best route obtained. It also presents the highest value of position diversity and velocity diversity, which indicates that the swarm particles are more dispersed in the search space and more active. However, this did not result in a shorter path length within the iterations performed by the algorithm. It is possible that with additional iterations, better results could be achieved.

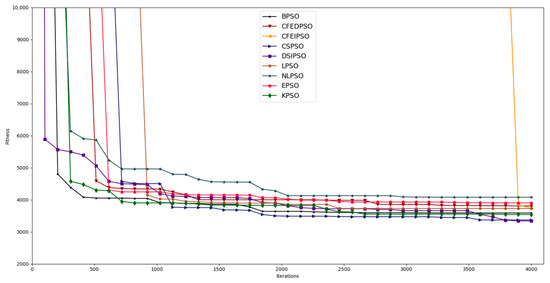

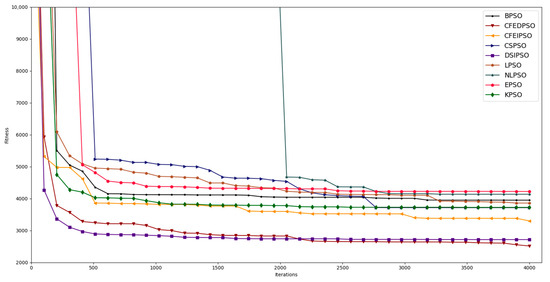

Considering the best paths obtained with each strategy, the evolution of the fitness of the best global solution found with each one was analyzed, the results of which are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Evolution of the global best particle fitness with each strategy in the October–May scenario.

Most of the strategies tested showed similar downward behavior. However, the CFEIPSO strategy maintained high fitness values during most iterations of the algorithm due to the incremental nature of the inertia weight calculation.

In the case of the June–September scenario, the paths obtained by the PSO algorithm using the different strategies are shown in Figure 5. In this case, the CFEDPSO strategy presented the shortest path as well as the best paths on average with respect to the other strategies for the calculation of the inertia weight. In terms of position diversity, an intermediate value was obtained, while cognitive diversity yielded the highest value among the tested strategies; see the values highlighted in Table 4.

Figure 5.

(a) Paths obtained for the June–September scenario with the different strategies for inertia weight calculation. (b) Path determined by the CFEDPSO strategy; the best obtained for the June–September scenario.

Table 4.

Results for the June–September scenario.

The proposed KPSO strategy in this scenario ranked fifth among the tested strategies, outperforming the basic PSO variant but far from the good performance of the CFEDPSO strategy. As in the October–May scenario, the position and velocity diversities it presented are some of the highest values with respect to the other strategies, indicating greater diversity in the swarm; however, this was not reflected in a shorter route length.

Considering the best paths obtained with each strategy, the evolution of the fitness of the best global solution found with each one was analyzed, the results of which are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Evolution of the global best particle fitness with each strategy in the June–September scenario.

In this scenario, the CFEDPSO and DSIPSO strategies showed the best fitness values during the algorithms’ execution. Interestingly, in both scenarios, the proposed KPSO strategy performed better than the basic variant of the BPSO algorithm and other less recent strategies such as LPSO, NLPSO, and EPSO.

It is also important to note that for each scenario, the strategy for calculating the inertia weight that presented the shortest path was different. The DSIPSO strategy performed well in both scenarios. The CFEDPSO strategy, which performed poorly in the October–May scenario, was the best in the June–September scenario. This suggests that the strategy proposed in this paper could perform better in another scenario.

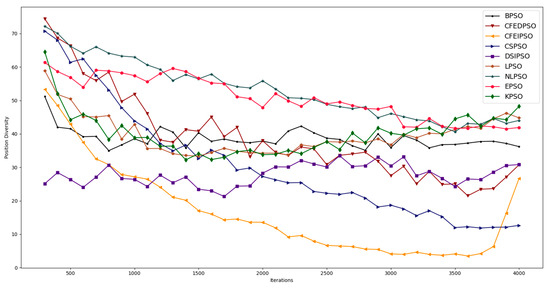

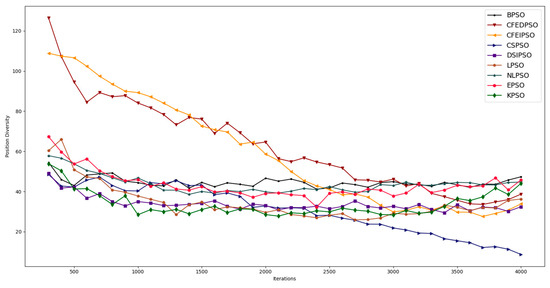

On the other hand, the evolution of swarm diversity in both scenarios was analyzed. For the October–May scenario, the best strategy, DSIPSO, started with the lowest value and ended with an average value of position diversity. The CFEDPSO strategy started with the highest value and ended with an average value for position diversity as well. Both strategies ended with similar position diversity values; however, there is a large difference between the fitness of the two strategies. The second-best strategy in this scenario, CSPSO, started with a high value of position diversity and ended with the lowest value, as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Evolution of position diversity with each strategy in the October–May scenario.

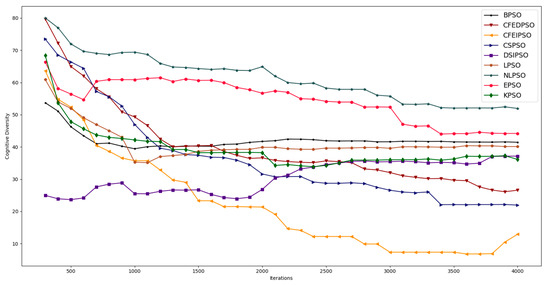

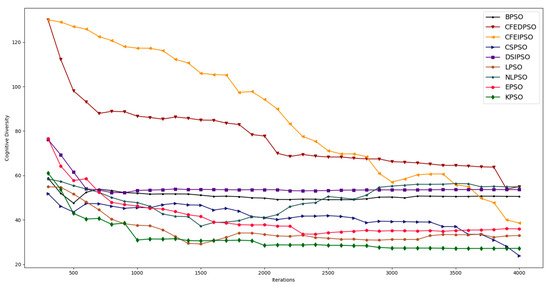

As for cognitive diversity, a similar phenomenon occurred. The DSIPSO strategy starts with a low value until reaching intermediate values, while the CSPSO strategy starts with high values until reaching one of the lowest values of cognitive diversity, see Figure 8.

Figure 8.

Evolution of cognitive diversity with each strategy in the October–May scenario.

For the June–September scenario, the best strategy, CFEDPSO, started with the highest value and ended with an average value of position diversity. The DSIPSO strategy started with the lowest value and ended with an average value for position diversity as well, as shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

Evolution of position diversity with each strategy in the June–September scenario.

In the case of cognitive diversity, the same pattern of behavior observed for position diversity was repeated for the CFEDPSO and DSIPSO strategies, as shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Evolution of cognitive diversity with each strategy in the June–September scenario.

5.2. Discussion

During this research, extensive testing and evaluations of different adaptive strategies for the calculation of inertial weight in the particle swarm optimization (PSO) algorithm were carried out. These strategies were subjected to rigorous analysis in an operating environment divided into two scenarios, to determine which of them showed the best performance in terms of the obtained path distance.

The results of our study indicate that the DSIPSO strategy stood out as the most effective strategy in terms of path distance for the October–May scenario. The low values of positional diversity and cognitive diversity presented with this strategy suggest that exploration is rapidly reduced, giving priority to the exploitation of the search space. This can be useful when the region where the global optimum is located is found quickly.

Similarly, for the June–September scenario, the CFEDPSO strategy was the most effective. Contrary to the DSIPSO strategy, this approach maintains the exploration of the search space for a longer time, which reduces the risk of premature convergence of the algorithm. The results obtained showed that a high value of position diversity is not a determinant for finding the best possible path since, in the case of the DSIPSO strategy, it started with a low value of position diversity. This fact is interesting since position diversity indicates how dispersed the particles are in the search space, and, generally, a higher diversity is sought to find better solutions and avoid convergence to a local optimum. This was also observed with respect to cognitive diversity. However, the results obtained indicate that the best strategies are those that maintain an appropriate balance between exploration and exploitation of the search space. The dynamics of the inertia weight do not necessarily imply that the PSO starts with a high or low diversity but with a value that allows a smooth transition between exploration and exploitation.

On the other hand, the results obtained show that the proposed strategy KPSO presents a better performance than the basic PSO algorithm, as well as strategies for the calculation of the inertia weight called LPSO, NLPSO, and EPSO. It was observed that the proposed strategy presents high values of position diversity with respect to the other strategies, indicating that the particles are more dispersed in the search space. It also presents the highest values of velocity diversity, which indicates a higher level of particle activity. On the other hand, cognitive diversity remains at intermediate values. These aspects suggest that the proposed strategy enables greater exploration of the search space, making it particularly advantageous for more complex scenarios. However, this comes at the cost of reduced exploitation capability, which explains why the best route was not achieved within the defined number of iterations. Increasing the number of iterations may allow the algorithm to yield better results. Additionally, the flexibility of the factor , which controls the decrease in the inertia weight, as shown in Equation (17), enables it to maintain a specific value during the final iterations, further enhancing its adaptability.

In addition, since the proposed strategy KPSO allows for viable paths to be obtained, it is not ruled out that this strategy could present better results for the same operating environment with different conditions than those tested in this paper.

6. Conclusions

The proposed strategy demonstrated a competent performance with respect to the strategies in the literature that were tested in this paper, giving a better performance than some of them despite not giving the best possible results. Additionally, it allows starting with an intense exploration of the search space and continuing with a smooth transition to exploitation, it is adaptive and reduces the risk of the PSO to prematurely converge to a local optimum, and it is simple and easy to implement. Moreover, it should be noted that the proposed inertia weight computation strategy can be transferred to other domains and optimization problems where its performance can be evaluated.

Finally, it is necessary to mention that more tests should be carried out to find the characteristics that allow us to determine the type of strategy for the calculation of the inertia weight that can adequately balance the search capabilities of the algorithm and yield better results for a particular scenario since those characteristics based on the diversity of the swarm did not turn out to be determinant.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S.-S. and O.C.-N.; formal analysis A.S.R.-C. and A.S.-S.; investigation A.S.R.-C.; methodology A.S.-S. and O.C.-N.; project administration A.S.-S. and C.S.-S.; resources A.S.-S., C.S.-S. and O.C.-N.; supervision A.S.-S. and O.C.-N.; validation A.S.-S. and A.S.R.-C.; visualization A.S.R.-C. and C.S.-S.; writing—original draft A.S.R.-C. and C.S.-S.; writing—review and editing A.S.-S. and O.C.-N. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sebbane, Y.B. Smart Autonomous Aircraft; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Faigl, J.; Váňa, P. Surveillance planning with Bezier curves. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2018, 3, 750–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar Gupta, S.; Dutta, P.; Rastogi, N.; Chaturvedi, S. A control algorithm for co-operatively aerial survey by using multiple UAVs. In Proceedings of the Recent Developments in Control, Automation & Power Engineering (RDCAPE), Noida, India, 26–27 October 2017; pp. 280–285. [Google Scholar]

- Mesquita, R.; Gaspar, P.D. A Path Planning Optimization Algorithm Based on Particle Swarm Optimization for UAVs for Bird Monitoring and Repelling-Simulation Results. In Proceedings of the 2020 International Conference on Decision Aid Sciences and Application, DASA 2020, Sakheer, Bahrain, 8–9 November 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Muliawan, W.; Ma’sum, M.A.; Alfiany, N.; Jatmiko, W. UAV Path planning for autonomous spraying task at salak plantation based on the severity of the plant disease. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Cybernetics and Computational Intelligence, Banda Aceh, Indonesia, 22–24 August 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-García, J.; Reina, D.G.; Toral, S.L. A distributed PSO-based exploration algorithm for a UAV network assisting a disaster scenario. Future Gener. Comput. Syst. 2019, 90, 129–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Fuchun, S.; Xiao, L.; Yixu, S. Overview of research on 3D path planning methods for rotor UAV. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Electronics, Circuits and Information Engineering, Zhengzhou, China, 22–24 January 2021; pp. 368–371. [Google Scholar]

- Yildrim, M.Y.; Akay, R. A comparative study of optimization algorithms for global path planning of mobile robots. Sak. Univ. J. Sci. 2021, 25, 417–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Qi, J.; Xiao, J.; Yong, X. A literature review of UAV 3D path planning. In Proceedings of the 11th World Congress on Intelligent Control and Automation, Shenyang, China, 29 June–4 July 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y.; Eberhart, R. Empirical Study of Particle Swarm Optimization. In Proceedings of the 1999 Congress on Evolutionary Computation-CEC99 (Cat. No. 99TH8406), Washington, DC, USA, 6–9 July 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y.; Eberhart, R. A modified particle swarm optimizer. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Evolutionary Computation Proceedings, Anchorage, AK, USA, 4–9 May 1998; pp. 69–73. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, M.; Akhter, Y. A Time-Varying Adaptive Inertia Weight based Modified PSO Algorithm for UAV Path Planning. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Robotics, Electrical and Signal Processing Techniques, Dhaka, Bangladesh, 5–7 January 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, H.; Li, P. Bio-Inspired Computation in Unmanned Aerial Vehicles; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal, S.; Kumar, N. Path planning techniques for unmanned aerial vehicles: A review, solutions and challenges. Comput. Commun. 2020, 149, 270–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zhao, H.; Wang, L. Three dimensional path planning of UAV based on adaptive particle swarm optimization algorithm. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1846, 012007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eberhart, R.; Kennedy, J. New optimizer using particle swarm theory. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Micro Machine and Human Science, Nagoya, Japan, 4–6 October 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.; Bai, W.; Xie, Y.; Sun, X.; Deng, C.; Cui, H. A hybrid algorithm of particle swarm optimization, metropolis criterion and RTS smoother for path planning of UAVs. Appl. Soft Comput. J. 2018, 73, 735–747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Yang, W.; Wang, Z.; Chen, J.; Xu, Y. Underwater Electric Dipole Source Localization Based on Hybrid Particle Swarm Optimization-Gravitational Search Algorithm. In Proceedings of the 2024 OES China Ocean Acoustics (COA), Harbin, China, 29–31 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Nayeem, G.M.; Fan, M.; Daiyan, G.M.; Fahad, K.S. UAV Path planning with an Adaptive Hybrid PSO. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Information and Communication Technology for Sustainable Development, ICICT4SD 2023-Proceedings, Dhaka, Bangladesh, 21–23 September 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Z.; Si, Z.; Li, X.; Wang, D.; Song, H. A Novel Hybrid Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm for Path Planning of UAVs. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 22547–22558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, J.; Chen, G.; Hai, Y. A particle swarm optimizer with multi-stage linearly-decreasing inertia weight. In Proceedings of the International Joint Conference on Computational Sciences and Optimization, Sanya, China, 24–26 April 2009; pp. 505–508. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.; Gao, W.; Liu, N.; Song, C. Low discrepancy sequence initialized with high-order non-linear time-varying inertia weight. Appl. Soft Comput. 2015, 29, 386–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Gao, Y. Particle swarm optimization algorithm with exponent decreasing inertia weight and stocastic mutation. In Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Information and Computing Science, Manchester, UK, 21–22 May 2009; pp. 66–69. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, M.; Nam, H. Path Planning Optimization of Smart Vehicle with Fast Converging Distance-Dependent PSO Algorithm. IEEE Open J. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 5, 726–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, W.; Zhu, J.; Cheng, W.; Bao, J. PSO Algorithm with Decreasing Inertia Weights Based on Sigmoid Function. In Proceedings of the 2024 2nd International Conference on Algorithm, Image Processing and Machine Vision, AIPMV 2024, Zhenjiang, China, 12–14 July 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.-X.; Gong, H.-L.; Ding, X.-Q. Investigation and Comparison of Inertia Weight Control Schemes in Particle Swarm Optimization. In Proceedings of the 2023 15th International Conference on Advanced Computational Intelligence, ICACI 2023, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 6–9 May 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, S.; Shi, Y. Diversity Control in Particle Swarm Optimization. In Proceedings of the 2011 IEEE Symposium on Swarm Intelligence, Paris, France, 11–15 April 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, P.; Zuo, J.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, J. Adaptive Particle Swarm Optimization and Its Application Model. In Proceedings of the 2024 5th International Conference on Computer Engineering and Application, ICCEA 2024, Hangzhou, China, 12–14 April 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Carrasco, G.; Cervantes, P.; Cortés, R.; Delgado, H.; Molinero, R. Patrones de viento en la región del volcán Popocatépetl y Ciudad de México. In Volcán Popocatépetl Estudios Realizados Durante la Crisis 1994–1995; Secretaría de Gobernación: Mexico City, Mexico, 1995; pp. 294–324. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).